Abstract

Background: Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline are common in older adults. The aims of this study were (i) to assess the frequency of depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in users of municipal home care services and (ii) to explore factors that may pertain to seeking in-depth neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup, if recommended. Methods: The study was mainly conducted in low-resource areas of south-western Greece. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Clock Drawing Test (CDT) were employed. The study included the tracking of whether participants sought medical consultation within 12 months after receiving the recommendation for further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup. Results: The study encompassed 406 individuals. Cognitive deficits were detected in 312 (76.84%) study participants, of whom only 82 (26.28%) had received the diagnosis of a mental or neurological disorder. Depressive symptoms were detected in 236 (58.27%) individuals, of whom only 18 (4%) had received the diagnosis of a mental or neurological disorder. Only just over a third of individuals consulted physicians. Reluctance towards in-depth neuropsychiatric workup mainly derived from a lack of insight and fears related to COVID-19. Previously diagnosed neuropsychiatric disorders slightly correlated with the decision to consult a physician. Conclusions: Developing pragmatic cognitive and mental healthcare services to address the needs of older people with disabling chronic disorders who live in low-resource settings is urgently needed.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Depression and dementia, being among the major contributors to the overall global burden of disease and to years lived with disability in people aged 55 or older, remain underdiagnosed in communities living in low- resource areas, such as remote and/or secluded ones, which are mainly inhabited by older people [1,2,3].Low educational level, lack of social capital, social isolation, administration of environmentally harmful farming methods, and inadequate healthcare and housing facilities may partially explain the high rates of depression and cognitive impairment in such areas [1,4,5,6]. In addition, rural populations tend to have a higher prevalence of specific health conditions, including hypertension, heart diseases, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, and cancer [7]. Notably, the prevalence of depression among older adults with multiple health conditions was recently found to be higher in rural areas of India compared to urban areas [8]. The detection, diagnosis and treatment of depression and cognitive deficits in low-resource areas is undermined by the reluctance of older individuals residing in these areas to seek help for complaints related to mental and/or cognitive health or to be referred to mental healthcare services because of long distances, high travel costs, low mental health literacy and/or low psychological openness and stigmatization fears [9,10,11,12].

1.2. Study Aims

The aims of this pragmatic study were (i) to shed light on the frequency of depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in older users of municipal home care services in rural and semi-urban regions of south-western parts of Greece, the users of which typically have several comorbidities and embody a particularly vulnerable population; (ii) to investigate the relationship of these symptoms with demographics, clinical characteristics, and remoteness of residence; and (iii) detect clinical and socioeconomic characteristics of home care service users who screened positive for cognitive impairment and/or depression that pertain to their decision to seek mental and cognitive care or not within 12 months after their referral to such care services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study sample comprised 406 individuals aged 58 years and older, permanently residing in the regions of Epirus, Western Greece and Peloponnese, being parts of the 6th Regional Health Authority of Greece, and who were beneficiaries of municipal home care services. They represented 12.5% of all service users and 2.5 individuals per 1000 of the total population of the 14 municipalities where the study took place. Users of such services are individuals who are not independent in daily living activities due to chronic disorders, live alone, are deprived of family care, and whose income does not allow them to secure the required services for improving their quality of life.

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted between 2020 and 2022, within the frames of Work Package 8—“Improving access to health and social services for those left behind” of the Joint Action Health Equity Europe Initiative (JAHEE). The JAHEE provided a significant platform for member states to collaborate in addressing health disparities and striving for enhanced equity in health outcomes across all societal groups, in participating countries, and on a broader European scale [13]. The study fully complies with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and its revisions. It has been approved by the Patras General University Hospital Bioethics Committee (256/13.09.2022).

2.3. Training of Healthcare Professionals of Municipal Home Care Services

Healthcare professionals (nurses and social workers) of municipal home care services operating in the regions of Peloponnese, Ionian Islands, Epirus and Western Greece were invited to attend a two-hour online interactive training session focusing on detecting depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits in aging with brief, reliable instruments. Such training was necessary for the familiarization of the staff with the employed screening tools and for the standardization of the diagnostic procedures implemented in the study. The session was organized by the University of Patras and the 6th Regional Health Authority of Peloponnese, Ionian Islands, Epirus, and Western Greece, and was delivered via Zoom.

2.4. Sociodemographic and Somatic Clinical Data Collection

The pragmatic diagnostic workup of users of municipal home care services who consented to participating in the study encompassed sociodemographic and clinical data collection, i.e., age, sex, education level, marital status, occupation, individual medical history, medication, smoking habits and alcohol consumption. Somatic diseases that were considered in the calculation of the total number of comorbidities of each study participant included: hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation/arrhythmia, diabetes mellitus, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, thyroidopathy, other endocrinological conditions (e.g., osteoporosis), rheumatological conditions, hematological diseases, neurological disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, urological/nephrological diseases, and chronic pain syndrome.

The accessibility and remoteness of the place of residence of each participating home care service user was captured with the Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Greece (ARI(gr)), in the development of which particular characteristics of Greece were taken into account (e.g., area–population ratio, population distribution, insular space, etc.) [2]. The ARI(gr) provides a continuous scale of values ranging from 0 (reflecting high accessibility) to 20 (indicating high remoteness). These scores are calculated based on road distance measurements originating from over 13,000 settlements to service centers situated throughout Greece. The selection of these service centers is contingent upon population size, with larger settlements signifying heightened levels of activity, whether economic or otherwise. ARI(gr) functions as a relative accessibility gauge, employing a location quotient methodology [14]. This approach entails the division of the travel time to a specific place (i.e., a service center) by the average travel time of all locations within the study area to reach their nearest respective destinations. Consequently, this accessibility/remoteness indicator conveys a relative measure, elucidating the extent to which a location is distanced from service centers, such as cities, relative to all other locations within the study area.

2.5. Procedures for Detecting Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Deficits

The presence of depressive symptoms and/or cognitive deficits was assessed with the following:

- The short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15);

- The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE);

- The Clock Drawing Test (CDT).

The GDS-15 is a well-established screening tool for depression in older adults [15]. A score of five or higher on the GDS-15 is typically indicative of depressive symptoms. The sensitivity and specificity of the tool are approximately 80% [16], and its use is recommended in the diagnosis of late-life depression in primary care [16].

The MMSE is a brief, widely used cognitive screening tool covering various domains, including orientation, memory, attention, language, and visuospatial skills, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment [17]. A score of 26 points (86.7% of the total score) is considered to be the optimal cut-off to detect cognitive impairment [18,19,20]). The sensitivity and specificity of the tool in detecting cognitive impairment are approximately 60% and 76%, respectivel [18,19,20]. The MMSE, with its good validity, serves as a safety measure for detecting individuals who should be referred to further medical evaluation [18,19]. Due to high rates of illiteracy among the study sample and/or vision loss forming sources of bias, items presupposing the completion of primary education or intact visual function were not considered in the assessment of the cognitive function of the respective individuals. In these cases, the cut-off value for detecting cognitive impairment with MMSE items was defined as a score lower than 86.7% of the highest score the examinee could receive based on all items that were administered. For the shake of homogeneity and standardization, a percentage-based approach was employed for reporting performance of participants on the MMSE.

Cognitive function was further examined using the Clock Drawing Test (CDT). The CDT is a brief screening instrument that evaluates a wide range of cognitive domains such as auditory comprehension, sustained attention, visuospatial ability, memory, abstract thinking, planning, motor execution, and executive function [21,22]. The simple, well-established three-point scoring system, which is used in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, was employed [22]). The values of areas under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, ranging approximately between 0.80 and 0.90, point out that this scoring system can be considered clinically useful in distinguishing between people without cognitive impairment and individuals with a mild or major neurocognitive disorder [22,23]. Scores lower than three points were considered abnormal. The combination of these assessments allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of cognitive function and depressive symptoms among the study participants. The scoring of MMSE and GDS was supervised by old-age psychiatrists involved in the study. Individuals received a medical information note. Provided that cognitive impairment and/or depressive symptoms were detected based on abnormal scores on MMSE or CDT or both, and/or the GDS total score was five or higher, individuals were referred to further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup.

2.6. Data Collection Regarding Further Neuropsychiatric Evaluation

The study also included the tracking of whether participants sought medical consultation with a physician within 12 months after receiving the medical information note with the recommendation for further neuropsychiatric evaluation. The data obtained were visualized in thematic maps using advanced Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques (qGIS) [24]. Study participants who did not consult physicians were asked for the reason for their reluctance by the staff of the home care services. Potential reasons included financial difficulties, unavailability of a care partner, concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, and lack of insight.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Python version 3.10, utilizing libraries such as pandas, matplotlib, and seaborn for data processing and visualization. Python was selected due to its versatility in handling large, real-world datasets, the transparency it offers for custom-built pipelines, and because of its adaptability to a wide range of analytical tasks. Python enables reproducible, open-access statistical workflows such as those used in this study [25]. The core libraries employed included pandas for data management, cleaning, and preparation, and matplotlib and seaborn for producing visualizations.

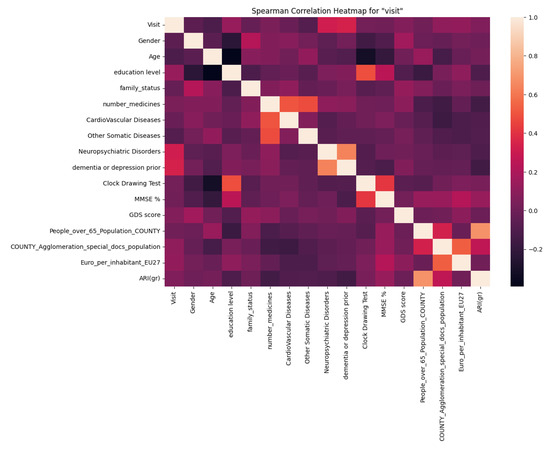

Prior to analysis, the dataset was cleaned to ensure consistency and compatibility across variables. Data cleaning included replacing missing values, empty strings, and formatting elements (such as dashes) with zeros, followed by converting all variables to numeric format. These steps were necessary to prepare the data for correlation analysis, which focused on associations between consulting a physician or not and demographic, clinical and socioeconomic parameters. Given the presence of ordinal variables, the fact that several variables did not follow a normal distribution and the potential for non-linear relationships within the dataset, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used in place of Pearson’s. Spearman’s method is more appropriate in such contexts, as it captures monotonic associations and remains robust in the presence of outliers or non-normally distributed data [26,27].

After computing the Spearman correlation matrix, the results were visualized using grayscale heatmaps to highlight the strength and direction of associations between variables. Correlation coefficients (ρ) range from −1 to +1, where values close to zero indicate weak or no association, and values approaching ±1 reflect stronger monotonic relationships. For the interpretation, we applied the following classification: ρ < 0.2 as negligible, 0.2–0.4 as low, 0.4–0.6 as moderate, 0.6–0.8 as marked, and values above 0.8 as high correlation [27].

All results—including correlation coefficients, associated p-values, and sample sizes—were exported to Excel files for documentation and further analysis. This workflow allowed for a systematic and transparent examination of variables associated with seeking further cognitive and mental diagnostic workup.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

The sociodemographic and clinical data of users of municipal home care services who participated in the study are presented in Table 1. The participants had an average age of 81.03 years, with females constituting 75% of the sample. The preponderance were widowers (53.8%) and 57.5% identified themselves as farmers, while the mean duration of education was 4.0 years reflecting the demographic, educational, and occupational characteristics of the communities where study participants resided. Among the 335 individuals for whom comorbidity data was available, all had an average of 3.71 comorbidities and were on medication, with 6.11 different medicines on average. Hypertension and dyslipidemia were the most prevalent comorbidities in this population.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study sample.

3.2. Cognitive Performance and Depressive Symptoms

Cognitive performance necessitating further diagnostic workup was observed in 311 (76.41%) of home care service users, who were assessed with MMSE and CDT. In particular, the MMSE performance of 312 (76.84%) study participants was found to indicate cognitive impairment, and in 309 (76.86%) individuals, the performance on CDT was abnormal. Only 82 (26.28%) of them had received the diagnosis of a mental or neurological disorder or had been on medication because of such a disorder prior to this cognitive assessment. Depressive symptoms were detected in 236 (58.27%) study participants. In 129 (29.4%), 54 (12.3%), and 35 (7.9%) mild, moderate, and severe depressive symptoms were detected, respectively. A diagnosis of depression had been established, and respective pharmacotherapy had been initiated prior to study enrolment in 18 (4%) study participants who screened positive for the presence of depressive symptoms. In 179 (44%) of individuals, both cognitive deficits and depressive symptoms were detected.

3.3. Seeking Further Neuropsychiatric Diagnostic Workup

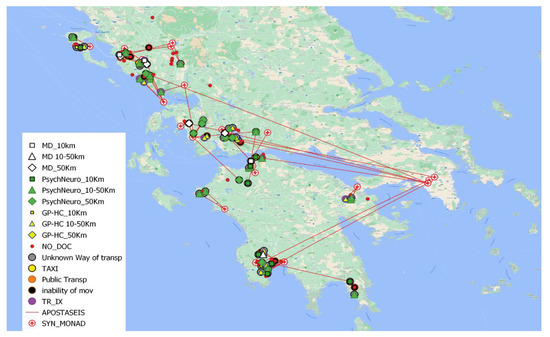

Among the total of 406 municipal home care service users who were screened for the presence of cognitive decline and/or depressive symptoms, 348 individuals opted to receive recommendations for further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup. They were asked to consult a physician of their choice based on the recommendation they received for a further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup. We successfully retrieved the choices made by 334 of these individuals with the support of the staff of the municipal home care services operating in the place of residence of the respective service users. Quite unexpectedly, only just over a third of them, 123 individuals, consulted physicians. The mean distance between their place of residence and the physician they consulted was 79 km. They spent 40 min on average to reach the physician of their choice. Interestingly, only 79 (64.23%) of these individuals chose to consult neurologists or psychiatrists. Figure 1 presents the mobility patterns of municipal home care service users using advanced GIS techniques. Each beneficiary is shown as a unique dot, with red crosses marking the physicians they consulted and red lines tracing the routes taken. Red circles indicate individuals who did not seek care, while those who did are differentiated by the type of provider visited: yellow points for general practitioners or health centers; white for unspecified medical professionals; and green for neurologists, psychiatrists, or hospitals. Travel distance is denoted by shape: squares (<10 km), triangles (10–50 km), and rhombuses (>50 km). Transportation modes are color-coded: gray (unknown), purple (private car), orange (public transport), and yellow (taxi); inability of transportation is denoted with black.

Figure 1.

Mobility patterns of municipal home care service users seeking neuropsychiatric care. The data obtained were visualized in thematic maps using advanced Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques (qGIS). The interactive map can be found in the following link: https://elizageo8.github.io/geocode/ (access date 30 May 2025).

Reluctance to detailed neuropsychiatric workup derived from variable factors. The foremost one was the lack of insight regarding the necessity of seeking medical advice because of screening positive for cognitive deficits and/or depressive symptoms. This was mentioned by 47.6% of study participants who did not consult a physician. Concerns pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis also emerged as a common factor (20%) preventing home care service users from seeking neuropsychiatric care. Health-related issues affecting mobility (7%), financial constraints (7%), and unavailability of a care partner (4.7%) were also mentioned as factors deterring further diagnostic workup.

The correlation analyses unveiled low degrees of correlation between consulting a physician for further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup or not and a few demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic factors, if any. The correlation analyses results are summarized in Table 2. Only previously diagnosed depression and/or dementia or other neurological and/or mental disorders were found to positively correlate with the decision to consult a neurologist, psychiatrist, or general physician after screening positive for the presence or dementia and/or depression diagnosed prior to enrollment in the study. The degrees of correlation were, however, rather low (0.34 and 0.32, respectively).

Table 2.

Degrees of correlation between consulting a physician for further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup or not and demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic factors.

The heat map in Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of municipal home care service users and their mobility patterns in seeking general practitioners, psychiatrists, or neurologists after screening positive for depressive symptoms and/or cognitive deficits. Darker regions indicate stronger associations between factors such as income per capita, population density, and neurological history, while lighter regions represent weaker correlations.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of factors influencing psychogeriatric service utilization which was generated using Python (v3.10), employing the seaborn and matplotlib libraries. Spearman’s rank-order correlation was applied to quantify associations; heatmaps were used to visualize the strength and direction of these relationships.

4. Discussion

4.1. Frequency and Co-Existence of Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Impairment in Users of Municipal Home Care Services

Our research delves into the prevalence of depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment among older users of municipal home care services, a population particularly vulnerable due to disability, chronic disorders, loneliness, lack of family, or professional care. Compared to the prevalences of depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in older individuals in Greece (19.5% and 18.1%, respectively), which have been recently reported that such symptoms were detected in significantly more users of home care services, and particularly in 58.3% and 76.8% of study participants. Notably, the prevalence of moderate to severe depressive symptoms had been found to be lower in the general population of older adults compared to that in home care service users (6.4% vs. 20.2%). In line with our observations, a study focusing on low-income, homebound, middle-aged and older adults underlined the common occurrence of depression within this population [28].The higher frequency of depressive symptoms in users of home care services can pertain to the high number of their physical comorbidities, since they suffered from 3.71 somatic diseases on average, while the prevalence of at least two co-existing diseases in the 60–74 age group of the general population does not exceed 50% [29] and there is a significant dose–response relationship between the number of medical comorbidities and the prevalence of depression in older adults [30]. In addition, the low education levels, the old age, and experiences of loneliness may also explain the high frequency of depressive symptoms detected in our sample. In particular, the low educational level is a positive predictor of depressive symptoms in older adults, since it is a marker of low cognitive and brain reserve, a risk factor for late-life depressive events [31]. The detected high frequency of cognitive impairment can also be related to the low cognitive and brain reserve of home care service users [32]. Further factors possibly linked to the high frequency of cognitive impairment in our sample are the loneliness and the low physical activity related to the presence of many comorbidities and disability, since physical activity and social connection are important in maintaining and fostering healthy brain aging [33,34,35].

Depressive symptoms were found to co-exist with cognitive deficits in almost half of the home care service users that participated in the study. The relationship between depression and dementia is complex and has not been fully disentangled yet. Depressive symptoms are thought to be a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, while they can also embody an early sign or prodrome of dementia, since brain degenerative changes precede the onset of cognitive impairment by several years [36]. This complex relationship is possibly explained by the fact that the pathogenesis of depressive symptoms in aging is interlinked with core aspects of the pathomechanism of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [36].

4.2. Underdiagnosis of Depression and Cognitive Decline in Users of Municipal Home Care Services

Only 4% of home care service users who screened positive for depressive symptoms had been diagnosed with depression and only approximately 26% of those with abnormal performance on MMSE and/or CDT had received the diagnosis of a mental or neurological disorder or had been on medication because of such a disorder prior screening for cognitive deficits. These observations highlight the underdiagnosis of depression and cognitive decline in vulnerable people who live in rural and semi-urban areas of south-western Greece, a part of the country which includes two regions having a share of people at risk of poverty above 25% [37]. These findings align with existing research, which has consistently highlighted the challenges in recognizing and treating depression and cognitive decline among older individuals in low-resource settings [11,38,39,40] These difficulties are often attributed to the shortage of healthcare professionals trained to assess and address mental and cognitive health issues, and to the persistent stigma surrounding mental and neurocognitive disorders [11,41], as well as to misconceptions regarding the nature of cognitive decline and depressive symptoms in older people, which are erroneously understood as aspects of healthy aging [42,43]. Thus, there is an urgent need for addressing mental and cognitive health concerns, particularly depression and cognitive impairment, in vulnerable people residing in low-resource settings, while advocating for increased access to mental and cognitive health services and the destigmatization of these conditions.

4.3. Factors Influencing the Decision on Seeking Further Neuropsychiatric Diagnostic Workup

Home care service users were reluctant to consult a physician for an in-depth neuropsychiatric workup. Quite unexpectedly, only 36.8% of those who would have benefited from such a consultation chose to visit a physician. Almost half of those who did not consult a physician lacked insight into the condition that led to the recommendation for further diagnostic assessment. In such cases, reluctance to acknowledge one’s condition may stem from fears of stigmatization and low levels of psychological openness, which are particularly prevalent in low-resource communities [12,44]. In consonance with such an interpretation, only 64.23% of the individuals who sought further diagnostic assessment chose to consult neurologists or psychiatrists. In addition, the detected reluctance may reflect the aforementioned misconceptions of depressive symptoms and/or cognitive deficits as normal phenomena of aging. Furthermore, concerns related to the COVID-19 crisis were also mentioned by almost one out of five study participants who chose not to consult a physician. Indeed, during the recent pandemic crisis a reduction in the use of health services was observed [45]. Thus, this finding is not unexpected. Mobility difficulties, financial constraints, and the unavailability of a care partner were mentioned by less than 10% of home care service users each as a factor preventing them from seeking further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup. Since the place of residence of those who followed our recommendation was 79 km and 40 min on average far away from the physician they consulted, the aforementioned arguments can be easily justified.

Quite unexpectedly, ARI(gr), the accessibility/remoteness indicator employed in our study, was not found to pertain to the decision of municipal home care services, who screened positive for depressive symptoms and/or cognitive deficits, to consult physicians for further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup. Even though distance and travel time are important determinants of access to healthcare services, mobility for seeking healthcare is affected by further factors such as the mode of transport used, the socio-economic composition of the population studied, quality of the roads, availability of public transport, transportation costs, the individual patient’s perception of travel distance, healthcare facility size, services offered, cost, and the perception of quality and safety [46]. Interestingly, individuals residing in rural areas are used to traveling long distances for services, and subsequently, the distance or time needed to access healthcare seems to be less significant for them [46]. Considering that our study focused on a particularly vulnerable population with disability, chronic disorders, and lack of family or social support, it becomes obvious why the impact of accessibility/remoteness was not found to be significant in our sample.

5. Limitations

Several limitations are pertinent to our research. First, the sample size of assessed users was relatively small, which could impact the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the proportion of municipal home care service users included in our study was low, potentially limiting the broader applicability of our results. Geographically, there was an imbalance in the distribution of participants, which may have influenced the spatial patterns observed in mobility for seeking in further neuropsychiatric diagnostic workup. Moreover, despite our study’s flexibility during the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis itself could have introduced unforeseen factors that influenced our results. Moreover, the detection of depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits exclusively relied on neuropsychological instruments, which, despite their high validity, cannot replace clinical diagnoses [47]. These limitations collectively underscore the need for caution when interpreting and applying our findings.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Depressive symptoms and/or cognitive deficits are present in more than 50% of vulnerable older adults with several comorbidities residing in rural and semi-urban regions in Greece. Nonetheless, they remain undiagnosed in most cases. Even though the needs for cognitive and mental healthcare in aging are pressing, the utilization of services devoted to older people with cognitive deficits and/or depressive symptoms remains low [48]. As a consequence, older adults need to travel long distances in order to consult professionals adequately trained in old-age cognitive and mental health.

The collection of real-world data on mobility patterns of vulnerable older people residing in low-resource settings who seek cognitive and mental healthcare and how these patterns are affected by the implementation of modern, cutting-edge services like e-health psychogeriatric programs in primary healthcare [11,49] may inform the design of services that are tailored to the needs of people who are currently, in fact, left behind. It can contribute to the development of pragmatic, integrated, adaptive, collaborative services which bridge public health, community healthcare services, and secondary or even tertiary cognitive and mental healthcare and social care based on modern digital technology [49,50,51] are centered to each specific spatiotemporal context [52] and meet the needs of individual beneficiaries. Such services provide goal-oriented care, are cost-effective and sustainable, and promote brain health equity in aging and increasingly diverse communities [53,54].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and P.A.; Methodology, E.-Z.G., V.T., M.S., G.P., G.M., D.K., A.V., K.T. and P.A.; Software, E.-Z.G. and V.T.; Formal analysis, E.-Z.G.; Investigation, E.-Z.G. and K.P.; Data curation, E.-Z.G., S.P., M.B., K.P., G.K., A.T., P.M. and P.T.; Writing—original draft, E.-Z.G., V.T. and P.A.; Writing—review & editing, S.P., M.S. and K.T.; Visualization, E.-Z.G., V.T. and P.A.; Supervision, P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Patras General University Hospital Bioethics Committee (256/13.09.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Members of the Geo-CoDe Study Group, Mariana Andreadi, Antigoni Anastasiadou, Astrinia Adamopoulou, Theodora Barla, Vasiliki Basiladioti, Sofia Belegri, Panagiota Banou, Theodora Boutsi, Marina Gaki, Giolanta Georgiou, Ioanna Gerafenti, Evanthia Giannopoulou, Theodora Giannopoulou, Marineta Ferentinou, Evangelia Palaiochoriti, Maria Kantareli, Katerina Kapnia, Panagiota Karakani, Nikoleta Kitsou, Eleni Kokkali, Christina Koukiali, Stavroula Konstantinou, Eleni Koubouli, Nikoleta Lampro u, Panagiota Lazou, Marina Ilia, Konstantina Moutzouri, Christina Nikopoulou, Paraskevi Tsaveli, Sofia Panagiotea, Theodora Barla, Christina Sambazioti, Konstantina Stathi, Maria Tzoumerkioti, Vasiliki Varfi, Ourania Vangeli, Paraskevi Vlachou contributed to the collection of clinical and demographic data, applied the screening tools and explained to service users the findings of the screening procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Overend, K.; Bosanquet, K.; Bailey, D.; Foster, D.; Gascoyne, S.; Lewis, H.; Nutbrown, S.; Woodhouse, R.; Gilbody, S.; Chew-Graham, C. Revealing hidden depression in older people: A qualitative study within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Family Practice 2015, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotopoulos, G.; Kaliampakos, D. Accessibility and Spatial Inequalities in Greece. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2019, 12, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; White, E.M.; Mills, C.; Thomas, K.S.; Jutkowitz, E. Rural-urban differences in diagnostic incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Demnitz, N.; Yamamoto, S.; Yaffe, K.; Lawlor, B.; Leroi, I. Defining brain health: A concept analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37, gps.5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, H.A.; Stirland, L.E.; Jeste, D.V.; Reynolds, C.F.; Berk, M.; Ibanez, A.; Dawson, W.D.; Lawlor, B.; Leroi, I.; Yaffe, K.; et al. Life-Course Brain Health as a Determinant of Late-Life Mental Health: American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry Expert Panel Recommendations. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 31, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenebe, Y.; Akele, B.; Selassie, M.; Necho, M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denslow, S.; Wingert, J.R.; Hanchate, A.D.; Rote, A.; Westreich, D.; Sexton, L.; Cheng, K.; Curtis, J.; Jones, W.S.; Lanou, A.J.; et al. Rural-urban outcome differences associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations in North Carolina. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Mandal, B.; Muhammad, T.; Ali, W. Decomposing the rural–urban differences in depression among multimorbid older patients in India: Evidence from a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H.; Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy as a function of remoteness of residence: An Australian national study. BMC Public Health 2019, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chauhan, S.; Patel, R.; Kumar, M.; Simon, D.J. Urban-rural and gender differential in depressive symptoms among elderly in India. Dialogues Health 2023, 2, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, A.; Vorvolakos, T.; Kontogianni, E.; Alexaki, M.; Georgiou, E.-Z.; Aggeletaki, E.; Gkampra, M.; Delatola, M.; Delatolas, A.; Efkarpidis, A.; et al. Old-age mental telehealth services at primary healthcare centers in low- resource areas in Greece: Design, iterative development and single-site pilot study findings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, H.; Jameson, J.P.; Curtin, L. The relationship between stigma and self-reported willingness to use mental health services among rural and urban older adults. Psychol. Serv. 2015, 12, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucciardini, R.; Zetterquist, P.; Rotko, T.; Putatti, V.; Mattioli, B.; De Castro, P.; Napolitani, F.; Giammarioli, A.M.; Kumar, B.N.; Nordström, C.; et al. Addressing health inequalities in Europe: Key messages from the Joint Action Health Equity Europe (JAHEE). Arch. Public Health 2023, 81, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotopoulos, G.; Kaliampakos, D. Location quotient-based travel costs for determining accessibility changes. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Tsolaki, M.; Iacovides, A.; Yesavage, J.; O’Hara, R.; Kazis, A.; Ierodiakonou, C. The validation of the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1999, 11, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Bird, V.; Rizzo, M.; Meader, N. Diagnostic validity and added value of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression in primary care: A meta-analysis of GDS30 and GDS15. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 125, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.T.; Seward, K.; Patterson, A.; Melton, A.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Evaluation of Available Cognitive Tools Used to Measure Mild Cognitive Decline: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvitting, A.S.; Fällman, K.; Wressle, E.; Marcusson, J. Age-Normative MMSE Data for Older Persons Aged 85 to 93 in a Longitudinal Swedish Cohort. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, F.; Costaggiu, D.; Mandas, A. Mini-Mental State Examination: Optimal Cut-Off Levels for Mild and Severe Cognitive Impairment. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprahamian, I.; Martinelli, J.E.; Neri, A.L.; Yassuda, M.S. The Clock Drawing Test: A review of its accuracy in screening for dementia. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2009, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Jahng, S.; Yu, K.-H.; Lee, B.-C.; Kang, Y. Usefulness of the Clock Drawing Test as a Cognitive Screening Instrument for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Dementia: An Evaluation Using Three Scoring Systems. Dement. Neurocognitive Disord. 2018, 17, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çorbacıoğlu, Ş.K.; Aksel, G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.-T. Introduction to Geographic Information Systems, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, T.O.; DeCicco, L.A.; Hariharan, J.A.; Stanish, L.F.; Black, S.; Horsburgh, J.S. Reproducibility Starts at the Source: R, Python, and Julia Packages for Retrieving USGS Hydrologic Data. Water 2023, 15, 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauke, J.; Kossowski, T. Comparison of Values of Pearson’s and Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients on the Same Sets of Data. QUAGEO 2011, 30, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Grela, E.; McKelway, M.; Schilbach, F.; Sharma, G.; Vaidyanathan, G. Depression and Loneliness Among the Elderly Poor; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelopoulou, E.; Alimani, G.; Apotsos, P.; Simou, G.; Kiritsi, E.; Mathioudakis, A.G.; Mathioudakis, G.A. An epidemiological study of multimorbidity in Greece. Arch. Hell. Med. 2019, 36, 754. [Google Scholar]

- Agustini, B.; Lotfaliany, M.; Woods, R.L.; McNeil, J.J.; Nelson, M.R.; Shah, R.C.; Murray, A.M.; Ernst, M.E.; Reid, C.M.; Tonkin, A.; et al. Patterns of Association between Depressive Symptoms and Chronic Medical Morbidities in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlmans, J.L.; Vernooij, M.W.; Ikram, M.A.; Luik, A.I. The role of cognitive and brain reserve in late-life depressive events: The Rotterdam Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 320, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, L.D.; Clare, L.; Opdebeeck, C.; Martyr, A.; Jones, R.W.; Rusted, J.M.; Pentecost, C.; Thom, J.M.; Matthews, F.E. Cognitive reserve and its impact on cognitive and functional abilities, physical activity and quality of life following a diagnosis of dementia: Longitudinal findings from the Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life (IDEAL) study. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afae284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, P.; Leroi, I.; Kinchin, I.; Canty, A.J.; Dasgupta, J.; Furlano, J.A.; Haas, A.N. Relevance and Premises of Values-Based Practice for Decision Making in Brain Health. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchetti, M.; Aschwanden, D.; Sesker, A.A.; Zhu, X.; O’Súilleabháin, P.S.; Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A.; Sutin, A.R. A meta-analysis of loneliness and risk of dementia using longitudinal data from >600,000 individuals. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raichlen, D.A.; Aslan, D.H.; Sayre, M.K.; Bharadwaj, P.K.; Ally, M.; Maltagliati, S.; Lai, M.H.C.; Wilcox, R.R.; Klimentidis, Y.C.; Alexander, G.E. Sedentary Behavior and Incident Dementia Among Older Adults. JAMA 2023, 330, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafsari, F.S.; Jessen, F. Depression—An underrecognized target for prevention of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, E. Eurostat Database. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 2255–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, M.J.R.; Suemoto, C.K. Empowering older adults and their communities to cope with depression in resource-limited settings. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e643–e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Samu, G.C.; Chen, J. Advancing mental health service delivery in low-resource settings. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e543–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Hou, F.; Han, X.; Hu, S.; Shen, G.; Zhang, Y. Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Decline Among Chinese Rural Elderly Individuals: A Longitudinal Study With 2-Year Follow-Up. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 939150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocker, E.; Glasser, M.; Nielsen, K.; Weidenbacher-Hoper, V. Rural older adults’ mental health: Status and challenges in care delivery. Rural. Remote Health 2012, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devita, M.; De Salvo, R.; Ravelli, A.; De Rui, M.; Coin, A.; Sergi, G.; Mapelli, D. Recognizing Depression in the Elderly: Practical Guidance and Challenges for Clinical Management. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 2867–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, D.; Fiordelli, M.; Fadda, M.; Serena, S.; Piumatti, G.; Carlevaro, F.; Magno, F.; Franscella, G.; Albanese, E. Dementia is (not) a natural part of ageing: A cross-sectional study on dementia knowledge and misconceptions in Swiss and Italian young adults, adults, and older adults. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHP 2 Depression Group; Shajan, A.M.; Guttikonda, A.; Hephzibah, A.; Jones, A.S.; Susanna, J.; Neethu, S.; Poornima, S.; Jala, S.M.; Arputharaj, D.; et al. Perceived Stigma Regarding Mental Illnesses among Rural Adults in Vellore, Tamil Nadu, South India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2019, 41, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujolar, G.; Oliver-Anglès, A.; Vargas, I.; Vázquez, M.L. Changes in Access to Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mseke, E.P.; Jessup, B.; Barnett, T. Impact of distance and/or travel time on healthcare service access in rural and remote areas: A scoping review. J. Transp. Health 2024, 37, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Qiu, L.; Levis, B.; Fan, S.; Sun, Y.; Amiri, L.S.N.; Harel, D.; Markham, S.; Vigod, S.N.; Ziegelstein, R.C.; et al. Depression prevalence of the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 was compared to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM using individual participant data meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 17430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexopoulos, P.; Novotni, A.; Novotni, G.; Vorvolakos, T.; Vratsista, A.; Konsta, A.; Kaprinis, S.; Konstantinou, A.; Bonotis, K.; Katirtzoglou, E.; et al. Old age mental health services in Southern Balkans: Features, geospatial distribution, current needs, and future perspectives. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggeletaki, E.; Stamos, V.; Konidari, E.; Efkarpidis, A.; Petrou, A.; Savvopoulou, K.; Kontogianni, E.; Tsimpanis, K.; Vorvolakos, T.; Politis, A.; et al. Telehealth memory clinics in primary healthcare: Real-world experiences from low-resource settings in Greece. Front. Dement. 2024, 3, 1477242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allana, A.; Kuluski, K.; Tavares, W.; Pinto, A.D. Building integrated, adaptive and responsive healthcare systems—Lessons from paramedicine in Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamer, B.; Drewes, H.; Putters, K.; Van Oers, H.; Baan, C. Reorganizing and integrating public health, health care, social care and wider public services: A theory-based framework for collaborative adaptive health networks to achieve the triple aim. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2020, 25, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiam, Y.; Allaire, J.-F.; Morin, P.; Hyppolite, S.-R.; Doré, C.; Zomahoun, H.T.V.; Garon, S. A Conceptual Framework for Integrated Community Care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkind, M.S.V.; Albert, M.A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M. Road to Equity in Brain Health. Circulation 2022, 145, e869–e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele Gray, C.; Grudniewicz, A.; Armas, A.; Mold, J.; Im, J.; Boeckxstaens, P. Goal-Oriented Care: A Catalyst for Person-Centred System Integration. Int. J. Integr. Care 2020, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).