Improving Sustainability in Buffalo Finishing: Olive Cake Supplementation and Its Effects on Performance and Meat Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Animals and Diets

2.3. Animal Performance and Carcass Traits

2.4. Meat Samples and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

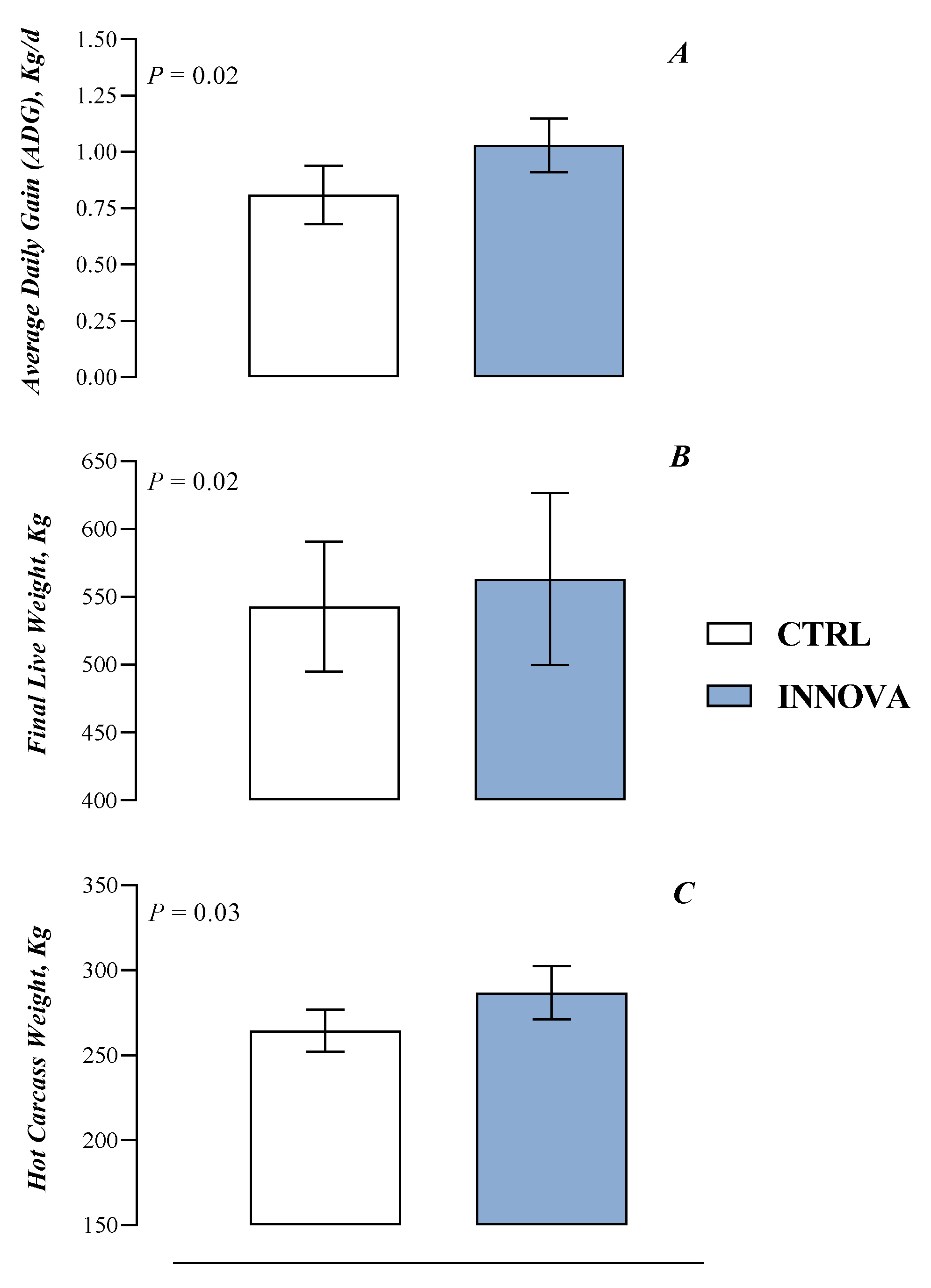

3.1. Animal Performance and Carcass Characteristics

3.2. Meat Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiofalo, B.; Di Rosa, A.R.; Lo Presti, V.; Chiofalo, V.; Liotta, L. Effect of Supplementation of Herd Diet with Olive Cake on the Composition Profile of Milk and on the Composition, Quality and Sensory Profile of Cheeses Made Therefrom. Animals 2020, 10, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litrenta, F.; Cincotta, F.; Russo, N.; Cavallo, C.; Caggia, C.; Amato, A.; Lopreiato, V.; Merlino, M.; Verzera, A.; Randazzo, C.L.; et al. Feeding Cows with Olive Cake Enriched in Polyphenols Improves the Sustainability and Enhances the Nutritional and Organoleptic Features of Fresh Caciocavallo Cheese. Foods 2024, 13, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva-Martins, F.; Correia, R.; Félix, S.; Ferreira, P.; Gordon, M.H. Effects of Enrichment of Refined Olive Oil with Phenolic Compounds from Olive Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4139–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiofalo, V.; Liotta, L.; Presti, V.L.; Gresta, F.; Di Rosa, A.R.; Chiofalo, B. Effect of Dietary Olive Cake Supplementation on Performance, Carcass Characteristics, and Meat Quality of Beef Cattle. Animals 2020, 10, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, G.; Pauselli, M.; Servili, M.; Mourvaki, E.; Serra, A.; Monahan, F.J.; Lanza, M.; Priolo, A.; Zinnai, A.; Mele, M. Dietary Olive Cake Reduces the Oxidation of Lipids, Including Cholesterol, in Lamb Meat Enriched in Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, V.; Nudda, A.; Cannas, A.; Lanza, M.; Priolo, A. Alternative Feed Resources and Their Effects on the Quality of Meat and Milk from Small Ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 147, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, M.; Serra, A.; Pauselli, M.; Luciano, G.; Lanza, M.; Pennisi, P.; Conte, G.; Taticchi, A.; Esposto, S.; Morbidini, L. The Use of Stoned Olive Cake and Rolled Linseed in the Diet of Intensively Reared Lambs: Effect on the Intramuscular Fatty-Acid Composition. animal 2014, 8, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudda, A.; Battacone, G.; Boaventura Neto, O.; Cannas, A.; Francesconi, A.H.D.; Atzori, A.S.; Pulina, G. Feeding Strategies to Design the Fatty Acid Profile of Sheep Milk and Cheese. Rev. Bras. Zootenia. 2014, 43, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiofalo, B.; Liotta, L.; Zumbo, A.; Chiofalo, V. Administration of Olive Cake for Ewe Feeding: Effect on Milk Yield and Composition. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 55, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadabadi, T.; Amindavar, S.; Joyande, H.; Jolazade, A. Effect of Olive Pomace on Digestibility, Blood Biochemical Parameters and Milk Production and Composition of Dairy Buffalo. Anim. Sci. Res. 2023, 33, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopreiato, V.; Ferronato, G.; Amato, A.; Cavallo, C.; Trevisi, E.; Llobat, L.; Chiofalo, V.; Liotta, L. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Olive Cake Enriched in Polyphenols on Growth, Rumen Fermentation, and Metabolic Status of Finishing Limousine Bulls. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Liotta, L.; Cavallo, C.; Randazzo, C.L.; Pino, A.; Bonacci, S.; Frisina, M.; Procopio, A.; Litrenta, F.; Floridia, V.; et al. Effects of Feeding Enriched-Olive Cake on Milk Quality, Metabolic Response, and Rumen Fermentation and Microbial Composition in Mid-Lactating Holstein Cows. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 1069–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, G.; Bionda, A.; Litrenta, F.; Lopreiato, V.; Di Bella, G.; Potortì, A.G.; Lo Turco, V.; Liotta, L. Using Olive Cake as a Sustainable Ingredient in Diets of Lactating Dairy Cows: Effects on Nutritional Characteristics of Cheese. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bionda, A.; Lopreiato, V.; Crepaldi, P.; Chiofalo, V.; Fazio, E.; Oteri, M.; Amato, A.; Liotta, L. Diet Supplemented with Olive Cake as a Model of Circular Economy: Metabolic and Endocrine Responses of Beef Cattle. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1077363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMEA (European Medicines Agency). VICH GL9: Good Clinical Practice; EMEA: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes; EU: Belgium, Brussels, 2010.

- Council of The European Union Council. Regulation No 1099/2009 of the European Council of 24 September 2009 on the Protection of Animals at the Time of Killing. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 303, 30. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Association of Official Analytical Chemistry International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H.S. A SIMPLE METHOD FOR THE ISOLATION AND PURIFICATION OF TOTAL LIPIDES FROM ANIMAL TISSUES. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, W.W. A Simple Procedure for Rapid Transmethylation of Glycerolipids and Cholesteryl Esters. J. Lipid Res. 1982, 23, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary Heart Disease: Seven Dietary Factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Silva, J.; Bessa, R.J.B.; Santos-Silva, F. Effect of Genotype, Feeding System and Slaughter Weight on the Quality of Light Lambs: II. Fatty Acid Composition of Meat. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2002, 77, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). In FAOSTAT Statistical Database; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, G.; Guarini, P.; Ferrari, P.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Schiavone, B.; Giordano, A. Beneficial Impact on Cardiovascular Risk Profile of Water Buffalo Meat Consumption. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuni, G.F.; Contò, M.; Amici, A.; Failla, S. Physical and Nutritional Properties of Buffalo Meat Finished on Hay or Maize Silage-based Diets. Anim. Sci. J. 2014, 85, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida-Mendoza, M.; De Moreno, L.A.; Huerta-Leidenz, N.; Uzcátegui-Bracho, S.; Valero-Leal, K.; Romero, S.; Rodas-González, A. Cholesterol and Fatty Acid Composition of Longissimus Thoracis from Water Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis) and Brahman-Influenced Cattle Raised under Savannah Conditions. Meat Sci. 2015, 106, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutos, P.; Hervás, G.; Giráldez, F.J.; Mantecón, A.R. Review. Tannins and Ruminant Nutrition. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2004, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caria, P.; Chies, L.; Cifuni, G.F.; Scerra, M.; Foti, F.; Cilione, C.; Fortugno, P.; Boninsegna, M.A.; Giacondino, C.; Claps, S.; et al. The Effects of Olive Cake and Linseed Dietary Supplementation on the Performance, Carcass Traits, and Oxidative Stability of Beef from Young Podolian Bulls. Animals 2025, 15, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioč, B.; Pavić, V.; Vnučec, I.; Prpić, Z.; Kostelić, A.; Sušić, V. Effect of Olive Cake on Daily Gain, Carcass Characteristics and Chemical Composition of Lamb Meat. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 52, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M. Protein Carbonyls in Meat Systems: A Review. Meat Sci. 2011, 89, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The Role of Polyphenols in Human Health and Food Systems: A Mini-Review. Front. Nutition 2018, 5, 370438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, V.; Daghio, M.; Cappucci, A.; Buccioni, A.; Serra, A.; Viti, C.; Mele, M. Invited Review: Plant Polyphenols and Rumen Microbiota Responsible for Fatty Acid Biohydrogenation, Fiber Digestion, and Methane Emission: Experimental Evidence and Methodological Approaches. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3781–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; King, I.B. Very Long-Chain Saturated Fatty Acids and Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2022, 33, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Alcaide, E.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. Potential Use of Olive By-Products in Ruminant Feeding: A Review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 147, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terramoccia, S.; Bartocci, S.; Taticchi, A.; Di Giovanni, S.; Pauselli, M.; Mourvaki, E.; Urbani, S.; Servili, M. Use of Dried Stoned Olive Pomace in the Feeding of Lactating Buffaloes: Effect on the Quantity and Quality of the Milk Produced. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.S.; Tyagi, A.; Hossain, S.A.; Tyagi, A.K. Effect of Tanniniferous Terminalia chebula Extract on Rumen Biohydrogenation, ∆9-Desaturase Activity, CLA Content and Fatty Acid Composition in Longissimus dorsi Muscle of Kids. Meat Sci. 2012, 90, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taticchi, A.; Bartocci, S.; Servili, M.; Giovanni, S.D.; Pauselli, M.; Mourvaki, E.; Zilio, D.M.; Terramoccia, S. Effect on Quanti-Quality Milk and Mozzarella Cheese Characteristics with Further Increasing the Level of Dried Stoned Olive Pomace in Diet for Lactating Buffalo. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients, % of DM | Ctrl | Innova |

| Corn | 58 | 40 |

| Flaked corn | - | 10 |

| Barley grain | - | 15 |

| Wheat bran | 10 | 4 |

| Alfalfa flour | 8 | - |

| Soybean meal | 8 | 11.5 |

| Olive cake | - | 7 |

| Sugar beet pulp | 5 | 2 |

| Sunflower meal | 4 | 3 |

| Minerals supplementation | 2.2 | - |

| Carob meal | - | 2 |

| Molasses-based additive | 1.5 | - |

| Calcium salts | - | 1.4 |

| Calcium carbonate | - | 0.9 |

| Calcium | 0.85 | - |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Lithothamnium calcareum | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Magnesium oxide | 0.4 | 0.25 |

| Urea | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Sodium chloride | 0.3 | 0.55 |

| Mineral–vitamin premix | 0.3 | 0.70 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 0.2 | 0.35 |

| Chemical composition, % of DM | ||

| Dry matter | 88.65 | 89.12 |

| Crude protein | 15.91 | 15.27 |

| Ether extract | 4.24 | 5.26 |

| Crude fiber | 5.49 | 6.84 |

| Neutral Detergent Fiber | 13.89 | 19.08 |

| Acid Detergent Fiber | 7.59 | 10.14 |

| Acid Detergent Lignin | 2.44 | 2.53 |

| Starch | 49.50 | 44.19 |

| Ash | 6.51 | 7.83 |

| Total polyphenols (mg GAE/g) | 1.09 | 1.25 |

| NE, MJ/kg SS 2 | 9.81 | 9.43 |

| Fatty acid profile, % of total FAME | ||

| C14:0 | 0.11 | 0.15 |

| C16:0 | 15.50 | 16.50 |

| C18:0 | 2.71 | 2.70 |

| C18:1n-9 | 31.63 | 39.95 |

| C18:2n-6 | 47.54 | 37.80 |

| C18:3n-6 | 1.50 | 1.96 |

| Fatty acid classes | ||

| SFAs | 18.96 | 19.97 |

| MUFAs | 32.01 | 40.27 |

| PUFAs | 49.04 | 39.76 |

| UFAs/SFAs | 4.27 | 4.01 |

| Item | Ctrl | Innova | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical composition | ||||

| Lipids, % | 1.54 | 1.59 | 0.09 | 0.66 |

| Proteins, % | 20.58 | 20.30 | 0.43 | 0.65 |

| Total polyphenols, mg/kg | 94.39 | 140.78 | 3.73 | <0.01 |

| Cholesterol, mg/100 g | 37.62 | 37.20 | 0.79 | 0.70 |

| FAMEs (% of total FAs) | ||||

| C14:0 | 1.53 | 1.55 | 0.1 | 0.91 |

| C16:0 | 22.83 | 20.94 | 0.31 | <0.01 |

| C17:0 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| C18:0 | 27.60 | 21.38 | 0.47 | <0.01 |

| C20:0 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| C14:1 | 1.60 | 3.11 | 0.21 | <0.01 |

| C16:1 n-9 | 0.86 | 1.08 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| C17:1 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.98 |

| C18:1 cis | 31.46 | 36.63 | 0.70 | <0.01 |

| C18:1 cis vaccenic | 2.39 | 2.24 | 0.15 | 0.47 |

| C18:1 trans | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.41 |

| C18:2 cis | 3.71 | 4.56 | 0.3 | 0.06 |

| C18:3 n-6 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| C18:3 n-3 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| C20:3 n-6 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| C20:4 n-6 | 1.01 | 1.18 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| C22:5 n-3 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.31 |

| SFAs | 52.81 | 45.05 | 0.64 | <0.01 |

| MUFAs | 37.62 | 44.35 | 0.81 | 0.01 |

| PUFAs | 6.15 | 6.71 | 0.29 | 0.17 |

| Nutritional indices | ||||

| n-3 | 4.19 | 4.96 | 0.3 | 0.08 |

| n-6 | 1.96 | 1.75 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| n-3/n-6 | 2.15 | 2.96 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| TI | 1.51 | 1.09 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

| AI | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| H/H | 1.55 | 1.93 | 0.05 | <0.01 |

| PI | 11.89 | 12.64 | 0.36 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavallo, C.; Amato, A.; Lopreiato, V.; Paparone, N.; Scalone, D.; Litrenta, F.; Liotta, L. Improving Sustainability in Buffalo Finishing: Olive Cake Supplementation and Its Effects on Performance and Meat Quality. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12117. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212117

Cavallo C, Amato A, Lopreiato V, Paparone N, Scalone D, Litrenta F, Liotta L. Improving Sustainability in Buffalo Finishing: Olive Cake Supplementation and Its Effects on Performance and Meat Quality. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12117. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212117

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavallo, Carmelo, Annalisa Amato, Vincenzo Lopreiato, Nicoletta Paparone, Danilo Scalone, Federica Litrenta, and Luigi Liotta. 2025. "Improving Sustainability in Buffalo Finishing: Olive Cake Supplementation and Its Effects on Performance and Meat Quality" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12117. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212117

APA StyleCavallo, C., Amato, A., Lopreiato, V., Paparone, N., Scalone, D., Litrenta, F., & Liotta, L. (2025). Improving Sustainability in Buffalo Finishing: Olive Cake Supplementation and Its Effects on Performance and Meat Quality. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12117. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212117