1. Introduction

Global network traffic is rapidly increasing due to factors such as the growing number of network users and the rising popularity of Internet streaming services, including 4K/8K video, game streaming, and virtual reality. Furthermore, the advancement of 5G and fixed 5G (F5G) communication technologies improves the service capabilities of access networks [

1], further driving the proliferation of these new applications. The continuous emergence of new services and applications based on the Internet Protocol (IP), which requires substantial bandwidth and necessitates efficient network management. These services often rely on communication with specialized servers located in specific nodes, such as data centers. Consequently, the network must maintain the ability to handle traffic seamlessly, even under congestion conditions and fluctuating transmission rates.

Multi-layer networks have become a popular infrastructure choice for network operators. This architecture features an optical substrate for physical communication, with an IP overlay on top [

2]. The optical layer is tasked with carrying IP traffic by establishing optical connections, or lightpaths, making it crucial for managing heavy traffic loads. Effective cooperation between the IP and optical layers is essential for balanced resource utilization across both layers [

3,

4]. Centralized architectures, such as Software-Defined Networking (SDN), are among the most promising solutions to meet these requirements [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The concept of SDN revolves around the separation of control and data planes [

9]. Within this architecture, the central controller in the control plane determines the routing of packets in the data plane. Advances in software control have unlocked new opportunities for the effective utilization of multi-layer resources. One approach is the diversification of optical resources to improve network efficiency and manage unexpected traffic fluctuations, as discussed in [

10,

11,

12]. This involves reserving a portion of optical resources for emergency traffic surges, allowing the SDN controller to establish additional lightpaths when necessary [

13]. This strategy has been extensively evaluated in IP-over-Wavelength Division Multiplexing (IP-over-WDM) networks. However, WDM is expected to be superseded by emerging Elastic Optical Network (EON) technology, which utilizes the optical spectrum more efficiently, as detailed in [

14,

15].

To address the significant growth in traffic, Elastic Optical Networks (EONs) have been proposed as a potential solution [

16]. The initial concept of an EON, known as the Spectrum-Sliced Elastic Optical Path Network (SLICE), was introduced in [

17] and has been elaborated in various studies, including [

18,

19,

20]. In the SLICE architecture, the optical spectrum along an end-to-end path is divided into narrow frequency segments to accommodate specific traffic demands. EONs enhance spectral resource efficiency through multi-granular spectrum allocation and adaptive transmission rates. The allocation of lightpath requests in EONs must adhere to spectrum contiguity and continuity constraints to fulfill bandwidth requirements, a challenge known as the Routing and Spectrum Allocation (RSA) or Routing, Modulation, and Spectrum Allocation (RMSA) problem [

21]. Since the advent of EONs, substantial efforts have been made to integrate IP and EON into a multi-layer architecture [

22,

23], and to extend the SDN concept into an efficient IP-over-EON environment [

6,

24]. However, research on the diversification of optical resources within the IP-over-EON architecture remains limited. Therefore, it is imperative to propose and investigate approaches that address this gap in the IP-over-EON network.

This paper addresses the issue of congestion in dynamic resource allocation within the IP-over-EON architecture. It postulates that the EON layer can furnish two distinct types of resource in a multi-layer network. The first type is accessible to the upper (IP) layer, allowing the establishment of lightpaths that function as virtual links. Here, the terms IP and virtual are used synonymously to denote the IP layer. The second type of resource is hidden from the IP layer and is designated for Automatic Hidden Elastic Optical Bypasses (AHEOBs), which are dynamically activated in response to congestion. Consequently, AHEOB refers to a lightpath that uses hidden resources. The proposed approach aligns seamlessly with the SDN framework. Within this framework, the SDN controller determines the appropriate layer to manage the request and allocates resources accordingly. Since the optical layer is tasked with the carriage of traffic by establishing lightpaths, the resource allocation problem in the EON is thoroughly examined. Specifically, the study explores two path selection policies. The effectiveness of AHEOBs is evaluated through numerical simulations conducted on two network topologies (NSF15 and UBN24) under dynamic traffic conditions. These topologies were selected due to their long optical bypass paths, which in turn lead to less efficient modulation formats for bypasses compared to virtual IP-layer links. This distinctive feature of these networks makes it more challenging to exploit bypasses; however, our study demonstrates that bypass mechanisms can still be beneficial even in such extensive topologies. Therefore, the choice of these networks enhances the generality of our findings by confirming the practical applicability of bypass-based approaches in scenarios where optical paths are long and modulation efficiency is reduced. All experiments were performed using the OMNeT++ discrete-event simulation platform.

Achievements and Contributions

The achievements and contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

A new solution is proposed to deal with traffic fluctuation in the multi-layer network. The AHEOB approach operates in both the virtual and EON layers.

To evaluate AHEOBs, a set of modules implementing IP-over-EON in OMNeT++ simulation tools were designed and deployed as an integral part of the research presented in this paper.

The analysis of the results has shown that all AHEOB approaches achieve a reduction in BBP and provide lower resource utilization, including both the number of hops in the IP layer and the overall spectrum occupation compared to the reference approach.

AHEOBs are shown to be suitable for networks that handle highly unpredictable traffic fluctuations.

The remainder of this paper is divided as follows.

Section 2 discusses related works and the differences between these works;

Section 3 presents the notation used in this paper;

Section 4 proposes the generalized AHEOB framework;

Section 5 introduces the RSA solution for setting AHEOBs;

Section 6 describes the simulation setup used for obtaining the results;

Section 7 presents the simulation results obtained for different types of network topologies. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

In this section, we present works related to the concept of the diversification of EON resources to offload traffic fluctuations.

The concept of diversification of EON resources in multi-layer networks was introduced in [

25]. The primary goal is to route traffic through IP paths while dynamically establishing new lightpaths (bypasses) in the optical layer to mitigate traffic congestion. This is achieved utilizing hidden resources and a novel bypass path selection policy to ensure effective load balancing. This study employs numerical simulations in two reference topologies to evaluate the performance of the proposed mechanisms under various dynamic scenarios. The findings reveal that bypass-based methods significantly reduce the bandwidth blocking probability (BBP) compared to non-bypass scenarios. In addition, the introduction of bypasses reduces resource utilization. However, more simulations are still needed to confirm these findings.

Paper [

26] explores the challenges of managing increasing global Internet traffic and proposes a novel solution for resource-efficient multi-layer optical networks. Using an SDN, the study integrates Flow-Aware Multi-Topology Adaptive Routing (FAMTAR) and Automatic Hidden Bypasses (AHBs) to improve network performance. The SDN controller centrally manages these mechanisms, enabling simultaneous, multi-path data transmissions in both IP and optical layers. This approach optimizes optical spectral efficiency and ensures better resource utilization. The architecture dynamically allocates optical slices between the IP and optical layers, creating IP links and dynamic bypasses to handle congestion. FAMTAR adjusts link costs based on network load, while AHB establishes temporary lightpaths to offload traffic during congestion. In contrast, in this paper, we utilize the Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) protocol in the IP layer.

Paper [

27] investigates the problem of managing high-priority traffic in IP-over-EONs through the implementation of priority-aware bypasses (PABs). The authors of [

27] highlight the importance of efficiently handling high-priority traffic and introduce a priority-aware bypass algorithm that takes advantage of the flexibility of the SDN. Using hidden optical resources in the EON layer, the proposed method aims to minimize the BBP for high-priority traffic. This is achieved by dynamically establishing bypass paths that can offload congested links in the IP layer. The results demonstrated that the PAB approach significantly reduces BBP for high-priority traffic compared to both non-bypass and priority-agnostic bypass mechanisms.

Finally, paper [

28] investigates the integration and performance of Automatic Hidden Lightpaths (AHLs) within multi-layer networks, specifically in the context of SDN-based IP-over-EONs. This analysis addresses the growing demand for efficient and scalable network resource utilization due to the increasing number of Internet users and the migration of services to the cloud. Through simulations, the number of candidate paths that utilize AHL was investigated. Taking into account AHLs, the proposed solution effectively manages traffic fluctuations, providing a scalable and efficient use of existing IP and optical network resources.

In this paper, we generalize our earlier studies by formalizing the visible vs. hidden spectrum, introducing an IP-layer congestion threshold, changing traffic-source selection, and expanding credibility analysis and quantitative evidence. We selected traffic-origin nodes using the minimum average shortest-path distance (Vsp), which tends to shorten optical routes and enable higher-order modulations on bypasses, keeping the same two traffic types and ranges. In contrast, ref. [

25] focused exclusively on traffic bursts generated by nodes with the highest nodal degree (Vdeg). The work in [

26] introduced the FAMTAR mechanism within the context of hidden resources, while ref. [

27] presented the PAB mechanism for the same resource category. Meanwhile, ref. [

28] concentrated on reducing blocking probability without increasing total network resources and analyzed how the number of candidate paths (k = 10/20/30) and source node selection affect performance in the Euro26 network, but only for the SPF method. The current paper represents a mature and systematic extension of these earlier efforts. It preserves the core comparison between Shortest Path First (SPF) and the most spectrally efficient with largest slice first (MSEwLSF) path selection method in IP-over-EON networks, while introducing explicit IP-layer congestion control, a topology-aware method for selecting traffic-origin nodes, and a more rigorous experimental validation. These enhancements improve both the explanatory value and practical relevance of the bypass concept.

Table 1 summarizes related works and highlights the new contributions and distinctions of this paper.

As can be seen, there are only a few papers related to bypasses in IP over EON, and more research is needed to investigate the diversification of EON resources in multi-layer networks for different network scenarios.

3. Notation

This section introduces the notation assumed in this paper; the same notation was used in [

28]. In general, a network topology can be modeled as a graph with possible additional constraints such as a number of slices or a link capacity. Specifically, the topology of the network is defined by

, where

is the set of nodes and

is the set of links, e.g., fiber links and virtual links. The request

d is defined by

, where

s is the source node of the request and

t is the destination node of the request.

represents the requested bandwidth (bit rate) between the end nodes

s and

t. It should be noted that

d in the virtual layer denotes the bandwidth requirement, while

d in the EON layer is the request to set the lightpath. Each lightpath (including AHEOB) represents a path

p and an optical spectrum with a width equal to the number of slices

. The width depends on the requested bandwidth and applied transmission model. The transmission model can be considered the set of possible modulation formats

, each characterized by the spectral efficiency

and the corresponding maximum transmission distance range

for the assumed width of the slice

.

4. Automatic Hidden Elastic Optical Bypasses

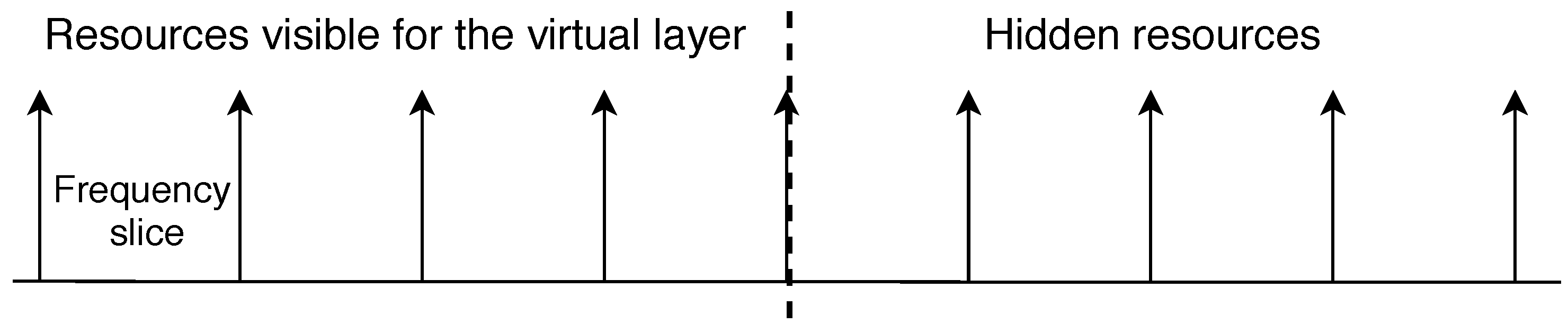

The concept of Automatic Hidden Elastic Optical Bypasses (AHEOBs) involves revealing only selected optical resources to the IP layer, while designating the remaining spectrum as hidden resources to be utilized during congestion. Since in the EON, the available optical spectrum is divided into narrow frequency slices of a given granularity (e.g., 6.25 GHz, 12.5 GHz, or 37.5 GHz) [

29], we consider optical resources as the number of slices visible for the IP layer, and the number of slices reserved for AHEOBs.

Figure 1 illustrates this diversification of resources. It is assumed that the amount of hidden resources may be at most equal to the resources visible to the IP layer. This section introduces an AHEOB strategy designed to optimize resource utilization and reduce rejected traffic.

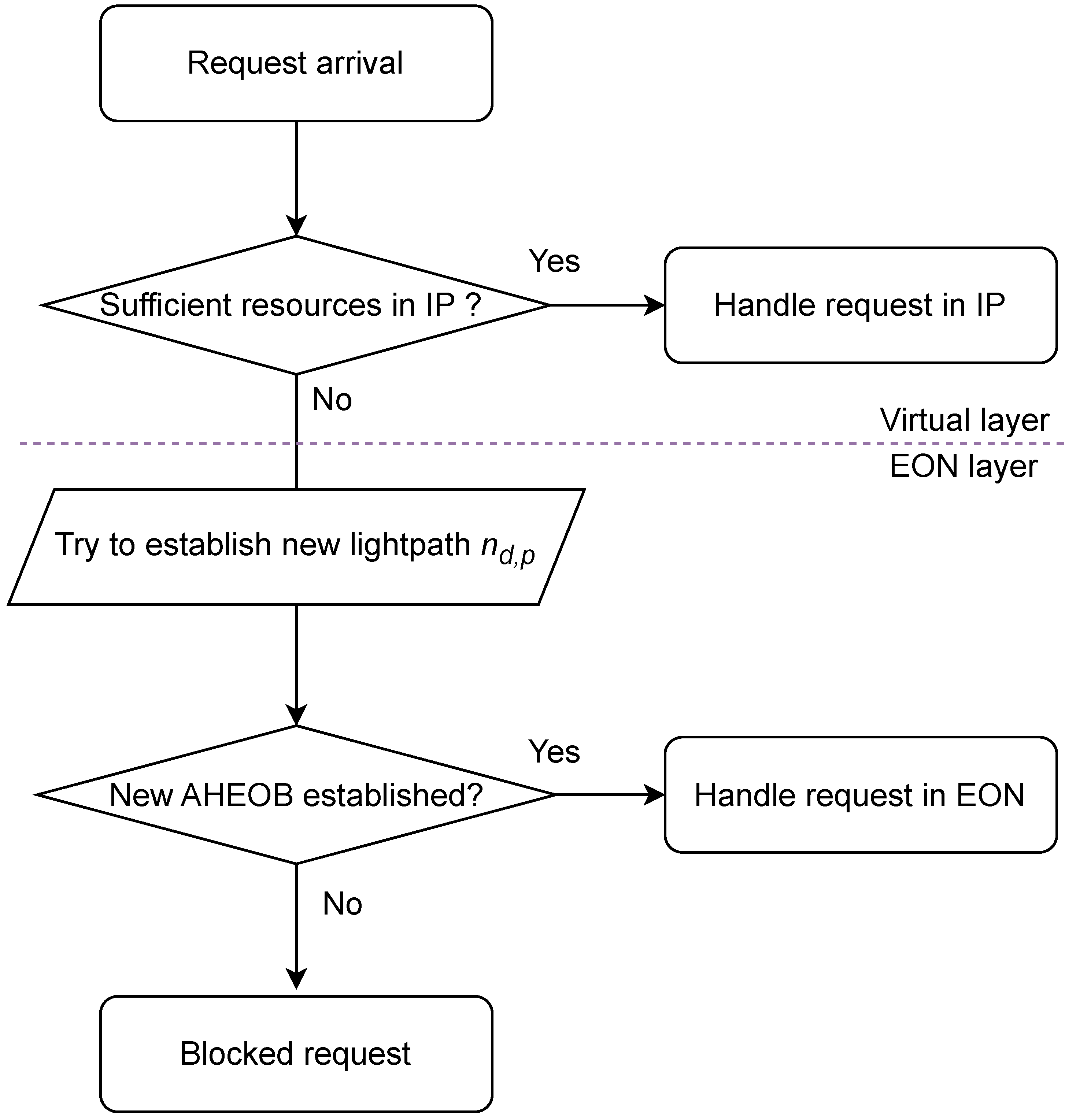

The proposed AHEOB framework is fully compatible with the SDN paradigm. The algorithm is triggered by the arrival of a new demand (request)

d. The controller, which has knowledge of both the network topology and the current state of the network, initially verifies the availability of sufficient resources. Algorithm 1 describes the pseudocode of AHEOB. Firstly, the controller assesses the resources in the virtual layer. To solve the routing problem on the IP layer and facilitate traffic flow between nodes

s and

t, the algorithm determines the shortest route (line 1). If adequate resources are available, the request is accommodated within this layer, and the algorithm terminates; true is returned (lines 2–4). However, if the requested bandwidth cannot be ensured in the IP layer, the SDN controller then attempts to utilize the EON layer. In the EON layer, it is anticipated that hidden resources can meet the new demand. In particular, the RSA or the RMSA method is applied in this layer. For traffic provisioning purposes, the requested bit rate

is translated into the number of frequency slices

. If it is feasible to configure an AHEOB, hidden resources are allocated, which finishes the process, and true is returned (lines 6–9). If the EON layer also does not accommodate the demand, the request is blocked, and false is returned (line 12).

Figure 2 shows the steps of the AHEOB algorithm [

28].

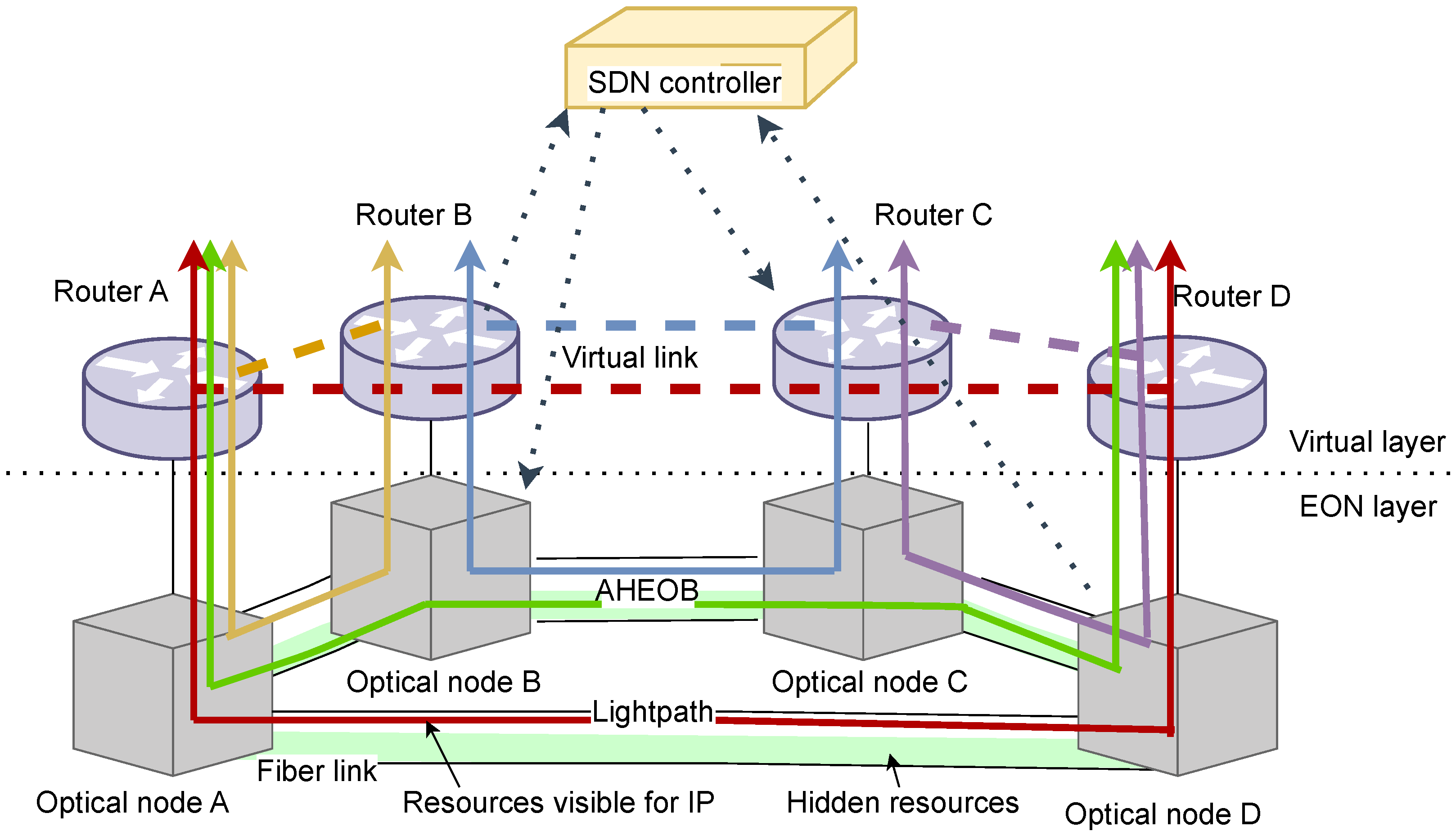

Figure 3 shows an example of the SDN-based multi-layer architecture [

24] with an AHEOB established [

25]. The capacity of each virtual link is constrained by the maximum capacity provided by a lightpath, which occupies a set of feasible slices for the IP layer. As can be seen in

Figure 3, virtual links are related to lightpaths visible in the IP layer, e.g., lightpaths A-B, A-D, D-C, and C-B handle virtual links between routers A-B, A-D, D-C, and C-B, respectively. In the case of congestion in the IP layer on a virtual link A-B, an A-D-C-B AHEOB is established to offload the new traffic (incoming request), but no new lightpath is reported in the virtual layer. When transmission handled by the AHEOB ends, the lightpath is torn down and optical resources are released. Thus, resources can be used to set up another AHEOB. AHEOBs are transparent to the virtual layer. Hence, the routing tables in the routers do not need to be updated when a new AHEOB is created.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode describing AHEOB. |

Required: New d between s and t- 1:

Determine the route in IP for d - 2:

if Resources along route are sufficient then - 3:

Handle request in IP - 4:

return true - 5:

else - 6:

Try to establish new lightpath - 7:

if New AHEOB is established then - 8:

Handle request in EON - 9:

return true - 10:

else - 11:

d is blocked - 12:

return false - 13:

end if - 14:

end if

|

Finally, it can be noted that in a common scenario (non-bypass), all optical resources are visible for IP and are utilized to establish virtual links. Each lightpath is then abstracted in the IP layer as a virtual link, and traffic is routed through this layer.

The pseudocode in Algorithm 2 describes the principle of non-bypass. The route in the IP layer for d is determined (line 1). If resources along the route are sufficient, the IP layer handles the request, and true is returned (lines 2 and 3). If the requested bandwidth of

d cannot be guaranteed in the IP layer, then

d is blocked, and false is returned (lines 6 and 7).

| Algorithm 2 Pseudocode describing non-bypass. |

Required: New d between s and t- 1:

Determine the route in IP for d - 2:

if Resources along route are sufficient then - 3:

Handle request in IP - 4:

return true - 5:

else - 6:

d is blocked - 7:

return false - 8:

end if

|

5. Lightpaths in the EON Layer

As mentioned before, the EON layer requires solving the RSA/RMSA [

30] problem to set up lightpaths between end nodes. Similarly, when AHEOBs need to be dynamically established to omit links congested in the IP layer, the RSA/RMSA problem should be solved. In this paper, we consider a two-step strategy [

31]. The first step searches for the appropriate route between

s and

t with a determined modulation format. The second step tries to allocate a required number of slices

[

32]. We briefly describe the RMSA algorithm and the path selection policy called Shortest Path First (SPF) in [

28]. In the following, we describe the MSEwLSF path selection policy and compare MSEwLSF and SPF, and finally, we present the First Fit (FF) spectrum allocation policy.

5.1. Most Spectrally Efficient Path with Largest Slices First

The actual state of the EON layer is assumed to be given. Routing is performed using fixed path sets, containing k shortest paths. When a new demand

d arrives that requests

, the set of k candidate paths

for

d is computed. Then, candidate paths

are sorted according to the most spectrally efficient path with the largest slices first (MSEwLSF) [

25]. The pseudocode in Algorithm 3 describes the principle of MSEwLSF. We define the

metric as the number of available slices on a path. First, the paths are formed into

m groups according to the most spectrally efficient modulation format

m determined for a particular path (line 1). Starting from the group with the highest

m, within a single group, the

metric is calculated for each path (line 4). The paths are then sorted in decreasing order according to the

inside a particular

m-group (line 6). Finally, sorted paths (from the highest

m group to the smallest one) (line 8) might be proceeded in the next step of RMSA, namely spectrum allocation.

| Algorithm 3 Pseudocode describing the MSEwLSF. |

Input: - 1:

- 2:

fordo - 3:

for do - 4:

- 5:

end for - 6:

- 7:

end for - 8:

|

As can be seen, MSEwLSF considers path utilization as well as the modulation format selected for the path. Thus, the MSEwLSF method considers spreading traffic over a network and selects short paths. To understand the difference between MSEwLSF and SPF path selection policies, Example 1 is presented.

Example 1. Consider five candidate paths, p1, p2, p3, p4, and p5, with the following parameters for the request. The path lengths are , and the highest modulation format used by p1, p2, and p3 is the same and four times higher than for p4 and p5. Paths p4 and p5 adopt the same modulation format. The calculated metrics are . The SPF method checks candidate paths in the following order: p1, p2, p3, p4, and p5. And the MSEwLSF method does so in the following order: p3, p1, p2, p5, and p4.

In summary, MSEwLSF analyzes the spectrum utilization of paths belonging to the same group of modulation formats. Path utilization takes into account dynamic changes in spectrum occupancy. Therefore, the slices allocated for a particular lightpath can be spread over the network. As a result, the network load is balanced across the entire network. Considering the group of paths of one modulation format ensures that the calculated is the same as for SPF. The goal of the MSEwLSF method is to minimize BBP in the network.

5.2. First Fit Spectrum Allocation Policy

This section provides a spectrum allocation method that assigns a set of slices along the determined path. The spectrum allocation policy answers the question of how to choose the set of slices across specific links. The simplest and often implemented spectrum allocation policy is a first fit (FF) policy described in [

33,

34,

35,

36]. This policy allocates a request to the first feasible, available set of frequency slices along a path.

6. Simulation Details

Numerous simulation experiments were conducted to empirically verify the efficacy of the proposed mechanisms. To determine the mean values of the parameters discussed in this paper, discrete event simulations were carried out in steady state. Two reference networks were selected for these simulations. Details about simulation tools and their credibility are provided in

Section 6.1 and

Section 6.2, respectively. The topologies used in the simulations are described in

Section 6.3, while the EON and IP layers are detailed in

Section 6.4. Lastly, the performance indicators measured during the simulations are presented in

Section 6.5.

6.1. Simulation Tools

The purpose of this paper is to provide insight into the performance of AHEOBs. The discrete-event simulation type was used in our work. Such simulation experiments manage events in time. The queue of events is maintained by the simulator, and the events are sorted by the simulated time they should occur. The events are executed one by one. Therefore, there is no need to run the simulation in real time. Simulations are a perfect tool with which to increase knowledge of the system studied.

The simulation cases and architectures were developed in OMNeT++ version 5.6.1 Academic Edition, under Academic Public License. OMNeT++ [

37] is an object-oriented modular discrete-event simulation framework [

38] and is open source software. All simulation runs were provided with the stable and fully implemented versions of the IP-over-EON architecture. The results obtained were adapted to the needs of Microsoft Excel, and the statistical estimation of the expected values and confidence intervals for the variables examined was performed using Microsoft Excel. The plots were drawn using the LaTeX pgfplots package.

6.2. Simulation Credibility

The technique for collecting simulation data/samples containing independent observations used in the research was the independent replication method [

39]. Therefore, simulations were run several times using differently seeded pseudorandom number generators. In each simulation run, traffic demands arrived in batches based on an exponentially distributed inter-arrival time and a mean value

. The holding time for each request was also modeled using an exponential distribution with a mean value

. To simulate varying traffic load conditions, calculated as

Erlangs, the mean value of

was changed step by step, and simultaneously the value of

was kept constant. To obtain valuable results from the experiments, all observations of simulation parameters were provided in steady state. The system was allowed to reach steady state after processing 5000 demands, and then the average value was calculated from a batch consisting of

generated demands. Each scenario was simulated 30 times and the 95% confidence intervals were determined under the assumption of a normal distribution, according to Pawlikowski’s methodology [

40].

For simulations, three independent random number generators were used. The first one was used to generate inter-arrival times between requests. The second was used to generate the holding time for requests. The last generator was used to generate the requested bandwidth, following a uniform distribution. OMNeT++ implements an algorithm called Mersenne Twister [

41] to generate uniform pseudorandom numbers. For a particular choice of parameters, the algorithm provides a cycle duration of

, and the 623-dimensional equidistribution property is ensured. The correctness of the generator implementation is ensured by built-in validation mechanisms.

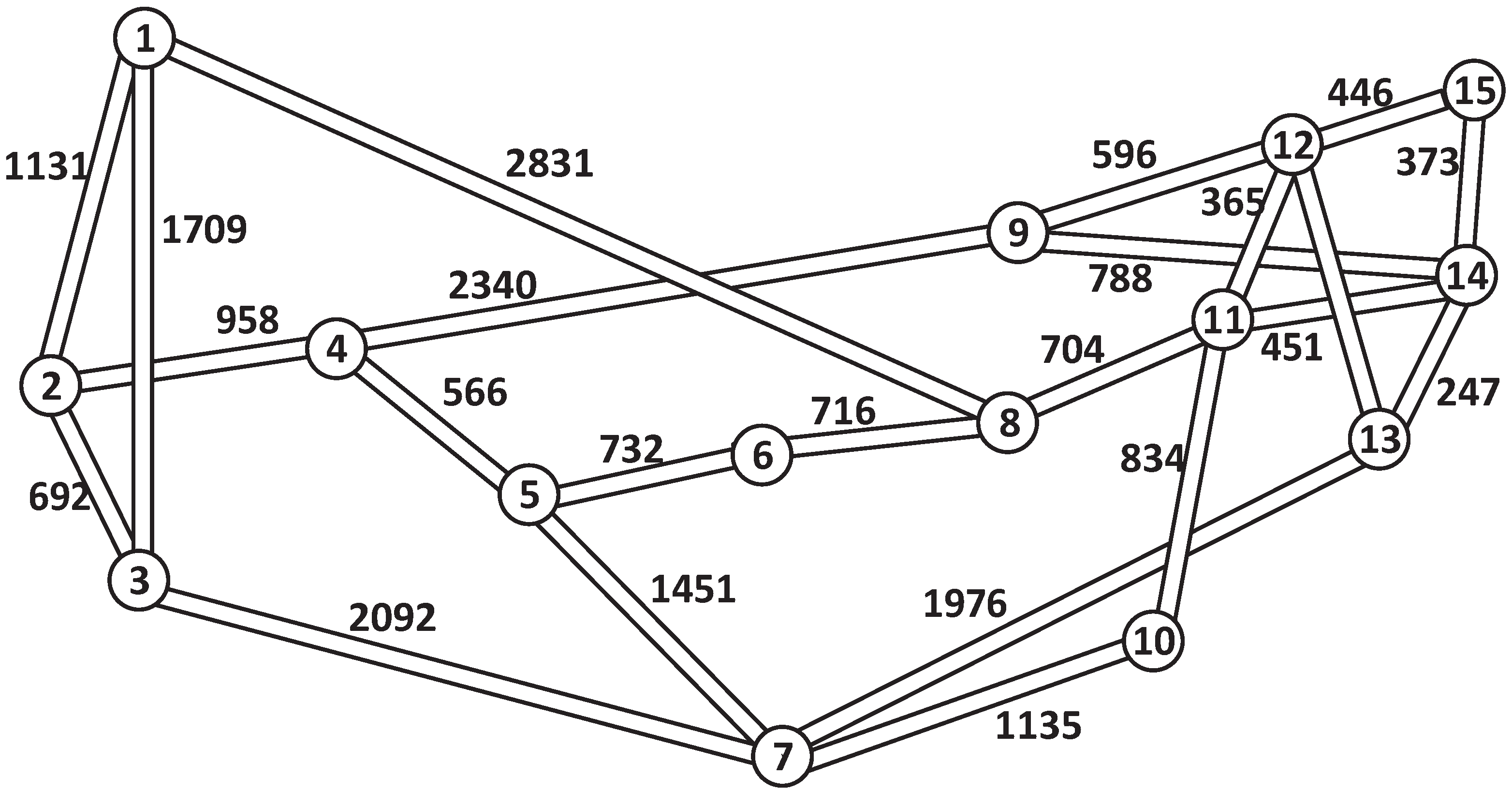

6.3. Topology

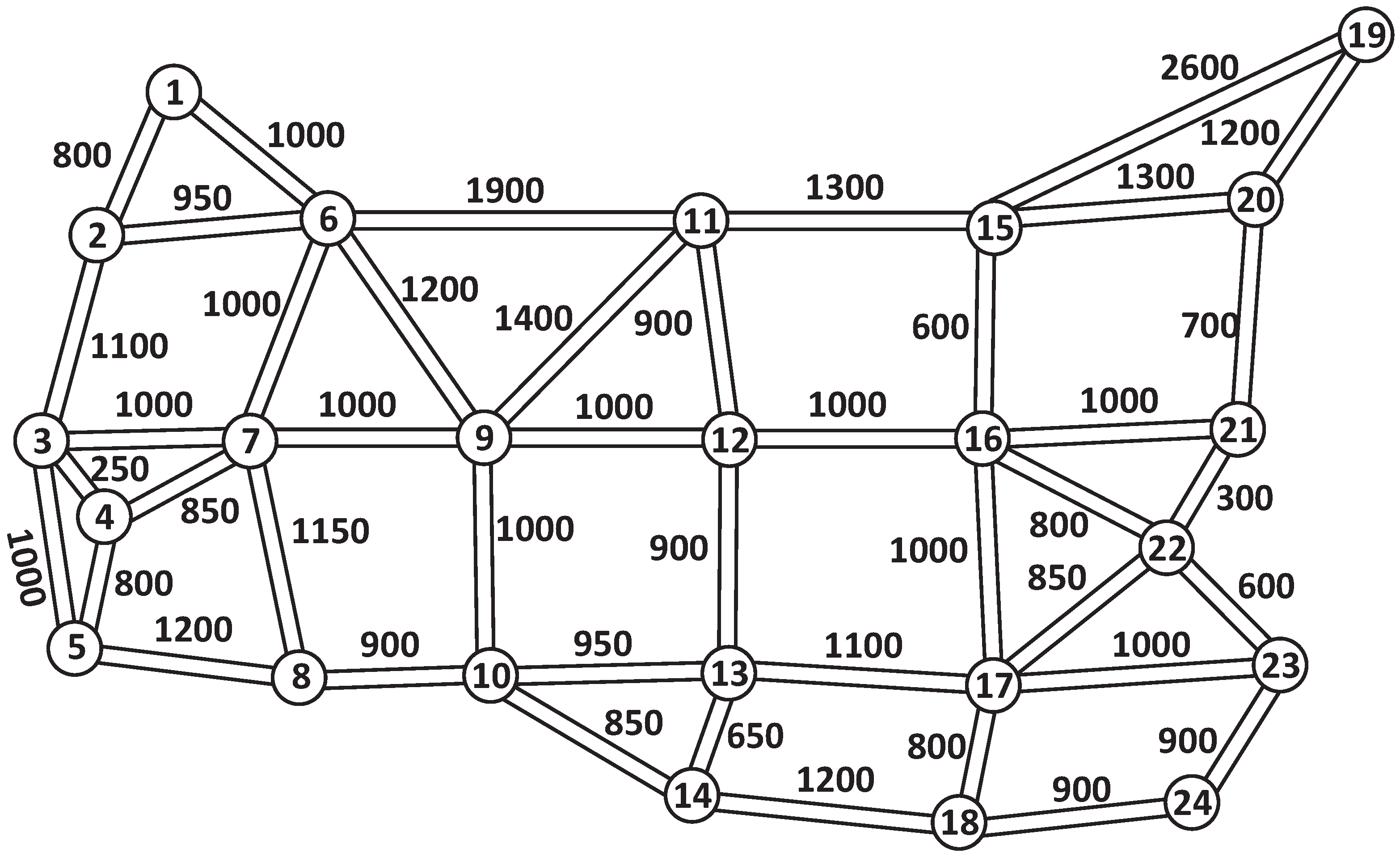

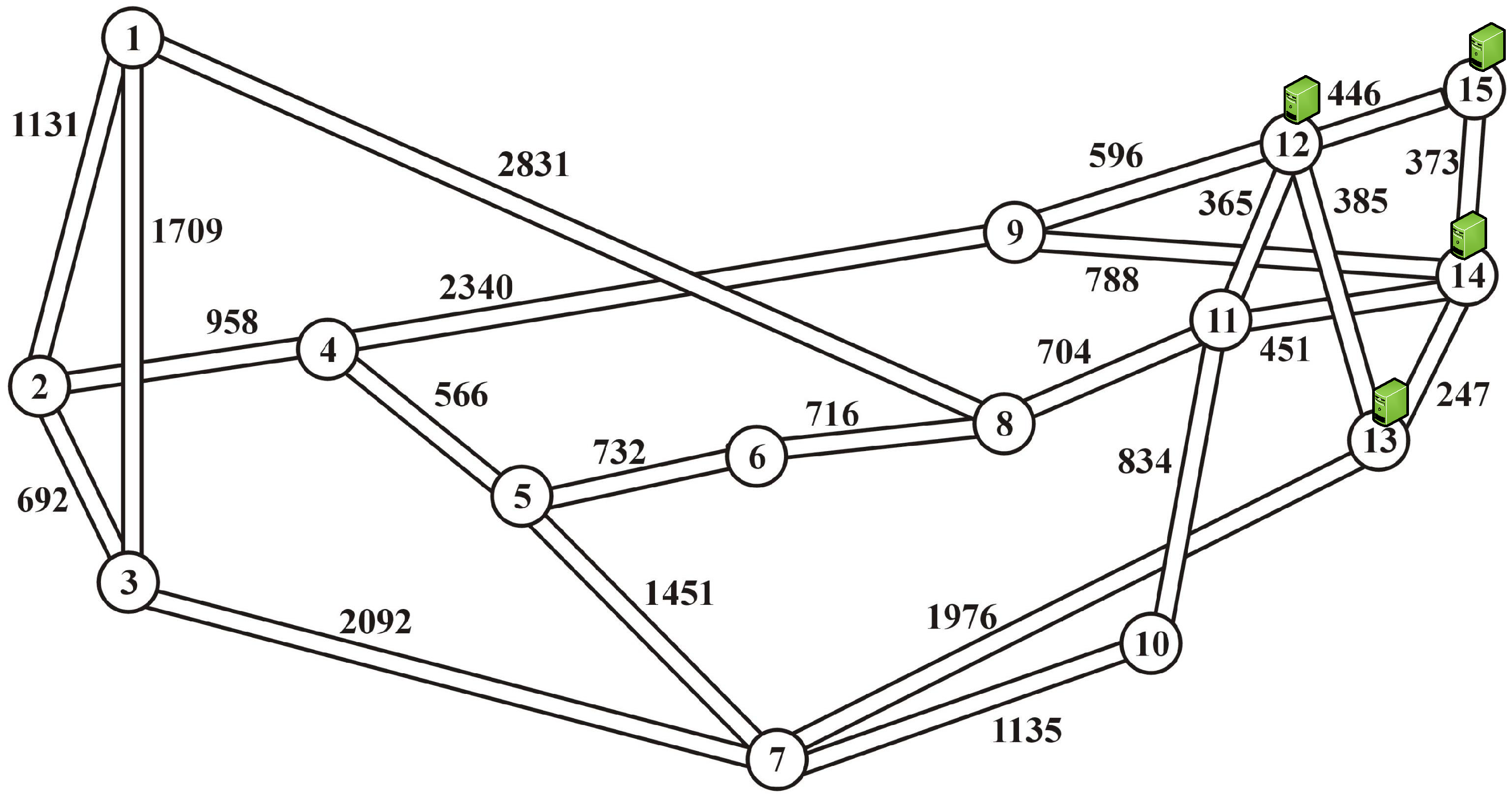

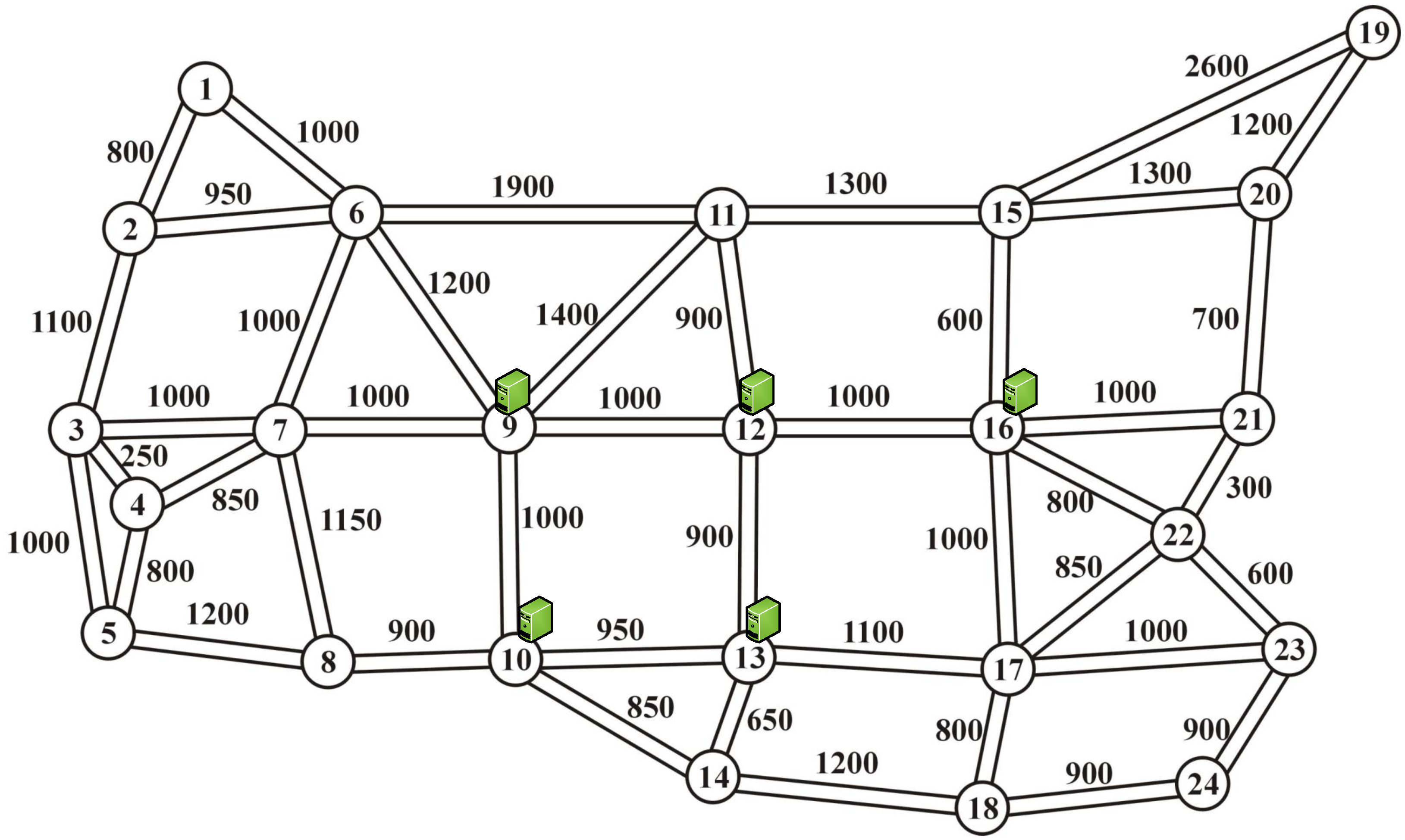

The simulations were conducted in two reference networks: NSF15, consisting of 15 nodes and 46 directed links, and UBN24, consisting of 24 nodes and 86 directed links [

42].

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the NSF15 and UBN24 networks, with link distances marked in kilometers. Detailed parameters for these network topologies are provided in

Table 2. Note that the NSF15 network has an average nodal degree of 3.07, while the UBN24 network has an average nodal degree of 3.58. Furthermore, the links in the NSF15 network are longer, with an average link length of 1022 km, compared to the UBN24 network, where the average link length is 997 km.

For each network, sets of

k candidate paths were calculated, and nodes were selected to generate traffic demands. The candidate paths for each pair of nodes were determined using the

k-shortest path algorithm, based on the length of the link in kilometers. The paths were ordered with the value of their length, and the first

k paths were used for simulations. The selection of designated nodes in the network was determined using a topology-based method, based on the physical topology information of the network. Specifically, we used a method that selects nodes with the lowest average shortest path length to any other network node (

) [

43]. It is shown in

Figure 6 (

12,13,14,15}) for the NSF15 network and

Figure 7 (

9,10,12,13,16}) for the UBN24 network.

Table 3 presents the average nodal degree and the distance between the nodes designated by the topology-based method. It can be seen that nodes

are close to each other, resulting in short distances between the selected nodes to set up AHEOBs.

6.4. Multi-Layer Network Architectures

The multi-layer architecture comprises an EON layer and an IP layer. In particular, the topologies for both the IP and optical layers are identical, meaning that each network node consists of one high-capacity router and one flex-grid switch. Detailed information on the EON and IP layers utilized in the simulation runs is provided in subsequent sections.

6.4.1. EON Layer

The following parameters were established for the EON layer. The optical spectrum of each link was divided into 320 frequency slices, each with a width of 12.5 GHz [

29], with one slice serving as a guard band to separate neighboring connections. The transmission model used in the simulations was based on the “half-distance law”, as described in [

44]. Four modulation formats were considered: BPSK (binary phase-shift keying), QPSK (quadrature phase-shift keying), 8QAM (8-quadrature amplitude modulation), and 16QAM (16-quadrature amplitude modulation).

Table 4 outlines the parameters for these modulation formats, including spectral efficiency, transmission range, and bit rate per slice. These assumptions align with those of [

34,

45,

46,

47]. The chosen parameters (e.g., modulation formats, maximum range) allow lightpaths to be set without regenerators over such long distances between end nodes as in the NSF15 and UBN24 networks.

It is important to note that the transmission ranges of the modulation formats used allow for the establishment of long lightpaths, including AHEOBs, without the need for regeneration. For a given path length, the most spectrally efficient modulation format was selected. Once the modulation format

m was determined, the number of adjacent slices (

) required us to handle the bandwidth demand

between two nodes

s and

t along the physical path considered, and

p was calculated as detailed in [

25,

28,

48]. The number of slices

is calculated as follows:

, where

[Gbit/s] denotes the requested bandwidth,

[bit/s/Hz] represents the spectral efficiency of

m utilized in

p,

[GHz] is the width of the frequency slice, and

is the number of slices for the guard band needed to separate adjacent optical transmissions.

6.4.2. IP Layer

The topology of the virtual layer was predetermined, and each directed virtual link was established via lighpaths that utilized resources visible to the IP layer. For routing purposes in the IP layer, the Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) protocol was employed, leveraging Dijkstra’s algorithm to determine the shortest path from a source node to a destination node. To prevent link saturation, a congestion threshold (th) was introduced. If the capacity usage of a particular virtual link was less than or equal to th, the virtual layer managed the incoming demands. The threshold th was selected based on a thorough analysis of the results obtained with varying threshold values. Initially, we assumed that 160 slices were available on IP links and established the virtual links. Background traffic was then transmitted, resulting in the most heavily loaded link utilizing 66.5% of the link capacity in NSF and 66% in UBN. Subsequent experiments were conducted with threshold values (th) of 0.7, 0.8, and 0.9. For the values chosen th, the AHEOB approach consistently outperformed the reference approach, with optimal results achieved when th was set to 0.7.

6.5. Metrics

Performance indicators for AHEOBs included bandwidth blocking probability (BBP), BBP reduction gain, the average number of hops traversed in the virtual layer, and overall spectrum occupation. These metrics were calculated based on dynamically generated requests. BBP is defined as the ratio of the total bandwidth of all blocked demands to the total bandwidth of all demands (both accepted and rejected). BBP reduction gain is defined as the difference between the BBP of the non-bypass approach and the corresponding AHEOB approach, normalized by the BBP of the non-bypass approach. This gain, expressed as a percentage, indicates the potential improvement in the reduction of BBP when applying AHEOBs. The average number of hops traversed in the virtual layer reflects the number of optical–electrical–optical (O/E/O) conversions and electrical processing steps applied to connections, which is a significant factor contributing to high end-to-end latency. Lastly, overall spectrum occupation refers to the total amount of resources occupied by AHEOBs and those reserved for the IP layer.

The subsequent section presents and discusses the results of extensive numerical experiments conducted to assess the problem of resource allocation in the IP-over-EON network. Any specific assumptions related to particular experiments are provided in the following section.

7. Results

The aim of the numerical experiments detailed in this section is to evaluate the performance of AHEOBs within the IP-over-EON architecture. The AHEOB mechanism is comprehensively described in

Section 4. In the virtual layer, the OSPF protocol was used for IP routing, while the RMSA mechanism was used to establish AHEOBs. Specifically, the SPF and MSEwLSF policies were examined, with the FF spectrum allocation policy applied to resource assignment. Ten candidate paths for AHEOBs were considered. AHEOB approaches were assessed for configurations with 40, 80, 120, and 160 hidden frequency slices, corresponding to 280, 240, 200, and 160 slices available for the IP layer, respectively. The performance of the AHEOB approaches was meticulously compared to a reference (non-bypass) approach, wherein optical resources (320 frequency slices) were fully visible to the IP layer without utilizing AHEOBs. For a given number of slices visible in the IP layer, the virtual link capacity was calculated according to [

25,

28]. In the experiments, two types of traffic were considered. The first type was long-lived background traffic between each pair of nodes, with a bit rate of 200 Gbit/s for the NSF15 network and 80 Gbit/s for the UBN24 network. Background traffic was always handled in the IP layer using OSPF [

25]. For example, when 160 slices were used to establish virtual links, the most loaded link in the IP layer utilized approximately 67% of its capacity in the NSF15 and UBN24 networks. The second type of traffic consisted of dynamic requests generated by the nodes according to the topology-based method. For each pair of selected nodes, demands were uniformly distributed between 50 Gbit/s and 1 Tbit/s, in increments of 50 Gbit/s (with an average value of 525 Gbit) [

49]. Traffic could be transmitted through the IP layer or through AHEOBs.

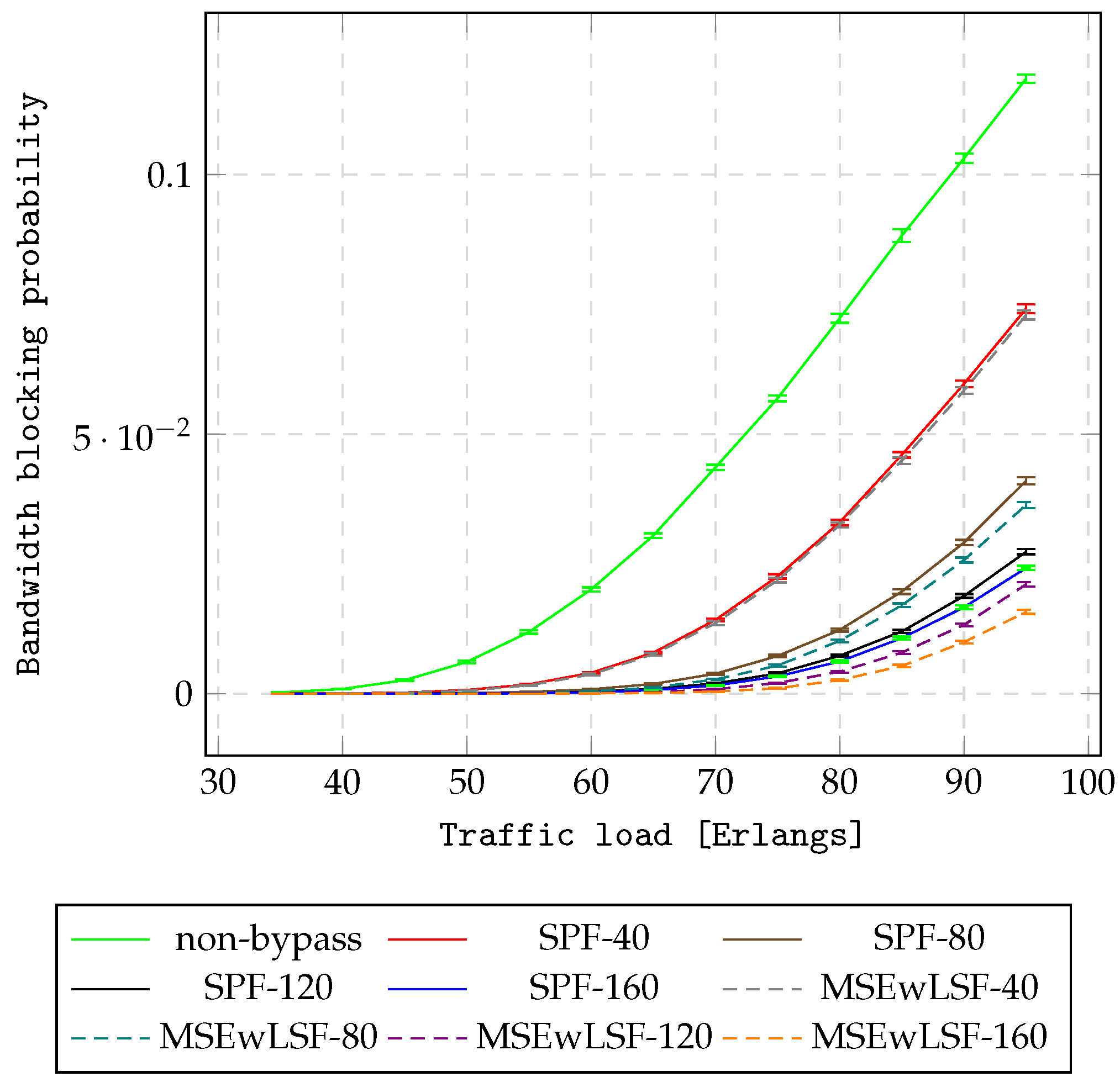

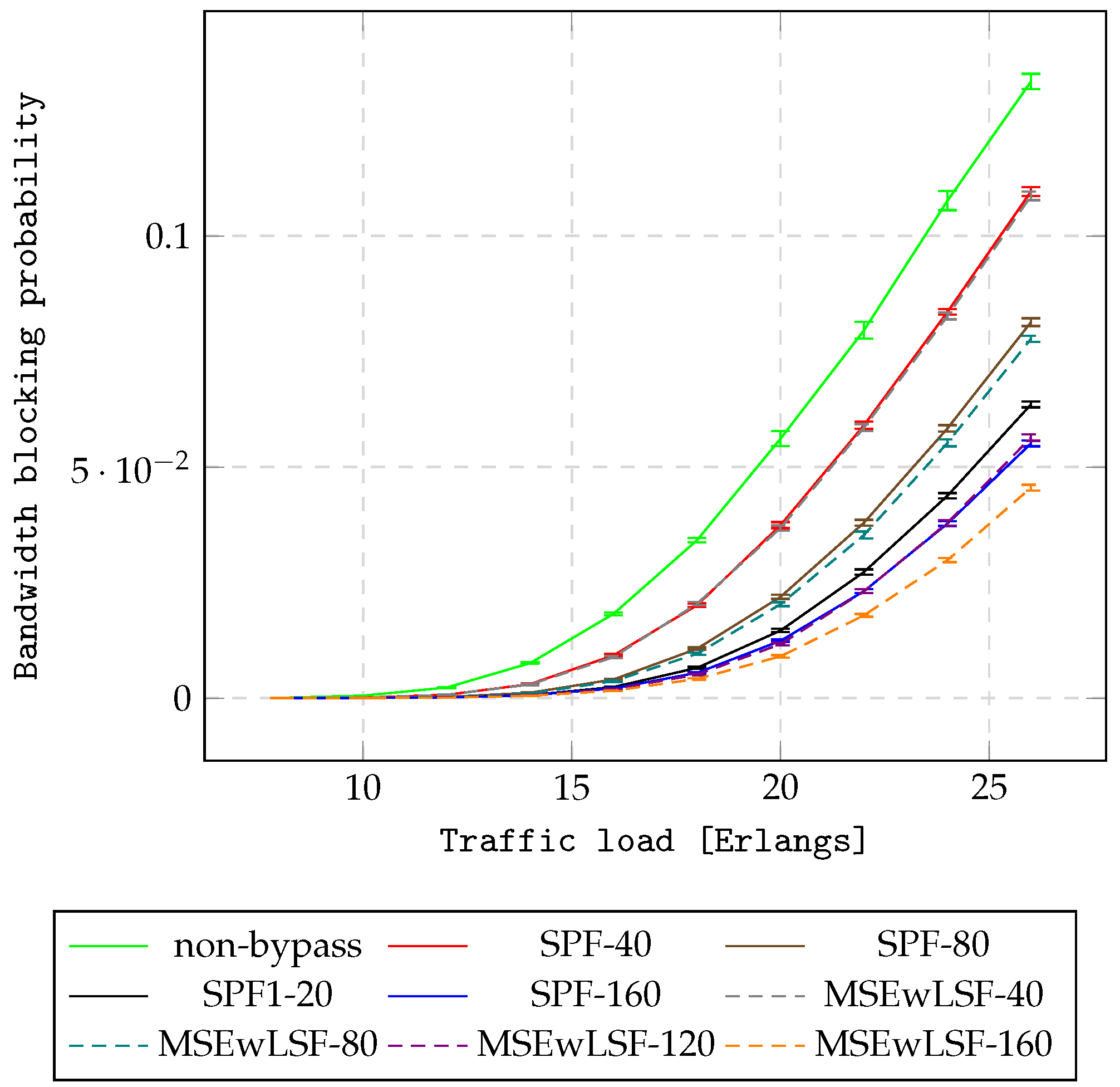

Initially, performance indicators related to BBP are analyzed.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate the BBP metric for all approaches in the NSF15 and UBN24 networks under scenario

.

Table 5 reveals the gain in terms of BBP for AHEOBs compared to the non-bypass in the NSF15 network, while

Table 6 shows the gain in terms of reduction in BBP for AHEOBs compared to the non-bypass in the UBN24 network. The value of 100% is bold to show the best results achieved by the selection policies of the AHEOB. Based on the figures (see

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) and the tables (see

Table 5 and

Table 6), the first clear conclusion is that all AHEOBs provide lower BBP compared to non-bypass for both networks. The result comes from the fact that AHEOB approaches provide the opportunity to consider various paths to send traffic between nodes in networks. In analyzing results for consecutive cases with 40, 80, 120, and 160 hidden slices, it can be seen that the gain of reduction in BBP is higher when there are fewer resources available for the IP layer regardless of load. Since the distance between nodes

is relatively short, the most efficient modulation format can be applied to set up AHEOBs. Therefore, AHEOBs can effectively utilize hidden resources in terms of spectral efficiency. Consequently, AHEOBs for the case with 160 hidden slices achieve the best reduction gain of BBP. Finally, MSEwLSF provides a lower BBP compared to SPF when the same amount of hidden resources is assumed for both networks. This confirms previous findings. MSEwLSF introduces the allocation policy that spreads traffic over a network. Furthermore, if MSEwLSF is applied, the first blocking event occurs for heavier traffic than for SPF. For example, for cases with 40, 80, 120, and 160 hidden slices in the NSF15 network, the first rejection is observed for MSEwLSF under loads of 45, 50, 55, and 60 Erlangs, respectively, while for SPF under loads of 40, 45, 50, and 55 Erlangs. A similar conclusion can be drawn based on the results obtained for the UBN24 network. Namely, for the case of 40 hidden slices, the first rejection is observed for the MSFwLSF-based AHEOB approach under a load of 10 Erlangs, while the first rejection appears earlier if the SPF-based AHEOB approach is applied. For cases of 80 and 120 hidden slices, the first rejection is observed for the MSFwLSF-based AHEOB approach under a load of 12 Erlangs and for the case of 160 hidden slices under a load of 14 Erlangs, while for the three cases of 80, 120, and 160 hidden slices, the first rejection is observed for the SPF-based AHEOB approach under a load of 10 Erlangs.

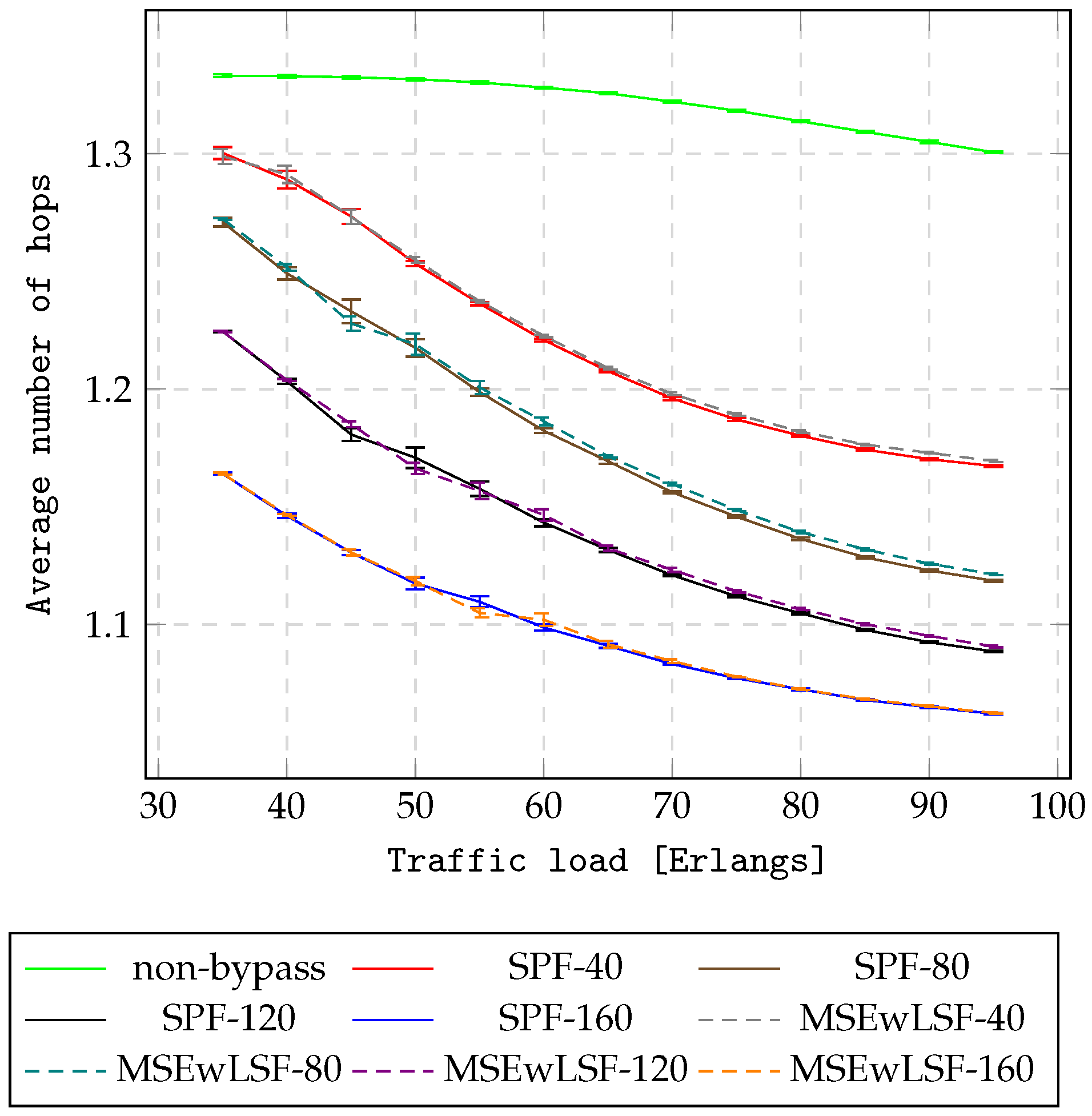

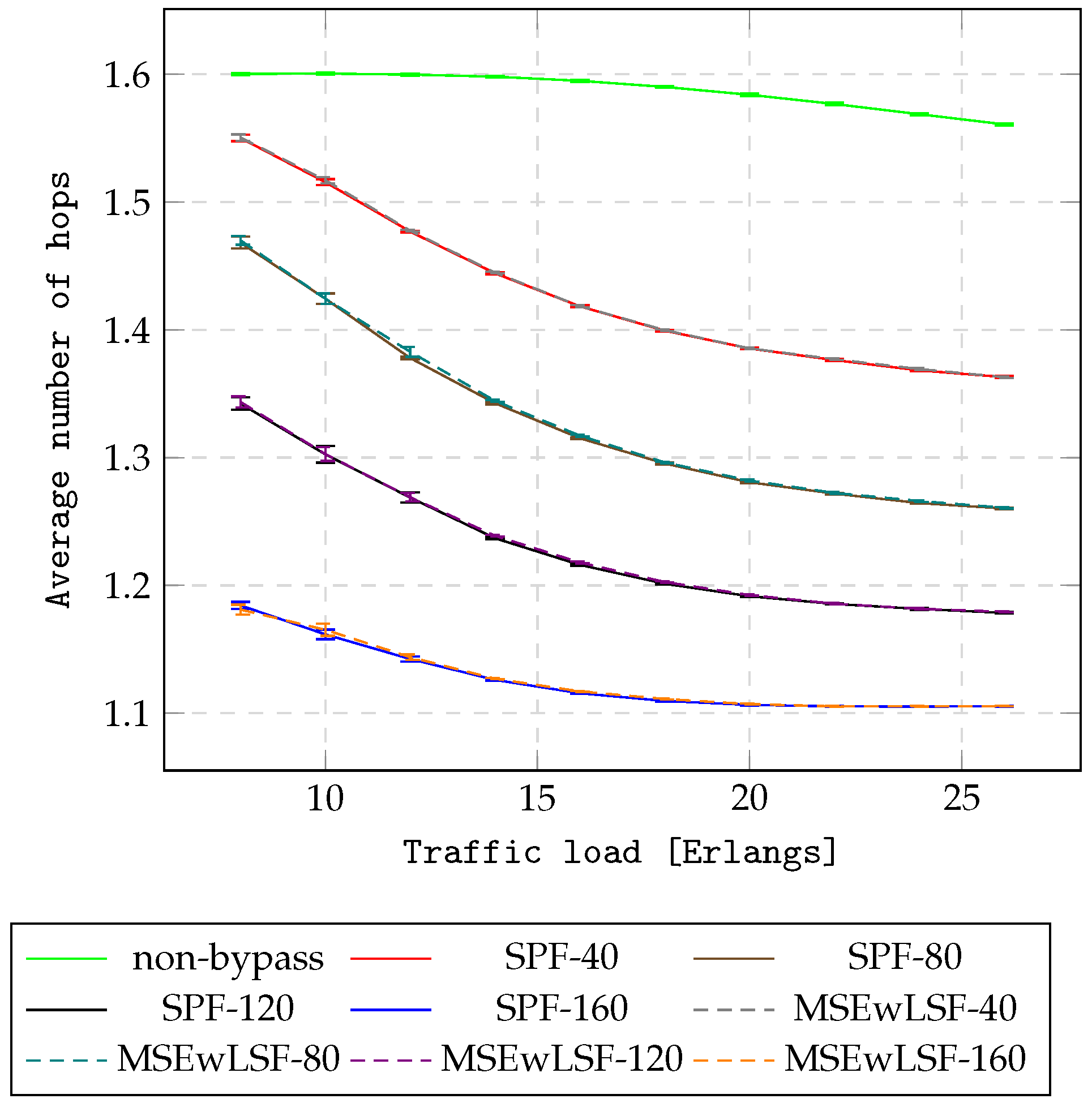

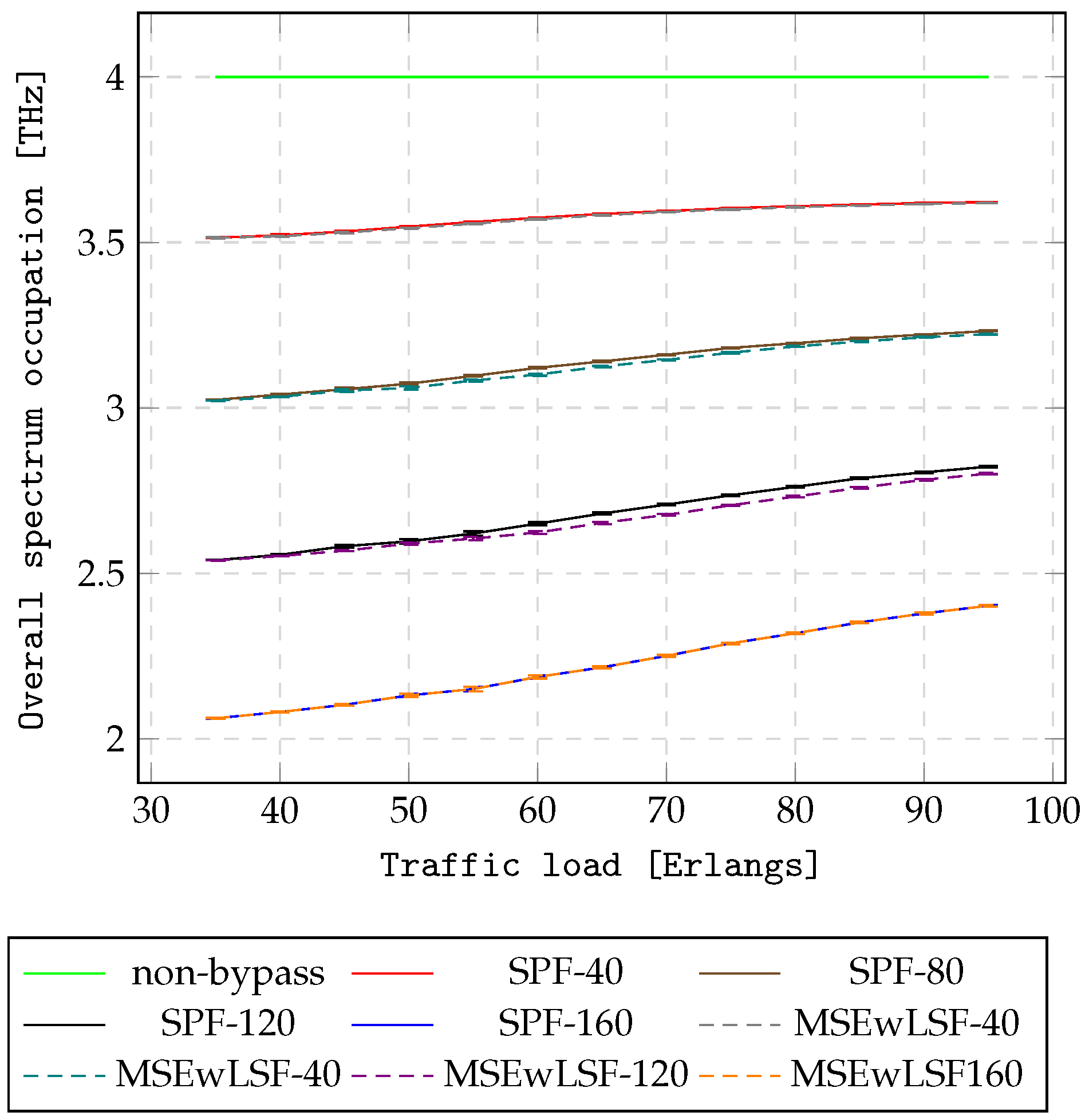

Finally, the metrics of resource utilization for AHEOB and non-bypass approaches are investigated.

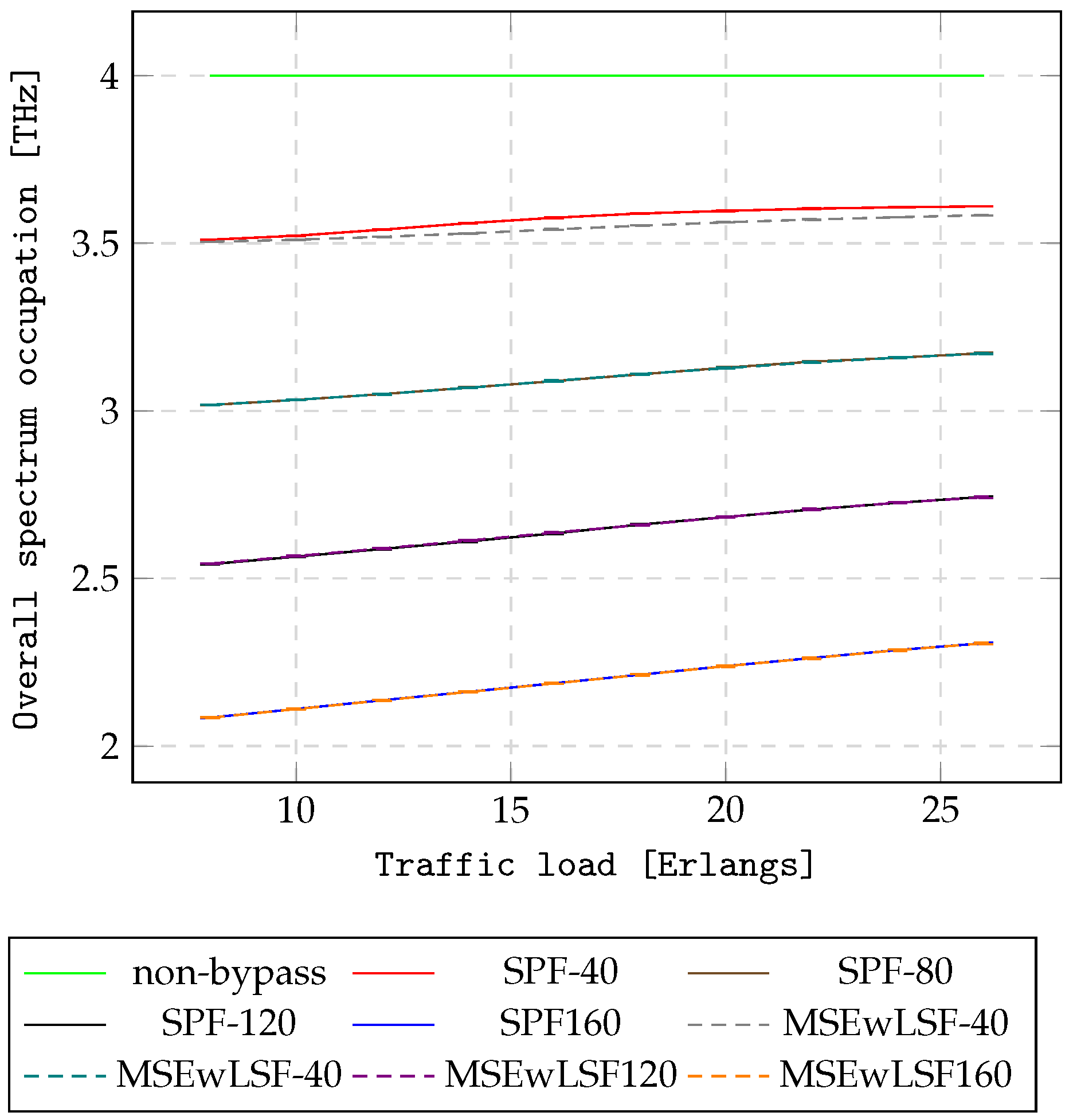

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate the average number of virtual hops traversed in the virtual layer, while

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 present the overall spectrum occupation for the NSF15 and UBN24 networks, respectively. As can be seen, AHEOBs utilize a lower number of hops in terms of O/E/O conversions and consume less spectrum compared to the non-bypass approach in multi-layer networks. The length of an AHEOB is one hop; therefore, the AHEOB approaches minimize the number of hops traversed in the IP layer. Next, AHEOBs utilize spectrum on demand, and only part of the spectrum is utilized constantly by IP. Consequently, the AHEOB approaches reduce the spectrum occupation. In addition, the more resources reserved for the AHEOB approach, the greater the improvement in terms of resource utilization. Consequently, the AHEOBs for a case of 160 hidden slices outperform other cases. Finally, the proposed MSEwLSF utilizes optical resources in a more effective way since MSEwLSF utilizes almost the same amount of spectrum, but sends more traffic than SPF for assuming the number of hidden slices.

In summary, the application of AHEOB reduces BBP and resource utilization in NSF15 and UBN24 networks under scenario . This stems from the fact that the non-bypass utilizes only a single path in the IP layer to handle requests between end nodes. Thus, there is no possibility of omitting links congested in the virtual layer. In all cases of hidden resources, using AHEOB allows one to send more traffic with a lower number of hops in terms of O/E/O conversions compared to the non-bypass approach. It can be assumed that a lower number of O/E/O conversions will have an impact on reducing energy consumption and decreasing network delay. Moreover, the AHEOBs decrease the overall spectrum occupation in multi-layer networks. Finally, the proposed MSEwLSF-based AHEOB approach achieves better performance than the SPF-based AHEOB approach, since MSEwLSF provides AHEOBs in a load-balancing manner. The MSEwLSF-based AHEOB approach can serve more traffic before the first block event occurs.

8. Conclusions

The purpose of the research presented in this article was to reduce the probability of traffic rejection and improve the effectiveness of resource utilization. We proposed the AHEOB solution to manage traffic demands dynamically in multi-layer networks. The AHEOB strategy involves a partial separation of resources between the IP and EON layers. The resources accessible to the IP layer are utilized to establish lightpaths, represented as virtual links, while hidden resources are reserved for directly addressing unexpected traffic within the EON layer. In the virtual layer, single-path routing via the OSPF protocol was employed, simultaneously, the two-step RMSA solution was adapted to set up AHEOBs. This solution includes a path selection policy and the selection of the most spectrally efficient modulation format appropriate for the distance, along with an FF spectrum allocation policy. Specifically, two AHEOB path selection policies were examined: the SPF-based AHEOB approach and the MSEwLSF-based AHEOB approach. The SDN controller ensures a comprehensive view of the network and facilitates cooperation between layers.

The results of extensive numerical experiments were reported. Simulations were carried out using the OMNeT++ simulator under various traffic conditions in two reference topologies, the NSF15 and UBN24 networks. Different proportions of optical resources reserved for AHEOBs and made available to the IP layer were considered. AHEOBs were compared to a reference scenario (referred to as the non-bypass approach), where optical resources were fully visible to the virtual layer. The simulation results indicate that all AHEOB approaches provide improvements in terms of BBP, reduce the average number of hops per accepted demand, and decrease the overall spectrum occupation compared to the reference approach. Furthermore, the MSEwLSF-based AHEOB approach achieves a better reduction in BBP than the SPF-based AHEOB approach. In conclusion, AHEOBs can absorb unexpected traffic load fluctuations and address congestions when IP-layer resources are insufficient, while also providing resource savings in multi-layer networks. The proposed AHEOB solution addresses traffic fluctuation in multi-layer networks by operating across both virtual and EON layers. Evaluations using IP-over-EON simulation modules in OMNeT++ show that AHEOB approaches reduce blocking probability and resource use, including fewer IP-layer hops and less spectrum occupation, making them suitable for networks with highly unpredictable traffic fluctuations.

Several issues can be addressed in future studies. Firstly, strategies can be developed to optimize virtual topology planning or compare AHEOB with adaptive routing or SDN-based congestion control mechanisms. Secondly, existing traffic can be rerouted through newly established AHEOBs to regain the capacity of virtual links. Additionally, spatial–spectral resources could be concealed and subsequently utilized to create AHEOBs. Since the diversification of resources renders AHEOBs transparent to the IP layer, routing tables in routers do not require updates when a new AHEOB is established, making AHEOBs more appealing to network operators. Finally, AHEOBs are fully compatible with the SDN concept, allowing their implementation in the SDN control plane to efficiently utilize the resources of IP-over-EON networks.