Altering the Supply of Shielding Gases to Fabricate Distinct Geometry in GMA Additive Manufacturing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Materials

1.2. Methods

2. Results and Discussion

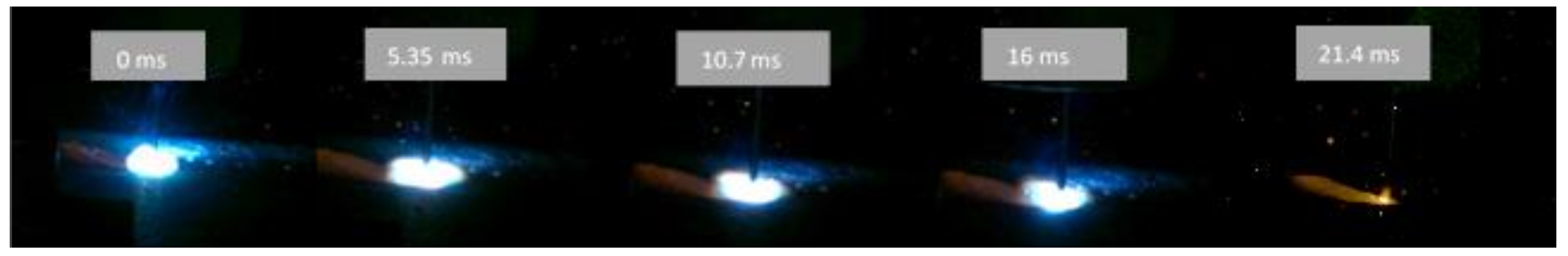

2.1. Arc Characteristics

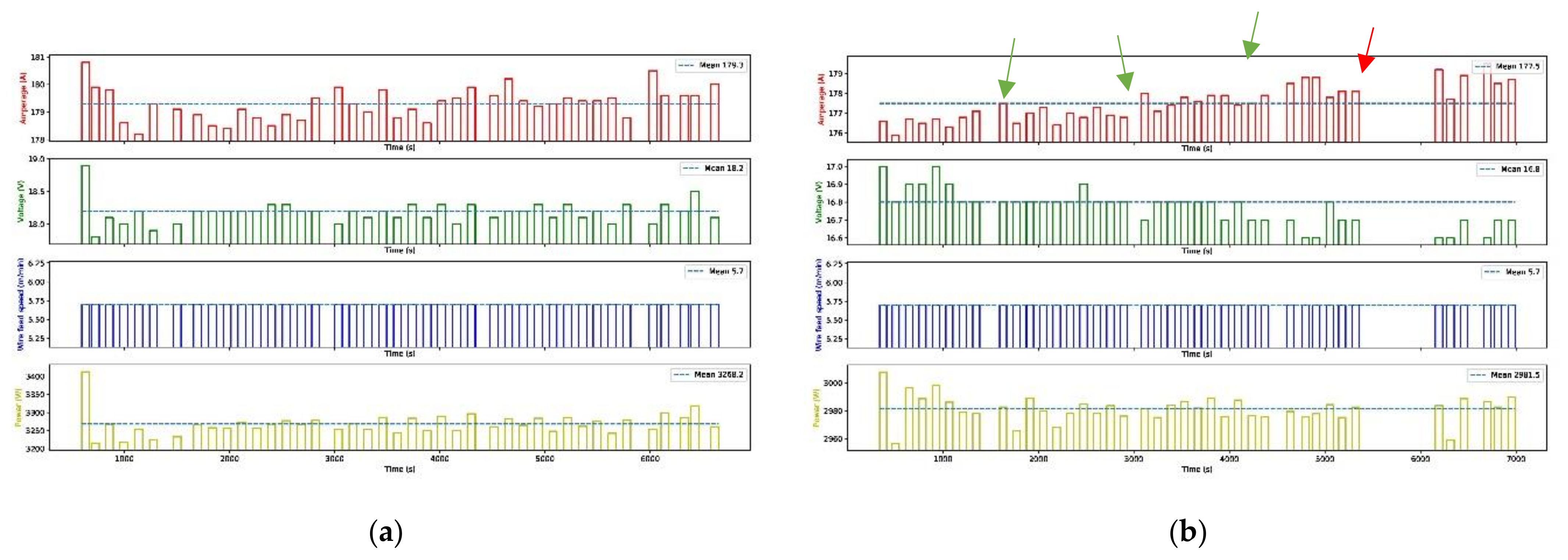

2.2. AM Deposition Parameters

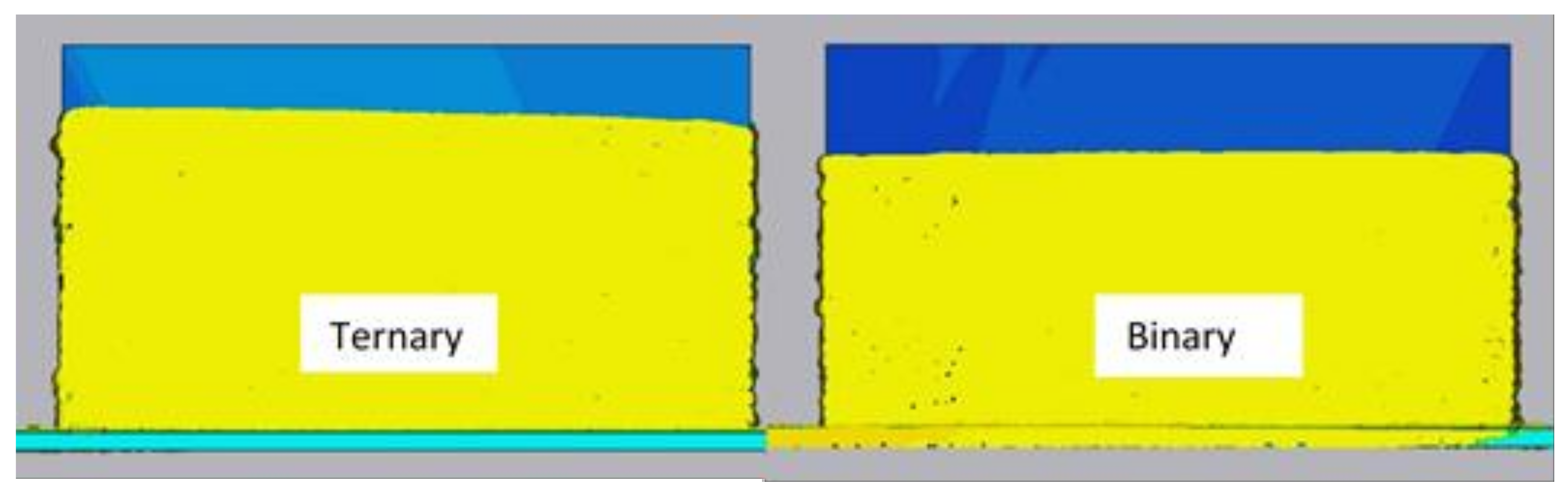

2.3. Dimensional Accuracy

2.4. Oxygen Content

- (1)

- The oxygen content remains the same in the molten and solid states.

- (2)

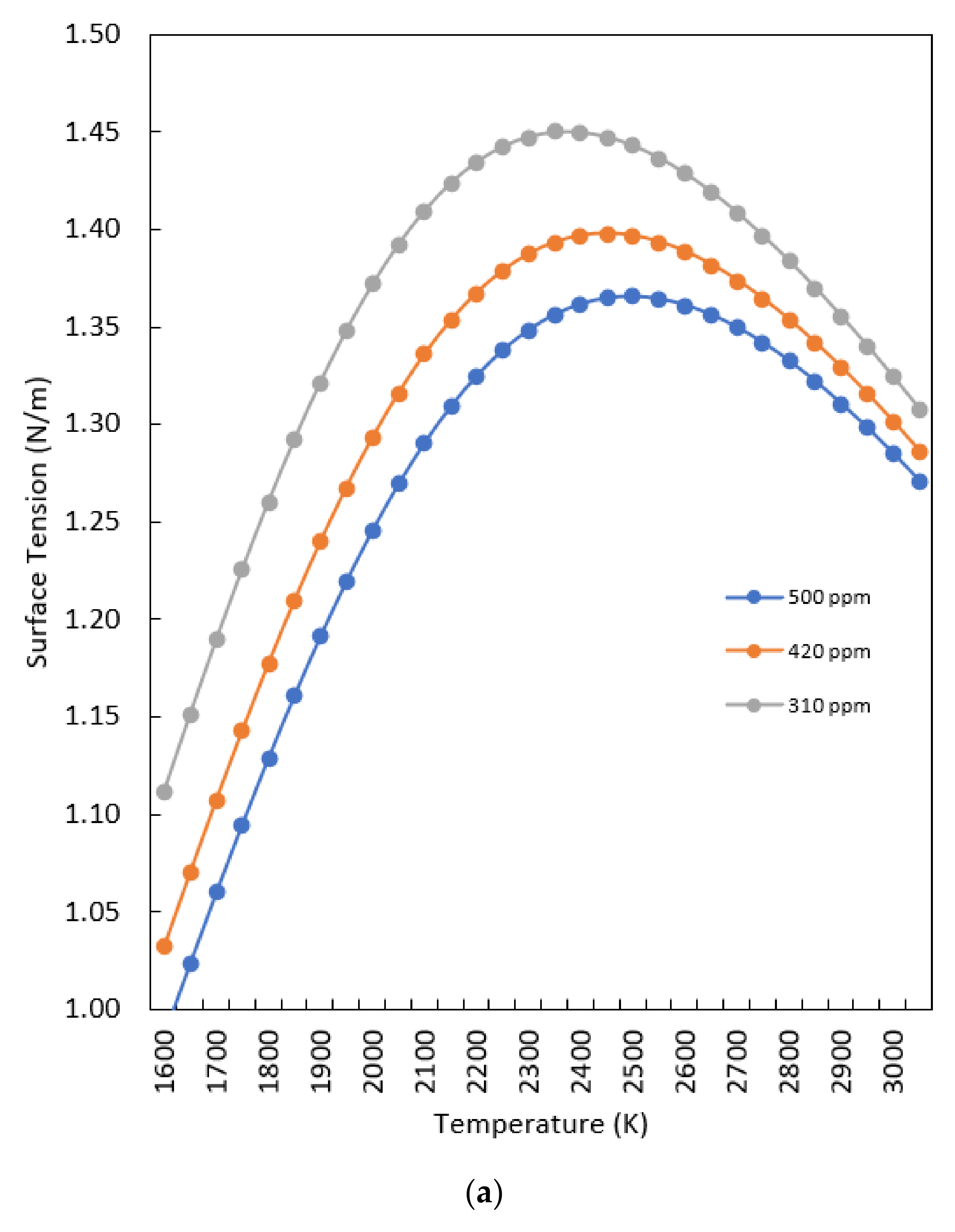

- The surface tension changes with the temperature and composition of oxygen, according to Equation (1). Moreover, only the Fe-O system is considered.

- (3)

- The physical properties, such as thermal conductivity, specific heat, and viscosity are assumed constant.

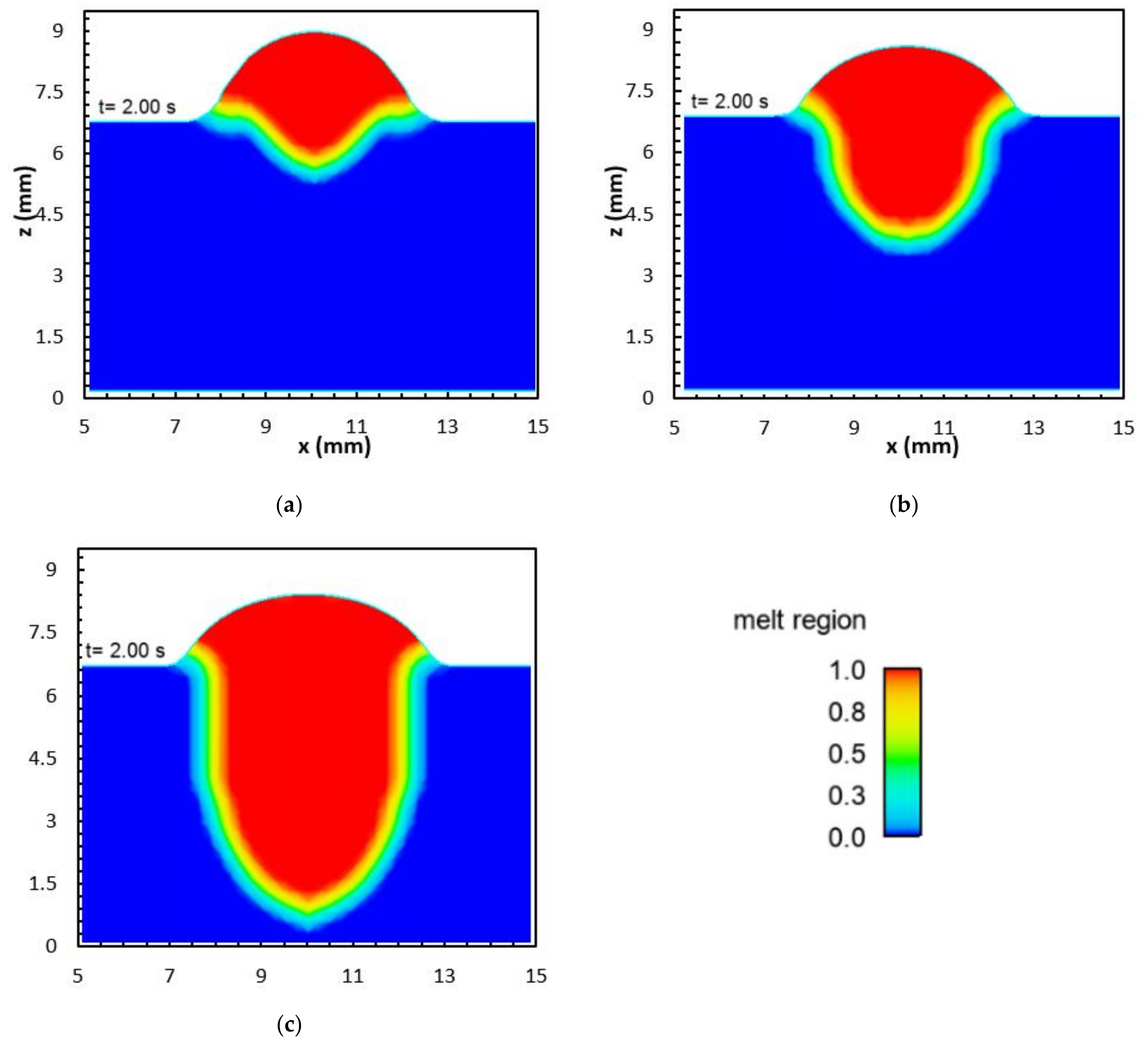

2.5. Mathematical Model

- (1)

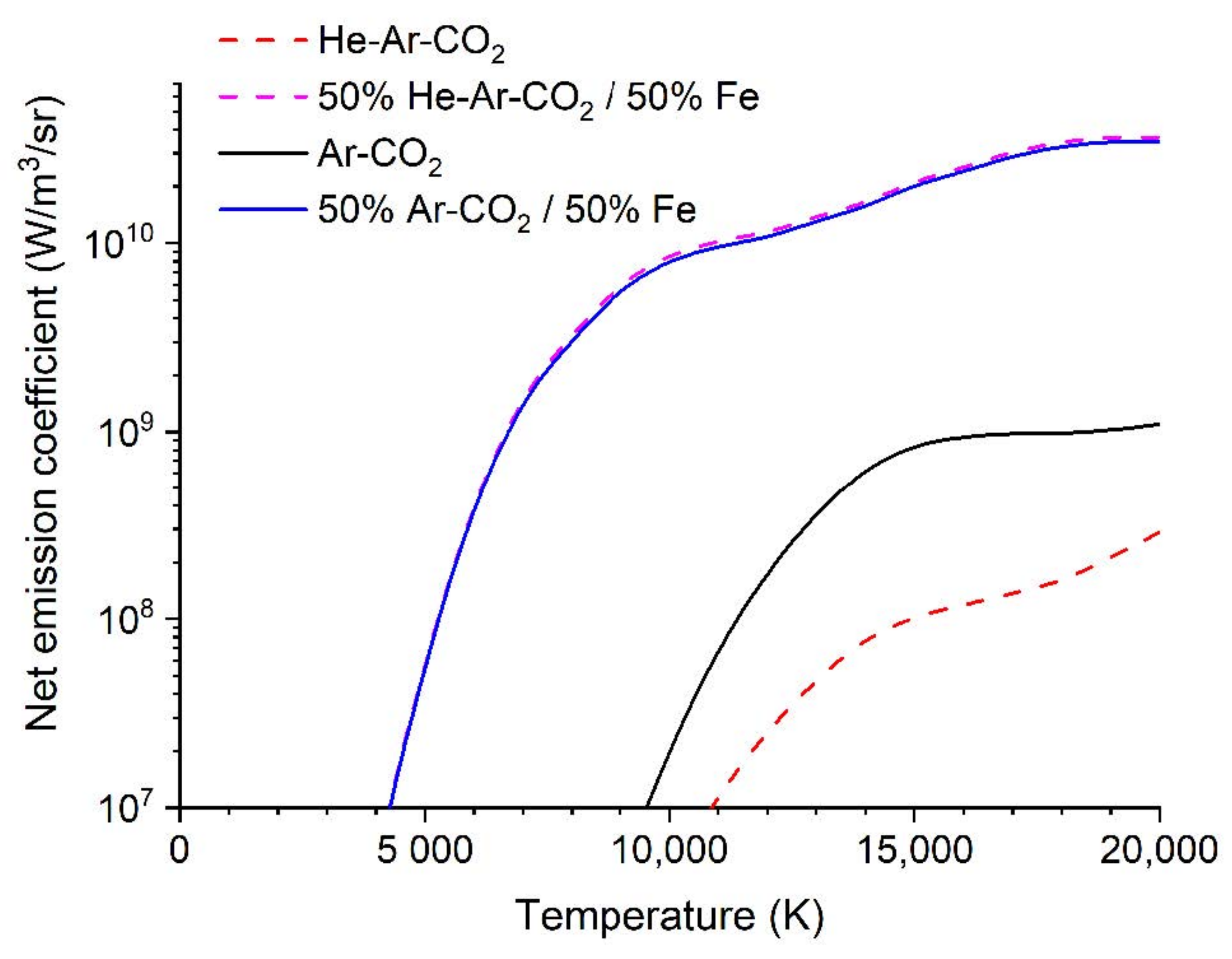

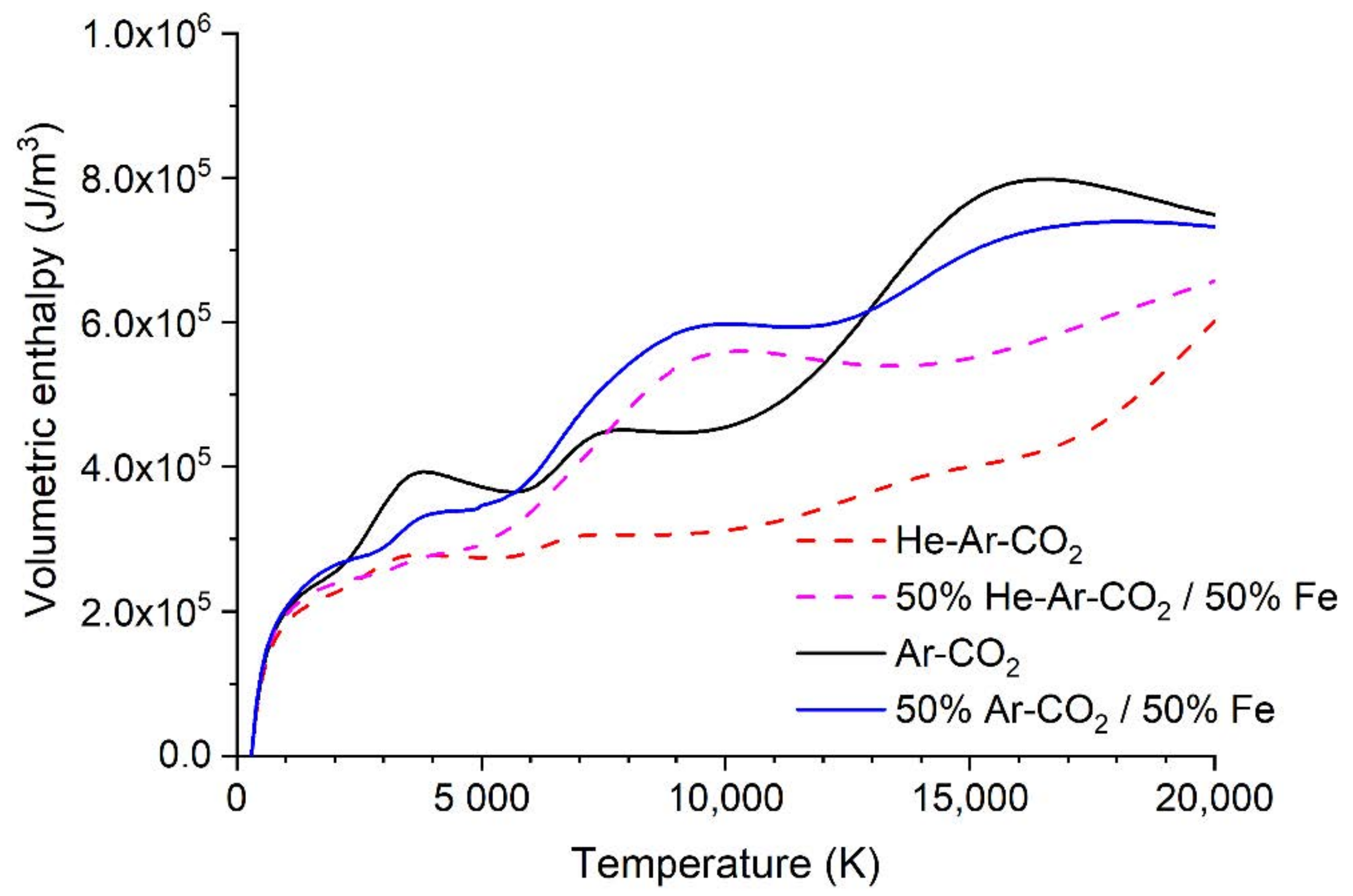

- The radiative loss in GMAW arcs is dominated by metal vapor. The net radiative emission coefficient for the ternary and binary blends, and for 50 mol% mixtures of each blend with iron vapor, are shown in Figure 14. Although the binary blend radiates more strongly, the addition of iron vapor means that both blends radiate essentially the same amount. However, the ternary blend arc is shorter (Figure 2), so the radiative loss will be smaller. Therefore, the heat transferred to the workpiece will be larger for the ternary blend arc. However, since the radiative loss is in the order of 10–20% of the total power, this will result in a difference of at most 10%.

- (2)

- A substantial fraction (30–50%) of the heat transferred to the workpiece is carried by droplets [33]. The wire feed speed is the same for both gas blends, so the volume of metal transferred is the same. However, the droplet temperature is likely to be higher for the ternary blend case (with more, smaller droplets). The higher detachment rate is consistent with a lower surface tension, which indicates a higher liquid metal temperature. If 40% of the heat is transferred by droplets and there is a 20% higher droplet enthalpy for the ternary blend, then the heat transferred will be about 10% higher.

3. Conclusions

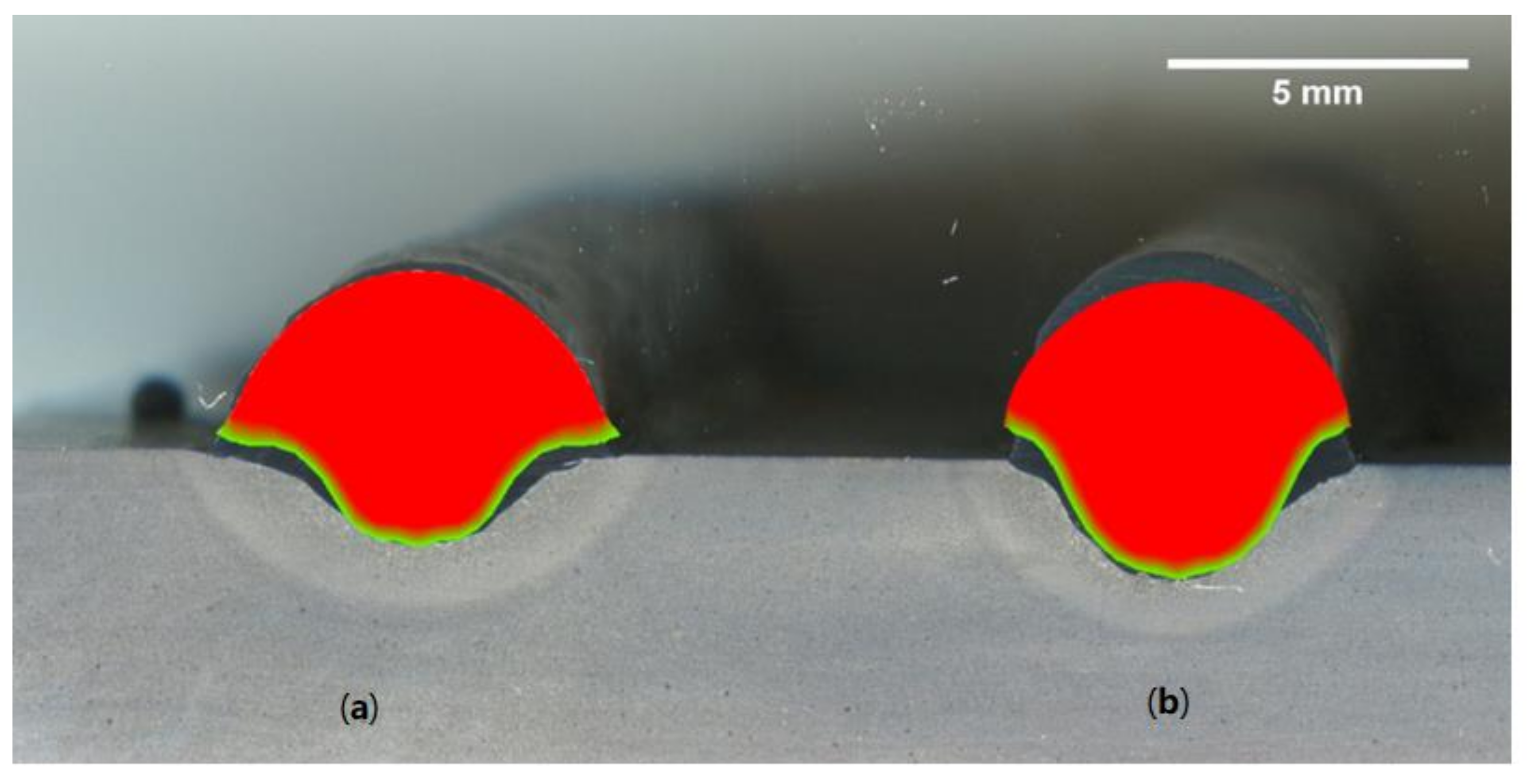

- The selection of the shielding gas plays an important role in the dimensional accuracy of WAAM-fabricated parts. The binary blend of argon and carbon dioxide produced a wider bead, while the ternary blend formed a narrower bead shape with a deeper penetration depth, when a surface tension transfer process with the selected arc welding parameters was used to fabricate a wall.

- Variations in geometry could be achieved by altering the shielding gas without altering the other AM parameters.

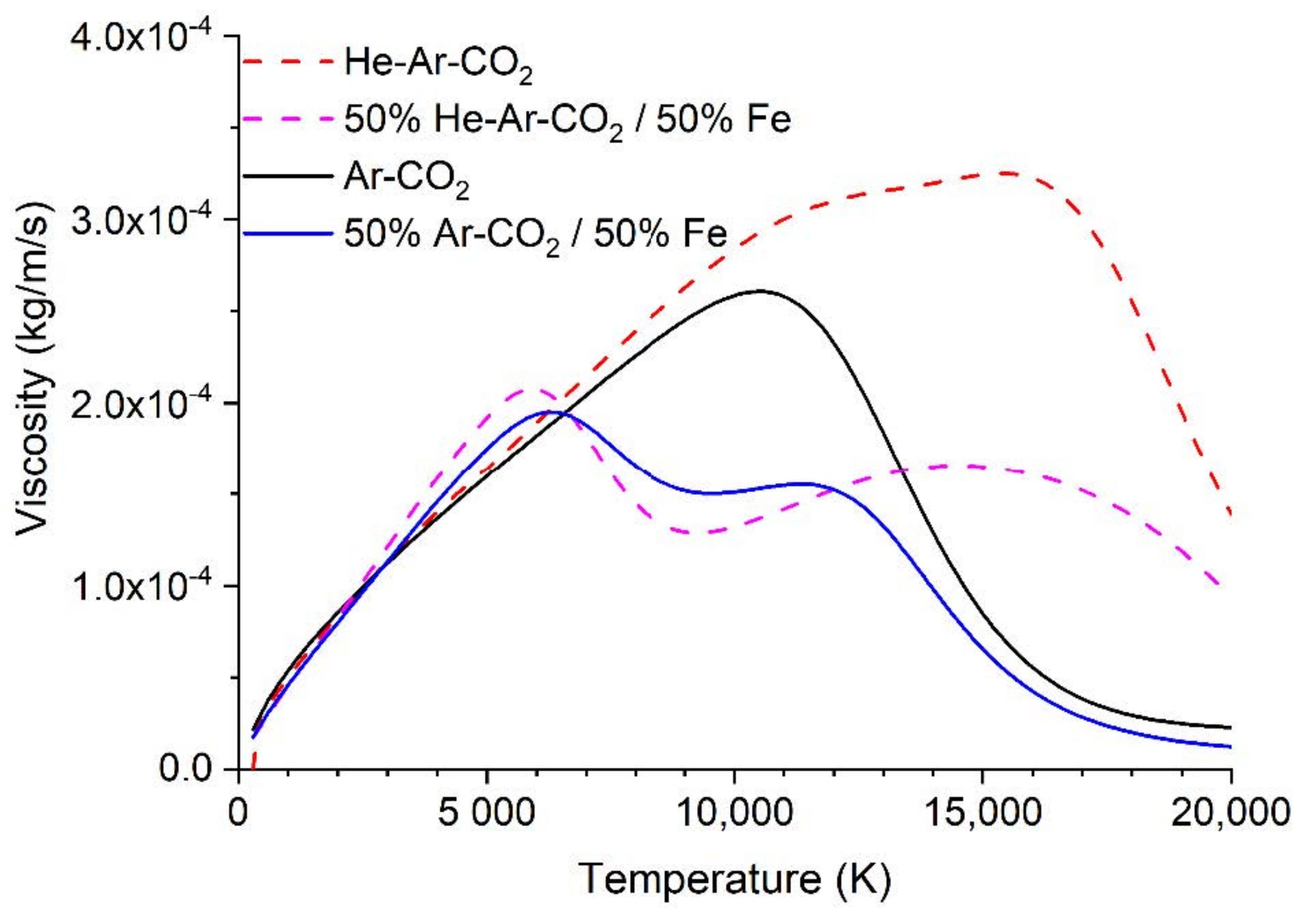

- There was a difference in heat transfer and thermal efficiency when the shielding gas was changed without changing other AM parameters. By considering the thermophysical properties of the two gas mixtures and the arc lengths, it was concluded that the arc radius at the workpiece was lower for the ternary-blend shield gas, leading to a higher heat flux.

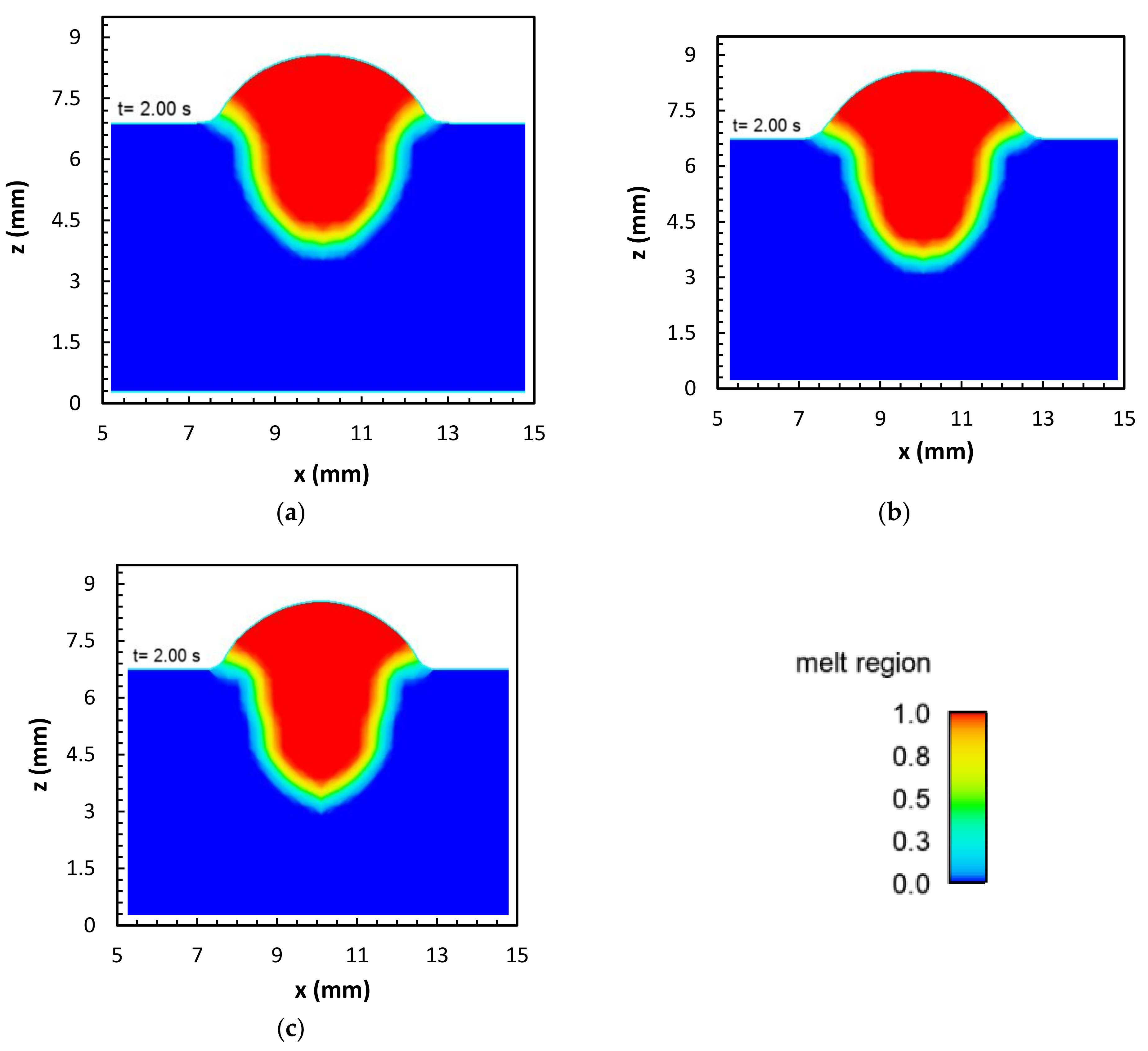

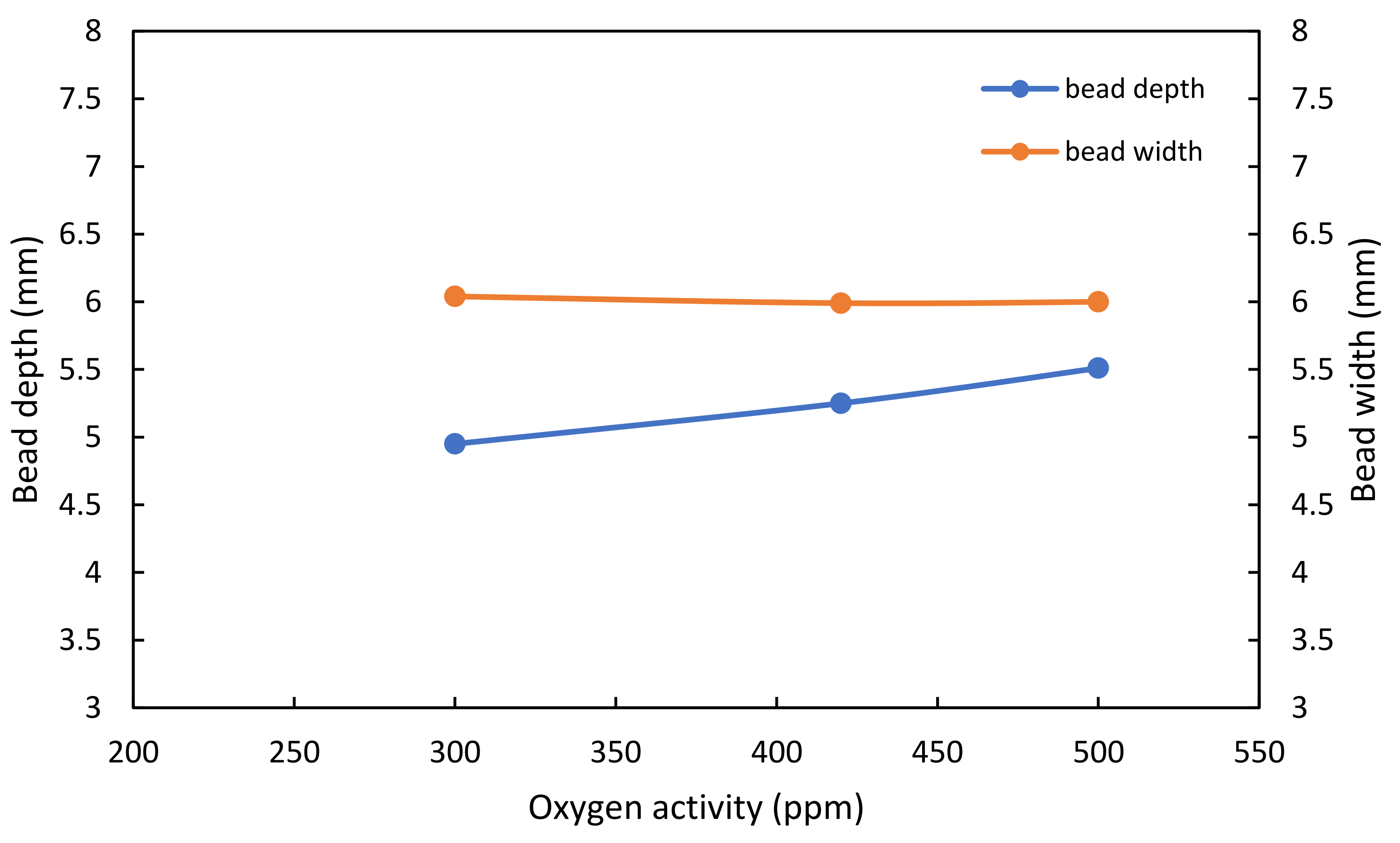

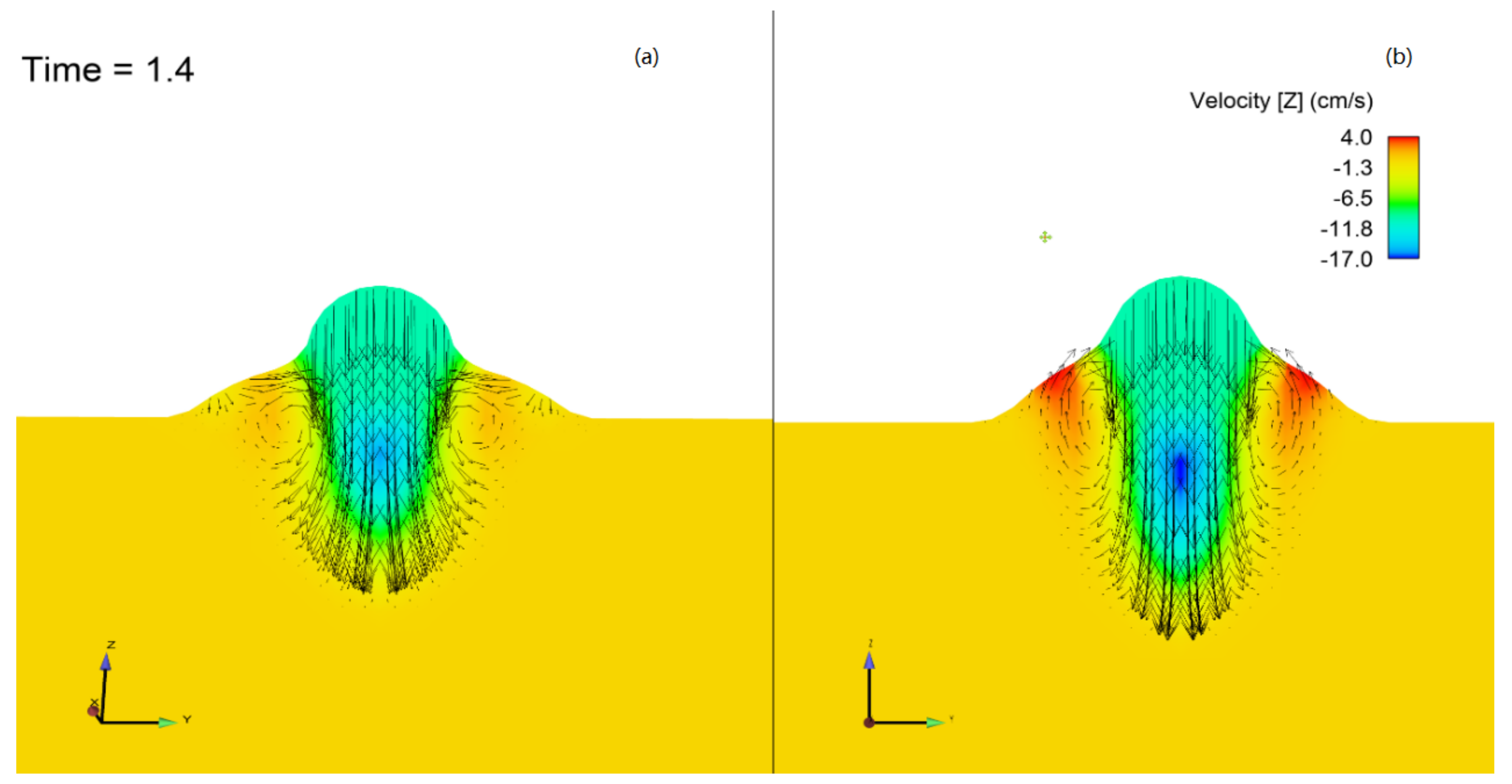

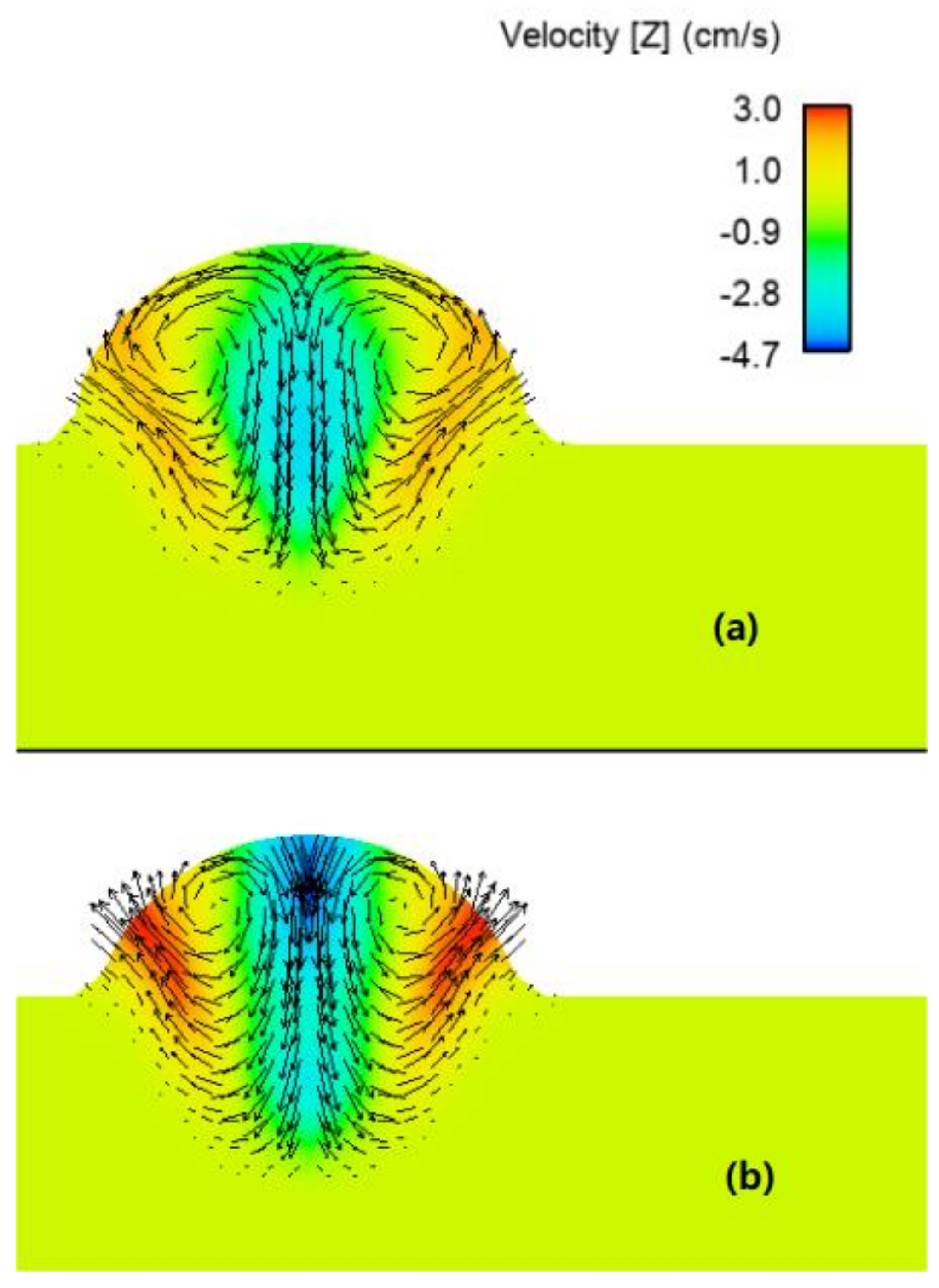

- The concentration of the surface active element oxygen was higher with the binary blend. A computational model was used to demonstrate that the influence of the oxygen concentration on the Marangoni circulation led to an increase in weld penetration depth. However, it was found that the increased heat flux for the ternary blend dominated the influence of the surface active element.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khorasani, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Rolfe, B.; Gibson, I. Additive manufacturing a powerful tool for the aerospace industry. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, M.; Silwal, B.; Purdy, A. Vibration assisted robotic hot-wire gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) for additive manufacturing of large metallic parts. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 8–10 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nycz, A.; Noakes, M.W.; Richardson, B.S.; Messing, A.K.; Post, B.K.; Paul, J.H.; Flamm, J.; Love, L.J. Challenges in Making Metal Large-scale Complex Parts for Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study Based on the Additive Manufacturing Excavator (AME); Oak Ridge National Lab: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, S.; Love, L.J.; Peter, W.; Dehoff, R. Report on Additive Manufacturing for Large-Scale Metals Workshop; Oak Ridge National Lab: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Norrish, J. 5—Gases for advanced welding processes. In Advanced Welding Processes; Norrish, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2006; pp. 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lienert, T.; Siewert, T.; Babu, S.; Acoff, V. Shielding Gases for Arc Welding. In Welding Fundamentals and Processes; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2011; Volume 6A. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.; Lewis, O.T. 5—Fabrication, Welding, and In-Shop Inspection. In Pressure Vessels Field Manual; Stewart, M., Lewis, O.T., Eds.; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2013; pp. 217–345. [Google Scholar]

- Silwal, B.; Nycz, A.; Masuo, C.J.; Noakes, M.W.; Marsh, D.; Vaughan, D. An experimental investigation of the effectiveness of Ar-CO2 shielding gas mixture for the wire arc additive process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.W.; Galloway, A.M.; McPherson, N.A. Techno-economic evaluation of reducing shielding gas consumption in GMAW whilst maintaining weld quality. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 63, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitharas, I.; Campbell, S.W.; Galloway, A.M.; McPherson, N.A.; Moore, A.J. Visualisation of al-ternating shielding gas flow in GTAW. Mater. Des. 2016, 91, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, B.; Prasad, Y.K.; Kang, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, I. Characteristics of alternate supply of shielding gases in aluminum GMA welding. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 4716–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Prasad, Y.K.; Kang, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, I. The effect of alternate supply of shielding gases in austenite stainless steel GTA welding. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 4722–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.H.; Liao, S.M.; Tsai, H.L. Effects of shielding gas compositions on arc plasma and metal transfer in gas metal arc welding. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 044902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, X.; Lin, S.; Murphy, A.B.; Dong, B.; Fan, C.; Yang, C. Influence of helium content on a ter-nary-gas-shielded GMAW process. Weld. World 2018, 62, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadiou, S.; Courtois, M.; Carin, M.; Berckmans, W. 3D heat transfer, fluid flow and electro-magnetic model for cold metal transfer wire arc additive manufacturing (Cmt-Waam). Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 10154. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Hu, J.; Tsai, H. Three-dimensional modeling of arc plasma and metal transfer in gas metal arc welding. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 52, 1709–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; DebRoy, T.; McNallan, M.J. Surface tension of binary metal—surface active solute systems under conditions relevant to welding metallurgy. Met. Mater. Trans. A 1988, 19, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucott, L.; Dong, H.; Mirihanage, W.; Atwood, R.; Kidess, A.; Gao, S.; Wen, S.; Marsden, J.; Feng, S.; Tong, M.; et al. Revealing internal flow behaviour in arc welding and additive manufacturing of metals. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murphy, A. Transport coefficients of helium and argon-helium plasmas. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 1997, 25, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.B.; Arundell, C.J. Transport coefficients of argon, nitrogen, oxygen, ar-gon-nitrogen, and argon-oxygen plasmas. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 1994, 14, 451–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.B. Transport coefficients of air, argon-air, nitrogen-air, and oxygen-air plasmas. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 1995, 15, 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Silwal, B.; Nycz, A.; Noakes, M.; Cakmak, E.; Nandwana, P.; Yamamoto, Y. Investigating the effect of different shielding gas mixtures on microstructure and mechanical properties of 410 stainless steel fabricated via large scale additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 38, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nycz, A.; Noakes, M.; Cader, M. Additive Manufacturing—A New Challenge for Automation and Robotics. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2018, 743, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwal, B.; Santangelo, M. Effect of vibration and hot-wire gas tungsten arc (GTA) on the geometric shape. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 251, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S. Thermophysical Properties of Stainless Steels No. ANL-75-55; Argonne National Lab.: Lemont, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribic, B.; Rai, R.; DebRoy, T. Numerical simulation of heat transfer and fluid flow in GTA/Laser hybrid welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2008, 13, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.L. Three-dimensional simulation of transient GMA weld pool with free surface. Weld. J. N. Y. 2004, 83, 169-S. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.N.; Dong, P. Modeling of GMA Weld Pools with Consideration of Droplet Impact. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1998, 120, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Na, S.-J. A study on the effect of contract tube-to-workpiece distance on weld pool shape in gas metal arc welding. Weld. J. 1995, 74, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tsai, H.-L. Effects of surface active elements on weld pool fluid flow and weld pen-etration in gas metal arc welding. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2001, 32, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Shi, Y. The study of surface active element on weld pool development in A-TIG welding. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2006, 14, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Z.; Zhao, H.Y.; Lei, Y.P.; Shi, Y.W. Theoretical study of Marangoni convection and weld penetration under influence of high oxygen content in base metal. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2007, 12, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haelsig, A.; Mayr, P. Energy balance study of gas-shielded arc welding processes. Weld. World 2013, 57, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Lowke, J.J. Predictions of weld pool profiles using plasma physics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006, 40, R1–R23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokomizu, Y.; Matsumura, T.; Sun, W.Y.; Lowke, J.J. Electrode sheath voltages for helium arcs between non-thermionic electrodes of iron, copper and titanium. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 1998, 31, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.G.; Kovacevic, R. Droplet formation, detachment, and impingement on the molten pool in gas metal arc welding. Met. Mater. Trans. A 1999, 30, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tsai, H.-L. Heat and mass transfer in gas metal arc welding. Part I.: The arc. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2007, 50, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Ni | Cr | Si | Mn | C | P | S | Cu | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt. % | 0.1 | 12.5 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Surface tension of pure metal at melting temperature (N m−1) | 1.943 |

| Viscosity (kg m−1 s−1) | 0.006 |

| Specific heat (J kg−1 K−1) | 460 |

| Thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1) | 22 |

| Liquidus temperature (K) | 1811 |

| Solidus temperature (K) | 1670 |

| Latent heat of fusion (J kg−1) | 2.45 × 105 |

| Reference temperature (K) | 1670 |

| Contact angle (degree) | 90 |

| Saturation pressure (N m−2) | 1.01 × 105 |

| Saturation temperature (K) | 2843 |

| Latent heat of vaporization (J kg−1) | 6.34 × 106 |

| Specific heat ratio | 1.41 |

| Vapor specific heat (J kg−1 K−1) | 460 |

| Universal gas constant (J mol−1 K−1) | 8.314 |

| Initial drop temperature (K) | 2000 |

| Surface excess at saturation (mol m−1) | 2.03 × 10−8 |

| Negative of temperature coefficient of surface tension of a pure Metal (N m−1 K−1) | 4.3 × 10−4 |

| Constant related to entropy of segregation | 0.0138 |

| Standard heat of adsorption (J mol−1) | 1.463 × 105 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silwal, B.; Pudasaini, N.; Roy, S.; Murphy, A.B.; Nycz, A.; Noakes, M.W. Altering the Supply of Shielding Gases to Fabricate Distinct Geometry in GMA Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073679

Silwal B, Pudasaini N, Roy S, Murphy AB, Nycz A, Noakes MW. Altering the Supply of Shielding Gases to Fabricate Distinct Geometry in GMA Additive Manufacturing. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(7):3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073679

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilwal, Bishal, Niraj Pudasaini, Sougata Roy, Anthony B. Murphy, Andrzej Nycz, and Mark W. Noakes. 2022. "Altering the Supply of Shielding Gases to Fabricate Distinct Geometry in GMA Additive Manufacturing" Applied Sciences 12, no. 7: 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073679

APA StyleSilwal, B., Pudasaini, N., Roy, S., Murphy, A. B., Nycz, A., & Noakes, M. W. (2022). Altering the Supply of Shielding Gases to Fabricate Distinct Geometry in GMA Additive Manufacturing. Applied Sciences, 12(7), 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12073679