1. Introduction

Sleep represents a fundamental aspect of psychological processes. A reduction in sleep duration, even for a brief period, has been demonstrated to impair general cognitive mechanisms, including attention, concentration, decision-making, and other functions in the brain [

1]. Despite extensive research in various fields and among numerous professional groups due to its importance and necessity, the expected level of sleep awareness and quality remains below the desired standard. This emphasises the necessity of expanding the field of sleep study, including it in basic education and developing interventions on this subject [

2,

3]. In terms of gender differences, a growing body of research demonstrates that women are more likely than their male counterparts to experience sleep disturbances and report poorer sleep quality [

4,

5]. Additionally, research reports that differences exist in sleep quality, duration, latency, and architecture between men and women; for instance, women typically experience lower amounts of slow-wave sleep compared to men and show evidence of poorer sleep with ageing [

4,

6]. Moreover, sleep quality has been shown to be crucial in the workplace [

7,

8] and in decision-making [

9,

10,

11].

One area in which there is a notable deficiency in awareness and quality of sleep is sports science. Despite the awareness of the importance of sleep in sports performance among coaches, referees, athletes, and sports personnel, research has highlighted that insufficient attention has been paid to sleep by athletes and technical teams [

12,

13]. Furthermore, the lack of information on parameters that can affect sleep quality, such as sleep duration, persists [

14]. The extant literature has primarily focused on athletes, who have the most interaction in the field of sport [

15,

16]. Research in rugby reported that male athletes displayed better self-reported sleep quality and quantity than female athletes (

p ≤ 0.01;

d = 0.70;

p < 0.05;

d = 0.54) [

17]. Similar findings with poorer sleep quality in female athletes have been reported in female ultra-endurance runners [

18]. In college swimming, research reported that males exhibited poor sleep patterns during pre-competition preparation, with pronounced sleep fragmentation, while females experienced more significant sleep disturbances [

19]. In combat sports, sleep quality has been connected to better mood and performance [

20], while in judo, psychological distress was associated with poor sleep quality [

21].

Nevertheless, only a limited number of studies have examined referees’ sleep quality, despite their crucial role in sports [

22,

23,

24]. The authors of the study identified several limitations in the existing research on sleep quality in team sport referees. These included a lack of evidence on the sleep quality of referees working in individual branches and an insufficiency of the existing evidence on the sleep parameters of referees in general. They also recommended that further studies be conducted on the referee population to enhance our understanding of sleep and sleep-related variables, and to determine the current situation [

8]. Circadian rhythms are also a significant concern for sports officials, as many matches and tournaments occur in the evening or involve travel across time zones, both of which can disrupt standard sleep patterns [

25,

26].

It is not uncommon for conflicting positions to arise during a competition. Consequently, the referee officiating the judo competition must demonstrate exemplary analytical and decision-making abilities, with undivided attention to every position. It is anticipated that the referee presiding over the match will demonstrate optimal control of a range of psychological and psychomotor abilities concurrently throughout the duration of the contest. Being a judo referee is a cognitively demanding task if we take into account the fact that numerous judo techniques (68 throwing and 32 ground official IJF techniques [

27]) occur with high speed and velocity [

28] and can be followed by counter and re-counter attacks that can then continue on the ground with additional ne-waza techniques [

29]. Referees’ mistakes are subject to evaluation by video review (VR) by national and international commissions, as was implemented in judo in 2010 [

30]. The majority of questionable decisions refer to assigned scores (73.7%) and penalties (17.2%) [

31]. Moreover, the referee’s decisions in judo can be influenced by various factors, and according to the reviewed literature, no study has examined the impact of sleep factors on judo referees. Therefore, this study aims to examine the sleep quality of referees who remain active in the field of judo, with the intention of identifying any potential differences according to the following variables: age, gender, experience in the sport, level of refereeing qualification, and duration of involvement. This study represents a pioneering contribution to the existing literature regarding refereeing sleep quality, as it evaluates the sleep patterns of referees across various ranges of refereeing qualifications.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a cross-sectional design and utilised the relational screening model. A census approach was used, in which all active judo referees in Turkey were invited to participate; however, the final sample was assembled using a non-probability convenience sampling method. The study population of judo referees in Turkey consisted of 143 active referees at different refereeing qualification levels. All referees received the questionnaire and were invited to participate in the study; however, only 75 returned the questionnaires. Two participants were excluded as their questionnaires were incomplete. Final analyses were made on the data of 73 participants (42 male, 31 female). The study employed a single-blind design, where respondent identities were concealed from the researchers. A priori analysis was performed with G*Power software v.3.1.9.7 for an independent

t-test with the following characteristics tail: one (with the hypothesis that there will be a significantly higher PSQI score in female referees); effect size: 0.8; alpha error: 0.05; power: 0.95. This yielded the total sample size of 70 participants and 35 per group [

32]. However, our data with 72 participants slightly differed from the allocation ratio of 1, with 42 male and 31 female referees in each group. With a post hoc analysis, we achieved an actual study power of 0.96.

To participate in the study, individuals were required to be affiliated with the central referee board of the Turkish Judo Federation, to be actively continuing to referee, and to have been refereeing for at least one year. This means that participants had to have reached a minimum level of candidate referee. In addition, referees had to have a licence to be active referees. The seniority and qualification levels of judo referees in Turkey are as follows: 1. Candidate Referee (RS1), 2. Regional Referee (RS2), 3. National Referee (RS3), and 4. International Referee (IJF). The athletic background was reported as years of competitive judo. All questionnaires were administered in person to the referees at the development seminar, held in January 2024. The researchers were assisted by the chairman of the Central Referee Board in reaching the referees. The surveyors provided the referees participating with an explanation of the survey information. Surveyors, who were experienced in administering and collecting questionnaires, provided the referees with detailed explanations regarding the survey. All questionnaires included a statement assuring participants that no private information would be collected and that responses would remain anonymous. The average time required to complete the questionnaire was approximately three minutes. The data obtained were stored in an online repository accessible only to the researchers, with no third-party access. The research was conducted following the Helsinki Declaration, and all participants provided written consent. The study protocol was approved by the Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University Human Research in Social Sciences Local Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 2024/172).

The primary tool for data acquisition was the Turkish version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-PUKI), which has been found to be a reliable and valid instrument [

33]. The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was found to be 0.80. The 18 questions are grouped into seven component scores. Some of the components consist of answers to a single question, while others are obtained by grouping the answers to several questions. The responses to the questions pertain to sleep quality over the past month. The initial four questions are open-ended and encompass temporal evaluations of sleep. The remaining questions are designed to elicit categorical evaluations. Scores between 0 and 3 are derived from the responses to the questions, which are grouped into four categories. The scores for the components are aggregated, and the total PSQI score is calculated. The total PSQI score can range from 0 to 21. As the scores increase, sleep quality deteriorates. Individuals with a total of five points or more from seven components are considered to have poor sleep quality, while those with values below five are considered to have good sleep quality [

33]. The questionnaire measures subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value was found to be 0.863, which is an acceptable level.

The total scores were analysed using descriptive statistics, including calculating the mean and standard deviation. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test checked the data’s normality. Correlation analysis was used to check associations between selected variables. The independent

t-test was used to check the differences between genres. The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to check the differences between referee seniority/qualification levels, while one-way ANOVA was used to check differences between educational levels. To assess the combined and incremental predictive value of age, gender, and athletic background on sleep quality, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed. In addition, a mediation analysis was conducted to examine whether age mediated the relationship between referee seniority/qualification levels and PSQI scores [

34,

35]. The data were analysed using the IBM SPSS V26 programme and JAMOVI software v.2.6.19 [

36,

37,

38,

39]. The significance level of statistical findings was based on the alpha level of

p < 0.05. There was no missing data.

3. Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 present demographic and professional characteristics of the study participants. Of the 73 referees included in the final analysis, 42 (57.5%) were male and 31 (42.5%) were female. In terms of educational attainment, 15 referees (20.5%) had completed high school, 5 (6.8%) held an associate degree, 42 (57.5%) held a bachelor’s degree, and 11 (15.1%) had a postgraduate degree. Regarding referee qualification level, 31 participants (42.5%) were candidate referees, 21 (28.8%) were regional referees, 18 (24.7%) were national referees, and 3 (4.1%) held international (IJF) qualifications. The average refereeing experience was 6.6 years, with a 12.6-year athletic background.

This study analysed 73 participants (42 males, 31 females) with a mean age of 29.79 ± 11.0 years (range: 18–61). The mean refereeing experience of the participants was 6.58 ± 8.12 years, and the mean sports history was 12.60 ± 6.18 years. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was utilised to evaluate sleep quality, and the mean PSQI total score for male and female participants was 6.50 ± 3.37 and 8.16 ± 3.57, respectively. With regard to total sleep time, the mean sleep duration for males was 451 ± 89.9 min, while for females it was 479 ± 83.2 min.

Table 3 shows that an independent samples

t-test revealed a statistically significant difference in sleep quality between genders: t(71) = −2.03,

p = 0.046, d = 0.23 (small effect). Cohen’s d effect sizes were 0.43 for referees with good sleep quality (PSQI ≤ 5) and 0.31 for those with poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5), indicating moderate and small-to-moderate standardised mean differences, respectively.

Table 4 presents a Kruskal–Wallis H test to determine whether sleep quality (total PSQI score) differed by referee seniority/qualification level (1—Candidate, 2—Region, 3—National, 4—International/IJF). The test revealed no statistically significant difference in PSQI scores across the four groups of refereeing seniority: H(3, N = 73) = 5.09,

p = 0.167.

The results in

Table 5 reveal that there was no statistically significant difference in PSQI total scores among education levels, F(3, 69) = 0.503,

p = 0.682. The average score for high school graduates (N = 15) was 6.53 (SD = 3.27), the average score for associate degree graduates (N = 5) was 6.60 (SD = 2.97), the average score for undergraduate graduates (N = 42) was 7.64 (SD = 3.72), and the average score for graduate graduates (N = 11) was 6.73 (SD = 3.52). The total difference between the groups was 19.16, and the mean square was 6.39. The total variance within groups (within groups) was 876.76, and the mean square was 12.71.

According to the correlation analysis presented in

Table 6, significant negative correlations were found between the PSQI total score and age (r = −0.322,

p < 0.05) as well as refereeing experience (r = −0.277,

p < 0.05). In contrast, significant positive correlations were observed between age and refereeing experience (r = 0.870,

p < 0.001) and between age and sports background (r = 0.236,

p < 0.05).

In

Table 7, three models were used to analyse the effects of the independent variables on the target variable. In the first model, gender had a significant effect (b = 1.66, SE = 0.818, t = 2.03,

p = 0.046), and the R

2 value of the model was 0.0549. The second model additionally included age as a predictor. The overall model was improved, explaining 13.8% of the variance, R

2 = 0.138, R = 0.371. However, gender was no longer a significant predictor, b = 1.322, t = 1.66,

p = 0.102. In contrast, age had a significant negative effect on the outcome, b = −0.094, SE = 0.036, t = −2.59,

p = 0.012, indicating that as age increased, the outcome score decreased. The third and final model included athletic background. This model accounted for 19.4% of the variance in the outcome, R

2 = 0.194, R = 0.441. All predictors were statistically significant: (1) gender: b = 1.711, SE = 0.796, t = 2.15,

p = 0.035; (2) athletic background: b = 0.143, SE = 0.065, t = 2.20,

p = 0.031; (3) Age: b = −0.110, SE = 0.036, t = −3.06,

p = 0.003. Results indicate that being male, having a longer athletic background, and being younger are associated with higher (worse) PSQI score values (i.e., poorer sleep quality) in the outcome variable.

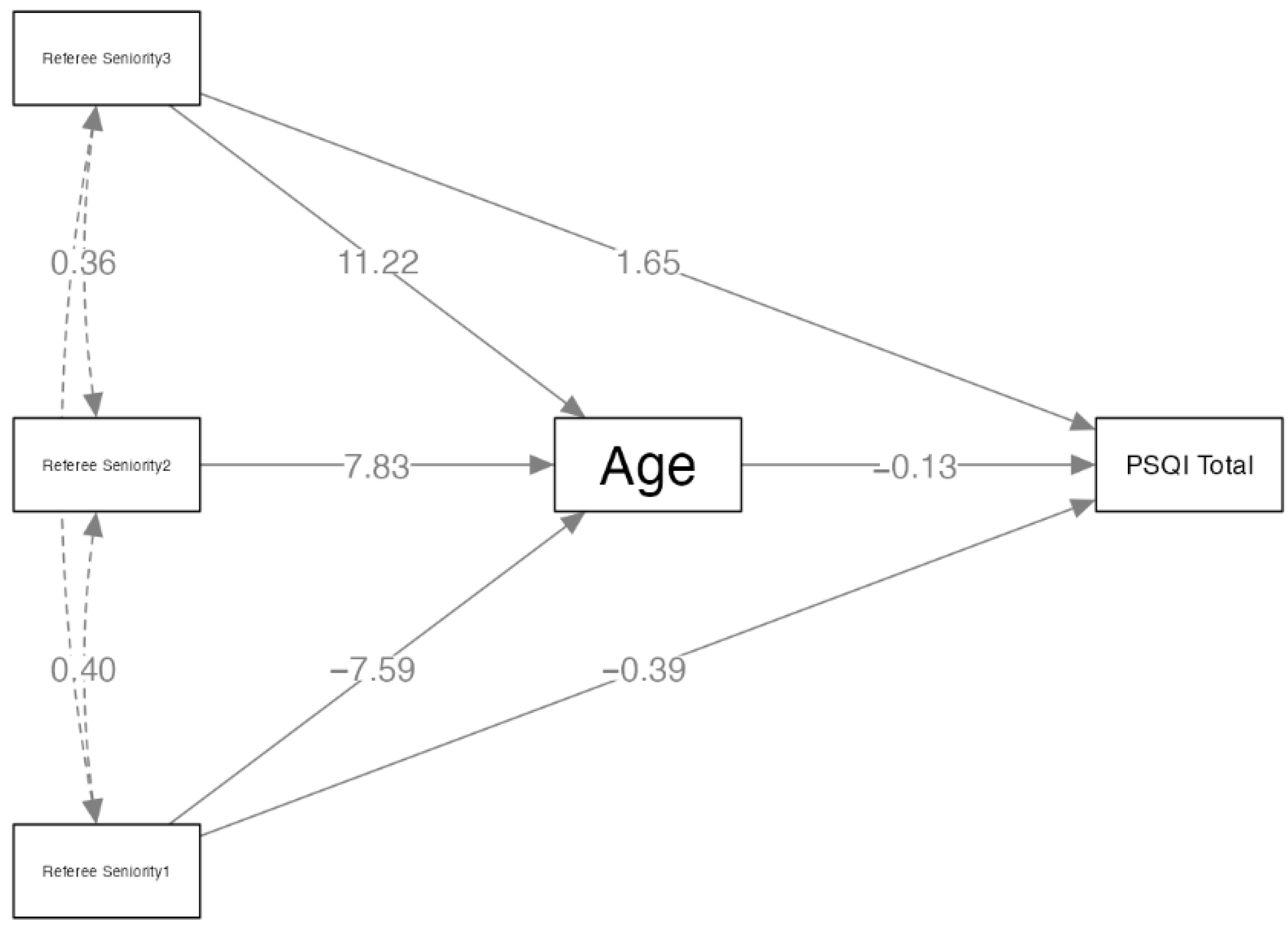

The results in

Table 8 and

Figure 1 present the mediation analysis, which assessed indirect, direct, and total effects for each predictor pathway. Significant indirect effects were found for all three referee seniority/qualification level (RS) variables through age. Specifically, (1) RS 1 had a significant indirect effect on PSQI total via age, b = 0.976, SE = 0.4673, 95% CI [0.0603, 1.8919], β = 0.2320, z = 2.089,

p = 0.037; (2) RS2 showed a significant negative indirect effect, b = −1.006, SE = 0.4822, 95% CI [−1.9513, −0.0611], β = −0.2297, z = −2.087,

p = 0.037; and (3) RS3 also demonstrated a marginally significant indirect effect, b = −1.442, SE = 0.7353, 95% CI [−2.8829, −0.0007], β = −0.2323, z = −1.961,

p = 0.050. The individual path from RS1 to age was significantly negative, b = −7.593, SE = 1.6054, 95% CI [−10.7398, −4.4467], β = −0.5787, z = −4.730,

p < 0.001. This suggests that higher RS1 scores were associated with younger age. Conversely, both RS2 (b = 7.827, β = 0.5729,

p < 0.001) and RS3 (b = 11.216, β = 0.5794,

p < 0.001) were positively associated with age. The path from age to PSQI total was also significant, b = −0.129, SE = 0.0552, 95% CI [−0.2368, −0.0203], β = −0.4009, z = −2.328,

p = 0.020, indicating that older age predicted better sleep quality (i.e., lower PSQI scores).

None of the direct paths from RS variables to PSQI total reached statistical significance: (1) RS1 → PSQI Total: b = −0.387, p = 0.654; (2) RS2 → PSQI Total: b = −0.342, p = 0.703; and (3) RS3 → PSQI Total: b = 1.649, p = 0.297. The total effects of RS2 on PSQI total were also not significant (b = −1.348, p = 0.100), effects of RS1 (b = 0.589, p = 0.456) and RS3 (b = 0.208, p = 0.891).

4. Discussion

The present study explored how various factors—such as gender, age, education, referee seniority, and athletic background—relate to sleep quality among referees as measured by the PSQI tool. According to gender, female referees reported significantly poorer sleep than males. While the effect size was relatively small, it still points to a gender-based disparity that may warrant further exploration, particularly in relation to lifestyle or stress-related differences within officiating roles. The study’s data also indicated suboptimum referee sleep quality, regardless of gender, years of experience, or seniority/qualification level. Educational levels and referee seniority did not appear to play a major role. However, age emerged as a meaningful factor in multiple analyses. Mediation analysis results highlighted that age partially explained the relationship between referee seniority/qualification level and sleep quality, showing that older referees generally reported better sleep. This pattern held even when other variables were taken into account. The observed improvement in sleep quality with advancing age may be attributed to the accumulated professional expertise and enhanced stress management competencies characteristic of senior referees. Additionally, the regression analysis, when the athletic background was included alongside gender and age, showed that the model’s ability to predict sleep quality improved.

Multivariate regression analyses revealed a statistically significant positive association between refereeing tenure and sleep quality (β = −0.082,

p = 0.049), while demonstrating an inverse relationship with the athlete-to-referee career duration ratio (β = −0.205,

p = 0.023). These empirical findings suggest that, notwithstanding the beneficial transfer of structured behavioural patterns acquired through prolonged athletic careers, the cumulative physiological stress from intensive training regimens and transitional adaptation challenges in professional role conversion may exert deleterious effects on sleep parameters. The results underscore the moderating influence of training intensity and transition duration in the complex interplay between athletic background and sleep quality. Consequently, the implementation of tailored intervention protocols specifically designed for officials with predominantly athletic career trajectories is strongly recommended. Given that all of the referees had a history of sportsmanship, it is presumed that they did not receive any training in sleep awareness and consciousness, either during their sportsmanship careers or in their professional refereeing careers. The fast-paced nature of judo matches, and the importance of decision-making skills, mean that a lack of sleep is likely to affect the analytical abilities of referees [

40], as well as their mood [

41] and ability to sustain attention [

42]. Furthermore, it has been linked to stress management [

43], mental health [

44,

45], fatigue, anger and unhappiness [

46], and depression and anxiety [

30]. It is well documented that referees, like athletes participating in international competitions, experience suboptimal sleep quality due to factors such as inadequate sleep duration, extended travel, and jet lag [

22]. This might explain why the results obtained from the regression analysis, which took into account athletic background alongside gender and age, were poorer, as the participants might have carried this negative experience into their second career as referees.

The mediation results showed that older referees generally reported better sleep. Elite referees undergo a long educational process with many practical seminars for which they need to be in solid physical condition [

47]. Therefore, an active role as a judo referee means a long-term engagement in physical activity, and this has been shown to be strongly associated with enhanced cardiovascular function, metabolic health, and reduced risk of chronic diseases [

48]. Moreover, a longer athletic background could also explain the mediation analysis’s results, where higher age was associated with lower PSQI scores, meaning that older referees tended to report better sleep. Therefore, judokas with more athletic experience began their officiating and refereeing roles later in life and tended to sleep better, potentially due to long-term physical conditioning and structured routines.

Referees may experience elevated stress levels when travelling long distances before a competition, adjusting to new sleep environments, contemplating the significance of the event, and grappling with the inherent challenges of their chosen sport [

47,

49]. It is well-documented that both acute and chronic stress can disrupt sleep patterns and the circadian rhythm [

50]. Consequently, it can be hypothesised that poor sleep conditions may also have an adverse effect on the physical health of referees. Referees face multiple simultaneous demands in a competition, as well as decision-making pressure and role-related stress, all of which can hinder their accuracy—especially with the added pressure from introducing the IJF referee world ranking system [

27]. Additionally, the results showed that female referees reported significantly poorer sleep quality than males, which aligns with previous studies linking females to poorer sleep and less sleep than men of similar ages [

51]; however, the effect size found in our study for this difference was small (d = 0.23). This suggests that, although gender may contribute to sleep quality, it is likely not the primary factor affecting sleep quality among referees, and future research should continue to explore other individual and contextual variables. This difference has been reported to be even more substantial after the age of 30 [

52]. The aforementioned IJF world ranking list for referees may add additional pressure, as females are underrepresented, with only 16 out of 42 top referees being female, and there are only 4 female referees in the current top 10 referees list [

27].

Reference [

53] posits that this can impede fair play in any sport where there is a fight, influence the athlete’s psychology if they make erroneous decisions, and impair the referee’s professional identity. Sleep significantly impacts referees in numerous ways, largely due to its effects on the external environment and the human body. This illustrates the crucial importance of referees being aware of the significance of sleep.

Especially in judo competitions, the most decisive matches often occur late in the day, in the final block. This is when fatigue, performance pressure, and emotional tension are at their peak for all involved—athletes, coaches, and referees. Referees, likewise exposed to the cumulative effects of physical and cognitive fatigue, are tasked with officiating these high-stakes bouts. As such, the timing and demands of the final competition phase represent a critical factor warranting consideration in evaluations of refereeing performance and decision-making under pressure. Future studies should be of an experimental design and provide sleep hygiene training for referees and further examine this phase of the competition. Reference [

48] emphasised that referees can become more effective through continuous training. Additionally, the study reveals several variables associated with the decision-making processes of referees. Additionally, research has shown that sleep quality may impact the cognitive and decision-making abilities of sports referees, and that gender may also influence this relationship [

19,

54]. Therefore, it is recommended that strategies for enhancing the sleep quality of the referee group be investigated, with particular attention to training and awareness-raising initiatives on sleep hygiene [

23]. A literature review reveals a paucity of research on this topic, with referees representing a relatively small community and few studies examining sleep parameters [

23]. Consequently, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding sleep patterns in referees engaged in comparable combat sports or individual disciplines, as few studies have investigated sleep patterns in referees across disciplines and at different levels [

24]. In practical terms, recognising that younger and female referees are particularly at risk for poorer sleep, it is important to offer support in the form of practical sleep education, delivered through interactive workshops [

55]. Young referees who are still adjusting to the demands of the role may especially benefit from peer mentoring, where experienced officials share their routines and tips—a practice shown to support professional development, confidence, and retention among sports officials [

56,

57]. Tailored sleep hygiene protocols for sports officials, along with simple checklists or reminders to reinforce good habits, should be developed and integrated by sports associations and IJF referee education into ongoing referee training to help officials stay healthy, alert, and ready to make important decisions on the field.

It has been suggested that if referees, who, like athletes, are affected by many intrinsic and extrinsic factors, receive training in sleep and sleep hygiene, they can prevent these factors from worsening sleep quality and thus improve many psychological parameters, especially decision-making skills [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

58,

59,

60]. This is important because sleep quality affects decision-making and neural responses, especially in risky decision-making [

61]. Further research is therefore needed. It is essential that future studies focus on other sports professionals, as sleep is a crucial issue that all sports professionals should be aware of.

The present study provides valuable insights into the sleep quality of judo referees. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. This study is limited to only 2024 active referees in Türkiye and does not comprise an international sample of referees. Future studies should encompass a broader range of nationalities. The cross-sectional design prevents causal interpretations of the observed relationships. Therefore, longitudinal studies should be conducted to follow the development of referees’ careers. Additionally, small subgroup sizes of international referees might hinder the applicability of the data to elite-level referees. However, this is a standard refereeing structure for every IJF country member, where the elite group of referees is very small. The study also did not account for variables such as stress levels, work schedules, competition stress, travel requirements, jet lag, lifestyle habits, physical fitness, etc., which might impact the results. Therefore, further studies should address these limitations to gain insight into the sleeping patterns of judo referees that may impact their decision-making.

5. Conclusions

This study sheds light on the sleep habits of judo referees and how various factors may shape their sleep duration and quality. This is the first study to date on sleep quality among judo referees. Overall, the data indicate suboptimal sleep quality among referees, regardless of gender, years of experience, or seniority/qualification level. Additionally, female referees reported poorer sleep than their male counterparts, which confirms previous findings on gender and sleep disturbances. Moreover, age and athletic background were more reliable indicators of sleep quality. Older referees generally slept better. Particular research is important as referees, like athletes, are pressured to perform consistently and make clear-headed decisions, often in high-pressure situations. Insufficient and low-quality sleep can impact their health, focus, and decision-making during competitions. Given how crucial sleep is to cognitive and physical performance, it would be recommendable to support referees via sleep education or wellness training as part of their ongoing referee development and education for progression to higher qualifications. Future studies should build on this by following referees over time, delving deeper into physical fitness levels, stress, travel, and workload to gain a clearer picture of how well they are actually sleeping and how this affects their performance. These findings might be of use for referees in other sports with a similar competition format as that used in judo. Although these findings provide valuable insights, their generalizability is constrained by several factors, including the cross-sectional nature of the study, the use of self-reported data, and the focus on referees from a single country. Consequently, these results should be interpreted with caution when considering referees from other sports or countries, as differences in culture, organisational structure, or sport-specific demands may also impact sleep patterns. However, these factors are all to be investigated in the future.