Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange, Eriochrome Black T, and Methylene Blue by Silica–Titania Fibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Electrospun Fibers

| Photocatalyst | Dye | Time (min) | Efficiency (%) | kappkapp (min−1) | Form | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2-TiO2 Fibers | Methyl Orange | 480 | ~98 | 0.0021 | Fiber | This work |

| SiO2-TiO2 Fibers | Eriochrome Black T | 480 | ~98 | 0.0014 | Fiber | This work |

| SiO2-TiO2 Fibers | Methylene Blue | 480 | ~98 | 0.0016 | Fiber | This work |

| Cu-Ni/TiO2 | Rhodamine B | 90 | 97.0 | - | Powder | [15] |

| Nanosized TiO2 | Methylene Blue | 60 | 90 | - | Powder | [16] |

| GO/TiO2 | Methyl Orange | 240 | 90 | - | Powder | [17] |

| Ag-MoO3-TiO2 | Methyl Orange | 300 | 97 | - | Powder | [18] |

| Polymer modified-TiO2 | Methylene Blue | 90 | 93 | - | Powder | [19] |

| TiO2-Fe2O3 nanocomposite | Methylene Blue | 60 | 79.1 | - | Powder | [20] |

| B-GO-TiO2 | 4-NitroPhenol | 180 | 100 | - | Powder | [21] |

| TiO2–CNT | RhB | 80 | 100 | - | Powder | [22] |

| 5% Fe/TiO2 | Eosine Blue | 110 | 96.70 | - | Powder | [23] |

| Se-ZnS NCS | Methyl Orange | 160 | 95.00 | - | Powder | [24] |

| N-TiO2 | Methyl Orange | 200 | 90.00 | - | Powder | [25] |

| α-Bi2O3 | Methyl Orange | 150 | 95.00 | - | Powder | [26] |

| N-TiO2 nanorods | Methyl Orange | 250 | 80.00 | - | Powder | [27] |

| α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles | Methyl Orange | 100 | 95.31 | - | Powder | [28] |

| ZnO quantum dots | Methyl Orange | 160 | 97.00 | - | Powder | [29] |

| ZnO nanopyramid | Methyl Orange | 150 | 95.00 | - | Powder | [30] |

| Fe–ZnO | Methylene Blue | 180 | 92 | - | Powder | [31] |

| GO/TiO2 | Methylene Blue | 240 | 100 | - | Powder | [32] |

| Cd–ZnO | Methylene Blue | 240 | 89 | - | Powder | [33] |

| Fe3O4–ZnO NCS | Methylene Blue | 180 | 89.2 | - | Powder | [34] |

| N-Carbon quantum dots/TiO2 | Methylene Blue | 420 | 82.00 | - | Powder | [35] |

| S-TiO2 nanorods | Methylene Blue | 240 | 92.00 | - | Powder | [36] |

| Egg-NiO | Methylene Blue | 240 | 79.00 | - | Powder | [37] |

| TiO2rGOCdS | Methyl Orange | 240 | 100 | - | Powder | [38] |

| TiO2rGOCdS | Methylene Blue | 360 | 100 | - | Powder | [38] |

| CdS-TiO2 nanocomposites | Acid Blue | 120 | 95 | - | Powder | [39] |

| Green CS-TiO2 NPs | Methylene Blue | 90 | 98.5 | - | Powder | [40] |

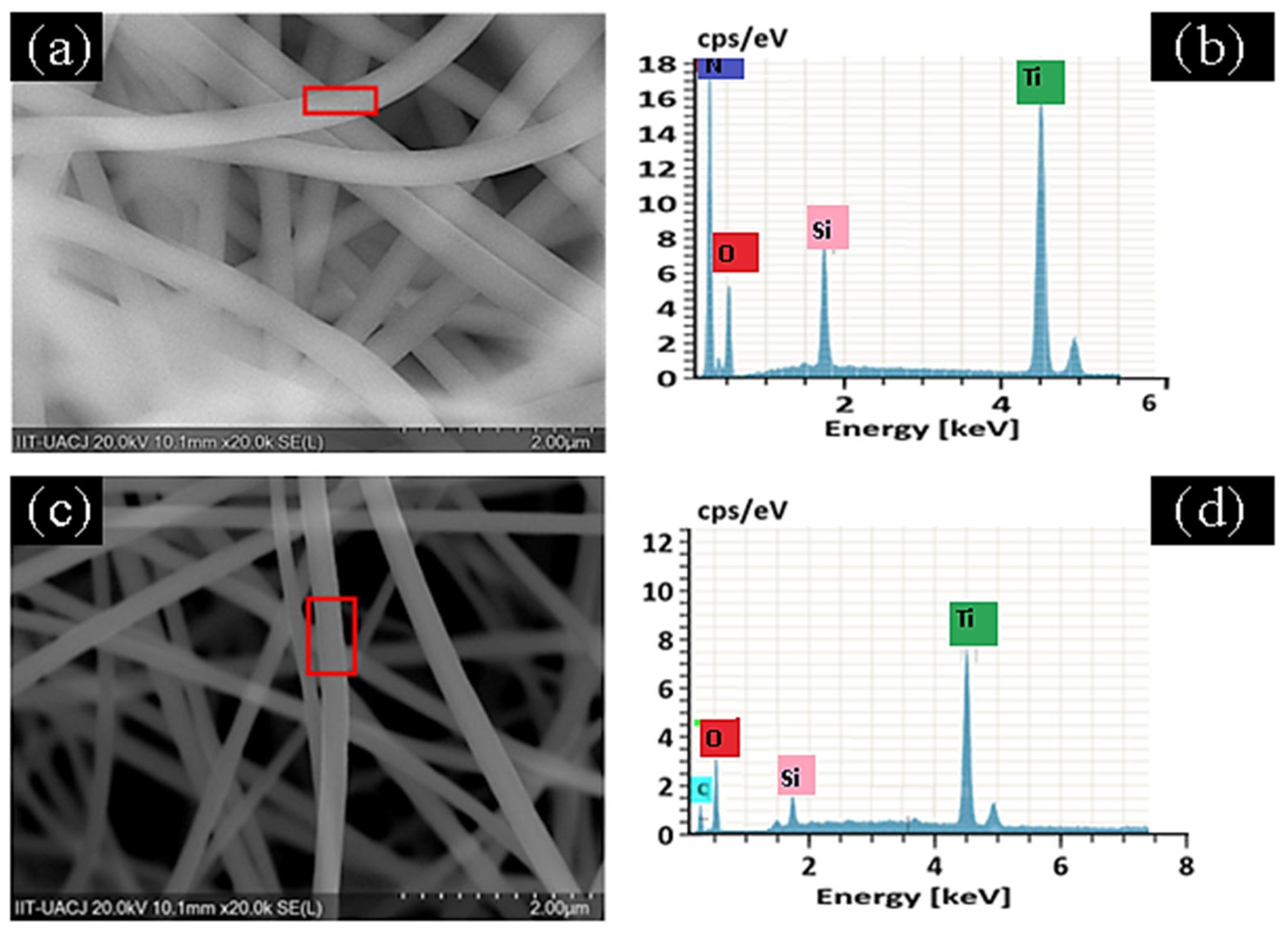

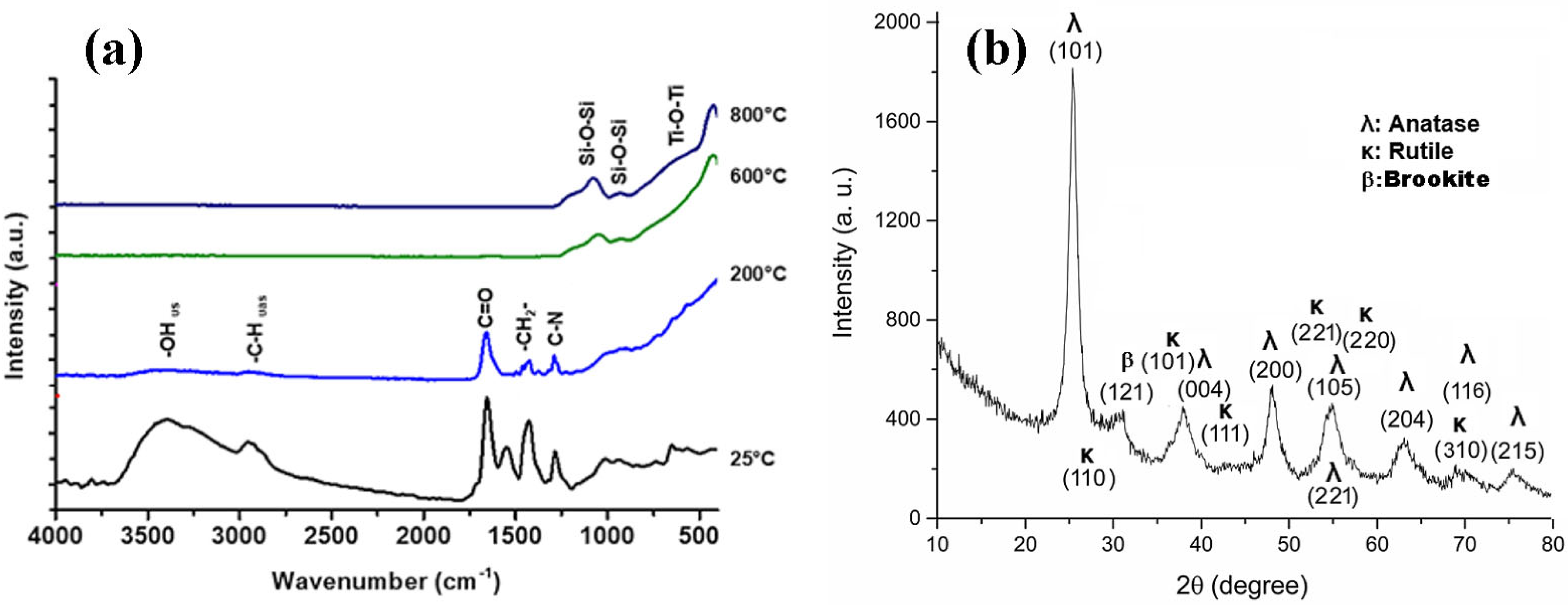

2.2. Thermal Treatment TTIP-TEOS-PVP Green Fibers

2.3. Characterization

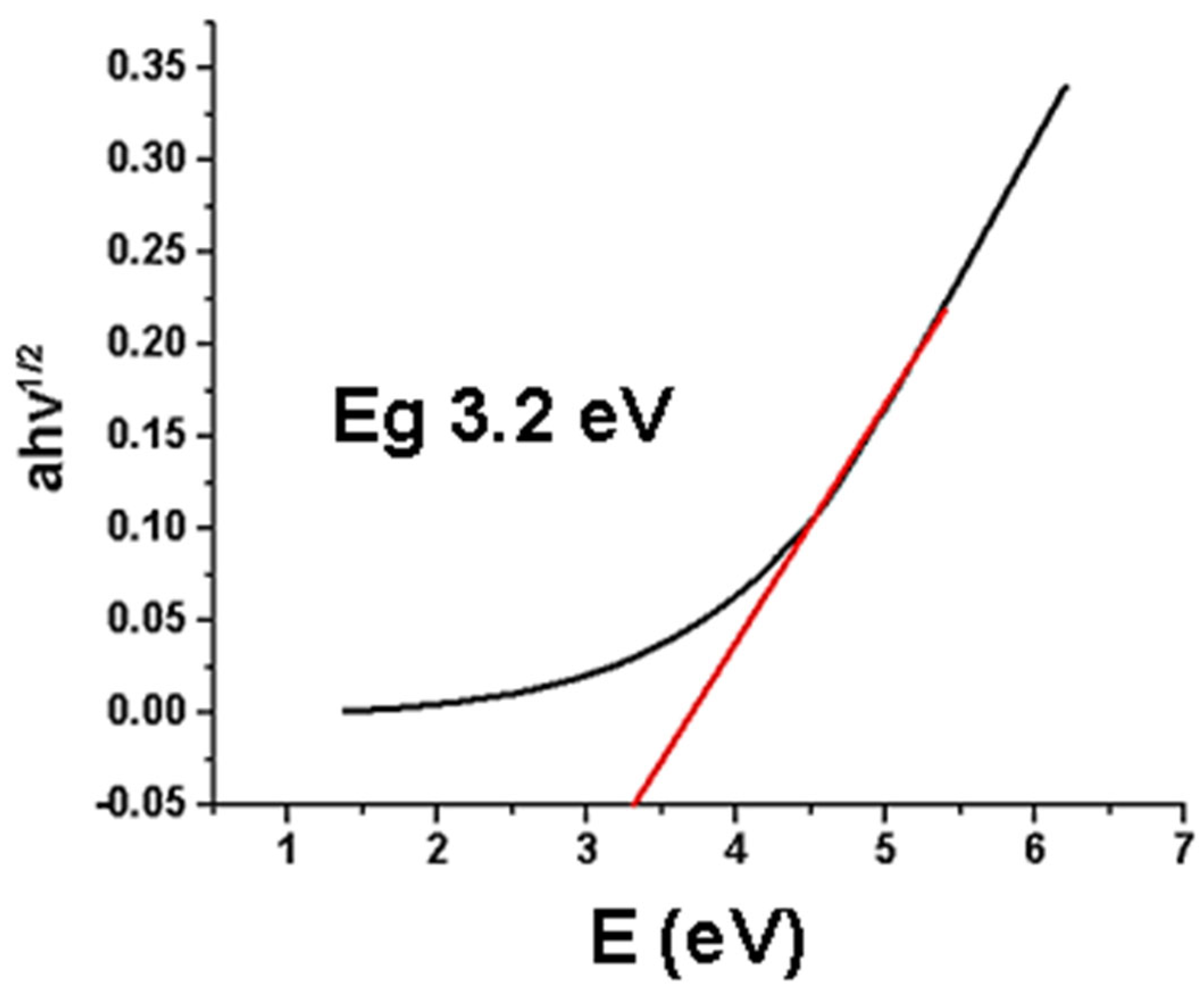

2.4. Tauc Plot

2.5. Photocatalytic Activity

2.6. Langmuir–Hinshelwood Kinetic Model in Photocatalysis

3. Results and Discussion

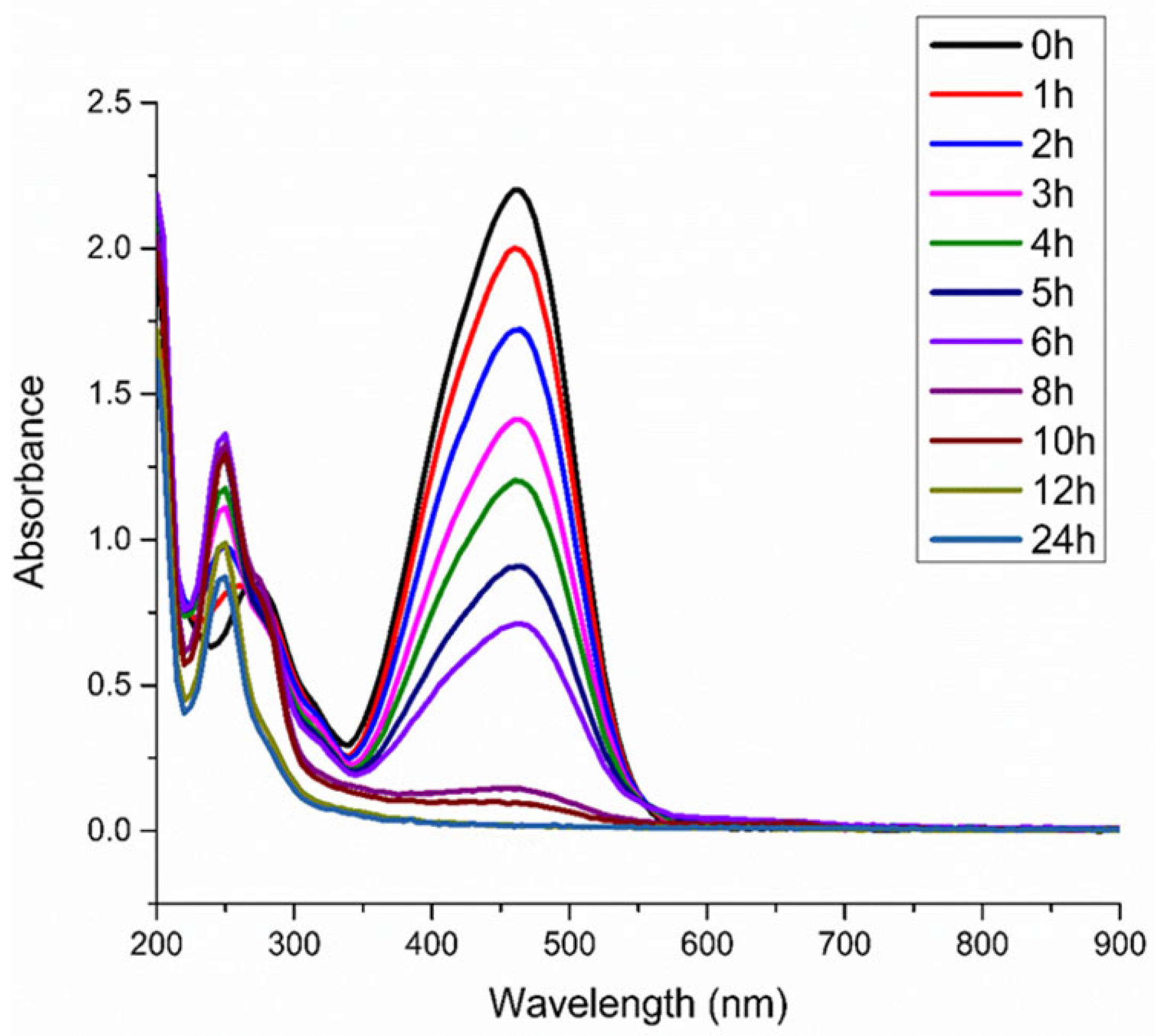

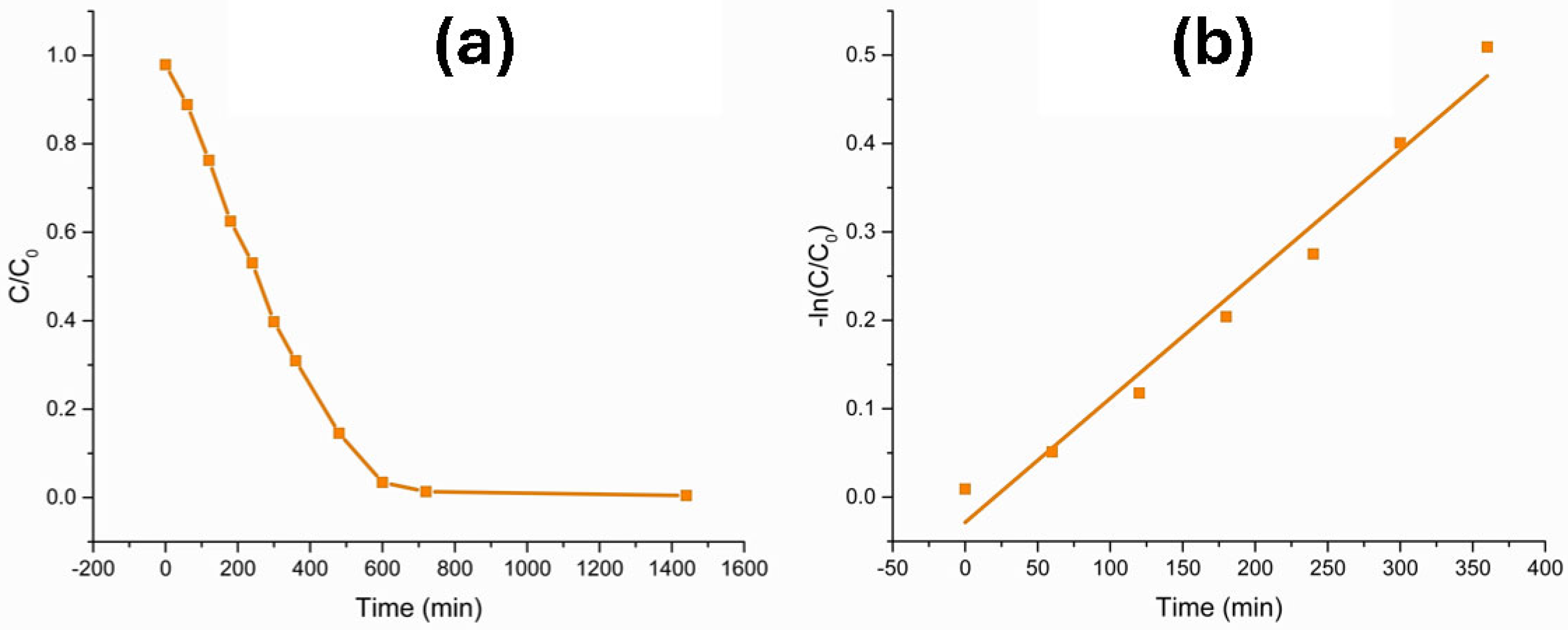

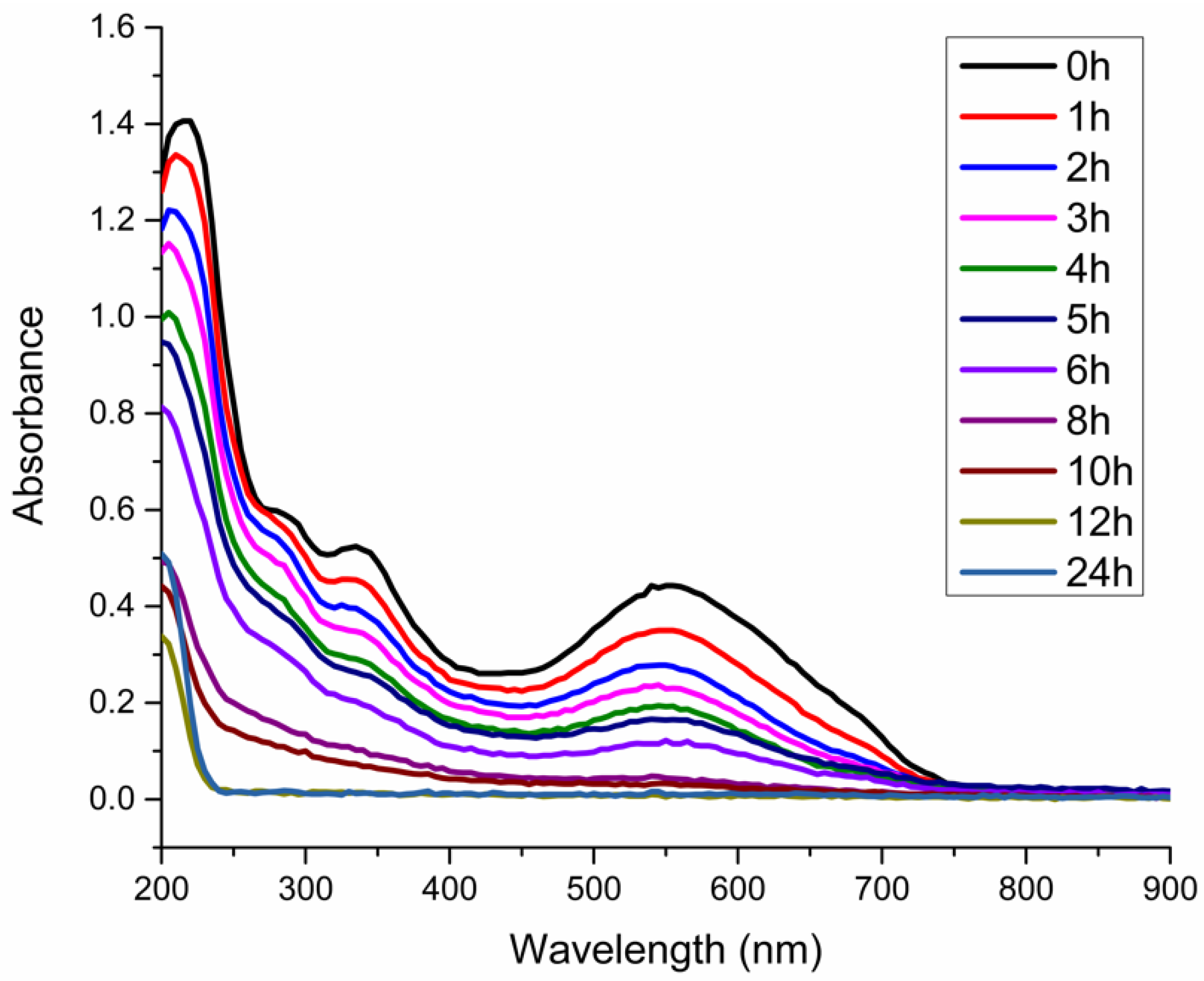

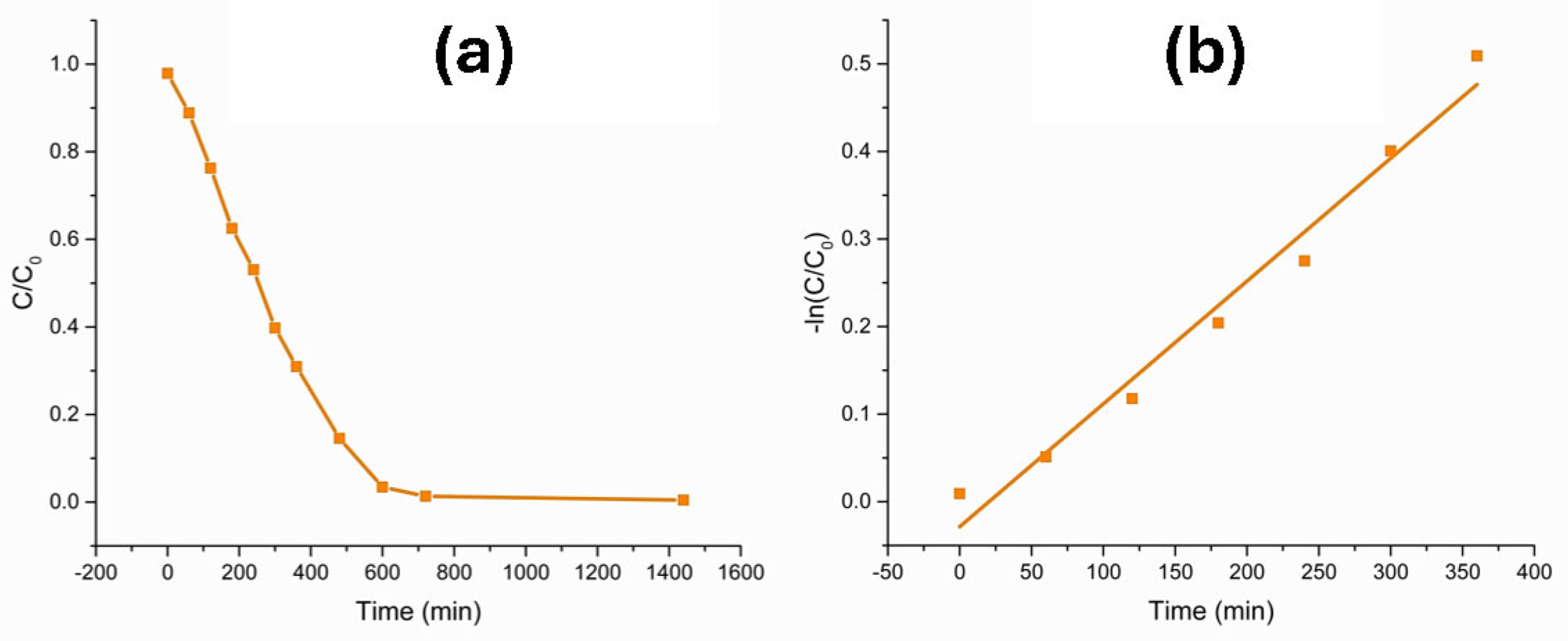

3.1. Degradation of Methyl Orange

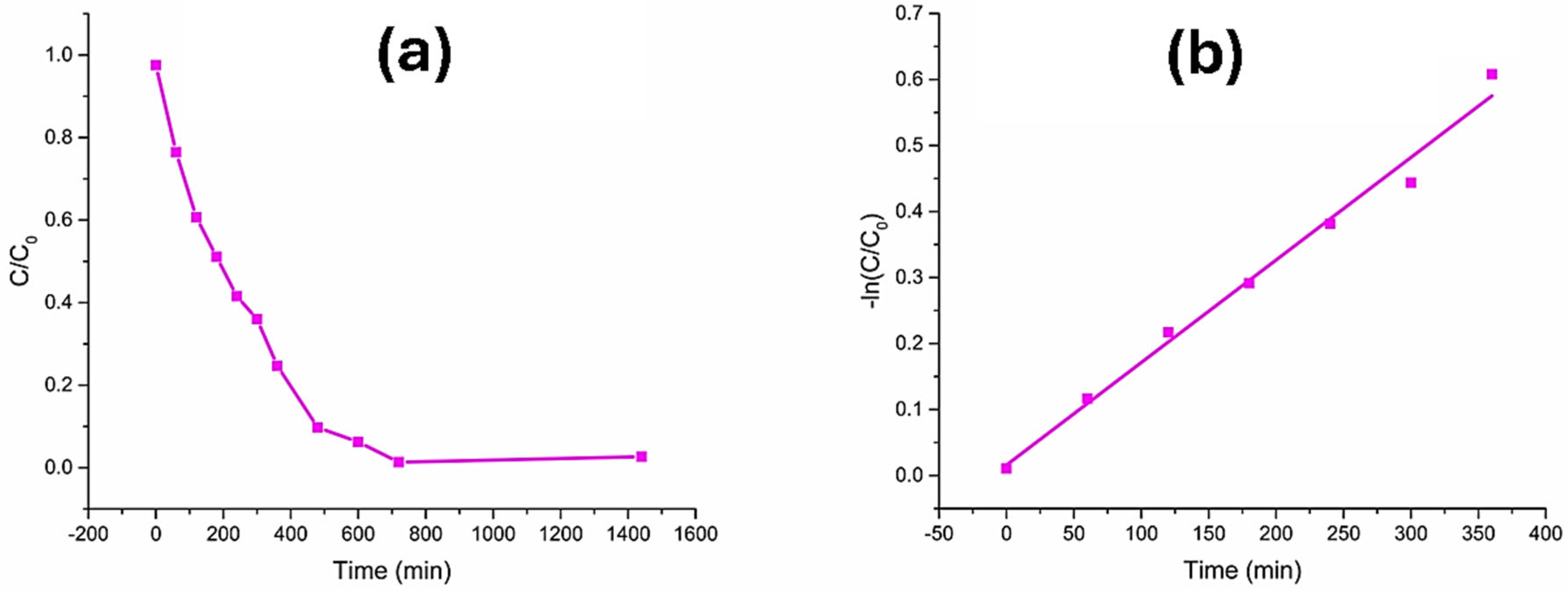

3.2. Degradation of Eriochrome Black T

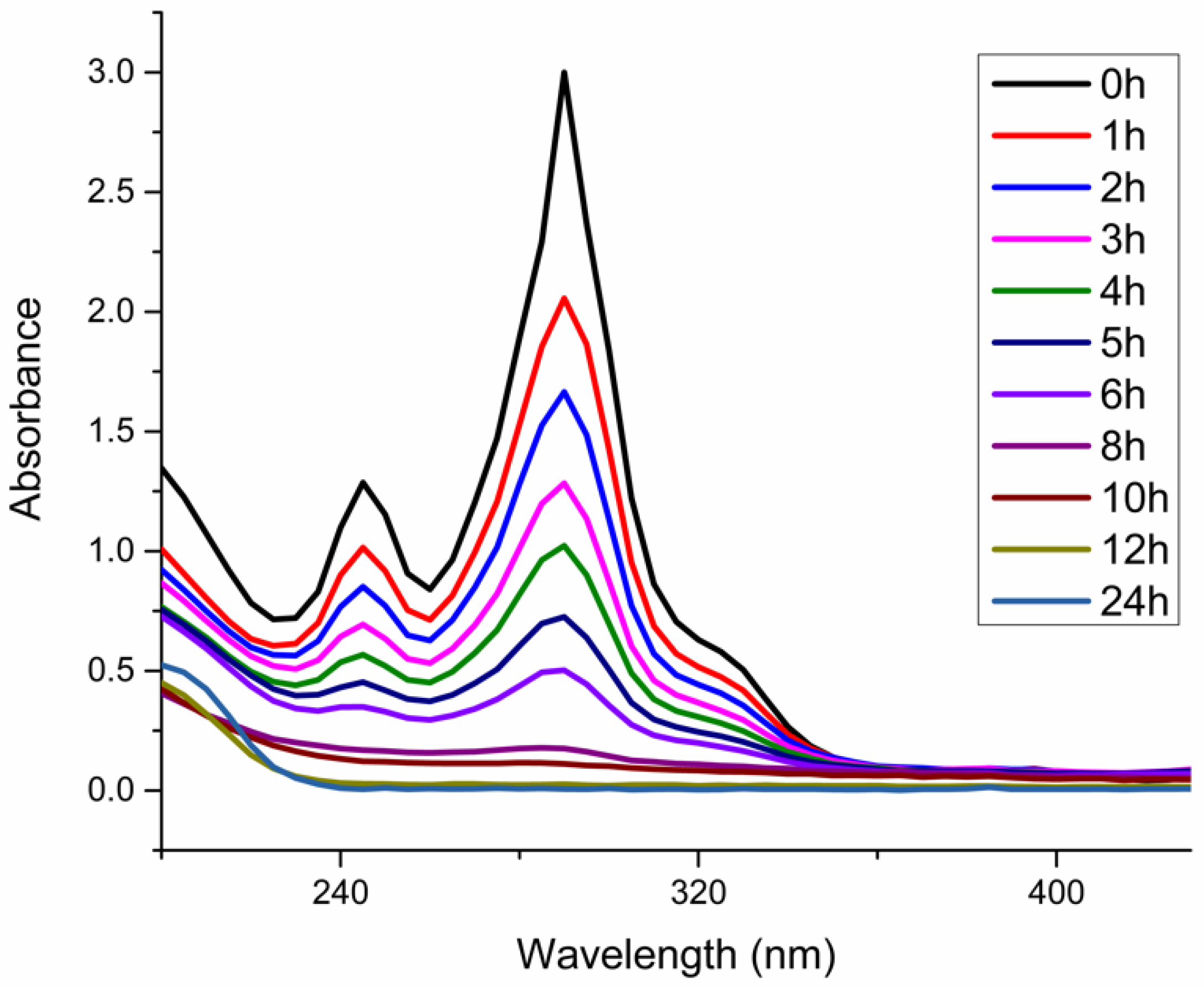

3.3. Methylene Blue Degradation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzain, H.; Kalimugogo, V.; Hussein, K. A Review of Environmental Impact of Azo Dyes. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2023, 10, 64–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.T. Azo dyes and human health: A review. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 2016, 34, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüschweiler, B.J.; Merlot, C. Azo dyes in clothing textiles can be cleaved into a series of mutagenic aromatic amines which are not regulated yet. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 88, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lellis, B.; Fávaro-Polonio, C.Z.; Pamphile, J.A.; Polonio, J.C. Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2019, 3, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheresan, V.; Kansedo, J.; Lau, S.Y. Efficiency of various recent wastewater dye removal methods: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4676–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngulube, T.; Gumbo, J.R.; Masindi, V.; Maity, A. An update on synthetic dyes adsorption onto clay based minerals: A state-of-art review. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 191, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, N.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Huo, S.; Cheng, P.; Peng, P.; Zhang, R.; et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using TiO2-based photocatalysts: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paździor, K.; Bilińska, L.; Ledakowicz, S. A review of the existing and emerging technologies in the combination of AOPs and biological processes in industrial textile wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 376, 120597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Song, X.; Zhang, P.; Huo, P.; Li, X. A review on heterogeneous photocatalysis for environmental remediation: From semiconductors to modification strategies. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 178–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E. Solar photoelectro-Fenton: A very effective and cost-efficient electrochemical advanced oxidation process for the removal of organic pollutants from synthetic and real wastewaters. Chemosphere 2023, 327, 138532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Samadi, M.; Pourjavadi, A.; Moshfegh, A.Z.; Ramakrishna, S. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-based photocatalysts for solar hydrogen generation: Recent advances and future development directions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 23406–23433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Keshu, N.; Shanker, U. Sunlight-induced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants by biosynthesized hetrometallic oxides nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 61760–61780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, A.C.R.; Devanadera, M.K.P.; Dedeles, G.R. Decolorization of Selected Synthetic Textile Dyes by Yeasts from Leaves and Fruit Peels. J. Health Pollut. 2016, 6, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solorio-Grajeda, D.; Torres-Pérez, J.; Medellín-Castillo, N.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy effect and acicular growth of copper structures on Titania-Silica fibers. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 150, 110484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malika, M.; Sonawane, S.S. Statistical modelling for the Ultrasonic photodegradation of Rhodamine B dye using aqueous based Bi-metal doped TiO2 supported montmorillonite hybrid nanofluid via RSM. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 44, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariani, R.S.; Esmaeili, A.; Mortezaali, A.; Dehghanpour, S. Photocatalytic reaction and degradation of methylene blue on TiO2 nano-sized particles. Optik 2016, 127, 7143–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xue, D.; Fang, H.; Tian, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Li, H. GO/TiO2 composites as a highly active photocatalyst for the degradation of methyl orange. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neon, M.H.K.; Islam, M.S. MoO3 and Ag co-synthesized TiO2 as a novel heterogeneous photocatalyst with enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity for methyl orange dye degradation. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 12, 100244. [Google Scholar]

- Sangareswari, M.; Meenakshi Sundaram, M. Development of efficiency improved polymer-modified TiO2 for the photocatalytic degradation of an organic dye from wastewater environment. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chkirida, S.; Zari, N.; Achour, R.; Qaiss, A.E.K.; Bouhfid, R. Efficient hybrid bionanocomposites based on iron-modified TiO2 for dye degradation via an adsorption-photocatalysis synergy under UV-Visible irradiations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 14018–14027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Mahanpoor, K.; Soodbar, D. Evaluation of a modified TiO2 (GO–B–TiO2) photo catalyst for degradation of 4-nitrophenol in petrochemical wastewater by response surface methodology based on the central composite design. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.M.; Osman, G.; Khairou, K.S. Fabrication of Ag nanoparticles modified TiO2–CNT heterostructures for enhanced visible light photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants and bacteria. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1847–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghchaure, R.H.; Koli, P.B.; Adole, V.A.; Jagdale, B.S. Exploration of photocatalytic performance of TiO2, 5% Ni/TiO2, and 5% Fe/TiO2 for degradation of eosine blue dye: Comparative study. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, S.; Prakash, N.T.; Prakash, R.; Pal, B. Improved degradation of methyl orange dye using bio-co-catalyst Se nanoparticles impregnated ZnS photocatalyst under UV irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 306, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamonti, L.; Predieri, G.; Paz, Y.; Fornasini, L.; Lottici, P.; Bondioli, F. Enhanced self-cleaning properties of N-doped TiO2 coating for Cultural Heritage. Microchem. J. 2017, 133, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balarabe, B.Y.; Paria, S.; Keita, D.S.; Baraze, A.R.I.; Kalugendo, E.; Tetteh, G.N.T.; Meringo, M.M.; Oumarou, M.N.I. Enhanced UV-light active α-Bi2O3 nanoparticles for the removal of methyl orange and ciprofloxacin. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 146, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, S.A.; Ribeiro, C. An insight toward the photocatalytic activity of S doped 1-D TiO2 nanorods prepared via novel route: As promising platform for environmental leap. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 412, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.K. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye using facilely synthesized α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Hassan, M.S.; Cho, H.S.; Polyakov, A.Y.; Khil, M.S.; Lee, I.H. Facile low-temperature synthesis of ZnO nanopyramid and its application to photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye under UV irradiation. Mater. Lett. 2014, 133, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Hassan, M.S.; Jang, L.W.; Yun, J.H.; Ahn, H.K.; Khil, M.S.; Lee, I.H. Low-temperature synthesis of ZnO quantum dots for photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye under UV irradiation. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 14827–14831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isai, K.A.; Shrivastava, V.S. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using ZnO and 2%Fe–ZnO semiconductor nanomaterials synthesized by sol–gel method: A comparative study. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Mengting, Z.; Fu, D.; Yeap, S.K.; Othman, M.H.D.; Avtar, R.; Ouyang, T. Functionalizing TiO2 with graphene oxide for enhancing photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB) in contaminated wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, M.A.; Shahid, S.; Javed, M.; Iqbal, S.; Sher, M.; Akbar, M.B. Highly efficient g-C3N4/Cr-ZnO nanocomposites with superior photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 401, 112776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Misra, S.K. Multifunctional Fe3O4-ZnO nanocomposites for environmental remediation applications. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2018, 10, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Dong, S.; Zhou, X.; Dong, S. N-doped carbon quantum dots/TiO2 hybrid composites with enhanced visible light driven photocatalytic activity toward dye wastewater degradation and mechanism insight. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2016, 325, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, S.A.; Byzynski, G.; Ribeiro, C. Synergistic effect on the photocatalytic activity of N-doped TiO2 nanorods synthesised by novel route with exposed (110) facet. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 666, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, Z.; Akbari, A.; Hosseini, H.A.; Khatami, M.; Darroudi, M. Egg white-mediated green synthesis of NiO nanoparticles and study of their cytotoxicity and photocatalytic activity. Polyhedron 2020, 178, 114351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madduri, S.B.; Kommalapati, R.R. Photocatalytic Degradation of Azo Dyes in Aqueous Solution Using TiO2 Doped with rGO/CdS under UV Irradiation. Processes 2024, 12, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutub, N.; Singh, P.; Sabir, S.; Sagadevan, S.; Oh, W. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of Acid Blue dye using CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinSabt, M.; Sagar, V.; Singh, J.; Rawat, M.; Shaban, M. Green synthesis of CS-TiO2 NPs for efficient photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. Polymers 2022, 14, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, A.R. Revisiting the optical bandgap of semiconductors and the proposal of a unified methodology to its determination. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollis, D.F. Kinetics of Photocatalyzed Reactions: Five Lessons Learned. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, J.; Chen, G. Study on the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in water using Ag/ZnO as catalyst by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization ion-trap mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 19, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiocchi, C.; Brussino, M.C.; Pramauro, E.; Prevot, A.B.; Palmisano, L.; Marcı̀, G. Characterization of methyl orange and its photocatalytic degradation products by HPLC/UV–VIS diode array and atmospheric pressure ionization quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2002, 214, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makota, O.; Dutková, E.; Briančin, J.; Bednarcik, J.; Lisnichuk, M.; Yevchuk, I.; Melnyk, I. Advanced photodegradation of azo dye methyl orange using H2O2-activated Fe3O4@ SiO2@ ZnO composite under UV treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, F.; Al-Hetlani, E.; Arafa, M.; Abdelmonem, Y.; Nazeer, A.A.; Amin, M.O.; Madkour, M. The effect of surface charge on photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using chargeable titania nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, K.M.; Kurny, A.; Gulshan, F. Parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation of dyes using TiO2: A review. Appl. Water Sci. 2015, 7, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ramírez, L.R.; Torres-Pérez, J.; Medellin-Castillo, N.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Photocatalytic degradation of oxytetracycline by SiO2–TiO2–Ag electrospun fibers. Solid State Sci. 2023, 140, 107188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, F.E.; Pelaz, G.; Morán, A.; Da Silva, J.C.G.E.; Cacciola, F.; Farissi, H.E.; Tayeq, H.; Zerrouk, M.H.; Brigui, J. Efficient Removal of Eriochrome Black T Dye Using Activated Carbon of Waste Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Grown in Northern Morocco Enhanced by New Mathematical Models. Separations 2022, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibowski, S.; Wiśniewska, M.; Wawarzkiewicz, M.; Hubicki, Z.; Goncharuk, O. Electrokinetic properties of silica-titania mixed oxide particles dispersed in aqueous solution of C.I. Direct Yellow 142 dye—Effects of surfactant and electrolyte presence. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2020, 56, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamzeb, M.; Tullah, M.; Ali, S.; Ihsanullah, N.; Khan, B.; Setzer, W.N.; Al-Zaqri, N.; Ibrahim, M.N.M. Kinetic, Thermodynamic and Adsorption Isotherm Studies of Detoxification of Eriochrome Black T Dye from Wastewater by Native and Washed Garlic Peel. Water 2022, 14, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghchaure, R.H.; Adole, V.A.; Jagdale, B.S. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue, rhodamine B, methyl orange and Eriochrome black T dyes by modified ZnO nanocatalysts: A concise review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 143, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Tan, H.; Liu, K.; Gao, W. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic property of novel ZnO/bone char composite. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 102, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevic, Z.Z.; Dojcinovic, M.P.; Vujancevic, J.D.; Jankovic-Castvan, I.; Ognjanovic, M.; Tadic, N.B.; Stojadinovic, S.; Brankovic, G.O.; Nikolic, M.V. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under natural sunlight using iron titanate nanoparticles prepared by a modified sol–gel method. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfa, M.; Afif, H.A.; Saraswati, T.E.; Bahruji, H. Fast Removal of Methylene Blue via Adsorption-Photodegradation on TiO2/SBA-15 Synthesized by Slow Calcination. Materials 2022, 15, 5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic Dye Degradation from Textile Wastewater: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21751–21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samia, N.; Usman, M.; Osman, A.I.; Khan, K.I.; Saeed, F.; Zeng, Y.; Motola, M.; Dai, H. Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants Using Fibrous Silica Titania and Ti3AlC2 Catalysts for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 17500–17515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.H.; Aslam, I.; Shuaib, A.; Anam, H.S.; Rizwan, M.; Kanwal, Q. Band gap engineering for improved photocatalytic performance of CuS/TiO2 composites under solar light irradiation. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2019, 33, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J. Heterogeneous photocatalysis: Fundamentals and applications to the removal of various types of aqueous pollutants. Catal. Today 1999, 53, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Holguín, P.N.; Garibay-Alvarado, J.A.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Silver nanoparticles: Multifunctional tool in environmental water remediation. Materials 2024, 17, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldama-Huerta, O.A.; Medellín-Castillo, N.A.; Carrasco Marín, F.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange, Eriochrome Black T, and Methylene Blue by Silica–Titania Fibers. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212084

Aldama-Huerta OA, Medellín-Castillo NA, Carrasco Marín F, Reyes-López SY. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange, Eriochrome Black T, and Methylene Blue by Silica–Titania Fibers. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212084

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldama-Huerta, Omar Arturo, Nahum A. Medellín-Castillo, Francisco Carrasco Marín, and Simón Yobanny Reyes-López. 2025. "Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange, Eriochrome Black T, and Methylene Blue by Silica–Titania Fibers" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212084

APA StyleAldama-Huerta, O. A., Medellín-Castillo, N. A., Carrasco Marín, F., & Reyes-López, S. Y. (2025). Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange, Eriochrome Black T, and Methylene Blue by Silica–Titania Fibers. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212084