Optimal Input Design for Fractional-Order System Identification Using an LMI-Based Frequency Error Criterion

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

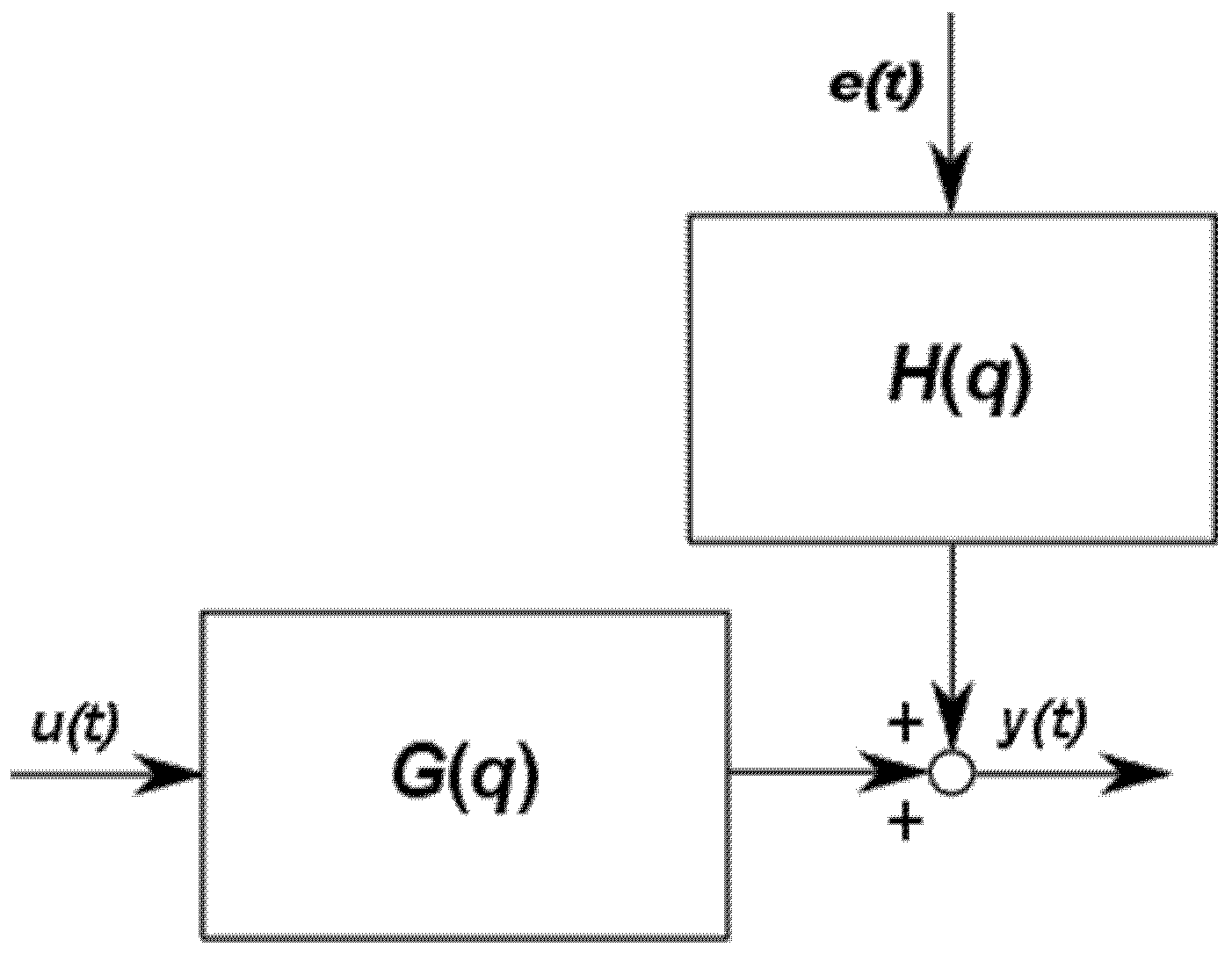

2. Problem Formulation

3. Fractional-Order System Representations

4. Optimal Input Design

4.1. System Identification

4.2. Application Cost Function

4.3. Applications-Oriented Experiment Design

5. Numerical Experiments

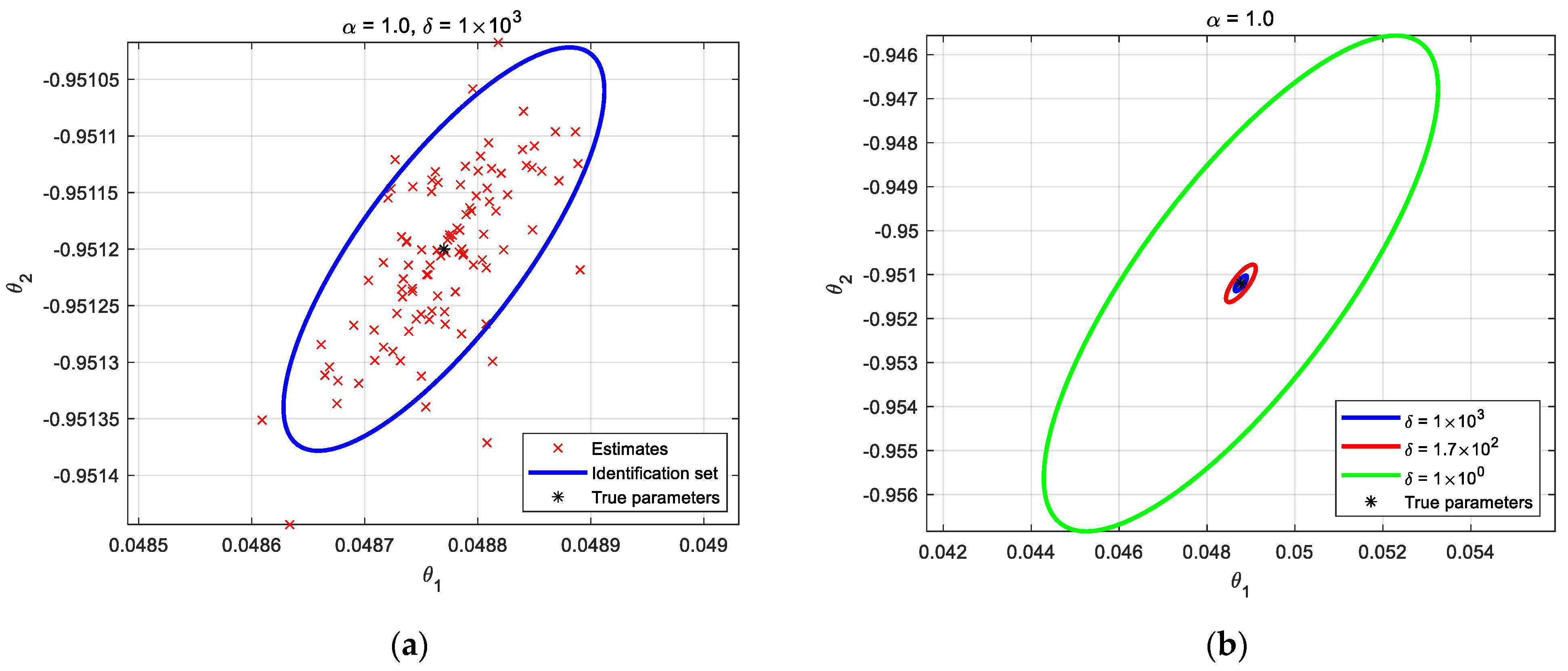

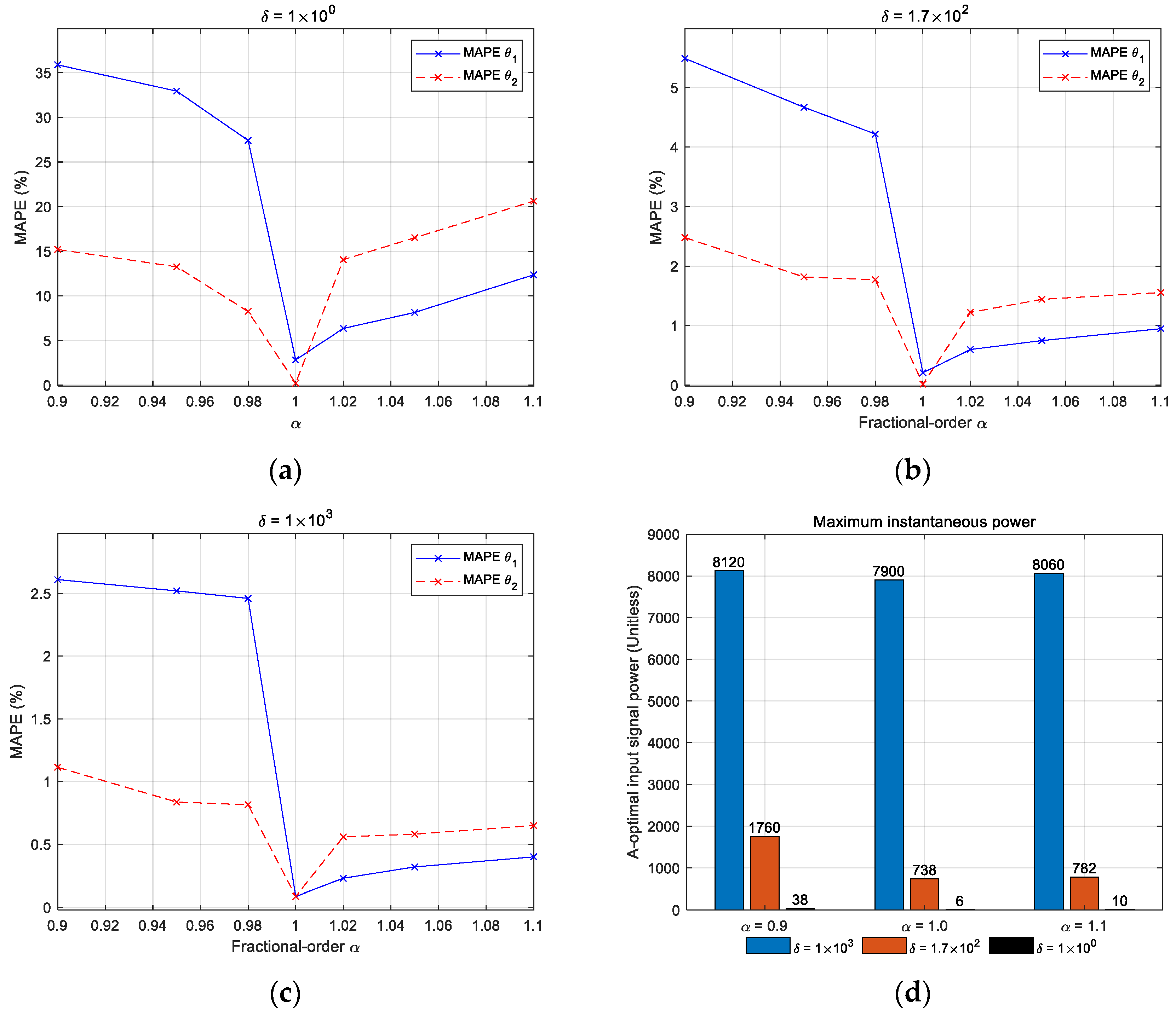

5.1. Integer-Order System Identification for α = 1.0

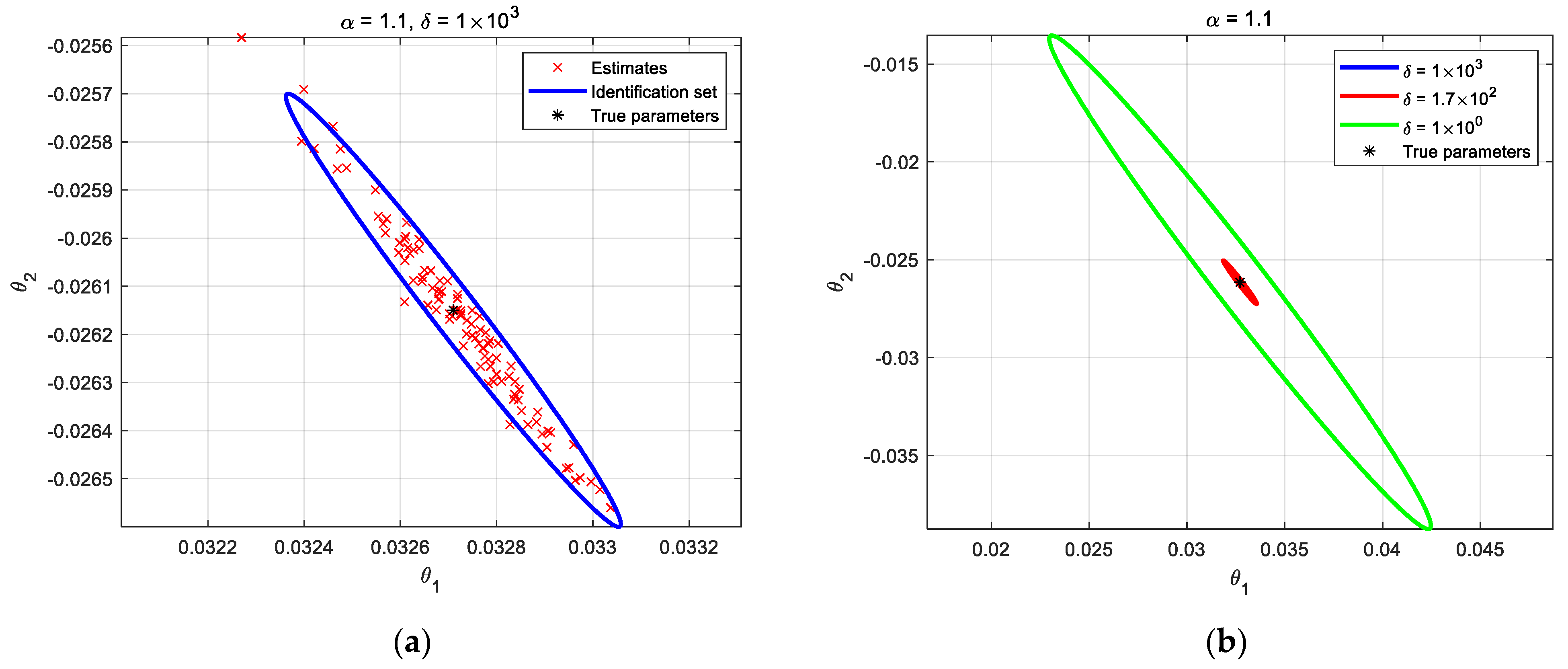

5.2. Fractional-Order System Identification for α = 0.9

5.3. Fractional-Order System Identification for α = 1.1

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalaba, R.; Spingarn, K. Control, Identification, and Input Optimization, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Peña, R.S.; Quevedo Casín, J.; Puig Cayuela, V. Identification and Control. The Gap Between Theory and Practice; Springer-Verlag: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ikonen, E.; Najim, K. Advanced Process Identification and Control; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gevers, M. Identification for Control: From the Early Achievements to the Revival of Experiment Design. Eur. J. Control 2005, 11, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombois, X.; Scorletti, G.; Gevers, M.; Van den Hof, P.M.J.; Hildebrand, R. Least costly identification experiment for control. Automatica 2006, 42, 1651–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annergren, M.; Larsson, C.A.A.; Hjalmarsson, H.; Bombois, X.; Wahlberg, B. Application-oriented input design in system identification: Optimal input design for control. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2017, 37, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Narasimhan, S. Robust plant friendly optimal input design. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Symposium on Dynamics and Control of Process Systems (IFAC), Mumbai, India, 18–20 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, S.; Rengaswamy, R. Plant friendly input design: Convex relaxation and quality. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2011, 56, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.E.; Lee, H.; Braun, M.W. ‘Plant-friendly’ system identification: A challenge for the process industries. In Proceedings of the 2003 Symposium on System Identification (IFAC), Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 27–29 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rafajłowicz, E. Optimal Input Signals for Parameter Estimation: In Linear Systems with Spatio-Temporal Dynamics; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oustaloup, A.; Levron, F.; Mathieu, B.; Nanot, F. Frequency-band complex noninteger differentiator: Characterization and synthesis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 2000, 47, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisławski, R.; Rydel, M.; Latawiec, K.J. Modeling of discrete-time fractional order state space systems using the balanced truncation method. J. Frankl. Inst. Eng. Appl. Math. 2017, 354, 3008–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakowluk, W. Optimal Input Signal Design in Control Systems Identification; Publishing House of Bialystok University of Technology: Bialystok, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Malti, R.; Mayoufi, A.; Victor, S. Experiment design for elementary fractional models. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 110, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, L. System Identification: Theory for the User; Prentice Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, S.; Mayoufi, A.; Malti, R.; Chetoui, M.; Aoun, M. System identification of MISO fractional systems: Parameter and differentiation order estimation. Automatica 2022, 141, 110268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, S.; Duhe, J.; Melchior, P.; Abdelmoumen, Y.; Roubertie, F. Long memory recursive prediction error method for identification of continuous-time fractional models. Nonlinear Dynam. 2022, 110, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Han, Q.L. Prescribed Finite-Time Consensus Tracking for Multiagent Systems With Nonholonomic Chained-Form Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2019, 64, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrashov, S.; Malti, R.; Moze, M.; Moreau, X.; Guillemard, F. Optimal input design for continuous-time system identification: Application to fractional systems. In Proceedings of the 2015 Symposium on System Identification SYSID (IFAC), Beijing, China, 19–21 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abrashov, S.; Malti, R.; Moreau, X.; Moze, M.; Aioun, F.; Guillemard, F. Optimal input design for continuous-time system identification. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2018, 60, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisławski, R. Fractional dynamical systems: Methods, algorithms and applications. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Kulczycki, P., Korbicz, J., Kacprzyk, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2022; Volume 402, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Monje, C.A.; Chen, Y.; Vinagre, B.; Xue, D.; Feliu, V. Fractional Orders Systems and Controls: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer-Verlag: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ljung, L. System Identification Toolbox: User’s Guide; The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalmarsson, H. System identification of complex and structured systems. Eur. J. Control 2009, 15, 275–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, H.; Hjalmarsson, H. Input design via LMIs admitting frequency wise model specifications in confidence regions. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 1534–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Deng, Q.; Li, Z.; Hu, W. Control-oriented closed-loop identification and input design in a wireless power transfer system. WPT 2025, 12, e007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakowluk, W.; Świercz, M. Application-oriented input spectrum design in closed-loop identification. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakowluk, W.; Jaszczak, S. Cascade tanks system identification for robust predictive control. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Technol. Sci. 2022, 70, e143646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annergren, M.; Larsson, C.A. MOOSE2: Model Based Optimal Input Signal Design Toolbox. Version 2, Sweden, 2015. Available online: https://www.kth.se/is/dcs/research/sysid/moose/moose2-toolbox-1.194509 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Löfberg, J. YALMIP: A toolbox for modeling and optimization in MATLAB. In Proceedings of the Computer Aided Control System Design Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 2–4 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Toh, K.C.; Todd, M.J.; Tütüncü, R.H. On the Implementation and Usage of SDPT3—A Matlab Software Package for Semidefinite-Quadratic-Linear Programming, Version 4.0. In Handbook of Semidefinite, Conic and Polynomial Optimization; Anjos, M.F., Lasserre, J.B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 715–754. [Google Scholar]

| δ/θ | 1 × 100 | 1.7 × 102 | 1 × 103 |

|---|---|---|---|

| θ1 | 2.842% | 0.213% | 0.086% |

| θ2 | 0.225% | 0.017% | 0.006% |

| δ/θ | 1 × 100 | 1.7 × 102 | 1 × 103 |

|---|---|---|---|

| θ1 | 35.875% | 5.485% | 2.270% |

| θ2 | 16.138% | 2.479% | 0.888% |

| δ/θ | 1 × 100 | 1.7 × 102 | 1 × 103 |

|---|---|---|---|

| θ1 | 12.366% | 0.951% | 0.401% |

| θ2 | 20.617% | 1.557% | 0.653% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jakowluk, W.; Świercz, M. Optimal Input Design for Fractional-Order System Identification Using an LMI-Based Frequency Error Criterion. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312665

Jakowluk W, Świercz M. Optimal Input Design for Fractional-Order System Identification Using an LMI-Based Frequency Error Criterion. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312665

Chicago/Turabian StyleJakowluk, Wiktor, and Mirosław Świercz. 2025. "Optimal Input Design for Fractional-Order System Identification Using an LMI-Based Frequency Error Criterion" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312665

APA StyleJakowluk, W., & Świercz, M. (2025). Optimal Input Design for Fractional-Order System Identification Using an LMI-Based Frequency Error Criterion. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312665