1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) and distributed ledger technologies (DLTs), particularly blockchain, has catalyzed a paradigm shift in how data is processed, shared, and secured in collaborative digital ecosystems. AI models are increasingly being deployed in sensitive domains such as healthcare, finance, critical infrastructure, and government decision-making, where collaboration among multiple stakeholders is crucial for improving accuracy, robustness, and fairness [

1].

At the same time, blockchain provides a decentralized infrastructure that ensures immutability, transparency, and tamper-resistance of recorded data, making it an attractive backbone for collaborative AI workflows [

2]. The convergence of AI and blockchain promises unprecedented opportunities for building trustworthy, decentralized, and data-driven applications. Yet, this convergence is not without its fundamental challenges, particularly those related to privacy preservation, accountability, and efficiency in collaborative environments.

In collaborative AI settings, such as federated learning (FL), multiple participants contribute local model updates or decisions that are aggregated to improve a global model. When integrated with blockchain, such contributions can be immutably recorded, verifiable, and accessible to authorized parties. However, the act of recording AI contributions on-chain introduces inherent risks of identity leakage, traceability, and privacy exposure, especially if cryptographic safeguards are not adequately designed [

3].

On-chain records are, by nature, transparent and persistent, which may lead to unintended inferences about individual participants, their data distributions, or their roles in decision-making processes. For example, in a healthcare federation where hospitals collaboratively train a disease detection model, revealing the identity of each contributor can inadvertently disclose sensitive institutional capabilities or patient demographics. Similarly, in financial consortia, exposing the source of trading signals or risk assessments may undermine competitive confidentiality [

4].

Therefore, there is a pressing need for privacy-preserving mechanisms that allow AI contributions to be recorded on blockchain in a way that ensures both verifiability and unlinkability [

5]. This tension between transparency and privacy forms the core motivation of this work. We contend that without carefully engineered cryptographic primitives, collaborative AI over blockchain may compromise participant trust, discourage participation, and fail to meet regulatory requirements such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

The motivation for combining blockchain with collaborative AI is multifold. It provides decentralized governance and eliminates the need for a trusted central authority, aligning with the federated and distributed nature of collaborative AI. Every contribution can be logged immutably, ensuring accountability and facilitating auditing. Moreover, the cryptographic backbone of blockchain enhances data integrity and provides a foundation for secure multiparty computation [

6].

Despite these advantages, blockchain also amplifies the privacy dilemma in collaborative AI. While AI requires diverse and distributed data sources to thrive, contributors are often reluctant to share data or even disclose their participation due to competitive, ethical, or legal concerns. For example, pharmaceutical companies engaged in joint drug discovery cannot risk revealing proprietary datasets or the very fact that they are contributing particular types of genomic insights. In such cases, blockchain transparency, although a feature, becomes a liability if not complemented with privacy-preserving cryptography [

7].

From a technical perspective, privacy-preserving collaboration over blockchain requires solutions that balance three competing requirements: confidentiality of contributor identities and inputs, verifiability of contributions, and scalability of verification. Meeting these requirements is far from trivial. Traditional digital signatures can guarantee authenticity but fail to provide unlinkability or anonymity. Zero-knowledge proofs offer strong privacy but often come at prohibitive verification costs in resource-constrained blockchain environments. Homomorphic encryption supports secure computation but requires heavy computation and introduces latency. Hence, there is a need for novel approaches that simultaneously preserve privacy, ensure verifiability, and maintain efficiency [

8,

9].

Despite substantial progress in blockchain-based AI frameworks, three key challenges remain largely unresolved: identity leakage, traceability, and verification cost. To address these challenges, we propose a novel framework that leverages aggregate signatures (ASs) with aggregate public key techniques, instantiated over ElGamal cryptography. Aggregate signatures allow multiple participants to jointly produce a single compact signature on distinct messages, significantly reducing verification costs. By integrating aggregate public keys, we achieve a level of unlinkability and anonymity, ensuring that individual public keys or identities are not exposed during verification.

Our design contributes to bridging the gap between transparency and privacy, a central paradox of blockchain-enabled AI systems. By enabling participants to collectively sign model updates or decisions without revealing individual identities, we mitigate identity leakage and prevent traceability across rounds. At the same time, the compactness of aggregate signatures dramatically reduces verification costs, aligning with blockchain’s scalability requirements.

Our design builds on well-established signature and aggregation primitives while prioritizing deployment practicality and unlinkable aggregation for privacy-sensitive AI collaborations. The existing literature on compact or aggregatable signatures includes the Boneh–Lynn–Shacham (BLS) family and the BGLS aggregate constructions, which enable very short and directly aggregatable signatures using bilinear pairings and have been widely studied for blockchain and PKI optimizations. Multisignature and threshold-signature schemes (e.g., Boldyreva and follow-up works) target collaborative signing with strong threshold properties but typically require interactive key setup or key sharing, which increases coordination complexity in large decentralized networks [

10].

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: In

Section 2, we discuss blockchain and AI interaction, and traditional signature schemes vs. aggregate schemes. In

Section 3, we provide an overview of aggregate signature schemes. In

Section 4, we present our proposal, demonstrate the protocol design, and show a security analysis.

Section 5 discusses experimental results and performance evaluation. Finally, we conclude with

Section 6.

2. Background

The blockchain–AI integration requires careful cryptographic and architectural design. For instance, while blockchain guarantees immutability, it does not natively protect the confidentiality of participants. Likewise, although AI can reduce computational burden through optimization, it does not solve the inherent storage and verification overhead created by recording signatures or model updates on-chain. These gaps highlight the necessity for lightweight cryptographic solutions that ensure both privacy protection and efficiency without undermining blockchain’s consensus integrity.

This is precisely where advanced signature schemes become relevant. When applied to blockchain–AI ecosystems, such schemes ensure many aspects, like minimizing verification steps and addressing the dual concerns of scalability and privacy leakage, meaning collaborative intelligence remains verifiable and tamper-resistant, yet unlinkable to individual contributors.

Digital signatures are fundamental to modern cryptographic systems. A digital signature allows a party to prove the authenticity and integrity of a message, ensuring authenticity, integrity, and non-repudiation. Well-known digital signature schemes include RSA signatures, Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA), and Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA). These schemes are widely used in secure communication protocols (e.g., TLS, SSH), blockchain transactions (e.g., Bitcoin uses ECDSA), and authentication frameworks.

In a traditional setting, each signer generates an individual signature for a message using their private key. The verifier checks each signature independently against the corresponding public key. While effective in ensuring authenticity, this approach suffers from scalability limitations in collaborative environments, including these points: each participant’s contribution requires a separate signature; verification requires linear time with respect to the number of participants; and storage overheads grow proportionally to the number of signatures. For collaborative AI over blockchain, where thousands of updates may be recorded in each round, traditional signatures impose excessive computational and storage costs.

Aggregate signatures, introduced by Boneh et al. in 2003 [

11], address the scalability limitations of traditional signatures. An aggregate signature scheme allows multiple signatures, generated by different users on different messages, to be compressed into a single short signature. This compact aggregate can then be verified against all signers’ public keys with a single verification operation.

Formally, an aggregate signature scheme consists of the following algorithms: KeyGen generates a public/private key pair for each participant. Sign produces a signature on a given message using the signer’s private key. Aggregate combines multiple signatures into a single compact aggregate signature. Verify verifies the aggregate signature against all participants’ public keys and messages.

The advantages of aggregate signatures are substantial: efficiency, where the verification time and communication overhead are significantly reduced; compactness, when a single aggregate signature replaces potentially thousands of individual signatures; and scalability, in which aggregate verification makes large-scale collaborations feasible on blockchain, reducing transaction size and block storage requirements.

While aggregate signatures improve efficiency, they do not inherently guarantee privacy. If each individual public key is included in verification, adversaries can still link contributions to specific participants. To overcome this, researchers have proposed extensions such as the aggregate public key technique that is integrated in our scheme, group signatures, and ring signatures, which introduce anonymity and unlinkability.

In particular, group signatures allow a member of a group to sign on behalf of the group without revealing which member signed. However, a group manager can typically open the signature, which introduces a potential privacy risk. Ring signatures provide signer anonymity without a central manager, but verification costs remain relatively high. Aggregate signatures with aggregate public keys strike a balance: they enable compact, verifiable signatures while hiding the identities of individual signers by compressing their public keys into an aggregated form.

This property is particularly valuable for collaborative AI over blockchain, where both efficiency (low verification cost) and privacy (unlinkability of participants) are paramount.

3. Related Work

The intersection of blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI) has been studied from several perspectives, with a strong emphasis on FL, privacy preservation, and efficient consensus mechanisms. Although a variety of cryptographic tools have been explored, the specific use of aggregate signatures with public key aggregation for blockchain-based AI collaboration remains largely unexplored. This section reviews existing work along three major directions: blockchain-assisted FL, cryptographic approaches to privacy preservation, and signature schemes in collaborative AI.

Several recent studies have explored secure distributed and FL frameworks, highlighting the challenges of privacy, trust, and decentralized model aggregation [

12,

13]. FL has emerged as a leading paradigm for collaborative AI, enabling multiple entities to train a shared model without centralizing raw data. The integration of FL with blockchain has been extensively studied to mitigate the risks of model poisoning, data leakage, and single points of failure in traditional FL coordinators.

Recent studies have also explored the integration of unsupervised and distributed learning paradigms within federated frameworks to enhance adaptability and scalability in decentralized environments. In particular, Yang and Sinaga [

14] proposed Federated Multi-View K-Means Clustering, which enables collaborative clustering without sharing raw data among participants. They implemented a synthetic and six real multi-view datasets and then performed Federated Peter-Clark for causal inference setting to split the data instances over multiple clients.

Several works have introduced blockchain-based frameworks to ensure secure aggregation and immutable recording of model updates. Wang et al. [

15] proposed a permissioned blockchain-based FL system that leverages node reputation to enhance the trustworthiness of updates. The authors of [

16] presented an Intel SGX-enabled blockchain system to guarantee secure aggregation within trusted execution environments (TEEs). Ref. [

17] developed PPBFL, a privacy-preserving blockchain framework for FL that combines ring signatures with a novel proof-of-training-work mechanism. The authors of [

18] introduced DP-BBVFL, a blockchain-enhanced vertical FL framework that integrates differential privacy with smart contracts for secure coordination.

While these studies confirm the effectiveness of blockchain in securing collaborative learning, they primarily rely on computationally expensive cryptographic techniques such as homomorphic encryption, differential privacy, or trusted enclaves. These solutions often incur high computational and verification costs, making them less suitable for resource-constrained blockchain environments where scalability is crucial.

The protection of participant privacy in collaborative AI has inspired the use of a variety of cryptographic primitives. Homomorphic encryption allows computations to be performed directly on encrypted data, ensuring confidentiality but at significant computational cost. Differential privacy introduces random noise into updates to prevent information leakage, but may degrade model accuracy when applied excessively.

Beyond these methods, digital signature variants have gained prominence in protecting identity privacy while ensuring verifiability. Group signatures [

19] enable members of a group to sign messages on behalf of the collective, providing anonymity with accountability via a group manager. Ring signatures [

20] provide unconditional signer anonymity within a set of public keys, eliminating the need for a central authority. Both approaches have been applied in blockchain-based FL to hide participant identities while preserving verifiability.

However, group signatures require a trusted manager with the power to de-anonymize signers, which may not align with the decentralized ethos of blockchain. Ring signatures, while providing anonymity, do not inherently optimize verification cost, and their verification complexity grows with the number of participants. Consequently, while these techniques enhance privacy, they do not adequately address the efficiency challenges of verifying large volumes of AI contributions on-chain.

Digital signatures form the backbone of blockchain authentication, but traditional signature schemes (e.g., RSA, ECDSA, DSA) are inefficient in large-scale collaborative settings, since each participant must generate and publish an individual signature. As noted in FBChain [

21] and PrivateFL [

22], this approach results in excessive verification and storage costs, undermining blockchain scalability.

To overcome these limitations, researchers have begun exploring advanced signature schemes in the context of FL. GSFedSec [

23], for example, applies group signatures to FL to ensure that model updates are verifiable without revealing participant identities. While this reduces privacy risks, the scheme does not reduce verification cost and requires additional group management overhead.

Notably absent from the existing literature is the application of aggregate signatures (cryptographic primitives that allow multiple signatures on different messages from different users to be compressed into a single compact signature). Aggregate signatures, first introduced by Boneh et al. [

11], can significantly reduce blockchain storage and verification costs, while extensions such as aggregate public keys further enhance privacy by hiding individual signer identities.

Ref. [

24] presented Real Threshold ECDSA, a malicious secure

t-out-of-

n signing protocol with fault detection, share repair, and liveness guarantees. However, its four-round pre-signing phase, high signing time, and state complexity make it less suitable for real-time or large-scale deployments. The authors of [

25] introduced a BLS threshold signature enabling one-round, non-interactive signing with compact signatures and adaptive corruption resistance. Its drawback lies in reliance on bilinear pairings, which increase CPU usage, latency, and energy consumption, limiting suitability for IoT and high-throughput settings. Despite their advantages, these techniques have not yet been applied to AI collaboration over blockchain, leaving a clear research gap.

From the above, it is evident that prior efforts have primarily focused on homomorphic encryption, differential privacy, secure enclaves, and group/ring signatures as tools for privacy-preserving blockchain-based AI. While effective in specific contexts, these methods either impose high computational costs or fail to simultaneously address privacy, verifiability, and scalability.

This paper departs from existing approaches by introducing an ElGamal-based aggregate signature scheme with public key aggregation tailored to blockchain-based AI collaboration. Unlike group or ring signatures, our approach provides compact, verifiable, and unlinkable signatures without requiring a central authority or expensive zero-knowledge proofs. By compressing multiple contributions into a single signature and aggregating public keys, the scheme directly addresses the key challenges of identity leakage, traceability, and verification cost, filling a gap in the literature.

We intentionally adopt an ElGamal-style aggregated public key construction (pairing-free) to reduce reliance on bilinear pairings and to simplify assumptions while achieving compact on-chain footprints; only a single aggregated tuple

needs to be committed and verified on-chain for each round. Recent work has also pursued pairing-free and certificateless aggregate schemes to improve practicality in constrained environments; our approach is aligned with these efforts while additionally providing per-round re-randomization of the aggregate public key to hinder cross-round linkage [

26]. Finally, we note that data-level privacy techniques (for example, image privacy methods based on DCT compression and nonlinear dynamics) address complementary problems (protecting content and features) and can be combined with our signer anonymity primitives to provide end-to-end privacy for distributed AI workflows [

27].

4. Proposed Scheme

The presented technique for building an AS scheme is based on an updated ElGamal system, which is used to produce personal signature shares.

ElGamal is a basic public key cryptosystem that has played a central role in digital security. Its security is rooted in the computational hardness of the discrete logarithm problem. Owing to its flexibility, ElGamal serves as the basis for diverse applications, such as secure communication, digital signatures, and authentication protocols. The system’s operations include key generation, encryption, and decryption, relying on modular arithmetic over large prime fields, with security increasing proportionally to the key size.

In contrast to conventional AS approaches, where a unique signing key is divided among multiple users, the presented approach permits each user to maintain an independent private–public key pair. The individual public keys can then be aggregated into a single combined public key. Likewise, the users’ signatures are aggregated into one compact signature, which can be verified using the combined public key while simultaneously revealing the number of users who contributed to the signing process.

4.1. Basic Functions

The output of the Key Generation Function is a pair of private and public keys (

). Given a prime number

q, a generator

g is selected, picks a private key,

x, and calculates the corresponding public key,

y, as denoted in (

1).

Two hash values

h and

h are used as shown by (

2).

where

m denotes the plaintext to be signed and

n is the number of signers.

To sign the plaintext,

m, the signing function utilizes the key pair (

), it outputs the value

that is presented by (

) demonstrated by (

3) and (

4).

where

r is a fresh random value.

The signature

is verified by using (

5).

For the verification correctness

We introduce an aggregate signature (AS) framework that unifies the combination of both user signatures and public keys. In our design, each participant signs messages independently through an adapted ElGamal technique, which employs added randomness and dual hashing to withstand classical cryptanalysis (Algorithm 1). This modification strengthens robustness and also ensures integrity in collaborative environments. Unlike conventional schemes that either depend on a single signing entity or distribute fragments of one secret key, our construction empowers users to retain their own private–public key pairs while still producing a collective signature. The outcome is a concise, verifiable, and scalable signature that simultaneously guarantees authenticity, efficiency, and strong resistance against forgery, qualities that make the scheme particularly attractive for decentralized and resource-limited systems.

4.2. System Overview

Every user first establishes a cryptographic key pair through the KeyGen algorithm. When a plaintext m is to be signed, the signer employs the PersSig procedure to create a unique signature. This procedure is based on a refined version of the ElGamal scheme, augmented with randomness and dual hashing to improve resistance against cryptanalytic attacks. The signing process yields a signature tuple .

The signing process is managed by the AggSig function. If the current user is the first signer, it initializes the aggregated signature based on its personal signature and public key. Otherwise, the user verifies whether the number of signers has already been reached by checking a cryptographic condition on . If not, it generates its personal signature, updates the aggregated signature and public key accordingly, and forwards the updated to the next selected user.

User participation is coordinated through the SmartSelectUser function, which adaptively identifies the next signer according to context-driven factors such as energy reserves, communication range, or other optimization objectives. Once the predefined number of signers n has been reached, the aggregation phase concludes. The outcome is a compact aggregate signature which can be validated by any verifier through the ASVerf algorithm. This verification process confirms the integrity of the aggregation by checking consistency with the original message and the associated public parameters, thereby guaranteeing both the correctness and authenticity of the collective signature.

Algorithm 1 demonstrates the PersSig procedure that takes the following inputs: the public parameters (), plaintext m, and pair keys (). PersSig gives .

The users then generate the AS

by using the AggSig function, which picks the following inputs: plaintext

m, pair keys (

), the public parameters (

), and, eventually, an intermediate signature

, if he is not the first signer. AggSig function is illustrated by Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 1 Personal signature |

Require: m, (), ()- 1:

function PersSig - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

return - 9:

end function

|

| Algorithm 2 AS |

| Require: m, (), (), | |

| 1: function AggSig | |

| 2: if This is the first signer then | |

| 3: | |

| 4: | ▹ aggregate signature part 1 |

| 5: | ▹ aggregate signature part 2 |

| 6: | ▹ aggregate public key |

| 7: | |

| 8: return | |

| 9: else | |

| 10: | |

| 11: | |

| 12: if then | ▹ AS not acheived yet |

| 13: | ▹ i: user i |

| 14: | |

| 15: | |

| 16: | |

| 17: | |

| 18: send to: user(SmartSelectUser(n)) | |

| 19: else | |

| 20: return | ▹n acheived |

| 21: end if | |

| 22: end if | |

| 23: end function | |

The verification procedure is illustrated in Algorithm 3. It picks the inputs: plaintext

m, AS

, and public parameters (

).

| Algorithm 3 AS Verification |

Require: m, , ()- 1:

function ASVerf - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

if then - 5:

return 1 - 6:

else - 7:

return ⊥ - 8:

end if - 9:

end function

|

For AS verification correctness

Let

be a cyclic multiplicative group of prime modulus

q with generator

g. Let

be a cryptographic hash function; for clarity we write

so that signature values are bound to the message

m, the protocol epoch/nonce, and the target signer count

N. Each user

i holds a secret key

and a public key

.

The per-user signing algorithm

(executed by user

i) returns a pair

that satisfies the per-user verification relation

Define the aggregated state after

k signers, in the sequential order they were applied, as

we reduce

modulo

when exponent arithmetic assumes exponent reduction in

.

The aggregator, or any verifier, accepts the final aggregate

if and only if

Theorem 1 (Correctness)

. Suppose each participating user i produces a per-user signature satisfying (7). Then, after k honest signers have sequentially applied their signatures and updated the aggregate state as described above, the aggregated values satisfy Equation (9). In particular, when (the target number of signers), the final verification equality holds and the aggregator accepts. Proof. We prove the claim by induction on .

Base case (

). Let user 1 produce

satisfying (

7). By definition,

Compute the left-hand side of (

9):

Apply the per-user relationship (

7) for

:

Hence

which is exactly (

9) for

. Thus, the base case holds.

Inductive step. Assume the invariant holds for some

; i.e., after

k signers

Consider the

-th honest signer producing

satisfying (

7) with its public key

. The sequential update rules yield

Raise

to the power

h and multiply by

:

Using the inductive hypothesis to replace

by the right-hand side of (

9), we obtain the following result.

Apply the per-user relation (

7) for user

:

Substituting this yields

Group the powers of

g and combine product terms as follows:

Thus, the invariant holds for

. By induction, it holds for all

.

When the sequential process is completed after

N signers (i.e.,

), the aggregated tuple

satisfies Equation (

9). Therefore, the final verification check passes, and the aggregator (or any verifier) accepts the aggregate signature. □

4.3. Application to Blockchain and AI: Protocol Design

The proposed ElGamal-based aggregate signature scheme with aggregate public keys is well-suited for decentralized AI applications where multiple parties collaboratively contribute updates while preserving privacy and ensuring verifiability. We outline a protocol that integrates our scheme into blockchain-based AI systems.

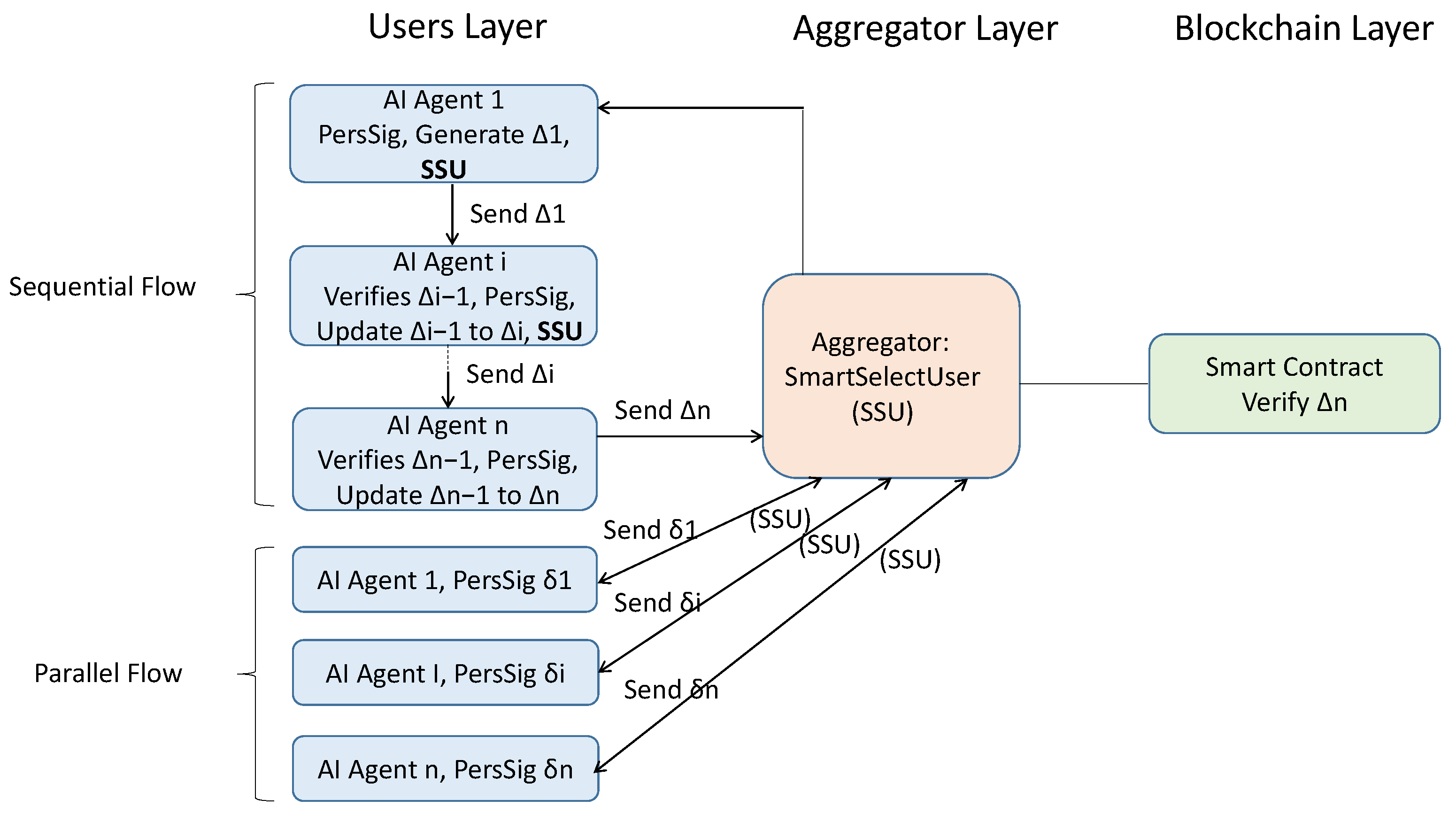

Based on the SmartSelectUser function, our scheme supports two execution modes (

Figure 1):

Sequential mode: The aggregator selects first, then each signer selects the next, forwarding the growing aggregate. Parallel mode: The aggregator preselects all n users, collects their partials independently, and then aggregates them. In this mode, users execute lines 3–8 of Algorithm 2, and the aggregator executes lines 14–16, initializing with 1 and with 0.

The system model contains four parts: Participants (AI Agents/Data Providers): Entities that perform local computations (e.g., gradient updates in FL or inference results in distributed AI). Each participant holds an ElGamal key pair. Blockchain Network: Provides an immutable recording of aggregated updates and enforces consensus. Smart contracts act as verifiers and orchestrators of signature aggregation. Smart Contract/Aggregator: Coordinates aggregation and verifies the final compact signature on-chain. Verifiers: Any party interested in validating the authenticity of aggregated AI updates or decisions without accessing individual contributions.

The workflow instantiates Algorithm 2 into three blockchain-integrated steps: In the first step (initialization, local contribution, and signing), each participant generates an ElGamal key pair. A smart contract initializes system parameters and maintains the global aggregate public key. Each AI agent computes its local update m and applies the AggSig function. The first signer produces an initial tuple . Subsequent signers iteratively update using Algorithm 2, extending the aggregate signature and aggregate public key without revealing individual identities. The SmartSelectUser function determines the next eligible participant based on context-aware metrics (e.g., energy, latency, trust score). This ensures fairness, reduces stragglers, and improves robustness in federated AI settings.

Then, for on-chain submission, once n signers are aggregated, the final compact signature and the corresponding model update are submitted to the blockchain. Storage cost is minimized due to the constant size of , independent of n. The smart contract records immutably, ensuring transparency and traceability without identity leakage. Finally, in public verification, any verifier can call the ASVerf function to validate against the message m and system parameters. The aggregated signature guarantees correctness and authenticity. The aggregate public key ensures unlinkability, preventing adversaries from tracing contributions to individual participants.

The aggregation is performed off-chain among the participating signers, while the smart contract serves as the on-chain trust anchor responsible for (a) recording the final aggregate signature and associated metadata, (b) verifying the validity of the aggregate signature upon submission, (c) enforcing participation and policy rules for contributors, and (d) triggering incentives or access to shared AI model updates for verified contributions. The contract implements the verification logic corresponding to the equality

by recomputing the necessary hash values and verifying the aggregated values included in the transaction.

Once the last signer finishes aggregation, the final tuple is submitted to the contract; the contract recomputes the verification equation, accepts or rejects the submission, and, if accepted, records the validated result on-chain and optionally triggers reward or model-update events.

Regarding advantages for blockchain-integrated AI, applying this model introduces many advantages, some of which are shown in

Table 1.

As for dynamic participant sets, the proposed scheme naturally supports dynamic participation, where users may join or leave the system across aggregation rounds. Each execution of the aggregation protocol is independent and uses a fresh signer set for round r. Since the aggregate public key is built from the per-round contributions of the active signers only, changes in membership do not require re-keying or updating long-term public keys. A new user joining the system simply registers its public key and becomes eligible for selection in future rounds, while departing users are excluded from the SmartSelectUser sampling and contribute no terms to subsequent aggregates. To avoid ambiguity, a membership snapshot can be fixed at the beginning of each round. This design preserves correctness, unlinkability, and security under the discrete logarithm assumption, provided that fresh randomness is used for each round and each signer verifies the aggregate prefix before contributing.

4.4. Illustrative Example

We illustrate the sequential signing, aggregation, and final verification for signers using small toy parameters. All operations are modulo a prime q. For clarity, we replace the real hash outputs by small integers in this example.

Parameters:

Secrets and public keys: ;

Nonces (ephemeral) used for signatures:

Per-user signatures (PerSig). For each user, we compute

Using the values above, we obtain

Aggregation (AggSig): Starting from

,

,

, and iterating over the three signatures, we update as in the implementation

After processing the three users, we get

Final verification: The aggregator computes

Numerically: , so and the aggregate signature verifies successfully.

Thus, per-user signatures , , and . Aggregated values: . Verification holds.

4.5. Security Analysis

4.5.1. Parallel Model

Let be the set of registered agents with keys —public keys and secret keys . A transaction proposal consists of a message m and policy/public parameters (e.g., generator, modulus, target quorum n, validity window, and domain tags). The function SmartSelectUser deterministically or pseudo-randomly selects a list of users (candidate signers) based on context-aware features (energy, latency, proximity, etc.). Each selected agent produces a partial signature . Once n partials are collected, the aggregator computes a compact aggregate signature for some with , and is the aggregated public key (Algorithm 2 line 16). Anyone verifies with

. All events (selection digest, partial-sign attestations, , and verification outcome) are committed on-chain.

We assume a base signature primitive that is Unforgeable under Chosen Message Attack (UF-CMA)-secure, and a collision-resistant hash H.

We analyze the following adversaries; all are probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT):

External adversary : full network control (eavesdrop, replay, reorder, drop, delay), but no secret keys.

Adaptive insider : corrupts up to j registered agents adaptively (obtains their ), can submit malicious partials and collude.

Selection manipulator : tampers with selection inputs (context features) to bias SmartSelectUser toward compromised nodes or to starve honest ones; may also attempt Sybil amplification subject to enrollment rules.

Blockchain minority : controls a minority of consensus power; can delay or censor some transactions but cannot rewrite finalized history.

In the security goals, we target (i) aggregate unforgeability (no valid on without n genuine signers in ), (ii) robustness to selection manipulation (bias cannot yield signatures outside attacker-controlled keys), (iii) freshness and replay protection (no reuse of stale partials across policies/contexts), and (iv) liveness under churn (honest transactions complete when at least n responsive honest agents exist).

Game UF-AGG (Aggregate Unforgeability): The challenger publishes and . may adaptively query partial signatures for any on behalf of corrupted or (via a partial-sign oracle) honest agents, and can observe on-chain values for any j-tuples it legitimately assembles. Finally, outputs . A win is counted if and fewer than n honest members of actually produced partials on under .

Lemma 1 (Aggregate UF-CMA)

. If the base signature is UF-CMA secure, H is collision-resistant (or a random oracle, matching the combine rule), and each has a valid PoP (non-interactive proof of possession for rogue-key resistance) at enrollment, then for any PPT , Proof. Assume a forger wins UF-AGG. By unbinding of PoP and domain-separated hashing of per-signer contributions (e.g., coefficients ), any valid necessarily entails at least one fresh per-signer signature under on input derived from that was never issued by the partial-sign oracle. We embed the UF-CMA challenge of into one honest signer index and program the hash if in ROM. A successful yields a UF-CMA forgery for , contradicting its security. □

Rogue-Key Resistance: Without PoP, may register keys algebraically related to honest ’s to absorb their contributions (rogue-key attack).

Lemma 2. If enrollment requires a non-interactive PoP for each and the chain rejects keys without PoP, rogue-key attacks are infeasible beyond .

Replay/Freshness Game FR: records partials and attempts to replay them under altered .

Lemma 3. If the partial-sign input domain includes and these are hashed into , then any change to message/policy/epoch invalidates replays, so .

Selection Manipulation Robustness: biases SmartSelectUser to over-select corrupted agents.

Proposition 1. Even under fully biased selection, aggregate unforgeability (Lemma 1) holds; producing Δ for still requires n partials from members of . Manipulating selection cannot yield signatures outside attacker-controlled keys, it only affects liveness and fairness.

Liveness Under Churn: Assume at least fraction of are responsive honest nodes and the network is eventually synchronous.

Lemma 4. If SmartSelectUser samples without replacement from (or from a VRF-driven committee) and the retry budget B satisfies , then the probability of failing to gather n honest partials within the validity window decays exponentially in B.

Table 2 shows an illustration of the threats and mitigations in the proposed architecture.

Where binding means each partial uses ; domain separation means distinct tags for partial vs. aggregate vs. on-chain attestations; rogue-key hardening states that enrollment requires PoP; ASVerf rejects aggregates involving keys without on-chain PoP; and freshness means that ASVerf function checks validity window and rejects reused nonces.

Under UF-CMA security of the base signature, collision resistance of H, enrollment PoP, and append-only blockchain finality, the scheme achieves aggregate unforgeability, replay protection, accountability, and robustness against selection manipulation. Adversaries may still affect timeliness but cannot produce a valid for without obtaining n genuine partials from .

The table of threats and mitigations (

Table 2) presents both the implemented and the conceptual countermeasures envisioned for practical deployment. In the current prototype, we implemented and tested core protocol-level protections, including fairness randomization within SmartSelectUser to mitigate selection bias and replay consistency via message-hash binding. Other mechanisms, such as trusted attestation of selection metrics, rate-limited enrollment, and stake-based Sybil prevention, are part of our design roadmap and were included in the table to illustrate the full security posture of the proposed framework in real-world deployments. These advanced defenses were not yet implemented in the present simulation but are straightforward to integrate as external modules in future work.

4.5.2. Sequential Model

We analyze the security of the aggregate signature workflow when SmartSelectUser operates sequentially, and the per-hop selection tokens/signer order are not published or auditable by external verifiers.

Let

be the set of registered agents with keys

: public keys

and secret keys

. A transaction proposal is

. The aggregator

A initially executes

and sends

(and any necessary selection token) to

. Signer

performs a partial signature

, updates the aggregate

, executes

and forwards

to

. This continues sequentially until

(the

n-th signer) transmits the final

back to the aggregator for finalization and on-chain commitment.

We adopt a set of primitives and assumptions, including a base signature scheme that is UFCMA secure. A collision-resistant hash function H (or ROM when needed). Aggregate public key construction that yields an aggregate public key under which the compact aggregate can be verified without exposing individual public keys. Non-interactive Proof-of-Possession (PoP) at enrollment to prevent rogue-key attacks (PoP need not be published with every aggregate). Honest-majority/availability assumption for liveness, at least fraction of are responsive honest nodes during a signing session.

Adversaries are PPT and may act as follows. is a network adversary (that can eavesdrop, delay, reorder, drop, and replay) but cannot break primitives. is an adaptive insider that corrupts up to k signers (obtains ), submits malformed partials, withholds forwarding, or deviates from SmartSelectUser. manipulates selection inputs (feature spoofing or Sybil registration) to bias selection; because tokens are not auditable, such biases are harder to detect. is a malicious aggregator (or final collector) that can fabricate selection requests to cooperators or suppress some signatures before publishing .

Security goals with hidden signer selection include the following:

Aggregate Unforgeability (UF-AGG): No adversary can produce a valid accepted under without obtaining at least n fresh partials from distinct honest signers or breaking the base primitives.

Freshness/Replay Resistance: Aggregates must be bound to so that reusing old partials to forge a new accepted is infeasible.

Privacy/Unlinkability: The aggregate reveals minimal information about which individuals participated; linkage between and individual signers must be infeasible for external verifiers.

Liveness (practical): When sufficiently many honest and responsive signers exist, the protocol completes within the validity window despite some malicious hops (mitigated by timeouts and fallbacks).

Limited Accountability (operational): Because selections are hidden, strong public on-chain accountability is impossible; instead, the protocol supports off-chain dispute evidence or selective reveal under governance to hold misbehaving parties accountable.

Lemma 5 (UF-AGG, Sequential Mode (Non-auditable))

. Under the same primitive assumptions, and assuming the aggregate public key construction is secure (i.e., an adversary cannot create a valid without possessing the required set of constituent public keys or PoP), the sequential non-auditable protocol is UF-AGG-secure Proof. Even when signers are chosen sequentially and tokens are not published, each final aggregate must consist of valid per-signer contributions whose correctness is checked against and against for an external verifier. If an adversary produces without the required fresh partials, one of the per-signer components is a fresh signature that can be extracted and turned into a UF-CMA forgery for , unless the adversary forged the aggregate key binding itself (breaking security). Hence, success implies breaking underlying assumptions. □

4.6. Reduction to Discrete Log

We give a brief reduction showing that an efficient adversary that wins the UF-AGG game (aggregate unforgeability under chosen-message attacks) with non-negligible advantage would yield an algorithm that solves the discrete-logarithm (DL) problem in .

Assume the hash functions used to derive and are modeled as random oracles. Given a DL challenge with unknown such that , embeds as the public key of a target user and simulates the environment for (generating honest keys for others, answering signing queries for non-target keys, and programming the random oracle as needed). If eventually outputs a valid aggregate forgery on some new message that involves , then by rewinding and re-running it with a fresh random oracle response for , obtains two forgeries on the same message but with distinct -values.

Dividing and rearranging the two aggregate-verification equalities cancels honest users’ unchanged contributions and yields a linear congruence in the unknown of the form , where are computable from the two forgeries and programmed oracle outputs. With overwhelming probability , so recovers . Hence, a non-negligible UF-AGG advantage gives a non-negligible DL solver; therefore, under the DL hardness assumption, the aggregate scheme is UF-AGG secure.

Lemma 6 (Unlinkability of Aggregate Public Key)

. Let be a cyclic group of prime order q with generator g. For each user i let be the long-term public key, and let, for each signing round r, the user choose an independent random exponent . Define the per-round aggregate public keywhere is the set of signers in round r. Assuming that the per-round exponents are chosen uniformly and independently and that the discrete logarithm problem in is hard, an adversary observing polynomially many aggregates has only a negligible advantage in linking two aggregates or identifying a contributor, with the advantage bounded by when exponents are λ-bit random. Proof Let

be two rounds with signer sets

and

, and let

Since each

is chosen uniformly at random from

and independently across users and rounds, the value

is a modular linear combination of the unknown secret keys

with random coefficients. From the perspective of an adversary who does not know the

nor the per-round exponents,

is computationally indistinguishable from a uniformly random element of

, except with negligible probability. Consequently,

is indistinguishable from a random group element.

If an adversary could link and with non-negligible advantage, it would imply distinguishing whether two group elements originate from related linear combinations of the same secret keys versus independent random exponents. This capability can be turned into a method to recover information about the hidden linear relations or, equivalently, to solve instances closely related to the discrete logarithm/related decision problems, contradicting the discrete-log hardness assumption. Intuitively, any distinguishing advantage must come from reuse/leakage of exponents, adversarial knowledge of some , or breaking the discrete-log assumption; absent these, the linking advantage is negligible.

Concretely, when each per-round exponent is chosen from a -bit space, the probability that two independently chosen linear combinations collide or yield a detectable correlation is upper-bounded by . Therefore, an adversary’s advantage in linking rounds or identifying a contributor is negligible in , under the stated assumptions. □

Hiding signer order raises particular practical issues;

Table 3 shows mitigations and trade-offs.

When signer selection is not auditable, the design must concede that strong public accountability is unavailable. However, under standard cryptographic assumptions (UF-CMA and collision resistance), the scheme still achieves aggregate unforgeability, freshness, and unlinkability for external verifiers. Practical security then relies on robust enrollment, economic incentives, signed local receipts, time-bounded finalization, and fallback procedures to handle selection bias, withholding, and aggregator misbehavior. The non-auditable variant maximizes privacy and compactness at the cost of immediate public provability of who signed.

Table 3 enumerates conceptual challenges that arise when signer order is hidden and outlines prospective mitigations intended for deployment in decentralized infrastructures. In the current prototype, only the lightweight fairness randomization within SmartSelectUser is implemented and empirically validated. Mechanisms such as deterministic seeding, receipt-based dispute resolution, timeout-retry rules, and selective disclosure auditing are not yet part of the simulation; they represent architectural extensions that can be integrated at the protocol or governance layer.

Threat and Issue Evalutations

Threat 1: In our code, SmartSelectUser() uses random perturbation (+random uniform (−0.01, 0.01)) to avoid deterministic bias, which covers basic fairness randomness, but not TEE attestation, peer verification, or VRF-based selection. So, this mitigation is partially realized (randomization only). Threat 2: Our current simulation processes valid aggregate signatures sequentially; it does not include message authentication tags, pre-checking invalid partials, or any economic mechanism. This defense remains conceptual at this stage. Threat 3: Our current AggSig() and ASVerf() functions bind only m and N (message and number of signers) through hash values h and h’, but not epoch, txid, or nonce. So, replay protection is not fully enforced in implementation (though easily extendable). Threat 4: Our current simulation generates user keys (x,y) locally with no enrollment or registry mechanism. So the scheme assumes an honest key setup. These defenses are design-level suggestions for deployment, not tested in code. Threat 5: In our code, the message m is a generic integer; however, conceptually, it could represent any structured digest.

Issue 1: Our current SmartSelectUser() uses random perturbation for fairness, but not deterministic seeding or staking mechanisms. So only the fairness randomness is implemented; the rest are architectural ideas. Issue 2: The present simulation assumes an honest aggregator and doesn’t generate per-user receipts or implement dispute windows. These are deployment-phase governance mechanisms. Issue 3: Our sequential simulation assumes reliable message passing. Timeout and retry logic were not part of the code. Issue 4: The current work is focused on aggregate signature correctness; privacy vs. auditability controls are discussed conceptually only.

Table 4 demonstrates some advantages of our proposal compared with other techniques.

5. Experimental Results and Performance Evaluation

The implementation was made in Python 3.10 and executed on a Windows 11 OS. The hardware environment consisted of an Intel Core i7 CPU-2.30 GHz, and 16 GB of RAM. The size of the modulus q is 264 bits, and the signed message is 255 bits.

The SmartSelectUser function serves as a context-aware decision module that selects the next eligible participant in the sequential signing process based on three measurable metrics: (a) proximity (distance), (b) residual energy, and (c) network traffic load. We can change weights or include additional metrics (latency, trust score/reputation, and battery model).

Each user

is characterized by these parameters, which are normalized to a common scale. The function then computes a composite score for each candidate using a weighted model as follows:

where

,

, and

denote the normalized distance, energy, and traffic values, respectively, and

are tunable weights satisfying

. In our experiments, we used

, which provides a balanced trade-off between proximity, energy efficiency, and network congestion.

To prevent deterministic bias and ensure fairness and resistance to manipulation, a small random perturbation is added to each score before selection. This randomized tie-breaking mechanism avoids repeated prioritization of the same users while maintaining probabilistic fairness. Furthermore, the parameters used by the function are derived from observable or verifiable system states, making the selection process transparent and tamper-resistant. The final selected user is the one achieving the highest composite score, ensuring adaptive, context-aware, and fair user selection in the sequential aggregation process.

The comparison presented in

Table 5 clearly demonstrates the superior efficiency of the proposed scheme relative to state-of-the-art counterparts. Our scheme achieves the lowest computational cost at only 0.016 seconds, which is approximately 2.4 times faster than Das et al. [

25] (2024) and more than 250 times faster than Wong et al. [

24] (2023). This improvement stems primarily from the lightweight signing and aggregation design, which minimizes modular exponentiation and leverages parallelism across multiple users.

In terms of communication overhead, our scheme requires 14.4 Kbits, which remains moderate and practical for real-world deployment. Although slightly higher than Das et al. [

25] (10.75 Kbits), it is significantly lower than Wong et al. [

24] (46.34 Kbits). This small increase over Das et al. is justified by the inclusion of additional trust aggregation information that enhances security and verifiability without imposing significant bandwidth cost. The proposed scheme supports six concurrent signers, matching the configuration of Das et al. [

25], while outperforming Wong et al., which only supports four signers per aggregation round. The ability to handle a larger signing group improves scalability and overall system throughput.

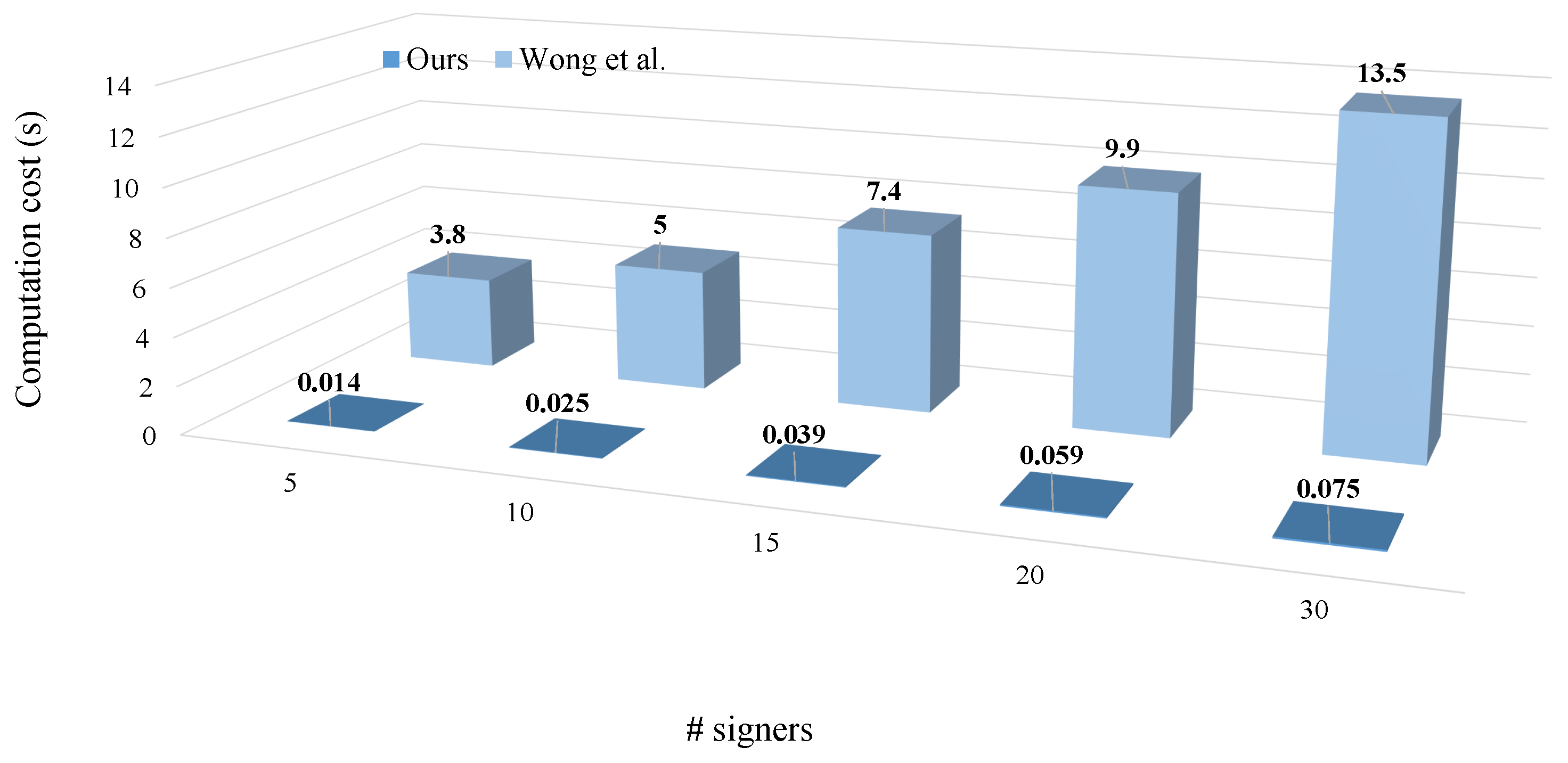

Figure 2 presents the evolution of computation cost as a function of the number of signers for the proposed scheme and the reference model of Wong et al. [

24]. The results show that our scheme exhibits a nearly linear and extremely low increase in computation time as the number of signers grows. Even when the signer count reaches thirty, the total computation cost remains below 0.08 s, confirming the lightweight and scalable design of our aggregation mechanism. In contrast, the computation cost of Wong et al.’s scheme increases sharply, rising from 3.8 s for five signers to 13.5 s for thirty signers. This sharp growth highlights the heavy per-user computational overhead of the existing model, which relies on multiple modular exponentiations and costly verification steps.

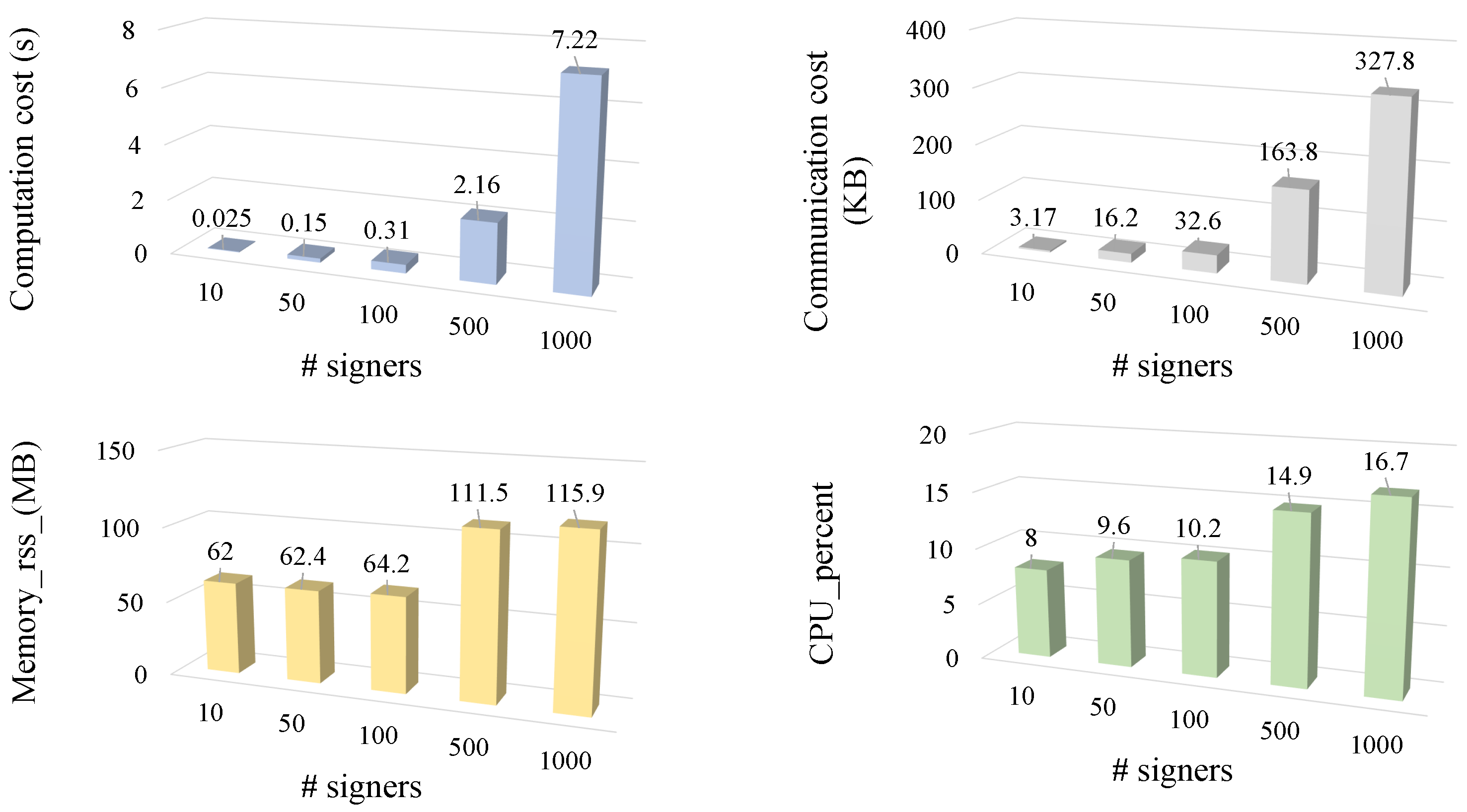

Figure 3 illustrates the scalability and resource utilization of the proposed scheme as the number of signers increases from 10 to 1000. The first subplot shows that the computation cost grows moderately with the number of signers, ranging from 0.025 s at 10 signers to 7.22 s at 1000 signers. This trend demonstrates that the computational complexity of our scheme remains lightweight even at large scales. The communication cost, shown in the second subplot, increases almost linearly with the number of participants, from 3.17 KB to 327.8 KB, reflecting the proportional exchange of cryptographic parameters during aggregation. The memory consumption remains stable across all scenarios, with values between 62 MB and 116 MB, indicating efficient memory management and no excessive overhead during concurrent operations. Similarly, CPU utilization grows gradually from 8% to 16.7%, confirming that the system maintains balanced workload distribution even as the network expands.

Regarding on-chain cost and latency considerations, when deployed on a blockchain such as Ethereum, the proposed aggregate signature scheme offers substantial advantages in terms of transaction size and latency compared to ring and threshold signatures. Ring signatures require publishing signature elements, leading to transaction sizes and gas costs that grow linearly with the number of signers. Threshold signatures reduce signature size but introduce coordination overhead for key generation and share reconstruction, which increases latency and protocol complexity. In contrast, our scheme commits only a single constant-size aggregate signature and aggregated public key to the blockchain, regardless of the number of contributors, thereby minimizing on-chain data, verification cost, and confirmation delay. This property is particularly beneficial for AI-driven collaborative settings, as it reduces both the gas consumption per transaction and the end-to-end consensus latency.

Proposal Limitations

Although the proposed scheme demonstrates strong performance and security guarantees, several practical limitations remain. First, the sequential execution mode introduces latency that grows linearly with the number of participating signers, which may impact responsiveness in large-scale deployments. Second, the SmartSelectUser function relies on accurate measurements of contextual parameters such as energy, distance, and network traffic; in adversarial or untrusted environments, these parameters may need to be verified through trusted attestation or cross-validation mechanisms. Third, while our evaluation includes simulated IoT settings and comprehensive computational analyses, a full implementation on heterogeneous or low-power devices remains a topic for future work. Finally, although the scheme achieves strong privacy and unlinkability, integrating accountability or selective traceability without compromising anonymity requires further investigation.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this article, we presented a privacy-preserving framework that integrates aggregate signatures with aggregated public keys for secure and verifiable collaboration in blockchain-based AI ecosystems. By combining ElGamal cryptography with the adaptive SmartSelectUser mechanism, the proposed scheme enables unlinkable and context-aware multi-party authentication of model updates or AI-driven decisions while maintaining strong privacy guarantees.

Theoretical analysis and empirical evaluation confirm that the framework is both lightweight and scalable. Compared with recent baseline schemes [

24,

25], our implementation achieves a computation cost of only 0.016 s per aggregation, moderate communication overhead of 14.4 Kbits, and low memory and CPU consumption, validating its suitability for resource-constrained and decentralized environments. The scalability experiments further demonstrate near-linear growth in cost up to 1000 signers, confirming the practicality of the design for large-scale deployments.

The protocol supports two execution modes: a parallel mode, suitable for high-throughput scenarios, and an asynchronous sequential mode, where signers are dynamically selected through the context-aware SmartSelectUser function. This dual-mode architecture provides flexibility between performance efficiency and adaptive resilience under heterogeneous network conditions.

Beyond the immediate scope of decentralized AI collaboration, the proposed framework opens several promising application avenues. In industrial settings, such as smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0 ecosystems, our scheme can enable secure and privacy-preserving exchange of machine learning model updates among factories, suppliers, and edge devices while reducing communication and verification overhead. In the medical domain, the framework can support FL across hospitals, laboratories, and diagnostic centers, allowing model training on sensitive patient data without exposing identities or raw records, thus aligning with GDPR and HIPAA compliance requirements. Future work includes developing lightweight implementations tailored for medical IoT sensors and edge devices, integrating secure hardware-based attestation for the SmartSelectUser mechanism, and investigating hybrid accountability models suitable for regulated environments.