Effects of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Antioxidant Vitamins (A, C, and E) and Antioxidant Activity in Fruit and Vegetable Preparations: A Review

Abstract

1. A Brief History of Pressurization Technology

2. High-Pressure Processing (HPP) as a Food Preservation Technology

2.1. Methodology Used to Select HPP Bibliography

2.2. Principles of High-Pressure Technology Applied in Foods

- -

- The isostatic principle states that pressure is rapidly and evenly distributed throughout the entire food product, regardless of its shape, size, or structure. The pressure spreads equally in all directions, ensuring uniform impact across the sample. As a result of this balanced distribution, the molecular bonds and structure of the food remain unaffected [16].

- -

- According to Le Chatelier’s principle, when a system at dynamic equilibrium experiences a change in conditions, it will adjust to oppose that change and restore equilibrium. Therefore, if pressure is applied to a system in equilibrium, the system will respond in a way that reduces the effect of the pressure, typically by shifting toward a state with lower volume. Processes such as phase transitions, chemical reactions, and molecular rearrangements that result in a volume decrease are generally promoted by increased pressure, while those that cause volume expansion are inhibited [17]. The rate at which a reaction proceeds can either increase or decrease depending on the “activation volume”—the difference between the volume of the activated complex and that of the reactants. If this value is negative, pressure increases the reaction rate, and if it’s positive, pressure slows it down [18]. Because biochemical reactions often involve volume changes, pressure can significantly influence their behavior [19].

- -

- In physical chemistry, the Arrhenius equation describes how reaction rates are affected by temperature. It is widely used to explain the influence of temperature on the speed of chemical reactions [20].where k(T) is the reaction rate at temperature T, k(Tref) is the reaction rate at a reference temperature Tref, Ea is the activation energy, and R is the universal gas constant.

- -

- The microscopic ordering principle states that at a constant temperature, increasing pressure leads to a greater degree of molecular organization within a substance. Therefore, pressure and temperature have opposing effects on molecular structure [21]. In microorganisms, low-pressure exposure may cause reversible alterations in cell shape, but at higher pressures, these changes become irreversible. Cell membrane disruption occurs, leading to leakage of large amounts of internal cellular material and ultimately resulting in cell death. Subsequently, the application of high pressure may lead to cellular deformation and structural damage, resulting in tissue softening and the release of intracellular fluids (cell serum).

2.3. HPP as a Green and Sustainable Technology

2.4. HPP Relevance in the Food Market

2.5. Advantages and Limitations of High-Pressure Processing

- Nutritional Quality: HPP is known for its ability to preserve the nutritional integrity of food products. It enables high retention of heat-sensitive vitamins, particularly those found in fresh produce, and helps maintain the bioactivity of functional compounds. Moreover, it supports the production of clean-label foods by reducing or eliminating the need for chemical preservatives, additives, or salt [29]. Additional health-related nutritional benefits associated with HPP include increased levels of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and polyphenols, reduction in the glycemic index, and enhanced antioxidant activity [59].

- Food Safety: One of the key advantages of HPP is its effectiveness in microbial inactivation, thereby significantly enhancing food safety. The process can activate or deactivate specific enzymes depending on the pressure and duration applied, and it enables substantial shelf-life extension—from as little as 2–3 days up to 180 days in some cases. HPP has also been shown to facilitate the removal of certain toxins and prevent their formation in food matrices [60]. However, further research is needed to assess its effects on other harmful substances, such as food contaminants [61]. Additionally, extended shelf life contributes to a reduction in the number of expired products and, consequently, lowers waste and disposal costs.

- Sensory Attributes: HPP-treated foods typically exhibit excellent retention of sensory qualities such as taste [62], flavor, and color, closely resembling those of fresh, untreated products [6]. Nevertheless, the technology may affect certain textural elements [63] and alter the aroma profile [64,65], which requires careful formulation and process optimization.

- Commercial Advantages: High-pressure processing (HPP) is particularly advantageous for application to packaged foods, as it significantly reduces the risk of secondary contamination. The technology is adaptable to both batch and semi-continuous operation modes, making it versatile for industrial use. HPP is also considered an environmentally friendly technology that supports the production of “clean-label” foods—products formulated with a minimal number of safe, hazard-free ingredients that are generally accepted by consumers [66]. It is important to note that the term “clean label” encompasses a broad range of often ambiguous descriptors such as “all-natural,” “locally grown,” “GM-free,” and “minimally processed,” which are frequently associated with claims of wholesomeness and health benefits despite lacking robust scientific validation [67]. From an environmental perspective, HPP demonstrates a lower carbon footprint compared to traditional thermal processes [49]. The energy requirements for HPP are notably lower than those for conventional thermal pasteurization, and the process generates minimal waste. While the overall production costs per unit for HPP-treated products tend to be higher than those of thermally processed equivalents—partly due to energy consumption—HPP utilizes relatively low amounts of electricity and allows for the recycling of the pressurization fluid (typically water), resulting in virtually zero emissions. Once the target pressure is reached during processing, maintaining this pressure requires minimal additional energy input. Moreover, unlike heat-based technologies, HPP does not necessitate additional energy for cooling the product after the treatment duration has elapsed [28]. Advantages related to being a greener technology compared to traditional ones using heat are another issue to be considered before installing this technology in the food industry. Life cycle analysis has shown that HPP technology may reduce environmental impacts when compared to traditional thermal processing methods [4].

- Nutritional quality: possible modification of lipids and the structure of other macromolecules. Several researchers have reported that enzymatic browning and flavor changes during storage remain challenges [72]. Other effects are possible damage from free radicals.

- Food safety: high-pressure treatments do not inactivate microbial spores; more research is needed on reactions producing contaminants that can be affected by HPP [59]. Enzyme inactivation can’t be completely performed by HPP treatments.

- Sensory attributes: HPP can induce modifications in the structure and texture of food products, including phenomena such as cloud loss and alterations in key physical properties—such as melting point, solubility, density, and viscosity—which can, in turn, impact textural quality [38]. Additionally, HPP may lead to undesirable changes in the overall flavor profile of plant-based foods, particularly during storage, if enzymatic inactivation is incomplete [71].

- Commercial: higher equipment cost, which means huge amounts of capital; difficulties for continuous processing; although “in-bulk” HPP technology was implemented in 2021 for juices, but it is more expensive than HPP units working in batch mode; limited technical knowledge among food manufacturers regarding its implementation and validation protocols [72] as well as concerns related to process scalability and varying levels of consumer acceptance [49]; although, the emergent technology most accepted by consumers was HPP [73] despite the fact that pressurized food is more expensive.

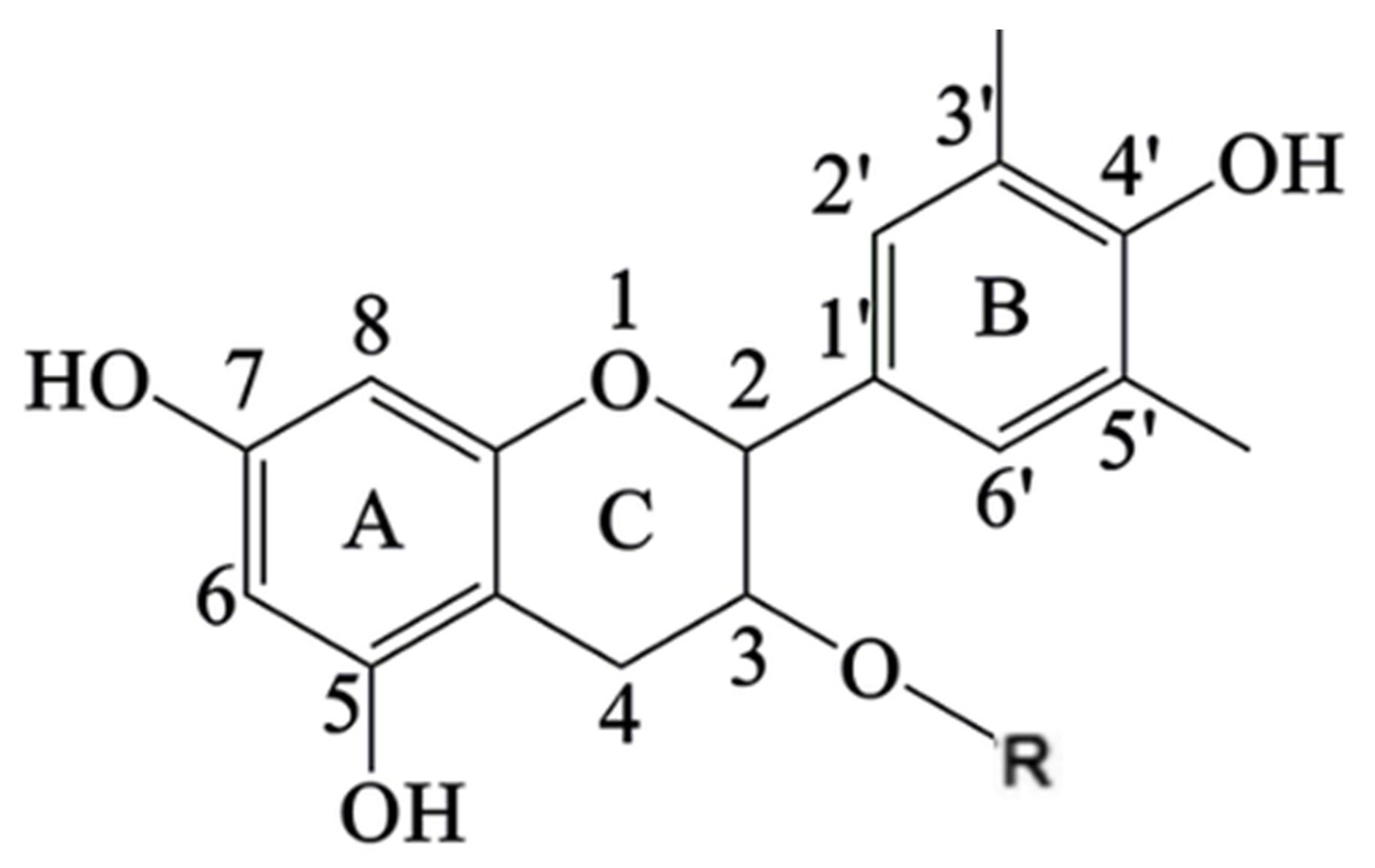

3. Antioxidant Vitamins (A, C, E) and Antioxidant Compounds in Fruits and Vegetables Preparations

- Radical/ROS scavenging assays, such as ORAC (oxygen radical absorbance capacity), DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), and TEAC (Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity).

- Non-radical redox potential assays, including FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) and CUPRAC (cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity), among others [83].

3.1. Modifications on Antioxidant Vitamins After HPP

3.2. Effects of HPP on Antioxidant Activity (AA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demazeau, G.; Rivalain, N. High hydrostatic pressure and biology: A brief history. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.R.; Nelson, P.E. High pressure processing and preservation of foods. Food Rev. Int. 1998, 14, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, V.M.; Martínez-Monteagudo, S.I.; Gupta, R. Principles and application of High pressure-based technologies in the food industry. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, N.N.; Koubaa, M.; Roojinejad, S.; Juliano, P.; Alpas, H.; Inácio, R.S.; Saraiva, J.A.; Barba, F. Landmarks in the historical development of twenty first century food processing technologies. Food Res. Int. 2017, 97, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waghmare, R. High pressure processing of fruit beverages: A recent trend. Food Hum. 2024, 2, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Li, R.; Song, X.; Clausen, M.P.; Orlien, V.; Giacalone, D. The effect of high-pressure processing on sensory quality and consumer acceptability of fruit juices and smoothies: A review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, P.M.; Sharma, N.; Maibam, B.D.; Sharma, M. Review on effect of innovative technologies on shelf-life extension of non-dairy sources from plant matrices. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, D.; Le Gourrierec, S.; Pérez-Lamela, C. Effects of High Pressure Processing on the microbial inactivation in fruit preparations and other vegetable based beverages. Agriculture 2017, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houška, M.; Silva, F.V.M.; Evelyn; Buckow, R.; Terefe, N.S.; Tonello, C. High Pressure Processing Applications in Plant Foods. Foods 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, C.; Jayachandran, L.E.; Kothakota, A.; Pandiselvam, R.; Balasubramaniam, V.M. Influence of high pressure pasteurization on nutritional, functional and rheological characteristics of fruit and vegetable juices and purees-an updated review. Food Control 2023, 146, 109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouryieh, H.A. Novel and emerging technologies used by the U.S. food processing industry. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Tang, J.; Barrett, D.M.; Sablani, S.S.; Anderson, N.; Powers, J.R. Thermal Pasteurization of vegetables: Critical factors for process design and effects on quality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 57, 2970–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inanoglu, S.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Sablani, S.S.; Zhu, M.; Keener, L.; Tang, J. High-pressure pasteurization of low-acid chilled ready-to-eat food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4939–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira Gomes, B.A.; Silveira Alexandre, A.C.; Vieira de Andrade, G.A.; Pereira Zanzini, A.; Araújo de Barros, H.E.; dos Santos Ferraz e Silva, L.M.; Costa, P.A.; de Barros Vilas Boas, E.V. Recent advances in processing and preservation of minimally processed fruits and vegetables: A review—Part 2: Physical methods and global market outlook. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melios, S.; Stramarkou, M.; Grasso, S. Innovations in food: A review on the consumer perception of non-thermal processing technologies. LWT 2025, 223, 117688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.; Jahangir Chughtai, M.F.; Mehmood, T.; Ahsan, S.; Liaqat, A.; Nadeem, M.; Sameed, N.; Saeed, K.; Rehman, J.U.; Ali, A. High-Pressure Processing; Principle, Applications, Impact, and Future Prospective. In Sustainable Food Processing and Engineering Challenges; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, R.; Rizvi, Q.H.; Altaf, A.; Pandey, V.K.; Dar, A.H.; Sharma, H. High Pressure Processing as an Advancement in Food Processing. J. Food Chem. Nanotech. 2024, 10, S101–S110. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, J.A.; Pérez Lamela, C. Pressure processing of foods: Microbial inactivation kinetics and pressure & temperature effects on chemical changes—Part 2. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech. 2008, 19, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, N.K.; Raghavarao, K.S.M.S.; Balasubramaniam, V.M.; Niranjan, K.; Knorr, D. Opportunities and Challenges in High Pressure Processing of Foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 69–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M.; Normand, M.D.; Corradini, M.G. The Arrhenius equation revisited. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 830–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveena, B.; Nagaraju, M. Review on principles, effects, advantages and disadvantages of High Pressure Processing of food. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 8, 2964–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, R.; Saraiva, J.; Pérez Lamela, C.; Torres, J. Antonio. Reaction kinetics analysis of chemical changes in pressure-assisted thermal processing. Food Eng. Rev. 2009, 1, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, S.I.; Balasubramaniam, V.M. Chapter 1. Fundamentals and Applications of High-Pressure Processing Technology. In High Pressure Processing of Food: Principles, Technology and Applications; Food Engineering Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Setikaite, I.; Koutchma, T.; Patazca, E.; Parisi, B. Effects of Water Activity in Model Systems on High-Pressure Inactivation of Escherichia coli. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2009, 2, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, G. Review on high-pressure processing of foods. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1568725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, W.; Jun, S. Conventional and Emerging Combination Technologies for Food Processing. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonello-Samson, C.; Queirós, R.P.; González-Angulo, M. Advances in high-pressure processing in-pack and in-bulk commercial equipment. In Present and Future of High Pressure Processing: A Tool for Developing Innovative, Sustainable, Safe and Healthy Foods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Chacha, J.S.; Zhang, L.; Ofoedu, C.E.; Suleiman, R.A.; Dotto, J.M.; Roobab, U.; Agunbiade, A.O.; Duguma, H.T.; Mkojera, B.T.; Hossaini, S.M.; et al. Revisiting non-thermal food processing and preservation methods—Action mechanisms, pros and cons: A technological update (2016–2021). Foods 2021, 10, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojecka, A.A.; Drozd-Rzoska, A.; Rzoska, S.J. Food Preservation in the Industrial Revolution Epoch: Innovative High Pressure Processing (HPP, HPT) for the 21st-Century Sustainable Society. Foods 2024, 13, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubeddu, A.; Fava, P.; Pulvirenti, A.; Haghighi, H.; Licciardello, F. Suitability Assessment of PLA Bottles for High-Pressure Processing of Apple Juice. Foods 2021, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liao, X. Effect of High Pressure Processing on the preparation and characteristic changes of biopolymer-based films in food packaging applications. Food Eng. Rev. 2021, 13, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.K. Exploring the significance of emerging blue food processing technologies for sustainable development. Food Res. Int. 2025, 200, 115429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmaram, N.; Rosentrater, K.A. Overview of some recent advances in improving water and energy efficiencies in food processing factories. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambrak, A.R.; Nutrizio, M.; Djekić, I.; Pleslić, S.; Chemat, F. Internet of nonthermal food processing technologies (iontp): Food industry 4.0 and sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, R.; Johnson, H.; Richards, C. From surplus-to-waste: A study of systemic overproduction, surplus and food waste in horticultural supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, M.A.; Sanguansri, L.; Fox, E.M.; Cobiac, L.; Cole, M.B. Recovery of wasted fruit and vegetables for improving sustainable diets. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, R.; Lichter, A.; Terry, L.A.; Harker, R.; Buzby, J. Postharvest losses of fruit and vegetables during retail and in consumers’ homes: Quantifications, causes, and means of prevention. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 139, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakka, A.K.; Sriraksha, M.S.; Ravishankar, C.N. Sustainability of emerging green non-thermal technologies in the food industry with food safety perspective: A review. LWT 2021, 151, 112140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, E.P.; Gayialis, S.P.; Panayiotou, N.; Papadopoulos, G.A. A holistic Framework for evaluating food Loss and waste due to marketing standards across the entire Food Supply Chain. Foods 2024, 13, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.K.; Bloom, J.D.; Dunning, R.D.; Gunter, C.C.; Boyette, M.D.; Creamer, N.G. Farmer harvest decisions and vegetable loss in primary production. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Ohm, S.; Dirksmeyer, W.; Klockgether, K. Approaches to reduce food losses in German fruit and vegetable production. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sestelo, A.B.; Sendra de Saa, R.; Pérez Lamela, C.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.; Rúa, M.L.; Pastrana-Castro, L. Overall quality properties in pressurized kiwi purée: Microbial, physicochemical, nutritive and sensory test during refrigerated storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 20, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterkamp, E.; van der Sluis, A.; van Geffen, L.; Aramyan, L.; Bos-Brouwers, H. Cosmetic Aspects in Specific Marketing Standards for Fruit and Vegetables; Removing Cosmetic Aspects from the EU Marketing Standards: Implications for the Market and Impact on Food Waste; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, H.M.; Pasquali, M.B.; dos Anjos, A.I.; Sarinho, A.M.; de Melo, E.D.; Andrade, R.; Batista, L.; Lima, J.; Diniz, Y.; Barros, A. Innovative and sustainable food preservation techniques: Enhancing food quality, safety, and environmental sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap-Singh, A.; Noore, S.; Mandal, R.; Singh, A. Sustainable processing through efficient use of energy and minimizing waste production. In Nonthermal Processing in Agri-Food-Bio Sciences: Sustainability and Future Goals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 723–748. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Lamela, C. Green Technologies for Sustainable Food Production and Preservation: High-Pressure Processing. In Sustainable Food Science—A Comprehensive Approach; Ferranti, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 158–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Hernández, H.M.; Moreno-Vilet, L.; Villanueva-Rodríguez, S.J. Current status of emerging food processing technologies in Latin America: Novel non-thermal processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 58, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, F.; Maurizzi, E.; Quartieri, A.; De Leo, R.; Gullo, M.; Pulvirenti, A. Non-thermal techniques and the “hurdle” approach: How is food technology evolving? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.; Khalid, S.; Altemimi, A.B.; Abrar, S.; Ansar, S.; Aslam, N.; Hussain, M.; Aadil, R.M. Advances in non-thermal technologies: A revolutionary approach to controlling microbial deterioration, enzymatic activity, and maintaining other quality parameters of fresh stone fruits and their processed products. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignali, G.; Gozzi, M.; Pelacci, M.; Stefanini, R. Non-conventional stabilization for fruit and vegetable juices: Overview, technological constraints, and energy cost comparison. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 1729–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Gómez, M.; Pallarés, N.; Salgado-Ramos, M.; Barba, F.J.; Berrada, H.; Castagnini, J.M. Sustainable processing of food side streams and underutilized leftovers into high-added-value chemicals assisted by pulsed electric fields and high-pressure processing-based technologies. Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 171, 117506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, F.; Bottani, E.; Rizzi, A.; Vignali, G. Evaluation of the economic and environmental sustainability of high pressure processing of foods. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 60, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuonwu, J.C.; Tassou, S.A. Model-based energy performance analysis of high pressure processing systems. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 47, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya, R.K.; Singla, M.; Kaura, R.; Singh, C.B.; Singh, A. Exploring the impact of high pressure processing on the characteristics of processed fruit and vegetable products: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nut 2024, 65, 3856–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Industryarc.com. High Pressure Processing Market Forecast (2025–2030). Available online: https://www.industryarc.com/Research/High-Pressure-Processing-Market-Research-513989 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Global Growth Insights. High Pressure Processing Food Market. Available online: https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/market-reports/high-pressure-processing-hpp-food-market-100548 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Juyal, D.; Rawat, A. Development and analysis of mix fruit based smoothie. J. Adv. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestes, A.; Canella, M.H.M.; Helm, C.V.; Gomes da Cruz, A.; Prudencio, E.S. The use of cold pressing technique associated with emerging nonthermal technologies in the preservation of bioactive compounds in tropical fruit juices: An overview. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 51, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hsu, C.; Wang, C. Healthy expectations of high hydrostatic pressure treatment in food processing industry. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazda, P.; Glibowski, P. Advanced Technologies in Food Processing—Development Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Avellaneda, Z.; Pateiro Moure, M.; Chotyakul, N.; Torres, J.A.; Welti Chanes, J.; Pérez Lamela, C. Benefits and limitations of food processing by high-pressure technologies: Effects on functional compounds and abiotic contaminants. CyTA-J. Food 2011, 9, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadapaneni, R.K.; Daryaei, H.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B.M. High-Pressure Processing of Berry and Other Fruit Products: Implications for Bioactive Compounds and Food Safety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3877–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Al-Najjar, S.Z.; Anumudu, C.K.; Hart, A.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Non-Thermal Technologies in Food Processing: Implications for Food Quality and Rheology. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Pérez, N. Use of High Pressure Processing in Albariño Wine as Alternative to Filtration. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Vigo, Vigo, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Yin, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Song, Z.; Du, M.; Guo, C.; Yi, J. Preserving aroma in east and southeast Asian sauces: A review of thermal and non-thermal processing techniques. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 101, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roobab, U.; Inam-Ur-Raheem, M.; Khan, A.W.; Arshad, R.N.; Zeng, X.; Aadil, R.M. Innovations in high-pressure technologies for the development of clean label dairy products: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 970–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roobab, U.; Shabbir, M.A.; Khan, A.W.; Arshad, R.N.; Bekhit, A.E.-D.; Zeng, X.-A.; Inam-Ur-Raheem, M.; Aadil, R.M. High-pressure treatments for better quality clean-label juices and beverages: Overview and advances. LWT 2021, 149, 111828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaoka, T.; Itoh, N.; Hayashi, R. High-pressure effect on Maillard reaction. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1991, 55, 2071–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Granado-Lorencio, F.; de Ancos, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Blanco, I.; Herrero-Barbudo, C.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Plaza, L.; Cano, M.P. Greater bioavailability of xanthophylls compared to carotenes from orange juice (high-pressure processed, pulsed electric field treated, low-temperature pasteurised, and freshly squeezed) in a crossover study in healthy individuals. Food Chem. 2022, 37, 130821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yeoh, W.K.; Forney, C.; Siddiqui, M.W. Advances in postharvest technologies to extend the storage life of minimally processed fruits and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2632–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolvis Pou, K.R. Applications of high pressure technology in food processing. Int. J. Food Stud. 2021, 10, 248–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Kebede, B.; Kristiani, K.; Buvé, C.; Van Loey, A.; Grauwet, T.; Hendrickx, M. The potential of kiwifruit puree as a clean label ingredient to stabilize high pressure pasteurized cloudy apple juice during storage. Food Chem. 2018, 255, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Plancken, I.; Verbeyst, L.; De Vleeschouwer, K.; Grauwet, T.; Heiniö, R.-L.; Husband, F.A.; Lille, M.; Mackie, A.R.; Van Loey, A.; Viljanen, K.; et al. (Bio)chemical reactions during high pressure/high temperature processing affect safety and quality of plant-based foods. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2012, 23, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N.; Panghal, A.; Chaudhary, G. Novel Technologies in Food Science; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cardello, A.V.; Schutz, H.G.; Lesher, L.L. Consumer perceptions of foods processed by innovative and emerging technologies: A conjoint analytic study. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis, K.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R. The efficacy and safety of high-pressure processing of food. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07128. [Google Scholar]

- Stratakos, A.C.; Linton, M.; Patterson, M.F.; Koidis, A. Effect of high-pressure processing on the shelf life, safety and organoleptic characteristics of lasagne ready meals during storage at refrigeration and abuse temperature. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safwa, S.; Ahmed, T.; Talukder, S.; Sarkar, A.; Rana, R. Applications of non-thermal technologies in food processing Industries-A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artés-Hernández, F.; Castillejo, N.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Phytochemical fortification in fruit and vegetable beverages with green technologies. Foods 2021, 10, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, S.; Martı́n-Belloso, O.; Elez-Martı́nez, P.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. The application of non-thermal technologies for the production of healthier high-quality fruit/vegetable juices and beverages—A revisit. In Proceedings of the III International Symposium on Beverage Crops, Murcia, Spain, 24–27 April 2023; ISHS Acta Horticulturae: Leuven, Belgium, 2024; p. 1387. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara, J.S.; Figueira, J.; Perestrelo, R.; Silva, C.; Pereira, J. Bioactive compounds from different food sources: Biosynthesis, occurrence and potential health benefits. In Polyphenols: Food Sources, Bioactive Properties and Antioxidant Effects; Cobb, D.T., Ed.; Nova Science Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 131–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Lamela, C.; Franco, I.; Falqué, E. Impact of high-pressure processing on antioxidant activity during storage of fruits and fruit products: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, E. (Ed.) Antioxidants. In Physiology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Apak, R. Current Issues in Antioxidant Measurement. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9187–9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, Y. Measurement of antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roginsky, V.; Lissi, E.A. Review of methods to determine chain-breaking antioxidant activity in food. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pachón, M.S.; Villano, D.; Troncoso, A.M.; García-Parrilla, M.C. Antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds: From in vitro results to in vivo evidence. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, İ. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Jia, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, X. Association between vitamin C intake and thyroid function among US adults: A population-based study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1462251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, A.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Exploring the potential of antioxidants from fruits and vegetables and strategies for their recovery. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 77, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Liu, X.; Shen, Z.; Wu, P.; Zhong, L.; Lin, F. Cell signaling pathways based on vitamin C and their application in cancer therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alur, A.; Das, P.; Chikkamath, V. Ascorbic Acid in Health and Disease: A Review. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2021, 15, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Pezeshki, A.; Jafari, S.M. Beta-Carotene. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients. Properties and Applications; Mahdi Jafari, S., Rashidinejad, A., Simal-Gandara, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A.C.; West, K.P. Vitamin A: Deficiency and interventions. In Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 1–4, pp. 460–470. [Google Scholar]

- Aune, D. Plant Foods, Antioxidant Biomarkers, and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality: A Review of the Evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S404–S421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, R.; Nowicka, B.; Kruk, J. Vitamin E-occurrence, biosynthesis by plants and functions in human nutrition. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykas, D.P.; Rodriguez-Saona, L. What’s in Your Fruit Juice?—Rapid Quality Screening Based on Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva-Mojón, L.; Pérez-Lamela, C.; Falqué-López, E. Smoothies Marketed in Spain: Are They Complying with Labeling Legislation? Nutrients 2023, 15, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishijima, C.; Sato, Y.; Chiba, T. Nutrient Intake from Voluntary Fortified Foods and Dietary Supplements in Japanese Consumers: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marketsandmarkets.com (Juice Concentrates Market). Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/juice-concentrate-market-220829333.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Préstamo, G.; Arroyo, G. Protective effect of ascorbic acid against the browning developed in apple fruit treated with high hydrostatic pressure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3541–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho, F.; Lambert, Y.; Demazeau, G.; Largeteau, A.; Bouvier, J.-M.; Narbonne, J.-F. Effect of ultra-high hydrostatic pressure on hydrosoluble vitamins. J. Food Eng. 1999, 39, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feofilova, E.P. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure on the carotenoid content in the mycelium of Blakeslea trispora Thaxter. Mikrobiologiya 1975, 44, 180–182. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, R.K.; Aby Bekhit, A.E.D.; Roohinejad, S.; Rengasamy, K.R.; Keum, Y.S. Chemical stability of lycopene in processed products: A review of the effects of processing methods and modern preservation strategies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Esteve, M.J.; Frigola, A. Impact of high-pressure processing on vitamin E (α-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol), vitamin D (cholecalciferol and ergocalciferol), and fatty acid profiles in liquid foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3763–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Weng, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.; Pan, Y. Effects of ultra-high pressure, thermal pasteurization, and ultra-high temperature sterilization on color and nutritional components of freshly-squeezed lettuce juice. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Hopfhauer, S.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Böhm, V. High-Pressure processing and heat sterilization of kale: Impact on extractability, antioxidant capacity and storability of carotenoids and vitamin E. Appl. Res. 2022, 1, e202200025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Ferreira Da Silveira, T.; Cristianini, M.; Kuhnle, G.G.; Braga Ribeiro, A.; Teixeira Filho, J.; Teixeira Godoy, H. Anthocyanins, non-anthocyanin phenolics, tocopherols and antioxidant capacity of açaí juice (Euterpe oleracea) as affected by high pressure processing and thermal pasteurization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 55, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Dhenge, R.; Rodolfi, M.; Littardi, P.; Lacey, K.; Cavazza, A.; Grimaldi, M.; Lolli, V.; Cirlini, M.; Chiancone, B.; et al. The Effects of High-Pressure Processing Pre-Treatment on Apple Fruit for Juice Production. Foods 2024, 13, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, J.; Barba, F.J.; Skąpska, S.; Marszałek, K. Changes in the polyphenolic profile and oxidoreductases activity under static and multi-pulsed high pressure processing of cloudy apple juice. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibowo, S.; Essel, E.A.; De Man, S.; Bernaert, N.; Van Droogenbroeck, B.; Grauwet, T.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Comparing the impact of high pressure, pulsed electric field and thermal pasteurization on quality attributes of cloudy apple juice using targeted and untargeted analyses. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 54, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, K.; Szczepańska, J.; Starzonek, S.; Woźniak, Ł.; Trych, U.; Skąpska, S.; Rzoska, S.; Saraiva, J.A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J. Enzyme inactivation and evaluation of physicochemical properties, sugar and phenolic profile changes in cloudy apple juices after high pressure processing, and subsequent refrigerated storage. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jalao, I.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; De Ancos, B. Effect of high-pressure processing on flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acids, dihydrochalcones and antioxidant activity of apple “Golden delicious” from different geographical origin. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 51, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Hernández, E.; Alves, M.; Moreira, N.; Lima, V.; Pinto, C.A.; Saraiva, J.A. Effects of Equivalent Processing Conditions for Microbial Inactivation by Innovative Nonthermal Technologies on the Safety, Quality, and Shelf-Life of Reineta Parda Apple Puree. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donda Zbinden, M.; Schmidt, M.; Vignatti, C.I.; Pirovani, M.; Böhm, V. High-Pressure Processing of Fruit Smoothies enriched with dietary fiber from carrot discards: Effects on the contents and bio-accessibilities of carotenoids and Vitamin E. Molecules 2024, 29, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xie, X.; Xu, C. An innovative approach to improve the taste, quality, and shelf life of aronia berry juice by integrating food ingredient technology with high-pressure processing (HPP) technology. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Lu, L.-X.; Koutsimanis, G.; Ge, C.; Johnson, D.P. Research on the high hydrostatic pressure and microwave combined inactivation process and the application to boiled bamboo shoots. J. Food Saf. 2019, 39, e12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieder, M.; Silva, E.K.; Mekala, S.; Meireles, M.A.A. Barley-Based Non-dairy Alternative Milk: Stabilization Mechanism, Protein Solubility, Physicochemical Properties, and Kinetic Stability. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chai, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. The impact of n2-assisted high-pressure processing on the microorganisms and quality indices of fresh-cut bell peppers. Foods 2021, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, E.; Yadav, S.; Stübler, A.-S.; Juadjur, A.; Heinz, V.; Aganovic, K. Impact of alternative and thermal preservation on microbiological, enzymatical, and chemical properties of blackcurrant juice. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2553–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trych, U.; Buniowska, M.; Skaspa, S.; Starzonek, S.; Marszałek, K. The bioaccessibility of antioxidants in blackcurrant puree after high hydrostatic pressure treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitimea-Cantúa, G.V.; Rico-Alderete, I.A.; Rostro-Alanís, M.D.J.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Escobedo-Avellaneda, Z.J.; Soto-Caballero, M.C. Effect of High Hydrostatic Pressure and Pulsed Electric Fields Processes on Microbial Safety and Quality of Black/Red Raspberry Juice. Foods 2022, 11, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Ning, N.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Xing, Y.; Che, Z. Comparison of high-pressure processing, ultrasound and heat treatments on the qualities of a gallic acid copigmented blueberry–grape–pineapple–cantaloupe juice blend. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2022, 57, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, A.; Chew, D.X.; Ghate, V.; Zhou, W. Residual polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase activities in high pressure processed bok choy (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) juice did not accelerate nutrient degradation during storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 84, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Shyu, Y.; Wu, S. Evaluating the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of broccoli treated with high hydrostatic pressure in cell models. Foods 2021, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, C.; Zeng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Yao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Z. Mechanism of colour change of carambola puree by high pressure processing and its effect on flavour and physicochemical properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 56, 5853–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosavi, N.S.; Salvi, D.; Karwe, M.V. High pressure-assisted infusion of calcium into baby carrots part II: Influence of process variables on β-carotene extraction and color of the baby carrots. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2019, 12, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinco, C.M.; Szczepańska, J.; Marszałek, K.; Pinto, C.A.; Inácio, R.S.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Effect of high-pressure processing on carotenoids profile, colour, microbial and enzymatic stability of cloudy carrot juice. Food Chem. 2019, 299, 125112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, J.; Barba, F.J.; Skąpska, S.; Marszałek, K. High pressure processing of carrot juice: Effect of static and multi-pulsed pressure on the polyphenolic profile, oxidoreductases activity and colour. Food Chem. 2020, 307, 125549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Chien, H.; Lee, Y.; Lin, C.; Hsiao, Y.; Kuo, C.; Yen, F.; Tsai, Y. Effect of high-pressure processing on the qualities of carrot juice during cold storage. Foods 2023, 12, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, P.R.; Boulet, C.; Yildiz, S.; Sablani, S.; Tang, J.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure on microbial inactivation and quality changes in carrot-orange juice blends at varying pH. LWT 2022, 159, 113219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.A.; Finnseth, C.; Skipnes, D.; Rode, T.M. Impact of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Selected Quality and Nutritional Parameters of Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. Botrytis). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Shahbaz, H.M.; Saeed, K.; Iqbal, S.; Rehman, H. Comparative evaluation of high pressure processing and thermal pasteurisation on phytochemicals, microbial and sensorial attributes of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) juice. Czech J. Food Sci. 2024, 42, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Hernández, E.; Pinto, C.A.; Abrunhosa, L.; Teixeira, J.A.; Saraiva, J.A. Hydrothermal and high-pressure processing of chestnuts—Dependence on the storage conditions. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salar, F.J.; Periago, P.M.; Agulló, V.; García-Viguera, C.; Fernández, P.S. High hydrostatic pressure vs. Thermal pasteurization: The effect on the bioactive compound profile of a citrus maqui beverage. Foods 2021, 10, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilla, A.; Rodrigo, M.J.; De Ancos, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Cano, M.P.; Zacarías, L.; Barberá, R.; Alegría, A. Impact of high-pressure processing on the stability and bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds in clementine mandarin juice and its cytoprotective effect on caco-2 cells. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 8951–8962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.B.P.; Buvaneswaran, M.; Anto, A.M.; Sinija, V.R. High-pressure processing for inactivation of enzymes, microbes, and its effect on nutritional composition of tender coconut water. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, G.; Stübler, A.-S.; Aganovic, K.; Dräger, G.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Capanoglu, E. Retention of polyphenols and vitamin C in cranberrybush purée (Viburnum opulus) by means of non-thermal treatments. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 129918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Rao, P.S. Thermal assisted high-pressure processing of Indian gooseberry (Embilica officinalis L.) juiceImpact on colour and nutritional attributes. LWT 2019, 99, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Padilla-Zakour, O.I. Evaluation of pulsed electric field and high-pressure processing on the overall quality of refrigerated Concord grape juice. LWT 2024, 198, 116002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanoglu, S.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Tang, Z.; Liu, F.; Sablani, S.S.; Zhu, M.-J.; Tang, J. Qualities of High Pressure and Microwave-Assisted Thermally Pasteurized Ready-to-Eat Green Beans During Refrigerated Storage at 2 and 7 °C. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamlerst, C.; Kosum, S.; Thepouyporn, A.; Vattanakul, S.; Prangthip, P.; Promyos, N. Effects of high-pressure processing of date palm juice on the physicochemical properties. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2024, 30, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.H.S.; Nawawi, N.I.M.; Ijod, G.; Anzian, A.; Ismail-Fitry, M.A.; Ahmad, N.H.; Adzahan, N.M.; Azman, E.M. Shelf life and quality assessment of pasteurized red dragon fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus L.) purée: Comparative study of high-pressure and thermal processing. Int. Food Res. J. 2024, 31, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Vendrell-Pacheco, M.; Heskitt, B.; Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Failla, M.; Sastry, S.K.; Francis, D.M.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Kopec, R.E. Novel processing technologies as compared to thermal treatment on the bioaccessibility and caco-2 cell uptake of carotenoids from tomato and kale-based juices. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 10185–10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Ren, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Long, F. Changes in physicochemical properties and volatiles of kiwifruit pulp beverage treated with high hydrostatic pressure. Foods 2020, 9, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, D.D.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Prudencio, S.H. Effects of high pressure processing on the physicochemical and microbiological parameters, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant activity of a lemongrass-lime mixed beverage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Jia, M.; Gui, Y.; Ma, Y. Comparison of the effects of novel processing technologies and conventional thermal pasteurisation on the nutritional quality and aroma of mandarin (Citrus unshiu) juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 64, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, N.; Rao, P.S.; Mishra, H.N. Comparative analysis of thermal-assisted high pressure and thermally processed mango pulp: Influence of processing, packaging, and storage. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 24, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizondo-Montemayor, L.; Ramos-Parra, P.A.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Treviño-Saldaña, N.; Marín-Obispo, L.M.; Ibarra-Garza, I.P.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Del Follo-Martínez, A.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Hernández-Brenes, C. High hydrostatic pressure stabilized micronutrients and shifted dietary fibers, from insoluble to soluble, producing a low-glycemic index mango pulp. CYTA-J. Food 2020, 18, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dars, A.G.; Hu, K.; Liu, Q.; Abbas, A.; Xie, B.; Sun, Z. Effect of Thermo-Sonication and Ultra-High Pressure on the Quality and Phenolic Profile of Mango Juice. Foods 2019, 8, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Cai, S.; Hu, X.; Yi, J. Evaluation of quality changes of differently formulated cloudy mixed juices during refrigerated storage after high pressure processing. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ancos, B.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Cano, M.P.; Zacarías, L. Effect of high-pressure processing applied as pretreatment on carotenoids, flavonoids and vitamin C in juice of the sweet oranges ‘Navel’ and the red-fleshed ‘Cara Cara’. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuonwu, J.C.; Leadley, C.; Bosman, A.; Tassou, S.A. High-pressure processing, microwave, ohmic, and conventional thermal pasteurization: Quality aspects and energy economics. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.N.; Lourenço, S.; Fidalgo, L.G.; Santos, S.A.O.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Jerónimo, E.; Saraiva, J.A. Long-Term Effect on Bioactive Components and Antioxidant Activity of Thermal and High-Pressure Pasteurization of Orange Juice. Molecules 2018, 23, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhao, L. Effects of Ultra-high Pressure and High Temperature Short-time Sterilization on the Quality of NFC Orange Juice. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2021, 42, 1–8, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Dhenge, R.; Langialonga, P.; Alinovi, M.; Lolli, V.; Aldini, A.; Rinaldi, M. Evaluation of quality parameters of orange juice stabilized by two thermal treatments (helical heat exchanger and ohmic heating) and non-thermal (high-pressure processing). Food Control 2022, 141, 109150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambreen, S.; Arshad, M.U.; Imran, A.; Afzaal, M.; Madilo, F.K. A comparative study of high-pressure processing and thermal processing techniques on characteristics and microbial evaluation of orange juice. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 3214–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzbach, L.; Stolle, R.; Anheuser, K.; Herdegen, V.; Schieber, A.; Weber, F. Impact of different pasteurization techniques and subsequent ultrasonication on the in vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids in valencia orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) juice. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.K.; Arruda, H.S.; Mekala, S.; Pastore, G.M.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Saldaña, M.D.A. Xylooligosaccharides and their chemical stability under high-pressure processing combined with heat treatment. Food Hydrocolloid 2022, 124, 107167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Parra, P.A.; Hernández-Brenes, C.; Díaz de la Garza, R.I. High Hydrostatic Pressure Modulates the Folate and Ascorbic Acid Accumulation in Papaya (Carica papaya cv. Maradol) Fruit. Food Eng. Rev. 2021, 13, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cayuela, T.; Quiles, A.; Hernando, I.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cano, M.P.; Ramos-Parra, P.A. Changes in bioactive compounds and microstructure in persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) treated by high hydrostatic pressures during cold storage. J. Food Process. Pres. 2018, 123, 538–549. [Google Scholar]

- Kundukulangara Pulissery, S.; Kallahalli Boregowda, S.; Suseela, S.; Jaganath, B. A comparative study on the textural and nutritional profile of high pressure and minimally processed pineapple. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 3734–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Cheng, F.; Yi, J.; Cai, S.; Liao, X.; Lao, F.; Zhou, L. Effect of high-pressure processing and thermal treatments on color and in vitro bioaccessibility of anthocyanin and antioxidants in cloudy pomegranate juice. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairone, F.; Cesa, S.; Arpante, I.; Di Simone, S.C.; Mendez, A.H.; Ferrante, C.; Menghini, L.; Filippi, A.; Fraschetti, C.; Zengin, G.; et al. Pomegranate juices: Analytical and bio-toxicological comparison of pasteurization and high-pressure processing in the development of healthy products. Foods 2025, 14, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroce, A.; Nicosia, C.; Licciardello, F. Evaluation of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) for the Stabilization of Prickly Pear Puree through the Assessment of Its Microbiological, Enzymatic, and Nutritional Features. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 2614–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhenge, R.; Rinaldi, M.; Ferrarese, I.; Paciulli, M.; Lacey, K.L.; Ganino, T.; Dall’Acqua, S. High-pressure processing of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata ex Poir. Cv. Violina) cubes: Effect of pressure level and time combinations on quality parameters. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Jike, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Xu, K.; Li, B.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Phytochemicals, antioxidant capacities and volatile compounds changes in fermented spicy Chinese cabbage sauces treated by thermal and non-thermal technologies. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škegro, M.; Putnik, P.; Kovacevic, D.B.; Kovac, A.P.; Salkic, L.; Canak, I.; Frece, J.; Zavadlav, S.; Ježek, D. Chemometric comparison of high-pressure processing and thermal pasteurization: The nutritive, sensory, and microbial quality of smoothies. Foods 2021, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Tejedor, G.; Garre, A.; Egea, J.A.; Aznar, A.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Fernández, P.S. Application of High Hydrostatic Pressure in fresh purple smoothie: Microbial inactivation kinetic modelling and qualitative studies. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2023, 29, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandim, F.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Pinto, C.A.; Heleno, S.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Dias, M.I.; Saraiva, J.A.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barros, L.; et al. Novel cold and thermally pasteurized cardoon-enriched functional smoothie formulations: A zero-waste manufacturing approach. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 139945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matías, C.; Ludwig, I.A.; Cid, C.; Sáiz-Abajo, M.-J.; De Peña, M.-P. Exploring optimal high-pressure processing conditions on a (poly)phenol-rich smoothie through response surface methodology. LWT 2024, 206, 116595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.C.; Volpe, S.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Torrieri, E.; Verardo, V. Impact of blanching and high hydrostatic pressure combined treatments on the physical-chemical and microbiological properties and bioactive-compound profile of an industrial strawberry smoothie. LWT 2024, 206, 116612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Picouet, P.; Jofré, A.; Bañón, S.; Ros, J.M. Shelf-life extension of multi-vegetables smoothies by high pressure processing compared with thermal treatment. Part II: Retention of selected nutrients and sensory quality. J. Food Process Pres. 2019, 43, e14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A.; Dolors Guàrdia, M.; Picouet, P.; Jofré, A.; Bañón, S.; Ros, J.M. Shelf-life extension of multi-vegetables smoothies by high-pressure processing compared with thermal treatment. Part I: Microbial and enzyme inhibition, antioxidant status, and physical stability. J. Food Process Pres. 2019, 43, e14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.C.; Queirós, R.P.; Inácio, R.S.; Pinto, C.A.; Casal, S.; Delgadillo, I.; Saraiva, J.A. High-Pressure Processing Effects on Microbiological Stability, Physicochemical Properties, and Volatile Profile of a Fruit Salad. Foods 2024, 13, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. High pressure processing for sea buckthorn juice with higher superoxide dismutase activity. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 57, 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Sevenich, R.; Gratz, M.; Hradecka, B.; Fauster, T.; Teufl, T.; Schottroff, F.; Chytilova, L.S.; Hurkova, K.; Tomaniova, M.; Hajslova, J.; et al. Differentiation of sea buckthorn syrups processed by high pressure, pulsed electric fields, ohmic heating, and thermal pasteurization based on quality evaluation and chemical fingerprinting. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 912824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemariam, H.W.; Emire, S.A.; Teshome, P.G.; Töpfl, S.; Aganovic, K. Microbial inactivation and quality impact assessment of red pepper paste treated by high pressure processing. Helyon 2022, 8, e12441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, A.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Böhm, V. Effects of high pressure processing on bioactive compounds in spinach and rosehip puree. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, H.; Murray, H.; Hofsommer, M.; Barreto, A.M.; Pavon-Vargas, D.; Puzovic, A.; Gędas, A.; Rincon, S.; Gössinger, M.; Slatnar, A. Comparing the impact of conventional and non-conventional processing technologies on water-soluble vitamins and color in strawberry nectar–a pilot scale study. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaby, K.; Grimsbo, I.H.; Hovda, M.B.; Rode, T.M. Effect of high pressure and thermal processing on shelf life and quality of strawberry purée and juice. Food Chem. 2018, 26, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suprabha Raj, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Rao, P.S. Optimizing the thermal assisted high-pressure process parameters for a sugarcane based mixed beverage using response surface methodology. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, P.; Jayachandran, L.E.; Rao, P.S. Browning and bioactive composition of sugarcane juice (Saccharum officinarum) as affected by high hydrostatic pressure processing. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, P.; Jayachandran, L.E.; Rao, P.S. Application of high-pressure processing for extending the shelf life of sugarcane juice under refrigerated conditions. J. Food Process Pres. 2020, 44, e14957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Zhu, F. Physicochemical properties and bioactive compounds of different varieties of sweetpotato flour treated with high hydrostatic pressure. Food Chem. 2019, 299, 125129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Zainixi, L.; Saisai, W.; Hui, S. Effect of ultra-high pressure technology on isomerization and antioxidant activity of lycopene in Solanum lycopersicum. Am. J. Biochem. Biotech. 2020, 16, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Bai, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C. Effect of Storage Time on Qualities of High Pressure Treated Fresh Tomato Juice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.; Daood, H.; Friedrich, L.; Hitka, G.; Helyes, L. Monitoring, by high-performance liquid chromatography, near-infrared spectroscopy, and color measurement, of phytonutrients in tomato juice subjected to thermal processing and high hydrostatic pressure. J. Food Process Pres. 2021, 45, e15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo-Orozco, C.; Tarazona-Díaz, M.P.; Rodríguez, L.I. Formulation of a tropical beverage by applying heat treatment and high hydrostatic pressure. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 58, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Popović, V.; Koutchma, T.; Warriner, K.; Zhu, Y. Effect of thermal, high hydrostatic pressure, and ultraviolet-C processing on the microbial inactivation, vitamins, chlorophyll, antioxidants, enzyme activity, and color of wheatgrass juice. J. Food Process. Eng. 2020, 43, e13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Yi, J. Effect of processing technologies and storage conditions on quality changes in acidified Xiaomila. Food Ferm Ind. 2024, 50, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, F. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure treatment on antioxidant bioaccessibility from tomato juice and its modulation of gut microbiota. Food Chem. 2025, 488, 144839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Hopfhauer, S.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Böhm, V. High-Pressure Processing of Kale: Effects on the Extractability, In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids & Vitamin E and the Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.F.; Butz, P.; Tauscher, B. Effects of high--pressure processing on carotenoid extractability, antioxidant activity, glucose diffusion, and water binding of tomato puree (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, M.C.; Anese, M.; Parpinel, M. Influence of processing on the antioxidant properties of fruit and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Techol 1999, 10, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevers, C.; Falkowski, M.; Tabart, J.; Defraigne, J.O.; Dommes, J.; Pincemail, J. Evolution of antioxidant capacity during storage of selected fruits and vegetables. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8596–8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, N.; Kalisz, S.; Kruszewski, B. High-Temperature Short-Time and Ultra-High-Temperature Processing of Juices, Nectars and Beverages: Influences on Enzyme, Microbial Inactivation and Retention of Bioactive Compounds. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| F&V Product | Method | Processing Conditions | Vitamin C | Carotenoids | Antioxidant Activity (AA) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Açai juice | HPP | 400–600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 min | NP | NP | No changes at 400 MPa, ↑ 22.4% at 500 MPa (ORAC) | [108] |

| TP | 85 °C, 1 min | ↓ 8.2% (ORAC) | ||||

| Apple juice | HPP | 600 MPa, RT, 3 min | NP | NP | No differences in DPPH TPC ↑ in HPP samples | [109] |

| HPP | 300 MPa (3 pulses)-600 MPa (1 pulse), 5–15 min, 22 °C 84 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 5–31% compared to untreated ↓ >99% after storage | NP | NP | [110] | |

| HPP | 400 MPa, RT, 3 min 21 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 14% ↓ 79% after storage | NP | NP | [111] | |

| HPP | 600 MPa, 25 °C, 5 min | No significant differences between HPP and control | NP | NP | [112] | |

| Apple pieces | HPP | 400, 500, 600 MPa, 35 °C, 5 min | NP | NP | ↑ 26.2% (DPPH), ↑ 16.1% (ABTS), and ↑ 11.8% (FRAP) | [113] |

| Apple puree | HPP | 200–500 MPa, 17 °C, 1 min | ↑ 66.7% (DPPH), ↑ 58.8% (ABTS) | [114] | ||

| TP | 72 °C, 15 s | ↓ 4.2% (DPPH) and ↓ 3.7% (ABTS) | ||||

| Apple, orange, and banana smoothies | HPP | 450 MPa, 3 min, 11 °C 28 days storage, 4 °C | NP | ↑ 40–48% No changes in Zeaxanthin; ↑ provitamin A | [115] | |

| Aronia berry juice | HPP | 600 MPa, RT, 5 min 12 months storage, 4 °C | NP | NP | No changes TPC, DPPH, FRAP TPC ↓ 17–24% and ↓ 6–12% in AA | [116] |

| Bamboo shoots | HPP | 378 MPa, RT, 3 min | ↓ 7.0% | NP | NP | [117] |

| Barley-based non-dairy milk | HPP | 100, 300 MPa; 40 °C; 2 min | NP | ↓ 0–34% | ↓ 38–45% (FRAP) | [118] |

| 3 pulses | ↓ 10–21% (DPPH) | |||||

| 600 MPa; 40 °C; 2 min | ↓ 10% | ↓ 45% (FRAP), ↓ 20%(DPPH) | ||||

| 100, 300 MPa; 80 °C; 2 min | ↓ 23–70% | ↓ 47–58% (FRAP) | ||||

| 3 pulses | ↓ 30–34% (DPPH) | |||||

| PATP | 600 MPa; 80 °C; 2 min | ↓ 40% | ↓ 54% (FRAP), ↓ 19%(DPPH) | |||

| Bell peppers (fresh cut) | HPP | 400, 500 MPa, 25 °C, 1–7.5 min 25 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 21–19% ↓ 30–36% during storage | NP | ↑ 7–9% TPC and ↑ 14% AA ↓ 30.3–57.4% (DPPH) and ↓ 10.6–58.6% (FRAP) after storage | [119] |

| Blackcurrant juice | HPP | 400 MPa, 18 °C, 1 min | ↑ 3.3% | NP | ↓ 6% in TPC, | [120] |

| TP | 74 °C, 3 s | No modifications | ↑ 7% in TPC | |||

| 42 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ similarly (HPP, TP) | ↓ 20% (HPP) and no losses (TP) | ||||

| Blackcurrant purée | HPP | 200–600 MPa, RT, 5 min | Bioaccessibility ↑ using HPP | NP | Slightly ↑ AA (ABTS) and maintained (DPPH) | [121] |

| TP | 85 °C, 10 min | |||||

| Black/Red raspberry juice | HPP | 400–600 MPa, 27–31 °C, 2–10 min | ↑ 11–67% in comparison with the untreated | NP | NP | [122] |

| Blueberry–grape–pineapple–cantaloupe juice blend | HPP | 550 MPa, 25 °C, 5 min | ↓ 12% (day 48) | NP | NP | [123] |

| TP | 90 °C, 3 min | ↓ 9% (day 48) | ||||

| 72 days of storage | ↓ 23% (HPP) and ↓ 11% (TP) | |||||

| Bok choy | HPP | 600 MPa; 5 °C; 2.5–20 min | No changes | ↓ 22.2–32.1% | No changes (TPC) | [124] |

| TP | 95 °C; 0.5 min | ↓ 2.5% | ↓ 70.4% | |||

| Broccoli | HPP | 200–600 MPa, 3–15 min | No changes | NP | ↑ 54% (TPC) | [125] |

| Carambola puree | HPP | 200–800 MPa, 25 °C, 15 min | NP | NP | ↑ 2–3.3%(DPPH) 1.5% up to 3.2% ↑ (Hydroxyl radical) | [126] |

| Baby carrots | HPP | 550 MPa, 5 min, 15 °C | NP | ↑ 300% | NP | [127] |

| Carrot juice | HPP | 300 MPa (3 cycles); 450, 600 MPa, RT, 5 min | NP | ↓ 26–41% | [128] | |

| HPP | 450, 600 MPa; 5 min, RT 300 MPa, 5 min (3 pulses) 84 days storage, 4 °C | NP | NP | ↑ up to 48.8% (DPPH) ↑ up to 10.9% (ABTS) ↑ during storage | [129] | |

| HPP | 600 MPa, 3 min, 20 °C | NP | ↑ 19% | ↓ 53% TPC; No changes (DPPH) | [130] | |

| TP | 85 °C, 60 s | ↓ 31% | ↑ 45% TPC; ↑ 65% DPPH | |||

| 15 days storage, 4 °C | ↑ 18% HPP and | ↓ 53% HPP and ↑ 45% TP (TPC) | ||||

| ↑ 13% TP | ↓ 36% HPP and ↑ 22% TP (TPC) | |||||

| Carrot-orange juice blends | HPP | 200, 300, and 400 MPa, 20 °C, 1–5 min | No changes between untreated and HPP | NP | NP | [131] |

| Cauliflower | HPP | 400 and 600 MPa, RT, 2 and 5 min 28 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 3% ↓ between 11% (14 days)-18% (28 days) | NP | NP | [132] |

| Cherry juice | HPP | 400, 600 MPa, RT, 5 min | NP | NP | ↓ 6.9–13.9% (TPC); 3.7–5.1% (DPPH) | [133] |

| TP | 95 °C, 30 s | ↓ 5.7% (TPC), ↓ 48.3% (DPPH) | ||||

| 60 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ up to 23% (TPC), ↓ 70.1% (DPPH) | |||||

| Chestnut | HPP | 400–600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 min | ↓ 0.5–2.2% | NP | NP | [134] |

| TP | 50 °C for 45 min | ↓ 5.2% | ||||

| Citrus Maqui beverage | HPP | 450 and 600 MPa, 20 °C, 3 min | ↓ 45% and ↓ 31% | NP | NP | [135] |

| TP | 85 °C, 15 s | ↓ 28% | ||||

| Clementine-mandarin juice | HPP | 400 MPa, 40 °C, 1 min | ↓ 15% | ↓ 30% | ↑ 25% TPC; ↑ 2% DPPH; ↓ 9.7% ABTS; ↓ 10% FRAP | [136] |

| Coconut water | HPP | 350–550 MPa, RT, 3–7 min | ↓ up to 7.8% | NP | ↓ after HPP | [137] |

| Cranberry bush purée | HPP | 200–600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 or 15 min | ↓ 10–23% | NP | No differences (DPPH) Very slight ↓ (CUPRAC) | [138] |

| Gooseberry juice | HPP-PATP | 200–500 MPa, 30–60 °C, 5–20 min | ↓ 0.3–15% | NP | ↓ 12% (60 °C) ↓ 28% (50 °C) | [139] |

| TP | 60 °C, 5–20 min | ↓ <34% | ||||

| Grape juice | HPP | 600 MPa, 5 °C, 3 min 5 months storage, 4 °C | NP | NP | No differences in TPC, DPPH, ABTS ↓ TPC, no changes in AA during storage | [140] |

| Green beans | HPP | 600 MPa, 25 °C, 10 min | ↓ 70% | NP | NP | [141] |

| MW-TP | 72 °C, 3 min | ↓ 35% | ||||

| Date palm juice | HPP | 400, 600 MPa, 25 °C, 10 min | NP | NP | ↓ ~18% in TPC (TP) compared to raw and HPP | [142] |

| TP | 100 °C, 1 min | ↓ 2.6%, 21.5%, 8.5%, and 31.3% for DPPH, FRAP, ABTS, and ORAC compared to control and lower in HPP | ||||

| Dragon fruit puree | HPP | 350 MPa, 25 °C, 5 min | NP | NP | ↓ 6% in TPC, ↓ 7% (DPPH), and 4%(FRAP) | [143] |

| TP | 65 °C, 20 min | ↓ 17%(DPPH) and 9%(FRAP) | ||||

| 60 days storage, 4 °C | ↑ 29% TP than in HPP after storage | |||||

| Kale juice | HPP | 600 MPa; RT; 5, 10, 20, 40 min | NP | ↑ up to 22% | ↑ up to 166% (ABTS) | [107] |

| TP | 80 °C; 5, 10, 20, 40 min | ↓ 38% (TP) | ↑ up to 150% (L-ORAC) | |||

| 60 days storage, 5 °C | ↓ 31% (TP | ↓ ~50% (ABTS) and ↑ ~20% (L-ORAC) | ||||

| ↓ 67% (HPP) | ↓ ~22% (ABTS) and ↑ ~20% (L-ORAC) | |||||

| HPP | 500 MPa, RT, 3 min | NP | ↑ lutein | [144] | ||

| TP | 90 °C, 30 s | ↓ β-carotene ↓ 12% carotenoids | ||||

| Kiwifruit pulp beverage | HPP | 400–600 MPa, RT, 5–15 min | ↑ 35.8% (400 MPa, 15 min) | NP | NP | [145] |

| TP | 85 °C, 10 min | compared to TP | ||||

| 40 days storage, 4 °C | Significant ↓ after storage in TP, better retention with HPP | |||||

| Lemongrass-lime mixed beverage | HPP | 200–400 MPa, 25 °C, 1–2 min | No changes | NP | HPP and untreated have ↑ AA than TT | [146] |

| TP | 71.1 °C, 3 s | ↓ 21% | ||||

| Mandarin juice | HPP | 600 MPa, 4 °C, 30 s | ↓ 8.2% | ↓ 10.7% | ↓ 29% TPC; | [147] |

| TP | 90 °C, 30 s | ↓ 11.7% | ↓ 41% | ↓ 49.6% TPC | ||

| Mango pulp | PATP | 600 MPa, 52 °C, 10 min | ↓ 5.0% | NP | NP | [148] |

| HPP | 592 MPa, 25 °C, 3 min | No significant difference compared with the control | NP | NP | [149] | |

| Mango juice | HPP | 400 MPa, RT, 10 min | ↓ 2.8% | NP | ↓ 4.2% | [150] |

| Mixed fruit juices (2 formulations) | HPP | 550 MPa, RT, 5 min 90 days storage, 4 °C | ↑ 21–35% ↓ 23–58% | No changes | NP | [151] |

| Orange juices from Navel and Cara Cara varieties | HPP | 200 and 400 MPa, 25° and 40 °C, 1 min | Navel: ↓ 2–30% | Navel: ↓ up to 34.1% | Navel: ↓ AA (11–26%) | [152] |

| Cara Cara: ↓ 0.1–9% | Cara Cara: ↓ up to 20.1% | Cara Cara: ↑ AA (7–13%) at 200 MPa and ↓ AA (11–14%) at 400 MPa | ||||

| Orange juice | HPP | 600 MPa, 30 °C, 3 min | No significant difference between HPP and control | NP | NP | [153] |

| HPP | 550 MPa, 18 °C, 70 s | NP | ↓ 12% | ↓ 13% | [154] | |

| TP | 70 °C, 30 s | ↓ 20% | ↓ 26% | |||

| 36 days storage, 4 °C | HPP maintained ↑ than TP | Maintained ↑ than TP after storage | ||||

| HPP | 600 MPa, RT, 11 min | No significant difference | NP | ↑ TPC, AA (DPPH and FRAP) ↑ in HPP | [155] | |

| TP | 110 °C, 8.6 s | ↓ content | ||||

| HPP | 550 MPa, 15 °C, 1.5 min | ↑ 7% | NP | ↓ 2.7% | [156] | |

| TP | 72 °C, 20 s | ↓ 7% | ↓ 13% | |||

| HPP | 400, 600 MPa, RT, 3.6 min | No changes | ↑ up to 74% | No changes (TPC) | [157] | |

| TP | 85 °C, 45 s | ↓ 4% | ↓ 12% | No changes (TPC) | ||

| 60 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 18% HPP and 16% TP | ↑ up to 74% HPP | ↓ 13% HPP | |||

| ↓ 22% TP | ↓ 30% TP | |||||

| HPP | 600 MPa, 24 °C, 3 min | ↓ 5.3% | No differences | [158] | ||

| TP1 | 74 °C, 30 s | ↓ 3.8% | No differences | |||

| TP2 | 92 °C, 31 s | ↓ 2.6% | ↓ 13.6% | |||

| Orange juice enriched with XOS | HPP-PATP | 100–600 MPa, 30–100 °C, 3 min (experimental design) | ↑ 8% increase up to ↓ 37% | NP | NP | [159] |

| Papaya cubes | HPP | 50–400 MPa, 20 °C, 3–60 min | ↑ 4–28% | NP | NP | [160] |

| Persimmon | HPP | 200 MPa; 25 °C; 3, 6 min | NP | ↑ 23–28% and | ↓ 25–30% (DPPH) | [161] |

| 28 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 30–38% after storage | ↓ ~80% after storage | ||||

| Pineapple pieces | HPP | 100–300 MPa, RT, 5–20 min | ↑ 10–40% | NP | ↓ 0.4–↑ 13% in TPC | [162] |

| 16 days storage, 4 °C | ↑ 17% raw and 10% (HPP) | ↓ ~5% in TPC after storage | ||||

| Pomegranate juice | HPP | 350, 450, 550 MPa; 23 °C; 1, 3, 5 min | Not significant ↓ | NP | No significant effect (DPPH and ABTS) | [163] |

| TP1 | 85 °C, 30 s | ↓ 48% | ↓ 24% (ABTS/DPPH) | |||

| TP2 | 110 °C, 30 s | ↓ 60% | ↓ 61% (ABTS/DPPH) | |||

| HPP | Not provided | ↓ 35% | NP | ↓ 28% TPC; ↓ 36% DPPH; ↓ 44% ABTS; ↓ 36% CUPRAC; ↓ 36% FRAP; ↓ 61% Chelating EDTA | [164] | |

| Prickly pear puree | HPP | 600 MPa, 5 °C, 180 s | ↓ 2% | NP | ↑ 21% (HPP) and no change (TP) | [165] |

| TP | 80 °C, 30 s | ↓ 23% | ↓ 35% AA (TP) | |||

| 42 days storage, 4 °C | No changes (HPP) | Maintain TPC, AA during storage (HPP) | ||||

| Pumpkin cubes | HPP | 200–600 MPa, 20 °C, 1–5 min | NP | ↑ 40–56.9% | ↑ AA (DPPH) | [166] |

| Chinese cabbage Sauce | HPP | 200–600 MPa, 25 °C, 8 min | NP | No changes | ↑ ~3% or no changes in TPC (HPP) and | [167] |

| TP1 | 75 °C, 30 min | ↓ ~6% | ↑ 2.2% (DPPH) and FRAP (16.1%) (HPP) | |||

| Slightly ↑ AA (TP1) | ||||||

| TP2 | 110 °C, 15 min | ↓ ~12% | ↑ ~2% TPC and no changes (TP2) | |||

| Smoothies | HPP | 350–450 MPa, 20 °C, 5–15 min (experimental design) | HPP provided a better retention compared to TP | No differences compared to TP | [168] | |

| TP | 85 °C, 7 min | ↓ 66% TP after storage | ↓ 30.7% TP after storage | TPC ↓ in TP | ||

| 21 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 18% HPP after storage | TPC ↓ 9.8% after storage | ||||

| Fresh purple smoothie | HPP | 300–450 MPa, 20 °C, 11–4 min | ↓ 21–26% | NP | NP | [169] |

| Functional smoothie | HPP | 550 MPa, 15 °C, 3 min | NP | NP | No modifications or ↑ AA (TBARS) | [170] |

| TP | 90 °C, 30 s | Phenolics and AA ↓ with storage | ||||

| 50 days storage, 4 °C | ||||||

| Green smoothie | HPP | 300–600 MPa, RT, 2–10 min | NP | NP | No changes in TPC and AA | [171] |

| Strawberry smoothie | HPP | 600 MPa, 4 °C, 3 min | ↑ 15% | NP | ↑ 12% (DPPH, ABTS) | [172] |

| Vegetable smoothie with apple | HPP | 300 MPa, 10 °C, 5 min | ↓ 28% | NP | NP | [173] |

| 28 days storage, 4 °C | Total ↓ after storage | |||||

| HPP | 350 MPa, 10 °C, 5 min | NP | NP | ↑ TP (FRAP) | [174] | |

| TP | 85 °C, 7 min | |||||

| Fruit salad | HPP | 550 MPa, 15 °C, 3 min | NP | NP | No significant differences (ABTS) | [175] |

| 35 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ AA after storage | |||||

| Sea buckthorn juice | HPP | 500 MPa, RT, 6 min | No significant differences between HPP and untreated | [176] | ||

| TP | 100 °C, 15 s | ↓ 14.3% | ↓ 20.5% | ↓ between 3.8–3.4% (DPPH and FRAP) | ||

| Sea buckthorn syrups | HPP | 600 MPa; 4, 8 min | No significant differences between HPP and heated samples during storage | [177] | ||

| TP | 88 °C; 15 s (hot filling) | |||||

| 56 days storage, 4 °C | ||||||

| Red pepper paste | HPP | 100–600 MPa; RT; 0.5–10 min (experimental design) | NP | ↑ 2.5% | ↑ 2.9% (ABTS) | [178] |

| Spinach and rosehip puree | HPP | 200, 400, 600 MPa; RT; 5 and 10 min | NP | ↑ 22.9% | Not significant effect: Slightly ↑ (ABTS) Slightly ↓ (ORAC) | [179] |

| Strawberry nectar | HPP | 600 MPa; 5 min | ↓ 25% | NP | NP | [180] |

| TP | 72 °C; 117 s | ↑ 72% | ||||

| 30 days storage, 4 °C | ↓ 100% HPP and ↓ 50% TP | |||||

| Strawberry puree and juice | HPP | 400 MPa, 20 °C, 3 min | ↑ 2.9% | NP | NP | [181] |

| 49 days storage, 6 °C | Total ↓ after storage | |||||

| Sugarcane-based mixed beverage | HPP-PATP | 400 MPa, 33 °C, 15 min | ↑ 17% | NP | More retention | [182] |

| 400 MPa, 67 °C, 15 min | ↓ 29% | ↓ ~13.2% | ||||

| (experimental design) | ||||||

| Sugarcane juice | HPP-PATP | 600 MPa, 30–60 °C, 25 min | ↓ 3.0–25% | NP | NP | [183] |

| HPP | 523 MPa, 50 °C, 11 min | ↓ 11% | NP | ↓ 12–15% | [184] | |

| TP | 90 °C, 5 min | ↓ 25% | ↓ 24–28% | |||

| Sweet potato flour | HPP | 200–600 MPa, 25 °C, 15 min (experimental design) | NP | ↑ 0–52% | ↑ 4.2–30.9% (DPPH) ↑ 1.1–22.5% (FRAP) | [185] |

| Tomato | HPP | 400, 500 MPa, 50 °C; 8, 10 min | NP | NP | HPP ↑ AA (DPPH and Hydroxyl radical) | [186] |

| Tomato juice | HPP | 400 MPa, 25 °C, 30 min | NP | NP | [187] | |

| TP | 100 °C, 5 min | |||||

| 30 days storage at 4 °C | ↓ 96% after storage (TP) | |||||

| ↓ 24% after storage (HPP) | ||||||

| HPP | 400, 600 MPa, 2–10 min | ↓ between 50–73% | NP | NP | [188] | |

| TP | 65–115 °C, 2–10 min | ↓ between 35–96% | ||||

| Tropical beverage | HPP | 500 MPa, RT, 4.2 min | The ↑ concentration appears in the HPP sample | NP | The ↑ values appear in HPP samples (DPPH and FRAP) | [189] |

| TP1 | 65 °C, 10 min | |||||

| TP2 | 75 °C, 2 min | |||||

| TP3 | 95 °C, 1 min | |||||

| Wheatgrass juice | HPP | 400–600 MPa, RT, 1–3 min | ↓ 2% (not significant) | NP | ↓ 36% TPC; ↓ 6.6% DPPH; ↓ 11.3% ORAC | [190] |

| TP | 75 °C, 15 s | ↓ 27% | ↓ 7.5% TPC; ↓ 13.2%; ↓ 35.8% ORAC | |||

| Xiaomila (Capsicum frutescens L.) | HPP | 600 MPa, RT, 5 min | NP | NP | ↓ 68% TPC | [191] |

| TP | 80 °C, 20 min | ↓ 36% TPC and ↓ 5–6.7% (DPPH-ABTS) | ||||

| 30 days storage, (25–42 °C) | ↓ 47.3–70.5% in TPC after storage | |||||

| Treatment | HPP | PATP | TP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | Best retention | Good potential, less consistent | Frequently degraded |

| Vitamin A | Often enhanced/retained | Promising, limited data | Lower retention |

| Antioxidant activity | Often enhanced or stable | Moderate to strong retention | Often reduced |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Lamela, C.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.M. Effects of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Antioxidant Vitamins (A, C, and E) and Antioxidant Activity in Fruit and Vegetable Preparations: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910699

Pérez-Lamela C, Torrado-Agrasar AM. Effects of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Antioxidant Vitamins (A, C, and E) and Antioxidant Activity in Fruit and Vegetable Preparations: A Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910699

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Lamela, Concepción, and Ana María Torrado-Agrasar. 2025. "Effects of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Antioxidant Vitamins (A, C, and E) and Antioxidant Activity in Fruit and Vegetable Preparations: A Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910699

APA StylePérez-Lamela, C., & Torrado-Agrasar, A. M. (2025). Effects of High-Pressure Processing (HPP) on Antioxidant Vitamins (A, C, and E) and Antioxidant Activity in Fruit and Vegetable Preparations: A Review. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910699