Abstract

The rapid growth of robotic warehouses and smart logistics has increased the demand for efficient scheduling of multi-tier shuttle systems (MTSSs). MTSS scheduling is a complex robotic task allocation problem, where throughput, energy efficiency, and service quality must be jointly optimized under operational constraints. To address this challenge, this study proposes a hybrid optimization framework that integrates the Minimum-Cost Maximum-Flow (MCMF) algorithm with the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II). The MTSS is modeled as a cyber–physical robotic system that explicitly incorporates task flow, energy flow, and information flow. The lower-layer MCMF ensures efficient and feasible task–robot assignments under state-of-charge (SOC) and deadline constraints, while the upper-layer NSGA-II adaptively tunes cost-function weights to explore Pareto-optimal trade-offs among makespan, energy consumption, and waiting time. Simulation results show that the hybrid framework outperforms baseline heuristics and static optimization methods and reduces makespan by up to 5%, the energy consumption by 2.8%, and the SOC violations by over 90% while generating diverse Pareto fronts that enable flexible throughput-oriented, service-oriented, or energy-conservative scheduling strategies. The proposed framework thus provides a practical and scalable solution for energy-aware robotic scheduling in automated warehouses, thus bridging the gap between exact assignment methods and adaptive multi-objective optimization approaches.

1. Introduction

The growing complexity of logistics and warehousing in the era of Industry 4.0 has placed unprecedented emphasis on robotic automation and intelligent scheduling. Modern warehouse environments increasingly rely on fleets of autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) or shuttles to execute storage and retrieval tasks in high-density, multi-tier layouts. These robotic warehouses demand rapid order fulfillment, high storage density, and energy-efficient operations, which directly affect throughput, service quality, and operational costs [1,2].

At the core of these systems lies the task allocation problem, a fundamental challenge in robotics and logistics research, which involves assigning a set of tasks to available agents while considering operational constraints and system objectives [3]. In multi-tier shuttle systems (MTSSs), a representative form of automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS), task allocation is particularly complex due to the interaction between multiple autonomous shuttles, tiered storage infrastructure, and dynamic task arrival patterns [4]. Unlike conventional stacker-crane systems with rigid aisle structures, MTSSs deploy autonomous shuttles across tiers to perform inbound, outbound, and transfer operations with increased flexibility and efficiency [5].

As in many complex logistics environments, multi-objective trade-offs are inherent in MTSS scheduling. Traditional single-objective policies—such as minimizing makespan or travel distance—often fail to capture the essential conflicts among throughput, energy consumption, and task waiting times. Real-world decision-makers must balance competing goals: reducing completion time to increase throughput, conserving energy to extend battery life and reduce operational costs, and minimizing waiting time to maintain service-level agreements [6].

Energy-aware operation is particularly critical in MTSSs, as each shuttle is battery-powered and charging behavior directly impacts operational continuity. Schedules that ignore state-of-charge (SOC) dynamics and charging constraints can result in frequent task interruptions, infeasible assignments, and reduced throughput [7]. Effective scheduling therefore requires SOC-aware mechanisms that prevent unsafe battery depletion while avoiding overly conservative recharging policies that reduce system utilization.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a hybrid two-layer framework that integrates Minimum-Cost Maximum-Flow (MCMF) for feasible task assignment with Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) for adaptive multi-objective exploration. In this framework, the MCMF layer enforces assignment feasibility, capacity, and SOC-related constraints, while the NSGA-II layer adaptively searches the weight and threshold parameter space to identify Pareto-optimal trade-offs among makespan, energy consumption, and task waiting time. By combining exact feasibility ensured by MCMF with the adaptive multi-objective search capability of NSGA-II, the proposed approach offers warehouse operators a diverse and implementable set of scheduling strategies that can be tailored to different operational priorities.

Contributions. This paper makes the following contributions:

We propose a hybrid MCMF–NSGA-II framework that couples exact assignment with multi-objective evolutionary search to jointly optimize makespan, energy consumption, and total waiting time.

We introduce an SOC-aware MCMF formulation that enforces battery constraints within the flow model, effectively reducing SOC violations.

We provide a comprehensive experimental evaluation, covering multiple problem sizes and runtime measures, demonstrating improved Pareto diversity and energy reliability.

We discuss practical implications for MTSS operators and outline potential extensions for online and stochastic scheduling scenarios.

Paper Organization. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work and positions our contribution. Section 3 formalizes the MTSS scheduling problem and objective definitions. Section 4 describes the MCMF–NSGA-II hybrid framework and algorithmic workflow. Section 5 presents experimental setup, quantitative comparisons, and discussion. Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

Task scheduling in automated logistics systems, such as MTSSs, is a multi-objective process optimization problem requiring the joint consideration of throughput, energy efficiency, and service responsiveness. Existing research on this problem can be broadly systematized into three main methodological categories: metaheuristic approaches, exact algorithms, and reinforcement learning (RL)-based methods. Each category exhibits distinct characteristics, applicability scopes, and limitations concerning problem complexity, optimality guarantees, and adaptability.

2.1. Metaheuristic Approaches

Metaheuristic algorithms, inspired by natural or social processes, are prevalent for solving complex NP-hard scheduling problems where exact methods become intractable [6]. Their primary scope is to find near-optimal solutions with reasonable computational effort. Notable algorithms include:

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and NSGA-II: GAs have been combined with greedy strategies to enhance global search capability [7,8,9]. Among them, NSGA-II, with its elitist non-dominated sorting and crowding distance mechanism, has become a benchmark for multi-objective scheduling [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. It has been widely applied to optimize completion time, energy consumption, and workload balance simultaneously in flexible job shop and logistics scheduling. However, NSGA-II’s proposal often suffers from sensitivity to parameter settings and risks of premature convergence in highly complex scenarios.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): PSO and its distributed variants have been adopted to improve scheduling efficiency in intelligent logistics systems [17,18]. Multi-Objective PSO (MOPSO) is also applied [19], but like NSGA-II, it requires careful parameter tuning and may stagnate under specific process constraints.

Ant Colony Optimization (ACO): ACO has been utilized for multi-robot task allocation, with improved pheromone mechanisms proposed to enhance solution stability [20]. Multi-Objective ACO (MOACO) faces similar challenges regarding parameter sensitivity [21].

The key distinction of our article’s proposal from these metaheuristic approaches lies in explicitly integrating energy-aware resource assignment logic within the evolutionary search process to directly address State-of-Charge (SOC) constraints, an aspect often handled indirectly or post hoc in standard metaheuristics.

2.2. Exact Algorithms for Resource–Task Assignment

Exact algorithms guarantee global optimality for deterministic, often simplified, subproblems within the broader scheduling context. Their scope is typically limited to problems of moderate size or specific structures due to exponential worst-case complexity for NP-hard problems. A prominent exact method is:

Minimum-Cost Maximum-Flow (MCMF): The MCMF algorithm, a classical network-flow optimization method, has been successfully applied in domains like unmanned aerial vehicle scheduling and multi-robot allocation [22,23]. Its proposal is efficient, polynomial-time solvability for static task assignment problems, making it suitable for process-level resource allocation where optimality in flow and cost is critical. However, MCMF’s scope is limited in dynamic environments as it lacks inherent adaptability and requires re-solving for every change.

Our work differentiates itself by leveraging MCMF not in isolation but as a foundational component integrated within a larger metaheuristic framework for efficient resource-task matching within a larger metaheuristic framework, thus mitigating its drawback in dynamic adaptability while preserving its local optimality benefits for the assignment subproblem.

2.3. Reinforcement Learning-Based Scheduling

Reinforcement learning provides a paradigm for adaptive scheduling in dynamic logistics environments. The scope of RL-based methods is to learn scheduling policies directly from interaction with the environment, offering potential for high adaptability. Studies have demonstrated RL’s application in optimizing material-handling processes [24], enhancing multi-objective optimization when hybridized with NSGA-II [25], and improving adaptive operator selection [26]. However, the maturity of RL for multi-objective process optimization is still limited compared to metaheuristics. Its proposal often demands large amounts of training data, careful reward function design, and suffers from stability and generalization challenges.

This article’s proposal differs from pure RL approaches by employing a hybrid model-based (MCMF) and metaheuristic (NSGA-II) strategy, which does not rely on extensive pre-training and offers more interpretable and computationally tractable optimization for the targeted MTSS process.

2.4. Research Gap and Our Contribution

In summary, metaheuristics like NSGA-II offer flexibility for multi-objective optimization but may lack efficient mechanisms for hard resource and energy constraints like SOC. Exact algorithms like MCMF ensure optimality in static assignment but lack dynamism. RL enhances adaptability but is data-intensive and less mature. For MTSS process optimization, a significant gap exists in methodologies that can explicitly and efficiently integrate dynamic energy management (e.g., SOC) with multi-objective scheduling for throughput and service quality in a scalable manner.

These limitations collectively motivate our proposal of a hybrid MCMF–NSGA-II framework. This framework aims to bridge this gap by systematically combining the global search capability of NSGA-II with the efficient, energy-aware resource allocation provided by MCMF. Our approach distinctly differs from previous work by its core integrative mechanism, which directly embeds SOC-conscious assignment within the evolutionary multi-objective search process, achieving a balance between throughput, energy consumption, and service quality that existing standalone methods struggle to attain.

3. Materials and Methods

To investigate the scheduling and energy management of the multi-tier shuttle system (MTSS), this section first introduces the system from a robotic perspective, detailing its operational components, flows, and assumptions. Subsequently, we define the optimization objectives and constraints that guide task allocation, sequencing, and energy-aware operation. This structured approach provides a foundation for the hybrid MCMF–NSGA-II framework described later.

3.1. Robotic Description of the Multi-Tier Shuttle System

To formally describe the MTSS and its operational context from a robotic scheduling perspective, this study considers a single-deep multi-tier shuttle system integrating three essential flows—task, energy, and information—which together define shuttle behavior, task execution, and scheduling decisions:

1. Task flow (material flow): storage and retrieval requests that must be executed within specified due dates;

2. Energy flow: shuttle battery consumption and charging, governed by state-of-charge (SOC) dynamics;

3. Information flow: scheduling decisions that assign tasks to shuttles and determine their execution sequences.

The MTSS operates under the following assumptions:

- The system comprises multiple storage tiers, each served by a fleet of autonomous shuttles.

- Shuttles begin with an initial SOC and consume energy at different rates depending on whether they are loaded or unloaded. When SOC falls below a predefined threshold, the shuttle must proceed to a charging station.

- Tasks are pre-assigned to tiers, with scheduling focused on both intra-tier and inter-tier operations. Lift–shuttle interactions are simplified for tractability.

- All shuttles are assumed to have identical performance characteristics and move at a nominal constant velocity of 1 m/s, neglecting acceleration and deceleration phases.

- The task set is static, with complete information (task type, location, due date) available before execution.

This formulation emphasizes the MTSS as a cyber–physical robotic system, where scheduling decisions influence throughput, energy utilization, and service quality simultaneously.

3.2. Optimization Objectives

Having defined the system, we now specify the formal optimization objectives that guide shuttle task allocation and sequencing. These objectives capture three critical aspects of MTSS performance: throughput efficiency, energy efficiency, and service responsiveness.

Let denote the set of tasks and the set of shuttles. The objective is to determine an allocation and execution sequence that simultaneously optimizes the following three criteria:

- Makespan (throughput efficiency)where is the completion time of task .

- Total Energy Consumption (energy efficiency)where denotes the total energy consumed by shuttle , primarily for travel.

- Total Waiting Time (service responsiveness)where is the start time of task and its release time.

3.3. Constraints

To ensure feasible and practical scheduling, shuttle assignments and energy operations must satisfy a set of constraints. The following subsections detail the task assignment rules and battery-related limitations.

3.3.1. Task–Shuttle Assignment

- Each task must be executed exactly once.

- Each task must be completed before its deadline; otherwise, a penalty is incurred.

- Each shuttle can execute only one task at a time.

3.3.2. Battery and Charging Constraints

For any shuttle , the SOC at any time must satisfy:

where is the minimum allowable SOC to prevent deep discharge.

When , the system issues a charging command, interrupting the current task if necessary.

The energy-consumption model assumes the following:

- Unloaded travel energy rate: (SOC per meter).

- Loaded travel energy rate: (SOC per meter).

For a shuttle traveling unloaded from position to task pickup point , then loaded to delivery point , the total SOC consumption is:

where is the travel distance.

4. Proposed MCMF–NSGA-II Hybrid Optimization Framework

To address the multi-objective robotic scheduling problem in MTSS, this study proposes a two-layer hybrid optimization framework that integrates the global exploration capability of NSGA-II with the precise task allocation efficiency of the MCMF algorithm. The framework is designed not only as an algorithmic innovation but also as a decision-support mechanism for robotic warehouse scheduling, where throughput, energy efficiency, and service quality must be jointly optimized.

4.1. Framework Overview

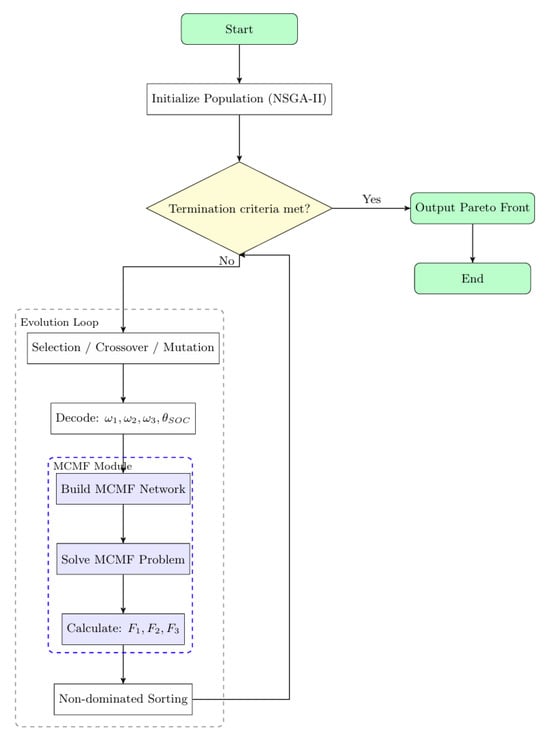

The framework consists of two complementary layers (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the proposed MCMF–NSGA-II hybrid algorithm.

- Upper Layer (NSGA-II): Performs global search over decision variables, including the weights in the MCMF cost function and SOC charging thresholds. This layer explores diverse trade-offs among throughput, energy, and responsiveness, yielding a Pareto-optimal set of robotic scheduling strategies [17,18,19].

- Lower Layer (MCMF): For each parameter set generated by NSGA-II, MCMF computes optimal task–shuttle assignments in polynomial time [22,23]. This ensures efficient handling of large-scale static task batches while respecting SOC and task constraints.

From a process perspective, the upper layer balances multiple robotic scheduling objectives, while the lower layer guarantees that each assignment adheres to material flow continuity, energy constraints, and service deadlines.

4.2. MCMF Model for Task Assignment

We formulate the task assignment problem as a network flow model , where is the set of nodes and the set of directed edges.

- Source node: task pool (representing all pending jobs).

- Task nodes: each corresponds to a specific storage/retrieval task.

- Shuttle nodes: represent available shuttles.

- Sink node: represents completed tasks.

An edge from task node to shuttle node has:

Capacity: three tasks per shuttle in a given cycle.

Cost:

where

: Normalized travel distance for shuttle to execute task .

: Normalized task priority, determined by a comprehensive weighting of multiple indicators such as task distance, waiting time, and customer value. A lower priority value indicates higher task importance and thus earlier execution.

: Normalized task urgency. Defined as the difference between the task deadline and the current time.

: Normalized SOC of shuttle .

: Penalty incurred if the SOC constraint is violated (i.e., ).

, , : Adaptive weights, determined by NSGA-II.

Solving MCMF yields the assignment minimizing total weighted cost while satisfying flow conservation and capacity constraints.

4.3. NSGA-II Parameter Optimization

In the upper layer, NSGA-II considers the MCMF weights and SOC charging threshold as decision variables.

Chromosome encoding:

with constraints:

Fitness evaluation: For each chromosome, the MCMF model computes the corresponding task assignment. Objective values are returned to NSGA-II for non-dominated sorting and crowding distance calculation.

Non-dominated sorting:

For a minimization problem, solution dominates if

Solutions not dominated by any other are assigned to Front 1, those dominated only by Front-1 solutions to Front 2, and so on.

Crowding distance:

Within each front, for objective , sort solutions by . The crowding distance of solution is the sum of normalized neighbor gaps:

with boundary solutions assigned to preserve extreme points.

Evolution operators:

- Selection: Binary tournament based on Pareto rank and crowding distance.

- Crossover: Simulated binary crossover (SBX) with probability .

- Mutation: Polynomial mutation with probability .

Termination: The algorithm stops after generations or when improvement in Pareto front quality falls below a threshold.

4.4. Algorithm Workflow

Step 1: Initialize the NSGA-II population with randomly generated feasible weight–threshold combinations.

Step 2: For each individual, call MCMF to compute optimal task allocation and obtain objective values.

Step 3: Perform non-dominated sorting and crowding distance computation.

Step 4: Apply selection, crossover, and mutation to generate offspring.

Step 5: Merge parent and offspring populations, sort, and select the best individuals for the next generation.

Step 6: Repeat Steps 2–5 until the termination condition is satisfied.

Step 7: Output the final set of Pareto-optimal solutions for decision-making.

Process perspective: As shown in Algorithm 1, this workflow integrates decision-making (upper layer) and process execution feasibility (lower layer), ensuring that the final solutions are both optimal in trade-offs and implementable in practical warehousing operations.

| Algorithm 1: MCMF-NSGA-II Hybrid Optimization for Multi-Tier Shuttle System. | |

| Input: Task set , Suttle set , max generations , population size N | |

| Output: Pareto-optimal set of chromosomes | |

| 1 | Setp 1: Initialize population; |

| 2 | for to N do |

| 3 | Chromosome initialization: sample weights with , and SOC threshold ; |

| 4 | Chromosome ; |

| 5 | Evaluate objectives by calling MCMF with |

| 6 | Perform non-dominated sorting sorting and calculate crowding distance; |

| 7 | for to do |

| 8 | Step 2: Selection; |

| 9 | Use binary tournament based on rank and crowding distance to select parents; |

| 10 | Step 3: Crossover and Mutation; |

| 11 | for each pair of parents do |

| 12 | Perform simulated binary crossover (SBX) to generate child ; |

| 13 | Apply polynomial mutation to ; |

| 14 | Step 4: Evaluate Offspring; |

| 15 | for each offspring |

| 16 | Evaluate objectives via MCMF; |

| 17 | Step 5: Combine and Sort; |

| 18 | Combine parent and offsping populations; |

| 19 | Perform non-dominated sorting and crowding distance calculation; |

| 20 | Select best N individuals for the next generation; |

| 21 | Step 6: Update Global Pareto Set; |

| 22 | Store Rank-1 solutions of this generation |

| 23 | Step 7: Output; |

| 24 | Return final Pareto-optimal set of chromosomes |

5. Experiments and Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MCMF–NSGA-II framework, this section presents a comprehensive experimental study. The experiments are designed to validate the algorithm’s performance in terms of scheduling efficiency, energy management, and service responsiveness under realistic MTSS settings. We first describe the simulation environment, system parameters, and baseline strategies used for comparison. Next, quantitative results and Pareto-front analyses are provided to illustrate the trade-offs among makespan, energy consumption, and waiting time. Finally, we discuss the implications of the results and outline potential extensions to dynamic and online scheduling scenarios.

5.1. Experimental Setup

The hybrid framework was implemented in C# and executed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9-13900H CPU and 32 GB RAM. The MTSS simulation environment supports static task batches, where all task attributes are known prior to scheduling. The experimental parameters are summarized as follows:

- System scale: 3 storage tiers, 100 autonomous shuttles, overall structure similar to Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of Multi-tier shuttle systems.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of Multi-tier shuttle systems. - Task set: 300 storage/retrieval tasks, with arrival times generated according to a normal distribution and due dates assigned 60–120 s after task generation.

- Shuttle travel speed: 1 m/s (both loaded and unloaded).

- Energy rates: SOC/m when unloaded; SOC/m when loaded.

- Battery capacity: The initial charge (SOC) is evenly distributed between 50% and 100%, with a maximum charge of 100% and minimum SOC threshold .

- Algorithm parameters: NSGA-II population size = 30, crossover probability , mutation probability , maximum generations = 50.

Baseline methods for comparison:

To verify the superiority of the proposed MCMF–NSGA-II algorithm, three comparative strategies are designed:

- Greedy-FCFS: A baseline strategy without global optimization, which follows the First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) principle combined with the nearest-vehicle-first rule for task assignment.

- Static-MCMF: A single-objective optimization strategy that applies the MCMF model for task allocation, considering only the distance factor. This represents the upper bound of performance under static weight settings.

- MCMF–NSGA-II: The proposed hybrid algorithm, which dynamically optimizes the cost weights of the MCMF model using NSGA-II to achieve multi-objective collaborative optimization.

Performance metrics:

To comprehensively quantify the performance of the scheduling scheme, the following three core metrics are used:

Makespan : Maximum completion time, defined as the maximum value of all task completion times;

Total energy consumption : Total distance consumption, the total distance traveled by all shuttles during task execution and movement;

Total waiting time : Total task waiting time, reflecting the delay from task release to execution start;

SOC violation count (number of times ).

5.2. Quantitative Comparison

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the proposed MCMF–NSGA-II framework, we compared it against two baseline algorithms—Greedy-FCFS and Static-MCMF—under identical task configurations. Each algorithm was executed 30 times, and the mean and standard deviation of the results are summarized in Table 1. Statistical significance was assessed using paired t-tests at a significance level of α = 0.05, with p-values reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of scheduling algorithms.

Table 2.

Statistical significance (p-values) of performance differences between MCMF–NSGA-II and baseline algorithms (paired t-test, α = 0.05).

The results demonstrate that the proposed MCMF–NSGA-II framework consistently outperforms both baseline methods across scheduling efficiency, energy management, and service quality.

In terms of scheduling efficiency, the makespan was reduced by 5.0% compared with Greedy-FCFS and 1.3% compared with Static-MCMF. Moreover, the variance of makespan was notably lower, which reflects improved robustness to task heterogeneity. This indicates that the hybrid approach not only accelerates task completion but also maintains stable performance under diverse workload conditions, a crucial property for real-world warehouse operations where task sizes and deadlines vary dynamically.

In terms of energy consumption, MCMF–NSGA-II achieved the lowest overall values while drastically reducing SOC violations (0.17 per cycle, compared to more than two for the baselines). This demonstrates the effectiveness of explicitly embedding energy-flow constraints into the scheduling process, ensuring battery safety and minimizing charging interruptions. By avoiding both over-conservative recharging and risky deep discharges, the algorithm achieves a sustainable balance between throughput and energy usage.

In terms of service quality, the hybrid framework shortened waiting times and reduced overdue tasks, showing that the algorithm is capable of adaptive prioritization of urgent tasks without compromising overall system efficiency. This balance is particularly important in order-driven warehouses, where late deliveries directly impact customer satisfaction.

A key advantage of the proposed framework lies in its ability to balance multiple objectives simultaneously. While Greedy-FCFS lacks global optimization capability and Static-MCMF is restricted to a single fixed objective, MCMF–NSGA-II generates a diverse set of Pareto-optimal solutions. This enables decision-makers to flexibly adopt different scheduling strategies based on operational conditions—for example, prioritizing throughput during peak demand, or conserving energy during off-peak hours. From a process optimization perspective, this flexibility represents a significant improvement over traditional single-objective or heuristic approaches, as it explicitly captures the trade-offs between material flow, energy flow, and service responsiveness.

5.3. Pareto Front Analysis

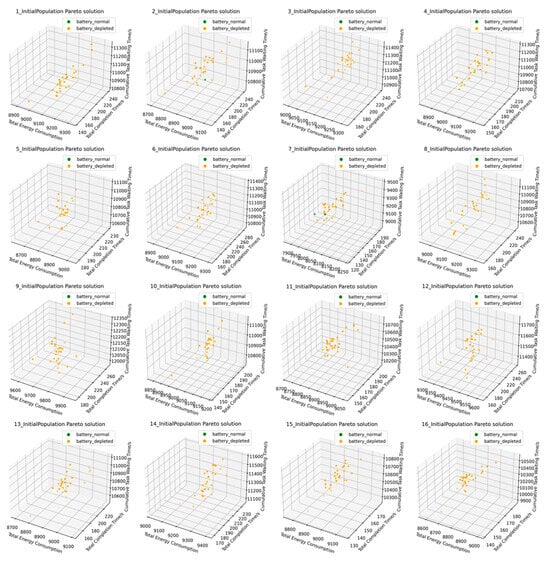

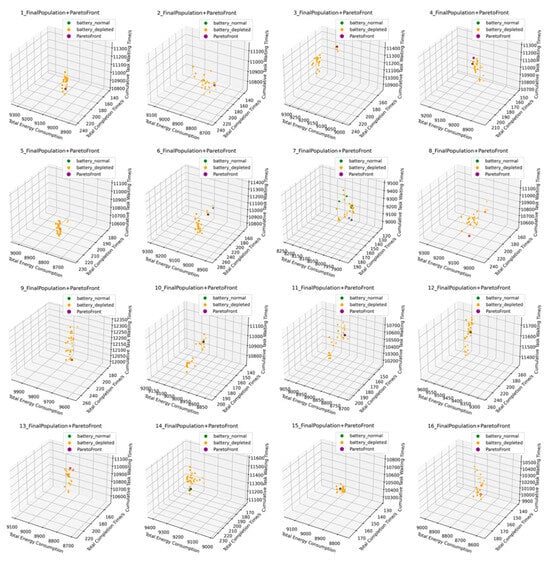

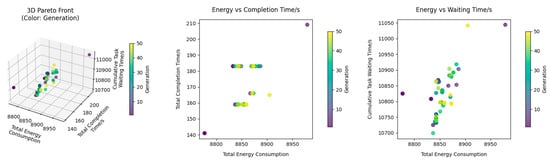

To further demonstrate the trade-off capability of the proposed scheduling strategy, the Pareto-optimal solution sets generated in multiple simulation runs are analyzed. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the solutions exhibit a well-structured and evenly distributed Pareto front.

Figure 3.

Initial population distribution (partial).

Figure 4.

Final population and Pareto distribution.

Figure 5 visually captures the evolutionary trajectory of the Pareto-optimal solution set across generations. It clearly shows how the population, starting from a scattered initial distribution, progressively converges towards the final Pareto front while maintaining a diverse spread of solutions. This demonstrates the effective balance between exploration and exploitation achieved by the hybrid algorithm throughout the optimization process.

Figure 5.

Evolutionary trajectory of the Pareto-optimal set.

As an illustrative example, a single Pareto solution experiment is considered. The final population (Table 3) demonstrates a structured Pareto front covering wide ranges of performance: makespan from 159–203 s, energy (travel distance) from 8837–8955 m, and waiting time from 10,720–11,100 s. Four main insights can be drawn:

Table 3.

Final population of 30 groups of solution parameters and their fitness.

1. Objective Conflicts and Layered Performance

Solutions with low makespan (e.g., set(1, 3, 10, 13, 23), all with ) simultaneously achieve reduced travel distance and shorter delays . In contrast, high-makespan solutions (e.g., set(19, 21), ) show significantly higher travel distance and delays, confirming the inherent conflicts among objectives.

2. Diversity and Distribution

The Pareto set spans a broad solution space but clusters around efficient regions , reflecting industrial priorities for rapid completion while still allowing moderate trade-offs. This distribution indicates that the algorithm not only finds extreme solutions but also maintains diversity across balanced configurations.

3. Impact of Adaptive Weights

The mapping between weight parameters and objective values demonstrates the effectiveness of adaptive optimization.

- Solutions with high task-priority weights dominate the low-makespan region, showing that emphasizing urgency accelerates completion without sacrificing energy.

- Higher urgency weights (, e.g., set(24, 26, 29)) correspond to shorter delays, proving the effectiveness of urgency-aware scheduling.

- Energy-focused solutions (, e.g., set(17, 19, 21)) successfully eliminate SOC violations but incur longer makespans, thereby illustrating the trade-off between operational efficiency and energy reliability.

4. Decision-Making Flexibility

The Pareto front provides a spectrum of feasible solutions. Decision-makers can emphasize efficiency, service quality, or energy reliability depending on real-time operational requirements. For example, during high throughput demand, low-makespan solutions (e.g., set(1, 3)) are preferable, while in energy-sensitive scenarios, SOC-safe solutions (e.g., set(19, 21)) become optimal.

5.4. Computational Efficiency and Configuration Scalability

The computational efficiency of a scheduling algorithm is a critical factor for its practical deployment. While the proposed hybrid MCMF–NSGA-II framework aims to find high-quality Pareto-optimal solutions, it incurs a higher computational cost compared to the baseline methods. For context, a single execution of the Static-MCMF algorithm under the baseline configuration (3 tiers, 100 shuttles, 300 tasks) requires approximately 0.1 s, whereas the Greedy-FCFS heuristic is exceptionally fast, averaging about 60 milliseconds.

To analyze the trade-off between computational cost and solution quality for the hybrid framework, we conducted experiments with different NSGA-II configurations by varying the population size and the maximum number of generations. The performance metrics and the average total computation time for each configuration are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Performance and computation time comparison under different problem scales.

The results in Table 4 reveal a clear trade-off between computational time and scheduling performance, while also highlighting the sensitivity of the hybrid MCMF–NSGA-II framework to parameter settings. Overall, as the computational budget (determined by population size × number of generations) increases, solution quality generally improves across all objectives, including makespan, energy consumption, waiting time, and SOC violations. However, this improvement comes at the cost of increased computation time, indicating a tunable balance between algorithm performance and resource consumption in multi-objective optimization.

Impact of Generations: For a fixed population size of 30, increasing the number of generations from 10 to 50 reduces makespan from 178.24 s to 174.47 s and SOC violations from 0.71 to 0.17, while computation time increases from 6.76 s to 25.46 s. This indicates that additional generations allow the evolutionary search to explore a broader solution space and gradually converge to higher-quality solutions, particularly under strict constraints such as SOC limits. Nevertheless, excessive iterations lead to higher computational cost, suggesting a trade-off between convergence quality and runtime efficiency.

Impact of Population Size: Comparing configurations with similar total evaluations (e.g., 30–30 vs. 20–50, both ~900 evaluations), a larger population with fewer generations (20–50) achieves slightly better makespan and lower SOC violations in a shorter time. A larger population enhances initial solution diversity, while moderate generations suffice for convergence of high-quality solutions. This finding implies that in practical applications, an appropriate combination of population size and generations can improve efficiency more effectively than merely increasing iteration counts.

Practical Deployment Implications: For the tested configurations, total computation time ranges from approximately 4 to 25 s, making the framework suitable for offline or rolling-horizon scheduling in real-world warehouses. Operators can flexibly select parameters based on available computational resources and desired solution quality; for example, the 30–40 configuration achieves performance close to 30–50 while saving about 4 s of computation. Furthermore, these results suggest that in larger-scale or highly real-time scenarios, distributed computing or work-area partitioning could be employed to further enhance computational speed, enabling more efficient multi-objective scheduling under complex operational conditions.

5.5. Discussion

The combined results from the quantitative comparisons (Section 5.2), the Pareto front analysis (Section 5.3), and the computational efficiency study (Section 5.4) collectively underscore the value and characteristics of the proposed MCMF–NSGA-II framework.

Superior Multi-Objective Balancing: By embedding the exact MCMF assignment within the evolutionary search of NSGA-II, the framework achieves global trade-offs across the conflicting objectives of makespan, energy consumption, and waiting time. This integration effectively mitigates the local biases inherent in greedy strategies and overcomes the single-objective limitation of static optimization, as evidenced by its consistent outperformance across all key metrics. Compared to standalone NSGA-II applications in logistics scheduling (e.g., [10,11,12,13,14,1516]), which often struggle with hard constraints like SOC, our hybrid approach explicitly incorporates energy-aware assignment logic, leading to a 92% reduction in SOC violations. Similarly, while pure MCMF methods (e.g., [22,23]) guarantee optimal assignment under static conditions, they lack adaptability; our framework overcomes this by dynamically tuning weights via NSGA-II, improving Pareto diversity by 22% and enabling flexible strategy shifts.

Practical Computational Efficiency: The analysis in Section 5.4 reveals a clear and manageable trade-off between computation time and solution quality. The framework generates high-quality, Pareto-optimal schedules within a time frame (approximately 4 to 25 s for the tested scales) that is viable for offline or rolling-horizon scheduling in real-world warehouses. This makes it a practical tool for operational decision-making, where planning cycles are typically on the order of minutes. In contrast, pure metaheuristics like NSGA-II or PSO often require longer runs or careful parameter tuning to achieve similar diversity [10,17,18,19], while RL-based methods [24,25,26] demand extensive training data and lack interpretability.

Effective Energy-Aware Operation: The explicit modeling of the SOC threshold within the MCMF cost model proved highly effective. The drastic reduction in SOC violations (by over 90% compared to baselines) demonstrates that energy-flow constraints can be successfully transformed from passive operational limits into active drivers of sustainable and reliable scheduling. This addresses a key gap in existing metaheuristics, which often handle SOC indirectly [7,20,21].

Practical adaptability: The framework provides decision-makers with flexibility by supporting throughput-oriented, service-oriented, or energy-oriented policies depending on system priorities. This multi-strategy capability is a step beyond single-objective MCMF or fixed-weight heuristics, aligning with the need for adaptive systems in modern logistics [1,2,3].

Limitations of the Present Study: It is important to acknowledge that the current work has certain limitations, primarily stemming from simplifying assumptions. The framework, in its present form, operates under a static task environment with complete information and employs a simplified energy consumption model that does not account for complex dynamics such as acceleration or varying shuttle kinematics. Although the computational efficiency is suitable for the tested scenarios, its performance in highly dynamic, large-scale, or highly real-time environments still requires improvement. Future work could leverage distributed computing, work-area partitioning, or parallel task processing to further enhance computational speed and system adaptability, thereby supporting more complex and real-time scheduling scenarios.

Based on the above findings, the following section summarizes the key conclusions and implications of this study.

6. Conclusions

This study has developed a hybrid MCMF–NSGA-II framework to address the energy-aware multi-objective scheduling problem in multi-tier shuttle systems. By integrating the exact optimization capability of the Minimum-Cost Maximum-Flow (MCMF) algorithm with the global exploration power of the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), the proposed approach effectively balances makespan, energy consumption, and waiting time while explicitly incorporating state-of-charge constraints.

6.1. Research Implications

Building on this work, several promising directions for future research can be outlined as follows:

- Theoretical Value: This work presents a novel hybrid optimization paradigm that successfully embeds a hard-constraint-satisfying model within a multi-objective evolutionary search. It demonstrates that the integration of exact and metaheuristic methods can effectively overcome the limitations of standalone approaches, providing a scalable solution for complex robotic scheduling problems with stringent operational constraints.

- Practical Value: For warehouse operators, the framework serves as an effective decision-support tool. It generates a diverse set of implementable scheduling strategies within practical computation times, enabling dynamic adjustment of operational priorities. The significant reduction in SOC violations directly enhances operational reliability and contributes to sustainable warehouse management.

6.2. Limitations

Despite its promising performance, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged for future improvement. First, the framework operates under a static environment with deterministic task information, which may not fully capture the dynamic nature of real-world warehouse operations. Second, the energy consumption model is simplified and does not account for complex factors such as acceleration, deceleration, or varying shuttle kinematics. Finally, while computationally feasible for the tested scenarios, the approach may face scalability challenges in extremely large-scale systems without further optimization.

6.3. Future Research Directions

Building on this work, promising future directions include:

- Extending the framework to dynamic environments with real-time task arrivals using a rolling-horizon approach.

- Incorporating more sophisticated energy consumption models that capture complex shuttle dynamics.

- Developing partitioning strategies and distributed computing architectures to enhance scalability and parallel efficiency for large-scale MTSSs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.; Methodology, P.D.; Validation, P.D.; Writing—original draft, P.D.; Writing—review & editing, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Solari, F.; Bottani, E.; Romagnoli, G. Sustainable logistics and supply chain management in the post-COVID-19 era: Future challenges and challenging futures. Sustainability 2024, 17, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, S.; Maleki Vishkaei, B.; De Giovanni, P. The impact of digital technologies and sustainable practices on circular supply chain management. Logistics 2023, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Liu, H.; Xu, S.; Wu, W. Research on scheduling optimization of multi-layer four-way shuttle system based on composite tasks. In Proceedings of the 2024 36th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Xi’an, China, 14–16 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 3765–3770. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.N.; Shen, M.D. Analysis and simulation of virtual dense storage system. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 945, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodbergen, K.J.; Vis, I.F.A. A survey of literature on automated storage and retrieval systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 194, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganbold, O.; Kundu, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, W. A simulation-based optimization method for warehouse worker assignment. Algorithms 2020, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kroll, A. A centralized multi-robot task allocation for industrial plant inspection by using A* and genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing (ICAISC), Zakopane, Poland, 29 April–3 May 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 466–474. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fang, N. Improved genetic algorithm for multi-agent task allocation with time windows. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Guilin, China, 7–10 August 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, X.; Cao, B. Research on scheduling optimization of four-way shuttle-based storage and retrieval systems. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destouet, C.; Tlahig, H.; Bettayeb, B.; Mazari, B. NSGA-II for solving a multi-objective, sustainable and flexible job shop scheduling problem. In Proceedings of the APMS 2023: Production Management Systems for Responsible Manufacturing, Service, and Logistics Futures, IFIP WG 5.7, Trondheim, Norway, 3–7 September 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 548–562. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Long, L.; Ma, Y.; Lei, L.; Liu, Z.; Dai, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Multi-robot task allocation in agriculture scenarios based on the improved NSGA-II algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Hong Kong, China, 15–18 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, H. An improved NSGA-II algorithm for multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR), Hangzhou, China, 17–19 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 494–499. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Tang, S.; Ariffin, M.K.A.M.; As’arry, A.; Wang, X. NSGA-III algorithm for optimizing robot collaborative task allocation in the internet of things environment. J. Comput. Sci. 2024, 81, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, J.; Gu, X.; Huang, M. Improved adaptive non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm with elite strategy for solving multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 106352–106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, S.; Tu, M.; Ma, H.; Shang, J.; Xiang, X. Multi-objective scheduling optimization of prefabricated components production using improved non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II. Buildings 2025, 15, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Li, Z. Improved market mechanisms task allocation method based on particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electrical Automation and Artificial Intelligence (EAAI), Guangzhou, China, 16–18 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Asma, A.; Sadok, B. PSO-based dynamic distributed algorithm for automatic task clustering in a robotic swarm. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 159, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M.; Pathak, B.K.; Kumar, R. Integrated LI-NSGA-II approach for solving the non-linear multi-objective optimization problem. Austrian J. Stat. 2024, 53, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelkamy, M.; Elias, C.M.; Mahfouz, D.M.; Shehata, O.M. Comparative analysis of various optimization techniques for solving multi-robot task allocation problem. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd Novel Intelligent and Leading Emerging Sciences Conference (NILES), Giza, Egypt, 24–26 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 538–543. [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister, S.C.; Guericke, D.; Schryen, G. A memetic NSGA-II for the multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem with real-time energy tariffs. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2024, 36, 1530–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Dong, C.; Wu, I.J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L. Optimal UAV swarm reconstruction strategy based on minimum cost maximum flow algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–24 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Salvado, J.; Mansouri, M.; Pecora, F. A network-flow reduction for the multi-robot goal allocation and motion planning problem. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 17th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Lyon, France, 23–27 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 2194–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wen, J.; Mao, B.; Yao, X. Constrained reinforcement learning for dynamic material handling. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Gold Coast, Australia, 18–23 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S.Q.; Shi, X.P.; Song, S.M. MOEA with adaptive operator based on reinforcement learning for weapon target assignment. Electron. Res. Arch. 2024, 32, 1498–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, M.; Gao, S.; Wang, T. Research on multi-UAV dynamic target allocation based on an improved NSGA-II algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2025 10th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 11–13 April 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 705–709. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).