Emotional Revitalization of Traditional Cultural Colors: Color Customization Based on the PAD Model and Interactive Genetic Algorithm—Taking Liao and Jin Dynasty Silk as Examples

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Cultural Translation of Sentiment Models: We proposed a “Cultural Emotion Vocabulary-PAD Value Mapping” mechanism that translates core emotions within the Liao–Jin cultural context into computable PAD objectives. This formed an emotion quantification lexicon and reusable workflow tailored for cultural heritage scenarios, effectively bridging the gap between emotion computing and cultural semantics.

- Innovation in Emotion-Driven Algorithm Mechanisms: We introduced an “emotion-target-driven” IGA optimization paradigm that replaces generic preference with PAD emotional distance as the fitness function. This approach enhances interpretability and convergence efficiency, thereby reducing the interference of user fatigue and enhancing evolutionary stability.

- An empirical path from “Form–Color Restoration” to “Emotional Restoration”: Within cultural heritage digitization, this study responded to the academic trend of deepening restoration from “form–color” to “experience” and “spiritual” dimensions [13,14]. Using Liao–Jin dynasty silk as a case study, we demonstrated the effectiveness and scalability of our framework for digital regeneration, which is in step with the field’s evolving research trajectory.

2. Related Work

2.1. The Application of Intelligent Algorithms in Color Design

2.2. Study on the Color Characteristics of Cultural Relics from the Liao–Jin Dynasty

2.3. Limitations of IGA in Emotional Design

- User Fatigue: The algorithm requires users to provide sustained ratings over numerous generations. Repeated operations lead to declining evaluation consistency and introduce significant noise.

- Ambiguous Evaluation: Fitness is often measured by a vague “preference” score, lacking decomposition into specific emotional dimensions. This obscures optimization directions and hinders convergence.

- Lack of cultural context: Generic IGA fails to embed specific cultural emotional semantics, making it difficult to generate solutions embodying the cultural semantic characteristics of Liao–Jin culture, such as “Majestic,” “Dignified,” and “Passionate.”

2.4. Emotional Computing and PAD Model

2.5. Limitations of Existing Research and Innovations of This Study

- Theoretical Integration and Mechanism Innovation: Transforming the PAD model from a traditional “measurement tool” into an “emotional navigator” and fitness function within the IGA evolutionary process. This provides the algorithm with precise PAD values as optimization targets, fundamentally alleviating the issues of evaluation ambiguity and convergence difficulties in IGA, establishing a new optimization driven by cultural emotion.

- Cultural Infusion and Application: Constructing a mapping table between Liao–Jin cultural semantic vocabulary and PAD values—such as Bold representing the mighty, fearless connotations of nomadic culture; Dignified embodying the dignified symbolism of imperial authority—translates abstract cultural traits into computable parameters. This enables IGA to generate color schemes that are both personalized and culturally distinctive, achieving deep application of emotional computing in the digital regeneration of cultural heritage.

- Methodological Contribution: This study proposed an “emotion-driven” pathway for cultural heritage regeneration, transcending traditional “form-and-color replication” to achieve computational restoration and innovative expression of cultural spirit and emotional experience. This methodology offers novel perspectives for digital costume research while providing reusable empirical cases and cross-disciplinary methodological tools for the digital humanities.

3. Methods

3.1. Principles of IGA

- Initialize the PopulationGenerate an initial population based on the initial color scheme. Each individual in the population typically represents an encoded potential solution. SpecificallyAmong them: is the initial population, is an individual in the population, and n is the population size.

- EvaluationIn the Interactive Genetic Algorithm, a predefined fitness evaluation strategy is used to assess the fitness of each individual. Specifically:Among them: is the fitness of an individual .

- Population Evolution

- SelectionThe selection process is based on the fitness of individuals, with more fit individuals having a higher probability of being selected to generate the next generation. Commonly used methods include Roulette Wheel Selection or Tournament Selection. Details are as follows:Among them: P represents the population, a collection of multiple individuals. Each individual represents a potential solution, such as a color combination in a palette. The fitness function f is used to evaluate the quality of each individual.

- CrossoverSelected individuals undergo crossover operations to generate new individuals. This simulates the mating process in biological inheritance within genetic algorithms. The specific steps are as follows:Among them: and are the selected parent individuals, while and are the offspring produced through crossover.

- MutationTo increase population diversity, modify a portion of an individual’s genes with a certain probability. The specifics are as follows:Among them: y represents individuals after crossing, represents individuals after mutation. New populations are generated according to evolutionary rules.

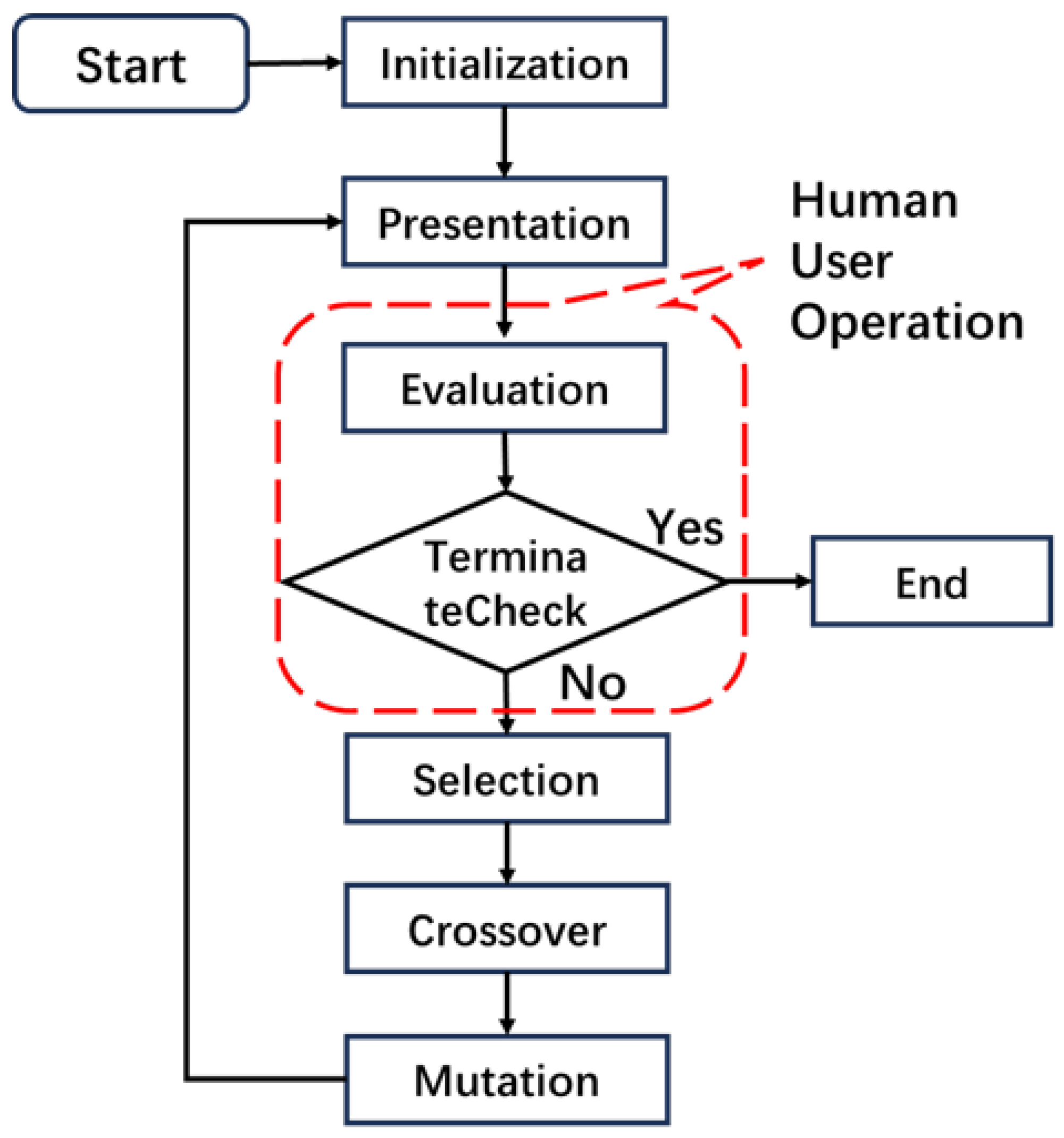

- Termination CriteriaRepeat the above steps until the termination criteria are met, such as reaching the maximum iteration count, the fitness exceeding a certain threshold, or the emergence of a satisfactory individual. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of a traditional genetic algorithm. When human users participate in evaluation, it becomes the Interactive Genetic Algorithm.

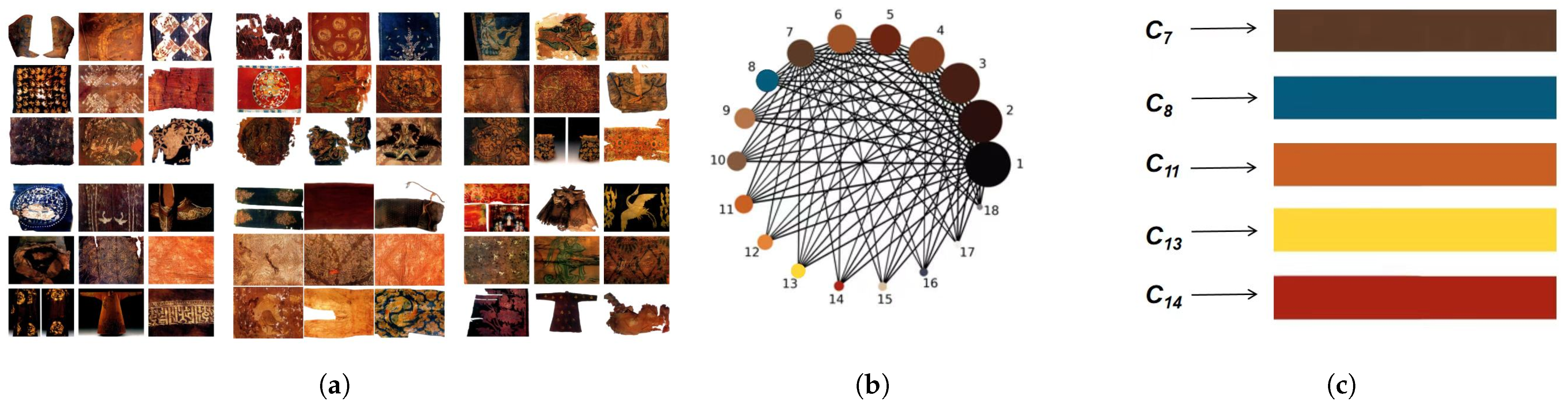

3.2. The Principle of Color Gene Customization Based on Color Networks

3.3. Improved Interactive Color Scheme Design

3.3.1. Fitness Scoring Mechanism and PAD Emotional Space Analysis

3.3.2. Interactive Color Scheme Design Based on the PAD Emotion Model (PAD-IGA)

- Initial Population Generation. Multiple color schemes are generated based on user-specified color genes and the target design object (e.g., fabric or cultural and creative products), forming the initial population for the genetic algorithm. Each individual in the population corresponds to a candidate color combination.

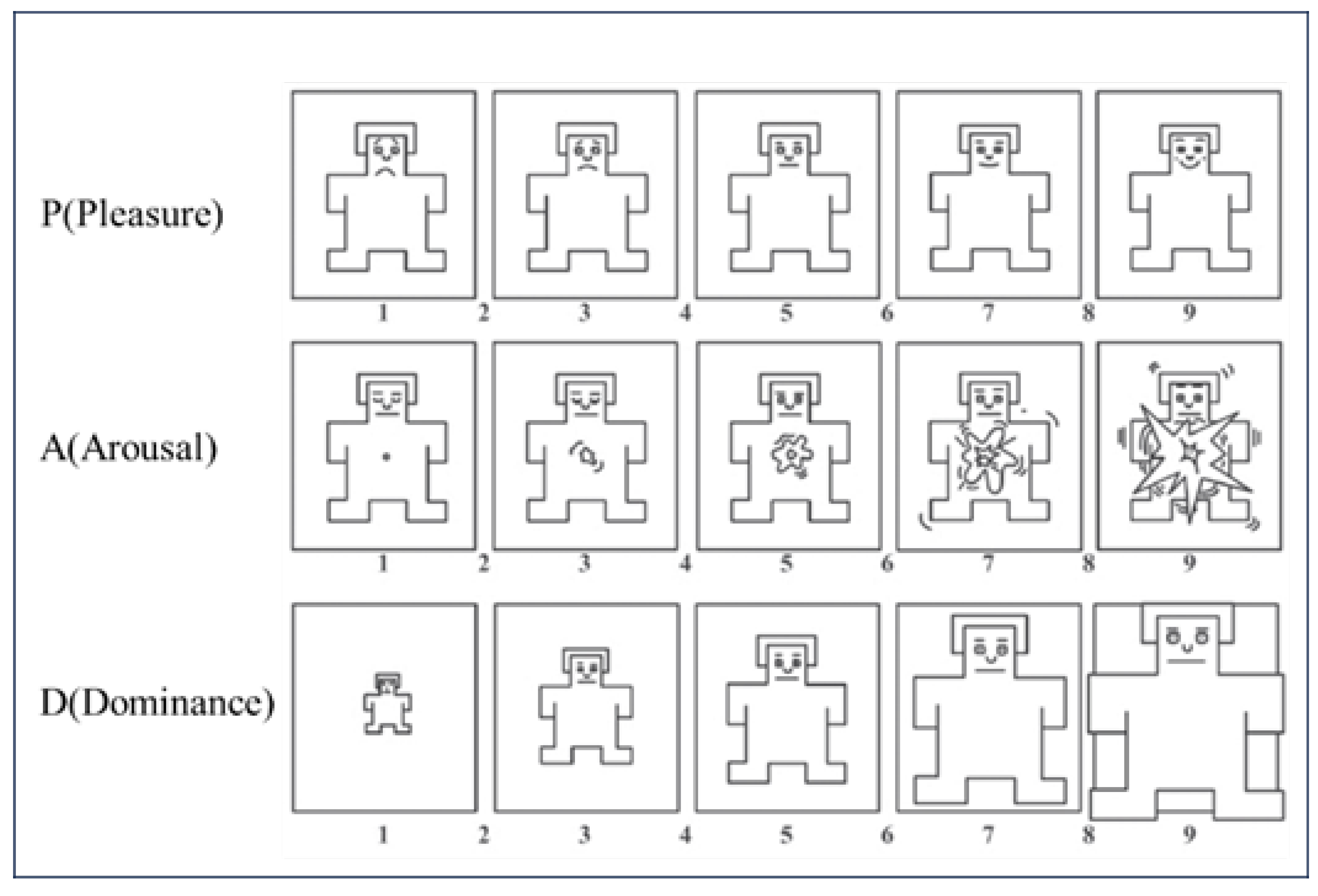

- Emotion Quantification and Fitness Calculation. For all color schemes in each generation, users are required to provide three-dimensional PAD emotion scores using the SAM scale. The fitness function is then computed as the Euclidean distance between the PAD values of the solution and the target emotional PAD vector, with closer distances corresponding to higher fitness and greater distances to lower fitness. This mechanism ensures that the evolutionary direction aligns with predefined cultural–emotional objectives.

- Evolutionary Iteration. A new generation of the population is produced through the selection, crossover, and mutation operations of the genetic algorithm. Fitness is continuously updated based on the PAD distance in each iteration, enabling the progressive optimization of the emotional alignment of the color schemes.

- Convergence and Early Termination. As evolution progresses, the population converges toward the target emotional point. The evolutionary process may be terminated early once the PAD value of a color scheme falls below a set threshold relative to the target vector, at which point the optimal solution that meets the requirements is output.

3.3.3. Parameter Description

- The population size was set to 25, referencing the conventional range (between 16 and 30) in IGA affective design. Preliminary experiments revealed that a population size of 16 resulted in insufficient diversity among generated schemes, failing to comprehensively cover cultural nuances; whereas expanding to 30 tended to induce user evaluation fatigue. After comprehensive evaluation, 25 proposals strike the optimal balance between maintaining diversity and controlling fatigue.

- Regarding genetic operation probabilities, the crossover probability is set to 50% to ensure effective recombination of high-quality color genes. The mutation probability is set to 30% to moderately introduce new traits while preventing premature algorithm convergence.

- Other key configurations include the implementation of a roulette selection strategy coupled with an elite retention mechanism. Specifically, the strategy retains only proposals with a fitness score of 7.5 or higher, thereby ensuring the effective transmission of high-quality cultural color traits.

| Algorithm 1 Color Scheme Evolutionary Algorithm. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Experiment and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Subjects and Preparations

4.2. Experimental Procedure

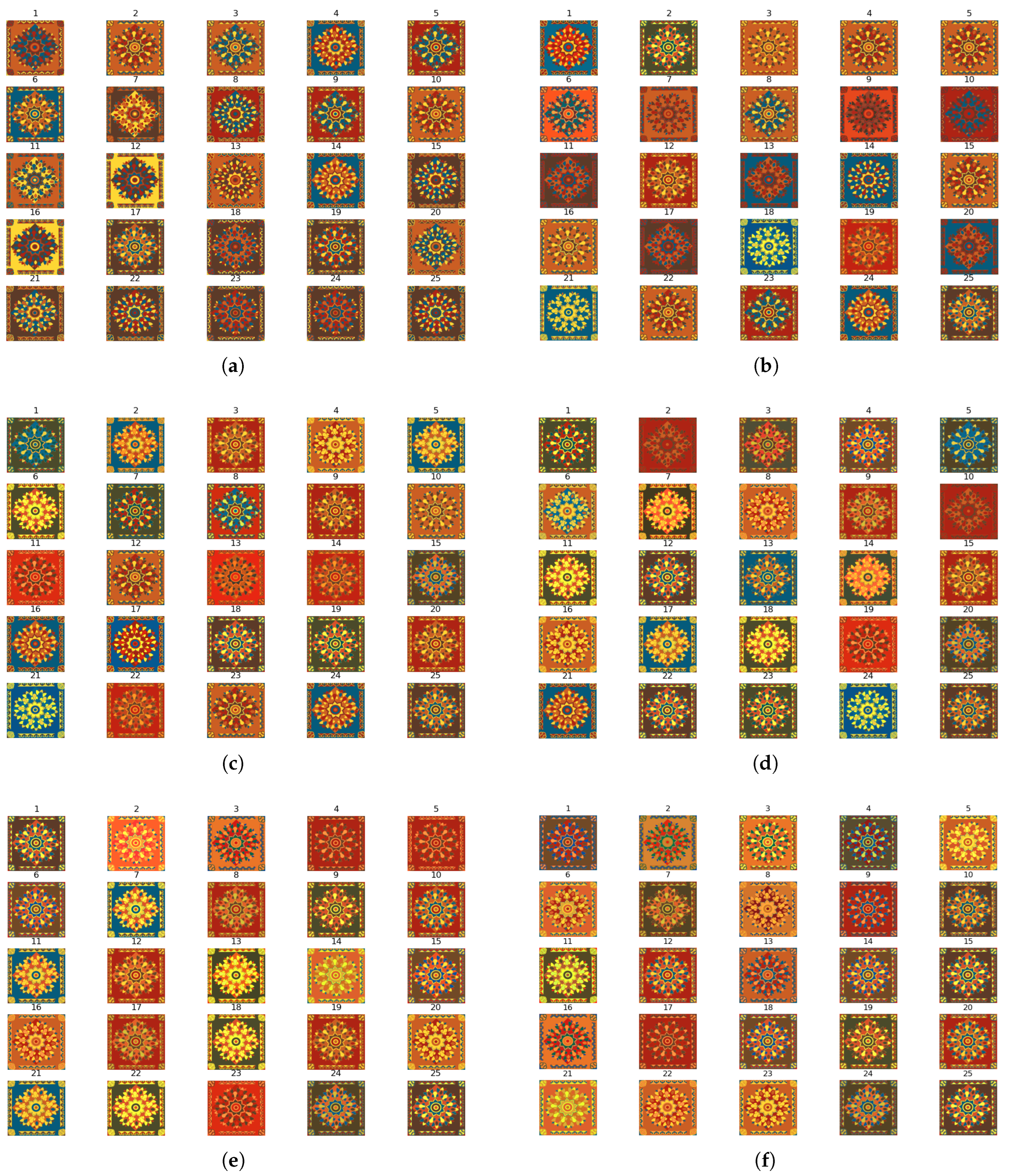

- Initial Population Generation. Users first import the Liao–Jin silk images and set the initial population size Figure 5a. Then color genes are automatically extracted by the system, and an initial population is generated to serve as the starting point for evolution. Subsequently, users select the target emotion in the emotion selection interface Figure 5b, providing emotional guidance for the subsequent evolutionary process.

- Emotional Evaluation and Fitness Calculation. Each generation of color schemes generated by the system undergoes three-dimensional PAD emotional scoring using the SAM scale Figure 5c. The system calculates the Euclidean distance between each scheme’s PAD value and the target emotional vector, using this distance as the fitness function: a smaller distance indicates higher fitness.

- Evolutionary Iteration. After user scoring, the system executes a “generation change” operation, generating a new population through selection, crossover, and mutation using genetic operators. As iterations proceed, the population gradually converges toward the target emotional point until a preset threshold is reached. During the experiments, all scoring tasks were completed by the volunteers based on their professional backgrounds and aesthetic preferences.

4.3. Results and Analysis

- Evolutionary Process. Initial color scheme applied to the designed vector artwork. At the center of the artwork is the composite flower based on the Buddhist treasure flower motif, surrounded by two core elements: lotus petal patterns and auspicious cloud patterns. As shown in Figure 6, Figure 6a depicts the initial population, while Figure 6b–f correspond to generations 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15, respectively. The color schemes progressively optimize during the intergenerational evolution.

- Example of a Satisfactory Solution. After multiple iterations, several color combinations that are highly aligned with the target emotion “Bold” were generated by the system. A representative satisfactory solution is presented in Figure 7, which conveys the “boldness and dignify” embodied in Liao–Jin silk while maintaining excellent color harmony, thereby providing intuitive evidence for the feasibility of the proposed method.

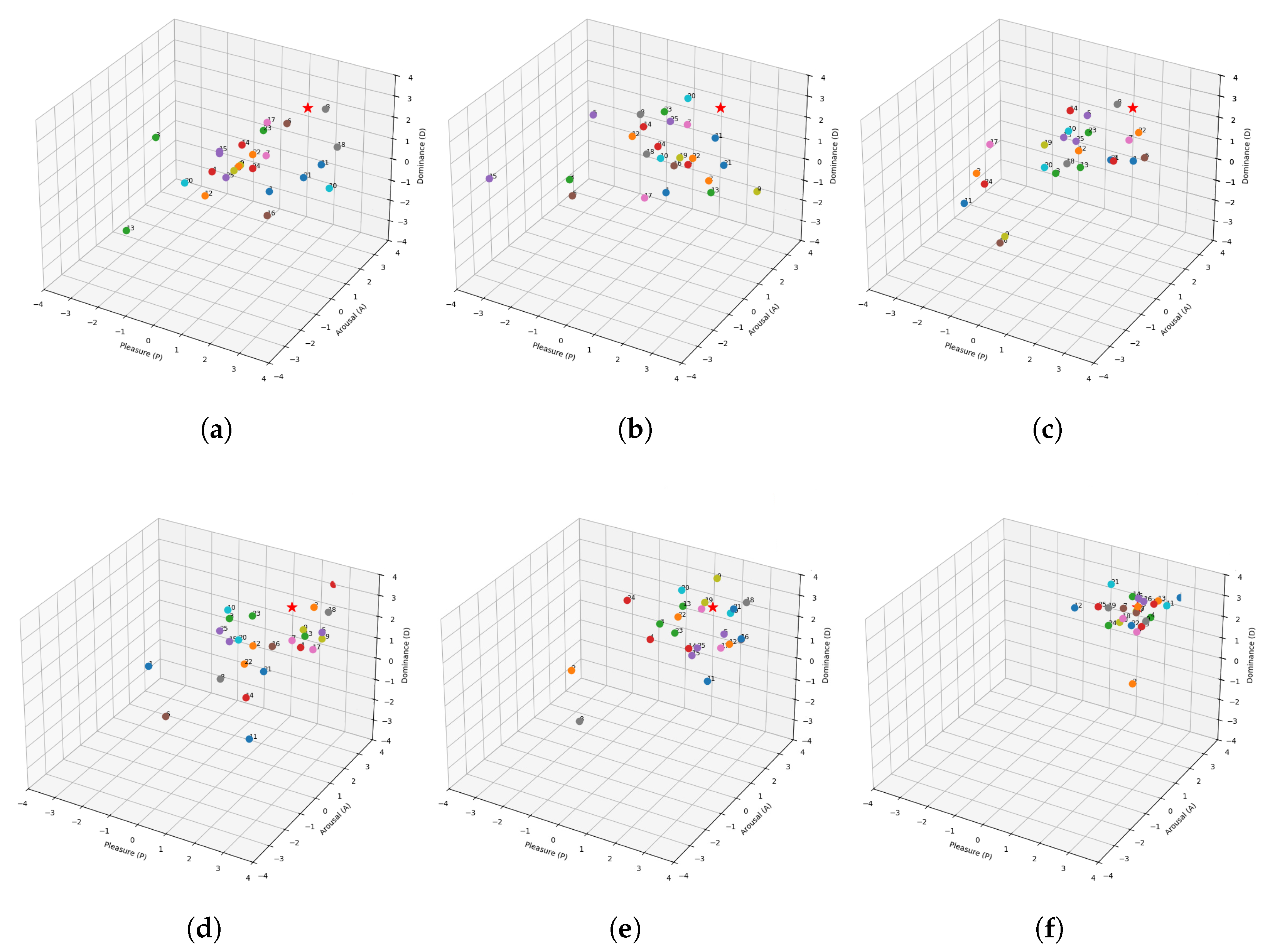

- Convergence Trend. Figure 8a–f illustrates the dynamic evolution of individual distributions within the PAD three-dimensional space. From generations to 15, the population progressively converges toward the target emotional anchor points, with different colors representing varying fitness levels. The overall trend indicates that PAD-IGA achieves stable convergence within a finite number of iterations, with a clear and consistent optimization direction that precisely reflects the population evolution trend under the PAD-IGA algorithm.

4.4. Extended Validation

4.4.1. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

4.4.2. Consumer Survey

- Emotional Authenticity: The extent to which the color scheme accurately evokes emotional resonance with specific imagery of Liao–Jin culture, such as the mighty spirit of nomadic peoples, the majestic dignity of imperial dignified, or the fervent celebrations of victory. This reflects the authenticity and impact of color design in conveying cultural emotions.

- Color Harmony: The coordination and visual balance among colors within the palette, encompassing contrast, gradation, and equilibrium, are assessed.

- Color Fidelity: The faithfulness of the color scheme in reflecting the original chromatic characteristics of Liao and Jin dynasty silks, thereby embodying their historical and artistic value, is evaluated.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAD | Pleasure–Arousal–Dominance |

| IGA | Interactive Genetic Algorithm |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interface |

| SAM | Self-Assessment Manikin |

| PAD-IGA | Interactive Color Scheme Design Based on the PAD Emotion Model |

References

- Kodžoman, D.; Cuden, A.P.; Cok, V. Emotions and fashion: How garments induce feelings to the sensory system. Ind. Textila 2023, 74, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.N.; Xu, B.Q.; Liu, X.J. Reference Image Assisted Color Matching Design Based on Interactive Genetic Algorithm. Packag. Eng. 2020, 41, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Xing, B.; Liu, X.; Tang, Z.; Shi, L. Emocolor: An assistant design method for emotional color matching based on semantics and images. Color Res. Appl. 2023, 48, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Q.; Wang, J. Wardrobe Furniture Color Design Based on Interactive Genetic Algorithm. BioResources 2024, 19, 6230–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, X. 3D Vase Design Based on Interactive Genetic Algorithm and Enhanced XGBoost Model. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gypa, I.; Jansson, M.; Wolff, K.; Bensow, R. Propeller optimization by interactive genetic algorithms and machine learning. Ship Technol. Res. 2023, 70, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, X. Improved Interactive Genetic Algorithm for Three-Dimensional Vase Modeling Design. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 6315674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Guan, M.; He, M.; Tian, Z. An interactive evolutionary design method for mobile product customization and validation of its application. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2022, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, R.; Cong, L.; Fu, Y.; Wang, B.; Shen, G.; Xu, B.; Hu, M.; Han, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L. Multi-faceted analysis reveals the characteristics of silk fabrics on a Liao Dynasty DieXie belt. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, U.S.; Micoli, L.L.; Caruso, G.; Guidi, G. Integrating quantitative and qualitative analysis to evaluate digital applications in museums. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 62, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieto, A.; Pozzato, G.L.; Striani, M.; Zoia, S.; Damiano, R. Degari 2.0: A diversity-seeking, explainable, and affective art recommender for social inclusion. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2023, 77, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, H. Reiterating the Spirit of Place: A Framework for Heritage Site in VR. Int. J. Adv. Smart Converg. 2025, 13, 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzerini, F. The spirit and the substance. The human dimension of cultural heritage from the perspective of sustainability. In Cultural Heritage, Sustainable Development and Human Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liu, Y.K.; Lo, K.C.; Kan, C. Intelligent techniques and optimization algorithms in textile colour management: A systematic review of applications and prediction accuracy. Fash. Text. 2024, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Gu, B. Color Analysis of Brocade from the 4th to 8th Centuries Driven by Image-Based Matching Network Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cen, Y.; Qu, L.; Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. Virtual Restoration of Ancient Mold-Damaged Painting Based on 3D Convolutional Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Huang, Q.; Ni, N.; Zhao, H.; Sun, B. Research on the Design of Zhuang Brocade Patterns Based on Automatic Pattern Generation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Cao, J.W.; Xu, P.H.; Lin, R.; Sun, X. Automatic color matching of clothing patterns based on image colors of Peking Opera facial makeup. J. Text. Res. 2022, 43, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F. Chinese Silk Art Through the Ages: Liao and Jin Dynasties; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Q. An Archaeological Study of Female Costumes in the Song, Liao, and Jin Dynasties. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- He, F. Clothing Culture of the Khitan and Jurchen Peoples in the Songyuan Area during the Liao and Jin Dynasties. J. Jilin Prov. Inst. Educ. 2013, 29, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Tian, X. Combining users’ cognition noise with interactive genetic algorithms and trapezoidal fuzzy numbers for product color design. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 1019749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, R.A.; Luna-García, H.; Celaya-Padilla, J.M.; García-Hernández, A.; Reveles-Gómez, L.C.; Flores-Chaires, L.A.; Delgado-Contreras, J.R.; Rondon, D.; Villalba-Condori, K.O. A systematic literature review of modalities, trends, and limitations in emotion recognition, affective computing, and sentiment analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X. Investigation on Decorative Materials for Wardrobe Surfaces with Visual and Tactile Emotional Experience. Coatings 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.-C. EMO-SPACE: A computational model for interaction between emotions and space. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA 2024), Hong Kong, China, 20–25 April 2024; Volume 3, pp. 401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-T.; Park, C.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Examination of User Emotions and Task Performance in Indoor Space Design Using Mixed-Reality. Buildings 2023, 13, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, J.S.; Wang, Y.Y. Construction and Application Design of Color Network Model of Dunhuang Traditional Murals. Packag. Eng. 2020, 41, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Y.X.; Hou, W.J.; Sheng, Q.; Jin, Y.; Liu, X. Research on traditional aromatherapy packaging design based on synesthesia experiment and color network. Packag. Eng. 2023, 44, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.B.; Jiang, C.; Wang, J.Q.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.Y. Butterfly color analysis and application based on clustering algorithm and color network. J. Text. Res. 2021, 42, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.T.; Liu, W.B.; Wang, Y.W.; Liu, F. Color analysis and application of Chaoyuan Painting costume based on network models. Adv. Text. Technol. 2024, 32, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Evidence for a three-factor theory of emotions. J. Res. Personal. 1977, 11, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Valerdi, L.M.; Ramirez-Lechuga, S.; Ibarra-Zarate, D.I. Audiovisual virtual reality for emotion induction: A dataset of physiological responses. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.-H.; Xu, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhu, H.; Yan, H. Evaluation and Decision of a Seat Color Design Scheme for a High-Speed Train Based on the Practical Color Coordinate System and Hybrid Kansei Engineering. Systems 2024, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Lu, F.; Li, Q.; Xue, Z. Digital Restoration of Ladies’ Costumes in Palace Music Painting. J. Text. Res. 2024, 6, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Emotion | Pleasure (P) | Arousal (A) | Dominance (D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mighty | 1.92 | 2.04 | 2.76 |

| Powerful | 2.16 | 1.80 | 2.92 |

| Strong | 2.32 | 1.92 | 2.48 |

| Bold | 1.76 | 2.44 | 2.64 |

| Dominant | 0.92 | 1.60 | 2.32 |

| Triumphant | 2.76 | 2.28 | 2.52 |

| Proud | 3.08 | 1.52 | 2.60 |

| Victory | 2.76 | 2.28 | 2.52 |

| Vigorous | 2.32 | 2.44 | 1.96 |

| Excited | 2.48 | 3.00 | 1.52 |

| Aroused | 0.96 | 2.28 | 0.88 |

| Passionate | 2.32 | 2.48 | 1.52 |

| Dignified | 2.12 | 0.88 | 2.44 |

| Majestic | 2.16 | 1.80 | 2.92 |

| Splendid | 3.04 | 1.92 | 1.40 |

| Free | 3.24 | 0.96 | 1.84 |

| Unconstrained | 3.12 | 1.00 | 1.64 |

| Confident | 2.80 | 1.12 | 2.44 |

| Determined | 1.88 | 1.36 | 2.64 |

| Ambitious | 1.64 | 2.52 | 2.48 |

| U | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |

| 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiao, P.; Xu, M.; Ma, D.; Liang, H.; Xu, S.; Fan, Y.; Hu, P. Emotional Revitalization of Traditional Cultural Colors: Color Customization Based on the PAD Model and Interactive Genetic Algorithm—Taking Liao and Jin Dynasty Silk as Examples. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312565

Xia Q, Wang J, Jiao P, Xu M, Ma D, Liang H, Xu S, Fan Y, Hu P. Emotional Revitalization of Traditional Cultural Colors: Color Customization Based on the PAD Model and Interactive Genetic Algorithm—Taking Liao and Jin Dynasty Silk as Examples. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312565

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Qianlong, Jiajun Wang, Pengwei Jiao, Mohan Xu, Dingpeng Ma, Haotian Liang, Sili Xu, Yanni Fan, and Pengpeng Hu. 2025. "Emotional Revitalization of Traditional Cultural Colors: Color Customization Based on the PAD Model and Interactive Genetic Algorithm—Taking Liao and Jin Dynasty Silk as Examples" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312565

APA StyleXia, Q., Wang, J., Jiao, P., Xu, M., Ma, D., Liang, H., Xu, S., Fan, Y., & Hu, P. (2025). Emotional Revitalization of Traditional Cultural Colors: Color Customization Based on the PAD Model and Interactive Genetic Algorithm—Taking Liao and Jin Dynasty Silk as Examples. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312565