1. Introduction

Urological cancers, including prostate cancer, urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), represent a major subset of solid malignancies, with prostate cancer being the second most common cancer in men worldwide [

1]. Over recent decades, advances in surgery, systemic therapies, and radiotherapy (RT) have improved outcomes, especially in localized disease. Among these, RT has remained a cornerstone of curative treatment, particularly in prostate and bladder cancers, offering organ preservation and excellent disease control in selected patients [

2,

3].

At the same time, the field of cancer immunotherapy (IO) has undergone a transformative revolution. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1 have become standard of care for multiple tumor types, including RCC and advanced bladder cancer [

4,

5,

6]. These agents restore antitumor immune activity by removing inhibitory signals that suppress T-cell activation, leading to durable responses in a subset of patients. However, not all tumors are equally responsive to immunotherapy. Prostate cancer, for instance, remains “immunologically cold” owing to low mutational burden, limited immune infiltration, and an immunosuppressive microenvironment [

7,

8].

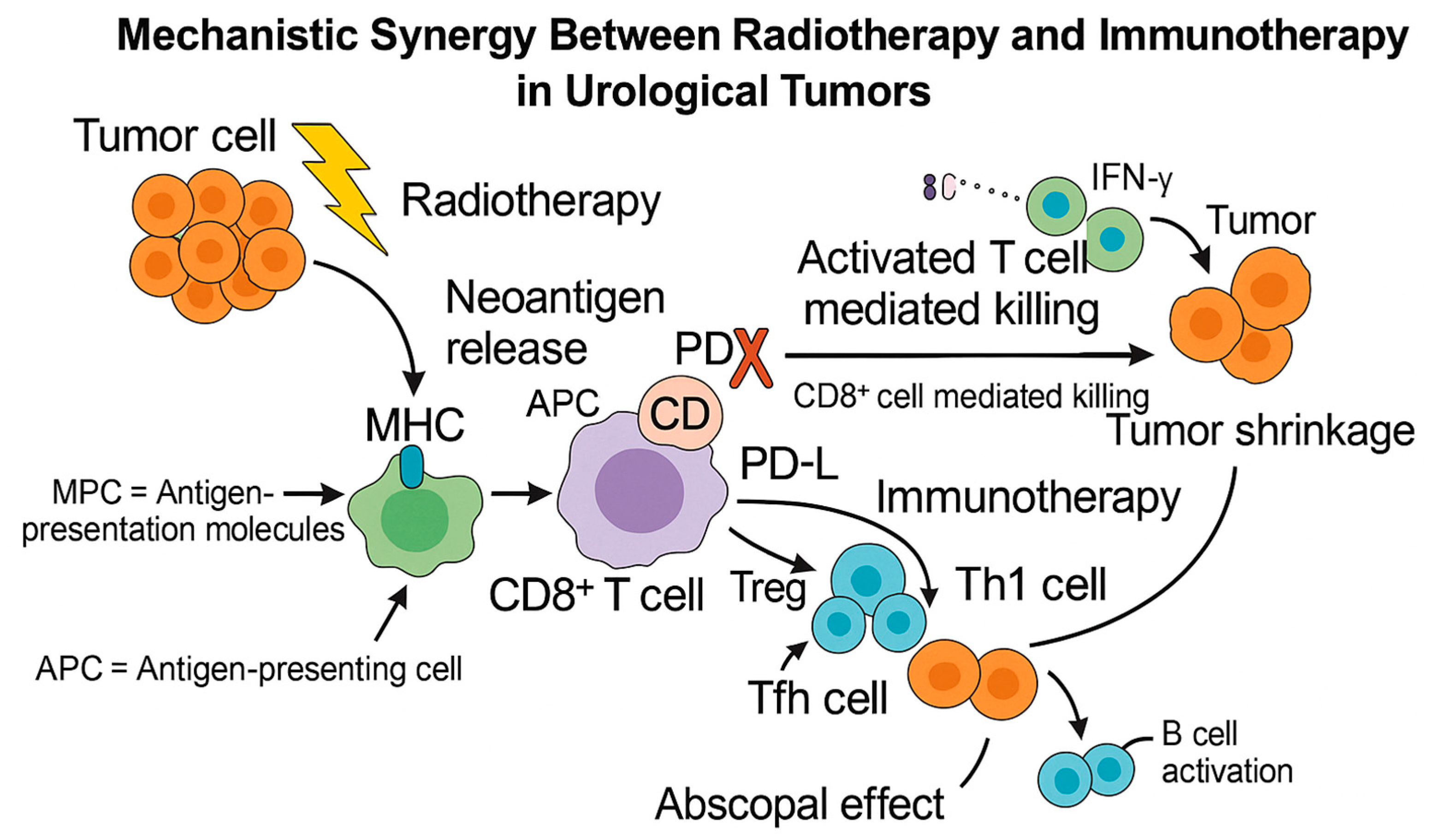

Against this background, there is growing interest in combining RT with IO as a synergistic strategy to overcome immune resistance. RT, traditionally viewed as a local modality, also exerts systemic immunomodulatory effects through mechanisms such as immunogenic cell death, enhanced antigen presentation, and recruitment of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (

Figure 1) [

9,

10,

11]. In certain preclinical and clinical settings, RT has been linked to the abscopal effect—regression of distant, non-irradiated metastases thought to be mediated by immune activation [

12,

13,

14].

Nevertheless, the immunological consequences of RT are not uniformly beneficial. The magnitude and consistency of systemic immune activation vary substantially between tumor types, doses, and fractionation schedules. Some studies suggest that RT may also upregulate immunosuppressive pathways, such as TGF-β signaling or recruitment of regulatory T cells, which could attenuate the expected synergy with IO [

15,

16]. Thus, while preclinical evidence supports a biologically plausible rationale, clinical translation remains challenging and context dependent.

The theoretical synergy between RT and IO has catalyzed a wave of translational and clinical research across various cancer types. In urological oncology, this intersection remains relatively underexplored but increasingly promising. Early phase trials in muscle-invasive bladder cancer and metastatic prostate cancer now evaluating diverse RT—IO combinations, while preclinical studies continue to clarify mechanisms of response and resistance [

17,

18,

19]. Critical questions persist regarding optimal sequencing, dose, patient selection, and the risk of compounded toxicity [

20].

This narrative review aims to explore the evolving landscape of RT—IO integration in urological cancers. We examine the biological rationale underlying this approach, summarize current clinical evidence and ongoing trials and discuss the challenges that must be addressed to fully realize its therapeutic potential. By bridging insights from radiation oncology, immunology, and urologic oncology, we aim to critically assess whether this convergence represents a genuine therapeutic advancement or an overhyped paradigm awaiting validation.

To enhance transparency, we briefly outline our literature search strategy. A narrative review of preclinical and clinical evidence on RT—IO integration in urological cancers was performed using PubMed/MEDLINE and Embase with predefined search terms (e.g., bladder cancer, RCC, prostate cancer, radiotherapy, SBRT, immunotherapy, ICIs). ClinicalTrials.gov was also queried for ongoing and completed trials. Only English-language studies were included, and reference lists were manually screened. The last search was updated on 30 September 2025 to include recent clinical trials and conference abstracts published between April and September 2025.

2. Immunotherapy in Urological Cancers

The advent of ICIs has reshaped treatment paradigms across various malignancies, and urological cancers have not been an exception. While not all genitourinary tumors exhibit equal responsiveness, substantial progress has been made, particularly in bladder and renal cell carcinomas.

2.1. Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer is among the most immunoresponsive urological malignancies. The use of intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy—one of the earliest forms of cancer immunotherapy—demonstrated the potential for immune modulation decades before ICIs emerged. In the metastatic setting, multiple ICIs targeting PD-1/PD-L1 have shown efficacy in urothelial carcinoma.

Notably, agents such as atezolizumab, nivolumab, and avelumab have been approved for second-line or maintenance settings after platinum-based chemotherapy [

5,

6,

19]. The JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial established avelumab maintenance as a new standard of care for patients achieving disease control after initial chemotherapy [

21]. For cisplatin-ineligible patients, first-line use of ICIs remains an option, particularly in those with high PD-L1 expression [

6].

2.2. Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma is inherently immunogenic and was historically treated with cytokine-based therapies like IL-2 and IFN-α. Modern immunotherapy has dramatically improved outcomes. Dual checkpoint blockade (nivolumab plus ipilimumab) demonstrated superior overall survival compared to sunitinib in the CheckMate 214 trial, especially in intermediate- and poor-risk patients [

4].

Combination strategies of ICIs with VEGF-targeting agents (pembrolizumab plus axitinib) have also gained widespread acceptance as frontline treatments, supported by trials such as KEYNOTE-426 [

22]. Immunotherapy has thus become integral to the management of advanced RCC, with ongoing studies exploring its role in adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings.

2.3. Prostate Cancer

Unlike bladder and RCC, prostate cancer has shown limited and inconsistent response to ICIs in clinical practice. Factors such as low tumor mutational burden (TMB), sparse immune cell infiltration, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) render the disease immunologically “cold.” Large scale trials evaluating agents like ipilimumab and nivolumab have demonstrated only modest or no survival benefit in unselected patient population. Clinically meaningful responses are largely confined to specific molecular subsets, particulary those with mismatch-repair deficiency (dMMR)/microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status or DNA damage repair (DDR) alterations (

Table 1) [

7,

8,

23].

Although the overall efficacy of ICIs in prostate cancer remains limited, ongoing studies continue to explore combination strategies—such as pairing ICIs with androgen-receptor-targeted therapies, PARP inhibitors, vaccines, or radiotherapy—to enhance immune responsiveness. The KEYNOTE-199 and CheckMate 650 trials are notable efforts testing these approaches, with preliminary activity observed primarily in biomarker-selected cohorts [

7,

18].

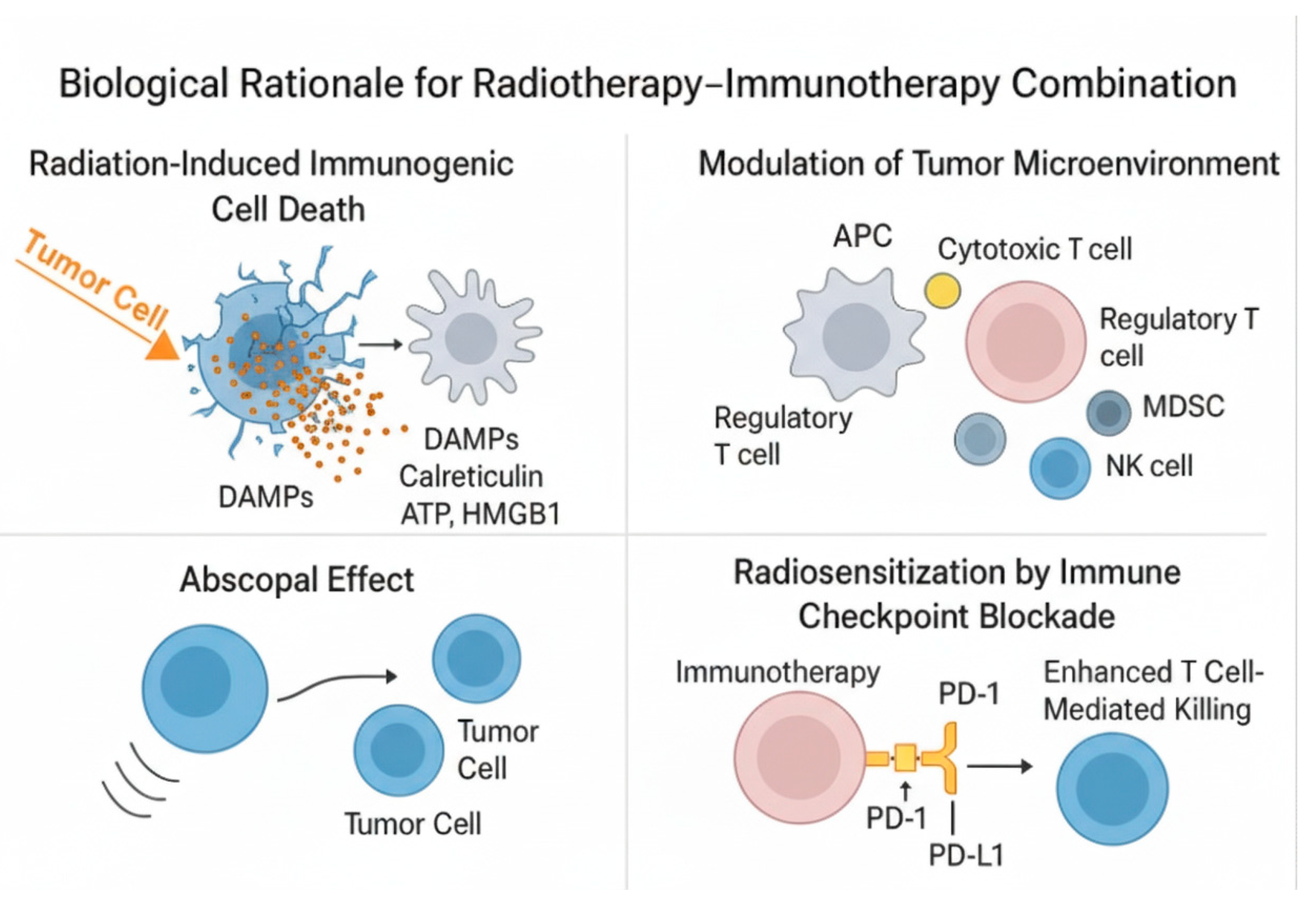

3. Biological Rationale for Radiotherapy–Immunotherapy Combination

The combination of radiotherapy (RT) and immunotherapy (IO) is grounded in the growing understanding of the complex interplay between local radiation-induced tumor cell death and systemic immune modulation. While RT has traditionally been considered a localized cytotoxic treatment, accumulating evidence suggests that it can also act as an immune-priming agent, potentially converting “cold” tumors into “hot,” immunologically active ones.

Radiation induces direct DNA damage in tumor cells, leading to apoptosis, necrosis, or mitotic catastrophe. Crucially, it can also cause immunogenic cell death (ICD)—a form of cell death that elicits a strong immune response. ICD is characterized by the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as calreticulin, ATP, and HMGB1, which enhance antigen uptake and maturation of dendritic cells (DCs), facilitating presentation of tumor antigens to naïve T cells [

14,

26]. Following ICD, tumor neoantigens are taken up by antigen-presenting cells (APCs)—primarily DCs—which migrate to lymph nodes and present these antigens to T cells via MHC class I molecules. Radiation also upregulates MHC-I expression and co-stimulatory molecules on both tumor cells and APCs, promoting T-cell priming and activation (

Figure 2) [

27].

In addition to cytotoxic CD8

+ T-cell activation, radiation-induced antigen release also promotes MHC class II–mediated presentation by professional APCs, leading to the recruitment and differentiation of CD4

+ T-cell subsets. Among these, Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ and IL-12 that sustain CD8

+ expansion and cytotoxic function, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells enhance B-cell activation and antibody diversification, whereas regulatory T cells (Tregs) may transiently decrease or undergo phenotypic reprogramming following irradiation, further shifting the immune balance toward activation [

27,

28]. Moreover, several innate-sensing pathways are triggered by RT-induced nucleic-acid release. Cytosolic DNA activates the cGAS–STING pathway, leading to type-I interferon secretion that enhances DC recruitment and antigen cross-presentation, while Toll-like receptors (TLRs) detect RNA/DNA motifs from dying cells, amplifying DC maturation and cytokine release [

26]. Concurrently, natural killer (NK) cells recognize stress ligands on irradiated tumor cells and secrete IFN-γ that reinforces adaptive priming, and tumor-associated macrophages may repolarize toward an M1-like phenotype, characterized by increased antigen presentation and nitric-oxide production, although this depends on radiation dose and fractionation [

29].

Beyond antigen presentation, RT exerts significant influence on the tumor microenvironment. It promotes the influx of cytotoxic CD8

+ T cells, NK cells, and macrophages, while potentially reducing immunosuppressive populations such as Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [

28]. Additionally, RT may enhance local cytokine release—such as IFN-γ, CXCL10, and IL-1β—which supports immune activation and recruitment of effector cells [

29]. Through these cumulative effects, RT contributes to reshaping the immune contexture of tumors toward a more pro-inflammatory and antigen-presenting phenotype.

The most intriguing immune-mediated consequence of RT is the abscopal effect—a phenomenon in which localized irradiation leads to regression of metastatic tumors at distant, non-irradiated sites [

13,

30]. Although this effect is rare, it has been more frequently observed when RT is combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), suggesting that immunotherapy may unlock its systemic potential. By blocking PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 signaling, ICIs prevent T-cell exhaustion, allowing the adaptive immune response triggered by RT to persist and expand. Preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that concurrent administration of RT and ICIs leads to greater tumor control than either modality alone [

31,

32].

Collectively, these mechanisms highlight the biological foundation for RT—IO synergy, where radiotherapy acts not only as a local cytotoxic agent but also as an immune activator that primes systemic antitumor responses, ultimately enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy.

4. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

The theoretical synergy between RT and IO has been increasingly supported by preclinical and early clinical evidence, particularly in the context of urological cancers. While data are still emerging, early findings suggest that combining these modalities can enhance tumor control and immune activation; however, the strength and consistency of this effect vary across tumor types, reflecting both biological heterogeneity and trial maturity.

4.1. Bladder Cancer

In bladder cancer, the case for RT—IO integration is among the strongest. Bladder tumors are historically responsive to immune modulation, as evidenced by the success of intravesical BCG and more recently, ICIs. Moreover, RT is already used in bladder-preserving treatment regimens. Preclinical studies have shown that radiation can enhance antigen presentation and promote a more inflamed TME, including upregulation of PD-L1 expression and increased infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes [

33]. These findings have led to the design of clinical trials evaluating concurrent use of RT and IO. The S/N1806 (SWOG/NRG) phase III trial (NCT03775265) investigates the addition of atezolizumab to trimodal therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer, aiming to improve bladder-intact event-free survival (BI-EFS) and systemic control [

34]. The KEYNOTE-992 (NCT04241185) phase III trial evaluates pembrolizumab plus chemoradiotherapy versus CRT alone, with BI-EFS as the primary endpoint. The study remains active, with results pending.

Preliminary institutional series suggest feasibility and manageable toxicity, but no phase III data are yet available. [

35]. Recent data from 2025 further reinforce this concept. The NEXT trial [

36] evaluated adjuvant nivolumab following chemoradiation in localized disease, while biomarker analyses from CheckMate 274 [

37] and NEODURVARIB [

38] highlighted PD-L1, TMB, and DDR signatures as potential predictors of benefit. Collectively, these findings strengthen the translational and clinical rationale for RT—IO integration in bladder-preserving and perioperative settings.

4.2. Renal Cell Carcinoma

In contrast, RCC presents a more complex landscape. Despite being highly immunogenic and responsive to checkpoint blockade, RCC has traditionally been considered radioresistant and has not been a standard indication for radiotherapy. However, emerging evidence challenges this view. Preclinical models demonstrate that high-dose SBRT can reprogram the tumor immune microenvironment, increasing T cell infiltration, enhancing antigen presentation, and promoting inflammatory cytokine signaling. These findings have catalyzed novel clinical designs exploring RT—IO synergy in metastatic RCC. The COMBAT RCC (NCT04071223) [

39] and CYTOSHRINK (NCT04090710) [

40] trials are evaluating SBRT + nivolumab ± ipilimumab in metastatic or neoadjuvant settings. Early-phase outcomes indicate disease control rates of 60–70%, objective response rates (ORR) of 16–25%, and grade ≥3 toxicities below 15%, demonstrating safety and biological plausibility. Mature data are pending, but the biological rationale remains strong. Preliminary results from related studies, such as the NIVES trial, support feasibility, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of around 8 months—comparable to systemic IO combinations. [

41]. Recent multidisciplinary reviews highlight the ongoing role of radiotherapy in metastatic RCC, particularly for palliative and skeletal indications, often combined with ICI-based systemic therapy [

42].

4.3. Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer remains the most challenging of the urological malignancies for RT—IO combinations. These tumors are typically “cold” in immunological terms—characterized by low mutational burden, minimal T-cell infiltration, and a predominantly immunosuppressive milieu. RT may partially overcome this resistance through immunogenic cell death, enhanced antigen expression, and remodeling of the TME [

8]. The CheckMate-650 trial (NCT02985957) assessed dual checkpoint blockade (nivolumab + ipilimumab) in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), yielding objective response rates of approximately 25% in pre-chemotherapy and 10% in post-chemotherapy settings, albeit with grade ≥3 toxicity in about 40% of patients [

43]. The ongoing KEYNOTE-991 phase III trial (NCT04191096) evaluates pembrolizumab in combination with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) and enzalutamide (without radiotherapy component), while the UCSF phase II trial (NCT06528210) investigates pembrolizumab administered concurrently with definitive radiotherapy and ADT in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer. These trials aim to determine whether immune priming can improve biochemical control and progression-free survival [

44,

45]. Recent phase III trials, such as KEYNOTE-991 and KEYNOTE-641, have explored pembrolizumab plus androgen receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic prostate cancer, although without radiotherapy components. Their results provide important context for future multimodal designs integrating RT with immunotherapy in biomarker-enriched settings [

44,

46].

4.4. Summary

Taken together, these studies highlight a growing body of translational and clinical research supporting the integration of RT and IO in urological oncology. While bladder cancer appears closest to clinical implementation, RCC remains promising but exploratory, and prostate cancer is still investigational. Continued evaluation in biomarker-selected populations, along with optimization of timing, sequencing, and dosing, will be critical for defining the clinical role of this therapeutic paradigm (

Table 2).

5. Challenges and Barriers

Despite the promising biological rationale and encouraging early evidence, the integration of RT and IO in the treatment of urological cancers remains complex and continually evolving. Multiple scientific, clinical, and logistical challenges must be addressed before this strategy can be widely adopted in standard care.

One of the most pressing issues is the optimal sequencing and timing of RT and IO. It remains unclear whether radiation should be administered before, during, or after immunotherapy to maximize synergy. Preclinical data suggest that concurrent administration may amplify immune priming, whereas a staggered approach could reduce toxicity and immune exhaustion [

47]. Clinical trial data comparing different regimens are still limited, and the answer may ultimately depend on tumor type, radiation dose, and immunotherapy class.

Another critical factor is radiation dose and fractionation. Conventional fractionation schedules used in many curative RT protocols may not be ideal for immune activation. Conversely, hypofractionated or ablative doses—commonly used in SBRT—appear to enhance immunogenicity but may also pose risks of immune-related toxicity [

48]. There is a lack of consensus on the immuno-optimizing dose parameters, and very few clinical trials stratify patients by radiation dose intensity.

Toxicity management also represents a major barrier, particularly when combining ICIs with RT. While both modalities are generally well-tolerated independently, their combination can lead to overlapping side effects such as pneumonitis, colitis, cystitis, or dermatitis, depending on the treatment site. Furthermore, immune-related adverse events are often unpredictable and may be exacerbated by the inflammatory effects of RT [

20,

49]. Similar observations have been reported in thoracic malignancies, where sequential or concurrent RT—IO was associated with a higher incidence of pneumonitis, particularly when high-dose fields overlapped with lung tissue [

50]. Careful monitoring and multidisciplinary coordination are essential, particularly for elderly or comorbid patients common in urological oncology.

A significant unmet need is the identification of predictive biomarkers. Not all patients benefit from RT—IO combinations, and the ability to select likely responders would reduce both unnecessary toxicity and treatment costs. Biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression, TMB, microsatellite instability (MSI), and DDR mutations are being evaluated in various settings, but none are yet validated to guide RT–IO use in urological cancers [

8].

Logistical barriers also persist, particularly regarding trial design and patient recruitment. Many current studies are early-phase, single-arm, and underpowered to assess long-term outcomes. Larger randomized controlled trials are needed but face challenges in enrolling biomarker-selected populations, coordinating multidisciplinary care, and integrating evolving standards of care across medical, radiation, and urologic oncology disciplines [

51].

Lastly, there are economic and accessibility concerns. Combining two high-cost modalities—IO and precision RT—can strain healthcare resources. Access to modern radiation equipment and immunotherapeutic agents may be limited in low- and middle-income settings, potentially exacerbating disparities in cancer care delivery [

52].

In sum, while RT—IO combinations hold transformative potential, their clinical implementation requires a nuanced approach. Future research should focus not only on efficacy but also on precision, personalization, and practicality, ensuring that this promising strategy is implemented safely, effectively, and equitably in routine clinical practice.

6. Future Directions and Opportunities

The evolving intersection of RT and IO in urological cancers presents not only challenges but also compelling avenues for innovation. As early clinical trials continue to define feasibility and biological plausibility, future research must focus on enhancing precision, personalization, and broader accessibility of this therapeutic strategy.

One of the most promising directions involves biomarker-driven patient selection. While ICIs have shown variable efficacy across urological tumors, emerging data suggest that molecular and immunologic signatures—such as TMB, MSI, DDR gene alterations, and PD-L1 expression—can help identify those most likely to benefit from RT—IO combinations [

53,

54]. Additionally, the integration of immune gene expression profiles, T-cell receptor (TCR) diversity, and even gut microbiome analysis may enhance the predictive landscape. Future trials will likely incorporate these biomarkers into eligibility criteria, stratification, and adaptive dosing algorithms.

Another exciting opportunity lies in novel immunotherapeutic agents beyond checkpoint inhibitors. Investigational therapies such as STING agonists, Toll-like receptor (TLR) modulators, oncolytic viruses, cancer vaccines, and bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) are being explored in preclinical and early-phase settings. These agents may synergize with radiation in different ways—by amplifying innate immune activation, enhancing tumor-specific cytotoxicity, or expanding the antigen repertoire available for immune recognition [

55,

56,

57].

From a technological perspective, advances in image-guided radiotherapy, adaptive planning, and dose painting offer unprecedented precision in RT delivery. These innovations could enable immuno-optimized radiation protocols, delivering biologically effective doses to stimulate the immune response while sparing critical lymphoid tissues and immune effector zones [

58]. Furthermore, real-time immuno-monitoring, liquid biopsies, and radiomic biomarkers may provide early feedback on treatment response and immune engagement, allowing for mid-course treatment adaptation [

59].

The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning into RT—IO clinical workflows also hold significant potential. AI can assist in identifying predictive imaging or histologic patterns, optimizing treatment planning, and stratifying patients based on integrated multi-omic data. These tools will be especially valuable in interpreting complex biomarker profiles and guiding clinical decision-making in real-time [

60].

There is also growing interest in expanding the role of RT—IO combinations to earlier stages of disease. In urological cancers, this includes neoadjuvant settings (prior to cystectomy or nephrectomy), adjuvant therapy, and biochemical recurrence after surgery. Earlier intervention may allow immune priming before widespread metastatic evolution, potentially improving long-term disease control or even cure in high-risk patients [

61].

Recent analyses emphasize cost-related barriers to PD-(L)1 therapies and the potential of low-dose regimens to improve accessibility in low- and middle-income countries [

62].

Finally, equity and global accessibility must be central to future planning. As RT—IO strategies mature, ensuring their availability in diverse clinical settings—including low- and middle-income countries—will require innovative approaches to cost reduction, simplified treatment protocols, and telemedicine-supported care models [

63].

In sum, the future of RT—IO integration in urological oncology shows strong potential pending further validation, but requires a multidisciplinary, biomarker-informed, and patient-centered approach. Success will depend not only on scientific breakthroughs but also on thoughtful clinical trial design, equitable implementation, and a commitment to translating innovation into meaningful outcomes for all patients.

7. Conclusions

The convergence of RT and IO represents one of the most dynamic frontiers in contemporary oncologic research. In urological cancers—where treatment landscapes are rapidly evolving—this combination holds unique promise for enhancing both local tumor control and systemic immune-mediated responses. As evidence accumulates, it is becoming clear that RT not only complements IO by inducing immunogenic cell death and modulating the TME but may also serve as a critical catalyst in transforming immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” and responsive phenotypes.

Bladder and renal cell carcinomas have emerged as natural candidates for early clinical application, owing to their baseline immunogenicity and existing integration of IO into standard care. In contrast, prostate cancer poses a greater challenge due to its immune evasiveness yet also represents a compelling opportunity for innovation—particularly in biomarker-enriched subsets and in combination with radiation-induced immune priming.

Despite the enthusiasm, RT—IO combinations are not without complexity. Key challenges remain in defining optimal treatment sequencing, dosing, toxicity mitigation, and patient selection. The absence of validated predictive biomarkers, the risk of compounded adverse events, and the cost implications of dual-modality therapy underscore the need for thoughtful clinical trial design and multidisciplinary collaboration.

Looking ahead, the success of this therapeutic paradigm will depend on precision-based approaches that integrate molecular and immunologic profiling, next-generation imaging, real-time monitoring, and adaptive treatment strategies. Importantly, equitable implementation across diverse healthcare systems must remain a parallel priority.

In conclusion, while the integration of radiotherapy and immunotherapy in urological oncology is still in its formative stages, the scientific rationale and emerging clinical evidence strongly support its potential. With continued research, innovation, and collaboration, this strategy may redefine the future of cancer treatment—offering not only improved survival but more personalized and durable outcomes for patients across the urological cancer spectrum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.B., D.A.G. and R.D.M.; methodology, C.A.B. and A.M.; validation, D.A.G., R.D.M. and B.F.G.; investigation, C.A.B., A.M.A.P., C.M., I.A.V. and D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.B.; writing—review and editing, D.A.G., R.D.M. and B.F.G.; visualization, C.A.B.; supervision, D.A.G. and R.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) for editing and formatting assistance. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Catalin—Andrei Bulai and Dr. Dragos–Adrian Georgescu serve as Guest Editors for the Special Issue to which this manuscript is submitted. To avoid any conflict of interest, the peer review and editorial decision-making for this submission will be handled entirely by an independent editor.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| IO | Immunotherapy |

| ICIs | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte–Associated Protein 4 |

| RCC | Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| mCRPC | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer |

| SBRT | Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy |

| TMB | Tumor Mutational Burden |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite Instability-High |

| ICD | Immunogenic cell death |

| DDR | DNA Damage Repair |

| APC | Antigen-Presenting Cell |

| DC | Dendritic Cell |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette-Guérin |

| PFS | Progression-Free Survival |

| ORR | Objective Response Rate |

| BI-EFS | Bladder-intact event-free survival |

| NK | Natural Killer (cell) |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TCR | T-cell Receptor |

| STING | Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| TLR | Toll-like Receptor |

| BiTE | Bispecific T-cell Engager |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearnaley, D.; Syndikus, I.; Mossop, H.; Khoo, V.; Birtle, A.; Bloomfield, D.; Graham, J.; Kirkbride, P.; Logue, J.; Malik, Z.; et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1047–1060, Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30273-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- James, N.D.; Hussain, S.A.; Hall, E.; Jenkins, P.; Tremlett, J.; Rawlings, C.; Crundwell, M.; Sizer, B.; Sreenivasan, T.; Hendron, C.; et al. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Aren Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balar, A.V.; Galsky, M.D.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Powles, T.; Petrylak, D.P.; Bellmunt, J.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Durán, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; Loriot, Y.; Vogelzang, N.J.; De Giorgi, U.; Oudard, S.; Retz, M.M.; Castellano, D.; Bamias, A.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff, J.N.; Alumkal, J.J.; Drake, C.G.; Thomas, G.V.; Redmond, W.L.; Farhad, M.; Cetnar, J.P.; Ey, F.S.; Bergan, R.C.; Slottke, R.; et al. Early evidence of anti–PD-1 activity in enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 52810–52817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Wargo, J.A.; Ribas, A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 168, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S.; Golden, E.B.; Formenti, S.C. The “abscopal effect” in radiation therapy: Is immune modulation the key? Future Oncol. 2013, 9, 655–662. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, F.G.; Bourhis, J.; Coukos, G. Radiotherapy combination opportunities leveraging immunity for the next oncology practice. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mole, R.H. Whole body irradiation—Radiobiology or medicine? Br. J. Radiol. 1953, 26, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, W.; Irabor, O.C.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Hesser, J.; Demaria, S.; Formenti, S.C. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, E.B.; Frances, D.; Pellicciotta, I.; Demaria, S.; Barcellos-Hoff, M.H.; Formenti, S.C. Radiation fosters dose-dependent and chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e28518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Pilones, K.A.; Wennerberg, E.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. In situ vaccination by radiotherapy to improve responses to anti-CTLA-4 treatment. Vaccine 2015, 33, 7415–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Demaria, S.; Golden, E.B.; Formenti, S.C. Role of Local Radiation Therapy in Cancer Immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddart, R.A.; Hall, E.; Lewis, R.; Birtle, A.; Jenkins, P.; Syndikus, I. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Results from a randomised phase 3 NCRI trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 475–487. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, R.R.; Bossé, D.; Xie, W.; Werner, L.; Reda, M.; Alva, A. Phase I trial of combining enzalutamide with nivolumab for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CheckMate 650). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. S15), 5036. [Google Scholar]

- Geynisman, D.M.; Trabulsi, E.J.; DiPaola, R.S. Checkpoint inhibitors in genito-urinary malignancies: A review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 113, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Postow, M.A.; Sidlow, R.; Hellmann, M.D. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Piulats, J.M.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Goh, J.; Ojamaa, K.; Hoimes, C.J.; Vaishampayan, U.; Berger, R.; Sezer, A.; Alanko, T.; et al. Pembrolizumab for treatment-refractory metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Multicohort, open-label phase II KEYNOTE-199 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Powles, T.; van der Heijden, M.S.; Balar, A.V.; Necchi, A.; Dawson, N.; O’Donnell, P.H.; Balmanoukian, A.; Loriot, Y.; et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: A single-arm, multi-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Procopio, G.; Plimack, E.R.; et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reits, E.A.; Hodge, J.W.; Herberts, C.A.; Groothuis, T.A.; Chakraborty, M.; Wansley, E.K.; Camphausen, K.; Luiten, R.M.; De Ru, A.H.; Neijssen, J.; et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Liang, H.; Xu, M.; Yang, X.; Burnette, B.; Arina, A.; Li, X.-D.; Mayceri, H.; Beckett, M.; Darga, T.; et al. STING-dependent cy-tosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon–dependent antitumor im-munity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity 2014, 41, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugade, A.A.; Sorensen, E.W.; Gerber, S.A.; Moran, J.P.; Frelinger, J.G.; Lord, E.M. Radia-tion-induced IFN-γ production within the tumor microenvironment influences antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 3132–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaria, S.; Ng, B.; Devitt, M.L.; Babb, J.S.; Kawashima, N.; Liebes, L.; Formenti, S.C. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 58, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, A.B.; Lim, M.; DeWeese, T.L.; Drake, C.G. Radiation and checkpoint blockade im-munotherapy: Radiosensitisation and potential mechanisms of synergy. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e498–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovedi, S.J.; Adlard, A.L.; Lipowska-Bhalla, G.; McKenna, C.; Jones, S.; Cheadle, E.J.; Stratford, I.J.; Poon, E.; Morrow, M.; Stewart, R.; et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5458–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, Y.; Matsushita, H.; Peres, E.A.C.; Hasegawa, K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Barber, G.N. Low-dose irradiation enhances antitumor effects of immune checkpoint blockade in a mouse model of bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 395–403. [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou, J.A.; McBride, S.M.; Wu, C.L.; Sargos, P.; Nguyen, P.L.; Bosch, W.R. S1806 (SWOG/NRG): A Randomized Phase III Trial of Chemoradiotherapy ± Atezolizumab in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03775265. SWOG/NRG Oncology Cooperative Groups. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03775265 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Tissot, G.; Xylinas, E. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in Combination with Chemoradiotherapy Versus Chemoradiotherapy Alone in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: The MK-3475-992/KEYNOTE-992 Trial. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2023, 9, 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galarza Fortuna, G.M.; Grass, D.; Maughan, B.L.; Jain, R.K.; Dechet, C.; Beck, J.; Schuetz, E.; Sanchez, A.; O’Neil, B.; Poch, M.; et al. Nivolumab adjuvant to chemo-radiation in localized muscle-invasive urothelial cancer: Primary analysis of a multicenter, single-arm, phase II, investigator-initiated trial (NEXT). J. Immunother. Cancer. 2025, 13, e010572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- UroToday. ASCO-GU 2025: Adjuvant Nivolumab vs. Placebo for High-Risk Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma—Additional Efficacy Outcomes Including Overall Survival in Patients with MIBC from CheckMate-274. 2025. Available online: https://www.urotoday.com/conference-highlights/asco-gu-2025/asco-gu-2025-bladder-cancer/158278-asco-gu-2025-adjuvant-nivolumab-vs-placebo-for-high-risk-muscle-invasive-urothelial-carcinoma-additional-efficacy-outcomes-including-overall-survival-in-patients-with-mibc-from-checkmate-274.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- UroToday. ASCO-GU 2022: Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of MIBC Treated with Durvalumab Plus Olaparib in the Neoadjuvant Setting (NEODURVARIB Trial). 2022. Available online: https://www.urotoday.com/conference-highlights/asco-gu-2022/asco-gu-2022-bladder-cancer/135464-asco-gu-2022-comprehensive-molecular-characterization-of-mibc-treated-with-durvalumab-plus-olaparib-in-the-neoadjuvant-setting-neodurvarib-trial.html (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Grünwald, V.; Merseburger, A.S.; Bedke, J.; Schmid, S.C.; Staehler, M. COMBAT-RCC: Combination of Nivolumab and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (NCT04071223); ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04071223; University Hospital Essen: Essen, Germany, 2019. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04071223 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Choudhury, A.; North, S.; Winquist, E. CYTOSHRINK: Neoadjuvant Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Localized Renal Cell Carcinoma (NCT04090710); ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04090710; The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04090710 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Masini, C.; Iotti, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Bellia, R.S.; Buti, S.; Salaroli, F.; Zampiva, I.; Mazzarotto, R.; Mucciarini, C.; Vitale, M.G.; et al. Nivolumab in Combination with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Pretreated Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Results of the Phase II NIVES Study. Eur Urol. 2022, 81, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; McKay, R.R. Mitigating the Risk of Skeletal Events in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2025, 11, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Pachynski, R.K.; Narayan, V.; Fléchon, A.; Gravis, G.; Galsky, M.D.; Mahammedi, H.; Patnaik, A.; Subudhi, S.K.; Ciprotti, M.; et al. Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Preliminary Analysis of Patients in the CheckMate 650 Trial. Cancer Cell. 2020, 38, 489–499.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratzke, C.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Peer, A.; Sendur, M.A.N.; Retz, M.; Goh, J.C.; Loidl, W.; Jayram, G.; Byun, S.S.; Kwak, C.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus enzalutamide and androgen deprivation therapy versus placebo plus enzalutamide and androgen deprivation therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: The randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-991 study. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UCSF Clinical Trials. Pembrolizumab in Combination with Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Radiation for High-Risk Localized or Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer (NCT06528210). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06528210. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06528210 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Graff, J.N.; Burotto, M.; Fong, P.C.; Pook, D.W.; Zurawski, B.; Manneh Kopp, R.; Salinas, J.; Bylow, K.A.; Kramer, G.; Ratta, R.; et al. KEYNOTE-641 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus enzalutamide versus placebo plus enzalutamide for chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: The randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-641 study. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. Combining radiotherapy and cancer immunotherapy: A paradigm shift. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaue, D.; McBride, W.H. Opportunities and challenges of radiotherapy for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, H.; Guo, S.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, B.; Wu, D.; Xia, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, T. Risk factors for pneumonitis after the combination treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitors and thoracic radiotherapy. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tang, C.; Wang, X.; Soh, H.; Seyedin, S.; Cortez, M.A.; Krishnan, S.; Massarelli, E.; Hong, D.; Naing, A.; Diab, A.; et al. Combining radiation and immunotherapy: A new systemic therapy for solid tumors? Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atun, R.; A Jaffray, D.; Barton, M.B.; Bray, F.; Baumann, M.; Vikram, B.; Hanna, T.P.; Knaul, F.M.; Lievens, Y.; Lui, T.Y.M.; et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1153–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.M.; Kato, S.; Bazhenova, L.; Patel, S.P.; Frampton, G.M.; Miller, V.; Stephens, P.J.; Daniels, G.A.; Kurzrock, R. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Shaukat, F.; Velho, P.I.; Kaur, H.; Shenderov, E.; Pardoll, D.M.; Lotan, T.L. Clinical features and therapeutic outcomes in patients with advanced prostate cancer and DNA mismatch repair gene mutations. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, L.; Gajewski, T.F. Molecular pathways: Targeting the stimulator of inter-feron genes (STING) in the immunotherapy of cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4774–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, I.; Gaudernack, G.; Gerritsen, W.; Huber, C.; Parmiani, G.; Scholl, S.; Thatcher, N.; Wagstaff, J.; Zielinski, C.; Faulkner, I.; et al. Therapeutic vaccines for cancer: An overview of clinical trials. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.S.; Du, L.; Naing, A.; Chen, H.X.; Enderlin, M.; Colen, R. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of a bispecific T-cell engager targeting PSMA in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. S15), 5014. [Google Scholar]

- Jeraj, R.; Cao, Y.; Deasy, J.O.; Jaffray, D.A.; Ten Haken, R.K.; Marks, L.B. Radiomics and radiogenomics for precision radiotherapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 1504–1509. [Google Scholar]

- Bratman, S.V.; Yang, S.Y.; Iafolla, M.A.J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Fernetich, D. Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis to detect residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy in bladder cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 902–911. [Google Scholar]

- Bibault, J.E.; Giraud, P.; Burgun, A. Big data and machine learning in radiation oncology: State of the art and future prospects. Cancer Lett. 2016, 382, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Kockx, M.; Rodriguez-Vida, A.; Duran, I.; Crabb, S.J.; Van der Heijden, M.S.; Szabados, B.; Pous, A.F.; Gravis, A.; Herranz, U.A.; et al. Clinical efficacy and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: ABACUS trial. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Labaig, P.; Mohamed, F.; Tan, N.J.I.; Sanna, I.; El Bairi, K.; Khan, S.Z.; Akhade, A.; Amaral, T.; Trapani, D.; Patel, A.; et al. Expanding access to cancer immunotherapy: A systematic review of low-dose PD-(L)1 inhibitor strategies. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 225, 115564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, D.; Tenenbaum, L.; Vera, R. Access to radiotherapy for cancer treatment: From global cancer policy to action. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 29, 430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Laskar, S.G.; Sinha, S.; Krishnatry, R.; Grau, C.; Mehta, M.; Agarwal, J.P. Access to Radiation Therapy: From Local to Global and Equality to Equity. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e2100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).