1. Introduction

Autonomous driving technologies are transforming everyday mobility and the in-vehicle experience. As automation becomes commercially available, human drivers no longer need to always devote uninterrupted attention to manual control; under appropriate conditions, they can engage in non-driving-related tasks (NDRTs) such as reading or email while the vehicle handles routine control. At the same time, fully autonomous operation that allows the driver to relinquish responsibility entirely has not yet been realized in practice. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) distinguishes six levels of driving automation from Level 0 to Level 5 [

1]. Lower levels assist the human driver, whereas higher levels shift more driving authority to the system. The class of “conditional automated driving” under active commercialization corresponds to Level 3, in which the system primarily controls the vehicle but issues a takeover request (TOR) when operating limits are approached or exceeded. In such moments, the interface should provide clear visual and auditory alerts to ensure the driver perceives the TOR [

2], and the driver is expected to respond promptly and resume manual control.

Within this TOR-centric context, maintaining appropriate trust in the automated system is critical. As Parasuraman et al. [

3] noted, overtrust (trust that exceeds the system’s true capabilities) can lead drivers to rely on automation beyond its limits, undermining timely TOR responses and potentially increasing crash risk. Conversely, distrust or reluctance to accept a new automated system can suppress the benefits of conditional automation: drivers may over-monitor the roadway, allocate insufficient attention to the NDRT, and thus fail to realize comfort or productivity gains [

4]. In human–automation interaction, aligning human trust with actual system capabilities, termed trust calibration, is therefore a central goal [

5,

6].

Trust is dynamic: it changes with experience and varies by situation [

7,

8]. Recent studies have examined how interaction with automated driving systems (ADS) shapes this calibration and reported that initial trust can influence subsequent trajectories of adjustment [

9,

10,

11]. Wu et al. [

12] examined TOR timing and warning modality in Level-3 automated driving and found that longer TOR lead times increased trust without inducing confusion, while warning modality had no reliable main effect on trust and tri-modal warnings offered no clear advantage over bi-modal combinations. Swain et al. [

13] showed that augmented-reality HMI designs conveying shared intended pathway and object-recognition bounding boxes can reduce stress and increase perceived usefulness and intentions to use during conditional automation monitoring. Together, these findings underscore the roles of interface design and adequate time budgets in supporting calibrated trust during critical transition periods in Level-3 operation. However, evidence remains limited on how calibrated trust emerges through everyday interaction and how it co-varies with concurrent behavior during conditional automation. Additional work that measures trust change from multiple angles is needed.

Trust can be assessed via self-report questionnaires, behavioral measures, and psychophysiological indices [

14]. In this study, we focus on behavioral readouts to observe whether trust calibration is reflected in moment-to-moment behavior. Prior research has used gaze behavior [

15], NDRT engagement [

16,

17,

18], and takeover responses [

10,

18,

19,

20] as indirect indicators of trust. Building on this tradition, we examine (i) NDRT engagement—operationalized with a standard Surrogate Reference Task (SuRT) measure of successful clicks per second—and (ii) takeover reaction time (TOR-RT) as complementary behavioral expressions of trust during conditional automation. Consistent with our registered analysis plan, our primary predictor is trust, measured immediately after a brief familiarization period intended to align mental models with observed system behavior. We analyze associations between trust, NDRT throughput, and TOR-RT across four TOR exposures administered in a fixed order. This work offers two contributions: it re-examines behavioral indicators of trust in conditional automation by jointly analyzing NDRT throughput and TOR-RT alongside self-reported trust, and it tests whether changes in trust are accompanied by corresponding changes in behavior over repeated exposures—moving beyond static correlations to probe whether a calibrated, trust state coexists with more effective NDRT performance without incurring systematic costs in takeover readiness.

Accordingly, we ask whether a brief period of interaction followed by familiarization yields a calibrated trust state that is detectable both in self-report and in concurrent behavior during conditional automation. Specifically, we ask three research questions: First, does TOR interaction produce evidence of trust calibration in self-report? Second, is trust associated with greater NDRT throughput during automated driving, operationalized as successful SuRT clicks per second, across repeated exposures? Third, is trust associated with TOR-RT such that higher calibrated trust coexists with timely takeovers rather than systematic delays?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

For sample size planning, we conducted an a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.7. Based on effect sizes reported in prior trust-calibration research in automated driving [

9,

36], we specified a medium effect size (

f = 0.25),

α = 0.05, power (1 −

β) = 0.80, two groups (Initial-Trust: Low vs. High), and four repeated exposures (TOR1–TOR4). The analysis indicated a required minimum sample size of N = 24 to detect the Group × Exposure interaction which is our primary hypothesis regarding trust calibration trajectories. We recruited 26 participants to account for potential dropout or data exclusion due to technical issues. Then, twenty-six licensed, right-handed drivers (age: M = 23.0, SD = 1.85; 9 female) completed the study. All participants were undergraduate or graduate students with driving experience ranging from 1 to 5 years (M = 2.2, SD = 1.23). Participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological conditions. Participants received KRW 20,000 as compensation for their time; compensation was fixed and not contingent on performance. Written informed consent was provided by all participants. The Kwangwoon University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol (7001546-202300831-HR(SB)-008-01). Personally identifying information was stored separately from study data; analysis files contained only pseudonymized IDs and were kept on an encrypted, access-controlled server restricted to the research team, with retention and sharing aligned to IRB guidance.

3.2. Experimental Design

We used a within-subjects design with four takeover request (TOR) scenarios presented during conditional automated driving. To standardize exposure, scenarios were administered in a fixed order (A→B→C→D): (A) a disabled vehicle ahead, (B) a roadwork zone, (C) a highway interchange exit, and (D) a pedestrian jaywalking event.

3.3. Apparatus and Environment

The study was implemented in Unreal Engine (UE; version 5.1.1) using a fixed-base simulator with lane-keeping and speed control appropriate to an SAE level 3 context. The simulation was displayed on a 40-inch monitor with a 60 Hz refresh rate. Input was processed once per frame via the Enhanced Input system, yielding an effective sampling rate of 60 Hz. The driving simulator was equipped with a Thrustmaster Sparco R383 steering wheel and T-LCM pedals. Steering wheel angle (degrees), accelerator and brake pedal inputs (percentage), TOR event times, and other event timestamps were logged using UE’s high-resolution timer. A 10.4-inch tablet PC for the NDRT was mounted to the right side of the driver’s seat; to avoid systematic motor disadvantage in reaching movements, only right-handed participants were recruited. The complete driving simulator setup is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.4. Procedure

Each session lasted approximately 50 min. Upon arrival, participants provided written informed consent, completed a brief demographic questionnaire (age, gender, driving experience), and received a standardized briefing on the study flow and the capabilities/limits of conditional automation.

Participants next completed a 5-min practice block in the simulator to familiarize themselves with automated and manual driving as well as the NDRT. The practice included one TOR event so that drivers could experience the alerting sequence and the required takeover maneuver. During automated segments of the practice, participants rehearsed the NDRT. Immediately after practice, they completed the TOAST trust inventory; this post-practice score served as the initial trust.

The experimental drive then proceeded with the four TOR scenarios in the fixed order A→B→C→D. Prior to each TOR, participants were instructed to maximize their NDRT performance during automated control, and at the TOR they were instructed to resume manual control as quickly as possible. Immediately after each TOR, participants reported their current trust, and a short break was provided before the next scenario. After completing all four scenarios, participants took part in a brief post-session interview regarding their experience and perceptions of the system.

3.5. Tasks

During automated driving, participants oversaw the vehicle until a TOR occurred, indicated by combined visual and auditory cues (

Figure 2). At the moment of a TOR event, the interface displayed a visual icon derived from Yun et al. [

37] and simultaneously played a voice prompt in Korean indicating that autonomous driving mode was turning off. The NDRT followed the SuRT paradigm, developed using Flutter SDK 3.13.0. Stimulus parameters adhered to standard SuRT characteristics (e.g., target/distractor configuration, circle sizes/contrast, and trial window durations), and participants responded by touching targets on the tablet (

Figure 3). The prespecified primary performance metric was successful clicks per second, defined as the number of correctly identified targets per second of effective engagement time during automated driving.

3.6. Dependent Measures

We examined both self-reported trust and concurrent behavioral indices. Trust in automation was measured with the 9-item TOAST inventory [

33] on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). TOAST assesses three complementary facets: reliability (e.g., “The system is reliable”), understandability (e.g., “I understand how the system will assist me”), and dependability (e.g., “The system can be trusted to do its job”). The original validation study reported good internal consistency (α = 0.89; [

33]). A Korean version was developed via forward–back translation procedures. Participants completed TOAST after the practice block (initial trust) and after each of the four TOR scenarios. We computed per-exposure means across all 9 items to form an overall trust index. Higher scores indicate greater trust.

Behavioral outcomes comprised NDRT performance and TOR-RT. NDRT throughput was operationalized as successful SuRT clicks per second, defined as the number of correctly identified targets per second of effective engagement time during automated driving; misses and incorrect taps did not contribute to the numerator, and off-task intervals were excluded from the denominator. TOR-RT was defined as the latency from TOR onset to the first valid control input on any channel (steering, accelerator, or brake). All driving inputs, TOR events, and SuRT interactions were time-stamped (Unreal Engine 5.1.1 for driving data; tablet logs for SuRT) and synchronized to a common timeline via shared markers at block boundaries prior to analysis.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Jamovi (version 2.4.8; an open-source, R-based statistical platform). Prior to analysis, assumptions were evaluated using Shapiro–Wilk tests on model residuals for normality and Mauchly’s test for sphericity. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied when sphericity assumptions were violated. Primary models used mixed-design ANOVAs with a within-subjects factor reflecting repeated TOR exposure and a between-subjects factor of Trust Group (Low vs. High), defined via a median split of the post-practice TOAST score (treated as initial trust). Results are reported with F statistics, degrees of freedom,

p values, and partial η

2. Where relevant, Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparison followed significant effects. Additionally, we examined individual-level associations between trust and NDRT throughput using Pearson correlations. To assess the practical magnitude of observed differences beyond null hypothesis testing, we calculated 90% confidence intervals for paired mean differences in takeover reaction time. The 90% level was chosen to align with standards in equivalence research [

38] while providing interpretable bounds on effect magnitude. We evaluated these intervals against three benchmarks: (1) our observed variability, (2) between-study variability from meta-analytic literature [

39], and (3) safety margins derived from time budget requirements in Level-3 autonomous driving.

4. Results

4.1. Trust

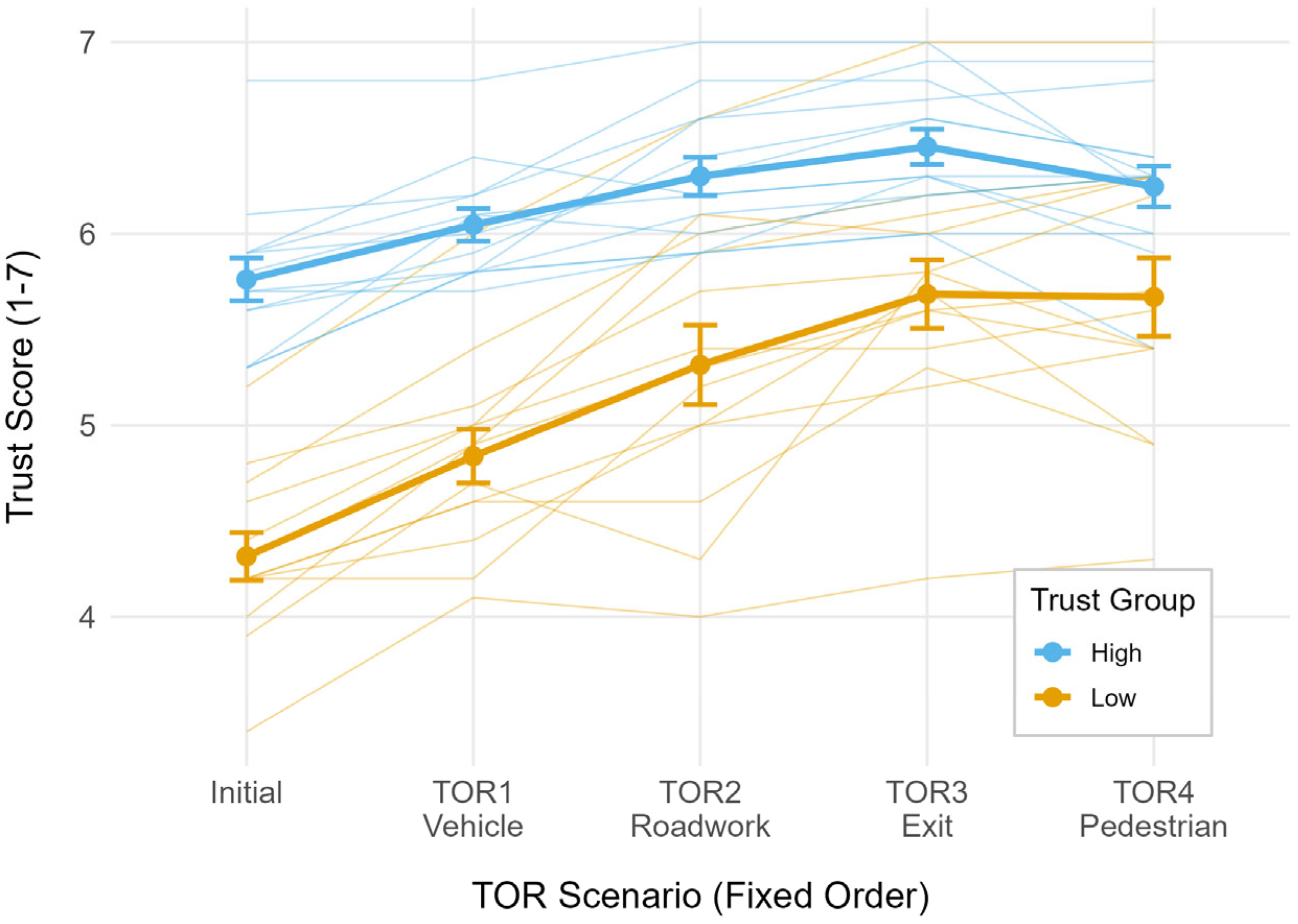

A mixed ANOVA with Exposure (Initial, TOR1–TOR4; within) and Group (Low vs. High initial trust; between, median split) revealed a significant Group × Exposure interaction F(4, 96) = 11.394,

p <0.001, η

2ₚ = 0.322. Given this interaction, we focus on simple effects rather than interpreting exposure’s main effect. In the Low group, trust increased significantly from initial to TOR1 (

ptukey < 0.001), from TOR1 to TOR2 (

ptukey < 0.01), and from TOR2 to TOR3 (

ptukey < 0.01), whereas changes from TOR3 to TOR4 were not significant (

ptukey = 1.00). In the High group, trust increased from initial to TOR1 (

ptukey < 0.05), whereas changes from TOR1 to TOR2 (

ptukey = 0.324), from TOR2 to TOR3 (

ptukey = 0.715), and from TOR3 to TOR4 were not significant (

ptukey = 0.398). The net gain through TOR3 was larger in the Low group (1.370) than in the High group (0.692), consistent with stronger calibration among initially low-trust participants. Trajectories are shown in

Figure 4.

4.2. NDRT Performance

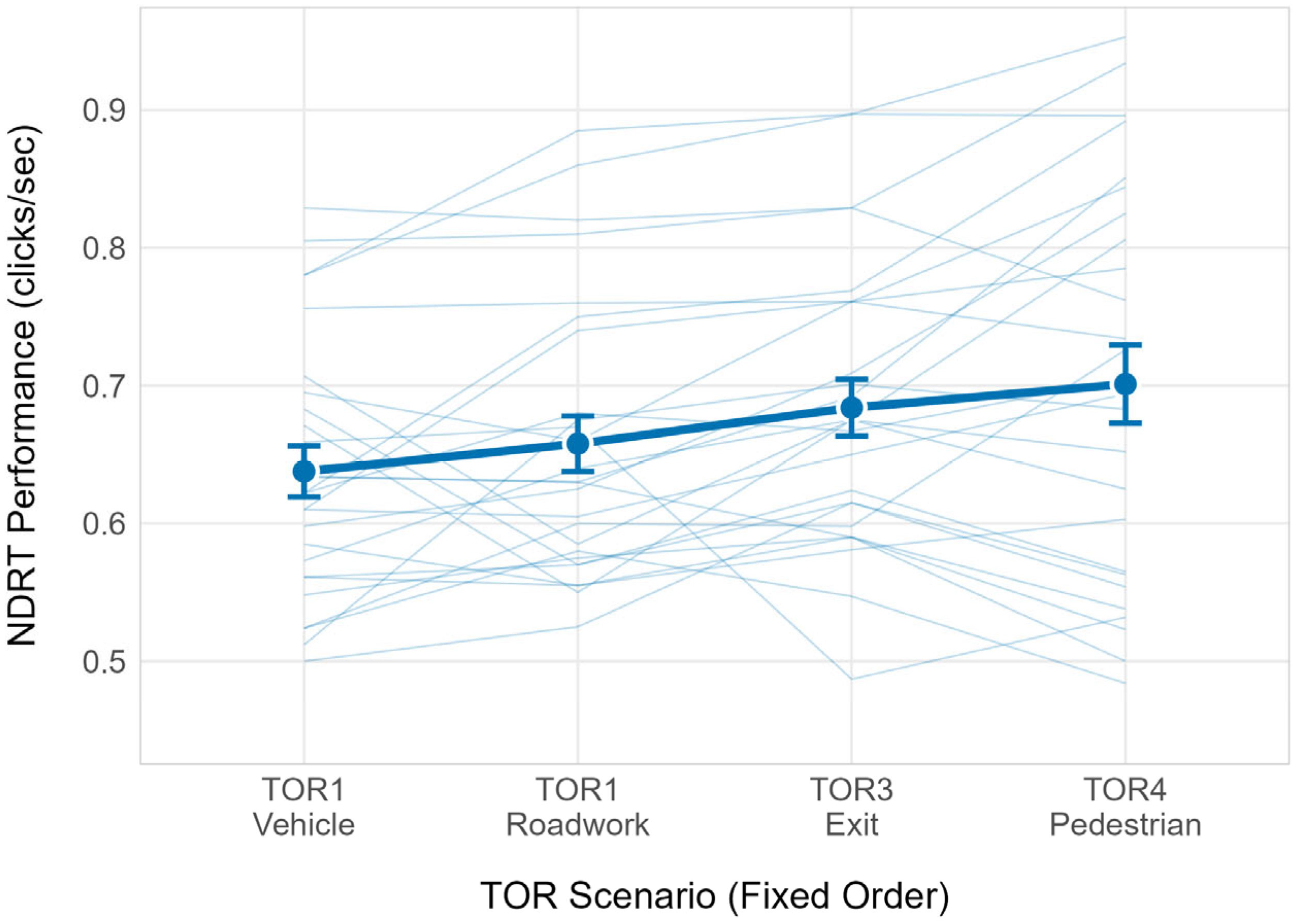

A mixed-design ANOVA with Exposure (TOR1–TOR4; within) and Group (Low vs. High; between) revealed a significant main effect of Exposure (Greenhouse–Geisser corrected), F(1.913, 45.905) = 5.434,

p < 0.01, η

2ₚ = 0.185, indicating that NDRT throughput changed across exposures (

Figure 5). The Exposure × Group interaction was not significant, F(1.913, 45.905) = 0.001,

p = 0.998, and the between-subjects Group effect was not significant, F(1, 24) = 2.531,

p = 0.125.

Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons (family-wise α = 0.05) showed that throughput was higher at TOR3 than TOR1 (Δ = +0.046 clicks/s, SE = 0.015, t(24) = 2.99, ptukey < 0.05). The TOR4 vs. TOR1 contrast trended in the same direction but did not reach significance (Δ = +0.063, SE = 0.024, t(24) = 2.626, ptukey = 0.066). All other adjacent or non-adjacent contrasts were non-significant after Tukey correction. Taken together, NDRT performance improved from early to mid-exposure (from TOR1 to TOR3) and then plateaued without reliable group differences across the session.

4.3. TOR Reaction Time

A mixed-design ANOVA on TOR-RT with Exposure (TOR1–TOR4; within) and Group (Low vs. High; between) showed no main effect of Exposure, F(3, 72) = 1.219, p = 0.309, and no Group × Exposure interaction, F(3, 72) = 1.316, p = 0.276. The between-subjects Group effect was also not significant, F(1, 24) = 0.110, p = 0.743. Thus, takeover latency remained statistically stable across repeated exposures and did not differ by initial-trust group.

5. Discussion

5.1. Trust Calibration and Trajectories

Across four takeover exposures, drivers’ trust increased rapidly after onboarding and early interactions and then leveled off, with a small, non-significant softening at the final exposure. This trajectory depended on initial disposition: participants who began with lower trust exhibited sustained gains through TOR3, whereas those who began with higher trust increased only from Initial to TOR1 and then stabilized. The significant Group × Exposure interaction is diagnostic of trust calibration: brief, structured experience narrows the initial uncertainty gap and aligns expectations with observed capability. This pattern accords with dynamic accounts of learned trust in human–automation interaction, in which a few predictable encounters are sufficient to reshape mental models. In short, low-trust drivers showed stepwise increases up to TOR3 before plateauing, whereas high-trust drivers displayed a small early increase only (Initial→TOR1) and then remained stable.

5.2. Productivity Gains and Takeover Readiness

As trust calibrated, NDRT throughput (SuRT successful clicks per second) improved from early to mid-exposure and then plateaued, with no significant differences between initial-trust groups. In parallel, TOR-RT showed no statistically significant changes across exposures or groups. These concurrent patterns speak to a fundamental question in conditional automation: whether increasing engagement in secondary tasks, enabled by rising trust, might delay safety-critical takeover responses.

Within the constraints of our design and sample, we did not observe evidence of such a speed–safety trade-off. Drivers became more effective at secondary tasks while maintaining statistically stable takeover latencies. However, interpreting this stability requires careful consideration of effect magnitude. The 90% confidence interval for our primary comparison (TOR4 vs. TOR1: [−0.213 s, 0.466 s]) reveals that while large systematic delays appear unlikely, moderate increases of up to approximately 0.5 s remain plausible given our data.

This upper bound merits contextualization across multiple benchmarks. Relative to meta-analytic standards (Zhang et al. [

39]: SD = 1.45 s), 0.466 s represents a small effect (32% of SD), and in operational terms constitutes only 7–12% of typical time budgets (4–7 s; Gold et al. [

40]) in Level-3 autonomous driving. However, against our within-study variation (SD = 0.743 s), it reflects moderate uncertainty (63% of SD). These complementary perspectives suggest that the maximum plausible difference may be negligible in scheduled takeovers with generous lead times, yet could become relevant in time-compressed scenarios. This also underscores limitations in definitively characterizing the true effect size given our sample constraints.

These findings neither demonstrate systematic performance impairment nor establish formal equivalence. Rather, they suggest that well-calibrated trust may support both secondary-task engagement and timely takeover responses within the conditions we tested (scheduled takeovers with moderate time pressure). The observed pattern aligns with Lee and See’s framework of appropriate reliance [

8], which posits that calibrated trust enables effective attention allocation between human and automation. Empirical work supports this interpretation: drivers with well-calibrated trust have been shown to engage more in secondary activities while maintaining or improving takeover preparedness [

18,

19].

However, the confidence interval width reflects inherent uncertainty given our sample size and design constraints. Future research employing larger samples, varied takeover urgencies, and comprehensive quality metrics beyond reaction time (e.g., trajectory stability, post-takeover situation awareness) would help establish more definitive boundaries on acceptable trust-performance trade-offs and narrow the plausible range of effects, particularly for time-critical scenarios where even moderate delays might become consequential.

5.3. Individual-Level Coupling of Trust and NDRT Throughput

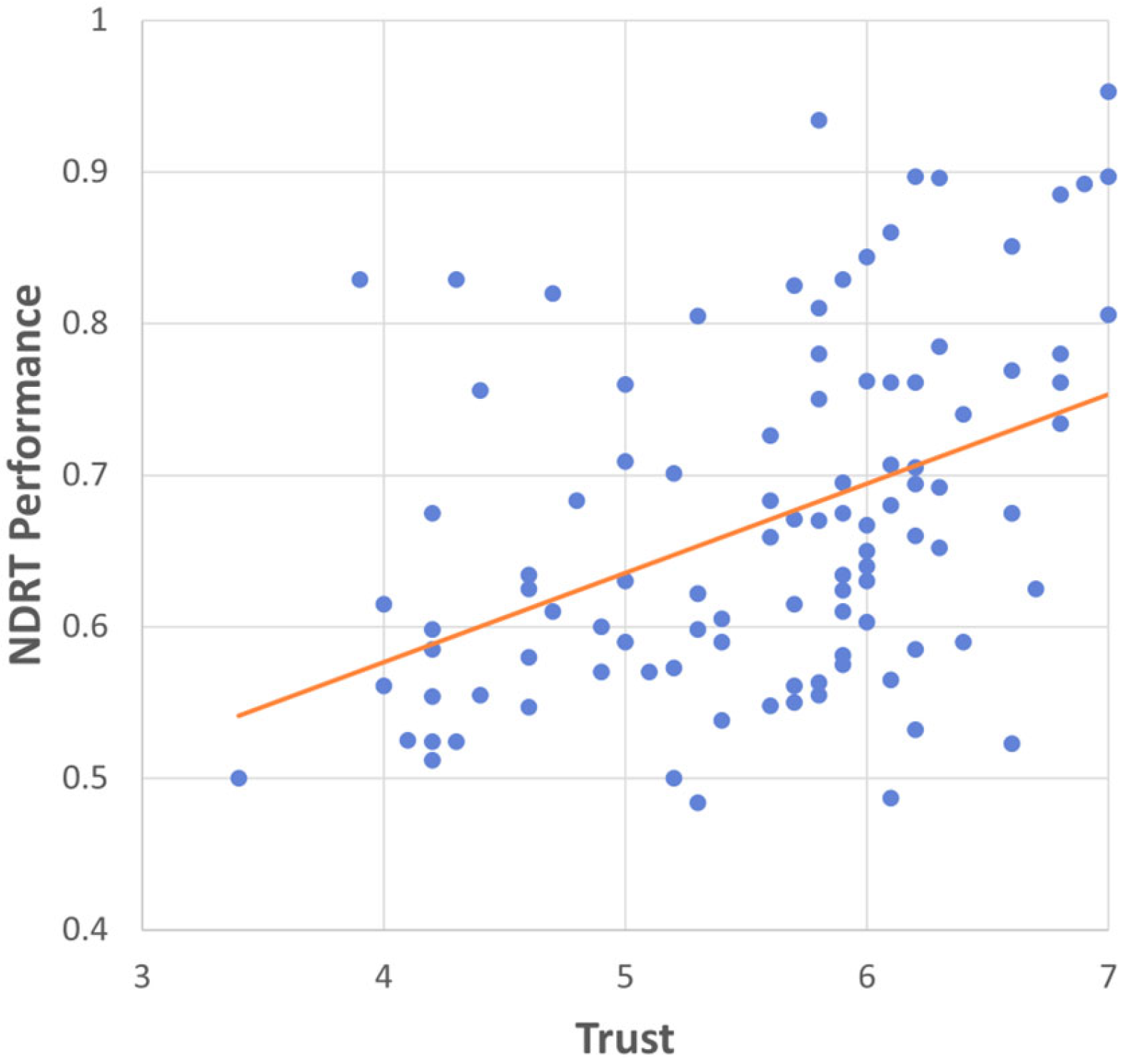

Beyond group trajectories, trust and concurrent secondary-task throughput were positively associated across individuals (Pearson’s r = 0.431,

p < 0.001,

Figure 6). Drivers who reported greater trust tended to achieve higher SuRT performance during automated segments. This is consistent with the view that calibrated trust enables more efficient attentional allocation—investing effort in the non-driving task when the system reliably handles routine control—without degrading readiness for TORs. The result converges with prior reports linking higher system trust to increased NDRT engagement (e.g., Petersen et al. [

16]) and is echoed in post-session interviews: several participants volunteered that, as their trust grew, they could “focus more on finding the target circles” (P3: “When trust was higher, I think I concentrated more on finding circles of different sizes”; P16: “As the experiment progressed, I gradually trusted the system more and could focus on finding circles of different sizes”). Correlation cannot determine directionality—greater trust may facilitate engagement, and successful engagement may, in turn, reinforce trust—but the convergence of self-report, behavior, and qualitative testimony strengthens the interpretation that calibrated trust is behaviorally expressed as higher throughput during conditional automation.

5.4. Interpreting the Softening at TOR4

Trust showed a small dip at TOR4, which involved a pedestrian. Human-involving hazards plausibly carry higher perceived severity and affective weight than purely vehicular conflicts. Under a “risk-as-feelings” lens, such events can transiently conservatize trust judgments even when objective capability is unchanged. We did not collect scenario-level ratings of perceived severity or affect, so this explanation is post hoc; nonetheless, it offers a coherent account of a mild trust retreat without a corresponding lengthening of TOR-RT. Future work should incorporate scenario-wise measures of perceived severity, affect/arousal, and workload and use counterbalanced orders to disentangle content from sequence effects.

5.5. Design and Training Implications

The concentration of trust gains within the first two exposures suggests that front-loaded micro-onboarding, consisting of brief hands-on demonstrations that make capability boundaries and TOR policies transparent, will be especially valuable before and during initial drives. This aligns with prior research demonstrating that initial system exposure and transparent communication of automation limitations significantly influence trust formation and calibration [

9,

18], particularly among users with lower baseline trust [

29]. We therefore recommend prioritizing early, structured exposure (e.g., warm-up TORs with clear performance feedback) for low-trust users. For high-trust users, our data show that additional exposures yield limited gains; research on automation complacency suggests risk-attuned cues and complacency-mitigating messaging may be more effective for this population [

41].

Trust-aware HMIs can exploit behavioral telemetry, such as unusually low NDRT throughput or excessive lane-monitoring micro-maneuvers, to infer under- or overtrust in situ and offer timely status information or gentle attention prompts to keep reliance aligned with capability. This approach builds on established frameworks for adaptive automation that adjust system behavior based on operator state [

42] and recent work demonstrating the feasibility of real-time trust inference from behavioral and physiological signals in automated driving [

43,

44]. For human-involving hazards such as pedestrians or cyclists, modest anticipatory cues (earlier iconography or subtle pre-alerts) may preserve predictability and prevent undue trust dips while safeguarding fast takeovers.

5.6. Theoretical Contributions

The study moves beyond static attitudes by analyzing self-reported trust alongside concurrent behavior (NDRT throughput and TOR-RT), showing that calibrated trust has observable behavioral signatures. It also clarifies heterogeneity in learning: initial trust not only shifts the level but shapes short-run trajectories, implying that trust calibration unfolds at different rates across users. This heterogeneity is actionable for personalization in conditional automation.

5.7. Limitations and Future Directions

Several methodological constraints warrant consideration when interpreting these findings. The fixed scenario order partially confounds content effects with sequential or fatigue-related influences. For instance, the trust pattern observed during the pedestrian encounter (TOR4) may reflect scenario-specific characteristics, accumulated exposure effects, or both. Counterbalanced designs with randomized event timing and mixed-effects models incorporating scenario-level covariates such as perceived severity and workload would better isolate these influences in future work.

The behavioral assessment focused on TOR-RT as the primary safety indicator. While RT provides insight into takeover timeliness, it does not capture maneuver quality or control stability. More comprehensive evaluations could incorporate additional metrics including braking characteristics, steering smoothness, trajectory deviation, time-to-collision, and lane-keeping performance during the post-takeover period. Integrating these measures with eye-tracking, psychophysiological signals, and scenario-specific ratings would enable more nuanced assessments of the relationships among trust, attentional allocation, and safety outcomes.

The sample comprised primarily young student drivers tested in a fixed-base Level-3 simulator, which limits generalizability. The findings apply most directly to this demographic profile under the specific onboarding procedures and NDRT conditions employed here. Extensions to drivers of varying ages, experience levels, and cultural backgrounds, as well as to different automation capabilities, NDRT types, and real-world driving environments, require empirical validation. Larger and more diverse samples tested across multiple contexts would strengthen external validity.

Finally, while our analysis did not detect systematic increases in TOR-RT across exposures, the confidence intervals reflect residual uncertainty in estimating effect magnitudes. The observed interval bounds suggest that moderate differences cannot be definitively ruled out, particularly in scenarios with compressed time budgets. Future research employing pre-registered analysis plans, larger samples, and expanded outcome measures would help refine understanding of the conditions under which trust–productivity gains can be achieved without compromising takeover performance. Higher-fidelity simulation and on-road validation studies would further clarify the ecological robustness of these patterns.

6. Conclusions

This study characterizes driver trust as a calibrated, experience-dependent state situated between overtrust and distrust. Brief, structured interaction with conditional automation can calibrate driver trust quickly, especially among initially low-trust users. In this calibrated state, drivers gain secondary-task productivity (higher NDRT throughput) without detectable slowing in takeover reaction time, and trust correlates positively with concurrent NDRT throughput—consistent with more effective attentional allocation during routine automation.

Practically, systems should emphasize front-loaded micro-onboarding that makes capability boundaries and TOR policies transparent, and employ trust-aware interfaces that read behavioral signals to keep reliance aligned with actual performance. For human-involving hazards (e.g., pedestrians), modest anticipatory cues that preserve predictability may prevent transient trust dips while safeguarding rapid takeovers.

Overall, the results suggest that calibrated trust may support key goals of conditional automation: enabling drivers to engage productively in secondary tasks while maintaining readiness for takeover transitions. These findings emerged under specific conditions (scheduled takeovers with 4–7 s lead times and moderate urgency), and future research should examine whether similar patterns hold across varied takeover demands, time budgets, and traffic complexities to establish comprehensive design guidelines for trust-aware automation systems.