1. Introduction

The rising demand to abandon non-reusable packaging in favour of sustainable and bio-based materials is noticeable in the global market. A worrying insight is that plastic films and packaging materials cause environmental issues upon disposal, and globally, only 9% of the plastic produced is recycled [

1]. This situation may be negatively influenced by the rising global population, leading to an increase in food production and packaging. The widespread use of single-use plastic significantly contributes to land and marine pollution, with microplastics being found in oceans, soil, and even foodstuffs [

2,

3]. These materials take hundreds of years to decompose while releasing harmful chemicals into ecosystems and posing risks to wildlife and human health. Moreover, the production of plastic heavily relies on the use of fossil fuels. Ninety-nine percent of polymers are produced from crude oil or natural gas [

4], contributing to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions throughout their lifecycle. As consumer awareness grows, industries are under pressure to transition towards circular packaging systems that prioritise reuse, recyclability, and composability. According to Lin et al. [

5], consumers are willing to adapt to sustainable packaging while concurrently believing that the responsibility of reducing plastic is primarily that of the manufacturers. This trend is caused by an increased awareness and focus on health, nutrition quality, and circular economy. Coherently, the packaging industry is facing an increased demand for innovative solutions to reduce waste as well. The main aspects that inspire innovation in package manufacturing are sustainability and active packaging solutions [

6]. Advances in biobased materials are shaping the future of packaging, although challenges like cost and durability remain. Therefore, an increasing number of researchers are focusing on creating alternatives to plastic packaging, which are biodegradable, edible, and produced from natural and sustainable ingredients.

Given the latest European Union’s waste framework directives, EU countries focus on preventing waste production and reusing waste materials. Nevertheless, waste recycling for intended use in packaging materials is not a new idea: the first polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle-to-bottle recycling plant in Europe was installed in 1998 [

7]. Currently, PET is a plastic type with one of the highest recycling rates [

8]. Other materials with high recycling rates are paper and cardboard. They have multiple applications in the packaging industry, such as takeaway boxes, cardboard packaging, and paper bags for loose products. Considering that the recycling market is constantly growing, there are constant innovations and improvements being made. Welle [

9] evaluated the possibility and safety of recycling polystyrene back into food packaging materials and established that such an approach has not been used industrially in Europe so far. However, it has the potential to be incorporated into refrigerated food packaging. Another major environmental concern is the volume of by-products created by the food industry [

10]. Agro-food waste is an unavoidable and problematic part of the food production system, as large quantities of waste are constantly produced, while almost all of it is discarded or used as animal feed [

11]. The waste is rich in bioactive compounds and has high nutritional value [

12]. However, when untreated and disposed of in landfill, they pose a significant risk of becoming ecological hazards. A major portion of food waste is converted into greenhouse gases, which have an enormous impact on global warming—up to 25 times bigger than that of carbon dioxide [

13]. Therefore, attempts to increase the utilisation of by-products are crucial to lower GHG emissions and minimise food waste. Their efficient use could be beneficial for the food packaging industry, as it is an opportunity to create edible films and pouches suitable for the containment of foodstuffs. Among others, fruit pomace powders have been used for such purposes. For example, Pakulska et al. [

14] evaluated the suitability of apple and blackcurrant pomace powders in the production of pectin-based packaging films. It was found that fruit pomaces improved several properties of pectin films, such as thickness, mechanical strength, and water vapour absorption. Another study found that films based on citrus peel powders had antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [

15].

Cocoa shells are the main by-product of cocoa (

Theobroma cacao L.), separated from the cotyledons during the pre-roasting process and after the roasting process [

16]. It is estimated to form 70–80% of the entire pod [

17]. Currently, most of the cocoa husk is returned to the soil and used as fertiliser, but it has significant economic potential. However, if it is untreated and left on the soil surface, it can cause black pod rot and big losses for the industry [

18]. This by-product can be fragmented and processed by micronisation into powders of different granulations. Cocoa waste (CW) has a strong cocoa aroma and flavour and a chocolate colour. According to Süfer et al. [

19], it contains low quantities of fat (below 3%) and a high fibre content (up to 65%). Cocoa powder does not show film-forming capacity. Thus, in the presented analysis, apple pectin (AP), also extracted from by-products, was used to obtain a continuous structure. In order to achieve elasticity and flexibility of films, glycerol was added as a plasticiser. Glycerol is considered a trihydric alcohol and is a viscous, clear, and odourless liquid. Pectin is a biodegradable polysaccharide which is often used as a base for edible films due to its cost efficiency and easy processing. It is considered a sustainable biopolymer, considering that it comes from natural sources such as the seeds, skin, and peels of fruits and vegetables [

20]. Pectin has a crystalline structure [

21] which makes it suitable for gelling, stabilising, and thickening products. These qualities cause pectin to be one of the most used biopolymers on the market [

22]. Additionally, pectin-based packaging films provide oxygen, carbon dioxide, and volatile barriers for foodstuffs [

23]. Pectin’s abundance in nature, as it is one of the most bountiful biodegradable polymers [

24], allows it to be used in the rapidly growing sector of novel, environmentally friendly packaging. The versatility of pectin allows it to be processed through various methods such as casting, extrusion, and spray drying [

25]. It is commonly used in active and smart packaging development. A review [

26] on pectin revealed that it has numerous applications in the production of packaging films and coatings. It was also found that blending pectin with plasticisers, different polymers, and cross-linking agents favourably impacts the properties of packaging films [

27]. The addition of active ingredients to pectin-based films, such as essential oils or plant extracts, can produce antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [

25]. It is also widely used in active coatings, and it is suitable for blending with lipids, other polysaccharides, proteins, and their derivatives [

28], allowing the films and coatings to be altered to desired properties. Moreover, smart packaging systems using pectin have been developed to monitor food freshness through pH-sensitive colour indicators and sensors that respond to spoilage-related compounds [

25].

Edible films and coatings are defined as a thin, continuous layer of edible material used as a coating or as a film placed between food components to provide a barrier to mass transfer [

29]. They can prevent the product from losing its quality by the formation of oxygen, oil, or moisture barriers. These materials are designed to be consumed along with the food product or safely biodegraded, thereby reducing packaging waste and reliance on petroleum-based resources. In the food industry, products such as instant coffee, sugar sachets, and nutritional powders are conventionally packed using plastic or aluminium-coated films. They are single-use and are typically disposed of after their contents have been poured into water. For such products, edible and water-soluble packs have revolutionary potential, as they do not require disposal and have pre-measured portions [

30]. The product, together with the sachet, can be placed in water or different liquids, dissolved, and consumed or composted. A comprehensive review by Demircan and Velioglu [

31] explored edible food packaging materials and highlighted their significance as well as future potential for a wide range of applications. This idea aligns with the circular economy approach, as the generated waste is limited and the packaging material is made from the food industry’s by-products. Moreover, CW pouches could potentially positively contribute to the sensory characteristics of the product [

32], as they have a pleasant chocolate aroma. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the possibility of using CW in the form of fragmented cocoa husk to produce edible packaging films as one of the actions to minimise waste in a circular economy approach. Microstructure, optical characteristics, wetting properties, barrier functionality, mechanical strength, chemical structure, antioxidant capacity, and thermal properties were investigated. The idea of using CW for improving the characteristics of pectin films holds promising prospects for the production of innovative edible food packaging.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The CW, which was a powder with a particle size of 10 µm, was supplied by Green Field Sp. z o.o. Sp. k. (Warsaw, Poland). Low methoxy apple pectin AMID AF 020—E (DE 27–32%, DA 18–23%) was purchased from Herbstreith & Fox KG Pektin-Fabriken (Neuenbuerg, Germany) and was used as a gelling agent. Glycerol (Avantor Performance Materials Poland S.A., Gliwice, Poland) was used as a plasticiser. Sodium chloride was purchased from Chempur (Piekary Śląskie, Poland) and was used for water vapour sorption kinetics evaluation. All reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Film Preparation

Aqueous film-forming solutions of AP at 5% (

w/

w) and CW, fine powder with a particle size of 10 µm, from 0 to 50% of pectin were prepared with the addition of glycerol as a plasticiser (50% of pectin).

Table 1 presents the detailed composition of the films. The solutions were stirred and heated at 60 °C for 15 min at 250 rpm using an RCT basic IKAMAG magnetic stirrer (IKA Poland, Warsaw, Poland) to obtain uniform film-forming solutions. Then, mixtures were cooled and poured onto Petri dishes in a controlled volume to obtain a similar thickness of 150 ± 10 µm. Afterwards, solutions underwent drying at 50 °C for 6 h to a constant moisture content using the SUP-65 WG laboratory dryer model (WAMED S.A., Warsaw, Poland). Dried films were removed from the Petri dishes. The films were stored at 25 °C and a relative humidity of 50% in a KBF 240 climate chamber (Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany) in an environment without access to light. The samples were dried at 30 °C and a pressure of 1.5 kPa for 48 h using a vacuum dryer Memmert V0 500 (Memmert GmbH + Co.KG, Schwabach, Germany) to reduce the moisture content before studying Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, thermal, and sorption properties. The dried samples were then kept in a desiccator on phosphorus pentoxide (P

2O

5).

2.3. Film Thickness

An electronic ProGage thickness tester (Thwing-Albert Instrument Company, West Berlin, NJ, USA) with an accuracy of 1 μm was used to determine the thickness of the samples. Each measurement was taken in at least 3 repetitions.

2.4. Microstructure

A digital microscope (VHX-X1 series) and laser confocal microscope (VK-X3000 series) (KEYENCE INTERNATIONAL (Mechelen, Belgium) NV/SA) were used to determine the sample microstructure. There was no specific preparation of the samples before microstructure observations.

2.5. Optical Properties

2.5.1. UV-VIS Transmittance

The UV-VIS transmittance (%) was measured in the range of wavelength 200–800 nm with an EVOLUTION 220 UV–visible spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) using the magnetic film adapter and Thermo INSIGHT software (version 2.5).

2.5.2. Colour

The colour of the films was measured in CIE

L*

a*

b* system using colorimeter CR-400 (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Before the measurement, a calibration white plate was used to adjust the instrument. The parameters studied were

L* from black (0) to white (100),

a* from green (-) to red (+), and

b* from blue (-) to yellow (+). The total colour difference (Δ

E) was calculated according to the following equation [

33]:

where Δ

L*, Δ

a*, and Δ

b* are the differences between the parameter corresponding to the colour of the sample and the parameter corresponding to the control films without the addition of CW. The results were recorded using SpectraMagic NK colour data software Version SM-S100w 3.10.0004. Ten repetitions were made for each type of film.

2.6. Wetting Properties

2.6.1. Water Content

The samples were dried at 105 °C to a constant mass in a laboratory dryer SUP 65 W/G (WAMED, Warsaw, Poland) in order to determine the water content. Each measurement took place in three replicates. The water content was calculated using the initial mass and the mass after drying using analytical balance (RADWAG PS 600/C/2, Radom, Poland). It was then used in the evaluation of water vapour sorption kinetics and isotherms.

2.6.2. Water Vapour Sorption Kinetics

To achieve a constant ambient relative humidity of 75% at 25 °C, a saturated sodium chloride (NaCl) solution was used. To measure the vapour sorption kinetics, samples of 50 ± 5 mg were cut into small pieces and weighed periodically using analytical balance (RADWAG PS 600/C/2, Radom, Poland). Measurements were carried out in three replicates at 25 ± 1 °C after 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h.

2.6.3. Water Vapour Sorption Isotherms

In order to determine the water vapour sorption isotherms, the Aquadyne DVS-2HT dynamic water vapour sorption analyser (Quantachrome Instruments by Anton Paar Sp. z o.o., Warsaw, Poland) was used. Three repetitions were made for each film. The samples were weighed to 20 ± 1 mg. Then, the samples were placed in a glass pan and subjected to a series of relative humidities (RHs) from 0 to 75%. Submerging took place until the sample reached equilibrium at 25 °C. The equilibrium criterion at each relative humidity was a percentage rate of mass change over time (dm/dt) ≤ 0.002% min−1 in 10 min. Microsoft Excel 2019 with DVS Standard Analysis software (version Air3) was used to analyse the experimental data points. To process the data, the latest version of OriginPro 8.0 software, Air3 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA), was used.

2.7. Water Contact Angle

The water contact angle was measured using the sessile drop technique with a goniometer OCA 25 (DataPhysics Instruments GmbH, Filderstadt, Germany). The contact angle was measured after the release of a 10 μL drop of distilled water at a speed of 10 μL/s on the surface of the films. For each film, three repetitions were made. The SCA20_U software (version 5.0.37) recorded the results.

2.8. Barrier Properties

2.8.1. Water Vapour Permeability

A gravimetric method was used based on a standard ASTM E96 method [

34] using Mater Cup FX-3180 equipment (Textest AG, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland). Three samples were cut from each film, and their thickness was measured. The samples were placed between two rubber-based rings on top of three glass cells containing distilled water, using a relative humidity gradient of 50 to 100%. The water vapour transmission (×10

−10 g/m·Pa·s) was calculated by the apparatus, using the mass change in the cup due to evaporation, the film’s area, and the measurement time.

2.8.2. Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Permeability

Oxygen permeability was determined using a C130 gas permeability test system (Labthink Instruments Co., Ltd., Jinan, China). Circles of 12 cm in diameter were cut from the samples, and the thickness of the permeation area was measured. Then, they were placed on a filter, and a vacuum was applied inside the system. Oxygen or carbon dioxide was then diffused through the film into a cell, where the amount of gas was determined by the manometric method, according to ASTM D1434-82 [

35]. The conditions of the analysis were 22 ± 1 °C and 35 ± 5% relative humidity.

2.9. Mechanical Properties

A TA-XT2i texture analyser (Stable Microsystems, Haslemere, UK), via the standard ASTM D882 method [

36], was used to determine the tensile strength (

TS) and elongation at break (

E) of the films. In order to determine said properties, the films of 100 × 25 mm were stretched at a rate of 1 mm/s until breakage, with an initial separation distance of 25 mm.

2.10. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

A Cary-630 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Cary, NC, USA) was used to determine the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) of the films using the total attenuated reflection (ATR) technique. The samples were analysed, and the spectra were recorded in the absorption range of 4000–650 cm–1 at a resolution of 4 cm–1. Each spectrum was an average of 32 interferograms and was presented as a dependence of the absorbance on the wavenumber.

2.11. Antioxidant Properties

Antioxidants can be defined as substances that oppose the oxidation process by neutralising reactive species such as free radicals, thereby preventing or slowing oxidative damage to molecules like lipids, proteins, and vitamins [

37]. They act as reducing agents that limit oxidative reactions in biological systems. Oxidation can lead to spoilage, loss of nutrients, and changes in sensory qualities like the flavour and colour of foodstuffs. Therefore, food packaging materials with antioxidant properties could potentially extend the shelf-life of food products [

38]. The performed analysis was based on the method described by Kozakiewicz et al. [

39].

The free radical scavenging activity of ABTS was measured using a solution of 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiozoline-6)-sulphonic acid (ABTS). It was prepared by dissolving 1 mL of ABTS in 100 mL of ethanol. The obtained solution had an absorbance of between 0.680 and 0.720. Small pieces (4 × 0.5 cm) of the film samples were submerged in 5 mL of the diluted solution and vortexed. The blank was made without the film samples. The solutions were left in darkness for 30 min. Then, they were vortexed again, and the absorbance of the samples was measured with an EVOLUTION 220 UV–visible light spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) at 734 nm in order to determine the antioxidant activity (AA) as % inhibition.

The free radical scavenging activity of DPPH was measured using a solution of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). In order to obtain the solution, 18 mL of the saturated solution was dissolved in 100 mL of ethanol. The obtained solution had an absorbance of between 0.680 and 0.720. Small pieces (4 × 0.5 cm) of the film samples were submerged in 5 mL of the diluted solution and vortexed. The solutions were left in darkness for 30 min. Then, they were vortexed again, and the absorbance of the samples was measured with an EVOLUTION 220 UV–visible spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) at 515 nm.

The antioxidant activity as

%inhibition was determined from the same equation as used for the ABTS calculations.

2.12. Thermal Analysis

Thermal properties are primarily understood to determine a material’s thermal stability and compositional characteristics. They are especially important in food packaging materials, as these materials must withstand the rigours of foodstuff transport and storage [

40]. The thermal stability was assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and derivative thermogravimetry (dTG). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted to understand the change in the mass of material as it is heated, cooled, or held at a specific temperature over time. The derivative thermogravimetry (dTG) was conducted to plot the first derivative curve in accordance with time or temperature, to understand the weight loss and change in temperature of our pectin-based films.

A thermal analyser (Mettler Toledo, Warsaw, Poland) was used to conduct the thermogravimetric analysis. The thermal stability and degradation of the samples were assessed. Samples (5 mg) underwent heating at a rate of 5 °C/min, transitioning from 30 to 600 °C within a nitrogen atmosphere (N2 flow rate set at 50 mL/min). TGA and DTG curves were derived from the differential TGA values.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Statistica 13.3 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) was used to perform a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Tukey’s test to detect significant differences in the properties of the samples. The significance level used was 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Film Description

The developed films had between 5% and 100% CW relative to AP; however, films above 50% of CW were too brittle for further evaluation and use as continuous packaging films. This was attributed to the tough structure and uneven surface. All films with the addition of up to 50% CW had a smooth texture with good appearance and were shiny, flexible, and easily peelable from the casting Petri dishes. However, the control films (AP) were hard to peel and very elastic. Films with 30% CW and above were of a uniform dark brown colour. Films with a lower percentage of CW (5–20%) were not unicoloured; there were darker particles visible on a light brown surface. Films without CW were almost transparent with a slight yellow tint. The films with CW addition had a chocolate aroma; the control films did not.

The obtained pouches were found to be sealable and able to withstand being used as food packaging. However, films with a percentage of CW above 40% were harder to seal than those with lower CW content, suggesting that AP_20CW and AP_30CW are the most suitable for their intended use. Analyzed films and pouches were presented in

Figure 1.

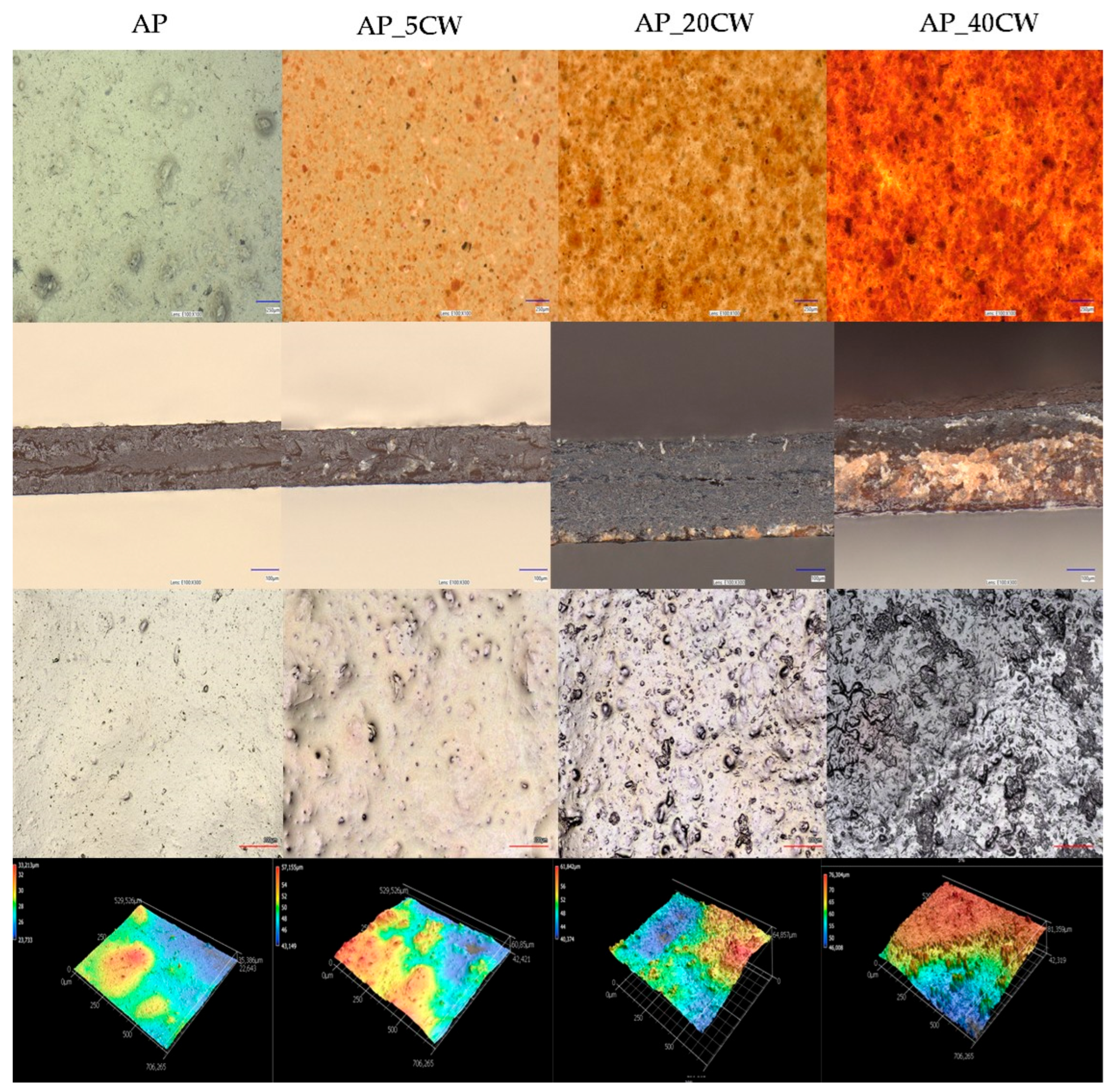

3.2. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Microstructure of Pectin Packaging Films

A microstructure evaluation of the films was made in order to assess the sample morphology and homogeneity [

41]. The evaluation showed that the incorporation of CW into pectin-based films significantly altered their microstructure (

Figure 2). Notably, the presence of CW increases structural heterogeneity and surface roughness. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations demonstrate that CW components tend to migrate towards the surface of the film during the drying process, promoting the development of granular textures and topographical irregularities [

42].

Significant changes in the appearance of the films were observed at different concentrations of CW, varying from 5% to 40%. The addition of just 5% CW caused the films to exhibit particle dispersion and slight surface roughness, despite their relatively continuous and compact structure. This was an indicator of good compatibility between CW and AP at low concentrations. An increased surface roughness and heterogeneity were noted in films with 20% CW.

Table 2 presents the following surface roughness parameters of films: average roughness (

Ra), root-mean-squared roughness (

Rq), maximum peak height (

Rp), and peak valley (

Rz). The average roughness (

Ra) of the films was in the range of 0.276–0.506 µm. In films with CW concentrations up to 30%, there is a noticeable increase in the roughness compared to the control films. In films with 40% of CW, there is a roughness reduction, which is caused by structural changes in films with 40% of CW. AP_40CW has high irregularity and heterogeneity; particle accumulation was noted in the bottom part of the film. Lower values of roughness for film containing 40% of CW correspond with the location of particles in the lower surface of the film matrix. This may be attributed to the aggregation or coalescence of particles that may occur in film-forming solutions during the drying process. When the addition of cocoa waste was higher than 40%, the separation of phases was observed, thus leading to the destabilisation of the film structure.

The cross-section of films showed an irregular surface and high variation, which further explains the relationship between CW and AP at moderate concentrations. Films with a higher concentration of CW (AP_40CW) demonstrated the most disruptiveness to the structure, causing the surface to look dark and coarse with large pores and numerous cracks. While the cross-section showed a brittle surface due to the deposition of CW on the surface during drying, it also showed extreme surface irregularities with sharp peaks.

Overall, the results demonstrated that CW incorporation disrupted the structural uniformity of pectin. While the lower concentration integrated well and maintained the integrity of the films, the higher concentration (40%) led to extreme roughness and an irregular surface, which may compromise the mechanical strength and barrier properties of the films.

3.3. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Optical Properties of Pectin Packaging Films

The optical properties of AP films, especially within the ultraviolet–visible (UV-VIS) spectrum, were significantly influenced by the incorporation of CW.

Figure 3 presents the UV-VIS spectra transmittance of the CW films. The recorded transmittance values indicated that increasing the CW concentration from 5 to 50% resulted in a progressive decline in transmittance across the 200–750 nm range. Films without CW displayed the highest transmittance values across the whole wavelength range of 200–750 nm. This phenomenon is predominantly ascribed to the presence of naturally occurring phenolic constituents within CW, which inherently possess ultraviolet radiation-absorbing capabilities. Additionally, these compounds contributed to increased film opacity by scattering visible light due to their particulate nature and their interaction with the pectin matrix. As a result, films that included more CW had a greater ability to shield against UV light, making them appropriate for active food packaging applications where photodegradation prevention is essential. The bioactive component profile of the waste material was consistent with the rise in absorbance at greater levels of CW, demonstrating its functional contribution to the optical modification of the biopolymer films [

43].

Colour is an important optical property as it influences how the products appeal to potential consumers. In order to estimate the colour of the prepared films, the L*, a*, and b* parameters were measured, and the total colour difference between the films was calculated.

Table 3 shows the effect of CW on the colour of the films. Samples with CW addition were visually brown; the control film was yellow. The incorporation of CW significantly decreased the

L* parameter—from 82.58 in AP to 28.58 in AP_50CW—indicating a darker colour in foils with higher CW concentration. The

a* parameter indicates closeness to red (above 0) or green (below 0). The incorporation of CW significantly increased the

a* value in films with CW addition, from 0.49 in AP to 20.17 in 20% CW. In higher concentrations, a decrease was observed: 15.85, 7.55, and 5.37, respectively. The

b* parameter indicates closeness to yellow (above 0) or blue (below 0). The addition of 5% and 10% of CW caused an increase in the

b* value, indicating yellow tones. However, higher concentrations caused a significant decrease. Samples with 50% CW showed a negative value of −0.43, which indicates a colour closer to blue. Overall, the AP films had bright yellow tones. The addition of CW caused the reduction of brightness and red-yellow tones, with the exception of CW 50%, which indicated red-blue tones.

Total colour difference (ΔE) is defined as the discrepancy between the tested sample and the reference sample. The discrepancy between CW samples and the control (AP) was measured. Generally, values above 1 mean deviations from the standard. The calculated total colour difference (ΔE) was in a broad spectrum of 26.52–60.61. Significant differences were observed when comparing CW samples to the control, especially in samples with the highest concentrations. The colour difference between the control and CW 5–20% samples was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The most similar films were the ones with 30–50% of CW. Increasing the concentration of CW increased the total colour difference.

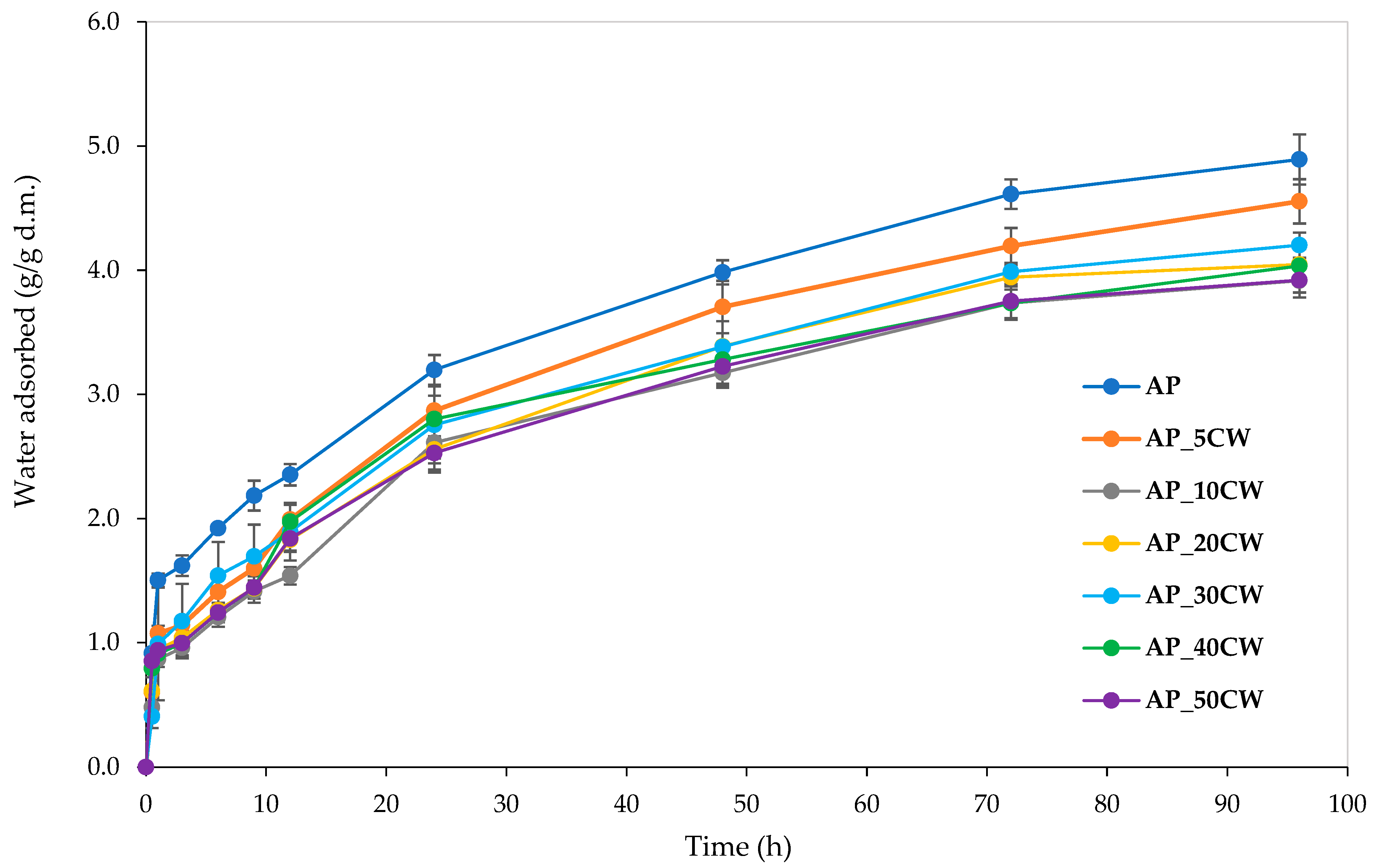

3.4. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Water Vapour Sorption Properties of Pectin Packaging Films

Water vapour sorption kinetics is an important indicator of the amount of moisture a product absorbs. Information about moisture absorbance capacity is especially crucial for food contact materials, as excessive moisture can negatively impact physical properties and microbial stability [

44]. Generally, this parameter depends on parameters such as sample type, humidity, and time. The analysis of edible films incorporated with CW clearly shows that increasing the CW concentration causes lower moisture absorbance over 96 h.

Figure 4 displays the determined water vapour sorption kinetics of the films.

The highest water vapour absorption throughout the whole process was observed in the samples without the incorporation of CW. The addition of CW decreased the sorption rate; the greater the cocoa addition, the smaller the water vapour absorption. This is probably due to the composition of CW. The main components of CW are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [

45]. Lignin is responsible for the hydrophobic properties of lignocellulosic biomass [

46], which possibly causes films with CW incorporation to have lowered water vapour sorption. Notably, all films displayed water vapour sorption kinetic curves of similar shapes, indicating uniform sorption kinetics and suggesting consistent compositional characteristics across samples.

Water vapour sorption isotherms provide information about the behaviour of a product towards the humidity in the environment; it is predominantly the relationship between water activity and water content at a given temperature [

47].

Figure 5 presents water vapour sorption isotherms for pectin films incorporated with different concentrations of CW. There is a clear influence of the amount of CW added into films on the equilibrium water content observed. It was observed that all samples absorbed small amounts of water in lower water activity and higher amounts of water in higher water activity. Notably, the curves of all films were of type III van der Waals sorption isotherm shape [

48]. This type of isotherm is characteristic of high-sugar-content food [

49]. Sugars from foods absorb relatively little water at low relative humidities [

50].

A correlation was found between the concentration of CW added and the water absorption. The greater the addition, the lower the absorption. Similar conclusions were drawn while observing the water vapour sorption kinetics of the analysed films. Generally, for water activity below 0.4, the increase in the amount of water absorbed was gradual and steady; for higher water activity, the increase was sharper and rapid. Noticeable differences between the moisture values were observed for aw > 0.5.

3.5. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Water Contact Angle of Pectin Packaging Films

The contact angle of a water droplet applied on the films was analysed in order to determine the wettability degree of the tested surface.

Table 4 shows the contact angles and photographs of the water droplets.

This indicates the hydrophilic (θ < 90°) or hydrophobic (θ > 90°) character of the sample [

51]. An increase in contact angle means higher hydrophobicity. This examination was conducted on both sides of each film. The support side was the one that was touching the plates during casting and drying, while the air side was on the top. The results ranged from 38.25 to 73.23°. Generally, for each type of film, the air sides had a higher contact angle. AP_C30W and AP_40CW were an exception; in those cases, the support sides had a slightly higher contact angle. The highest wettability, 63.82, was observed for the air side of AP_5CW. The water contact angle analysis indicated the hydrophobic nature of the films. The concentration of CW affects the water contact angle of the samples. Notably, the contact angle can be influenced by the structure and homogeneity of the films. This was noticed in samples with concentrations of cocoa of 30% or above.

3.6. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Barrier Properties of Pectin Packaging Films

Water vapour permeability is an important parameter that indicates the amount of water vapour that can penetrate a given material in a given time [

52]. It is especially crucial for food packaging materials, as they are supposed to prevent the exchange of moisture between the foodstuff and the environment [

53].

Table 5 presents the water vapour, oxygen, and carbon permeability of pectin films with the incorporation of CW.

The water vapour permeability values ranged from 8.79 to 11.0 × 10

−10 g/m·Pa·s. Samples with the addition of 5% of CW (AP_5CW) were characterised by the lowest permeability, while samples with the highest concentration of CW (AP_40CW, AP_50CW) were characterised by the highest. The higher water vapour permeability of the films containing 40 and 50% of CW in comparison to the control samples and films with 5–30% of CW was probably due to their non-homogeneous structure and surface. The tendency of non-homogeneous edible films with irregular surfaces to have higher permeability than homogenous films has been observed previously. For example, by comparing methylcellulose films that were either emulsified, resulting in an irregular surface, or laminated, resulting in a regular, smooth surface, this study demonstrated that laminated films had greater barrier properties and significantly lower water vapour permeability [

54].

Oxygen permeability showed a tendency: the higher the CW concentration, the greater the permeability. The oxygen permeability values ranged from 5.53 × 10

−16 g/m·Pa·s in the control samples to 19.52 × 10

−16 g/m·Pa·s in samples with 50% CW. An analogous trend was observed in the case of carbon dioxide permeability. Carbon dioxide permeability values were the lowest (9.62 × 10

−16 g/m·Pa·s) in the control sample and highest in AP_CW50 (40.82 × 10

−16 g/m·Pa·s). This is probably due to the changes in structure that facilitated the migration of carbon dioxide.

Figure 2 reveals the discontinuous phase in films containing CW, thus resulting in open spaces affecting the gas migration.

The water vapour permeability values of the cocoa films in this study were higher than for polyethylene (PET) films (5.803–22.921 × 10

−14 g/m·Pa·s), and the oxygen permeability values of the CW films were lower than for PET (0.098–0.494 × 10

−7 g/m·Pa·s) [

55]. Overall, this suggests that CW films provide a good oxygen barrier in comparison to polyethylene and can be used to protect foodstuffs against oxidation. However, it is likely that differences occurred in the measurement methods and conditions, indicating that more research is needed to evaluate the barrier properties of developed films in different conditions.

3.7. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Mechanical Properties of Pectin Packaging Films

Tensile strength and elongation at break are considered to be the basic parameters of the mechanical properties of materials. These parameters are crucial in packaging manufacturing as they provide information on whether the material is mechanically strong enough to withstand the handling of the product without breaking [

56]. The tensile strength (

TS) and elongation at break (

EAB) of the developed edible films are presented in

Table 6.

The results for TS were in the range of 7.28–19.14 MPa. The lowest TS was observed for the control samples (AP), and the highest in the sample with the highest concentration of CW (AP_50CW). Generally, the greater the CW addition, the higher the tensile strength of the films; thus, the addition of CW significantly affected the mechanical resistance of the pectin films. Similar findings were reported by Sanyang et al. [

57], whose study utilised cocoa pod husk (CPH) as a filler in polylactic acid (PLA) biocomposite films. The tensile strength measurement of films with the addition of 5%, 10%, and 15% of CPH was conducted. It was found that the TS of films with the filler was higher than that of the control PLA films, proving that CW has the potential to increase the mechanical strength of bio-based films.

Elongation at break indicates the maximum extent to which a material can be stretched without breaking. The values are shown in

Table 5 and range from 17.41 to 27.46%. The highest EAB was measured in AP_20CW, and the lowest in AP_50CW. Films with the addition of CW in the range of 5–30% presented an improvement in EAB with respect to the control pectin films. AP_40CW and AP_50CW behaved differently, with lower elongation at break values than other films. This was possibly caused by their non-homogeneous structure and uneven particle distribution. The measured EAB values were similar to those obtained by Osuna et al. [

58] in pectin films enriched with

Apis mellifera honey and/or propolis extract. However, the values were also much lower than those for films made from apple pectin, soy protein isolate, and punicalagin, which ranged from 33.78 to 169.35% [

59].

Improving tensile strength with simultaneous lowering of the elongation at break values by the addition of fruit by-products has been studied before. Pakulska et al. [

14] found that the incorporation of blackcurrant and apple pomace into pectin-based films caused higher tensile strength and lower elongation at break than films without pomace.

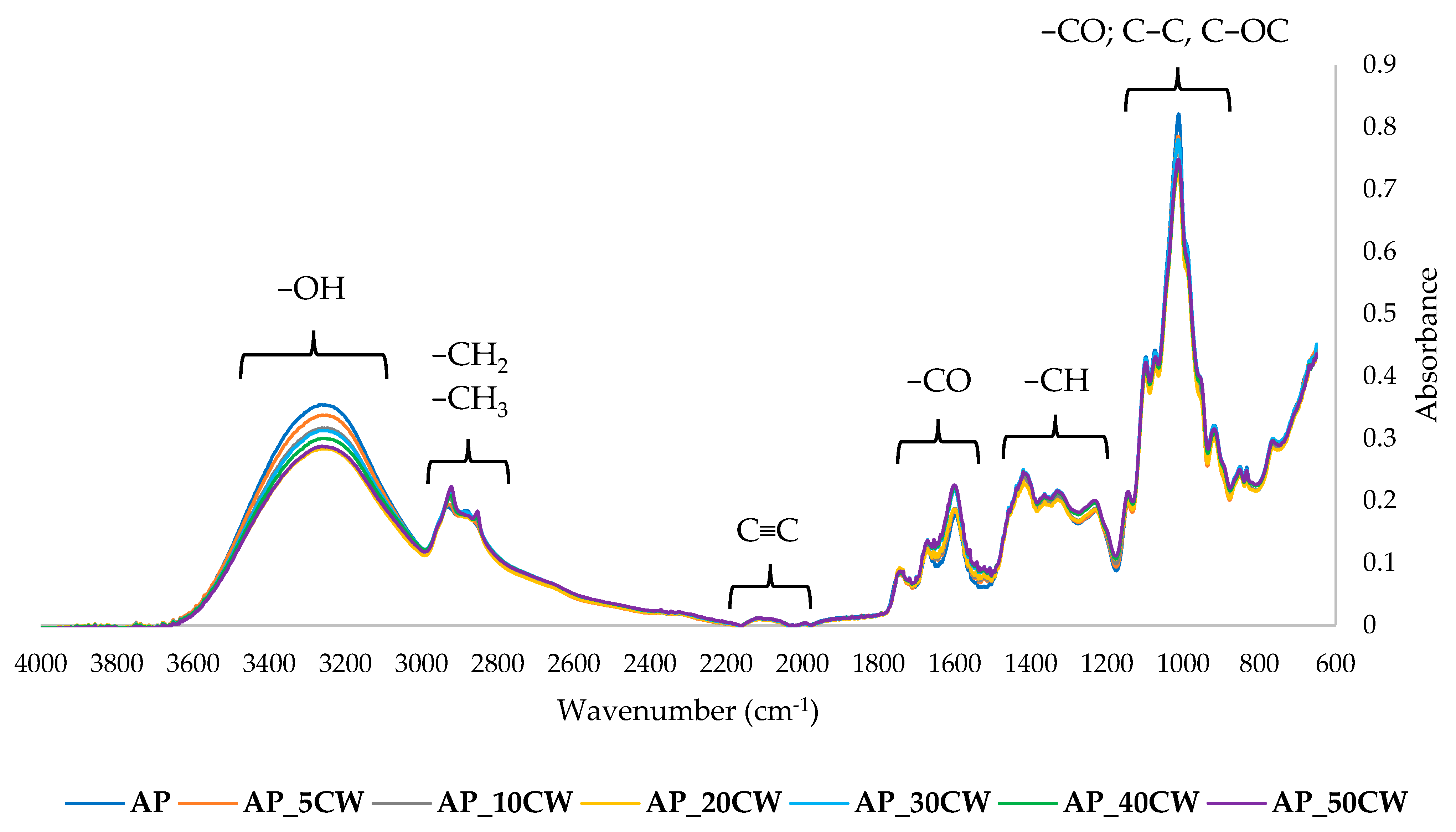

3.8. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Chemical Structure of Pectin Packaging Films

The chemical structure of the films was examined by the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) method. It identifies functional groups in samples by identifying specific wavelengths at which the IR radiation is absorbed [

60]. The results of the FT-IR analysis of edible packaging films based on AP films and with the addition of CW are presented in

Figure 6.

At a range of 3600–3000 cm

−1, a broad band was observed, indicating the presence of hydroxyl groups [

61]. At 3000–2900 cm

−1, stretching bands of C-H aliphatic groups could be observed [

62]. At 2100–2270, the alkin group (C≡C) is observed, but with a low band. A sharp band at 1800–1500 cm

−1 indicates the presence of a carbonyl group (C=O) [

63]. In the fingerprint region, bands at 1450–1200 cm

−1 and at 1100–800 cm

−1 were observed. The first band suggests the presence of methane groups (-CH). The last band indicates the presence of carbohydrates and stretching of their C-O and C-C bonds.

3.9. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Antioxidant Properties of Pectin Packaging Films

Table 7 presents the antioxidant properties of food packaging films based on AP and CW. The results of this analysis showed that the sample without CW was characterised by the lowest antioxidant activity in ABTS as well as DPPH tests, with values of 78.22 and 66.77%. The highest antioxidant activity was present in samples with the highest CW addition (AP_50CW) at values of 95.95% in the ABTS test and 85.21% in the DPPH test. Generally, the introduction of CW into the films caused a significant increase in their antioxidant activity. The greater the amount of CW, the greater the antioxidant activity. The ability of CW and cocoa products to increase antioxidant activity has been noted previously. The addition of cocoa powder to cassava mash increased antioxidant activity in the DPPH test from 45.02% (cassava and water blend) to 58.31% (cassava, water, and cocoa powder blend) [

64]. In a review on cocoa bean shell, Rojo-Poveda et al. [

65] found that cocoa by-products are widely used in the food industry for the production of bioplastics in order to give them antioxidant properties.

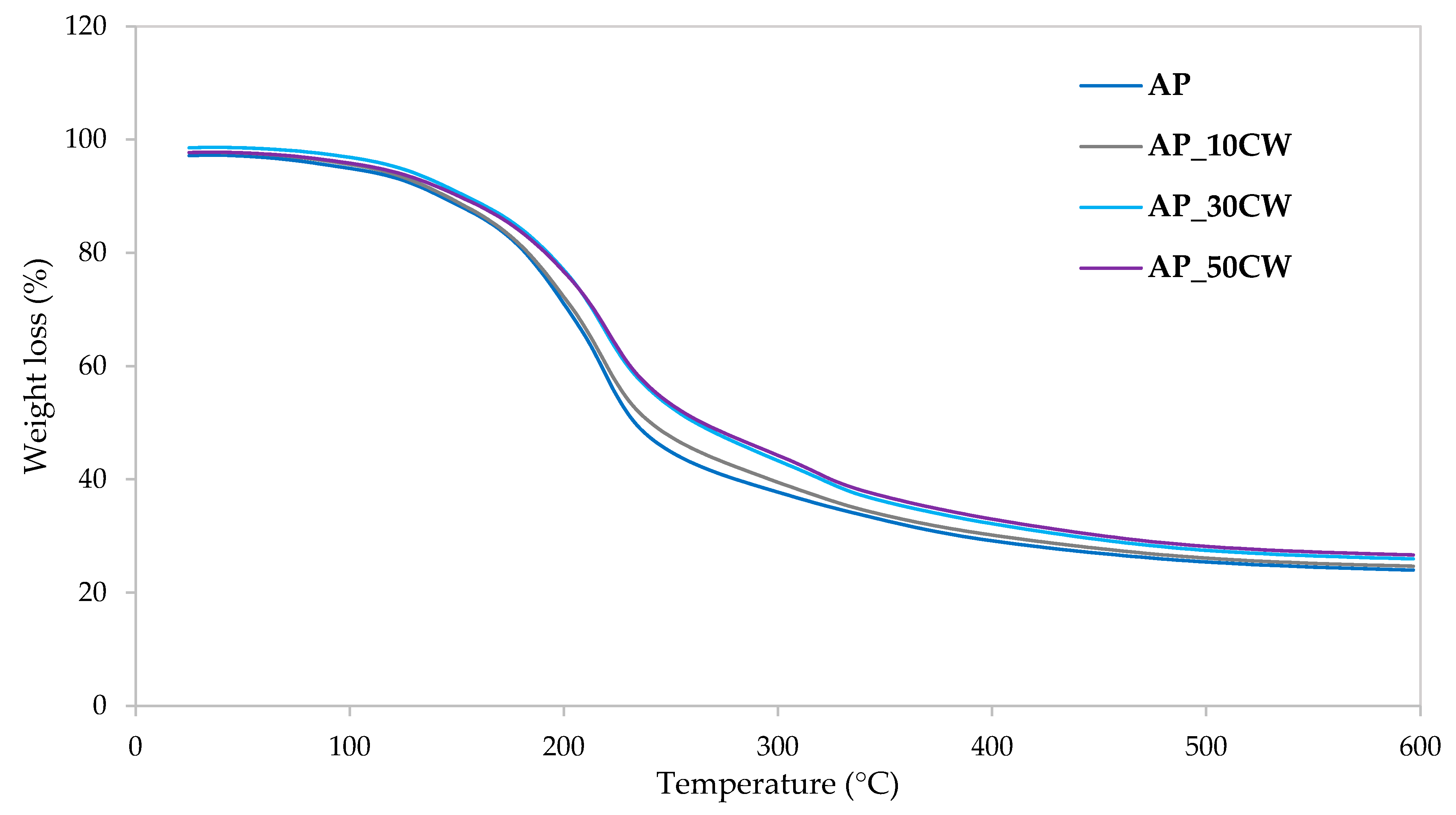

3.10. The Effect of Cocoa Waste on the Thermal Properties of Pectin Packaging Films

Figure 7 illustrates the weight loss kinetics during the thermal degradation of packaging films, as derived from thermogravimetric analysis. The data show how these films respond to increasing temperatures over time, highlighting the rate of weight loss as they undergo thermal decomposition. As the temperature increases, more significant weight loss occurs, indicating the evaporation of moisture and the degradation of the polymer structure. The temperature at which this occurs provides insights into the thermal stability of the films. The decomposition occurred similarly in all tested samples; however, the figure revealed minor differences in thermal stability and decomposition rates. Accordingly,

Table 8 shows the peak decomposition temperature at each identified stage and the percentage of disintegrated material. The total mass loss observed for the control samples (AP) was approximately 76.15%, while the CW concentrations resulted in decreased values ranging from 73.44% to 75.49%. This reduction in mass loss indicates that the films have greater thermal stability and resistance to decomposition or loss of volatiles within a given temperature range.

In the first (0–100 °C) and second (100–160 °C) stages, initial weight loss due to moisture evaporation and light volatile release was observed, exhibiting the effects of increasing CW, causing a decrease in weight loss. For AP films, the losses were 5.10% (first stage) and 8.36% (second stage), while the films with 50% CW had losses of 3.15% and 8.01% in the same stages. This means that adding CW to AP films increases interactions within the polymer, causing enhanced matrix cohesion; the film’s polymer chains are held together more strongly, making it harder for water molecules to penetrate or loosen the network. There is a lower affinity for water as stronger interactions reduce the sites where water can attach (bound water).

The third stage (160–280 °C) is when decomposition occurs at a slightly higher temperature with reduced total weight loss as the CW percentage increases (46.55% in AP to 38.58% in AP_50CW). This indicates that increasing the concentration improves thermal stability, and the reduction in weight loss means that less material is decomposing or volatilising at this stage. The CW reinforces the film structure, causing the polymer matrix to degrade more slowly and to a lesser extent during the main decomposition stage. This is a common indicator of enhanced material thermal resistance and improved durability against heat exposure.

In the fourth stage, AP/CW films lose more weight as the CW content rises (from 16.10% to 24.42%). This may be attributed to a higher organic fraction or more efficient combustion in films with CW, consistent with the enhanced carbonisation or different degradation pathways seen in pectin films reinforced with inorganic/organic phases.

The introduction of CW into AP-based films favourably modifies their thermal stability, as evidenced by lower and delayed mass loss in early and main decomposition stages. The interaction between AP and CW enhances the structural integrity of the films, but also shifts the complete decomposition process, as similarly reported for pectin films reinforced with extracts.