1. Introduction

The external gear pumps represent one of the most extensively used positive displacement pumps in fluid power systems due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, robustness, and wide range of industrial applications. These pumps operate by meshing gear pairs that transport fluid from the suction to the discharge side without the need for valves, making them highly reliable even in harsh operating conditions [

1,

2,

3]. They find critical usage in sectors such as automotive, aerospace, agricultural machinery, construction equipment, and industrial hydraulics [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The primary reason for their popularity lies in their favourable attributes: compact design, high-pressure capabilities, self-priming operation, and tolerance to contamination. These characteristics make them particularly suitable for applications involving power steering systems, lubrication circuits, and transmission control in mobile machinery [

6,

8]. Despite their structural simplicity, external gear pumps are increasingly being subjected to performance optimization and durability enhancements to meet stringent energy efficiency, noise emission, and service life requirements.

One of the significant challenges in external gear pump design is optimizing the pump housing structural integrity, a component that must provide sufficient structural stiffness to withstand pressure fluctuations and gear-induced dynamic loads while also contributing to mass minimization. Housing size and wall thickness have a direct impact on pump mass, manufacturing cost, and overall system compactness. Therefore, designers are faced with a fundamental trade-off between mass reduction and mechanical strength, particularly in lightweight or energy-sensitive applications such as aerospace and electric vehicles [

9,

10].

The structural optimization of gear pump housings is further complicated by the non-uniform and dynamic internal pressure distribution arising from the meshing of gear teeth, pressure pulsations, and fluid leakage paths. Traditional approaches often adopt conservative design margins, which tend to result in over-dimensioned housings. However, recent studies have employed finite element analysis (FEA) in conjunction with empirical or analytical pressure models to more accurately assess stress distributions within the housing [

2,

11]. Furthermore, the integration of automated design tools, such as CAD software application programming interfaces (APIs), with FEA solver codes represents a significant advancement in parametric design optimization. These frameworks facilitate the rapid iteration of housing geometries under defined boundary conditions and performance constraints, thereby enabling efficient exploration of the design space [

12,

13,

14]. Such approaches have demonstrated potential in reducing mass while preserving structural integrity, and in aligning mechanical design processes with digital twin paradigms [

15].

Recent advancements in gear pump design and optimization have been largely influenced by innovations in computational modelling, design automation, and simulation-driven engineering [

16]. As external gear pumps continue to be essential components in fluid power systems across industries, ranging from automotive and aerospace to heavy machinery and agriculture, research has increasingly focused on improving their volumetric efficiency, reducing flow pulsation and noise, and enhancing structural robustness [

4,

5,

8]. A significant area of research has centred on the internal geometry of gear pumps, particularly the design of gear tooth profiles to improve displacement characteristics and reduce pressure pulsation. Zhao and Vacca (2017) developed a multi-objective optimization framework for external spur gear pumps, using analytical expressions for flowrate and non-uniformity, integrated into a parametric model [

4]. Their work demonstrated that asymmetric gear teeth profiles, designed through variation in pressure angle, profile shift, and addendum modification, can significantly reduce flow irregularities, which are major contributors to noise and vibration in hydraulic systems. This methodology is especially relevant in the context of high-precision applications where smooth flow delivery is critical. In addition to flow uniformity, recent studies have explored the impact of gear geometry on volumetric efficiency and internal leakage. For example, Mitov et al. (2024) conducted a combined computational fluid dynamics (CFD)–experimental validation study, analyzing transient flow behaviour in gear pumps under varying rotational speeds and pressures [

1]. Their findings highlighted the critical role of gear clearances and tooth engagement dynamics on flow pulsation and pressure recovery, indicating opportunities for further performance improvements through profile refinement. The integration of numerical methods such as CFD and FEA has enabled comprehensive performance predictions under realistic operating conditions. Zharkevich et al. (2023) [

17] proposed a parametric optimization strategy for a newly designed five-gear pump casing using FEA. The study compared structural performance under specific pressure using aluminum, cast iron, and polycarbonate materials. Stress analysis identified high-stress zones at casing grooves, and optimized designs, achieved by geometric alterations and rounding stress concentrators, led to significant mass reductions (up to 16%) without compromising safety or fatigue strength. The aluminum version showed the most favourable trade-off between mass and strength, making it the optimal material for lightweight pump designs [

17]. Cinar (2014) conducted a research study combining experimental methods with engineering simulations to develop an empirical alternative to linear approximation in defining the internal pressure zones of pump housings [

18]. The study consequently offered clearly defined guidelines and outputs for simulating structural deformation in gear pump housings [

9]. Zharkevich et al. (2024) presented a coupled CFD-FEM approach for multi-gear pumps, assessing not only the internal flow field but also the resulting stress distributions and displacement of structural components under hydraulic loading [

15]. This dual analysis confirmed that torque-induced deformations, rather than fluid pressure alone, are the dominant factor in structural fatigue and failure, thereby underscoring the importance of integrated design-validation frameworks. Similarly, Castilla et al. (2015) developed a three-dimensional CFD model of an external gear pump, accounting for dynamic meshing contact and decompression slot effects [

2]. Their simulations revealed complex flow interactions at gear tooth interfaces, which were not captured in earlier two-dimensional studies. This highlighted the necessity of high-fidelity 3D models for accurate flow prediction, especially in regions where cavitation or trapped volumes may occur. The study also reinforced the importance of incorporating pressure relief features in the housing design to mitigate peak loading during meshing transitions.

Complementing advances in simulation, the automation of CAD modelling using parametric design frameworks has become increasingly prevalent. Modern computer-aided design environments such as SOLIDWORKS offer powerful API’s that facilitate automated geometry generation and iterative design workflows [

19]. Chowdhury (2020) and Balachandar et al. (2020) demonstrated how CAD macros and “Visual Basic” language scripts can be employed to automate the creation and modification of part geometries based on predefined input parameters [

12,

13]. This capability drastically reduces design cycle time and enables rapid prototyping of multiple design variants for structural or performance optimization. In the context of gear pump housing design, such automation is particularly useful when integrated with FEA solvers, allowing automated evaluation of stress responses under different geometrical configurations. The use of design automation not only ensures consistency and repeatability in the modelling process but also supports optimization routines, such as those involving genetic algorithms or response surface methods, to identify optimal geometries under multi-objective constraints [

10]. The convergence of digital tools, parametric CAD modelling, high-fidelity CFD/FEA simulation, and design-of-experiments (DoE) based optimization, has paved the way for comprehensive, simulation-driven design of external gear pumps. Recent frameworks allow for automatic iteration of geometry, real-time performance evaluation, and multi-disciplinary optimization. Such approaches have the potential to substantially enhance traditional trial-and-error methods, paving the way for the development of lightweight, efficient, and application-specific gear pump designs [

5,

11,

20]. The state-of-the-art in gear pump design has evolved toward highly integrated digital workflows that leverage advanced geometry modelling, simulation fidelity, and design automation. These technologies collectively enable more informed design decisions, shorter development cycles, and, ultimately, higher-performance pump systems.

Despite the significant advancements in gear pump modelling and performance analysis over the last decade, a notable shortcoming persists in the holistic integration of CAD and FEA for automated structural optimization of external gear pump housings. The literature has largely focused on either fluid dynamic simulation of internal pump flows or isolated structural analyses, with few studies advancing a parametric CAD-FEA pipeline that can drive iterative, geometry-based size optimization [

1,

2,

4,

21]. While several researchers have proposed analytical or computational methods to investigate gear tooth profiles and internal flow behaviour [

4,

10,

22], these are typically decoupled from structural performance evaluations of the housing components. Moreover, pressure boundary conditions used in most FEA studies are often simplified or assumed uniform [

2], whereas real internal pressure distributions are non-uniform and transient [

9,

11]. Although Cinar et al. (2016) proposed a methodology for applying experimentally derived pressure distribution to FEA for stress analysis of a pump housing, the automation and iterative optimization of the design process based on this approach remains unexplored [

9]. Recent studies have shown the potential of integrating CAD macros and API-based automation tools with parametric modelling environments yet these have largely been applied to simpler geometries or mechanical components (e.g., pistons and brackets), without extending to pressure-bearing components such as hydraulic pump housings [

12,

13]. Furthermore, although the use of genetic algorithms for pump performance optimization has been demonstrated, these have not been combined with parametric CAD-FEA models for size optimization under structural constraints [

10]. There is also a scarcity of literature addressing optimization strategies that balance mass reduction with structural integrity and manufacturability. Most design improvements reported in gear pump literature target fluid efficiency or noise reduction [

5,

8], often neglecting structural mass and material usage, factors that are increasingly important for aerospace and mobile machinery applications.

In response to the limitations identified in the existing literature, this study proposes a systematic and automated framework for the lightweight structural design of external spur gear pump housings, an area that remains critically important and limitedly explored in automated mechanical design optimization research. The methodology integrates parametric 3D CAD modelling, experimentally informed boundary conditions, static structural FEA simulations, and size optimization routines aimed at reducing material usage while ensuring mechanical robustness in a single user interface (UI). The approach is grounded in validated pressure models and experimental data from previous investigations and doctoral research, thereby enhancing its practical applicability and industrial relevance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Confirmation for Mass Reduction Goal: Initial FEA Outputs

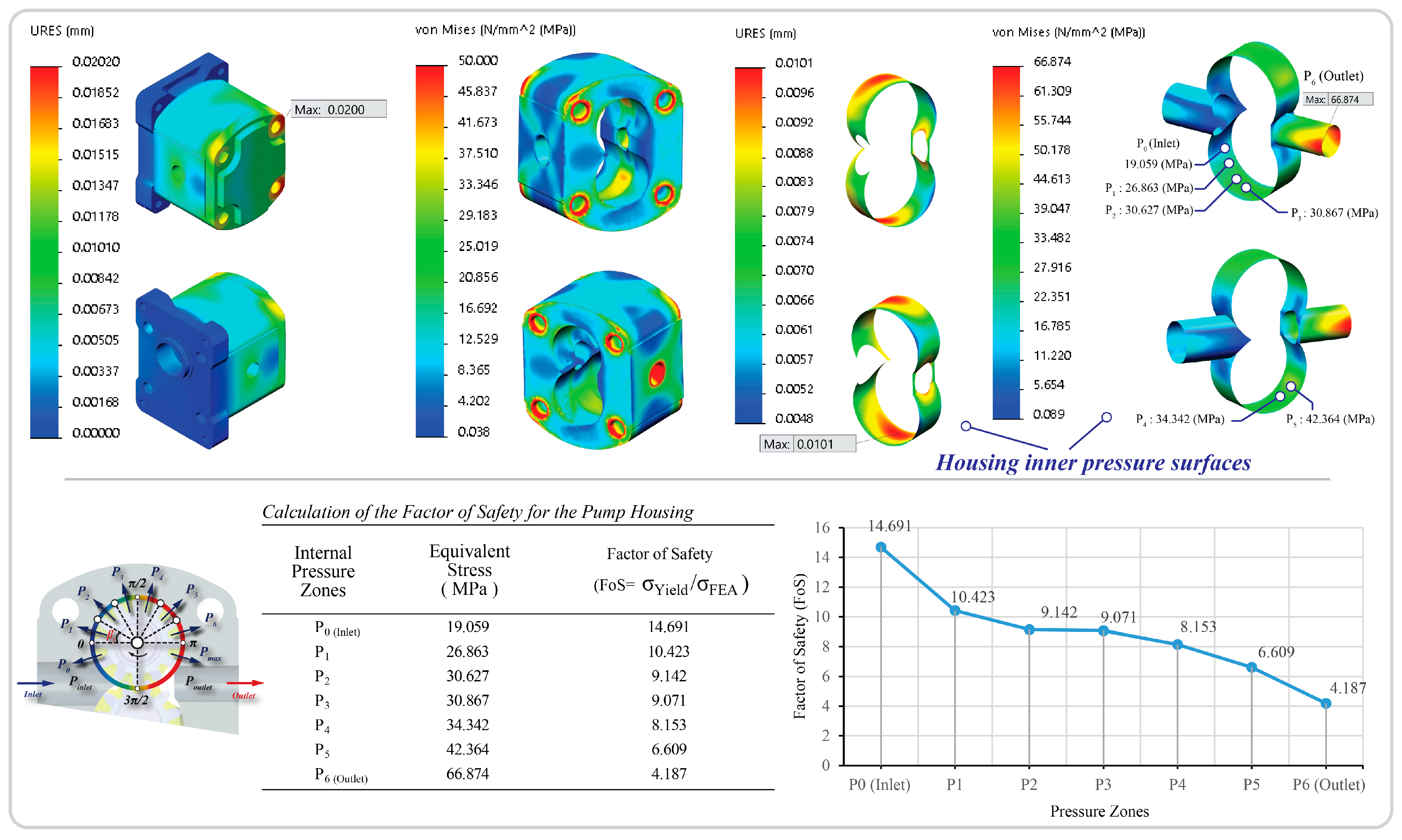

Following the completion of the pre-processing stage of the FEA workflow, a structural simulation was performed to assess the behaviour of the reference gear pump model under operating pressure loads. The primary objective was to inform subsequent structural optimization, particularly with regard to reducing housing mass while preserving mechanical integrity. The simulation assessed both global displacement responses (URES) and localized stress concentrations (via von Mises equivalent stress), spanning the outer housing structure and the internal fluid domain. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the housing exhibited low overall displacement, with a maximum deformation of 0.020 mm occurring at the front flange interface—an expected outcome given the application of mechanical boundary constraints at these regions. This low deflection behaviour at the outer body component confirms the geometric rigidity of the design and supports the retention of internal alignment tolerances essential for volumetric efficiency and long-term wear resistance in gear-driven systems. The equivalent stress distribution revealed peak stress values localized primarily around bolt holes and internal cavity transitions. However, it is critical to interpret these results within the context of the modelling approach: notably, the SOLIDWORKS Simulation “Spider Bolt” technique, which employs rigid link beam elements and preload simulation via thermal contraction, introduced artificially high stress artefacts near the bolt heads. As established in existing literature, these stress concentrations are non-physical and were therefore excluded from further interpretation to maintain analytical integrity [

31,

41,

42].

In the internal domain, the housing was subjected to a realistic fluid pressure regime ranging from 19.059 MPa at the inlet (P0) to 42.364 MPa at the outlet (P5), peaking at 66.874 MPa equivalent stress near the outlet port (P6). These stress concentrations were primarily located on the inner curved surfaces and outlet channel where the abrupt pressure transition interacts with geometric complexity. Despite these localized stress peaks, the results remain comfortably within the material’s yield strength limit of 280 MPa, with a minimum factor of safety (FoS) of 4.187 observed at the most critical point (P6). The calculated FoS values, shown in the accompanying table and trend plot, exhibit a gradual decline from inlet to outlet, corresponding with the increasing internal pressure. This gradient provides a valuable insight into the progressive load transmission through the housing and highlights potential zones for structural refinement.

Importantly, the displacement results in the internal fluid geometry were also modest, with a maximum of 0.010 mm, further confirming the stability of the structure under operational pressures. No abnormal deformation modes or signs of incipient failure sign were observed, validating the adequacy of the current geometry. Given the conservative stress distribution, particularly in regions where the FoS significantly exceeds design minimums, a clear opportunity exists for structural size optimization. Specifically, the housing wall thickness could be reduced in areas exhibiting low stress without compromising safety margins. Such a strategy would reduce the total mass of the housing, thereby improving material utilization and reducing production costs, an especially valuable improvement for mass-manufactured hydraulic components. However, the implementation of any wall thickness reduction must be executed cautiously, supported by a detailed parametric sensitivity study to ensure the retention of structural robustness, particularly in regions exposed to dynamic or fatigue-critical loading conditions. To maintain a clear methodological scope, a full sensitivity study was not undertaken; however, examining how variations in the empirical pressure distribution influence the optimization outcome (e.g., outlet-region stress gradients and selected wall-thickness values) would be particularly informative.

From a CAD and product development standpoint, it may be recommended that a parametric optimization strategy be pursued, leveraging a CAD-FEA integration loop capable of automating geometry variation and performance evaluation. Techniques such as design-of-experiments, gradient-based solvers, and topology-sensitive refinement algorithms should be employed to systematically explore and converge on an optimized wall profile. Special focus should be given to sidewall regions, flange bases, and bearing support surfaces, zones that current analysis identifies as structurally over-conservative. In these regards, the current design provides a structurally sound baseline with favourable stress and displacement characteristics under realistic pressure loading. However, the updated simulation results and factor of safety analysis reveal significant untapped optimization potential. As such, the next phase of development will adopt a CAD-FEA automated design workflow to guide the creation of a lightweight, manufacturable, and mechanically efficient gear pump housing architecture.

The integration between the empirical pressure formulation and the automated analysis loop is achieved programmatically: when the user specifies the operating pressure within the interface, the empirical equation is invoked by the backend solver module to generate the corresponding spatial pressure field. These calculated pressure values are then transmitted through the SOLIDWORKS Simulation API to update boundary conditions for each iteration. In this way, the experimentally validated model and the CAD–FEA automation operate as a deeply coupled, single workflow rather than two independent procedures. The scientific basis and experimental derivation of this model were fully detailed in our earlier publication [

9].

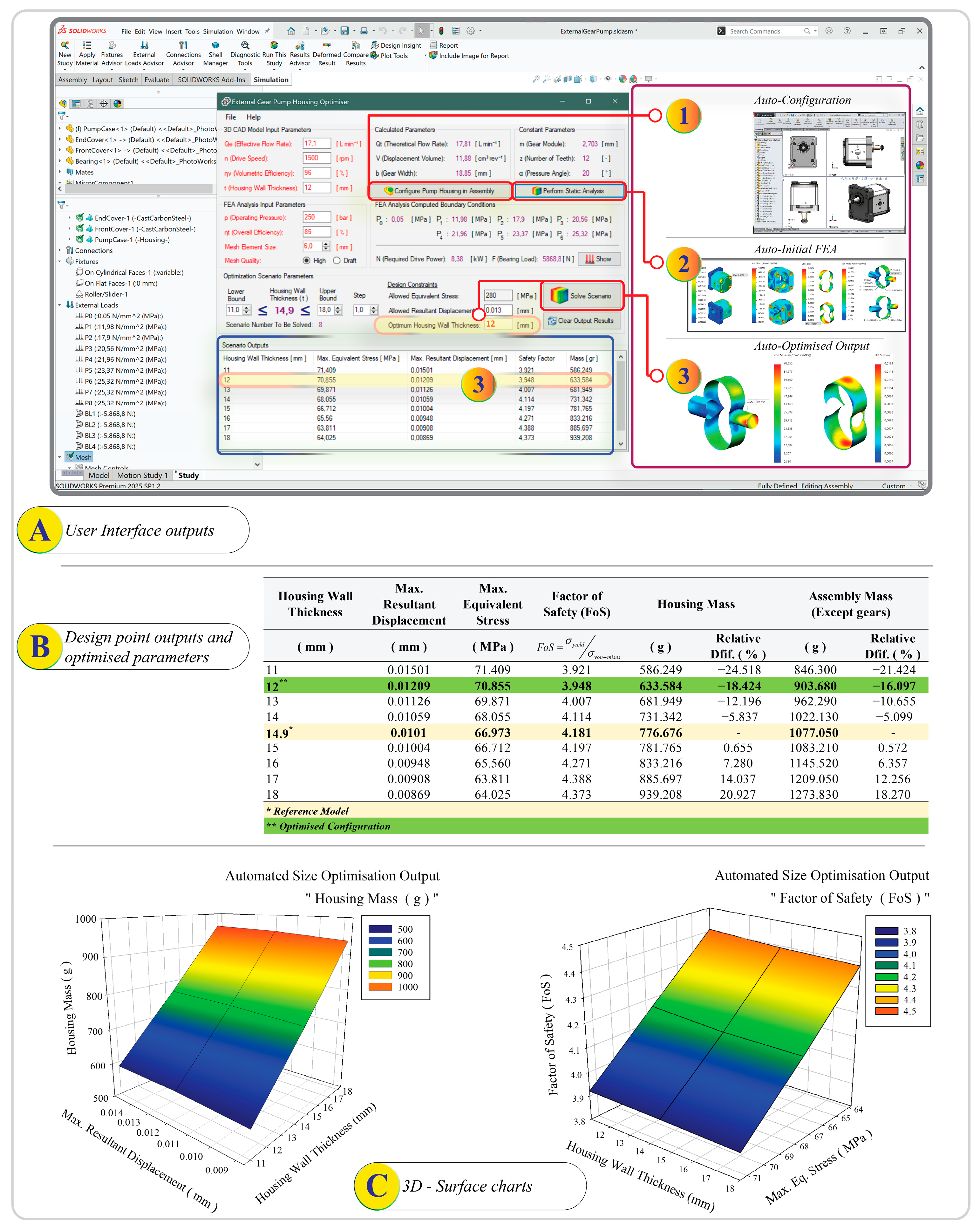

3.2. Interpretation of Application User Interface

The developed desktop application represents a pivotal advancement in automating the design optimization process for external gear pump housings. Its design demonstrates adherence to user experience and software engineering principles, with a clear separation of functionality across discrete UI panels that correspond logically to user tasks—namely, geometric input, boundary condition specification, FEA execution, and design optimization. This modularity significantly enhances usability, particularly for design engineers and researchers without specialist knowledge of CAD scripting or FEA solvers. From a user-friendly standpoint, the interface facilitates intuitive data entry through parameter-specific input fields and command buttons. The interface hierarchy mirrors the sequential nature of the design workflow, thereby reducing the cognitive load associated with navigating between operations. By providing real-time visual and numerical feedback on entered parameters and resulting outputs, the UI improves transparency and reinforces user confidence in simulation fidelity. This is consistent with established heuristics in user-centred interface design [

43], particularly the principles of feedback and visibility of system status. Technically, the interface capitalizes on the SOLIDWORKS API ecosystem to bridge parametric geometry manipulation and FEA setup, a non-trivial integration given the complex nature of boundary condition assignment and mesh control. The use of Visual Studio (Microsoft Visual Studio Community 2022) and .NET Framework v4.8 ensures platform stability, while the integration of SOLIDWORKS Interop libraries allows programmatic access to geometric features and simulation entities. This streamlines iterative design exploration and enables deterministic, reproducible simulation cycles. Notably, the system architecture adopts a closed-loop Optimization workflow where updated geometric variables, primarily wall thickness, are automatically re-evaluated under defined constraints. This approach aligns with modern practices in simulation-driven design [

17,

44], wherein the CAD-FEA pipeline is rendered executable through scripting and procedural automation. From a software engineering perspective, the deterministic iteration strategy employed in the wall thickness Optimization routine enhances solution convergence and eliminates the subjectivity inherent in manual model adjustments. Moreover, by exposing functional relationships such as flow rate versus housing depth via parametric control, the UI reflects sound object-oriented design. The inclusion of fail-safe mechanisms, such as boundary checks for stress and displacement constraints, ensures that only structurally valid solutions are considered for final selection, adhering to robustness principles in design optimization.

3.3. Case Study Outputs

Using the custom CAD-FEA optimization environment, a series of design iterations was executed to evaluate pump housing performance across a range of wall thickness values from 11 mm to 18 mm (in 1 mm increments). This automated, CAD-integrated workflow proved highly effective in performing a rapid multi-objective exploration of the design space, simultaneously assessing structural criteria and mass for each variant.

Figure 9 provides a detailed view of the optimization interface and outputs, including the scenario setup and results. Steps 1–3 shown in

Figure 9 correspond, respectively, to (1) the CAD model parameter definition and import stage, (2) the automatic FEA setup and boundary condition assignment executed by the API, and (3) the optimization and result visualization phase within the integrated interface.

Comparable optimization studies in the field, such as Zharkevich et al. (2023), who reported mass reductions up to 16% through geometric alteration and stress concentrator rounding, corroborate the efficacy of simulation-driven size reduction strategies [

17]. However, the current work distinguishes itself through its integration of experimentally validated pressure models, parametric automation, and iterative constraint evaluation within a unified desktop interface. This represents a more holistic and scalable methodology compared to previous studies that often relied on fixed-pressure assumptions and manual geometry updates [

1,

2].

Similarly, Ghionea (2013) demonstrated the effectiveness of CAD-integrated FEA tools in enabling rapid, iterative optimization of mechanical components [

45]. The current system distinguishes itself by offering a fully automated optimization workflow within the design environment, a feature particularly beneficial in digital twin development and mass customization strategies.

Key advantages of this method include the integration of automated routines, support for visual trade-off analysis via surface charts, and the ability to reduce component mass without compromising structural safety. These outcomes contribute to eco-design and lightweighting efforts, aligning with sustainability objectives. Furthermore, the customizable interface facilitates quick scenario switching and parameter adjustments, enhancing usability during iterative development cycles. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The current simulations assume static loading conditions, which may not accurately reflect the dynamic or transient operational stresses encountered in actual pump service. Material behaviour is modelled as linear elastic, omitting potential effects of fatigue or creep. Although dynamic loading and material fatigue effects were not explicitly simulated, their potential influence on local stress peaks and long-term structural integrity is acknowledged. Consequently, under cyclic and thermally varying operational conditions, actual stress and strain responses may differ from the present static predictions due to transient load redistribution and progressive material softening, which are recognized as inherent limitations of the current model. Additionally, manufacturing constraints, such as casting feasibility for thinner walls, are not directly integrated into the optimization loop. The use of parametric sweeping, while straightforward, may not achieve globally optimal solutions as effectively as multi-objective evolutionary algorithms like NSGA-II [

46].

To enhance the framework’s applicability, future work could incorporate dynamic FEA simulations, topological optimization strategies, and AI-driven surrogate models to accelerate performance predictions. Integrating cost and manufacturability assessments would further extend the system toward a comprehensive design for manufacturing (DfM) solution.

3.4. Overall Discussion

The study successfully demonstrates an integrated and automated methodology for the structural design optimization of external spur gear pump housings. By combining empirical pressure modelling, parametric CAD geometry, static structural FEA, and an intuitive desktop application interface, it offers a cohesive framework that addresses several longstanding challenges in mechanical component design, namely, the trade-off between mass reduction and structural reliability. Technically, the research advances the field by enabling realistic pressure distribution modelling within the housing, surpassing traditional simplifications such as uniform or linearly distributed loads. The adoption of an empirically derived pressure function, validated through prior experimental work, introduces a higher degree of physical fidelity into the simulation process, thereby enhancing the relevance of the FEA results. This represents a notable contribution, as earlier works [

2,

11] either employed overly simplified boundary conditions or failed to integrate such empirical insights into automated workflows.

The study’s novelty is further exemplified by the seamless integration of CAD and FEA through SOLIDWORKS API scripting, which enables dynamic model regeneration and real-time simulation. This stands in contrast to prior literature, where CAD-FEA interoperability remains largely manual or is restricted to static geometry evaluations [

13]. Moreover, the deterministic optimization routine employed here avoids the stochastic nature of genetic algorithms, offering faster convergence and improved traceability of design decisions. The UI developed as part of this study further enhances the practicality and accessibility of the automated design process. By providing a user-friendly environment for inputting design parameters and visualizing simulation results, the system lowers the barrier to adoption for engineers and designers. This is particularly relevant in industries where rapid customization and prototyping are essential [

47,

48,

49].

From a theoretical standpoint, the framework contributes to design methodology by formalizing a parametric optimization problem for gear pump housings, incorporating constraint handling and objective function formulation. It also provides a realistic and quantifiable pathway to lightweight design—a critical requirement in sectors such as aerospace, automotive, and mobile hydraulics. These results align with contemporary literature, which increasingly prioritizes multi-objective optimization for both fluid performance and mechanical resilience [

4,

10,

21]. While this approach offers numerous advantages, certain limitations must be acknowledged. These include potentially high computational demands when a large number of FEA simulations are required, a strong reliance on the accuracy of input data to ensure reliable outcomes, and the inherent opacity of the optimization algorithm, which may be perceived by users as a ‘black box’. Although a formal timing and scaling analysis was outside the present scope, identifying principal efficiency constraints (e.g., sequential FEA execution and re-meshing overhead) and benchmarking iteration cost would be beneficial for strengthening the platform’s performance characterization. In addition, the structural simulation within the application is currently restricted to static conditions and assumes a linear elastic material model. In reality, gear pumps are subjected to dynamic loading, cyclic fatigue, and thermal gradients. These factors warrant future extension of the simulation environment to include dynamic FEA or coupled multiphysics analysis. Another limitation is that, while the use of deterministic stepwise optimization provides robustness, it may fail to identify global optima in complex design spaces, a shortcoming that could potentially be addressed through hybrid methods combining deterministic and metaheuristic techniques. Furthermore, the current study does not explicitly address manufacturability constraints such as casting tolerances or machining allowances, which may affect the real-world viability of the optimized geometries. Incorporating manufacturing cost models into the objective function could further enhance the tool’s industrial applicability. Future comparative studies incorporating metaheuristic algorithms such as genetic or particle-swarm optimization may be undertaken to evaluate the computational efficiency and solution quality relative to the present deterministic framework.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive and automated design framework for the structural optimization of external spur gear pump housings, integrating parametric CAD modelling with FEA via SOLIDWORKS API and a custom-developed desktop application. The core objective was to minimize housing mass while maintaining mechanical integrity under realistic operational pressures in the presented case study. Unlike traditional approaches, which often rely on static geometry and idealized loading assumptions, this research embeds an empirically derived pressure distribution model into the automated simulation loop, thus achieving a higher degree of physical fidelity. The developed platform enables rapid parametric model generation, automated assignment of realistic boundary conditions, and iterative size optimization based on predefined stress and displacement constraints. A case study conducted on a reverse-engineered reference pump demonstrated the system’s efficacy, yielding a wall thickness configuration that achieved an 18.42% reduction in housing mass without compromising safety factors (3.948) or inducing excessive deformation (0.012 mm). The automation of the CAD-FEA workflow significantly enhances design repeatability, reduces user intervention, and streamlines the optimization process, making it particularly suitable for industrial applications requiring rapid customization and prototyping.

Key contributions of this research include (i) the integration of empirical pressure modelling with FEA for more accurate representation of internal loads; (ii) the development of a fully automated design optimization interface enabling deterministic convergence on optimal configurations; and (iii) the validation of the approach through a practical case study, showing notable improvements in structural efficiency and material utilization.

Despite its promising outcomes, the current framework is limited to static structural conditions and assumes linear elastic material behaviour. Furthermore, although a user-friendly interface has been developed to simplify complex design processes, several limitations remain. These include potentially high computational costs arising from the large number of FEA required due to the broad range of design variables, reliance on the accuracy of input data to ensure reliable results, and the opaque nature of the optimization algorithm, which may appear as a “black box” to users. Future developments may therefore focus on enhancing the UI, incorporating dynamic and fatigue loading conditions, integrating manufacturing constraints, and employing advanced optimization strategies such as topology optimization or AI-driven surrogate modelling. These improvements would contribute to increased design robustness and industrial applicability. Here, the proposed methodology represents a significant advancement in the automated design and optimization of hydraulic components, offering a scalable and efficient solution to the complex trade-offs between mass, structural integrity, and manufacturability in gear pump housing design.