Tetracenomycin Aglycones Primarily Inhibit Cell Growth and Proliferation in Mammalian Cancer Cell Lines

Abstract

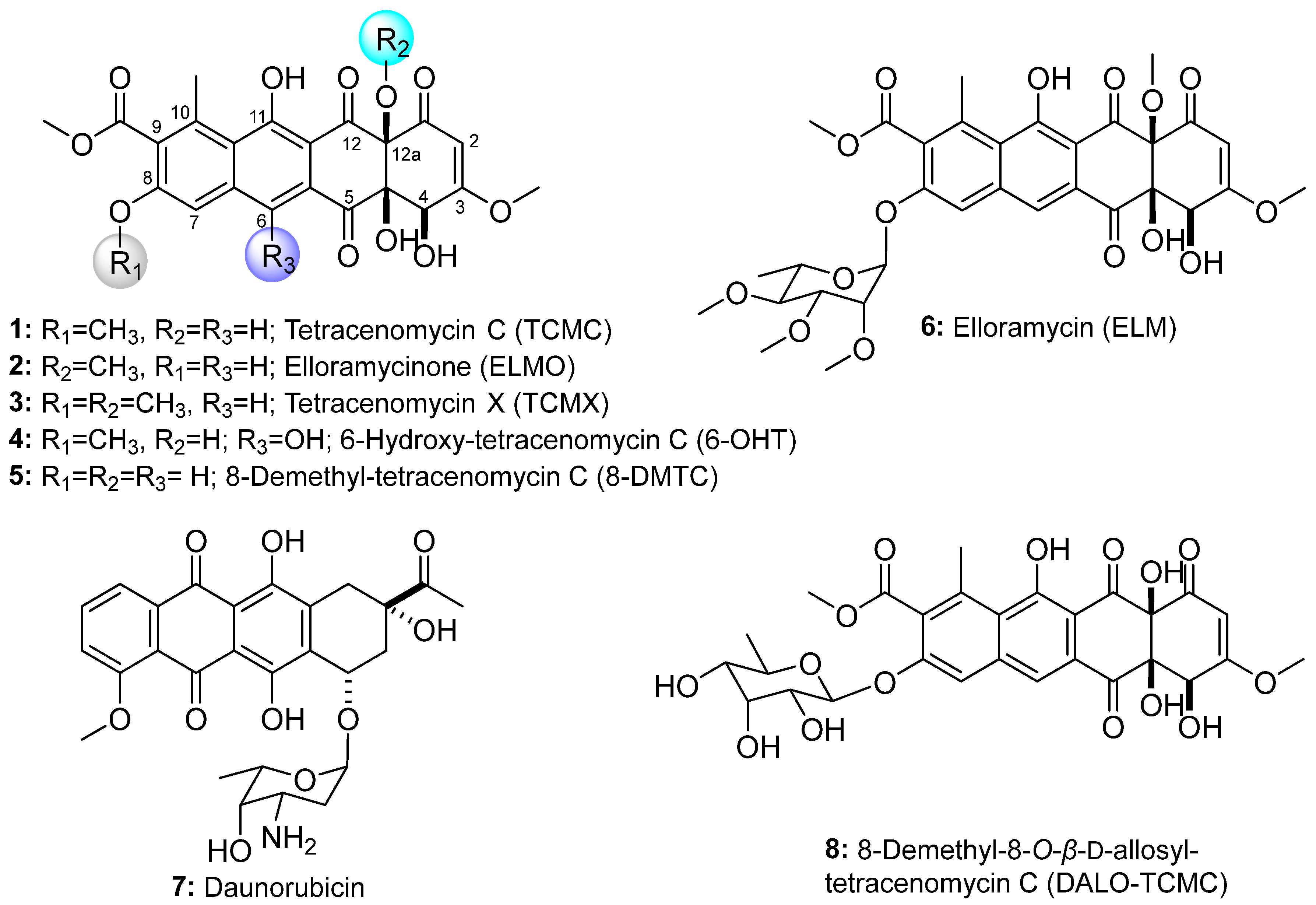

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

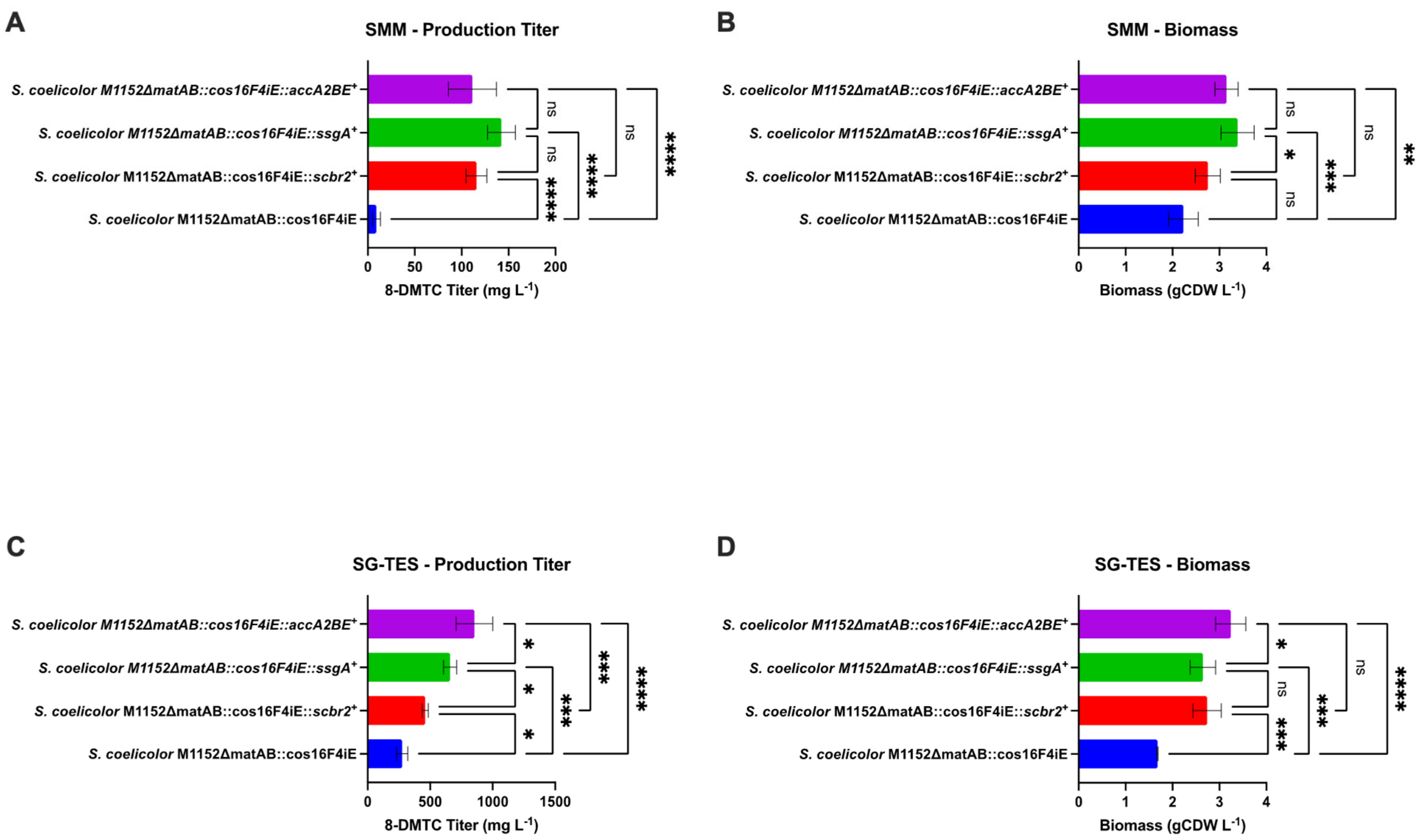

3.1. Metabolic Engineering of 8-Demethyl-Tetracenomycin C Production

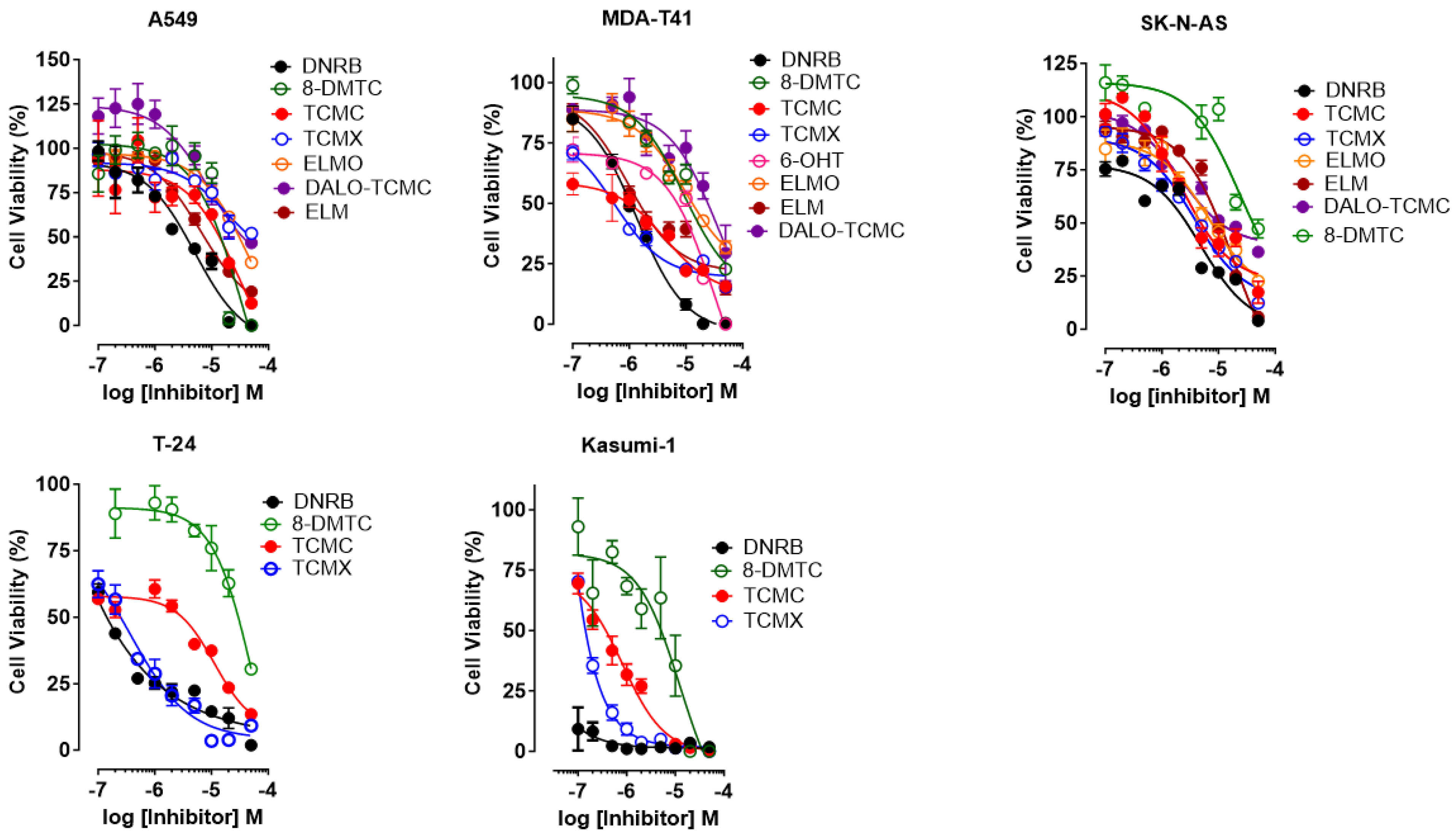

3.2. Cell Viability Assay

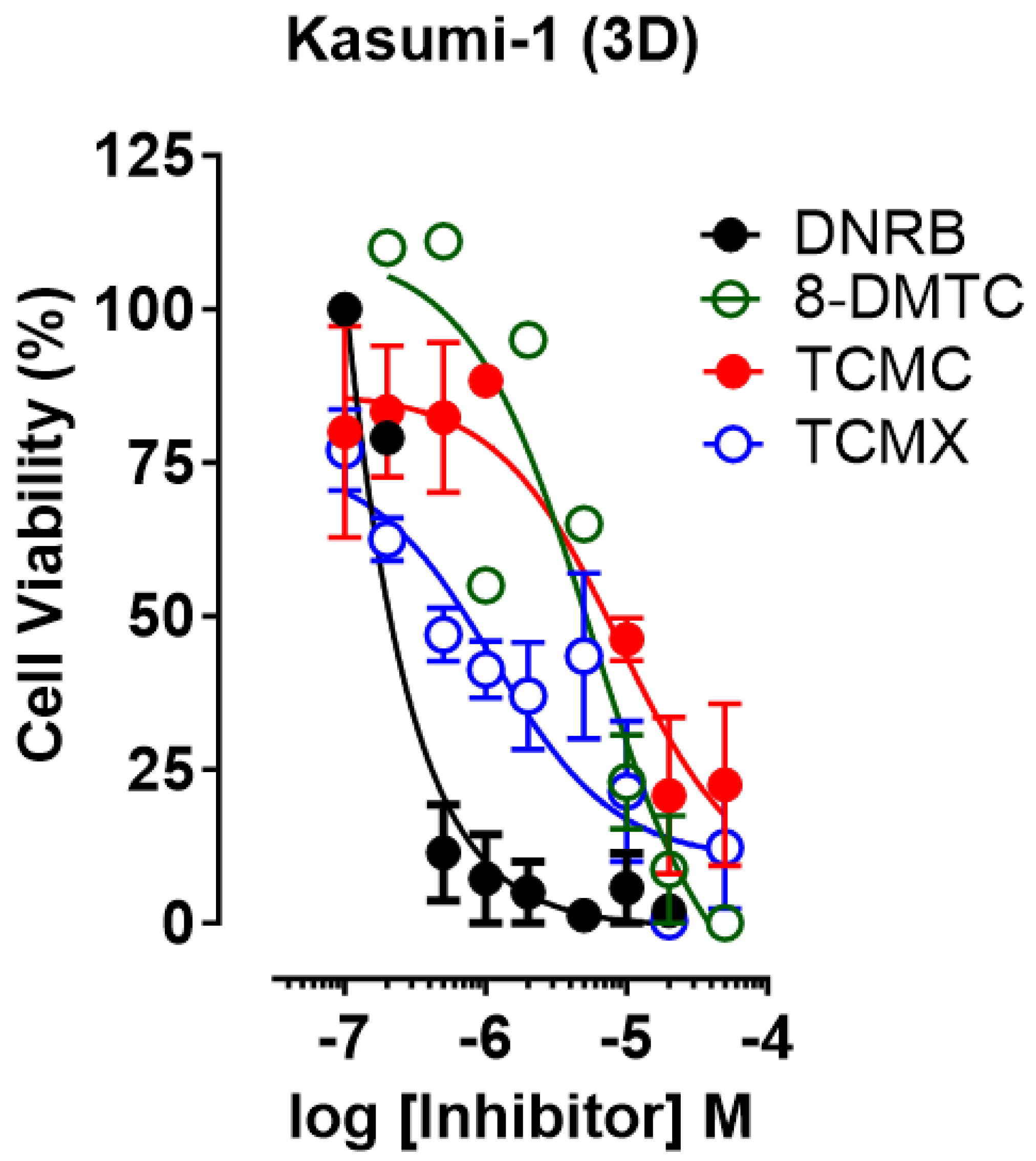

3.3. D Cell Viability Assay

3.4. Colony Forming Assay

3.5. Apoptosis Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weber, W.; Zähner, H.; Siebers, J.; Schröder, K.; Zeeck, A. Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen. 175. Mitteilung. Tetracenomycin C. Arch. Microbiol. 1979, 121, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egert, E.; Noltemeyer, M.; Siebers, J.; Rohr, J.; Zeeck, A. The Structure of Tetracenomycin C. J. Antibiot. 2012, 45, 1190–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohr, J.; Zeeck, A. Structure-Activity Relationships of Elloramycin and Tetracenomycin C. J. Antibiot. 1990, 43, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, H.P.; Rohr, J.; Zeeck, A. Elloramycins B, C, D, E and F: Minor Congeners of the Elloramycin Producer Streptomyces Olivaceus. J. Antibiot. 1986, 39, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeeck, A.; Reuschenbach, P.; Zähner, H.; Rohr, J. Metabolic Products of Microorganisms. 225 Elloramycin, a New Anthracycline-like Antibiotic from Streptomyces Olivaceus Isolation, Characterization, Structure and Biological Properties. J. Antibiot. 1985, 38, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, H.; Wendt-Pienkowski, E.; Hutchinson, C.R. Isolation of Tetracenomycin C-Nonproducing Streptomyces Glaucescens Mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1986, 167, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, G.; Patallo, E.P.; Braña, A.F.; Trefzer, A.; Bechthold, A.; Rohr, J.; Méndez, C.; Salas, J.A. Identification of a Sugar Flexible Glycosyltransferase from Streptomyces Olivaceus, the Producer of the Antitumor Polyketide Elloramycin. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, H.; Haag, S. Cloning and Characterization of a Polyketide Synthase Gene from Streptomyces Fradiae Tü2717, Which Carries the Genes for Biosynthesis of the Angucycline Antibiotic Urdamycin A and a Gene Probably Involved in Its Oxygenation. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 6126–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Osterman, I.A.; Wieland, M.; Maviza, T.P.; Lashkevich, K.A.; Lukianov, D.A.; Komarova, E.S.; Zakalyukina, Y.V.; Buschauer, R.; Shiriaev, D.I.; Leyn, S.A.; et al. Tetracenomycin X Inhibits Translation by Binding within the Ribosomal Exit Tunnel. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.C.; Perry, T.N.; Renault, T.T.; Innis, C.A. Tetracenomycin X Sequesters Peptidyl-TRNA during Translation of QK Motifs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkkonen, H.; Brown, K.V.; Niemczura, M.; Faudemer, Z.; Brown, C.; Ponomareva, L.V.; Helmy, Y.A.; Thorson, J.S.; Nybo, S.E.; Metsä-Ketelä, M.; et al. Engineering BioBricks for Deoxysugar Biosynthesis and Generation of New Tetracenomycins. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 21237–21253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Woodbury, NY, USA, 2001; p. 999. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, D.J.; Gewain, K.M.; Ruby, C.L.; Dezeny, G.; Gibbons, P.H.; MacNeil, T. Analysis of Streptomyces Avermitilis Genes Required for Avermectin Biosynthesis Utilizing a Novel Integration Vector. Gene 1992, 111, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieser, T.; Bibb, M.J.; Buttner, M.J.; Chater, K.F.; Hopwood, D.A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics; John Innes Centre Ltd.: Norwich, UK, 2000; p. 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybo, S.E.; Shabaan, K.A.; Kharel, M.K.; Sutardjo, H.; Salas, J.A.; Méndez, C.; Rohr, J. Ketoolivosyl-Tetracenomycin C: A New Ketosugar Bearing Tetracenomycin Reveals New Insight into the Substrate Flexibility of Glycosyltransferase ElmGT. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2247–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.T.; Riebschleger, K.K.; Brown, K.V.; Gorgijevska, N.M.; Nybo, S.E. A BioBricks Toolbox for Metabolic Engineering of the Tetracenomycin Pathway. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 17, 2100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazodier, P.; Petter, R.; Thompson, C. Intergeneric Conjugation between Escherichia Coli and Streptomyces Species. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 3583–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku, R.A.; Jones, K.J.; Van Baren, M.; Alan, J.K.; Amissah, F. Diclofenac Enhances Docosahexaenoic Acid-Induced Apoptosis in Vitro in Lung Cancer Cells. Cancers 2020, 12, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku, R.; Amissah, F.; Alan, J.K. PI3K Functions Downstream of Cdc42 to Drive Cancer Phenotypes in a Melanoma Cell Line. Small GTPases 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Seidel, C.; Ebner, R.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A. Spheroid-Based Drug Screen: Considerations and Practical Approach. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Gan, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Shang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, S. Tetracenomycin X Exerts Antitumour Activity in Lung Cancer Cells through the Downregulation of Cyclin D1. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asong, G.M.; Amissah, F.; Voshavar, C.; Nkembo, A.T.; Ntantie, E.; Lamango, N.S.; Ablordeppey, S.Y. A Mechanistic Investigation on the Anticancer Properties of SYA013, a Homopiperazine Analogue of Haloperidol with Activity against Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 32907–32918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.T.; Khosla, C. Combinatorial Biosynthesis of Polyketides—A Perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J. Modelling the Morphology of Filamentous Microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dissel, D.; Willemse, J.; Zacchetti, B.; Claessen, D.; Pier, G.B.; van Wezel, G.P. Production of Poly-β-1,6-N-Acetylglucosamine by MatAB Is Required for Hyphal Aggregation and Hydrophilic Surface Adhesion by Streptomyces. Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wezel, G.P.; Krabben, P.; Traag, B.A.; Keijser, B.J.F.; Kerste, R.; Vijgenboom, E.; Heijnen, J.J.; Kraal, B. Unlocking Streptomyces Spp. for Use as Sustainable Industrial Production Platforms by Morphological Engineering. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5283–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noens, E.E.E.; Mersinias, V.; Traag, B.A.; Smith, C.P.; Koerten, H.K.; Van Wezel, G.P. SsgA-like Proteins Determine the Fate of Peptidoglycan during Sporulation of Streptomyces Coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 929–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Ji, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, K. ScbR-and ScbR2-Mediated Signal Transduction Networks Coordinate Complex Physiological Responses in Streptomyces Coelicolor. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dissel, D.; Claessen, D.; Roth, M.; van Wezel, G.P. A Novel Locus for Mycelial Aggregation Forms a Gateway to Improved Streptomyces Cell Factories. Microb. Cell Fact. 2015, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, L.; Vijgenboom, E.; van Wezel, G.P.; Díaz, M.; Santamaría, R.I. New Approaches to Achieve High Level Enzyme Production in Streptomyces Lividans. Microb. Cell Fact. 2016, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Tian, X.; Yang, H.; Fan, K.; Yang, K.; Tan, H. “Pseudo” γ-Butyrolactone Receptors Respond to Antibiotic Signals to Coordinate Antibiotic Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 27440–27448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ji, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Pan, G.; Fan, K.; Yang, K. Angucyclines as Signals Modulate the Behaviors of Streptomyces Coelicolor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5688–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Escribano, J.P.; Bibb, M.J. Engineering Streptomyces Coelicolor for Heterologous Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulheim, S.; Kumelj, T.; van Dissel, D.; Salehzadeh-Yazdi, A.; Du, C.; van Wezel, G.P.; Nieselt, K.; Almaas, E.; Wentzel, A.; Kerkhoven, E.J. Enzyme-Constrained Models and Omics Analysis of Streptomyces Coelicolor Reveal Metabolic Changes That Enhance Heterologous Production. iScience 2020, 23, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumelj, T.S.; Sulheim, S.; Wentzel, A.; Almaas, E. Predicting Strain Engineering Strategies Using IKS1317: A Genome-Scale Metabolic Model of Streptomyces Coelicolor. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 14, 1800180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, Y.G.; Butler, M.J.; Chater, K.F.; Lee, K.J. Engineering of Primary Carbohydrate Metabolism for Increased Production of Actinorhodin in Streptomyces Codicolor. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7132–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, J.; Chen, M.; Hao, X.; Cao, F.; Tan, Y.; Ping, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Gan, M. Seco-Tetracenomycins from the Marine-Derived Actinomycete Saccharothrix Sp. 10-10. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.; Liu, B.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; He, H.; Ping, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C. Saccharothrixones A-D, Tetracenomycin-Type Polyketides from the Marine-Derived Actinomycete Saccharothrix Sp. 10-10. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2260–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Nji Wandi, B.; Schwartz, N.; Hecht, J.; Ponomareva, L.; Paige, K.; West, A.; Desanti, K.; Nguyen, J.; Niemi, J.; et al. Diverse Combinatorial Biosynthesis Strategies for C–H Functionalization of Anthracyclinones. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1523–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Nguyen, J.; Hecht, J.; Schwartz, N.; Brown, K.V.; Ponomareva, L.V.; Niemczura, M.; Van Dissel, D.; Van Wezel, G.P.; Thorson, J.S.; et al. A BioBricks Metabolic Engineering Platform for the Biosynthesis of Anthracyclinones in Streptomyces Coelicolor. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 4193–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, C.; Pernodet, J.L.; Lautru, S. Modular and integrative vectors for synthetic biology applications in Streptomyces spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, F.; Mersinias, V.; Smith, C.P. High efficiency intergeneric conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to methyl DNA-restricting Streptomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1997, 155, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | A549 | MDA-T41 | SK-NAS | T-41 | Kasumi-1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Max. Inhibition | IC50 μM | % Max. Inhibition | IC50 μM | % Max. Inhibition | IC50 μM | % Max. Inhibition | IC50 μM | % Max. Inhibition | IC50 μM | |

| DNRB | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 99.5 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 96.0 ± 2.5 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 98.2 ± 0.8 | 0.002 ± 0.0 | 98.2 ± 0.8 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| TCMC | 87.5 ± 1.4 | 26.4 ± 4.5 | 84.3 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 2.2 | 82.6 ± 5.1 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 86.5 ± 1.3 | 12.3 ± 2.5 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 0.82 ± 0.1 |

| TCMX | 48.0 ± 2.9 | 19.7 ±5.3 | 84.6 ± 1.5 | 0.54 ±0.3 | 87.6 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 90.7 ± 1.2 | 0.36 ± 0.4 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 0.09 ± 0.0 |

| 8-DMTC | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 37.5 ± 7.4 | 77.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 3.1 | 52.8 ± 4.3 | 23.4 ± 6.4 | 69.3 ± 2.0 | 60.4 ± 7.5 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 12.5 ± 2.1 |

| 6-OHT | - | - | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ELMO | 64.4 ± 2.2 | 44.6 ± 6.7 | 68.2 ± 2.5 | 9.7 ± 3.6 | 77.6 ± 2.7 | 6.6 ± 2.4 | - | - | - | - |

| ELM | 81.0 ± 2.6 | 6.5 ± 2.2 | 85.4 ± 2.5 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 94.2 ± 1.8 | 18.3 ± 6.2 | - | - | - | - |

| DALO-TCMC | 53.4 ± 2.9 | 8.8 ± 2.9 | 70.5 ± 11.5 | 37.9 ± 4.8 | 63.6 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Birdsall, K.; Brako, A.B.S.; Brown, C.; Paige, K.; West, A.; Schwartz, N.; Hecht, J.; Brown, K.V.; Thorson, J.S.; Shaaban, K.A.; et al. Tetracenomycin Aglycones Primarily Inhibit Cell Growth and Proliferation in Mammalian Cancer Cell Lines. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11985. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211985

Birdsall K, Brako ABS, Brown C, Paige K, West A, Schwartz N, Hecht J, Brown KV, Thorson JS, Shaaban KA, et al. Tetracenomycin Aglycones Primarily Inhibit Cell Growth and Proliferation in Mammalian Cancer Cell Lines. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11985. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211985

Chicago/Turabian StyleBirdsall, Kyah, Adwowa B. S. Brako, Courtney Brown, Kendall Paige, Alexis West, Nora Schwartz, Jacob Hecht, Katelyn V. Brown, Jon S. Thorson, Khaled A. Shaaban, and et al. 2025. "Tetracenomycin Aglycones Primarily Inhibit Cell Growth and Proliferation in Mammalian Cancer Cell Lines" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11985. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211985

APA StyleBirdsall, K., Brako, A. B. S., Brown, C., Paige, K., West, A., Schwartz, N., Hecht, J., Brown, K. V., Thorson, J. S., Shaaban, K. A., & Nybo, S. E. (2025). Tetracenomycin Aglycones Primarily Inhibit Cell Growth and Proliferation in Mammalian Cancer Cell Lines. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11985. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211985