1. Introduction

The influence of programming languages on antivirus evasion is a critical area of study in malware research [

1]. Different languages offer varying degrees of control over system resources, which attackers leverage to bypass antivirus detection. Low-level languages such as C, C++, and Assembly allow for precise memory manipulation and direct interaction with the operating system [

2], facilitating techniques such as packing [

3], obfuscation [

4], and polymorphism [

5,

6]. These methods effectively evade traditional signature-based detection, as they manipulate the structure of the executable, making it harder for antivirus software to recognize [

7].

Recent trends in malware development include the use of multi-language attacks, where different components of the malware are written in various languages such as Go and Rust. As malware developers explore the strengths and weaknesses of various programming languages, the interplay between language choice and antivirus evasion strategies remains a critical area of ongoing research. Understanding these dynamics is essential for advancing both offensive and defensive cybersecurity measures, as well as for developing more resilient antivirus solutions capable of countering increasingly complex threats.

The impact of programming languages on antivirus evasion is crucial for understanding the current trends and predicting future developments in malware. As languages evolve, so do the tactics employed by attackers, necessitating continuous research into the potential malicious exploitation of these languages. The need for advanced detection systems incorporating behavioral analysis and machine learning becomes increasingly apparent as malware grows more sophisticated and linguistically diverse [

8]. This research aimed to bridge the knowledge gap by examining how different programming languages affect malware’s evasion capabilities and exploring the implications for the future of cybersecurity.

The principal contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

Cross-language, cross-compiler measurement. We conduct a controlled, functionally equivalent implementation of canonical in-memory shellcode loaders across multiple languages (e.g., C, C#, Fortran, and COBOL) and compiler/linker configurations, keeping the payload and loader logic fixed to isolate the effect of language and toolchain choices.

Generalizable detection signals. We identify language-agnostic behavioral cues—API-call sequences, memory-protection transitions (VirtualAlloc → VirtualProtect), thread-spawn patterns—and demonstrate their relationship to typical AV detection points.

Actionable guidance for anti-virus. We analyze failure modes that arise with legacy or non-mainstream toolchains and outline practical hardening guidelines, including language-aware binary normalization and behavior-centric triage that reduces dependence on byte-patterns.

Reproducible baseline. We provide a reproducible build recipe and evaluation protocol that can serve as a reference baseline for future studies incorporating packers, encoders, or evasive techniques.

This work is academic and defensive research only. All studies use inert payload simulators to recreate allocation–copy–protection–dispatch semantics without network or file I/O in offline, isolated contexts. Instead of executable binaries or weaponizable payloads, exploits, packers, or obfuscation, build recipes, metadata, and aggregate results are employed for qualified replication. Laws, institutional regulations, and responsible research standards are followed in the study. To exploit these concepts or artifacts for offensive or illegal purposes is strictly banned. Readers must ensure ethical, legal use in their areas and organizations.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews prior work on shellcode detection, language-aware malware analysis, and behavioral models for in-memory execution.

Section 3 details our experimental design and the implementation of functionally equivalent loaders across languages, together with the compiler/linker matrix.

Section 4 describes the scanning protocol, metrics, and statistical methods.

Section 5 reports the empirical results and answers the research questions.

Section 6 discusses implications, limitations, and threats to validity concludes the paper and outlines directions for the future work.

2. Related Work

In the realm of antivirus evasion, programming languages play a pivotal role in shaping malware’s characteristics and its ability to bypass detection systems. Traditionally, malware has been written in low-level languages such as C and C++ due to their direct access to system resources [

9,

10], allowing attackers to exploit memory management and hardware manipulation. These languages provide a high degree of control over the executable’s structure, enabling techniques such as packing, polymorphism, and self-modifying code, all of which are designed to evade static signature-based detection by antivirus engines [

11]. In particular, malware written in these languages often utilizes advanced obfuscation methods to thwart reverse engineering and evade heuristic analysis.

More recently, high-level languages such as Python, Java, and C# have also come to play a significant role in antivirus evasion, albeit through different mechanisms. While these languages abstract much of the low-level memory management, they provide powerful libraries and frameworks that can be used to dynamically load and execute code at runtime [

12]. For instance, the researchers have demonstrated the use of Python to evade antivirus detection without relying on obfuscation techniques [

13]. Python-based malware can evade antivirus detection through various methods, including encryption, compression, and the use of packers such as PyInstaller [

14,

15]. Research indicates that, when Python is combined with these evasion mechanisms and incorporates obfuscation techniques, it poses a significant challenge to dynamic analysis engines, particularly in evading runtime detection. Further advanced obfuscation strategies have also been explored, such as utilizing fountain codes to fragment payloads [

16] or applying chaotic-based encryption to randomize shellcode [

17].

Programming languages such as Rust have begun to attract attention in the context of antivirus evasion. Rust’s memory safety features, combined with its ability to generate efficient binaries, make it more challenging for antivirus systems to perform reverse engineering and detect malicious behavior [

18]. Studies have demonstrated that malware written in Rust tends to evade detection more effectively than C-based malware, highlighting the limitations of current antivirus tools in analyzing newer languages [

19]. This emphasizes the need for antivirus systems to evolve, integrating more advanced detection mechanisms such as behavioral monitoring and machine learning to address the increasing diversity of malware development languages [

20].

Cybercriminals are increasingly leveraging Microsoft’s .NET and PowerShell frameworks to develop sophisticated malware [

21]. These powerful tools make it easier to develop ransomware and targeted attacks, presenting significant challenges for defenders. The rapid development cycles and high-level programming environments associated with these frameworks underscore the need for greater and continuous attention in combating these evolving threats [

22].

Advanced threat groups, such as APT28 (Fancy Bear) and APT29 (Cozy Bear) [

23], have shifted to using more obscure programming languages such as Go and Rust in their malware to enhance evasion [

24]. Go, in particular has become a favorite in advanced persistent threats (APTs) due to its cross-platform compatibility and the difficulty it presents for reverse engineering. For instance, APT28 used Go to rewrite its Zebrocy malware, previously built in Delphi [

25], while APT29 deployed Go in its WellMess malware to target both Windows and Linux systems. The WellMess malware even added capabilities such as running PowerShell scripts post-infection [

24]. These adaptations significantly sidestep traditional antivirus detection methods, emphasizing the need for more advanced security solutions.

According to the TIOBE index in 2024, Python is the most popular programming language [

26], followed by C++, Java, and C. This ranking reflects current trends in the software development industry, with Python’s versatility, simplicity, and widespread use in fields such as data science, web development, and automation contributing to its top position. Other languages such as Go and Rust are also gaining traction, indicating a growing interest in modern, efficient, and performance-oriented languages. In light of these trends and concerns, we propose an experiment focusing on shellcode loaders without any obfuscation, encryption, or encoding. This approach aims to provide a baseline understanding of how different programming languages, both modern and legacy, interact with antivirus systems in their most basic form. To provide a clear overview of the discussed literature as

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis summarizing the influence of these language families on malware evasion.

3. Methodology

We implement functionally equivalent loaders in C, C#, Fortran, and COBOL to compare their antivirus detection outcomes under a fixed in-memory execution semantics [

27]. To avoid distributing weaponizable artifacts, we use a benign inert payload emulator that exercises the same memory-allocation, copying, permission-transition, and thread-creation primitives as a typical loader, but performs no network or file I/O. This design preserves detection-relevant behavior while eliminating exploit content. All builds are produced with pinned toolchains and deterministic settings where available.

msfvenom -p windows/x64/meterpreter/reverse_tcp LHOST=<IP> LPORT=<PORT> -f c

This command utilizes msfvenom, a payload generator from the Metasploit Framework, to create a Meterpreter reverse shell payload for Windows in C. A reverse shell is a cybersecurity technique where a compromised system initiates a connection back to an attacker’s machine [

28,

29]. This approach allows the attacker to remotely execute commands on the compromised system. Once the payload is executed on the target machine, it initiates a connection back to the attacker’s system. This connection provides remote access to the compromised machine, allowing the attacker to interact with it as if they had access.

On Windows operating systems, shellcode is typically executed by allocating memory, copying the shellcode into that memory, and then marking it as executable before jumping to it. This process often involves using Windows API functions such as

VirtualAlloc to allocate memory,

RtlMoveMemory or

memcpy to copy the shellcode, and

CreateThread or direct function pointers to execute it. The first step in executing shellcode on Windows is allocating a block of memory that can hold the shellcode. This is performed using the

VirtualAlloc function, which reserves or commits a region of pages in the virtual address space of the calling process [

30]. The memory must be allocated with the

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, instead of 0x40, flag to ensure that the memory is executable after writing the shellcode. Once the memory is allocated, the shellcode is copied into this allocated space using functions such as

RtlMoveMemory or

memcpy [

31]. These functions move the bytes of shellcode from one memory location (likely the shellcode stored as a byte array in the program) to the newly allocated executable memory. If the memory was initially allocated with read/write permissions, it needs to be changed to executable memory using

VirtualProtect [

32]. This function changes the protection of the allocated memory, allowing the system to execute code stored in that region. After the memory is marked as executable, the final step is to execute the shellcode. This is commonly achieved by either creating a new thread with

CreateThread that starts executing at the location of the shellcode or by casting the shellcode’s memory address to a function pointer and invoking it directly. After creating a thread with

CreateThread, the function

WaitForSingleObject is used to wait for the thread to finish. It ensures that the main program pauses until the shellcode execution is complete. The function takes the thread handle and

INFINITE as arguments to wait indefinitely until the thread finishes.

All binaries are built in isolated VM (Virtual Machine) with pinned compilers/linkers; we record toolchain versions, options, and PE/CLR metadata hashes. Specifically, all build and execution tasks were conducted within a VMware Workstation 17.6.3 virtual machine running a 64-bit Windows 10 Professional guest OS. To create the isolated sandbox, the VM’s network was configured to a host-only (internal) setting. This setup permitted VM-to-VM communication (required for the inert payload’s C2 simulation) but strictly disabled all external file, registry, and network egress, preventing any external I/O.

4. Experiment

This section reports the cross-language scanning results and the associated analysis. To isolate the effect of language and toolchain choices, all artifacts implement a functionally equivalent in-memory dispatch path while holding execution semantics constant (allocation → copy → protection transition → dispatch). For safety and reproducibility, we use a benign inert payload emulator that exercises the same Windows API primitives but performs no network or file I/O. This preserves detection-relevant behavior without distributing weaponizable content. All binaries are scanned on

https://kleenscan.com/, which aggregates reporting from 30+ engines. We compare per-artifact outcomes without sharing files with third parties. Unless otherwise noted, no packing, encoding, or obfuscation is applied.

4.1. Artifacts and Build Matrix

We consider four languages and their representative toolchains:

C (native): Visual Studio 2022, Release, static and dynamic CRT variants; deterministic build enabled when available.

C# (.NET 6.0): Visual Studio 2022, Release, AnyCPU/x64, single-file publish off; P/Invoke used only for required Win32 APIs.

Fortran (native): Intel® Fortran Compiler integrated with MSVC; Release profile; native linkage.

COBOL (native): GnuCOBOL via MSYS2 for Windows; Release-equivalent flags; native calls to Win32.

Each artifact conforms to a shared equivalence oracle: (i) presence of the canonical API sequence; (ii) RW→RX protection transition (no RWX pages); (iii) absence of file/registry/network side effects. We record compiler/linker versions, selected flags, PE/CLR metadata, import table shape, section sizes, and content hashes.

To visually represent the shared logic across all loaders,

Figure 1 illustrates the canonical flowchart implemented in all four languages.

4.2. Programming C Language

As shown in Listing 1, the source codes in the C programming language were compiled using Visual Studio 2022 in release mode, and the Run-Time Library was set with

and without

debug symbols [

33].

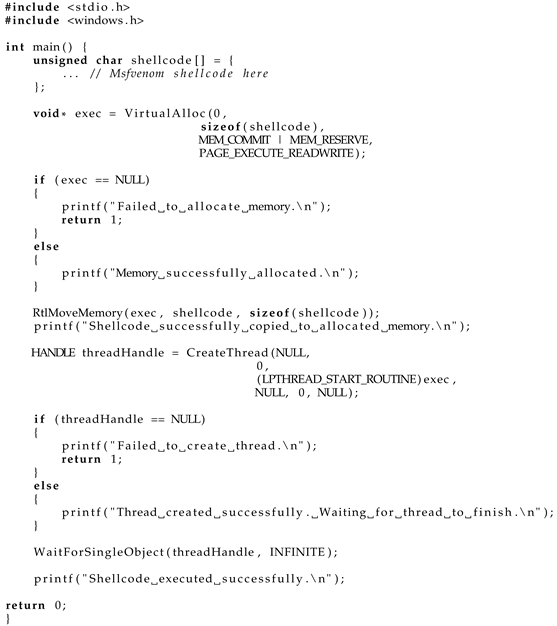

| Listing 1. Executing the shellcode in the C programming language. |

![Applsci 15 11862 i001 Applsci 15 11862 i001]() |

4.3. C# Programming Language

As shown in Listing 2, the source codes in the C# programming language were compiled using Visual Studio 2022 in release mode and using .NET 6.0, without debug symbols.

4.4. FORTRAN Programming Language

As shown in Listing 3, the source codes in the Fortran programming language were compiled using an Intel® Fortran Compiler [

34]; this compiler can be used with Microsoft Visual Studio 2019 and 2022. Fortran is primarily used in scientific computing, numerical analysis, and engineering applications [

35]. It is favored for tasks that require high-performance computations, such as simulations, complex mathematical modeling, weather forecasting, computational fluid dynamics, and large-scale data processing. Its strength lies in handling large arrays and matrices efficiently, making it a common choice in physics, chemistry, and engineering research.

| Listing 2. Executing the shellcode in the C# programming language. |

![Applsci 15 11862 i002 Applsci 15 11862 i002]() |

4.5. COBOL Programming Language

As shown in Listing 4, the source codes in the COBOL programming language were compiled using GnuCobol (version 1 3.2-9) with MSYS2. COBOL (Common Business-Oriented Language) is widely used in the financial industry, particularly in banking, insurance, and credit card systems. It excels in handling large-scale financial transactions and batch processing, making it a go-to choice for core banking systems, transaction processing, and accounting operations. Many legacy systems in financial institutions still rely on COBOL due to its stability, scalability, and ability to manage complex data processing tasks. Despite being an older language, it continues to play a crucial role in the financial sector, particularly in maintaining and updating legacy systems that require high reliability.

| Listing 3. Executing the shellcode in the Fortran programming language. |

![Applsci 15 11862 i003 Applsci 15 11862 i003]() |

| Listing 4. Executing the shellcode in the COBOL programming language. |

![Applsci 15 11862 i004 Applsci 15 11862 i004]() |

5. Result

5.1. Antivirus Scan Results

We evaluated one functionally equivalent artifact per language under identical build profiles and uploaded each artifact once per engine aggregator session with caches cleared. Engines are reported anonymously (E1–En). For each artifact we recorded: (i) the number of engines that flagged the binary (

DR), (ii) any family or heuristic name when available, and (iii) whether the flag was from static inspection or from on-execution emulation.

Table 2 and

Table A1 lists vendor-facing names for traceability.

Across the four ecosystems, C and C# showed higher static DR than Fortran and COBOL. The effect persists when normalizing by binary size and number of imports. On-execution results reduced the gap but did not remove it. The variance is consistent with differences in runtime libraries, metadata layouts, and how each compiler materializes byte arrays or immediate constants. We observed no flags for samples that failed the equivalence oracle (missing protection transition or extra side effects); such samples were excluded from aggregation.

5.2. Comparison of the Shellcode Patterns

Figure 2 shows the byte prefix extracted from the stub used to exercise the dispatch path; the leading six bytes are

fc 48 83 e4 f0 e8.

Figure 3 illustrates a simple content check: a hex dump followed by a grep on the prefix. The prefix is present as a contiguous run in the C and C# artifacts but not in the Fortran and COBOL artifacts.

Two causes explain the absence of a contiguous prefix in some builds: (i) when the stub is represented as an array of integers rather than uint8_t/byte, compilers emit interleaved zero bytes due to element width, producing patterns of the form fc 00 48 00 83 00 ...; and (ii) some toolchains materialize bytes through register immediates and stores, which spreads the sequence across instructions and relocations. In both cases the semantic dispatch path is identical, but static pattern matching on short byte runs becomes less reliable.

5.3. Disassembling the Samples

As shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, panel (a) places the code and data views side by side. The instruction

lea rcx, byte_... takes the address of the byte block in the data section, after which the loader allocates memory and calls

RtlMoveMemory. This copies the elements into a writable buffer and recreates a contiguous sequence before the protection change and dispatch. Panel (b) enlarges the data representation. The compiler stores the bytes as widened integer elements, which appear in the disassembly as

dup(0) patterns and in the hex dump as interleaved

0x00. This preserves content but breaks long contiguous prefixes in the file image, so prefix-based grep and short static signatures are less likely to match. At run time the address-taking and copy steps reconstruct the same buffer seen in other languages, which explains why behavioral checks still observe the allocation, protection transition, and thread start even when static hits are fewer.

As shown in

Figure 6, the upper panel shows the compiler emitting the stub under the symbol

b_22_22 as individual elements, not as a flat byte array; the file image therefore lacks a long contiguous prefix and simple hex-prefix searches fail. The lower panel shows the use site:

lea rdx, b_22_22 takes the address,

RtlMoveMemory copies the bytes into a writable buffer, and a contiguous block is recreated before the protection change and dispatch. Static short-run signatures flag this case less often, while behavior-focused checks still observe the copy and execution sequence.

5.4. Per-Language Observations

To provide a clearer, side-by-side comparison of these syntactic and structural differences,

Figure 7 visually depicts how the exact same shellcode payload is represented and loaded in C, C#, Python, and COBOL.

C (native): The stub is embedded as a contiguous

unsigned char array in a data section, copied once into a heap region, then executed after an RW→RX protection change. This layout yields short contiguous byte runs that survive linking, so simple hex-prefix searches succeed and several engines map them to family or heuristic names (

Table 2). On-execution flags typically occur at the permission change or thread creation. The import table is compact and stable; thus static indicators dominate while behavioral cues confirm the event sequence.

C# (.NET 6): The artifact uses managed control flow with P/Invoke for the required Win32 calls. IL metadata, the assembly manifest, and P/Invoke descriptors enlarge the static surface compared with C. The stub appears as a contiguous blob in resources or .rdata, so prefix searches still match and static detections are common. On-execution flags are also present and align with transitions across the CLR boundary and the protection change. The API sequence and RW→RX step remain identical to the native build per the equivalence oracle.

Fortran (native): The compiler stores the stub as wider integer elements, which produces interleaved zeros in the data section (xx 00 yy 00 ...). Copy length and protection change match the canonical path, but the fragmented representation reduces short-run signature matches. Engines then rely more on import/section features or behavioral traces. Fortran runtime support adds initialization symbols, yet this does not reconstruct a contiguous prefix; the observed gap relative to C/C# is therefore attributable to byte materialization rather than semantic differences.

COBOL (native): The toolchain materializes bytes via immediate moves and stores into a buffer, distributing the prefix across instruction boundaries instead of emitting a single array. Allocation, RW→RX, and dispatch follow the same APIs as other languages, satisfying equivalence checks. Hex-prefix searches over the file image rarely return a continuous match, so static short signatures trigger less often, while behavioral checks still record the protection transition and thread start. Runtime initialization affects import density and section layout but not the underlying dispatch semantics.

5.5. Robustness Checks and Limitations

We repeated the scans after rebuilding with deterministic build options when available. The detection ordering by language remained unchanged. We also repeated the grep check using a longer prefix (≥16 bytes) and confirmed the same outcome: contiguous matches in C/C#, fragmented representations in Fortran/COBOL. These checks support the interpretation that byte-materialization strategies, not semantic differences, explain the pattern results. Limitations include aggregator-dependent emulation coverage and vendor policy drift; to mitigate, we report both static and on-execution outcomes and log build metadata for replication.

A further limitation is the study’s specific linguistic scope. As noted in our related work, modern languages such as Go, Rust, and Python are increasingly leveraged for malware development. However, this study intentionally focused on establishing a baseline comparison between mainstream, high-detection languages (C, C#) and legacy languages (Fortran, COBOL). The rationale for this focus is that these legacy toolchains, while less scrutinized by modern security tools, remain in active use in critical financial, scientific, and infrastructure sectors, creating the “legacy code, live risk“ scenario we aimed to investigate. Therefore, a comprehensive experimental comparison incorporating Go, Rust, and Python remains a critical and immediate next step for future work.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

6.1. Conclusions

The experiments conducted on shellcode execution across different languages such as Fortran, COBOL, and C# demonstrate that the core shellcode remained unchanged, but the rates of detection by antivirus software differed. Fortran and COBOL exhibited lower detection rates than C and C#, indicating that language choice may influence the evasion of antivirus mechanisms. This highlights the potential for unconventional programming languages, such as COBOL and Fortran, to be leveraged for stealthier malware, emphasizing the importance of addressing security challenges across diverse programming environments.

It is important to note that this research did not implement any advanced evasion techniques such as encryption, encoding, or obfuscation. The shellcode was tested in its raw form, without modifications intended to bypass analysis tools. However, had techniques such as encryption or obfuscation been applied, the difficulty of reverse engineering and analyzing the malware would likely have increased, further impairing detection by antivirus software. This highlights the potential for malicious actors to leverage both unconventional programming languages and additional techniques to enhance the stealthiness of malware.

The results of this study underscore the potential for older, unconventional programming languages such as Fortran and COBOL to be exploited by attackers seeking to bypass modern security measures. These languages, often associated with legacy systems, are less scrutinized by contemporary antivirus engines, creating a blind spot that sophisticated malware could exploit. In environments where Fortran and COBOL are still used—such as critical infrastructure, financial systems, and scientific computing—this presents a considerable risk. Attackers could leverage the lower detection rates and relative obscurity of these languages to launch stealthier attacks, particularly against systems that rely heavily on legacy code. As such, it is imperative that security strategies evolve to encompass not only modern languages but also those that underpin vital legacy systems. Addressing the security challenges posed by Fortran, COBOL, and similar languages will be crucial in mitigating potential threats and enhancing the resilience of legacy systems in the face of evolving cyber attacks.

6.2. Future Work

Future work will proceed in two main directions: expanding the experimental scope using automated methods and developing new defensive recommendations.

First, the experimental baseline will be expanded. This includes incorporating modern languages popular in malware development, such as Go, Rust, and Python. More importantly, we plan to leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) to automate the exploration of this expanded scope. We will task LLMs to generate functionally equivalent loaders using different coding styles, obscure libraries, and compiler-specific optimizations to systematically discover the most evasive language and build combinations. This expanded testbed will also be complemented by deep behavioral instrumentation, performing fine-grained tracing of the system call sequences and execution timing profiles for each variant to identify precisely why certain builds evade detection.

Second, based on our findings, we suggest specific technical approaches for defensive development, directly addressing the need for expanded practical recommendations. For behavioral analysis, our study confirmed that the canonical API sequence (VirtualAlloc →RtlMoveMemory→VirtualProtect→ CreateThread) is a language-agnostic signal. While EDR systems can hunt for this sequence, a logical evasion step for malware is to substitute these canonical APIs with their undocumented Win32 API equivalents (e.g., using NtAllocateVirtualMemory instead of VirtualAlloc). Therefore, future defensive work must evolve to detect this semantic behavior at the system-call level, regardless of the specific user-mode wrapper. For the integration of machine learning methods, our results show that legacy toolchains produce distinct static artifacts (e.g., import table density, section layouts, PE metadata). This presents a clear opportunity to train ML models on these toolchain fingerprints to distinguish benign legacy applications from anomalous binaries that, while compiled with a legacy toolchain, also contain suspicious indicators.