Abstract

Recently, the JPEG working group (ISO/IEC JTC1 SC29 WG1) developed an international standard, JPEG 360, that specifies the metadata and functionalities for saving and sharing 360-degree images efficiently to create a more realistic environment in various virtual reality services. We surveyed the metadata formats of existing 360-degree images and compared them to the JPEG 360 metadata format. We found that existing omnidirectional cameras and stitching software packages use formats that are incompatible with the JPEG 360 standard to embed metadata in JPEG image files. This paper proposes an easy-to-use tool for embedding JPEG 360 standard metadata for 360-degree images in JPEG image files using a JPEG-defined box format: the JPEG universal metadata box format. The proposed implementation will help 360-degree cameras and software vendors provide immersive services to users in a standardized manner for various markets, such as entertainment, education, professional training, navigation, and virtual and augmented reality applications. We also propose and develop an economical JPEG 360 standard compatible panoramic image acquisition system from a single PTZ camera with a special-use case of a wide field of view image of a conference or meeting. A remote attendee of the conference/meeting can see the realistic and immersive environment through our PTZ panorama in virtual reality.

1. Introduction

The use of images from multi-sensor devices such as multi-camera smartphones and 360-degree capturing cameras is increasing. Such devices are now widely available to consumers with various applications [1,2]. A 360-degree image covers the omnidirectional scene, which is created by stitching images captured by multiple sensors or cameras and mapping them onto a 2D plane through a projection method. Several software packages are used to stitch images to 360-degree images. Today, with millions of engaged users, 360-degree images and videos have gained immense popularity. There are many benefits of 360-degree images. Users can feel like they are on-site while off-site, enabling better decision making, reducing the need for costly visits, and minimizing confusion and ambiguity. The 360-degree images are used for training [3], tourism and marketing [4], entertainment, education [5], navigation, virtual and augmented reality applications [6], etc. There are many websites where 360-degree images are provided in spherical forms. In addition, there are many viewer software packages available for use in viewing 360-degree images. Some viewers are developed by camera makers; others are developed by third-party software developers. Many web-based players are also available for use in viewing 360-degree images.

Viewers of 360-degree images must distinguish 360-degree image files from regular image files. The most straightforward approach is to check the metadata in files. The 360-degree-image-related metadata are added to the image file in different formats depending on the capturing device. Some capturing devices add metadata using the embedded software provided by the manufacturer. For other devices, the addition of metadata is carried out by external software packages. Different devices and software packages use different formats for embedding metadata. Capturing devices provide images in different file formats such as RAW, JPEG, PNG, BMP, GIF, TIFF, etc. The JPEG format, herein referred to as JPEG-1, has been market-dominant since its introduction to the market [7]. In the JPEG-1 image file format, application markers add metadata in images [8].

Image metadata play important roles in different aspects, such as image classification [9] and the digital investigation process [10]. Similarly, in omnidirectional images, metadata play a role in providing immersive and realistic feelings to the viewer. JPEG Systems, with multiple part specifications, is an international standard designed primarily for metadata storage and protection methods for compressed continuous-tone photographic contents [11]. Table 1 shows the status of each part of the JPEG Systems with the respective International Standardization Organization (ISO) project numbers. Part 5 defines the JPEG universal metadata box format (JUMBF). It defines special content type boxes and the syntax to embed or refer to generic metadata in the JPEG image files. JUMBF is a box-based universal format for various types of metadata [12]. Part 6 defines the use of the JPEG 360 Content Type JUMBF super box and defines the structure and syntax of an extensible markup language (XML) box for 360-degree image metadata [13]. The ISO/IEC 19566-6 (JPEG 360) is the standard for 360-degree images and builds upon the features of JUMBF, which provides a universal format to embed any type of metadata in any box-based file format. JUMBF itself is built on the ISO/IEC box file format 18477-3, and it provides compatibility with JPEG File Interchange Format (JFIF) on ISO/IEC 10918-5 [14].

Table 1.

Status of JPEG Systems ISO projects.

Various smartphones and digital cameras have been released to easily capture and share our daily lives in the current consumer electronics market. However, since these devices store images along with metadata defined in different formats, it is necessary to convert the form of metadata included in the image into the form required by the application providing the service for virtual reality (VR) or 360-degree image services. To discard this unnecessary conversion of metadata formats, the JPEG working group (WG) developed the JPEG 360 international standard to guarantee the use of standardized metadata from the image-acquisition stage. In this context, as previously pointed out, the conversion of numerous images existing in the JPEG-1-dominant digital imaging environment to JPEG 360 is regarded as an essential task in continuing existing consumers’ applications and services. The 360-degree images or panorama-generation systems and algorithms proposed in the literature mostly did not care about the metadata. Without proper metadata, the real purpose of such images cannot be achieved. To the best of the authors‘ knowledge, such an approach of implementing the emerging international standard has not been attempted before. Our work enables the transformation of a large amount of legacy 360-degree images into the standardized format, which provides a market to use the format in a standard way, which was a goal of developing the JPEG 360 standard. In this work, we also propose a low-cost panorama-acquisition system from a single pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) camera. Our PTZ panorama application is the practical use case of our converter. The panorama will be compatible with the JPEG 360 standard and help consumers in situations such as capturing a wide field of view image of a conference or meeting. These days, because of COVID-19, virtual and online meetings/conferences have replaced face-to-face meetings [15,16,17]. We believe that if our PTZ panorama, with proper metadata values in the standard format, are shared with a remote attendee of a conference/meeting, he/she can see the realistic and immersive environment by viewing our PTZ panorama virtually.

This paper presents the implementation of JPEG 360 to convert conventional 360-degree images to standard JPEG 360 images and the acquisition of the standard JPEG 360 panorama using a single PTZ camera. Section 2 presents a brief overview of related work. In this section, we introduce the JPEG-1 image coding standard and the JPEG-1 file structure. We also introduce standard formats used for embedding application-specific metadata to a JPEG-1 file. In Section 3, we describe existing methods that 360-degree cameras and services use to embed related metadata in image files as the output of our survey on metadata related to spherical images and introduce our conversion algorithm. Our panorama-generation system is also introduced in this section. In Section 4, the implementation of the JPEG 360 converter and PTZ panorama is described. Section 5 discusses the results. The last section concludes this paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Literature Review

As VR contents are increasingly used in many applications, research on the creation and processing of the contents is also growing. In addition, 360-degree image and video acquisition sensors are now easily accessible for consumers, which has gained the attention of researchers for use in generating high-quality images.

Duan et al. [18] introduced an interesting study generating panoramas from a two-dimensional sketch and proposed a spherical generative adversarial network (GAN) system for stitching. The sketch, a concise geometric structure comprising about 7% of the panoramic image, created a high-fidelity spherical image. Bertel et al. [19] introduced a compact approach to capture high-quality omnidirectional panorama images with motion parallax. They captured a 360-degree video using a handheld 360-degree video camera with a selfie stick by rotating it for 3 or 10 s. They improved the visual quality by improving the vertical distortion using deformable proxy geometry. Akimoto et al. [20] proposed a GANs network to stitch a 360-degree image from its parts. They used a two-stage approach with series-parallel dilated convolution layers. The result showed many distortions in the output 360-degree image, as their approach is the initial step to generate a 360-degree image from an unseen area input. Similarly, H. Ullah et al. [21] focused on cost effectiveness and proposed a low-cost mono and stereo panorama automatic stitching system. For a mono omnidirectional image, they presented a sensor kit mounted on a drone consisting of six cameras. For a stereo omnidirectional image, they proposed a cost-effective visual sensor kit consisting of three cameras. For both systems, they developed their own stitching software to achieve a good-quality image from both the objective and subjective perspective. Berenguel-Baeta et al. [22] presented a tool to create omnidirectional, synthetic, and photorealistic images in various projection formats such as equirectangular, cylindrical, dioptric, and equiangular with labeled information. The tool supports the generation of datasets with depth and semantic information of the panoramas. These panoramas are synthesized from a set of captures in a realistic virtual environment. Their depth and semantic information can be used to train learning algorithms and test 3D vision approaches.

Parallel with the generation of panoramic contents, the processing of such content has also drawn great attention. Researchers and developers process such content for different purposes. Duanmu et al. [23] investigated the behavior of users while watching 360-degree videos and proposed a novel dataset of users’ trajectories. They captured the viewing trajectories of users using twelve 360-degree videos recorded on computers/laptops and compared these computer-based trajectories with the existing head-mounted device (HMD). It is stated that users have almost the same behavior and navigation when wearing an HMD as when they watch 360-degree videos. Zhang et al. [24] studied a quality enhancement of 360-degree images using deep neural networks based on GANs without changing the image resolution. They designed a compact network employing a multi-frequency structure with compressed Residual-in-Residual Dense Blocks and convolution layers from each dense block. Zhu et al. [25] proposed a saliency predictor for panoramas to improve the perceptual experience of the viewer by predicting head and eye movements. They extracted features at different frequency bands and orientations using spherical harmonics in the spherical domain and used these features to predict head and eye movements and estimate the saliency. Adhuran et al. [26] researched coding efficiency. They used the features of weighted Craster parabolic projection PSNR and proposed an algorithm for residual weighting to reduce the residual magnitude for 360-degree video compression. They also proposed a quantization parameter for optimization, which was used to reduce the residuals’ magnitude reduction. They improved coding efficiency by 3.34% on average.

Some researchers also worked to improve VR contents’ quality assessment. To assess the visual quality of the VR image, Kim et al. [27] proposed a VR quality score predictor and human perception guider based on deep-learning methods. They encoded positional and visual information regarding patches to obtain weight and quality scores. They predicted the overall image quality score by aggregating the quality score of patches with a respective weight of patches. Orduna et al. [28] used a full-reference video quality assessment metric: Video Multimethod Assessment Fusion (VMAF) for 360-degree video assessment. They proved that the VMAF is feasible for 360-degree videos without any specific training and adjustment.

Most of the aforementioned studies focused on creating and processing virtual reality content rather than remediating existing content. To the best of our knowledge, our work is a novel approach that has not been addressed in the academia and the JPEG-dominant digital imaging market. As our work is related to metadata in JPEG images, the coding and file format of JPEG are introduced briefly.

2.2. JPEG-1 Image Coding Standard

JPEG stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group and is a joint WG of ISO and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). The JPEG-1 celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2017 and is still dominant in the market [7]. The JPEG-1 image coding standard is the most prominent codec and de facto image format for lossy compressed photographic imagery in digital cameras and on the World Wide Web. Many researchers agree that JPEG-1 leads the art and science of reducing the number of bits required to describe an image. The conventional compression process of JPEG-1 is as follows [8,29]:

First, the input image’s color space, the RGB color space, is converted into luminance (Y) and chrominance (Cb and Cr). Chrominance channels are subsampled. This conversion aims to achieve the maximum energy of the image into the luminance channel, as human eyes are more sensitive to luminance than chrominance. The defined sampling factors are 4:4:4, 4:2:2 horizontal, 4:2:2 vertical, and 4:2:0 for the luminance and chrominance channels. The most used subsampling factor is 4:2:0, in which the chrominance channel resolution is reduced to ¼. That is, for four luminance samples, one chrominance sample is maintained, and the remaining chrominance samples are removed. Discrete cosine transform (DCT) is applied to the partitioned 8 × 8 blocks of each channel, and transform coefficients are calculated. Each coefficient of 8 × 8 blocks of each channel is quantized. Data reduction and consequent data loss occur in this step. Luminance and chrominance channels are quantized separately, with different quantization factors deciding the tradeoff between the data reduction rate and the consequent degree of data loss. The run-length and Huffman entropy coding scheme or arithmetic encoding scheme are the final steps after quantization. In this step, the quantized DCT coefficients are encoded losslessly.

In the decoding process, these steps are performed in reverse order. The encoded data are first decoded into 8 × 8 blocks of quantized DCT coefficients. Dequantization and inverse 2D DCT are followed, and upsampling of Cb and Cr channels is performed based on the sampling factors. Finally, a decoded image is obtained by recovering the color space from YCbCr to the original color space.

2.3. JPEG-1 Image File Structure

The JPEG-1 standard defines a file format to store all the information necessary to decode a codestream. The JPEG-1 file is structured using marker segments, as listed in Table 2. All the parameters that are necessary for decoding are stored in specific markers. A specified marker ID indicates the beginning of each marker segment bitstream. Any number of markers may appear in any order in the JPEG-1 file. Each marker begins with 0xFF, followed by a byte, which indicates a marker type [29]. In the segment, two little endianness formatted bytes follow the marker’s ID bytes, which are the length of the segment. Generally, any type of user data can be embedded in the segment up to 64 K bytes using JPEG-1 markers. Each segment has its own format and structure. Since this paper focuses on the application-specific metadata for converting legacy 360-degree images to JPEG 360 images, not on encoding and decoding related metadata, the related metadata markers are introduced.

Table 2.

List of common jpeg markers.

The JPEG standard specifies the start of the frame (SOF) and defines the Huffman table (DHT), quantization table (DQT), and restart (RSTn) markers for metadata required for decoding the image codestream. It also specifies application (APPn) markers for application-specific uses beyond the JPEG standard’s metadata.

The APP0 marker segment is specified for the JFIF (ISO/IEC 10918-5) format. JFIF is used for the file-based interchange of images encoded according to the JPEG-1 image coding standard [30]. It is mandatory that the JFIF APP0 marker segment follows the start of the image (SOI) marker.

APP1 is also recorded after the SOI marker. If APP1 and APP0 marker segments are both present, then APP1 follows APP0. The APP1 may hold the exchangeable image file format (EXIF) or extendable metadata-platform (XMP)-formatted metadata. It can be identified by the signature string present after the length bytes. EXIF is a standard developed by the Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association.

The APP1 EXIF marker contains a length value and the identifying signature string. The identifying signature string for the APP1 EXIF marker is ‘Exif\0\0’ (0x457896600000). The metadata attribute information in EXIF is stored in a tagged image file format (TIFF) structure [31]. TIFF structure consists of a TIFF header and a maximum of two image file directories (0th IFD and 1st IFD). Compressed primary-image-related information is stored in the 0th IFD. The first IFD may be used for thumbnail images. The IFD header has information about byte order endianness of TIFF bytes and offset values for the first IFD. The IFD structure follows the format consisting of 2 bytes for the number of fields count, the next number of fields count times 12 bytes for the field arrays, and 4 bytes for the next IFD offset value. Each of the 12 bytes fields consists of 2 bytes for a unique tag, 2 bytes for the type, 4 bytes for the count, and 4 bytes for the offset value of the tag [32].

Another APP1 marker designates XMP packets embedded in the JPEG-1 file. Like APP1 EXIF, APP1 XMP must appear before the SOF marker. The APP1 XMP marker also contains the length value and the XMP-indicating name, ‘http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/\0’ (accessed on 1 October 2021). After this indicating name, a UTF-8-encoded XMP packet is present [33]. XMP is an XML/resource-description-framework (RDF)-based metadata format for generating, processing, and interchanging metadata. An instance of the XMP data model is called an XMP packet.

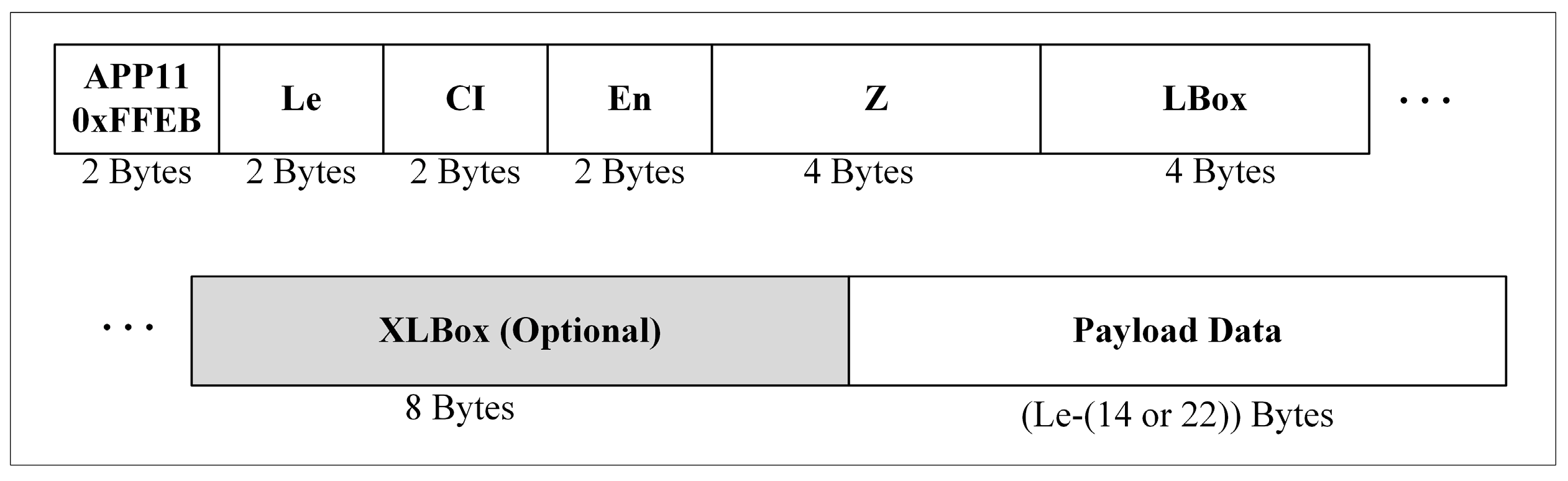

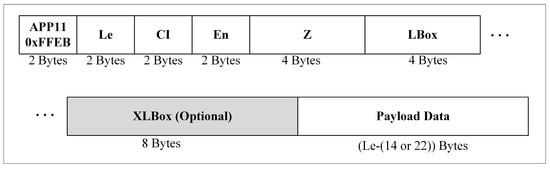

The APP11 marker wraps JPEG XT boxes [14], as shown in Figure 1. Although the JPEG-1 marker segment can carry data not more than 64 K bytes, there is a way that this box can logically carry more than 64 K bytes of payload data. A box with payload data greater than the capacity of the marker can be distributed into several APP11 marker segments. Syntax elements of the marker segment are responsible for instructing the decoder to combine the logically distributed boxes into one box. The ID assigned to the APP11 marker segment is 0xFFEB [34].

Figure 1.

General structure of APP11 marker segment.

In the APP11 marker, the two-byte length (Le) of the complete marker segment, except the marker’s ID, follows the ID bytes. The next two-byte field is the common identifier, which is fixed to ‘JP’ or ‘0x4A50’ The next two-byte field is the box instance (En) number. The number disambiguates payload data of the same box type and defines which payload data are concatenated. The next four-byte field represents the packet sequence number (Z). If the packet sequence number is different and the En is the same as the other APP11 marker segment’s number, then both segments logically belong to the same box.

After Z, the first four-byte field is the box length (LBox), which is the length of the concatenated payload data. If the value of the LBox is 1, it means that an extended box length (XLbox) field exists. The box type is represented by the next four-byte field. Box types define the purpose of the payload data. If the size of the payload data of a box exceeds the capacity of LBox, that is, 4 GB, then the XLbox field is used; otherwise, the XLbox field will not exist. A box is a generic data container that has both types and payload data. Some boxes may also contain other boxes. The box containing other boxes is called a super box.

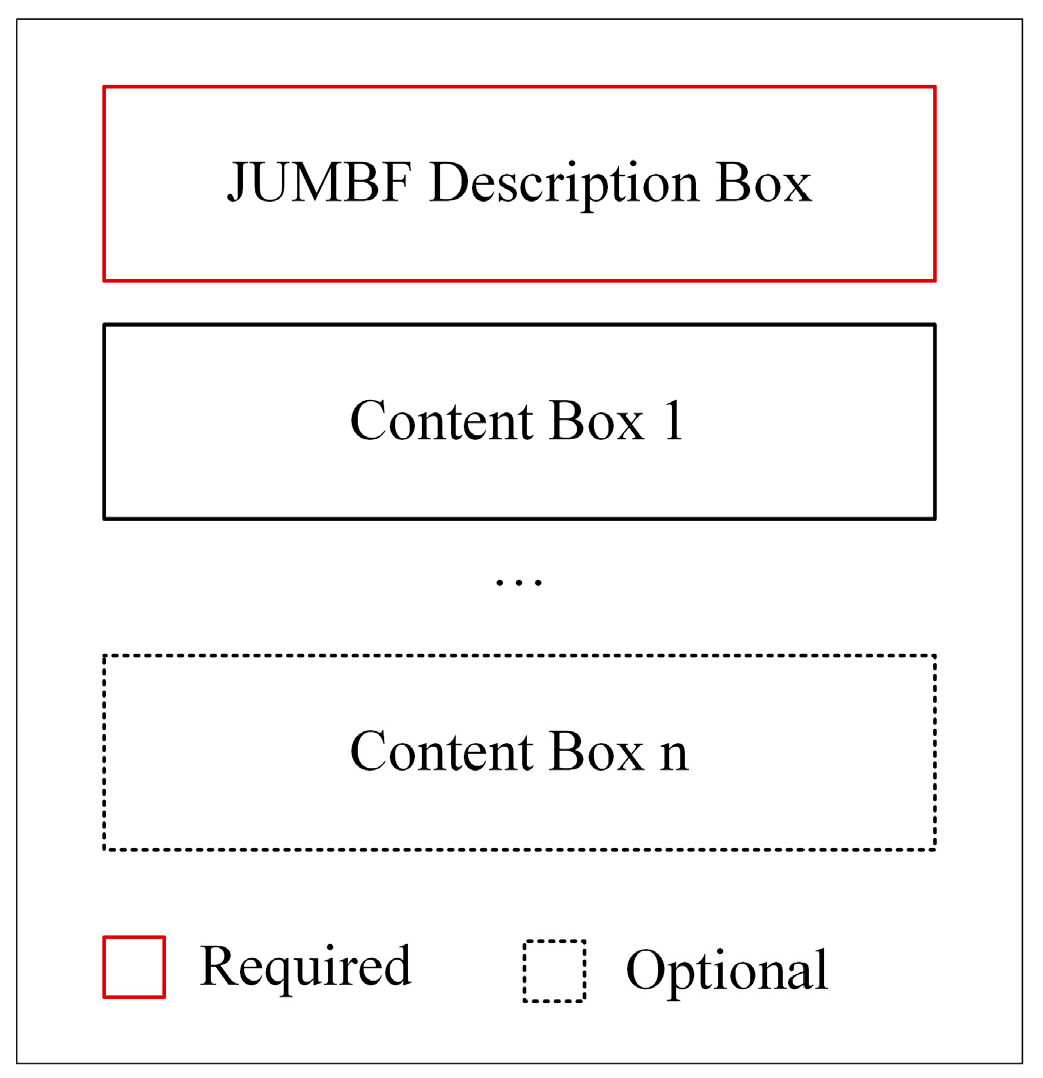

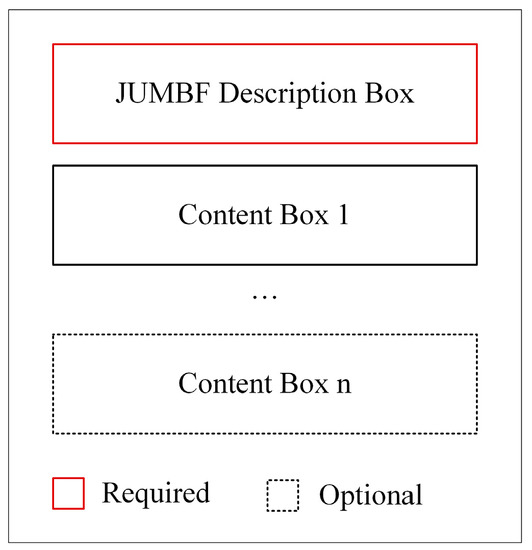

JUMBF provides a universal format for embedding and referring generic metadata in JPEG files. JPEG Systems Part 5 defines the syntax of the JUMBF box and specifies content types such as XML, JSON, Code Stream, and universally unique identifier (UUID). A JUMBF is a super box that contains exactly one JUMBF description box followed by one or more content boxes. Figure 2 presents the structure of the JUMBF super box. The type specified for JUMBF super box is ‘jumb’ (0x6A756D62) [12].

Figure 2.

General structure of JUMBF super box.

The behavior and content of the parent JUMBF box are provided by the JUMBF description box. The type of the description box is ‘jumd’ (0x6A756D64). The contents of the description box are defined as the first 16 bytes of UUID specifying the format of child content boxes in the super box. The next to UUID is a one-byte field, ‘toggle’, which signals the presence of label, ID, and signature fields in the description box. The size of the label field is variable, and ID and signature fields are 4 and 256 bytes in size, respectively. Table 3 lists the currently defined content-type boxes in JPEG Systems. New content type boxes can be defined according to the needs of the JPEG WG or third party.

Table 3.

Currently defined content type boxes in JPEG Systems.

3. Proposed Converter and PTZ Panorama

Several camera vendors produce different omnidirectional camera models. Each camera model has its own features and specifications regarding the image resolution, number of sensors, type of sensors, dynamic range, and stitching of images. Many of them provide images and videos up to 8 K resolution to the end-user. Most of these cameras compress and store images using the JPEG-1 image format. We conducted a survey to understand and compare how camera services or stitching software include 360-degree-image-related metadata in image files.

3.1. Metadata Survey in 360-Degree Images

We conducted a survey to verify how 360-degree related metadata are stored in the JPEG-1 image file by different cameras and stitching software packages. In the survey, we collected 360-degree images captured with different 360-degree cameras or stitched using different stitching software. We analyzed images captured by 22 different cameras and investigated the metadata of each image file for 360-degree-related metadata, and found that all these cameras follow the GPano namespace. The GPano metadata schema is serialized and stored using W3C RDF expressed in XML. The XMP UTF-8-encoded packet is encapsulated in the APP1 marker with the identification signature http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/\0, accessed on 1 October 2021.

3.2. GPano Metadata Schema

GPano is a method used to embed metadata regarding spherical and cylindrical images. It provides the namespace URI http://ns.google.com/photos/1.0/panorama/ (accessed on 1 October 2021), which defines metadata properties [35]. GPano 360-degree-related properties are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

GPano metadata properties.

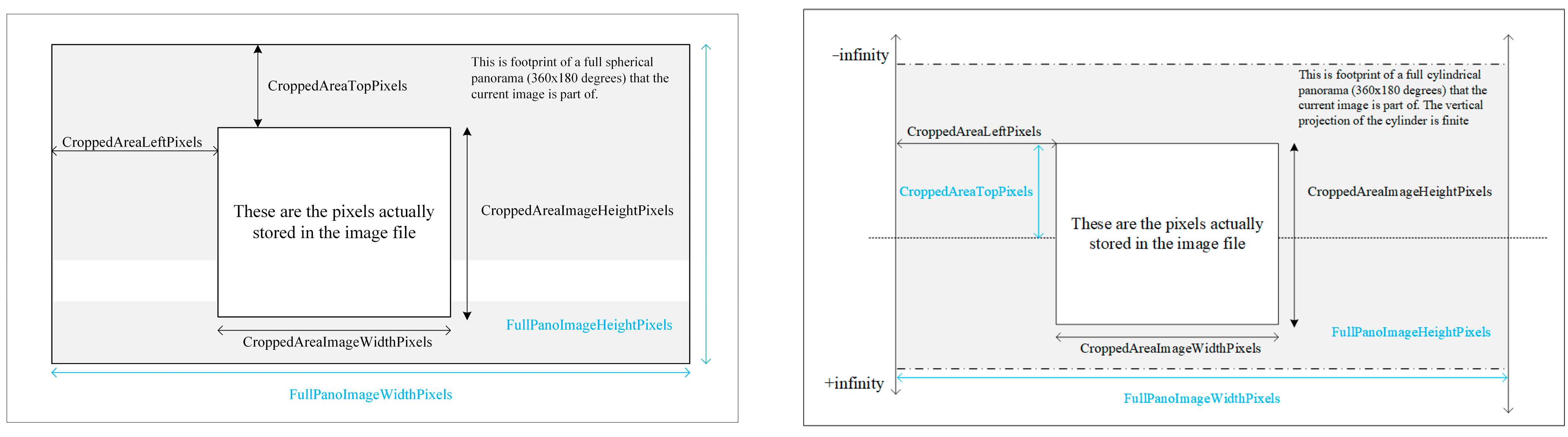

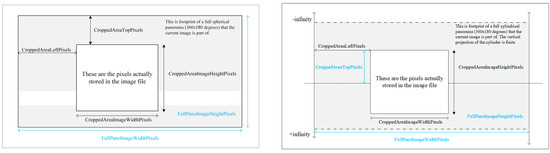

For embedding GPano metadata properties in JPEG images, the JPEG APP1 marker is used with identifying signature ‘http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/\0’ (accessed on 1 October 2021). This signature is present directly after the length field in the APP1 marker, as discussed in Section 2. GPano supports both spherical and cylindrical images. Figure 3 shows the properties of each.

Figure 3.

GPano properties: spherical (left) and cylindrical (right).

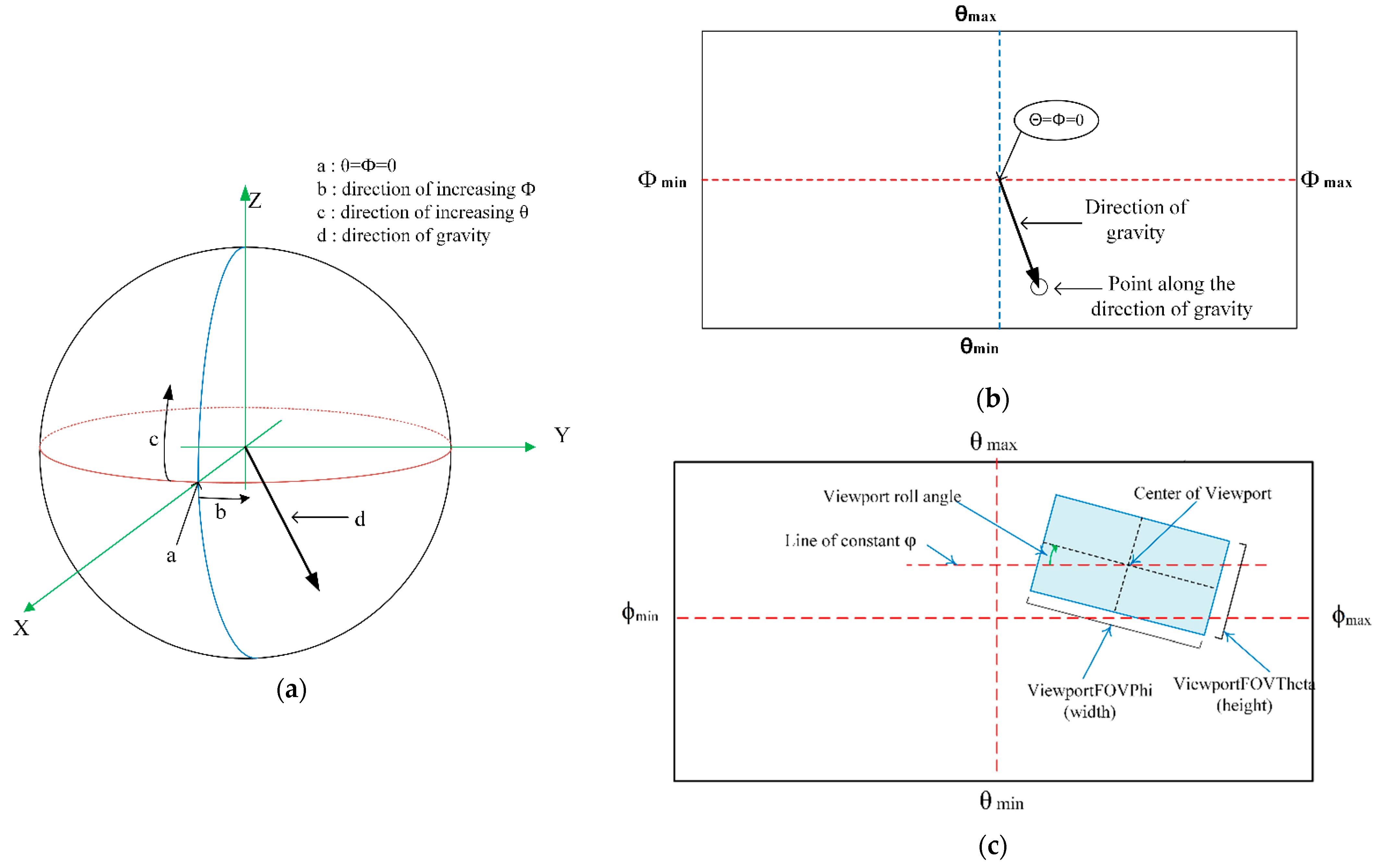

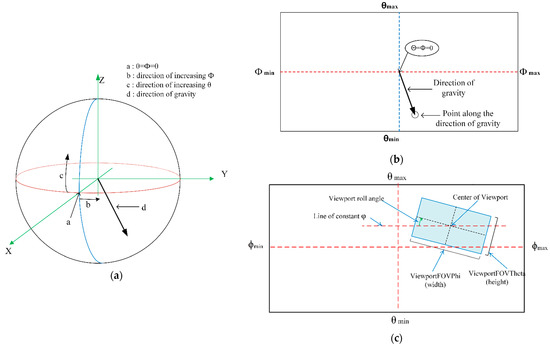

3.3. JPEG 360

JPEG Systems Part 6 defines metadata and functionalities for a 360-degree image in JPEG file format [13]. All properties of the JPEG 360 descriptive metadata are shown in Table 5. The equirectangular projection (ERP) format is the default projection format for JPEG 360, as it is the most-used projection format. JPEG 360 defines ERP as a map from a unit sphere with longitude angle ϕ (phi) and latitude angle θ (theta), as shown in Figure 4. ϕmin, ϕmax, θmin, and θmax are constrained by the following four conditions:

−360° ≤ ϕmin ≤ ϕmax ≤ 360°

ϕmax − ϕmin ≤ 360°

−180° ≤ θmin ≤ θmax ≤ 180°

θmax − θmin ≤ 180°

Table 5.

JPEG 360 metadata properties.

Figure 4.

Graphical overview of ERP image: (a) spherical and cartesian coordinates, (b) generalized description of ERP mapped on 2D plane, and (c) generalized description of the viewport.

A smaller range than the full sphere can be defined by the above-generalized inequalities, and it also helps to shift the origin (0,0) of the image according to the angle values range. Additionally, JPEG 360 deals with the situation when the camera is not held upright, and the direction of gravity is shifted relative to the camera’s coordinate systems. A vector from the center to the point (ϕ gravity, θ gravity) is used for the Earth’s gravity, as shown in Figure 4.

JPEG 360 defines the subregion of ERP as a viewport. The viewport is a limited region of the 360-degree image to be presented to the viewer. The colored area in Figure 4c represents an example of the viewport. JPEG 360’s viewport information helps the viewer select the initial region in the ERP image for rendering first. Metadata properties ‘ViewportPhi’ and ViewportTheta’ are coordinates of the center of the viewport. ViewportPhiFOV and ViewportThetaFOV are the width and height of the viewport, respectively. JPEG 360 also supports a viewport with edges not parallel to the edges of the ERP. ViewportRoll is the rotation angle between a line-of-constant Phi through the viewport center point and the center line of the viewport. JPEG 360 supports multiple viewports.

The JPEG 360’s metadata contain basic schema elements. The schema is expressed in XML as a subset of W3C RDF for serializing and storing the metadata and is structured using the XMP [9]. JPEG 360 defines a content type JUMBF super box with an XML box as a sub box for JPEG 360 metadata. The 16-byte-type UUID in JUMBF description box for the JPEG 360 Metadata XML box is specified as ‘0x785f34b7-5d4b-474c-b89f-1d99e0e3a8dd’, and the default label is ‘JPEG360Metadata’. JPEG 360 also uses the APP11 marker for embedding the JPEG 360 Metadata box in JPEG-1 image files.

3.4. Comparison of JPEG 360 with GPano

We compared the metadata properties of GPano [35] and JPEG 360 [13]. The following findings are presented:

JPEG 360 metadata cover all important properties of GPano metadata except capturing and stitching software, photo dates, source image count, and locked exposure. Although these extra properties are related to the stitching process, they are not related to image rendering.

The JPEG 360 metadata property ‘BoxReference’ can aid a situation wherein the image or part of the image codestream is supplementary.

JPEG 360 metadata cover the properties that GPano metadata do not. JPEG 360 PhiGravity, ThetaGravity, and compass phi can provide more information with regard to the rendering device for realistic rendering. JPEG 360 metadata can support multiple viewports. JPEG 360 metadata provide the ViewportRoll property, through which such a viewport whose sides may not be parallel to the sides of the main image can be handled.

JPEG 360 is built upon the JUMBF super box, which provides compatibility with previous JPEG versions.

Table 6 summarizes the comparison. We can conclude that JPEG 360 metadata include more than GPano metadata for 360-degree images.

Table 6.

GPano metadata and JPEG 360 properties comparison.

3.5. JPEG-1 to JPEG 360 Converter

Here, it was found that all the existing spherical imaging services follow GPano metadata format, and JPEG 360 metadata format may cover the GPano format. The conversion of 360-degree images to standard formats or the insertion of JPEG 360 metadata is needed to allow viewers to benefit from standard metadata for realistic and immersive rendering. We developed a sample application that converts conventional JPEG-1 images to JPEG 360. We hope that this converting tool will help 360-degree-images users and camera and software vendors to provide immersive services and avail full benefits of the standard format in various markets.

In the conversion software, first, we investigate the existing metadata to find whether the input image is spherical or not. Specifically, we look for GPano metadata, capturing camera, and stitching software, through which we can identify that the image is spherical. We call this part of the converter tool the “Input and Investigation Part”. Besides this programmatic detection, we also allow users to embed customized JPEG 360 metadata if the image has no existing metadata information and users still want to convert it. If the image is qualified for conversion by finding projection format information or 360-degree camera name or stitching software in existing metadata, then, in the second part, ‘Generating Metadata’, the metadata values are read from input text file or generated from GPano Metadata values. These metadata values are then formatted in JPEG-360-standardized XML. Next, in the ‘Embedding Part’ of the software, we embed standard JPEG 360 metadata using the JPEG-defined standard JUMBF box. Finally, the new bitstream, including standard JPEG 360 metadata, is written to a new file.

Our proposed tool can also be used to see the existing JPEG 360 metadata in the file; in this case, the APP11 marker from the bitstream is parsed to the metadata extractor for the decoding metadata values from the JUMBF box containing JPEG 360 XML. Thus, our tool allows users to see and update existing metadata.

A detailed description of the tool’s architecture and its implementation, along with a flowchart, is provided in Section 4.1 below.

3.6. PTZ Panorama

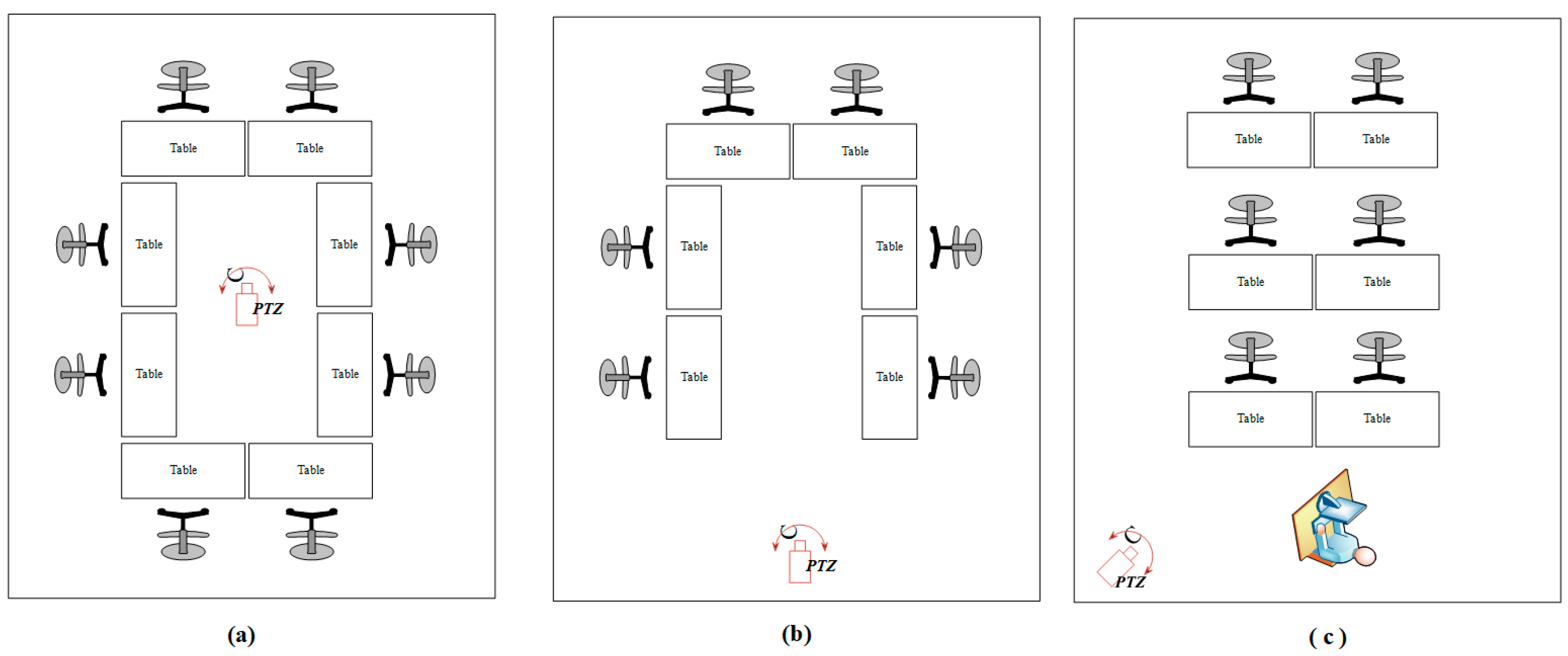

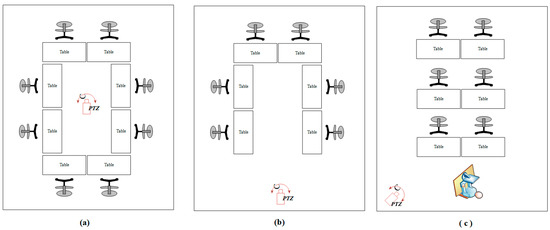

We propose an economical standard panoramic image acquisition system compatible with JPEG 360 from a single PTZ camera. The special-use case for our PTZ panorama is capturing a wide field-of-view image of a conference or meeting. Recently, the usage of virtual meetings has been increasing more during the ongoing pandemic situation. Normally, conferences or meetings are broadcast using a variety of applications. In such a situation, a remote attendee can see only the person or screen shared by the presenter, and he or she cannot see the complete environment of the real conference hall. One possible solution is that if our PTZ panorama with standard metadata is sent to the remote attendee, then he or she can see the complete environment virtually with realistic feelings. The use case is demonstrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

PTZ panorama use-case demonstration. Camera is placed in (a) center, (b) side, and (c) corner.

The environment of a room or hall can be covered using a single PTZ camera placed in the center, side, or corner, resulting in horizontal 360°, 180°, or 90° angles of panorama, respectively. PTZ cameras have a very limited FOV; therefore, the height of panorama depends on the number of images captured vertically. We embed standard JPEG 360 metadata in the panorama using our converter tool. Since our panorama is not a full sphere, the default metadata values are replaced by custom values calculated by ourselves. Viewing our PTZ panorama with any JPEG-360-compatible viewer application provides the exact environment.

4. Implementation and Results

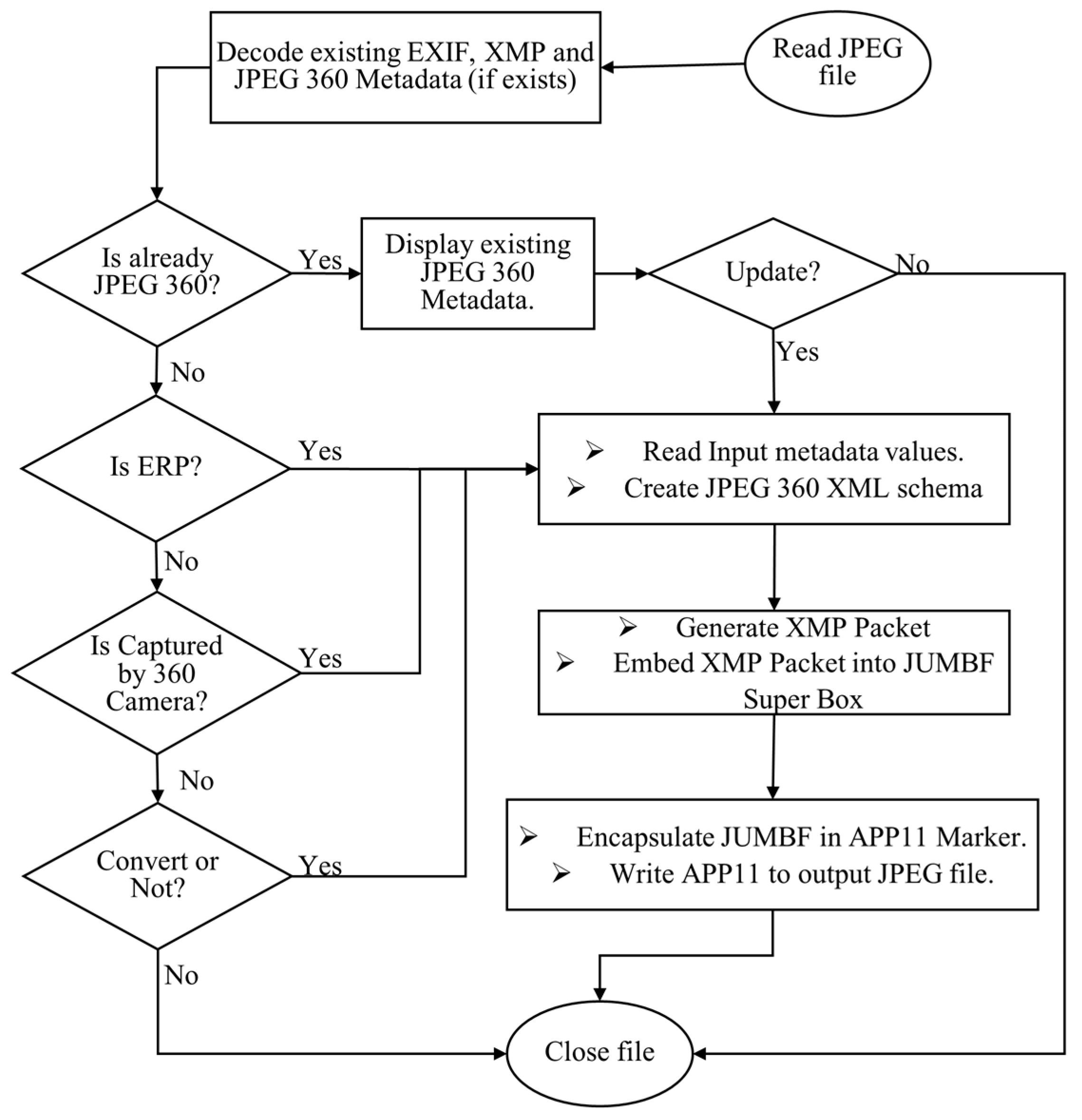

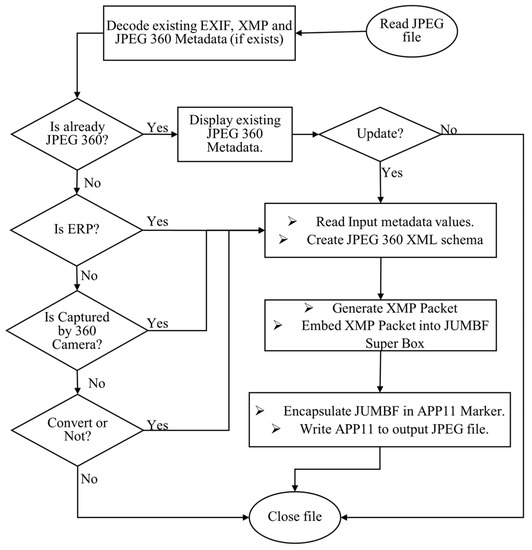

4.1. JPEG 360 Converter

To convert conventional 360-degree images to standard JPEG 360, we implement our algorithm as follows. Figure 6 shows a flowchart of the application. First, in the ‘Input and Investigation Part’, the input JPEG-1 image metadata are parsed to identify the camera model used, projection type, and JPEG 360 metadata information. APP1 and APP11 marker segments are decoded for existing metadata values according to defined standards as discussed in Section 2.3. Based on this information, the decision for conversion is made. In the next step, ‘Generating Metadata’, input values for JPEG 360 metadata properties provided in a text file are read. The user can edit the text file for custom values and can add multi-viewport metadata. XMP packet-encapsulating XML is generated for metadata properties according to the definitions of JPEG 360. In the next step, the XMP packet is packed in the JUMBF super box with the JUMBF description box with the JPEG 360 ID and default label ‘JPEG360Metadata’. Finally, the JUMBF box is encapsulated in the APP11 marker segment and embedded in the file.

Figure 6.

Workflow of the proposed JPEG 360 converter.

The application’s main feature is that it automatically performs JPEG-1 to JPEG 360 conversion if it recognizes the input image as a 360-degree image. Recognizing a 360-degree image depends upon the camera model used and projection type information. If an image is captured with a 360-degree camera, we can find camera information in the EXIF metadata, as discussed in Section 2. A list of cameras capable of capturing 360-degree images is provided to the application. The camera model present in the EXIF metadata of the image is searched in the list of the names of 360-degree-image-capable cameras. This list of cameras is the output of our survey discussed above.

The projection type of the input image is found by parsing the GPano metadata present in the XMP packet. If the input image is captured with a 360-degree camera or the projection type of the input image is equirectangular, then the application automatically converts the input image to JPEG 360. If the camera and projection type information is not present in the input image, the application prompts users to choose a conversion.

The input image is also checked for JPEG 360. If the input image is already a JPEG 360 image, then the existing JPEG 360 metadata values are extracted and displayed to the user. In this case, the user is prompted to update the existing values if he/she desires. The application embeds the JPEG 360 default metadata; however, the user can also embed customized metadata. Users can also embed multiple viewports into the image. After the decision for conversion or update is made, a well-formatted XML schema framed in UTF-8-encoded XMP is generated for the user’s input metadata. The JUMBF super box containing the JUMBF description box is created according to the JPEG 360 standard with the default label ‘JPEG360Metadata’ and XML box as the content-type box. The super box is then encapsulated in the APP11 marker segment.

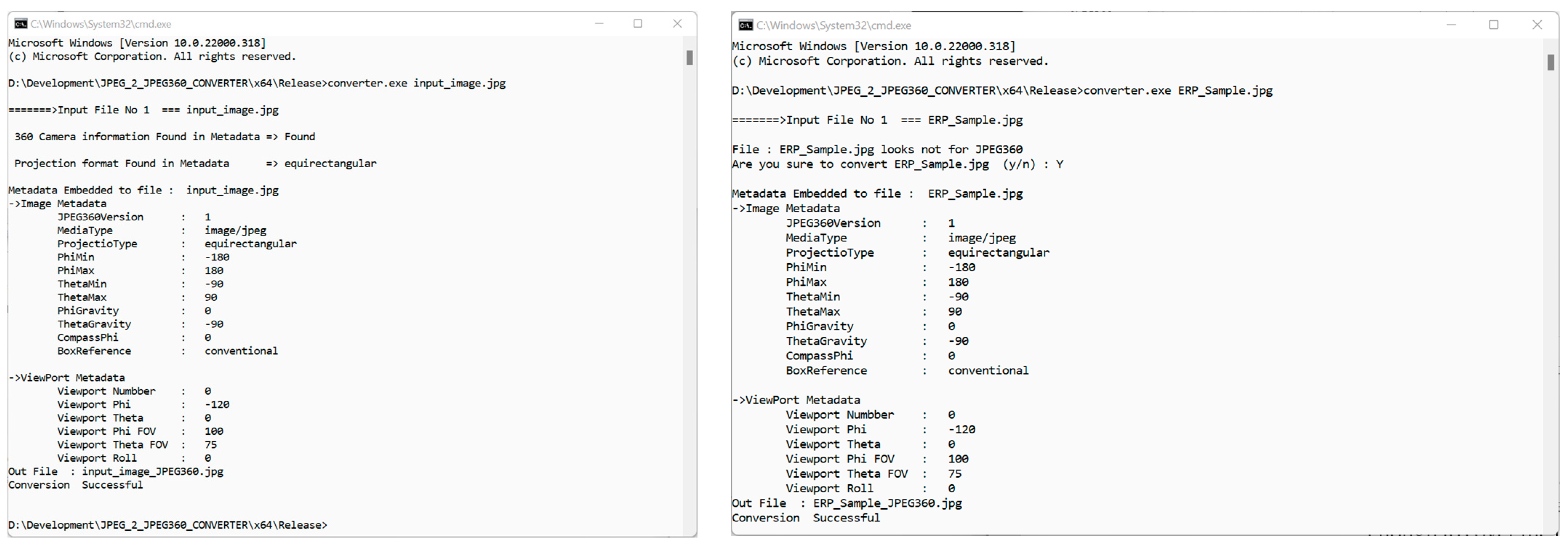

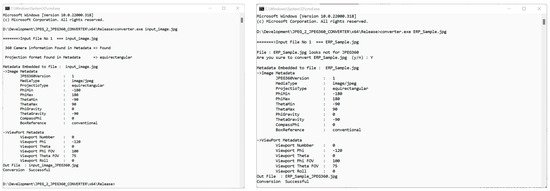

Finally, the application writes the marker into the input file before the commencement of the scan marker. Figure 7 shows example screenshots of the conversion process, where, in the left figure, it is shown that the input image is captured with a 360-degree camera, and an ERP projection is found in the existing metadata. The input image is automatically converted with default metadata. In another example shown in Figure 7, right, the input image is not in JPEG 360 format, nor does it have information regarding the camera or projection format in the file. The user is asked to confirm the conversion in this case.

Figure 7.

Screenshots of the proposed JPEG 360 converter application.

4.2. PTZ Panorama

The camera can be placed in the center, side, or corner of the room to obtain horizontal 360°, 180°, or 90° angles of a panorama. Based on the specification of our PTZ camera used and multiple experiments, we decided that two rows (vertical two images) are enough to cover the important area of the room. The camera that we used has a horizontal FOV of 63.7° and a vertical FOV of about 36°. Thus, we needed 20 images to cover the scene from the center (FOV 360° × 56°), 10 images for the side (FOV 180° × 56°), and 6 images for the corner (FOV 90° × 56°). A single vertical image can also cover the main scene of the hall, so we can also have a panorama with an FOV of 360° × 36°, 180° × 36°, and 90° × 36° from 10, 5, and 3 images for the center, side, and corner, respectively.

We captured images with about 25% overlapping regions. Movement of camera and capturing was controlled from a computer connected through serial communication and using VISCA (Video System Control Architecture) commands specified by the camera manufacturer. The average capturing time for the camera placed in the center was 30.476 s for 20 images and 23.263 s for 10 images, respectively. Similarly, when the camera was placed on the side, 17.919 s and 13.761 s were used for capturing 10 images and 5 images, respectively. Finally, when the camera was placed in the corner, 14.582 s and 11.685 s were used for taking six and three images, respectively.

Images captured using the above setup were then stitched into a panorama. Stitching was completed using the most popular method, i.e., feature-based image stitching. The feature-based stitching consisted of features’ detection, features’ matching, homography estimation, image warping, and seam-binding processes. The OpenCV 4.4.0 library downloaded from the official website [36] with ‘contrib’ modules was used for stitching. Key features of captured images were detected using Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF) [37], Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [38], Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB) [39], and KAZE [40] algorithms. Each algorithm has its pros and cons. SURF and SIFT detect features robustly invariant to image scale, rotation, and illumination [41]. Random sample consensus (RANSAC) [42] was the technique used for feature-matching of adjacent images and estimating homography transform. Based on homography, the adjacent images were warped. To remove seams, we used multi-band blending [43], the most efficient technique for removing seams and preserving quality and a smooth transition.

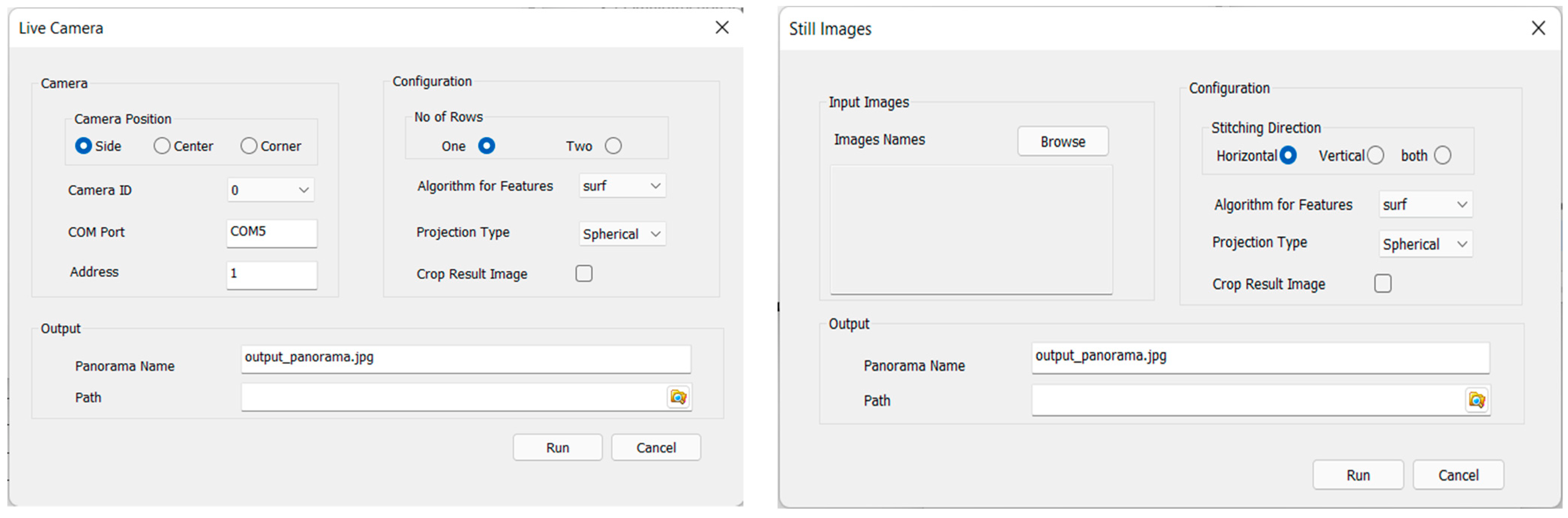

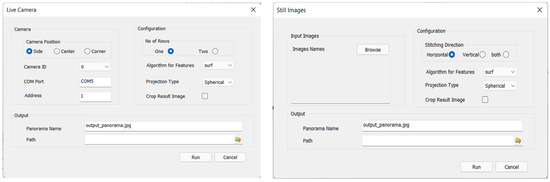

Users can adjust different parameters and use the application easily with our developed Windows graphical user interface software, shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Graphical user interface of PTZ panorama application.

4.3. Results

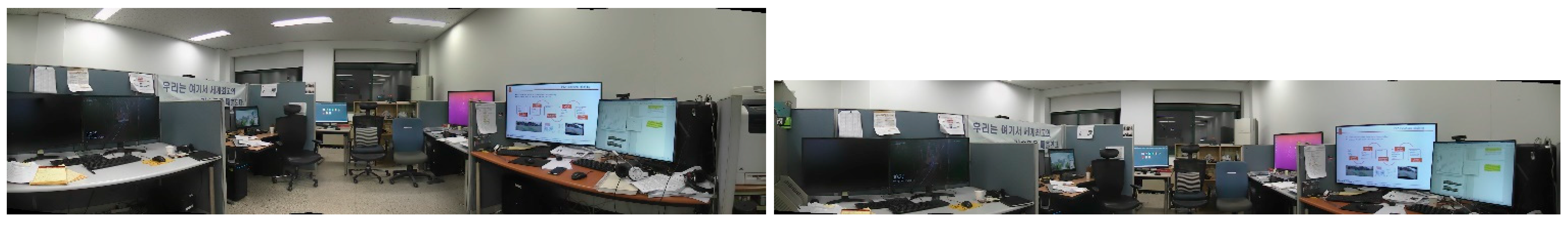

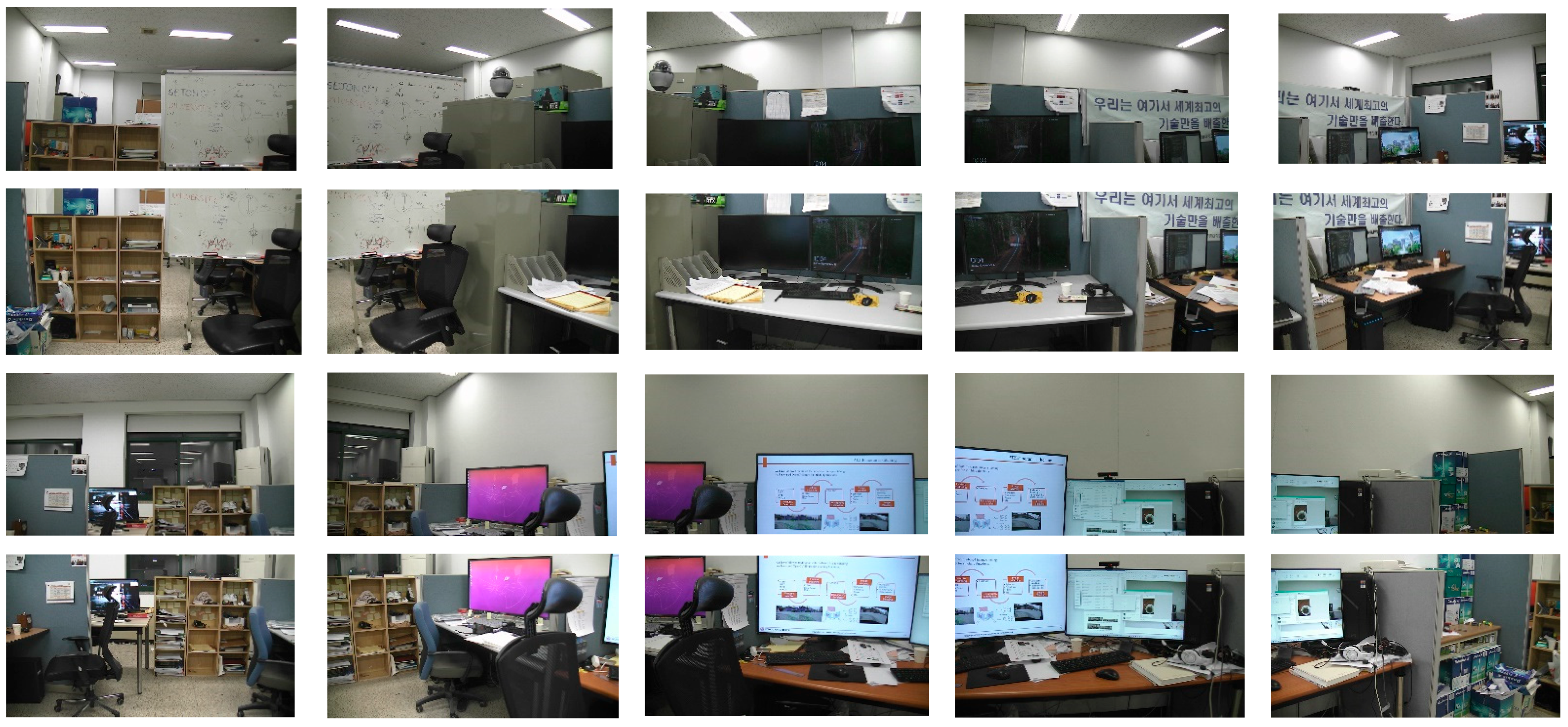

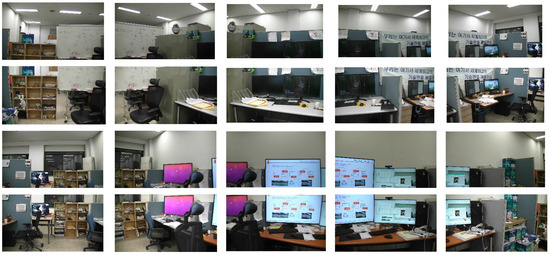

We tested our system in our lab meeting room. Figure 9 shows screenshots of the application that is designed to capture and stitch images. The resultant panoramas stitched from images captured from the center, side, and corner of our lab meeting room are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively, and embedded JPEG 360 metadata values are presented in Table 7 below. Figure 12 and Figure 13 show another scene of panoramas captured from center and side in another meeting room. Upper panoramas in Figure 9 and Figure 12 are stitched from 20 images, and lower panoramas are from 10 images. Similarly, left panoramas in Figure 10 and Figure 13 are stitched from 10 images, and right from 5 images. Finally, panoramas in Figure 11 are stitched from six and three images. Figure 14 provides the 20 images stitched to Figure 12 (upper) for examples.

Figure 9.

Panoramas from center: upper (10,400 × 1600 = 360° × 56°) and lower (10,400 × 1000 = 360° × 36°).

Figure 10.

Panoramas from side: left (5800 × 1600 = 180° × 56°) and right (5800 × 1000 = 180° × 36°).

Figure 11.

Panoramas from corner: left (3800 × 1600 = 90° × 56°) and right (3800 × 1000 = 90° × 36°).

Table 7.

JEPG 360 metadata values for PTZ panorama.

Figure 12.

Panoramas from center: upper (10,400 × 1600 = 360° × 56°) and lower (10,400 × 1000 = 360° × 36°).

Figure 13.

Panoramas from side: left (5800 × 1600 = 180° × 56°) and right (5800 × 1000 = 180° × 36°).

Figure 14.

Twenty unstitched images of panorama from center of room (each image is originally captured in 1920 × 1080 resolution).

JPEG 360 metadata values provided in Table 7 are embedded in the respective panorama using our converter application. Output panoramas are compatible with the JPEG 360 standard and can be rendered with the JPEG 360 standard supported image viewer to enjoy a realistic and immersive environment.

5. Discussion

Our converter tool is a Windows console application developed in C++, as shown in Figure 7. We believe that this is a novel work that implements the emerging international standard. Our work enables the transformation of a large amount of legacy 360-degree images into the standardized format, which provides a market to use the images in the same format, which was a goal of developing the JPEG 360 standard. This application can also be used to view JPEG 360 metadata in a JPEG-1 image. Users can extract metadata values and use them according to their needs. It can be a basic unit in developing viewer/renderer software for standard JPEG 360 images. We also used it in our PTZ panorama to convert the obtained panorama to JPEG 360 format. Another advantage of this command-line application is that it can be utilized using batch command to convert many files at a time. The subjective and objective quality of the converted image remains the same as the image pixels bitstream is not involved in the conversion process. This is a significant advantage of the converter: visual quality is fully preserved. The file size is increased by approximately 8 kB after adding JPEG 360 metadata.

The limitation of the converter application is that if the user wants to forcefully embed JPEG 360 metadata to a 2D image, the image will still be converted to JPEG 360. Another limitation is that the user should carefully provide the metadata values because the converter is not intelligent enough to check the values to understand whether the values satisfy the constraint equations.

The PTZ panorama solution is cheap compared to standard 360-degree cameras because the PTZ cameras are very low in price. The standard JPEG 360 metadata values in our panorama are necessary for realistic rendering of the panorama, which helps the viewer see the realistic environment virtually. In our Windows application, we provided four options for stitching algorithms. A user can choose either SURF, SIFT, ORB, or AKAZE. We compared the stitching time of all these algorithms. Table 8 shows the average stitching time. We can observe that ORB consumes less time, and SURF and SIFT consume more time than others. SURF and SIFT take longer because of their robustness. Based on experiments on different input images, we found that SURF is robust in finding features, so it stitches more successfully than the others. We provided two projection formats for the resultant panorama: spherical and cylindrical. Although our resultant panorama is not a full sphere, it is part of a sphere, and the situation is similar for the cylindrical format.

Table 8.

Stitching time of different feature-finding algorithms.

From several experiments, it is observed that when the number of input images is more than 10, the stitching process becomes complicated, and visible seams appear in the resultant panorama. Furthermore, the probability of stitching failure appears to increase; other than this, the resultant panorama has no subjectively visible seams. SIFT sometimes fails to find enough features sufficient for homography estimation, and thus, stitching fails.

6. Conclusions

We surveyed the format of 360-degree-related metadata followed by different camera makers. We found that the GPano metadata format is followed by most cameras. JPEG WG defined JPEG 360, a new standard format for 360-degree metadata. As a result of comparing GPano metadata properties and JPEG 360 metadata properties, we found that the JPEG 360 metadata format covers more than the GPano metadata format. Therefore, it is necessary to convert a huge number of legacy 360-degree images in the market to a standard format, which requires a converter tool. We presented our own developed tool to convert 360-degree images from the conventional JPEG-1 format to the JPEG 360 standard format. This helps users convert their images to a standardized format efficiently to achieve more benefits of metadata in designing different VR/AR applications. Our implementation can be used to extract and view JPEG 360 standard metadata values. Similarly, our tool can be used as a basic unit for developing image-rendering software for omnidirectional content. As a practical-use case of our converter, we also proposed and implemented a system of a JPEG 360-compatible panorama from a single PTZ camera. This panorama will be suitable for broadcasting and recording a conference or meeting. A participant attending or watching the conference/meeting remotely can see and observe the environment more effectively through the wide-FOV, standard JPEG 360 panorama. The proposed PTZ panorama solution is also cost-effective compared with state-of-the-art omnidirectional solutions and cameras.

In the future, the JPEG 360 converter tool can be made intelligent to overcome the limitations presented in Section 5 above. This will enable the tool to recognize the 360-degree image programmatically and assess the input metadata values according to the constraint definition. Similarly, in research regarding PTZ panoramas, the stitching time can be improved to apply a non-feature-based stitching approach as the pan, tilt angles, and camera parameters can be obtained directly from the camera for homography estimation. Thus, features-finding, matching, and homography estimation can be skipped to optimize and speed up stitching time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.U. and O.-J.K.; data curation, F.U.; formal analysis, S.C.; funding acquisition, O.-J.K.; project administration, S.C.; resources, S.C.; software, F.U.; supervision, O.-J.K.; writing—original draft, F.U.; writing—review and editing, O.-J.K. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Institute for Information and Communications Technology Promotion (IITP) grant number 2020-0-00347 And The APC was funded by Korea Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Timmerer, C.; Graf, M.; Mueller, C. Adaptive Streaming of vr/360-Degree Immersive Media Services with High Qoe. In Proceedings of the 2017 NAB Broadcast Engineering and IT Conference (BEITC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–27 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Jenny, B.; Dwyer, T.; Marriott, K.; Chen, H.; Cordeil, M. Maps and Globes in Virtual Reality. In Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 37, pp. 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Eiris, R.; Gheisari, M.; Esmaeili, B. PARS: Using augmented 360-degree panoramas of reality for construction safety training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adachi, R.; Cramer, E.M.; Song, H. Using virtual reality for tourism marketing: A mediating role of self-presence. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, J. The Potential of 360-Degree Videos for Teaching, Learning and Research. In Proceedings of the INTED2018 Conference, Valencia, Spain, 5–7 March 2018; pp. 1448–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Eiris, R.; Gheisari, M.; Esmaeili, B. Desktop-based safety training using 360-degree panorama and static virtual reality techniques: A comparative experimental study. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, G.; Léger, A.; Niss, B.; Sebestyén, I. JPEG at 25: Still going strong. IEEE MultiMedia 2017, 24, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, W.B.; Mitchell, J.L. JPEG: Still Image Data Compression Standard; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, J.S.; Graff, C.A.; Ohman, M.D. Improving plankton image classification using context metadata. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2019, 17, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riggs, C.; Douglas, T.; Gagneja, K. Image Mapping through Metadata. In Proceedings of the 2018 Third International Conference on Security of Smart Cities, Industrial Control System and Communications (SSIC), Shanghai, China, 18–19 October 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Temmermans, F.; Kuzma, A.; Choi, S.; Park, J.-H.; Schelkens, P. Adopting the JPEG systems layer to create interoperable imaging ecosystems (Conference Presentation). In Proceedings of the Optics, Photonics and Digital Technologies for Imaging Applications VI, online in Europe, 17 April 2020; p. 113530T. [Google Scholar]

- Information Technologies—JPEG Systems—Part 5: JPEG Universal Metadata Box Format (JUMBF), ISO/IEC 19566-5. 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/73604.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Information Technologies—JPEG Systems—Part 6: JPEG 360, ISO/IEC 19566-6. 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75846.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Richter, T.; Artusi, A.; Ebrahimi, T. JPEG XT: A new family of JPEG backward-compatible standards. IEEE Multimed. 2016, 23, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.T.; Hagsten, E. When international academic conferences go virtual. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M. Scientists discover upsides of virtual meetings. Science 2020, 368, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinger, L.; Gazendam, A.; Ekhtiari, S.; Nucci, N.; Payne, A.; Johal, H.; Khanduja, V.; Bhandari, M. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: A review of best practices. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Han, C.; Tao, X.; Geng, B.; Du, Y.; Lu, J. Panoramic Image Generation: From 2-D Sketch to Spherical Image. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2020, 14, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertel, T.; Yuan, M.; Lindroos, R.; Richardt, C. OmniPhotos: Casual 360° VR Photography. ACM Trans. Graph. 2020, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, N.; Kasai, S.; Hayashi, M.; Aoki, Y. 360-Degree Image Completion by Two-Stage Conditional Gans. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 4704–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, H.; Zia, O.; Kim, J.H.; Han, K.; Lee, J.W. Automatic 360° Mono-Stereo Panorama Generation Using a Cost-Effective Multi-Camera System. Sensors 2020, 20, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguel-Baeta, B.; Bermudez-Cameo, J.; Guerrero, J.J. OmniSCV: An Omnidirectional Synthetic Image Generator for Computer Vision. Sensors 2020, 20, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duanmu, F.; Mao, Y.; Liu, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Wang, Y. A subjective study of viewer navigation behaviors when watching 360-degree videos on computers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Liu, L.; Yi, H.; Wang, W.; Suitoh, H.; Odamaki, M. Toward Real-World Panoramic Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Virtual, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 628–629. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhai, G.; Min, X.; Zhou, J. The prediction of saliency map for head and eye movements in 360 degree images. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2019, 22, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhuran, J.; Kulupana, G.; Galkandage, C.; Fernando, A. Multiple Quantization Parameter Optimization in Versatile Video Coding for 360° Videos. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2020, 66, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Lim, H.-T.; Ro, Y.M. Deep virtual reality image quality assessment with human perception guider for omnidirectional image. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 30, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orduna, M.; Díaz, C.; Muñoz, L.; Pérez, P.; Benito, I.; García, N. Video multimethod assessment fusion (vmaf) on 360vr contents. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2019, 66, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Information Technology—Digital Compression and Coding of Continuous-Tone Still Images: Requirements and Guidelines, ISO/IEC 10918-1. 1994. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/18902.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Information Technology—Digital Compression and Coding of Continuous-Tone Still Images: JPEG File Interchange Format (JFIF)—Part 5, ISO/IEC 10918-5. 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/54989.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Exchangeable Image File Format for Digital Still Cameras: Exif Version 2.2 JEITA CP-3451. 2002. Available online: https://www.exif.org/Exif2-2.PDF (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- TIFF 6.0 Specification. 1992. Available online: https://www.itu.int/itudoc/itu-t/com16/tiff-fx/docs/tiff6.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Graphic Technology—Extensible Metadata Platform (XMP)—Part 1: Data Model, Serialization and Core Properties. ISO 16684-1/2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75163.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Information Technology—Scalable Compression and Coding of Continuous-Tone Still Images—Part 3: Box File Format, ISO/IEC 18477-3. 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66071.html (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Photo Sphere XMP Metadata. Google. Available online: https://developers.google.com/streetview/spherical-metadata (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- OpenCV. Available online: https://sourceforge.net/projects/opencvlibrary/files/4.4.0/opencv-4.4.0-vc14_vc15.exe/download (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Surf: Speeded up robust features. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R.Y. BRISK: Binary robust invariant scalable keypoints. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2548–2555. [Google Scholar]

- Alcantarilla, P.F.; Solutions, T. Fast explicit diffusion for accelerated features in nonlinear scale spaces. IEEE Trans. Patt. Anal. Mach. Intell 2011, 34, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, Y.-J.; Kang, H.-D. Evaluation of feature based image stitching algorithm using OpenCV. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Conference on Human System Interactions (HSI), Ulsan, Korea, 17–19 July 2017; pp. 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- Derpanis, K.G. Overview of the RANSAC Algorithm. Image Rochester NY 2010, 4, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, P.J.; Adelson, E.H. A multiresolution spline with application to image mosaics. ACM Trans. Graph. TOG 1983, 2, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).