This section first focuses on the overall flow field characteristics of the bridge. Starting from the steady-state flow behavior, the analysis clarifies the distributions of velocity and pressure, as well as aerodynamic force characteristics under various angles of attack and wind directions. Then, the unsteady features of the flow field are further examined to identify how flow instability affects the overall structural performance of the bridge. Finally, based on the local force characteristics of auxiliary components, a safety assessment is conducted, leading to the identification of aerodynamic performance patterns influenced by the pedestrian walkway slabs and cable troughs.

3.1.1. Time-Averaged Features of Flow Field

To evaluate the aerodynamic characteristics of the pedestrian walkway slabs and cable troughs on a railway bridge under different angles of attack (α), a study was conducted on the distribution of mean velocity and streamlines around the bridge cross-section under representative attack angles, as shown in

Figure 7. Here, α > 0 indicates a downward-sloping wind impinging from above the bridge deck, while α < 0 corresponds to an upward-sloping wind from below. The background color in the figure indicates the velocity magnitude, with the incoming flow direction from right to left. From the figure, it can be observed that the velocity contours (in m/s) and streamlines clearly illustrate the flow structure and its variation. As the angle of attack α decreases, significant changes occur in the upstream and downstream flow fields around the bridge. At α = +20° and +10°, as shown in

Figure 7a,b, the airflow exhibits no significant separation at the leading edge compared to the other three cases. This allows the flow to remain attached over the upper surface of the bridge deck. However, at α = 10°, a small separation bubble is present, located near the walkway slab, which may induce local oscillations, while the flow at α = 20° does not show the small bubble. This separation bubble at α = 10° is caused by the relatively high position of the cable trough.

When the angle of attack decreases further (

Figure 7d,e), the incoming flow is directed more upward, a noticeable flow separation occurs on the top surface of the bridge. The strong shear layers and near-wall recirculation zones develop above the bridge deck, indicating intensified flow disturbance caused by the auxiliary structures. This can easily induce unstable vortex formations, leading to increased fluctuations in aerodynamic loads on the bridge structure. Indeed, the fluctuation may negatively affect structural fatigue resistance and the stability of the cable troughs. The wake region at α = 0° significantly expands (

Figure 7c), particularly beneath the bridge deck. The streamlines become distorted, and sharp velocity gradients appear in localized areas. At α = –10°, multiple small-scale vortices form above the deck, suggesting complex multi-scale vortex interactions that, while transient in nature, appear as averaged features in the time-mean flow field.

The variation in flow separation across attack angles aligns with the numerical findings of Guo et al. [

39]. The suction forces generated by the vortices over the bridge deck can reduce the stability of the auxiliary structures, posing potential risks to train operation. Previous studies have primarily focused on the direct aerodynamic effects of crosswinds on moving trains, neglecting the indirect influence of bridge-mounted components. The present work helps address this gap by elucidating how these auxiliary structures contribute to crosswind-induced hazards.

An interesting topological feature appears at α = +10° (

Figure 7b), where reattachment occurs above the deck. The small separation bubble at the leading edge destabilizes the flow, making it sensitive to small variations in attack angle—behavior reminiscent of elongated cross-sections.

Figure 8 further illustrates the normalized velocity and two-dimensional streamlines on the lateral center plane (

y-axis) at additional attack angles. At α = +2.5°, +5°, and +7.5°, the flow topology resembles that at α = 0° (

Figure 7c), whereas at α = +12.5° it transitions toward the pattern observed at α = +10° (

Figure 7b). Similarly, the flow at α = +15° and +17.5° resembles that at α = +20° (

Figure 7a). These comparisons indicate that the threshold attack angle separating the no-reattachment and reattachment topologies lies between 7.5° and 10°, while the transition between the +10° and +20° configurations occurs between 12.5° and 15°. Further investigation is needed to precisely determine these critical thresholds.

Figure 9 shows the normalized lateral velocity field along the lateral center plane at different attack angles. The black contour lines indicate regions where the normalized velocity equals 0.99, marking the outer edge of the shear layer. As the magnitude of the attack angle decreases, this shear-layer boundary gradually moves away from the deck surface, consistent with the trends observed in

Figure 7.

Figure 10 presents the mean surface pressure coefficient (Cp) distributions on the bridge surface for five angles of attack (α). At α = +20° (

Figure 10a), the upper surface of the walkway slab experiences strong stagnation, with Cp approaching +0.9 near the leading edge. On the downstream, cable trough side surface at rear edge of the slab experiences a pronounced positive pressure while the top surface of the trough shows a deep negative pressure (Cp about –1.6). This is due to the flow accelerates in the local region (see

Figure 10a), resulting in negative pressure.

When α decreases to +10° (

Figure 10b), the high-pressure region on the slab leading edge weakens (Cp ≈ +0.6), and the suction peaks on the downstream face are less intense (Cp ≈ –1.2). This moderates the aerodynamic loads, though significant pressure asymmetry remains. At α = 0° (

Figure 10c), the flow is parallel to the bridge surface. Cp varies modestly between +0.2 on the windward face and –0.5 on the leeward face. Under negative angles (α = –10° and –20°,

Figure 7d,e), the high-pressure region shifts to the underside of the slab, the top surface of the bridge exhibits stronger suction, effectively reversing the sign of the net lift force compared to positive α.

Figure 11 shows the pressure distribution at measurement points located 10 mm above the bridge deck. The x’ axis represents the normalized distance, with the outer edge of the windward cable trough set as 0 and the outer edge of the leeward cable trough as 1 (as illustrated in

Figure 10c), and 20 pressure monitoring points are evenly distributed across this span. The T

W and T

L region in the figure corresponds to the cable trough area, while S

W and S

L denotes the walkway slab region. It can be observed that under a large attack angle (α = +20°), the windward cable trough experiences the highest pressure. A slight pressure drop is seen on the adjacent walkway slab, and a sharp pressure drop appears near the deck leading edge (around x’ = 0.2), which is related to the accelerated flow over the sloped surface of the walkway slab toward the bridge deck (

Figure 10b). The pressure then gradually decreases across the bridge deck. In the leeward S

L area, the downwash from the sloped deck encounters the flat surface of the walkway slab, resulting in flow obstruction and a pressure increase. This is followed by a sudden drop in pressure at the T

L boundary due to step-induced flow separation, after which a slight pressure recovery occurs on the cable trough surface.

For α = +10°, the windward-side pressure trend is similar to that of α = +20°, but with reduced magnitude. On the bridge deck, however, greater differences are observed. The pressure on the windward side of the bridge deck reaches a low value of Cp ≈ –1.0 and then shows a recovery trend similar to the +20° case. This difference is due to the presence of a recirculation zone on the windward deck under the +10° case, where pressure drops sharply and then gradually recovers due to the blocking effect of the recirculating flow. In the leeward SL and TL regions, the trend is similar to that observed under the large attack angle of +20°.

Under the parallel inflow condition (α = 0°), pressure variations are very mild. A sharp pressure drop occurs in the windward TW region due to flow separation behind the step, followed by a gradual change. A pressure rise is observed on the leeward side.

For negative attack angles, the pressure variation is similar. Due to the shielding effect of the underside of the bridge, pressure changes across the bridge span are minimal, and the overall Cp distribution remains negative. The tendency for uplift of the walkway slab and cable trough may be more pronounced.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the pressure in the walkway slab and cable trough regions is heavily influenced by the flow field. The highest positive pressure occurs at +20°, while the strongest local negative pressure on the windward SW region appears at 0°. Based on this, the flow field effects under different yaw angles will be studied next for three representative attack angles: +20°, 0°, and –20°.

Figure 12 illustrates effects of yaw angle of crosswinds on the velocity contour at three typical attack angles of α = +20°, 0°, –20°. From the figure, we can see how the wind-direction yaw (β = –20°, 0°, +20°) shape the mean velocity field and streamline topology around the bridge cross-section. At α = +20°, with a zero yaw (

Figure 12(a1)), the walking slab’s upper surface generates a strong stagnation zone at the trailing edge, feeding a high-velocity shear layer that detaches from the cable trough next to it and rolls into a large, symmetric recirculation bubble downstream. Introducing a larger yaw (β = +30°, see

Figure 12(a2)) delay this wake far behind: the acceleration above the leeward cable through significantly weakens, accompanied with a pair of trailing vortices located more downstream. A further yaw (β = 60°,

Figure 12(a3)) brings totally different flow patterns, only a single vortex appears right under the bridge leeward with a surrounding high velocity distribution, which is due to that a large yaw results in a weaker velocity of the spanwise component.

With the bridge deck aligned to the freestream at α = 0° (see

Figure 12(b1)–(b3)), most flow patterns at three yaw angles are similar to counterparts in that of α = 20°, an obvious discrepancy lay on the vortex attaching to the bridge upper surface in cases of α = 0°. This is because the sharp cable through leading edge at windward (see frame R

1 in

Figure 12(b1)) causes flow separates clearly, at a small yaw β = 0° and 30°, the larger velocity spanwise component stretches the vortex elongated till the trailing wake. While a larger yaw makes the vortex on the bridge with less momentum thus the spanwise range is reduced.

At α = –20°, as shown in

Figure 12(c1)–(c3), the incoming flow angles upward relative to the deck. At β = 0°, the shear layer detaches from the cable through’s leading edge, generating a vortex V

1 in diagonal direction of far wake; also, flow detach from the leeward slab’s underside, creating a dominant recirculation zone V

2 in the wake, showing a pair of counter-rotating vortices together. Yawing the wind to β = +20° forces V1 closer to the bridge and dominated with V2 upon the slab’s and through’s faces on the lee side, intensifying reverse flow and producing a compact, high-shear region. Furthermore, β = –20° yields an elevated separation bubble right above the slab: a series of new vortices emerges atop the deck and a strong vortex impinging the underside of the slab and through at leeward. In practice a closer vortex could increase fluctuating forces on the walkway slabs and cable troughs, with potential implications for fatigue life, vibration response, and overall structural integrity under crosswinds.

Figure 13 shows the velocity distribution of the airflow at 10 mm above the bridge deck in the horizontal plane. When the yaw angle is β = 0°, the flow speed is uniformly distributed along the bridge’s spanwise (y) direction, exhibiting a clear two-dimensional character (

Figure 13(a1,b1,c1)). Under a wind direction of β = 30° and an attack angle of α = 20° (

Figure 13(a2)), the plan-view speed contours remain nearly invariant along y and closely resemble those in

Figure 13(a1), indicating that spanwise flow dominates at high attack angles. This behavior persists in

Figure 13(a3) at large yaw angles: the pattern of the velocity field is similar to that at other attack angles, although its magnitude is reduced due to a smaller spanwise component. At α = 0° and –20° (

Figure 13(b2,c2)), the velocity gradually increases along y, and the velocity gradient aligns almost parallel to the wind direction, demonstrating the flow deflection induced by yaw; this also causes the T

L trough region to show a velocity variation along y. In subfigures (

Figure 13(b3,c3)), obliquely downward streaks appear on the deck, reflecting the more complex vortex structures that develop at large yaw angles.

Figure 14 illustrates the distribution of mean pressure coefficients on the bridge deck and its auxiliary components under different attack angles (α = +20°, 0°, –20°) and yaw angles (β = 0°, 30°, 60°). When α = +20° and β = 0° (a1), a distinct high-pressure stagnation zone (Cp ≈ +0.9) forms along the windward edge of the bridge deck, while strong suction regions (Cp ≈ –1.6) develop on the downstream edges and within the troughs, resulting in the largest pressure difference. As β increases to 30° (a2), the high-pressure region shifts along the windward side, and suction on the leeward face of the trough weakens. At β = 60°, with flow nearly lateral, elongated low-pressure bands form along the top surface in the wind direction, and the overall pressure gradient significantly decreases.

At α = 0°, β = 0° corresponds to flow parallel to the bridge deck without yaw. Due to seam-induced effects on the windward side, surface pressure tends to be lower near the windward edge and gradually increases toward the leeward side. With β = 30°, the pressure on the bridge deck increases, but the distribution remains relatively uniform. At β = 60°, surface pressure rises further, and oblique low-pressure streaks appear on the deck, corresponding to regions of vortex core extension shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, where abrupt pressure drops occur.

At α = –20°, the incoming flow impacts the underside of the bridge deck. When β = 0°, a clear high-pressure region (Cp ≈ +0.7) forms on the bottom surface, while suction appears on the upper surface. With β = 30°, the high-pressure zone shifts toward the leeward side, resulting in intensified negative pressure on the slab and trough surfaces and localized force amplification. At β = 60°, the extent of the bottom high-pressure region decreases, elongated low-pressure zones form on the top slab, suction weakens, and its distribution becomes more scattered, with the pressure gradient highly influenced by wind direction.

Overall, increasing the attack angle (α) intensifies the high pressure on the windward face and suction on the leeward face, leading to greater lift forces on auxiliary structures. Increasing the yaw angle (β) causes the pressure field to shift laterally along the bridge deck, producing pronounced asymmetric loading under negative attack angles. Therefore, design considerations must account for the combined effects of both attack and yaw angles to ensure aerodynamic stability and structural safety of walkway slabs and cable troughs under multiple operating conditions.

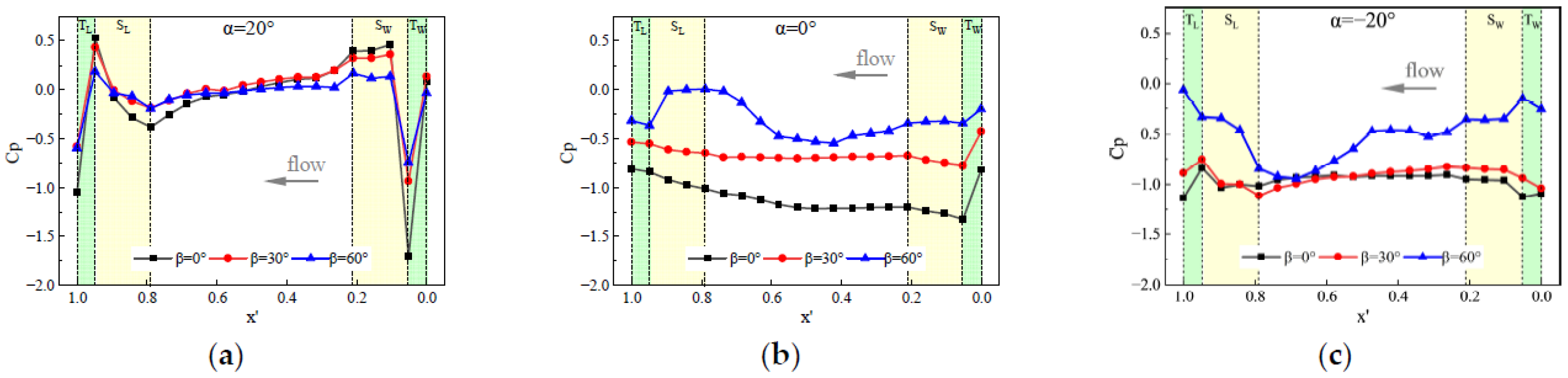

Figure 15 presents the centerline pressure distribution along the walkway slab and cable trough under different yaw angles for three representative attack angles.

At α = +20° (

Figure 15a), the pressure coefficient (Cp) distribution exhibits a distinct positive peak on the windward side of the upstream cable trough, followed by a sharp pressure drop across the transition from the trough to the walkway slab. A localized positive peak then appears over the slab, likely caused by flow acceleration through the gap between the trough and slab. At β = 0°, this peak reaches approximately Cp = 0.48, but decreases to about 0.18 at β = 60°, indicating that increasing yaw angles reduce direct flow impingement and thus weaken pressure buildup. As the slab region continues downstream, a slight drop in Cp is observed near the trough interface, followed by a continuous decay in the range of x′ ≈ 0.2–0.8, with the most rapid decay occurring at β = 0°. Near the leeward walkway slab, a pressure recovery is seen for all three yaw angles, attributed to the recessed geometry and stronger flow impingement in this region. A sudden pressure rise (–0.2 to 0.45) occurs at the transition between the walkway slab and the cable trough due to the step-like obstruction from the trough’s side wall—this corresponds to a step-induced stagnation effect in the flow field. The subsequent pressure drop is caused by flow separation around the protruding trough structure. Under α = +20°, the peak pressure location within the trough remains nearly unchanged across different yaw angles, indicating that the flow impingement location is not significantly affected by yaw. The pressure distribution pattern is primarily governed by the spatial arrangement of the bridge-mounted components.

Figure 15b corresponds to the α = 0° parallel inflow condition, where the Cp remains negative along the entire bridge span. For β = 0° and β = 30°, Cp remains nearly flat between –1.35 and –0.75, indicating a uniform suction load. A suction peak (–1.33) appears in the trough region (x′ ≈ 0.05), followed by a gradual recovery in the x′ ≈ 0.2–0.7 range due to boundary layer redevelopment. At β = 60°, the pressure recovery downstream of x′ ≈ 0.6 is attributed to separation vortices being limited to the upstream section of the deck. The slight positive pressure downstream and over the leeward slab arises from downward flow deflection induced by the upstream deck vortex (see

Figure 12(b3)). Compared to β = 0°, β = 30° slightly suppresses suction near mid-span, highlighting the influence of small yaw angles on boundary layer development.

Figure 15c illustrates the case of negative attack angle (α = –20°), where Cp remains negative across all yaw angles. For β = 0° and β = 60°, Cp values in the trough region (x′ ≈ 0.0–0.05) are approximately –1.1, and remain nearly flat across x′ = 0.1–0.8. On the leeward side (x′ > 0.8), the curves converge to Cp ≈ –0.95, indicating reduced sensitivity to small yaw angles. However, at β = 60°, a strong pressure recovery occurs around x′ ≈ 0.6 (Cp ≈ –0.25), driven by the larger vortex scales observed in

Figure 12(c1)–(c3). A slight suction drop is also noted near the edge of the walkway slab. Notably, under negative attack angles, the influence of yaw angle on pressure distribution is polarized: small yaw angles have a minimal effect, while large yaw angles lead to substantial pressure recovery, significantly increasing the pressure on the upper surfaces of both the slab and trough, thereby enhancing their aerodynamic stability. In summary, smaller yaw angles tend to induce stronger negative pressure (suction) over the bridge deck, increasing uplift forces and raising the risk of cover plate instability.

3.1.2. Unsteady Features of Surrounding Flows

Figure 16 presents instantaneous iso-surfaces of the Q-criterion colored by the spanwise velocity component, depicting the unsteady flow characteristics around the bridge structure and its auxiliary components (cable troughs and walkway slabs) under different angles of attack.

Under a positive attack angle of α = +10° (

Figure 16a), prominent vortex shedding is observed near the upper edge of the windward cable trough (R

W region), where the shedding vortices form a series of intermittent, tubular coherent structures along the flow direction. This indicates the presence of periodic vortex-induced oscillations in this region. Upon impacting the bridge deck, part of the flow is lifted upward along the surface shear layer, generating a typical horseshoe vortex system (R

B) near the leading edge of the cable trough, which extends spanwise to the leeward walkway slab. At the leeward edge of the cable trough (E

L), flow separation induced by geometric discontinuity also results in vortex shedding, though with smaller scale and lower intensity than in the R

W region. A large recirculation zone develops in the downstream wake, clearly indicated by the low spanwise velocity region in the visualization.

When the attack angle increases to α = +20° (

Figure 16b), the stronger inflow impact leads to more intense interaction with the deck surface, yet no distinct vortex shedding structures are observed in the R

W region. The shear layer development over the deck appears vaguer and more indistinct. Only scattered small-scale turbulent vortices with low energy and poor coherence are present on the leeward walkway slab. Near the cable trough edge (E

L), a notable flow acceleration occurs, resulting in stronger downstream separation and vortex shedding.

Under the parallel inflow condition of α = 0° (

Figure 16c), similar tubular vortex shedding structures appear near the RW region. However, compared to α = +10°, the vortex cores are shed farther from the bridge deck and persist longer, even extending to the upper edge of the leeward walkway slab and cable trough. This causes the region to remain in a prolonged separated low-speed zone, thereby preventing the formation of significant secondary turbulent separation near the E

L region.

In the negative attack angle conditions of α = –10° and –20° (

Figure 16d,e), the incoming flow approaches from below the deck, and the shielding effect of the bridge body on the upper flow field intensifies. As a result, no obvious shear layer develops over the deck. On the upper surface of the windward cable trough, flow accelerates rapidly and separates, with the resulting turbulent vortices continuously acting near the walkway slab (R

W). Flow over the leeward walkway slab is extremely weak, and only a few faint vortex structures can be observed near the cable trough edge (E

L), which may exhibit minor spanwise oscillatory instability.

In region R

W of

Figure 16c, the visible tube is the spanwise K-H roller issued from the windward leading edge. Its spanwise ripple is the phenomenon of a secondary three-dimensional instability, which is likely caused by the oblique K-H mode imposing a spanwise phase variation. The instability mechanism imprints a preferred wavelength that scales with the local shear-layer thickness, despite the spanwise-uniform geometry and zero yaw. The spanwise corrugation of the leading-edge shear layer disrupts spanwise coherence, accelerates transition and entrainment, thickens the separated region, and shifts energy to broadband turbulence, generally reducing globally coherent force oscillations.

Figure 17 illustrates the maximum turbulent kinetic energy (TKE)—defined as the peak value over the sampled time span—on the lateral center plane (along the

y-axis) around the bridge for various angles of attack. At α = +20°, high TKE levels are concentrated downstream of the leeward cable trough. At α = 0°, significant TKE appears above the bridge deck and the windward cable trough. When the attack angle decreases to –10° and –20°, intense TKE regions are mainly observed above the windward cable trough.

Comparison of these TKE distributions with the time-averaged flow structures shown in

Figure 7 reveals a strong macroscopic correspondence, though localized discrepancies remain at smaller scales. This indicates that, while the general flow topology is preserved, local vortex dynamics exhibit considerable temporal variability—highlighting the inherently unsteady nature of the flow around the bridge and its auxiliary components.

It is also worth noting that under turbulent winds or extreme meteorological conditions (e.g., typhoons, tornadoes, or thunderstorms), both separated and reattached flow patterns are expected to undergo substantial modifications [

41,

42]. Investigating these effects will form an important direction for future work.

To quantify the influence of unsteady characteristics in different regions,

Figure 18 presents the distribution of pressure standard deviation along the bridge deck centerline, as indicated in

Figure 14(b1), under various angles of attack. Under the α = +10° condition, a distinct surge in standard deviation appears at the normalized spanwise position x′ ≈ 0.2. This location corresponds to the end of the windward slope—precisely where the wall-attached tubular vortex shedding is observed on the right side of the R

B region in

Figure 16a. Local flow separation leads to significantly intensified surface pressure fluctuations. As the vortex structures decay along the deck’s shear layer, their unsteady energy gradually diminishes, resulting in a slow decrease in standard deviation from x′ = 0.2 toward both the windward and leeward directions.

For a higher attack angle of α = +20°, a sharp rise in pressure standard deviation is observed at the transition between the TL and SW regions. This is closely associated with strong disturbances caused by the abrupt geometric interface at this location under high-angle inflow. A secondary peak is also present in the downstream section of the TL region, further confirming that geometric transitions trigger localized flow instabilities. Due to the nearly perpendicular impact of the incoming flow at higher attack angles, flow separation over the deck is largely suppressed, resulting in overall lower standard deviation levels compared to the +10° condition.

Under the parallel inflow case (α = 0°), localized flow separation first occurs at the leading edge of TW, causing a short-term surge in fluctuation intensity within the TW and SW regions. As the separated vortex structures shed, near-wall pressure fluctuations decrease. However, due to the cumulative effect of recirculating vortices in the downstream region of the deck, the standard deviation increases steadily again, only gradually declining in the leeward SL region.

For negative attack angles α = –10° and –20°, where the inflow approaches from below the deck, the shielding effect of the bridge body on the upper flow field becomes more prominent, resulting in a relatively flat distribution of pressure standard deviation. Under the –10° condition, root-mean-square pressure values remain higher than those at –20°, and notable local variations persist in regions near TW, SW, SL, and TL, indicating stronger flow instabilities in these areas. In contrast, the –20° condition exhibits more suppressed flow behavior, with lower overall fluctuation levels and a more uniform distribution.

Figure 19 illustrates the changes in vortex structures induced by varying yaw angles. For α = 20°, since the incoming flow directly impinges on the bridge deck, changes in yaw angle primarily affect the direction of the wake, with relatively minor influence on the overall distribution of flow structures over the deck.

Under parallel inflow conditions, increasing yaw angle first alters the vortex evolution near the leading edge of the cable trough in the Rw region. The originally spanwise-aligned tubular vortices begin to tilt in the direction of the incoming flow, a phenomenon that becomes more pronounced at a yaw angle of 60°, while simultaneously weakening the vortex structures over the bridge deck.

For the negative attack angle case of α = –20°, most vortex structures under a 0° yaw angle detach from the bridge deck and remain relatively distant. As the yaw angle increases, the turbulent vortices within the recirculation zone tend to move closer to the bridge surface. Additionally, under large yaw conditions such as β = 60°, strong vortex formation and clear shedding are observed near the windward leading edge of the Rw region—an effect that is not present under small yaw angles.