Target Tracking with Adaptive Morphological Correlation and Neural Predictive Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Morphological-correlation filter design: An adaptive correlation filtering method based on morphological operations is proposed for robust target tracking, providing an alternative to the conventional ridge-regularization formulation and improving robustness to scene perturbations.

- Correlation-plane postprocessing: A postprocessing stage based on synthetic-basis projection is introduced to refine the correlation response and improve target detection in cluttered scenes.

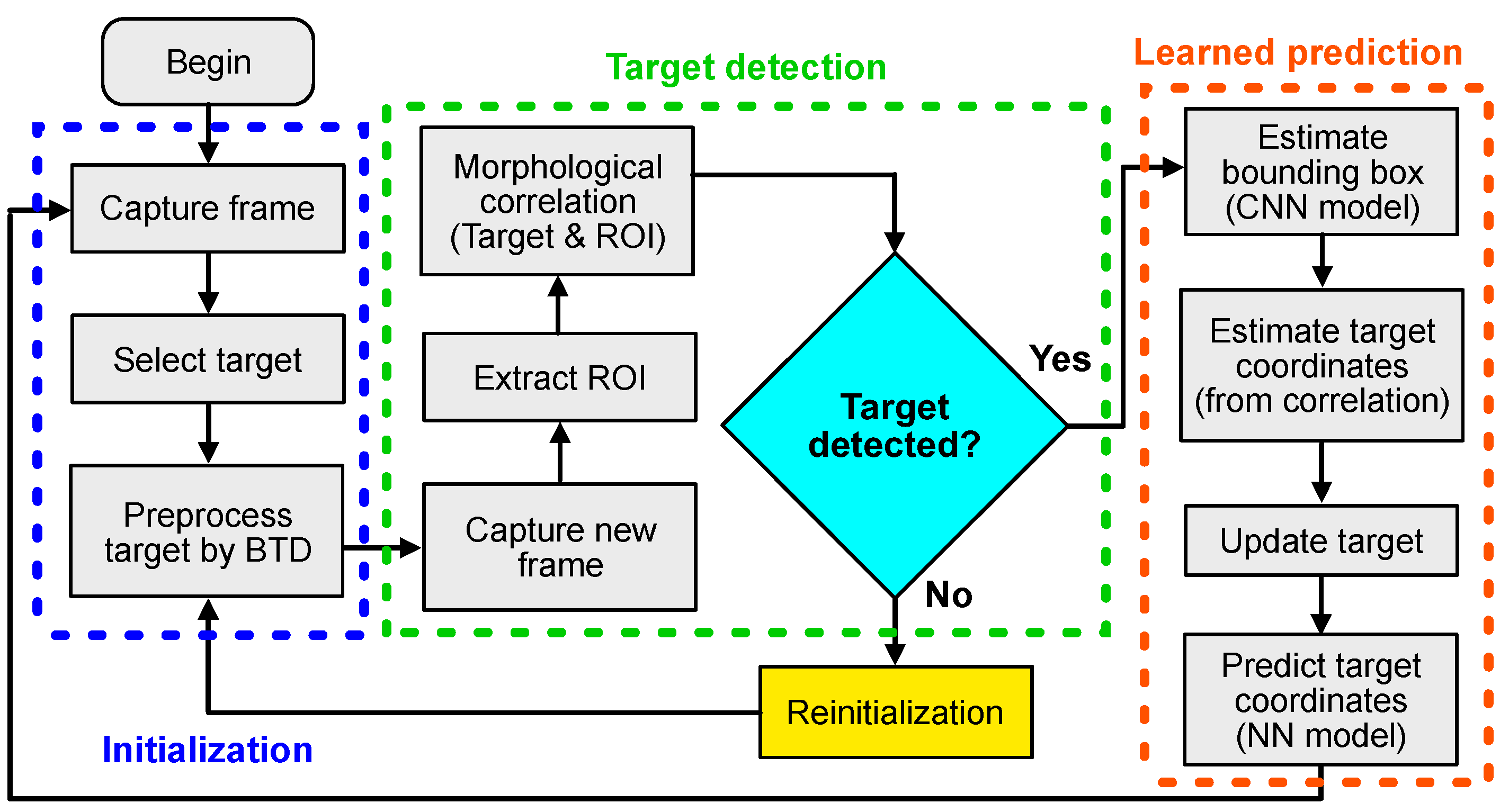

- Hybrid tracking framework: A tracking approach is developed that integrates an online-trained morphological correlation for target detection with neural models trained offline for target location prediction and bounding box estimation, achieving stable tracking trajectories across frames.

- Drift-correction and reinitialization mechanisms: Efficient methods for drift correction and tracking reinitialization are incorporated to maintain tracking stability under occlusions, illumination variations, and temporary target loss.

2. Proposed Target Tracking Method

2.1. Target Recognition Based on Morphological Correlation

2.2. Postprocessing of the Correlation Plane Through Synthetic Basis Projection

2.3. Target Tracking Based on Morphological Correlation Filtering and Neural Predictive Models

3. Results

3.1. Description of Experiments

Performance Evaluation Metrics

3.2. Implementation Details

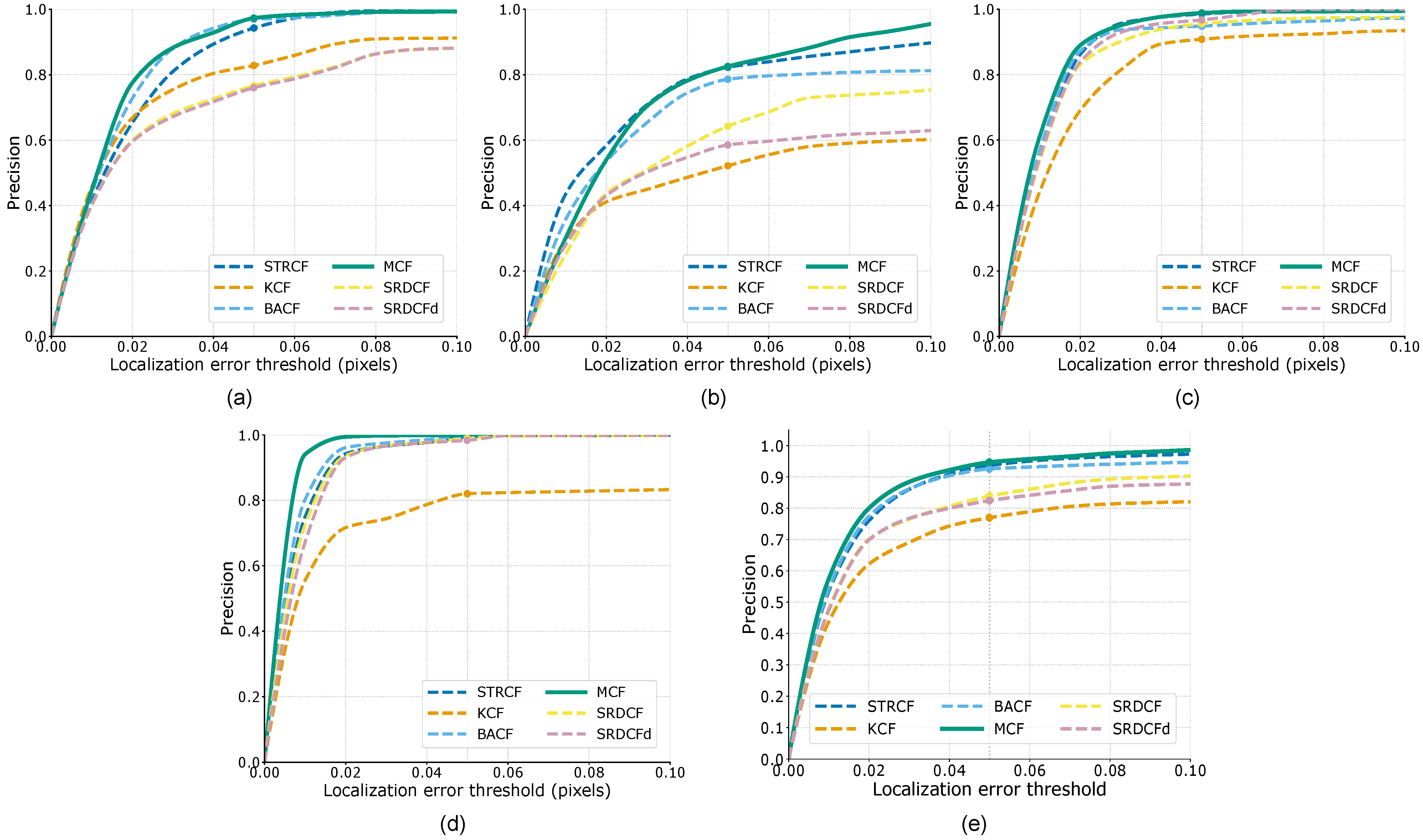

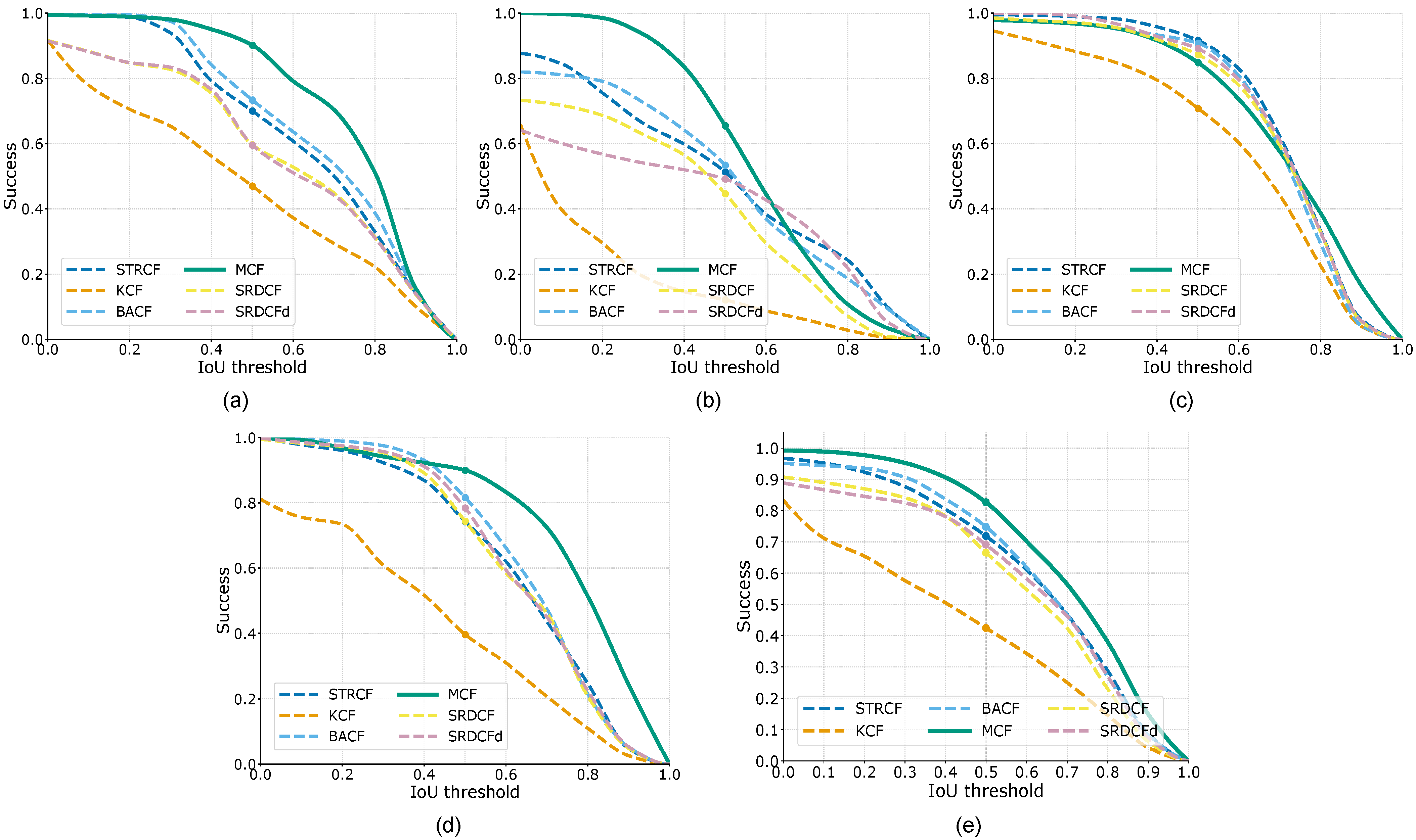

3.3. Performance Evaluation Results

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| ABDR | Aggregated Binary Dissimilarity-to-Matching Ratio |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BACF | Background-Aware Correlation Filters |

| BTD | Binary Threshold Decomposition |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CS | Cosine Similarity |

| DR | Detection Rate |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| GOT-10k | Generic Object Tracking Benchmark (10k) |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| HSV | Hue, Saturation, Value |

| IoU | Intersection Over Union |

| KCF | Kernelized Correlation Filters |

| LaSOT | Large-scale Single Object Tracking |

| MATLAB | Matrix Laboratory |

| MCF | Morphological Correlation Filtering |

| MIL | Multiple Instance Learning |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NLE | Normalized Location Error |

| NN | Neural Network |

| NumPy | Numerical Python |

| OpenCV | Open Source Computer Vision Library |

| OTB50 | Object Tracking Benchmark (50) |

| PyTorch | Python Torch |

| Python | Python Programming Language |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SciPy | Scientific Python |

| SRDCF | Spatially Regularized Discriminative Correlation Filters |

| SRDCFd | SRDCF with decontamination (adaptive decontamination variant) |

| STRCF | Spatial–Temporal Regularized Correlation Filters |

| STRCF-d | STRCF with deconvolutional refinement |

| Struck | Structured Output Tracking with Kernels |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| TLD | Tracking–Learning–Detection |

| UAV123 | UAV Tracking Benchmark (UAV123) |

| macOS | Apple’s Macintosh operating system |

Appendix A. Neural Models for Bounding Box and Position Prediction

Appendix A.1. Neural Network Model for Target Position Prediction

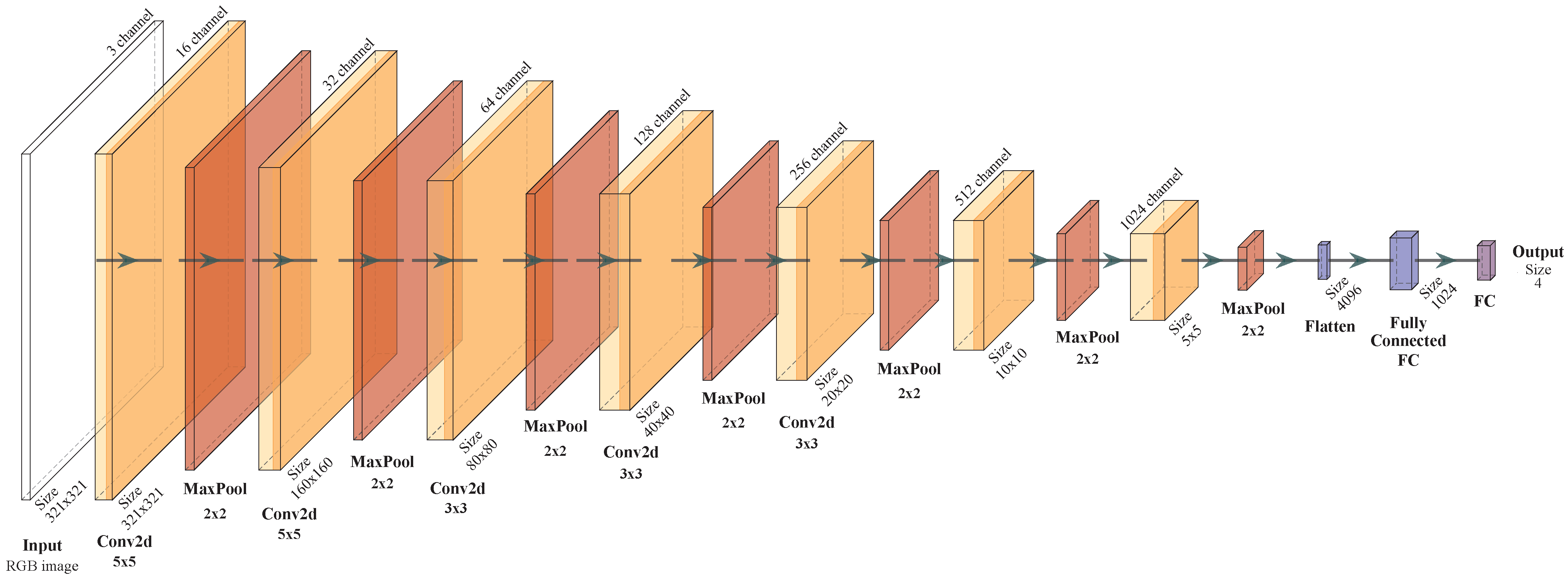

Appendix A.2. Convolutional Neural Network Model for Bounding Box Prediction

Appendix B. Drift Correction Method

Appendix C. Tracking Reinitialization

References

- Zhao, G.; Meng, F.; Yang, C.; Wei, H.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, Z. A review of object tracking based on deep learning. Neurocomputing 2025, 651, 130988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Javed, O.; Shah, M. Object tracking: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2006, 38, 13-es. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeulders, A.W.M.; Chu, D.M.; Cucchiara, R.; Calderara, S.; Dehghan, A.; Shah, M. Visual tracking: An experimental survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 36, 1442–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Lim, J.; Yang, M.H. Object Tracking Benchmark. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1834–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Ramirez, V.H.; Picos, K.; Kober, V. Target tracking in nonuniform illumination conditions using locally adaptive correlation filters. Opt. Commun. 2014, 323, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaparrone, G.; Luque Sánchez, F.; Tabik, S.; Troiano, L.; Tagliaferri, R.; Herrera, F. Deep learning in video multi-object tracking: A survey. Neurocomputing 2020, 381, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.A.; Lim, J.; Lin, R.S.; Yang, M.H. Incremental learning for robust visual tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2008, 77, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danelljan, M.; Hager, G.; Khan, F.S.; Felsberg, M. Discriminative Scale Space Tracking. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1561–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chan, A.B. Visual Tracking via Dynamic Memory Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Shen, J.; Porikli, F.; Luo, J.; Shao, L. Adaptive Siamese Tracking with a Compact Latent Network. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 8049–8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babenko, B.; Yang, M.H.; Belongie, S. Robust Object Tracking with Online Multiple Instance Learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, S.; Golodetz, S.; Saffari, A.; Vineet, V.; Cheng, M.M.; Hicks, S.L.; Torr, P.H. Struck: Structured Output Tracking with Kernels. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 2096–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalal, Z.; Mikolajczyk, K.; Matas, J. Tracking-Learning-Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 34, 1409–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolme, D.S.; Beveridge, J.R.; Draper, B.A.; Lui, Y.M. Visual Object Tracking Using Adaptive Correlation Filters. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010; pp. 2544–2550. [Google Scholar]

- Gaxiola, L.N.; Diaz-Ramirez, V.H.; Tapia, J.J.; García-Martínez, P. Target tracking with dynamically adaptive correlation. Opt. Commun. 2016, 365, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.F.; Caseiro, R.; Martins, P.; Batista, J. High-speed tracking with kernelized correlation filters. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danelljan, M.; Hager, G.; Shahbaz Khan, F.; Felsberg, M. Learning spatially regularized correlation filters for visual tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 4310–4318. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, S. Learning Adaptive Sparse Spatially-Regularized Correlation Filters for Visual Tracking. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danelljan, M.; Häger, G.; Khan, F.S.; Felsberg, M. Adaptive Decontamination of the Training Set: A Unified Formulation for Discriminative Visual Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1430–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, F.; Man, Y. Robust Visual Tracking via an Improved Background Aware Correlation Filter. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 24877–24888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yuan, T.; He, Y.; Wang, J. A background-aware correlation filter with adaptive saliency-aware regularization for visual tracking. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 6359–6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Tian, C.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.H. Learning Spatial-Temporal Regularized Correlation Filters for Visual Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4904–4913. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.V.K.V.; Mahalanobis, A.; Juday, R.D. Correlation Pattern Recognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vijaya Kumar, B.; Hassebrook, L. Performance measures for correlation filters. Appl. Opt. 1990, 29, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroslavsky, L. The theory of optimal methods for localization of objects in pictures. Prog. Opt. 1993, 32, 145–201. [Google Scholar]

- Javidi, B.; Wang, J. Design of filters to detect a noisy target in nonoverlapping background noise. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1994, 11, 2604–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, B.; Parchekani, F.; Zhang, G. Minimum-mean-square-error filters for detecting a noisy target in background noise. Appl. Opt. 1996, 35, 6964–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javidi, B.; Wang, J. Optimum filter for detecting a target in multiplicative noise and additive noise. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1997, 14, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, V.; Campos, J. Accuracy of location measurement of a noisy target in a nonoverlapping background. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1996, 13, 1653–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouerhani, Y.; Jridi, M.; Alfalou, A.; Brosseau, C. Optimized pre-processing input-plane GPU implementation of an optical face recognition technique using a segmented phase-only composite filter. Opt. Commun. 2013, 289, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragos, P. Optimal morphological approaches to image matching and object detection. In Proceedings of the 1988 Second International Conference on Computer Vision, Tampa, FL, USA, 5–8 December 1988; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 695–696. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Diaz, S.; Kober, V.I. Nonlinear synthetic discriminant function filters for illumination-invariant pattern recognition. Opt. Eng. 2008, 47, 067201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Ramirez, V.H.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, M.; Kober, V.; Juarez-Salazar, R. Stereo Image Matching Using Adaptive Morphological Correlation. Sensors 2022, 22, 9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Bai, H.; Lin, L.; Yang, F.; Chu, P.; Deng, G.; Yu, S.; Harshit; Huang, M.; Liu, J.; et al. LaSOT: A High-quality Large-scale Single Object Tracking Benchmark. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, X.; Huang, K. GOT-10k: A Large High-Diversity Benchmark for Generic Object Tracking in the Wild. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 1562–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Smith, N.; Ghanem, B. A Benchmark and Simulator for UAV Tracking. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Rong Li, X.; Jilkov, V. Survey of maneuvering target tracking. Part I. Dynamic models. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2003, 39, 1333–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of Oriented Gradients for Human Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Tracker | NLE | IoU | DR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOT-10k | STRCF | 70.1 | ||

| BACF | 73.4 | |||

| SRDCF | 59.7 | |||

| SRDCFd | 59.6 | |||

| KCF | 47.0 | |||

| MCF | 90.2 | |||

| LaSOT | STRCF | 51.4 | ||

| BACF | 53.5 | |||

| SRDCF | 44.7 | |||

| SRDCFd | 49.2 | |||

| KCF | 12.1 | |||

| MCF | 65.6 | |||

| OTB50 | STRCF | 91.7 | ||

| BACF | 90.8 | |||

| SRDCF | 87.3 | |||

| SRDCFd | 89.1 | |||

| KCF | 70.8 | |||

| MCF | 89.9 | |||

| UAV123 | STRCF | 74.4 | ||

| BACF | 81.7 | |||

| SRDCF | 74.5 | |||

| SRDCFd | 78.5 | |||

| KCF | 39.7 | |||

| MCF | 90.1 | |||

| All datasets | STRCF | 71.9 | ||

| BACF | 74.8 | |||

| SRDCF | 66.5 | |||

| SRDCFd | 69.1 | |||

| KCF | 42.4 | |||

| MCF | 83.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diaz-Ramirez, V.H.; Gaxiola-Sanchez, L.N. Target Tracking with Adaptive Morphological Correlation and Neural Predictive Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111406

Diaz-Ramirez VH, Gaxiola-Sanchez LN. Target Tracking with Adaptive Morphological Correlation and Neural Predictive Modeling. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111406

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiaz-Ramirez, Victor H., and Leopoldo N. Gaxiola-Sanchez. 2025. "Target Tracking with Adaptive Morphological Correlation and Neural Predictive Modeling" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111406

APA StyleDiaz-Ramirez, V. H., & Gaxiola-Sanchez, L. N. (2025). Target Tracking with Adaptive Morphological Correlation and Neural Predictive Modeling. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111406