CO2 Emission from Soils Under the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Addition and Polymer Superabsorbent Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Heterotrophic soil respiration—associated with the decomposition of organic matter by soil microorganisms. Microorganisms may decompose soil organic matter (SOM) independently of plant root function [12], where the quantity and quality of SOM from above-ground and below-ground litter may also control the decomposition [13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Soil Sampling and Preparation

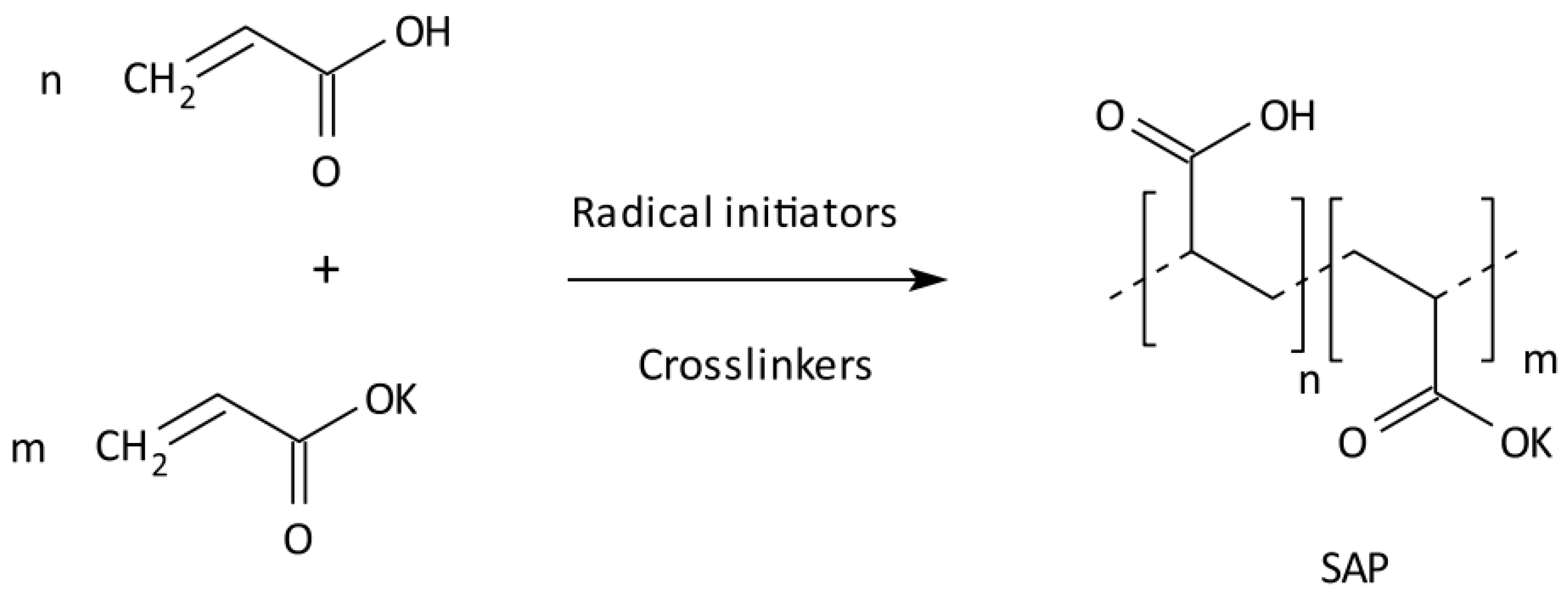

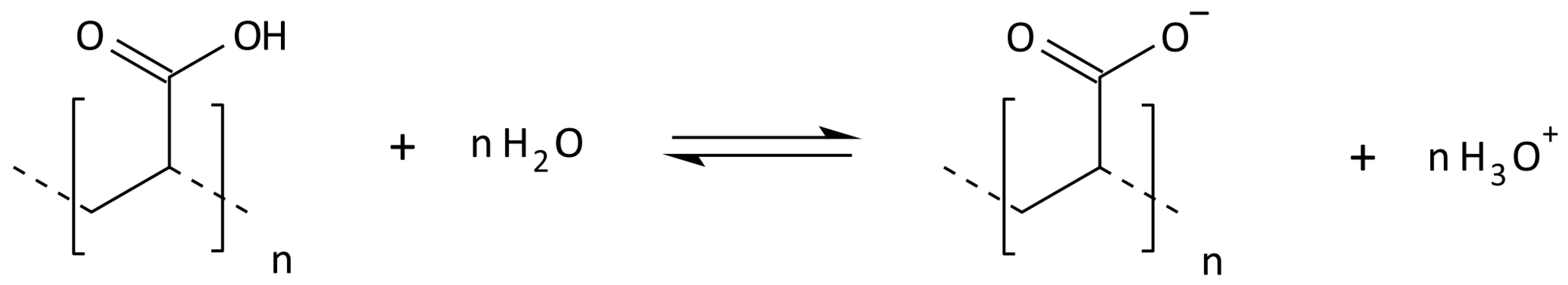

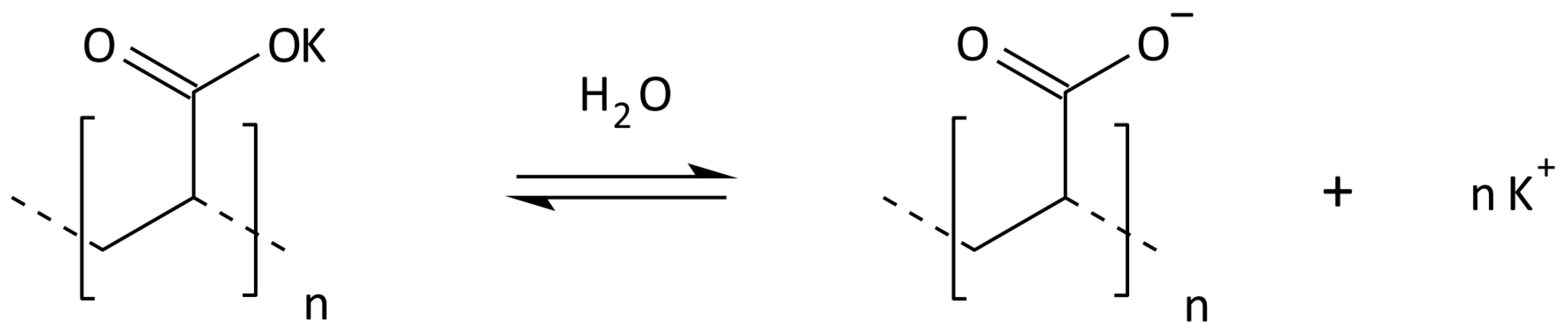

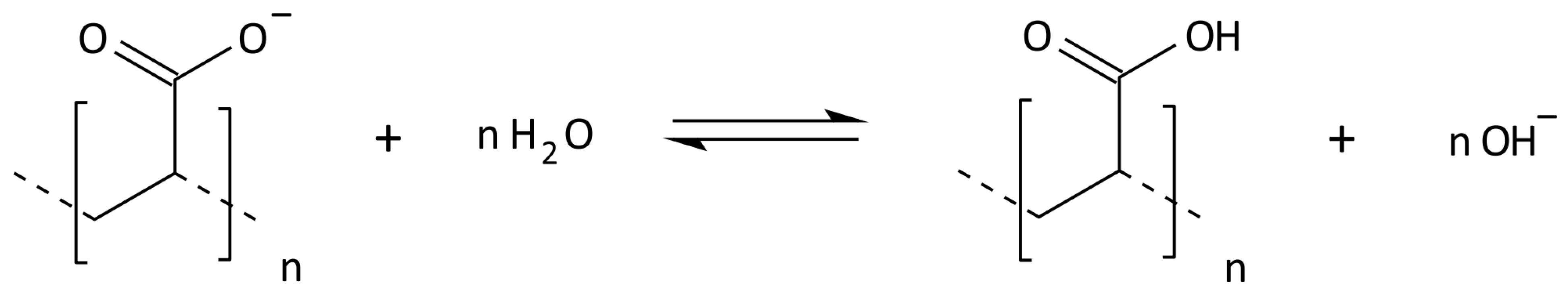

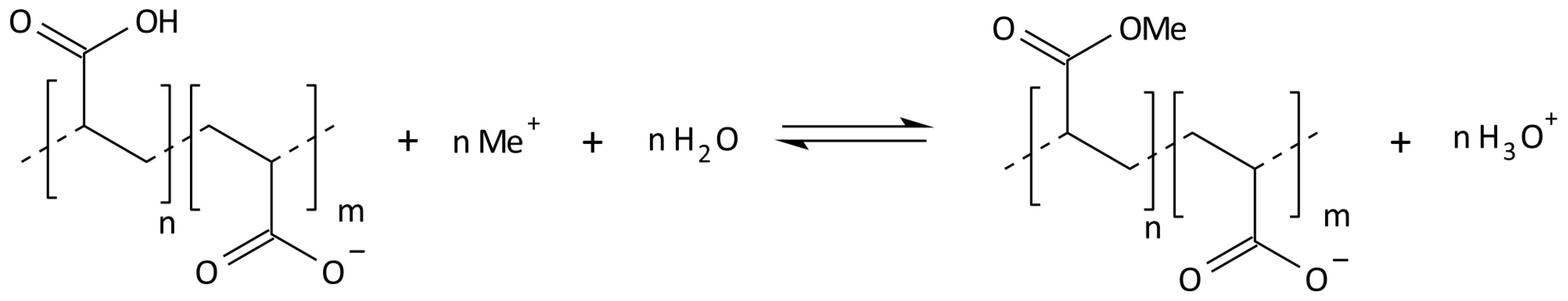

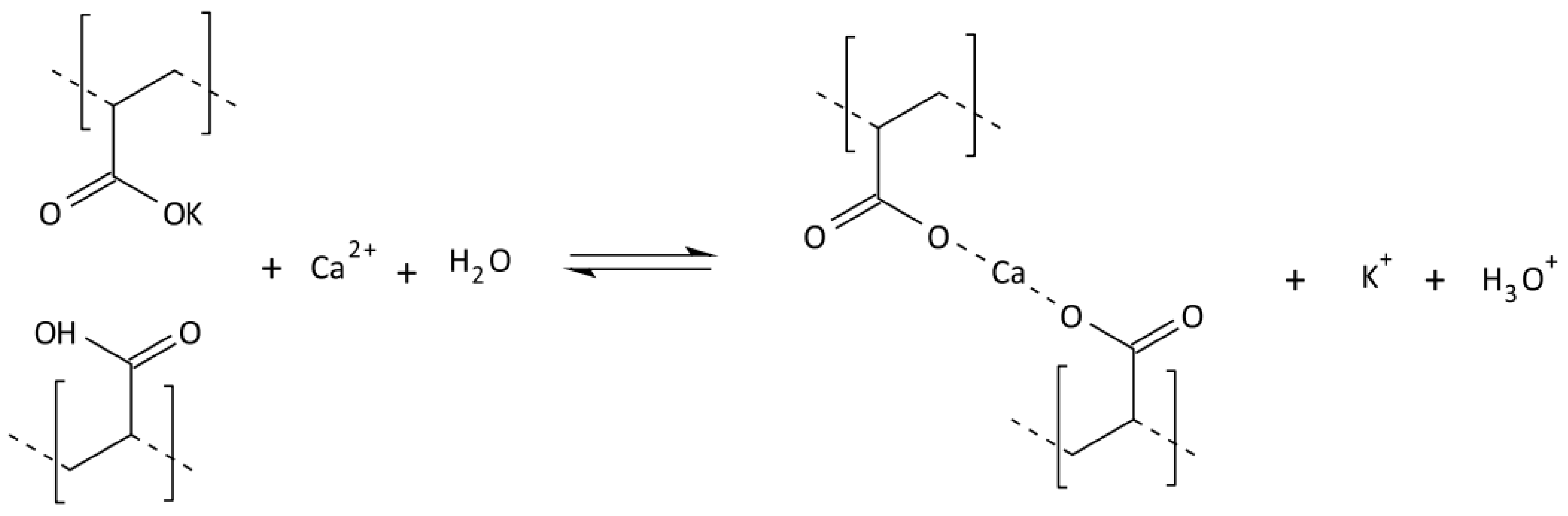

2.3. Synthesis of Cross-Linked Acrylic Polyelectrolytes

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Measurement of RESP

2.6. Measurement of Chemical and Physical Properties

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical, Chemical, and Microbial Properties of Soils Before Starting the Research

3.2. Soil Respiration After the Addition of Calcium Carbonate and PPA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAPs | Superabsorbent polymers |

| PAA | Acrylic superabsorbent polymers |

References

- Naorem, A.; Jayaraman, S.; Dalal, R.C.; Patra, A.; Rao, C.S.; Lal, R. Soil Inorganic Carbon as a Potential Sink in Carbon Storage in Dryland Soils—A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Richter, D.D.; Trumbore, S.E.; Jackson, R.B. Agricultural Acceleration of Soil Carbonate Weathering. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 5988–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, K.W.T. Soil Acidification and the Importance of Liming Agricultural Soils with Particular Reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag. 2016, 32, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, C.; Bréfort, H.; Frederico Fonseca, R.; Guyerdet, G.; Bizouard, F.; Arkoun, M.; Hénault, C. Surprising Minimisation of CO2 Emissions from a Sandy Loam Soil over a Rye Growing Period Achieved by Liming (CaCO3). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 175973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekenler, M.; Tabatabai, M.A. Effects of Liming and Tillage Systems on Microbial Biomass and Glycosidases in Soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2003, 39, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmitt, S.J.; Wright, D.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Jones, D.L. pH Regulation of Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics in Two Agricultural Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.-X.; Zhang, J.-B.; Cai, Z.-C.; Elsgaard, L.; Cheng, Y.; Jan van Groenigen, K.; Abalos, D. Liming Modifies Greenhouse Gas Fluxes from Soils: A Meta-Analysis of Biological Drivers. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, K.; Jakubiak, M. Impact of land use on soils microbial activity. J. Water Land Dev. 2017, 35, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Andrews, J.A. Soil Respiration and the Global Carbon Cycle. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, P.J.; Edwards, N.T.; Garten, C.T.; Andrews, J.A. Separating Root and Soil Microbial Contributions to Soil Respiration: A Review of Methods and Observations. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Meng, C.; Qu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Niu, J.; Wang, L.; Song, N.; Yin, Z. Dual Effects of Caragana korshinskii Introduction on Herbaceous Vegetation in Chinese Desert Areas: Short-Term Degradation and Long-Term Recovery. Plant Soil 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlian, O.; Wirth, C.; Eisenhauer, N. Leaf and Root C-to-N Ratios Are Poor Predictors of Soil Microbial Biomass C and Respiration across 32 Tree Species. Pedobiologia 2017, 65, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Long, J.R.; Jackson, B.G.; Wilkinson, A.; Pritchard, W.J.; Oakley, S.; Mason, K.E.; Stephan, J.G.; Ostle, N.J.; Johnson, D.; Baggs, E.M. Relationships between Plant Traits, Soil Properties and Carbon Fluxes Differ between Monocultures and Mixed Communities in Temperate Grassland. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 1704–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Meng, F.; Zhu, B. Influencing Factors and Partitioning Methods of Carbonate Contribution to CO2 Emissions from Calcareous Soils. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, G.; Shenker, M.; Heller, H.; Bloom, P.R.; Fine, P.; Bar-Tal, A. Can Soil Carbonate Dissolution Lead to Overestimation of Soil Respiration? Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramnarine, R.; Wagner-Riddle, C.; Dunfield, K.E.; Voroney, R.P. Contributions of Carbonates to Soil CO2 Emissions. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 2012, 92, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Singh, B.; Dalal, R.C.; Dijkstra, F.A. Carbon Dynamics from Carbonate Dissolution in Australian Agricultural Soils. Soil Res. 2015, 53, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhou, J. Effects of Moisture and Carbonate Additions on CO2 Emission from Calcareous Soil during Closed-Jar Incubation. J. Arid Land 2014, 6, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, S.; Chevallier, T.; Aissa, N.B.; Hammouda, M.B.; Gallali, T.; Chotte, J.L.; Bernoux, M. Short-Term Temperature Dependence of Heterotrophic Soil Respiration after One-Month of Pre-Incubation at Different Temperatures. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 43, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, K.; Sroka, P. Superabsorbent Hydrogels in the Agriculture and Reclamation of Degraded Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, F.L. Superabsorbent Polymers. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-471-44026-0. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Malik, A.; Punia, H.; Sewhag, M.; Berkesia, N.; Nagora, M.; Kalia, S.; Malik, K.; Kumar, D.; et al. Superabsorbent Polymers as a Soil Amendment for Increasing Agriculture Production with Reducing Water Losses under Water Stress Condition. Polymers 2023, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demitri, C.; Scalera, F.; Madaghiele, M.; Sannino, A.; Maffezzoli, A. Potential of Cellulose-Based Superabsorbent Hydrogels as Water Reservoir in Agriculture. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2013, 2013, e435073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, A.; De Belie, N.; Dubruel, P.; Van Vlierberghe, S. Superabsorbent Polymers: A Review on the Characteristics and Applications of Synthetic, Polysaccharide-Based, Semi-Synthetic and ‘Smart’ Derivatives. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 117, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wen, G. Development History and Synthesis of Super-Absorbent Polymers: A Review. J Polym Res 2020, 27, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.P.; Van Cleave, A.; Held, D.W.; Howe, J.A.; Auad, M.L. Preparation of Slow Release Encapsulated Insecticide and Fertilizer Based on Superabsorbent Polysaccharide Microbeads. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Sekharan, S.; Manna, U. Superabsorbent Hydrogel (SAH) as a Soil Amendment for Drought Management: A Review. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 204, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsakhoo, A.; Jajouzadeh, M.; Rezaee Motlagh, A. Effect of Hydroseeding on Grass Yield and Water Use Efficiency on Forest Road Artificial Soil Slopes. J. For. Sci. 2018, 64, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lu, J.; Xiao, C. Preparation and Properties of Novel Hydrogels from Oxidized Konjac Glucomannan Cross-Linked Chitosan Forin Vitro Drug Delivery. Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyliszczak, B.; Polaczek, J.; Pielichowski, J.; Pielichowski, K. Preparation and Properties of Biodegradable Slow-Release PAA Superabsorbent Matrixes for Phosphorus Fertilizers. Macromol. Symp. 2009, 279, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.E.; Domsch, K.H. A Physiological Method for the Quantitative Measurement of Microbial Biomass in Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1978, 10, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichting, E.; Blume, H.P. Bodenkundliches Praktikum: Verlag Paul Parey; Verlag Paul Parey: Hamburg, Germany, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, C.S.; Ribeiro, B.T.; Costa, E.T.D.S.; Curi, N.; Wendling, B. Effects of Phosphate, Carbonate, and Silicate Anions on CO2 Emission in a Typical Oxisol from Cerrado Region. Biosci. J. 2019, 35, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Singh, B.; Dijkstra, F.A.; Dalal, R.C.; Geelan-Small, P. Temperature Sensitivity and Carbon Release in an Acidic Soil Amended with Lime and Mulch. Geoderma 2014, 214–215, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Wu, L.; Peng, Q.-A.; van Zwieten, L.; Chhajro, M.A.; Wu, Y.; Lin, S.; Ahmed, M.M.; Khalid, M.S.; Abid, M.; et al. Influence of Ameliorating Soil Acidity with Dolomite on the Priming of Soil C Content and CO2 Emission. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 9241–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neina, D. The Role of Soil pH in Plant Nutrition and Soil Remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 2019, 5794869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.P.; Bezdicek, D.F.; Flury, M.; Albrecht, S.; Smith, J.L. Microbial Activity Affected by Lime in a Long-Term No-till Soil. Soil Tillage Res. 2006, 88, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdicek, D.F.; Beaver, T.; Granatstein, D. Subsoil Ridge Tillage and Lime Effects on Soil Microbial Activity, Soil pH, Erosion, and Wheat and Pea Yield in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Soil Tillage Res. 2003, 74, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Mohseni, N.; Moghtader, M.; Bahram, M.; Mohseni, N.; Moghtader, M. An Introduction to Hydrogels and Some Recent Applications. In Emerging Concepts in Analysis and Applications of Hydrogels; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-953-51-2510-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Ye, H.; Du, D.; Chi, R.; Han, Q. Highly Efficient and Sustainable Polyacrylic Acid-Polyacrylamide Double-Network Hydrogels Prepared by Cross-Linking of Waste Residues for Heavy Metals Ions Removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtiati, K.; Moghaddam, S.Z.; Daugaard, A.E.; Thormann, E. How Dissociation of Carboxylic Acid Groups in a Weak Polyelectrolyte Brush Depend on Their Distance from the Substrate. Langmuir 2020, 36, 2339–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguecir, A.; Ulrich, S.; Labille, J.; Fatin-Rouge, N.; Stoll, S.; Buffle, J. Size and pH Effect on Electrical and Conformational Behavior of Poly(Acrylic Acid): Simulation and Experiment. Eur. Polym. J. 2006, 42, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriwet, B.; Kissel, T. Interactions between Bioadhesive Poly(Acrylic Acid) and Calciumions. Int. J. Pharm. 1996, 127, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.X.D.; Wong, H.S.; Buenfeld, N.R. Effect of Alkalinity and Calcium Concentration of Pore Solution on the Swelling and Ionic Exchange of Superabsorbent Polymers in Cement Paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 88, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifah, O.; Ahmed, O.H.; Majid, N.M.A. Soil pH Buffering Capacity and Nitrogen Availability Following Compost Application in a Tropical Acid Soil. Compost. Sci. Util. 2018, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.N.; Su, N. Soil pH Buffering Capacity: A Descriptive Function and Its Application to Some Acidic Tropical Soils. Aust. J. Soil Res. 2010, 48, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Localization | Sand 2–0.05 mm [%] | Silt 0.05–0.002 mm [%] | Clay <0.002 mm [%] | WHC [%] | pH in H2O | C Total [%] | Carbonates [%] | RESP [µM CO2/g/24 h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Szczakowa (Sz) | 99 | 1 | 0 | 10.3 ± 1.1 | 7.0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Budzów (B) | 46 | 39 | 15 | 65.5 ± 1.1 | 5.9 | 2.68 ± 0.22 | 0 | 2.22 ± 0.02 |

| Brody (Br) | 12 | 70 | 18 | 59.1 ± 4.1 | 5.9 | 2.07 ± 0.12 | 0 | 0.66 ± 0.02 |

| Kraków (K) | 12 | 77 | 11 | 41.4 ± 1.2 | 6.4 | 2.43 ± 0.12 | 0 | 0.69 ± 0.01 |

| RESP 1 [µMCO2/g/24 h] | RESP 2 [µMCO2/g/24 h] | RESP 3 [µMCO2/g/24 h] | RESP 4 [µMCO2/g/24 h] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Sz1 | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.02 ± 0.02 a | 0.03 ± 0.02 a | 0.01 ± 0.01 a |

| Sz2 | 0.86 ± 0.09 c | 0.19 ± 0.02 a | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 0.10 ± 0.03 a |

| Br1 | 3.04 ± 0.09 b | 2.80 ± 0.13 b | 2.80 ± 0.17 b | 4.42 ± 0.17 b |

| Br2 | 2.99 ± 0.17 b | 2.65 ± 0.05 b | 2.83 ± 0.09 b | 3.49 ± 0.05 b |

| K1 | 1.55 ± 0.04 c | 1.68 ± 0.04 c | 1.90 ± 0.017 c | 3.15 ± 0.27 cd |

| K2 | 1.55 ± 0.07 c | 1.73 ± 0.02 c | 2.04 ± 0.08 c | 2.69 ± 0.64 bc |

| B1 | 4.60 ± 0.18 d | 3.75± 0.35 d | 3.48 ± 0.11 d | 5.46 ± 0.20 de |

| B2 | 4.70 ± 0.06 d | 3.81 ± 0.07 d | 3.49 ± 0.16 d | 6.60 ± 1.32 e |

| Localization | pH in H2O |

|---|---|

| Sz1 | 8.3 |

| Sz2 | 8.9 |

| B1 | 7.2 |

| B2 | 6.9 |

| Br1 | 7.2 |

| Br2 | 7.1 |

| K1 | 7.2 |

| K2 | 7.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sroka, K.; Sroka, P.; Santos, L.; Baptista, C. CO2 Emission from Soils Under the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Addition and Polymer Superabsorbent Application. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312708

Sroka K, Sroka P, Santos L, Baptista C. CO2 Emission from Soils Under the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Addition and Polymer Superabsorbent Application. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312708

Chicago/Turabian StyleSroka, Katarzyna, Paweł Sroka, Luis Santos, and Cecilia Baptista. 2025. "CO2 Emission from Soils Under the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Addition and Polymer Superabsorbent Application" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312708

APA StyleSroka, K., Sroka, P., Santos, L., & Baptista, C. (2025). CO2 Emission from Soils Under the Influence of Calcium Carbonate Addition and Polymer Superabsorbent Application. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312708