Challenges and Implications of Virtual Reality in History Education: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. VR in Education

1.2. Rationale

1.3. Research Questions and Purpose

- RQ1

- What are the most prevalent technical, usability, and economic challenges faced by educators when integrating VR into history instruction?

- RQ2

- What psychological, social, and ethical issues emerge from the use of these technologies in history education?

- RQ3

- Do history educators require specialized training to effectively use VR technologies?

2. Methods

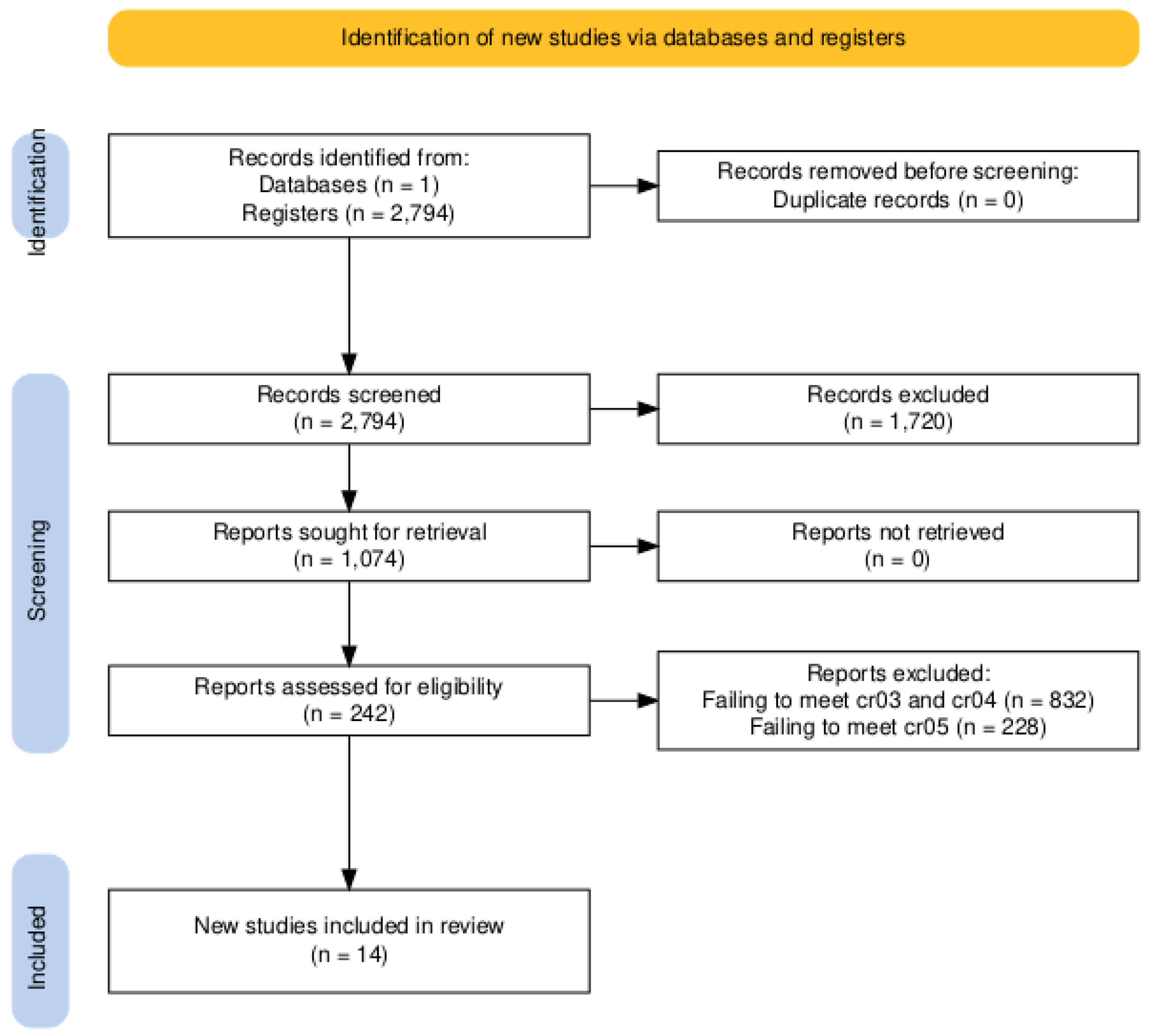

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- They were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. To ensure the reliability and quality of the research, conference papers, book chapters, and other non-journal publications were excluded, as they do not necessarily undergo rigorous peer review process (cr01).

- The full texts were accessible online or through university library systems. If there was any doubt regarding a study, the full article was reviewed before making a final decision on its inclusion or exclusion (cr02).

- They employed VR (cr03).

- They were research studies within the field of history education (cr04).

- The studies addressed or mentioned challenges, limitations, difficulties, deficiencies, drawbacks, or similar concepts regarding the use of VR (cr05).

2.2. Information Source and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process and Data Collection

2.4. Data Items and Synthesis Methods

- Ethical considerations: Issues related to privacy, informed consent, and the responsible use of VR in educational contexts.

- Psychological and social impact: Effects of VR on students’ perception, motivation, and social interaction in learning history.

- Usability challenges (difficulty of use): Technical or cognitive barriers that hinder effective use of VR by teachers and students.

- Pedagogical aspects: Teaching strategies and methodological approaches that enhance the use of VR for history education.

- Technical issues (motion and visualization): Technical problems such as latency, graphics quality, or motion sickness that affect the user experience.

- Economic aspects (development and production costs): Costs associated with designing, implementing, and maintaining VR experiences for history education.

- Social and cultural acceptance: Students’ and teachers’ perception and willingness to integrate VR into history learning.

- Social interaction in virtual environments: Communication and collaboration dynamics among users in history learning experiences within virtual environments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Technical Issues

3.2. Usability Challenges

3.3. Psychological and Social Impact

3.4. Economic Aspect

3.5. Pedagogical Aspects

3.6. Rest of Categories

4. Conclusions

Study Implications and Educational Practices

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liceras, A. Tratamiento de las Dificultades de Aprendizaje en Ciencias Sociales; Grupo Editorial Universitario: Granda, España, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, C.J.G.; Martínez, P.M.; Medina, J.R.; Sánchez, J.J.M. Perceptions on the procedures and techniques for assessing history and defining teaching profiles. Teacher training in Spain and the United Kingdom. Educ. Stud. 2021, 47, 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanSledright, B.A. The Challenge of Rethinking History Education. On practice, Theories, and Policy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, P.; Gómez, C.J.; Arias, L. Social sciences teaching and information processing. An experience using WebQuests in primary education teacher training. RUSC Univ. Knowl. Soc. J. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miralles, P.; Gómez, C.J.; Monteagudo, J. Percepciones sobre el uso de recursos TIC y «MASS-MEDIA» Para la enseñanza de la historia. Un estudio comparativo en futuros docentes de España-Inglaterra. Educ. XX1 2019, 22, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez-Etxeberria, A.; Gómez-Carrasco, C.J.; Fontal, O.; García-Ceballos, S. Virtual environments and augmented reality applied to heritage education. An evaluative study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Rodríguez, F.; Merchán, M.J.; Merchán, P.; Pérez, E. Comparative Analysis between Virtual Visits and Pedagogical Outings to Heritage Sites: An Application in the Teaching of History. Heritage 2024, 7, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.C.; Chen, C.C.; Chou, Y.W. Animating eco-education: To see, feel, and discover in an augmented reality-based experiential learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2016, 96, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.; Adams Becker, S.; Cummins, M.; Davis, A.; Hall Giesinger, C. NMC/CoSN Horizon Report: 2017 K-12 Edition; Technical Report; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.; Becker, S.A.; Cummins, M.; Estrada, V.; Freeman, A.; Hall, C. NMC Horizon Report: 2016 Higher Education Edition; Technical Report; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tecnológico de Monterrey. Reporte EduTrends. Radar de Innovación Educativa 2015; Technical Report; Tecnológico de Monterrey: Monterrey, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tecnológico de Monterrey. Reporte EduTrends. Realidad Aumentada y Virtual; Technical Report; Tecnológico de Monterrey: Monterrey, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Doerner, R.; Steinicke, F. Perceptual Aspects of VR. In Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Puente, A.P. La Realidad Aumentada: Tecnología emergente para la sociedad del aprendizaje. Aula Rev. Humanidades Cienc. Soc. 2020, 66, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Barroso, J. Los escenarios tecnológicos en Realidad Aumentada (RA): Posibilidades educativas en estudios universitarios. Aula Abierta 2018, 47, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomari, A.G.P. Realidad virtual y realidad aumentada en la educación, una instantánea nacional e internacional. Econ. Creat. 2017, 7, 34–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timotheou, S.; Miliou, O.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Sobrino, S.V.; Giannoutsou, N.; Cachia, R.; Monés, A.M.; Ioannou, A. Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 6695–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldera, B.R. Realidad aumentada en educación primaria: Revisión sistemática. Edutec Rev. ElectróNica Tecnol. Educ. 2021, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pellas, N.; Mystakidis, S.; Kazanidis, I. Immersive Virtual Reality in K-12 and Higher Education: A systematic review of the last decade scientific literature. Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 835–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena Taranilla, R.; Cózar-Gutiérrez, R.; González-Calero, J.A.; López Cirugeda, I. Strolling through a city of the Roman Empire: An analysis of the potential of virtual reality to teach history in Primary Education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022, 30, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez García, G.; Rodríguez Jiménez, C.; Marín Marín, J.A. La trascendencia de la Realidad Aumentada en la motivación estudiantil. Una revisión sistemática y meta-análisis. Alteridad Rev. Educ. 2020, 15, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Natale, A.F.; Repetto, C.; Riva, G.; Villani, D. Immersive virtual reality in K-12 and higher education: A 10-year systematic review of empirical research. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2006–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Z.; Goetz, E.T.; Cifuentes, L.; Keeney-Kennicutt, W.; Davis, T.J. Effectiveness of virtual reality-based instruction on students’ learning outcomes in K-12 and higher education: A meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2014, 70, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Rodríguez, A. Reinventando la enseñanza de la Historia Moderna en Secundaria: La utilización de ChatGPT para potenciar el aprendizaje y la innovación docente. Estud. HistóRico Hist. Mod. 2023, 45, 101–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenor, J.; Ma, M. Augmented Reality in Holocaust museums and memorials. In Springer Handbook of Augmented Reality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O.; Ibañez-Etxeberria, A. Research on heritage education. Evolution and current state through analysis of high impact indicators. Rev. Educ. 2017, 375, 184–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Gorospe, J.M.; Ibáñez Etxeberria, A. Museos, tecnología e innovación educativa: Aprendizaje de patrimonio y arqueología en territorio menosca. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calidad Efic. Cambio Educ. 2005, 3, 880–894. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, R. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1997, 6, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basogain, X.; Olabe, M.; Espinosa, K.; Rouèche, C.; Olabe, J.C. Realidad Aumentada en la Educación: Una Tecnología Emergente; Escuela Superior de Ingeniería de Bilbao, EHU: Bilbao, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, H. Building a virtual Roman city: Teaching history through video game design. J. Class. Teach. 2023, 24, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, M.C.; Dede, C.; Loftin, R.B.; Chen, J. A model for understanding How virtual Reality Aids complex Conceptual learning. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1999, 8, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Taranilla, R.; Cózar-Gutiérrez, R.; González-Calero, J.A.; Diago, P.D. An extended technology acceptance model on immersive virtual reality use with primary school students. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2023, 32, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, J.D. Patrimonio universitario, patrimonio virtual. Educ. Futur. Rev. Investig. Apl. Exp. Educ. 2012, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sacristán, A.; Waelder, P. Realidad Virtual + Internet 3D. 2016. Available online: https://www.artfutura.org/v3/realidad-virtual-internet-3d/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Fernández Robles, B. Las tecnologías digitales emergentes entran en la Universidad: RA y RV. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2018, 21, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, O.R.; Suelves, D.M.; Gómez, S.L.; Rodríguez, J.R. Digital Resources for Teaching and Learning History. A Research Review. Panta Rei Rev. Digit. Hist. DidáCtica Hist. 2024, 18, 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Taranilla, R.; Diago, P.D.; Colomer Rubio, J.C. Virtual Reality as a Pedagogical Tool: Motivation and Perception in Teacher Training for Social Sciences and History in Primary Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, A.; Styliou, M.; Ntalas, N.; Stylios, C. The Impact of Immersive Virtual Reality on Knowledge Acquisition and Adolescent Perceptions in Cultural Education. Information 2024, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Majid, F.; Mohd Shamsudin, N. Identifying Factors Affecting Acceptance of Virtual Reality in Classrooms Based on Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2019, 15, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydn, T. Supporting beginning teachers’ use of ICT in the history classroom. In Mentoring History Teachers in the Secondary School; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M.; Bedenlier, S.; Bond, M.; Buntins, K. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J. Learning historical and chronological time: Practical applications. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 2016, 12, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett, J. New technologies, new formalisms for historians: The 3D virtual buildings. Lit. Linguist. Comput. 2004, 19, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, M. Storia, oggetti, web. Collezioni e strumenti digitali per la digital public history. Um. Digit. 2023, 16, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, J.; Haahr, M. What Really Happened Here? Dealing with Uncertainty in the Book of Distance: A Critical Historiography Perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, Kobe, Japan, 11–15 November 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Parong, J.; Mayer, R.E. Learning about history in immersive virtual reality: Does immersion facilitate learning? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 1433–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puggioni, M.; Frontoni, E.; Paolanti, M.; Pierdicca, R. ScoolAR: An educational platform to improve students’ learning through virtual reality. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 21059–21070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D. Advanced Technology of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and Korean Ancient History—Study on the use of artificial intelligence to decipher Wooden Tablets and the restoration of ancient historical remains using virtual reality and augmented reality. Int. J. Korean Hist. 2019, 24, 13–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, E. Virtual Wolverhampton: Recreating the historic city in virtual reality. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2017, 11, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, J.M.; Poitras, E.G.; Jarrell, A.; Duffy, M.C.; Lajoie, S.P. Comparing virtual and location-based augmented reality mobile learning: Emotions and learning outcomes. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J. History educators and the challenge of immersive pasts: A critical review of virtual reality ‘tools’ and history pedagogy. Learn. Media Technol. 2008, 33, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.J. Cultural heritage, archives & citizenship: Reflections on using Virtual Reality for presenting knowledge diversity in the public sphere. Crit. Arts J. South-North Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 308–320. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Carrasco, C.; Rodríguez-Medina, J.; Chaparro, A.; Alonso, S. Recursos digitales y enfoques de enseñanza en la formación inicial del profesorado de Historia. Educ. XX1 2022, 25, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumoumen, K.; Aboubane, F.; Younes, E.C.H. Automation of Historical Buildings: Historical Building Information Modeling (HBIM) based Virtual Reality (VR). In Mediterranean Architectural Heritage: RIPAM10; Materials Research Forum: Millersville, PA, USA, 2024; Volume 40, p. 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Implied Categories |

|---|---|

| Gómez-Galán (2016) [43] | Ethical considerations |

| Psychological and social impact | |

| Bonnett (2004) [44] | Usability challenges |

| Pedagogical aspects | |

| Christopoulos et al. (2024) [38] | Technical issues |

| Usability challenges | |

| Pedagogical aspects | |

| Caron (2023) [45] | Technical issues |

| Economic aspects | |

| Corrales et al. (2024) [7] | Psychological and social impact |

| Social and cultural acceptance | |

| Forsyth (2024) [30] | Technical issues |

| Bárbara and Haahr (2023) [46] | Usability challenges |

| Parong and Mayer (2021) [47] | Psychological and social impact |

| Puggioni et al. (2021) [48] | Pedagogical aspects |

| Pedagogical aspects | |

| Lim D. (2019) [49] | Social interaction in virtual environments |

| Pedagogical aspects | |

| Ramsey (2017) [50] | Technical issues |

| Harley et al. (2016) [51] | Technical issues |

| Allison (2008) [52] | Psychological and social impact |

| Pedagogical aspects | |

| Green (2007) [53] | Economic aspects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villena-Taranilla, R.; Diago, P.D. Challenges and Implications of Virtual Reality in History Education: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5589. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105589

Villena-Taranilla R, Diago PD. Challenges and Implications of Virtual Reality in History Education: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(10):5589. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105589

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillena-Taranilla, Rafael, and Pascual D. Diago. 2025. "Challenges and Implications of Virtual Reality in History Education: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 10: 5589. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105589

APA StyleVillena-Taranilla, R., & Diago, P. D. (2025). Challenges and Implications of Virtual Reality in History Education: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 15(10), 5589. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105589