Abstract

Disruptions in a single supplier’s operations can trigger cascading effects across the entire supply chain, highlighting the critical importance of effective supplier-focused risk management. While supply chain risk management (SCRM) frameworks encompass diverse dimensions—such as supply, products, demand, and information—risks specifically related to suppliers demand tailored strategies and analytical focus. Despite the growing volume of publications on this topic, the literature still lacks updated conceptual guidance on how to manage these risks, particularly in light of emerging challenges and practices. This study addresses this gap, with the primary objective of developing a contemporary conceptual framework for supplier risk management, reflecting recent academic and practical advances. The research methodology combines bibliometric analysis, the PRISMA systematic review protocol, and visualization tools including CiteSpace and CitNet Explorer. Key findings include the evolution of thematic clusters over time, with “supplier selection” identified as the most dominant theme, and simulation as the prevailing research method. The automotive industry emerges as the most frequently studied empirical context. Moreover, the study expands existing frameworks by introducing two emerging dimensions—environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and information technology (IT)—as key factors in supplier risk management. This framework contributes to theory and practice by offering an updated lens for understanding supplier-related risks and providing decision-makers with structured insights to enhance resilience in complex supply networks.

1. Introduction

Supply chain risk management (SCRM) in a firm may be applied through four basic approaches: supply management, product management, demand management, and information management [1]. We now further investigate the supply management approach (or perspective), which is the one focused on the firm’s suppliers, as it is necessary to develop integrated knowledge about the multiple levels of the chain in order to ensure profitability and business continuity [2,3,4,5], considering that direct and indirect suppliers are critical sources of risks [6,7,8].

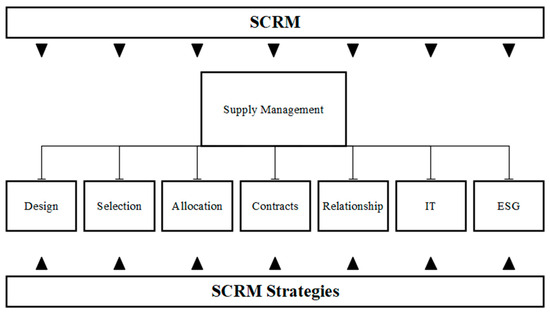

Regarding this perspective, companies’ supply/supplier management departments must deal with five interrelated issues (dimensions): network design, supplier selection, order allocation, contract management, and supplier relationships, as analyzed by Tang [1]. Since then, extensive research developments to each of these dimensions have been made by different authors separately, but no review or research profile has been found on the subject. Furthermore, nearly two decades later, there is still a lack of studies seeking to update that foundational work by identifying new key dimensions that ought to be considered within the scope of supplier management. Therefore, in order to address this gap, the following two research questions have been formulated:

- RQ1: Regarding SCRM from the supplier management perspective, which are the main authors, research centers, issues developed over time, and emerging topics?

- RQ2: Based on research trends and future directions, are there any new major issues that companies must address when they deal with supplier management?

RQ1 and RQ2 are interrelated since both are derived from the same analysis of research developments in supply/supplier management risks. First, we answer RQ1 through a systematic literature review and research profiling on the field of SCRM from the supplier management perspective, which is the first specific objective of this research. Then we answer RQ2 by evaluating and compiling research trends and future directions and then organizing these findings in a unified supplier management framework that aims to update the work by Tang [1] on the significant issues (dimensions) of supply/supplier management, which is the second specific objective of this research.

From a concept standpoint, we use the seminal work of Tang [1] as the root study, from which we select a snippet (the supply/supplier management approach) and expand it to investigate the subject further. From a theoretical standpoint, we present clues for current research and a novel guide for future research in SCRM from the supplier management perspective. Then again, managers can also benefit from this paper because our framework objectively marks the main issues that they should observe when dealing with supply/supplier management risks in their companies.

The relevance of this research unfolds in two aspects. First, the topic of SCRM has emerged with rapid prominence in recent years and is considered to be of great interest, both academic and practical [9,10,11,12,13,14], especially after the global challenges raised by the COVID-19 pandemic [15,16,17,18]. The justification lies in the consensus that SCRM is an essential resource for competitive capacity, as organizations can suffer losses of high economic value due to disruptions in the supply chain, according to several examples found in the literature [19].

Second, supplier management is fundamental in the supply chain area due to attributes such as material acquisition cost, quality, delivery, and sustainability, which give suppliers a critical role in the chain as risk generators [20,21,22,23]. Therefore, the SCRM approach with a specific focus on suppliers fills a research gap on a relevant topic, serving as a complement to the comprehensive SCRM review by Wicaksana et al. [18] and previous reviews about risk typology [12], quantitative models [17], and AI [16], since none of these reviews deal with the supply/supplier perspective.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 details the materials and methods used for data collection and processing. Section 3 explains the study’s theoretical background, divided into multi-level suppliers and supplier management dimensions. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, including the bibliometric analysis and research profile. Finally, Section 5 deals with final considerations, such as the impact and limitations of this research.

2. Materials and Methods

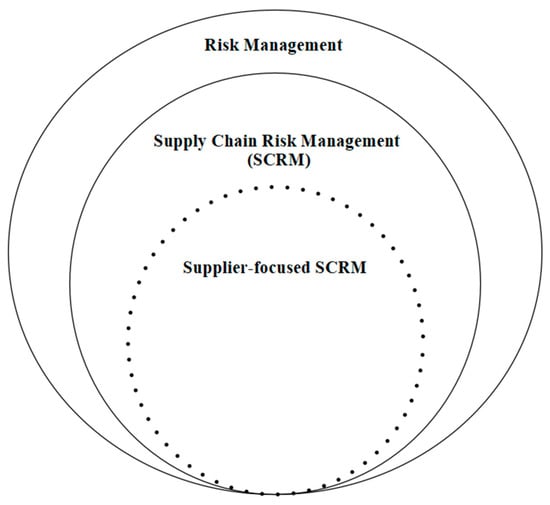

This research aims to address supplier management risks, which means that we investigate SCRM from the supply/supplier management perspective, according to the four SCRM perspectives outlined by Tang [1] (supply, product, demand, information). This perspective is part of the general area of SCRM, which, in turn, is part of the larger area of risk management. Figure 1 illustrates this concept, where the dotted circle represents the approach of this research.

Figure 1.

Research concept.

This research was divided into two phases: data collection and data analysis. For the first phase, we defined search criteria and selected the Web of Science (WoS) database, belonging to Clarivate Analytics, due to its broad multidisciplinary coverage, relevance, and quality [24,25]. Also, the data provided is supported by several bibliometric tools, including CitNet Explorer v.1.0.0 and CiteSpace v.1.0.1, which we used for carrying out the second phase. In turn, these tools are designed to support the analytical process, aid understanding, and answer various questions about a given field of scientific research [25,26,27].

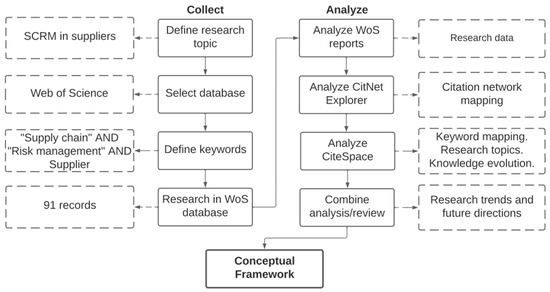

Then, these analyses were combined with the literature review to identify research trends, leading to an updated conceptual framework that can guide current and future research, as it identifies the significant dimensions of supplier management risks. Figure 2 demonstrates the research planning flowchart, where dashed lines represent the products of each stage, as detailed throughout this section.

Figure 2.

Research flowchart.

The search on WoS was carried out on 7 January 2023 using the following criteria: “Supply chain” (Topic) AND “Risk management” (Topic) AND Supplier (Title), and applying the filter Document types: article or review article. The “Topic” field uses the title, abstract, and keywords to determine the search. It was chosen not to establish a time limit, so WoS ran the search from 1945 to 2023. The search term “Supplier” was considered in the title to prioritize articles that, in fact, treat suppliers as the main subject, amidst the extensive literature about SCRM. A total of 91 studies were found.

Results were manually screened for duplicates, but none were found. Therefore, all 91 articles were separated for subsequent detailed reading. This final sample size of 91 articles is considered enough for a robust bibliometric analysis, as we have identified similar sample sizes in several relevant SCRM reviews found in WoS, such as those of Rinaldi et al. (99 articles) [12] and Deiva Ganesh and Kalpana (85 articles) [16].

Then, the bibliometric reports offered by WoS were analyzed to provide an overview of the global interest in this theme, which was the first step of the research profile. The next step involved mapping the reference network with CitNet Explorer, which focuses on citation impact indicators, normalized by the research field. Most frequently cited publications are organized into clusters based on their citation relationships. Therefore, publications from the same cluster tend to be strongly associated [27].

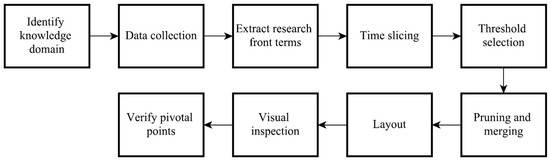

Then we developed new bibliometric analyses using CiteSpace, one of the most applied tools for knowledge mapping, which produces networks that reveal the structure of a given research field [25,26], aiming to identify the main clusters of research areas and how the authors are positioned in these clusters [27]. This tool is based on text mining, which allows the analysis of different bibliometric entities, such as references and keywords. Visualizations generated by CiteSpace correspond to the fusion of several networks extracted each year and grouped into clusters. In this way, we sought to characterize the development of the topic over time and provide a complementary view to that obtained with CitNet Explorer, as presented in Section 4 (Results and Discussion). Figure 3, drawn up based on Chen [26], describes the procedure for using CiteSpace.

Figure 3.

Procedure for using CiteSpace.

As noted, the 91 articles were used in all bibliometric analyses, constituting the research profile. This is the main research of this work. However, we also conducted a complementary search in the conventional SCRM literature. This complementary search was performed manually and is not part of the bibliometric analysis, as its objective is only to serve as a supplement to give even more robustness to this work by covering seminal developments, as well as possible future research directions, which may be of interest to this work but were not identified within the search criteria of the main research. After all, supplier risks are part of the general area of SCRM, as outlined previously in Figure 1.

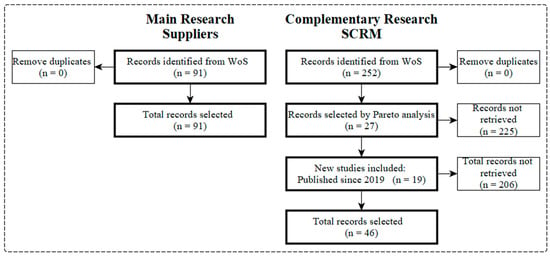

To this end, the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol was applied. Initially published in 2009 and improved in the current version, the protocol was designed to help researchers transparently report the reasons for the literature review, the steps taken to identify and select articles, and the findings about studies already published. Its recommendations were widely adopted, with citations in over 60 thousand articles and endorsement by around 200 journals and institutions [28].

Thus, the complementary research on WoS was carried out on the same day, using “Supply chain” (Title) AND “Risk management” (Title), besides the filter document types: article or review article. Based on PRISMA 2020, Pareto analysis was applied to select, amongst 252 articles identified, those responsible for 80% of the citations. This means that, following a Pareto-based selection criterion, the articles were ranked in descending order according to their citation count, as the WoS citation report provided. Then, articles were sequentially retrieved from the list until the cumulative citation count reached approximately 80% of the total citations in the sample, ensuring that the most influential articles were included.

This process resulted in 27 articles that are considered seminal in the field of SCRM. We then added articles published since 2019 (19 articles) because, despite having yet to have a significant number of citations, they are up-to-date, innovative, and prone to reveal highlights for future research. There were no duplicates. Therefore, the complementary research was concluded with 46 articles. Figure 4 shows PRISMA 2020 applied for the complementary research as just described, as well as the 91 articles previously selected in the main study.

Figure 4.

Article selection with PRISMA 2020.

To ensure methodological rigor, we thoroughly reviewed the selected articles (main and complementary) and systematically cross-validated the extracted information. This approach integrates traditional literature review techniques with research profiling tools, aiming to generate robust insights from both the quantitative outputs and the qualitative interpretations. Wicaksana et al. [18] emphasize that such interpretations rely heavily on the researchers’ cognitive ability to synthesize complex information critically.

3. Theoretical Background

As discussed in Section 2 (Materials and Methods), a systematic literature review is a research method that seeks to synthesize and analyze existing studies on a given subject or research question to provide a comprehensive theoretical background and impartial view of the current knowledge in a specific area. The review disclosed in this section introduces the theoretical background of this study, where all references were obtained from articles selected in our research. The selection process is also detailed in Section 2.

Following PRISMA 2020 recommendations, we highlight the relevance of this review regarding our research goals: both Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 contribute as a subsidy to answering RQ1 and RQ2, alongside the findings shown in Section 4 (Results and Discussion). Section 3.1 addresses supply chain risks of direct and indirect suppliers and contributes to answering RQ1. Section 3.2 addresses SCRM from the supplier management perspective, using Tang [1] as the root study, and contributes to answering RQ1 and RQ2.

3.1. Supply Chain Risks of Direct and Indirect Suppliers

A business network is made up of several layers or tiers of suppliers. Primary suppliers (tier 1) deliver directly to the focal company while having their own suppliers, which are indirectly linked to the focal company. The relationship scale varies, being stronger for primary suppliers, but all chain elements carry part of the risks relative to the others [8]. The level-1 supplier is perceived as holding the highest risk in the chain, as it deals directly with the focal company and, simultaneously, depends on level-2 suppliers. If it is not able to meet the focal company’s demand, even due to disruptions at level 2, the primary supplier absorbs the risk of losing the customer [4].

Thus, corporations entrust responsibilities and assignments to their primary suppliers to maximize benefits and minimize transactions that do not add value. As a result, they increasingly depend on the ability of these suppliers to meet requirements [29] and demonstrate resilience in the face of disruptions coming from previous levels in the chain [30], mainly because disruptions can occur interdependently when suppliers are related, for example, by geographic area where a catastrophe occurs, or simply because they share the same level-2 supplier [13]. Despite this, the organization usually selects a supplier without considering that it will absorb its sub-chain and, therefore, add risks to the entire ecosystem [7].

Different approaches are found in the literature, which consider multi-level suppliers when dealing with aspects related to risks in the supply chain. Kull and Closs [31] analyze the relationship between risks and inventory. When considering the effects that the risks of disruption at a tier-2 supplier cause on the focal company’s inventory sizing, they conclude that increasing the inventory is not always the best strategy that an organization can adopt to stabilize the system as such a decision is likely to generate greater exposure to other risks. They also suggest that allocating smaller and more frequent orders is an option for mitigating risks, even when disruptions are expected at the tier-2 supplier.

Durach et al. [30] investigate the resilience of tier-1 suppliers in the face of disruption from a common tier-2 supplier, considering “resilience” as a firm’s capability to respond to disruptions and restore normal operations. From a more detailed perspective, Rajesh and Ravi [20] define a resilient supplier as “suppliers that are capable of providing good quality products at reasonable prices, and flexible enough to accommodate fluctuations in demand with reduced lead times and risks, without compromising security and environmental practices environment”. The authors also state that developing an SCRM culture is essential to achieving this objective. It is also observed that the reaction to disruptions is strongly related to the type and intensity of the event causing the disruption [13], and therefore subject to different types of risks, such as natural disasters, financial crises, and strikes [32]; geographic location, crime, supply limitations, and political and economic stability [33]; competitor actions, information management, technological changes, and consumer profile changes [20]; operational failures, sales effort, and resource dependence [34].

Thus, the aforementioned study by Durach et al. [30] points to a path to help build primary suppliers’ resilience to level-2 (or earlier) disruptions: cooperative competition. The authors highlight a case in which one of Toyota’s first-tier suppliers, faced with a fire in their plant, was able to avert disruption due to the joint effort of other Toyota suppliers. However, they emphasize that this strategy does not help to mitigate financial risks for the client company when it is not part of a strong integration scenario with such primary suppliers. Therefore, they suggest network mapping, the monitoring of critical suppliers, and information exchange as mitigation actions, which corroborates the former suggestion by Sinha et al. [35] that an integration initiative could help to overcome uncertainties and conflicting objectives in a network in order to mitigate the risk that partners will lose their traditional competitive advantages over time.

Torabi et al. [13] also analyze the client company’s perspective and state that it is essential to protect it from shortages and other disruptions in the supply flow. The authors suggest proactive strategies to boost supply chain resilience, such as (i) the maintenance, by the client company, of substitute suppliers for emergency situations; (ii) structural and operational strengthening by suppliers; (iii) the development of a business continuity plan (BCP) by suppliers, which includes the development of strategic procedures that allow the organization to fulfill its critical deliveries in the event of incidents.

Therefore, the studies discussed in this subsection highlight the importance of organizations devoting greater efforts to identifying and managing risks across the various supply chain tiers rather than focusing solely on direct suppliers. This is one of the main issues that has been consistently raised in this field of research over time, contributing to the answer to RQ1.

3.2. SCRM from the Supplier Management Approach

Supplier-related risks constitute one of the most significant sources of risk in a supply chain and must be taken into account when formulating SCRM strategies [36], although it is more appropriate to consider them as “risk types” rather than “risk factors” [12]. Thus, aiming to deal with this type of risk effectively, Tang [1] shows five main and interrelated issues (or dimensions) that comprise supplier management: network design, supplier selection, order allocation, contract management, and supplier relationships. These five dimensions will be detailed below, in light of the literature on SCRM.

Design: This comprises the analysis of different configurations of facilities and resources that can be explored in an integrated manner in the supply chain, such as suppliers, warehouses, production, and transportation planning, among others [1]. For many authors, this is the first step towards efficient disruption management [19,37] as the supply chain’s design must be considered to encompass risks due to supplier complexity and supplier dependence [38]. Due to the density of contemporary chains, one can point out in the literature growing efforts—albeit from beginners and subject to further exploration—to apply programming systems based on artificial intelligence (AI) to supply chain design in order to automate the decision-making process in uncertain environments, such as stochastic programming, robust optimization, fuzzy programming, machine learning, rationalization, data mining, agent-based modeling, and network-based approaches, such as Petri nets, Bayesian networks, Markov networks, and Monte Carlo simulation [14,16].

Selection: This aims to identify suppliers that best fit the risk criteria determined by the customer, such as risks of stockouts, delivery delays, or low-quality products, generally involving the application of mathematical methods and models [1]. In this case, the model’s typical answer is a performance ranking to classify these suppliers, whether based on risk profile, resilience profile, or issues related to sustainability and the environment [17]. Supplier selection is the most crucial decision variable for the success of a supply chain [6], thus representing the majority of articles on SCRM [12]. In this sense, Rinaldi et al. [17] researched articles that present quantitative models in SCRM, where they found that 25% of the works deal with the problem of supplier selection in an uncertain environment.

In parallel, in the literature surveyed by this research, applications of several multi-criteria decision aid methods (MCDMs) to the supplier selection problem were identified in the last ten years: AHP [15,32,39,40], ANP [20], GRA [21,23], TOPSIS [6,40], DEA [41,42], MULTIMOORA [43], BWM [44], and VIKOR [8], in addition to simulation models based on fuzzy logic, Bayesian networks, and other programming techniques [13,45,46,47,48,49].

Allocation: This concerns understanding the risks related to purchase orders and inventory management caused by uncertainties in demand, inventory, lead time, capacity, and costs [1]. The growing trend of applying lean methodologies, such as the just-in-time concept, causes organizations to practice low inventory levels and reduce safety stocks, which makes them more vulnerable to market fluctuations, which are not unusual incidents [37]. Several authors propose mathematical models to optimize order allocation in this context, thus reducing risks [36,44,50]. Ur Rehman et al. [51] consider production planning and control (PPC) as a catalytic area for SCRM, which, in turn, is a performance catalytic process. Therefore, they suggest the implementation of improvements related to PPC, such as a focus on the process, reduction in batch size, application of kanban, and use of product tracking systems, via RFID or barcode, to cover the risks arising from suppliers and other external agents of the supply chain.

Contracts: This refers to implementing coordinated actions to improve operational efficiency in the face of demand and price uncertainties [1]. Partnerships with suppliers are crucial for cost performance and innovation [52] and for financial performance and the development of SCRM strategies aimed at network robustness [53,54], since the result of one company can represent a risk event for another company in the chain, especially in the case of small suppliers far from the main manufacturer [55]. In this case, Dias et al. [55] suggest two joint practices in SCRM: (i) sharing risk information, such as predicting disruptions, allowing for the identification of vulnerabilities and rapid response by organizations; and (ii) the creation of a formal risk sharing mechanism to align between partners—via contract or agreement—each other’s incentives and obligations, for example, wholesale price, pre-defined order quantity, access to the company’s inventory client, and collaborative planning, among others.

Relationship: This dimension makes it possible to evaluate the level of strategic importance of the company from a partner company’s perspective [1]. Dias et al. [55] also identify three characteristics of the supplier–client relationship that can influence the effectiveness of the two aforementioned practices: the duration of the relationship, level of trust in the partner, and shared management of knowledge about SCRM. In the same sense, Blackhurst et al. [56] present a methodology for monitoring risks that, according to the authors, can be fed by the supplier itself, depending on its relationship with the customer. Integration is key to achieving collaborative status in the supply chain [29,57,58]. Fan and Stevenson [5] add that, despite the relevance commonly associated with contractual issues, relational issues need more attention from SCRM research, expanding efforts to clarify the dynamics between contractual and relational mechanisms.

Finally, an SCRM strategy must be chosen according to the type of risk [59], and its implementation involves investments and potential benefits [5]. Regarding risks in supplier management, one of the ways to mitigate this type of risk is to expand and globally diversify the supplier portfolio so that disruptive events, such as financial crises or natural catastrophes, do not affect everyone with the same intensity [3]. This is the hedging strategy [60].

This approach follows the concept of multi-sourcing, according to which an organization provides robustness to the chain by maintaining multiple suppliers in its portfolio, to ensure supply backups in cases where there is a significant risk of disruptions, quality deviations, or even insolvency of the main supplier [11,37]. This strategic concept of redundancy is the most common way to reduce risks in the supply chain as it can provide resilience and efficiency to the chain [1]. Although it has already been studied extensively, it is in a new moment of expansion with regard to research interest due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the emerging need for the rapid adaptation of the supply chain to cover multiple disruptions [18].

On the other hand, this strategy presents high complexity and cost, especially when many companies seek to eliminate waste by reducing the number of suppliers, based on a lean philosophy [10]. Thus, Wieland and Wallenburg [11] demonstrate that, in certain cases, the agility in identifying a new supplier can replace the robustness of maintaining alternative suppliers. In addition, Ahmed and Huma [61] provide empirical evidence that it is possible to generate resilience and robustness in the supply chain through a hybrid SCRM strategy, which combines lean (focus on cost) and agile (focus on response) approaches: concerning the internal environment, quality management is used to boost the lean approach through continuous improvement, the elimination of waste, and excellence in processes, including in the selection of suppliers. Regarding the external environment, market orientation drives the agile approach through understanding and adapting to opportunities and threats, such as competitors’ movements and customer needs. Cultural differences [62] and supplier development [63,64] must also be considered when determining SCRM strategies.

Therefore, this subsection presents the main issues that have been developed over time within each dimension of supplier management, contributing to the answer to RQ1. It also serves as the backbone for the development of this study, leading to the construction of the conceptual framework that answers RQ2.

4. Results and Discussion

This section is structured as follows: Section 4.1 details the research profiling, with the main authors, research centers, research clusters, and emerging topics, among other relevant issues on the theme of SCRM from the supply/supplier management approach. We also identify the most impactful works and the main route of knowledge, outlining how these works are interconnected. Thus, we answer RQ1 regarding SCRM from the supplier management perspective: What are the main authors, research centers, issues developed over time, and emerging topics?

In sequence, Section 4.2 further approaches research trends and future directions. Finally, we compile all results found and present an updated conceptual framework that identifies new major dimensions that companies must address when they deal with supplier management. Therefore, we answer RQ2: Based on research trends and future directions, are there any new major issues that companies must address when they deal with supplier management?

4.1. Research Profiling

All 91 articles obtained from WoS are from 2004 to 2023, representing a recent growth of this topic. It trends towards an increase in annual production, with the highest concentration of publications occurring from 2018 to 2021 and the peak of 12 publications (13% of the total) in 2021. We can conclude that the topic is contemporary and of growing interest in the scientific community. A total of 50 journals were identified in the sample, most in the field of operations management. However, 14 knowledge areas were identified: considering that an article might be associated with more than one area, the most representative are Engineering, with 43 records (47% of the sample), Economics and Business, with 34 records (37%), and Operational Research and Management Science, with 30 records (33%). It is also noted that there are research areas as diverse as Computer Science, Environmental Sciences, and Automation Control. These findings are relevant. Thus, they lead to the inference that the theme SCRM in suppliers is applicable in different contexts and allows for varied approaches, application possibilities, and study contexts.

The theme is also relevant globally. We have identified 258 authors from 35 countries, affiliated with 192 universities or other research institutions. The USA, China, England, Australia, and Germany are the most productive countries. Most authors (95%) are associated with a single publication. It is noted that Christian F. Durach and Srinivas Talluri are the most productive authors, both of whom are referenced in this research. The 91 papers are cited 3158 times on WoS, an average of 34.7 citations per article, where 28 records (31%) are responsible for 80% of total citations, all referenced in this research.

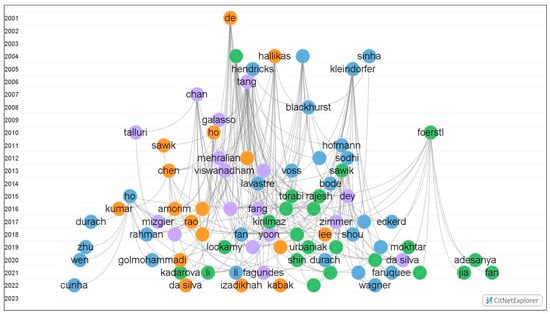

Next, CitNet Explorer was used to analyze the citation network. This software performs a scan that reveals citation links in addition to the collected articles themselves; that is, it extrapolates the main research and generates a network with more than 91 articles. Thus, 104 publications were obtained, covering the period from 2001 to 2023, with 237 citation links. Publications with the highest values for the citation score indicator are the most cited. Then, a graph was generated, where each vertex (node) represents a publication, labeled by the first author’s surname, and each edge (loop) indicates that the publication above was cited by the publication below. Figure 5 illustrates this graph, where some labels were omitted for visual reasons.

Figure 5.

Citation network.

The minimum size established as a parameter for creating a cluster was 10 citation relationships. Thus, four clusters were generated, divided into the following colors: (i) blue, 29 publications; (ii) green, 23 publications; (iii) purple, 18 publications; and (iv) orange, 17 publications. The remaining 17 publications, with a citation score of zero and no ties identified in the network, were not associated with any cluster. It appears that the starting point, that is, the oldest publication, is the work of De Boer et al.: “A review of methods supporting supplier selection”, published in 2001. The article has a citation score indicator of 12. It can be said that it influenced the emergence of the SCRM topic in suppliers, despite not meeting the criteria for fitting into the set of results of the main research, serving as a “pre-theme”.

It is also observed that the highest citation score value in the network is 28, referring to the article by Tang: “Perspectives in supply chain risk management” [1], published in 2006 by the International Journal of Production Economics. This fact is coherent, as it is a classic and seminal work for the SCRM research field in general, influencing several branches of the field. Hence, it can be considered as responsible for propelling the supplier-focused approach, a subset of SCRM. Therefore, it was used as a pillar for developing Section 3.2 of this research (SCRM from the supplier management approach). Figure 6 highlights the subnetwork of papers referencing the article by Tang [1], which can be considered as the most significant route of knowledge from 2006 to the present day.

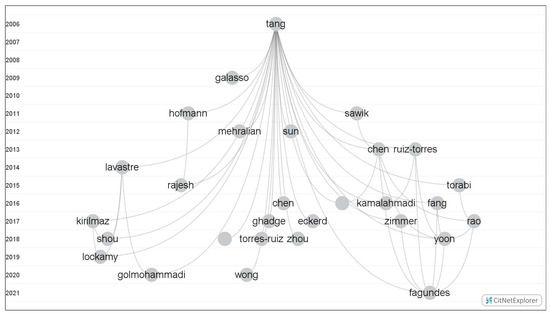

Figure 6.

Tang subnetwork.

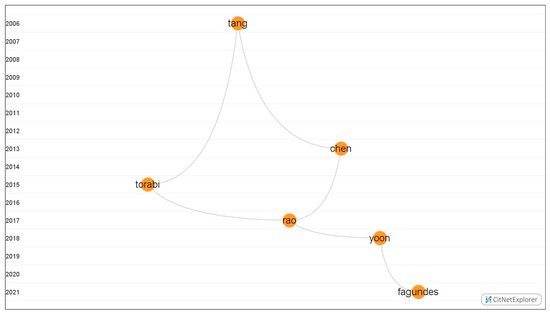

Next, the subnetwork that represents the nucleus of central publications was extracted, as shown in Figure 7. A central publication was defined as a work that has at least five citation ties with other central publications. In this way, 34 central publications were obtained, with 118 links, where the paper of Tang [1] is contained. From the core of central publications, we proposed to track the flow of knowledge between that article [1] and the most recent article in its subnetwork, published by Fagundes et al. [15] in 2021. To this end, the longest path resource was used, which returns the longest path between two nodes, considering only the essential ties for maintaining the path. The longest route subnet is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Central publications subnetwork.

Figure 8.

Longest route.

It can be seen that the subnetwork has two possible routes: (a) Tang–Torabi–Rao–Yoon–Fagundes and (b) Tang–Chen–Rao–Yoon–Fagundes. Both are based on Tang’s exposition on perspectives in the field of SCRM [1], which, as already stated, paved the way for several ramifications. The author establishes a practical guide that addresses supplier selection, order allocation, chain design, product management, demand, and information, explaining the possibility of using quantitative models to manage risks at each stage. Regarding subsequent nodes, all studies address the problem of supplier selection from a perspective that encompasses supply chain risks as essential criteria in the selection process, as raised by Tang [1]. Supplier selection is, thereby, the most significant research issue in the theme of SCRM from a supplier management perspective.

However, each of the works exhibits particularities in its approach. Chen and Wu [39] advance the body of knowledge by proposing a risk-based supplier selection method supported by FMEA. As selection criteria, the authors apply four traditional criteria regarding supplier operational efficiency (cost, quality, delivery, service) and add two new criteria (technology and productivity). Torabi et al. [13] contribute by incorporating disruptive risks (such as fires and earthquakes) in their selection framework and by generating an objective function to calculate the resilience level of a supplier base. Both reference Tang [1] as a theoretical basis for the problem of supplier selection and for understanding SCRM.

Rao et al. [21], influenced by the two previous studies, further the field by combining commercial criteria (cost, quality, delivery, etc.) and risk-related criteria (technological risks, environmental risks, social risks, etc.). The authors also contribute by introducing the elements of multi-sourcing and divisible goods in their framework, meaning that the buyer can select multiple suppliers to deliver materials simultaneously. Yoon et al. [22] contribute by also integrating risk mitigation strategies into their framework, through optimization simulations. In turn, Fagundes et al. [15] advance the literature by merging AHP and fuzzy methods to evaluate suppliers in a real supply chain context.

In light of the above, all of the aforementioned articles are used in the theoretical background of this work (Section 3): Tang [1] substantiates the understanding of SCRM ramifications and the dimensions of the supplier management approach, while the other studies substantiate analyzing current research practices regarding supplier selection, which, as demonstrated, is an essential line of research.

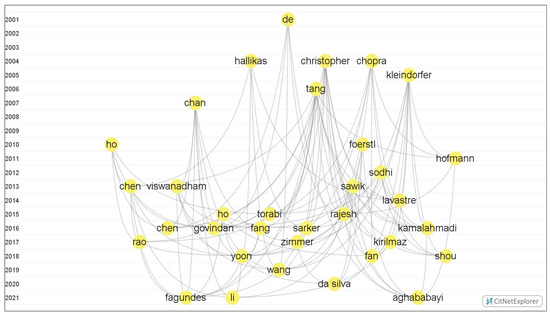

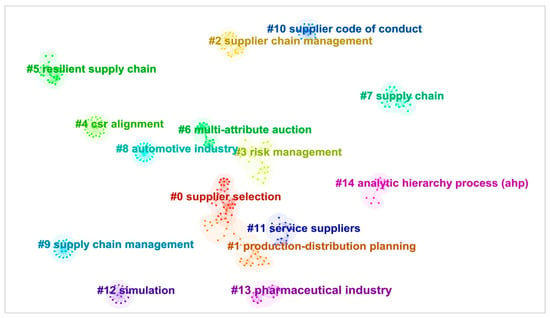

In the next step of this research, CiteSpace was used to map the research topics and their evolution over time. All analyses described below cover the period from January 2004 to January 2023, regarding all 91 articles. Initially, the network of references cited was organized into clusters to identify the most prominent research areas. Each point (node) represents a cited reference, and the lines (ties) that connect two points represent co-citation links. Thus, 53 clusters were identified, among which the 15 most relevant are displayed and labeled using terms extracted from the article titles, as shown in Figure 9. Only clusters larger than ten were selected, and only the most relevant term (cluster label) was displayed. The largest cluster is defined as cluster #0, which is supplier selection, corroborating CitNet Explorer findings.

Figure 9.

Network of references.

The most apparent reason for the predominance of the supplier selection cluster is that several authors consider it as the most critical dimension and the foundation of supplier management [6,21]. Indeed, selecting an efficient supplier base can be a decisive factor in an organization’s success [1,3,58]. However, we also propose a complementary empirical explanation: given the challenges that researchers face in accessing industrial environments [12], many companies may feel more comfortable sharing supplier performance data (without disclosing supplier names) than granting access to their internal production processes or strategic guidelines. As a result, supplier selection may become a more feasible topic for empirical studies. Moreover, it is possible to develop supplier selection simulations without relying on real industrial data.

Among the main metrics presented by CiteSpace to assist in understanding the structural characteristics of the network, the Modularity Q property presented a value of 0.9244, which indicates that the network of references obtained is divided into loosely coupled clusters. The Weighted Mean Silhouette property presented a value of 0.9895, suggesting a high homogeneity level between the clusters. Such characteristics can be expected from a recent research theme that is still in the development phase.

Table 1 lists those 15 main clusters ordered by size, homogeneity (Silhouette), average years of publication, and terms used in the title. It is observed that the most representative nucleus revolves around 2017 (cluster #0), led by the area of research in supplier selection. Other relevant issues were found between 2011 and 2019, so the data reaffirms the recent effervescence of the topic.

Table 1.

Clusters.

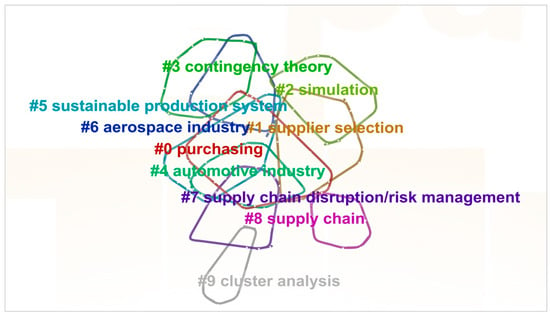

Then, the keyword network was generated, as shown in Figure 10. The main goal is to shed light on the keywords most associated with the research theme to deepen the research profile investigation concerning research topics and methods that authors use. This graphic representation shows the 10 keywords most used in the articles, regardless of the previous area clusters, and shows the connections among keywords.

Figure 10.

Keywords.

Therefore, in addition to basic terms that are commonly associated with this field of knowledge, such as purchasing and supply chain, it is possible to infer the following:

- The term supplier selection (#1) is the most relevant, after the generic term purchasing, which corroborates our previous findings. It also relates directly to the dimension “selection” from the supplier management approach as listed by [1].

- The term simulation (#2) refers to a research method that involves applying quantitative methods, logical modeling tools, and similar methods. Thus, it is the most used research method in the field. The main reason for the extensive use of simulation in the literature is its ability to model dynamic environments such as supply chains and to quantify risks [45,48]. Simulation techniques can also account for inherent uncertainty in data parameters (e.g., demand, cost, capacity) through uncertainty programming approaches such as fuzzy, possibilistic, or stochastic programming [13,47]. Therefore, its applicability becomes evident in key topics such as supplier selection based on dynamic criteria, as in the case of shifts in consumer demand for sustainable products [48]; and optimal order allocation among suppliers, as in the case of order rescheduling following a disruptive event at a supplier [13]. Moreover, as previously addressed, researchers often face difficulties conducting case studies and empirical research within industrial settings [12], which may further contribute to the substantial number of simulation-based studies.

- The term automotive industry (#4) indicates that it is the main study environment. This is reasonable, given that the automotive industry constitutes an ideal setting for supply chain risks due to its inherent characteristics, such as just-in-time supply systems with high complexity, cost, and safety requirements [22]; strong power and influence of manufacturers over suppliers [55]; and prevailing trends such as the globalization of supply chains, outsourcing, and efficiency-driven strategies—all of which contribute to a high vulnerability to supply chain disruptions [37].

- The term sustainable production system (#5) indicates a high relevance of approaches dedicated to sustainability, within the concept of ESG (environmental, social, and corporate governance). ESG is also the pillar of the identified research cluster #4 (CSR alignment).

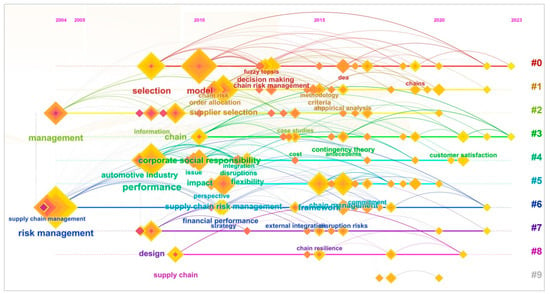

Then, to understand the evolution of the research area over the years, the keyword network was reorganized into a timeline configuration, between 2004 and 2023, as shown in Figure 11. In this graphic representation, the aforementioned 10 most representative keywords denote research timelines, listed on the right side of the figure (#0 to #9), with each timeline encompassing a contingent of relevant keywords used in studies of that line over time. The larger the font size, the higher the occurrence of the keyword. Thus, it is noted that the most used keywords include risk management, performance, model, and supplier selection.

Figure 11.

Keyword timeline.

At the very beginning of the development of the theme, around 2004, the main keywords were management, supply chain management, and risk management. These are general terms about this area of knowledge and therefore coherent for inaugurating the research theme and influencing future elaborations. In parallel with the evolution of knowledge over the years, we can see the expansion and branching of research alternatives.

As evidenced by the terms found in lines #0, #1, and #2, the initial term management triggered an area of research focused on supplier selection, leading to empirical analysis and modeling with decision-making support methods such as AHP, fuzzy Topsis, and DEA. Several examples are provided in Section 3.2 (SCRM from the supplier management approach). On the other hand, the initial terms supply chain management and risk management gave rise to terms that denote different study focuses, such as financial performance, design, integration, information, strategy, corporate social responsibility, and customer satisfaction, among others. These concepts are also mentioned throughout Section 3. In short, the keyword analysis corroborates previous evidence about the varied relevant approaches already applied to the theme of SCRM in suppliers. Therefore, this research profile adequately answers RQ1.

4.2. Research Trends, Future Directions, and Conceptual Framework

In order to objectively determine current and future research trends, we combined the bibliometric results from the software with a manual analysis of the literature on SCRM in suppliers. In order to further investigate the topic and ensure even more robustness of the results, we also manually analyzed the general literature on SCRM, aiming to identify SCRM trends that may utilize the supplier management approach but were not covered by the search terms of the main research, as explained in Section 2 (Materials and Methods).

During this research’s design phase, it became clear that we needed to investigate which major issues companies should be concerned about, as well as the researchers interested in the subject, when dealing with suppliers in order to apply SCRM effectively. This requirement was filled during the literature review process, when we discovered that Tang [1] had listed five main issues (dimensions) of supplier management in the context of risk. From this moment on, we managed to review research developments in each of the author’s proposed dimensions, as shown in Section 3.2 (SCRM from the Supplier Management Approach) and Section 4.1 (Research Profiling). Nevertheless, nearly two decades later, we feel the need to verify if those topics are prone to an update.

Based on the CiteSpace findings, we identified that supplier selection is the most researched topic, simulation is the preferred method, and the automotive industry is the main research environment. Table 1 also allows us to deduce three major moments in the evolution of SCRM research with a focus on suppliers. The first moment, from 1999 to 2008, represented the initial developments that related the topic of risk to supply chain management in order to obtain competitive advantages and distribute risks among the members of the chain [65]. The major trend of the period, centered in the year 2006, was to analyze the supplier base and the chain that interconnects the organizations (cluster #2). This moment is covered by the research of Tang [1], which is also the most relevant of this period and drove the branches focused on suppliers, a subset of SCRM, as we identified in the CitNet Explorer citation network.

The second period, from 2009 to 2018, represented a 68% growth in the topic and determined the research trend on supplier selection, centered in 2017 (cluster #0). As we identified through CiteSpace and CitNet Explorer, this is the topic that has attracted the most researchers in the area to date and constitutes the most significant knowledge path. This topic demonstrates continuity in relation to Tang [1], who pointed out “supplier selection” as one of the major dimensions of the supply management approach. Some of the main developments of this dimension in the SCRM literature are presented in Section 3.2 (SCRM from the Supplier Management Perspective). Some authors also explored the chain as a whole and considered the risks of multi-tier suppliers to build a more robust selection model [66,67,68,69,70]. We address the overall importance of accounting for multi-tier supplier risks in Section 3.1 (Supply Chain Risks of Direct and Indirect Suppliers).

However, although it has already been extensively explored, the topic of supplier selection is not exhausted, since new quantitative methods and new decision criteria are still being incorporated into the problem of supplier selection, which continues to be a current research trend. Thus, we identified that this topic also continues to be part of future research directions, mainly the observation of the indirect supply chain, with the search for the selection of suppliers that have resilient and sustainable chains, and the development of new hybrid analysis and selection methods, combining existing techniques, including integrating with the application of AI. These observations are included as future research directions in articles published since 2020 [15,23,38,44,48].

Finally, the third major moment, which is the current moment, reveals the main contemporary research trend: corporate social responsibility (CSR) alignment, centered in 2019 (cluster #4). Despite being an emerging topic, it was quickly consolidated among the five main research clusters throughout the historical series. The analysis of Figure 10 also highlights the relevance of this topic through the term sustainable production systems. Thus, this trend fits under the ESG (environmental, social, and governance) concept and represents a discontinuity in relation to Tang [1], who does not mention aspects related to ESG. Therefore, it constitutes a new research dimension.

ESG concerns sustainability and compliance issues, where companies seek to generate positive externalities and mitigate the negative impact of their operations on society and the environment [71], as this alignment began to generate image benefits with suppliers, stakeholders, and public opinion [72]. Therefore, if, previously, decision making in supplier management was concerned with aspects such as performance [73], financial health [74], order optimization [75], dependency, and power relations [76] (all covered by the dimensions of Tang [1]), our research shows that, in this third moment, companies also begin to have great concern with sustainable supply chains.

Obviously, ESG has its own field of study in the scientific community, as well as its own risks, which are not our focus in this paper. What we address here is the direct relationship between ESG risks and supplier management, considering the SCRM research field. Thus, our research results demonstrate that ESG risks have been incorporated as an indispensable part of supplier management, exerting influence on SCRM practices. We have conducted manual screening and verified the following:

- Considering the 33 articles published since 2020 in our main sample of 91 articles, 11 (33%) directly address the ESG dimension.

- Researchers interested in this trend can start with the review by Da Silva et al. [77], which offers a broad and comprehensive view of the specific literature on sustainability-related supplier risk management.

Thus, we point out that the ESG dimension represents the current moment, but also serves as a guideline for future research, where numerous issues can be explored in greater depth, such as the development of sustainable suppliers; customer satisfaction related to sustainable practices; mechanisms for in-depth collaboration between different levels of the chain to reduce the risk of undesirable practices in ESG; mediators between CSR alignment and ROI (return on investment); coercive pressures on suppliers for sustainable innovation. These observations are included as future research directions in articles published from 2020 onwards [78,79,80,81].

Then, by performing manual screening on the complementary sample of 46 SCRM articles, we were able to identify research on IT (information technology) risks as another major current trend and future guideline. In this case, we are not referring to the development of software and technological applications for management, since the IT area is also a vast field of research in its own right, as is ESG. Instead, we are referring to the efforts made by researchers and companies to incorporate risks related to digital transformation as an essential part of supplier management, especially information security risks and the increasing use of artificial intelligence in supply chains in companies. This trend also represents a discontinuity in relation to Tang [1], and therefore constitutes a new research dimension. We found the following:

- Considering the 18 articles published since 2020 in our complementary sample of 46 articles, 5 (28%) deal directly with the IT dimension.

- Researchers interested in this trend can start with the reviews by Deiva Ganesh and Kalpana [16] and Creazza et al. [82], which offer broad and comprehensive views on the current literature.

A deeper observation also allows us to outline future research perspectives, as the two aforementioned reviews follow different approaches, which tend to give rise to two relevant lines of research: Creazza et al. [82] address cybersecurity risks in SCRM while Deiva Ganesh and Kalpana [16] address the future of AI in SCRM.

In this way, the cybersecurity line identifies risks related to information security, data privacy, and IT governance. Several companies require suppliers to comply with the company’s privacy and security policies [82]. In this sense, Faruquee et al. [57] already point out that joint problem solving between the company and supplier is a mechanism that drives governance and reduces risks, and this trust developed between partners cannot be fully replaced by digital tools. This is a step towards deeper investigations, in the future, on governance in the era of digital transformation. For example, it opens up the possibility of examining whether digital tools can drive trust.

Regarding the AI research line, the main future direction is the development of responsible and auditable algorithms in supply chains, which was addressed by Refs. [83,84,85]. These authors point to AI as a mechanism for integration with suppliers but draw attention to the lack of explainability of most current AI techniques and call for developments that make AI more reliable in the future. Another research possibility also arises from the merger of the two lines: since suppliers are sources of risk and many companies require compliance from their suppliers [82], the possibility of investigating AI audits in suppliers in the future opens up.

We also highlight some of the most relevant suggestions that have emerged in the last 3 years outside the ESG-IT dyad, as we believe that they can serve as inspiration for future research. These suggestions correspond to the inclusion of new elements in the assessment of risk scenarios related to suppliers, such as stochastic demand [34], supplier complexity [38], demographic variations [51], perishable products [86], the integration of supplier training with the organization’s strategic objectives [29], and its influence on the concentration of the supplier base [58].

These topics are particularly relevant from a managerial standpoint, considering that different supply chain strategies may be more suitable for different types of products and different levels of complexity [87] and risks can be difficult to perceive in complex networks [88]. For instance, the combination of lean and agile approaches for managing seasonal products can propel both supply chain performance [87] and resilience [61]. However, all these topics represent continuity in relation to the article by Tang [1] and do not represent new research dimensions, as they are directly connected to the design, selection, allocation, contract, or relationship dimensions.

Regarding the research methodology, we identified multiple empirical studies in the last 3 years [29,38,58], which also constitutes a trend. This proves the relevance of the empirical approach and its significant growth, since Ho et al. [12] pointed out the low contingent of empirical studies in SCRM due to the difficulties of researchers in accessing industries.

Still, we urge researchers to carry out more empirical studies, especially with the participation of companies’ managers. This trend should be expanded in the future, as it promotes integration between academia and industry, ensuring that scientific developments are aligned with the reality and needs of the market. Furthermore, as noted by Molinaro et al. [58], future research directions point to the participation of suppliers’ managers, in addition to the managers of the focal company.

Based on this analysis, we felt the need to update the major dimensions of supplier management, presented by Tang [1], to include the two dimensions arising from emerging research trends (ESG and IT). It may be posited that ESG and IT exhibit distinctive characteristics within the supplier management perspective and do not fully align under the scope of existing dimensions. Furthermore, their increasing strategic relevance suggests that treating them merely as subcomponents of broader dimensions may no longer be appropriate. Instead, our findings substantiate the proposition that ESG and IT should be conceptualized as independent dimensions within the supplier management domain. Thus, we answer RQ2 and present, as the final result of this research, the conceptual framework for SCRM research in supplier management, illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Conceptual framework for SCRM in supplier management.

The primary managerial implication of this framework is the recommendation for companies to critically reassess their organizational structures by allocating specialists to oversee ESG and IT within the supplier management function, thereby enhancing risk governance. This means either expanding the supplier management team or assigning professionals from ESG and IT departments to handle dedicated supplier-related matters.

Still from a practical standpoint, our findings support strategic decision making by highlighting emerging compliance challenges associated with the unregulated deployment of AI technologies, not only within the focal firm but across its supply network. Managers can leverage these findings, for instance, to raise awareness about the development of compliance programs that set auditable standards for the use of AI in collaborative supplier engagement. A similar rationale applies to the integration of ESG practices across the supply chain, which can be positioned as a strategic and mandatory asset for long-term resilience and stakeholder alignment.

5. Conclusions

We addressed the conceptual gap found in the literature and provided an up-to-date framework consisting of the major dimensions in supplier management, grounded in the findings of our systematic analysis and review. Additionally, we contributed to the advancement of the SCRM body of knowledge by exploring the supply-side perspective through a comprehensive and structured research profile that offers valuable guidance for both researchers and practitioners, providing information about the most prominent cluster (supplier selection), method (simulation), environment (automotive), authors, issues, research trends, and future directions. Thus, this study has answered RQ1 and RQ2 and has achieved its objectives.

Researchers and academics can find in this article clues for current research and a novel guide to supplier management risks (a subset of SCRM), encompassing a broad and comprehensive research profiling trends and future directions. Meanwhile managers can turn to this research for knowledge on the major dimensions that companies must consider when they deal with suppliers, including up-to-date topics on supplier-focused ESG and IT, as well as for technical concepts about inventory, multi-sourcing, and multi-level supply chains, among others. For instance, managers can use our findings to start applying efforts in mapping risks of their indirect supplier network or discussing compliance guidelines for IT and ESG in joint problem solving with suppliers.

Regarding limitations, this study does not propose addressing the stages of SCRM, the tools for risk assessment, or an empirical study, which were not part of the research goals. Only articles published in the WoS database were retained, although we consider the database and sample size (similar to other relevant reviews found in the literature) enough to ensure quality and reliability of data. Moreover, as also acknowledged by Wicaksana et al. [18], certain qualitative interpretations may inherently involve an element of subjectivity. Nevertheless, this study is grounded in a methodologically rigorous design, including the systematic triangulation of data sources, transparent documentation of analytical steps, and multiple layers of validation and cross-checking. These procedures collectively reinforce the robustness, transparency, and replicability of the findings, minimizing potential biases and enhancing the overall credibility of the research outcomes.

As recommendation for new studies, authors can analyze other aspects relevant to the theme, such as the use of risk management tools in suppliers, or investigate other approaches of SCRM (product, demand, information) besides the supply/supplier approach. Authors can also follow one of the many research clues that we provide, especially regarding the dimensions of ESG and IT, both of which set a strong precedent for the future of research in the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.d.S. and U.R.d.O.; methodology, C.R.d.S. and U.R.d.O.; validation, C.R.d.S., U.R.d.O., and V.A.; formal analysis, C.R.d.S., U.R.d.O., and V.A.; investigation, C.R.d.S.; resources, C.R.d.S., U.R.d.O., and V.A.; writing—original draft, C.R.d.S. and U.R.d.O.; writing—review and editing, C.R.d.S., U.R.d.O., and V.A.; visualization, C.R.d.S., U.R.d.O., and V.A.; supervision, U.R.d.O.; project administration, U.R.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FAPERJ—Carlos Chagas Filho Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Process E-26/211.508/2021–APQ1 (SEI Process 260003/015086/2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tang, C.S. Perspectives in supply chain risk management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 103, 451–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilmaz, O.; Erol, S. A proactive approach to supply chain risk management: Shifting orders among suppliers to mitigate the supply side risks. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2017, 23, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Ripple effect modelling of supplier disruption: Integrated Markov chain and dynamic Bayesian network approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3284–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Peers, Y.; Wang, Y.; Repasky, T. Mitigating upstream disruptions: Effects of extended inventories in first- and second-tier suppliers. J. Oper. Manag. 2024, 70, 1261–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Stevenson, M. A review of supply chain risk management: Definition, theory, and research agenda. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, R.; Ghorabaee, M.K.; Govindan, K.; Esmaeili, A.; Nobar, H.B.K. Evaluation of sustainable supply chain risk management using an integrated fuzzy TOPSIS- CRITIC approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalahmadi, M.; Mellat-Parast, M. Developing a resilient supply chain through supplier flexibility and reliability assessment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Jena, S.K.; Kamble, S.; Misra, D.; Tiwari, M.K. Impact of financial risk on supply chains: A manufacturer-supplier relational perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 7090–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuj, I.; Mentzer, J.T. Global supply chain risk management strategies. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 192–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, O.; Musa, S.N. Identifying risk issues and research advancements in supply chain risk management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 133, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A.; Wallenburg, C.M. Dealing with supply chain risks: Linking risk management practices and strategies to performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.; Zheng, T.; Yildiz, H.; Talluri, S. Supply chain risk management: A literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5031–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, S.; Baghersad, M.; Mansouri, S. Resilient supplier selection and order allocation under operational and disruption risks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 79, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryannis, G.; Validi, S.; Dani, S.; Antoniou, G. Supply chain risk management and artificial intelligence: State of the art and future research directions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2179–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, M.V.C.; Hellingrath, B.; Freires, F.G.M. Supplier Selection Risk: A New Computer-Based Decision-Making System with Fuzzy Extended AHP. Logistics 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, A.D.; Kalpana, P. Future of artificial intelligence and its influence on supply chain risk management—A systematic review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Murino, T.; Gebennini, E.; Morea, D.; Bottani, E. A literature review on quantitative models for supply chain risk management: Can they be applied to pandemic disruptions? Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 170, 108329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksana, A.; Ho, W.; Talluri, S.; Dolgui, A. A decade of progress in supply chain risk management: Risk typology, emerging topics, and research collaborators. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 7155–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colicchia, C.; Strozzi, F.; Wilding, R. Supply chain risk management: A new methodology for a systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Ravi, V. Supplier selection in resilient supply chains: A grey relational analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Xiao, X.; Goh, M.; Zheng, J.; Wen, J. Compound mechanism design of supplier selection based on multi-attribute auction and risk management of supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 105, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Talluri, S.; Yildiz, H.; Ho, W. Models for supplier selection and risk mitigation: A holistic approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3636–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, M.A.; Yazdi, A.K.; Ocampo, L.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. An integrated grey-based multi-criteria decision-making approach for supplier evaluation and selection in the oil and gas industry. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 406–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. Data envelopment analysis application in sustainability: The origins, development and future directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Jin, J. Knowledge mapping of supply chain risk research based on CiteSpace. Comput. Intell. 2020, 36, 1686–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, U.R.; Espindola, L.S.; Silva, I.R.; Silva, I.N.; Rocha, H.M. A systematic literature review on green supply chain management: Research implications and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.F.; Qiu, M.; Gupta, J.N. Improving supplier capability through training: Evidence from the Chinese Automobile Industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Wiengarten, F.; Choi, T.Y. Supplier–supplier coopetition and supply chain disruption: First-tier supplier resilience in the tetradic context. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1041–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, T.; Closs, D. The risk of second-tier supplier failures in serial supply chains: Implications for order policies and distributor autonomy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 186, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Al Khaled, A. A hybrid ensemble and AHP approach for resilient supplier selection. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Wee, H.M. A resilient global supplier selection strategy—A case study of an automotive company. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 87, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, C. Mitigating supply disruption risks by diversifying competing suppliers and using sales effort. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 255, 108637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.R.; Whitman, L.E.; Malzahn, D. Methodology to mitigate supplier risk in an aerospace supply chain. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 9, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabellini, M.; Mak, S.; Schoepf, S.; Brintrup, A.; Regattieri, A. A continuous training approach for risk informed supplier selection and order allocation. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2025, 13, 2447035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thun, J.H.; Hoenig, D. An empirical analysis of supply chain risk management in the German automotive industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissuwa, F.; Durach, C.F.; Choi, T.Y. Selecting resilient suppliers: Supplier complexity and buyer disruption. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 253, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-S.; Wu, M.-T. A modified failure mode and effects analysis method for supplier selection problems in the supply chain risk environment: A case study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 66, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, A.; Bigham, B.S.; Zahedi-Seresht, M. Supplier Selection Utilizing AHP and TOPSIS in a Fuzzy Environment Based on KPIs. Contemp. Math. 2025, 6, 574–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadikhah, M.; Saen, R.F.; Zare, R.; Shamsi, M.; Hezaveh, M.K. Assessing the stability of suppliers using a multi-objective fuzzy voting data envelopment analysis model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, J.; Montes-Sancho, M.J. Nexus supplier transparency and supply network accessibility: Effects on buyer ESG risk exposure. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 45, 895–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, A.I.; Kavian, A.; Khalilzadeh, M.; Brauers, W.K. CLUS-MCDA: A novel framework based on cluster analysis and multiple criteria decision theory in a supplier selection problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 118, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, C.-H.; Zhou, L.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Tsai, S.-B. A model integrating environmental concerns and supply risks for dynamic sustainable supplier selection and order allocation. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Torres, A.J.; Mahmoodi, F.; Zeng, A.Z. Supplier selection model with contingency planning for supplier failures. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 66, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K. Supplier selection for managing supply risks in supply chain: A fuzzy approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 79, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, P.; Curcio, E.; Almada-Lobo, B.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.; Grossmann, I.E. Supplier selection in the processed food industry under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 252, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.-T. Dynamic procurement risk management with supplier portfolio selection and order allocation under green market segmentation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, F.; Shukla, M.; Dhurkari, R.K. Design of multi-criteria decision framework for supplier evaluation and supply chain sustainability risk (SCSR) management. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 1730–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, M.; Louis, M. A multi-agent based framework for supply chain risk management. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2011, 17, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Farooq, S. Manufacturing planning and control driven supply chain risk management: A dynamic capability perspective. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 167, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengarten, F.; Humphreys, P.; Gimenez, C.; McIvor, R. Risk, risk management practices, and the success of supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Dani, S.; Kalawsky, R. Supply chain risk management: Present and future scope. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2012, 23, 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fan, H.; Lee, P.K.; Cheng, T. Joint supply chain risk management: An agency and collaboration perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G.C.; de Oliveira, U.R.; Lima, G.B.A.; Fernandes, V.A. Risk management in the import/export process of an automobile company: A contribution for supply chain sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackhurst, J.V.; Scheibe, K.P.; Johnson, D.J. Supplier risk assessment and monitoring for the automotive industry. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruquee, M.; Paulraj, A.; Irawan, C.A. Strategic supplier relationships and supply chain resilience: Is digital transformation that precludes trust beneficial? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 1192–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, M.; Danese, P.; Romano, P.; Swink, M. Implementing supplier integration practices to improve performance: The contingency effects of supply base concentration. J. Bus. Logist. 2022, 43, 540–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala, R.; Schoenherr, T.; Xie, C. Assessing and managing risks using the Supply Chain Risk Management Process (SCRMP). Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 16, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuj, I.; Mentzer, J.T. Global Supply Chain Risk Management. J. Bus. Logist. 2008, 29, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Sehrish, H. Impact of lean and agile strategies on supply chain risk management. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2021, 32, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Glasen, P.C.; Straube, F. Disruption causes and disruption management in supply chains with Chinese suppliers: Managing cultural differences. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 843–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizgier, K.J.; Pasia, J.M.; Talluri, S. Multiobjective capital allocation for supplier development under risk. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 5243–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talluri, S.; Narasimhan, R.; Chung, W. Manufacturer cooperation in supplier development under risk. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallikas, J.; Karvonen, I.; Pulkkinen, U.; Virolainen, V.-M.; Tuominen, M. Risk management processes in supplier networks. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 90, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockamy, A.; McCormack, K. Modeling supplier risks using Bayesian networks. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2012, 112, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanadham, N.; Samvedi, A. Supplier selection based on supply chain ecosystem, performance and risk criteria. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 6484–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, K.; Fröhling, M.; Breun, P.; Schultmann, F. Assessing social risks of global supply chains: A quantitative analytical approach and its application to supplier selection in the German automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, A.; Yang, B.; Bin Iqdara, F.W.; Yang, Y. Improving sustainability performance through supplier relationship management in the tobacco industry. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 25, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Jepsen, M.B. Supplier risk assessment based on trapezoidal intuitionistic fuzzy numbers and ELECTRE TRI-C: A case illustration involving service suppliers. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2016, 67, 339–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ruiz, A.; Ravindran, A.R. Multiple criteria framework for the sustainability risk assessment of a supplier portfolio. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4478–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, L.; Su, J.; Zhang, W. Do Suppliers Applaud Corporate Social Performance? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Ho, W.; Clegg, B. Strategic supplier performance evaluation: A case-based action research of a UK manufacturing organisation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 166, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.; Hübner, D.; Wagner, S.M. Managing Financially Distressed Suppliers: An Exploratory Study. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, T. Supplier selection in make-to-order environment with risks. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 53, 1670–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavastre, O.; Gunasekaran, A.; Spalanzani, A. Effect of firm characteristics, supplier relationships and techniques used on Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM): An empirical investigation on French industrial firms. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 3381–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.M.; Ramos, M.O.; Alexander, A.; Jabbour, C.J.C. A systematic review of empirical and normative decision analysis of sustainability-related supplier risk management. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y. Gaining customer satisfaction through sustainable supplier development: The role of firm reputation and marketing communication. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 154, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotnick, S.A.; Sobel, M.J. Collaboration with a supplier to induce fair labor practices. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 302, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Buyer-supplier CSR alignment and firm performance: A contingency theory perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]