Wastewater Valorisation in Sustainable Productive Systems: Aquaculture, Urban, and Swine Farm Effluents Hydroponics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

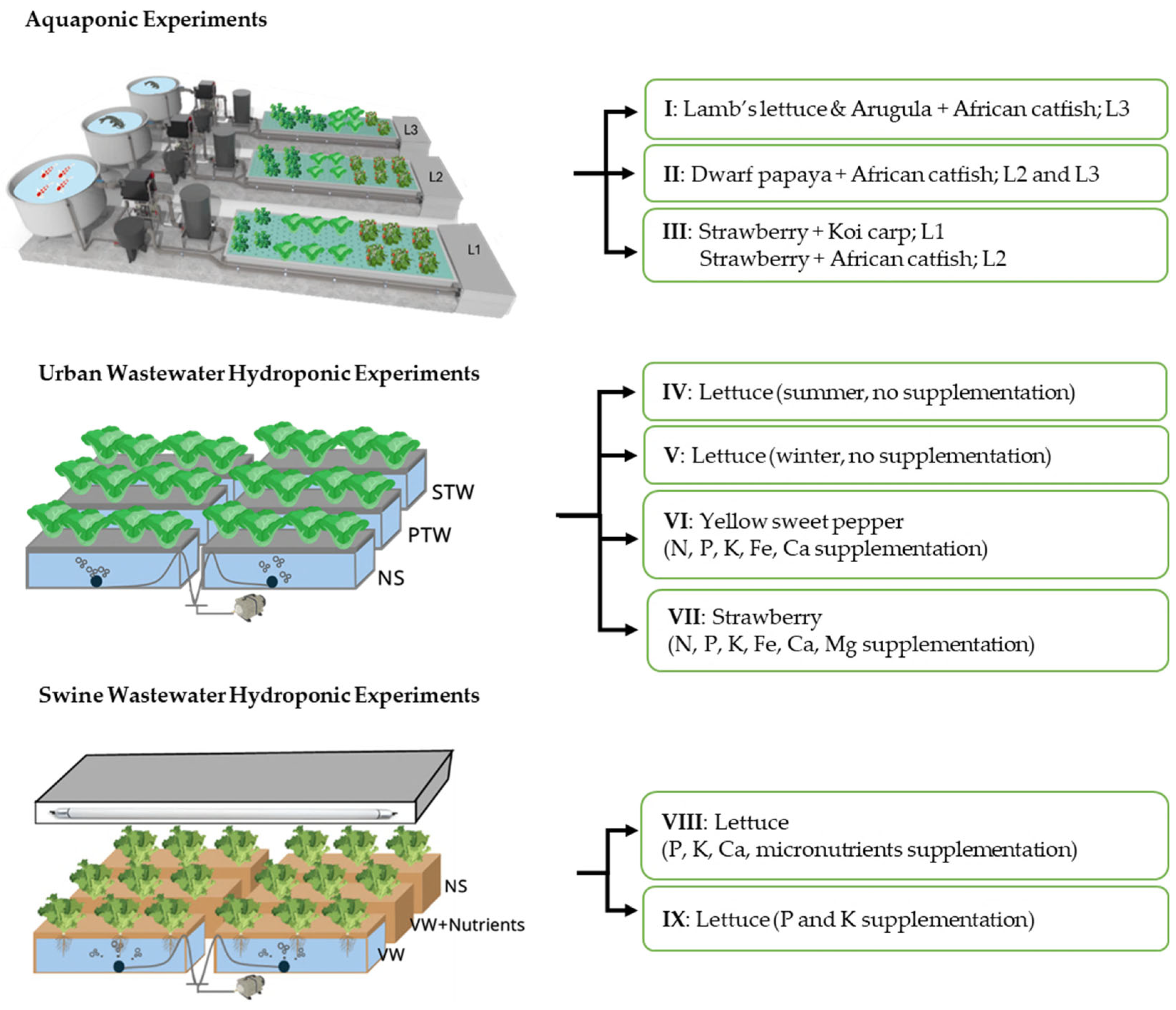

2.1. Aquaponic Experiments (I–III)

2.2. Urban Wastewater Hydroponic Experiments (IV–VII)

2.3. Swine Farm Wastewater Hydroponic Experiments (VII and IX)

2.4. Wastewater Quality Monitoring

2.5. Water Consumption

2.6. Crop Monitoring

2.7. Product Safety Monitoring Parameters

2.8. Greenhouse Environmental Conditions

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Aquaponic Systems Production

3.2. Urban Wastewater Hydroponic Production

3.3. Swine Farm Wastewater Hydroponic Production

3.4. Analysis of Productivity Across Sustainable Systems

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kundu, D.; Dutta, D.; Samanta, P.; Dey, S.; Sherpa, K.C.; Kumar, S.; Dubey, B.K. Valorization of Wastewater: A Paradigm Shift towards Circular Bioeconomy and Sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2024: Water for Prosperity and Peace; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2024; ISBN 9789231006579.

- Mai, C.; Mojiri, A.; Palanisami, S.; Altaee, A.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, J.L. Wastewater Hydroponics for Pollutant Removal and Food Production: Principles, Progress and Future Outlook. Water 2023, 15, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2025: Mountains and Glaciers: Water Towers; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2025; ISBN 978-92-3-100743-9.

- Morão, H. The Economic Consequences of Fertilizer Supply Shocks. Food Policy 2025, 133, 102835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Zeller, V. Nutrient Circularity from Waste to Fertilizer: A Perspective from LCA Studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 965, 178623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Wastewater: Turning Problem to Solution—A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; ISBN 9789280740615.

- Marin, E.; Rusănescu, C.O. Agricultural Use of Urban Sewage Sludge from the Wastewater Station in the Municipality of Alexandria in Romania. Water 2023, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; He, T.; Zhang, Y. Treatment and Utilization of Swine Wastewater—A Review on Technologies in Full-Scale Application. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, D.; Mariappan, N.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Di Dong, C.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Biological Treatment of Swine Wastewater—Conventional Methods versus Microalgal Processes. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 177, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136364-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yep, B.; Zheng, Y. Aquaponic Trends and Challenges—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwaza, S.T.; Magwaza, L.S.; Odindo, A.O.; Mditshwa, A. Hydroponic Technology as Decentralised System for Domestic Wastewater Treatment and Vegetable Production in Urban Agriculture: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.A.C.; Chu, T.S.C.; Jacob, L.H.M.; Rulloda, L.A.R.; Ambrosio, A.Z.M.H.; Sy, A.C.; Vicerra, R.R.P.; Choi, A.E.S.; Dadios, E.P. An Automated Small-Scale Aquaponics System Design Using a Closed Loop Control. Environ. Chall. 2025, 19, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Gonzalez, R.S.; Garcia-Garcia, A.L.; Ventura-Zapata, E.; Barceinas-Sanchez, J.D.O.; Sosa-Savedra, J.C. A Review on Hydroponics and the Technologies Associated for Medium-and Small-Scale Operations. Agriculture 2022, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, M.; Elavarasan, G.; Balamurugan, A.; Dhanusiya, B.; Freedon, D. Hydroponic Farming—A State of Art for the Future Agriculture. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 68, 2163–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Torres, L.; Mendoza-Espinosa, L.G.; Correa-Reyes, G.; Daesslé, L.W. Hydroponics with Wastewater: A Review of Trends and Opportunities. Water Environ. J. 2020, 35, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winker, M.; Fischer, M.; Bliedung, A.; Bürgow, G.; Germer, J.; Mohr, M.; Nink, A.; Schmitt, B.; Wieland, A.; Dockhorn, T. Water Reuse in Hydroponic Systems: A Realistic Future Scenario for Germany? Facts and Evidence Gained during a Transdisciplinary Research Project. J. Water Reuse Desalin. 2020, 10, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.; Ribeiro, C.; Carvalho, M.J.; Correia, T.; Correia, P.; Regato, M.; Costa, I.; Fernandes, A.; Almeida, A.; Lopes, A.; et al. Pretreated Agro-Industrial Effluents as a Source of Nutrients for Tomatoes Grown in a Dual Function Hydroponic System: Tomato Quality Assessment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyde-Smith, D.; Campos, L.C. Engineering Hydroponic Systems for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Plant Growth. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hamedi, F.; Karthishwaran, K.; Alyafei, M.A.M. Hydroponic Wheat Production Using Fresh Water and Treated Wastewater under the Semi-Arid Region. Emirates J. Food Agric. 2021, 33, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecht, S.A.; Kong, X.; Xia, X.R.; Shea, D.; Nichols, E.G. Non-Target and Suspect-Screening Analyses of Hydroponic Soybeans and Passive Samplers Exposed to Different Watershed Irrigation Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 153754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, O.; Vieira, J.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Sousa, H.P. Ornamental Plants for Urban Wastewater Hydroponic Treatment BT. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference (ICoWEFS 2024), Portalegre, Portugal, 8–10 May 2024; Duque de Brito, P.S., da Costa Sanches Galvão, J.R., de Amorim Almeida, H., de Jesus Gomes, R., Mota Panizio, R., de Jesus Martins Mourato, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa, H.; Ogata, Y.; Hachiya, Y.; Tokura, K.; Kuroda, M.; Inoue, D.; Toyama, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Mori, K.; Morikawa, M.; et al. Enhanced Biomass Production and Nutrient Removal Capacity of Duckweed via Two-Step Cultivation Process with a Plant Growth-Promoting Bacterium, Acinetobacter Calcoaceticus P23. Chemosphere 2020, 238, 124682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, L.; Cavalera, M.A.; Serrapica, F.; Di Francia, A.; Masucci, F.; Carelli, G. Use of Reclaimed Urban Wastewater for the Production of Hydroponic Barley Forage: Water Characteristics, Feed Quality and Effects on Health Status and Production of Lactating Cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1274466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuzig, R.; Haller-Jans, J.; Bischoff, C.; Leppin, J.; Germer, J.; Mohr, M.; Bliedung, A.; Dockhorn, T. Reclaimed Water Driven Lettuce Cultivation in a Hydroponic System: The Need of Micropollutant Removal by Advanced Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 50052–50062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, P.; Nicoletto, C.; Giro, A.; Pii, Y.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Lugli, P.; Orzes, G.; Mazzetto, F.; Astolfi, S. Hydroponic Solutions for Soilless Production Systems: Issues and Opportunities in a Smart Agriculture Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 2020 on Minimum Requirements for Water Reuse. Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, 177, 32–55. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater—Volume 2: Wastewater Use in Agriculture; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 92-4-154683-2. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Saraswat, S. Vermifiltration as a Natural, Sustainable and Green Technology for Environmental Remediation: A New Paradigm for Wastewater Treatment Process. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungruaiklang, N.; Iwai, C.B. Using Vermiwash to Enhance Performance of Small-Scale Vermifiltration for Swine Farm Wastewater. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 3323–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Samal, K.; Dash, R.R.; Bhunia, P. Vermifiltration as a Sustainable Natural Treatment Technology for the Treatment and Reuse of Wastewater: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 247, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Bhunia, P.; Dash, R.R. A Mechanistic Review on Vermifiltration of Wastewater: Design, Operation and Performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Robin, P.; Cluzeau, D.; Bouché, M.; Qiu, J.P.; Laplanche, A.; Hassouna, M.; Morand, P.; Dappelo, C.; Callarec, J. Vermifiltration as a Stage in Reuse of Swine Wastewater: Monitoring Methodology on an Experimental Farm. Ecol. Eng. 2008, 32, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispolnov, K.; Aires, L.M.I.; Lourenço, N.D.; Vieira, J.S. A Combined Vermifiltration-Hydroponic System for Swine Wastewater Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispolnov, K.; Luz, T.M.R.; Aires, L.M.I.; Vieira, J.S. Progress on the Use of Hydroponics to Remediate Hog Farm Wastewater after Vermifiltration Treatment. Water 2024, 16, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, S.; Stejskal, V.; Toner, D.; Jansen, M.A.K. Wastewater Valorisation in an Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture System; Assessing Nutrient Removal and Biomass Production by Duckweed Species. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 302, 119059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, D.; Won, E.; Timmons, M.B.; Mattson, N. Complementary Nutrients in Decoupled Aquaponics Enhance Basil Performance. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Kim, H.J.; Thatcher, L.R.; Hamilton, J.M.; Alva, M.L.; Zhou, Z.; Brown, P.B. Maximizing Nutrient Recovery from Aquaponics Wastewater with Autotrophic or Heterotrophic Management Strategies. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 21, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, I.L.; Nicol, W. Nitrogen Management in Nitrification-Hydroponic Systems by Utilizing Their PH Characteristics. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, A.; Kashem, M.; Das, P.; Hawari, A.H.; Mehariya, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Shoyeb, T.; Abduquadir, M.; Al, H. Aquaculture from Inland Fish Cultivation to Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio Technol. 2023, 22, 969–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yogev, U.; Keesman, K.J.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Gross, A. Integrated Hydroponics Systems with Anaerobic Supernatant and Aquaculture Effluent in Desert Regions: Nutrient Recovery and Benefit Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atique, F.; Lindholm-Lehto, P.; Pirhonen, J. Is Aquaponics Beneficial in Terms of Fish and Plant Growth and Water Quality in Comparison to Separate Recirculating Aquaculture and Hydroponic Systems? Water 2022, 14, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, L.A.; Shaghaleh, H.; El-Kassar, G.M.; Abu-Hashim, M.; Elsadek, E.A.; Alhaj Hamoud, Y. Aquaponics: A Sustainable Path to Food Sovereignty and Enhanced Water Use Efficiency. Water 2023, 15, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomoni, D.I.; Koukou, M.K.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Vasiliadis, L. A Review of Hydroponics and Conventional Agriculture Based on Energy and Water Consumption, Environmental Impact, and Land Use. Energies 2023, 16, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, T.; Mohtar, R.H.; Abou Jaoude, L.; Yanni, S.F. Treated Wastewater Reuse for Irrigation in a Semi-Arid Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 966, 178579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastião, F.; Vaz, D.C.; Pires, C.L.; Cruz, P.F.; Moreno, M.J.; Brito, R.M.M.; Cotrim, L.; Oliveira, N.; Costa, A.; Fonseca, A. Nutrient-efficient Catfish-based Aquaponics for Producing Lamb’s Lettuce at Two Light Intensities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 6541–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanes, A.R.; Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R. Towards Automated Aquaponics: A Review on Monitoring, IoT, and Smart Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, C.; Cohen, M.; Pantanella, E.; Stankus, A.; Lovatelli, A. Producción de Alimentos En Acuaponía a Pequeña Escala—Cultivo Integral de Peces y Plantas; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-135809-2. [Google Scholar]

- Al Meselmani, M.A. Nutrient Solution for Hydroponics. In Recent Research and Advances in Soilless Culture; Metin, T., Sanem, A., Ertan, Y., Adem, G., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-80355-169-2. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, R.d.S.C.; Bastos, R.G.; Souza, C.F. Influence of the Use of Wastewater on Nutrient Absorption and Production of Lettuce Grown in a Hydroponic System. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, O.; Vaz, D.; Sebastião, F.; Sousa, H.; Vieira, J. Wastewater as a Nutrient Source for Hydroponic Production of Lettuce: Summer and Winter Growth. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 301, 108966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, L.M.I.; Ispolnov, K.; Luz, T.R.; Pala, H.; Vieira, J.S. Optimization of an Indoor DWC Hydroponic Lettuce Production System to Generate a Low N and P Content Wastewater. Processes 2023, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6060:1989; Water Quality—Determination of Chemical Oxygen Demand, 2nd ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989.

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water & Wastewater, 21st ed.; Eaton, A.D., Clesceri, L.S., Rice, E.W., Greenberg, A.E., Eds.; American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation: Washington DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9308-1; Water Quality—Enumeration of Escherichia Coli and Coliform, 3rd ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Primitivo, M.J.; Neves, M.; Pires, C.L.; Cruz, P.F.; Brito, C.; Rodrigues, A.C.; de Carvalho, C.C.C.R.; Mortimer, M.M.; Moreno, M.J.; Brito, R.M.M. Edible Flowers of Helichrysum Italicum: Composition, Nutritive Value, and Bioactivities. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Yang, T.; Kim, H.J. PH Dynamics in Aquaponic Systems: Implications for Plant and Fish Crop Productivity and Yield. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimuk, A.A.; Beketov, S.V.; Kalita, T.L. Physiological and Ecological Features of Cultivation African Catfish Clarias Gariepinus. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2024, 14, S326–S335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. Nutrient Solutions for Hydroponic Systems. In Hydroponics—A Standard Methodology for Plant Biological Researches; Asao, T., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-953-51-0386-8. [Google Scholar]

- Krastanova, M.; Sirakov, I.; Ivanova-Kirilova, S.; Yarkov, D.; Orozova, P. Aquaponic Systems: Biological and Technological Parameters. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2022, 36, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, X.; Jia, X.; Liu, L.; Cao, H.; Qin, W.; Li, M. Iron Deficiency Leads to Chlorosis Through Impacting Chlorophyll Synthesis and Nitrogen Metabolism in Areca catechu L. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 710093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Samarakoon, U.; Altland, J.; Ling, P. Photosynthesis, Biomass Production, Nutritional Quality, and Flavor-Related Phytochemical Properties of Hydroponic-Grown Arugula (Eruca sativa Mill.) ‘Standard’ under Different Electrical Conductivities of Nutrient Solution. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Islam, N.; Mustaki, S.; Uddain, J.; Azad, M.O.K.; Choi, K.Y.; Naznin, M.T. Evaluation of the Different Low-Tech Protective Cultivation Approaches to Improve Yield and Phytochemical Accumulation of Papaya (Carica Papaya L.) in Bangladesh. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endut, A.; Lananan, F.; Abdul Hamid, S.H.; Jusoh, A.; Wan Nik, W.N. Balancing of Nutrient Uptake by Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) and Mustard Green (Brassica juncea) with Nutrient Production by African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) in Scaling Aquaponic Recirculation System. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 29531–29540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.S.; Brown, P.B. Current Status of the Propagation of Basil in Aquaponic Systems: A Literature Review. Aquac. Res. 2025, 2025, 1320019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Mishra, A.K.; Shah, S.N.; Bhat, M.A.; Jan, S.; Rahman, S.; Baek, K.-H.; Jan, A.T. Soil and Mineral Nutrients in Plant Health: A Prospective Study of Iron and Phosphorus in the Growth and Development of Plants. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5194–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottoson, J.; Norström, A.; Dalhammar, G. Removal of Micro-organisms in a Small-scale Hydroponics Wastewater Treatment System. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 40, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.; Sinlawatpongsakul, C.; Somngam, N.; Phunumkhang, P.; Pengchai, P. Removal of Turbidity, COD and Coliform Bacteria in Duck-Pond Water by Hydroponic Water Convolvulus Gardening. Thai Environ. Eng. J. 2022, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tytła, M. Identification of the Chemical Forms of Heavy Metals in Municipal Sewage Sludge as a Critical Element of Ecological Risk Assessment in Terms of Its Agricultural or Natural Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobczak-Samburska, A.; Pióro-Jabrucka, E.; Przybył, J.L.; Sieczko, L.; Kalisz, S.; Gajc-Wolska, J.; Kowalczyk, K. Effect of Foliar Application of Calcium and Salicylic Acid on Fruit Quality and Antioxidant Capacity of Sweet Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.) in Hydroponic Cultivation. Agriculture 2025, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanas, A.L.; Khamis, M.A.I. Effect of Some Soilless Culture Systems on Growth and Productivity of Strawberry Plants. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Protection Agency Guidelines for Assessing the Microbiological Safety of Ready-to-Eat Foods Placed on the Market; Health Protection Agency: London, UK, 2009.

- Roberts, J.M.; Bruce, T.J.A.; Monaghan, J.M.; Pope, T.W.; Leather, S.R.; Beacham, A.M. Vertical Farming Systems Bring New Considerations for Pest and Disease Management. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2020, 176, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, D.L.; Saylor, L.; Turkon, P. Total Coliform and Generic E. Coli Levels, and Salmonella Presence in Eight Experimental Aquaponics and Hydroponics Systems: A Brief Report Highlighting Exploratory Data. Horticulturae 2020, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankwa, A.S.; Machado, R.M.; Perry, J.J. Sources of Food Contamination in a Closed Hydroponic System. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, D.; Kusmayadi, A.; Yen, H.-W.; Dong, C.-D.; Lee, D.-J.; Chang, J.-S. Current Advances in Biological Swine Wastewater Treatment Using Microalgae-Based Processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, A.; Williams, K.A. Comparison of Hydroponic Butterhead Lettuce Grown in Reject Water from a Reverse Osmosis System, Municipal Water, and Purified Water. HortScience 2024, 59, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, G.; Orsini, F.; Blasioli, S.; Cellini, A.; Crepaldi, A.; Braschi, I.; Spinelli, F.; Nicola, S.; Fernandez, J.A.; Stanghellini, C.; et al. Resource Use Efficiency of Indoor Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.) Cultivation as Affected by Red: Blue Ratio Provided by LED Lighting. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelon, N.; Pennisi, G.; Ohn Myint, N.; Orsini, F.; Gianquinto, G. Strategies for Improved Water Use Efficiency (WUE) of Field-Grown Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.) under a Semi-Arid Climate. Agronomy 2020, 10, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoor, M.; Arenas-Salazar, A.P.; Parra-Pacheco, B.; García-Trejo, J.F.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Rico-García, E. Horticultural Irrigation Systems and Aquacultural Water Usage: A Perspective for the Use of Aquaponics to Generate a Sustainable Water Footprint. Agriculture 2024, 14, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizaeh, P.; Sodaeizade, H.; Arani, A.M.; Hakimzadeh, M.A. Comparing Yield, Nutrient Uptake and Water Use Efficiency of Nasturtium Officinale Cultivated in Aquaponic, Hydroponic, and Soil Systems. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanidou, M.; Elvanidi, A.; Mourantian, A.; Levizou, E.; Mente, E.; Katsoulas, N. Evaluation of Productivity and Efficiency of a Large-Scale Coupled or Decoupled Aquaponic System. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Mizyed, N.; Masoud, M. Evaluation of Gradual Hydroponic System for Decentralized Wastewater Treatment and Reuse in Rural Areas of Palestine. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2012, 5, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, A.; Tao, W. Production of Natural Fertilizers with Sludge Digestate by Mineral-Based Struvite Crystallization and Organic Binding. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, K.; Kujawa-Roeleveld, K.; Schoenmakers, M.; Datta, D.K.; Rijnaarts, H.; Vos, J. Institutional Challenges and Stakeholder Perception towards Planned Water Reuse in Peri-Urban Agriculture of the Bengal Delta. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C.; Georgiou, I.; Guenther, E.; Caucci, S. Barriers in Implementation of Wastewater Reuse: Identifying the Way Forward in Closing the Loop. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nutrient Salt | Chemical Formula | Experiment VI | Experiment VII | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTW | STW | PTW | STW | ||

| Potassium nitrate | KNO3 | 481.3 | 481.3 | 353.8 | 375.0 |

| Calcium nitrate | Ca (NO3)2 | 85.4 | 108.5 | 1069.7 | 1145.5 |

| Monopotassium phosphate | KH2PO4 | 150.1 | 153.0 | 250.3 | 248.9 |

| Magnesium sulphate heptahydrate | MgSO4·7H2O | -- | -- | 438.0 | 438.0 |

| EDTA iron (III) sodium salt | C10H12FeN2NaO8 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 13.1 | 13.1 |

| Parameter | Aquaponic Systems | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | |

| pH | 5.5–6.4 | 5.1–6.7 | 5.1–7.3 |

| T (°C) | 12.6–24.1 | 14.8–28.1 | 15.2–27.9 |

| DO (mg/L) | 5.8–10.7 | 5.0–10.3 | 5.0–8.3 |

| EC (µS/cm) | 1209–1485 | 1294–2890 | 171–2000 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 600–742 | 636–1990 | 92–1393 |

| BOD5 (mg/L) | n.m. | n.m. | n.m. |

| COD (mg/L) | n.m. | n.m. | n.m. |

| P-PO4 (mg/L) | 7.0–10.9 | 14.7–63.4 | 1.2–52.3 |

| N-NH4 (mg/L) | <0.05 *–0.22 | <0.05 *–0.30 | <0.05 *–0.24 |

| N-NO3 (mg/L) | 78–124 | 153–1029 | 12.7–617 |

| K (mg/L) | 231.2–298.4 | 203.1–422 | 3.0–256 |

| Fe (mg/L) | 0.08–2.10 | <0.10 *–1.10 | <0.10 *–0.20 |

| Coliform (CFU/100 mL) | 1.7 × 104–3.3 × 104 | 3.0 × 104 ** | 3.2 × 104–7.2 × 104 |

| E. coli (CFU/100 mL) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Experiment | Crop | Growth/Yield Parameter | Aquaponic System | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | |||

| I | Lamb’s lettuce | height (cm) | N/A | N/A | 7 ± 2 |

| g/plant | 108 ± 1 | ||||

| Arugula | height (cm) | 7.2 ± 2 | |||

| g/plant | 79 ± 1 | ||||

| II | Papayas trees | height (cm) | N/A | 169 ± 36 a | 147 ± 56 b |

| fruit/plant | 6 ± 2 a | 8 ± 4 a | |||

| g/plant * | 7054 ± 2421 a | 10047 ± 8791 a | |||

| III | Strawberry plants | height (cm) | 8 ± 1 b | 11 ± 3 a | N/A |

| fruit/plant | 5 ± 2 b | 8 ± 4 a | |||

| g/plant * | 66 ± 37 b | 125 ± 60 a | |||

| Parameter | Wastewater | |

|---|---|---|

| PTW | STW | |

| pH | 6.9–8.8 | 8.5–8.6 |

| T (°C) | 12–25 | 12–27 |

| DO (mg/L) | 6.9–8.8 | 8.2–8.3 |

| EC (µS/cm) | 500–932 | 479–685 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 405–566 | 322–343 |

| BOD5 (mg/L) | 65–114 | 3.7–13 |

| COD (mg/L) | 94–247 | <30 *–89 |

| P-PO4 (mg/L) | 2.6–5.8 | 2.6–6.8 |

| N-NH4 (mg/L) | 24–52 | <0.05 *–3.0 |

| N-NO3 (mg/L) | <1.0 *–67 | 4.5–86 |

| K (mg/L) | 15–92 | 15–85 |

| Fe (mg/L) | <0.10 * | <0.10 * |

| Coliform (CFU/100 mL) | 3.0 × 105–6.1 × 106 | 3.9 × 104–1.3 × 105 |

| E. coli (CFU/100 mL) | 1.3 × 105–2.0 × 106 | 6.7 × 103–6.0 × 104 |

| Experiment | Crop | Growth/Yield Parameter | Hydroponic Solution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | PTW | STW | |||

| IV | Lettuce (summer) | height (cm) | 25 ± 2 a | 13 ± 2 cb | 15 ± 4 b |

| g/plant | 134 ± 21 a | 27 ± 10 c | 54 ± 29 b | ||

| V | Lettuce (winter) | height (cm) | 23 ± 2 a | 17 ± 3 b | 15 ± 2 c |

| g/plant | 123 ± 10 a | 65 ± 6 b | 49 ± 14 c | ||

| VI | Sweet peppers | height (cm) | 81 ± 23 a | 65 ± 16 ab | 55 ± 12 cb |

| fruit/plant | 1.8 ± 0.7 a | 2.0 ± 0.8 a | 1.3 ± 0.5 a | ||

| g/plant * | 189 ± 103 a | 190 ± 79 a | 127 ± 37 a | ||

| VII | Strawberry plants | height (cm) | 10 ± 2 c | 20 ± 3 a | 20 ± 1 ab |

| fruit/plant | 12 ± 4 a | 12 ± 4 a | 10 ± 3 a | ||

| g/plant * | 177 ± 71 a | 183 ± 74 a | 179 ± 43 a | ||

| Parameter | Wastewater | |

|---|---|---|

| SWW | VW | |

| pH | 7.7–8.8 | 5.6–8.1 |

| T (°C) | 17.0–20.0 | 20.0–20.4 |

| EC (µS/cm) | 6.6 × 103–1.7 × 104 | 1.4 × 103–1.9 × 103 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 3.3 × 103–8.2 × 103 | 6.5 × 102–1.2 × 103 |

| DO (mg/L) | 0.02–3.39 | 1.2–9.2 |

| BOD5 (mg/L) | 100–863 | 4.6–33.1 |

| COD (mg/L) | 4.6 × 103–5.7 × 103 | 1.9 × 102–2.2 × 102 |

| P-PO4 (mg/L) | 6.9–17.6 | 3.4–29.3 |

| N-NH4 (mg/L) | 662–1465 | 0.4–67.7 |

| N-NO3 (mg/L) | 3.9–11.5 | 105–150 |

| K (mg/L) | n.m. | 116–224 |

| Fe (mg/L) | n.m. | <0.10 *–0.62 |

| Coliform (CFU/100 mL) | 3.1 × 103–3.9 × 104 | 1.1 × 103–1.1 × 105 |

| E. coli (CFU/100 mL) | 9.7 × 102–3.5 × 104 | 0–1.4 × 103 |

| Experiment | Crop | Growth/Yield Parameter | Hydroponic Solution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | VW | SVW | |||

| VIII | Lettuce | height (cm) | 19 ± 2 a | 16 ± 1 b | 18 ± 1 ab |

| g/plant | 180 ± 33 a | 106 ± 23 b | 160 ± 25 ab | ||

| IX | height (cm) | 20.9 ± 0.6 a | 21 ± 4 a | 20.4 ± 0.7 a | |

| g/plant | 164 ± 12 a | 144 ± 20 a | 180 ± 39 a | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luz, T.M.R.; Ushiña, D.; Santos, O.; Ispolnov, K.; Aires, L.M.I.; Sousa, H.P.D.; Bernardino, R.; Vaz, D.; Cotrim, L.; Sebastião, F.; et al. Wastewater Valorisation in Sustainable Productive Systems: Aquaculture, Urban, and Swine Farm Effluents Hydroponics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12695. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312695

Luz TMR, Ushiña D, Santos O, Ispolnov K, Aires LMI, Sousa HPD, Bernardino R, Vaz D, Cotrim L, Sebastião F, et al. Wastewater Valorisation in Sustainable Productive Systems: Aquaculture, Urban, and Swine Farm Effluents Hydroponics. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12695. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312695

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuz, Tomás M. R., Damariz Ushiña, Ounísia Santos, Kirill Ispolnov, Luis M. I. Aires, Helena Pala D. Sousa, Raul Bernardino, Daniela Vaz, Luís Cotrim, Fernando Sebastião, and et al. 2025. "Wastewater Valorisation in Sustainable Productive Systems: Aquaculture, Urban, and Swine Farm Effluents Hydroponics" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12695. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312695

APA StyleLuz, T. M. R., Ushiña, D., Santos, O., Ispolnov, K., Aires, L. M. I., Sousa, H. P. D., Bernardino, R., Vaz, D., Cotrim, L., Sebastião, F., & Vieira, J. (2025). Wastewater Valorisation in Sustainable Productive Systems: Aquaculture, Urban, and Swine Farm Effluents Hydroponics. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12695. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312695