Abstract

Malware is a significant threat that has grown with the spread of technology. This makes detecting malware a critical issue. Static and dynamic methods are widely used in the detection of malware. However, traditional static and dynamic malware detection methods may fall short in advanced malware detection. Data obtained through memory analysis can provide important insights into the behavior and patterns of malware. This is because malwares leave various traces on memories. For this reason, the memory analysis method is one of the issues that should be studied in malware detection. In this study, the use of memory data in malware detection is suggested. Malware detection was carried out by using various deep learning and machine learning approaches in a big data environment with memory data. This study was carried out with Pyspark on Apache Spark big data platform in Google Colaboratory. Experiments were performed on the balanced CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. Binary classification was made using Random Forest, Decision Tree, Gradient Boosted Tree, Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, Linear Vector Support Machine, Multilayer Perceptron, Deep Feed Forward Neural Network, and Long Short-Term Memory algorithms. The performances of the algorithms used have been compared. The results were evaluated using the Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, Recall, and AUC performance metrics. As a result, the most successful malware detection was obtained with the Logistic Regression algorithm, with an accuracy level of 99.97% in malware detection by memory analysis. Gradient Boosted Tree follows the Logistic Regression algorithm with 99.94% accuracy. The Naive Bayes algorithm showed the lowest performance in malware analysis with memory data, with an accuracy of 98.41%. In addition, many of the algorithms used have achieved very successful results. According to the results obtained, the data obtained from memory analysis is very useful in detecting malware. In addition, deep learning and machine learning approaches were trained with memory datasets and achieved very successful results in malware detection.

1. Introduction

Technology is developing day by day and its usage rate is increasing. This shift in technology also provides an environment for malware to spread. According to the statistics of the AV-test institute, 470.01 million malwares were detected in 2015, while this number reached 1312.54 million in 2021. In the first quarter of 2022, approximately 30 million new malwares were detected [1]. This requires the development of various methods to deal with malware.

The malware must go through a forensic process for its purpose to be discovered. Signatures of malicious software are created from the findings obtained at the end of this process and can be used to protect against malware threats [2]. Analysis of malware is generally divided into static and dynamic. In static analysis, analyses are performed by deriving some features from the file such as API calls, control flow graphs, opcodes, and n-grams. Dynamic analysis, on the other hand, is performed by running malware in an isolated environment using behavioral features such as performance counters, opcodes, and memory access patterns. [3,4]. There are also hybrid methods in the literature in which the two methods are used together [4]. However, both static and dynamic analysis methods have some limitations. Static analysis is effective on malware samples with known signatures. However, it cannot show the same effect on emerging malware. In the dynamic analysis approach, running each suspicious sample imposes a burden in terms of time and computing resources. Some advanced malwares can hide themselves by hiding from the virtual server [5].

Memory analysis can overcome the limitations of static and dynamic analysis methods. With memory analysis, the limitations of malware signatures created as a result of static analysis can be overcome. Memory-based features can also overcome some dynamic analysis limitations such as hidden behavior of malwares during analysis. Although memory analysis is basically a static analysis, it is a known fact that new generation malware does not exhibit some behaviors during static analysis. However, since such hidden behaviors can be detected with memory analysis, it provides significant gains in malware detection compared to traditional static analysis. Malware leaves some traces in memory [6]. With memory analysis, some information about the behavioral characteristics of malware can be obtained using information such as terminated processes, DDL records, registries, active network connections, and running services [7]. Memory analysis work consists of two stages, memory acquisition and memory analysis. Memory acquisition is the stage of obtaining a full image of the machine memory. Memory analysis is the phase of examining and analyzing the movements of malware, usually using a forensic memory tool [8]. In this way, it becomes possible to detect hidden malware with memory analysis.

Analysis of malware data can often be considered in the context of big data. [3]. In malware analysis, the data to be examined is heterogeneous and large in volume. At the same time, it is necessary to work with streaming data to determine whether a suspicious activity is caused by malware. This requires the use of big data technologies in malware detection. In addition, machine learning methods are one of the most widely used techniques to automatically learn the patterns and behavior patterns they leave behind while detecting malware [9]. The deep learning method is another classification method used recently.

In this study, a classification has been made on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset, which includes hidden malware families obtained by memory analysis. The study was carried out using Apache Spark big data platform on Google Colaboratory. Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), Gradient Augmented Tree (GBT), Logistic Regression (LR), Naive Bayes (NB), Linear Support Vector Machine (Linear SVC), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) data for binary classification set), Deep Neural Network (DNN), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) were the nine different machine learning and deep learning methods used. Results were evaluated with Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, Recall, and AUC performance metrics.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- It has been shown through the study that malware detection can be performed using memory data.

- (2)

- This study provides a basis for future studies on the analysis and classification of memory data with the big data approach.

- (3)

- Another contribution of the study is that various deep learning and machine learning approaches, which are frequently used in many intrusion detection systems in the literature and are very popular, have been confirmed to achieve successful results in memory data malware detection.

- (4)

- The memory data and malware detection performance of nine different machine learning and deep learning algorithms were compared. The results will guide researchers about the techniques to be preferred in future studies.

The rest of the study is organized as follows. Related studies are given in Section 2. Information on the malware families included in the dataset is in Section 3. In Section 4, the materials and methods used in the study are mentioned. In Section 5, model parameters and experimental results are given. Finally, Section 6 presents the results obtained.

2. Related Works

Malware attacks are increasing day by day and becoming more complex. Therefore, malware detection has become more and more imperative. Thus, studies based on static, dynamic, and memory analysis in detecting malicious software are gaining popularity in the literature. Many different malware detection techniques have been proposed using these 3 different approaches. In this section, some malware techniques using these approaches in the literature are presented.

One of the studies is the study to detect malware based on behavior by comparing memory data by Aghaeikheirabady et al. [10]. They used data in user space and multiple memory structures simultaneously. In this way, fast information extraction and high accuracy rates are the aim. When the approach was tested with machine learning, Naive Bayes provided the best performance with 98.9%. Another of these studies is AMAL, a behavior-based malware classification and clustering system presented by Mohaisen et al. [11]. AMAL consists of two subsystems. AutoMal extracts low-granularity behavioral features on the file system, memory, network, and registry. MaLabel performs the function of vectorizing extracted features and generating classifiers. According to the study, AMAL provides 99.5% precision in classifying certain families. Mosli et al. [5] conducted a study to detect malware by extracting Registry, DLLs, and APIs from memory images. It compared malware detection performances using machine learning algorithms. By using the SVM classifier on the Registry feature, an accuracy rate of 96% was obtained. In another study, Ahmadi et al. [12] focused on the impact of feature extraction and selection stages in malware classification. Grouping and weighting of malwares according to their behavioral characteristics is emphasized. Rathnayaka and Jamdagni [6] proposed a framework for malware detection by integrating static and memory analysis methods. The authors mention that the proposed framework achieves 90% accuracy in malware detection.

Considering memory data, Kumara and Jaidhar [13] presented a volatile memory introspection system called A-IntExt based on Virtual Machine Monitor. The system has been developed with Virtual Machine Introspection, Forensic Memory Analysis, and machine learning methods. Their aim is to provide early diagnosis in malware detection with this system. The system has reached an accuracy rate of 99.55% in the evaluations made with the dataset. Mosli et al. [14] performed a behavior-based automated malware detection using forensic memory analysis and machine learning techniques. In the study, an accuracy rate of 91.4% was obtained in the tests performed with malware and benign samples. Petrik et al. [15] performed malware detection with only binary raw data from memory dumps of devices. It had the characteristics of being independent from the operating system and architectural structure. The authors mention that over 98% accuracy rates were achieved when various machine learning and CNN algorithms were applied. Nissim et al. [16] conducted a study based on memory data to detect remote access trojans and ransomware for virtual servers provided in cloud computing environments. In this study, temporary memory dumps were analyzed with the MinHash method, which is a similarity classification method. Vipasana, TeslaCrypt, Chimera, Cerber, Hidden Tear ransomware families, and DarkComet, Pandora, SpyGate, Comet, and Babylon remote access Trojan families were used in the experiments. In comparison with machine learning-based classifiers, 100% TPR rate and a very low FPR rate were achieved for both malwares. Banin and Dyrkolbotn [3] investigated the effect of memory access data on malware detection over time. Machine learning models were trained with old samples and their ability to detect new malware was evaluated. Yucel and Koltuksuz [2] have introduced an approach for extracting memory access images to detect the activities of malware. A dataset containing 24 different malware families and 6 benign executable files belonging to four malware categories was used. Malware samples from the same family are shown in 3D space according to the computational instruction sequence, the instruction address, and the accessed memory address, and their similarity ratios are compared. Lashkari et al. [17] have worked to extract the most important features from memory dumps to detect malware. For this, they have developed a tool called VolMemLyzer. Thirty-six features belonging to nine categories were extracted using VolMemLyzer. The tool has been tested on 1900 memory dumps with machine learning methods. As a result of the study, a 93% True-Positive (TP) rate was obtained. However, the authors emphasized that the number of malwares was low, which limited the study. The authors increased the malware samples, resulting in the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset.

In addition, Severi et al. [18] presented a new platform by addressing the shortcomings and disadvantages of existing malware analysis systems. Using the platform they call Malrec, they aimed to capture the traces of the entire system and to provide replayability. The authors presented a new dataset and wanted to demonstrate that it met the goal of high accuracy by performing a test with DNN on this dataset. In the study by Kang et al. [19], a word2vec-based LSTM approach was proposed for malware classification by analyzing API functions. Better performance was obtained than other vector size reduction methods in the evaluations. Safa et al. [20] studied the performance of deep learning techniques in malware classification. In this study, LSTM, GRU, and CNN algorithms were compared in static and behavior-based malware detection. At the same time, a hybrid CNN and LSTM model has been developed. The proposed hybrid model achieved a higher success rate than other models with an accuracy rate of 99.31%. In another study, Lu et al. [21] carried out a study to detect malware with a combination of machine learning and deep learning methods. In this study, features were extracted with Random Forest and API call sequences were preprocessed with LSTM. It has been shown that 96.7% accuracy rate in malware detection is achieved with the consolidated framework. In another study, Sung et al. [22] worked on malware detection in drones and GCSs. An approach is presented that includes the low-dimensional vector generating fastText model and Bi-LSTM. Panker and Nissim [23] presented an approach for detecting malware in Linux VM environments. In the study, 53 malware family samples were used in nine malware categories. Using various machine learning and deep learning algorithms, seven experiments were performed on volatile memory data from HTTP and DNS servers. A study by Sihwail et al. [7] proposes an approach for malware detection and classification using memory features extracted from memory images. Using Volatility, they extracted six different memory features. In the classification mode, it achieved an accuracy rate of 98.5% and an FPR rate of 1.24%. In addition, evaluations were made with feature selection methods, and it was revealed that DLL features have a higher weight than other memory features. One of the studies to classify malware without signature is presented by Diaz and Bandala [24]. In the study, classification was made on PE files with LSTM and LightGBM algorithms. In classification, they aimed to perform dynamic analysis with LSTM. On the other hand, LightGBM was preferred because it creates less burden on resources. According to the evaluations, the proposed model has achieved an accuracy of 91.73%. Wang and Qian [25] presented a textual CNN method called textCNN to detect malicious code families. The performance of the method has been evaluated on two different datasets. Finally, a recent study by Arfeen et al. [26] proposes a framework that provides periodic memory dumping for comprehensive and accurate analysis. WannaCry, HiddenTear, Cerber, TeslaCrypt, and Vipasana ransomware were used in the development of the framework. With the proposed framework, binary classifications were made on the dataset using the XGBoost algorithm. As a result, 88% accuracy was achieved in ransomware.

Rezende et al. [27] focused on malware detection on grayscale images. With the proposed ResNet-50 architecture, an accuracy rate of 98.62% has been achieved. Ni et al.’s [28] work proposes a method called MCSC that performs classification based on static properties. Accordingly, grayscale images are created with SimHash and classification is performed with CNN. The proposed method has achieved accuracy rates of up to 99.26%. Dai et al. [29] proposed a malware detection approach in which memory images are extracted and converted to fixed-size grayscale images. The features were extracted from the images with HOG. Malware has been classified using extracted features. In the classifications made, 95.2% accuracy was obtained with the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) algorithm. In another study, Li et al.’s [30] study addressed the additional runtime overhead of dynamic analysis in malware detection in the cloud. To solve this problem, it introduced a deep learning-based memory analysis and malware detection approach. Snapshots were extracted and converted to grayscale images. CNN was used to detect malware. Dai et al. [31] proposed a community learning approach that uses software and hardware features such as API feature set, grayscale memory dump image, and hardware performance counter. It used a neural network as a detector to detect malware. Focusing on malware detection on images, Wong et al. [32] proposed a layer using the ECOC-SVM configuration. In the proposed model, features obtained by transfer learning using ShuffleNet and DenseNet-201 were combined in an average pooling layer. The model has been tested on four different malware datasets and the results have been compared. As a result, it has been shown that class distinctions can vary depending on the datasets and it is difficult to generalize the ECOC coding matrix. In Bozkir et al.’s [33] study, memory dumps of suspect states that could be represented as RGB images were obtained and classified. Ten malware families were used in the study. Memory dumps obtained using GIST and HOST identifiers were signed. Signatures were compared with machine learning-based classifiers. The SMO algorithm achieved 96.39% accuracy in the feature vectors obtained with the combination of GIST and HOST. In addition, the accuracy of malware detection methods had increased with the UMAP-based manifold learning strategy. Hemalatha et al. [34] treated the malware binaries as two-dimensional images. A deep learning-based malware classification model was proposed by addressing the problem of unstable data with DenseNet. The method was evaluated on four different datasets. It has been observed that the proposed method reduces the FP rate. Tekerek and Yapici [35] made a malware classification by converting byte files to RGB and grayscale image files, with the CNN approach it proposed. At the same time, a new data augmentation method was presented, with an emphasis on the problem of unevenly distributed malware family samples. The method was tested with two different datasets and 99.86% and 99.60% accuracy rates were obtained.

Awan et al. [36] proposed a deep learning framework based on spatial attention and CNN called SACNN. Twenty-five different malware families have been classified with the image-based classification process. The authors also addressed the problem of class imbalance. In the study, performance evaluations were made on the Malimg dataset and very successful results were obtained. Yadav et al. [37] present a comparison of 26 different pre-trained CNN models for Android malware detection. Eight different models were used in the study, namely VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, DenseNet121, DenseNet169, and EfficientNetB4. In addition to these models, the performances of SVM and RF classifiers were also evaluated. The proposed method achieved 97% accuracy in binary classification. Damaševičius et al. [38] proposed an ensemble classification-based methodology for malware detection. The first stage is fully connected and is handled by CNN, while the final classification is handled by meta-learner. The performance of 13 different machine learning systems were compared in the study. Experimental studies were carried out on the Classification of Malware with PE headers (ClaMP) dataset. The best performance was obtained by using the 5 dense and CNN in the first stage and the ExtraTrees classifier in the last stage. Azeez et al. [39] proposed an ensemble-learning method for malware detection. In the proposed method, the base stage consists of a fully connected and 1D CNN network, while the end stage consists of a machine learning algorithm. The authors compared the performance of 15 different machine learning methods as a meta-learner. Experimental studies were carried out on the Windows Portable Executable (PE) malware dataset.

As seen in related works, studies focus on extracting memory dumps and detecting malware using them. In the studies, malware classification was made using various machine learning and deep learning algorithms. However, these classifications were made with one or more specified algorithms. In this study, nine different machine learning and deep learning methods were applied for malware detection on memory dumps. In this way, the classification performance of many methods was compared. Unlike the related studies, a balanced memory analysis dataset was used. In addition, the studies were carried out on the big data platform. As a result of the study, very high accuracy rates were determined.

Table 1 provides summaries of studies focusing on malware detection in the literature by best or recommended models, datasets, samples, and accuracy rates. Accordingly, it is seen in the literature that various machine learning and deep learning approaches are used in malware detection studies. Different datasets are used to test the proposed methods in the studies. In studies focusing on malware detection with memory forensics, it is seen that, generally, malware and benign samples collected from repository are used. In our study, the CIC-Malmem-2022 dataset based on memory analysis features was used. In this study, a higher accuracy rate was obtained with the balanced CIC-Malmem-2022 dataset compared to other studies.

Table 1.

Comparison of other works on Malware Detection.

3. Malware Families

Malware is software that is programmed to perform harmful, illegal, and unwanted activities on a system [2]. Malware can be classified in several ways, such as Trojan, virus, worm, ransomware, rootkit, spam, and spyware. The dataset used in this study contains malware samples belonging to three different malware categories. The malware categories mentioned are Trojan horse, spyware, and ransomware.

Trojan Horse: Programs that appear harmless to users but carry out malicious software activities in the background. The first known Trojan horse is a question-and-answer game called Animal, created in 1974. This game had users choose an animal name and pose questions to guess the animal’s name. In the background, it was copying itself to all directories that the user had written access to, without authorization [40]. There is no limit to what Trojan horses can do nowadays. New Trojan horse families are emerging every day. Five types of Trojan horses are described in this study:

- Zeus: It is also known as Zbot. It first appeared in 2007. It is a type of banking Trojan that is used to steal banking credentials via keylogging. Another important function is to create a botnet by communicating with the C&C server. In the years after its emergence, open-source code was shared and new versions such as Citadel, GameoverZeus, Ice IX, and KINS were created [41].

- Emonet: It is a Trojan horse that first appeared in 2014. It is a banking malware designed to snatch sensitive information by sniffing the network. In the years after its emergence, it has been transformed into a platform that allows other malware to be installed. It has capabilities such as creating and organizing botnets. It also has some worm properties to propagate [41].

- Refroso: It is a Trojan horse with a backdoor function that first appeared in 2009. It can change the settings of the firewall by deleting the registry entries. It can start and hide memory processes. It can perform some activities such as redirecting to malicious websites and hiding unwanted activities in the browser. It can assist access attacks by providing a configuration that allows outside access.

- Scar: It is a Trojan horse that allows different malware to be installed on the device it infects. It downloads a list of URLs that link to files with the exe extension to allow malware to download more. It can also perform operations such as collecting confidential information on the device and changing operating system settings.

- Reconyc: It is a Trojan horse that does the downloading different malware on the device it infects. Like most malware, it is distributed from untrusted websites or as an attachment to another file. It also can limit access to some important tools in the operating system such as Command Prompt, Task Manager, and Registry Editor.

Spyware: They are malware that secretly record user information and movements and transfer it to third parties. They usually collect information about the user’s browsing habits and activities. This study describes the five types of spyware included in the dataset:

- 180Solutions: It is spyware, also known as Zango. It monitors some activities on the Internet such as user movements, URLs visited, and cookies. It serves pop-ups and targeted advertisements using the information it collects.

- CoolWebSearch (CWS): It is a browser hijacker first seen in 2003. It transfers sensitive data collected through the browser to networks associated with CoolWebSearch. It has several versions with different techniques such as DataNoter, BootConf, PnP, Winres, SvcHost, and MSInfo. These versions perform different functions such as monitoring access to certain websites, ensuring that CoolWebSearch does not appear on the whitelist, and downloading adware.

- Gator: It is adware, also known as Gain AdServer. It can replicate itself by pretending to be a virus. It can also download other spyware programs and perform updates. Like other adware, it tracks user movements and delivers targeted ads and pop-ups. Gator can cause memory wear by taking up a lot of hard disk space.

- Transponder: It is spyware. It installs as a Browser Helper Object (BHO) distributed with third-party software. At its initial setup, it collects information about the device and user ID. Then, it monitors some activities such as user movements, URLs visited, cookies, etc., and transfers them to the server. It is also software that creates pop-up banners.

- TIBS: It is a malware known as TIBS dialer. It is spread through email attachments and unreliable websites. It makes paid calls to adult websites using the modem. It runs in the background of the device it has infected and does not affect its performance. It is manifested by abnormal situations such as uncontrollable connections, unwanted downloads, and hidden internet connections.

Ransomware: It is a type of malware that aims to obtain funds directly from the user [40]. It restricts user access by encrypting disks, files, or various data on the device. A fee is required from the user to remove the password. However, paying the specified ransom does not always guarantee that the encrypted data can be accessed again. Ransomware is one of the growing problems nowadays. This study describes the five types of spyware included in the dataset:

- Conti: A ransomware that emerged in 2020 that infiltrates local or networked drives via phishing email. When clicked, it downloads Bazar backdoor and IcedID Trojan horse to target machines. Encrypts SMB-type files with AES-256 using up to 32 logical threads. It ignores files with dll, exe, lnk, and sys extensions during encryption. It deletes shadow copies of encrypted files and prevents them from being uploaded again.

- Maze: It appeared in 2019. Maze is distributed via phishing emails that distribute malicious macros with docx extension attachments, or by vulnerable networks such as RDP servers, and Citrix/VPN servers. It is also distributed as a PE binary (dll, exe). It uses ChaCha20 stream ciphers and RSA-2048 public encryption keys to encrypt files. For this reason, it is also known as ChaCha ransomware. The creators of Maze publish some of their encrypted documents on their websites.

- Pysa: It is a type of ransomware that appeared in 2018 and cannot spread on its own. It is also known as Mespinoza. Phishing emails infiltrate machines by performing Brute Force attacks against RDP servers and Active Directory. It uses a hybrid encryption method created with AES-CBC and RSA algorithms. It stores the encrypted files with the Pysa extension. It deletes shadow copies of encrypted files and prevents them from being uploaded again.

- Ako: It is ransomware that infiltrates the machine with a phishing email that emerged in 2020. It is also known as MedusaReborn. It is distributed with an encrypted zip file. It is propagated by the src file in the folder. It encrypts files other than exe, dll, sys, ini, lnk, key, and rdp files using MD5, SHA-1, and SHA-256. It drops a text containing the ransom note and a folder named “id.key” containing the encryption key on the target desktop.

- Shade: It is ransomware that was first seen in 2019 and infiltrated the machine via phishing email. Also known as Troldesh. Shade is distributed in a zip file written in Javascript. It uses two separate keys generated with AES-256 in CBC mode to encrypt the content and filename of each file. It is also known for leaving notes with a large number of different extensions on the computer is infected.

4. Material and Methods

In this section, firstly, information about Apache Spark big data platform is given. Then, the dataset used in the study is introduced. The preprocessing steps performed are mentioned. Finally, information about machine learning and deep learning methods used in classification is given.

Apache Spark [42] is an open-source project designed to process big data in parallel. Apache Spark is developed in the Scala language. Its basic structure is Resilient Distributed Dataset (RDD). RDDs are distributed, flexible, and fault-tolerant structures. Apache Spark does in-memory data processing. Thanks to this feature, it can process faster than MapReduce running on disk. Apache Spark consists of Spark Core, Spark SQL, Spark Streaming, MLlib, and GraphX components. Spark Core is the structure on which all components are built. Spark SQL, Spark Streaming, MLlib, and GraphX are the most important libraries of Apache Spark. Spark SQL processes structured data while Spark Streaming is used for the analysis of real-time data. MLlib is Spark’s machine learning library. Graph and network analyses are performed with the GraphX library. These libraries can be used together in a single project. Spark has multi-language support for realizing projects. Applications can be made on Spark using Scala, Java, Python, and R languages. Apache Spark can use Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) for storage and can be integrated with many big data technologies.

4.1. Dataset

The CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset [43] used in this study was made available by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity in 2022. The dataset is designed to test obfuscated malware detection methods using memory dumps. CIC-MalMem-2022 is a balanced dataset with a total of 58,596 records. Of the records that it contains, 29,298 are benign and 29,298 are malicious. The malicious memory dump was created by executing software samples collected from VirusTotal on a VM with 2GB memory. Next, normal behavior was collected by running applications on the machine to generate a bona fide memory dump [44]. The dataset contains three different types of malwares: Spyware, Ransomware, and Trojan. As seen in Table 2, there are samples of 15 different malware families in the dataset.

Table 2.

Detailed explanation of the attributes of the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset.

In addition, the dataset contains 57 attributes that contain traces of these malware families in memory. These attributes are seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Malware samples used in the classification training and testing.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

To make the dataset suitable for classification, some preprocessing steps are required. These processes are important to improve the efficiency of classification models, as well as to bring the data into a suitable format for the use of machine learning and deep learning algorithms. In addition, some data balancing operations are performed against the overfitting problem, especially in deep learning approaches. However, the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset used in the study is a balanced dataset and consists of two classes, benign and malware. It is a dataset that is resistant to the overfitting problem because the dataset is balanced. Therefore, no action was taken for the overfitting problem in the study. In this study categorical class values were converted to numerical values using Label Encoder. With the Label Encoder process, each categorical value is randomly assigned to a different numerical value, starting from zero. In this study, Benign and Malware categorical values are assigned to two different values, 0 and 1, to make them ready for machine learning and deep learning algorithms, and the numeric labels of the classes are seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Class name and numeric labels.

Another preprocessing step is to remove features that do not have any impact on the performance of machine learning and deep learning algorithms from the dataset. These operations are generally called feature selection. For this purpose, “pslist.nprocs64bit”, “handles.nport” and “svcscan.interactive_process_services” features that have zero values in the dataset and do not have any effect on the results of the learning algorithms that have been removed from the dataset. In addition, the “Category” feature in the dataset provides information about malware families. This feature is unnecessary for binary classification. However, it can be used in multiclass classification studies. As a result, the number of features in the dataset, which was 57 in the feature selection preprocessing stage, was reduced to 52. This step also prevents unnecessary resource consumption.

In this study, normalization was performed as the last preprocessing step. The normalization process applied in the study is formulated with Equation (1). The normalization process reduces numeric values to the range 0–1. In this way, the performance of algorithms is improved by reducing the difference between numerical values.

where o is the original value, is the normalized value, and μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation values, respectively.

4.3. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms

As the complexity and size of datasets increase, detection of malware becomes more difficult. In the literature, machine learning algorithms are widely used to analyze such complex data, extract patterns, and develop technologies in parallel with the development of malware [9]. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms create classification models using extracted features. They then use these models to classify new entries. Generally, the accuracy of the classification predictions represents the success of the algorithm. In this study, two-class classification models, malicious and benign, were established by using the nine different algorithms mentioned below.

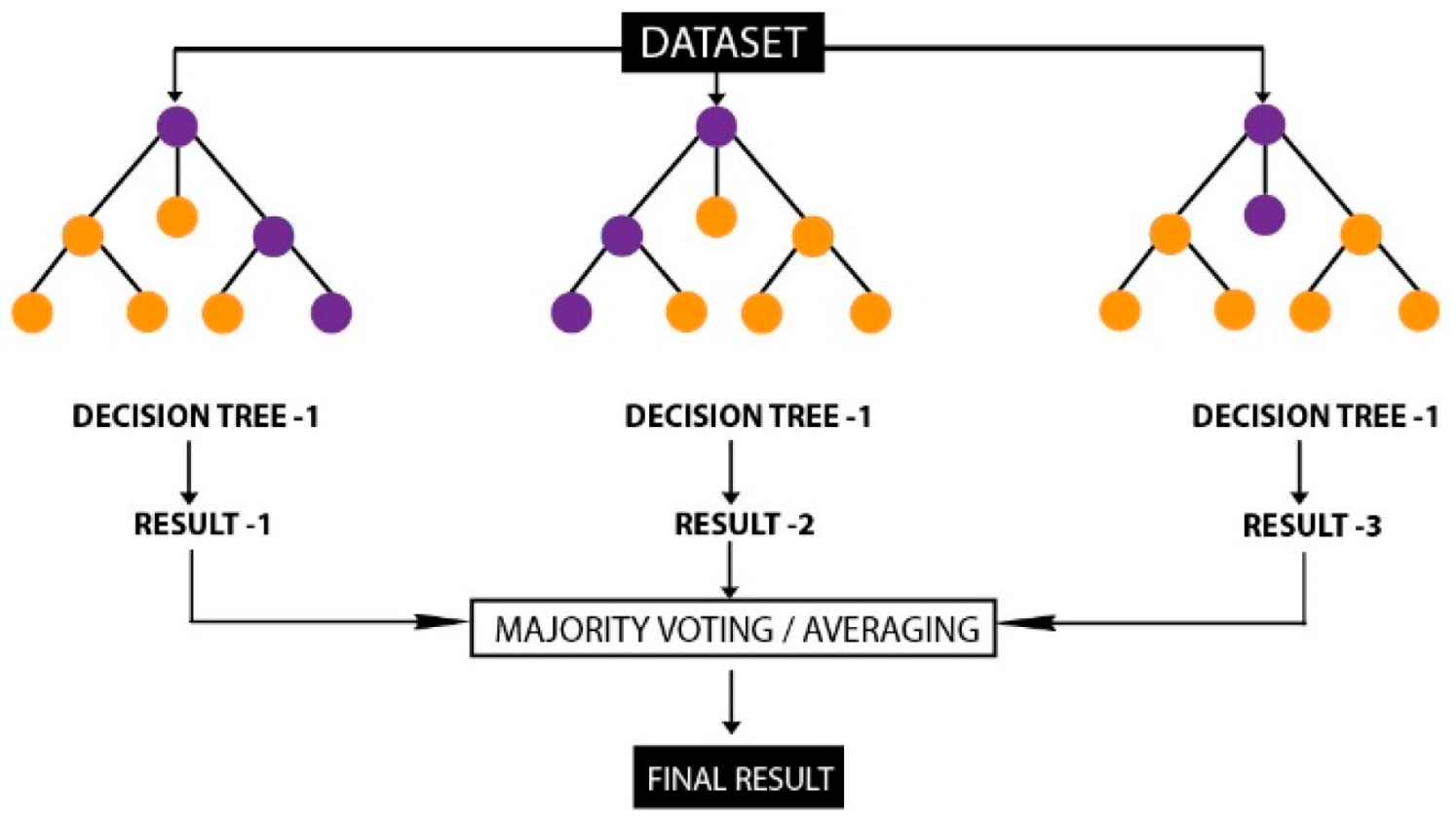

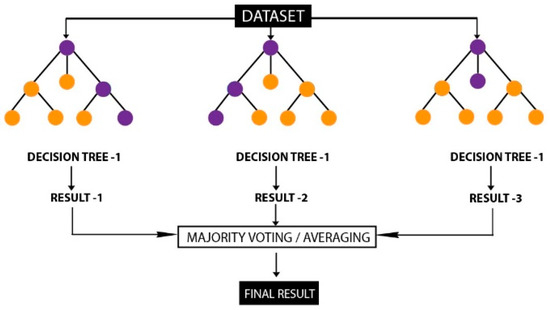

Random Forest (RF): Random Forest is a supervised ensemble algorithm introduced by Breiman [45]. It is based on the bagging technique. As seen in Figure 1, it is formed by the combination of multiple decision trees, which are created by choosing random samples. The majority vote is calculated by averaging the results of all decision trees. The final decision is made by a majority vote [46]. Increasing the number of trees (depth) improves accuracy. It is an algorithm that is resistant to the overfitting problem.

Figure 1.

Random Forest Structure.

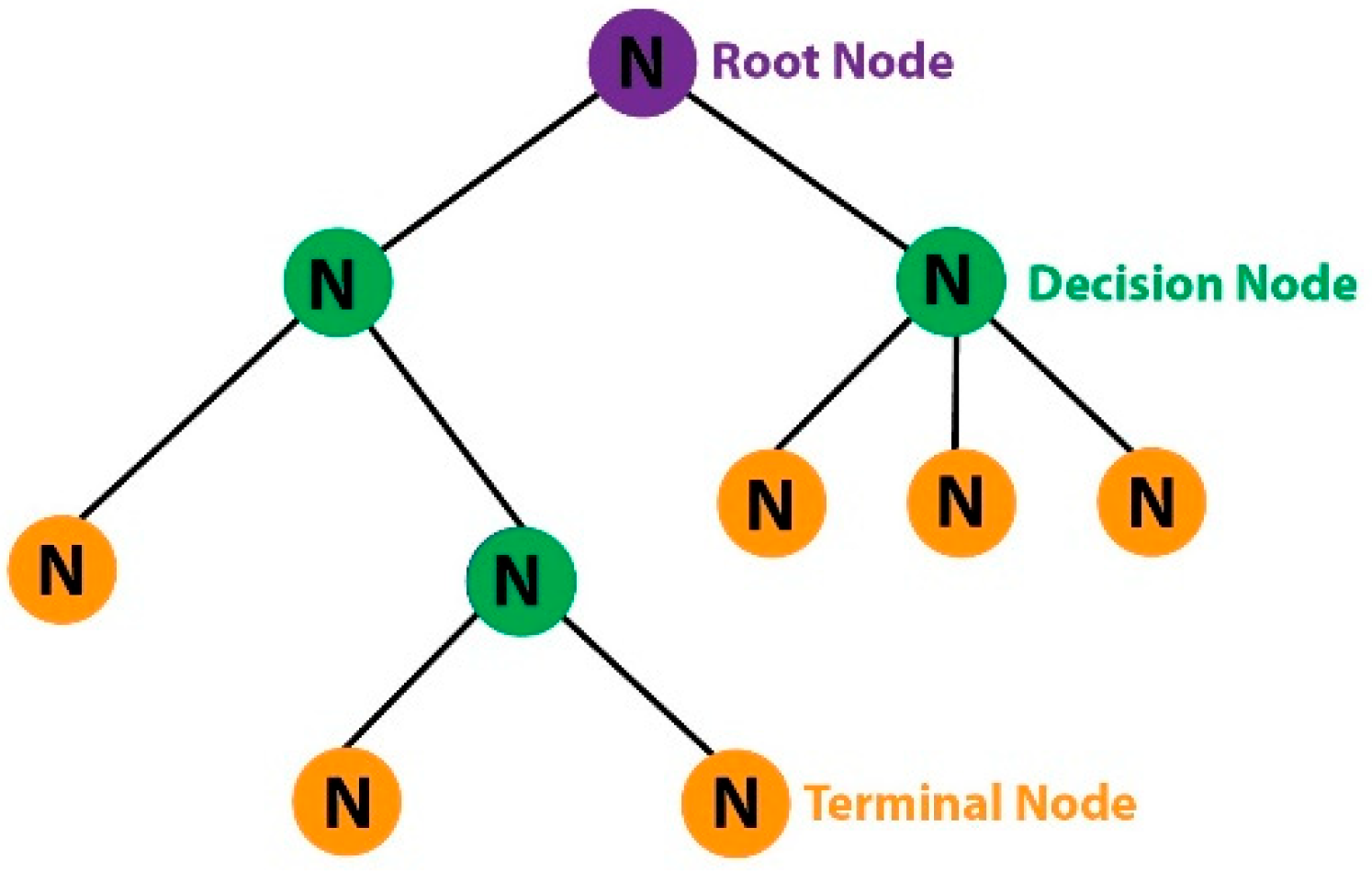

Decision Tree (DT): It is a supervised learning algorithm used for classification and regression. As seen in Figure 2, it is a rooted tree model that tests an attribute at each node. Each branch and leaf carry a class label. Attribute values are classified by moving from the root node to the leaf nodes. At each step, a model that predicts classes is created with the decision rule created based on the attributes [45,47]. Decision trees are an algorithm that are easy to understand and interpret. It is a frequently used machine learning algorithm in the literature. Some of the most well-known decision tree examples are ID3, J48, CART, and C4.5. In this study, CART was used as tree type in both Decision Tree algorithm and Random Forest algorithm.

Figure 2.

Decision Tree Structure.

Naive Bayes (NB): It is a supervised machine learning algorithm based on Bayes’ theorem. It calculates the probability of a sample belonging to a class. Naive Bayes accepts that the emergence of a feature is independent of other features. Likewise, it is assumed that each feature independently contributes equally to the computation [45]. The probability value is given as 0 when there is new data in the test dataset that is not in the training set. Mathematically, the probability equation of Bayes’ theorem is:

—Posterior probability of the class when the predictor is given;

—Prior probability of the class;

—Probability of the predictor when class is given;

—Prior probability of the predictor.

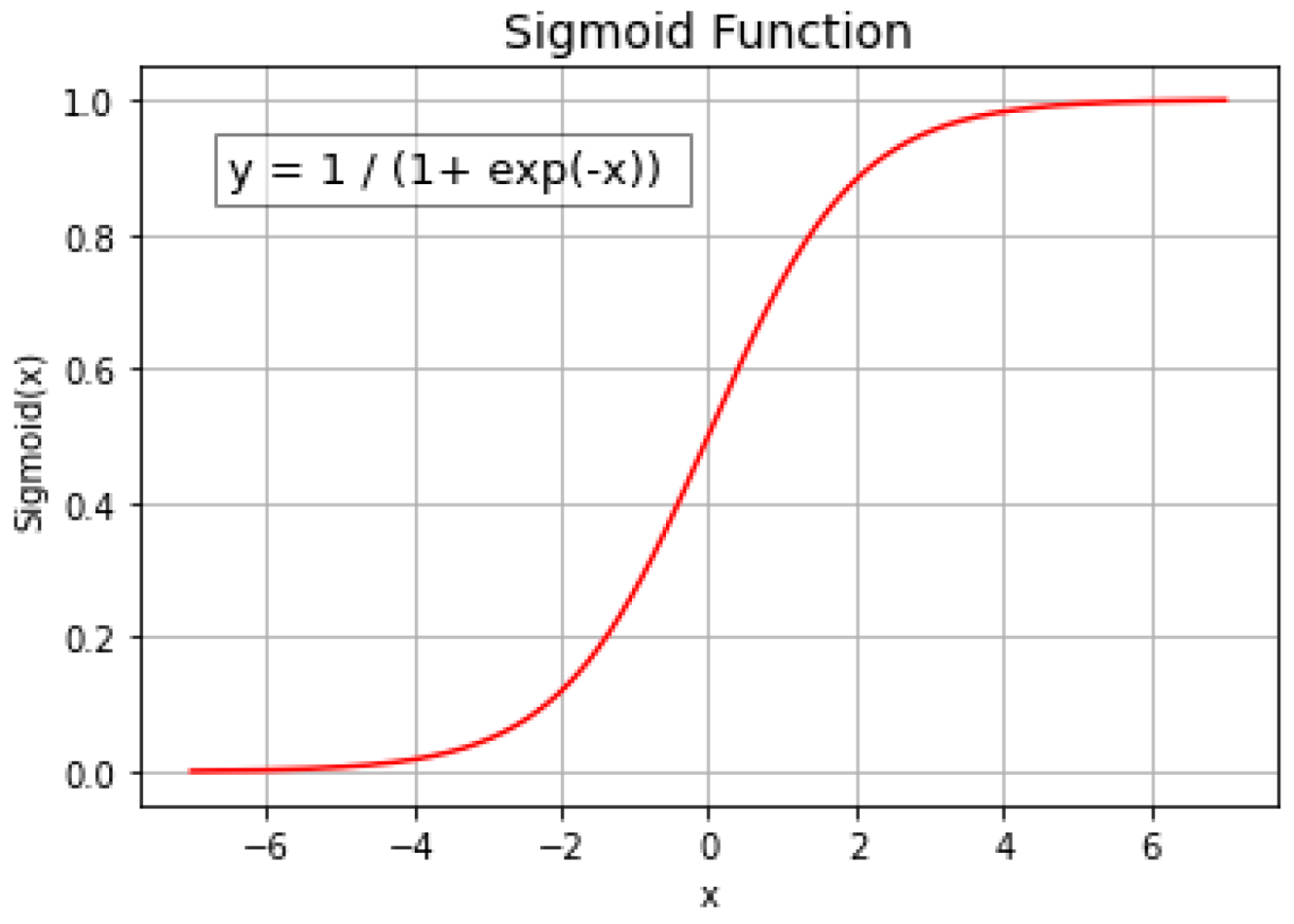

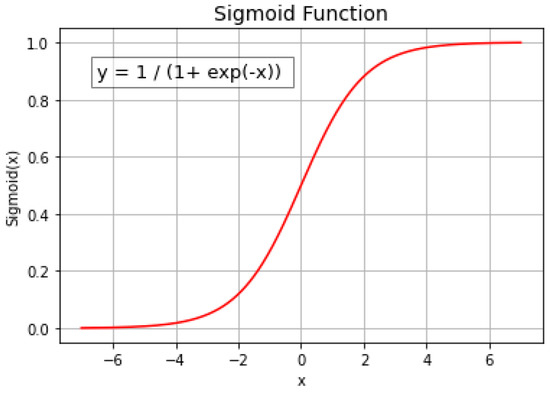

Logistic Regression (LR): It is a supervised machine learning algorithm used for regression and classification. It estimates the dependent target variable using the set of independent variables. It takes probability values between 0 and 1. It uses the sigmoid function shown in Figure 3 to position linear outputs between 0 and 1.

Figure 3.

Sigmoid Function.

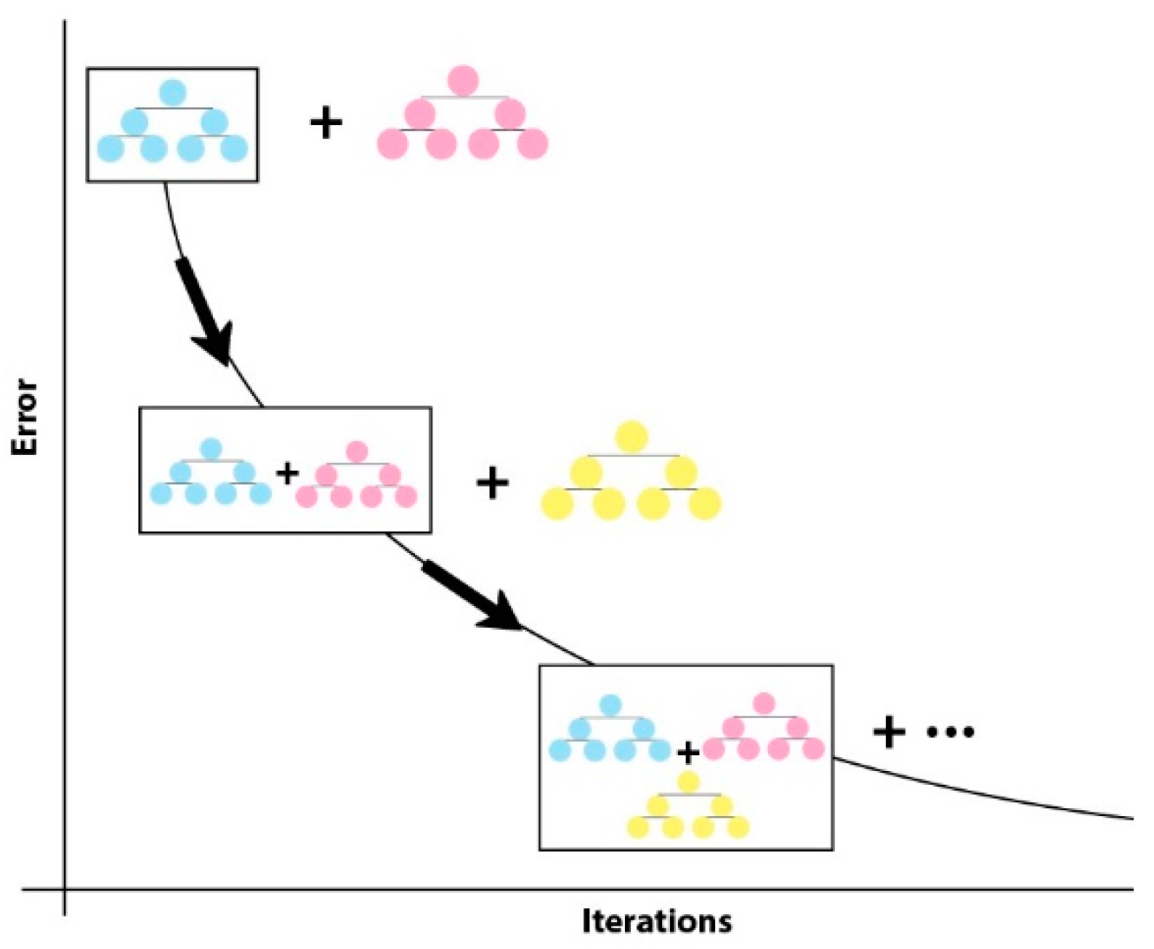

Gradient Boosted Tree (GBT): It is a supervised ensemble algorithm used for regression and classification. It is based on the boosting technique. It is an algorithm based on a weak learner tree. In the decision tree, a model is created for the weak learner and a prediction is made. Calculation errors are passed on to the next weak learning tree, as shown in Figure 4. The last model is the strong learner and is the weighted average of all models. Apache Spark MLlib is only supported for binary classification.

Figure 4.

Gradient Boosted Tree Iterations.

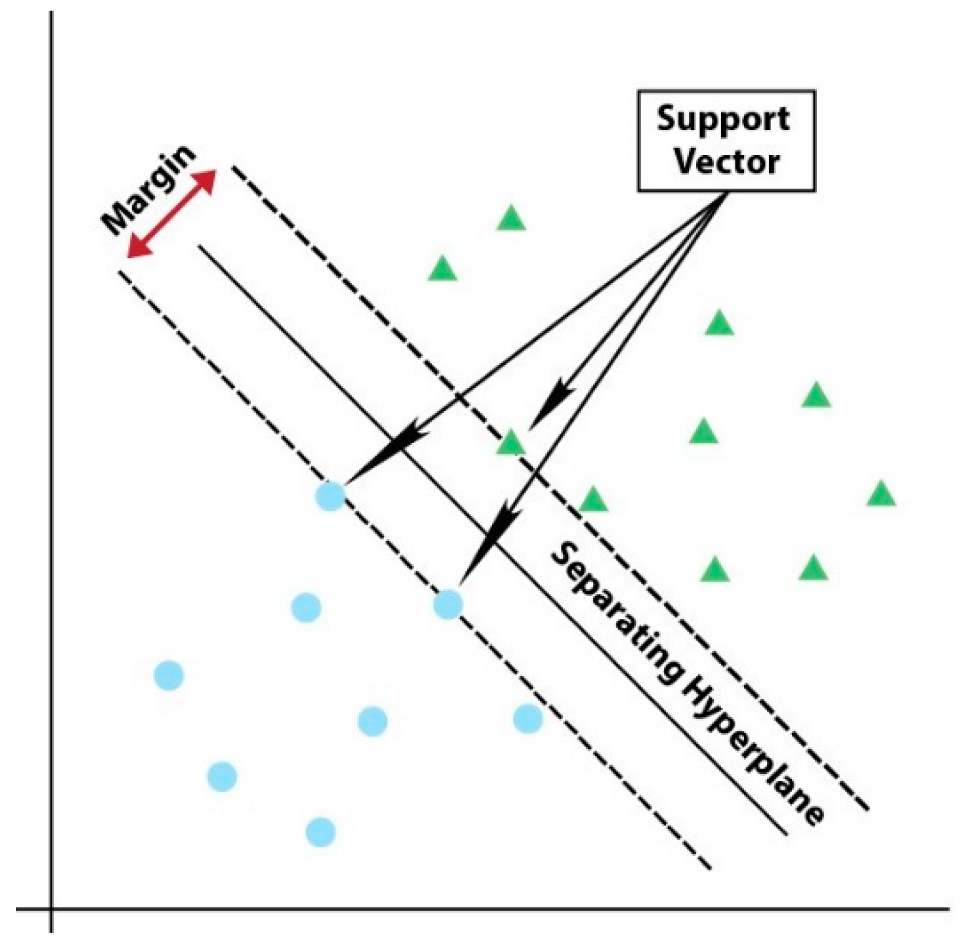

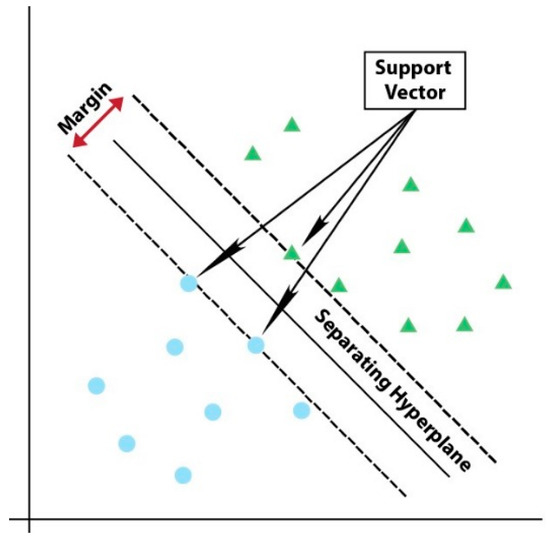

Linear Support Vector Machine (Linear SVC): It is a supervised machine learning algorithm. Each data point is plotted in a space of equal size to the number of features. As seen in Figure 5, classification is made by separating the data of one class from the others with a drawn hyper-plane. The training samples are called support vectors. Margins defined by support vectors define the hyperplane [46]. Apache Spark MLlib supports Linear SVC for binary classification only. The OneVsRest approach is used for multiclass classification.

Figure 5.

Support Vector Machine Algorithm.

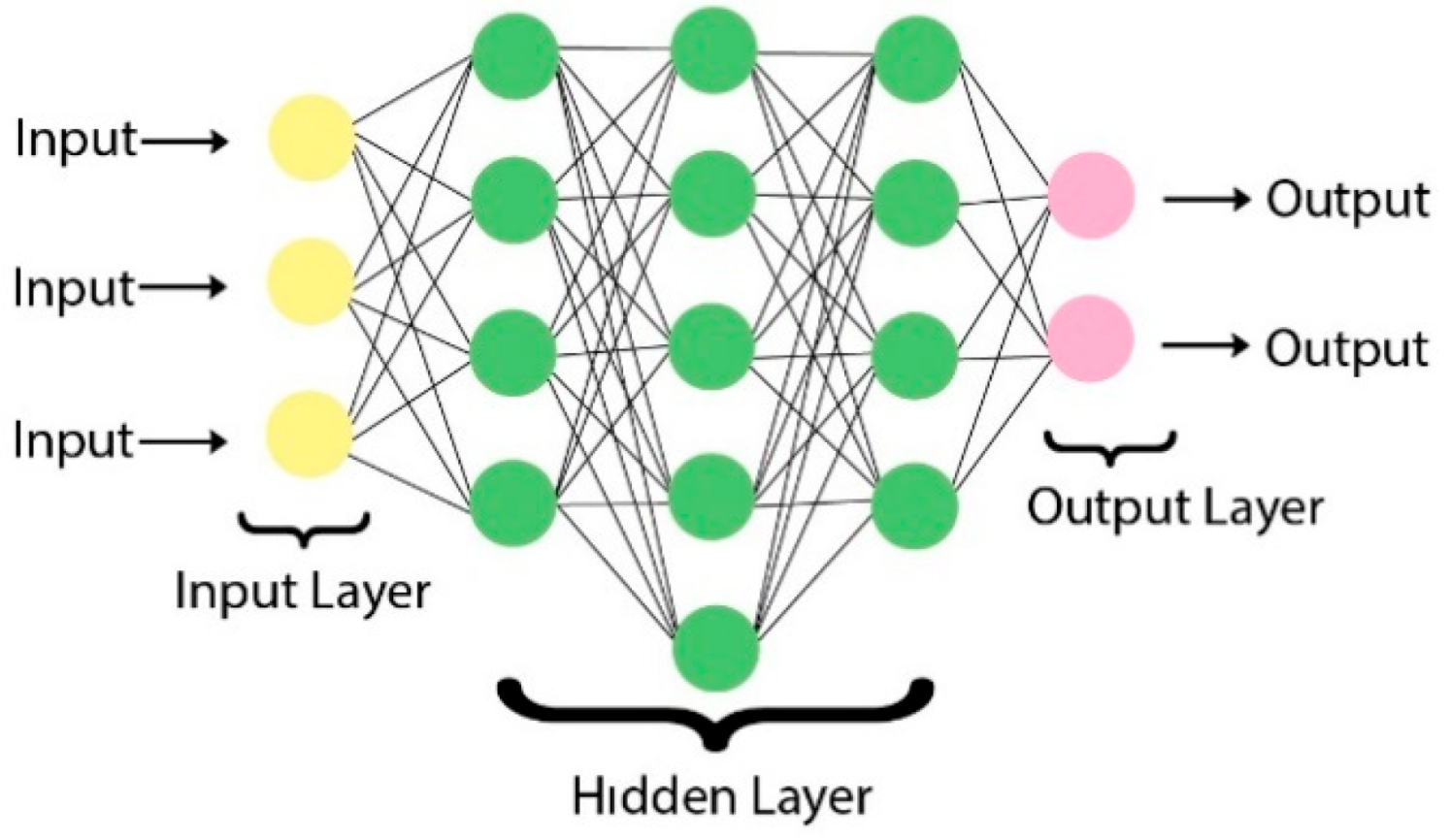

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP): It is a kind of feed-forward neural network. It has a structure consisting of an input layer, hidden layer, and output layer. The output layer must be equal to the number of classes. It has a supervised trained structure that uses labeled data. The multilayer perceptron is generally used when there are a large amount of labeled data [48]. Multilayer Perceptron is also a supported algorithm in Spark MLlib.

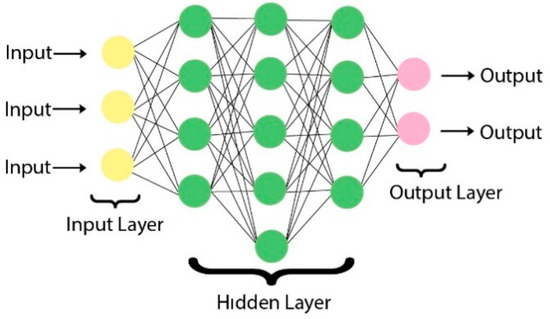

Deep Neural Network (DNN): As seen in Figure 6, it is a feed-forward neural network with multiple hidden layers. It is widely used in supervised and unsupervised learning and for classification and clustering. Deep Neural Networks compute the input sequentially across layers. The output vector in each layer creates the input vector for the next layer. The units in the tiers are multiplied by the current weight coefficient to produce a weighted total. The determined activation function determines the output value by applying the weighted sum obtained [48].

Figure 6.

Feed-Forward Neural Network Architecture.

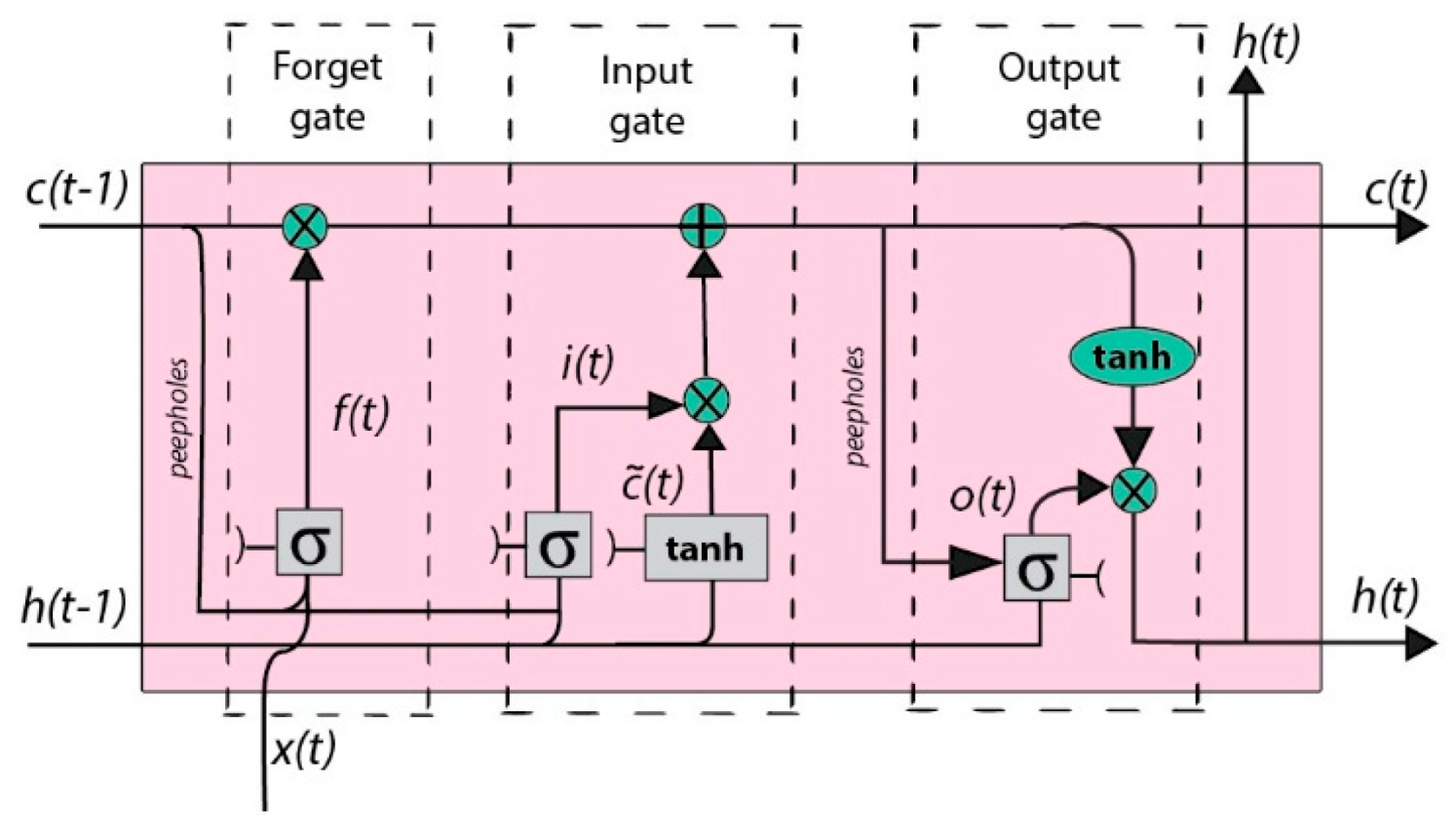

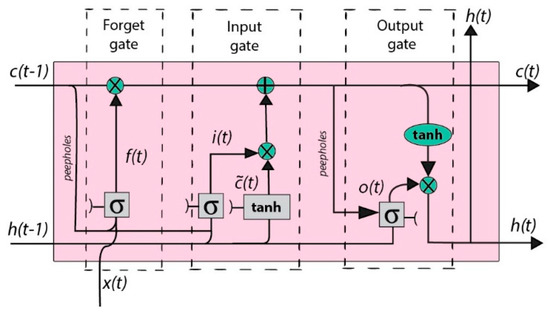

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): It is a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). It is designed to solve the disappearing gradient and long-term dependency problems in RNN. It has feedback connections. In this way, it keeps the sequential data in its memory and remembers the information for a long time. Unlike RNN, LSTM cells contain four interactive layers. Figure 7 shows the interactive layers in the LSTM cell. Each cell has three different gates. The gateway is the gate that updates the cell status at a given moment. The exit gate is the gate that determines the next cell’s input at a given moment. The forget gate is the gate that decides whether data will be forgotten or not, depending on the situation of the cell at a certain moment. The mathematical formulas for these gates are as follows.

Figure 7.

LSTM Architecture.

5. Experiments and Evaluation

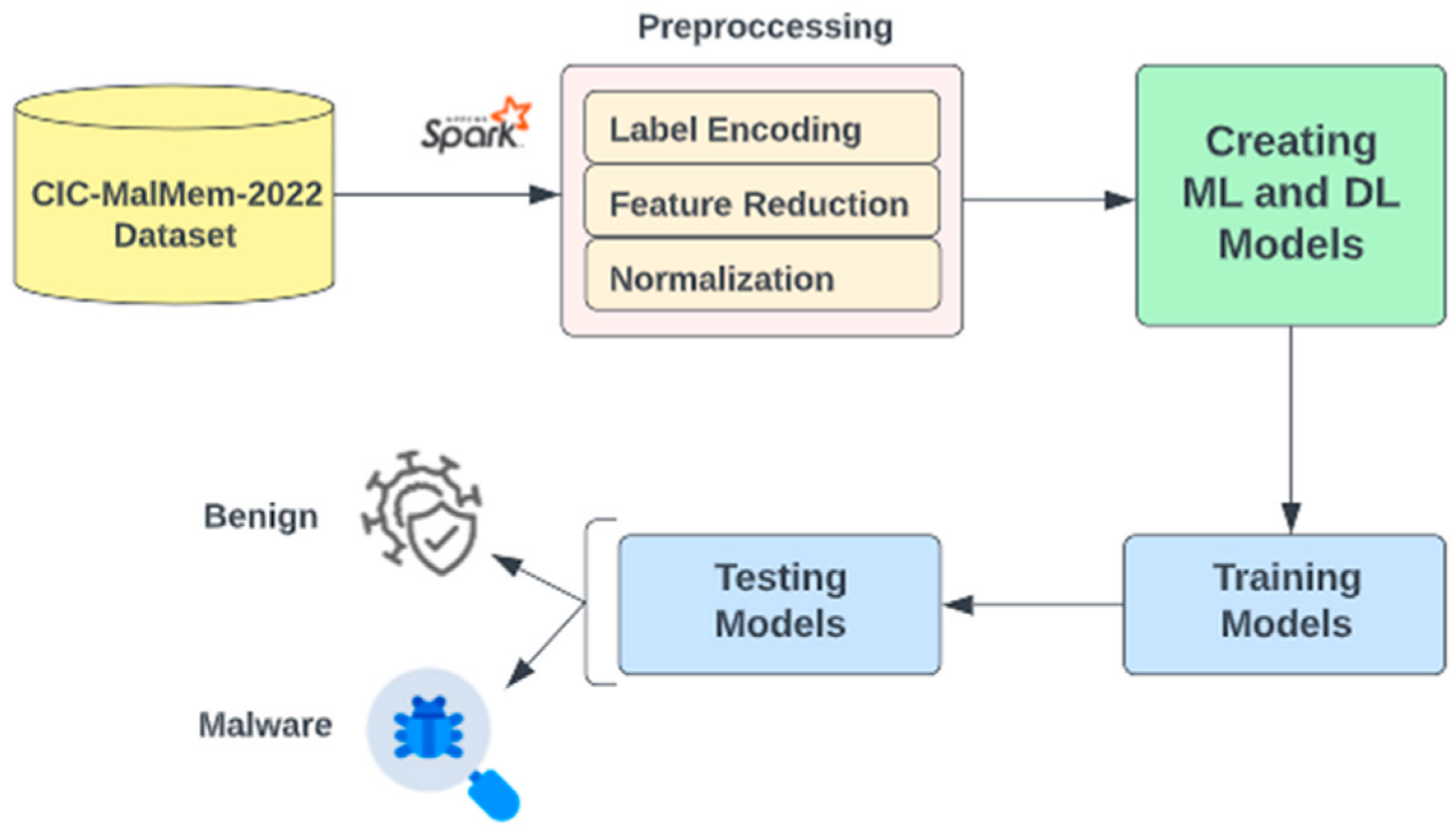

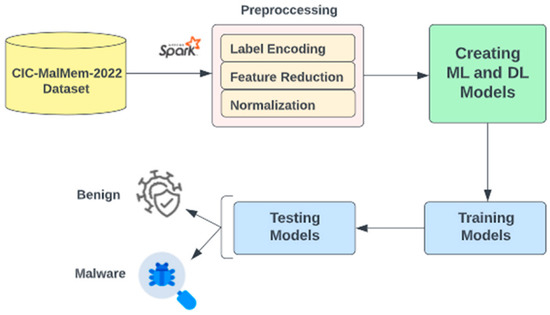

This section describes the experiments performed on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. The studies were carried out on Google Colab using Pyspark supported by the Apache Spark big data platform. Machine learning and deep learning models have been established using Keras and Spark MLlib. Nine machine learning and deep learning algorithms were compared, and their performances were evaluated. The workflow followed in the study is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Malware Detection Flowchart.

5.1. Model Parameters

In the study, the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset was divided into 70% training set and 30% test set. To ensure that the training and test sets to be used in the established models were the same, the seed parameter was set as “1234”. In addition, as a cross validation procedure in the study, the training and test datasets were separated 10 times by 70% and 30%, each time containing different data, and the results obtained were averaged. In the established models, the default parameters were generally adhered to. However, there were parameter values entered except for the default parameters.

In the model established with the Random Forest algorithm, the maximum depth was determined as 5. The maximum depth represents the depth of the tree. As the depth of the trees increases, it can capture more information about the data. In the model established with the Decision Tree algorithm, the maximum depth was specified as 5, as in the Random Forest. Two different parameter values were given in the model established with the Naive Bayes algorithm. These parameters were smoothing and Naive Bayes model type. The smoothing value is set to 1.0. The model type was Gaussian Naive Bayes. In the model created using the Gradient Boosted Tree algorithm, the maximum number of iterations was entered as 10. In the model created with the Linear Support Vector Machine algorithm, the maximum number of iterations was given as 10, as in the Gradient Boosted Tree. All parameters used in the Logistic Regression model were left by default. Four layers were used in the model created with the Multilayer Perceptron algorithm. The number of neurons used in the input layer was 52, equal to the number of features. There were 20 and 16 nerve cells in the hidden layers, respectively. Since binary classification was made in the study, the output layer consisted of 2 nerve cells. In addition, the maximum number of iterations for the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model was 50 and the block size was 128.

There were five layers in the model established with the Deep Neural Network (DNN) established with the Keras library. Fifty-two neurons were used in the input layer. There were 30 nerve cells in hidden layers. Since binary classification was made, there was 1 neuron in the output layer. ReLu activation function was used in the input and hidden layers. In the output layer, Sigmoid was used as the activation function. The loss function used in the model was binary cross-entropy and the optimization algorithm was Adam. At the same time, the dropout value was determined as 0.4. The model was run for 10 epochs. The reason for choosing 10 epochs in the study was to compare the performances of the models in shorter training periods. This is because there are rapidly changing malware attacks or IT infrastructures that are constantly changing. Therefore, models may need to be constantly trained against these new attacks and changes. It is evaluated that the selection of models with high performance in short epoch numbers will shorten the re-learning processes of the models and will provide an advantage in malware detection.

The model built with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) had three layers. Fifty-two neurons were used in the input layer and the hidden layer. Since binary classification was made, there was 1 neuron in the output layer. ReLu activation function was used in the input and hidden layers, and Sigmoid was used in the output layer. In the model, binary cross-entropy was preferred as the loss function and Adam was preferred as the optimization algorithm. At the same time, the dropout value was determined as 0.4. The performance values obtained from the LSTM network were also obtained by running 10 epochs for the reasons specified in the DNN.

5.2. Results and Comparison

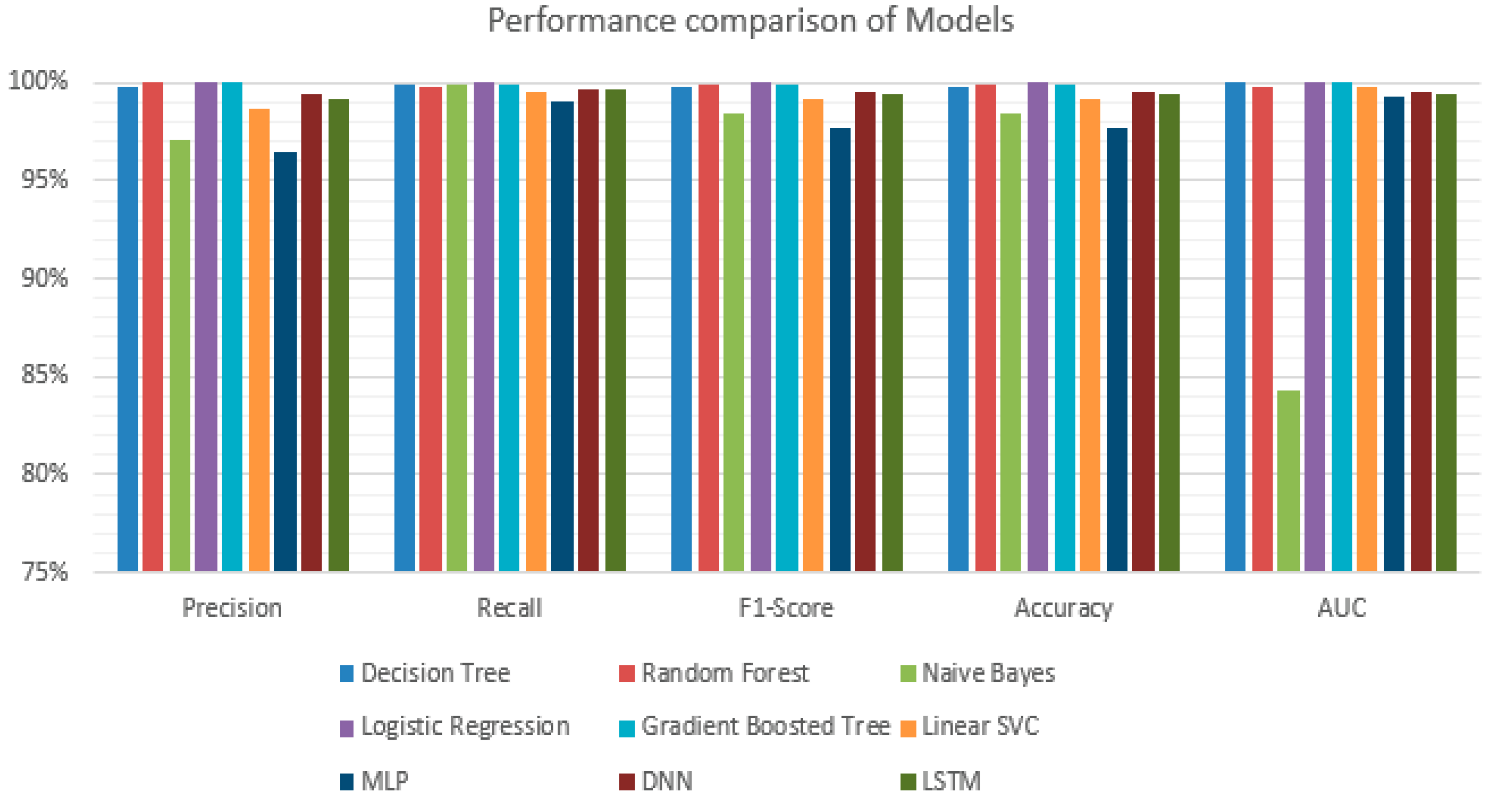

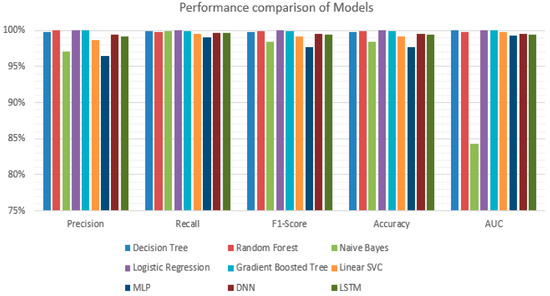

In the study, the performance of the models established with machine learning and deep learning algorithms in binary classification was evaluated. Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, Accuracy, and ROC-AUC parameters were calculated to compare the performances. The values of performance metrics for the nine machine learning and deep learning methods used are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Accuracy, and ROC-AUC results.

According to Table 5, the algorithm that gives the best accuracy rate is Logistic Regression with 99.97%. The Gradient Boosted Tree algorithm follows a Logistic Regression with 99.94%. Looking at the comparison chart in Figure 9, it is seen that all algorithms achieve high accuracy rates in the classification of the malware dataset. The algorithm with the lowest accuracy rate is the Multilayer Perceptron algorithm with 97.67%.

Figure 9.

Performance Comparison of ML and DL Models.

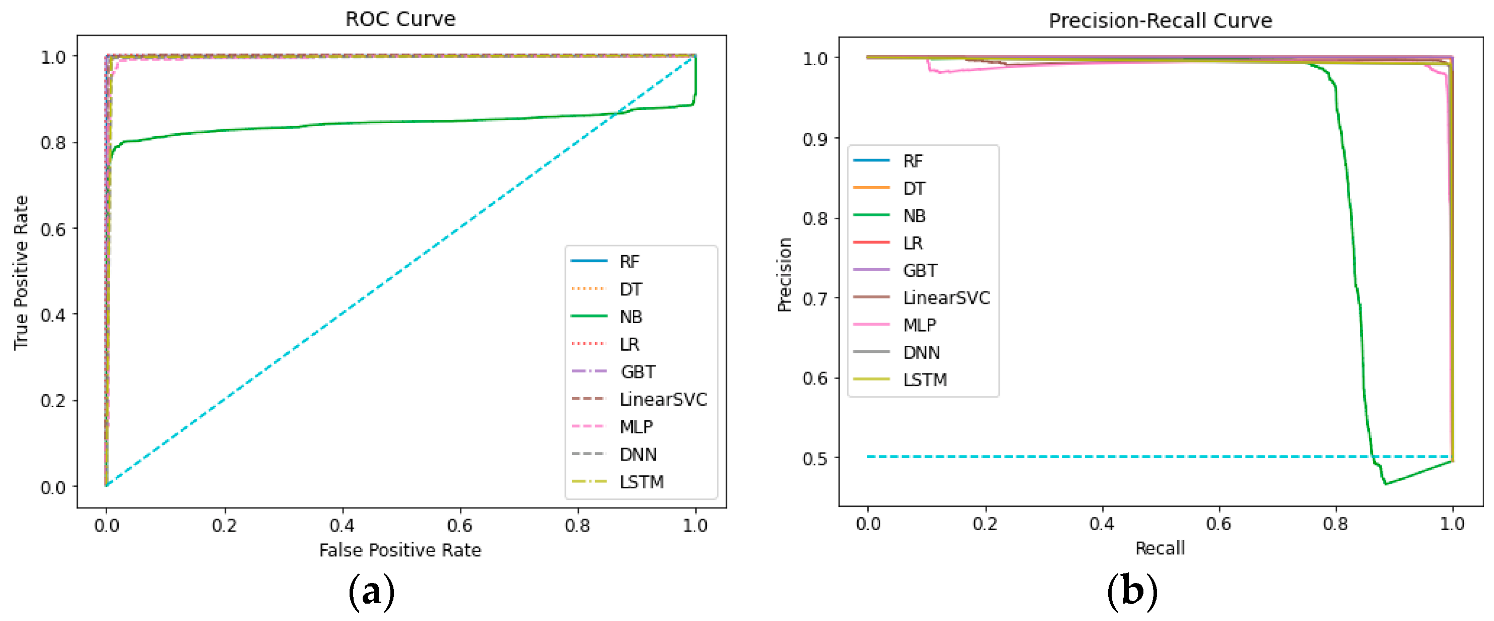

When we compare the AUC values of the models to evaluate their ability to distinguish classes, it is seen that the Naive Bayes algorithm has a rate of 84.25%, which is considerably lower than other machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Looking at the ROC curve given in Figure 10a, it is seen that the models other than Naive Bayes have quite high AUC values. The algorithm with the highest AUC value is Logistic Regression with 100%. The Gradient Boosted Tree algorithm has a 99.98% AUC value.

Figure 10.

(a) ROC-AUC: comparison of ML and DL Models; (b) PRC-AUC: comparison of ML and DL Models.

Figure 10b shows the PRC graph of the models. It is seen that as the Recall values of the Naive Bayes algorithm increase, the Precision value decreases rapidly after a point and falls below the 0.5 Precision threshold. When the Recall values of the LibSVM and MLP algorithms decrease, it is seen that there is some fluctuation in the Precision values. However, in general, it can be said that the algorithms have a perfect balance.

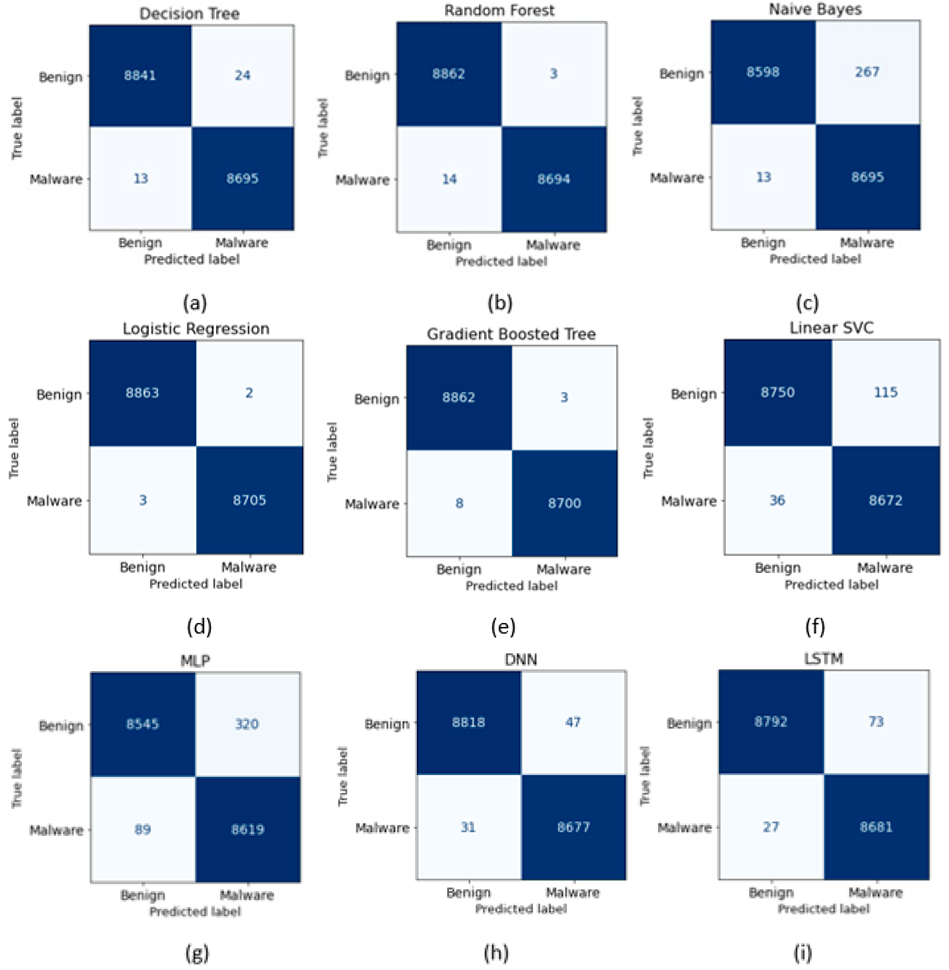

According to the Confusion matrices given in Figure 11, the Logistic Regression algorithm misclassified only 2 benign and 3 malwares. In other words, the Logistic Regression algorithm performed the most successful classification with the least number of misclassifications.

Figure 11.

Confusion Matrix of (a) Decision Tree; (b) Random Forest; (c) Naive Bayes; (d) Logistic Regression; (e) Gradient Boosted Tree; (f) Linear SVC; (g) MLP; (h) DNN; (i) LSTM.

Decision Tree and Gradient Boosted Tree algorithms both classified 3 benign as malware. However, Gradient Boosted Tree classified less malware as benign. In this way, it can be said that the Gradient Boosted Tree performs a more successful classification than the Decision Tree and Random Forest. In addition, Decision Tree and Naive Bayes algorithms also seem to misclassify the same number of malwares. However, Decision Tree has made few misclassifications in benign classification and is more successful than Naive Bayes.

MLP algorithm misclassified 320 benign and 89 malwares, making it the most misclassified algorithm. Naive Bayes and Linear SVC algorithms drew attention by misclassifying a high number of benign. When examined in more detail, the Naive Bayes algorithm’s FN rate is lower than FP. In other words, it can be said that the reason for the low success rate of the Naive Bayes algorithm is its failure in classifying the benign ones.

When deep learning algorithms are evaluated in themselves, it is seen that the DNN algorithm makes less misclassification than LSTM and MLP algorithms. It is also noteworthy that the algorithms that fail the most in malware classification are deep learning algorithms.

One of the deep learning approaches used in the study, LSTM networks are generally used in solving and classifying problems specific to serialized data. However, since LSTM networks are used in many intrusion detection or malware detection applications in the literature, they are used in this study to compare their performance in non-serial datasets. From the results obtained, the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset produced relatively successful results, although it did not have serialized data.

In general, when the FN and FP values are examined, it is seen that the Logistic regression, Gradient Boosted Tree, and Decision Tree algorithms have low FP values. These algorithms are more successful in benign classification. However, the remaining six algorithms have lower FN values and higher FP values. In other words, these algorithms are more successful in malware classification, but less successful in benign classification.

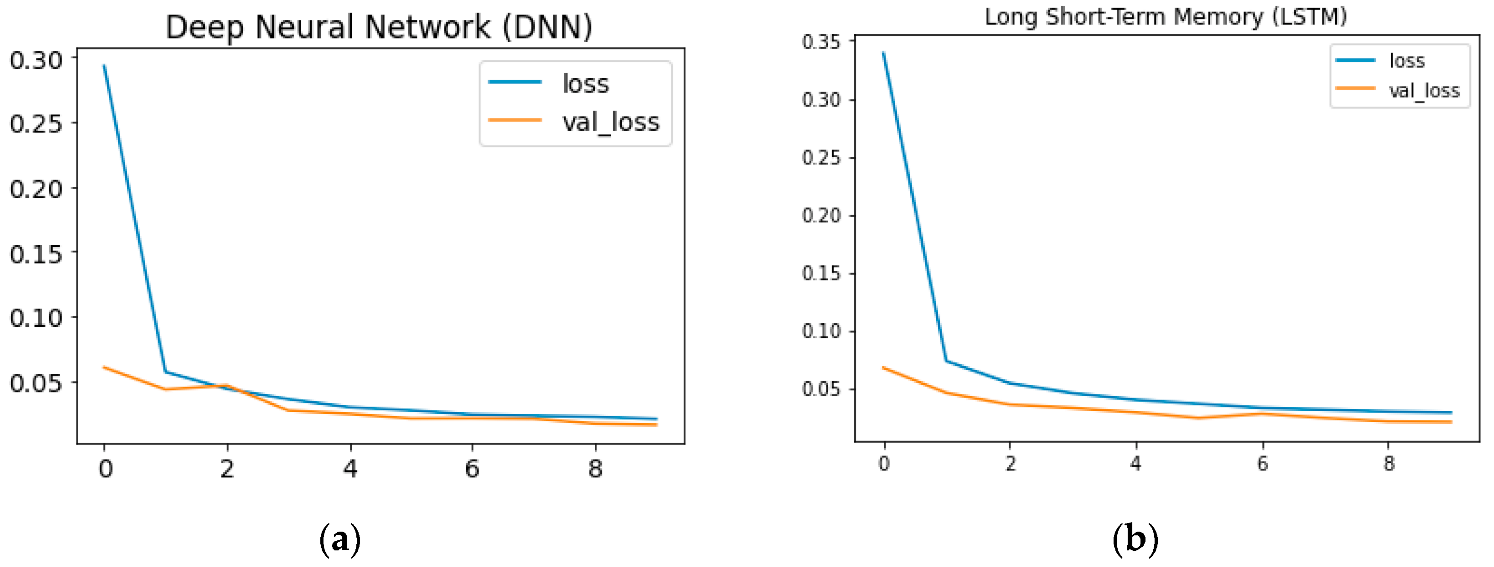

DNN and LSTM algorithms were run for 10 epochs. When the training loss-validation loss graphs of DNN and LSTM given in Figure 12 are examined, the inconsistency in the DNN model is remarkable. However, it tended to recover quickly after inconsistency. According to the given graphs, the generalizability ability of LSTM is higher than the DNN algorithm. However, in both graphs, the training loss rate is higher than the validation loss rate. Evaluations can be repeated with a larger epoch.

Figure 12.

Loss and Validation Loss Graphs for (a) DNN; and (b) LSTM.

6. Conclusions

Developing technology in the digitalizing global world brings with it an increase in malware. The rapid increase in malware makes it necessary to take some precautions. Static and dynamic analysis methods currently used to combat malware have some limitations in detecting modern and advanced malware. This situation has made the memory analysis-based approach gain importance in the detection of malware.

In this study, binary classification was performed with a big data approach to detect malware using the balanced CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset containing memory analysis data. The study was carried out using Apache Spark big data platform on Google Colab. Classification models were established using nine different machine learning and deep learning algorithms. The results of the models were compared with Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, Recall, and AUC performance metrics. When performance metrics are evaluated, it was seen that all models achieved high performances in malware classification. Among these algorithms, Logistic Regression was the best performing algorithm with 99.97% accuracy. The results show that memory analysis data contributed to high success rates in malware detection.

The parameters used throughout the study and the results obtained are specific to the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. If a different dataset is used, differences in the number of features or classes may result in different results. This situation is considered as a limitation of the study. However, it is thought that a successful malware detection can be achieved by using the machine learning and deep learning approaches used in this study with different model parameters specific to the dataset.

This study provides a basis for classification studies using machine learning and deep learning methods in memory analysis and malware detection. It also offers a new perspective in memory analysis-based malware detection using a big data approach. In future studies, the analyses can be repeated using different hyperparameters. In addition, the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset Category feature includes four different class labels: Benign, Spyware, Ransomware, and Trojan. In future studies, multiclass classification is planned using machine learning and deep learning algorithms based on the Category feature. In addition, since there is data imbalance between Benign, Spyware, Ransomware and Trojan classes, we plan to perform data balancing along with multiclass classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; methodology, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; software, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; validation, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; formal analysis, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; investigation, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; resources, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; data curation, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; writing—review and editing, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; visualization, M.D., G.O. and A.O.; supervision, M.D.; project administration, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AV-Test Institute. Available online: https://www.av-test.org/en/statistics/malware/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Yucel, C.; Koltuksuz, A. Imaging and evaluating the memory access for malware. Forens. Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2020, 32, 200903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banin, S.; Dyrkolbotn, G.O. Detection of Previously Unseen Malware Using Memory Access Patterns Recorded before the Entry Point. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; pp. 2242–2253. [Google Scholar]

- Sihwail, R.; Omar, K.; Zainol Ariffin, K.A. A Survey on Malware Analysis Techniques: Static, Dynamic, Hybrid and Memory Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2018, 8, 1662–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, R.N.; Li, R.; Yuan, B.; Pan, Y. Automated malware detection using artifacts in forensic memory images. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST), Waltham, MA, USA, 10–11 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayaka, C.; Jamdagni, A. An Efficient Approach for Advanced Malware Analysis Using Memory Forensic Technique. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ICESS, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1–4 August 2017; pp. 1145–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Sihwail, R.; Omar, K.; Ariffin, K.A.Z. An Effective Memory Analysis for Malware Detection and Classification. CMC Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 67, 2301–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihwail, R.; Omar, K.; Ariffin, K.A.Z.; Al Afghani, S. Malware Detection Approach Based on Artifacts in Memory Image and Dynamic Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucci, D.; Aniello, L.; Baldoni, R. Survey of machine learning techniques for malware analysis. Comput. Secur. 2019, 81, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaeikheirabady, M.; Farshchi, S.M.R.; Shirazi, H. A New Approach to Malware Detection by Comparative Analysis of Data Structures in a Memory Image. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Congress on Technology, Communication and Knowledge (ICTCK), Mashhad, Iran, 26–27 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mohaisen, A.; Alrawi, O.; Mohaisen, M. AMAL: High-fidelity, behavior-based automated malware analysis and classification. Comput. Secur. 2015, 52, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Ulyanov, D.; Semenov, S.; Trofimov, M.; Giacinto, G. Novel Feature Extraction, Selection and Fusion for Effective Malware Family Classification. In Proceedings of the Codaspy’16: Proceedings of the Sixth Acm Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–11 March 2016; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kumara, M.A.A.; Jaidhar, C.D. Leveraging virtual machine introspection with memory forensics to detect and characterize unknown malware using machine learning techniques at hypervisor. Digit. Investig. 2017, 23, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, R.; Li, R.; Yuan, B.; Pan, Y. A Behavior-Based Approach for Malware Detection. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2017, 511, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Petrik, R.; Arik, B.; Smith, J.M. Towards Architecture and OS-Independent Malware Detection via Memory Forensics. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (Ccs’18), Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–19 October 2018; pp. 2267–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Nissim, N.; Lahav, O.; Cohen, A.; Elovici, Y.; Rokach, L. Volatile memory analysis using the MinHash method for efficient and secured detection of malware in private cloud. Comput. Secur. 2019, 87, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, A.H.; Li, B.; Carrier, T.L.; Kaur, G. VolMemLyzer: Volatile Memory Analyzer for Malware Classification Using Feature Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2021 Reconciling Data Analytics, Automation, Privacy, and Security: A Big Data Challenge (RDAAPS), Hamilton, ON, Canada, 18–19 May 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Severi, G.; Leek, T.; Dolan-Gavitt, B. MALREC: Compact Full-Trace Malware Recording for Retrospective Deep Analysis. In Detection of Intrusions and Malware, and Vulnerability Assessment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10885, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Jang, S.; Li, S.; Jeong, Y.S.; Sung, Y. Long short-term memory-based Malware classification method for information security. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2019, 77, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, H.; Nassar, M.; Al Orabi, W.A. Benchmarking Convolutional and Recurrent Neural Networks for Malware Classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Tangier, Morocco, 24–28 June 2019; pp. 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.F.; Jiang, F.S.; Zhou, X.; Yi, S.W.; Sha, J.; Lio, P. ASSCA: API sequence and statistics features combined architecture for malware detection. Comput. Netw. 2019, 157, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Y.; Jang, S.; Jeong, Y.S.; Park, J.H. Malware classification algorithm using advanced Word2vec-based Bi-LSTM for ground control stations. Comput. Commun. 2020, 153, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panker, T.; Nissim, N. Leveraging malicious behavior traces from volatile memory using machine learning methods for trusted unknown malware detection in Linux cloud environments. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 226, 107095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.A.; Bandala, A. Portable Executable Malware Classifier Using Long Short Term Memory and Sophos-ReversingLabs 20 Million Dataset. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2021—2021 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2021; pp. 881–884. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.H.; Qian, Q. Malicious code classification based on opcode sequences and textCNN network. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2022, 67, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfeen, A.; Khan, M.A.; Zafar, O.; Ahsan, U. Process based volatile memory forensics for ransomware detection. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, E.; Ruppert, G.; Carvalho, T.; Ramos, F.; de Geus, P. Malicious Software Classification using Transfer Learning of ResNet-50 Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Cancun, Mexico, 18–21 December 2017; pp. 1011–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, S.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, R. Malware identification using visualization images and deep learning. Comput. Secur. 2018, 77, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.S.; Li, H.; Qian, Y.K.; Lu, X.D. A malware classification method based on memory dump grayscale image. Digit. Investig. 2018, 27, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Zhan, D.Y.; Liu, T.R.; Ye, L. Using Deep-Learning-Based Memory Analysis for Malware Detection in Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Sensor Systems Workshops (MASSW), Monterey, CA, USA, 4–7 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.S.; Li, H.; Qian, Y.K.; Yang, R.P.; Zheng, M. SMASH: A Malware Detection Method Based on Multi-Feature Ensemble Learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 112588–112597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.K.; Juwono, F.H.; Apriono, C. Vision-Based Malware Detection: A Transfer Learning Approach Using Optimal ECOC-SVM Configuration. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 159262–159270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkir, A.S.; Tahillioglu, E.; Aydos, M.; Kara, I. Catch them alive: A malware detection approach through memory forensics, manifold learning and computer vision. Comput. Secur. 2021, 103, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, J.; Roseline, S.A.; Geetha, S.; Kadry, S.; Damasevicius, R. An Efficient DenseNet-Based Deep Learning Model for Malware Detection. Entropy 2021, 23, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekerek, A.; Yapici, M.M. A novel malware classification and augmentation model based on convolutional neural network. Comput. Secur. 2022, 112, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, M.J.; Masood, O.A.; Mohammed, M.A.; Yasin, A.; Zain, A.M.; Damaševičius, R.; Abdulkareem, K.H. Image-Based Malware Classification Using VGG19 Network and Spatial Convolutional Attention. Electronics 2021, 10, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Menon, N.; Ravi, V.; Vishvanathan, S.; Pham, T.D. EfficientNet convolutional neural networks-based Android malware detection. Comput. Secur. 2022, 115, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaševičius, R.; Venčkauskas, A.; Toldinas, J.; Grigaliūnas, Š. Ensemble-Based Classification Using Neural Networks and Machine Learning Models for Windows PE Malware Detection. Electronics 2021, 10, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, N.A.; Odufuwa, O.E.; Misra, S.; Oluranti, J.; Damaševičius, R. Windows PE Malware Detection Using Ensemble Learning. Informatics. 2021, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Solomon, M.G. Fundamentals of Information Systems Security; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grammatikakis, K.P.; Koufos, I.; Kolokotronis, N.; Vassilakis, C.; Shiaeles, S. Understanding and Mitigating Banking Trojans: From Zeus to Emotet. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), Rhodes, Greece, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Apache Spark. Available online: https://spark.apache.org/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/malmem-2022.html (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Carrier, T.; Victor, P.; Tekeoglu, A.; Lashkari, A. Detecting Obfuscated Malware using Memory Feature Engineering. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Online Streaming, 9–11 February 2022; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, D.; Rani, R. Improving malware detection using big data and ensemble learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 86, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandotra, E.; Bansal, D.; Sofat, S. Tools & Techniques for Malware Analysis and Classification. Int. J. Next-Gener. Com. 2016, 7, 176–197. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Lee, B.; Yoon, S. Deep learning in bioinformatics. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 18, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).