Finite Element Model Updating of Axisymmetric Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

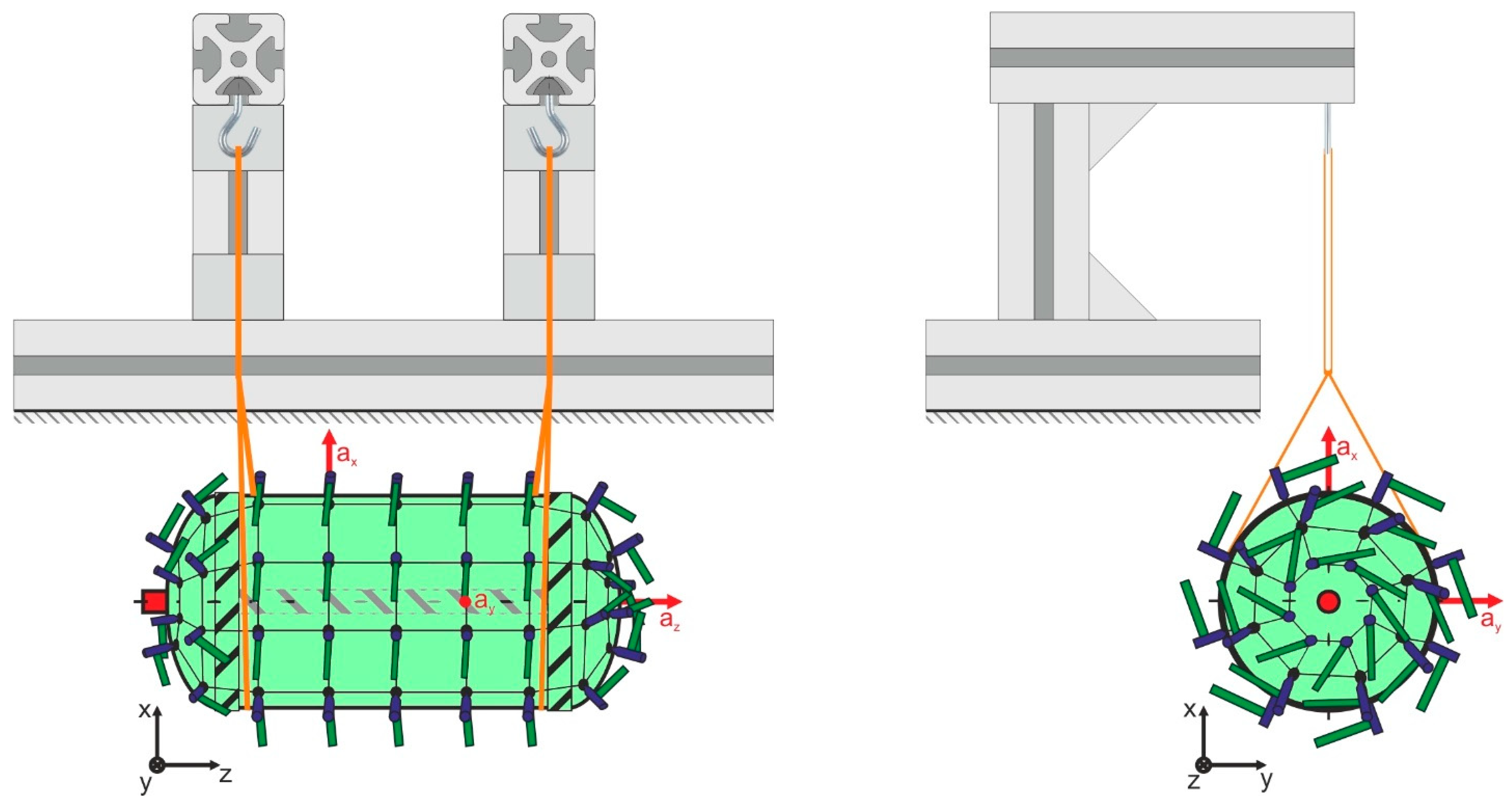

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Estimation of the Pipe Modal Parameters

2.2. Numerical Model of the Pipe and Its Updating

2.2.1. FEMU of the Pipe with One Design Variable

- The selected modes are well identified within EMA, i.e., with stable poles, consistent modal shape, and reproducibility.

- The selected modes are separated and do not correspond to modes with closely spaced natural frequencies, so that they cannot be mistaken for each other.

- The selected modes have the highest participation factor from the FEA-obtained set of modes.

- To seek a target of 260 Hz for the natural frequency of the pipe’s first deformation mode.

- To seek a target of 405 Hz for the natural frequency of the pipe’s third deformation mode.

- To seek a target of 762 Hz for the natural frequency of the pipe’s sixth deformation mode.

2.2.2. FEMU of the Pipe with Two Design Variables

- A)

- The objectives with a higher priority are as follows:

- To seek a target of 260 Hz for the natural frequency of the first deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 3916 g for the mass of the pipe.

- B)

- The objectives with a default priority are as follows:

- To seek a target of 405 Hz for the natural frequency of the third deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 762 Hz for the natural frequency of the sixth deformation mode.

3. Validation of the Methodology

3.1. Estimation of the Pressure Vessel Modal Parameters

3.2. Numerical Modal Analysis of the Pressure Vessel

- T1 = 1.9 mm;

- T2 = T3 = 2.0 mm;

- T4 = T5 = 2.1 mm;

- T6 = T7 = 2.2 mm;

- T8 = 2.5 mm;

- T9 = T10 = T11 = 2.9 mm.

- To seek a target of 1665 Hz for the natural frequency of the first deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 2209 Hz for the natural frequency of the second deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 3754 Hz for the natural frequency of the third deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 3830 Hz for the natural frequency of the fourth deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 4501 Hz for the natural frequency of the fifth deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 4677 Hz for the natural frequency of the sixth deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 5593 Hz for the natural frequency of the seventh deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 6009 Hz for the natural frequency of the eighth deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 6033 Hz for the natural frequency of the ninth deformation mode;

- To seek a target of 6222 Hz for the natural frequency of the tenth deformation mode.

- T1 up to T7 determined in the range {1.6; 2.5} (mm);

- T8 determined in the range {1.8; 3.0} (mm);

- T9 up to T11 determined in the range {2.2; 3.2} (mm).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The authors did not neglect or average the repeated modes with split frequencies.

- When selecting the optimization objectives, one of the repeated modes was always selected, specifically the one found on the first singular curve, i.e., the mode with the higher frequency response.

- Using mass as one the optimization functions can lead to improvement in the quality and convergence of the results.

- Significant improvement in the results was obtained after creating and optimization of the vessel 3D model, describing the through-thickness stiffness distribution in the vessel more realistically.

- The modeling of the overlap weld joints causes not only addition of local stiffness and mass but also overall mass redistribution occurring after design variable optimization.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brownjohn, J.M.W.; Xia, P.Q. Dynamic assessment of curved cable-stayed bridge by model updating. J. Struct. Eng. 2000, 126, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownjohn, J.M.W.; Moyo, P.; Omenzetter, P.; Lu, Y. Assessment of highway bridge upgrading by dynamic testing and finite-element model updating. J. Bridge Eng. 2003, 8, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friswell, M.I.; Mottershead, J.E. Finite Element Model Updating in Structural Dynamics, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, M.; Bar-Itzhack, I.Y. Optimal Weighted Orthogonalization of Measured Modes. AIAA J. 1978, 16, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A. Mass Matrix Correction Using an Incomplete Set of Measured Modes. AIAA J. 1979, 17, 1147–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.; Nagy, E.J. Improvement of a Large Analytical Model Using Test Data. AIAA J. 1983, 21, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottershead, J.E.; Friswell, M.I. Model Updating in Structural Dynamics: A Survey. J. Sound Vib. 1993, 167, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.M.; Ewins, D.J. Analytical model improvement using frequency response functions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 1994, 8, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.M.; Ewins, D.J. Model Updating Using FRF Data. In Proceedings of the 15th International Seminar on Modal Analysis, Leuven, Belgium, 19–21 September 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esfandiari, A.; Bakhtiari-Nejad, F.; Sanayei, M.; Rahai, A. Structural finite element model updating using transfer function data. Comput. Struct. 2010, 88, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Xia, Y.; Xu, Y.L.; Zhu, H.P. Substructure based approach to finite element model updating. Comput. Struct. 2011, 89, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottershead, J.E.; Link, M.; Friswell, M.I. The sensitivity method in finite element model updating: A tutorial. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2011, 25, 2275–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, F.; Valluzzi, M.R.; Salvalaggio, M.; Minello, A.; Modena, C. Operational modal analysis for the characterization of ancient water towers in Pompeii. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 3374–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru, D.; Ivorra, S.; Baeza, F.J.; Reynau, R.; Foti, D. OMA Dynamic identification of a masonry chimney with severe cracking condition. In Proceedings of the 6th International Operational Modal Analysis Conference, IOMAC15, Gijon, Spain, 12–14 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saidin, S.S.; Kudus, S.A.; Jamadin, A.; Anuar, M.A.; Amin, N.M.; Ibrahim, Z.; Zakaria, A.B.; Sugiura, K. Operational modal analysis and finite element model updating of ultra-high-performance concrete bridge based on ambient vibration test. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calayır, Y.; Yetkin, M.; Erkek, H. Finite element model updating of masonry minarets by using operational modal analysis method. Structures 2021, 34, 3501–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, O.; Alkhamis, K.; Abdeljaber, O.; Alsharo, A.; Hussein, M. Operational modal analysis and finite element model updating of a 230 m tall tower. Structures 2022, 37, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, F.; Yang, S.; Yin, W.; Xu, Z.; He, S. Modal characteristics of vertical vibration in typical steel frame structures under road traffic loads: Actual measurements and finite element model update. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Calçada, R.; Delgado, R.; Brehm, M.; Zabel, V. Finite element model updating of a bowstring-arch railway bridge based on experimental modal parameters. Eng. Struct. 2012, 40, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.X.; Yu, K.P. Finite element model updating of damped structures using vibration test data under base excitation. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 340, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, F.; Shokrollahi, S.; Jamal-Omidi, M.; Ahmadian, H. A model updating method for hybrid composite/aluminum bolted joints using modal test data. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 396, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, G.; Meruane, V. Mechanical properties updating of a non-uniform natural fibre composite panel by means of a parallel genetic algorithm. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 94, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, M.; Artero-Guerrero, J.A.; Pernas-Sánchez, J.; Varas, D. Model updating of uncertain parameters of carbon/epoxy composite plates from experimental modal data. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 455, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiras, J.N.; Payan, C.; Rakotonarivo, S.; Garnier, V. Experimental modal analysis and finite element model updating for structural health monitoring of reinforced concrete radioactive waste packages. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 180, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, A.; Chakraborty, S. Damage identification of reinforced concrete slabs using experimental modal testing and finite element model updating. Structures 2024, 67, 107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-García, A.; Pernía-Espinoza, A.V.; Fernández-Martínez, R.; Martínez-de-Pisón-Ascacíbar, F.J. Combining genetic algorithms and the finite element method to improve steel industrial processes. J. Appl. Log. 2012, 10, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, P.T.; Tsirkas, S.O.; Kabouridis, G.; Yiannopoulos, A.C.; Giannopoulos, G.I. Genetic-Based Optimization of the Manufacturing Process of a Robotic Arm under Fuzziness. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 1, 168014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhi, Q.; Sun, H.; Li, D.; Ding, X. Genetic Algorithm Optimization Design of Gradient Conformal Chiral Metamaterials and 3D Printing Verification for Morphing Wings. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagara, M.; Pástor, M.; Lengvarský, P.; Palička, P.; Huňady, R. Modal Parameters Estimation of Circular Plates Manufactured by FDM Technique Using Vibrometry: A Comparative Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12205:2001; Transportable Gas Cylinders—Non-Refillable Metallic Gas Cylinders. European Committee for Standardization: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015.

| Estimated Natural Frequency (Hz) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Mode 4 | Mode 5 | Mode 6 | Mode 7 | Mode 8 | Mode 9 | Mode 10 |

| 260 | 263 | 405 α | 725 α | 740 α | 762 α | 845 α | 862 α | 879 α | 1088 α |

| † | † | 407 β | 735 β | 743 β | 766 β | 858 β | 865 β | 893 β | 1100 β |

| Estimated Damping Ratio (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Mode 4 | Mode 5 | Mode 6 | Mode 7 | Mode 8 | Mode 9 | Mode 10 |

| 0.1853 | 0.1951 | 0.1311 α | 0.2349 α | 0.0876 α | 0.1173 α | 0.1211 α | 0.1051 α | 0.1802 α | 0.0930 α |

| † | † | 0.1291 β | 0.0986 β | 0.0877 β | 0.0925 β | 0.0787 β | 0.0803 β | 0.1702 β | 0.0780 β |

| FEA–Natural Frequency (Hz) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Mode 4 | Mode 5 | Mode 6 | Mode 7 | Mode 8 | Mode 9 | Mode 10 |

| 264.9 α | 266.7 α | 403.1 α | 748.6 α | 750.8 α | 774.0 α | 830.9 α | 859.0 α | 867.5 α | 1084.1 α |

| 264.9 β | 266.7 β | 403.1 β | 748.6 β | 750.8 β | 774.0 β | 830.9 β | 859.0 β | 867.5 β | 1084.1 β |

| Design Variable Ro | Optimization Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Candidate Point 1 | Candidate Point 2 | Candidate Point 3 |

| Range 1 | 60.001 mm | 67 mm | 61.313 mm | 61.313 mm | 61.313 mm |

| Range 2 | 60.001 mm | 63 mm | 61.313 mm | 61.313 mm | 61.313 mm |

| Range 3 | 60.001 mm | 62 mm | 61.434 mm | 61.434 mm | 61.434 mm |

| Range 4 | 60.001 mm | 61.8 mm | 61.477 mm | 61.478 mm | 61.478 mm |

| Range 5 | 60.001 mm | 61.6 mm | 61.489 mm | 61.500 mm | 61.500 mm |

| Mode | EMA m = 3916 g | FEA Ro = 61.313 mm m = 3536 g | FEA Ro = 61.434 mm m = 3866 g | FEA Ro = 61.477 mm m = 3983 g | FEA Ro = 61.489 mm m = 4014 g | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (Hz) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | |

| 1 | 260 | 232.6 α | 10.55 | 253.5 α | 2.51 | 260.9 α | 0.34 | 263.0 α | 1.14 |

| † | 232.6 β | # | 253.5 β | # | 260.9 β | # | 263.0 β | # | |

| 2 | 263 | 234.2 α | 10.95 | 255.2 α | 2.95 | 262.7 α | 0.12 | 264.8 α | 0.67 |

| † | 234.2 β | # | 255.2 β | # | 262.7 β | # | 264.8 β | # | |

| 3 | 405 α | 380.8 α | 5.97 | 395.1 α | 2.44 | 400.3 α | 1.16 | 401.8 α | 0.79 |

| 407 β | 380.8 β | 6.43 | 395.1 β | 2.92 | 400.3 β | 1.64 | 401.8 β | 1.28 | |

| 4 | 725 α | 657.5 α | 9.31 | 716.5 α | 1.17 | 737.4 α | 1.71 | 743.3 α | 2.52 |

| 735 β | 657.5 β | 10.55 | 716.5 β | 2.51 | 737.4 β | 0.33 | 743.3 β | 1.13 | |

| 5 | 740 α | 659.4 α | 10.89 | 718.6 α | 2.89 | 739.6 α | 0.06 | 745.4 α | 0.73 |

| 743 β | 659.4 β | 11.25 | 718.6 β | 3.29 | 739.6 β | 0.46 | 745.4 β | 0.32 | |

| 6 | 762 α | 683.0 α | 10.36 | 741.9 α | 2.64 | 762.8 α | 0.10 | 768.6 α | 0.87 |

| 766 β | 683.0 β | 10.83 | 741.9 β | 3.15 | 762.8 β | 0.42 | 768.6 β | 0.34 | |

| 7 | 845 α | 783.1 α | 7.33 | 826.3 α | 2.22 | 829.2 α | 1.87 | 830.1 α | 1.77 |

| 858 β | 783.1 β | 8.73 | 826.3 β | 3.70 | 829.2 β | 3.35 | 830.1 β | 3.25 | |

| 8 | 862 α | 818.3 α | 5.07 | 837.5 α | 2.85 | 857.0 α | 0.58 | 858.9 α | 0.36 |

| 865 β | 818.3 β | 5.40 | 837.5 β | 3.18 | 857.0 β | 0.93 | 858.9 β | 0.70 | |

| 9 | 879 α | 857.9 α | 2.40 | 858.6 α | 2.32 | 858.8 α | 2.29 | 862.4 α | 1.88 |

| 893 β | 857.9 β | 3.93 | 858.6 β | 3.85 | 858.8 β | 3.83 | 862.4 β | 3.42 | |

| 10 | 1088 α | 1012.9 α | 6.90 | 1058.6 α | 2.70 | 1075.2 α | 1.18 | 1079.8 α | 0.75 |

| 1100 β | 1012.9 β | 7.92 | 1058.6 β | 3.76 | 1075.2 β | 2.25 | 1079.8 β | 1.84 | |

| Δmean: | 8.04 | 2.84 | 1.26 | 1.32 | |||||

| Design Variable Ri | Design Variable Ro | Optimization Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Candidate Point 1 | Candidate Point 2 | Candidate Point 3 |

| Range 1 | 55.0 mm | 60.0 mm | 60.001 mm | 65.0 mm | Ri = 59.799 mm Ro = 62.677 mm | Ri = 59.806 mm Ro = 62.694 mm | Ri = 59.824 mm Ro = 62.697 mm |

| Range 2 | 57.5 mm | 60.0 mm | 60.001 mm | 62.5 mm | Ri = 59.620 mm Ro = 61.632 mm | Ri = 59.602 mm Ro = 61.583 mm | Ri = 59.589 mm Ro = 61.525 mm |

| Range 3 | 59.5 mm | 60.5 mm | 60.6 mm | 62.0 mm | Ri = 59.500 mm Ro = 60.959 mm | Ri = 59.528 mm Ro = 60.986 mm | Ri = 59.535 mm Ro = 60.992 mm |

| Mode | EMA m = 3916 g | FEA Ri = 59.824 mm Ro = 62.697 mm m = 7812 g | FEA Ri = 59.589 mm Ro = 61.525 mm m = 5204 g | FEA Ri = 59.528 mm Ro = 60.986 mm m = 3900 g | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (Hz) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | |

| 1 | 260 | 498.3 α | 91.65 | 343.9 α | 32.27 | 261.6 α | 0.62 |

| † | 498.3 β | # | 343.9 β | # | 261.7 β | # | |

| 2 | 263 | 501.6 α | 90.72 | 346.2 α | 31.63 | 263.4 α | 0.15 |

| † | 501.6 β | # | 346.2 β | # | 263.4 β | # | |

| 3 | 405 α | 595.9 α | 47.14 | 462.1 α | 14.10 | 399.1 α | 1.46 |

| 407 β | 595.9 β | 46.41 | 462.1 β | 13.54 | 399.1 β | 1.94 | |

| 4 | 725 α | 865 α | 19.31 | 856.8 α | 18.18 | 739.5 α | 2.00 |

| 735 β | 865 β | 17.69 | 856.8 β | 16.57 | 739.5 β | 0.61 | |

| 5 | 740 α | 954.5 α | 28.99 | 862.4 α | 16.54 | 741.6 α | 0.22 |

| 743 β | 954.5 β | 28.47 | 862.4 β | 16.07 | 741.6 β | 0.19 | |

| 6 | 762 α | 1406.1 α | 84.53 | 971.4 α | 27.48 | 764.4 α | 0.31 |

| 766 β | 1406.2 β | 83.58 | 971.6 β | 26.84 | 764.5 β | 0.20 | |

| 7 | 845 α | 1410 α | 66.86 | 974.1 α | 15.28 | 824.3 α | 2.45 |

| 858 β | 1410 β | 64.34 | 974.3 β | 13.55 | 824.3 β | 3.93 | |

| 8 | 862 α | 1436.8 α | 66.68 | 997.3 α | 15.70 | 853.2 α | 1.02 |

| 865 β | 1436.8 β | 66.10 | 997.5 β | 15.32 | 853.2 β | 1.36 | |

| 9 | 879 α | 1513.4 α | 72.17 | 1079.8 α | 22.84 | 857.2 α | 2.48 |

| 893 β | 1513.4 β | 69.47 | 1079.9 β | 20.93 | 857.2 β | 4.01 | |

| 10 | 1088 α | 1559 α | 43.29 | 1270.2 α | 16.75 | 1072.7 α | 1.41 |

| 1100 β | 1559 β | 41.73 | 1270.3 β | 15.48 | 1072.7 β | 2.48 | |

| Δmean: | 57.17 | 19.39 | 1.49 | ||||

| Estimated Natural Frequency (Hz) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Mode 4 | Mode 5 | Mode 6 | Mode 7 | Mode 8 | Mode 9 | Mode 10 |

| 80 bar | 1788 α | 2489 α | 3923 α | 4146 | 4533 α | 4945 α | 5560 α | 6113 α | 6347 α | † |

| 1794 β | 2490 β | 3935 β | † | 4536 β | 4948 β | 5571 β | 6141 β | 6356 β | † | |

| 40 bar | 1734 α | 2365 α | 3849 α | 4006 | 4522 α | 4823 α | 5581 α | 6068 α | 6204 α | 6359 |

| 1740 β | 2367 β | 3860 β | † | 4524 β | 4830 β | 5596 β | 6095 β | 6215 β | † | |

| 0 bar | 1665 α | 2209 α | 3754 α | 3830 | 4501 α | 4677 α | 5593 α | 6009 α | 6033 α | 6222 α |

| 1673 β | 2211 β | 3765 β | † | 4504 β | 4685 β | 5617 β | 6028 β | 6044 β | 6248 β | |

| Estimated Damping Ratio (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | Mode 4 | Mode 5 | Mode 6 | Mode 7 | Mode 8 | Mode 9 | Mode 10 |

| 80 bar | 0.1101 α | 0.0941 α | 0.0877 α | 0.0847 | 0.0773 α | 0.0759 α | 0.0622 α | 0.0872 α | 0.0771 α | † |

| 0.1201 β | 0.0948 β | 0.0881 β | † | 0.0785 β | 0.0757 β | 0.0609 β | 0.0877 β | 0.0792 β | † | |

| 40 bar | 0.1015 α | 0.0818 α | 0.0621 α | 0.0613 | 0.0574 α | 0.0660 α | 0.0503 α | 0.0743 α | 0.0662 α | 0.0610 |

| 0.1007 β | 0.0831 β | 0.0649 β | † | 0.0581 β | 0.0631 β | 0.0483 β | 0.0760 β | 0.0648 β | † | |

| 0 bar | 0.0579 α | 0.0499 α | 0.0453 α | 0.0420 | 0.0458 α | 0.0442 α | 0.0410 α | 0.0465 α | 0.0466 α | 0.0439 α |

| 0.0593 β | 0.0503 β | 0.0469 β | † | 0.0436 β | 0.0448 β | 0.0403 β | 0.0474 β | 0.0469 β | 0.0469 β | |

| Material Testing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical composition of the material (%) | Fe | Mn | Si | C | Ti | Nb | P | S | |

| 97.898 | 1.4566 | 0.1986 | 0.1974 | 0.0148 | 0.0052 | 0.0044 | <0.001 | ||

| Mechanical properties of the material | Yield Strength = 365 MPa Tensile Strength = 540 MPa Modulus of Elasticity = 200,000 MPa Density = 7850 kg/m3 | ||||||||

| Surface | Ti (mm) | EMA | FEA (Initial) | FEA (After FEMU) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (Hz) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | ||

| S1 | 1.949 | 1665 α | 1603.4 α | 3.70 | 1622.9 α | 2.53 |

| S2 | 2.048 | 1673 β | 1610.4 β | 3.74 | 1630.2 β | 2.56 |

| S3 | 2.120 | 2209 α | 2126.3 α | 3.74 | 2229.7 α | 0.94 |

| S4 | 2.170 | 2211 β | 2147.5 β | 2.87 | 2246.4 β | 1.60 |

| S5 | 2.164 | 3754 α | 3088.0 α | 17.74 | 3457.4 α | 7.90 |

| S6 | 2.110 | 3765 β | 3089.0 β | 17.95 | 3458.6 β | 8.14 |

| S7 | 2.193 | 3830 | 3558.5 α | 7.09 | 3635.1 α | 5.09 |

| S8 | 2.488 | † | 3578.7 β | # | 3659.8 β | # |

| S9 | 2.895 | 4501 α | 3734.8 α | 17.02 | 3941.8 α | 12.42 |

| S10 | 2.972 | 4504 β | 3770.8 β | 16.28 | 3967.2 β | 11.92 |

| S11 | 2.901 | 4677 α | 4425.2 α | 5.38 | 4463.4 α | 4.57 |

| 4685 β | 4439.2 β | 5.25 | 4473.7 β | 4.51 | ||

| 5593 α | 4441.9 α | 20.58 | 4626.1 α | 17.29 | ||

| 5617 β | 4460.8 β | 20.58 | 4652.6 β | 17.17 | ||

| 6009 α | 4523.7 α | 24.72 | 4866.6 α | 19.01 | ||

| 6028 β | 5566.6 β | 7.65 | 5576.8 β | 7.49 | ||

| 6033 α | 5582.2 α | 7.47 | 5590.1 α | 7.34 | ||

| 6044 β | 5790.8 β | 4.19 | 5873.2 β | 2.83 | ||

| 6222 α | 5808.6 α | 6.64 | 5910.3 α | 5.01 | ||

| 6248 β | 5838.7 β | 6.55 | 6028.6 β | 3.51 | ||

| Δmean: | 10.48 | 7.46 | ||||

| Surf. | Ti (After FEMU) (mm) | EMA (80 Bar) | FEA (80 Bar) | EMA (40 Bar) | FEA (40 Bar) | EMA (0 Bar) | FEA (0 Bar) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (Hz) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | Freq. (Hz) | Freq. (Hz) | Diff. (%) | ||

| S1 | 1.791 | 1788 α | 1800.2 α | 0.68 | 1734 α | 1728.1 α | 0.34 | 1665 α | 1654.9 α | 0.61 |

| S2 | 1.898 | 1794 β | 1804.6 β | 0.59 | 1740 β | 1733.3 β | 0.39 | 1673 β | 1660.7 β | 0.74 |

| S3 | 1.911 | 2489 α | 2537.2 α | 1.94 | 2365 α | 2381.9 α | 0.71 | 2209 α | 2219.9 α | 0.49 |

| S4 | 2.718 | 2490 β | 2547.4 β | 2.31 | 2367 β | 2394.0 β | 1.14 | 2211 β | 2234.3 β | 1.05 |

| S5 | 2.744 | 3923 α | 3986.3 α | 1.61 | 3849 α | 3886.1 α | 0.96 | 3754 α | 3785.7 α | 0.84 |

| S6 | 1.812 | 3935 β | 3997.5 β | 1.59 | 3860 β | 3898.3 β | 0.99 | 3765 β | 3799.0 β | 0.90 |

| S7 | 1.784 | 4146 | 4192.4 α | 1.12 | 4006 | 4009.8 α | 0.09 | 3830 | 3823.4 α | 0.17 |

| S8 | 2.512 | † | 4213.7 β | # | † | 4033.6 β | # | † | 3849.8 β | # |

| S9 | 2.898 | 4533 α | 4511.4 α | 0.48 | 4522 α | 4480.5 α | 0.92 | 4501 α | 4450.1 α | 1.13 |

| S10 | 2.906 | 4536 β | 4511.7 β | 0.54 | 4524 β | 4480.9 β | 0.95 | 4504 β | 4450.7 β | 1.18 |

| S11 | 2.957 | 4945 α | 5044.9 α | 2.02 | 4823 α | 4890.2 α | 1.39 | 4677 α | 4734.4 α | 1.23 |

| 4948 β | 5064.4 β | 2.35 | 4830 β | 4911.5 β | 1.69 | 4685 β | 4757.7 β | 1.55 | ||

| 5560 α | 5511.5 α | 0.87 | 5581 α | 5506.3 α | 1.34 | 5593 α | 5501.4 α | 1.64 | ||

| 5571 β | 5522.7 β | 0.87 | 5596 β | 5517.6 β | 1.40 | 5617 β | 5512.8 β | 1.86 | ||

| 6113 α | 6075.5 α | 0.61 | 6068 α | 6006.3 α | 1.02 | 6009 α | 5937.9 α | 1.18 | ||

| 6141 β | 6085.4 β | 0.91 | 6095 β | 6016.6 β | 1.29 | 6028 β | 5948.6 β | 1.32 | ||

| 6347 α | 6384.9 α | 0.60 | 6204 α | 6191.1 α | 0.21 | 6033 α | 5996.0 α | 0.61 | ||

| 6356 β | 6420.3 β | 1.01 | 6215 β | 6229.1 β | 0.23 | 6044 β | 6036.8 β | 0.12 | ||

| † | 6562.9 α | # | 6359 | 6440.8 α | 1.29 | 6222 α | 6319.4 α | 1.57 | ||

| † | 6584.8 β | # | † | 6464.1 β | # | 6248 β | 6344.1 β | 1.54 | ||

| Δmean: | 1.18 | 0.91 | 1.04 | |||||||

| Design Variables’ Range of Feasible Values | Observed Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ro (mm) | ri (mm) | Diffmax (%) | Diffmin (%) | Δmean (%) | mnum (g) | t (mm) |

| {60.001; 67} | {60} | 10.95 | 2.4 | 8.04 | 3536 | 1.313 |

| {60.001; 63} | {60} | 10.95 | 2.4 | 8.04 | 3536 | 1.313 |

| {60.001; 62} | {60} | 3.76 | 1.17 | 2.84 | 3866 | 1.434 |

| {60.001; 61.8} | {60} | 3.83 | 0.06 | 1.26 | 3983 | 1.477 |

| {60.001; 61.6} | {60} | 3.42 | 0.32 | 1.32 | 4014 | 1.489 |

| {60.001; 65} | {55; 60} | 91.65 | 17.69 | 57.17 | 7812 | 2.873 |

| {60.001; 62.5} | {57.5; 60} | 32.27 | 13.54 | 19.39 | 5204 | 1.936 |

| {60.6; 62} | {59.5; 60.5} | 4.01 | 0.15 | 1.49 | 3900 | 1.458 |

| Model Type | Observed Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffmax (%) | Diffmin (%) | Δmean (%) | mnum (g) | mactual (g) | |

| Shell 0 bar (initial) Shell 0 bar (updated) | 24.72 | 2.87 | 10.48 | 1697.6 | 1768 |

| 19.01 | 0.94 | 7.46 | 1705.1 | 1768 | |

| 3D model 0 bar (updated) | 1.86 | 0.12 | 1.04 | 1780.2 | 1768 |

| 3D model 40 bar (updated) | 1.69 | 0.21 | 0.91 | 1780.2 | 1768 |

| 3D model 80 bar (updated) | 2.35 | 0.48 | 1.18 | 1780.2 | 1768 |

| Thickness | FEA Shell Initial | FEA Shell Updated | FEA 3D Model Updated | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 T2 | 1.9 mm | 1.949 mm | 1.791 mm | 1.81 ± 0.02 mm |

| 2.0 mm | 2.048 mm | 1.898 mm | 1.89 ± 0.03 mm | |

| T3 | 2.0 mm | 2.120 mm | 1.911 mm | 1.88 ± 0.03 mm |

| T4 | 2.1 mm | 2.170 mm | 2.718 mm | 2.09 ± 0.07 mm |

| T5 | 2.1 mm | 2.164 mm | 2.744 mm | 2.11 ± 0.08 mm |

| T6 | 2.2 mm | 2.110 mm | 1.812 mm | 1.92 ± 0.04 mm |

| T7 | 2.2 mm | 2.193 mm | 1.784 mm | 1.91 ± 0.03 mm |

| T8 | 2.5 mm | 2.488 mm | 2.512 mm | 2.40 ± 0.03 mm |

| T9 | 2.9 mm | 2.895 mm | 2.898 mm | 3.08 ± 0.08 mm |

| T10 | 2.9 mm | 2.972 mm | 2.906 mm | 3.06 ± 0.11 mm |

| T11 | 2.9 mm | 2.901 mm | 2.957 mm | 2.96 ± 0.05 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lengvarský, P.; Hagara, M.; Hagarová, L.; Briančin, J. Finite Element Model Updating of Axisymmetric Structures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111407

Lengvarský P, Hagara M, Hagarová L, Briančin J. Finite Element Model Updating of Axisymmetric Structures. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111407

Chicago/Turabian StyleLengvarský, Pavol, Martin Hagara, Lenka Hagarová, and Jaroslav Briančin. 2025. "Finite Element Model Updating of Axisymmetric Structures" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111407

APA StyleLengvarský, P., Hagara, M., Hagarová, L., & Briančin, J. (2025). Finite Element Model Updating of Axisymmetric Structures. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11407. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111407