Based on the presented results, we discuss the key findings emanating from our analysis of the 32 included apps considering the four main research questions that underpin the systematic review.

4.1. Mnemonics Serious Games Available on the App Stores

Table 7 shows the key descriptive information about the 32 assessed games. Mnemonics serious games vary in terms of numerous characteristics. Regarding subject, besides the games which have a generic focus, a considerable number of them focus on using mnemonics to teach language exclusively, and the same goes for using them to teach medicine exclusively, albeit to a lesser extent. This is unsurprising, as these two subjects are very memory-intensive [

5,

12]. The games with generic focus (totalling more than one-third) tend to take a more rounded approach, either by teaching various subjects to players in turns or by not featuring any situations that have a clear subject. That said, anatomy [

48] as well as biblical verses [

73] were rarely touched on, as only one game is only concerned about each subject. Although only one game focuses on biblical verses in the current review, finding that mnemonics are also applied in learning religious content may not be surprising as mnemonics were used to memorize religious text in times of old when the printing press and/or modern technology such as computers and smartphones were not available and at our fingertips to serve as our extended memories [

77,

78].

Regarding Game Type, mnemonics serious games tend to be puzzles or quizzes, which are both common when it comes to brain training. Quite a few take a less specific approach to brain training; their methods cannot be easily classified (we listed these simply as “Cognitive”). They seldom appear as card games [

45,

53]. Regarding Mnemonic Type, the most common types are acronyms and images, which makes sense since they appear in many places. Note organization makes an occasional appearance, and both keywords and acrostics rarely appear. Regarding Purpose, it is almost split halfway between intending to formally educate individuals and serving a more casual, everyday role (which we listed as “Non-Educational”).

Regarding Price, a lot of mnemonics serious games tend to be free, but it is not uncommon for such a game to need to be bought. Non-zero prices we see range from slightly less than CAD 2 [

57,

60] to nearly CAD 13 [

62]. Regarding Age Group, almost every game is intended for ages 4 and up. Sometimes the range is stricter, occasionally being for ages 12 and up, and sometimes even being for ages 17 and up. This could be because of the high difficulty of a subject or at least part of its content, though not necessarily. However, some games are meant for all ages, and one game, Alpha-Guess [

47], has the rather unique range of ages 9 and up. Regarding Score, quite a few games do not have any ratings, but among the ones that do, they tend to have decent scores (i.e., at least 4) or mediocre ones (i.e., at least 3 and less than 4). Occasionally some games have a rather poor score [

59,

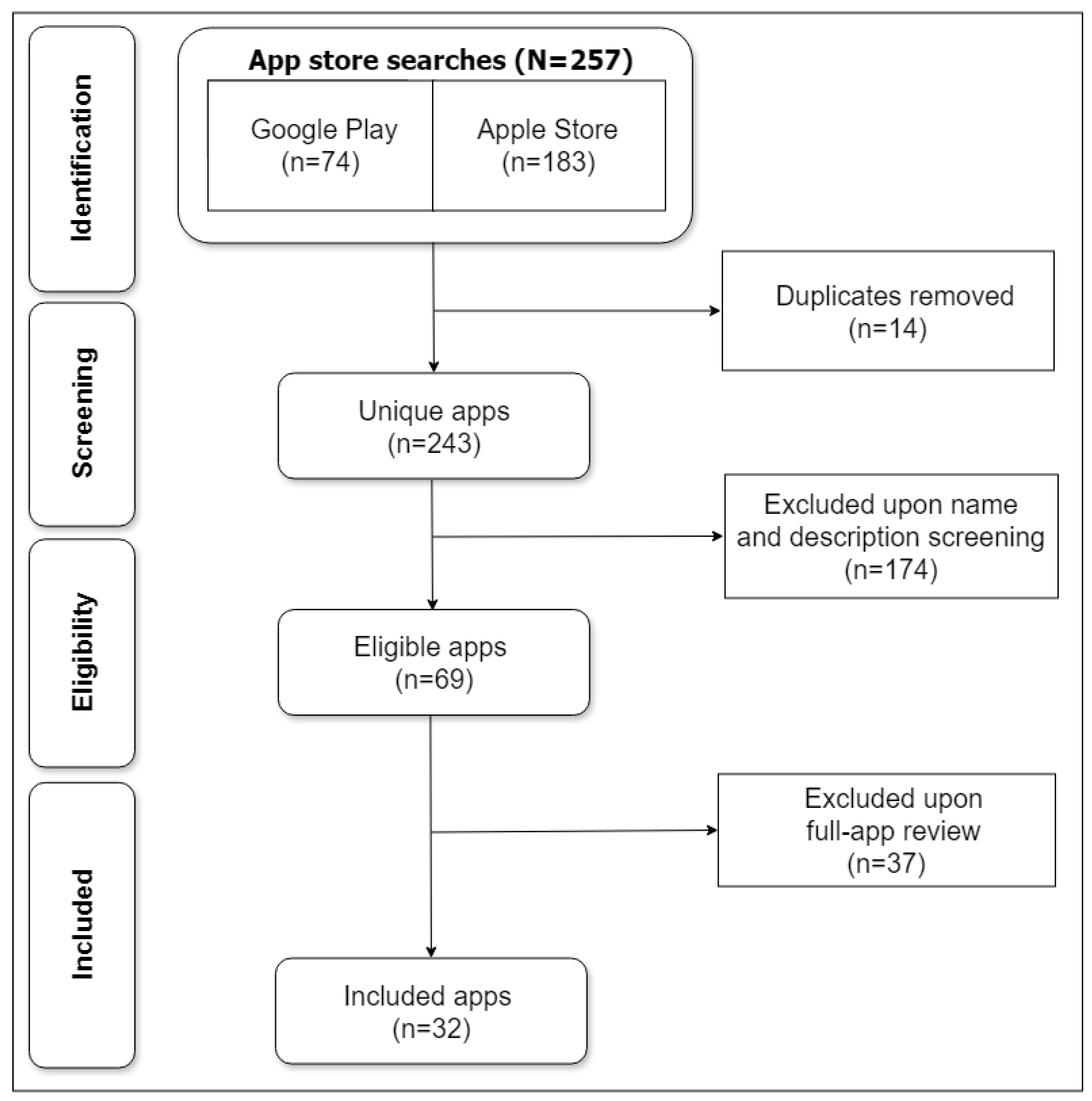

71]. Regarding Platforms, most of the mnemonics serious games we found were found on the App Store, while just a few were found on Google Play. However, as stated before, this does not imply that far fewer of these games are on Google Play, but rather that our specific search did not find them there.

4.2. Game Elements Employed in Mnemonics Serious Games on the App Stores

Here, we discuss the IN-3PACIFIC characteristics listed in

Table 8. Mentions of subjectivity are based on agreement rates and Cohen’s Kappa.

Regarding Immersion, a fair amount of mnemonics serious games (37.5%) likely succeed in giving players a feeling of being present in the game in some way. However, more of these games likely fail to do so. Even opinions on whether a particular game is immersive can slightly differ. Regarding Narrative, only a few games (18.8%) possibly give off a sense of narrative, and the apparent existence of this is highly subjective. One reason is that games without a scenario involving defined characters can still possibly treat the player as one, specifically, the star of the show; whether the player feels like they are one is open to interpretation. For example, the game “mNemo—remember as a genius!” [

61] features the player starting off presumably without knowledge of mnemonics and not doing so well at memorization, then learning mnemonics, using them in various tasks, and doing better at memorization. This could be interpreted as a first-person character on a quest to become stronger, though not everyone would think this way. Most games, however, clearly forgo any intention of a plot and simply throw tasks at the player.

Regarding Self Presence, not many mnemonics serious games (18.8%) seem to make players feel like their persona’s experiences are their own. This is usually trivially true because either players do not feel present in the game at all (i.e., no Immersion) or there seems to be no persona representing them (i.e., no Identity). However, Self Presence, like Narrative, is highly subjective; this time, it is because of the Identity characteristic, which is discussed later. Regarding Social Presence, fewer games (12.5%) involve interaction with any virtual actors, because there are no virtual actors. There is likely no subjectivity here, as it should be easy to discern whether there are virtual actors. They can be non-player characters (NPCs) or characters controlled by other players; either way, they should be recognizable. Regarding Spatial Presence, none of the games (0%) we found made players feel physically embodied in the game environment for two simple reasons: there are no opportunities to create physical avatars, and the only “environments” shown are 2D interfaces that players simply look at (which is not enough to count as physical embodiment). This should not be and is not subjective either.

Regarding Agency or Control, mnemonics serious games appear slightly more likely (62.5%) to give players sufficient ability to customize parts of the game to their liking, as opposed to not giving them this ability. Yet, this characteristic is highly subjective, as different people have different standards for what amounts of freedom are sufficient. For instance, some people might be satisfied with visual settings such as light/dark mode, while others might want gameplay settings such as difficulty adjustments. Even the degree of these settings can determine whether someone thinks they have sufficient freedom. Regarding Identity, not many of the games (18.8%) allow people to create a character or profile representing them. Surprisingly, this turns out to be more subjective than expected. One reason is that some of the games require creating an account; however, whether the account is personalized enough to count as a profile is open to interpretation. The game Memory Rx [

59] takes this further. It has a tab called “Profile”, but the only personalization feature there is the choice of mnemonics. While some might consider this enough, others might not.

Regarding Feedback, all the mnemonics games we found (100%) did indeed provide sufficient feedback, which was unsurprising given the importance and indispensability of feedback in games in particular and digital applications in general. Regarding Interactivity, all of the games (100%) allowed players to initiate and receive feedback from them as if they were entities that can be communicated with. Even the simplest of the games still managed to make players feel like they are interacting with someone rather than using a mere tool or machine. This does not seem as subjective as we anticipated; perhaps people naturally see these sufficiently advanced technologies as those to “work with” rather than “use”. Regarding Challenge, all of the games (100%) did provide players different degrees of complexity. This was to be expected of games that were meant to teach skills to players, since such games often introduce skills early on but then require mastery of them later.

4.3. Fostering of Experiential Learning by Mnemonics Serious Games on the App Stores

Here, we discuss the C-SHARP characteristics listed in

Table 9. Once again, mentions of subjectivity are based on agreement rates and Cohen’s Kappa.

Regarding the Investigation-Like category, almost none of the mnemonics serious games we found (6.25%) require players to use elements in the game’s context to solve problems. They tend to either guide players formally or leave them to their own devices but with obvious implications of what to do. One of the only two that featured this characteristic are Alpha-Guess [

47], which requires players to guess acronyms based on the category, the number of words, and the set of available letters. The other is Qualuff Puzzles [

74], which requires players to decode sentences encoded with numbers by using clues to find out which letter is associated with a particular number. Regarding the Multisolution-Based category, the only games (9.38%) that featured more than one possible solution are those where players decide the best solution among several. The three games are Acromania [

46], Rattlin’ Words [

75], and Wacronyms [

76]; these three all involve multiple players coming up with the best phrase based on an ordered set of letters (e.g. Make a phrase with the acronym LOL) and voting which phrase is the best. The other games have a clear sense of correctness with only one correct answer. Regarding Critical Reflection overall, it appears not many mnemonics serious games demonstrate parts of it, and no game demonstrates it completely.

Regarding Place, the only mnemonics serious game we found (3.13%) that definitively featured a particular location is Pondernaut [

73], which was set on the Moon. Although Alpha-Guess [

47] featured a castle, this feature was not enough to establish that the game was predicated on a medieval setting. All other games only featured rather simple interfaces, which did not represent any specific location or landmark. Regarding Time, none of the games featured a particular time period. The games that came close to featuring a time period by virtue of having certain places or landmarks include Pondernaut [

73], which featured an astronaut suit that is not specific enough, and Alpha-Guess [

47], which featured a castle. All other games only featured rather simple interfaces that do not represent any time period.

We discussed Learner Empowerment, also known as Agency or Control, in the previous subsection. Regarding Collaboration With Others, not many games (12.5%) presented this opportunity. Alpha-Guess [

47], for example, allows players to discuss with one another what a certain mnemonic in question might be, and the games that feature multiple solutions [

46,

75,

76] involve presenting acronym ideas to one another. The remaining games are exclusively single-player. Overall, though the majority of the games succeed at fostering Learner Empowerment, most fail at supporting Hands-On Activity/Participation.

Regarding Novel Experience, a slight majority of games (56.3%) tend to foster it, and even so, this is a subjective matter. What counts as novel differs from person to person, based on their prior experiences or what is sufficient to count as novel in their eyes. We discussed Challenge in the previous subsection. Regarding Spontaneity/Unpredictability, not many games (15.6%) manage to keep players on their toes throughout their playthroughs, and the ones that do tend to rely on giving completely different tasks [

63,

69] or possibly unfamiliar terms [

46,

47,

76]. Even so, this feeling is subjective for similar reasons to those for Novel Experience. We also felt that Rattlin’ Words [

75] was not as unpredictable as Acromania [

46] and Wacronyms [

76] despite the same premise of coming up with acronyms given an ordered set of letters since we felt its sets were more commonly heard. Overall, though all the games fulfilled Challenge and a lot fulfilled Novel Experience, only a few fulfilled all three aspects of Risk/Novel Problems.

Regarding the Inquiry-Based parameter, only a select few games (25%) appear to demonstrate it. The multiple solutions games [

46,

75,

76] require players to ask themselves what is the most outrageous yet coherent acronym they can form. A few other games [

51,

57,

58] allow creating flashcards where the player must decide what are the best questions and answers to put on them. Qualuff Puzzles [

74] requires the player to ask themselves what word best fits a definition and number of letters to use. Subjectivity exists, but it is kept at a minimum. Regarding Co-Construction of Meaning, all the games that involved Collaboration With Others (12.5%) [

46,

47,

75,

76] involved this characteristic, too, as the specific collaboration involves sharing ideas and thus learning from each other. No other game has demonstrated this characteristic. Overall, a rather low number of games achieve all aspects of Pragmatic/Purposeful.

4.4. Relationships Between the Characteristics of Mnemonics Serious Games on the App Stores

Here, we discuss possible explanations for the significant relationships we found between various characteristics.

Figure 2 shows the significant relationships where the first characteristic is either Age Group, Purpose, Publication Year, or Subject. Regarding Age Group, games meant for older players are more likely to use acronyms while those for younger players are more likely to use images; this is unsurprising, given that works catering to younger people often focus on images while those catering to older people usually feature more text. Games for older players have a higher chance of being puzzles while those for younger players are more likely to be generalized cognitive games, possibly out of concern that puzzles may be too confusing for them. Games for both age groups do include a decent amount of quizzes, however, as quizzes can be easily made for people of different ages. Games meant for older players are more likely to involve collaboration; perhaps working together may be seen as rather complicated for younger players. A similar case exists regarding whether games have an investigation-like nature, likely for similar reasons.

Regarding Purpose, games that are more casual and non-educational are more likely to feature Self Presence and Identity; perhaps the feeling of yourself being in another environment clashes with how traditional teaching methods or those closer to them mainly involve simply presenting screens of images and text to learners. Non-educational games are the only ones that possibly involve collaboration; perhaps educational games avoid doing so just in case players might mislead each other.

Regarding Publication Year, games in more recent years and games with an unknown initial release date are more likely to be free; the increasing abundance of and dependence on apps in general (partially due to COVID-19) may have led developers to avoid charging for their apps so potential customers would not be stolen away by competitors. Games with a known release date have all received updates while those without one apparently have not. If they actually did, then this was not stated; it is not so surprising given they did not state their release dates either. Only games in the early 2010s and early 2020s have a chance of featuring Immersion; it is unknown why those in the late 2010s and those without a known release date failed to do so. Games in more recent years are more likely to feature Learner Empowerment; perhaps more developers are recognizing the importance of letting players tailor their own experiences to maximize benefits from the game.

Regarding Subject, language games are practically guaranteed to be educational; teaching language likely requires a formal approach, after all. Games for other subjects might take a more casual approach. Language games are far more likely to feature narrative; telling a story does appear to be a good way to teach language, more so than teaching other subjects. Language games all give a novel experience; of course, learning language is easily perceived as novel. Teaching other subjects does not necessarily elicit this same perception.

Figure 3 shows the significant relationships where the first characteristic is either Game Type or Mnemonic Type. Regarding Game Type, quiz and card games are all educational, while puzzles and most cognitive games are non-educational. It is rather ironic how card games, mainly associated with fun, are educational here, while puzzle games, mainly taken seriously, are non-educational here. It turns out that the card games ACRACU [

45] and Gingko Memory & Brain Training [

53] use cards to ingrain certain mnemonics into a player’s head, similar to how traditional education often repeats concepts to ingrain them into learners’ heads. Meanwhile, the puzzle games here are more relaxed. Puzzle games are all immersive while most of the other games are not; of course puzzles are expected to require greater attention. Puzzle games are also the only ones that are possibly Multisolution-Based, though a possible explanation is that all three puzzle games that fulfill this [

46,

75,

76] are the ones where players debate on who gave the best solution. These three games and Alpha-Guess [

47], which are all puzzle games, are the only games to involve collaboration; they involve discussion with other players. Two puzzle games (Alpha-Guess [

47] and Qualuff Puzzles [

74] are the only games to have an investigation-like nature; their respective gameplay mechanics are discussed in the previous section. Puzzle games are also the most likely to feature Self-Presence/Identity, though this may be because of the Multisolution-Based games outright requiring profile creation and interaction with real people who also have profiles. Only puzzles and quizzes are possibly inquiry-based, which makes sense, given how puzzles and quizzes in general require careful thinking. Puzzles are the most likely to feature spontaneity/unpredictability, though this is likely because of the multisolution-based games again.

Regarding Mnemonic Type, only games with acronyms are possibly multisolution-based, but this is increasingly obvious because of the constantly aforementioned games that involved debating which proposed acronym is the best [

46,

75,

76]. Similar cases exist for Self-Presence/Identity and collaboration, for the same reason along with Alpha-Guess [

47] joining in. Only the three acronym debate games [

46,

75,

76] and the note organization (flashcard) games [

51,

56,

57,

58] are possibly inquiry-based, for reasons both obvious and stated before. Games with acronyms tend to be puzzles or to a lesser degree quizzes, games with images tend to be cognitive or to a lesser degree quizzes, and games with other mnemonic types tend to be quizzes. The first two quickly make a lot of sense, but what about the third? Perhaps quizzes are so versatile and varied that other mnemonic types are better with them. Also, the note organization games [

51,

56,

57,

58] use flashcards to prepare players for quizzes.

Figure 4 shows the significant relationships where the first characteristic is either Immersion, Self-Presence/Identity, Narrative, Collaboration, or Multisolution-Based. Only games with Immersion can possibly feature Self-Presence/Identity, likely because Immersion involves presence in general while Self-Presence is a stricter version (and also relies on Identity). If Immersion is unfulfilled, logically Self-Presence will be as well. Only games with Immersion can possibly involve Collaboration, though once again, the ones doing so are the acronym debate games [

46,

75,

76] and Alpha-Guess [

47]. A similar case exists for Multisolution-Based games, but without Alpha-Guess [

47]. Games without Immersion have a moderate chance of giving a Novel Experience, but games with Immersion have a higher chance of doing so; perhaps if a game is immersive, players pay more attention as opposed to dozing off and thus have a greater chance to feel like they are experiencing something new. Alternatively, a new experience itself can be immersive.

Regarding Self-Presence/Identity, only games that support this characteristic turn out to feature Collaboration. Particularly, only the acronym-based debate games [

46,

75,

76] and Alpha-Guess [

47] supported Self-Presence/Identity since, as stated numerous times before, they involved creating profiles and interacting with other players who have their own profiles. The acronym-based debate games [

46,

75,

76] also demonstrate Multisolution-Based and Inquiry-Based features, but Alpha-Guess [

47] demonstrated neither. Games with Self-Presence/Identity are also more likely to feature Spontaneity/Unpredictability, once again due to interactions with other players who might not think the same way. However, Rattlin’ Words [

75] does not since, as stated before, its letter sets seem to be more commonly heard. Also, Mnemonic Brain—Training [

63] and Mnemonics: memory development [

69] do not feature Self-Presence/Identity, but still feature Spontaneity/Unpredictability because of how there were vastly different tasks in the same game.

Regarding Narrative, games without a Narrative are almost equally likely to feature Novel Experience or not, while games with a Narrative are certain to feature Novel Experience. It certainly helps that a new story can easily be perceived as novel, though the lack of one does not make a perception impossible.

Regarding Collaboration, only those that feature it have a chance of being Multisolution-Based; by now, it is extremely clear which ones do and why [

46,

75,

76]. A similar case exists for the Inquiry-Based feature, except that the flashcard games [

51,

56,

57,

58] still manage to be Inquiry-Based without Collaboration because, as stated before, coming up with good flashcards requires asking oneself what to put on them. Another similar case exists for Spontaneity/Unpredictability, except instead of the flashcard games, the games with various different tasks [

63,

69] are the ones that feature it without Collaboration.

Regarding Multisolution-Based games, the ones that feature this (i.e., the acronym debate games [

46,

75,

76]) are guaranteed to be Inquiry-Based, too, alongside the flashcard games [

51,

56,

57,

58], which do not. As for Spontaneity/Unpredictability, Acromania [

46] and Wacronyms [

76] feature it as well, but Rattlin’ Words [

75] does not, for reasons stated before. The games with various different tasks [

63,

69] also feature it despite not being multisolution-based.