Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

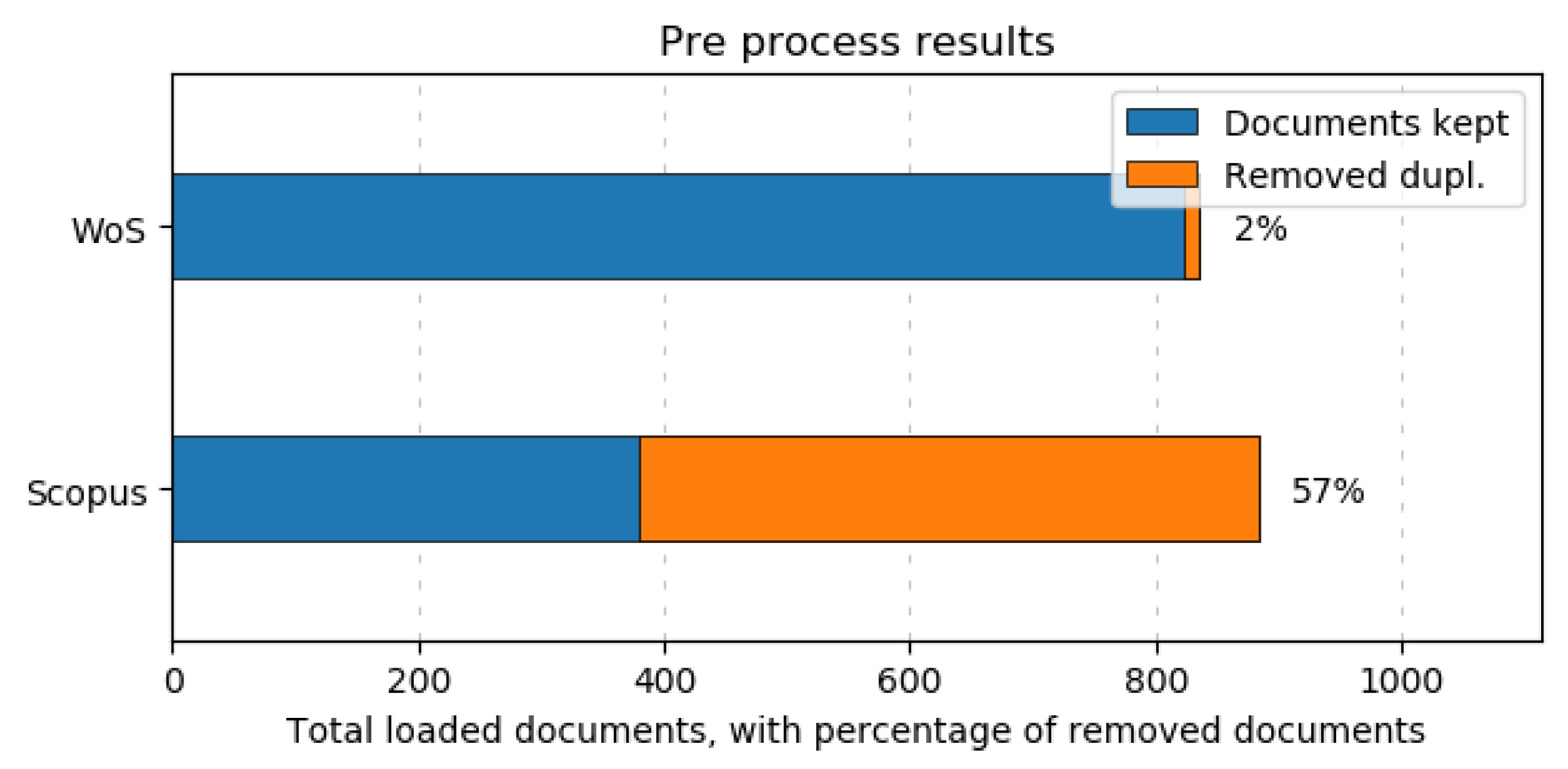

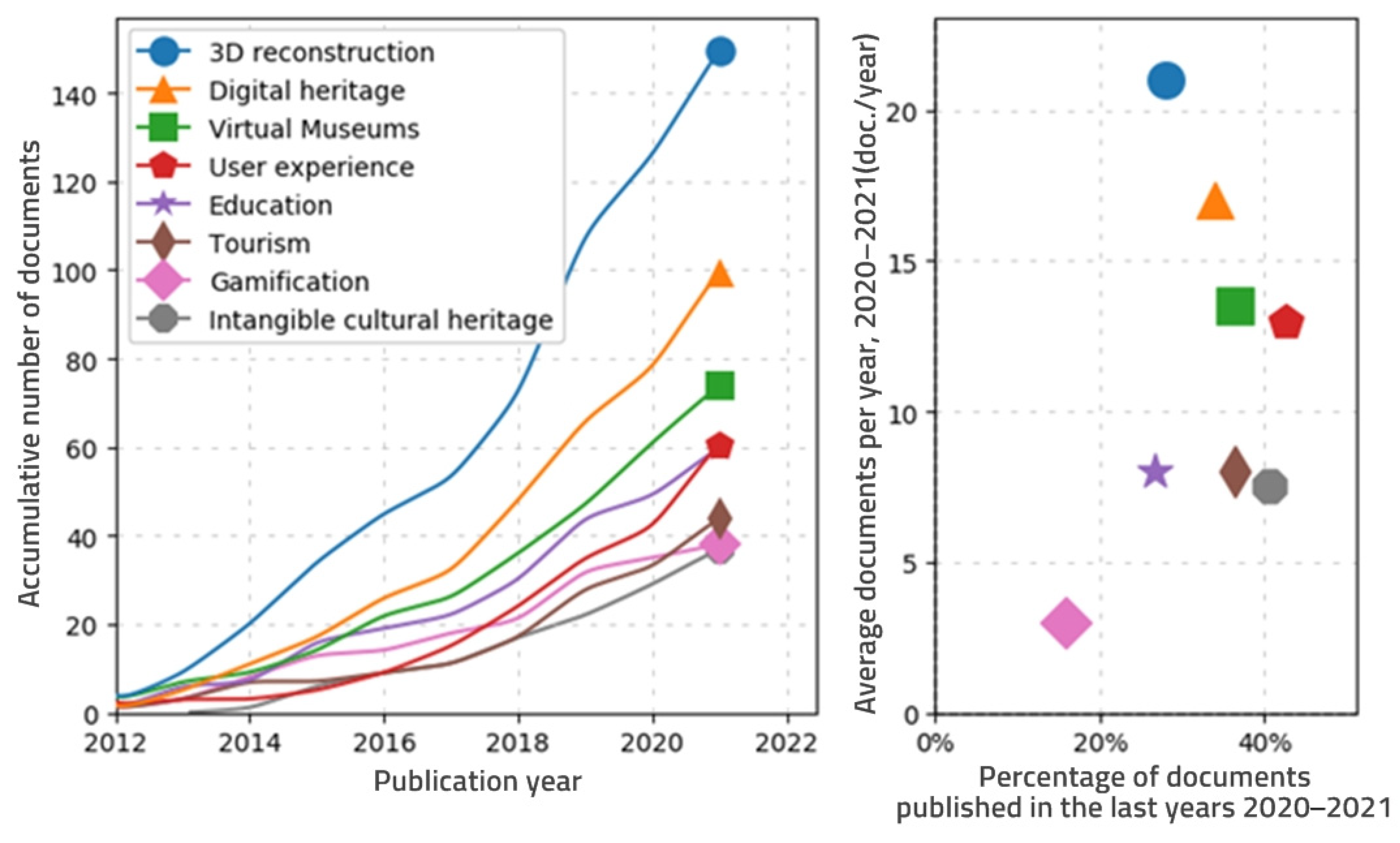

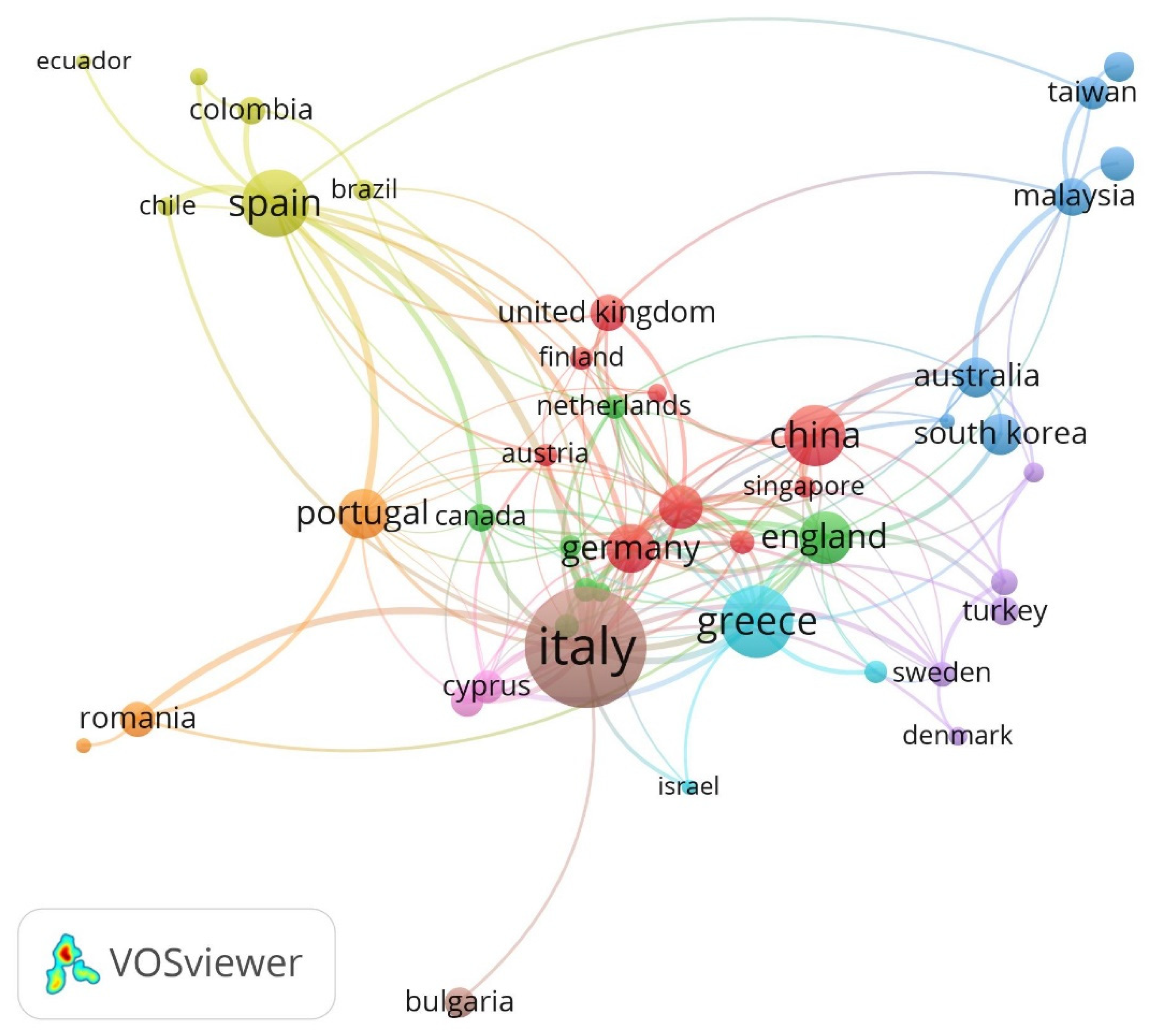

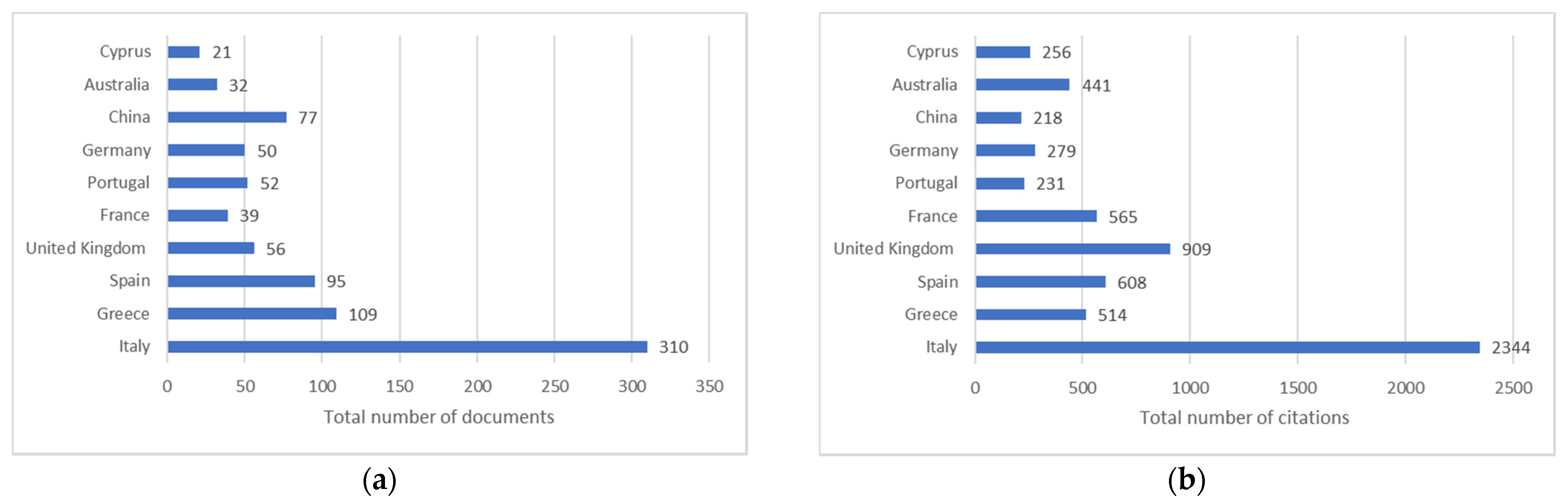

2. Research Method

3. Top Trending Applications of AR in Cultural Heritage

3.1. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction

3.2. Digital Heritage

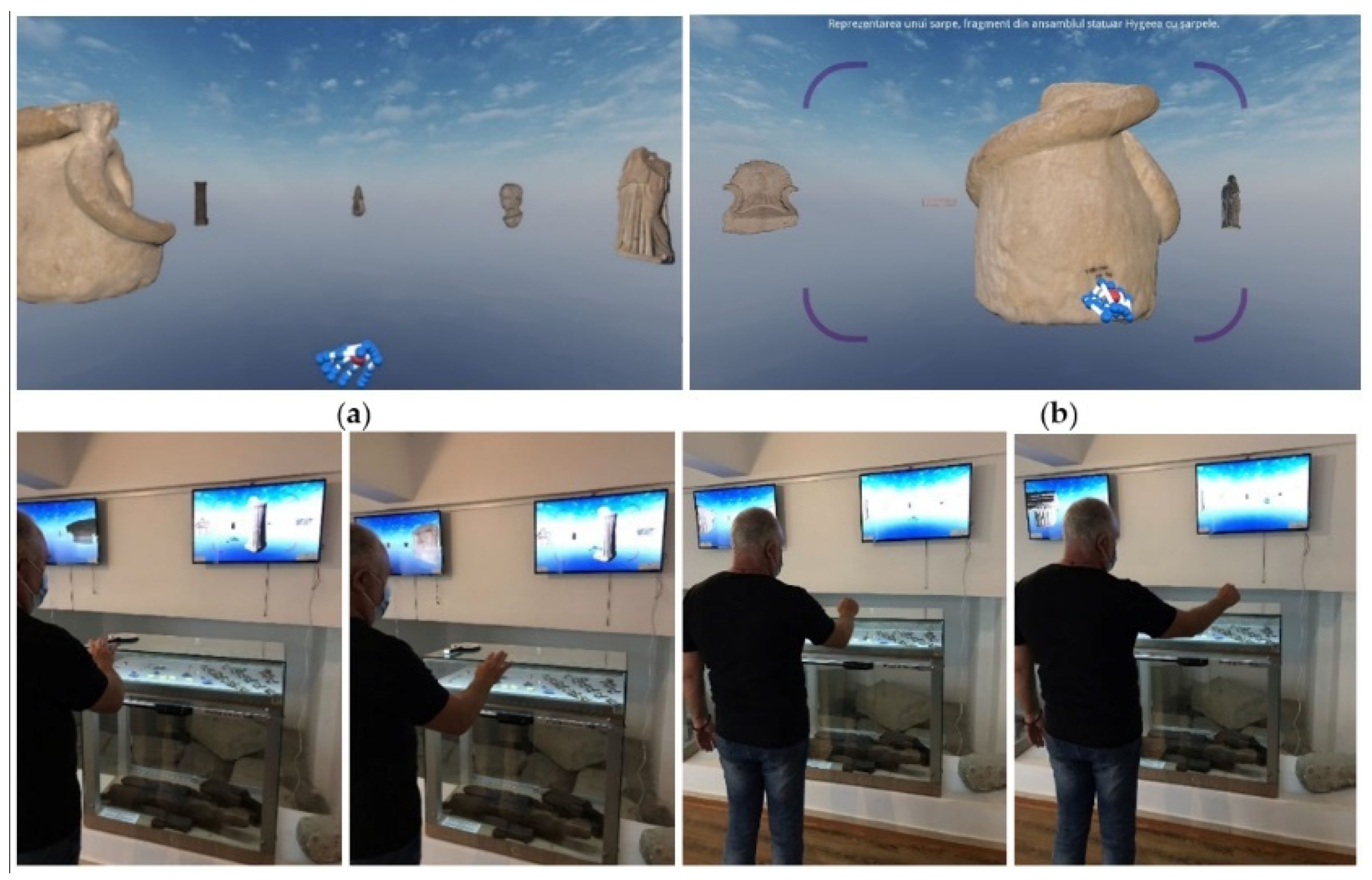

3.3. Virtual Museums

3.4. User Experience

3.5. Education

3.6. Tourism

3.7. Gamification

3.8. Intangible Cultural Heritage

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Felix, R.; Hinsch, C.; Shahab, H.; Alt, F. What is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual Reality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 133, 107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Singhal, A. Augmented Reality and its effect on our life. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence), Uttar Pradesh, India, 10–11 January 2019; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, F.; Collotta, M.; Pau, G.; Termine, F. An Overview of Augmented Reality. Computers 2022, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanovic, V.; Ivkovic-Kihic, I.; Boskovic, D.; Mijatovic, B.; Prazina, I.; Skaljo, E.; Rizvic, S. Interaction in eXtended Reality Applications for Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán, M.J.; Merchán, P.; Pérez, E. Good Practices in the Use of Augmented Reality for the Dissemination of Architectural Heritage of Rural Areas. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboc, R.G.; Duguleană, M.; Voinea, G.-D.; Postelnicu, C.-C.; Popovici, D.-M.; Carrozzino, M. Mobile Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage: Following the Footsteps of Ovid among Different Locations in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, S.Z.; Bushroa, A.R. Bibliometric and content analysis on publications in digitization technology implementation in cultural heritage for recent five years (2016–2021). Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2022, 25, e00225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslik, E. 3D Digitization in Cultural Heritage Institutions Guidebook; National Museum of Dentistry: Baltimore, MD, USA,, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Poulopoulos, V.; Wallace, M. Digital Technologies and the Role of Data in Cultural Heritage: The Past, the Present, and the Future. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Keramopoulos, E.; Diamantaras, K. Enhancing the functionality of augmented reality using deep learning, semantic web and knowledge graphs: A review. Vis. Inform. 2020, 4, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, A.; Perifanou, M.; Economides, A.A. A review of ontologies for augmented reality cultural heritage applications. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzigrigoriou, P.; Nikolakopoulou, V.; Vakkas, T.; Vosinakis, S.; Koutsabasis, P. Is architecture connected with intangible cultural heritage? Reflections from the digital documentation of local architecture and interactive application design for the case of marble, olive oil, and mastic heritage in three Aegean islands. Heritage 2021, 4, 664–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.S.; Gain, J. A survey of augmented, virtual, and mixed reality for cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2018, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenor, J.; Ma, M. A Review of Augmented Reality Applications for History Education and Heritage Visualisation. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2019, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, F.N.M.; Khidzir, N.Z.; Ismail, A.R.; Mat, K.A. An exploratory study on mobile augmented reality (AR) application for heritage content. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2016, 4, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambati, S.; Gargiulo, C. The evolution of urban competitiveness studies over the past 30 years. A bibliometric analysis. Cities 2022, 128, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlasi, R.; Ramezani, A.; Tabatabaei-Malazy, O.; Alatab, S.; Oveissi, V.; Larijani, B. Scientometric assessment of scientific documents published in 2020 on herbal medicines used for COVID-19. J. Herb. Med. 2022, 35, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Ausecha, C.; Ruiz-Rosero, J.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, G. RFID Applications and Security Review. Computation 2021, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münster, S. Digital heritage as a scholarly field—Topics, researchers, and perspectives from a bibliometric point of view. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2019, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulifar, L.; Widiaty, I.; Anggraini, D.N.; Nugraha, E.; Minggra, R.; Kurniaty, H.W. Digitalizing museums: A bibliometric study. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2021, 16, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- van Ruymbeke, M.; Nofal, E.; Billen, R. 3D Digital Heritage and Historical Storytelling: Outcomes from the Interreg EMR Terra Mosana Project. In Culture and Computing; Rauterberg, M., Ed.; HCII 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, L.; Ibanescu, M.; Keen, C.; Lobato-Calleros, O.; Niebla-Zatarain, J. Bibliometric Study of Family Business Succession Between 1939 and 2017: Mapping and Analyzing Authors’ Networks; Springer International Publishing: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; Volume 117, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Rosero, J.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, G.; Viveros-Delgado, J. Software survey: ScientoPy, a scientometric tool for topics trend analysis in scientific publications. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarke, M.; Lenzerini, M.; Vassiliou, Y.; Vassiliadis, P. Fundamentals of Data Warehouses; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; ISBN 978-3-662-05153-5. [Google Scholar]

- VOSviewer—Visualizing Scientifc Landscapes. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Cultural Heritage at Risk: United States. Available online: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/special-topics-art-history/arches-at-risk-cultural-heritage-education-series/xa0148fd6a60f2ff6:cultural-heritage-endangered-round-the-world/a/cultural-heritage-at-risk-united-states (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Panou, C.; Ragia, L.; Dimelli, D.; Mania, K. Outdoors Mobile Augmented Reality Application Visualizing 3D Reconstructed Historical Monuments. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management (GISTAM 2018), Porto, Portugal, 17–19 March 2018; pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campi, M.; di Luggo, A.; Palomba, D.; Palomba, R. Digital surveys and 3D reconstructions for augmented accessibility of archaeological heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machidon, O.M.; Postelnicu, C.C.; Girbacia, F.S. 3D Reconstruction as a Service–Applications in Virtual Cultural Heritage. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics; De Paolis, L., Mongelli, A., Eds.; AVR 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, M.; Chellini, G.; Migliori, S.; Perozziello, A.; Pierattini, S.; Puccini, M.; Cosma, A. Comparison and integration of techniques for the study and valorisation of the Corsini Throne in Corsini Gallery in Roma. ACTA IMEKO 2021, 10, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Z.; Sunar, M.S.; Pan, Z. A Review on Augmented Reality for Virtual Heritage System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, L.; Bellon, O.R.P.; Silva, L. 3D reconstruction methods for digital preservation of cultural heritage: A survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2014, 50, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portalés, C.; Lerma, J.L.; Pérez, C. Photogrammetry and augmented reality for cultural heritage applications. Photogramm. Rec. 2009, 24, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, E.Y.; Wahyudi, A.K.; Dumingan, C. A proposed combination of photogrammetry, Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Headset for heritage visualization. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC), Mataram, Indonesia, 28–29 October 2016; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, D.; Klein, M. 3D preservation of buildings–Reconstructing the past. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 9153–9170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; Bilotta, G.; Meduri, G.M.; De Carlo, D.; Nunnar, A. Laser scanner technology, ground-penetrating radar and augmented reality for the survey and recovery of artistic, archaeological and cultural heritage. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 4, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; Nunnari, A.; Ponterio, R.C. Laser scanner for the Architectural and Cultural Heritage and Applications for the Dissemination of the 3D Model. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scianna, A.; Gaglio, G.F.; Grima, R.; La Guardia, M. The virtualization of CH for historical reconstruction: The AR fruition of the fountain of St. George square in Valletta (Malta). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P.; Jimenez Fernandez-Palacios, B.; Muñoz-Nieto, Á.L.; Arias-Sanchez, P.; Gonzalez-Aguilera, D. Mobile LiDAR system: New possibilities for the documentation and dissemination of large cultural heritage sites. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, S.; Le, S.T.; Tran, M.K.; Tran, H.M. Reconstruction of 3D digital heritage objects for VR and AR applications. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2021, 6, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, N.J.; Diao, P.H.; Chen, Y. ARTS, an AR tourism system, for the integration of 3D scanning and smartphone AR in cultural heritage tourism and pedagogy. Sensors 2019, 19, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pons, S.; Carrión-Ruiz, B.; Lerma, J.L.; Villaverde, V. Design and implementation of an augmented reality application for rock art visualization in Cova dels Cavalls (Spain). J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 39, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.R.; Sevilla, J.S.; San Gabriel, J.W.D.; Cruz, A.J.P.D.; Caselis, E.J.S. Design and Development of Augmented Reality (AR) Mobile Application for Malolos’ Kameztizuhan (Malolos Heritage Town, Philippines). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Games, Entertainment, Media Conference (GEM), Galway, Ireland, 15–17 August 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroni, E. An augmented experiences in cultural heritage through mobile devices: “Matera tales of a city” project. In Proceedings of the 2012 18th International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia, Milan, Italy, 2–5 September 2012; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A. Digital Artifacts and Landscapes. Experimenting with Placemaking at the Impero Project. Heritage 2021, 4, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, U.S.; Tissen, L.N.; Vermeeren, A.P. 3D Reproductions of Cultural Heritage Artefacts: Evaluation of significance and experience. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2021, 5, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girbacia, F.; Butnariu, S.; Orman, A.P.; Postelnicu, C.C. Virtual restoration of deteriorated religious heritage objects using augmented reality technologies. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 2013, 9, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Boboc, R.G.; Gîrbacia, F.; Duguleană, M.; Tavčar, A. A handheld Augmented Reality to revive a demolished Reformed Church from Braşov. In Proceedings of the Virtual Reality International Conference-Laval Virtual, Laval, France, 22–24 March 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfenov, V.; Igoshin, S.; Masaylo, D.; Orlov, A.; Kuliashou, D. Use of 3D Laser Scanning and Additive Technologies for Reconstruction of Damaged and Destroyed Cultural Heritage Objects. Quantum Beam Sci. 2022, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, A.F.; Barra, S.; Galeotafiore, G.; Díaz, C.; Aura, E.; Sánchez, M.; Vendrell, E. An Augmented Reality Mobile App for Museums: Virtual Restoration of a Plate of Glass. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Digital Heritage, EuroMed 2018, Nicosia, Cyprus, 29 October–3 November 2018; Volume 11196 LNCS, pp. 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, G.D.; Girbacia, F.; Postelnicu, C.C.; Marto, A. Exploring cultural heritage using augmented reality through Google’s Project Tango and ARCore. In VR Technologies in Cultural Heritage; Duguleană, M., Carrozzino, M., Gams, M., Tanea, I., Eds.; VRTCH 2018. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 904, pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Concept of Digital Heritage. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/information-preservation/digital-heritage/concept-digital-heritage (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Balduini, M.; Celino, I.; Dell’Aglio, D.; Della Valle, E.; Huang, Y.; Lee, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Tresp, V. BOTTARI: An augmented reality mobile application to deliver personalized and location-based recommendations by continuous analysis of social media streams. J. Web Semant. 2012, 16, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Lim, C.K. Digital heritage gamification: An augmented-virtual walkthrough to learn and explore historical places. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Bikaner, India, 24–25 November 2017; Volume 1891, p. 020139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, N.R. Digital culture and art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2014, 41, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A.; Wang, N.; Ibach, M.K.; Fehlmann, B.; Schicktanz, N.S.; Bentz, D.; Michael, T.; Papassotiropoulos, A.; de Quervain, D.J.F. Effectiveness of a smartphone-based, augmented reality exposure app to reduce fear of spiders in real-life: A randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 82, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, L.V.; van Gelderen, M.J.; van Zuiden, M.; Nijdam, M.J.; Vermetten, E.; Olff, M.; Bakker, A. Efficacy of immersive PTSD treatments: A systematic review of virtual and augmented reality exposure therapy and a meta-analysis of virtual reality exposure therapy. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 143, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D.M.; Randhawa, K.; Maheu, M.M.; McKean, A.J.; Pantera, R.; Mishkind, M.C.; Rizzo, A. A review of telepresence, virtual reality, and augmented reality applied to clinical care. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 5, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, C.; Caye, V.; Luca, L.D.; Favre-Brun, A. Genius Loci: Digital heritage augmentation for immersive performance. Int. J. Arts Technol. 2014, 7, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunità, M.; Gerino, A.; Lim, V.; Picinali, L. Design and Evaluation of a Web- and Mobile-Based Binaural Audio Platform for Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng, E.; Cai, S.; Leow, F.-T.; Zhang, T.E. Adoption and use of emerging cultural technologies in China’s museums. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 37, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, I. Standard Cataloguing of Augmented Objects for a Design Museum. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 1, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvić, S.; Bošković, D.; Okanović, V.; Kihić, I.I.; Prazina, I.; Mijatović, B. Time Travel to the Past of Bosnia and Herzegovina through Virtual and Augmented Reality. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-S. Applying the ARCS Motivation Theory for the Assessment of AR Digital Media Design Learning Effectiveness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguleană, M. eHERITAGE Project—Building a Cultural Heritage Excellence Center in the Eastern Europe. In Proceedings of the Digital Heritage: Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection. EuroMed 2018, Nicosia, Cyprus, 29 October–3 November 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudazi, A.; Boccaccini, R. Augmented museums through mobile apps. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Horizon 2020 and Creative Europe vs. Digital Heritage: A European Projects Crossover, Flash News Co-Located with the International Conference Museums and the We 2014, Florence, Italy, 18 February 2014; Volume 1336, pp. 12–17, ISSN 1613-0073. [Google Scholar]

- Partarakis, N.; Zidianakis, E.; Antona, M.; Stephanidis, C. Art and Coffee in the Museum. In Distributed, Ambient, and Pervasive Interactions; Streitz, N., Markopoulos, P., Eds.; DAPI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9189, pp. 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teneketzis, A. Exploring the emerging digital scene in Art History and museum practice. Esboços Histórias Contextos Globais 2020, 27, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Teixeira, L. Developing an eXtended Reality platform for Immersive and Interactive Experiences for Cultural Heritage: Serralves Museum and Coa Archeologic Park. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Recife, Brazil, 9–13 November 2020; pp. 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallergis, G.; Christoulakis, M.; Diakakis, A.; Ioannidis, M.; Paterakis, I.; Manoudaki, N.; Liapi, M.; Oungrinis, K.A. Open City Museum: Unveiling the Cultural Heritage of Athens Through an-Augmented Reality Based-Time Leap. In Proceedings of the Culture and Computing, 8th International Conference, C&C 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, P.; Hermon, S. Can I touch this? Using natural interaction in a museum augmented reality system. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 12, e00088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisi, V.; Cesario, V.; Nunes, N. Augmented reality museum’s gaming for digital natives: Haunted encounters in the Carvalhal’s palace. In Entertainment Computing and Serious Games; Van der Spek, E., Göbel, S., Do, E.L., Clua, E., Baalsrud Hauge, J., Eds.; ICEC-JCSG 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland,, 2019; Volume 11863, pp. 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.K.; Jeong, D.; Lee, J.; Kim, T.; Lee, J. Developing Museum Education Content: AR Blended Learning. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2021, 40, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.M.; Schmidt, W.; Vlachopoulos, D. The Use of Augmented Reality (AR) In Museum Education: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 14th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 2–4 March 2020; pp. 3179–3186. [Google Scholar]

- Partarakis, N.; Antona, M.; Zidianakis, E.; Stephanidis, C. Adaptation and Content Personalization in the Context of Multi User Museum Exhibits. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Advanced Visual Interfaces for Cultural Heritage (AVI*CH 2016), Bari, Italy, 7–10 June 2016; pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, H.; Champion, E.; Bekele, M. From photo to 3D to mixed reality: A complete workflow for cultural heritage visualisation and experience. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 13, e00102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.N.; Cox, T.N. Alternating reality: An interweaving narrative of physical and virtual cultural exhibitions. Presence 2018, 26, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaraba, N.; Conlan, O.; Edmond, J.; Arnds, P. Digital narrative conventions in heritage trail mobile apps. New Rev. Hypermedia Multimed. 2019, 25, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Bakar, J.A.; Zulkifli, A. A Conceptual Model of Mobile Augmented Reality for Hearing Impaired Museum Visitors’ Engagement. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2020, 14, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Foukarakis, M.; Moutsaki, M.; Zidianakis, E.; Patakos, A.; Tasiopoulou, E. Supporting sign language narrations in the museum. Heritage 2022, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Measuring the impact of functional and experiential mixed reality elements on a museum visit. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1990–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzer, M.G. How can augmented reality improve the user experience of digital products and engagement with cultural heritage outside the museum space? IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 949, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, D.-M.; Iordache, D.; Comes, R.; Neamțu, C.G.D.; Băutu, E. Interactive Exploration of Virtual Heritage by Means of Natural Gestures. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T.H. Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: A stakeholder approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-I.D.; Tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. Augmented Reality Smart Glasses (ARSG) visitor adoption in cultural tourism. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, E.; Kuflik, T. Enhancing cultural heritage outdoor experience with augmented-reality smart glasses. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 24, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. The MIT museum glassware prototype: Visitor experience exploration for designing smart glasses. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2016, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S. A visitors’ experience model for mixed reality in the museum. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-I.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. User experience model for augmented reality applications in urban heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, I.; Gale, N.; Mirza-Babei, P.; Reid, S. More than meets the eye: The benefits of augmented reality and holographic displays for digital cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2017, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.; Cha, H.S. Development of an augmented reality tour guide for a cultural heritage site. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2019, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damala, A.; Ruthven, I.; Hornecker, E. The MUSETECH model: A comprehensive evaluation framework for museum technology. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2019, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damala, A.; Hornecker, E.; Van der Vaart, M.; van Dijk, D.; Ruthven, I. The Loupe: Tangible augmented reality for learning to look at Ancient Greek Art. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2016, 16, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, N.; Gong, Q.; Zhou, J.; Chen, P.; Kong, W.; Chai, C. Value-based model of user interaction design for virtual museum. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2021, 3, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzelli, G.; Raia, A.; Ricciardi, S.; De Nino, M.; Barile, N.; Perrella, M.; Tramontano, M.; Pagano, P.; Palombini, A. An integrated VR/AR framework for user-centric interactive experience of cultural heritage: The ArkaeVision project. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 15, e00124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguleana, M.; Brodi, R.; Girbacia, F.; Postelnicu, C.; Machidon, O.; Carrozzino, M. Time-travelling with mobile augmented reality: A case study on the piazza dei miracoli. In Proceedings of the Digital Heritage: Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection: 6th International Conference, EuroMed 2016, Nicosia, Cyprus, 31 October–5 November 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besbes, B.; Collette, S.N.; Tamaazousti, M.; Bourgeois, S.; Gay-Bellile, V. An interactive augmented reality system: A prototype for industrial maintenance training applications. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Bari, Italy, 5–8 November 2012; pp. 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Guo, S.; Cai, S. Design and Implementation of an Augmented Reality Application with an English Learning Lesson. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE), Wollongong, Australia, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 494–499. [Google Scholar]

- tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T.H.; Tom Dieck, D. Enhancing art gallery visitors’ learning experience using wearable augmented reality: Generic learning outcomes perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 2014–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, M.; Lacko, J.; Samuelčík, M. Applications of multi-touch augmented reality system in education and presentation of virtual heritage. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 25, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo-Nagata, J.; Abad, F.M.; Giner, J.G.B.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Augmented reality and pedestrian navigation through its implementation in m-learning and e-learning: Evaluation of an educational program in Chile. Comput. Educ. 2017, 111, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Economou, D.; Bouki, V.; Psarrou, A.; Jin, L.; Pritchard, C.; Kolyda, F. Mobile augmented reality for cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile Wireless Middleware, Operating Systems, and Applications, London, UK, 22–24 June 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, A.I.; Asensio, M.; Vicent, N.; Cuenca, J.M. Mobile devices: A tool for tourism and learning at archaeological sites. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2012, 8, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, D.; Mavridis, P.; Andreadis, A.; Karigiannis, J.N. Using virtual environments to tell the story: The battle of Thermopylae. In Proceedings of the 2011 Third International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications, Athens, Greece, 4–6 May 2011; pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez-Etxeberria, A.; Gómez-Carrasco, C.J.; Fontal, O.; García-Ceballos, S. Virtual environments and augmented reality applied to heritage education. An evaluative study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O.; García-Ceballos, S.; Arias Martínez, B.; Arias González, V. Assessing the Quality of Heritage Education Programs: Construction and Calibration of the Q-Edutage Scale. Rev. Psicodidác. 2019, 24, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Vargas, J.C.; Fabregat, R.; Carrillo-Ramos, A.; Jové, T. Survey: Using Augmented Reality to Improve Learning Motivation in Cultural Heritage Studies. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, S.; Styliaras, G.; Bassounas, A. Augmented reality applications in education: Teachers point of view. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenu, C.; Pittarello, F. Svevo tour: The design and the experimentation of an augmented reality application for engaging visitors of a literary museum. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2018, 114, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camurri, A.; Volpe, G. The intersection of art and technology. IEEE MultiMedia 2016, 23, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K.; Champion, E. A Comparison of Immersive Realities and Interaction Methods: Cultural Learning in Virtual Heritage. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rome Reborn. Available online: https://www.romereborn.org/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Frischer, B.; Abernathy, D.; Giuliani, F.C.; Scott, R.T.; Ziemssen, H. A New Digital Model of the Roman Forum. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2006, 163–182, Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Supplementary Series Number 61. ISSN 1963-4304. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/36574837/Frischer_et_al_Roman_Forum_2006_pdf (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Gaitatzes, A.; Christopoulos, D.; Voulgari, A.; Roussou, M. Hellenic Cultural Heritage through Immersive Virtual Archaeology. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia (VSMM’00), Ogaki, Japan, 3–6 October 2000; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahakis, V.; Ioannidis, M.; Karigiannis, J.; Tsotros, M.; Gounaris, M.; Stricker, D.; Gleue, T.; Daehne, P.; Almeida, L. Archeoguide: An augmented reality guide for archaeolog sites. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2002, 22, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Neira, C.; Sandin, D.J.; DeFanti, T.A.; Kenyon, R.V.; Hart, J.C. The CAVE: Audio visual experience automatic virtual environment. Commun. ACM 1992, 35, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A.; Buonincontri, P.; van Niekerk, M.; Orlowski, M.; Okumus, F. Exploring the role of next-generation virtual technologies in destination marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernuszenko, M.; Pape, D.; Sandin, D.; DeFanti, T.; Dawe, G.L.; Brown, M.D. The ImmersaDesk and Infinity Wall projection-based virtual reality displays. SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 1997, 31, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.H.; Lee, H.; Chung, N.; Tom Dieck, M.C. Cross-cultural differences in adopting mobile augmented reality at cultural heritage tourism sites. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1621–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Piscarac, D.; Yoo, S.C. Meet the virtual jeju dol harubang—The mixed VR/Ar application for cultural immersion in Korea’s main heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Timms, K.M.; Schaffer, V.; Skavronskaya, L.; Little, C. Management of immersive heritage tourism experiences: A conceptual model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C. From Territory to Smartphone: Smart Fruition of Cultural Heritage for Dynamic Tourism Development. Plan. Pract. Res. 2014, 29, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Ilardi, E. The “Non-Places” Meet the “Places”: Virtual Tours on Smartphones for the Enhancement of Cultural Heritage. J. Urban Technol. 2014, 21, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Pino-Mejías, M.Á. The impact of virtual reality technology on tourists’ experience: A textual data analysis. Soft. Comput. 2020, 24, 13879–13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. In Proceedings of the MindTrek ’11: Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.; Auer, E.; Collmus, A.; Armstrong, M. Gamification science, its history and future: Definitions and a research agenda. Simul. Gaming 2018, 49, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growthengineering. The Ultimate Definition of Gamification (with 6 Real World Examples). Available online: https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/definition-of-gamification/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Xu, F.; Buhalis, D.; Weber, J. Serious games and the gamification of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdani, D.; Fanini, B.; Piccioli, M.C.; Carboni, F.; Vigliarolo, P. 3D reconstruction and validation of historical background for immersive VR applications and games: The case study of the Forum of Augustus in Rome. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 43, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liarokapis, F.; Petridis, P.; Andrews, D.; De Freitas, S. Multimodal serious games technologies for cultural heritage. In Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage; Ioannides, M., Magnenat-Thalmann, N., Papagiannakis, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, S.; Duguleana, M.; Brondi, R.; Florin, G.; Postelnicu, C.; Carrozzino, M. An interactive haptic system for experiencing traditional archery. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2018, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccacci, S.; Generosi, A.; Leopardi, A.; Mengoni, M.; Mandorli, A.F. The role of haptic feedback and gamification in virtual museum systems. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augello, A.; Infantino, I.; Pilato, G.; Vitale, G. Site experience enhancement and perspective in cultural heritage fruition—A survey on new technologies and methodologies based on a “four-pillars” approach. Future Internet 2021, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammady, R.; Ma, M.; Temple, N. Augmented Reality and Gamification in Heritage Museums; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 9894, pp. 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Paliokas, I.; Patenidis, A.T.; Mitsopoulou, E.E.; Tsita, C.; Pehlivanides, G.; Karyati, E.; Tsafaras, S.; Stathopoulos, E.A.; Kokkalas, A.; Diplaris, S.; et al. A Gamified Augmented Reality Application for Digital Heritage and Tourism. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavec, A.; Sajincic, N.; Starman, V. Use of smartphone cameras and other applications while traveling to sustain outdoor cultural heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, S.; Styliaras, G.; Bassounas, A. Revealing hidden local cultural heritage through a serious escape game in outdoor settings. Information 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujari, A.; Ciman, M.; Gaggi, O. Using gamification to discover cultural heritage locations from geo-tagged photos. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2017, 21, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlizos, S.; Sharamyeva, J.-A.; Kotsopoulos, K. Interdisciplinary Design of an Educational Applications Development Platform in a 3D Environment Focused on Cultural Heritage Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelidis, K.; Sylaiou, S.; Papadopoulos, T. Mergin’ Mode: Mixed Reality and Geoinformatics for Monument Demonstration. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, S.; Andone, D.; Ternauciuc, A.; Mihaescu, V.; Rotaru, O.; Mocofan, M.; Orhei, C.; Vasiu, R. User evaluation of a multi-platform digital storytelling concept for cultural heritage. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.J.; Ma, X.J. ShadowPlay2.5D: A 360-degree video authoring tool for immersive appreciation of classical Chinese poetry. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofresa, R.S.; Xirau, M.T.; Ereddam, H.E.B.; Vicente, O. Gamification and Cultural Heritage; UAB Research Park: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tisserand, Y.; Magnenat-Thalmann, N.; Unzueta, L.; Linaza, M.T.; Ahmadi, A.; O’connor, N.E.; Zioulis, N.; Zarpalas, D.; Daras, P. Preservation and gamification of traditional sports. In Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage; Ioannides, M., Magnenat-Thalmann, N., Papagiannakis, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, H.; Beisswenger, C.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Adami, I.; Zidianakis, E.; Patakos, A.; Patsiouras, N.; Karuzaki, E.; Foukarakis, M.; et al. Multimodal narratives for the presentation of silk heritage in the museum. Heritage 2022, 5, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Melo, M.; Bessa, M. A survey of multisensory vr and ar applications for cultural heritage. Comput. Graph. 2022, 102, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Lu, W.; Wang, M.; Chen, H. Research on Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection Based on Augmented Reality Technology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1574, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Digital protection method of intangible cultural heritage based on augmented reality technology. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Robots & Intelligent System (ICRIS), Huai An, China, 15–16 October 2017; pp. 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhao, R. Research on Combination of Intangible Cultural Heritage and Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences ans Humanities, Moscow, Russia, 14–15 June 2017; Book Series: Advances in Social Science Education and Humanities Research, Tretyakova. Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 124, pp. 536–538. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. MUSE: Understanding traditional dances. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 29 March–2 April 2014; pp. 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziagkas, E.; Stylianidis, P.; Loukovitis, A.; Zilidou, V.; Lilou, O.; Mavropoulou, A.; Douka, S. Greek traditional dances 3d motion capturing and a proposed method for identification through rhythm pattern analyses (terpsichore project). In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism: Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Kavoura, A., Kefallonitis, E., Theodoridis, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, J. Intangible cultural heritage display using augmented reality technology of Xtion PRO interaction. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 29.1–29.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Tang, X. The application of augmented reality technology in digital display for intangible cultural heritage: The case of cantonese furniture. In Human-Computer Interaction. Interaction in Context; Kurosu, M., Ed.; HCI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10902, pp. 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička-Medin, G. The Materiality of Interaction & Intangible Heritage: Interaction Design. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO), Budva, Montenero, 10–14 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xiang, H.; Li, S. The application of augmented reality and unity 3D in interaction with intangible cultural heritage. Evol. Intell. 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viinikkala, L.; Yli-Seppälä, L.; Heimo, O.I.; Helle, S.; Härkänen, L.; Jokela, S.; Lehtonen, T. Reforming the representation of the reformation: Mixed reality narratives in communicating tangible and intangible heritage of the protestant reformation in Finland. In Proceedings of the 2016 22nd International Conference on Virtual System & Multimedia (VSMM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–21 October 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europeana: Discover Inspiring European Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://www.europeana.eu (accessed on 6 July 2022).

| Pos | Author Keywords | Total | AGR | ADY | PDLY | h-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3D reconstruction | 155 | −6.5 | 14.5 | 18.7 | 12 |

| 2 | Digital heritage | 107 | −2.5 | 14.5 | 27.1 | 11 |

| 3 | Virtual museums | 78 | −5.0 | 8.5 | 21.8 | 14 |

| 4 | User experience | 63 | −2.5 | 10.5 | 33.3 | 10 |

| 5 | Education | 60 | −2.5 | 5.5 | 18.3 | 12 |

| 6 | Tourism | 48 | −0.5 | 7.5 | 31.2 | 10 |

| 7 | Intangible cultural heritage | 40 | −2.0 | 5.5 | 27.5 | 5 |

| 8 | Gamification | 39 | −1.0 | 2.0 | 10.3 | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boboc, R.G.; Băutu, E.; Gîrbacia, F.; Popovici, N.; Popovici, D.-M. Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199859

Boboc RG, Băutu E, Gîrbacia F, Popovici N, Popovici D-M. Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(19):9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199859

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoboc, Răzvan Gabriel, Elena Băutu, Florin Gîrbacia, Norina Popovici, and Dorin-Mircea Popovici. 2022. "Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications" Applied Sciences 12, no. 19: 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199859

APA StyleBoboc, R. G., Băutu, E., Gîrbacia, F., Popovici, N., & Popovici, D.-M. (2022). Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications. Applied Sciences, 12(19), 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199859