Games with a Purpose for Part-of-Speech Tagging and the Impact of the Applied Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment and Games with a Purpose Preference

Abstract

1. Introduction

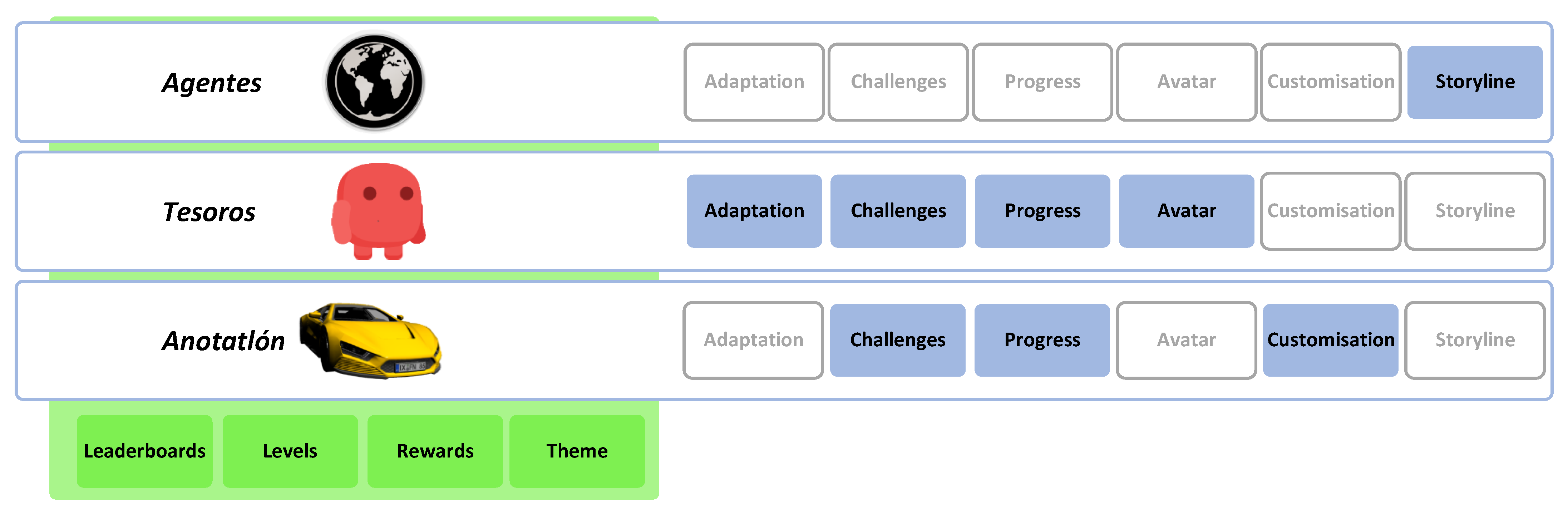

- RQ1: Do the implemented GDEs influence players’ enjoyment and, consequently, their preference for games? Based on the type and number of implemented GDEs (see Figure 1), the order of preference is hypothesized as follows: (1) Tesoros, (2) Anotatlón, and (3) Agentes.

- RQ2: Are certain GDEs associated with higher values of player enjoyment?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. GWAPs and the Implemented GDEs

2.3. Measurement

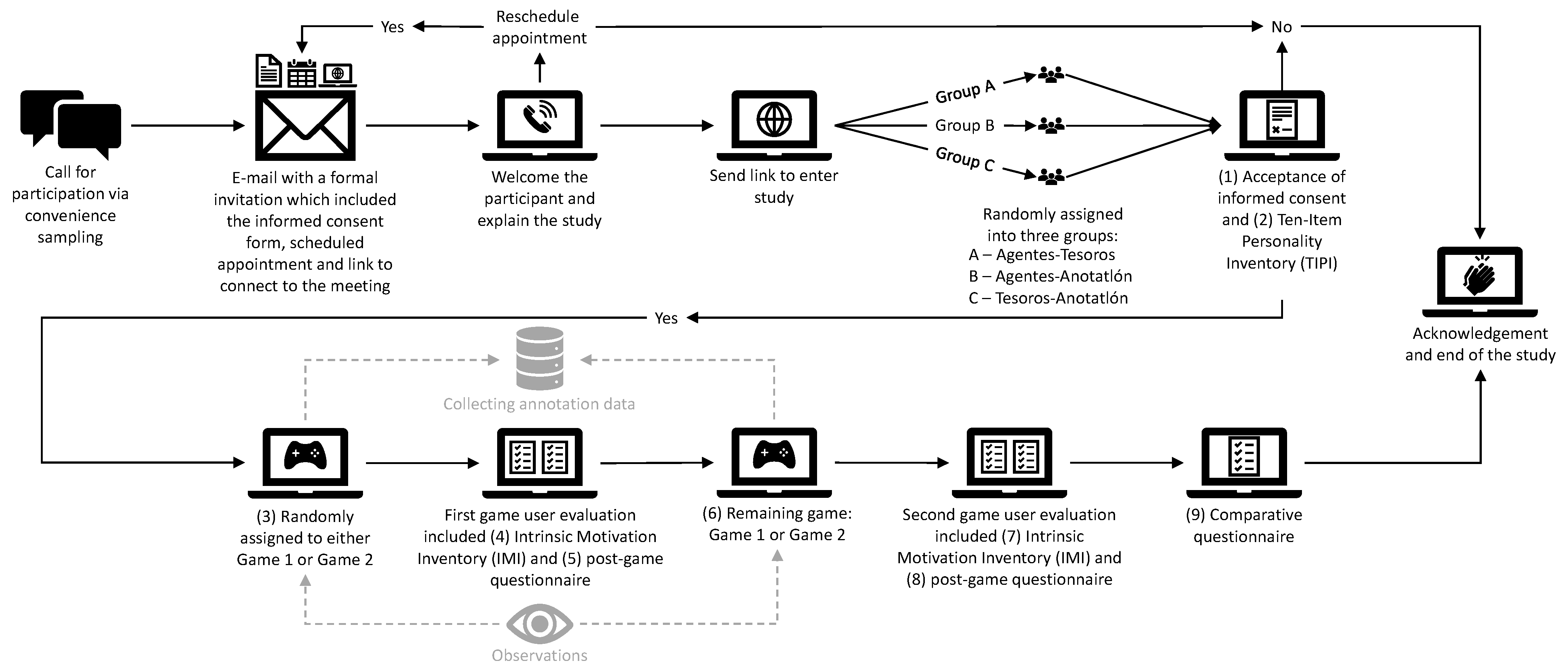

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Game Concept Preference

3.2. Game Design Elements

3.2.1. Implementation

3.2.2. Preference/Favorite

4. Discussion

4.1. Game Concept Preference

4.2. Game Design Elements

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chamberlain, J.; Fort, K.; Kruschwitz, U.; Lafourcade, M.; Poesio, M. Using Games to Create Language Resources: Successes and Limitations of the Approach. In The People’s Web Meets NLP: Collaboratively Constructed Language Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSER = Inés Fernández-Ordóñez (dir.) (2005-): Corpus Oral y Sonoro del Español Rural. Available online: http://www.corpusrural.es (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Chambers, J.K.; Trudgill, P. Dialectology; Cambridge University Press: Cham, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Caroux, L.; Isbister, K.; Le Bigot, L.; Vibert, N. Player-video game interaction: A systematic review of current concepts. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Ahn, L.; Kedia, M.; Blum, M. Verbosity: A Game for Collecting Common-Sense Facts. In CHI’06: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, B.; Fort, K.; Lefebvre, N. Crowdsourcing Complex Language Resources: Playing to Annotate Dependency Syntax. In Proceedings of the COLING 2016—26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Osaka, Japan, 11–16 December 2016; Proceedings of COLING 2016: Technical Papers. pp. 3041–3052. [Google Scholar]

- Madge, C.; Bartle, R.; Chamberlain, J.; Kruschwitz, U.; Poesio, M. Incremental Game Mechanics Applied to Text Annotation. In CHI PLAY’19: Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Barcelona, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poesio, M.; Chamberlain, J.; Kruschwitz, U.; Robaldo, L.; Ducceschi, L. Phrase detectives: Utilizing collective intelligence for internet-scale language resource creation. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. 2013, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madge, C.; Yu, J.; Chamberlain, J.; Kruschwitz, U.; Paun, S.; Poesio, M. Crowdsourcing and aggregating nested markable annotations. In Proceedings of the ACL 2019—57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Proceedings of the Conference, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venhuizen, N.J.; Basile, V.; Evang, K.; Bos, J.; Basile, V.; Bos, J.; Venhuizen, N.J. Gamification for Word Sense Labeling. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computational Semantics, IWCS 2013—Long Papers, Potsdam, Germany, 19–22 March 2013; pp. 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness. In MindTrek’11: Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, New York, USA, 2011; p. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ahn, L.; Dabbish, L. Designing games with a purpose. Commun. ACM 2008, 51, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poesio, M.; Chamberlain, J.; Kruschwitz, U. Crowdsourcing. In Handbook of Linguistic Annotation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Bopp, J.A.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies on the Enjoyment of Digital Entertainment Games. In CHI’14: Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, New York, USA, 2014; pp. 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.A.; Connolly, T.M.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. Engagement in digital entertainment games: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnibal, M.; Montani, I.; Van Landeghem, S.; Boyd, A. spaCy: Industrial-Strength Natural Language Processing in Python; Zenodo: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Segundo Díaz, R.L.; Rovelo, G.; Bouzouita, M.; Hoste, V.; Coninx, K. The Influence of Personality Traits and Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment: A Demo on GWAPs for Part-of-Speech Tagging. In Proceedings of the Serious Games. 9th Joint International Conference, JCSG 2023, Dublin, Ireland, 26–27 October 2023; Haahr, M., Rojas-Salazar, A., Göbel, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14309, pp. 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segundo Díaz, R.L.; Bonilla, J.E.; Bouzouita, M.; Ruiz, G.R.; Rovelo Ruiz, G. Juegos con propósito para la anotación del Corpus Oral Sonoro del Español rural. Dialectologia et Geolinguistica 2023, 31, 135–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.D.; Duncan, T.; Tammen, V.V. Psychometric properties of the intrinsic motivation inventoiy in a competitive sport setting: A confirmatory factor analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1989, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segundo Díaz, R.L.; Rovelo Ruiz, G.; Bouzouita, M.; Hoste, V.; Coninx, K. The Influence of Personality Traits and Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment: An Empirical Study on GWAPs for Linguistics. In Proceedings of the Games and Learning Alliance 12th International Conference, GALA 2023, Dublin, Ireland, 29 November–1 December 2023; Dondio, P., Rocha, M., Brennan, A., Schönbohm, A., de Rosa, F., Koskinen, A., Bellotti, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14475, pp. 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuite, K. GWAPs: Games with a Problem. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, FDG 2014, Liberty of the Seas, Caribbean, 3–7 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Xu, B.; Karanam, Y.; Voida, S. Personality, targeted Gamification: A Survey Study on Personality Traits and Motivational Affordances. In CHI’16: Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Klarkowski, M.; Vella, K.; Phillips, C.; McEwan, M.; Watling, C.N. Greater rewards in videogames lead to more presence, enjoyment and effort. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, I.G. Time Pressure as Video Game Design Element and Basic Need Satisfaction. In CHI EA’16: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.; Gama, S.; Melo, F.S. Flow Adaptation in Serious Games for Health. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 6th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), Vienna, Austria, 16–18 May 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildner, P.; Stamer, N.; Effelsberg, W. From Game Characteristics to Effective Learning Games. In Serious Games: Proceedings of the First Joint International Conference, JCSG 2015, Huddersfield, UK, 3–4 June 2015; Göbel, S., Ma, M., Baalsrud Hauge, J., Oliveira, M.F., Wiemeyer, J., Wendel, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birk, M.V.; Atkins, C.; Bowey, J.T.; Mandryk, R.L. Fostering Intrinsic Motivation through Avatar Identification in Digital Games. In CHI’16: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2982–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestopnik, N.R.; Tang, J. Points, stories, worlds, and diegesis: Comparing player experiences in two citizen science games. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Goh, D.H.L.; Lim, E.P.; Vu, A.W.L. Aesthetic experience and acceptance of human computation games. In Digital Libraries: Providing Quality Information: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Asia-Pacific Digital Libraries, ICADL 2015, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 9–12 December 2015; Allen, R.B., Hunter, J., Zeng, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9469, pp. 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.E.; Segundo Díaz, R.L.; Bouzouita, M. Using GWAPs for Verifying PoS Tagging of Spoken Dialectal Spanish. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th International Conference on Behavioural and Social Computing (BESC), Larnaca, Cyprus, 30 October–1 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IMI | Agentes | Tesoros | Anotatlón | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD | |

| Interest/Enjoyment | 4.49 | 1.57 | 5.18 | 1.30 | 5.46 | 1.15 |

| Competence | 5.37 | 1.15 | 5.79 | 0.89 | 5.07 | 1.22 |

| Effort/Importance | 4.08 | 1.36 | 3.74 | 1.26 | 4.21 | 1.30 |

| Tension/Pressure | 2.80 | 0.91 | 2.62 | 0.81 | 2.70 | 1.06 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr(>) | OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −14.8777 | 5.6344 | −2.6400 | 0.0083 | ** | 0.0000 |

| Interest/Enjoyment | 0.9423 | 0.6939 | 1.3580 | 0.1745 | 2.5660 | |

| Competence | 1.3923 | 0.6153 | 2.2630 | 0.0237 | * | 4.0243 |

| Effort/Importance | 0.4474 | 0.5094 | 0.8780 | 0.3799 | 1.5642 | |

| Tension/Pressure | 0.8707 | 0.7750 | 1.1230 | 0.2612 | 2.3886 |

| GDE | Agentes | Tesoros | Anotatlón | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | INT.ENJ | COMP | Mean | SD | INT.ENJ | EFF.IMP | Mean | SD | INT.ENJ | COMP | EFF.IMP | TEN.PRES | |

| Adaptation | 6.97 | 2.34 | 0.50 * | 7.61 | 2.37 | 0.49 ** | 0.39 * | 7.53 | 2.20 | |||||

| Avatar | 2.74 | 2.49 | 6.72 | 2.95 | 0.42 * | 6.05 | 3.55 | |||||||

| Challenges | 7.43 | 2.13 | 0.36 * | 7.31 | 2.24 | 0.57 *** | 0.60 *** | 7.91 | 2.08 | 0.60 *** | 0.49 ** | |||

| Customization | 3.29 | 2.88 | 5.00 | 3.56 | 0.46 * | 8.03 | 2.99 | 0.41 * | −0.39 * | |||||

| Leaderboards | 7.91 | 1.84 | 7.47 | 2.57 | 0.46 ** | 7.75 | 2.41 | 0.37 * | 0.41 * | |||||

| Levels | 7.15 | 2.58 | 0.45 ** | 7.31 | 2.84 | 0.60 *** | 0.38 * | 7.40 | 2.78 | 0.36 * | 0.40 * | |||

| Progress | 5.88 | 3.09 | 7.57 | 2.68 | 6.50 | 3.06 | ||||||||

| Rewards | 6.89 | 2.76 | 8.69 | 1.72 | 0.36 * | 0.38 * | 8.39 | 1.68 | ||||||

| Storyline | 5.58 | 2.88 | 5.11 | 2.59 | 4.53 | 2.84 | ||||||||

| Theme | 6.47 | 2.55 | 0.42 * | 7.69 | 2.10 | 0.56 *** | 7.29 | 2.97 | ||||||

| GDE | Agentes | Tesoros | Anotatlón | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | TEN.PRES | Mean | SD | INT.ENJ | COMP | TEN.PRES | Mean | SD | INT.ENJ | COMP | TEN.PRES | |

| Adaptation | 3.44 | 2.16 | 4.06 | 2.46 | 3.89 | 2.26 | |||||||

| Avatar | 8.05 | 1.99 | 5.69 | 2.88 | −0.37 * | 6.10 | 3.16 | ||||||

| Challenges | 3.40 | 1.82 | 3.28 | 1.88 | 0.35 * | 0.38 * | 3.03 | 2.16 | 0.36 * | ||||

| Customization | 7.10 | 2.30 | 7.45 | 2.54 | 5.83 | 2.76 | |||||||

| Leaderboards | 5.23 | 2.35 | 6.22 | 2.40 | 0.40 * | 5.89 | 2.14 | 0.38 * | 0.35 * | ||||

| Levels | 4.59 | 2.30 | 0.38 * | 4.81 | 2.18 | 4.60 | 1.97 | 0.38 * | |||||

| Progress | 5.76 | 1.69 | 5.43 | 2.17 | 6.15 | 2.02 | |||||||

| Rewards | 5.37 | 2.28 | 4.42 | 2.32 | 4.00 | 2.26 | |||||||

| Storyline | 5.24 | 3.39 | 7.41 | 2.44 | 7.79 | 2.70 | −0.49 * | ||||||

| Theme | 4.03 | 2.97 | 4.00 | 2.86 | 4.57 | 2.84 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Segundo Díaz, R.L.; Rovelo Ruiz, G.; Bouzouita, M.; Hoste, V.; Coninx, K. Games with a Purpose for Part-of-Speech Tagging and the Impact of the Applied Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment and Games with a Purpose Preference. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073561

Segundo Díaz RL, Rovelo Ruiz G, Bouzouita M, Hoste V, Coninx K. Games with a Purpose for Part-of-Speech Tagging and the Impact of the Applied Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment and Games with a Purpose Preference. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(7):3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073561

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegundo Díaz, Rosa Lilia, Gustavo Rovelo Ruiz, Miriam Bouzouita, Véronique Hoste, and Karin Coninx. 2025. "Games with a Purpose for Part-of-Speech Tagging and the Impact of the Applied Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment and Games with a Purpose Preference" Applied Sciences 15, no. 7: 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073561

APA StyleSegundo Díaz, R. L., Rovelo Ruiz, G., Bouzouita, M., Hoste, V., & Coninx, K. (2025). Games with a Purpose for Part-of-Speech Tagging and the Impact of the Applied Game Design Elements on Player Enjoyment and Games with a Purpose Preference. Applied Sciences, 15(7), 3561. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073561