Abstract

Sign Languages are the primary communication modality of deaf communities, yet building effective Isolated Sign Language Recognition (ISLR) systems remains difficult under data limitations. In this work, we curated a sub-dataset from the DGS-Korpus focused on recognizing affirmations and negations (polar answers) in German Sign Language (DGS). We designed lightweight transformer models using landmark-based inputs and evaluated them on two tasks: the binary classification of affirmations versus negations (binary semantic recognition) and the multi-class recognition of sign variations expressing positive or negative replies (multi-class gloss recognition). The main contribution of the article, hence, relies on the exploration of models for performing polar answer recognition in DGS and the exploration of differences between performing multi-class or binary class classification. Our best binary model achieved an accuracy of 97.71% using only hand landmarks without Positional Encoding, highlighting the potential of lightweight landmark-based transformers for efficient ISLR in constrained domains.

1. Introduction

Sign Languages (SLs) are natural, fully developed languages that play a central role in the lives of millions of people worldwide. They are complete linguistic systems with their own grammar, syntax, and cultural identity. For deaf communities, Sign Language is more than a communication tool; it is a cornerstone of social interaction, education, and cultural expression. Globally, the World Health Organization estimated that there exist 1.5 billion of the global population suffering from a hearing impairment to different degrees and this number is expected to increase to approximately 2.5 billion by 2050 [1]. However, and despite the growing awareness, barriers persist in different ambits, such as educational or governmental, due to the lack of bilingual education and the limited number of interpreting services [2]. In this scenario, the advancement of technologies and applications capable of enabling bi-directional translations between spoken and SLs represents a crucial solution for overcoming these existing communication barriers.

Traditionally, research on the automatic translation of Sign Language videos into text has primarily focused on two main approaches: Continuous Sign Language Translation (CSLT) and Isolated Sign Language Recognition (ISLR). Firstly, CSLT seeks to directly translate continuous signing in a given Sign Language (e.g., German Sign Language (DGS)) into a spoken language, bypassing the intermediate representation and directly addressing the end-to-end continuous translation problem. Although this approach allows for more natural translation and reduces annotation efforts, it demands substantially larger datasets to train robust models. However, and despite the considerable linguistic diversity of Sign Languages worldwide, the availability of large-scale datasets for CSLT remains limited, particularly for specific Sign Languages, both in terms of size and vocabulary, as mentioned in a previous study [3], which is not reliable for critical applications and scenarios in which precise translation is paramount over general conversational translation, such as in emergency scenarios.

As an alternative, there exists another branch focused on more controlled scenarios and recognition, Isolated Sign Language Recognition (ISLR). ISLR aims to identify, from video input, the specific gloss represented by a signer. A gloss, in this context, refers to the written form of a spoken language word (e.g., German) used as a label to describe or transcribe a sign in a specific Sign Language (e.g., DGS). Although glosses are not required from a Sign Language perspective, they aid assimilation to document and study Sign Languages from linguistic and computational perspectives. This fact has lead to different standards and schemes for annotating glosses in SL videos. In contrast to CSLT, one of the main advantages of ISLR is it usually has a higher confidence in predictions, as well as its relatively modest data requirements, since these systems rely on a limited vocabulary. As a result of its flexible vocabulary, the architectures employed for training classifiers can be designed with fewer parameters and reduced complexity, thereby enabling the development of embedded applications. These specific characteristics create opportunities to investigate lightweight architectures and domain-specific datasets, particularly for ISLR, where promising results can still be obtained despite data limitations.

In this line, this article focuses on the task of performing Isolated Sign Language Recognition in German Sign Language. Specifically, we investigate how to implement detectors of answers to linguistically polar questions, i.e., those clauses that expect a yes–no answer. Being able to correctly classify these polar answers is considered a basic but also critical recognition task that can cover answers to a large number of plausible questions, allowing the development of more natural and human-centered applications for the deaf community to enable, for example, interactions with avatars. With the final goal of researching Sign Language recognizers, we explored two approaches for performing affirmation/negation recognition: (1) based on its semantic meaning, (2) based on the distinction of the so-called linguistically annotated glosses and their final assimilation as a yes or no answer. The contributions of the article are then threefold:

- We selected and filtered a subset of the DGS-Korpus to train systems to perform polar answers recognition. With this subset, we trained a set of lightweight transformers fed with landmarks to perform the Isolated Sign Language Recognition task of recognizing affirmations and negations. For optimizing this model, we evaluated different combinations of hyperparameters to create a competitive baseline in affirmation–negation detection.

- We evaluated the contribution of employing different channels (i.e., the hands and body), given that for some signs the relevant information is mainly carried by manual cues, but for discerning others, non-manual cues (e.g., pose, mouthing) are required. This way, it is possible to understand the main set of body landmarks that could achieve the maximum performance while resulting in lighter models. In this study of input features, we also compared whether including the depth (z-component) for each landmark could provide benefits to the final models.

- As certain signs can have different gloss names but the same meaning, we explore the differences between predicting signs at the semantic level (in a binary classification task) or at the gloss level (in a multi-class classification problem) to study their differences and whether one system could bring advantages versus the other.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work, covering existing SL datasets and the proposals of models for ISLR. Section 3 outlines the methodology, beginning with dataset descriptions and pre-processing steps. It then details the process of landmark extraction and the transformer models evaluated using different strategies. Section 4 presents the experimental setup along with the key findings, and an error analysis of the top discovered models for binary and multi-class approaches. Finally, Section 5 concludes the article by highlighting the main takeaways and proposing directions for future research.

2. Related Works

In this section, we first present the datasets available to the research community for Sign Language recognition or translation, specially focusing on DGS. We then provide an overview of the evolution of the employed models in the literature from CNNs to transformers, with a particular emphasis on the task of ISLR.

2.1. Datasets for Sign Language Recognition/Translation

The development of robust systems for Sign Language recognition (SLR) and Sign Language translation (SLT) critically depends on the availability of high-quality datasets. Over the past decades, several corpora have been created to document and support computational research across a variety of Sign Languages, such as American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL), and German Sign Language (DGS), among others. For example, in Chinese Sign Language (CSL), the CSL-Daily dataset [4] is a reference dataset for performing continuous Chinese Sign Language translation and recognition, focusing on natural daily life scenarios such as travel, shopping, and medical care. The dataset contains 20,654 videos with a total duration of approximately 23.27 h recorded in a lab-controlled environment. In American Sign Language (ASL), WLASL [5] and MS-ASL [6] have been frequently employed as benchmarks for ISLR. The first, WLASL, contains over 21,000 video samples covering 2000 different common ASL glosses performed by more than 100 signers. One of the disadvantages of this dataset is that it was collected from the web, which results in different signs assigned to the same label, making the predictions challenging for the models. The second, MS-ASL, contains approximately 25,000 annotated video samples of 1000 distinct ASL signs performed by more than 200 different signers. How2Sign [7] is a more recent example of a released dataset for research in ASL. It consists of over 80 h of multimodal and multiview videos recorded by native signers and professional interpreters, aiming to support research on Sign Language recognition, translation, and production with a focus on instructional resources.

In the line of generating more resources in SL, efforts have also been invested to study differences between Sign Languages, resulting in several collections of datasets such as the ECHO corpus [8]. Among its recordings, this corpus contains videos of lexical elicitation and annotated segments of dialogue, poetry, and fairy tale narrations. This dataset was created to pursue ‘comparative studies of European Sign Languages’. For this reason, and despite the challenges of collecting data from minorities, including different dialects and languages, they acquired recordings in German Sign Language (DGS), British Sign Language (BSL), Dutch Sign Language (NGT), and Swedish Sign Language (SSL).

Nonetheless and despite the large amount of resources in different languages, when focusing on research in specific scenarios, tasks (e.g., ISLR versus CSLT), and applications, the amount of available resources is narrowed. Specifically and focusing on the Sign Language addressed in this article, DGS, there exist counted datasets available that have been employed mainly with research purposes. Two of the most employed benchmark datasets for statistical DGS Sign Language recognition and translation are RWTH-PHOENIX and RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather2014T [9,10]. They consist of video recordings of Sign Language interpreters presenting the daily weather forecast from the German public TV station PHOENIX. Although these datasets contain valuable information, their vocabulary is limited to the weather domain. Additionally, its annotations cannot be directly employed for ISLR without a prior alignment step, since they lack temporal annotations of the start and ending time of each gloss.

SIGNUM [11] is another dataset containing signs and annotations for studying DGS recognition and translation. It contains both isolated signs and continuous sentences performed by native DGS signers. The vocabulary includes 450 basic signs, from which 780 sentences were constructed with different lengths ranging from 2 to 11 signs. The entire corpus was performed by 25 native signers (23 right-handed and 2 left-handed signers) varying in ages, genders, and signing styles. The data were recorded under controlled laboratory conditions as sequences of images (frames), with a total of more than 33,000 sequences and nearly 6 million images, which amounts to about 55 h of video data at a resolution of 776 × 578 pixels and 30 frames per second. More recently, the AVASAG dataset [12,13] was developed with the aim of covering daily life traveling situations. It was annotated with German texts and glosses for research purposes in ISLR and CSLT. Unlike previous datasets, this dataset contains motion tracking data for enhancing research in Sign Language production with avatars. Overall, AVASAG contains a collection of 312 videos of sentences recorded at a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second, with a total duration of 96.05 min.

Despite the variability of datasets, they are normally limited in the covered vocabulary, context, and domains, which reduces the possibilities of developing recognizers focusing on certain scenarios. Moreover, the glosses’ annotation scheme also changes from one dataset to another. For this reason, the DGS-Korpus project [14] aimed to create a comprehensive corpus with samples of dialogue on everyday situations collected from native DGS signers across Germany. In order to handle different variations and study them from a linguistic perspective, guidelines and standards were created to annotate videos, resulting in one of the largest corpora available for researching DGS from a linguistic perspective. More specifically, the DGS-Korpus [15] contains in total approximately 50 h of video material annotated in terms of Sign Language linguistic features, such as the dominant hand, the specific mouthing that accompanies each sign, and the glosses and text annotations in German and English. Additionally, pose features are also provided to allow pose comparisons and analysis. From the annotations’ perspective, one of the most relevant contributions is their gloss annotation standard [16], especially the double-glossing procedure. According to this annotation scheme, there exists a differentiation between gloss types and glosses (or subtypes), which are specified by a citation form. Subtypes stand for additional core meaning aspects, in which normally the sign is accompanied by mouthing that carries the difference in meaning. These subtypes also represent conventionalized form–meaning relations, inheriting the iconic value and citation form from their parent type. In this manner, gloss types are best at expressing a hint to the iconic value of the sign, whereas subtype glosses express a core meaning aspect, containing a larger spectrum of annotated variations. Gloss types and subtypes follow a hierarchical parent–child relationship. For example, the gloss (or lexeme) VIELLEICHT1 is a subtype of the gloss type (or sign) UNGEFÄHR1^ (see an example here: https://dock.fdm.uni-hamburg.de/meinedgs/?id=cfec7516-8966-44ed-84af-41b3dbc1689e#_q=R2xvc3M9IlZJRUxMRUlDSFQxIg&ql=aql&_c=REdTLUNvcnB1cy1yMy1kZQ&cl=5&cr=5&s=0&l=10&m=0, accessed on 20 September 2025). Hence, all the tokens that belong to VIELLEICHT1 (MAYBE1* gloss in English), also belong to UNGEFÄHR1^ (APPROXIMATELY1in English).

However, the annotations of glosses and gloss types are not always mutually exclusive, such as for ICH2^ in which the general meaning coincides with the conventionalized meaning, resulting in the same naming for the gloss and the gloss type. As mentioned before, gloss (or lexeme) annotations contain additional variations associated with the production of the sign, such as variations in the dominant hand (represented by ‘||’ for the case of the left hand), numbers to differentiate lexical variants with exchangeable signs in similar contexts, or the asterisk (*) to differentiate those tokens with variations from the type/subtypes.

Although the DGS-Korpus was originally created for linguistic purposes to study the richness and linguistic characteristics of DGS across different dialects and regions, such as in the work of A. Bauer et al. [17] in which they explore the head nodes in dyadic conversations, differentiating between affirmative nods from feedback nodes, recently, the machine learning community has also shown interest in employing this dataset to evaluate and implement algorithms to improve DGS recognition. However, given the differences between the fields of linguistics and computer science and their final aims, there are still open questions about which are the most beneficial processing steps for this dataset to train accurate machine learning models that could be applied in real-life situations. Some initial approaches are based on selecting random samples of glosses, such as in the article of D. Nam Pham et al. [18], in which they explore and compare the contribution of facial features (i.e., eyes, mouthing, and the whole face) for enhancing SLR in twelve classes extracted from the DGS-Korpus by employing a MultiScale Visual Transformer (MViT) [19] and Channel-Separated Convolutional Network (CSN). However, specific applications could require a more semantically accurate selection of samples in order to recognize specific events, such as affirmations or negations.

2.2. Isolated Sign Language Recognition

As we have commented before, the datasets differ in scope, modality, and annotation granularity, ranging from isolated sign collections to large-scale continuous signing corpora. They also vary in the recording modalities employed, including RGB videos, depth data, and pose or landmark annotations. These variations are also mirrored in the methods and models proposed to advance research in ISLR.

Isolated Sign Language Recognition has been tackled using a number of different input modalities, mainly RGB(-D) video or skeleton/pose data [20]. The first category of methods processes full video frames, while the second relies on landmarks extracted from these frames. Early progress in ISLR based on RGB images largely relied on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Notable work demonstrated a good recognition accuracy on benchmark datasets, laying the foundation for automated Sign Language understanding. This is the case for the I3D architecture, which is based on a 3D ConvNet (I3D) with an inflated-inception CNN, that was originally proposed for action recognition, improving approaches based on 2D CNNs combined with LSTMs [21]. This architecture was subsequently adapted to Sign Language recognition, such as for British Sign Language (BSL) [22], Azerbaijani Sign Language (AzSL) [23], or others [24]. J. Huang and V. Chouvatut [25] also proposed an architecture based on CNNs. In their article, they combined a 3D ResNet and a Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) network, encoding short-term visual and movement characteristics first, and then interpreting these extracted spatial features using a Bi-LSTM, to introduce the temporal dimension. With this approach, they achieved state-of-the-art results on the LSA64 [26] dataset.

However, CNNs inherently focus on a local spatial context through fixed receptive fields and often struggle to capture long-range spatial and temporal dependencies in images and video. These limitations restricted the ability to fully model complex spatiotemporal patterns. As a consequence, in recent years, there has been a shift towards landmark-based approaches [20] employing sequential models. Using landmark-based approaches provides multiple advantages, starting with their low computational latency, compactness of features, and robustness to variations in background, lighting, and appearance, as well as suitability for real-time applications. Additionally, the skeleton data can easily be extracted from RGB video using widely available models [27,28] and frameworks like MediaPipe [29], Yolov8 [30], or OpenPose [31]. This is mainly the reason why they have also been employed in several applications in the literature, from sports analytics, converting 2D representations into 3D meshes [32] to Sign Language Recognition [33,34]. In this family of proposals relying on landmarks (or keypoints), there exist methods based on traditional sequential models (i.e., LSTMs), in which, for example, landmarks extracted from YOLOv8 and optical flow are introduced into a Bi-LSTM to perform Kazakh Sign Language Recognition of 2, 13, and 47 glosses [35].

Nonetheless, RNNs, while capable of temporal modeling, suffer from issues like vanishing gradients and are difficult to parallelize for efficient training. For this reason, transformer-based methods have recently emerged as the dominant approach in the field. Transformers bring intrinsic parallelism during training and show superior generalization, especially on larger datasets. For example, M. Sandoval-Castaneda [33] compared a baseline I3D with four families of video transformers: VideoMAE (a video transformer that learns pixel reconstructions), SVT (a DINO model pre-trained for videos), BEVT (a BERT model pretrained for videos), and MaskFeat (a multiscale vision transformers for masked reconstructions of Histogram Oriented Gradients). In these experiments, they observed that the MaskFeat model surpassed the I3D model pre-trained on BSL for the WLASL2000 dataset, where the MViTv2 is adapted in a first stage of self-supervised learning using the Kinetics400 dataset for action recognition, and then in a second stage with OpenASL, which in the end requires large amounts of training data.

In cases where available resources are limited, a series of light transformers has been proposed too. Initially, the SPOTER [36] architecture was released for performing ISLR in WLASL and LSA64. The main variation of SPOTER over regular transformers is that the decoder receives a one-dimensional query vector, learning projections across the temporal representations generated at the output of the encoder. As a continuation of these transformer-based explorations, different pooling strategies for combining the sequential outputs at the decoder of the transformer models were evaluated in [37] for SLR across two Sign Languages, ASL (with WLASL dataset) and DGS (with the AVASAG dataset).

Other interesting approaches addressed the input features to be introduced into transformers for accomplishing ISLR. M. Pu et al. [38] designed a new approach for efficient skeleton-based ISLR. They introduce a kinematic hand pose rectification method, enforcing constraints on hand point angles. Additionally, the proposal incorporates an input-adaptive inference mechanism that dynamically adjusts computational paths for different sign gloss complexities. With this approach, their proposals achieve state-of-the-art scores, outperforming previous CNN + LSTM methods on a number of ISLR benchmarks such as the WLASL100 [5] and LSA64 datasets.

To conclude, although in the literature several works have addressed and worked before in ISLR employing landmarks versus RGB images, or CNNs versus transformers-based approaches, there is still a gap in addressing real-world applications and specific vocabulary to recognize particular scenarios. In this work, we address the problem of recognizing answers to closed-ended questions with transformer models under low-resource scenarios. Being able to recognize variations in signing when answering these types of questions opens the opportunity to embed these models in any real-world dyadic human–computer interaction.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we will introduce the pipeline for performing the Isolated Sign Language Recognition of polar questions, which consists of several stages. First, we detail the pre-processing of the subset of the DGS-Korpus by explaining how the selection and extraction of the most relevant glosses for detecting affirmations and negations was performed. The second stage focused on feature extraction from the selected samples. Finally, the last stage consisted of the optimization and proposal of a light transformer to perform the recognition, in which we compared a binary approach versus a multi-class approach for the best hyperparameter configuration.

3.1. DGS-Korpus Dataset

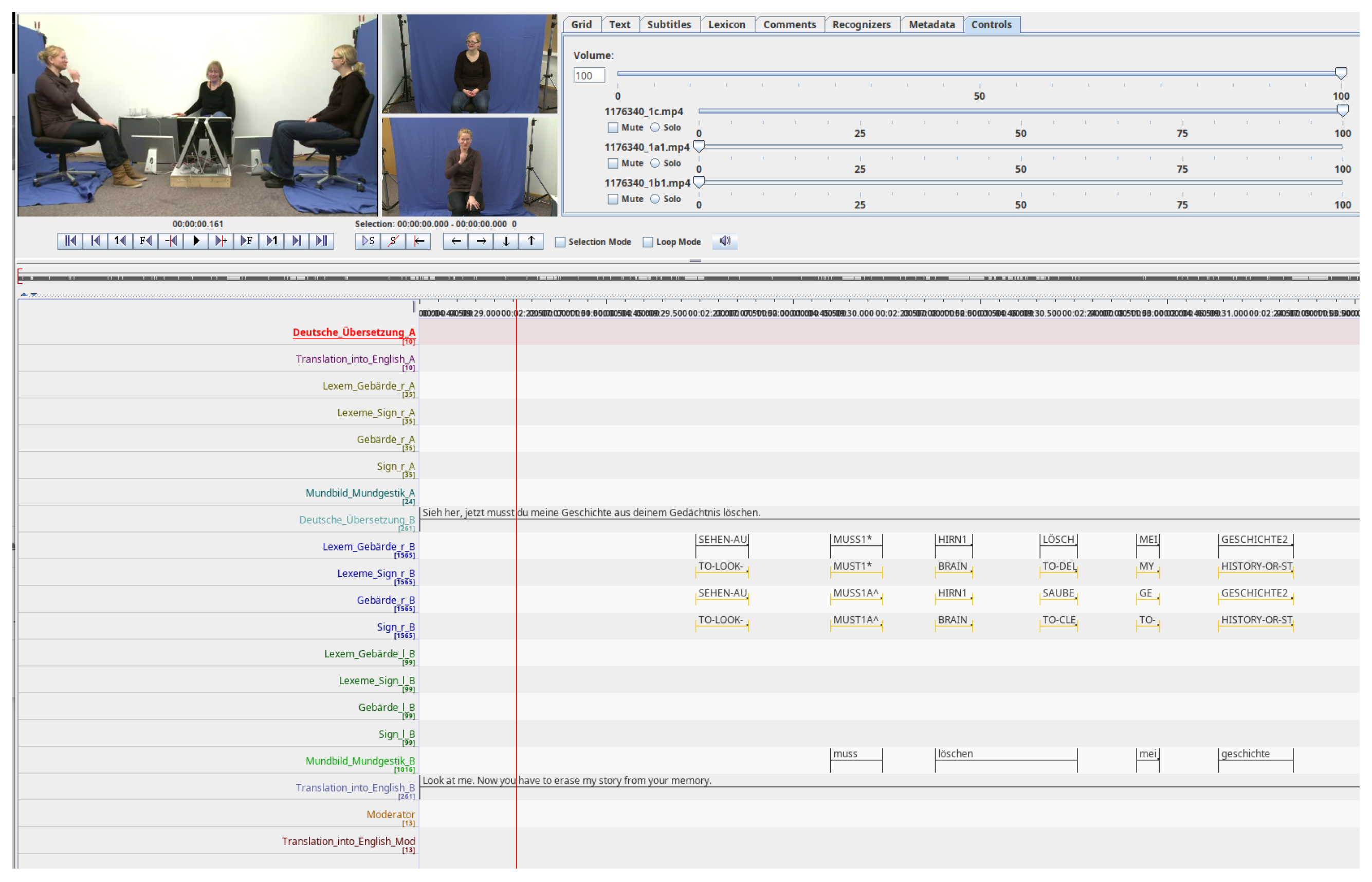

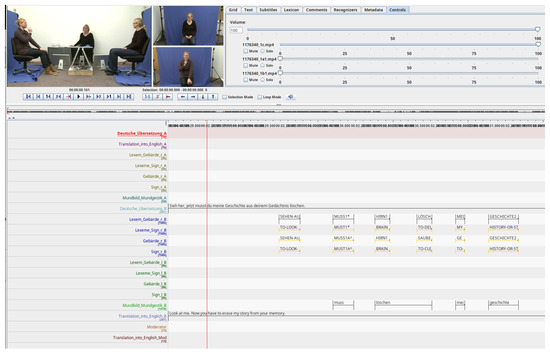

In this article, we focused on performing ISLR in DGS. For this reason, we selected the DGS-Korpus dataset since it is one of the most complete datasets that exists in DGS. As commented before, the dataset contains recordings of signers from distinct regions of Germany, annotated by linguists with glosses and German spoken texts in controlled recording conditions. Although it contains natural conversations about different topics, some of the glosses are limited in the number of repetitions, which is why the analysis of the availability of glosses and variations is a critical step before training and proposing recognizers. In total, the whole dataset is composed of more than 50 h of videos. Each of the participants was recorded by a frontal camera at a resolution of 640 × 360 and at 50 frames per second. Specifically, we employed the version of the dataset available here: https://www.sign-lang.uni-hamburg.de/meinedgs_r4/ling/start-id_de.html (accessed on 20 September 2025). Figure 1 shows a sample with the different tracks annotated for one of the videos of the DGS-Korpus dataset, as well as the recorded perspectives.

Figure 1.

Sample of DGS-Korpus videos with the annotated tracks and the perspectives of the signers, visualized with ELAN tool (version 6.8). Translations of the words of the tracks from German to English: Deutsche übersetzung (‘German Translation’), Lexem_Gebärde (‘Lexem_Sign’), Gebärde (‘Sign’), Mundbild_Mundgestik (‘Mouth image_Mouth Gesture’). According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol.

3.1.1. Gloss Selection

As the dataset is annotated for linguistic purposes, we first explored the types of annotations and the number of available glosses per class, searching for semantically meaningful keywords.

To filter the possible signs that may be related to a specific keyword in German, we extracted the list of annotated signs per participant of the dialogue (‘A’ or ‘B’) from the .eaf files provided, specifically from the following tracks: ‘Gebärde_r_A’, ‘Gebärde_l_A’, ‘Gebärde_r_B’, and ‘Gebärde_l_B’. This family of annotations will be referred to as the ‘gloss type’, according to the annotation in the ANNIS platform. All the types of glosses are indicated by a circumflex at the end, e.g., UNGEFÄHR1^.

Additionally, we also filtered and extracted the lexemes from each participant from the following tracks: ‘Lexem_Gebärde_r_A’, ‘Lexem_Gebärde_l_A’, ‘Lexem_Gebärde_r_B’, and ‘Lexem_Gebärde_l_B’. This family of annotations will be referred to as ‘glosses’, according to the annotation in the ANNIS platform too.

After processing all the videos of our DGS-Korpus version, we obtained a total of 354,065 instances of glosses and gloss types, with 20,897 different glosses and 8769 different gloss types, representing the vocabulary.

We hypothesize that using the glosses could be more beneficial for training models with less noisy samples compared with the gloss types; hence, our selection of samples was performed at this level.

Once the vocabulary of glosses was obtained, we selected the specific classes to train the models by providing keywords and following several steps:

- First, a keyword was selected that contained the expected semantic meaning and the gloss name (i.e., ‘Ja’ or ‘Nein’ in our case).

- Second, this keyword was passed to a Python script that selected all the matching lexemes, signs or gloss types that contained each keyword in our vocabulary.

- Finally, this process was repeated iteratively for refining the keyword, discarding non-suitable samples for our scenario, and concluding with a final manual selection and filtering of the non-relevant glosses.

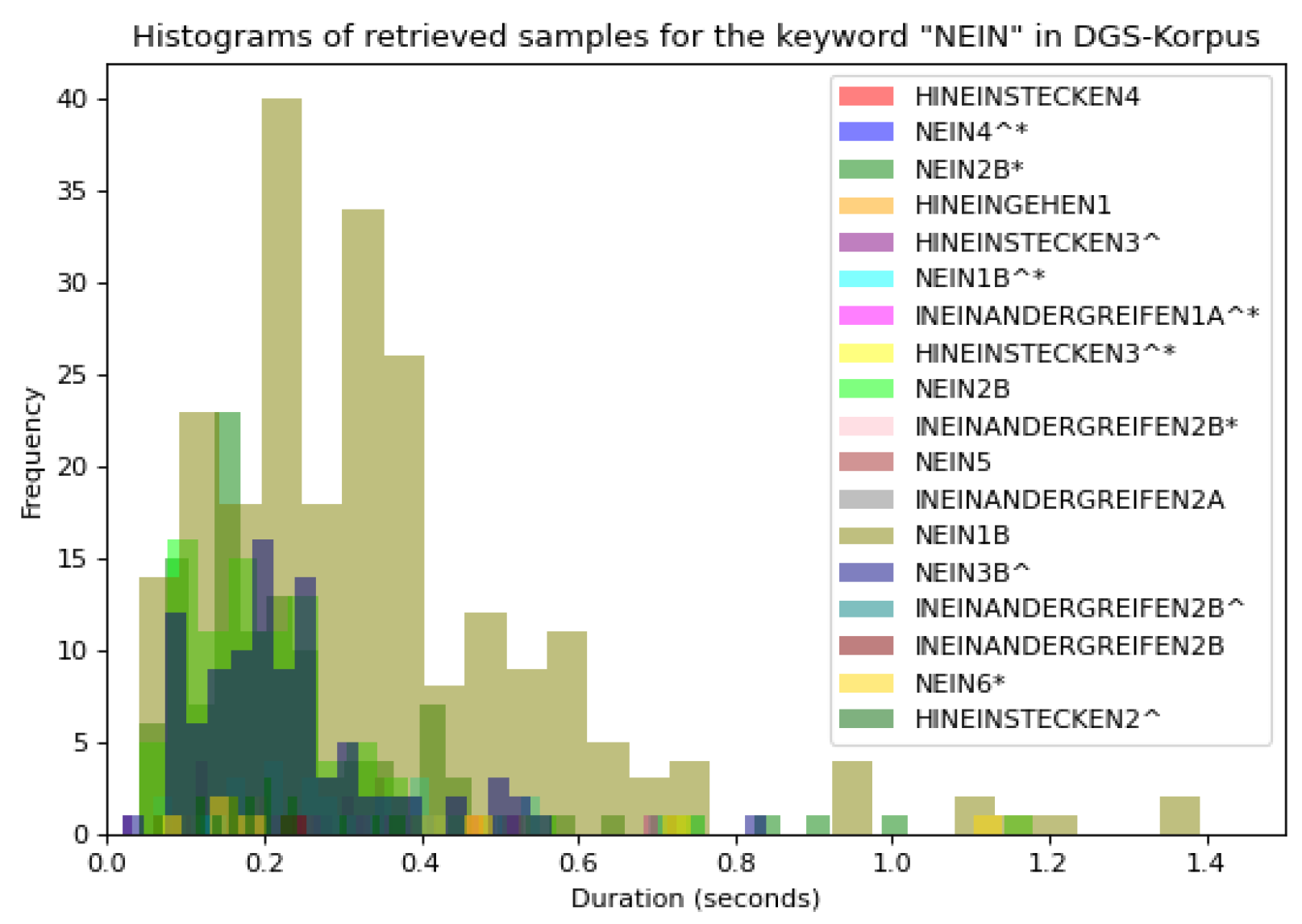

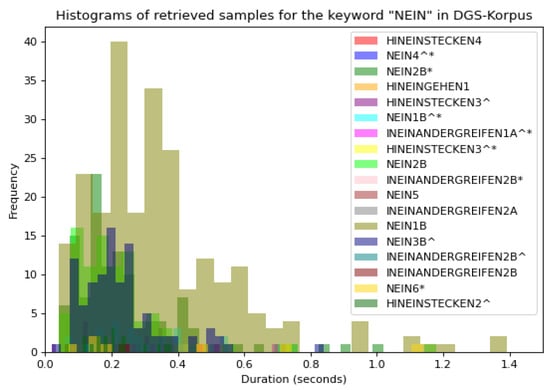

For instance, for the ‘Ja’ keyword, the first matching returned 103 different glosses containing the keyword ‘Ja’; however, some of them did not have the same semantic meaning of ‘Ja’ (‘yes’ in German), such as ‘JACKE1’ or ‘JAHR1A’, hence, a second iteration and filtering were required. Similarly, for the ‘Nein’ class, we obtained 44 possible sets of glosses matching partially with the keyword ‘Nein’—18 of the total 44 classes are displayed in Figure 2 with their variations in duration, which required a second filtering.

Figure 2.

Histogram of 18 out of 44 retrieved glosses for the keyword ‘Nein’. The X-axis displays the duration in seconds of the retrieved videos and the Y-axis displays the number of each video. Colors are assigned according to the glosses’ names. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol.

After obtaining these classes, the second iteration of manual filtering started, by keeping only the glosses that matched the semantic meaning of ‘yes’ or ‘no’, obtaining as a result the final list of glosses which is shown in Table 1. Notice that in this procedure, we were employing the glosses annotated by the linguistics of the corpus; hence, if some glosses related to nodding, for example, were not annotated as lexical signs but as productive signs with a different name than the actual meaning, these glosses would be discarded in the current filtering procedure.

Table 1.

Retrieved glosses and number of samples obtained given the specified keyword. Bold: the selected gloss (or class) used for training our models. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol.

From this list of classes and in order to ensure that models have enough samples to be trained, only the glosses with at least 10 samples were kept for the dataset, resulting in a total of 20 classes for the multi-class classification scenario.

Regarding the segmentation of the videos of glosses, different conventions can be applied. One option is to define the endpoint of a gloss as the starting timestamp of the subsequent gloss (resulting in no gaps in the annotation tracks), while another is to exclude transitional movements from the gloss boundaries [16]. In our work, we adopt the second strategy to avoid introducing noise to the annotations, and hence, to the models.

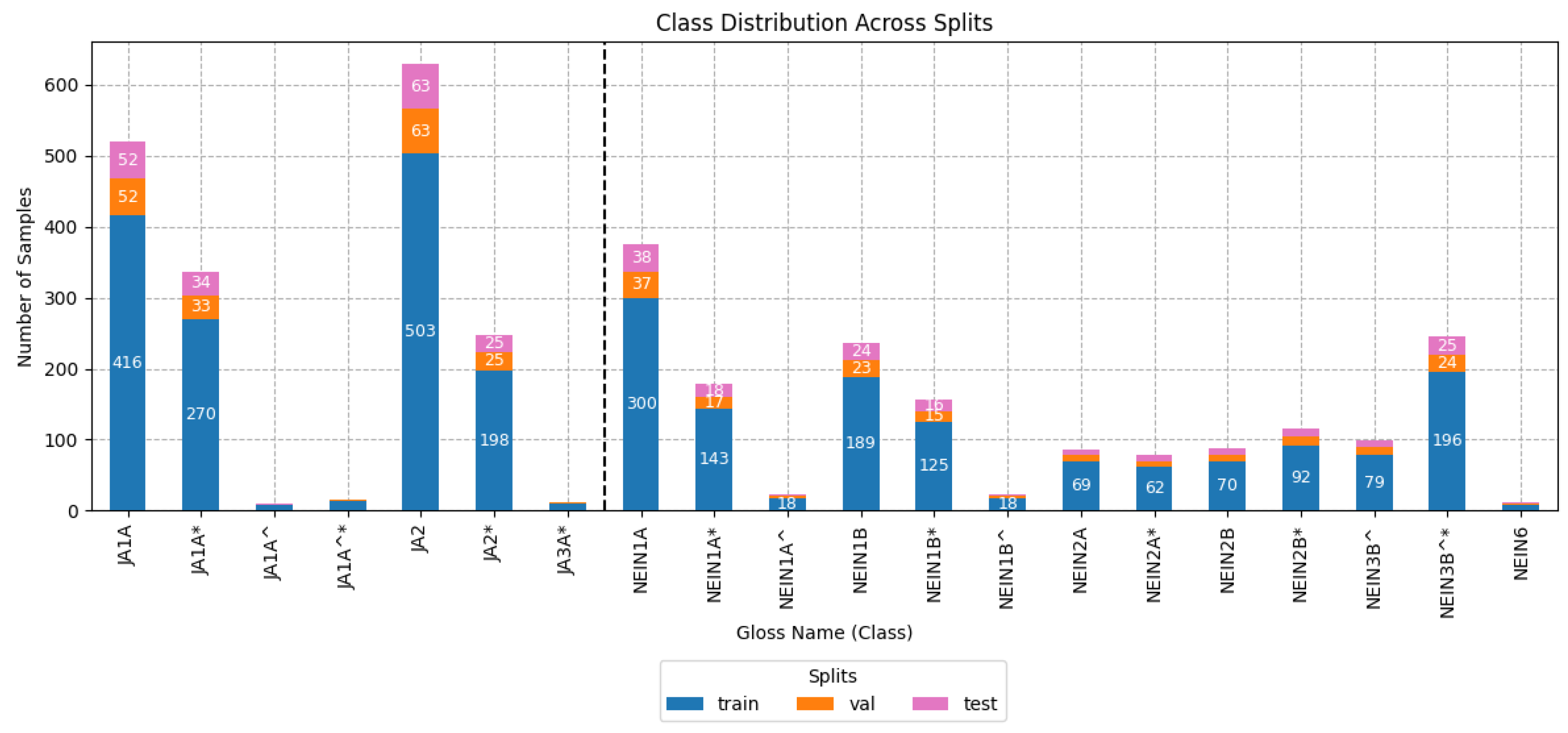

3.1.2. Dataset Splits

Once the glosses were selected and segmented, the dataset was divided into train, validation, and test sets following a gloss-based random stratified division with a percentage of 80, 10, and 10 for the training, validation, and test sets, resulting in 2788 samples for training, 348 for validation, and 349 testing. The division of the dataset was not performed in a subject-wise manner, instead it was performed to ensure enough samples of each class for each of the variations of the glosses-based experiment. Hence, the same subject may appear in the training set as well as the validation or test set, performing the same signs or other similar signs.

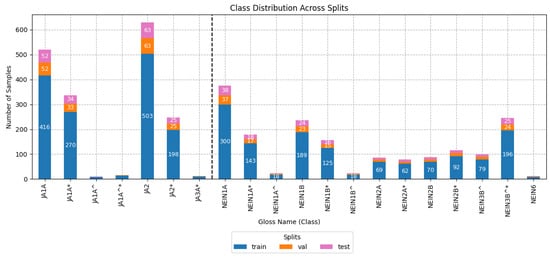

Figure 3 shows the number of samples per gloss for the training, validation, and test sets for the multi-class scenario. The vertical dashed line divides those glosses that have the semantic meaning of ‘yes’ on the left and ‘no’ on the right. As can be observed, this dataset consists of a challenging multi-class recognition task given the imbalance between each of the glosses and the similarity in the signs of some of them.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the class distribution of affirmation/negation divided by the glosses extracted from DGS-Korpus. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol.

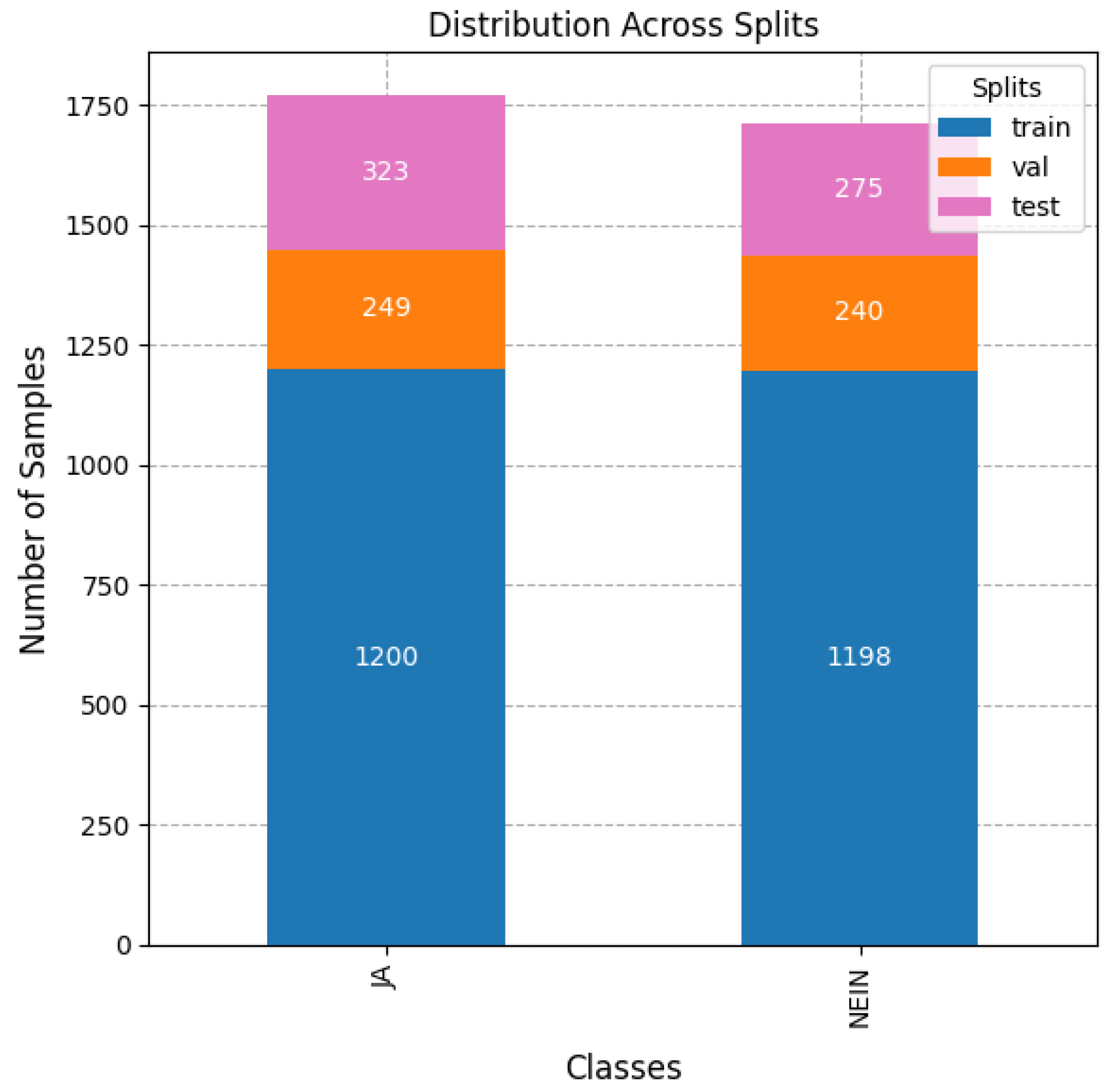

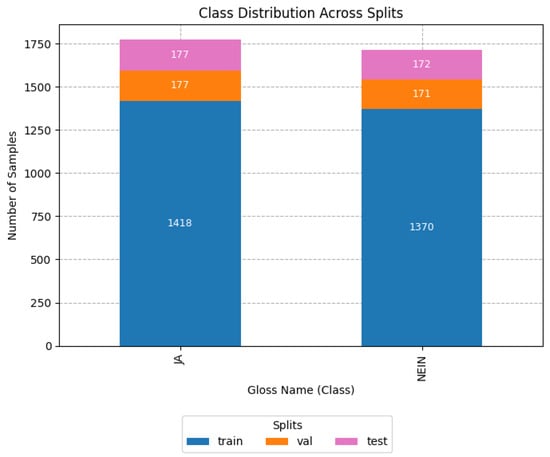

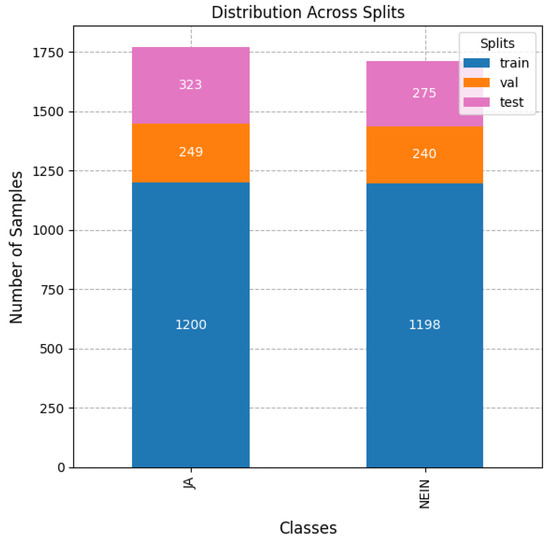

As mentioned before, in this article, we were interested in evaluating the differences in training the models for performing classification based on glosses or based on their semantic meaning. For this reason, from the same splits mentioned before, a second binary dataset containing only the semantic classes (yes or no) was created from the agglomeration of previous glosses, as displayed in Figure 4. As can be observed, in this case, the dataset was balanced in the number of samples per class.

Figure 4.

Histogram of the class distribution of affirmation/negation with glosses aggregated by semantic meaning. ‘JA’ in German is translated to ‘Yes’ in English and ‘Nein’ is translated as ‘No’ in English.

Note that to explore the effect of dividing the dataset subject-wise, we performed an additional division of and training with the best performing model in Section 4.6, as well as a first generalization study in Section 4.5.

3.2. Feature Extraction

After deciding the set of glosses to use in the dataset, the frames of the videos were extracted in parallel, employing the ffmpeg library.

Once the frames were obtained for each of the glosses, we extracted landmarks from these frames to train the models. We decided to extract and evaluate different combinations of landmarks using the MediaPipe library due to its lightweight and use in multiple applications [37,39]. As Sign Language is composed of manual and non-manual cues, we compared the difference of employing only landmarks corresponding to the right and left hands (referred in the experiments as ‘RH|LH’), or landmarks of the hands plus the pose (named as ‘RH|LH|P’) to evaluate whether pose information was complementary for detecting affirmation and negations in DGS. Specifically, for the hands approach, we extracted 21 landmarks per hand from the MediaPipe-Holistic detector, resulting in 42 landmarks for both hands, and 33 additional landmarks for the approach employing a pose, resulting in a total of 75 keypoints.

Additionally, we explored whether the z coordinates (or depth distance) could provide relevant cues for the understanding of the signs or not. With this aim, we performed ablation studies with the coordinates X and Y; or X, Y, and Z.

After the feature extraction, we applied the same translation normalization as in a previous study [36] to each component of the landmarks, re-adjusting the origin of coordinates to the center of each frame with the following operations:

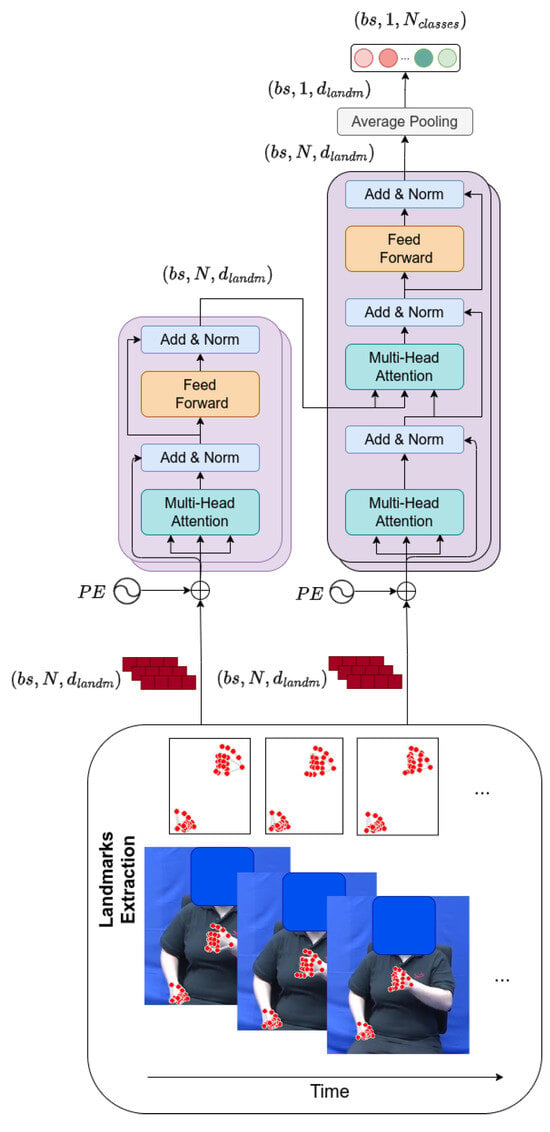

3.3. Transformer Architecture

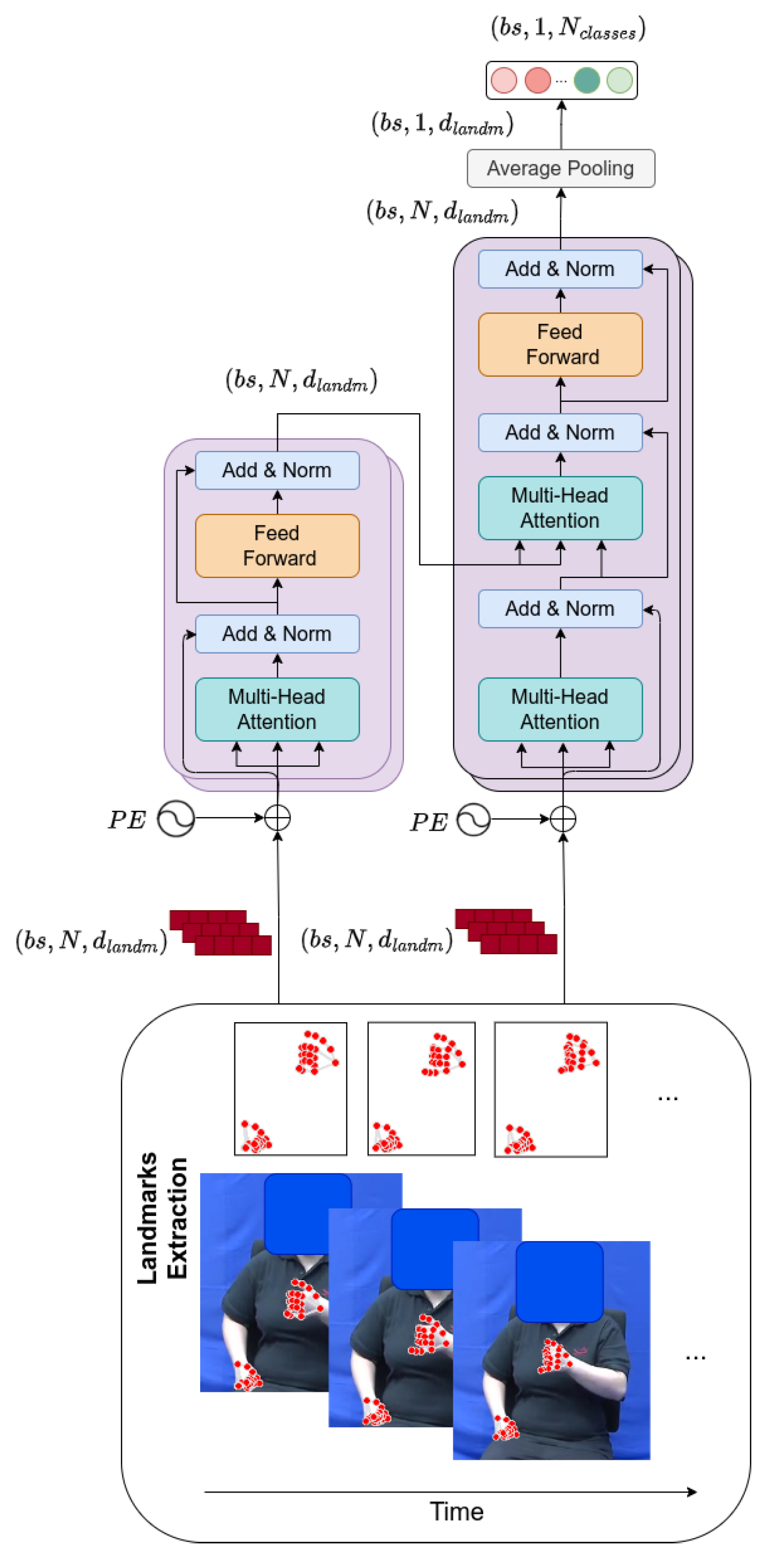

In this work, we employed a transformer model. This model receives as its input the flattened coordinates of the extracted landmarks as a temporal sequence of dimension , in which represents the batch size, N stands for the maximum temporal sequence length that the transformer model accepts in number of frames (in our case fixed to 189 frames), and represents the number of landmarks with their flattened coordinates (i.e., number of landmarks multiplied by 2 for the case of using only x and y coordinates, or multiplied by 3 for the case of using also the z component). In more detail, the length of the sequences was fixed to 189 due to the maximum length in the sample of the glosses in the DGS-Korpus for the specific yes/no signs. For a practical application in continuous scenarios, windows of the same length should be employed, truncating larger segments and including padding in the case of shorter segments.

These landmarks are introduced at the input of the encoder and decoder for further processing by the attention mechanisms and feedforward layers contained in each of the encoder and decoder modules.

In our experiments, we kept the number of sequentially connected encoder and decoder blocks to 6, as in the original transformer proposed in a previous study [40], as well as the same sinusoidal Positional Encoding, defined in Equation (2).

where N stands for the temporal timestep, i for the ith dimension of the Positional Encoding vector, and being the embedding vector space, which in our case is equivalent to the number of input features.

However, we also performed ablation studies removing this additive Positional Encoding under the assumption that it could mask important information carried by the input landmarks, given that they vary in ranges of values between −1 and 1. Similarly, and following recent transformer proposals for ISLR [37], we compacted the temporal dimension at the last block of the decoder by employing Global Average Pooling. This specific type of layer for compacting information has the advantages of not requiring trainable parameters, applying a weighted sum over the outputs. Figure 5 shows the architecture of the transformer model.

Figure 5.

Transformer architecture, including sinusoidal Positional Encoding and average pooling. At its input, it receives the coordinates of the extracted landmarks. Acronyms: stands for batch size, N for number of frames, and for the number of input features corresponding to the landmarks, and varies from 2 for the binary case up to 20 for the multi-class scenario. The red dots refer to the extracted landmarks from MediaPipe.

Finally, different combinations of hyperparameters were explored, considering batch sizes of size 32, 128, and 224; SGD or AdamW optimizers; learning rates of 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001; and clipping the weights in the range of −0.5 to 0.5, or not during training. As the number of heads of a transformer should be divisible by the input embedding at the encoder and decoder (), we tested transformers with 5 or 6 heads. Depending on the problem to be solved, whether binary classification or multi-class classification, the number of neurons of the last linear layer of the transformer changed from 2 to 20 neurons, respectively, which is to be adjusted to the expected number of classes for each classification task. For the remaining configurations, we employed cross-entropy loss with random weights initialization and trained for a maximum of 300 epochs, keeping the remaining hyperparameters as the default configured in the Pytorch library version 2.8.0, but fixing the randomness and the seed to 379 with the following Listing 1:

| Listing 1. Setting random seeds for reproducibility. |

|

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of our models, we employed three metrics: accuracy, Weighted F1 (W-F1), and Macro F1 (M-F1). These metrics provide complementary perspectives, which is particularly valuable in settings with class imbalance.

- Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly predicted instances over the total number of predictions. While it provides a general overview of model performance, it can be misleading in imbalanced datasets, as a high accuracy can be achieved by favoring majority classes.

- Weighted-F1 considers both precision and recall by computing the F1 score for each class and then averaging them with weights proportional to the number of true instances in each class. This ensures that classes with more samples have a greater influence on the final score, making it sensitive to class distribution.

- Macro-F1, by contrast, calculates the unweighted average of F1 scores across all classes, treating each class equally regardless of its frequency. This makes it especially useful for assessing the performance of underrepresented or minority classes.

In the above Equations, N represents the total number of classes (glosses in our case) and is the percentage of samples per class i. , , , and stand for the number of true-positives, true-negatives, false-positives, and false-negatives, respectively. These metrics are attached to their confidence intervals in order to show statistical significance when there is no overlap between intervals.

To estimate the confidence interval (CI), Wald’s confidence interval (or normal approximation interval) for binomial proportions is utilized. Given the following:

- X = number of observed successes;

- n = original sample size;

- = observed sample proportion.

The Wald confidence interval is then

where is the critical value from the standard normal distribution, (e.g., for a CI).

Additionally, to measure latency, FLOPS, number of parameters, and energy consumption, we employed the Python 3.12.2 libraries of ptflops (version 0.7.5) and codecardon (version 3.0.6) over 500 samples to calculate an average number. All the experiments were tested on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, we summarize the main results obtained in our proposals. First, we will introduce the hyperparameter search performed to discover an optimal architecture. Later, we compare the contribution of introducing landmarks of poses in addition to the hands, as well as the z component, to enhance the performance of the models. Subsequently, we evaluated the contribution of Positional Encoding to the best combination of hyperparameters. Finally, we conclude the section with the study of models for semantic classification or gloss recognition, with an analysis of the errors and missclassified samples per problem.

4.1. Transformer Architecture: Hyperparameter Exploration

As a first approach, we performed a hyperparameter search to create a first competitive transformer to explore subsequent research questions. As commented in Section 3, we explored the effect of different optimizers, batch sizes, learning rates, and clipping of the weights. The transformer model was constant across all the experiments using the version with Positional Encoding, and five heads for the attention mechanisms. At the input, we introduced hands and pose features (75 landmarks in total), with their x, y, and z coordinates of the landmarks, resulting in 225 input features per timestep.

From Table 2, we can observe that two main configurations obtain the highest M-F1: first, the one consisting of employing the SGD optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01, achieving an M-F1 of 80.10 when the weights are not clipped; and second, the configuration employing the AdamW optimizer with batches of 128 and a learning rate of 0.0001, also without clipping the weights achieving an M-F1 of 81.64. From this analysis, we concluded that clipping the weights did not provide any advantage to the evaluated configurations during the learning stage of the model, and in fact, on some occasions, including the clipping has a negative effect, decreasing the performance. Hence, as a result of this first analysis, we decided to continue with the AdamW configurations mentioned before, testing with 128 or 224 as the batch size.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter comparison for affirmation/negation answers of the proposed transformers. ‘✓’ indicates the clipping of the weights, whereas ‘✗’ indicates not clipping the weights. ↑ arrows indicate the higher, the better. In bold, the top results.

Additionally, as baseline models, we compared the transformer models with LSTMs trained with different configurations. We explored variations in the number of layers (from 1 to 4 layers) and with the number of neurons per cell of 50, 100, 200, and 300. In these experiments, we employed the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, a batch size of 32, and the (x,y) coordinates extracted from the right and left hand landmarks. In all the cases, the model was not able to converge, as is reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Baseline comparison with transformers for the binary task. ↑ arrows indicate the higher, the better. In bold, the top results.

4.2. Input Features Analysis: The Contribution of the z Component and Pose Versus Hand Landmarks

Focusing first on the employed coordinates for the training (xyz or xy), we can observe in Table 4 that employing the z component (depth) results in no significant increases in the performance, and actually for the first four rows, there exists a slight decrement in W-F1 and M-F1 (i.e., for the batch size of 128, and for the batch size of 224). A similar effect can be observed in the second half of the table for the experiments employing only the right and left hand landmarks (i.e., rows with the column of the body parts equal to ‘RH|LH’), in which the performance is similar using the z component than when it is removed.

Table 4.

Results for the binary classification problem of affirmation/negation recognition obtained with the transformer with PE. RH = right hand; LH = left hand; P = pose. ↑ arrows indicate the higher, the better. In bold, the top results.

These experiments indicate that the depth component seems not to be as relevant for the recognizer as the position of the hands and body for distinguishing between affirmations and negations in the specific subset of the DGS korpus. In our experiments, given that introducing additional components at the input (e.g., 225 input features versus 150 for the pose and hands approach) also increases the complexity of the model, the decision was made to remove the z component since it could introduce noise but not affect the final performance. Some plausible explanations for why the depth information is not reporting an additional gain could be related to the precision of MediaPipe (version 0.10.21), since estimating depth is considered a more complex problem than detecting keypoints in an image, at least when estimating only from one single viewpoint. However, further to the assumption that this component is not relevant in Sign Language, some of the possible explanations about the drop in performance when this component is added could be derived from Mediapipe’s limitations, such as a depth estimation artifact, the addition of complexity to the problem when adding extra features, or the actual camera setup in the DGS-Korpus.

Regarding the second question of whether differentiating between signs in our dataset only using the hands is sufficient or whether the pose is also required, we compared models fed accordingly with landmarks belonging to the whole body or just to the hands. The results show that there are no major statistically significant differences in employing the whole body plus hands (i.e., the results in the column ‘RH|LH|P’) versus employing only the hand information (i.e., ‘RH|LH’). This observation may suggest that for this task, most of the relevant information for distinguishing between classes is carried out by the hand cues, in contrast to the body position. Additionally, this suggests there might be a correlation between the pose and hand landmarks, resulting in no additional information gain for the model when they are combined.

Finally, to compare the proposed transformers, we ran several experiments with LSTMs as a baseline for the comparison. In all the experiments, the models did not converge as expected, reaching a maximum W-F1 of 34.13% and an M-F1 of 33.65%, which is a statistically significantly lower performance compared with the top transformer.

4.3. Ablation Study of the Sinusoidal Additive Positional Encoding

Recently, previous works have explored how the original sin–cos additive Positional Encoders may impact the performance of models when transformers are trained from scratch as classifiers [37]. In previous works, it was reported that in resource-limited scenarios, the inclusion of this type of Positional Encoding could damage the convergence and training of the models, resulting in sub-optimal performances. For this reason, to optimize our proposed transformer, we also explored the effect of removing the Positional Encoder from the architecture. Table 5 shows the results of the top performing combinations of parameters discovered in previous experiments after removing the Positional Encoding from the input to the first blocks of the encoder and the decoder of the transformer. As can be observed by comparing the common configurations from Table 4 and Table 5, there is a statistically significant gain when the sinusoidal PE is not included in the architecture. For illustration, in the case of using a batch size of 128 and only the x and y coordinates of the hand landmarks, the accuracy, W-F1, and M-F1 increase by 17.48, 17.74, and 17.77 percentage points, respectively, with respect to the transformer version with the PE. It is hypothesized that as the sinusoidal PE varies in the range of −1 to 1, it could mask the information carried by the landmarks and is not able able to recover it during the training stage, resulting in slower or non-convergence.

Table 5.

Results for the binary classification problem of affirmation/negation recognition obtained with the transformer without PE. ‘✗’ indicates the removal of the PE. ↑ arrows indicate the higher, the better. In bold, the top results.

Regarding the employment of hands versus hands plus pose, in the obtained results with the transformer without the sinusoidal PE, the results followed a similar trend to those observed with PE in Table 4. In both cases, the performances reached by the models are overlapped in terms of their confidence intervals, which indicates no statistical significance between them. For this reason, and following the simplicity criteria stated before, further explorations were performed only with models using the hands instead of the whole body. Note that this result does not mean that facial information is not relevant; but, in a simplified binary task of distinguishing between signs for ‘Ja’ and ‘Nein’, hands seems to play a relevant role in the detection of the signs for distinguishing between them. Based on the current dataset, gloss recognition, and scenario, the results could vary depending on the similarity between glosses, e.g., in a dataset in which the target is to distinguish glosses with similar HamNoSys, likely other cues such as facial expressions and mouthing would play a more significant role. Similarly, if occlusions exist, potentially non-manual features would become more relevant as a backup channel; however, in DGs-Korpus, occlusions are rare because it was recorded in a controlled environment.

To conclude this section and provide a final summary about the energy consumption and size of the best performing model, the model achieved a 97.71% accuracy performance in the test set and the size of the model contained 4.67 M of parameters, which is lighter than the SPOTER versions of transformers and I3D models, according to the results reported by Boháček M. et al. [36]. Regarding the energy consumption and FLOPS, it obtained an average of 1.2 M of FLOPS, calculated as double the MACS by the ptflops python library. Finally, the average latency per prediction was 3.574 ms, evaluated as an average of 500 prediction runs.

4.4. Semantic Recognition Versus Gloss Recognition

The last research question that we pursued was to explore whether there exist differences between training models at the semantic level (in a binary classification task) or at the gloss level (in a multi-class classification problem) and whether one of these strategies could report advantages at the prediction stage.

Previously presented results explored the top configurations at the semantic level in a binary task. For this reason, and to ensure a fair comparison for the gloss recognition evaluation, we repeated the experiments of the top-most promising parameters explored in the semantic recognition approach. Specifically, we evaluated the combination of hyperparameters that appear in Table 6, for the transformer without PE model, AdamW optimizer, and with 300 epochs, highlighting in bold the best combination obtained for the W-F1 in the validation set.

Table 6.

Hyperparameter search for the multi-class (or gloss recognition) scenario. In bold, the best combination of hyperparameters in terms of W-F1 in the validation set.

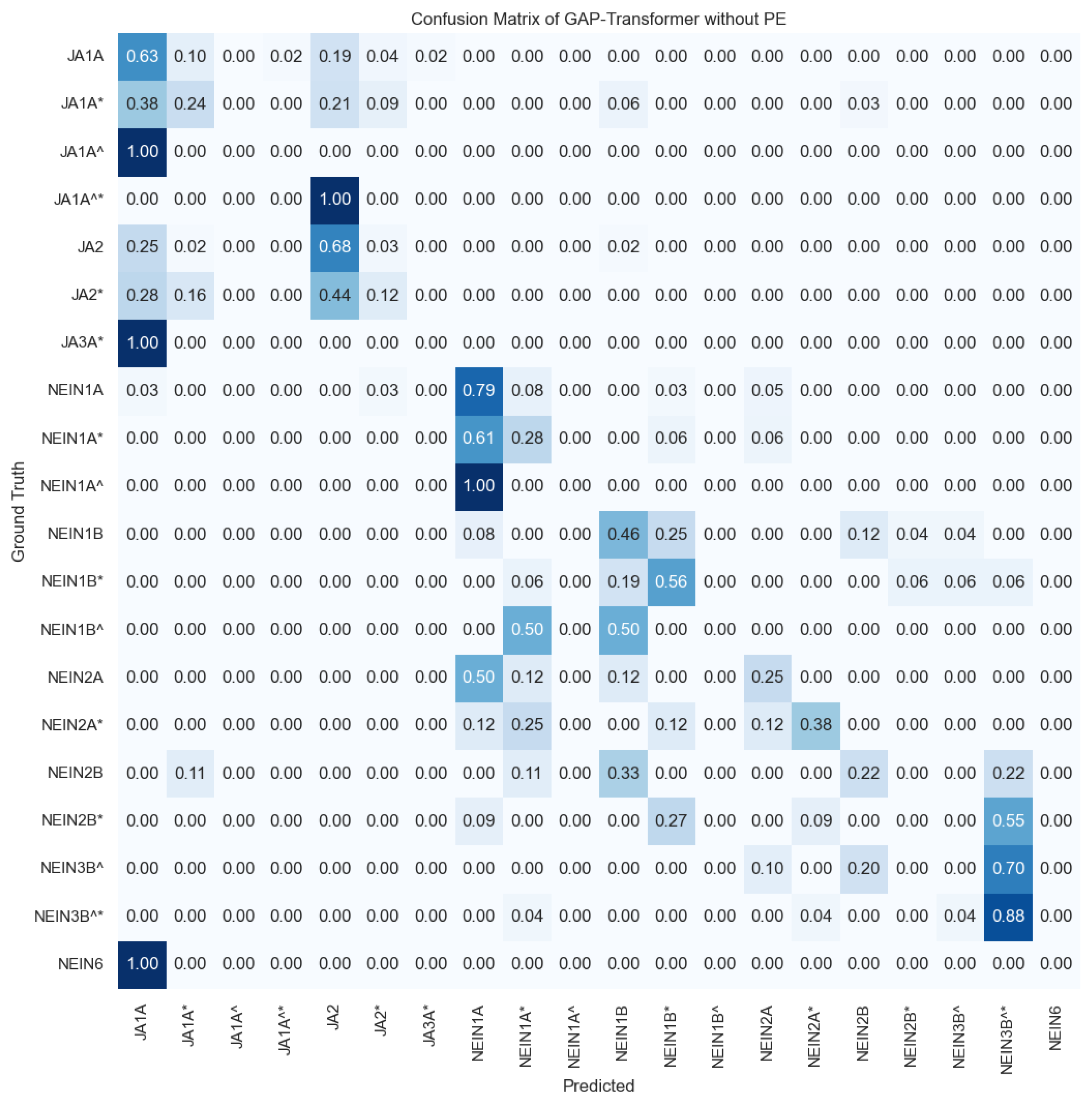

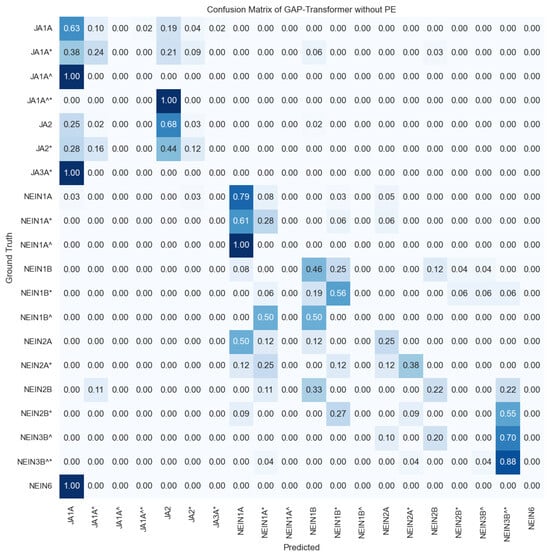

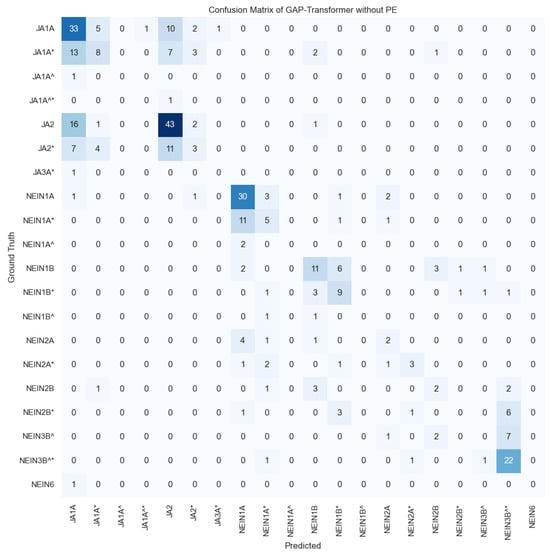

For the top combination of hyperparameters highlighted in bold in Table 6, the transformer without PE achieved an accuracy of 49.00%, W-F1 of 45.20%, and M-F1 of 26.19% for the multi-class problem with 20 classes, with the confusion matrix for the test set displayed in Figure 6. This model surpassed the ZeroRule classifier by +30.95 percentage points in accuracy, +39.68 in W-F1, and +24.66 in M-F1, demonstrating a learning capability.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for the imbalance multi-class (gloss recognition) results for the transformer without PE, introducing the landmarks of the xy coordinates of the hands. The confusion matrix is normalized per number of ground truth samples in the test set (i.e., per row), hence values vary from 0 to 1 and colors indicate the percentage of samples correctly or incorrectly detected per row. The darker the blue, the higher the proportion. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol. ‘JA’ in German is translated to ‘Yes’ in English and ‘Nein’ is translated as ‘No’ in English.

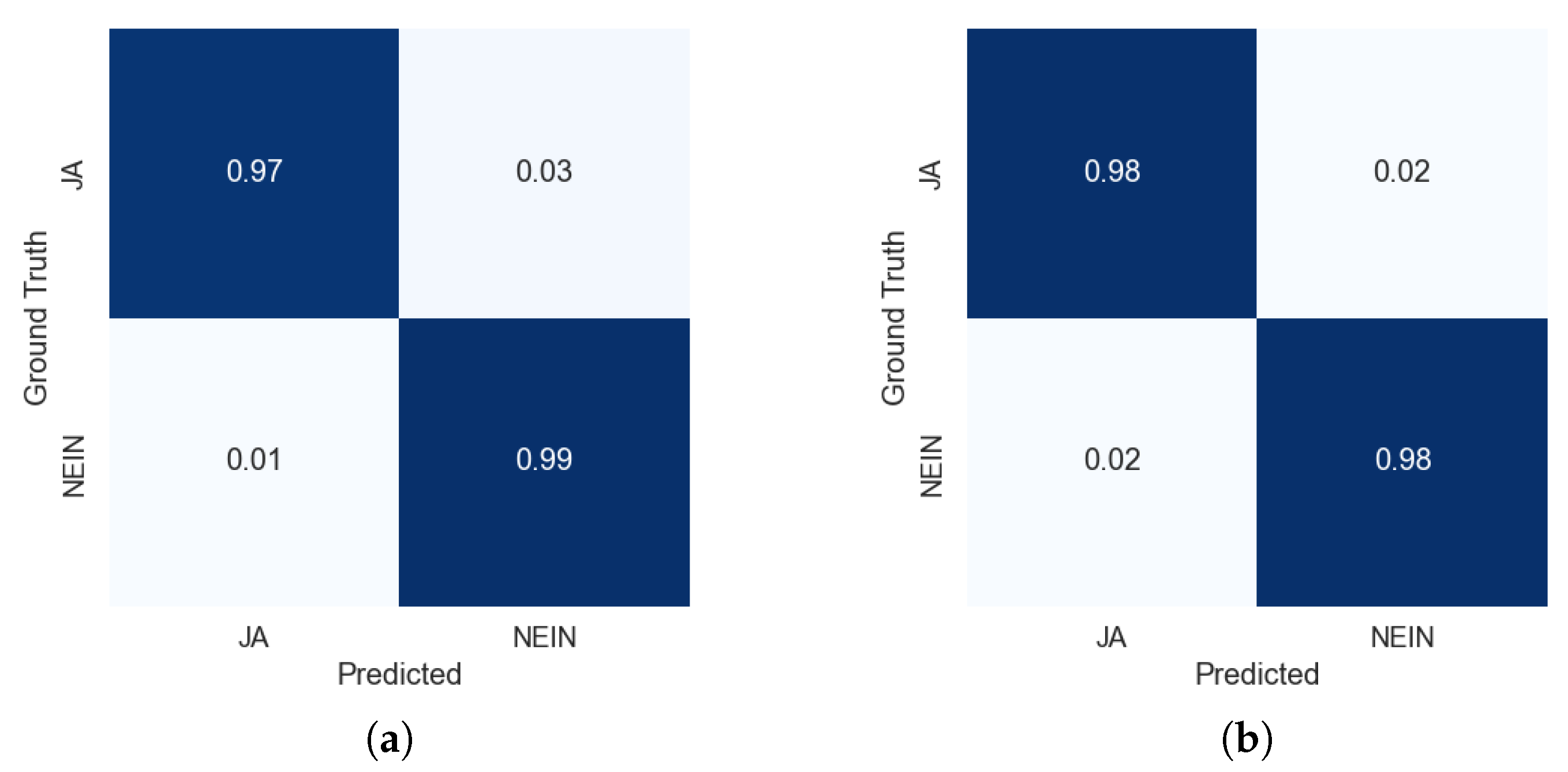

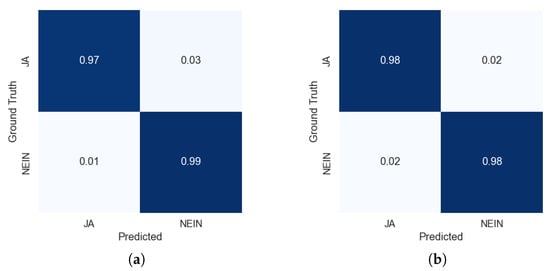

As can be observed in the confusion matrix of Figure 6, most of the errors made by the model are between glosses with the same meaning, for example, in the first column there are several mispredictions confusing the class ‘JA1A*’ with ‘JA1A’, or ‘JA3A*’ with ‘JA1A’, among others. However, when these classes are collapsed to the binary problem, i.e., all the variations of ‘Ja’, such as ‘JA1A’, ‘JA2’, etc., are considered as belonging to the class ‘Ja’, and all the variations of ‘Nein’ such as ‘NEIN1A’, ‘NEIN1A*’, ‘NEIN1B’, etc., are considered as belonging to the class ‘Nein’, the performance of the model reaches an accuracy of 97.71%, W-F1 of 97.71, and M-F1 of 97.71 for the two-class semantic problem. These results are comparable to those obtained for the top model trained only to distinguish between ‘Ja’ and ‘Nein’ samples, which achieved exactly the same performance with an accuracy of 97.71%, W-F1 of 97.71, and M-F1 of 97.71, reported before in Table 5.

Delving into the study of the differences between the models trained for binary classification (semantic recognition) versus the model trained for multi-class recognition (gloss recognition), we can observe from the binary confusion matrices in Figure 7 that predictions are similar, with the multi-class scenario being equal in terms of the distribution of errors between false positives and false negatives, but overall their performance is fairly similar.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrices of the test set extracted from the top models trained on the semantic recognition task (binary) and the gloss recognition task (20 classes) assimilated to the binary recognition task. ‘JA’ in German is translated to ‘Yes’ in English and ‘Nein’ is translated as ‘No’ in English. Confusion matrices are normalized by the number of samples in the ground truth (rows). (a) Semantic recognition results trained on the binary case. (b) Multi-class gloss recognition results assimilated to the binary case.

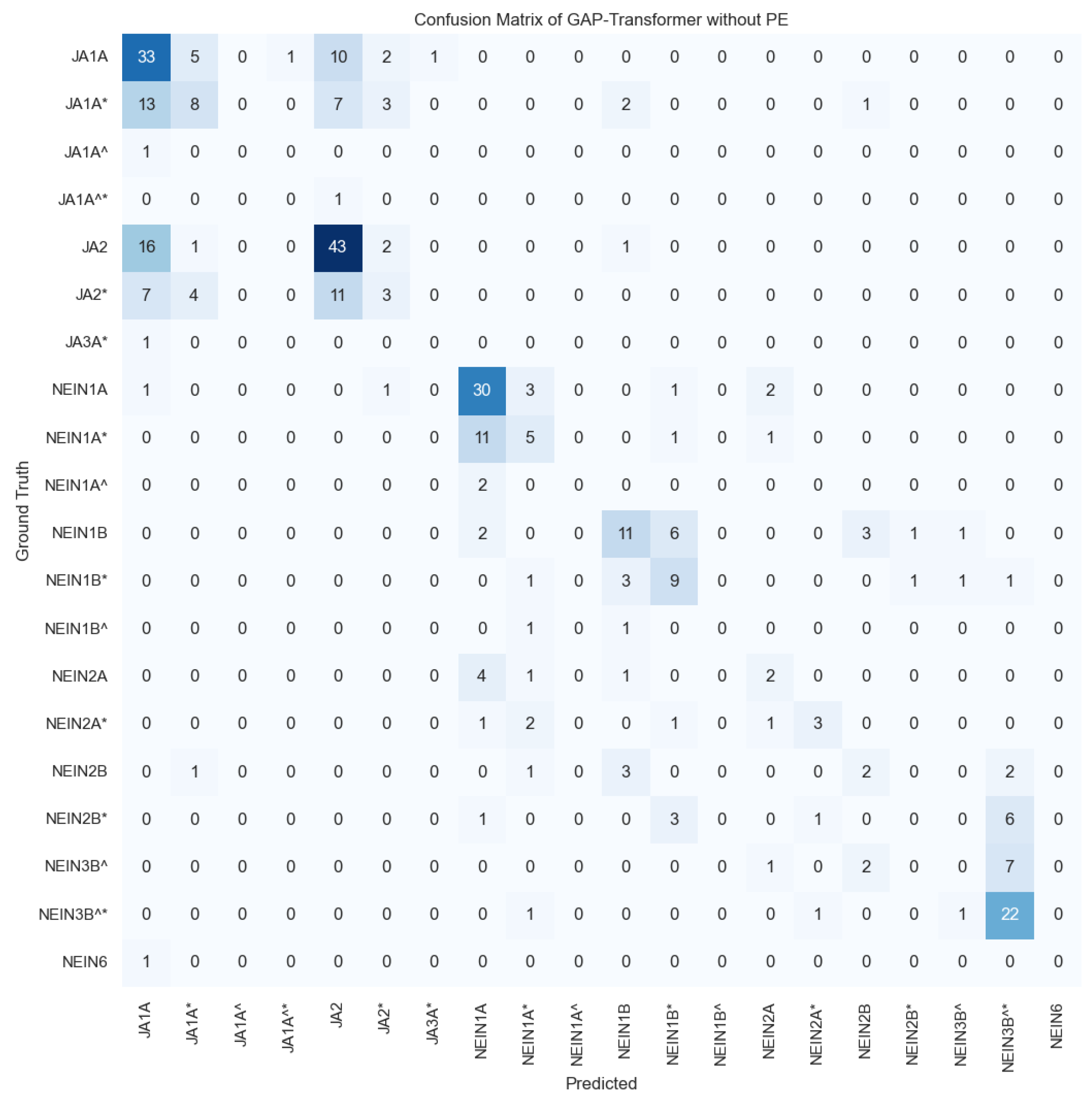

To understand which are the most confused classes in terms of the number of samples available and to draw more conclusions, in Figure A1 of Appendix A, we included the confusion matrix of the top model with the absolute number of samples correctly and incorrectly predicted. Starting with the errors in the semantic group of ‘Ja’, we can observe that those classes with a larger number of training samples (i.e., ‘JA1A’ and ‘JA2’) are the most recurrent predictions of the model. Especially noticeable are the predictions of the model for the case of ‘JA2*’ in which the major number of confusions happens with the class ‘JA2’ (11 times) and the class ‘JA1A’ (7 times). For the semantic group of ‘Nein’, a similar trend is observed in which the most numerous classes (‘NEIN1A’ and ‘NEIN3B^*’) conglomerate the majority of predictions. However, given that in this case the two most numerous classes have fewer samples, errors are more equally distributed across different glosses. Note that for the class ‘NEIN6’ in the test set there exists only one sample given the reduced number of samples of this class in the dataset; hence, as it is confused with ‘JA1A’, the confusion matrix shows a 100% rate of mispredictions for that class.

For the transformer model not employing Positional Encoding, in the binary case, only eight samples were not correctly predicted in the test set, as is shown in Table 7, in which the errors are analyzed by glosses. These samples corresponded with the glosses ‘JA1A*’ (three times mispredicted as ‘Nein’ instead), ‘JA2’ (one time), ‘JA2*’ (one time), and ‘JA3A*’ (one time). For ‘Nein’, there were two confusions, one ‘NEIN1A’ and one ‘NEIN6’, with the ‘Ja’ class. Figure 7a shows the confusion matrix for the binary case, normalized by the number of samples in the ground truth per class (rows).

Table 7.

Fine-grain analysis of mispredictions between the positive/negative answer classes, divided by glosses, for the GAP model trained on the semantic (or binary) problem. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form.

For the transformer model not employing Positional Encoding for the multi-class case reduced to two classes, only eight samples were not correctly predicted in the test set too. This is shown in Table 8, in which the errors are analyzed by glosses for the binary case.

Table 8.

Fine-grain analysis of mispredictions between the positive/negative answer classes, divided by glosses, for the GAP model trained on the gloss recognition (or multi-class) problem. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form.

These samples corresponded with the glosses ‘NEIN1A’ (two times mispredicted as ‘JA1A’ and ‘JA2*’ instead); ‘NEIN2B’ incorrectly predicted as ‘JA1A*’; and ‘NEIN6’ incorrectly predicted as ‘JA1A’. For the false negatives, we have ‘JA1A*’ incorrectly predicted two times as ‘NEIN1B’ and ‘NEIN2B’; and ‘JA2’ incorrectly predicted as ‘NEIN1B’ once. Figure 7b shows the confusion matrix for the binary case, normalized by the number of samples in the ground truth per class (rows).

It was observed in both systems that there were some common patterns in the misdetected samples with ground truth, ‘JA1A*’, ‘JA2’, ‘NEIN6’, and ‘NEIN1A’. Therefore, a more specific visual analysis was performed on these samples, drawing the following possible explanations:

- For the ‘JA1A*’ samples mispredicted as Nein (no), it was noticed that some of these samples had blurry hands, as is shown in the first row of Table 9, which could have an impact on the landmark detection, leading to mispredictions by the model.

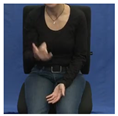

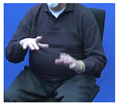

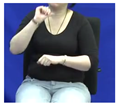

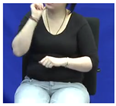

Table 9. Illustration of some of the mispredicted samples by both models. Each row represents some frames of the mispredicted videos for the ground truth class that is displayed in the first column. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form.

Table 9. Illustration of some of the mispredicted samples by both models. Each row represents some frames of the mispredicted videos for the ground truth class that is displayed in the first column. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form. - For the ‘JA2’ errors, the confusion could come from the position of the right hand being in a C-shape, which might be out of the training spectrum of the model for that class, as it may be normally signed with one hand, as in the fifth row of the reference Table A1 of signs samples showed in the Appendix B.

- For the ‘NEIN6’ samples misdetected as Ja (yes), the error could come from the reduced number of samples in the dataset for training compared with other classes, or alternatively from the specific sign, which in this case is more similar to the vertical hand movement performed more commonly for the ‘yes’ samples, compared with other ‘no’ versions in which mainly the hands follow an horizontal trajectory, leading to mispredictions in meanings during the translation from signs to text.

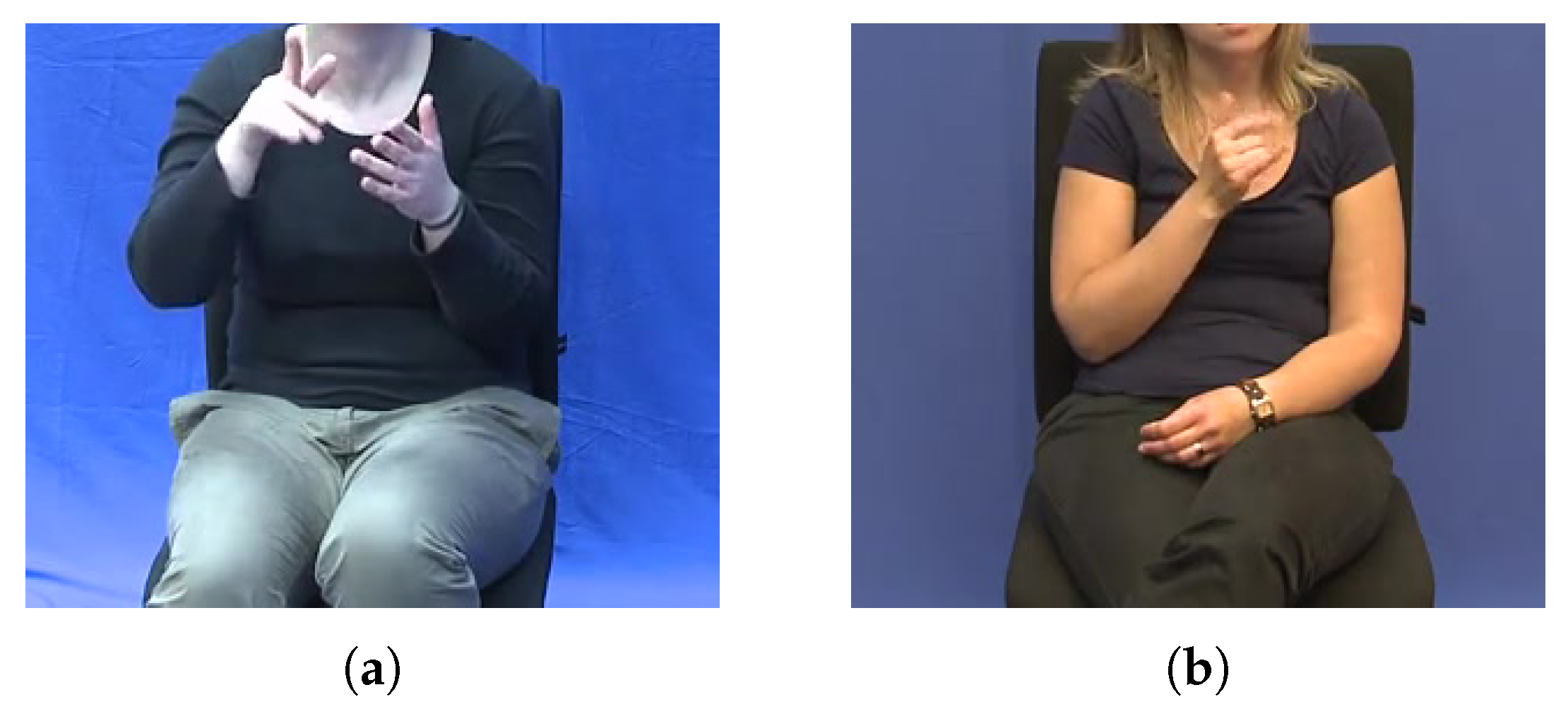

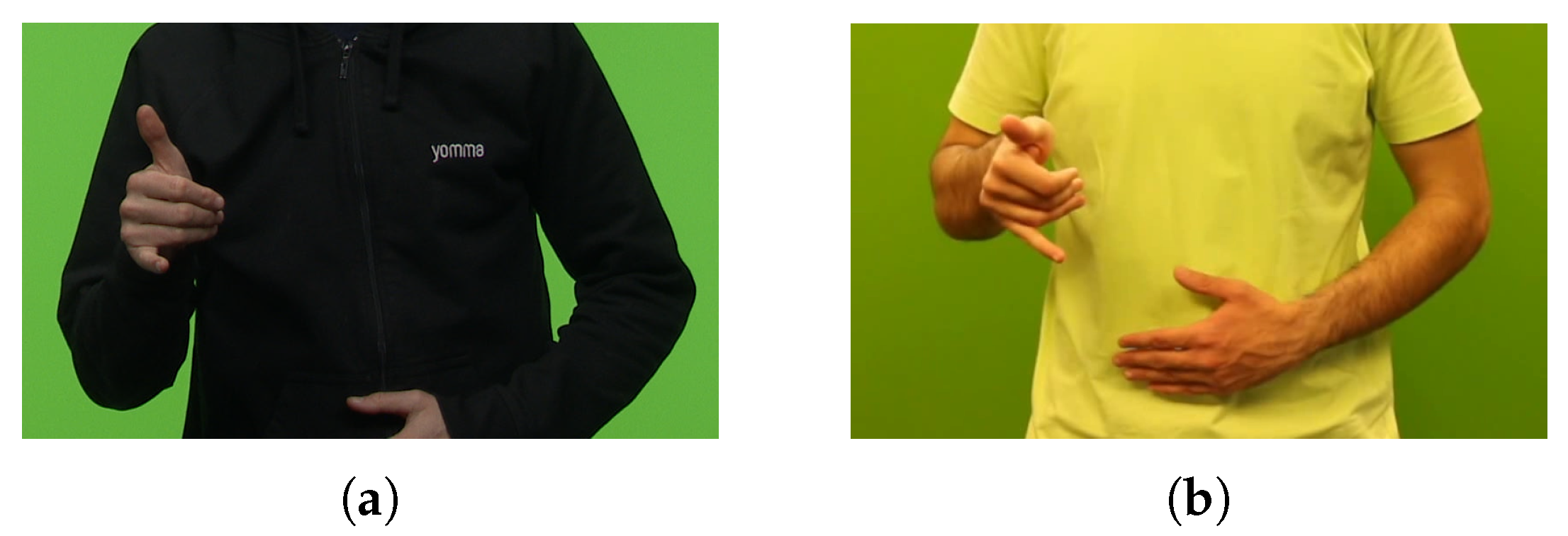

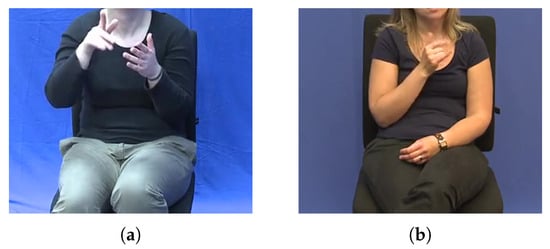

- Finally, for the common errors in ‘NEIN1A’, it was observed that the sample was confused with ‘JA1A*’ in the multi-class model. After observing the reference video of ‘JA1A*’ and ‘NEIN1A’ in Table A1, we noticed that some frames were similar during some transition movements between signs, as is displayed in Figure 8. These transitions may introduce noise, resulting in mispredictions at the end.

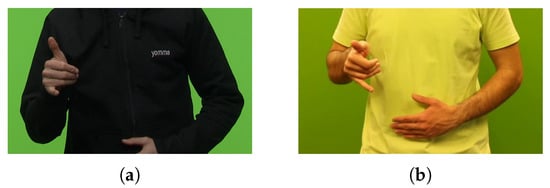

Figure 8. Comparison between a misclassified ‘NEIN1A’ vs. a correct frame of ‘JA1A*’. (a) Sample NEIN1A incorrectly classified as JA1A*. (b) Sample JA1A*.

Figure 8. Comparison between a misclassified ‘NEIN1A’ vs. a correct frame of ‘JA1A*’. (a) Sample NEIN1A incorrectly classified as JA1A*. (b) Sample JA1A*.

4.5. Generalization Study

In order to have a more realistic idea of how the models would generalize in tasks outside of the current scenario, we evaluated the model with one interpreter signing ‘yes’ and ‘no’ 14 times each to evaluate their generalization ability in these samples. To evaluate the models, we only asked them to sign and we did not provide any additional feedback about the specific glosses to make it more realistic. In this scenario, the models achieved an accuracy of 92.86% in this subset. Additionally, 16 non-proficient German Sign Language signers signed one sample of a ‘Ja’ and another of a ‘Nein’ following the signs of one of the videos of one of the interpreters; samples of these videos are displayed in Figure 9. Videos were recorded with different distances to the camera and resolutions (1920 × 1080 and 1280 × 720). From these experiments, the best model was able to achieve a 75% accuracy, with the Nein videos being predicted accurately in 15 of the 16 samples, whereas for the Ja videos, they were predicted correctly in 9 of the 16 samples.

Figure 9.

Samples employed to test the generalization ability of the models. (a) Sample of ‘Ja’ signed by an interpreter. (b) Sample of ‘Ja’ by a beginner signer in DGS.

These evaluations show that whenever the models are deviated from the specific scenario on which they were trained (the recording environment of the DGS-Korpus dataset), their performance could suffer some decrements, which is an expected behavior in these models given that they were trained on that specific dataset without data augmentation. Additionally, differences in the way of signing and proficiency may also introduce variations that the current models can not support. Nevertheless, these experiments indicate future lines to follow for improving their performance in real-world environments, such as incorporating data augmentation techniques, including zooming in and out to cope with variability in distances to the camera, or horizontal flipping to allow the model to cover left- and right-handed signers.

4.6. Subject-Wise Analysis

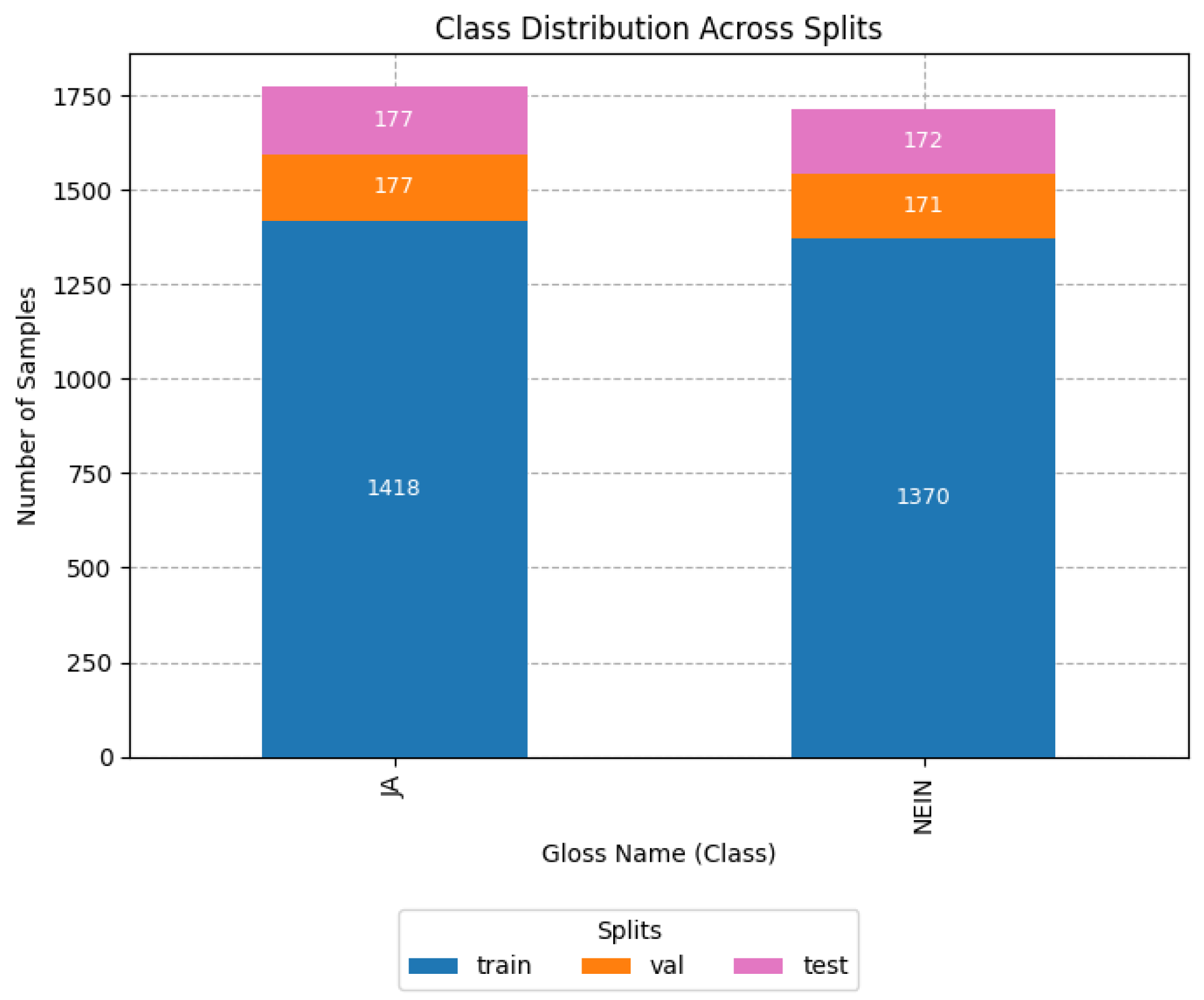

As the original split of the dataset was done in a non-subject-wise manner, we repeated the experiment of the best model by creating the splits in a subject-wise manner. For splitting the database by subject, we employed the annotation of the column referred to as ‘Paar’ (Pair), since this is the metadata provided to identify subjects (or pairs of individuals) in conversations in the DGS-Korpus. Additionally, to have representations of all the glosses in all the sets, we selected a split of 70/15/15 for training/validation/test sets. Figure 10 shows the distributions of samples for the binary task of yes or no classification of signs with the subject-wise distribution.

Figure 10.

Histogram of the class distribution of affirmation/negation with the subject-wise splits. ‘JA’ in German is translated to ‘Yes’ in English and ‘Nein’ is translated as ‘No’ in English.

We selected the transformer models without Positional Encoding with six attention heads, fed with coordinates (x,y) of the landmarks of the right and left hands (84 features in total) trained for 300 epochs with a learning rate of 0.0001 and an AdamW optimizer. In these conditions, the model achieved an accuracy of 95.32%, an M-F1 of 95.27%, and a W-F1 of 95.31% on the test set of the subject-wise dataset split and an accuracy of 96.93%, a W-F1 of 96.93%, and an M-F1 of 96.93% in the valence set.

4.7. Limitations

Despite the fact that the DGS-Korpus is one of the largest datasets for studying DGS across different regions, it is still limited in the repetitions of certain signs and in its vocabulary. For this reason, our exploration in this article focused on Ja/Nein. Other interesting answers to questions could be those related to uncertain situations, such as ‘I do not know’. However, after the exploration of this gloss using the ‘WISSEN-NICHT’ keyword, fewer than 120 samples were provided. Including this class would result in an imbalance in the dataset since ‘yes’ and ‘no’ classes contained almost 10 times more samples, which could result in a non-adapted model to the uncertainty class (‘WISSEN-NICHT’) while making the training more unstable. In this vein, we also observed that many of the samples were from signers whose dominant hand was the right hand; this can result in errors when the model is used with left-handed people, as well as in completely different conditions to those in which the dataset was recorded, which could be addressed in the future with data augmentation techniques applied to the landmarks. Additionally, due to limitations in the annotations of the DGS-Korpus dataset, some gestures such as nodding or changes in facial expressions that could potentially transmit the semantic meaning of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ could not be added to the detected glosses, given that it is not possible to filter them with the established rules if there is no annotations about the meaning and their temporal occurrences. Another limitation of the models is their testing in real-world applications. Current models are proposed with research purposes, i.e., if they are meant to be employed in the wild or real-world applications. Robust experiments should be performed depending on the use case and the critical task to be solved. Some of these experiments could include variability in the signing, lighting conditions, etc. Additionally, another critical task is how to manage temporal continuous detection, given that it is possible that models report an over-confident response even when the sign is not happening. In this study, we acknowledge the limitations of our models, which could work under similar conditions of the testing environment and the recording scenario of the DGS-Korpus. Outside of these conditions, the performance is expected to decrease, as we initially showed in the generalization study; hence, more data should be collected for other environments. Other limitations are derived from the use of landmarks. Although they have many positive features, like the feasibility of anonymization, there are some drawbacks, such as the cascade downstream propagation of the errors occurring due to misdetection and transformer recognition.

5. Conclusions

Sign Language constitutes the main mode of communication within deaf communities worldwide. Nevertheless, its inherent variability, which encompasses numerous languages and dialects, presents significant challenges for the construction of general-purpose datasets and recognition models. Consequently, this work concentrates on the development of domain-specific models for Isolated Sign Language Recognition in DGS, with a particular emphasis on recognizing signs for answering polar questions, which could be employed in daily activities for recognizing answers to any yes/no questions.

With this aim, we explored the different variations existing in one of the largest datasets in DGS, the DGS-Korpus dataset. In total, we selected 20 different gloss classes based on the amount of available samples: 7 classes or variations for affirmative responses (‘yes’ in English, ‘Ja’ in German) and 13 variations for negative responses (‘no’ in English, ‘Nein’ in German). With these variations, we created a sub-dataset from the DGS-Korpus and explored transformer models for implementing lightweight recognizers of these polar signs on two sub-tasks: the binary approach for differentiating in semantic signs (i.e., those signs meaning yes versus no) and the multi-class approach for recognizing each of the 20 glosses.

To optimize the models for the binary scenario, we evaluated different training strategies by modifying the optimizer, batch sizes, and learning rate and clipping the weights to avoid overfitting. Additionally, we also explored the contribution of employing different body landmarks (i.e., hands or hands plus pose) and the employed coordinates. The results showed that there was no statistically significant differences between using hand landmarks versus hand landmarks plus pose in terms of accuracy, W-F1, and M-F1 for the positive/negative answer dataset that we explored. For this reason, and to simplify the complexity of the models and the input size, employing only the x, y coordinates of the hand landmarks could be more suitable for models expected to work on light or real-time scenarios.

Due to the recent literature about the contribution of additive Positional Encoding in transformers under scarce-resource scenarios, we performed ablation studies of the top models with and without PE, achieving a statistically significant increment from 14.61 to 20.35 depending on the model when the additive sin–cos PE was removed from the transformer. Finally, we performed a final study in the multi-class scenario for recognizing glosses with the aim of exploring whether working at the semantic level (binary classification problem) could be accompanied by some advantages versus working at the gloss recognition level (with 20 classes). After comparing the confusion matrices in the binary scenario, both models reported similar performances in accuracy, W-F1, and M-F1, but in the multi-class scenario, the error analysis is more insightful to evaluate similarities and differences between glosses in terms of the number of samples, the dominant hands, hand trajectories, and the positions of hands and fingers, which is more convenient for studying the limitations of the models and proposing further improvements.

As future lines of study, it would be valuable to evaluate other classes available in the DGS-Korpus to cover answers to a broader set of questions, such as number recognition. Regarding the models, allowing the support of multi-channel inputs could improve the robustness of the models by relying on non-manual cues (e.g., mouthing) when the hands are not correctly detected or blurry. Finally, including data augmentation techniques and different tests to evaluate how the model performs with signers with different dominant hands, regions, or DGS proficiency would help to analyze the limitations of the models and their requirements for successful practical integration in real-world applications. As a last note, collaborations with linguists to perform in-depth error analysis and in-the-wild testing of the models are also future next steps to discover more limitations and to work on their improvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.-J.; methodology, C.L.-J.; software, C.L.-J.; validation, C.L.-J. and L.E.; formal analysis, C.L.-J.; investigation, C.L.-J., L.E. and E.A.; resources, C.L.-J., L.E. and E.A.; data curation, C.L.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.-J., L.E., S.E.-R. and M.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, C.L.-J., L.E., S.E.-R., M.G.-M. and E.A.; visualization, C.L.-J.; supervision, E.A.; project administration, C.L.-J. and E.A.; funding acquisition, E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) through the BIGEKO project, grant number 16SV9094. Sergio Esteban-Romero’s research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Education (FPI grant PRE2022-105516). This work was partially funded by Project ASTOUND (101071191—HORIZON-EIC-2021-PATHFINDERCHALLENGES-01) of the European Commission and by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the projects GOMINOLA (PID2020-118112RB-C22) funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union “NextGenerationEU/PRTR”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The distribution of the splits of the DGS-Korpus dataset will be provided upon request. However, for access to the videos of the DGS-Korpus, a previous license has to be agreed with the University of Hamburg https://www.sign-lang.uni-hamburg.de/meinedgs/ling/license_en.html (Last Access: 19 August 2025). For the generalization study, only landmarks and sign annotations can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DGS | Deutsche Gebärdensprache (German Sign Language) |

| ISLR | Isolated Sign Language Recognition |

| CSLT | Continous Sign Language Translation |

| PE | Positional Encoding |

| W-F1 | Weighted-F1 |

| M-F1 | Macro-F1 |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| RH | Right Hand |

| LH | Left Hand |

| P | Pose |

| GCNs | Graph Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

Appendix A

Figure A1 shows the confusion matrix for the best performing models for the multi-class recognition task. Rows represent the number of samples per class in the test set, while columns refer to the predictions of the model.

Figure A1.

Confusion matrix for the multi-class (gloss recognition) results for GAP without PE, introducing the landmarks of the xy coordinates of the hands. Colors indicate the number of samples correctly or incorrectly detected. The darker the blue, the higher the proportion. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol. ‘JA’ in German is translated to ‘Yes’ in English and ‘Nein’ is translated as ‘No’ in English.

Figure A1.

Confusion matrix for the multi-class (gloss recognition) results for GAP without PE, introducing the landmarks of the xy coordinates of the hands. Colors indicate the number of samples correctly or incorrectly detected. The darker the blue, the higher the proportion. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol. ‘JA’ in German is translated to ‘Yes’ in English and ‘Nein’ is translated as ‘No’ in English.

Appendix B. Sample Images per Gloss for the Multi-Class Case

Table A1 shows samples with the signs of each of the classes. Four frames were selected per sample, one at the beginning, two in the middle, and one at the end. To see video samples directly from the DGS-Korpus, visit the ANNIS Tool (https://dock.fdm.uni-hamburg.de/meinedgs/#_q=R2xvc3M9IkpBMUEqIiAg&ql=aql&_c=REdTLUNvcnB1cy1yMy1kZQ&cl=5&cr=5&s=0&l=10, accessed on 20 September 2025).

Table A1.

List of glosses with 4 frames extracted from a sample of the DGS-Korpus. To retain anonymity, and given our top model worked with only hands, images from videos were cropped to not display the faces of the signers. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol.

Table A1.

List of glosses with 4 frames extracted from a sample of the DGS-Korpus. To retain anonymity, and given our top model worked with only hands, images from videos were cropped to not display the faces of the signers. According to the DGS-Korpus annotations standards [16], tokens with ‘*’ are those that differ from the type/subtype citation form; similarly, tokens followed by a ‘^’ indicate type glosses in contrast to subtype glosses that do not have the symbol.

| Gloss Name | Starting | Middle 1 | Middle 2 | End |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JA1A |  |  |  |  |

| JA1A* |  |  |  |  |

| JA1A^ |  |  |  |  |

| JA1A^* |  |  |  |  |

| JA2 |  |  |  |  |

| JA2* |  |  |  |  |

| JA3A* |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN1A |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN1A* |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN1B |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN1B* |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN1B^ |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN2A |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN2A* |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN2B |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN2B* |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN3B^ |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN3B^* |  |  |  |  |

| NEIN6 |  |  |  |  |

Appendix C. Results on the Validation Set

Table A2 reports the performance of the models reported in Table 2 for the validation set. From the table, we can observe that both in the validation and test sets exist a common tendency in which the top models are trained employing batches of 128 samples, with the AdamW optimizer, and a learning rate of 0.0001. Notice that in this work, and following previous approaches [36], the results reported in the tables are the result of the selection of the best checkpoint in the test set from those that achieved improvements in accuracy in the validation set.

Table A2.

Results for affirmation/negation answers for the validation set. ‘✓’ indicates clipping weights, whereas ‘✗’ indicates not clipping weights.

Table A2.

Results for affirmation/negation answers for the validation set. ‘✓’ indicates clipping weights, whereas ‘✗’ indicates not clipping weights.

| Batch Size | Optimizer | lr | clipWeights | ACC | W-F1 | M-F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | SGD | 0.01 | ✓ | 69.83 | 69.80 | 69.82 |

| 128 | 61.21 | 60.92 | 60.97 | |||

| 224 | 58.62 | 58.33 | 58.27 | |||

| 32 | SGD | 0.01 | ✗ | 71.26 | 71.14 | 71.10 |

| 128 | 63.22 | 62.96 | 63.01 | |||

| 224 | 57.18 | 57.14 | 57.1 | |||

| 32 | SGD | 0.001 | ✓ | 60.06 | 59.72 | 59.78 |

| 128 | 55.75 | 55.19 | 55.27 | |||

| 224 | 55.17 | 54.82 | 54.88 | |||

| 32 | SGD | 0.001 | ✗ | 62.36 | 61.5 | 61.59 |

| 128 | 58.62 | 58.62 | 58.62 | |||

| 224 | 57.76 | 57.73 | 57.7 | |||

| 32 | SGD | 0.0001 | ✓ | 58.62 | 58.61 | 58.62 |

| 128 | 54.60 | 51.59 | 51.79 | |||

| 224 | 56.32 | 55.88 | 55.79 | |||

| 32 | SGD | 0.0001 | ✗ | 58.91 | 56.49 | 56.3 |

| 128 | 54.31 | 49.42 | 49.14 | |||

| 224 | 55.46 | 55.46 | 55.44 | |||

| 32 | AdamW | 0.01 | ✓ | 50.86 | 34.3 | 33.71 |

| 128 | 50.86 | 34.3 | 33.71 | |||