Abstract

The safety level of the northern sea route (NSR) is a common concern for the related stakeholders. To address the risks triggered by disruptions initiating from the harsh environment and human factors, a comprehensive framework is proposed based on the perspective of resilience. Notably, the resilience of NSR is decomposed into three capacities, namely, the absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity. Moreover, the disruptions to the resilience are identified. Then, a Bayesian network (BN) model is established to quantify resilience, and the prior probabilities of parent nodes and conditional probability table for the network are obtained by fuzzy theory and expert elicitation. Finally, the developed Bayesian networkBN model is simulated to analyze the resilience level of the NSR by back propagation, sensitivity analysis, and information entropy analysis. The general interpretation of these analyses indicates that the emergency response, ice-breaking capacity, and rescue and anti-pollution facilities are the critical factors that contribute to the resilience of the NSR. Good knowledge of the absorptive capacity is the most effective way to reduce the uncertainty of NSR resilience. The present study provides a resilience perspective to understand the safety issues associated with the NSR, which can be seen as the main innovation of this work.

1. Introduction

Under the influence of global warming, a rapid decline in sea ice coverage and an increase in the depth of Arctic waters have been observed since 2000 Gascard et al., 2017 [1]. The potential commercial and political importance of arctic shipping routes has been the focus of various countries, shipping companies, and international organizations. Among the three shipping routes in Arctic waters, the arctic northeast route, also known as the northern sea route (NSR), is the most critical route because it greatly reduces the sailing distance between Asia, Europe, and North America compared with rational routes via the Suez [2]. According to [3], the reduced distance can be as much as 40%. As a result, shipping companies from Germany, China, Korea, Russia, Norway, and other countries have expressed interest in investing this route to obtain a competitive edge over competitors [4]. Although the opening and commercial operation of the NSR provide vast potential opportunities, Arctic waters still present major challenges for the shipping industry [5]. Harsh natural environments and fragile ecosystems make it difficult to maintain a satisfactory safety level for shipping operations along the NSR, which greatly increases the concerns of national and international parties. For example, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) issued the Polar Code in 2010 to ensure the safety level of shipping operations in Arctic waters [6]. In addition, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) has initiated a program to provide an accurate navigation chart for ships traveling along the NSR. Overall, the safety level of shipping operations within Arctic waters, particularly along the NSR, has garnered attention from various levels of companies at the national and international scales. However, the safety level of the NSR is still far from satisfactory, and accidents associated with shipping operations still occur at times. Therefore, a great deal of work has been done to better understand how to improve the security capacity and mitigate the various risks along the NSR. Therefore, in the present study, the concept of system resilience is introduced to attempt to obtain knowledge about the security capacity, and an investigation is conducted to improve the system resilience of the NSR.

1.1. Literature Review

The risk management of arctic shipping operations seeks to minimize the risk level. One of the most important issues is to identify the causal factors that contribute to risk or accidents. Therefore, many studies have been conducted to investigate the risk factors based on accidents and the unique natural environment in Arctic waters; such methods involve applying various theories, models, and techniques. Fault tree analysis was utilized by [7] to investigate the risk factors involved in chemical tanker accidents in Arctic waters. Later, an integrated methodology including fault tree analysis and the Human Factor Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) model was developed by [8] to study the collision risk during icebreaker assistance. Records of navigational shipping accidents that occurred in the Northern Baltic Sea during 2007 and 2013 were collected and investigated by [9], who found that ridged ice of a certain thickness cannot be considered the main cause of accident occurrence. Ref. [10] investigated the risk factors associated with Arctic maritime accidents from 1993 to 2011 by performing root cause analysis. Ref. [10] summarized various navigational risk contributors when sailing along an Arctic route, and the corresponding numerical weights were also given by using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and expert elicitation. The risk factors can also be identified by the application of Bayesian networks. Later, a novel Bayesian network (BN) model was proposed by [11] to identify the shipping operation risk in Arctic waters. Some studies based on the perspective of navigators have been performed to evaluate the shipping operation risk in Arctic waters, and such studies include those of [12,13], who studied the navigation risk in icy waters in the Baltic Sea. Ref. [6] investigated the key factors that influence the operation of arctic shipping routes.

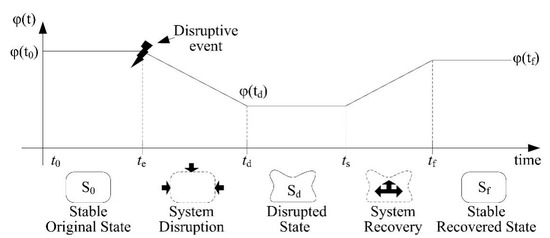

Resilience is widely regarded as a specified capacity factor pertaining to an organization or a system that reflects how well the organization or system can recover from a disrupted or destroyed state. The concept of resilience was first introduced by [14], who argued that resilience can enable an ecosystem to continue to operate after being disturbed. Later, many studies tried to define resilience [15,16,17]; however, there is currently no universal consensus on the definition of resilience. Based on its various definitions, resilience is widely used in different fields [18,19,20,21] due to its contribution to the development of the relationship between capacity and a disruption or disaster. Many important applications of system resilience are subject to infrastructure systems, such as urban infrastructure systems [22], electrical infrastructure systems [23], inland waterway ports [24], and full-service deep-water ports [25]. In addition, organizational resilience was defined by [17] as the ability of enterprises and other organizations to improve performance. Similarly, in the social domain, the resilience capacity is regarded as “the ability of communities to cope with external stresses and disturbances as a result of social, political, and environmental change” [26]. In past decades, substantial differences existed among various descriptions of system resilience; however, the quantification of system resilience has always been a common concern. Generally, system resilience can be regarded as a time-dependent variable, as shown in Figure 1. Initially, the system is stable in the original state; then, with the appearance of a disruptive event, the performance of the system deteriorates gradually, which can trigger system resilience to recover the system performance to the normal level. According to [27], system resilience can be decomposed into absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity, which can absorb the shocks caused by a disruption, adapt the system to the new disrupted conditions, and restore the system to normal conditions as much as possible, respectively.

Figure 1.

Resilience description associated with system performance and state transition [28].

Bayesian networks (BNs) are widely accepted as effective tools for conducting risk assessments and making decisions due to their notable advantage in easily updating information. Ref. [29] reviewed the applications of Bayesian inference for probabilistic risk assessment through 2007. Ref. [30] discussed different aspects of Bayesian network-based risk assessment. Actually, in engineering practice, BNs are usually integrated with other models, such as event trees [31], fault trees [32], bow-tie diagrams [33], HFACS [34], and so on. In addition to their successful application in risk assessment, BNs have been further utilized to evaluate the system performance and resilience capacity of specific systems. In the supplier selection BN model developed by [35], the resilience capacity was quantified in aspects of withstanding, adapting to, and recovering from a disruption. Moreover, [36] established a supply chain BN to forecast how risk factors affect the performance of the biomass supply chain network. Recently, in many studies, researchers have gradually explored the application of BNs in measuring system resilience. For instance, [37] established a comprehensive model for the resilience measurement of Systems of Systems (SoS) based on a BN.As a case study, the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) was taken as an example, and conditional resilience metrics were proposed to assess the importance of individual sub-systems. Later, [38] proposed a BN model to quantify the system resilience of infrastructure and took an inland waterway port as an example to demonstrate the application of the model. Then, a resilience measurement model based on a BN was further extended to explore aninterdependent electrical infrastructure system [23] and a full-service deep-water port [25].

1.2. Discussion of Existing Studies

Based on the literature review, extensive efforts have been made by international organizations and the relevant authorities to maintain the safety level of the NSR. Many studies on the NSR have been conducted, and safety issues for shipping operations that move through Arctic waters are still the main concerns globally due to the unavailability and uncertainty of information associated with navigation along the NSR. Improving the capacity to safeguard various ships transiting Arctic waters, especially the NSR, is a great challenge for the commercial operation of the NSR. The lack of safeguard capacity evaluations considering the safety of shipping operations along the NSR is a current gap in the literature. To address this gap, the present study proposes a comprehensive assessment model involving a fuzzy BN and information entropy to quantitatively measure the resilience of the NSR.

The present study mainly aims to pioneer the establishment of an integrated evaluation model based on fuzzy BN information entropy theory to measure the resilience of the NSR safeguard system and investigate the influence of contributing factors on system resilience. Under the framework of resilience, the disruptions to the NSR safeguard system were first identified by a literature review and expert elicitation. Then, resilience decomposition was performed to identify the contributing factors for system resilience, which were mapped into the BN structure together with the factors related to disruptions as the parent nodes in the BN. Experts with navigation experience or academic experience associated with the NSR were employed as consultants to quantify variables by using fuzzy theory. Finally, we ran the developed BN with GeNIe 2.3 software and generated conclusions. The main features of the present study are summarized as follows:

- A system resilience analysis framework is explored to improve the safeguard capacity of the NSR in mitigatingvarious disruptions that affect safe transit along the NSR;

- A methodology is established to conduct a resilience assessment of the NSR based on the integration of fuzzy theory, a BN, and information entropy theory;

- The proposed fuzzy BN-based model can effectively cope with the uncertainty and unavailability of information associated with Arctic waters;

- The conduction of different types of analyses, such as forward and backward propagation, sensitivity, and information entropy analyses, helps us obtain a complete understanding of NSR resilience.

1.3. Organization

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 illustrates an overview of the proposed resilience measurement methodology, the employed techniques, and the relevant theory. In Section 3, a model aimed at measuring the system resilience of the NSR is established based on the fuzzy Bayesian network. The results and discussion of the present study are given in Section 4, and finally, the conclusion is presented in Section 5.

2. Proposed Resilience Measurement Methodology

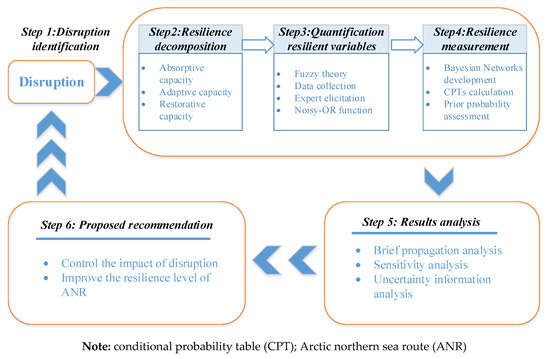

The resilience level of a specified system is widely regarded as the measurement of the interaction between system resilience and disruptions exerted on the system. Thereinafter, disruption identification and resilience capacity decomposition are essential for resilience measurement, based on which some quantification technology can be applied to calculate the resilience level and investigate the resilience characteristic. In the present study, a methodology that includes five steps based on a fuzzy Bayesian network is proposed to evaluate system resilience, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proposed resilience measurement model for the northern sea route (NSR).

Step 1—Identify the disruptions exerted on the system. The first step is to identify the potential disruptions that impacts the performance of the NSR resilience. A potential disruption may be caused by a severe nautical environment, the failure of equipment or facilities, and navigational service outages; these issues will be analyzed in detail based on expert elicitation and a literature review.

Step 2—System resilience decomposition. This step will focus on the design of the resilience capacity structure that fully relates to the different stages of disruption identified in Step 1. In this step, the system resilience capacities are primarily decomposed into three capacities: absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity.

Step 3—Quantification of resilient variables. It is critical for the resilience measurement to quantify the identified disruption and relevant capacities. Therefore, in this step, a methodology associated with the combination of fuzzy theory and expert elicitation is applied based on the present data concerning the NSR resilience. Additionally, the noisy-OR function is used, and it can be regarded as the input for the subsequent Bayesian network.

Step 4—System resilience measurement. The resilience level of the Arctic NSR is calculated through the establishment of a Bayesian network in which the prior probabilities of the nodes without parent nodes and the conditional probability table (CPT) for the child nodes with multiple parent nodes are obtained according to Step 3.

Step 5—Result analysis. Different techniques are employed in this step to gain insights based on the developed Bayesian network in Step 4. The techniques include forward propagation, backward propagation, sensitivity analysis, and information uncertainty analysis.

Step 6—Proposed recommendation. Some potential recommendations are proposed according to the abovementioned steps to improve the resilience level of the Arctic NSR to defend against disruptions from the environment.

2.1. Fuzzy Theory

2.1.1. Fuzzy Number Selection to Design a Questionnaire

Since first proposed by [39], fuzzy set theory has been widely introduced in the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) because experts prefer to express fuzzy judgements rather than crisp comparisons. According to fuzzy set theory, we can define a fuzzy number, , in the set of real numbers, , where represents the fuzzy sets; then, . The concept of a fuzzy number can be expressed as [40]:

where is the membership function and is a random real number. Generally, triangular and trapezoidal fuzzy numbers have been widely applied for the fuzzy judgements of experts in varied case studies. According to the definition of a fuzzy number, the membership function of the triangular fuzzy number can be expressed as:

where the triangular fuzzy number is defined as for ; and are the lower and upper values of fuzzy number, , respectively; and is the modal value. For the limit case of , is a nonfuzzy number. Similarly, for a trapezoidal fuzzy number, , the membership function is expressed as:

To illustrate the operational rules of fuzzy numbers, two different triangular fuzzy numbers are taken as examples, and , and the algebraic operation rules are:

Generally, the linguistic expressions of experts are meaningful for handling complex circumstances and eliciting meaningful advice. However, it is difficult to directly quantify the qualitative expressions of experts; therefore, the application of fuzzy numbers can solve this problem. Several attempts have been made to transfer qualitative linguistic expressions into corresponding fuzzy numbers [41,42,43], and the technique proposed by [43] is widely accepted; this approach includes eight scales associated with verbal expressions. Later, [44] suggested that the estimation of human memory aptitude should include seven terms, plus or minus two patches, indicating that the number of verbal terms should be between five and nine for good expert elicitation.

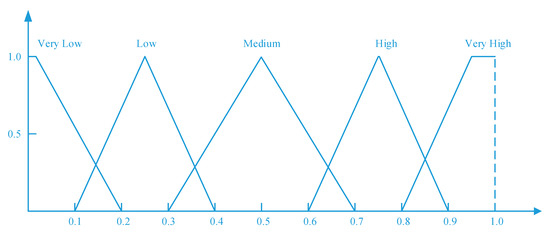

In the present study, transformation scale six, which includes five verbal expressions [45], was selected to design the expert questionnaire, and fuzzy trapezoidal numbers were selected to express expert judgements. The reason for selecting scale six was mainly that the experts preferred to give their judgements through five verbal expressions. In addition, the reliability of scale six has been verified by its successful application in various fields, such as the oil and gas [46], medicine [47] and marine [48] fields. Table 1 illustrates the corresponding relationship between linguistic expressions and fuzzy numbers based on scale six. According to Equation (3), the expression of the membership function of the trapezoidal fuzzy is illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Linguistic expressions and their corresponding fuzzy numbers for scale six.

Figure 3.

Scale six transformation [45].

2.1.2. Weight Determination for the Expert Capacity

With different professional positions, experience levels, education levels, and so on, the experts employed gave various judgements regarding the issues in the present study; therefore, it is necessary to weigh individual expert capacities to value the judgements made by high-level experts more than those from low-level experts. Before evaluating the expert capacity, indicators representing the expert capacities should be designed. Then, a score rating for each indicator should be developed to quantify various capacities. Next, pairwise comparison matrices can be established based on expert information. These matrices can be further processed as follows until the weight of an individual expert is calculated [49].

- ⮚

- With respect to fuzzy numbers in pairwise comparison matrices, the geometric mean technique is applied to obtain the synthetic pairwise comparison matrix, , as follows:where is the pairwise comparison matrix of the Kthindicator for the expert capability evaluation.

- ⮚

- The fuzzy weights of the criteria for each expert can be calculated by the following equation:where the fuzzy weight of the ithexpert is indicated by .

- ⮚

- The fuzzy weights for each criterion are defined as follows:where denotes the fuzzy weight of the ithcriterion, for which indicate the lower, middle, and upper values of the fuzzy weights of the ithcriterion, respectively.

- ⮚

- The weight of each expert is computed by employing the center of area technique, as follows:

2.1.3. Expert Viewpoint Aggregation

To eliminate any cognitive biases, it is necessary to aggregate expert opinions. Suppose that each expert, , states his or her personal viewpoints about a certain issue by utilizing a predefined set of linguistic expressions. These linguistic variables can then be transferred into corresponding triangular or trapezoidal fuzzy numbers, which can be processed further until defuzzification is achieved.

(1) Calculation of the degree of similarity. is defined as the degree of agreement for different opinions among experts. Suppose and represent two standard triangular fuzzy numbers (); then, the degree of agreement between and can be obtained by:

where is the number of fuzzy set members; e.g., is for standard triangular fuzzy numbers and is for standard trapezoidal fuzzy numbers. Additionally, the greater the values of are, the greater the similarity between experts and .

(2) Calculation of the average agreement (AA) degree for each expert viewpoint.

where is the total number of experts.

(3) Calculation of the relative agreement (RA) degree between two kinds of experts. The value of for the uthexpert can be obtained by:

(4) Estimation of the consensus coefficient (CC) for each expert. The value of for the uthexpert can be obtained by:

where the coefficient is introduced to represent the importance of over , namely, the greater is, the more important is. Actually, when , no weight is distributed to , indicating that a homogenous group of experts is employed; for another limit case, , the consensus degree among the various expert viewpoints is adequately high.

(5) Calculation of the aggregated results of the expert viewpoints. The aggregated results denoted by can be computed by:

(6) Defuzzification of the aggregated results. The defuzzification of fuzzy numbers is critically important for the application of fuzzy set theory. The center of area (CoA) method is widely used for the defuzzification operation, and it is expressed as:

where represents the defuzzification result and indicates the aggregated membership functions defined in (1) and (2) for fuzzy triangular and trapezoidal numbers, respectively. Therefore, the fuzzy numbers of the aggregated results, denoted as for fuzzy triangular numbers and for fuzzy trapezoidal numbers, can be defined by (18) and (19), respectively.

2.2. Bayesian Network Theory

A Bayesian network is a multielement graphical model involving a set of variables and their conditional dependencies via a directed acyclic graph [50]. With the advantages of a flexible structure and probabilistic reasoning function, BNs are widely applied in the field of safety evaluation [32,51]. Series of nodes and edges are necessary for a basic BN to represent system variables and association rules, respectively. Each node in a BN is assigned a probability distribution, and each edge is affiliated with a direction, which is directed from parent node to child node. The nodes with multiple parent nodes should be assigned conditional probabilities that are included in the conditional probability tables (CPTs). The CPTs are based on the type and strength of the causal relationships between parent and child nodes.

Considering the conditional dependencies of the variables, a BN represents the joint probability distribution of a set of variables, , as in [52]:

where is the parent set of variable . The probability of variable can be obtained by:

Based on Bayes’ theorem, a BN can update the prior probability of events under newly given observations, called evidence, to yield the posterior probability. The posterior probability can be calculated by:

where is the desired posterior probability and represents the evidence.

2.2.1. Prior Probability Calculation for Nodes without Parents

The prior probability for nodes without parents in the Bayesian network can be quantified by the integration of fuzzy theory and the aforementioned expert elicitation. The calculation can be conducted following the steps described below.

Step 1—The questionnaire is designed to obtain expert viewpoints according to the approach described in Section 2.1.1.

Step 2—The capacities of experts employed in the present study are weighted and scored to compensate for any cognitive biases and aggregate expert opinion based on the calculation process mentioned in Section 2.1.2.

Step 3—The fuzzy aggregation of expert opinions obtained from Step 1 is implemented by applying the calculation methods expressed in Section 2.1.3.

2.2.2. Conditional Probability Table Calculation with the Noisy-OR Function

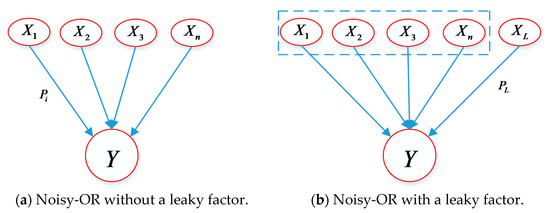

The calculation of the CPT is crucial for reliable model inference. However, the CPT is generally regarded as complicated, especially for the case of a large BN with many nodes. Therefore, many studies have focused on CPT calculations, of which expert elicitation associated with fuzzy theory has been widely employed [34,53,54]. Based on expert elicitation, the Noisy-OR model [55] is utilized to calculate the CPT with the following assumptions (suppose a child node has parents, , as shown in Figure 4a):

Figure 4.

Typical Noisy-OR model.

- (1)

- All the nodes in the proposed Bayesian network can be regarded as Boolean variables; that is, the nodes have binary states, true or false, representing positive or negative outcomes, respectively;

- (2)

- The causes (parent nodes) of are mutually independent;

- (3)

- The probability that is true when only one causal factor, , is true while all other factors except are false can be expressed as:where represents the connection probability between the parent node, , and the corresponding child node, . The connection probability can be derived by:

Suppose every causal factor, , in Figure 4a is a member of the set and all the causal factors with a “true” state label belong to . Additionally, the causal factors with a “false” label are members of . Then, the CPT of can be obtained by

For the limit case in which is a null set, that is, the states of all the causal factors are “false”, then . However, it is almost impossible for the probability, , to equal zero. In practice, the subsequent event, , may occur even if all the causal factors are “false” because some unknown causal factors may still exist beyond the identified causal factors. Therefore, the leaky Noisy-OR model (illustrated in Figure 4b) is introduced to handle the unknown causal factors; in this case, the conditional probability of Y can be calculated by:

where represents the connection probability between and the leaky causal factors .

2.3. Information Entropy Theory

Currently, the Arctic NSR is not a well-developed commercial waterway; as a result, some information associated with the NSR may be absent, which makes it difficult to quantify the uncertainty of the unknown information. To improve the reliability of the underlying information, information entropy theory is applied in the present study. In the framework of information entropy, the uncertainty of a variable can be measured by a probability distribution. Suppose is a discrete random variable with the probability distribution , where represents the probability of . Then, the information pertaining to a specific value, , for this random variable can be defined as:

where the base in the logarithm is usually taken as 2 ore; in the present study, the base is 2.

The information function theoretically controls the volume of information conveyed by the specific state, such as . The information entropy function can be defined as the expectation of the information, which is expressed as:

The information entropy function can be further processed mathematically as:

For the discrete random variable, , the Function (29) can be expressed as:

where and . The higher the value of the information entropy is, the more uncertainty the variable contains. The entropy can reach the maximum when the probability distribution is uniform, i.e., is equal for all .

Suppose is a target variable and is a contributing factor, similar to the relationship between the child node and parent node in the Bayesian network. If the target variable is conditionally dependent on the dependent variable , then we have:

where denotes the number of states, for a Boolean variable, and represents the conditional entropy of target given the contributing factor . Then, the mutual information between the target variable and the contributing factor can be defined as:

3. Model Established for NSR Resilience Measurement

3.1. Scenario Development

The Arctic NSR is characterized by a special nautical environment and unique location compared to other national and international waterways. Traditionally, the NSR depicted in Figure 5 is made up of five legs: the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea, the East Silerian Sea, and the Chukchi Sea. The presence of sea ice, including drifting icebergs, has made this route almost inaccessible for marine transportation [56]. The area of ice-covered waters within the NSR is shown in Table 2. It is widely accepted that the navigating period for the NSR can be continuous from September to March of the following year.

Figure 5.

The Arctic Northeast Route [11].

Table 2.

Average ice-covered waters in the marginal seas of the NSR region [57].

With the difficulties associated with communication and data acquisition in the NSR region, the safety issues and environmental risks related to NSR transport are traditionally managed based on empirically determined rules and regulations, which can be useful for shipping activities characterized by low traffic density with small ships [58]. However, the ships sailing along the NSR are becoming increasingly large in size, and there is a lack of relevant empirical data on which mitigation of the hazards with respect to the NSR can be based [59]. Therefore, safety issues concerning the NSR are an urgent problem that must be solved.

3.2. Disruption Identification

A disruption of the system resilience, also known as a potential threat, can be beneficial for the improvement of the resilience level of the system. Only if a disruption is identified effectively can the resilience be quantitatively measured; however, the disruptions are different from risks and causal factors contributing to accidents. Actually, only part of a disruption is able to ultimately cause accidents, with evolution to risk and causal factors. Therefore, it is difficult to identify all disruptions practically. In the present study, the disruptions identified from safety meetings, accident reports, interviews, and literature reviews are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptions of the disruptions to the NSR resilience.

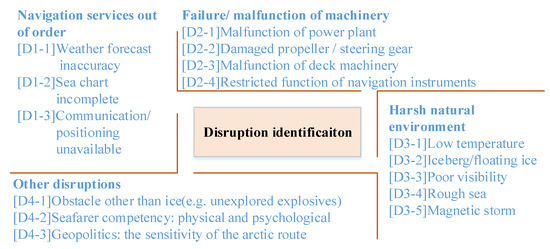

As shown in Table 3, 15 kinds of disruptions were identified in the present study. Subsequently, a safety meeting was conducted. After consulting experts, such as experienced mariners, senior scholars, and safety managers associated with the Arctic NSR, all disruptions were finally divided into four groups: navigation services out of order (N = 3), malfunction/failure of machinery (N = 4), harsh nautical environment (N = 5), and other disruptions (N = 3). The classification results are presented in Figure 6. Furthermore, classifying all the disruption factors into different groups can facilitate the calculations for the CPT of the Bayesian network in Section 3.4.

Figure 6.

Disruptions to safe navigation along the NSR.

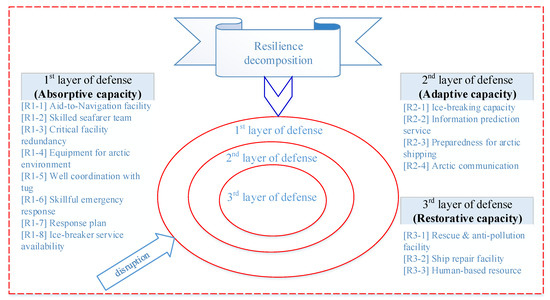

3.3. Resilience Capacity Decomposition for the Arctic Northeast Route

The resilience capacity can be defined as the capacity of a certain system to absorb, adapt to, and recover from any shock due to a disruption [23]. It is widely accepted that resilience capacities are classified as the absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity for a specified system [25,27]. In the present study, the underlying factors pertaining to these three kinds of capacities for the Arctic NSR resilience are identified, as illustrated in Figure 7. All the factors presented in Figure 7 will be included in the developed BN.

Figure 7.

Resilience decomposition designed for the NSR.

3.3.1. Absorptive Capacity

The absorptive capacity can be defined as the extent to which the Arctic Northeast Route security system is able to automatically defend against shocks due to disruptions. As shown in Figure 6, the absorptive capacity is considered the first line of defense to resist the adverse impact of the disruption. Inspired by the “inherent resilience” theory proposed by [69], the absorptive capacity can be further divided into the defense capacity under ordinary circumstances and the emergency response capacity under crisis conditions. Finally, a list of seven contributing factors for the absorptive capacity of the Arctic Northeast Route security system was obtained, and it is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Absorptive capacity of NSR resilience.

3.3.2. Adaptive Capacity

The adaptive capacity can be defined as the level to which a system self-organizes itself and takes dynamic measures to restrict and control the severe impact of a disruption. Compared with the absorptive capacity, the adaptive capacity requires flexible and dynamic efforts [71] and mitigates a disruption as a “second line of defense”, as presented in Figure 6. It is also regarded as part of the “post-accident strategy”. The features contributing to the adaptive capacity of the NSR resilience are described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Adaptive capacity of NSR resilience.

3.3.3. Restorative Capacity

The restorative capacity can be defined as the extent to which a specified system is able to recover from or repair a destroyed or failed function due to the impact of a disruption. Based on Figure 6, the restorative capacity acts as the last line of defense for the system to resist a disruption; that is, in the case that the absorptive and adaptive capacities fail to tolerate the impact caused by a disruption, the restorative capacity remains. Generally, it takes a relatively long time for the restorative capacity to recover the normal function of the system, and various human resources, services, tools, and so on are essential. Three aspects of the restorative capacity pertaining to the Northeast Route security system are described in Table 6.

Table 6.

Restorative capacity of NSR resilience.

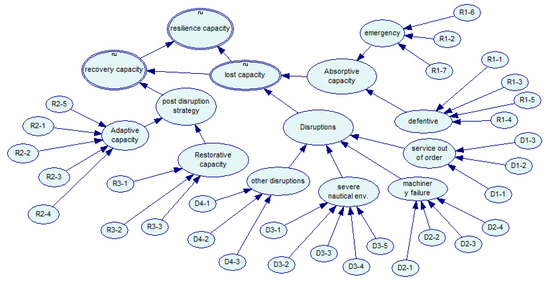

3.4. Resilience Measurement Using the Fuzzy Bayesian Network

In this section, a Bayesian network is established to quantify the resilience of the Arctic Northeast Route security system. Based on the identified disruptions and the resilience capacity decomposition in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, the visual structure of the proposed Bayesian Network described in Figure 8 is developed using GeNIe 2.3 software.

Figure 8.

Bayesian network (BN) established for measuring the resilience of the NSR.

3.4.1. Reliability Quantification for the Employed Experts

Expert elicitation is useful and valuable in most situations when available resources are lacking or limited by physical circumstances [72], and the Arctic NSR is one of these cases. However, the competence of the employed experts is essential for scientific conclusions. According to the study of [34], the selection criteria used for capable experts in this research can be described as follows:

- A heterogeneous group of experts is usually preferred to a homogenous group. In a heterogeneous group, the individual experience of each expert receives considerable attention;

- With respect to the education and experience of the experts in a field, the longer they have focused on a subject (academic or practical subject), the more accurate their intuitionistic judgement is;

- With respect to expert familiarity with a subject, especially through practical experience, an experienced specialist can theoretically master every detail of the subject.

Based on the abovementioned criteria, a heterogeneous group of five experts (their information is listed in Table 7) was developed to comment on the various disruption and resilience capacities associated with the Arctic NSR.

Table 7.

Details of the experts.

The weight for each expert was assessed based on their education level, expertise, professional position, work experience, and age [46,73,74,75]. In addition, the competency certificate level of the selected experts was also regarded as an important indicator. Finally, the rating criteria were developed, as presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Scores of indicators for expert evaluation.

Based on the information from the employed experts shown in Table 7, the capacity was first scored by every individual expert according to the rating criteria presented in Table 8; then, pairwise comparison matrices were derived. Finally, the weight for each expert was obtained by applying Formulas (8)–(11), as summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Evaluation results of expert capabilities.

3.4.2. Calculation of the Prior Probabilities of the Nodes without Parent Nodes

Based on the qualitative analysis discussed in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, there are a total of 30 parent nodes included in the established Bayesian network illustrated in Figure 5. The prior probabilities of these parent nodes can be calculated according to the calculation procedures mentioned in Section 2.2.1. The experts involved in this process are considered independently during decision making. The results of the aggregation and defuzzification of expert judgements are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Aggregation results for each Boolean variable based on expert elicitation.

3.4.3. Calculation of the Condition Probability Table for the Network

To obtain the conditional probability table for the nodes with multiple parents, the leaky Noisy-OR function is applied considering that the states of child nodes may be false even if all the parent nodes are true. Based on the calculated connection probability, , for each parent node, the Leaky Noisy-OR function can be expressed as:

where represents the leaky factor, indicating the degree to which the missing causal factors contribute to a consequence being true. Generally, the leaky factor is a nonzero probability, even if all the causal factors are false. Therefore, the leaky factor represents a probability that implies that the child node will be true if the parent nodes are false, as expressed below.

In the present study, five experts with attributes described in Section 3.4.1 were employed to give their judgements regarding the conditional probabilities of nodes with multiple parent nodes in the form of linguistic expressions. The expert insights were further processed based on the fuzzy methodology proposed in Section 2.1, after which the conditional probabilities for child nodes can be expressed by the Noisy-OR function as follows:

The conditional probability table for the proposed Bayesian network can be induced by combining the Noisy-OR function of child nodes with Equation (26). To concisely represent the computing process for the CPT, the node “service out of order” () with three parent nodes () was taken as an example, and the exhaustive information is given in Table 11.

Table 11.

Calculation process for the conditional probabilities of the node “nav. service out of order”.

3.5. Resilience Quantification

Many studies have been performed to evaluate the resilience of a specified system, and different models have been proposed to quantify system resilience. In the present study, the model developed by [28] is utilized to measure the resilience of Arctic Northeast Route security. Specifically, resilience is defined as the ratio of the recovery capacity to the loss capacity of the system, which can be expressed by:

In the present study, the loss capacity variable of the system is conditioned based on three variables, namely, the probability of disruption occurrence (PDO), the absorptive capacity, and the actual security capacity (ASC). In practice, the loss capacity is greatly dependent on the degree to which the absorptive capacity is capable of withstanding the system shocks caused by disruptions; that is, the probability of the absorptive capacity being in a true state. If the state of the absorptive capacity is true (the probability is 100%), then the loss capacity will be zero. The actual security capacity is set as a constant in the present study because both the absorptive capacity and recovery capacity are associated with the actual security capacity in the expression of the resilience measurement. Therefore, the loss capacity can be obtained according to Table 12.

Table 12.

Conditional calculation of the loss capacity.

The recovery capacity of the system is dependent on the effectiveness of the post-disruption strategy (the combination of the adaptive capacity and restorative capacity) and the degree of the Loss Capacity (LC). If the post-disruption strategy is fully effective, that is, the state of the post-disruption strategy is true, the security system will recover 85% of the loss capacity; otherwise, the value will be zero. Therefore, the recovery capacity can be calculated according to Table 13.

Table 13.

Conditional calculation of the recovery capacity.

4. Results and Discussion

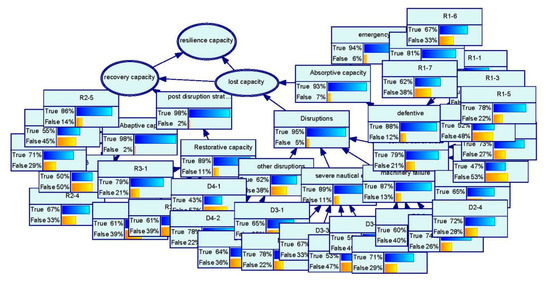

The resilience level of the developed Arctic Northeast Route security system can be evaluated quantitatively based on the fuzzy Bayesian Network, and the expected resilience is 78.5%, as shown in Figure 9. In this section, we will conduct various types of analyses, such as belief propagation, sensitivity, and uncertainty analyses, based on the Bayesian network structure, as depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The base model of BN used to measure the resilience of the NSR.

4.1. Belief Propagation Analysis

Bidirectional reasoning and probabilistic inference can be performed in the Bayesian network by updating evidence formation, which is called “propagation analysis” [76]. Generally, propagation analysis in Bayesian networks includes forward-propagation analysis and backward-propagation analysis. The former is basically a cause-to-effect analysis in which the parent nodes measure their impact on the child nodes, and the latter is widely applied to update the probability distribution of the parent nodes for certain specified states of the target nodes.

As with forward-propagation analysis, three disruptive scenarios are defined to observe the corresponding impacts on system resilience and the decomposed capacities. The scenario description and BN inference results are presented in Table 14. In Scenario 1, it is observed that there is a lack of skilled seafarer teams (the state of (R1-2) is false), which reduces the absorptive capacity of system resilience from 93.4% to 89.2%; eventually, the resilience of the system descends to 78.1% from 78.5% in the base model. Scenario 2 simulates the case of two contributing factors in which the skilled seafarer team and the information prediction service are unavailable (the states of (R1-2) and (R2-2) are set as false). The results show that both the adaptive capacity and system resilience are reduced, the former from 98% to 94% and the latter from 78.5% to 77.8%, respectively. In Scenario 3, another contributing factor is considered on the basis of Scenario 2, that is, the state of a new factor, namely, the rescue and anti-pollution facility (R3-1) is further defined as false. After simulating the developed BN model, the results indicate that the resilience of the NSR suffers from the most notable effect, decreasing to 75.9%, while the restorative capacity is lowered to 65.7% from 88.2%. A general insight obtained from the forward-propagation analysis indicates that all individual capacities are critical for the development of the resilience of the NSR.

Table 14.

Different scenario sets for forward-propagation analysis.

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is one of the characteristic features of the application of BNs in identifying the most important independent variable(s) based on a particular dependent variable under a given set of conditions [77]. Herein, GeNIe 2.3 software is applied to simulate the established BN model and investigate the extent to which the parent nodes differ from the target nodes.

In the present study, the fuzzy ratio of variation (RoV) associated with the prior and posterior probabilities is calculated according to Equation (33) to evaluate the desired probability level of the contributing variables.

where denotes the ith contributing factor and and represent the posterior and prior probabilities of , respectively. Actually, all the parent nodes in the Bayesian network can theoretically be analyzed.

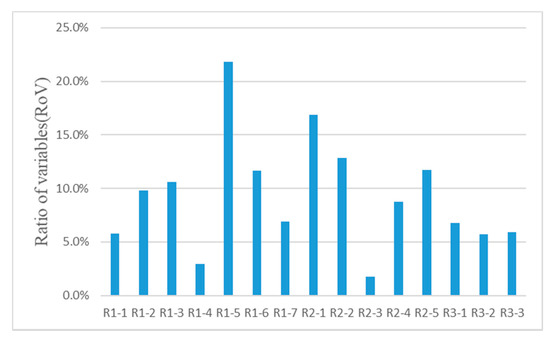

As discussed in Section 3.3, the NSR system resilience is mainly represented by the absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity. Therefore, in this section, we will set these individual capacities as the target nodes to investigate the corresponding effects of the contributing factors. Deductive reasoning is applied to update the probabilities of the contributing factors for the resilience related to the occurrence of the individual capacity (absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, or restorative capacity), and then the value of the ratio of variation can be obtained by Equation (33). Finally, the results of the sensitivity analysis are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Sensitivity analysis for the absorptive capacity.

Figure 10 shows the effects of individual contributing factors on the corresponding capacity. For the absorptive capacity, when the state is set as “true”, it is obviously found that the contributing factor “skilful emergency response” (R1-5) has the most important influence on the desired absorptive capacity; moreover, the “well-coordinated with tugs” (R1-4) has the lowest impact on the improvement of the absorptive capacity. When the state of the adaptive capacity is set as “true”, after updating the probabilities of parent nodes, we can obtain the values of RoV for the contributing factors, as shown in Figure 7, from (R2-1) to (R2-5). Similarly, the results indicate that the “ice-breaking capacity” has the highest influence on the expected adaptive capacity, and the “information prediction service” ranks second; however, the effect of the “preparedness for arctic shipping” on the adaptive capacity is almost negligible. For the restorative capacity, there is no evident difference among the three contributing factors, and the “rescue and anti-pollution facility” (R3-1) may be characterized as the most potential influence on the restorative capacity.

4.3. Uncertainty Analysis Based on Information Entropy Theory

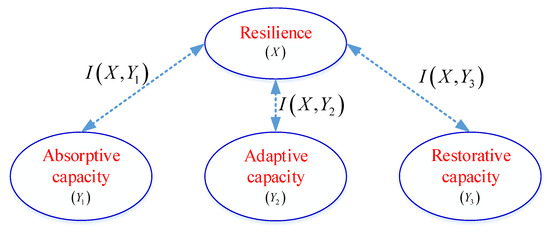

Based on the discussion in Section 3.3, theoretically, the NSR security system is conditionally dependent on the absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity, which can be illustrated as shown in Figure 11. Actually, there is no direct and obvious causal relationship between system resilience and the decomposed capacities based on the analysis of the fuzzy Bayesian network. The system resilience and its supporting capacities are connected by the dotted line in Figure 8.

Figure 11.

Mutual information links between resilience and the corresponding decomposed capacities.

As shown in Figure 11, the system resilience is set as the target variable , and the decomposed absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity are regarded as , , and , respectively. In this section, , , and are set as the predictive variables (predictor) associated with system resilience . The predictive importance of each predictor can be determined by calculating the entropy and mutual information , and the most important predictor will provide maximum information gain for system resilience.

The prior probability of system resilience can be obtained by simulating the developed Bayesian network as:

Then, the entropy of system resilience can be calculated by:

where the conditional entropies and are unknown terms to be solved according to the developed Bayesian network. Notably, the state of the absorptive capacity in the network is set as “true” and “false”, and the BN is simulated with GeNIe 2.3 software; the conditional entropy can be calculated as:

By substituting the results of Equations (37), (40) and (41) into Equation (39), we are able to obtain the conditional entropy of by:

Finally, the mutual information between and can be evaluated based on the results of Equations (38) and (42) by:

In the framework of information entropy, the result obtained from Equation (40) indicates that the absorptive capacity can reduce the uncertainty of system resilience by approximately 32.2%; that is, if we have good knowledge associated with the absorptive capacity, the extent of uncertainty of the system resilience can be reduced by 32.2%. Similarly, the conditional entropy and mutual information of the adaptive capacity and restorative capacity can also be calculated. Finally, the results for all three capacities obtained from information entropy theory are listed in Table 15.

Table 15.

Summary of the information entropy analysis.

Based on the information presented in Table 15, by comparing the values of mutual information between system resilience and its three supporting capacities, it can be observed that the absorptive capacity of system resilience is able to reduce the extent of uncertainty regarding the resilience level of the NSR, and the restorative capacity is the least valuable in reducing the uncertainty of the resilience level. Generally, the results of the present study agree with the general belief that the absorptive capacity is complex and expandable and that the restorative capacity is not as difficult to identify. The result of can be used by the related authorities and organizations to focus on theabsorptive capacity with regard to obtaining a better understanding of NSR resilience because the uncertainty of resilience is mainly related to the absorptive capacity.

5. Conclusions

The present work attempts to propose a comprehensive framework by which the safety level of the NSR can be improved. The safety level of the NSR is a common concern for mariners, authorities, and related organizations. Although huge endeavors have been made, the safety level of the NSR is still far from being satisfied. In the present study, system resilience is introduced to analyze the NSR safeguard capacity. Based on the existing studies about system resilience, the resilience capacity of the NSR is decomposed into three capacities: absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and restorative capacity. Then, we identify the contributing factors pertaining to these capacities. Moreover, the disruptions to the NSR are also identified. Next, all the identified disruptions, contributing factors, and capacities are regarded as nodes in the BN and, as a result, a BN model is developed. The prior probabilities for the nodes without parents and the CPT for the network inference are obtained by the fuzzy methodology proposed by [34]. Finally, the established BN model is simulated with GeNIe 2.3 software, and a sensitivity analysis and an information entropy analysis are conducted with regard to the results obtained from the simulation. Overall, the present study provides a resilience perspective to understand and evaluate the NSR safety issue, which can be seen as the main innovation of this work. The analysis framework proposed in the present study can improve our understanding of the system resilience of the NSR and aid in mitigating disruptions to the NSR.

Although the framework proposed in the present study is demonstrated to effectively quantify and interpret the resilience of the NSR, the structure of the proposed BN can be optimized based on additional information from experts and stakeholders. In addition, the resilience level of the system is generally regarded as a variable that changes over time; therefore, in the future, potential work can be devoted to improving the performance of resilience modelling for the NSR based on the framework given in the present study. The work associated with the abovementioned issues remains in progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and project administration, X.M.; Methodology, W.Q.; investigation, Y.L.; Writing, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China, grant numbers are 19BZZ104 and 20VHQ012. The APC was funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 3132019190).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gascard, J.-C.; Riemann-Campe, K.; Gerdes, R.; Schyberg, H.; Randriamampianina, R.; Karcher, M.; Zhang, J.; Rafizadeh, M. Future sea ice conditions and weather forecasts in the Arctic: Implications for Arctic shipping. Ambio 2017, 46, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Q. How will the opening of the northeast Sea Route influence the Suez Canal Route? An empirical analysis with discrete choice models. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2018, 107, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøyen, H.; Bråthen, S. The Northern Sea Route versus the Suez Canal: Cases from bulk shipping. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, J.J. Corporate engagement in the age of Arctic development and its implications for Chinese Corporations. J. Ocean Univ. 2017, 2, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Using interpretive structural modeling and fuzzy analytic network process to identify and allocate risks in Arctic shipping strategic alliance. Polar Sci. 2018, 17, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, W.-H.; Ding, J.-F. Key Factors Influencing the Building of Arctic Shipping Routes. J. Navig. 2016, 69, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, Y.E.; Aydogdu, Y.V.; Sahin, B.; Kilic, I. Fault Tree Analysis of chemical cargo contamination by using fuzzy approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 5232–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Goerlandt, F.; Yan, X.; Kujala, P. Use of HFACS and fault tree model for collision risk factors analysis of icebreaker assistance in ice-covered waters. Saf. Sci. 2019, 111, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerlandt, F.; Goite, H.; Banda, O.A.V.; Höglund, A.; Ahonen-Rainio, P.; Lensu, M. An analysis of wintertime navigational accidents in the Northern Baltic Sea. Saf. Sci. 2017, 92, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, S.; Sahin, B. A root cause analysis for Arctic Marine accidents from 1993 to 2011. Saf. Sci. 2015, 74, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh, A.A.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F. Marine transportation risk assessment using Bayesian Network: Application to Arctic waters. Ocean Eng. 2018, 159, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalonen, R.; Riska, K.; Hanninen, S. A Preliminary Risk Analysis of Winter Navigation in the Baltic Sea; Finnish Maritime Administration: Helsinki, Finland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kujala, P.; Hänninen, M.; Arola, T.; Ylitalo, J. Analysis of the marine traffic safety in the Gulf of Finland. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2009, 94, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Designing Resilient, Sustainable Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5330–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D.D.; Leveson, N. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational resilience: Towards a theory and research agenda. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–10 October 2007; pp. 3418–3422. [Google Scholar]

- Gilberto, C.G. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Smale, S. Assessing Resilience and Vulnerability: Principle, Strategies and Actions. Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 403–419. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, K.E.; Warner, J.F. Resilience in Talcahuano, Chile: Appraising local disaster response. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 28, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, M.; Mariano, C.; Teresa, M.; Madonna, M. An adaptive resilience approach for a high capacity railway. Int. Rev. Civ. Eng. 2020, 11, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoh-Okine, N.O.; Cooper, A.T.; Mensah, S.A. Formulation of Resilience Index of Urban Infrastructure Using Belief Functions. IEEE Syst. J. 2009, 3, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.U.I.; Jaradat, R.; Hosseini, S.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Buchanan, R. A framework for modeling and assessing system resilience using a Bayesian network: A case study of an interdependent electrical infrastructure system. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2019, 25, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.U.I.; Amrani, S.E.; Jaradat, R.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Buchanan, R.; Rinaudo, C.; Hamilton, M. Modeling and assessing interdependencies between critical infrastructures using bayesian network: A case study of inland waterway port and surrounding supply chain network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 198, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.U.I.; Nur, F.; Hosseini, S.; Jaradat, R.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Puryear, S.M. A Bayesian network based approach for modeling and assessing resilience: A case study of a full service deep water port. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 189, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugrin, E.D.; Warren, D.E.; Ehlen, M.A. A resilience assessment framework for infrastructure and economic systems: Quantitative and qualitative resilience analysis of petrochemical supply chain to a hurricane. Process Saf. Progr. 2011, 30, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.; Ramirez-Marquez, J.E. Generic metrics and quantitative approaches for system resilience as a function of time. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012, 99, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.L.; Smith, C.L. Bayesian inference in probabilistic risk assessment? The current state of the art. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2009, 94, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, N.; Neil, M. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayaka, S.; Khan, F.; Amyotte, P. SHIPP methodology: Predictive accident modeling approach. Part II. Validation with case study. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2011, 89, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakzad, N.; Khan, F.; Amyotte, P. Safety analysis in process facilities: Comparison of fault tree and Bayesian network approaches. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakzad, N.; Khan, F.; Amyotte, P. Dynamic risk analysis using bow-tie approach. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012, 104, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.L.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.X.; Liu, Y. Human Factors Analysis for Maritime Accidents Based on a Dynamic Fuzzy Bayesian Network. Risk Anal. 2020, 1, 13444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Barker, K. A Bayesian network model for resilience-based supplier selection. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 180, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundson, J.; Faulkner, W.; Sukumara, S.; Seay, J.; Badurdeen, F. A Bayesian Network Based Approach for Risk Modeling to Aid in Development of Sustainable Biomass Supply Chains. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2012, 30, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Y.; Marais, K.; de Laurentis, D. Evaluating System of Systems resilience using interdependency analysis. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Seoul, Korea, 14–17 October 2012; pp. 1251–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.; Barker, K. Modeling infrastructure resilience using Bayesian networks: A case study of inland waterway ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 93, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laarhoven, P.; Pedrycz, W. A fuzzy extension of Saaty’s priority theory. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1983, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.-Y. Applications of the extent analysis method on fuzzy AHP. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 95, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 101, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolis, J.S.; Tsuda, I. Chaotic dynamics of information processing: The “magic number seven plus-minus two” revisited. Bull. Math. Biol. 1985, 47, 343–365. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.J.; Hwang, C.L. Fuzzy Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications, Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems, No. 375; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzali, N.; Lavasani, M.R.M.; Ghodousi, J. Safety barriers analysis of offshore drilling system by employing Fuzzy Event Tree Analysis. Saf. Sci. 2015, 78, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Bhattacharya, J. Reliability Analysis of a conveyor system using hybrid data. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2007, 23, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvari, M.; Lavasani, S.; Mirza, S. Presenting of failure probability assessment pattern by FTA in Fuzzy logic (case study: Distillation tower unit of oil refinery process). J. Chem. Health Saf. 2014, 21, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.; Yazdi, M.; Aizpurua, J.I.; Papadopoulos, Y. Uncertainty-Aware Dynamic Reliability Analysis Framework for Complex Systems. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 29499–29515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.L.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.X.; Liu, Y. A methodology to evaluate human factors contributed to maritime accident by mapping fuzzy FT into ANN based on HFACS. Ocean Eng. 2020, 197, 106892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.J. Fuzzy hierarchical analysis. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1985, 17, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.V.; Nielsen, T.D. Bayesian Networks and Decision Graphs; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, S.; Papadopoulos, Y. Applications of Bayesian networks and Petri nets in safety, reliability, and risk assessments: A review. Saf. Sci. 2019, 115, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, F.V.; Nielsen, T.D. Bayesian Networks and Decision Graphs, 2nd ed.; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.F.; Xie, M.; Chin, K.S.; Fu, X.J. Accident analysis model based on Bayesian Network and Evidential Reasoning approach. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2013, 26, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, E.; Khakzad, N.; Cozzani, V.; Reniers, G. Safety analysis of process systems using Fuzzy Bayesian Network (FBN). J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2019, 57, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka, O. Learning Bayesian Network Parameters from Small Data Sets Application of Noisy-OR Gates. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2001, 27, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, B.; Brigham, L. 2009: Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report. Arctic Council Rep., 189p. Available online: https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/54 (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Zakharov, V.F. Sea Ice in the Climate System: A Russian View; NSIDC Special Report 16; NSIDC: Boulder, CO, USA, 1997; Available online: https://nsidc.org/pubs/special/16/NSIDC-specialreport-16.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Royal Institution of Naval Architects. Safety Guidance for Naval Architects. Second Editions. 2010. Available online: http://www.rina.org.uk/hres/safety%20guidance%20for%20naval%20architects%20_%20second%20edition%20_%20march%202010%20_%20final%20inc%20tb%20edits.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Lloyd’s Register. Written Evidence (ARC0048). Lloyd’s Register. 2015. Available online: https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/lords-committees/arctic/Lloyds-Register-ARC0048.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Afenyo, M.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B.; Yang, M. Arctic shipping accident scenario analysis using Bayesian Network approach. Ocean Eng. 2017, 133, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhang, D.; Montewka, J.; Zio, E.; Yan, X. A quantitative approach for risk assessment of a ship stuck in ice in Arctic waters. Saf. Sci. 2018, 107, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, B.; Kum, S. Risk Assessment of Arctic Navigation by Using Improved fuzzy-AHP Approach. Int. J. Marit. Eng. 2015, 157, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, W.D.; Tetu, P.L.; Dawson, J.; Insley, S.J.; Hilliard, R.C. Tourist vessel traffic in important whale areas in the western Canadian Arctic: Risks and possible management solutions. Mar. Policy 2018, 97, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D.J.; Pitman, N.D.; Basak, S.; Wunsche, B.C. Sketch-Based Building Modelling. Graphics Group Technical Report #2011-002, Department of Computer Science, University of Auckland. 2011. Available online: http://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/burkhard/Reports/GraphicsGroupTechnicalReport2011_002.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Stoddard, M.A.; Etienne, L.; Fournier, M.; Pelot, R.; Beveridgle, L. Making sense of Arctic maritime traffic using. The Polar Operational Limits Assessment Risk Indexing System (POLARIS). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 34, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Fu, S.; Yan, X.; Goncharov, V. Safety distance modeling for ship escort operations in Arctic ice-covered waters. Ocean Eng. 2017, 146, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B.; Yang, M. An operational risk analysis tool to analyze marine transportation in Arctic waters. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 169, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaković, A.-S.; Gunnarsson, B.; Balmasov, S.; Hong, S.; Kim, K.; Schütz, P.; Ehlers, S. Current status and future operational models for transit shipping along the Northern Sea Route. Mar. Policy 2018, 94, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Economic Resilience to Disasters, Community and Regional Resilience Initiative Research Report 8. 2009. Available online: http://www.resilientus.org/library/Research_Report_8_Rose_1258138606.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Maritime Safety Administration of China. Guidance on Arctic Navigation in the Northeast Route; China Comm Press: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Biringer, B.; Vugrin, E.; Warren, D. Critical Infrastructure System Security and Resiliency; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi, M.; Daneshvar, S.; Setareh, H. An extension to fuzzy developed failure mode and effects analysis application. Saf. Sci. 2017, 98, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, M.; Lavasani, S.M.; Wang, J. A risk-based modelling approach to enhance shipping accident investigation. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri-Lavasani, M.R.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Finlay, J. Application of fuzzy fault tree analysis on oil and gas offshore pipelines. Int. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2011, 1, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lavasani, S.M.; Zendegani, A.; Celik, M. An extension to Fuzzy Fault Tree Analysis (FFTA) application in petro-chemical process industry. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2015, 93, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, N.; Neil, M.; Lagnado, D.A. A general structure for legal arguments about evidence using Bayesian networks. Cogn. Sci. 2013, 37, 61–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salteli, A.; Chan, K.; Scott, E.M. Sensitivity Analysis; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).