Augmented Reality in English Language Acquisition Among Gifted Learners: A Systematic Scoping Review (2020–2025)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Process

- Gifted students + ESL

- 2.

- ESL + AR

- 3.

- Gifted students + AR

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

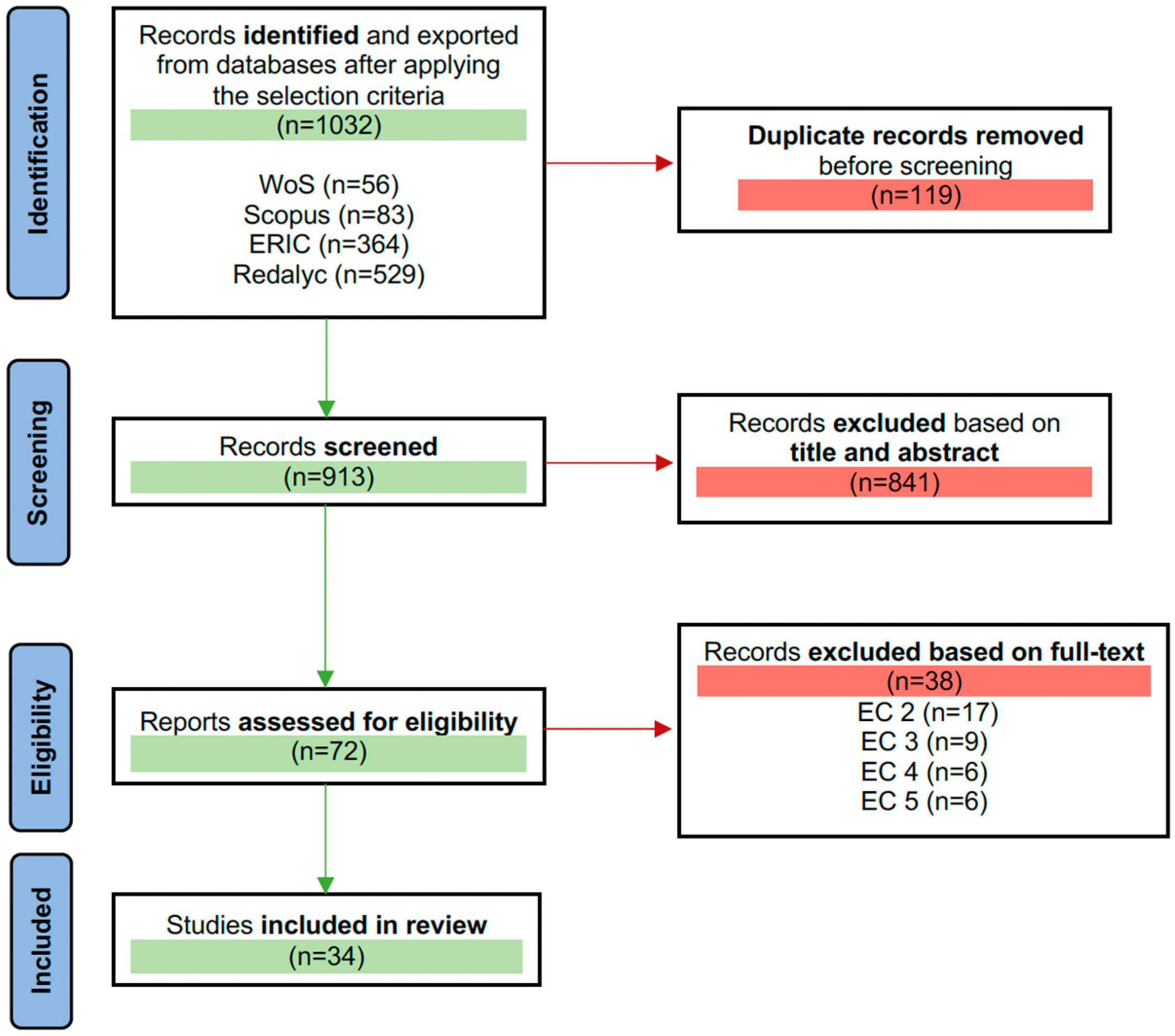

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. General Description of the Results

3.2. Narrative Synthesis

3.2.1. Factors Shaping L2 Learning in Gifted Students

3.2.2. Development of L2 Linguistic Skills in Gifted Students

Speaking Skills

Writing Skills

3.2.3. Development of L2 Linguistic Skills Through AR

Speaking Skills

Listening Skills

Reading and Writing Skills

Vocabulary

Intercultural Competence

3.2.4. Other Variables and the Use of AR

Cognitive Development and Academic Performance

Motivation and Engagement

Learning Language Anxiety

Teacher Professional Development

3.2.5. Limitations and Barriers to the Use of AR

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| ESL | English as a second language |

| EFL | English as a foreign language |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| ERIC | Education Resources Information Center |

Appendix A

| Authors and Date | Methodology | Context | Population | Intervention | Topic | Focus on | Linguistic Outcomes | Motivational and Other Outcomes | Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wen et al. (2022) [25] | Review | Iran | Documents | No, analysis | Giftedness + ESL | Exceptional language aptitudes. | Becoming a polyglot results from a combination of cognitive, affective, and contextual factors rather than innate talent. | - | - |

| Faridi & Izadpanah (2024) [26] | Quantitative | Iran | n = 360 Iranian EFL students at intermediate and advanced levels (ages 13–16) | No | Giftedness + ESL | Perceptions and attitudes toward learning approaches | - | Positive attitudes toward self-regulation and constructivism (critical thinking, problem-solving, active participation). Autonomy, motivation, and active engagement. | -. |

| Rajić et al. (2022) [27] | Review | - | n = 175 studies, 3 of them selected | No, analysis | Giftedness + ESL | Success in L2 acquisition according to variables such as personality traits, metacognition, self-confidence. | - | Intrinsic motivation and certain personality traits (Intellect, Agreeableness) are strong predictors of success, while amotivation hinders it. Motivational autonomy is key to self-regulation and to performance of gifted students. | - |

| Alimorad & Akbarzadeh (2022) [28] | Qualitative | Iran | n = 8 advanced EFL students aged 19–21 | No | Giftedness + ESL | Willingness to communicate (WTC) in English in digital contexts. | L2 WTC fluctuates depending on affective, contextual and linguistic factors. | Students are motivated to use English in digital environments by personal interest, confidence, cultural connection, and agency. | Interaction with native speakers can either enhance or hinder their WTC. |

| Do & Nguyen (2021) [29] | Mixed | Vietnam | n = 180 English-majored students aged 18–20 | No, diagnosis | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Needs: speaking and listening | The students prioritise oral communication (speaking and listening). | Strong motivation related to career opportunities and communication. | Dissatisfaction with the instruction received (exam preparation- grammar and reading). |

| Manasrah et al. (2023) [30] | Quantitative | Saudi Arabia | n = 118 gifted EFL learners aged 25–19 | No, diagnosis | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Needs | English as essential for their future, preferring activities that mirror real-life situations and virtual environments. Need for a tailored, engaging curriculum that incorporates technology and experiential learning. | - | |

| Rayati et al. (2023) [31] | Mixed | - | n = 23 low and 25 high proficiency EFL learners | No, diagnosis | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Speaking | Learners with higher English proficiency tend to employ more advanced strategies (metacognitive and cognitive). | - | - |

| Ostovar-Namaghi et al. (2022) [32] | Qualitative | Iran | n = 17 advanced EFL learners | No, diagnosis | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Speaking | Use of explicit and reciprocal communication strategies to maintain interaction. Importance of strategic awareness training in improving oral competence. | - | - |

| Kasap (2021) [33] | Mixed | Turkey | n = 146 gifted students aged 12–17 | No, diagnosis | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Speaking anxiety | Students in arts and music programmes exhibit significantly lower anxiety levels compared to those in science programmes. | Error perception and fear of failure contribute to increased anxiety levels. | |

| Wang et al. (2023) [34] | Quantitative | China | n = 518 advanced EFL university students aged 18–23 | No | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Writing | Greater use of self-regulated strategies is positively associated with better performance in L2 writing. | Those who manage their motivation more effectively write more successfully in English. Advanced students display more stable and flexible motivational patterns. | - |

| Du et al. (2022) [35] | Quantitative | - | n = 174.743 English learners, K–12 | 128 different writing activities. | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Writing: Collocational competence. | Positive link between proficiency level and collocation difficulty/length. Over half of their combinations were native-like collocations. | Learners attempt to mimic native-like usage even at early stages, suggesting awareness and motivation to achieve natural expression in writing. | - |

| Zinkgraf & Verdú (2021) [36] | Quantitative | Spanish speaking countries | n = 37 advanced English learners, university students aged 20–34 | Dictogloss as a teaching strategy for formulaic sequences | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Writing: Productive use of formulaic sequences | Growing awareness, accuracy, and variety in FS use. | - | - |

| Azimova & Solidjonov (2023) [37] | Review + Quantitative | Uzbekistan | n = 30 university students aged 18–30 | Development of an AR app using Unity + Vuforia | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, reading, and writing in English. | AR is especially effective in vocabulary and pronunciation, thanks to immersive practice and instant feedback. | Real-world context, quick feedback, and immersive language learning experiences. | Weaker support for grammar and writing skills; dependence on stable internet access. |

| He & Oltra-Massuet (2023) [38] | Quantitative | International: China and Spain | n = 81 (12 native, 32 Chinese EFL learners, 37 Spanish EFL learners) aged 20–40, at least C1 level | No, experiment (Word Monitoring Task (WMT)) | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Implicit knowledge of grammar: questions (yes/no and wh-questions) | It is difficult for L2/FL learners to acquire a native-like knowledge of morphosyntactic features. | Learners’ motivation is associated with their academic background and their advanced level of English. | - |

| Murtisari (2021) [39] | Qualitative | Indonesia | n = 29 advanced EFL students enrolled in English Language Education and English Literature programmes | No | Giftedness + ESL | L2 Academic writing. Translation strategies. | Students frequently relied on mental (L1 to L2) (100%) and partial written translation (79%) as scaffolding to express complex ideas, finding it helpful for fluidity and vocabulary. | Motivation is linked both to the need for support and to individual learning preferences. | Often detrimental to naturalness, which led to ambivalent feelings about its use. |

| Lin & Tsai (2021) [40] | Mixed | Taiwan | n = 50 English-major junior students, B1-B2 | Use of two AR-based English courses, 4 weeks | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Listening/speaking, with integrated text-to-speech, speech recognition, and instant feedback. | Improvements in vocabulary, pronunciation, speaking and listening. | Strong motivation and positive attitudes toward AR in EFL learning. Instant evaluation and feedback supported error recognition and correction, enhancing oral practice and confidence. | - |

| Khodabandeh (2023) [41] | Quantitative | Iran | n = 60 EFL beginners, aged 13–16 | Use of a custom ARG app with 12 tasks about giving/asking for directions | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Speaking and writing, grammar (asking for and giving instructions) | Strong gains in interaction, visualization, and comprehension. | Motivation, engagement, collaborative learning, feedback, contextualised learning, critical thinking, authentic communicative practice, autonomy and active participation. | - |

| Raj & Tomy (2023) [42] | Quantitative | India | n = 121 first-year B. Tech students | Use of mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) with 46 shortlisted listening apps | ESL + AR | L2 Listening skills with indirect support for pronunciation and speaking. | The experimental group improved significantly (phonetics, morphemes, syntax, comprehension). Apps provided flexibility, autonomy, and improved oral comprehension. | Mobile apps increased curiosity, learner autonomy, and engagement. Students reported reduced anxiety and more willingness to practice. | - |

| Binhomran & Altalhab (2021) [43] | Quantitative | China | n = 120 English-major undergraduates | Development of an AR-based translation teaching platform. | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | Translation skills, reading comprehension, and grammar analysis, with vocabulary and expression development integrated. | They outperformed their peers in translation and reading comprehension. | Higher levels of engagement, interaction, and satisfaction reported in the AR group. | No significant difference in grammar analysis, suggesting AR supports applied/visual tasks more than abstract grammar reasoning. |

| Yangin Ersanli (2023) [44] | Mixed | Turkey | n = 56 fifth graders (A2 CEFR) | Use of storytelling with AR materials (Unity + QR codes, 3D interactive animations). | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Vocabulary learning and retention, with support from listening, reading, and speaking through storytelling. | The AR group showed significantly higher retention. | AR storytelling increased intrinsic motivation, concentration, and willingness to learn. | - |

| Tsai (2020) [45] | Mixed | Taiwan | n = 42 fifth graders (ages 11–12) | QuiverVision AR app, 4 weeks | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Vocabulary learning and retention + motivation | They outperformed their peers in vocabulary. | Motivation survey scores (attention, confidence, satisfaction, relevance) were significantly higher. AR is exciting and effective. | - |

| Lai & Chang (2021) [46] | Quantitative | Taiwan | n = 47 first graders | Use of Aurasma AR app on tablets. | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 vocabulary acquisition and performance | AR students improved in vocabulary performance. | AR apps were highly effective at boosting attention, relevance, and satisfaction. Students found AR novel, immersive, and engaging, which reduced anxiety and made vocabulary learning more enjoyable. | - |

| Larchen Costuchen et al. (2022) [47] | Qualitative | Spain and Sweden | n = 12 Spanish native/bilingual speakers (ages 26–48) | Use of MnemoRoom4U | ESL + AR | L2 vocabulary recall (orthographic recognition and translation tasks). | High recall scores, slightly above or equal to controls. | AR app was rated very motivating and easy to use. | - |

| Tyson (2021) [48] | Quantitative | USA | n = 29 students aged 14–18 | Use of AR via Nearpod virtual field trips | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Academic vocabulary acquisition and retention (definition recall and contextual sentence use) | Students recalled vocabulary more confidently, often linking words to specific AR visual contexts. | AR increased engagement, attention, and enjoyment. | - |

| Larchen Costuchen et al. (2021) [49] | Quantitative | Spain | n = 62 undergraduate teacher-training students (mean age ≈ 19), English level B1–B2 | Study 10 unknown English idioms for 15 min with AR | ESL + AR | L2 vocabulary recall (idiomatic expressions) | They outperformed their peers in both immediate and delayed one-week tests. | AR method was more engaging and entertaining than flashcards, likely enhancing learner motivation and willingness to engage with the vocabulary task. | Forgetting was steeper in AR-VSB over time. |

| Mamani-Calapuja et al. (2023) [50] | Quantitative | Peru | n = 42 kindergarten children (ages 3–5) | Use of Wordtastic Kids App (age-leveled) | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 vocabulary acquisition, with support for listening, pronunciation, reading recognition. | Effectiveness of AR for vocabulary learning and retention in early childhood. Significant improvements in all categories (animals, clothes). | Children were highly engaged, curious, and motivated by the novelty, interactivity, and fun of AR. Teachers observed improved attention, enjoyment, and participation. | Successful implementation depends on teacher preparation, AR content quality, etc. |

| Liu et al. (2023) [51] | Mixed | China | n = 48 undergraduate students (average age ≈ 19), intermediate English level. | AR Language Learning App with immersive cultural content | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | Intercultural competence and motivation | Significant improvements in intercultural competence and motivation. Increased engagement, deeper cultural understanding, and enhanced ability to apply language in authentic scenarios. | AR is immersive, fun, and curiosity-driven. Interactive cultural tasks, immediate feedback, and real-world connections fostered greater enthusiasm, self-regulation, and willingness to learn English. | - |

| Voreopoulou et al. (2024) [53] | Qualitative | Greece | A2 CEFR level schoolchildren | ARTutor4 platform: LockED in Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (Escape room) | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Vocabulary, development of linguistic skills, cultural awareness + motivation, creativity, critical thinking | Improved language practice and cultural knowledge beyond traditional curricula. | The AR escape classroom game was fun, interactive, and engaging, which reduced anxiety and fostered teamwork while enhancing willingness to use English. Deep and meaningful learning through problem-solving and collaboration. | - |

| Wang et al. (2021) [54] | Qualitative | China | n = 38 students (18–20 years old), low English scores | Use of XploreRAFE+, 4 weeks | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | Addressing low motivation and burnout in English learning | Improvement observed in fluency, vocabulary use, writing practice, and collaborative communication. | Interest was formed through a cyclical process: curiosity → immersion/flow → meaningfulness. | - |

| Zain (2023) [55] | Review | - | n = 22 empirical studies | No, analysis | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | L2 Writing, reading, vocabulary, pronunciation and speaking + motivation, personalisation | Improved performance and achievement in vocabulary, reading, writing, and pronunciation. | Increased learning satisfaction and reduced anxiety. Situated, personalised, and collaborative learning fostered deeper engagement. | Technical issues. Unequal technological competence among students. Health/social concerns. |

| Briceño (2021) [56] | Quantitative | Ecuador | n = 120 students aged 6–8 | Teaching English through kinesthetic activities (games, dramatisation, dances, etc.). | Giftedness + ESL | Relationship between linguistic intelligence and English proficiency | Significant improvements in speaking, listening, reading, and writing (notable gains in confidence and writing fluency). | It creates a trusting environment, reduces academic pressure, and motivates learners, making the learning process more meaningful and effective. | - |

| Zhao & Wang (2024) [57] | Mixed | Saudi Arabia | n = 73 sixth-grade Saudi female students (ages 11–12) | Use of Storybooks Alive AR app | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | Translation, vocabulary + motivation | AR group scoring slightly higher. | AR group students reported better understanding, engagement, and confidence. | No teacher support, and minor issues (distraction, technical skills, sharing devices) were noted. |

| Karacan & Akoglu (2021) [58] | Review | Turkey | Documents | No, analysis | ESL + AR, AR + Motivation | AR’s potential | It improves overall performance, with strong evidence for vocabulary gains and retention. | AR as engaging, enjoyable, and less anxiety-inducing compared to traditional approaches, boosting their willingness to participate. | Challenges remain in infrastructure, teacher training, and sustainable integration. |

| Garcia-Ponce & Tavakoli (2022) [59] | Quantitative | Mexico | n = 30 university students aged 18–26 | 3 dialogic tasks: personal information task, narrative task, and decision-making task. | Giftedness + ESL | How different types of dialogic tasks and proficiency level affect oral performance (CALF) and task engagement. | Personal tasks boosted fluency and accuracy, narratives promoted complexity, and decision-making tasks enhanced lexical variety and social engagement. | More interactive and negotiated tasks are more motivating and productive for L2 learning. Greater task engagement correlated with better performance. Task familiarity (personal information) reduces anxiety. | Task familiarity also limits challenge and cognitive motivation. |

References

- Kuznetsova, E.; Liashenko, A.; Zhozhikashvili, N.; Arsalidou, M. Giftendess identification and cognitive, physiological and psychological characteristics of gifted children: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1411981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourón, J. Entendiendo el Modelo de los Tres Anillos. Javier Tourón. Available online: https://www.javiertouron.es/entendiendo-el-modelo-de-los-tres-anillos/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Dunn, R.; Price, G. The Learning Style Characteristics of Gifted Students. Gift. Child Q. 1980, 24, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Aqui, Y. Cognitive and Motivational Characteristics of Adolescents Gifted in Mathematics: Comparisons Among Students with Different Types of Giftedness. Gift. Child Q. 2004, 48, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, J.; Buecker, S.; Schneider, M.; Preckel, F. Intellectual Giftedness and Multidimensional Perfectionism: A Meta-Analytic Review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergold, S.; Wirthwein, L.; Steinmayr, R. Similarities and Differences Between Intellectually Gifted and Average-Ability Students in School Performance, Motivation, and Subjective Well-Being. Gift. Child Q. 2020, 64, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénony, H.; Van Der Elst, D.; Chahraoui, K.; Bénony, C.; Marnier, J.P. Lien entre dépression et estime de soi scolaire chez les enfants intellectuellement précoces [Link between depression and academic self-esteem in gifted children]. L’Encephale 2007, 33, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuchter, M.D.; Preckel, F. Reducing boredom in gifted education—Evaluating the effects of full-time ability grouping. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 1477–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, M.; Jung, J.Y.; Evans, P. Motivational profiles of gifted students in science. Educ. Psychol. 2025, 45, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K.E.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. A developmental, person-centered approach to exploring multiple motivational pathways in gifted underachievement. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 48, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. Reframing Social and Emotional Development of the Gifted. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedlove, L. Characteristics of Gifted Learners. In Introduction to Gifted Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.M.; Sulaiman, N.A.; Embi, M.A. Malaysian gifted students’ use of English language learning strategies. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2013, 6, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, C.; Kanar, M. How can you “Gift” to Second Language Young Learners. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 136, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van Tassel-Baska, J.; MacFarlane, B.; Baska, A. The Need for Second Language Learning. In Parenting for High Potential; National Association for Gifted Children: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 6, pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Puskás, A. Gifted and Talented Learners in the Foreign Language Classroom; Tribun EU s.r.o.: Brno, Czech Republic, 2021; ISBN 978-80-263-1665-7. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, M.M.S. New Trends in Gifted Education; Faculty of Education, Assiut University: Asyut, Egypt, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khasawneh, F.M.; Al-Omari, M.A. Motivations towards learning English: The case of Jordanian gifted students. Int. J. Educ. 2015, 7, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.; Rapp, K.E.; Martínez, R.S.; Plucker, J.A. Identifying English language learners for gifted and talented programs: Current practices and recommendations for improvement. Roeper Rev. 2007, 29, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronborg, L.; Plunkett, M. Providing an optimal school context for talent development: An extended curriculum program in practice. Australas. J. Gift. Educ. 2015, 24, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riwayatiningsih, R.; Prastikawati, E.F.; Muchson, M.; Haqiqi, F.N.; Setyowati, S.; Kartiko, D.A. Empowering Higher-Order Thinking Skills in Writing through Gamification and Multimodal Learning within PBL. Forum Linguist. Stud. 2025, 7, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrahi-Gomez, V.; Belda-Medina, J. Assessing the effect of Augmented Reality on English language learning and student motivation in secondary education. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1359692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, F. An Example Praxis for Teaching German as a Second Foreign Language with Augmented Reality Technology at Secondary Education Level. Int. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2023, 10, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Yang, J.; Han, L. Do polyglots have exceptional language aptitudes? Lang. Teach. Res. Q. 2022, 31, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridi, M.; Izadpanah, S. The Study of EFL Learners’ Perception of Using E-learning, Self-Regulation and Constructivism in English Classrooms: Teachers, Intermediate and Advanced Learners′ Attitude. J. Lang. Educ. 2024, 10, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajić, A.G.; Šafranj, J.; Prtljaga, J. Predictive values of the structure of the self-regulatory construct in L2 learning of the gifted. Res. Pedagog. 2022, 12, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimorad, Z.; Akbarzadeh, S. Unraveling Advanced EFL Learners’ L2 Willingness to Communicate in Extramural Digital Settings. J. Pan-Pac. Assoc. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 26, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Nguyen, T.T.A. Gifted High School Students’ Needs for English Learning in Vietnam Contexts. Arab World Engl. J. 2021, 12, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasrah, M.; Alzobiani, I.; Alharthi, N.; Alelyani, N. Exploring Gifted Secondary School Students’ Needs for English Learning in Saudi Arabia. Arab World Engl. J. 2023, 14, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayati, M.; Abedi, H.; Aghazadeh, S. EFL learners’ speaking strategies: A study of low and high proficiency learners. Mextesol J. 2023, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostovar-Namaghi, S.A.; Mohit, F.; Morady Moghaddam, M. Exploring advanced EFL learners’ awareness of communication strategies. Aust. J. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 5, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasap, S. Foreign language anxiety of gifted students in Turkey. Pegem J. Educ. Instr. 2021, 11, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Shen, X. Validation of self-regulated writing strategies for advanced EFL learners in China: A structural equation modeling analysis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Afzaal, M.; Al Fadda, H. Collocation Use in EFL Learners’ Writing Across Multiple Language Proficiencies: A Corpus-Driven Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 752134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkgraf, M.; Verdú, M.A. Dictogloss steals the show? Productive use of formulaic sequences by advanced learners. Lexis 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimova, D.; Solidjonov, D. Learning English language as a second language with augmented reality. Qo’Qon Univ. Xabarnomasi 2023, 1, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Oltra-Massuet, I. Implicit Knowledge Acquisition and Potential Challenges for Advanced Chinese and Spanish EFL Learners: A Word Monitoring Test on English Questions. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtisari, E.T. Use of translation strategies in writing: Advanced EFL students. J. Lang. Lang. Teach. 2021, 24, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Tsai, S.-C. Student perceptions towards the usage of AR-supported STEMUP application in mobile courses development and its implementation into English learning. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 37, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabandeh, F. Exploring the viability of augmented reality game- enhanced education in WhatsApp flipped and blended classes versus face-to-face classes. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 617–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Tomy, P. Mobile technology as a dependable alternative to language labs and to improve listening skills. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2023, 12, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binhomran, K.; Altalhab, S. The impact of implementing augmented reality to enhance the vocabulary of young EFL learners. JALT CALL J. 2021, 17, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangın Ersanli, C. The effect of using augmented reality with storytelling on young learners’ vocabulary learning and retention. Novitas-ROYAL. (Res. Youth Lang.) 2023, 17, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-C. The Effects of Augmented Reality to Motivation and Performance in EFL Vocabulary Learning. Int. J. Instr. 2020, 13, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.-Y.; Chang, L.-T. Impacts of Augmented Reality Apps on First Graders’ Motivation and Performance in English Vocabulary Learning. Sage Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larchen Costuchen, A.; Font Fernández, J.M.; Stavroukalis, M. AR-supported mind palace for L2 vocabulary recall. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. IJET 2022, 17, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, M. Impact of augmented reality on vocabulary acquisition and retention. Issues Trends Learn. Technol. 2021, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larchen Costuchen, A.; Darling, S.; Uytman, C. Augmented reality and visuospatial bootstrapping for second-language vocabulary recall. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2021, 15, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani-Calapuja, A.; Laura-Revilla, V.; Hurtado-Mazeyra, A.; Llorente-Cejudo, C. Learning English in Early Childhood Education with Augmented Reality: Design, Production, and Evaluation of the “Wordtastic Kids” App. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, S.; Ji, X. Beyond borders: Exploring the impact of augmented reality on intercultural competence and L2 learning motivation in EFL learners. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1234905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haoming, L.; Wei, W. A systematic review on vocabulary learning in AR and VR gamification context. Comput. Educ. X Real. 2024, 4, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voreopoulou, A.; Mystakidis, S.; Tsinakos, A. Augmented Reality Escape Classroom Game for Deep and Meaningful English Language Learning. Computers 2024, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Md Khambari, M.N.; Wong, S.L.; Razali, A.B. Exploring Interest Formation in English Learning through XploreRAFE+: A Gamified AR Mobile App. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, D. The implementation of Augmented Reality for language teaching and learning: A research synthesis. Mextesol J. 2023, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño Núñez, C.E. Interacción de las inteligencias lingüística y kinestésica y su impacto sobre la adquisición de idiomas. Rev. Franz Tamayo 2021, 3, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q. Applying augmented reality multimedia technology to construct a platform for translation and teaching system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karacan, C.G.; Akoğlu, K. Educational Augmented Reality technology for language learning and teaching: A comprehensive review. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2021, 9, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ponce, E.E.; Tavakoli, P. Effects of task type and language proficiency on dialogic performance and task engagement. System 2022, 105, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, S.; Chen, H.-J. A Comparative Study of the Effect of CALL on Gifted and Non-Gifted Adolescents’ English Proficiency. In Proceedings of the 2015 EUROCALL Conference, Padova, Italy, 26–29 August 2015; Helm, F., Bradley, L., Guarda, M., Thouësny, S., Eds.; Research-publishing.net: Dublin, Ireland, 2015; pp. 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, J.H.; Ahn, J.J.; Lee, H. The role of motivation and vocabulary learning strategies in L2 vocabulary knowledge: A structural equation modeling analysis. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2022, 12, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S.A.; Perifanou, M.; Economides, A.A. Exploring teachers’ competences to integrate augmented reality in education: Results from an international study. TechTrends: Lead. Educ. Train. 2024, 68, 1208–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Inclusion Criteria (IC) | Exclusion Criteria (EC) |

|---|---|---|

| Document type * | IC 1. Peer-reviewed articles published in indexed scientific journals | EC 1. Non-peer reviewed articles |

| Focus of the study | IC 2. Studies with a primary focus on the objectives of the review | EC 2. Studies focused on unrelated outcomes |

| Population | IC 3. Gifted students | EC 3. Non-gifted students |

| Learning context | IC 4. SLA in general and ESL/EFL | EC 4. Contexts outside ESL/EFL |

| Immersive technology | IC 5. Studies using AR | EC 5. Studies using VR, MR, XR |

| Publication Language * | IC 6. English, Spanish, French, or Italian | EC 6. Other languages that were not English, Spanish, French or Italian |

| Publication year * | IC 7. 2020–2025 | EC 7. Years prior to 2020 or after 2025 |

| Publication access * | IC 8. Open access | EC 8. Non-open access |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oto-Millera, N.; Pellicer-Ortín, S.; Bustamante, J.C. Augmented Reality in English Language Acquisition Among Gifted Learners: A Systematic Scoping Review (2020–2025). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111487

Oto-Millera N, Pellicer-Ortín S, Bustamante JC. Augmented Reality in English Language Acquisition Among Gifted Learners: A Systematic Scoping Review (2020–2025). Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111487

Chicago/Turabian StyleOto-Millera, Nerea, Silvia Pellicer-Ortín, and Juan Carlos Bustamante. 2025. "Augmented Reality in English Language Acquisition Among Gifted Learners: A Systematic Scoping Review (2020–2025)" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111487

APA StyleOto-Millera, N., Pellicer-Ortín, S., & Bustamante, J. C. (2025). Augmented Reality in English Language Acquisition Among Gifted Learners: A Systematic Scoping Review (2020–2025). Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11487. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111487