Abstract

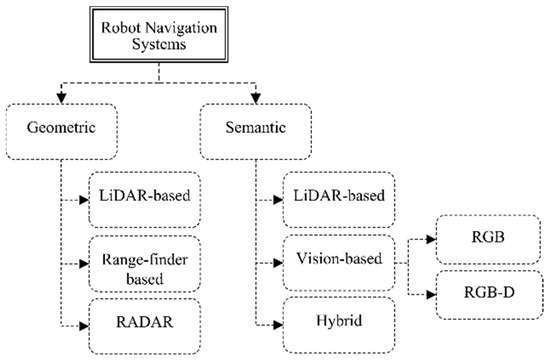

Robot autonomous navigation has become a vital area in the industrial development of minimizing labor-intensive tasks. Most of the recently developed robot navigation systems are based on perceiving geometrical features of the environment, utilizing sensory devices such as laser scanners, range-finders, and microwave radars to construct an environment map. However, in robot navigation, scene understanding has become essential for comprehending the area of interest and achieving improved navigation results. The semantic model of the indoor environment provides the robot with a representation that is closer to human perception, thereby enhancing the navigation task and human–robot interaction. However, semantic navigation systems require the utilization of multiple components, including geometry-based and vision-based systems. This paper presents a comprehensive review and critical analysis of recently developed robot semantic navigation systems in the context of their applications for semantic robot navigation in indoor environments. Additionally, we propose a set of evaluation metrics that can be considered to assess the efficiency of any robot semantic navigation system.

1. Introduction

In the near future, robots will undoubtedly require a deeper understanding of their operational environment and the world around them in order to explore and interact effectively. Autonomous mobile robots are being developed as solutions for various industries, including transportation, manufacturing, education, and defense [1]. These mobile robots have diverse applications, such as monitoring, material handling, search and rescue missions, and disaster assistance. Autonomous robot navigation is another crucial concept in industrial development aimed at reducing manual effort. Often, autonomous robots need to operate in unknown environments with potential obstacles in order to reach their intended destinations [2,3].

Mobile robots, also known as autonomous mobile robots, have been increasingly employed to automate logistics and manual operations. The successful implementation of autonomous mobile robots relies on the utilization of various sensing technologies, such as range-finders, vision systems, and inertial navigation modules. These technologies enable the robots to effectively move from one point to another and navigate the desired area [4].

The process by which a robot selects its own position, direction, and path to reach a destination is referred to as robot navigation. Mobile robots utilize a variety of sensors to scan the environment and gather geometric information about the area of interest [5]. The authors of [6] revealed that the creation or representation of a map is achieved through the simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) approach. Generally, there are two types of SLAM approaches: filter-based and graph-based. The former focuses on the temporal aspect of sensor measurements, while the latter maintains a graph of the robot’s entire trajectory along with landmark locations.

While grid maps are effective for facilitating the point-to-point navigation of mobile robots in small 2D environments, they fall short when it comes to navigating real domestic scenes. This is because grid maps lack semantic information, which makes it difficult for end users to clearly specify the navigation task at hand [7].

On the other hand, a novel concept called semantic navigation has emerged as a result of recent efforts in the field of mobile robotics to integrate semantic data into navigation tasks. Semantic information represents object classes in a way that allows the robot to understand its surrounding environment at a higher level beyond just geometry. Consequently, with the assistance of semantic information, mobile robots can achieve better results in various tasks, including path planning and human–robot interaction [8].

Robots that utilize semantic navigation exhibit a greater similarity to humans in terms of how they model and comprehend their surroundings and how they represent it. Connecting high-level qualities to the geometric details of the low-level metric map is crucial for semantic navigation. High-level information can be extracted from data collected by various sensors, enabling the identification of locations or objects. By adding semantic meaning to the aspects and relationships within a scene, robots can comprehend high-level instructions associated with human concepts [9].

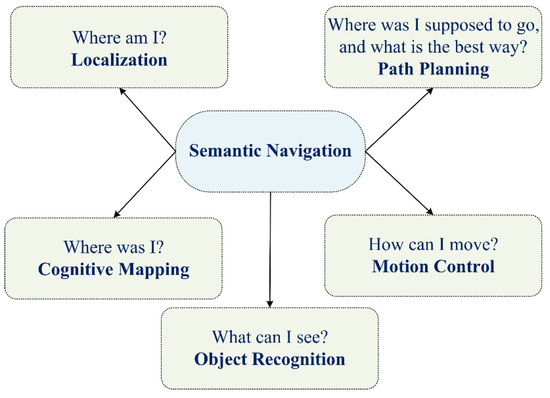

As illustrated in Figure 1, the design and development of a robot semantic navigation system involve several functions: localization, which entails estimating the robot’s position; path planning, which involves determining the available paths in the navigation area; cognitive mapping, which encompasses constructing a map of the area of interest; motion control, which governs how the robot platform moves from one point to another; and object recognition, which involves identifying objects in the area of interest to build a semantic map [10,11].

Figure 1.

Main components of robot semantic navigation.

The area of robot semantic navigation has received considerable attention recently, driven by the requirement to achieve high localization and path planning accuracy, with the ability to accurately recognize things (objects) in the navigation area. Recently, there have been several survey articles that have focused on various aspects of this field. For example, the work presented in [12] surveyed the use of reinforcement learning for autonomous driving, whereas the work discussed in [13] presented an overview of semantic mapping in mobile robotics, focusing on collaborative scenarios, where authors highlighted the importance of semantic maps in enabling robots to reason and make decisions based on the context of their environment. Additionally, the authors of [14] addressed the challenges involved in robot navigation in crowded public spaces, discussing both engineering and human factors that impede the seamless deployment of autonomous robots in such environments. Furthermore, the work presented in [9] explored the role of semantic information in improving robot navigation capabilities. The authors of [15] presented a comprehensive overview of semantic mapping in mobile robotics and highlighted its importance in facilitating communication and interaction between humans and robots.

Several methods and advancements in semantic mapping for mobile robots in indoor environments were discussed in [16], where the authors emphasized the importance of attaching semantic information to geometric maps to enable robots to interact with humans, perform complex tasks, and understand oral commands. On the other hand, the work discussed in [17] aimed to offer a comprehensive overview of semantic visual SLAM (VSLAM) and its potential to improve robot perception and adaptation in complex environments.

In addition, the authors of [18] presented an overview of the importance of semantic understanding for robots to effectively navigate and interact with their environment. The authors emphasized that semantics enable robots to comprehend the meaning and context of the world, enhancing their capabilities. Moreover, the work presented in [19] highlighted the recent advancements in applying semantic information to SLAM, focusing on the combination of semantic information and traditional visual SLAM for system localization and map construction.

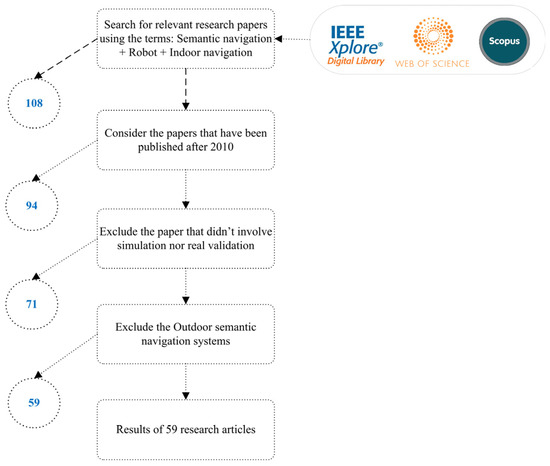

As mentioned earlier, numerous research studies have surveyed the works that target the area of robot semantic navigation for indoor environments. Nevertheless, this paper distinguishes itself from existing works by specifically concentrating on semantic navigation systems designed for indoor settings. This paper goes on to categorize and discuss the various navigation technologies utilized, such as LiDAR, Vision, or Hybrid approaches. Additionally, it delves into the specific requirements for object recognition methods, considering factors such as the number of categorized objects, processing overhead, and memory requirements. Lastly, this paper introduces a set of evaluation metrics aimed at assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of different approaches to robot semantic navigation.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the existing indoor robot semantic navigation systems, while Section 3 examines and compares the results obtained from these systems. Additionally, a list of evaluation metrics is presented. In Section 4, we discuss the lifecycle of developing an efficient robot semantic navigation system. Finally, Section 5 concludes the work presented in this paper.

3. Discussion

Understanding the environment is a crucial aspect of achieving high-level navigation. Semantic navigation, therefore, involves incorporating high-level concepts, such as objects, things, or places, into a navigation framework. Additionally, the relationships between these concepts are utilized, especially with respect to specific objects. By leveraging the knowledge derived from these concepts and their relationships, mobile robots can make inferences about the navigation environment, enabling better planning, localization, and decision-making.

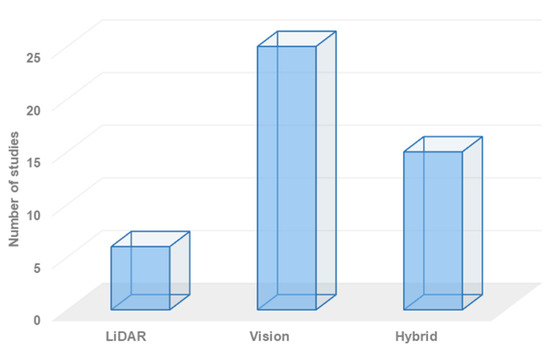

As discussed in the previous section, existing robot semantic navigation systems can be categorized into three distinct types. Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of these systems across the categories. It should be noted that while LiDAR-based systems offer simplicity in terms of data processing tasks, they have limitations when it comes to object classification. Compared to vision-based systems, LiDAR systems have a more limited capacity for recognizing a wide range of labels. As a result, the development of technologies for robot semantic navigation systems that rely solely on LiDAR is less necessary.

Figure 4.

The distribution of robot semantic navigation systems based on the employed technology.

On the one hand, vision-based approaches have gained significant attention in the field of robot navigation, particularly for building semantic navigation maps. However, these systems lack the geometry information that can be obtained from LiDAR sensor units. In contrast, hybrid-based approaches offer the best combination of geometry and semantic information, allowing for the creation of maps with rich details that include both geometry and object classification and localization.

Robot perception plays a crucial role in the functioning of autonomous robots, especially for navigation. To achieve efficient navigation capabilities, the robot system must possess accurate, reliable, and robust perception skills. Vision functions are employed to develop reliable semantic navigation systems, with the primary goal of processing and analyzing semantic information in a scene to provide scene understanding. Scene understanding goes beyond object detection and recognition, involving further analysis and interpretation of the data obtained from sensors. This concept of scene understanding has found practical applications in various domains, including self-driving cars, transportation, and robot navigation. Figure 4 demonstrates that vision-based semantic navigation is the most commonly employed technology in recently developed robot semantic navigation systems for indoor environments.

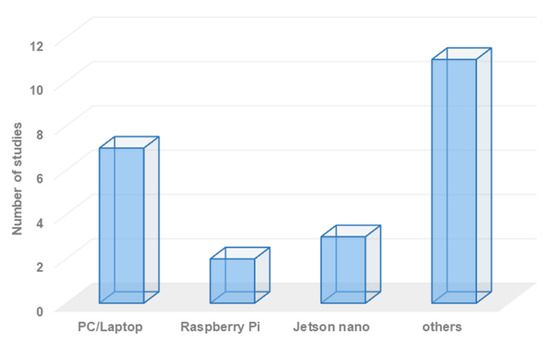

Semantic navigation systems require intensive processing capabilities. Therefore, it is crucial to employ an efficient processor unit to handle and process the data received from onboard sensors, including LiDAR and RGB camera units. Processing RGB and RGB-D images necessitates high processing capabilities for tasks such as object detection, recognition, and localization. Many researchers utilize personal computers integrated with the robot platform to perform these processing tasks. However, incorporating a computer (such as a laptop) onto the robot platform adds extra size, power consumption, cost, and complexity. Alternatively, some researchers have employed processors like Raspberry Pi, Jetson Nano, or Intel Galileo to handle the processing tasks. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of existing robot semantic navigation systems based on the employed processor technology. Raspberry Pi computers are cost-efficient, adaptable, and compact, but they may struggle with complex processing tasks. Jetson Nano offers better specifications than Raspberry Pi but adds an additional cost to the overall robotic system.

Figure 5.

Overall distribution of the existing research works based on employed processor technology.

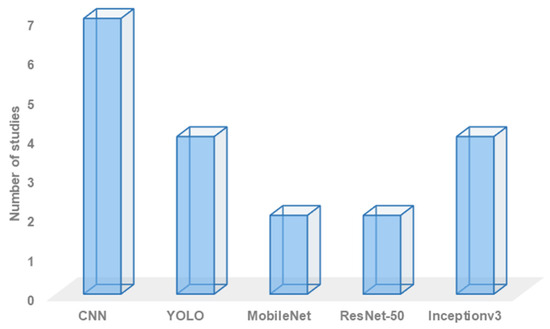

Robot semantic navigation systems necessitate the use of object recognition models to classify various types of objects within the area of interest. Several object recognition models have been developed for this purpose. For example, many researchers choose to develop customized convolutional neural network (CNN) models to classify objects of interest. Others employ models such as YOLO, MobileNet, ResNet, and Inception. The choice of an object recognition model primarily depends on the processor and memory capabilities of the system. Figure 6 provides an overview of the employed object recognition approaches in recently developed semantic navigation systems, offering statistics on their usage.

Figure 6.

Overall statistics on employed object recognition approach.

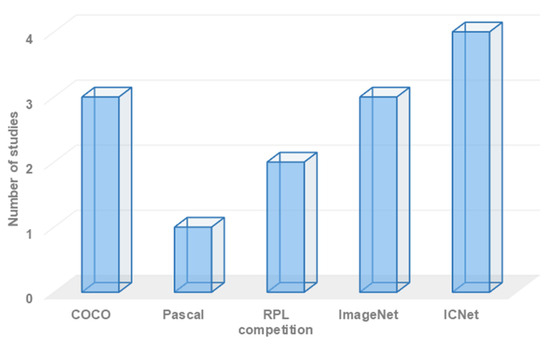

The adoption of object recognition models is fundamentally reliant on the availability of an object recognition dataset. Different datasets vary in terms of the number and type of objects classified within them. Therefore, it is crucial to select the most suitable dataset for a given robot semantic navigation scenario. Figure 7 illustrates the overall distribution of recently developed robot semantic navigation systems based on the employed object recognition dataset, providing an overview of the usage across different datasets.

Figure 7.

Overall statistics on employed object recognition dataset.

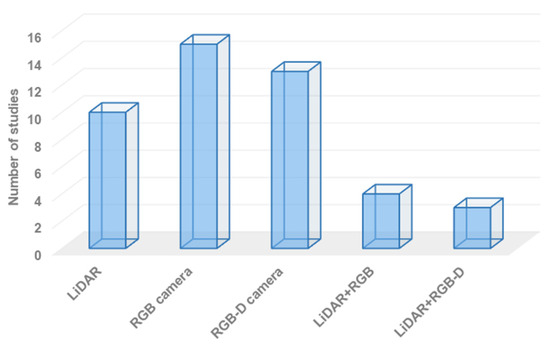

The choice of sensing technology, or perception units, plays a significant role in obtaining an efficient semantic map. Various sensing technologies have been used to gather data about the surrounding environment. Most researchers have focused on using RGB cameras to build semantic maps. RGB cameras are effective for object detection and classification, but they cannot accurately estimate the distance to objects in the area of interest and do not provide geometry information. In contrast, RGB-D cameras offer better results as they can recognize objects and measure the distance to objects in the area of interest, leading to the construction of a more efficient semantic map.

Figure 8 provides an overview of the employed sensing technologies in recently developed systems, presenting statistics on their usage. On the other hand, semantic navigation systems that combine RGB cameras and LiDAR units have the potential to construct a semantic map with rich information. However, these technologies have received less attention due to the higher requirements in terms of processing capabilities, complexity, power consumption, and cost.

Figure 8.

Overall statistics on employed sensing technology.

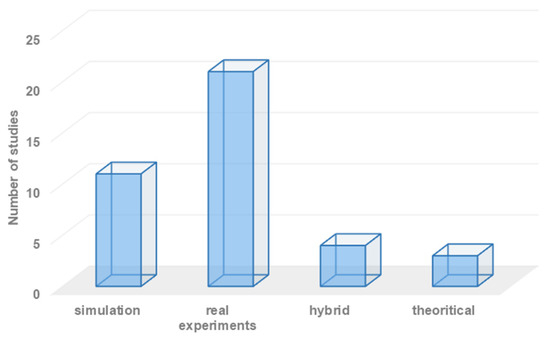

For validation purposes, researchers have the option to employ various experimental testbed environments. Initially, researchers often build their concepts using theoretical models to validate the efficiency of their systems. However, for more reliable and confident results, researchers typically perform either simulation experiments or real-world experiments to validate the effectiveness of the proposed robot semantic navigation system. Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of existing robot semantic navigation systems based on the type of experiment testbed employed.

Figure 9.

Statistics on the employed development environments.

From our perspective, validating robot semantic navigation systems solely through simulation experiments can be challenging. This is because robots need to accurately recognize objects in the area of interest to build an efficient semantic map, and real-time geometry information may be difficult to replicate accurately in simulation environments. Consequently, a large number of researchers rely on real-world experiments for validation purposes, as they provide a more realistic and practical assessment of the system’s performance.

Recent research studies [71,75] have highlighted that the academic community has yet to establish a unified standard for the validation of semantic maps. As a result, there is currently no clear set of validation parameters for assessing the efficiency of robot semantic navigation systems. In light of this, after conducting various analyses and assessments of the validation metrics adopted in recently developed robot semantic navigation systems, we propose a set of validation metrics that can be used to assess the efficiency of any robot semantic navigation system. These metrics are as follows:

- Navigation algorithm: This metric refers to the navigation algorithm employed in the robot semantic navigation system. The SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping) navigation approach is commonly used and can be divided into laser-based SLAM and vision-based SLAM. Laser-based SLAM establishes occupied grid maps, while vision-based SLAM creates feature maps. However, integrating both categories allows for constructing a rich semantic map.

- Array of sensors: This metric involves the list of sensors used in the robot semantic navigation system. Typically, a vision-based system and a LiDAR (light detection and ranging) sensor are required to establish a semantic navigation map. The integration of additional sensors may enhance semantic navigation capabilities, but it also introduces additional processing overhead, power consumption, and design complexity. Therefore, it is important to choose suitable perception units. Several robot semantic navigation systems have employed LiDAR- and vision-based sensors to obtain geometry information, visual information, and proximity information, and the fusion of these sensors has achieved better robustness compared to using individual LiDAR or camera subsystems.

- Vision subsystem: In most semantic navigation systems, the vision subsystem is crucial for achieving high-performance navigation capabilities. Objects can be detected and recognized using an object detection subsystem with a corresponding object detection algorithm. There are currently several object detection classifiers available, each with different accuracy scores, complexity, and memory requirements. Therefore, it is important to choose the most suitable object classification approach based on the specific requirements of the system.

- Employed dataset: For any object detection subsystem, an object classification dataset is required. However, available vision datasets differ in terms of the number of trained objects, size, and complexity. It is important to select a suitable vision dataset that aligns with the robot semantic application [84].

- Experiment testbed: This metric refers to the type of experiment conducted to assess the efficiency of the developed robot semantic navigation system. The system may be evaluated through simulation experiments or real-world experiments [85]. In general, semantic navigation systems require real-world experiments to realistically assess their efficiency.

- Robot semantic application: This metric refers to the type of application for which the developed system has been designed. It is important to determine the specific application in which the navigation system will be employed, since the vision-based system needs to be trained on a dataset that corresponds to the objects that may exist in the navigation environment. Additionally, the selection of suitable perception units largely depends on the structure of the navigation environment.

- Obtained results: This metric primarily concerns the results obtained from the developed robot semantic navigation system. As observed in the previous section, researchers have employed different sets of evaluation metrics to assess the efficiency of their systems. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt the right set of validation metrics to assess the efficiency of a developed robot semantic navigation system.

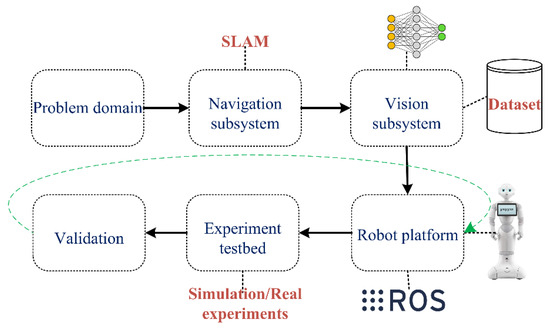

5. Conclusions

The field of robot semantic navigation has gained significant attention in recent years due to the need for robots to understand their environment in order to perform various automated tasks accurately. This paper focused on categorizing and discussing the recently developed robot semantic navigation systems specifically designed for indoor environments.

Furthermore, this paper introduced a set of validation metrics that can be used to accurately assess the efficiency of indoor robot semantic navigation approaches. These metrics provide a standardized framework for evaluating the performance and effectiveness of such systems.

Lastly, this paper presented a comprehensive lifecycle of the design and development of efficient robot semantic navigation systems for indoor environments. This lifecycle encompasses the consideration of robot applications, navigation systems, object recognition approaches, development environments, experimental studies, and the validation process. By following this lifecycle, researchers and developers can effectively design and implement robust robot semantic navigation systems tailored to indoor environments.

Author Contributions

R.A. (Raghad Alqobali) and M.A. reviewed the recent developed vision-based robot semantic navigation systems, whereas A.R. and R.A. (Reem Alnasser) investigated the available LiDAR-based robot semantic navigation systems. O.M.A. discussed and compared the existing robot semantic navigation systems, whereas T.A. proposed a set of evaluation metrics for assessing the efficiency of any robotic semantic navigation system. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alhmiedat, T.; Alotaibi, M. Design and evaluation of a personal Robot playing a self-management for Children with obesity. Electronics 2022, 11, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.; Rahiman, W.; Nazli Alhady, S.S. A comprehensive study for robot navigation techniques. Cogent Eng. 2019, 6, 1632046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmiedat, T.; Marei, A.M.; Albelwi, S.; Bushnag, A.; Messoudi, W.; Elfaki, A.O. A Systematic Approach for Exploring Underground Environment Using LiDAR-Based System. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 136, 2321–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Jiménez, F.; Naranjo, J.E.; Zato, J.G.; Aparicio, F.; Armingol, J.M.; de la Escalera, A. Environment perception based on LIDAR sensors for real road applications. Robotica 2012, 30, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmiedat, T.; Marei, A.M.; Messoudi, W.; Albelwi, S.; Bushnag, A.; Bassfar, Z.; Alnajjar, F.; Elfaki, A.O. A SLAM-based localization and navigation system for social robots: The pepper robot case. Machines 2023, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, C.; Neira, J.; Tardós, J.D. Hierarchical SLAM: Real-time accurate mapping of large environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2005, 21, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, T. Deep reinforcement learning based mobile robot navigation: A review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.V.; Bui, N.T. Multi-scale fully convolutional network-based semantic segmentation for mobile robot navigation. Electronics 2023, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, J.; Castillo, J.C.; Mozos, O.M.; Barber, R. Semantic information for robot navigation: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, S.; Alamri, H.; Alshehri, W.; Alshehri, S.; Alaklabi, A.; Alhmiedat, T. An Autonomous Maze-Solving Robotic System Based on an Enhanced Wall-Follower Approach. Machines 2023, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmiedat, T. Fingerprint-Based Localization Approach for WSN Using Machine Learning Models. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, B.R.; Sobh, I.; Talpaert, V.; Mannion, P.; Al Sallab, A.A.; Yogamani, S.; Pérez, P. Deep reinforcement learning for autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 4909–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, A.; Al-Assaad, H.; Dupuis, Y.; El Zaher, M. Collaborative Mobile Robotics for Semantic Mapping: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogiannis, C.; Baldini, F.; Wang, A.; Zhao, D.; Trautman, P.; Steinfeld, A.; Oh, J. Core challenges of social robot navigation: A survey. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2023, 12, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Semantic mapping for mobile robotics tasks: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 66, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W. Semantic mapping for mobile robots in indoor scenes: A survey. Information 2021, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Tong, Q.; Liu, R.; Chen, S. Semantic Visual Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.06428. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Sünderhauf, N.; Dayoub, F.; Morrison, D.; Cosgun, A.; Carneiro, G.; Wu, Q.; Chin, T.J.; Reid, I.; Gould, S.; et al. Semantics for robotic mapping, perception and interaction: A survey. Found. Trends® Robot. 2020, 8, 1–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; He, W.; Zhu, S.-Q.; Li, Y.-H.; Xie, T. Survey of simultaneous localization and mapping based on environmental semantic information. Chin. J. Eng. 2021, 43, 754–767. [Google Scholar]

- Alamri, S.; Alshehri, S.; Alshehri, W.; Alamri, H.; Alaklabi, A.; Alhmiedat, T. Autonomous maze solving robotics: Algorithms and systems. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Robot. Res 2021, 10, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humblot-Renaux, G.; Marchegiani, L.; Moeslund, T.B.; Gade, R. Navigation-oriented scene understanding for robotic autonomy: Learning to segment driveability in egocentric images. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 2913–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Im, J.; Rhee, J.; Hodgson, M. Building type classification using spatial and landscape attributes derived from LiDAR remote sensing data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 130, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, C.; Chasmer, L.; Gynan, C.; Mahoney, C.; Sitar, M. Multisensor and multispectral lidar characterization and classification of a forest environment. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 42, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, M.W.; Nishihata, T.; Brooks, C.A.; Iagnemma, K. Ground plane identification using LIDAR in forested environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–8 May 2010; pp. 3831–3836. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Aparicio, C.; Guerrero-Higueras, A.M.; Rodríguez-Lera, F.J.; Ginés Clavero, J.; Martín Rico, F.; Matellán, V. People detection and tracking using LIDAR sensors. Robotics 2019, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, A.; Oliveira, G.L.; Burgard, W. Deep semantic classification for 3D LiDAR data. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 3544–3549. [Google Scholar]

- Alenzi, Z.; Alenzi, E.; Alqasir, M.; Alruwaili, M.; Alhmiedat, T.; Alia, O.M. A Semantic Classification Approach for Indoor Robot Navigation. Electronics 2022, 11, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Gladkova, M.; Wang, R.; Li, Q.; Stilla, U.; Henriques, J.F.; Cremers, D. CASSP R: Cross Attention Single Scan Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 30 September–6 October 2023; pp. 8461–8472. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Stilla, U. VPC-Net: Completion of 3D vehicles from MLS point clouds. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 174, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teso-Fz-Betoño, D.; Zulueta, E.; Sánchez-Chica, A.; Fernandez-Gamiz, U.; Saenz-Aguirre, A. Semantic segmentation to develop an indoor navigation system for an autonomous mobile robot. Mathematics 2020, 8, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Adachi, M.; Nakajima, T.; Ishida, H.; Kojima, K.; Aoki, R.; Oki, T.; Kobayashi, S. Vision-based road-following using results of semantic segmentation for autonomous navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE-Berlin), Berlin, Germany, 8–11 September 2019; pp. 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah, Y.; Yanguang, C.; Wu, W.; Farisi, Z. Semantic scene segmentation for indoor robot navigation via deep learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Robotics, Control and Automation, Chengdu, China, 11–13 August 2018; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavian, A.; Toshev, A.; Fišer, M.; Košecká, J.; Wahid, A.; Davidson, J. Visual representations for semantic target driven navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 8846–8852. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, C.; Fernández-Madrigal, J.A.; González, J.; Saffiotti, A. Robot task planning using semantic maps. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2008, 56, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravall, D.; De Lope, J.; Fuentes, J.P. Navigation and self-semantic location of drones in indoor environments by combining the visual bug algorithm and entropy-based vision. Front. Neurorobotics 2017, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Mei, G.; Yuan, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Visual SLAM for robot navigation in healthcare facility. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 113, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.C.; Gómez, C.; Crespo, J.; Barber, R. Object classification in natural environments for mobile robot navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2016 International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions (ICARSC), Bragança, Portugal, 4–6 May 2016; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Wang, W.J.; Huang, S.K.; Chen, H.C. Learning based semantic segmentation for robot navigation in outdoor environment. In Proceedings of the 2017 Joint 17th World Congress of International Fuzzy Systems Association and 9th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems (IFSA-SCIS), Otsu, Japan, 27–30 June 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgun, A.; Christensen, H.I. Context-aware robot navigation using interactively built semantic maps. Paladyn J. Behav. Robot. 2018, 9, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Huo, G.; Li, R.; Hou, Z.; Luo, P.; Sun, Z.; Wang, K.; Yang, C. Visual semantic navigation based on deep learning for indoor mobile robots. Complexity 2018, 2018, 1627185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kästner, L.; Marx, C.; Lambrecht, J. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based semantic navigation of mobile robots in dynamic environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Hong Kong, China, 20–21 August 2020; pp. 1110–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Astua, C.; Barber, R.; Crespo, J.; Jardon, A. Object detection techniques applied on mobile robot semantic navigation. Sensors 2014, 14, 6734–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ren, J. A semantic map for indoor robot navigation based on predicate logic. Int. J. Knowl. Syst. Sci. (IJKSS) 2020, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, R.; Adachi, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Ishida, H.; Kobayashi, S. Accuracy improvement of semantic segmentation using appropriate datasets for robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Paris, France, 23–26 April 2019; pp. 1610–1615. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, K.; Roennau, A.; Dillmann, R. From structure to actions: Semantic navigation planning in office environments. In Proceedings of the IROS 2011 Workshop on Perception and Navigation for Autonomous Vehicles in Human Environment (Cited on Page 24). 2011. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Arne-Roennau/publication/256198760_From_Structure_to_Actions_Semantic_Navigation_Planning_in_Office_Environments/links/6038f20ea6fdcc37a85449ad/From-Structure-to-Actions-Semantic-Navigation-Planning-in-Office-Environments.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Sun, H.; Meng, Z.; Ang, M.H. Semantic mapping and semantics-boosted navigation with path creation on a mobile robot. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems (CIS) and IEEE Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics (RAM), Ningbo, China, 19–21 November 2017; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann, J.; Jochmann, G.; Bluemel, F. Semantic navigation maps for mobile robot localization on planetary surfaces. In Proceedings of the 12th Symposium on Advanced Space Technologies in Robotics and Automation (ASTRA 2013), Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 15–17 May 2013; Volume 9, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, S.H.; Manzoor, S.; Rocha, Y.G.; Bae, S.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kuc, T.Y.; Kim, M. Autonomous navigation framework for intelligent robots based on a semantic environment modeling. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazuelo, L.; Tenorth, M.; Di Marco, D.; Salas, M.; Gálvez-López, D.; Mösenlechner, L.; Kunze, L.; Beetz, M.; Tardós, J.D.; Montano, L.; et al. RoboEarth semantic mapping: A cloud enabled knowledge-based approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2015, 12, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, J.; Barber, R.; Mozos, O.M. Relational model for robotic semantic navigation in indoor environments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 86, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Shatari, S.; Miyamoto, R. Visual navigation using a webcam based on semantic segmentation for indoor robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2019 15th International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems (SITIS), Sorrento, Italy, 26–29 November 2019; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Posada, L.F.; Hoffmann, F.; Bertram, T. Visual semantic robot navigation in indoor environments. In Proceedings of the ISR/Robotik 2014; 41st International Symposium on Robotics, Munich, Germany, 2–3 June 2014; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, L.; Blumenthal, S.; Huebel, N.; Bruyninckx, H.; Prassler, E. Semantic mapping extension for OpenStreetMap applied to indoor robot navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 3839–3845. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Hou, H.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Li, D.; Cao, F.; Wang, B. Efficient Mobile Robot Navigation Based on Federated Learning and Three-Way Decisions. In International Conference on Neural Information Processing; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 408–422. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, R.; Du, J.; Cremers, D.; Stilla, U. SOE-Net: A self-attention and orientation encoding network for point cloud based place recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 11348–11357. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi, K.; Chen, P.; Han, K.; Wu, T.; Lobaton, E. Real-time scene segmentation using a light deep neural network architecture for autonomous robot navigation on construction sites. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2019; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, I.; Riazuelo, L.; Murillo, A.C. Mininet: An efficient semantic segmentation convnet for real-time robotic applications. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Seok, J. Indoor semantic segmentation for robot navigating on mobile. In Proceedings of the 2018 Tenth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Prague, Czech Republic, 3–6 July 2018; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S.K.; Lee, Y.; Jawed, M.K. Agronav: Autonomous Navigation Framework for Agricultural Robots and Vehicles using Semantic Segmentation and Semantic Line Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 6271–6280. [Google Scholar]

- Kiy, K.I. Segmentation and detection of contrast objects and their application in robot navigation. Pattern Recognit. Image Anal. 2015, 25, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, Y.; Wada, K.; Murooka, M.; Nozawa, S.; Kakiuchi, Y.; Okada, K.; Inaba, M. Transformable semantic map based navigation using autonomous deep learning object segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE-RAS 16th International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids), Cancun, Mexico, 15–17 November 2016; pp. 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, T.V.; Tran, D.M.C.; Tan, P.X. IRDC-Net: Lightweight Semantic Segmentation Network Based on Monocular Camera for Mobile Robot Navigation. Sensors 2023, 23, 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouilly, R.; Rives, P.; Morisset, B. Semantic representation for navigation in large-scale environments. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 1106–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Rabindran, D.; Mohareri, O. RGB-D Semantic SLAM for Surgical Robot Navigation in the Operating Room. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05467. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Xu, F.; Yao, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, S. Navigation algorithm based on semantic segmentation in wheat fields using an RGB-D camera. Inf. Process. Agric. 2023, 10, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghi, D.; Cerrato, S.; Mazzia, V.; Chiaberge, M. Deep semantic segmentation at the edge for autonomous navigation in vineyard rows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 3421–3428. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, B.; Dai, X. A visual navigation method of mobile robot using a sketched semantic map. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2012, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Huang, K.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, C.; Guo, R.; Zhang, H. Semantic RGB-D SLAM for rescue robot navigation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 221320–221329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boularias, A.; Duvallet, F.; Oh, J.; Stentz, A. Grounding spatial relations for outdoor robot navigation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 1976–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Wang, W.; Yuan, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Xue, L.; Sun, Y. Building semantic grid maps for domestic robot navigation. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 1729881419900066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, W.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Wei, R. Object semantic grid mapping with 2D LiDAR and RGB-D camera for domestic robot navigation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplot, D.S.; Gandhi, D.P.; Gupta, A.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Object goal navigation using goal-oriented semantic exploration. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 4247–4258. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hussain, B.; Yue, C.P. VLP Landmark and SLAM-Assisted Automatic Map Calibration for Robot Navigation with Semantic Information. Robotics 2022, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, B.; Dayoub, F.; Corke, P.; Wyeth, G. Robot navigation in unseen spaces using an abstract map. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2020, 13, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, A.; Siemiatkowska, B.; Szklarski, J. Towards semantic navigation in mobile robotics. In Graph Transformations and Model-Driven Engineering: Essays Dedicated to Manfred Nagl on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 719–748. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchlaghem, D.; Shang, H.; Whyte, J.; Ganah, A. Visualization in architecture, engineering and construction (AEC). Autom. Constr. 2005, 14, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersan, D.; Martins, R.; Campos, M.; Nascimento, E.R. Semantic map augmentation for robot navigation: A learning approach based on visual and depth data. In Proceedings of the 2018 Latin American Robotic Symposium, 2018 Brazilian Symposium on Robotics (SBR) and 2018 Workshop on Robotics in Education (WRE), Joȧo Pessoa, Brazil, 6–10 November 2018; pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R.; Bersan, D.; Campos, M.F.; Nascimento, E.R. Extending maps with semantic and contextual object information for robot navigation: A learning-based framework using visual and depth cues. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2020, 99, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, S.; Carreno-Medrano, P.; Cousgun, A.; Croft, E.; Chan, W.P. Autonomous social robot navigation in unknown urban environments using semantic segmentation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.11903. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Mei, W.; Pan, W. Building a grid-semantic map for the navigation of service robots through human–robot interaction. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2015, 1, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.H.; Manzoor, S.; Rocha, Y.G.; Lee, H.U.; Kuc, T.Y. A realtime autonomous robot navigation framework for human like high-level interaction and task planning in global dynamic environment. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.12942. [Google Scholar]

- Wellhausen, L.; Ranftl, R.; Hutter, M. Safe robot navigation via multi-modal anomaly detection. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, R.; Adachi, M.; Ishida, H.; Watanabe, T.; Matsutani, K.; Komatsuzaki, H.; Sakata, S.; Yokota, R.; Kobayashi, S. Visual navigation based on semantic segmentation using only a monocular camera as an external sensor. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2020, 32, 1137–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Young, S. A survey of public datasets for computer vision tasks in precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmiedat, T.; Alotaibi, M. Employing Social Robots for Managing Diabetes Among Children: SARA. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 130, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, D.H.; Welfer, D.; De Souza Leite Cuadros, M.A.; Gamarra, D.F.T. Mobile robot navigation using an object recognition software with RGBD images and the YOLO algorithm. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 1290–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmiedat, T.A.; Abutaleb, A.; Samara, G. A prototype navigation system for guiding blind people indoors using NXT Mindstorms. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2013, 9, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftf, M.; Ayachi, R.; Said, Y.; Pissaloux, E.; Atri, M. Indoor object c1assification for autonomous navigation assistance based on deep CNN model. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Measurements & Networking (M&N), Catania, Italy, 8–10 July 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).