A Case Study to Explore a UDL Evaluation Framework Based on MOOCs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. UDL as an Evaluation Framework for MOOCs

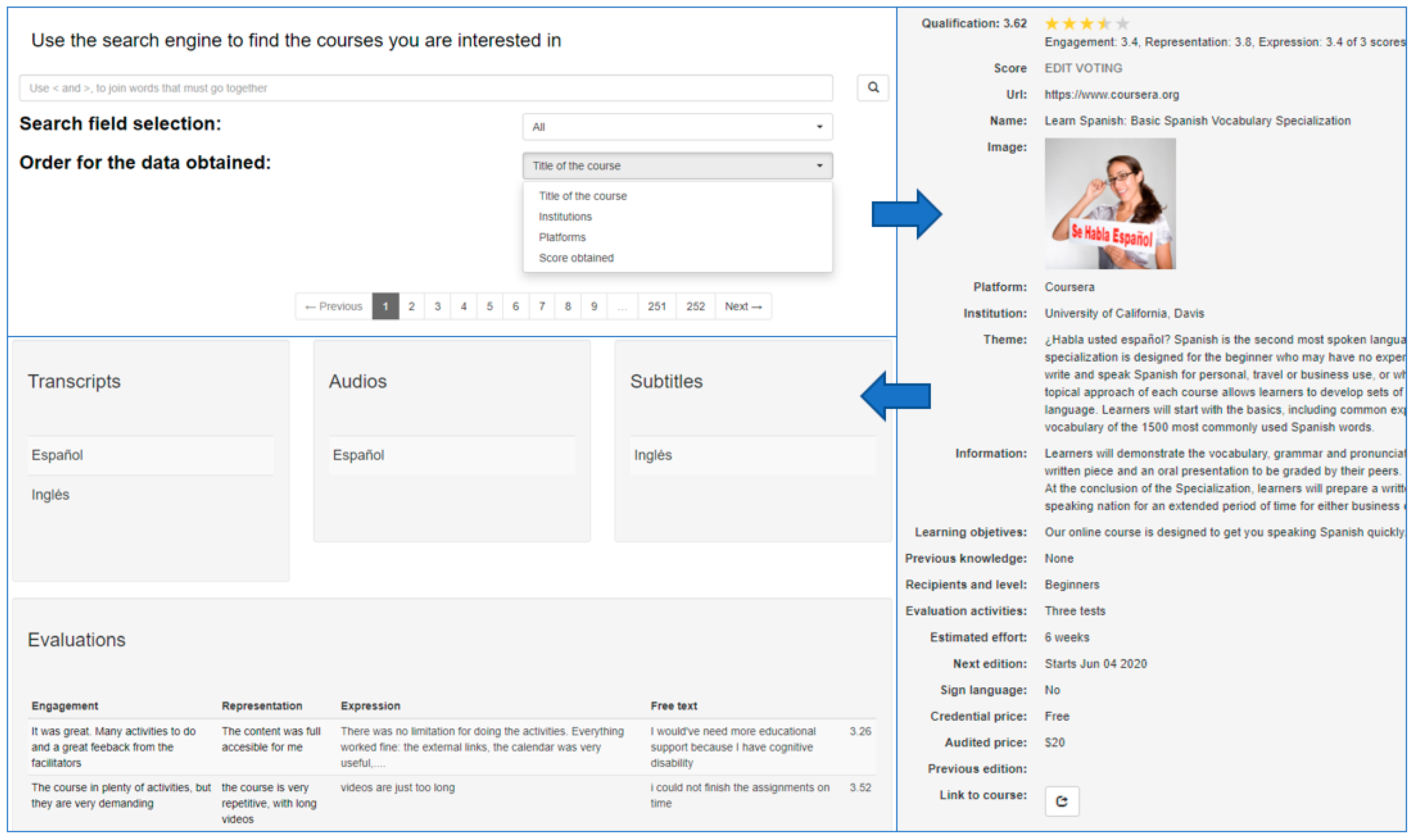

2.2. YourMOOC4all

3. Methodology

3.1. University Course and Sample

3.2. Objectives and Research Questions (RQs)

- 1.

- RQ1. To what extent did untrained raters agree when using the UDL evaluation framework?

- 2.

- RQ2. What are the perceptions of UDL as an evaluation framework for untrained raters?

3.3. Methods

- The Likert and open questions existing in YourMOOC4all to assess a MOOC using the UDL framework (quantitative and qualitative).

- A new set of open questions included in the exercise script (qualitative).

4. Results

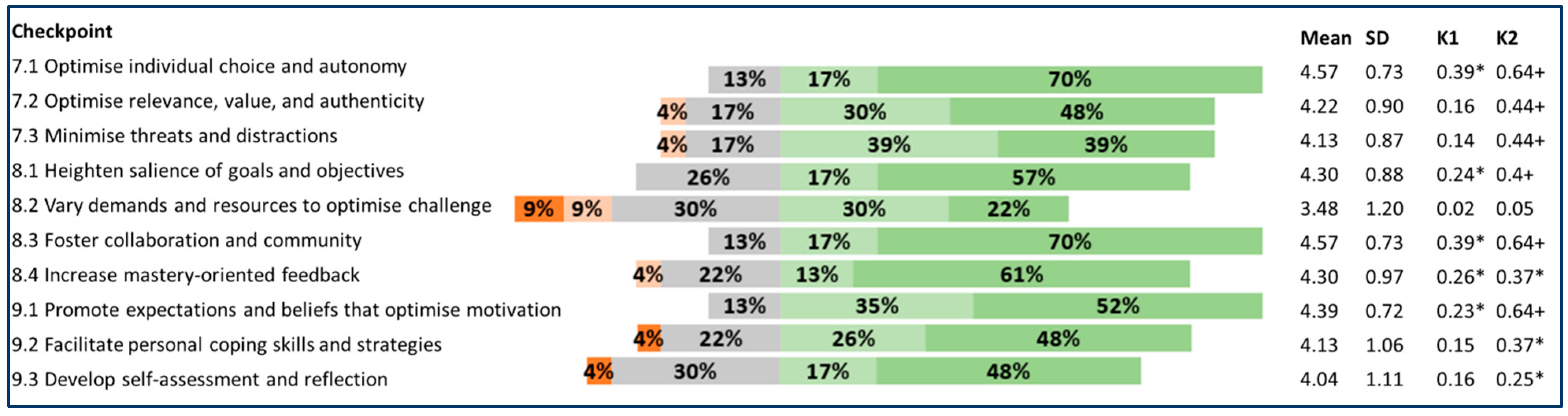

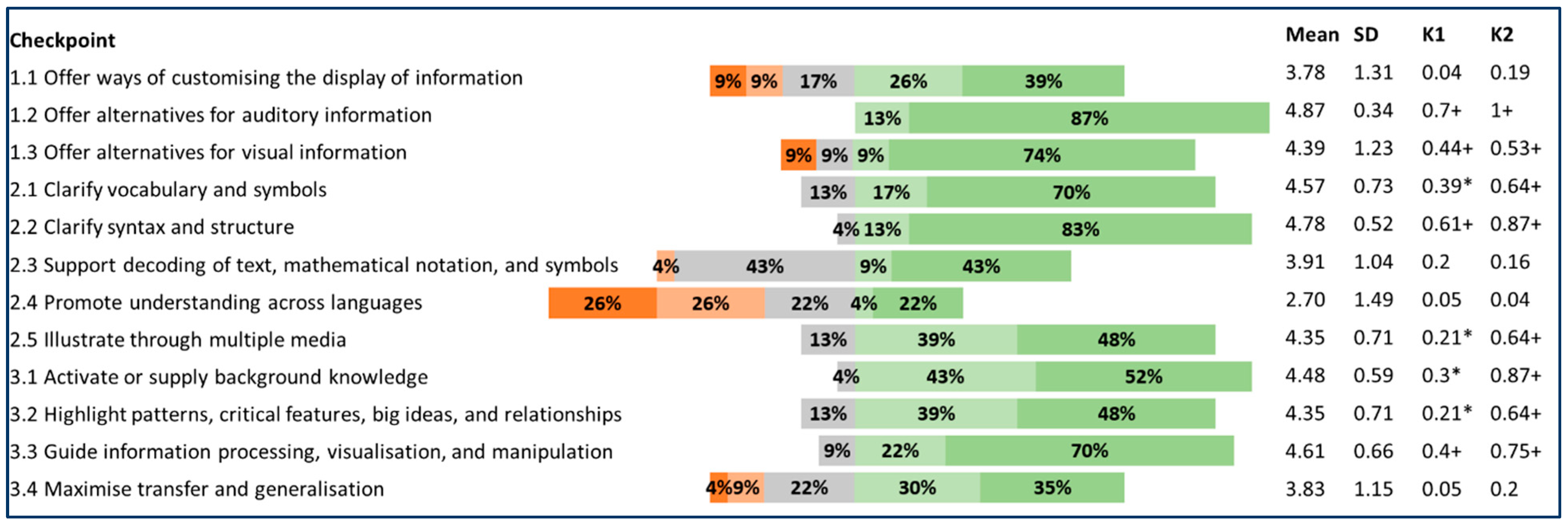

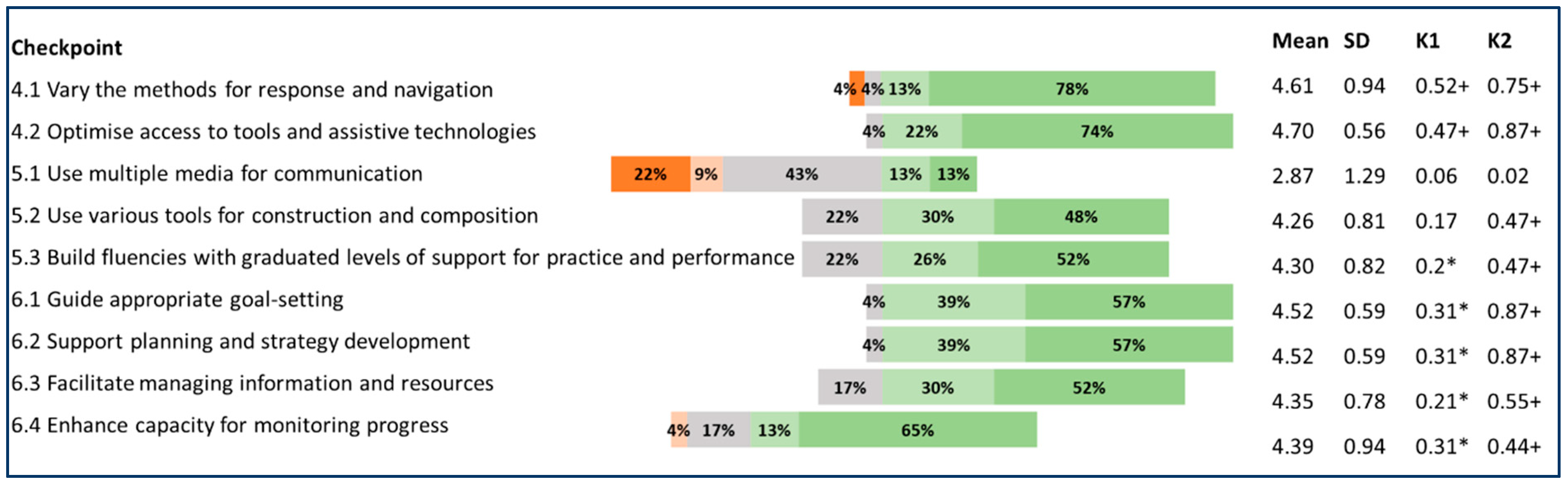

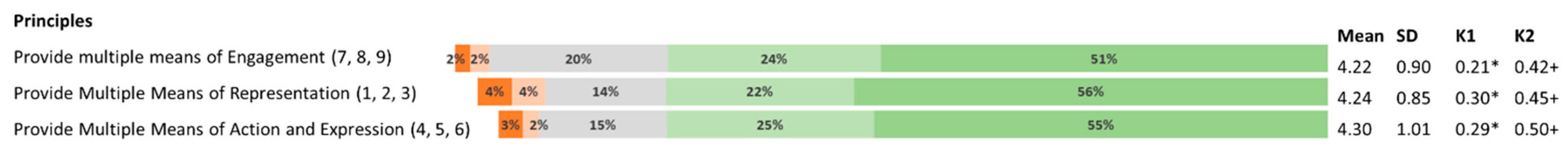

4.1. RQ1. To What Extent Did Untrained Raters Agree When Using the UDL Evaluation Framework?

There is a forum where you can contact your classmates and thus release stress and continue learning thanks to their help. The tests contain great feedback on what was taught, but do not identify its level of difficulty. As a help, there is only one glossary, with certain terms and the forum for the “team” to answer your questions.(ST8)

The course is designed to effectively motivate the student. Its structure does not only seek purely theoretical content but plays with various options to achieve a key motivation so that students can develop their activities, ask their questions and progress in the content in an even fun way.(ST7)

I think that the representation of contents throughout the course is done in a good way, with the information provided in different formats and styles to allow everybody access to it.(ST20)

The content seems to me to be presented concisely. At all times you see the content index, which lets you know where you are going and not disconnect from the conceptual map of the course. The “weak” points of the MOOC are, for example, that it does not allow for modification of the visualisation of the content.(ST23)

According to the scope of the expression in the MOOC, the only point I find regarding the proposed evaluation is the non-existence of the possibility of communication through social networks (or at least I have not been able to find it anywhere in it).(ST27)

I found the course progress screen very interesting; it is very useful since it allows you to better control the time you have to finish it.(ST 6)

4.2. RQ2. What Are the Perceptions of UDL as an Evaluation Framework for Untrained Raters?

UDL optimises learning so that in a group where we find students of different levels and abilities, we can teach everyone equally without excluding them. Facilitates access to study material, offering access in more than one format. In this way, it also promotes motivation among students and their participation.(ST13)

There may always be a student who cannot use the created product; therefore, it is necessary to design strategies and curricula that are inclusive for as many students as possible. Despite this, some students will need individualised support and attention. And despite everything, the main disadvantage that UDL brings is the large investment that must be made in educational centres and the little interest on the part of public and private institutions to carry it out.(ST9)

WCAG 2.1 are more oriented to the correction based on the staging of the content, and to the variety of tools and the good use of them, without presenting errors in their implementation, to facilitate user access. UDL is a methodology that values more conceptually the mechanisms that promote learning and make it more open to a greater number of people.(ST18)

The checkpoints where it is assessed whether the proposed activities agree with what it is desired to learn are difficult to assess since it depends on each of the students. It is the same case of the level of difficulty of the MOOC activities, the feedback in the tests and the existence of questions that help reflection.(ST14)

The checklists about discussing with students what you want to learn are redundant. In the case of the existence of a social network or external tool, the MOOC already has enough tools to be able to work with it.(ST7)

The different questions about the language could be unified since they are redundant. The questions about which tools are used within the MOOC are also repetitive. Finally, a couple of times we are asked about the content, formats, and structures of the MOOC.(ST8)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Provide Multiple Means of Engagement | Provide Multiple Means of Representation | Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression |

|---|---|---|

Provide options for Recruiting Interest (7)

| Provide options for Perception (1)

| Provide options for Physical Action (4)

|

Provide options for Sustaining Effort & Persistence (8)

| Provide options for Language & Symbols (2)

| Provide options for Expression & Communication (5)

|

Provide options for Self-Regulation (9)

| Provide options for Comprehension (3)

| Provide options for Executive Functions (6)

|

References

- Iniesto, F.; Tabuenca, B.; Rodrigo, C.; Tovar, E. Challenges to achieving a more inclusive and sustainable open education. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Benckendorff, P.; Gannaway, D. Learner engagement in MOOCs: Scale development and validation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 1, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, A.G.; Hernández, P.G.; López, C.M. La atención a la diversidad en los MOOCs: Una propuesta metodológica. Educ. XX1 2017, 20, 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Iniesto, F.; Rodrigo, C. YourMOOC4all: A recommender system for MOOCs based on collaborative filtering implementing UDL. In European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 746–750. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H.; Gordon, D.T. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice; CAST Professional Publishing: Lynnfield, MO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronseth, S.; Dalton, E.; Khanna, R.; Alvarez, B.; Iglesias, I.; Vergara, P.; Ingle, J.C.; Pacheco-Guffrey, H.; Bauder, D.; Cooper, K. Inclusive Instructional Design and UDL Around the World. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 18 March 2019; pp. 2357–2359. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, S.; Novak, K. (Eds.) Transforming Higher Education Through Universal Design for Learning: An International Perspective; Routledge: London UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Griful-Freixenet, J.; Struyven, K.; Verstichele, M.; Andries, C. Higher education students with disabilities speaking out: Perceived barriers and opportunities of the Universal Design for Learning framework. Disabil. Soc. 2017, 32, 1627–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. Wakefield, MA. 2018. Available online: http://udlguidelines.cast.org (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Cook, S.C.; Rao, K. Systematically applying UDL to effective practices for students with learning disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2018, 41, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.H.; Meyer, A. The future is in the Margins: The Role of Technology and Disability in Educational Reform. In A Practical Reader in Universal Design for Learning; ERIC: Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, C.Y.; Sun, J.C.Y.; Liu, J.Y. Effects of flipped classrooms integrated with MOOCs and game-based learning on the learning motivation and outcomes of students from different backgrounds. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 27, 1028–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.; Karunanayaka, S.P.; Ariadurai, S.A.; Rajendra, J.C.N. Designing Continuing Professional Development MOOCs to promote the adoption of OER and OEP. Open Prax. 2018, 10, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S.R. Do MOOCs contribute to student equity and social inclusion? A systematic review 2014–2018. Comput. Educ. 2020, 145, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesto, F.; McAndrew, P.; Minocha, S.; Coughlan, T. Accessibility in MOOCs: The stakeholders’ perspectives. In Open World Learning: Research, Innovation and the Challenges of High-Quality Education; Rienties, B., Hampel, R., Scanlon, E., Whitelock, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brajnik, G.; Yesilada, Y.; Harper, S. Is accessibility conformance an elusive property? A study of validity and reliability of WCAG 2.0. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. TACCESS 2012, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tlili, A.; Nascimbeni, F.; Burgos, D.; Huang, R.; Chang, T.W.; Jemni, M.; Khribi, M.K. Accessibility within open educational resources and practices for disabled learners: A systematic literature review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.E.; Cohen, N.; Vue, G.; Ganley, P. Addressing learning disabilities with UDL and technology: Strategic reader. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2015, 38, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Ok, M.W.; Smith, S.J.; Evmenova, A.S.; Edyburn, D. Validation of the UDL reporting criteria with extant UDL research. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2020, 41, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAST. Top 5 UDL Tips for Fostering Expert Learners. 2017. Available online: http://castprofessionallearning.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/cast-5-expert-learners-1.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Handoko, E.; Gronseth, S.L.; McNeil, S.G.; Bonk, C.J.; Robin, B.R. Goal setting and MOOC completion: A study on the role of self-regulated learning in student performance in massive open online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniesto, F.; Hillaire, G. UDL and its implications in MOOC accessibility evaluation. In Open World Learning: Research, Innovation and the Challenges of High-Quality Education; Rienties, B., Hampel, R., Scanlon, E., Whitelock, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ascaso, A.; Letón-Molina, E. Materiales Digitales Accesibles. 2018. Available online: http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/view/bibliuned:EditorialUNED-aa-EDU-Arodriguez-0003 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Rodrigo, C.; Iniesto, F.; García-Serrano, A. Reflections on Instructional Design Guidelines From the MOOCification of Distance Education: A Case Study of a Course on Design for All. In UXD and UCD Approaches for Accessible Education; IGI Global: Hershey, USA, 2020; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, K.K.; Powers, S.R. Mixed methods. In The International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 1977, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, H. Thematic analysis. In Understanding Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology; SAGE: London, UK, 2008; pp. 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Durham, M.F.; Knight, J.K.; Couch, B.A. Measurement Instrument for Scientific Teaching (MIST): A tool to measure the frequencies of research-based teaching practices in undergraduate science courses. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, ar67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniesto, F.; Rodrigo, C.; Hillaire, G. Applying UDL Principles in an Inclusive Design Project Based on MOOCs Reviews; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.H.; Tsai, C.C. In-service teachers’ conceptions of mobile technology-integrated instruction: Tendency towards student-centered learning. Comput. Educ. 2021, 170, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poquet, O.; Dawson, S.; Dowell, N. How effective is your facilitation? Group-level analytics of MOOC forums. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–17 March 2017; pp. 208–217. [Google Scholar]

| YourMOOC4all Exercise | |

|---|---|

| (Task 1) Process (accompanied by screenshots in the script). (RQ1) |

|

| (Task 2) Questions to answer in the script. (RQ2) |

|

| Principles | Checkpoints |

|---|---|

| Provide multiple means of Engagement (7, 8, 9) | 8.2 Vary demands and resources to optimise challenge |

| Provide Multiple Means of Representation (1, 2, 3) | 1.1 Offer ways of customising the display of information 2.3 Support decoding of text, mathematical notation, and symbols 2.4 Promote understanding across languages 3.4 Maximise transfer and generalization |

| Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression (4, 5, 6) | 5.1 Use multiple media for communication |

| Question | Codes |

|---|---|

| Advantages and disadvantages (Q1) |

|

| Comparison (Q2) | Universal Design (4), Accessibility (3), Expectations and motivations (1), Usability (1), Personalisation (1) |

| Difficulty to evaluate (Q3) | Overlap between checkpoints (3), Communication (2), Learning design and assessment (2), Alternative formats (1), Personalisation (1), Self-regulation (1) |

| Redundancy (Q4) | Alternative formats (3), Communication (2), Learning design and assessment (2), Language (2) Personalisation (2), Time limit (1) |

| Principles | Checkpoints |

|---|---|

| Provide multiple means of Engagement (7, 8, 9) | 7.2 Optimise relevance, value, and authenticity 8.1 Heighten salience of goals and objectives 8.2 Vary demands and resources to optimise challenge 8.4 Increase mastery-oriented feedback 9.1 Promote expectations and beliefs that optimise motivation 9.2 Facilitate personal coping skills and strategies |

| Provide Multiple Means of Representation (1, 2, 3) | 1.1 Offer ways of customising the display of information 2.3 Support decoding of text, mathematical notation, and symbols 3.4 Maximise transfer and generalisation |

| Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression (4, 5, 6) | 5.3 Build fluencies with graduated levels of support for practice and performance 6.2 Support planning and strategy development |

| Group | Across Principles | Checkpoints | Description of Redundancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | No | 2.1 Clarify vocabulary and symbols 2.2 Clarify syntax and structure | The evaluation of the use of language regarding the existence of a glossary of terms (2.1) and maintaining the same terminology (2.2) |

| Group 2 | No | 6.2 Support planning and strategy development 6.4 Enhance capacity for monitoring progress | Monitoring progress and strategy development facilitating reflection (6.2) and progress (6.4), both in the quizzes |

| Group 3 | Yes | 1.2 Offer alternatives for auditory information 1.3 Offer alternatives for visual information 2.5 Illustrate through multiple media 5.1 Use multiple media for communication 5.2 Use various tools for construction and composition | Use of alternative formats. The inclusion of different questions formats such as captions and transcripts (1.2), audio descriptions (1.3), images, text, video, or graphics (2.5), the use of external tools (5.1), and external links (5.2) adds confusion |

| Group 4 | Yes | 4.1 Vary the methods for response and navigation 7.1 Optimise individual choice and autonomy | Time limit (4.1) is related to options for physical action, allowing extra time to achieve a task, (7.1) indicates options for recruiting interest allowing the needed time to participate in discussions |

| Group 5 | Yes | 5.3 Build fluencies with graduated levels of support for practice and performance 8.1 Heighten salience of goals and objectives 8.3 Foster collaboration and community 8.4 Increase mastery-oriented feedback | The interaction in the system and between peers for reflection. Including facilitators (5.3) space to formulate and share learning objectives (8.1), with other partners (8.3) and again facilitators (8.4) |

| Group 6 | Yes | 6.1 Guide appropriate goal setting 7.3 Minimise threats and distractions 9.2 Facilitate personal coping skills and strategies | Information about learning objectives, activities (6.1), the use of a calendar (7.3), and spaces to discuss difficulties encountered (9.2) |

| Checkpoints |

|---|

| 1.2 Offer alternatives for auditory information 1.3 Offer alternatives for visual information 2.4 Promote understanding across languages 2.5 Illustrate through multiple media 5.1 Use multiple media for communication 5.2 Use various tools for construction and composition |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iniesto, F.; Rodrigo, C.; Hillaire, G. A Case Study to Explore a UDL Evaluation Framework Based on MOOCs. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13010476

Iniesto F, Rodrigo C, Hillaire G. A Case Study to Explore a UDL Evaluation Framework Based on MOOCs. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(1):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13010476

Chicago/Turabian StyleIniesto, Francisco, Covadonga Rodrigo, and Garron Hillaire. 2023. "A Case Study to Explore a UDL Evaluation Framework Based on MOOCs" Applied Sciences 13, no. 1: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13010476

APA StyleIniesto, F., Rodrigo, C., & Hillaire, G. (2023). A Case Study to Explore a UDL Evaluation Framework Based on MOOCs. Applied Sciences, 13(1), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13010476