Cellular Antioxidant Effects and Bioavailability of Food Supplements Rich in Hydroxytyrosol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Standards and Reagents

2.2. Sample Material

2.3. Analysis of Polyphenols

2.4. Cell Cultures

2.5. Cellular Viability Assay

2.6. Cellular Antixidant Activity (CAA)

2.7. Cellular Extract Preparation

2.8. Catalase Activity Assay

2.9. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

2.10. Endogenous F2-Isoprostanes Measurement

2.11. Endogenous AGEs Measurement

2.12. Bioavailability

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Food Supplements

3.2. Bioassays

3.2.1. CAA

3.2.2. SOD and Catalase Activities

3.2.3. Cellular Peroxidation

3.2.4. Antiglycation Activity

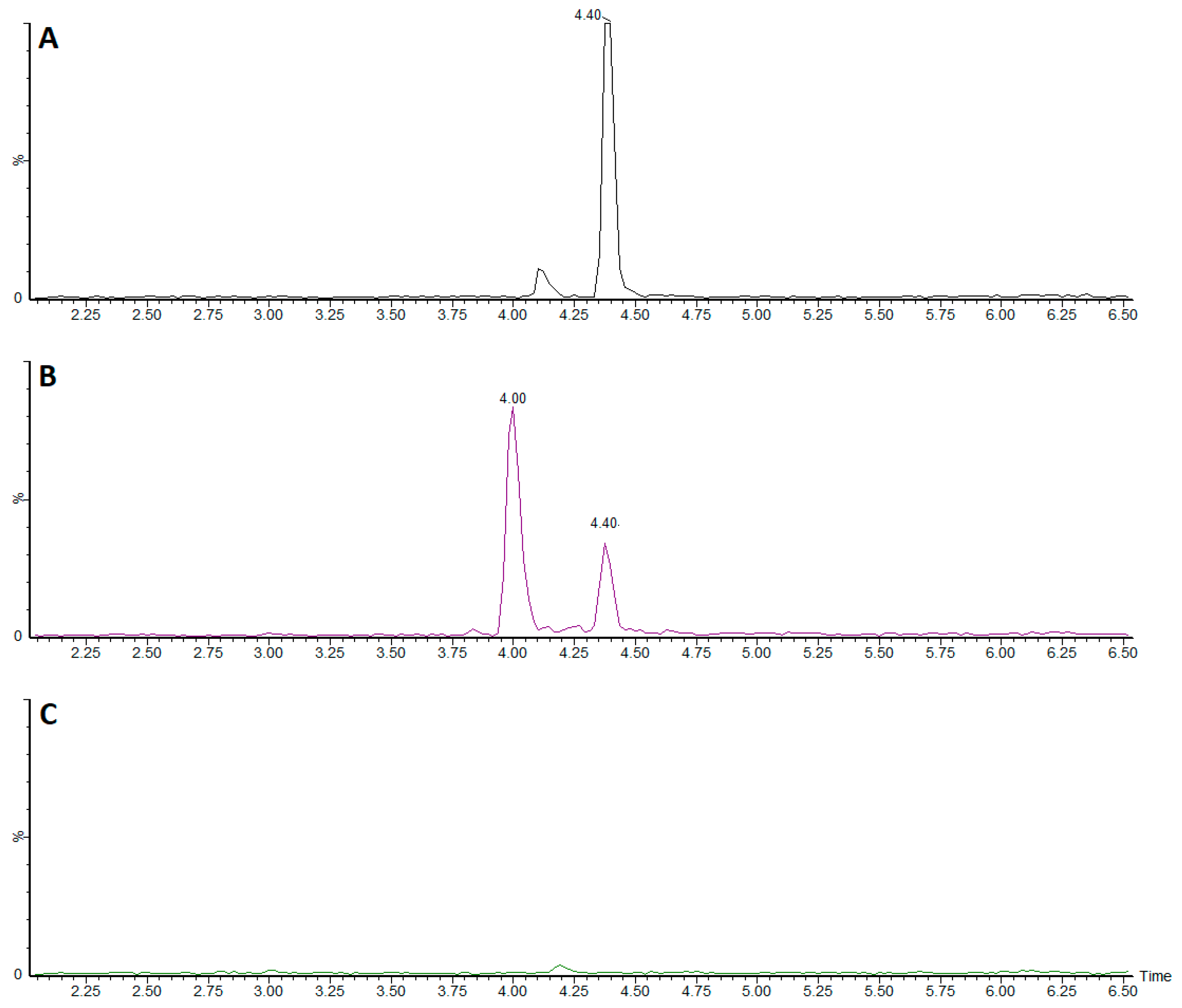

3.3. Bioavailability

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothwell, J.A.; Perez-Jimenez, J.; Neveu, V.; Medina-Remon, A.; M’Hiri, N.; Garcia-Lobato, P.; Manach, C.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Wishart, D.S.; et al. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: A major update of the phenol-explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database 2013, 2013, bat070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obied, H.K.; Allen, M.S.; Bedgood, D.R.; Prenzler, P.D.; Robards, K.; Stockmann, R. Bioactivity and analysis of biophenols recovered from olive mill waste. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Galli, C. biological properties of olive oil phytochemicals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covas, M.I.; Nyyssönen, K.; Poulsen, H.E.; Kaikkonen, J.; Zunft, H.J.; Kiesewetter, H.; Gaddi, A.; de la Torre, R.; Mursu, J.; Bäumler, H.; et al. The effect of polyphenols in olive oil on heart disease risk factors: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covas, M.I.; de la Torre, R.; Fitó, M. Virgin olive oil: A key food for cardiovascular risk protection. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, S19–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to polyphenols in olive and protection of LDL particles from oxidative damage (ID 1333, 1638, 1639, 1696, 2865), maintenance of normal blood HDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1639), maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 3781), “anti-inflammatory properties” (ID 1882), “contributes to the upper respiratory tract health” (ID 3468), “can help to maintain a normal function of gastrointestinal tract” (3779), and “contributes to body defences against external agents” (ID 3467) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2011, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Manna, C.; Migliardi, V.; Mazzoni, O.; Morrica, P.; Capasso, G.; Pontoni, G.; Galletti, P.; Zappia, V. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of hydroxytyrosol, a natural antioxidant from olive oil. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001, 29, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Khymenets, O.; Crespo, M.C.; Dangles, O.; Rakotomanomana, N.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Visioli, F. Human hydroxytyrosol’s absorption and excretion from a nutraceutical. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 23, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Galli, C.; Grande, S.; Colonnelli, K.; Patelli, C.; Galli, G.; Caruso, D. Hydroxytyrosol excretion differs between rats and humans and depends on the vehicle of administration. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2612–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelm, M.A.; Johnson, J.C.; Robbins, R.J.; Hammerstone, J.F.; Schmitz, H.H. High-performance liquid chromatography separation and purification of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) procyanidins according to degree of polymerization using a diol stationary phase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Liu, R.H. Cellular antioxidant activity (caa) assay for assessing antioxidants, foods, and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8896–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, C.; Graziano, S.; Zimmermann, B.F. Study of stevia rebaudiana bertoni antioxidant activities and cellular properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.E.; Bomser, J.A.; Min, D.B. Bioactivity of resveratrol. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2006, 5, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Fu, Y.C.; Wang, W. Cellular and molecular effects of resveratrol in health and disease. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoliga, J.M.; Baur, J.A.; Hausenblas, H.A. Resveratrol and health—A comprehensive review of human clinical trials. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Garza, S.; Laveriano-Santos, E.; Marhuenda-Muñoz, M.; Storniolo, C.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R. Health effects of resveratrol:Results from human intervention trials. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Mukhtar, H. Tea polyphenols in promotion of human health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Joseph, J.A. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedouhene, S.; Hurtado-Nedelec, M.; Sennani, N.; Marie, J.; El-Benna, J.; Moulti-Mati, F. Polyphenols extracted from olive mill wastewater exert a strong antioxidant effectin human neutrophils. Int. J. Waste Resour. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, T.; Bassani, B.; Gallo, C.; Maramotti, S.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A.; Bruno, A. Effect of a purified extract of olive mill waste water on endothelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration and capillary-like structure in vitro and in vivo. J. Bioanal. Biomed. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Strategies of antioxidant defense. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 215, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fki, I.; Sashnoun, Z.; Sayadi, S. Hypocholesterolemic effects of phenolic extracts and purified hydroxytyrosol recovered fromolive mill wastewater in rats fed a cholesterol-rich diet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, J.D.; Hill, K.E.; Burk, R.F.; Nammour, T.M.; Badr, K.F.; Roberts, L.J. A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 9383–9387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, G.L.; Musiek, E.S.; Morrow, J.D. F2-Isoprostanes as markers of oxidative stress in vivo: An overview. Biomarkers 2005, 10, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.L.; Yin, H.; Hardy, K.D.; Davies, S.S.; Roberts, L.J. Isoprostane generation and function. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5973–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Guidance for the scientific requirements for health claims related to antioxidants, oxidative damage and cardiovascular health. EFSA J. 2018, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Caruso, D.; Galli, C.; Viappiani, S.; Galli, G.; Sala, A. Olive oils rich in natural catecholic phenols decrease isoprostane excretion in humans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 278, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.; Beilin, L. Advanced glycation end-products: A review. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, S.; Bejarano, E.; Taylor, A. Mechanistic targeting of advanced glycation end-products in age-related diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, R.; Mori, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kaji, Y.; Yonei, Y. Significance of advanced glycation end products in aging-related disease. Anti-Aging Med. 2010, 7, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungratanawanich, W.; Qu, Y.; Wang, X.; Essa, M.M.; Song, B.J. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and other adducts in aging-related diseases and alcohol-mediated tissue injury. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbar, S.; Figarola, J.L. Novel inhibitors of advanced glycation endproducts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 419, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Mel’nikova, T.I.; Porozov, Y.B.; Terentiev, A.A. Oxidative stress and advanced lipoxidation and glycation end products (ALEs and AGEs) in aging and age-related diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crascì, L.; Lauro, M.L.; Puglisi, G.; Panico, A. Natural antioxidant polyphenols on inflammation management: Anti-glycation activity vs metalloproteinases inhibition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.J.; Hsia, S.M.; Lee, W.H.; Wu, C.H. Polyphenols with antiglycation activity and mechanisms of action: A review of recent findings. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Morales, F.J.; Ramos, S. Olive leaf extract concentrated in hydroxytyrosol attenuates protein carbonylation and the formation of advanced glycation end products in a hepatic cell line (HepG2). Food Funct. 2017, 8, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Galli, C.; Bornet, F.; Mattei, A.; Patelli, R.; Galli, G.; Caruso, D. Olive oil phenolics are dose-dependently absorbed in humans. FEBS Lett. 2000, 468, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró-Casas, E.; Covas, M.I.; Fitò, M.; Farré-Albadalejo, M.; de la Torre, R. Tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol are absorbed from moderate and sustained doses of virgin olive oil in humans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Valls, M.R.; Romero, M.P.; Macià, A.; Fernàndez, S.; Giralt, M.; Solà, R.; Motilva, M.J. Bioavailability of phenols from a phenol-enriched olive oil. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bock, M.; Thorstensen, E.B.; Derraik, J.G.B.; Henderson, H.V.; Hofman, P.L.; Cutfield, W.S. Human absorption and metabolism of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol ingested as olive (Olea europaea L.) leaf extract. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, A.; Minihane, A.M. The role of metabolism (and the microbiome) in defining the clinical efficacy of dietary flavonoids. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 105, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, B. Hydroxyl radical and its scavengers in health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2011, 2011, 809696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2018, 13, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H. Expression of the extracellular superoxide dismutase protein in diabetes. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2013, 40, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in oxidative stress-and age-associated degenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9613090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuschi, P.; Corradi, M.; Ciabattoni, G.; Nightingale, J.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Barnes, P.J. Increased 8-isoprostane, a marker of oxidative stress, in exhaled condensate of asthma patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 160, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P-1 | P-2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Content (mg/L) | |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 1196 ± 35 | 1399 ± 45 |

| Oleuropein a | 18.1 | 11.9 |

| Tyrosol | 27.0 ± 0.4 | 43.9 ± 3.5 |

| Trans-resveratrol | -- | 3.34 ± 0.04 |

| Total phenolic content a* | 11,220 | 11,371 |

| Proanthocyanidin monomers | -- | 165 ± 4 |

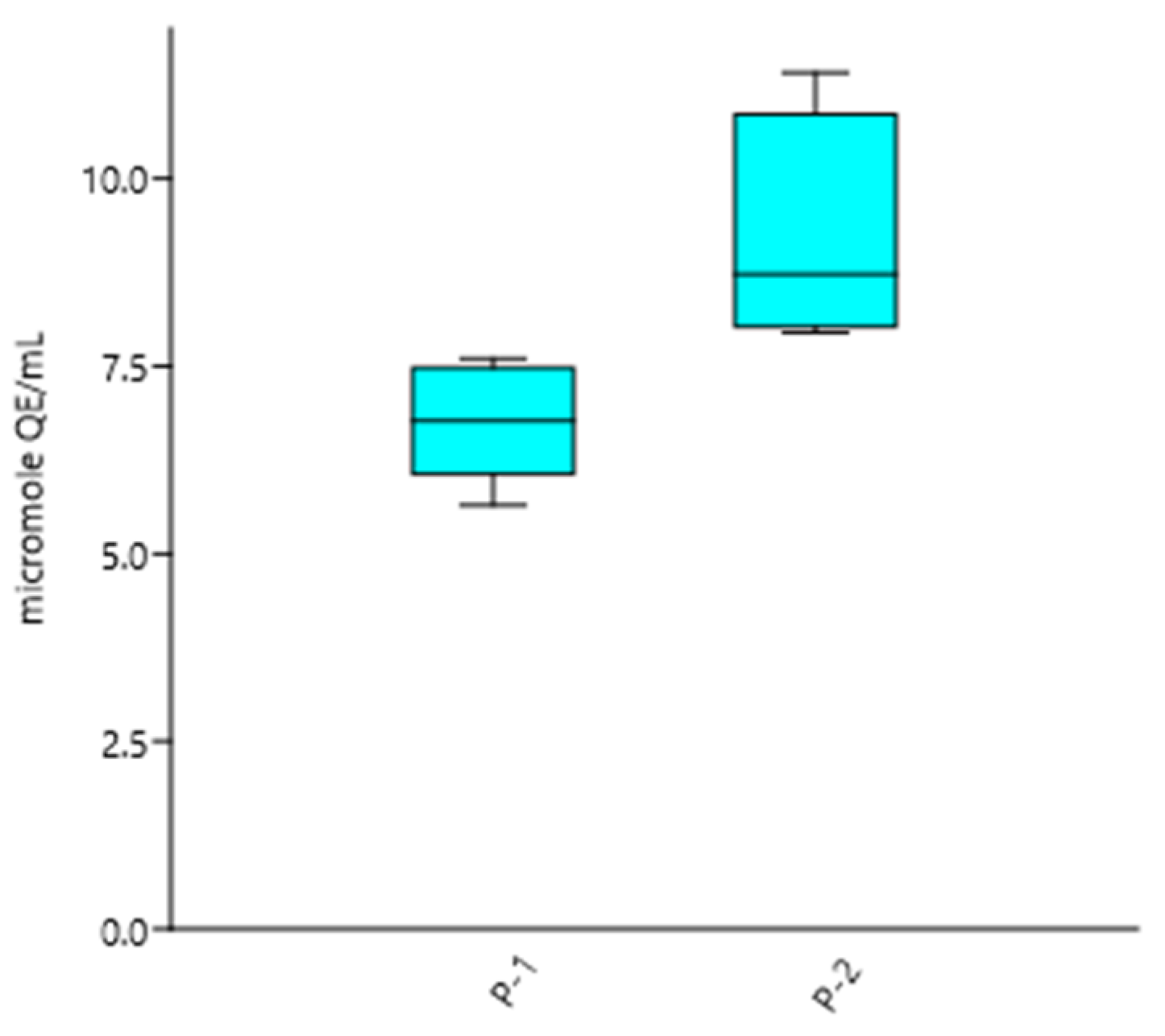

| Treatment | Dilution Range Ŧ (v/v) | µmol QE/mL ** |

|---|---|---|

| Sample P-1 | 1:250- 1:750 | 6.77 ± 0.77 * |

| Sample P-2 | 1:250- 1:750 | 9.20 ± 1.57 * |

| Treatment | U SOD/mg Protein | U Catalase/mg Protein |

|---|---|---|

| UTC | 6.87 ± 0.44 * | 5.52 ± 0.04 |

| P-1 | 7.93 ± 0.13 * | 5.51 ± 0.03 |

| P-2 | 9.23 ± 0.24 * | 7.39 ± 0.18 |

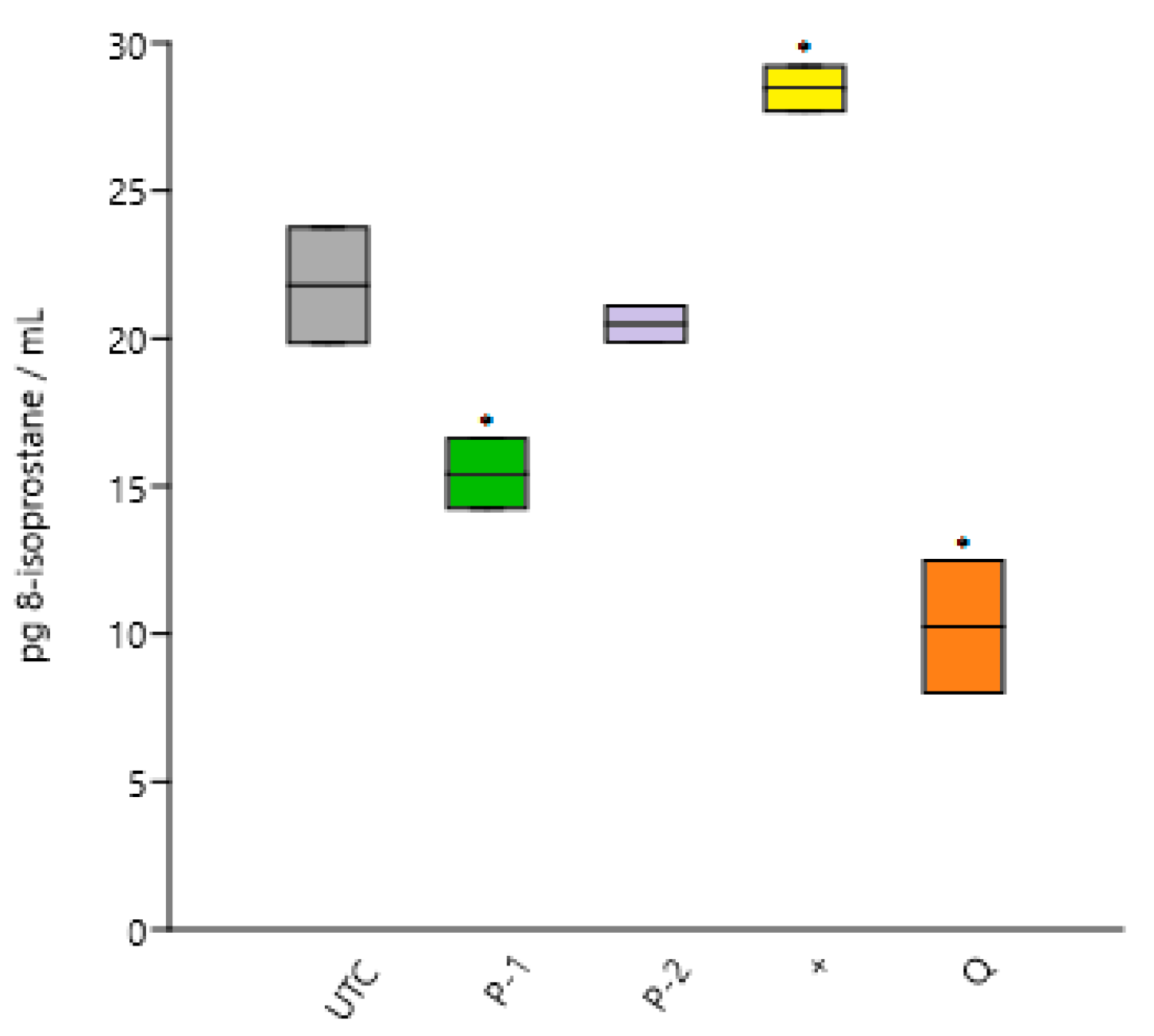

| Treatment | 8-epi PGF2α (pg/mL) | Relative Isoprostanes (%) |

|---|---|---|

| UTC | 21.80 ± 1.95 | 100.0 |

| AAPH | 28.45 ± 0.76 * | 130.5 * |

| P-1 | 15.42 ± 1.18 * | 70.7 * |

| P-2 | 20.49 ± 0.60 | 93.9 |

| Q | 10.24 ± 2.23 * | 47.0 * |

| Treatment | μg AGEs/mg Protein | Relative AGEs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| UTC | 1.02 ± 0.006 | 100 |

| + | 2.64 ± 0.042 | 258 |

| P-1 | 0.52 ± 0.008 | 50.9 |

| P-2 | 0.47 ± 0.007 | 46.0 |

| In Vitro Test | Cellular Effect | Magnitude and Direction of the Effect In Vitro | Associated In Vivo Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-1 | P-2 | |||

| CAA | Removal of hydroxyl radicals | ↑ | ↑↑ | Hydroxyl radical damage protection. Consequences of hydroxyl radicals are related to artherosclerosis, cancer and neurological disorders [44]. |

| AGEs | Glycation ability | ↓ | ↓ | An increase in AGEs is associated with cellular aging processes, oxidative stress, inflammatory reactions, and chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease [32,33], and chronic kidney disease [45]. |

| SOD activity | Superoxide removal | ↑ | ↑↑ | Oxidative damage protection. SOD deficiency is associated with diabetes [46]. |

| Catalase activity | Hydrogen peroxide removal | ~ | ↑↑ | Oxidative damage protection. Catalase deficiency is associated with diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and acatalasemia [47]. |

| 8-isoprostane | Lipid peroxidation | ↓ | ~ | Reliable biomarker of lipoxidation (an increase on F2-isoprostanes is correlated with oxidative stress) [28,48]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bender, C.; Straßmann, S.; Heidrich, P. Cellular Antioxidant Effects and Bioavailability of Food Supplements Rich in Hydroxytyrosol. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114763

Bender C, Straßmann S, Heidrich P. Cellular Antioxidant Effects and Bioavailability of Food Supplements Rich in Hydroxytyrosol. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):4763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114763

Chicago/Turabian StyleBender, Cecilia, Sarah Straßmann, and Pola Heidrich. 2021. "Cellular Antioxidant Effects and Bioavailability of Food Supplements Rich in Hydroxytyrosol" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 4763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114763

APA StyleBender, C., Straßmann, S., & Heidrich, P. (2021). Cellular Antioxidant Effects and Bioavailability of Food Supplements Rich in Hydroxytyrosol. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 4763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114763