Unraveling the Usage Characteristics of Human Element, Human Factor, and Human Error in Maritime Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

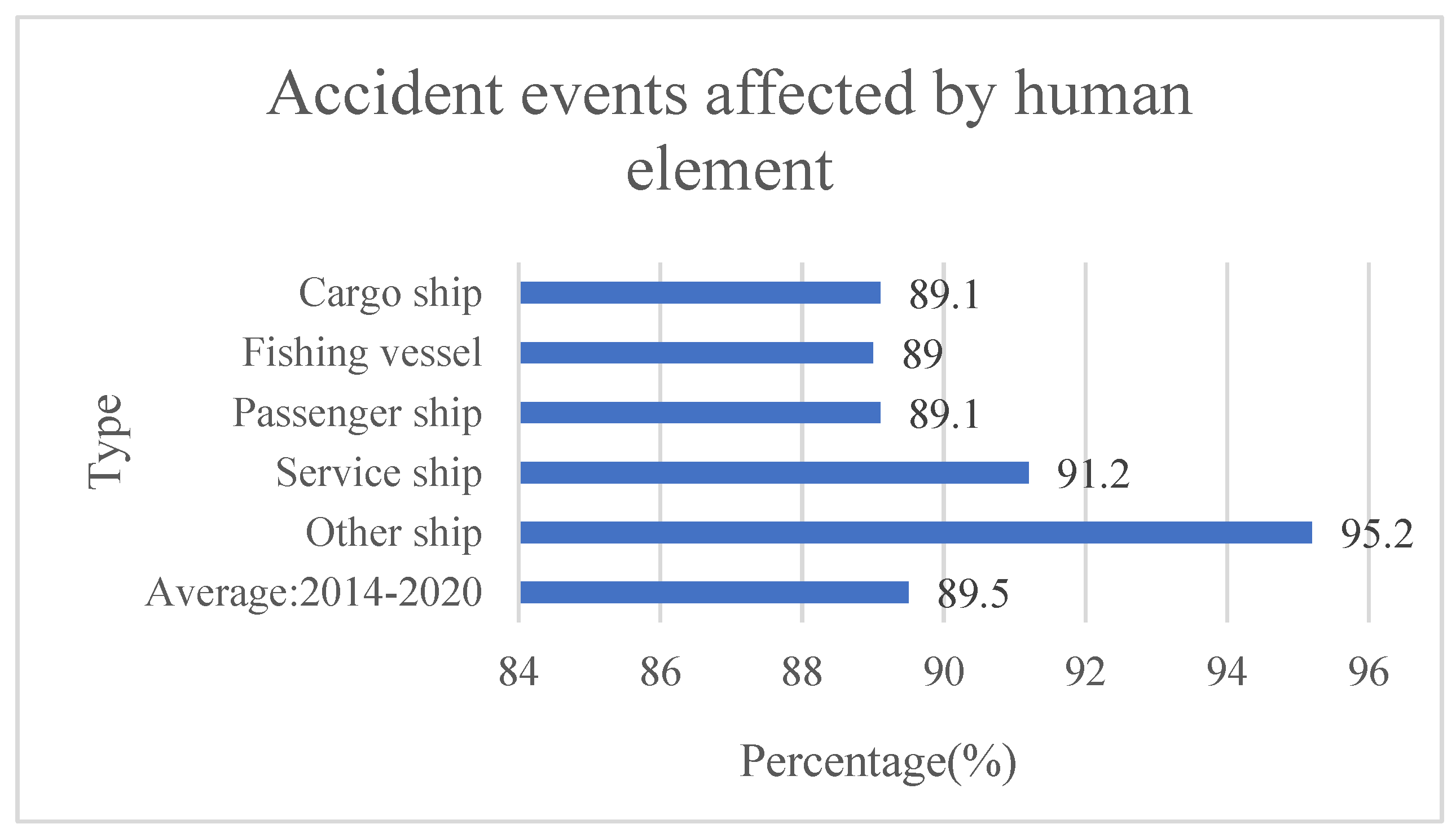

1.1. Significance

1.2. Objective and Scope of the Study

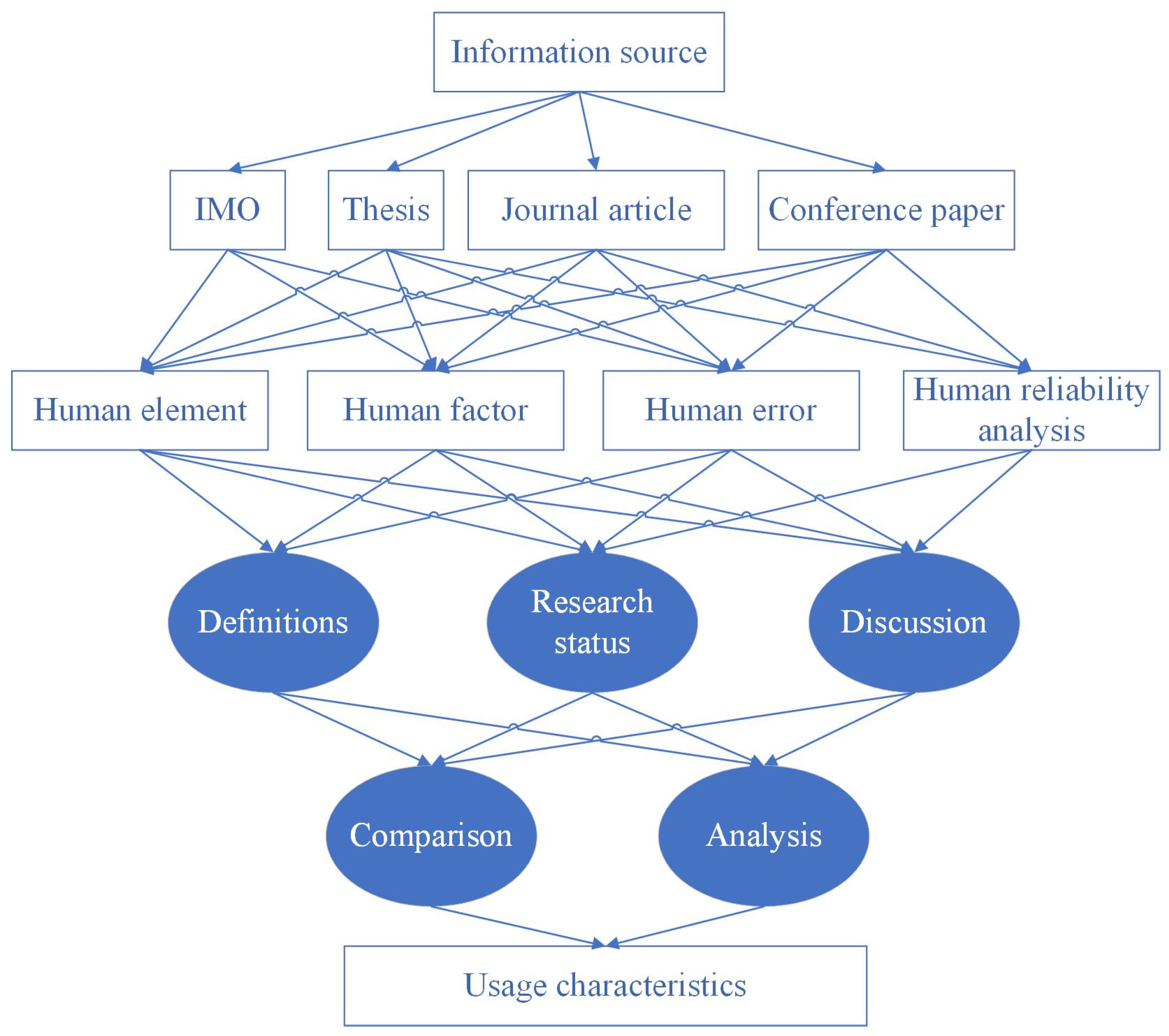

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources

2.2. Selection Principle

2.3. Outcomes

3. Results and Discussion

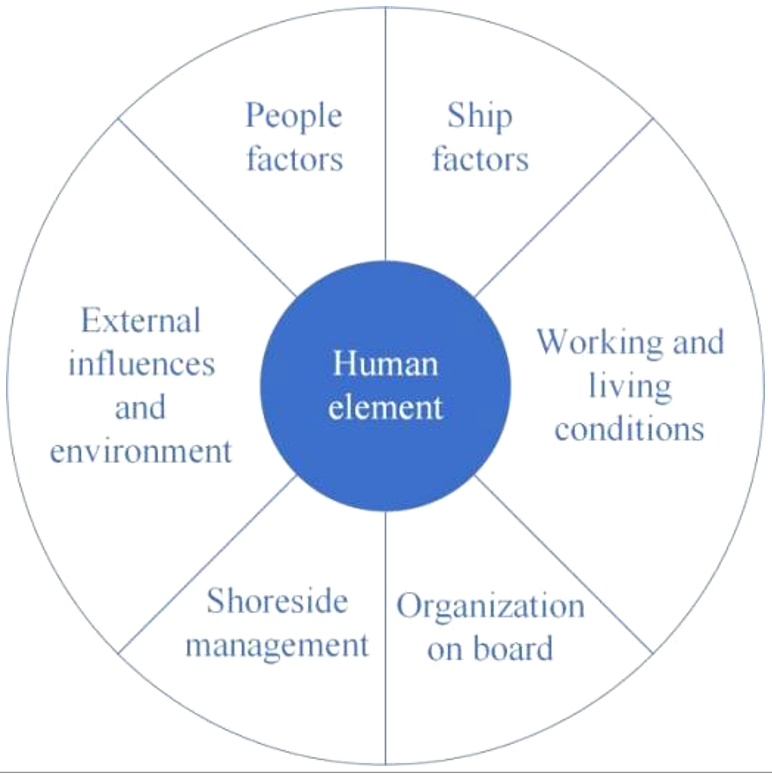

3.1. Human Element

3.1.1. Definition

3.1.2. Research Status

3.1.3. Discussion

3.2. Human Factor

3.2.1. Definition

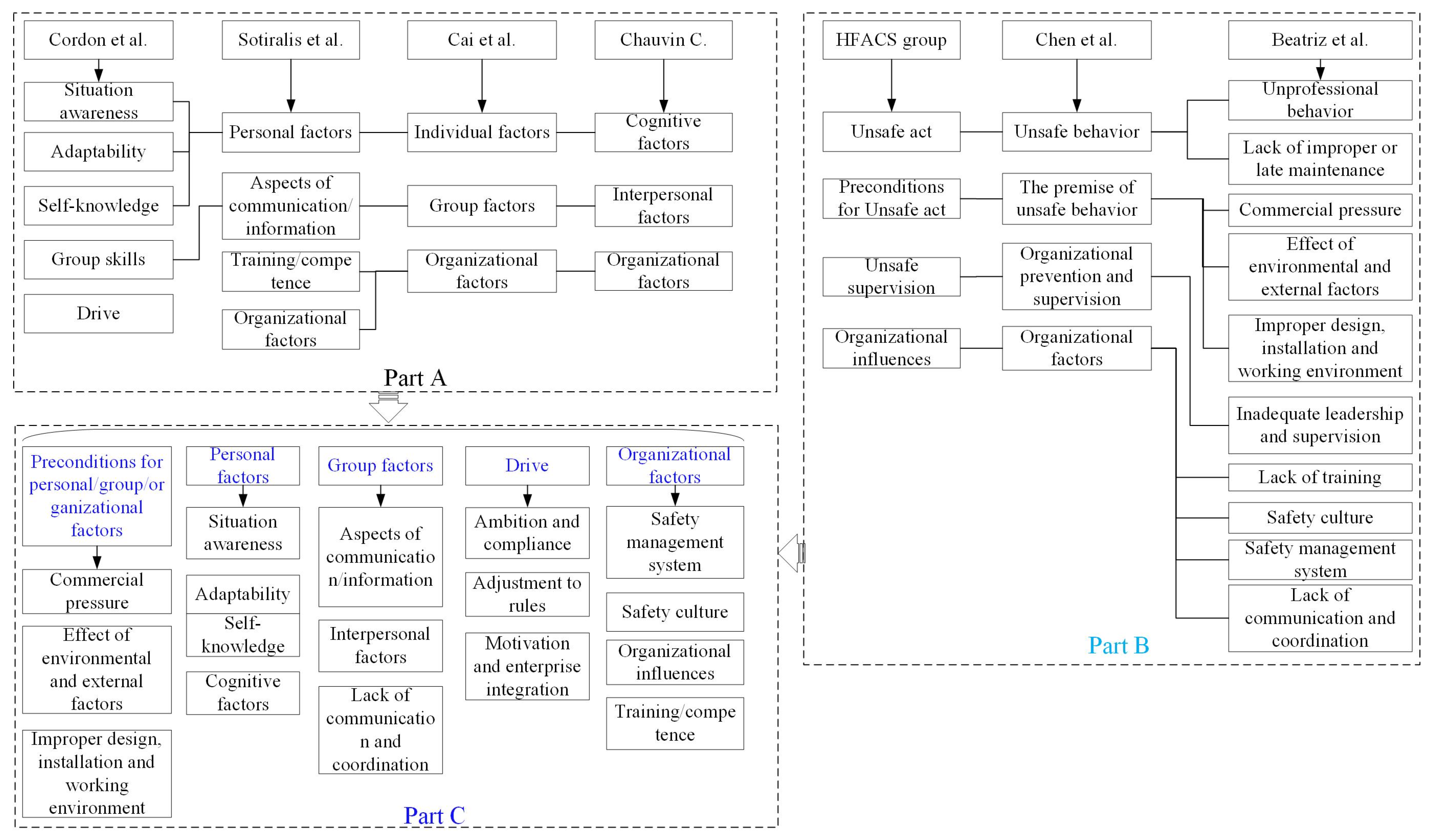

3.2.2. Research Status

Research Article

Literature Review

3.2.3. Discussion

3.3. Human Error

3.3.1. Definition

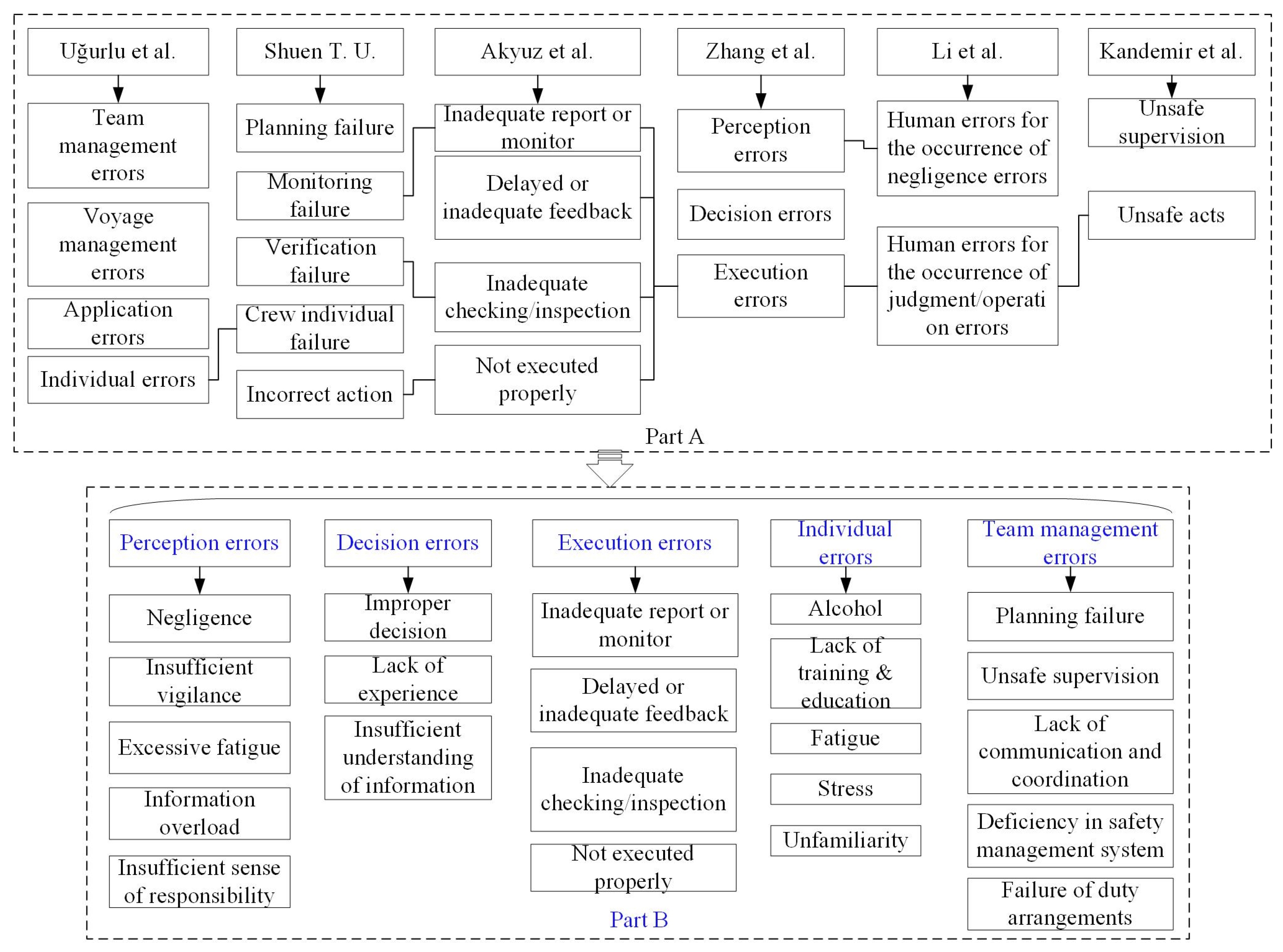

3.3.2. Research Status

Research Article

Literature Review

3.3.3. Discussion

3.4. Human Reliability Analysis

Research Status and Discussion

3.5. Usage Characteristics of the Three Terms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Articles with Human Element in the Title

| Ref. | Title | Year | Journal | Doc. Type | Res. Method | Remarks |

| Liliana Viorica Popa [26] | The Contribution of the Human Element in Shipping Companies | 2016 | WLC 2016: World LUMEN Congress | Conference paper | Qualitative analysis | Primary article |

| F. Paolo [28] | Investigating the Role of the Human Element in Maritime Accidents using Semi-Supervised Hierarchical Methods | 2021 | Transportation Research Procedia | Conference paper | Accident reports, semi-supervised hierarchical method | Primary article |

| V. R. Juan [27] | The Human Element in Shipping Casualties as a Process of Risk Homeostasis of the Shipping Business | 2013 | The Journal of Navigation | Journal article | Accident reports, empirical investigation | Primary article |

| Mallam et al. [29] | The Human Element in Future Maritime Operations-Perceived Impact of Autonomous Shipping | 2019 | Ergonomics | Journal article | Questionnaire survey, data analysis | Primary article |

| Baumler et al. [31] | Quantification of influence and interest at IMO in Maritime Safety and Human Element matters | 2021 | Marine Policy | Journal article | Quantitative method | Primary article |

| Barnett et al. [32] | The Human Element in Shipping | 2017 | Encyclopedia of Maritime and Offshore Engineering | Journal article | Qualitative analysis | Quaternay article |

| Ahvenjärvi S. [30] | The human element and autonomous ships. | 2016 | The international journal on marine navigation and safety of sea transportation | Journal article | Qualitative analysis | Primary article |

Appendix B. List of Articles with Human Factor in the Title

| Ref. | Title | Year | Journal | Doc. Type | Res. Method | Remarks |

| Ćorovic et al. [69] | Research of Marine Accidents through the Prism of Human Factors | 2013 | Promet—Traffic&Transportation | Conference paper | Regression analysis | Primary article |

| Mikael et al. [70] | Human factors challenges in unmanned ship operations -insights from other domains | 2015 | Procedia Manufacturing | Conference paper | Literature review | Primary article |

| Praetorius et al. [71] | Increased awareness for maritime human factors through e-learning in crew-centered design | 2015 | Procedia Manufacturing | Conference paper | TRACEr technique, accident reports | Primary article |

| Özdemir et al. [72] | Strategic Approach Model for Investigating the Cause of Maritime Accidents | 2015 | Promet—Traffic&Transportation | Conference paper | DEMATEL-ANP model, accident reports | Primary article |

| A. Galieriková [73] | The human factor and maritime safety | 2019 | Transportation Research Procedia | Conference paper | HFACS model | Primary article |

| Wang et al. [74] | Causing Mechanism Analysis of Human Factors in the Marine Safety Management Based on the Entropy | 2012 | Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE IEEM | Conference paper | entropy-based vulnerability theory | Primary article |

| Xi Y. T. [75] | HFACS Model Based Data Mining of Human Factors-A Marine Study | 2010 | Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE IEEM | Conference paper | HFACS model | Primary article |

| M. Nakamura [76] | Relationship Between Characteristics of Human Factors Based on Marine Accident Analysis | 2015 | Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE IEEM | Conference paper | Covariance structure analysis, accident reports | Primary article |

| Dai et al. [77] | The Human Factors Analysis of Marine Accidents Based on Goal Structure Notion | 2011 | Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE IEEM | Conference paper | GSN model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Hu et al. [78] | Towards a HFACS and Bayesian Belief Network model to Analysis Collision Risk Causal on Ship Pilotage Process | 2021 | The 6th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety | Conference paper | HFACS-BBN model | Primary article |

| Karvonen et al. [79] | Human Factors Issues in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship Systems Development | 2018 | International Conference on Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships | Conference paper | Simulation | Primary article |

| Christine Chauvin [80] | Human Factors and Maritime Safety | 2011 | The Journal of Navigation | Journal article | Literature review | Primary article |

| Cai et al. [48] | A dynamic Bayesian networks modeling of human factors on offshore blowouts | 2013 | Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries | Journal article | DBN model | Primary article |

| Chauvin et al. [41] | Human and organizational factors in maritime accidents: Analysis of collisions at sea using the HFACS | 2013 | Accident Analysis and Prevention | Journal article | HFACS model | Secondary article |

| Woodcock et al. [35] | Human factors issues in the management of emergency response at high hazard installations | 2013 | Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries | Journal article | Emergency response approach | Secondary article |

| Hinrichs et al. [51] | Maritime human factors and IMO policy | 2013 | Maritime policy&management | Journal article | Literature review | Primary article |

| Sarıalioglu et al. [38] | A hybrid model for human-factor analysis of engine-room fires on ships: HFACS-PV&FFTA | 2020 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | HFACS-PV&FFTA model | Primary article |

| Maya et al. [47] | Application of card-sorting approach to classify human factors of past maritime accidents | 2020 | Maritime policy&management | Journal article | card-sorting approach | Primary article |

| Zhang et al. [81] | Dynamics Simulation of the Risk Coupling Effect between Maritime Pilotage Human Factors under the HFACS Framework | 2020 | Journal of marine science and engineering | Journal article | HFACS-SD model | Tertiary article |

| Kaptan et al. [9] | The evolution of the HFACS method used in analysis of marine accidents: A review | 2021 | International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics | Journal article | Literature review | Primary article |

| Li et al. [43] | Use of HFACS and Bayesian network for human and organizational factors analysis of ship collision accidents in the Yangtze River | 2021 | Maritime policy &management | Journal article | HFACS-BN model | Primary article |

| Khan et al. [44] | A data centered human factor analysis approach for hazardous cargo accidents in a port environment | 2022 | Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries | Journal article | HFACS-PEHCA model | Primary article |

| Chen et al. [42] | A Human and Organisational Factors (HOFs) analysis method for marine casualties using HFACS-Maritime Accidents | 2013 | Safety science | Journal article | HFACS-MA model | Secondary article |

| Qiao et al. [14] | A methodology to evaluate human factors contributed to maritime accident by mapping fuzzy FT into ANN based on HFACS | 2020 | Ocean engineering | Journal article | HFACS-FTA-ANN model | Primary article |

| Yildiz et al. [39] | Application of the HFACS-PV approach for identification of human and organizational factors (HOFs) influencing marine accidents | 2021 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | HFACS-PV model | Primary article |

| Yıldırım et al. [82] | Assessment of collisions and grounding accidents with human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS) and statistical methods | 2019 | Safety science | Journal article | HFACS model | Primary article |

| Kandemir et al. [60] | Determining the error producing conditions in marine engineering maintenance and operations through HFACS-MMO | 2021 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | HFACS-MMO model | Primary article |

| Coraddu et al. [37] | Determining the most influential human factors in maritime accidents: A data-driven approach | 2020 | Ocean engineering | Journal article | Data driven approach | Primary article |

| Corrigan et al. [52] | Human factors & safety culture: Challenges & opportunities for the port environment | 2020 | Safety science | Journal article | socio-technical systems approach | Primary article |

| Chandrasegaran et al. [83] | Human factors engineering integration in the offshore O&G industry: A review of current state of practice | 2020 | Safety science | Journal article | Literature review | Primary article |

| Cordon et al. [46] | Human factors in seafaring: The role of situation awareness. | 2017 | Safety science | Journal article | Structural equation-modeling method | Primary article |

| Do-Hoon Kim [55] | Human factors influencing the ship operator’s perceived risk in the last moment of collision encounter | 2020 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | Multiple regression analyses | Primary article |

| Fan et al. [84] | Incorporation of human factors into maritime accident analysis using a data driven Bayesian network | 2020 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | data-driven BN model | Primary article |

| Sotiralis et al. [49] | Incorporation of human factors into ship collision risk models focusing on human centred design aspects | 2016 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | TRACEr- BN model | Primary article |

| Fan et al. [50] | Maritime accident prevention strategy formulation from a human factor perspective using Bayesian Networks and TOPSIS | 2020 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | BN-TOPSIS model | Primary article |

| Ugurlu et al. [40] | Modified human factor analysis and classification system for passenger vessel accidents (HFACS-PV) | 2018 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | HFACS-PV model | Primary article |

| Chen et al. [45] | Research on human factors cause chain of ship accidents based on multidimensional association rules | 2020 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | Reason-SHEL-AR model | Primary article |

| Wu et al. [20] | Review of techniques and challenges of human and organizational factors analysis in maritime transportation | 2022 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | Literature review | Primary article |

| Shi et al. [85] | Structured survey of human factor-related maritime accident research | 2021 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | Literature review | Primary article |

| Zhang et al. [86] | Use of HFACS and fault tree model for collision risk factors analysis of icebreaker assistance in ice-covered waters | 2019 | Safety Science | Journal article | HFACS-FTA model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Soner et al. [87] | Use of HFACS–FCM in fire prevention modelling on board ships | 2015 | Safety Science | Journal article | HFACS-FCM model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Mallam et al. [88] | Integrating Human Factors & Ergonomics in large-scale engineering projects: Investigating a practical approach for ship design | 2015 | International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics | Journal article | Comparison, interview, link analysis | Tertiary article |

| Rumawas, Vincentius [89] | Human Factors in Ship Design and Operation: Experiential Learning | 2016 | Norwegian University of Science and Technology | Dissertation | Literature review, empirical studies theoretical approach | Primary article |

| Casarosa, L. [90] | The integration of human factors, operability and personnel movement simulation into the preliminary design of ships utilising the design building block approach | 2011 | University of London | Dissertation | Modelling simulation | Primary article |

Appendix C. List of Articles with Human Error in the Title

| Ref. | Title | Year | Journal | Doc. Type | Res. Method | Remarks |

| Yang et al. [91] | Brittle Relationship Analysis of Human Error Accident of Warship Technology Supportability System Based on Set Pair Analysis | 2018 | 7th International Conference on Industrial Technology and Management | Conference paper | Accident reports, Reason-SHEL model | Primary article |

| Özdemir et al. [72] | Strategic approach model for investigating the cause of maritime accidents | 2015 | Promet- Traffic & Transportation | Conference paper | DEMATEL-ANP model, | Primary article |

| Saragih et al. [92] | Analysis of Damage to Ship MT. Delta Victory due to Human Error and Electricity with the Shel Method | 2020 | 4th International Conference on Electrical, Telecommunication and Computer Engineering | Conference paper | AHP-Shell model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Uğurlu et al. [57] | Analysis of grounding accidents caused by human error | 2015 | Journal of Marine Science and Technology | Journal article | AHP model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Islam et al. [93] | Determination of Human Error Probabilities for the Maintenance Operations of Marine Engines | 2016 | Journal of Ship Production and Design | Journal article | SLIM model, | Secondary article |

| Emre Akyuz [94] | Quantitative human error assessment during abandon ship procedures in maritime transportation | 2016 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | SLIM model, | Primary article |

| Y.T. Xi [95] | A new hybrid approach to human error probability quantification– applications in maritime operations | 2017 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | CREAM model with ER and DEMATEL approach | Primary article |

| Wang W. Z. [96] | A hybrid evaluation method for human error probability by using extended DEMATEL with Z-numbers: A case of cargo loading operation | 2021 | International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics | Journal article | HEART model with DEMATEL method | Secondary article |

| Zaloa Sanchez-Varela [97] | Determining the likelihood of incidents caused by human error during dynamic positioning drilling operations | 2021 | The Journal of Navigation | Journal article | binary logistic regression model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Shokoufeh Abrishami [98] | A data-based comparison of BN-HRA models in assessing human error probability: An offshore evacuation case study | 2020 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | BN-HRA models | Primary article |

| Xiangkun Meng [99] | A novel methodology to analyze accident path in deepwater drilling operation considering uncertain information | 2021 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | directed acyclic graph and risk entropy model | Primary article |

| Akyuz et al. [100] | A phase of comprehensive research to determine marine-specific EPC values in human error assessment and reduction technique | 2016 | Safety Science | Journal article | Majority Rule, HEART, HFACS, AHP | Tertiary article |

| Zhang et al. [16] | A probabilistic model of human error assessment for autonomous cargo ships focusing on human–autonomy collaboration | 2020 | Safety Science | Journal article | THERP-BN model, | Primary article |

| Erdem et al. [101] | An interval type-2 fuzzy SLIM approach to predict human error in maritime transportation | 2021 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | SLIM-IT2FS model, | Primary article |

| Graziano et al. [102] | Classification of human errors in grounding and collision accidents using the TRACEr taxonomy | 2016 | Safety Science | Journal article | Technique for the Retrospective and Predictive Analysis | Primary article |

| Kandemir et al. [60] | Determining the error producing conditions in marine engineering maintenance and operations through HFACS-MMO | 2021 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | HFACS-MMO model | Primary article |

| Islam et al. [103] | Development of a monograph for human error likelihood assessment in marine operations | 2017 | Safety Science | Journal article | SLIM model | Primary article |

| Shuen-Tai Ung [104] | Evaluation of human error contribution to oil tanker collision using fault tree analysis and modified fuzzy Bayesian Network based CREAM | 2019 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | FTA-BN-CREAM model | Primary article |

| Rabiul Islam [105] | Human error assessment during maintenance operations of marine systems -What are the effective environmental factors? | 2018 | Safety Science | Journal article | Data analysis | Primary article |

| Shuen-Tai Ung [58] | Human error assessment of oil tanker grounding | 2018 | Safety Science | Journal article | FTA-CREAM model | Primary article |

| Li et al. [55] | Impact analysis of external factors on human errors using the ARBN method based on small-sample ship collision records | 2021 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | ARBN model | Primary article |

| Akyuz et al. [57] | Prediction of human error probabilities in a critical marine engineering operation on-board chemical tanker ship: The case of ship bunkering | 2018 | Safety Science | Journal article | SOHRA model | Primary article |

| Emre Akyuz [106] | Quantification of human error probability towards the gas inerting process onboard crude oil tankers | 2015 | Safety Science | Journal article | CREAM model | Tertiary article |

| Krzysztof Wrobel [11] | Searching for the origins of the myth: 80% human error impact on maritime safety | 2021 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | literature review | Primary article |

| Jean Christophe Le Coze [107] | The ‘new view’ of human error. Origins, ambiguities, successes and critiques | 2022 | Safety Science | Journal article | literature review | Primary article |

| Mehmet Kaptan [108] | The effect of nonconformities encountered in the use of technology on the occurrence of collision, contact and grounding accidents | 2021 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | HFACS-BN model, accident reports | Primary article |

| Akyuz et al. [109] | Utilization of cognitive map in modelling human error in marine accident analysis and prevention | 2014 | Safety Science | Journal article | HFACS–CM model | Quaternary article |

| Read et al. [13] | State of science: evolving perspectives on ‘human error’ | 2021 | Ergonomics | Journal article | literature review | Secondary article |

| Gabriel A. Cornejo [110] | Human Errors in Data Breaches: An Exploratory Configurational Analysis | 2021 | Nova Southeastern University | Dissertation | Multi-methods | Primary article |

| Peter J. Zohorsky [111] | Human error in commercial fishing vessel accidents: an investigation using the human factors analysis and classification system | 2020 | Old Dominion University | Dissertation | Multi-methods | Primary article |

Appendix D. List of Articles with “Human Reliability Analysis” in the Title

| Ref. | Title | Year | Journal | Doc. Type | Res. Method | Remarks |

| Yang et al. [112] | A modified CREAM to human reliability quantification in marine engineering | 2013 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | CREAM model | Primary article |

| Groth et al. [62] | A data-informed PIF hierarchy for model-based Human Reliability Analysis | 2012 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | PIF hierarchy method | Primary article |

| Zhou et al. [63] | A fuzzy and Bayesian network CREAM model for human reliability analysis -The case of tanker shipping | 2018 | Safety Science | Journal article | BN-CREAM model | Primary article |

| Akyuz et al. [113] | A methodological extension to human reliability analysis for cargo tank cleaning operation on board chemical tanker ships | 2015 | Safety Science | Journal article | AHP-HEART model | Primary article |

| Zhou et al. [68] | An enhanced CREAM with stakeholder-graded protocols for tanker shipping safety application | 2017 | Safety Science | Journal article | AHP-CREAM model | Primary article |

| Ahn et al. [114] | Application of a CREAM based framework to assess human reliability in emergency response to engine room fires on ships | 2020 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | CREAM model | Primary article |

| Martins et al. [115] | Application of Bayesian Belief networks to the human reliability analysis of an oil tanker operation focusing on collision accidents | 2013 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | BBN model | Primary article |

| Editorial [61] | Foundations and novel domains for Human Reliability Analysis | 2020 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | State-of-the-art survey | Primary article |

| Ladan et al. [17] | Human reliability analysis-Taxonomy and praxes of human entropy boundary conditions for marine and offshore applications | 2012 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | HENT model | Quaternay article |

| Shuen-Tai Ung. [116] | A weighted CREAM model for maritime human reliability analysis | 2015 | Safety Science | Journal article | fuzzy CREAM model | Primary article |

| Wu et al. [117] | An Evidential Reasoning-Based CREAM to Human Reliability Analysis in Maritime Accident Process | 2017 | Risk Analysis | Journal article | CREAM model | Primary article |

| Akyuz et al. [66] | Application of CREAM human reliability model to cargo loading process of LPG tankers | 2015 | Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries | Journal article | CREAM model | Secondary article |

| Kandemir et al. [65] | Application of human reliability analysis to repair & maintenance operations onboard ships: The case of HFO purifier overhauling | 2019 | Applied Ocean Research | Journal article | SOHRA model | Secondary article |

| Islam et al. [118] | Development of a human reliability assessment technique for the maintenance procedures of marine and offshore operations | 2017 | Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries | Journal article | Modified HEART model | Secondary article |

| Yang et al. [119] | Use of evidential reasoning for eliciting bayesian subjective probabilities in human reliability analysis: A maritime case | 2019 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | ER-BN-CREAM model | Primary article |

| Abaei et al. [19] | A dynamic human reliability model for marine and offshore operations in harsh environments | 2019 | Ocean Engineering | Journal article | DBN Model model | Primary article |

| Bicen et al. [64] | A Human Reliability Analysis to Crankshaft Overhauling in Dry Docking of a General Cargo Ship | 2020 | Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment | Journal article | SOHRA approach | Secondary article |

| Kandemir et al. [120] | A human reliability assessment of marine auxiliary machinery maintenance operations under ship PMS and maintenance 4.0 concepts | 2020 | Cognition, Technology & Work | Journal article | Maintenance 4.0approach | Secondary article |

| Akyuz et al. [67] | A modified human reliability analysis for cargo operation in single point mooring (SPM) off-shore units | 2016 | Applied Ocean Research | Journal article | Modified HEART model | Primary article |

| Zhang et al. [121] | A modified human reliability analysis method for the estimation of human error probability in the offloading operations at oil terminals | 2020 | Process safety progress | Journal article | Modified fuzzy CREAM model | Secondary article |

| Wang et al. [122] | Reliability analyses of k-out-of-n: F capability-balanced systems in a multi-source shock environment | 2022 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | k-out-of-n: F capability-balanced system | Primary article |

| Wang et al. [123] | Reliability evaluations for a multi-state k-out-of-n: F system with m subsystems supported by multiple protective devices | 2022 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | k-out-of-n: F capability-balanced system | Primary article |

| Zhao et al. [124] | Joint optimization of mission abort and protective device selection policies for multistate systems | 2022 | Risk Analysis | Journal article | condition based mission abort policy | Primary article |

| Zhao et al. [125] | Joint optimization of mission aborts and allocation of standby components considering mission loss | 2022 | Reliability Engineering and System Safety | Journal article | Dynamic allocation policy | Primary article |

| Wu et al. [126] | A Sequential Barrier-based Model to Evaluate Human Reliability in Maritime Accident Process | 2015 | - | Conference paper | Sequential safety-barrier-based model | Primary article |

| Mitomo et al. [127] | Common Performance Condition for Marine Accident -Experimental approach | 2012 | - | Conference paper | Simulation | Primary article |

| Mitomo et al. [128] | Development of a Method for Marine Accident Analysis with Concepts of PRA | 2014 | - | Conference paper | Analytical approach | Primary article |

| Hu et al. [78] | Towards a HFACS and Bayesian Belief Network model to Analysis Collision Risk Causal on Ship Pilotage Process | 2021 | - | Conference paper | HFACS-BBN model | Primary article |

| Atiyah et al. [129] | Marine Pilot’s Reliability Index (MPRI): Evaluation of marine pilot reliability in uncertain environments | 2019 | - | Conference paper | Delphi approach, AHP model | Primary article |

| Allal et al. [130] | Task Human Reliability Analysis for a Safe Operation of Autonomous Ship | 2017 | - | Conference paper | Event tree, THERP model | Primary article |

| Yoshimura et al. [131] | The Support for using the Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method (CREAM) for Marine Accident Investigation | 2015 | - | Conference paper | CREAM model | Primary article |

References

- IMO, Resolution A.850(20). Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.850(20).pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.947(23). Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/HumanElement/Documents/A947(23).pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.788(19). Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.788(19).pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.913(22). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/GoogleSearch/SearchPosts/Default.aspx?q=Resolution%20A.913(22) (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.1022(26). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/GoogleSearch/SearchPosts/Default.aspx?q=Resolution%20A.1022(26) (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.1071(28). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/GoogleSearch/SearchPosts/Default.aspx?q=Resolution%20A.1071(28) (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.1118(30). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/GoogleSearch/SearchPosts/Default.aspx?q=Resolution%20A.1118(30) (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- EMSA, 2021. Annual Overview of Marine Casualties and Incidents 2021. Available online: http://www.emsa.europa.eu/accident-investigation-publications/annual-overview.html (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Kaptan, M.; Sarıalioglu, S.; Ugurlu, O. The evolution of the HFACS method used in analysis of marine accidents: A review. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 86, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.P.E. The contribution of human factors to accidents in the offshore oil industry. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 1998, 61, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K. Searching for the origins of the myth: 80% human error impact on maritime safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 107942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HFES, 2022. What Is Human Factors and Ergonomics? Available online: https://www.hfes.org/About-HFES/What-is-Human-Factors-and-Ergonomics (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Read, G.J.M.; Shorrock, S.; Walker, G.H.; Salmon, P.M. State of science: Evolving perspectives on ‘human error’. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 1091–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y. A methodology to evaluate human factors contributed to maritime accident by mapping fuzzy FT into ANN based on HFACS. Ocean Eng. 2020, 197, 106892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMattia, D.G.; Khan, F.I.; Amyotte, P.R. Determination of human error probabilities for offshore platform musters. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2005, 18, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Yao, H.; Zhang, K. A probabilistic model of human error assessment for autonomous cargo ships focusing on human–autonomy collaboration. Saf. Sci. 2020, 130, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ladan, S.; Turan, O. Human reliability analysis—Taxonomy and praxes of human entropy boundary conditions for marine and offshore applications. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012, 98, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Wróbel, K.; Montewka, J.; Gil, M.; Wan, C.; Zhang, D. A framework to identify factors influencing navigational risk for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships. Ocean Eng. 2020, 202, 107188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaei, M.M.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Arzaghi, E.; Toroody, A.B. A dynamic human reliability model for marine and offshore operations in harsh environments. Ocean Eng. 2018, 173, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yip, T.L.; Yan, X.; Soares, C.G. Review of techniques and challenges of human and organizational factors analysis in maritime transportation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 219, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K.; Montewka, J.; Kujala, P. Towards the assessment of potential impact of unmanned vessels on maritime transportation safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 165, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO, 2022. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/HumanElement/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- IMO, Resolution A.849(20). Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.849(20).pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- The Nautical Institute, UK. Exploring the Human Element—The International Maritime Human Element Bulletin; The Nautical Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- IMO, MSC-MEPC.2/Circular.13. 2013. Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/HumanElement/Documents/MSC-MEPC.2-Circ.13%20-%20Guidelines%20For%20The%20Appliction%20Of%20The%20Human%20Element%20Analysing%20Process%20(Heap)%20To%20The%20Imo%20Ru...%20(Secretariat).pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Popa, L.V. The contribution of the human element in shipping companies. WLC 2016: World LUMEN Congress. Logos Univ. Ment. Educ. Nov. 2016, 15, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, V.R.; Santiago, I.B. The human element in shipping casualties as a process of risk homeostasis of the shipping business. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolo, F.; Gianfranco, F.; Luca, F.; Marco, M.; Andrea, M.; Francesco, M.; Vittorio, P.; Mattia, P.; Patrizia, S. Investigating the Role of the Human Element in Maritime Accidents using Semi-Supervised Hierarchical Methods. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 52, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallam, S.C.; Nazir, S.; Sharma, A. The human element in future Maritime Operations—Perceived impact of autonomous shipping. Ergonomics 2019, 63, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenjärvi, S. The Human Element and Autonomous Ships. Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2016, 10, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumler, R.; Arce, M.C.; Pazaver, A. Quantification of influence and interest at IMO in Maritime Safety and Human Element matters. Mar. Policy 2021, 133, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Pekcan, C.H. The Human Element in Shipping. EMOE 2017, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO, Resolution A.884(21). Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.884(21).pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- HSE Books London, UK. Reducing Error and Influencing Behaviour; HSE Books London: London, UK, 1999.

- Woodcock, B.; Au, Z. Human factors issues in the management of emergency response at high hazard installations. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2013, 26, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HFES, 2022. Available online: https://www.hfes.org/About-HFES/What-is-Human-Factors-and-Ergonomics#professional_societies (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Coraddu, A.; Oneto, L.; de Maya, B.N.; Kurt, R. Determining the most influential human factors in maritime accidents: A data-driven approach. Ocean Eng. 2020, 211, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıalioğlu, S.; Uğurlu, O.; Aydın, M.; Vardar, B.; Wang, J. A hybrid model for human-factor analysis of engine-room fires on ships: HFACS-PV&FFTA. Ocean Eng. 2020, 217, 107992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Uğurlu, O.; Wang, J.; Loughney, S. Application of the HFACS-PV approach for identification of human and organizational factors (HOFs) influencing marine accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 208, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, O.; Yıldız, S.; Loughney, S.; Wang, J. Modified human factor analysis and classification system for passenger vessel accidents (HFACS-PV). Ocean Eng. 2018, 161, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, C.; Lardjane, S.; Morel, G.; Clostermann, J.-P.; Langard, B. Human and organisational factors in maritime accidents: Analysis of collisions at sea using the HFACS. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 59, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-T.; Wall, A.; Davies, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Chou, Y.-H. A Human and Organisational Factors (HOFs) analysis method for marine casualties using HFACS-Maritime Accidents (HFACS-MA). Saf. Sci. 2013, 60, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Yip, T.L.; Fan, X.; Wu, B. Use of HFACS and Bayesian network for human and organizational factors analysis of ship collision accidents in the Yangtze River. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Yin, J.; Mustafa, F.S.; Farea, A.O.A. A data centered human factor analysis approach for hazardous cargo accidents in a port environment. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2021, 75, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Pei, Y.; Xia, Q. Research on human factors cause chain of ship accidents based on multidimensional association rules. Ocean Eng. 2020, 218, 107717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordon, J.R.; Mestre, J.M.; Walliser, J. Human factors in seafaring: The role of situation awareness. Saf. Sci. 2017, 93, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, B.N.; Khalid, H.; Kurt, R.E. Application of card-sorting approach to classify human factors of past maritime accidents. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 48, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Liu, Z.; Tian, X. A dynamic Bayesian networks modeling of human factors on offshore blowouts. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2013, 26, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiralis, P.; Ventikos, N.; Hamann, R.; Golyshev, P.; Teixeira, A. Incorporation of human factors into ship collision risk models focusing on human centred design aspects. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2016, 156, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, J.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Yang, Z.; Yan, X. Maritime accident prevention strategy formulation from a human factor perspective using Bayesian Networks and TOPSIS. Ocean Eng. 2020, 210, 107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder-Hinrichs, J.-U.; Hollnagel, E.; Baldauf, M.; Hofmann, S.; Kataria, A. Maritime human factors and IMO policy. Marit. Policy Manag. 2013, 40, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, S.; Kay, A.; Ryan, M.; Brazil, B.; Ward, M. Human factors & safety culture: Challenges & opportunities for the port environment. Saf. Sci. 2018, 125, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, D.K. A Guide to Reducing Human Errors, Improving Human Performance in the Chemical Industry; The Chemical Manufacturers’ Association, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M.; McCormick, E. Human Factors in Engineering and Design; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993; 704p. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-H. Human factors influencing the ship operator’s perceived risk in the last moment of collision encounter. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 203, 107078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Weng, J.; Hou, Z. Impact analysis of external factors on human errors using the ARBN method based on small-sample ship collision records. Ocean Eng. 2021, 236, 109533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, U.; Umut, Y.; Başar, E. Analysis of grounding accidents caused by human error. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2015, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E.; Celik, M.; Akgun, I.; Cicek, K. Prediction of human error probabilities in a critical marine engineering operation on-board chemical tanker ship: The case of ship bunkering. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, S.-T. Human error assessment of oil tanker grounding. Saf. Sci. 2018, 104, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, C.; Celik, M. Determining the error producing conditions in marine engineering

maintenance and operations through HFACS-MMO. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 206, 107308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] - Podofillini, L.; Mosleh, A. Foundations and novel domains for Human Reliability Analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 194, 106759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, K.; Mosleh, A. A data-informed PIF hierarchy for model-based Human Reliability Analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012, 108, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wong, Y.D.; Loh, H.S.; Yuen, K.F. A fuzzy and Bayesian network CREAM model for human reliability analysis—The case of tanker shipping. Saf. Sci. 2018, 105, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicen, S.; Kandemir, C.; Celik, M. A Human Reliability Analysis to Crankshaft Overhauling in Dry-Docking of a General Cargo Ship. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2020, 235, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, C.; Celik, M.; Akyuz, E.; Aydin, O. Application of human reliability analysis to repair & maintenance operations on-board ships: The case of HFO purifier overhauling. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 88, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E.; Celik, M. Application of CREAM human reliability model to cargo loading process of LPG tankers. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2015, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E.; Celik, E. A modified human reliability analysis for cargo operation in single point mooring (SPM) off-shore units. Appl. Ocean Res. 2016, 58, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wong, Y.D.; Xu, H.; Van Thai, V.; Loh, H.S.; Yuen, K.F. An enhanced CREAM with stakeholder-graded protocols for tanker shipping safety application. Saf. Sci. 2017, 95, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corović, B.; Djurović, P. Research of marine accidents through the prism of human factors. Promet Traffic Transp. 2013, 25, 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlström, M.; Hakulinen, J.; Karvonen, H.; Lindborg, I. Human factors challenges in unmanned ship operations-insights from other domains.6th Interna-tional Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE 2015) and the Affiliated Conferences, AHFE 2015. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praetorius, G.; Kataria, A.; Petersen, E.S.; Schröder-Hinrichs, J.U.; Baldauf, M.; Kähler, N. Increased awareness for maritime human factors through e-learning in crew-centered design.6th In-ternational Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE 2015) and the Affiliated Conferences, AHFE 2015. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 2824–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Ü.; Güneroğlu, A. Strategic approach model for investigating the cause of maritime accidents. Promet Traffic Transp. 2015, 27, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galieriková, A. The human factor and maritime safety. In Proceedings of the 13th International Scientific Conference on Sustainable, Modern and Safe Transport (TRANSCOM 2019), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, 29–31 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Dai, T.T. Causing mechanism analysis of human factors in the marine safety management based on the entropy. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Hong Kong, China, 10–13 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.T.; Chen, W.J.; Fang, Q.G.; Hu, S.P. HFACS model based data mining of human factors-a marine study. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Macao, China, 7–10 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Masumi, N.; Takashi, M.; Uchida, M. Relationship between characteristics of human factors based on marine accident analysis. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 6–9 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, T.T.; Wang, H.Y. The human factors analysis of marine accidents based on goal structure notion. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Singapore, 6–9 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xi, Y. Towards a HFACS and Bayesian Belief Network model to analysis collision risk causal on ship pilotage process. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety, Wuhan, China, 22–24 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hannu, K.; Jussi, M. Human factors issues in maritime autonomous surface ship systems development. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (ICMASS 2018), Busan, Korea, 8–9 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin, C. Human Factors and Maritime Safety. J. Navig. 2011, 64, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Xi, Y.; Hu, S.; Tang, L. Dynamics Simulation of the Risk Coupling Effect between Maritime Pilotage Human Factors under the HFACS Framework. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, U.; Başar, E.; Uğurlu, Ö. Assessment of collisions and grounding accidents with human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS) and statistical methods. Saf. Sci. 2019, 119, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasegaran, D.; Ghazilla, R.; Rich, K. Human factors engineering integration in the offshore O&G industry: A review of current state of practice. Saf. Sci. 2020, 125, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X. Incorporation of human factors into maritime accident analysis using a data-driven Bayesian network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 203, 107070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhuang, H.; Xu, D. Structured survey of human factor-related maritime accident research. Ocean Eng. 2021, 237, 109561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Goerlandt, F.; Yan, X.; Kujala, P. Use of HFACS and fault tree model for collision risk factors analysis of icebreaker assistance in ice-covered waters. Saf. Sci. 2018, 111, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soner, O.; Asan, U.; Celik, M. Use of HFACS–FCM in fire prevention modelling on board ships. Saf. Sci. 2015, 77, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallam, S.C.; Lundh, M.; MacKinnon, S.N. Integrating Human Factors & Ergonomics in large-scale engineering projects: Investigating a practical approach for ship design. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 50, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumawas, V. Human Factors in Ship Design and operation: Experiential Learning; Norwegian University of Science and Technology: Trondhjems, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Casarosa, L. The Integration of Human Factors, Operability and Personnel Movement Simulation into the Preliminary Design of Ships Utilising the Design Building Block Approach; University of London: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.H.; Hu, T. Brittle relationship analysis of human error accident of warship technology supportability system based on set pair analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Industrial Technology and Management, Oxford, UK, 7–9 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jasman, W.P.; Saragih, S.; Suwarn; Hasibuan, A. Analysis of damage to ship MT. Delta Victory due to human error and electricity with the Shel method. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electrical, Telecommunication and Computer Engineering (ELTICOM), Medan, Indonesia, 3 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F.I. Determination of Human Error Probabilities for the Maintenance Operations of Marine Engines. J. Ship Prod. Des. 2016, 32, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E. Quantitative human error assessment during abandon ship procedures in maritime transportation. Ocean Eng. 2016, 120, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Yang, Z.; Fang, Q.; Chen, W.; Wang, J. A new hybrid approach to human error probability quantification–applications in maritime operations. Ocean Eng. 2017, 138, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Liu, S. A hybrid evaluation method for human error probability by using extended DEMATEL with Z-numbers: A case of cargo loading operation. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 84, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Varela, Z.; Boullosa-Falces, D.; Larrabe-Barrena, J.L.; Gomez-Solaeche, M.A. Determining the likelihood of incidents caused by human error during dynamic positioning drilling operations. J. Navig. 2021, 74, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, S.; Khakzad, N.; Hosseini, S.M. A data-based comparison of BN-HRA models in assessing human error probability: An offshore evacuation case study. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 202, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Song, G.; Chen, G.; Zhu, J. A novel methodology to analyze accident path in deepwater drilling operation considering uncertain information. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 205, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E.; Celik, M.; Cebi, S. A phase of comprehensive research to determine marine-specific EPC values in human error assessment and reduction technique. Saf. Sci. 2016, 87, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, P.; Akyuz, E. An interval type-2 fuzzy SLIM approach to predict human error in maritime transportation. Ocean Eng. 2021, 232, 109161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, A.; Teixeira, A.; Soares, C.G. Classification of human errors in grounding and collision accidents using the TRACEr taxonomy. Saf. Sci. 2016, 86, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Yu, H.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F. Development of a monograph for human error likelihood assessment in marine operations. Saf. Sci. 2017, 91, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, S.-T. Evaluation of human error contribution to oil tanker collision using fault tree analysis and modified fuzzy Bayesian Network based CREAM. Ocean Eng. 2019, 179, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Khan, F.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V. Human error assessment during maintenance operations of marine systems–What are the effective environmental factors? Saf. Sci. 2018, 107, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E. Quantification of human error probability towards the gas inerting process on-board crude oil tankers. Saf. Sci. 2015, 80, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coze, J.C. The ‘new view’ of human error. Origins, ambiguities, successes and critiques. Saf. Sci. 2022, 154, 105853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, M.; Uğurlu, Ö.; Wang, J. The effect of nonconformities encountered in the use of technology on the occurrence of collision, contact and grounding accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 215, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E.; Celik, M. Utilisation of cognitive map in modelling human error in marine accident analysis and prevention. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.C. Human Errors in Data Breaches: An Exploratory Configurational Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Nova Southeastern University (USA), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J.Z. Human Error in Commercial Fishing Vessel Accidents: An Investigation Using the Human Factors Analysis and Classi-Fication System. Ph.D. Thesis, Old Dominion University (USA), Norfolk, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Bonsall, S.; Wall, A.; Wang, J.; Usman, M. A modified CREAM to human reliability quantification in marine engineering. Ocean Eng. 2012, 58, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, E.; Celik, M. A methodological extension to human reliability analysis for cargo tank cleaning operation on board chemical tanker ships. Saf. Sci. 2015, 75, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.I.; Kurt, R.E. Application of a CREAM based framework to assess human reliability in emergency response to engine room fires on ships. Ocean Eng. 2020, 216, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.R.; Maturana, M.C. Application of Bayesian Belief networks to the human reliability analysis of an oil tanker operation focusing on collision accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012, 110, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, S.-T. A weighted CREAM model for maritime human reliability analysis. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Soares, C.G. An evidential reasoning-based CREAM to human reliability analysis in maritime accident process. Risk. Anal. 2017, 37, 1936–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F. Development of a human reliability assessment technique for the maintenance procedures of marine and offshore operations. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2017, 50, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Abujaafar, K.M.; Qu, Z.; Wang, J.; Nazir, S.; Wan, C. Use of evidential reasoning for eliciting bayesian subjective probabilities in human reliability analysis: A maritime case. Ocean Eng. 2019, 186, 106095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, C.; Celik, M. A human reliability assessment of marine auxiliary machinery maintenance operations under ship PMS and maintenance 4.0 concepts. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2019, 22, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tan, H.; Afzal, W. A modified human reliability analysis method for the estimation of human error probability in the offloading operations at oil terminals. Process. Saf. Prog. 2020, 40, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ning, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J. Reliability analyses of k-out-of-n: F capability-balanced systems in a multi-source shock environment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 227, 108733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ning, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J. Reliability evaluations for a multi-state k-out-of-n: F system with m subsystems supported by multiple protective devices. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chai, X.; Sun, J.; Qiu, Q. Joint optimization of mission abort and protective device selection policies for multistate systems. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 2823–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dai, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Wu, Y. Joint optimization of mission aborts and allocation of standby components considering mission loss. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 225, 108612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Soares, C.G.; Zhan, D.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X. A sequential barrier-based model to evaluate human reliability in maritime accident process. In Proceedings of the The 3rd International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety, Wuhan, China, 25–28 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nobuo, M.; Kenjiro, H.; Yoshimura, K.; Nishizaki, C.; Takemoto, T. Common performance condition for marine accident-experimental approach. In Proceedings of the 2012 Fifth International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology, Himeji, Japan, 5–7 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nobuo, M.; Chihiro, N.; Kenji, N. Development of a method for marine accident analysis with concepts of PRA. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Atiyah, A.; Christos, K.; Farhan, S.; Zaili, Y. Marine Pilot’s Reliability Index (MPRI): Evaluation of marine pilot reliability in uncertain envi-ronments. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety, Liverpool, UK, 14–17 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmoula, A.A.; Khalifa, M.; Mohammed, Q.; Mohamed, Y. Task human reliability analysis for a safe operation of autonomous Ship. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on System Reliability and Safety, Milan, Italy, 20–22 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, K.J.; Takemoto, T. The support for using the Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method (CREAM) for marine accident investigation. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV), Fukuoka, Japan, 15–18 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Literature | Number of Documents |

|---|---|

| Primary | 40 |

| Secondary | 61 |

| Tertiary | 7 |

| Quaternary | 3 |

| Ref. | Definitions |

|---|---|

| IMO Resolutions A.884(21) [33] | Human factors which contribute to marine casualties and incidents may be broadly defined as the acts or omissions, intentional or otherwise, which adversely affect the proper functioning of a particular system, or the successful performance of a particular task. |

| HSE [34] | Human factors refer to environmental, organizational and job factors, system design, task attributes and human characteristics that influence behavior and affect health and safety. |

| B. Woodcock [35] | Human factor is the discipline that seeks to understand the contribution of the human operator within the system and to influence design and operation accordingly. |

| IEA [36] | Human factor is the scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data and methods to design in order to optimize human well-being and overall system performance. |

| Category | Number of Documents |

|---|---|

| Journal article | 30 |

| Conference paper | 11 |

| Dissertation | 2 |

| Ref. | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Lorenzo, D.K. [53] | Any human action, or lack thereof, that exceeds or fails to achieve some limit of acceptability, where limits of human performance are defined by the system. |

| Sanders et al. [54] | Human error is an inappropriate or unacceptable human decision or action that degrades efficiency, safety, or system performance. |

| IMO resolutions A. 884(21) [33] | Human error is a departure from acceptable or desirable practice on the part of an individual or group of individuals that can result in unacceptable or undesirable results. |

| Do-Hoon Kim [55] | Human error is defined as the failure to perform a prescribed task or performing a prohibited activity, with consequences that can result in serious injury and property loss, as well as near-miss incidents. |

| DiMattia et al. [15] | Human error is treated as a natural consequence arising from a discontinuity between human capabilities and system demands. |

| Read et al. [13] | Human error is a non-observable construct, used to make causal inferences, without clarity on the mechanism behind causation. |

| Gordon, RPE [10] | Human error refers to acts which are judged by somebody to deviate from some kind of reference act. |

| Category | Number of Documents |

|---|---|

| Journal article | 26 |

| Conference paper | 3 |

| Dissertation | 2 |

| Category | Number of Documents |

|---|---|

| Journal article | 24 |

| Conference paper | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.F.; Shi, G.Y.; Liu, Z.J. Unraveling the Usage Characteristics of Human Element, Human Factor, and Human Error in Maritime Safety. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13052850

Ma XF, Shi GY, Liu ZJ. Unraveling the Usage Characteristics of Human Element, Human Factor, and Human Error in Maritime Safety. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(5):2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13052850

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xiao Fei, Guo You Shi, and Zheng Jiang Liu. 2023. "Unraveling the Usage Characteristics of Human Element, Human Factor, and Human Error in Maritime Safety" Applied Sciences 13, no. 5: 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13052850

APA StyleMa, X. F., Shi, G. Y., & Liu, Z. J. (2023). Unraveling the Usage Characteristics of Human Element, Human Factor, and Human Error in Maritime Safety. Applied Sciences, 13(5), 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13052850