Femtosecond Laser Crystallization of Ultrathin a-Ge Films in Multilayer Stacks with Silicon Layers

Abstract

1. Introduction

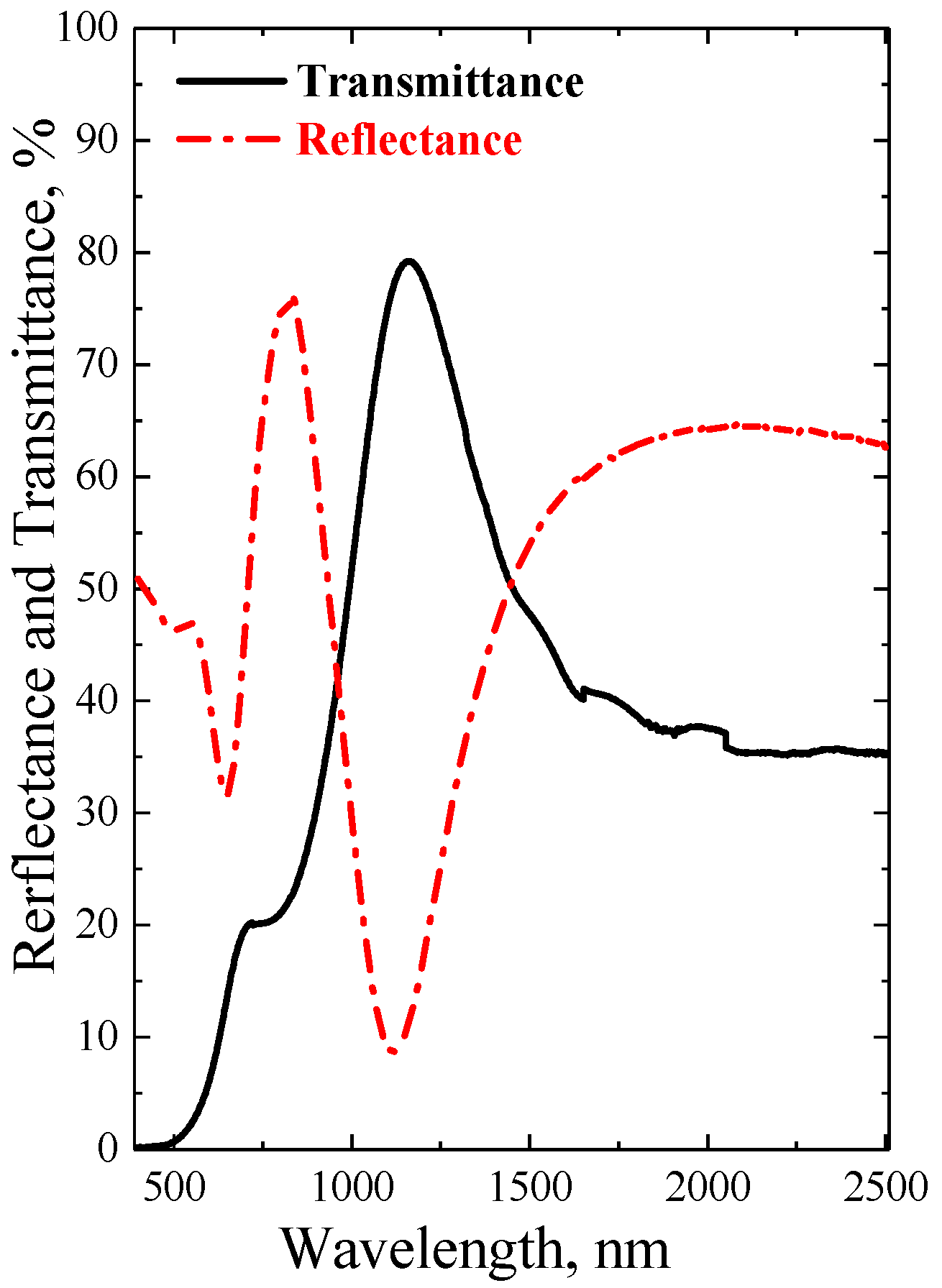

2. Materials and Methods

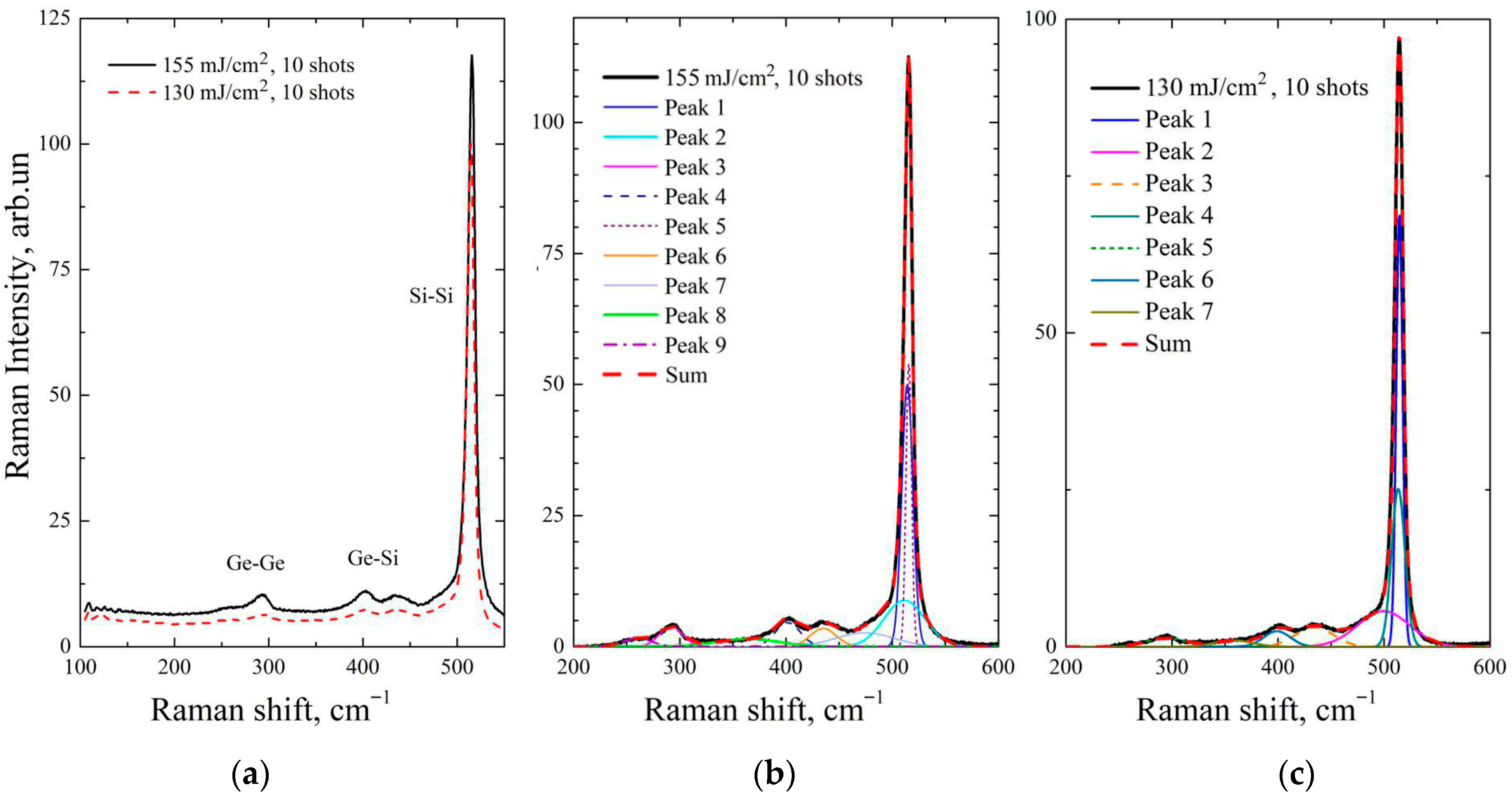

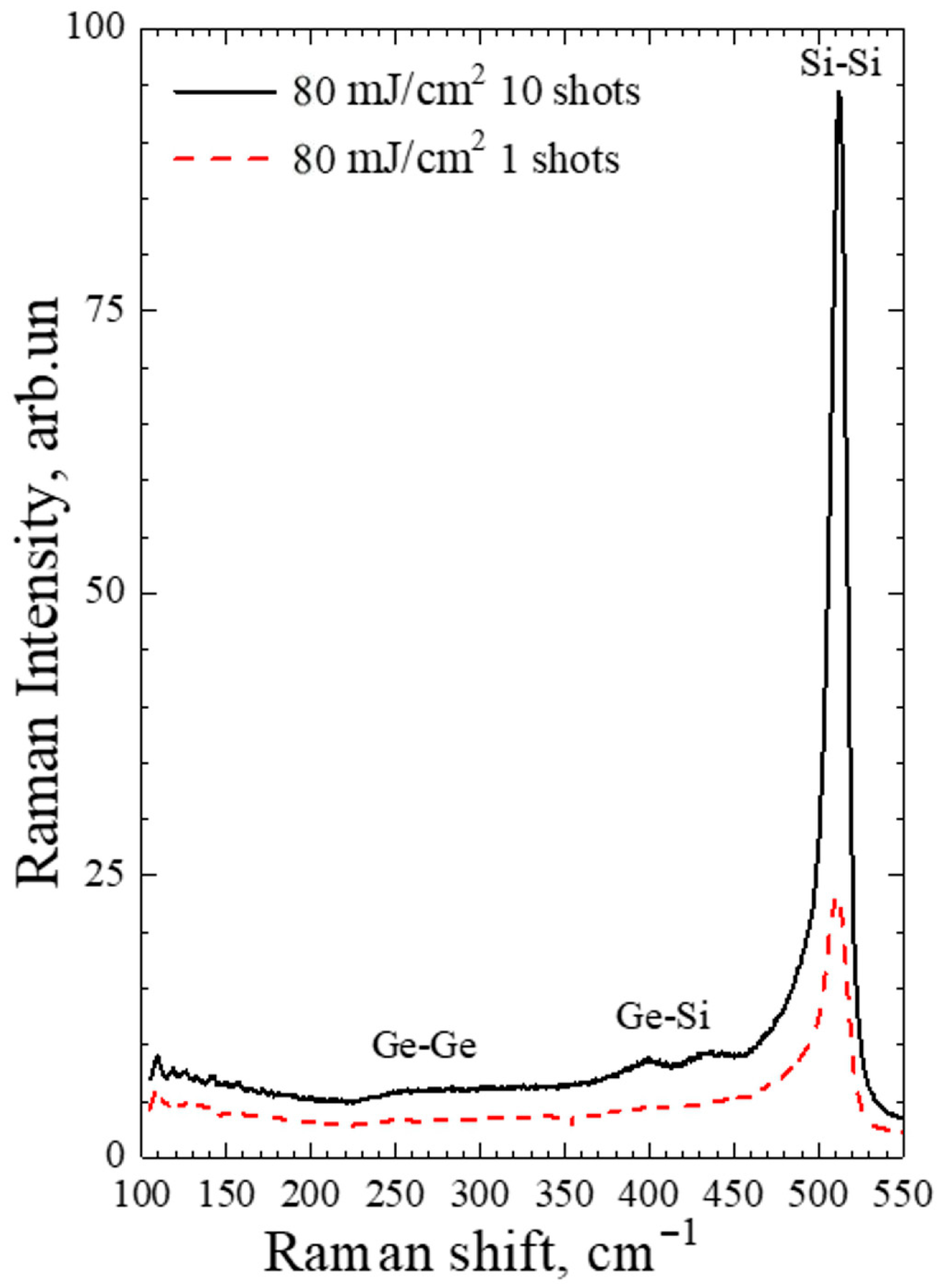

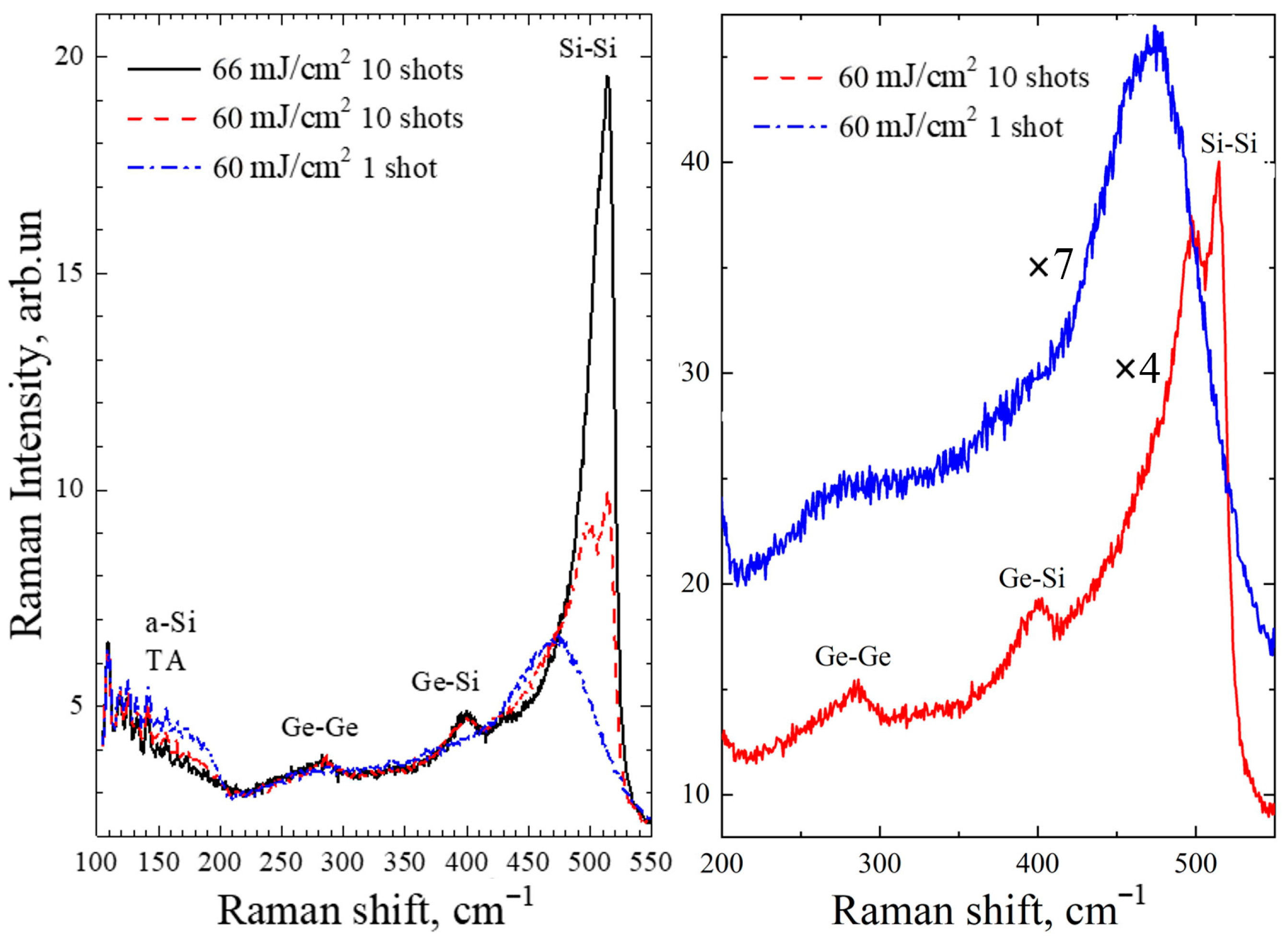

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borca, B.; Bartha, C. Advances of nanoparticles and thin films. Coatings 2022, 12, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyrev, Y.; Rubezhanska, M.Y.; Sklyar, V.K.; Naumovets, A.G.; Dadykin, A.A.; Vakulenko, O.V.; Kondratenko, S.V.; Teichert, C.; Hofer, C. Quantum size effects in multilayer Si-Ge epitaxial heterostructures. In Nanomaterials and Supramolecular Structures; Shpak, A., Gorbyk, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaly, E.M.T.; Dijkstra, A.; Suckert, J.R.; Ziss, D.; van Tilburg, M.A.J.; Mao, C.; Ren, Y.; van Lange, V.T.; Korzun, K.; Kölling, S.; et al. Direct-bandgap emission from hexagonal Ge and SiGe alloys. Nature 2020, 580, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaike, K.; Higashi, S.; Murakami, H.; Miyazaki, S. Crystallization of amorphous Ge films induced by semiconductor diode laser annealing. Thin Solid Films 2008, 516, 3595–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imajo, T.; Ishiyama, T.; Saitoh, N.; Yoshizawa, N.; Suemasu, T.; Toko, K. Record-high hole mobility germanium on flexible plastic with controlled interfacial reaction. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebohle, L.; Prucnal, S.; Skorupa, W. A review of thermal processing in the subsecond range: Semiconductors and beyond. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, C.; Lombardo, S.; Priolo, F. Crystal grain nucleation in amorphous silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 84, 5383–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreseli, O.M.; Elistratova, M.A.; Beregulin, E.V.; Yushkov, D.A.; Ershov, A.V. Photoluminescrnce of annealed Al2O3/Ge and Al2O3/Si/Ge/Si multilayer nanostructures. J. Nanopart. Res. 2024, 26, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poate, J.M.; Mayer, J.W. (Eds.) Laser Annealing of Semiconductors; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas, O.; Peacock, A.C. Laser thermal processing of group IV semiconductors for integrated photonic systems. Adv. Photonics Res. 2021, 2, 2000159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, I.; Bulgakov, A.V.; Sopha, H.; Starinskiy, S.V.; Turčičová, H.; Novák, O.; Mužík, J.; Smrž, M.; Volodin, V.A.; Mocek, T.; et al. Non-thermal regimes of laser annealing of semiconductor nanostructures: Crystallization without melting. Front. Nanotechnol. 2023, 5, 1271832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, V.A.; Cheng, Y.; Bulgakov, A.V.; Levy, Y.; Beranek, J.; Nagisetty, S.S.; Zukerstein, M.; Popov, A.A.; Bulgakova, N.M. Single-shot selective femtosecond and picosecond infrared laser crystallization of an amorphous Ge/Si multilayer stack. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 161, 109161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.-M.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Ruan, J.-J.; Huang, L.-J. Enhancing overall performances of Cu/Ag/AZO multilayer films for transparent heaters via laser/furnace step-by-step annealing mode. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 170, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacini, A.; Ali, A.H.; Harkat, L.; Nayan, N.; Adnan, N.N.; Azali, M.M.; Sani, N. Effect of laser furnace on the ITO/Mo-Ag/ITO multilayer thin film for a a-Si(n)/c-Si(p)/a-Si(p)/Al heterojunction solar cells. Sol. Energy 2024, 284, 113042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichkov, B.N.; Momma, C.; Nolte, S.; von Alvensleben, F.; Tünnermann, A. Femtosecond, picosecond and nanosecond laser ablation of solids. Appl. Phys. A 1996, 63, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pey, K.L.; Lee, P.S. Pulsed laser annealing technology for nanoscale fabrication of silicon-based devices in semiconductors. In Advances in Laser Materials Processing: Technology, Research and Applications; Lawerence, J., Pou, J., Low, D.K.Y., Toyserkani, E., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 327–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, R.; Boureau, V.; Bellouard, Y. Influence of ionization and cumulative effects on laser-induced crystallization in multilayer dielectrics. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 063402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Xia, G.; Wen, R.-T. Evolution of GeSi islands in epitaxial Ge-on-Si during annealing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 659, 159901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameshima, T.; Usui, S. Pulsed laser-induced amorphization of silicon films. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 70, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassow, R.; Köhler, J.R.; Helen, Y.; Mourgues, K.; Bonnaud, O.; Mohammed-Brahim, T.; Werner, J.H. Laser crystallization of silicon for high-performance thin-film transistors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2000, 15, L31–L34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.J.; Zheng, Y.; Qian, L.; Yang, Y.X.; Holloway, P.H.; Xue, J.G. Solution-processed, nanostructured hybrid solar cells with broad spectral sensitivity and stability. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3507–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuchlikova, T.H.; Remes, Z.; Stuchlik, J. Germanium and tin nanoparticles encapsulated in amorphous silicon matrix for optoelectronic applications. In Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary International Conference on Nanomaterials—Research & Applications (Nanocon-2018), Brno, Czech Republic, 17–19 October 2018; pp. 226–229. [Google Scholar]

- Akl, A.A.; Howari, H. Nanocrystalline formation and optical properties of germanium thin films prepared by physical vapor deposition. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2009, 70, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Sun, M.H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, C.L. Electrodeposition of crystalline germanium thin films by the electrochemical liquid-liquid-solid method. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 948, 117829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Camacho-Aguilera, R.; Bessette, J.T.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Kimerling, L.C.; Michel, J. Ge-on-Si optoelectronics. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 3354–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, I.A.; Brehm, M.; De Seta, M.; Isella, G.; Paul, D.J.; Virgilio, M.; Capellini, G. On-chip infrared photonics with Si-Ge-heterostructures: What is next? APL Photonics 2022, 7, 050901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Li, L.; Zuo, Y.; He, C.; Li, C.; Xue, C.; Cheng, B.; Wang, Q. Ge/Si quantum dots thin film solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 082101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ni, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Cai, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Nanocrystalline germanium nip solar cells with spectral sensitivities extending into 1450 nm. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 045108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pchelyakov, O.P.; Bolkhovityanov, Y.B.; Dvurechenskiĭ, A.V.; Sokolov, L.V.; Nikiforov, A.I.; Yakimov, A.I.; Voigtländer, B. Silicon-germanium nanostructures with quantum dots: Formation mechanisms and electrical properties. Semiconductors 2000, 34, 1229–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Watling, J.R.; Wilkins, R.C.W.; Boriçi, M.; Barker, J.R.; Asenov, A.; Roy, S. Si/SiGe heterostructure parameters for device simulations. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2004, 19, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Bulgakov, A.V.; Bulgakova, N.M.; Beránek, J.; Milekhin, I.A.; Popov, A.A.; Volodin, V.A. Ultrafast infrared laser crystallization of amorphous Ge films on glass substrates. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.M. Simple technique for measurements of pulsed Gaussian-beam spot sizes. Opt. Lett. 1982, 7, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgakov, A.V.; Beranek, J.; Volodin, V.A.; Cheng, Y.; Levy, Y.; Nagisetty, S.S.; Zukerstein, M.; Popov, A.A.; Bulgakova, N.M. Ultrafast infrared laser crystallization of amorphous Si/Ge multilayer structures. Materials 2023, 16, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.H. Electrical and optical properties of amorphous germanium. Phys. Rev. 1967, 154, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichelis, F.; Minetti-Mezzetti, E.; Tagliaferro, A.; Tresso, E.; Rava, P.; Ravindra, N.M. Optical properties of hydrogenated amorphous silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 1986, 59, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.E., Jr.; Brodsky, M.H.; Crowder, B.L.; Nathan, M.I.; Pinczuk, A. Raman spectra of amorphous Si and related tetrahedrally bounded semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1971, 26, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.C.; Fang, C.J.; Cardona, M.; Genzel, L. Far-infrared absorption in pure and hydrogenated a-Ge and a-Si. Phys. Rev. B 1980, 22, 2913–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, D.; Cardona, M. Raman scattering in pure and hydrogenated amorphous germanium and silicon. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1979, 32, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, V.A.; Efremov, M.D.; Deryabin, A.S.; Sokolov, L.V. Determination of the composition and stresses in GexSi(1−x) heterostructures from Raman spectroscopy data: Refinement of model parameters. Semiconductors 2006, 40, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawa, S.; Yokogawa, R.; Yoshioka, K.; Arai, Y.; Yonenaga, I.; Ogura, A. Temperature dependence of Raman peak shift in single crystalline silicon-germanium. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 064004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renucci, M.A.; Renucci, J.B.; Cardona, M. Raman scattering in Ge-Si alloys. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Light Scattering in Solids, Flammarion, Paris, France, 19–23 July 1971; pp. 326–329. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, P.M.; Dacol, F.H.; Tsang, J.C.; Chu, J.O. Raman scattering analysis of relaxed GexSi1−x alloy layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1993, 62, 2069–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevtsov, N.; Chubenko, E.; Bondarenko, V.; Gavrilin, I.; Dronov, A.; Gavrilov, S.; Goroshko, D.; Goroshko, O.; Rymski, G.; Yanushkevich, K. Thermoelectric materials based on cobalt-containing sintered silicon-germanium alloys. Mater. Res. Bull. 2025, 284, 113258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyr, M. Fityk: A General-Purpose Peak Fitting Program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2010, 43, 1126–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigunov, D.M.; Kamaev, G.N.; Kashkarov, P.K.; Volodin, V.A. On Raman scattering cross section ratio of crystalline and microcrystalline to amorphous silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 113, 023101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Kochubei, S.A.; Popov, A.A.; Volodin, V.A. On Raman scattering cross section ratio of amorphous to nanocrystalline germanium. Solid State Commun. 2020, 313, 113897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, V.A.; Sachkov, V.A. Improved model of optical phonon confinement in silicon nanocrystals. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2013, 116, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, K.H.; Zayak, A.T.; Kwak, H.; Chelikowsky, J.R. First-principles study of confinement effects on the Raman spectra of Si nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 115504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Y.; Wee, A.T.S.; Huan, C.H.A.; Shen, Z.X.; Choi, W.K. Phonon confinement in Ge nanocrystals in silicon oxide matrix. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 033107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, J.; Zhang, K.; Xie, X. Comparison of models for Raman spectra of Si nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, 9263–9266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.K.; Yoshiya, M.; Matsubara, H. Influence of number of layers on thermal properties of nano-structured zirconia film fabricated by EB-PVD method. J. Jpn. Inst. Met. 2005, 69, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.; Bulgakov, A.V.; Bulgakova, N.M.; Beránek, J.; Kacyuba, A.V.; Volodin, V.A. Femtosecond Laser Crystallization of Ultrathin a-Ge Films in Multilayer Stacks with Silicon Layers. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011082

Cheng Y, Bulgakov AV, Bulgakova NM, Beránek J, Kacyuba AV, Volodin VA. Femtosecond Laser Crystallization of Ultrathin a-Ge Films in Multilayer Stacks with Silicon Layers. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011082

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yuzhu, Alexander V. Bulgakov, Nadezhda M. Bulgakova, Jiří Beránek, Aleksey V. Kacyuba, and Vladimir A. Volodin. 2025. "Femtosecond Laser Crystallization of Ultrathin a-Ge Films in Multilayer Stacks with Silicon Layers" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011082

APA StyleCheng, Y., Bulgakov, A. V., Bulgakova, N. M., Beránek, J., Kacyuba, A. V., & Volodin, V. A. (2025). Femtosecond Laser Crystallization of Ultrathin a-Ge Films in Multilayer Stacks with Silicon Layers. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011082