Framework, Implementation, and User Experience Aspects of Driver Monitoring: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Dual bibliographic analyses: This study goes beyond other reviews that usually provide just one bibliometric analysis by performing two separate bibliographic analyses at different stages of the document selection process. This dual approach not only enhances the reliability of the review but also provides a deeper insight into the evolution of the DMS field throughout the systematic review process.

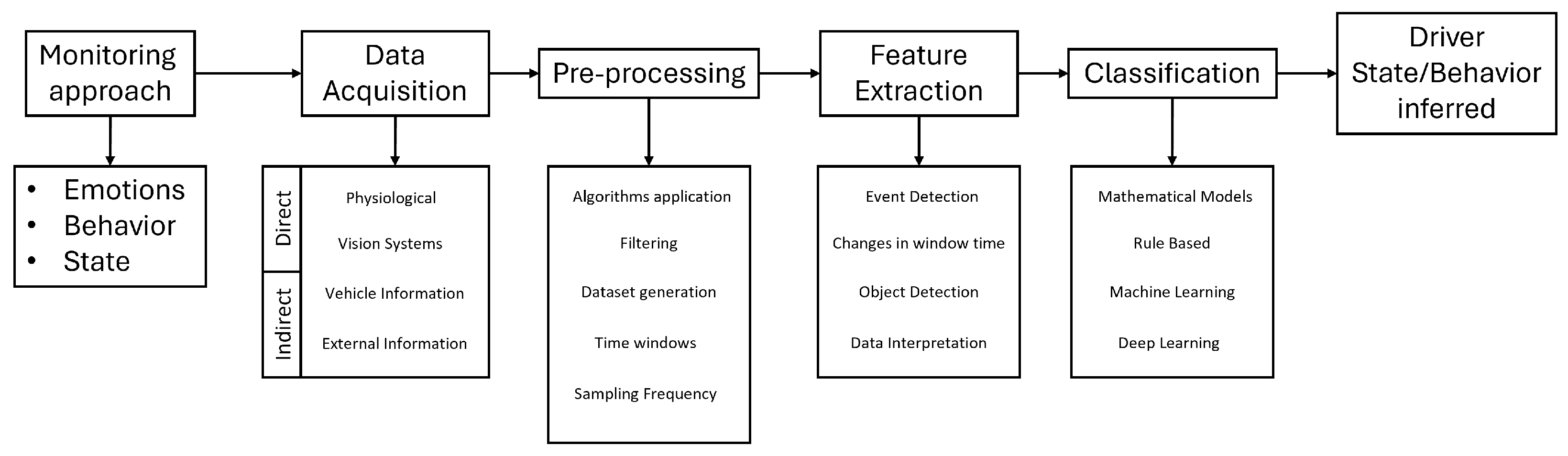

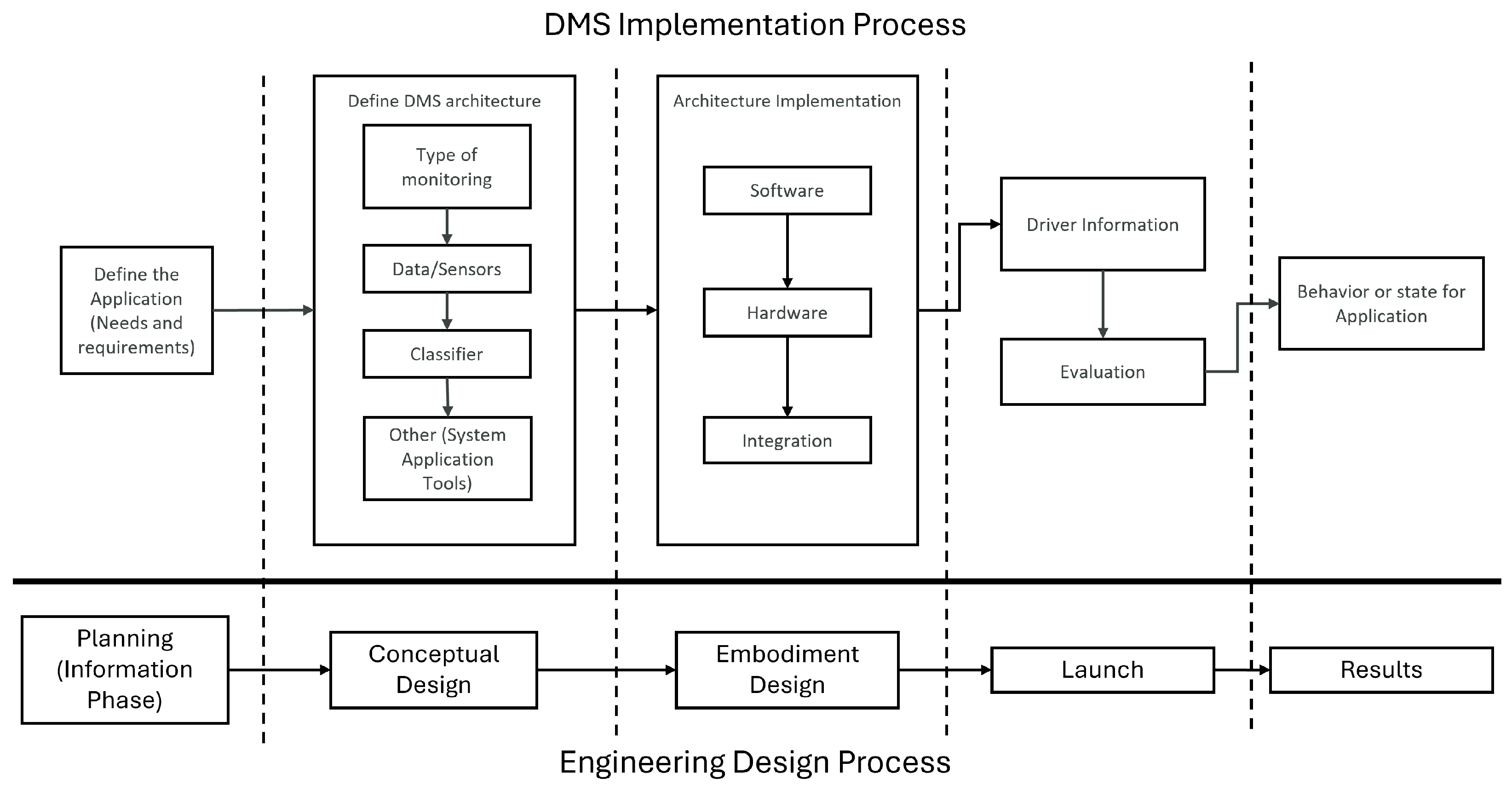

- Framework and implementation diagrams: In addition to summarizing the literature, we introduce two original diagrams, one capturing the conceptual framework of DMS and another depicting its implementation process, supported by an engineering design process.

- User Experience perspective: While existing reviews typically emphasize technical components (e.g., sensors, algorithms, detection accuracy), this work highlights the underexplored dimension of UX. By discussing its relevance and implications, we broaden the scope of the field beyond system performance, acknowledging the human-centered factors essential for real-world adoption and long-term acceptance.

- Comprehensive dataset synthesis: To support reproducibility and future research, this review compiles an extensive table of the datasets identified, something that prior works often mention only superficially or in scattered form. This consolidated resource serves as a practical reference point for researchers, enabling more efficient dataset selection and comparative studies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions

- What are the approaches in the literature on the development and integration of driver monitoring systems?

- How has user experience been addressed in the design, evaluation, and implementation of driver monitoring systems?

- What challenges and areas of opportunity exist in the state of the art regarding driver monitoring and user experience?

2.2. Hypothesis

2.3. Keywords

2.4. Research Definition

- “Driver Monitoring” AND “User Experience”

- (“Driver Emotions” OR “Driver Behavior” OR “Driver State”) AND “Driver Monitoring”

- (“Behavioral Research” OR “Driving Monitoring”) AND “User Experience” AND “Driving Simulator”

- (“Driver behavior” OR “Driver emotions” OR “Driver state”) AND “User experience”

- “Driving Simulator” AND “Driver Monitoring”

2.5. Search Results

3. Results

3.1. Initial Bibliographic Analysis

- •Red Cluster: This group is centered on driver monitoring and driver monitoring systems, directly associated with states such as sleepiness, road safety, and driver fatigue. These connections underscore road safety as the primary driver of research in this domain. The cluster also highlights the most widely applied tools and methodologies in the field, including neural networks, computer vision, eye tracking, and facial recognition, which constitute the technological foundation of modern monitoring approaches.

- •Green Cluster: This cluster emphasizes driver behavior and driving performance, reflecting the critical role of the human factor in both autonomous vehicle research and monitoring systems. The relationship here is bidirectional: while these technologies aim to improve performance and safety, they simultaneously influence driver behavior and workload. Hence, their integration must be carefully managed to ensure acceptance and avoid unintended negative effects.

- •Purple Cluster: This cluster aligns with transportation and road safety, incorporating elements such as road monitoring, sensor technologies, and connections to driver monitoring and behavior. It reflects how advancements in intelligent vehicle systems and smart infrastructure are increasingly being leveraged for accident prevention and enhanced mobility safety.

- •Blue Cluster: This group focuses on autonomous vehicles, highlighting the significance of driver monitoring in the context of different levels of autonomy. Research here stresses the continued responsibility of the user to supervise vehicle actions and maintain readiness to intervene, emphasizing the importance of human oversight in semi-automated driving.

- •Yellow Cluster: This cluster centers on the use of driving simulators, which, when combined with monitoring technologies, serve diverse purposes, such as analyzing the impact of autonomous vehicles on drivers, identifying risk factors in real-time driving, assessing user experience, and supporting iterative research and system development.

- •Light Blue Cluster: This cluster focuses on behavioral research, with a particular emphasis on the connection between driver behavior and monitoring technologies. A key theme is the development of HMIs, where monitoring data informs the design of interaction systems that enhance usability, acceptance, and overall user experience.

3.2. Second Bibliographic Analysis

3.3. Final Analysis

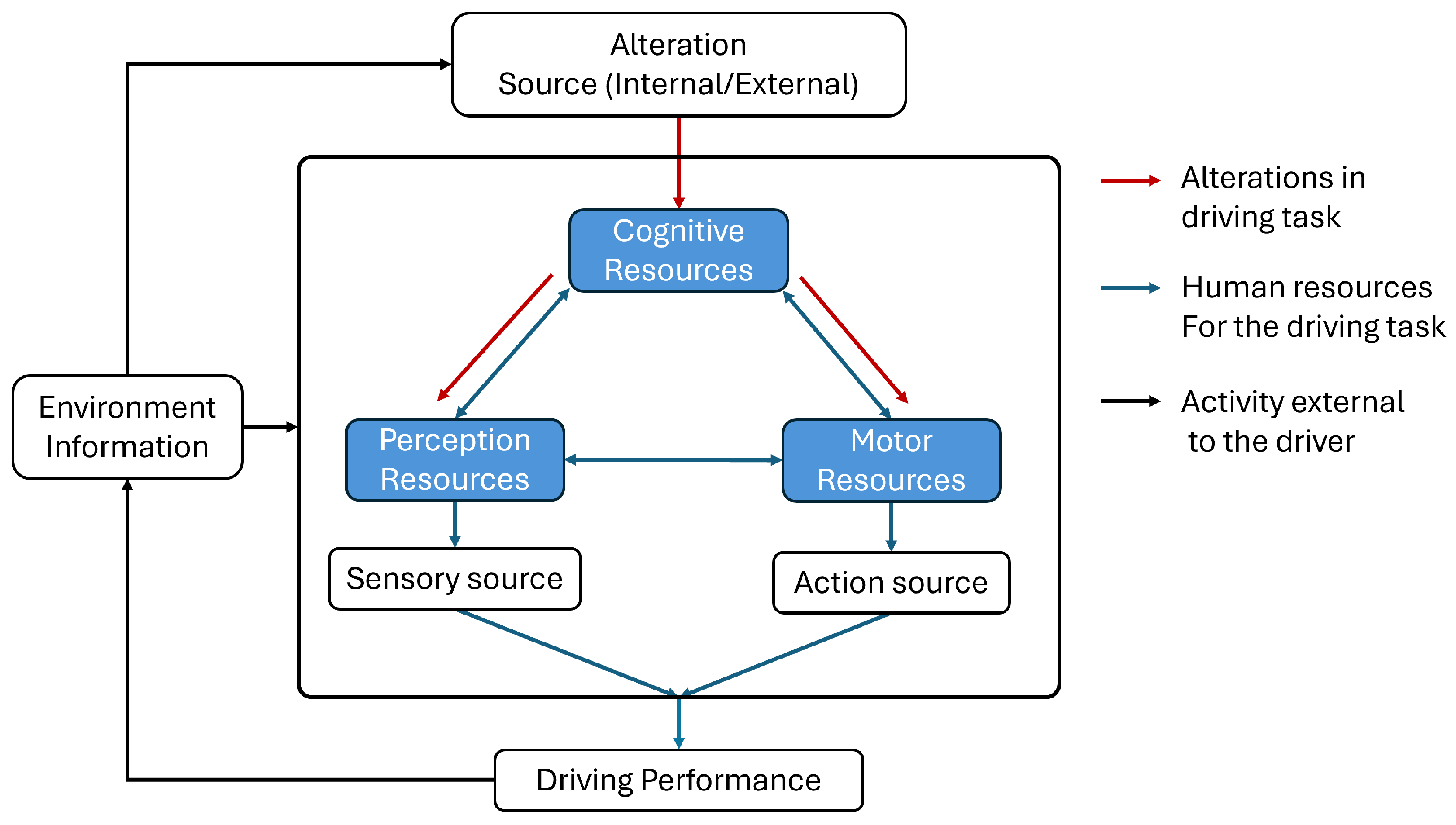

3.3.1. Monitoring Approach

- How does the driver feel emotionally?

- What is the driver’s physical condition?

- What actions is the driver performing?

3.3.2. Data Acquisition

3.3.3. Pre-Processing

- -

- Noise extraction (denoising).

- -

- Generation of time windows.

- -

- Application of algorithms for signal adaptation.

- -

- Artifact filtering.

- -

- Counting frames and establishing time windows.

- -

- Image conversion (e.g., from RGB to grayscale).

- -

- Use of AI for detecting significant elements, poses, or faces.

- -

- Adjustment for varying lighting conditions.

- -

- Application of filters to enhance image quality.

- -

- Generation of time windows.

- -

- Pupil detection.

- -

- Eye position localization.

- -

- Calibration of sensors based on the driver’s position.

- -

- Signal filtering.

- -

- Extraction of relevant signals, such as acceleration, lateral position, or brake usage.

3.3.4. Feature Extraction

3.3.5. Classification

3.3.6. Driver State or Behavior Inferred

- Emotional State: Emotions such as afraid, angry, disgusted, happy, sad, surprised, and neutral can be inferred through facial expression recognition, voice tone analysis, and physiological cues. Understanding emotional states is relevant not only for safety but also for user experience and comfort in human–machine interaction [41,42,44,45,46].

3.4. DMS Implementation Process

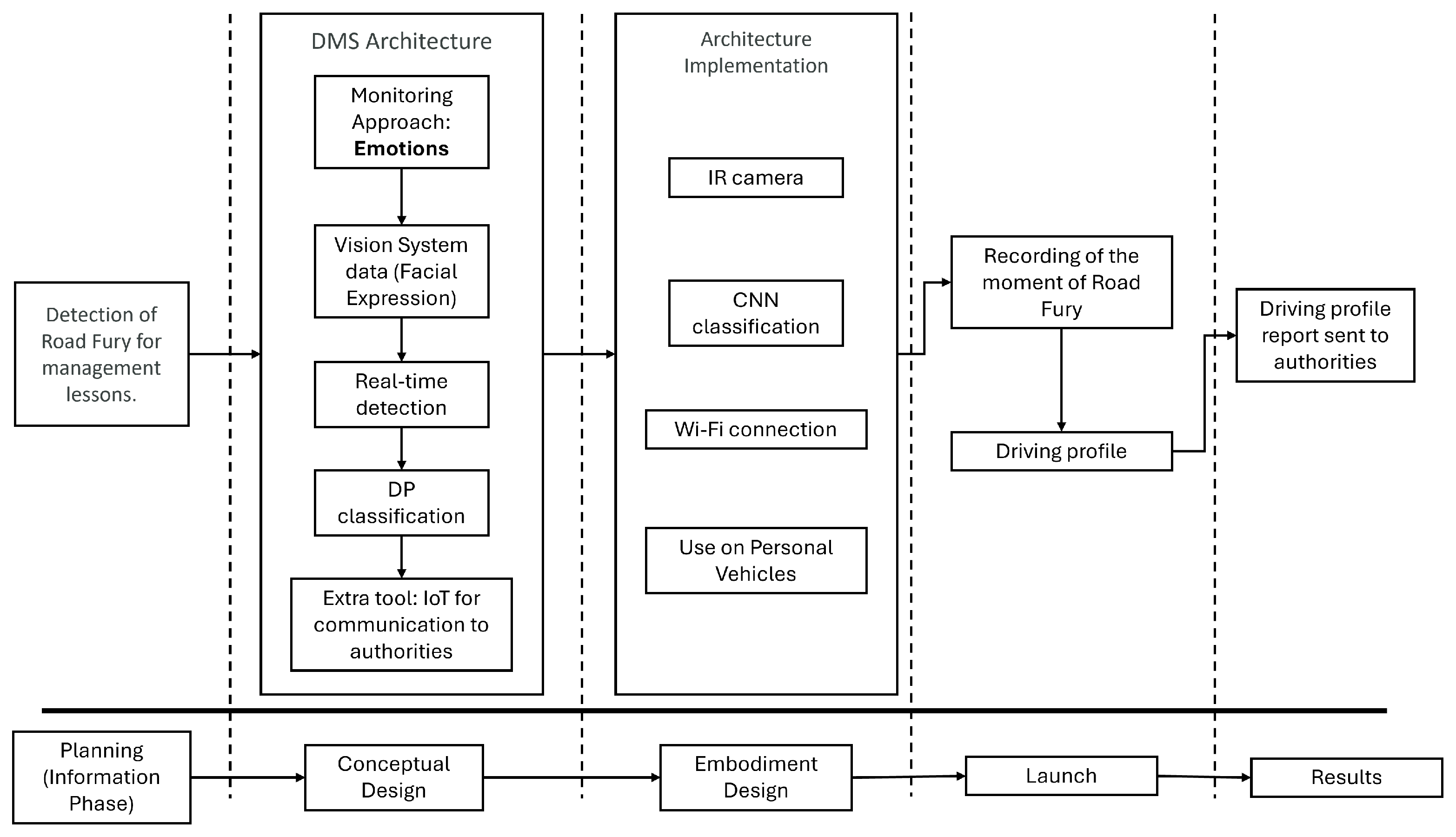

DMS Implementation Example

3.5. User Experience

- Distractions [64]: The integration of DMS poses challenges such as potential information overload and alert fatigue. Feedback delivered through HMIs or alert-based ADASs may inadvertently distract drivers, especially if it requires them to shift their gaze away from the road.

- Over-Reliance and fatigue [64,66,67]: There is a risk that drivers may become complacent and ignore warnings, potentially leading to riskier behavior due to an overdependence on assistance systems. Similarly, the constant use of alarms may fatigue the driver, leading to a state of agitation or prompting them to deactivate the system. In this same line, it is important to consider how the driver can regain control when interacting with advanced ADAS systems or vehicles featuring some level of autonomy.

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges of DMS

4.1.1. Unexpected Road Conditions

4.1.2. Vehicles Without Innovations

4.1.3. Limitations of the Sensors

4.1.4. Highly Complex Vehicle

4.2. Terminology

4.3. Opportunity Areas

4.3.1. UX and Intrusiveness

4.3.2. Real-World Test

4.3.3. Other Applications

4.4. Datasets

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control |

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AOI | Areas of Interest |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DMS | Driver Monitoring Systems |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| GSR | Galvanic Skin Response |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosted Decision Trees |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interface |

| IR | Infrared |

| INEGI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NCAP | New Car Assessment Programme |

| NHTSA | National Highway Traffic Safety Administration |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| UX | User Experience |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| WOS | Web Of Science |

Appendix A. Methodology Extra Details

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Articles from 2019 to 2024 | Articles not mainly focused on driver monitoring |

| Articles in English or Spanish | Reviews |

| Articles and Conference Proceedings | Discussion |

| Research Strategy | Scopus | WOS |

|---|---|---|

| “Driver Monitoring” AND “User Experience” | 12 | 9 |

| (“Driver Emotions” OR “Driver Behavior” OR “Driver State”) AND “Driver Monitoring” | 175 | 78 |

| (“Behavioral Research” OR “Driving Monitoring”) AND “User Experience” AND “Driving Simulator” | 16 | 1 |

| (“driver behavior” OR “driver emotions” OR “driver state”) AND “user experience” | 47 | 15 |

| (“driver behavior” OR “driver emotions” OR “driver state”) AND “user experience” | 65 | 48 |

Appendix B. Datasets

| No. | Name | Application in the Review | Type | Institution | Access | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3MDAD | Driver actions and Spatial Attention | Public | Laboratory of Advanced Technology and Intelligent Systems (LATIS) | Web Page | [79] |

| 2 | Driver drowsiness using keras | Drowsiness | Public | Noakhali Science And Technology University | Kaggle | [80] |

| 3 | RAD dataset | Aggressive driver behavior | Private | Vellore Institute of Technology | NA | [81] |

| 4 | GIDAS (PCM subset) | Drive behavior and state | Private | Federal Highway Research Institute (BASt) and the Research Association for Automotive Technology (FAT) | Web Page | [82] |

| 5 | Folksam data | Drive behavior and state | Private | Folksam Research, Euro NCAP and US-NCAP | NA | [83] |

| 6 | Naturalistic Driver Behavior Dataset (NDBD) | Driver posture and behavior | Public | ICMC/USP-Mobile Robots Lab and University of Sáo Paulo | Youtube | [84] |

| 7 | n.s. | Drowsiness | Private | VITAL Laboratory, Universiti Teknologi MARA | NA | [85] |

| 8 | Chengdu Taxi GPS Data | Driving Profile | Private | Data Castle | Web Page | [86] |

| 9 | n.s. | intention-aware lane | n.s. | Chalmers University of Technology and Zenseact | n.s. | [87] |

| 10 | n.s. | Primary and secondary driving task | Private | Silesian University of Technology | NA | [88] |

| 11 | n.s. | Drowsiness | Private | Mercedes-Benz Technology Center | NA | [89] |

| 12 | NTHU-DDD | Fatigue | Public | National Tsing Hua University, Computer Vision Lab | Kaggle | [90] |

| 13 | n.s. | Drowsiness and distraction | Private | HealthyRoad Biometric Systems | n.s. | [91] |

| 14 | n.s. | Driver anomalies behavior | Private | Department of Computer Science, Technical University of Ostrava | NA | [92] |

| 15 | State Farm Distracted Driver Detection | loss of attention | Public | State Farm | Kaggle | [93] |

| 16 | n.s. | Drowsiness | Private | Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo and Nissan Motor Co. | NA | [94] |

| 17 | n.s. | Drowsiness | Private | Mercedes-Benz AG | NA | [95] |

| 18 | n.s. | Drowsiness | Private | n.s. | n.s | [96] |

| 19 | n.s. | Head Position | Private | Széchenyi István University | NA | [97] |

| 20 | 300W-LP | Driver State | Public | Center for Biometrics and Security Research & National Laboratory of Pattern Recognition | Repository | [98] |

| 21 | AFLW2000 | Driver State | Public | Center for Biometrics and Security Research & National Laboratory of Pattern Recognition | Repository | [98] |

| 22 | ETH Face Pose Range Image Dataset | Driver State | Public for Research | BIWI, ETH Zurich | Web Page | [99] |

| 23 | MPIIGaze | Drive State | Public | Max Planck Institute for Informatics | Web Page | [100] |

| 24 | Multi-view Gaze Dataset | Drive State | Public | The University of Tokyo | Web Page | [101] |

| 25 | n.s. | Cognitive impairment | Public for Research | Florida Atlantic University | By request to the author | [102] |

| 26 | n.s. | Fatigue and Distraction | Private | Computer Science Department BITS Pilani | NA | [103] |

| 27 | ImageNet | Drowsiness | Public for Research | Princeton University and Stanford University | Web Page | [104] |

| 28 | n.s. | Driver Behavior | Private | ITMOUniversity | NA | [105,106] |

| 29 | n.s. | Driver Behavior | Private | Sharif University of Technology | NA | [107] |

| 30 | IR-Camera Datasets | Inattentios and Drowsiness | Public | Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute | Gitub | [108] |

| 31 | n.s. | Driver Behavior | Private | ITMO University | NA | [109] |

| 32 | YawDD dataset | Drowsiness | Public for Research | DISCOVER Lab, University of Ottawa | IEEE Dataport | [110] |

| 33 | n.s. | Emotions | Private | Fotonation Romania SRL | NA | [111] |

| 34 | DriverSVT | Driver State and actions | Public | ITMO University | Zenodo | [112] |

| 35 | Real & simulated driving | Driver distinction | Public for Research | Silesian University of Technology | IEEE Dataport | [113] |

| 36 | hcilab Driving Dataset | Driver physical condition | Public | hciLab Group, University of Stuttgart | Web Page | [114] |

| 37 | n.s. | Driver physical condition | Public for research | Direção Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e da Ciência (DGEEC) | By request to the author | [115] |

| 38 | Warwick-JLR Driver Monitoring Dataset (DMD) | Driver physical condition | Public for Research | University of Warwick | Request Form | [116] |

| 39 | Long-term ST database | Driver physical condition | Public | Laboratory of Biomedical Computer Systems and Imaging, University of Ljubljana | PhysioNet | [117] |

| 40 | Simulated Driving Database (SDB)/Alarm Test Driving Database/Real Driving Database (RDB) | Driver physical condition | Private | n.s. | NA | [118] |

| 41 | PTB-XL | Driver physical condition | Public | Physikalisch Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) | PhysioNet | [119] |

| 42 | Drive&Act dataset | Driver Behavior | Public for Research | Fraunhofer IOSB | Web Page | [120] |

| 43 | Open-Drive&Act | Driver Behavior | Public | Institute for Anthropomatics and Robotics, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology | Github | [121] |

| No. | Name | Application in the Review | Type | Institution | Access | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | Facial Expression Recognition 2013 (FER2013) | Emotions | Public | Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms (MILA) | Kaggle | [122] |

| 45 | Keimyung University Facial Expression of Drivers (KMU-FED) dataset | Emotions | Public | Keimyung University | Web Page | [123] |

| 46 | n.s. | Eye detection | Private | Continental Automotive Romania | Access through Continental | [124] |

| 47 | n.s. | Driver Actions | Private | South Carolina State University | Request to the author | [125] |

| 48 | n.s | Drowsiness | Private | University of Iowa Driving Safety Research Institute | NA | [126] |

| 49 | n.s | Driving Behavior | Private | Kyungpook National University | NA | [127] |

| 50 | n.s. | Drowsiness and Distraction | Private | Research Centre for Territory, Transports and Environment, University of Porto | NA | [128] |

| No. | Name | Data Purpose | Type | Institution | Access | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | MIT-BIH Noise Stress Test Database | Stress by noise | Public | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) | PhysioNet | [129] |

| 49 | MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database | Arrythmia | Public | MIT | PhysioNet | [130] |

| 50 | European ST-T Database | ST and T changes in the ECG | Public | Clinical Physiology del National Research Council (CNR) | PhysioNet | [131] |

| 51 | NTU RGB+D | Actions | Public | Nanyang Technological University | Web Page | [132] |

| 52 | Turms Dataset | Hand Detection | Public | University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Modena | Web Page | [133] |

| 53 | Distracted Driver Dataset | Driver Distraction | Public | Machine Intelligence group at the American University in Cairo (MI-AUC) | Web Page | [134] |

| 54 | EEE BUET Distracted Driving (EBDD) | Driver Distraction | Public | Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) | Web Page | [135] |

| 55 | UnoViS | Vital Signs | Public | mediT | Web Page | [136] |

| 56 | The original EEG data for driver fatigue detection | Driver Fatigue | Public | Beihang University | Repository | [137] |

| 57 | SEED Dataset | EEG and eye movement | Public for Research | Shanghai Jiao Tong University & Brain-Like Computing and Machine Intelligence (BCMI) | Web Page | [138] |

| 58 | EEG Alpha Waves dataset | EEG Alpha Waves | Public | GIPSA-lab | Zenodo | [139] |

| 59 | Multi-channel EEG recordings during a sustained-attention driving task | Attention on Driving Task | Public | University of Technology Sydney (UTS) | Repository | [140] |

| 60 | Driver Behavior Dataset | Driving Events | Public | Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR) | Github | [141] |

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Síntesis Metodológica de la Estadística de Accidentes de Tránsito Terrestre en Zonas Urbanas y Suburbanas 2016; INEGI: Mexico, 2016; ISBN 978–607-739-996-4. Available online: https://en.www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/nueva_estruc/702825087999.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Singh, S. Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey; Report No. DOT HS 812 506; NHTSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812506 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Davoli, L.; Martalò, M.; Cilfone, A.; Belli, L.; Ferrari, G.; Presta, R.; Montanari, R.; Mengoni, M.; Giraldi, L.; Amparore, E.G.; et al. On Driver Behavior Recognition for Increased Safety: A Roadmap. Safety 2020, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Lin, Y. Modelling of operators’ emotion and task performance in a virtual driving environment. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2011, 69, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGuzman, C.A.; Donmez, B. Training benefits driver behaviour while using automation with an attention monitoring system. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg.Technol. 2024, 165, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Summary Report: Standing General Order on Crash Reporting for Level 2 Advanced Driver Assistance Systems. DOT HS 813 325; Washington, DC, USA, June 2022. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/2022-06/ADAS-L2-SGO-Report-June-2022.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Perrier, M.J.R.; Louw, T.L.; Carsten, y.O.M.J. Usability testing of three visual HMIs for assisted driving: How design impacts driver distraction and mental models. Ergonomics 2023, 66, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, C.; Dinakar, S.; Sanagaram, M.; Ferris, T.K. Emergency Vehicle Operator On-Board Device Distractions; Technical Report; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.M.; D’Ambrosio, L.A. Impacts of Advanced Vehicle Technologies and Risk Attitudes on Distracted Driving Behaviors. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2678, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan-Montero, Y.; De-Moya-Anegón, F.; Guerrero-Bote, V.P. SCImago Graphica: A new tool for exploring and visually communicating data. Prof. Inf. 2022, 31, e310502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer, Version 1.6.20, Software Tool for Constructing and Visualizing Bibliometric Networks; Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS), Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Braun, M.; Chadowitz, R.; Alt, F. User Experience of Driver State Visualizations: A Look at Demographics and Personalities. In Human-Computer Interaction—INTERACT 2019 (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 11749), Proceedings of the INTERACT 2019, Paphos, Cyprus, 2–6 September 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, S.; Bosch, E.; Ihme, K.; Oehl, M. In-Vehicle Frustration Mitigation via Voice-User Interfaces—A Simulator Study. In HCI International 2021—Posters (Communications in Computer and Information Science, Volume 1421); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Du, J.; Sheng, W.; Osipychev, D.; Sun, Y.; Bai, H. A Human-Vehicle Collaborative Driving Framework for Driver Assistance. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 3470–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frémont, V.; Phan, M.-T.; Thouvenin, I. Adaptive Visual Assistance System for Enhancing the Driver Awareness of Pedestrians. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 36, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhall, M.; Wilson, K.; Yang, S.; Kuo, J.; Sletten, T.; Anderson, C.; Lenné, M.G.; Rajaratnam, S.; Magee, M.; Collins, A.; et al. European NCAP Driver State Monitoring Protocols: Prevalence of Distraction in Naturalistic Driving. Hum. Fact. 2024, 66, 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiles-Cucarella, E.; Cano-Bernet, J.; Santos-Fernández, L.; Roldán-Blay, C.; Roldán-Porta, C. Multi-Index Driver Drowsiness Detection Method Based on Driver’s Facial Recognition Using Haar Features and Histograms of Oriented Gradients. Sensors 2024, 24, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linschmann, O.; Uguz, D.U.; Romanski, B.; Baarlink, I.; Gunaratne, P.; Leonhardt, S.; Walter, M.; Lueken, M. A Portable Multi-Modal Cushion for Continuous Monitoring of a Driver’s Vital Signs. Sensors 2023, 23, 4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidei, A.; Rapa, P.M.; Tagliavini, G.; Rabbeni, R.; Pavan, P.; Benatti, S. ANGELS—Smart Steering Wheel for Driver Safety. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Workshop on Advances in Sensors and Interfaces (IWASI), Monopoli (Bari), Italy, 8–9 June 2023; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, A.; Kale, J.G.; Pachhapurkar, N.; Karle, M.; Karle, U. Development & Testing of a Camera-Based Driver Monitoring System; SAE Technical Paper 2024-26-0028; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontaxi, A.; Ziakopoulos, A.; Yannis, G. Trip characteristics impact on the frequency of harsh events recorded via smartphone sensors. IATSS Res. 2021, 45, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ortega, D.; Díaz-Pernas, F.J.; Martínez-Zarzuela, M.; Antón-Rodríguez, M. A Physiological Sensor-Based Android Application Synchronized with a Driving Simulator for Driver Monitoring. Sensors 2019, 19, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ortega, D.; Díaz-Pernas, F.J.; Martínez-Zarzuela, M.; Antón-Rodríguez, M. Comparative Analysis of Kinect-Based and Oculus-Based Gaze Region Estimation Methods in a Driving Simulator. Sensors 2020, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundinger, T.; Yalavarthi, P.K.; Riener, A.; Wintersberger, P.; Schartmüller, C. Feasibility of smart wearables for driver drowsiness detection and its potential among different age groups. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2020, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Q.; Delrobaei, M.; Giveki, A.; Dayarian, N.; Haghighi, S.J. Driver Drowsiness Detection with Commercial EEG Headsets. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICRoM), Tehran, Iran, 22–24 November 2022; pp. 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.J.; Bärgman, J.; Aust, M.L.; Matthews, G.; Svanberg, B. Let complexity bring clarity: A multidimensional assessment of cognitive load using physiological measures. Front. Neuroergonomics 2022, 3, 787295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Ren, F.; Tang, M.; Xiao, H.; Liu, Y.; Guo, G. Multi-modal user experience evaluation on in-vehicle HMI systems using eye-tracking, facial expression, and finger-tracking for the smart cockpit. Int. J. Veh. Perform. 2022, 8, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, M.; Catani, L.; Hazoor, A.; Hoxha, A.; Lioi, A.; Portera, A.; Tefa, L. Do driver monitoring technologies improve the driving behaviour of distracted drivers? A simulation study to assess the impact of an auditory driver distraction warning device on driving performance. Transp. Res. Part F Traff. Psychol. Behav. 2023, 95, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.; Kirmas, A.; Lemcke, S.; Böshagen, S.; Walter, M.; Eckstein, L.; Leonhardt, S. Head Tracking in Automotive Environments for Driver Monitoring Using a Low Resolution Thermal Camera. Vehicles 2022, 4, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Nishida, M. Real-Time Safety Driving Advisory System Utilizing a Vision-Based Driving Monitoring Sensor. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2024, E107.D, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniakowsky, I.M.; Forster, Y.; Naujoks, F.; Krems, J.F.; Keinath, A. How Do Automation Modes Influence the Frequency of Advanced Driver Distraction Warnings? A Simulator Study. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Ingolstadt, Germany, 18–22 September 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, J.; Lenné, M.G.; Mulhall, M.D.; Sletten, T.L.; Anderson, C.; Howard, M.E.; Rajaratnam, S.M.; Magee, M.; Collins, A. Continuous monitoring of visual distraction and drowsiness in shift-workers during naturalistic driving. Saf. Sci. 2019, 119, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, A.N.; Aquino, A.L.L.; Câmara de, M. Santos, R.C.; Guimarães, R.L.M.; Oliveira, R.A.R. Vehicle driver monitoring through the statistical process control. Sensors 2019, 19, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, K.; Tiwari, P.; Work, D.B. Gaussian Process-Based Personalized Adaptive Cruise Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 21178–21189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, X. Safety assessment of trucks based on GPS and in-vehicle monitoring data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 168, 106619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Osuga, S.; Fujikake, K.; Karatas, N.; Kanamori, H. Identifying High-Risk Older Drivers by Head-Movement Monitoring Using a Commercial Driver Monitoring Camera. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, R.; Joshi, V.; Shah, M. A comprehensive review of approaches to detect fatigue using machine learning techniques. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2021, 8, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Amidei, A.; Benatti, S.; Iadarola, G.; Tramarin, F.; Rovati, L.; Pavan, P.; Spinsante, S. Exploiting Blood Volume Pulse and Skin Conductance for Driver Drowsiness Detection. In IoT Technologies for HealthCare: 9th EAI International Conference, HealthyIoT 2022, Braga, Portugal, 16–18 November 2022, Proceedings, LNICST; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 456, pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziryawulawo, A.; Kirabo, M.; Mwikirize, C.; Serugunda, J.; Mugume, E.; Miyingo, S.P. Machine learning based driver monitoring system: A case study for the Kayoola EVS. SAIEE Afr. Res. J. 2023, 114, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccacci, S.; Mengoni, M.; Generosi, A.; Giraldi, L.; Presta, R.; Carbonara, G.; Castellano, A.; Montanari, R. Designing in-car emotion-aware automation. Eur. Transp. 2021, 84, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-J.; Cho, G.; Song, W.; Kim, M.-J.; Ahn, C.W.; Song, M. Personalized EV Driving Sound Design Based on the Driver’s Total Emotion Recognition. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobility 2023, 5, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero, E. Towards real-time monitoring of fear in driving sessions. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccacci, S.; Mengoni, M.; Generosi, A.; Giraldi, L.; Carbonara, G.; Castellano, A.; Montanari, R. A preliminary investigation towards the application of facial expression analysis to enable an emotion-aware car interface. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction—Applications and Practice: 14th International Conference, UAHCI 2020, Part II (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 12213); Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generosi, A.; Bruschi, V.; Cecchi, S.; Dourou, N.A.; Montanari, R.; Mengoni, M. An Innovative System for Driver Monitoring and Vehicle Sound Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Automotive (MetroAutomotive), Bologna, Italy, 26–28 June 2024; pp. 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.; Koç, İ.A.; Suga, C.; Lee, A.; Dhareshwar, A.M.; Franzén, E.; Iozzo, M.; Morrison, G.; McKeown, G. Assessing the Use of Physiological Signals and Facial Behaviour to Gauge Drivers’ Emotions as a UX Metric in Automotive User Studies. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications (AutomotiveUI ’20 Adjunct), Virtual Event, 21–22 September 2020; pp. 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Y.; Schoemig, N.; Kremer, C.; Wiedemann, K.; Gary, S.; Naujoks, F.; Keinath, A.; Neukum, A. Attentional warnings caused by driver monitoring systems: How often do they appear and how well are they understood? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 205, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashevnik, A.; Lashkov, I.; Gurtov, A. Methodology and Mobile Application for Driver Behavior Analysis and Accident Prevention. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccour, M.H.; Driewer, F.; Schäck, T.; Kasneci, E. Comparative Analysis of Vehicle-Based and Driver-Based Features for Driver Drowsiness Monitoring by Support Vector Machines. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 23164–23178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, S.; Nahvi, A.; Tashakori, M.; Triki, H.K. Evaluation of driver drowsiness using respiration analysis by thermal imaging on a driving simulator. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 17793–17815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Gaspar, J.; Miller, T.; Yousefian, R. The detection of drowsiness using a driver monitoring system. Traff. Inj. Prev. 2019, 20 (Suppl. S1), S157–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Gaspar, J.; Yousefian, R. Multi-sensor driver monitoring for drowsiness prediction. Traff. Inj. Prev. 2023, 24 (Suppl. S1), S100–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogister, F.; Mwange, M.-A.P.; Rukonić, L.; Delbeke, O.; Virlouvet, R. Fast Detection and Classification of Drivers’ Responses to Stressful Events and Cognitive Workload. In HCI International 2022 Posters: 24th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCII 2022, Virtual Event, 26 June–1 July 2022, Proceedings, Part II, Communications in Computer and Information Science; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1581, pp. 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.J.; Victor, T.; Aust, M.L.; Svanberg, B.; Lindén, P.; Gustavsson, P. On-to-off-path gaze shift cancellations lead to gaze concentration in cognitively loaded car drivers: A simulator study exploring gaze patterns in relation to a cognitive task and the traffic environment. Transp. Res. Part F Traff. Psychol. Behav. 2020, 75, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benusa, M.; Min, C.-H. Wearable Driver Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 67th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Springfield, MA, USA, 11–14 August 2024; pp. 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyahi, P. A Brain Wave-Verified Driver Alert System for Vehicle Collision Avoidance. SAE Int. J. Trans. Saf. 2021, 9, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Gaspar, J.; Carney, C.; Gunaratne, P. Silent failure detection in partial automation as a function of visual attentiveness. Traff. Inj. Prev. 2023, 24 (Suppl. S1), S88–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camden, M.C.; Soccolich, S.A.; Hickman, J.S.; Hanowski, R.J. Reducing risky driving: Assessing the impacts of an automatically assigned, targeted web-based instruction program. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 70, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, K.; Eppinger, S. Product Design and Development; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dieter, G.E.; Schmidt, L.C. Engineering Design, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Calderón, L.A.; Izquierdo-Reyes, J.; Tejera, J.A.d.l. Proposal of a Methodology for Mechatronic Design From Ideation to Embodiment Design: Application in a Masonry Robot Case Study Design. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 140667–140684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presta, R.; Simone, F.D.; Tancredi, C.; Chiesa, S. Nudging the safe zone: Design and assessment of HMI strategies based on intelligent driver state monitoring systems. In HCI in Mobility, Transport, and Automotive Systems: 5th International Conference, MobiTAS 2023, Held as Part of the 25th HCI International Conference, HCII 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023, Proceedings, Part I; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14048, pp. 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidabadi, N.S.; Song, Y.; Wang, K.; Jackson, E. Evaluation of Driver Reaction to Disengagement of Advanced Driver Assistance System with Different Warning Systems While Driving Under Various Distractions. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2678, 1614–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance-Tremblay, J.; Tkiouat, Z.; Léger, P.-M.; Cameron, A.-F.; Titah, R.; Coursaris, C.K.; Sénécal, S. A gaze-based driver distraction countermeasure: Comparing effects of multimodal alerts on driver’s behavior and visual attention. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2024, 193, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinmueller, K.; Kiesel, A.; Steinhauser, M. Adverse Behavioral Adaptation to Adaptive Forward Collision Warning Systems: An Investigation of Primary and Secondary Task Performance. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 146, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, S.; Haramaki, T.; Nishino, H. A safe driving support method using olfactory stimuli. In Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems. CISIS 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Itoh, M.; Inagaki, T. Bringing a Vehicle to a Controlled Stop: Effectiveness of a Dual-Control Scheme for Identifying Driver Drowsiness and Executing Safety Control under Hands-off Partial Driving Automation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 8339–8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, T.; Sakamoto, J. Effect of time length of eye movement data analysis on the accuracy of mental workload estimation during automobile driving. In Proceedings of the 21st Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2021), Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 221, pp. 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.V.; Rehmann, M.; de la Rosa, S.; Curio, C. Investigating Drivers’ Awareness of Pedestrians Using Virtual Reality towards Modeling the Impact of External Factors. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 2–5 June 2024; pp. 3001–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, M.M.; Soares, D.; Baptista, J.S. Assessing post-driving discomfort and its influence on gait patterns. Sensors 2021, 21, 8492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkov, I.; Kashevnik, A.; Shilov, N. Dangerous State Detection in Vehicle Cabin Based on Audiovisual Analysis with Smartphone Sensors. In Intelligent Systems and Applications—Proceedings of SAI Intelligent Systems Conference (IntelliSys 2020), Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Arai, K., Kapoor, S., Bhatia, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1250, pp. 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Maggi, D.; Hirose, T.; Broadhead, Z.; Carsten, O. Impact of Lane Keeping Assist System Camera Misalignment on Driver Behavior. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 25, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstačić, R.; Žužić, A.; Orehovački, T. Safety Aspects of In-Vehicle Infotainment Systems: A Systematic Literature Review from 2012 to 2023. Electronics 2024, 13, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, J.; Monk, C.A.; Hanowski, R.J.; Horrey, W.J.; Lee, J.D.; McGehee, D.V.; Regan, M.; Stevens, A.; Traube, E.; Tuukkanen, M.; et al. A Conceptual Framework and Taxonomy for Understanding and Categorizing Driver Inattention. Project Report; Driver Distraction & Human-Machine Interaction Working Group, US-EU Bilateral Intelligent Transportation Systems Technical Task Force; 2013; Available online: https://iro.uiowa.edu/esploro/outputs/report/A-conceptual-framework-and-taxonomy-for/9984186943902771 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Regan, M.A.; Hallett, C.; Gordon, C.P. Driver distraction and driver inattention: Definition, relationship and taxonomy. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE International. Operational Definitions of Driving Performance Measures and Statistics, SAE Standard J2944_202302 (Recommended Practice). Available online: https://saemobilus.sae.org/standards/j2944_202302-operational-definitions-driving-performance-measures-statistics (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- European New Car Assessment Programme (Euro NCAP). Assessment Protocol—Safety Assist: Safe Driving, Version 10.1; Implementation 2023. July 2022. Available online: https://cdn.euroncap.com/media/70315/euro-ncap-assessment-protocol-sa-safe-driving-v101.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Marafie, Z.; Lin, K.-J.; Wang, D.; Lyu, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Ma, J. AutoCoach: An Intelligent Driver Behavior Feedback Agent with Personality-Based Driver Models. Electronics 2021, 10, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegham, I.; Khalifa, A.B.; Alouani, I.; Mahjoub, M.A. 3MDAD: A novel public dataset for multimodal multiview and multispectral driver distraction analysis. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2020, 88, 115966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver Drowsiness Using Keras | Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/adinishad/driver-drowsiness-using-keras/comments (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Arumugam, S.; Bhargavi, R. Road Rage and Aggressive Driving Behaviour Detection in Usage-Based Insurance Using Machine Learning. Int. J. Softw. Innov. 2023, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIDAS–German In-Depth Accident Study; Verkehrsunfallforschung an der TU Dresden GmbH (VUFO): Hannover, Germany; Available online: https://www.gidas.org/start-en.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ydenius, A.; Stigson, H.; Kullgren, A.; Sunnevång, C. Accuracy of Folksam Electronic Crash Recorder (ECR) in Frontal and Side Impact Crashes. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Technical Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–30 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berri, R.; Osório, F. A 3D vision system for detecting use of mobile phones while driving. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Rozaimi, I.D.; Zaman, F.H.K.; Abdullah, S.A.C.; Abidin, H.Z.; Mazalan, L. Driver Drowsiness Detection Using Deep Learning Models Based On Different Camera Positions. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), Melaka, Malaysia; 2023; pp. 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Castle. Chengdu Taxi GPS Data. Pkbigdata. Available online: https://www.pkbigdata.com/common/zhzgbCmptDataDetails.html#down (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Dahl, J.; Campos, G.R.D.; Fredriksson, J. Intention-Aware lane keeping assist using driver gaze information. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–7 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doniec, R.; Konior, J.; Sieciński, S.; Piet, A.; Irshad, M.T.; Piaseczna, N.; Hasan, M.A.; Li, F.; Nisar, M.A.; Grzegorzek, M. Sensor-Based classification of primary and secondary car driver activities using convolutional neural networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreißig, M.; Baccour, M.H.; Schäck, T.; Kasneci, E. Driver Drowsiness Classification Based on Eye Blink and Head Movement Features Using the k-NN Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Canberra, Australia, 1–4 December 2020; pp. 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computer Vision Lab, National Tsuing Hua University. Driver Drowsiness Detection Dataset. 2016. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ismailnasri20/driver-drowsiness-dataset-ddd (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ferreira, S.; Kokkinogenis, Z.; Couto, A. Using real-life alert-based data to analyse drowsiness and distraction of commercial drivers. Transp. Res. Part F Traff. Psychol. Behav. 2018, 60, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusek, R.; Sojka, E.; Gaura, J.; Halman, J. Driver State Detection from In-Car Camera Images. In Advances in Visual Computing. ISVC 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Farm. State Farm Distracted Driver Detection. Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/state-farm-distracted-driver-detection/overview (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Gwak, J.; Hirao, A.; Shino, M. An investigation of early detection of driver drowsiness using ensemble machine learning based on hybrid sensing. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedi Baccour, M.; Driewer, F.; Schäck, T.; Kasneci, E. Camera-based Driver Drowsiness State Classification Using Logistic Regression Models. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–14 October 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbers, E.; Miller, M.; Neurauter, L.; Walters, J.; Glaser, D. Exploratory development of algorithms for determining driver attention status. Hum. Fact. J. Hum. Fact. Ergon. Soc. 2023, 66, 2191–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollósi, J.; Ballagi, Á.; Kovács, G.; Fischer, S.; Nagy, V. Bus Driver Head Position Detection Using Capsule Networks under Dynamic Driving Conditions. Computers 2024, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lei, Z.; Liu, X.; Shi, H.; Li, S.Z. Face Alignment Across Large Poses: A 3D Solution. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- ETH Zurich Computer Vision Lab. Head Pose Image Database. Available online: https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/vision2/datasets/headposeCVPR08 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Sugano, Y.; Fritz, M.; Bulling, A. MPIIGaze: Real-World Dataset for Appearance-Based Gaze Estimation. Max Planck Institute for Informatics. Available online: https://www.mpi-inf.mpg.de/departments/computer-vision-and-machine-learning/research/gaze-based-human-computer-interaction/appearance-based-gaze-estimation-in-the-wild (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Sugano, Y.; Matsushita, Y.; Sato, Y. Multi-View Gaze Dataset. UT Vision. 2014. Available online: https://www.ut-vision.org/resources/#datasets (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Jan, M.T.; Furht, B.; Moshfeghi, S.; Jang, J.; Ghoreishi, S.G.A.; Boateng, C.; Yang, K.; Conniff, J.; Rosselli, M.; Newman, D.; et al. Enhancing road safety: In-vehicle sensor analysis of cognitive impairment in older drivers. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 84, 18711–18732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janveja, I.; Nambi, A.; Bannur, S.; Gupta, S.; Padmanabhan, V. InSight. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.-J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kashevnik, A.; Teslya, N.; Ponomarev, A.; Lashkov, I.; Mayatin, A.; Parfenov, V. Driver monitoring cloud organisation based on smartphone camera and sensor data. In 17th International Conference on Information Technology–New Generations (ITNG 2020). Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashevnik, A.; Ponomarev, A.; Shilov, N.; Chechulin, A. Threats Detection during Human-Computer Interaction in Driver Monitoring Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, E.; Hemmatyar, A.M.A.; Siavoshani, M.J.; Moshiri, B. Safe Deep Driving Behavior Detection (S3D). IEEE Access 2022, 10, 113827–113838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; IR-Camera Datasets. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/kdh6126/IR-Carmera-Datasets (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Lindow, F.; Kaiser, C.; Kashevnik, A.; Stocker, A. AI-Based Driving Data Analysis for Behavior Recognition in Vehicle Cabin. In Proceedings of the 2020 27th Conference of Open Innovations Association (FRUCT), Trento, Italy, 7–9 September 2020; pp. 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, S.; Omidyeganeh, M.; Shirmohammadi, S.; Hariri, B. YawDD: Yawning Detection Dataset. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/yawdd-yawning-detection-dataset (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mălăescu, A.; Duţu, L.C.; Sultana, A.; Filip, D.; Ciuc, M. Improving in-car emotion classification by NIR database augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019), Lille, France, 14–18 May 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, W.; Kashevnik, A.; Hamoud, B.; Shilov, N. DriverSVT: Smartphone-Measured Vehicle Telemetry Data for Driver State Identification. Data 2022, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, M.; Morales-Alvarez, W.; Olaverri-Monreal, C. Automated Vehicle Driver Monitoring Dataset from Real-World Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneegass, S.; Pfleging, B.; Broy, N.; Schmidt, A.; Heinrich, F. A data set of real world driving to assess driver workload. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications (AutomotiveUI ’13), Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 28–30 October 2013; pp. 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Beatriz-Afonso, A.; Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T.; Castelli, M. Mathematics and Mother Tongue Academic Achievement: A Machine Learning approach. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Griffiths, N.; Bhalerao, A.; Xu, Z.; Gelencser, A.; Popham, T. Investigating the feasibility of vehicle telemetry data as a means of predicting driver workload. Int. J. Mob. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2017, 9, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, F.; Taddei, A.; Moody, G.B.; Emdin, M.; Antolič, G.; Dorn, R.; Smrdel, A.; Marchesi, C.; Mark, R.G. Long-term ST database: A reference for the development and evaluation of automated ischaemia detectors and for the study of the dynamics of myocardial ischaemia. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2003, 41, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Laguna, P.; Bartra, A.; Bailón, R. Drowsiness detection using heart rate variability. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016, 54, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.; Strodthoff, N.; Bousseljot, R.-D.; Kreiseler, D.; Lunze, F.I.; Samek, W.; Schaeffter, T. PTB-XL: A Large Publicly Available Electrocardiography Dataset (Version 1.0.3); PhysioNet: 2020. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/ptb-xl/1.0.3/ (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Roitberg, A.; Haurilet, M.; Voit, M.; Stiefelhagen, R. Drive&Act: A multi-modal dataset for fine-grained driver behavior recognition in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roitberg, A.; Ma, C.; Haurilet, M.; Stiefelhagen, R. Open Set Driver Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ian Goodfellow, J.; Cukierski, W.; Bengio, Y. FER-2013: Facial Expression Recognition 2013 Dataset. Challenges in Representation Learning: A Report on Three Machine Learning Contests, Neural Networks. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/challenges-in-representation-learning-facial-expression-recognition-challenge/overview (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Jeong, M.; Ko, B.C. KMU-FED: Keimyung University Facial Expression of Drivers Dataset; Keimyung University CVPR Laboratory. Available online: https://cvpr.kmu.ac.kr/KMU-FED.htm (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Valcan, S.; Gaianu, M. Ground Truth Data Generator for eye location on infrared driver recordings. J. Imaging 2021, 7, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengula, T.J.; Mwakalonge, J.L.; Comert, G.; Siuhi, S. Improving Road Safety with Ensemble Learning: Detecting Driver Anomalies Using Vehicle In-built Cameras. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2023, 14, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.; Gaspar, J.; Yousefian, R. Sequence analysis of monitored drowsy driving. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.; Lee, C.; Han, D.S. Neural Architecture Search for Real-Time Driver Behavior Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 21–24 February 2022; pp. 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Kokkinogenis, Z.; Ferreira, S.; Couto, A. Profiles of professional drivers based on drowsiness and distraction alerts. In Human Interaction, Emerging Technologies and Future Applications II. IHIET 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.B.; Muldrow, W.E.; Mark, R.G. MIT-BIH Noise Stress Test Database (NSTDB). PhysioNet. 1992. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/nstdb/1.0.0/ (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.B.; Mark, R.G. MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database, version 1.0.0; PhysioNet, Dataset. Published 24 February 2005. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/mitdb/1.0.0/ (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Taddei, A.; Distante, G.; Emdin, M.; Pisani, P.; Moody, G.B.; Zeelenberg, C.; Marchesi, C. The European ST-T Database: Standard for evaluating systems for the analysis of ST-T changes in ambulatory electrocardiography. Eur. Heart J. 1992, 13, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahroudy, A.; Liu, J.; Ng, T.-T.; Wang, G. NTU RGB+D: A Large Scale Dataset for 3D Human Activity Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1010–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Borghi, G.; Frigieri, E.; Vezzani, R.; Cucchiara, R. Hands on the wheel: A Dataset for Driver Hand Detection and Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018), Xi’an, China, 15–19 May 2018; pp. 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraqi, H.M.; Abouelnaga, Y.; Saad, M.H.; Moustafa, M.N. Driver Distraction Identification with an Ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Adv. Transp. 2019, 2019, 4125865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, T.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Ahmad, M.O.; Swamy, M.N.S. Recognizing Distractions for Assistive Driving by Tracking Body Parts. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartzek, T.; Czaplik, M.; Antink, C.H.; Eilebrecht, B.; Walocha, R.; Leonhardt, S. UnoViS: The MedIT public unobtrusive vital signs database. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2015, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.; Wang, P.; Hu, J. The Original EEG Data for Driver Fatigue Detection. Dataset, Figshare. Published 2017. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/The_original_EEG_data_for_driver_fatigue_detection/5202739 (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tao, L.-Y.; Ma, R.-X.; Zheng, W.-L.; Lu, B.-L. Investigating the effects of sleep conditions on emotion responses with EEG signals and eye movements. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattan, G.; Rodrigues, P.L.C.; Congedo, M. EEG Alpha Waves Dataset; GIPSA-lab: Grenoble, France, 17 Deceber 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Chuang, C.-H.; King, J.-K.; Lin, C.-T. Multi-Channel EEG Recordings During a Sustained-Attention Driving Task. Dataset, Figshare. 2019. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Multi-channel_EEG_recordings_during_a_sustained-attention_driving_task/6427334/5 (accessed on 6 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Júnior, J.; Carvalho, E.; Ferreira, B.V.; de Souza, C.; Suhara, Y.; Pentland, A.; Pessin, G. Driver behavior profiling: An investigation with different smartphone sensors and machine learning. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salazar-Calderón, L.A.; Navarro-Tuch, S.A.; Izquierdo-Reyes, J. Framework, Implementation, and User Experience Aspects of Driver Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111638

Salazar-Calderón LA, Navarro-Tuch SA, Izquierdo-Reyes J. Framework, Implementation, and User Experience Aspects of Driver Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111638

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalazar-Calderón, Luis A., Sergio Alberto Navarro-Tuch, and Javier Izquierdo-Reyes. 2025. "Framework, Implementation, and User Experience Aspects of Driver Monitoring: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111638

APA StyleSalazar-Calderón, L. A., Navarro-Tuch, S. A., & Izquierdo-Reyes, J. (2025). Framework, Implementation, and User Experience Aspects of Driver Monitoring: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11638. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111638