1. Introduction

The study of organizational models has long relied on paradigms such as Fordism and post-Fordism to explain how capitalism structures production, labor, and governance. Fordism emphasized standardized mass production and stable employment regimes, whereas post-Fordism highlighted flexibility, decentralization, and globally distributed production networks. However, the acceleration of digitalization, platformization, and algorithmic governance (

Watkins & Stark, 2018;

Stark & Pais, 2020;

Stark & Vanden Broeck, 2024) raises questions about whether these frameworks remain sufficient for interpreting the present. The emergence of platform-based business models, gig work, and data-driven labor control suggests a profound reconfiguration of how value is produced, mediated, and distributed. These transformations indicate the need to revisit the conceptual foundations of organizational analysis, linking the historical trajectory from Fordism to post-Fordism with the novel challenges posed by digital capitalism.

At the center of this transformation lie three interconnected concepts: the platform economy, the gig economy, and the sharing economy. Initially framed as engines of efficiency, collaboration, and empowerment, these forms of economic organization are increasingly scrutinized for producing systemic precarity and embedding new modes of algorithmic control. Platforms do not merely mediate transactions; they function as socio-technical infrastructures that reorganize labor relations, redefine managerial authority, and reshape global markets. This duality—innovation coupled with exploitation—underscores the need for interdisciplinary inquiry that combines critical perspectives from labor sociology with managerial approaches to business models and innovation. In this sense, the platform economy operates both as an empirical object and as a theoretical frontier in contemporary organizational scholarship.

This paper contributes to this debate by offering a bibliometric mapping of the platform economy as an evolving research field, tracing its intellectual genealogy, conceptual clusters, and collaborative networks. The analysis shows that the field has matured into a coherent yet contested domain, with citation cascades linking pioneering works to contemporary debates, disciplinary bridges connecting sociology and management studies, and persistent global asymmetries in knowledge production. By situating these findings within the longer historical arc beyond post-Fordism, the study highlights both continuities—such as flexibility and decentralization—and the structural ruptures introduced by digital platforms, algorithmic management, and Industry 5.0 discourses. The aim is not only to synthesize existing knowledge but also to identify critical tensions that will shape future research on governance, equity, and sustainability in the digital age.

Accordingly, the present study pursues four complementary objectives. First, it maps the intellectual genealogy of platform economy research, tracing how debates on Fordism and post-Fordism have influenced subsequent developments. Second, it identifies the authors, journals, and national contexts that shape scholarly influence and international collaboration. Third, it reconstructs the field’s conceptual architecture by examining its dominant themes and cluster configurations through co-occurrence and citation networks. Finally, it interprets these empirical patterns within broader discussions of the transition “beyond post-Fordism,” highlighting how algorithmic governance and digital infrastructures are redefining contemporary organizational models. Taken together, these aims provide a coherent analytical framework that guides the empirical analysis and clarifies the study’s contribution.

2. Theoretical Framework

The historical evolution of organizational models has traditionally been examined through the transition from Fordism to post-Fordism, offering a foundational lens for understanding how capitalism structures production, labor, and governance. Under the Fordist regime, mass production, standardized processes, and vertically integrated organizational structures were supported by collective bargaining, welfare-state protections, and rising real wages that linked mass consumption to mass production (

Aglietta, 1979;

Boyer, 1990;

Lipietz, 1987). This institutional configuration stabilized growth by aligning industrial relations, macroeconomic policies, and consumer demand. However, it rested on fragile complementarities that gradually eroded due to global competition, technological saturation, and recurrent economic crises, exposing structural rigidities within the model (

Harvey, 1989;

Scott & Storper, 1986). As the Fordist compromise broke down, it created space for new modes of production, organizational reconfiguration, and labor governance.

Post-Fordism emerged as a response to these contradictions and became associated with flexible specialization, decentralized production, and globalized value chains capable of rapid adaptation to volatile markets (

Piore & Sabel, 1984;

Amin, 1994). Regulation theory framed this shift as the rise in “flexible accumulation”, where firms increasingly relied on outsourcing, subcontracting, modular production, and project-based teams (

Boyer, 1990;

Jessop, 1992).

Castells’ (

1996) conceptualization of the “network society” further emphasized the centrality of information flows, global networks, and technological infrastructures in reconfiguring organizations and labor markets. These transformations were not only economic but also cultural: the emergence of post-Fordist management philosophies foregrounded innovation, individual initiative, and continuous improvement, generating a normative environment in which adaptability and self-management became celebrated virtues (

Boltanski & Chiapello, 2005;

Fraser, 2013).

The post-Fordist regime produced a profoundly ambivalent legacy. Flexible arrangements allowed some workers to benefit from enhanced temporal autonomy, improved work–life alignment, and opportunities to integrate employment with caregiving or education (

Shacklock et al., 2009;

Green & Leeves, 2013). Yet these gains were unevenly distributed and frequently overshadowed by systemic precarity, fragmented career trajectories, and the diffusion of risk onto workers themselves (

Standing, 2011;

Pyöriä & Ojala, 2016;

Lamberg, 2022). Empirical research demonstrated that the celebrated autonomy of post-Fordist labor often coexisted with intensified forms of surveillance, metric-driven evaluation, and performance management mediated through information systems (

Amin, 1994;

Castells, 1996). Temporal autonomy, in practice, could be accompanied by income volatility, unstable contracts, and individualized exposure to market fluctuations—conditions documented in flexible and platform-mediated work settings (

Thomson & Hünefeld, 2021;

Pourmehdi & Shahrani, 2021;

O’Connor et al., 2020). These dynamics underscore why precarity is better understood as a structural design feature of post-Fordist capitalism rather than as a residual anomaly.

In this context, post-Fordist theory has also been mobilized to explain evolving subjectivities and cultural expectations surrounding work. As

Boltanski and Chiapello (

2005) emphasize, the reorganization of capitalism incorporated critiques of hierarchy, rigidity, and bureaucracy by reframing autonomy and creativity as central to the new normative order. This shift reshaped the experiences and expectations of workers: autonomy became a moral injunction, project-based labor became a marker of modernity, and responsibility for career development shifted from institutions to individuals (

Lamberg, 2022). These transformations were particularly salient in the emergence of knowledge-intensive industries, flexible services, and transnational professional labor markets, where opportunities were often accompanied by heightened self-monitoring, peer comparison, and exposure to global competition. The ambivalence of post-Fordism is therefore reflected not only in structural labor conditions but also in the psychological and cultural landscape that shapes how workers interpret their careers, responsibilities, and risks.

The acceleration of digitalization introduces a new inflection point in this historical trajectory. Scholars widely agree that platform capitalism deepens and transforms the organizational logics initially associated with post-Fordism (

Srnicek, 2016;

Kenney & Zysman, 2016). Digital platforms function as socio-technical infrastructures, multi-sided markets, and labor regimes that convert human activity into quantifiable data, facilitate algorithmic intermediation, and reorganize entire industries. Their capacity to match, rank, and govern interactions across distributed networks redefines coordination as a computational process rather than an organizational or contractual one. In this model, economic power increasingly derives from ownership and control of data infrastructures, shifting the locus of value creation from productive efficiency to the extraction, processing, and predictive use of information (

Srnicek, 2016).

Algorithmic management has become the central governance mechanism of this new accumulation regime. Distinct from earlier managerial forms, algorithmic control relies on opaque, automated, and continuous monitoring systems that track worker performance, allocate tasks, and apply sanctions or incentives through data-driven feedback loops (

Wood et al., 2019;

Lehdonvirta, 2022). These systems embed managerial authority within the design of digital architectures, making power less visible yet more pervasive. Visibility, eligibility, and access to work opportunities are determined through proprietary metrics and reputation systems that embed power asymmetries within computational infrastructures. The result is a profound reconfiguration of labor governance: control is exercised through code, not hierarchy, and coordination is mediated by algorithms rather than supervisors or negotiated contracts. This represents a structural rupture relative to post-Fordist decentralization. While post-Fordism emphasized the dispersion of production across networks, platform capitalism recentralizes control within informational infrastructures that shape—and often automate—managerial prerogatives (

Piore & Sabel, 1984;

Silver, 2003).

The gig economy further illustrates these tensions. Although platforms promote narratives of autonomy, entrepreneurship, and self-directed flexibility, empirical research reveals that algorithmic pricing, task allocation, and reputational scoring mechanisms frequently limit workers’ agency and reinforce precarious working conditions (

Pourmehdi & Shahrani, 2021;

O’Connor et al., 2020).

Thomson and Hünefeld (

2021) argue that flexibility increasingly operates as a managerial technique for externalizing costs and shifting responsibility onto workers. These developments intersect with broader issues of inequality, global migration, and labor mobility, as digital platforms amplify existing asymmetries in access to opportunity and economic security (

Sopranzetti, 2017;

Filc, 2004). Feminist and critical political economy approaches further highlight how platform-mediated work interacts with gendered divisions of labor, care responsibilities, and welfare-state restructuring (

Fraser, 2013;

Lamberg, 2022). These insights underscore the continued relevance of post-Fordist theory while demonstrating its limitations in capturing the data-driven modalities of contemporary labor control.

Debates on Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 add an additional interpretive layer to these transformations. Industry 4.0 emphasizes automation, cyber-physical systems, and smart infrastructures, while Industry 5.0 proposes a human-centered paradigm oriented toward resilience, well-being, and sustainability. Nevertheless, empirical evidence suggests that platform capitalism often intensifies rather than mitigates asymmetries of power, embedding surveillance, algorithmic governance, and precarization within ostensibly human-centered designs. These debates align with broader analyses showing how post-Fordist values of flexibility, innovation, and decentralization are being recomposed within increasingly automated and data-centric labor regimes (

Roy, 2025;

Thorpe, 2025). The persistence of algorithmic control within systems framed as “human-centered” highlights the paradoxical ways in which autonomy and innovation continue to be tethered to intensified managerial oversight.

Taken together, this extended theoretical framework clarifies why the platform economy should be understood both as a continuation of post-Fordist transformations and as a structural break that requires new analytical tools. It retains key elements such as flexible specialization, decentralized production, and individualized responsibility, while introducing new mechanisms—datafication, algorithmic governance, infrastructural power, and predictive analytics—that exceed the explanatory scope of traditional post-Fordist paradigms. These dynamics highlight the importance of empirically mapping the intellectual evolution of the field. The bibliometric analysis conducted in this study situates platform capitalism within a broader historical and conceptual lineage, identifying continuities, ruptures, and emerging clusters that shape contemporary debates on labor, inequality, organizational governance, and the future of work.

3. Materials and Methods

For non-specialist readers, the bibliometric techniques employed in this study can be understood in straightforward terms: they allow us to map who collaborates with whom, identify which concepts and authors structure the field, and trace how research themes evolve over time. The technical details of thresholds, algorithms, and normalization procedures are provided for methodological transparency, but the core purpose of these tools is to visualize the intellectual and organizational dynamics of the Platform Economy research landscape.

To ensure the highest quality of bibliometric data and adequate coverage of the social sciences, data was retrieved from the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). WoS was selected for its comprehensive coverage of high-impact international journals, rigorous indexing standards, and provision of complete citation linkage data essential for network analysis.

The data extraction was performed on 10 September 2025. The strategy employed a precise topical query to capture the consolidation of the field. The search string used was TS = (“Platform Economy”) (Topic Search), which queries titles, abstracts, and author keywords. To ensure the coherence of the corpus and minimize “false positives,” the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied:

Indices: The search was limited to the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), and Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI).

Document Types: The analysis was restricted to “Articles,” “Review Articles,” and “Early Access” to focus on certified, peer-reviewed knowledge production, excluding editorials, letters, and book reviews.

Language: The dataset was filtered to include only publications in English to facilitate accurate keyword co-occurrence analysis and natural language processing.

Timeframe: The search covered the period from 2005 to 2024, capturing the full historical trajectory from early digitalization debates to current post-Fordist critiques.

This protocol yielded a final dataset of 1573 bibliographic records. The retrieved dataset included essential metadata for each document, such as publication year, author names, author keywords, institutional and country affiliations, journal sources, and full citation data.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations inherent in this corpus. Because the dataset relies on a single search term (“platform economy”) and exclusively on the Web of Science Core Collection in English, the representation of non-English scholarship—particularly from Latin America, China, and continental Europe—is structurally reduced. Likewise, disciplinary differences in terminology mean that adjacent studies using alternative labels (e.g., gig economy, sharing economy, platform capitalism) are only partially captured. These constraints must be considered when interpreting patterns of national, disciplinary, or authorial prominence in the results.

3.1. Analysis Techniques and Visualization

To construct and visualize the bibliometric networks, this study utilized VOSviewer (version 1.6.20), a state-of-the-art software tool designed for the algorithmic visualization of scientific landscapes (

van Eck & Waltman, 2010). Three primary analytical techniques were employed, with specific thresholds applied to ensure topological stability and visual clarity:

Co-occurrence Analysis: This was applied to all keywords (totaling 4049) to map the conceptual architecture of the field and identify dominant research themes. To filter out marginal terms and focus on the core intellectual structure, a minimum occurrence threshold of 5 was applied, resulting in 318 keywords. A thesaurus file was used to merge synonymous terms (e.g., “digital platform” and “digital platforms”; “AI” and “artificial intelligence”) to prevent fragmentation.

Citation Analysis: This was used to map the intellectual influence and hierarchical structure of the field by examining citation links between authors and journal sources. A minimum occurrence threshold of 5 was applied.

Co-authorship Analysis: This was employed to visualize collaborative structures at both the individual author and country levels. To filter the co-authorship network, a minimum occurrence threshold of 3 was applied.

For all networks, the association strength method was used for normalization, and the layout was generated using the VOSviewer clustering technique (based on the modularity function) to identify distinct thematic and social communities. In addition to standard analyses, we calculated modularity, network density, and betweenness/eigenvector centrality to quantify structural cohesion. The co-authorship network exhibited a high modularity score (Q = 0.64), confirming the presence of distinct collaborative modules.

3.2. Methodological Rationale and Sensitivity

A critical methodological choice in this study was the selection of “Platform Economy” as the primary search term, as opposed to related concepts such as “Gig Economy,” “Sharing Economy,” or “Collaborative Consumption.”

This choice was deliberate and theoretical. “Platform Economy” functions as the macro-structural concept (the organizational model), whereas “Gig Economy” specifically refers to labor relations, and “Sharing Economy” refers to consumer/ideological framing. A sensitivity check performed during the exploratory phase revealed that searching solely for “Gig Economy” skewed the results heavily toward labor law and sociology journals, potentially missing the strategic, innovation, and engineering literature essential to the “Industry 5.0” debate. Conversely, “Sharing Economy” skewed the results toward older literature (2010–2015) and marketing studies.

By anchoring the search in “Platform Economy,” the corpus successfully captures the intersection of these sub-fields, allowing for an unbiased observation of how the field has shifted from “Sharing” (consumer-centric) to “Gig” (worker-centric) narratives. To evaluate robustness, thresholds for keyword co-occurrence (3, 4, and 5 occurrences) and citation/author occurrence (3–7 documents) were varied; the resulting cluster structures remained topologically consistent.

3.3. Theoretical Grounding in Classical Bibliometric Laws

The empirical patterns observed in the data were interpreted through the lens of classical bibliometric laws, which describe fundamental regularities in scientific communication:

Price’s Law: Used to frame the longitudinal analysis of publication growth, describing the characteristic S-curve or exponential growth pattern of scientific literature as a field emerges and matures (

Price, 1963).

Lotka’s Law: Used to interpret author productivity, positing that a small cohort of highly prolific authors is responsible for a large proportion of total publications, while the majority contribute only one or two articles (

Lotka, 1926).

Zipf’s Law: Informed the conceptual analysis of keyword frequency, predicting that a few core terms dominate the discourse while a “long tail” of less frequent terms exists (

Zipf, 1949). This justifies the focus on high-frequency keywords as indicators of central concepts.

Bradford’s Law: Applied to identify the “core zones” of journals, revealing the key disciplinary venues where the discourse on the Platform Economy is most concentrated (

Bradford, 1934).

In summary, this methodological approach integrates advanced visualization tools with foundational scientometric theories to provide a multi-faceted and robust analysis. By systematically mapping the authors, concepts, journals, and collaborative networks that constitute the field, this study offers a reproducible and data-driven overview of its intellectual landscape.

4. Results

To facilitate comprehension for readers who are less familiar with network-analysis techniques, the results presented in this section emphasize the main empirical patterns in conceptual rather than technical terms. Each subsection begins by highlighting the key findings before introducing the structural or methodological details necessary to interpret the visualizations.

4.1. Knowledge Production in the Platform Economy

Figure 1 presents the annual number of publications and citations associated with the term “Platform Economy” in the Web of Science between 2005 and 2024. The overall trajectory follows the familiar logistic growth pattern described by Derek de Solla Price, revealing how new scientific fields typically evolve through phases of emergence, acceleration, and eventual consolidation.

The first stage (2005–2016) is marked by very low publication activity and limited conceptual articulation. During this formative period, only a small and relatively disconnected group of researchers engaged with the idea of the platform economy. As is characteristic of early-stage scholarly development, there was no shared terminology, no dominant theoretical lens, and little institutional visibility. The field remained an “invisible college,” with foundational ideas being shaped gradually but without yet attaining the critical mass necessary for broader academic uptake.

A noticeable inflection point emerges around 2017, initiating a second phase characterized by rapid expansion (2017–2022). The sharp rise in publication output reflects the growing societal and organizational relevance of platforms, as well as the increasing visibility of their economic and labor implications. This period corresponds to the formation of a true “research front,” with scholars from sociology, management, economics, geography, and information science converging around common questions. The field becomes more interdisciplinary, and the groundwork for a coherent body of literature begins to solidify. Funding opportunities, cross-disciplinary collaborations, and heightened public debate surrounding platform labor and digital transformation likely reinforced this acceleration.

Citations grow even more steeply than publications during this period, suggesting not only increased scholarly interest but also heightened intellectual influence. The fact that citation counts peak in 2024—one year after the peak in publications—signals a typical maturation pattern: the surge of recent research begins to inform and shape subsequent work, generating a cumulative intellectual foundation.

Beginning in 2022, the curve transitions into a plateau. Rather than indicating stagnation, this flattening reflects the consolidation of the field. By this stage, core debates, key authors, and dominant paradigms have been established, and research activity shifts from broad, exploratory contributions toward more specialized and incremental inquiries. The slight decline visible in 2024 is most plausibly explained by indexing delays rather than substantive contraction, a common phenomenon in bibliometric databases for the most recent year.

Taken together, these dynamics suggest that the “platform economy” has moved beyond its conceptual emergence and high-growth phase to become a recognized and institutionalized area of scholarly study. It now exhibits the hallmarks of a mature field: defined research clusters, consistent terminology, accumulated citation structures, and growing specialization.

The following section builds on this analysis by examining the network of highly cited authors who shape and structure knowledge production in this domain.

4.2. The Intellectual Cascade: Mapping the Hierarchical Structure of a Scientific Field

Figure 2 illustrates the sparse co-authorship network at a high productivity threshold, highlighting the fragmented collaborative structure of platform economy research.

The author citation network offers a detailed visualization of the intellectual architecture and flow of influence that structure research on the platform economy (

Table 1). Taken together, the quantitative indicators and the network graphs show that this is not a flat or diffuse scholarly domain. Instead, it functions as a hierarchical intellectual cascade in which ideas move from an early group of pioneers, through a central cohort of highly cited synthesizers, and finally to an active contemporary research front that expands and operationalizes established paradigms.

At the base of this cascade lie the foundational authors grouped in the yellow cluster, most notably Martin Kenney (313 citations) and John Zysman (256 citations). Although their citation counts are not the highest in the dataset, their structural position is decisive. Their work anchors the conceptual origins of platform capitalism—particularly its strategic, industrial, and political-economic dimensions—and serves as the reference point upon which subsequent authors build. They represent the pioneering school of thought that first articulated the mechanisms through which platforms reshape organizational models and value creation processes.

Above them—and occupying the central and most influential position in the network—appear the scholars in the green and purple clusters. This group includes the field’s most cited authors: Mark Graham (1480 citations) and Juliet B. Schor (1286 citations). Their central location in the network reflects their dual role: they draw on the foundational contributions of Kenney and Zysman and, at the same time, serve as the primary intellectual bridge to the contemporary literature. Authors such as Alex J. Wood (Total Link Strength 63) and Vili Lehdonvirta (54), also located in this central zone, similarly function as synthesizers. Their work has translated early theoretical insights into widely used critical frameworks—particularly regarding digital labor, algorithmic control, and the evolving social impacts of platform-mediated work. The high link strengths within this cluster underscore their integrative role across subfields.

Figure 3 presents a citation-based co-authorship detail that highlights the hierarchical relationships among highly cited authors within the field.

Table 2 reinforces this pattern by showing that the journals most closely associated with labor studies and digital society—especially Work, Employment and Society (2097 citations, TLS 128) and New Technology, Work and Employment (TLS 73)—constitute the principal venues where this theoretical consolidation occurs. These journals sit at the intersection of sociology, labor studies, and organizational analysis, which helps explain why the central authors occupy such an important bridging role across disciplines.

At the top of the cascade, represented by the red cluster, are the scholars who constitute the contemporary research front. This group is marked by high productivity and a growing influence. Timm Teubner, the most prolific author in the dataset with 13 publications, exemplifies this pattern. His position—together with that of other active researchers such as Christian Fieseler—illustrates how new empirical inquiries build directly upon the frameworks established by the synthesizing core. This cluster extends the field by testing theories in diverse empirical contexts and by developing applications of platform governance and algorithmic management across industries and regions. Their structural location, with citation links that flow downward into earlier clusters, visually reinforces their role as the expanding frontier of the field.

Overall, the citation network reveals a highly coherent and strongly hierarchical intellectual structure. The field is organized around a sequence of linked contributions: foundational work by early pioneers (Kenney, Zysman), followed by a group of central synthesizers (Graham, Schor, Wood, Lehdonvirta) who consolidate and articulate its key theoretical frameworks, and finally a productive research front (Teubner, Fieseler) that advances and diversifies these paradigms. This architecture is characteristic of a mature and well-structured scientific domain with an identifiable canon and a clear lineage of influence.

This section has highlighted the authors who anchor and expand knowledge production in the platform economy. The next section turns to the journals in which these authors publish, which helps reveal the disciplinary domains shaping the field. A time-sliced overlay further shows the temporal layering of these contributions: early theoretical work (average publication year ≈ 2020) forms the foundation of the network, followed by consolidation in 2021–2022, and then specialization in 2023–2024 as new thematic frontiers emerge at the periphery.

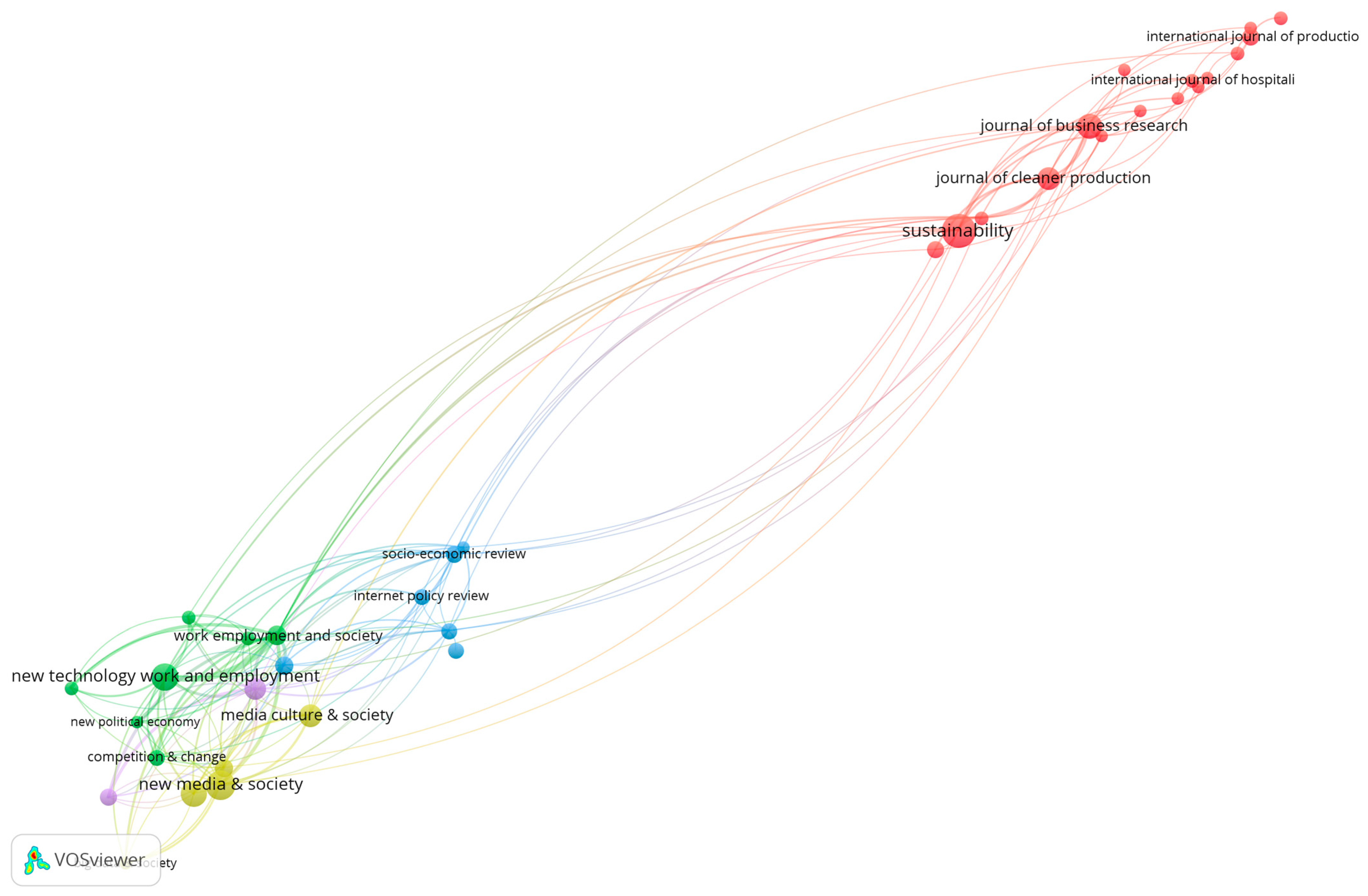

4.3. The Disciplinary Crossroads of Platform Economy Research: A Journal Citation Network Analysis

The journal-by-journal citation network for the “Platform Economy” provides a cartographic representation of the field’s intellectual foundations. Although

Figure 4 shows a more expanded network, the topological structure of the detail where there is a more dense network—see

Figure 5—reveals that this area of research is not anchored within a single disciplinary tradition but rather constitutes a critical intellectual bridge between two distinct and powerful scholarly domains: one rooted in the sociology of work and critical media studies, and the other in the fields of business, innovation, and sustainability.

The first of these domains, visualized as a dense and highly interconnected series of green and yellow clusters, can be characterized as the socio-political and labor studies pole. At the absolute center of this conversation is the journal Work, Employment and Society. This is social science at the center of the epistemic network. The quantitative data unequivocally confirms its pivotal role. It boasts the highest number of citations (2097) and, most importantly, the highest total link strength (128) by a significant margin—see

Table 2. This indicates that it is the primary intellectual anchor, the most influential source, and the most critical hub for scholarly dialogue concerning the labor implications of the platform economy. Orbiting this core are other high-impact journals such as New Technology, Work and Employment, and New Media & Society, which, with high productivity and link strengths (73 and 51, respectively), form a robust and coherent intellectual community focused on technology’s impact on work and its connection with society via culture and general social issues.

Conversely, the second domain, visualized as the red cluster, represents the business, innovation, and sustainability pole. Such scholarly conversation is primarily concerned with the business models, organizational strategies, and environmental or social governance aspects of platform firms, but not without some more social science-related and broad topics. The journal Sustainability is a key outlet in this cluster, distinguished by having the highest publication volume in the entire dataset with 29 documents. This identifies it as a major venue for contemporary research in the area. It is closely linked to other influential sources like the Journal of Cleaner Production (with a strong 984 citations) and the Journal of Business Research, which together form the intellectual core of a research stream analyzing platforms through the lenses of management, innovation, and corporate responsibility.

The most significant insight afforded by the complete network map is the overall structure of the field. The two poles described above do not exist in isolation; they are connected by a long bridge of inter-citations. This “dumbbell” or “bridge” structure is the defining feature of the platform economy’s intellectual landscape. It signifies that while the core conversations are happening within distinct disciplinary communities, the field itself is fundamentally interdisciplinary, defined by the flow of knowledge between them. Scholars studying platform labor in sociology journals are cited and being cited by researchers examining platform business models in management journals. This cross-pollination is what constitutes the platform economy as a unique and coherent field of study.

The journal citation network analysis demonstrates that a comprehensive understanding of the Platform Economy requires engagement with two separate but interconnected bodies of literature. The field’s intellectual vitality derives precisely from its position as an interdisciplinary conduit, forcing a necessary dialogue between critical social theories of work and technologically driven theories of business innovation. The structure of the network makes it clear that the most impactful research is that which successfully navigates and integrates insights from both foundational scholarly traditions.

4.4. The Global Collaboration Landscape of Platform Economy Research: A Narrative Analysis

Table 3 summarizes the international co-authorship structure of platform economy research, reporting publication volume, citation counts, and total link strength by country.

Figure 6 provides a structural overview of the international co-authorship network in platform economy research, illustrating its topology, central nodes, and cross-regional linkages.

Table 1 complements this visualization by reporting each country’s publication volume, total citations, and collaborative intensity (Total Link Strength). Examined together, these indicators clarify the distinct functional roles that different nations play within the global research system.

The network is dominated by three leading nodes: the People’s Republic of China, the United States, and England. Each occupies a different position in terms of scientific contribution. China stands out as the most prolific producer of research, with the highest number of published documents (179). This substantial output positions China as the principal engine of volume within the field. In contrast, the United States and England emerge as the main centers of intellectual influence. Their high citation counts (7902 and 7077, respectively) underscore their roles in shaping the conceptual foundations and theoretical debates surrounding platform capitalism and digital labor.

England plays an especially distinctive role: with the highest Total Link Strength (142), it functions as the most central and diverse collaborative hub in the network, surpassing both the United States (114) and China (96). This indicates that England serves as the primary convergence point for international co-authorship, connecting otherwise separate regional research communities and enabling the circulation of knowledge across disciplinary and geographic boundaries.

The structure of the network further reveals a set of coherent regional collaboration clusters. One highly integrated core links England, the United States, Germany, and the Netherlands, forming a transatlantic research bloc characterized by dense ties and high scholarly impact. Parallel to this, China anchors a second major cluster that includes Australia and selected European partners, constituting an Asia-Pacific-centered network with growing global reach. A third cluster, centered on Spain and France, reflects a Latin European research axis that extends to South American countries—suggesting that linguistic and cultural proximities continue to shape scientific collaboration patterns.

Taken together, these dynamics show that the global co-authorship landscape is multifaceted rather than uniform. China contributes primarily through high productivity; the United States and England through conceptual leadership and high scholarly impact; and England through exceptional network centrality. These are distinct and non-interchangeable dimensions of scientific influence—productivity does not equate to impact, and impact does not guarantee collaborative centrality. Understanding these roles is essential for interpreting how ideas travel, consolidate, and evolve within this field.

Viewed alongside the author-level citation networks discussed earlier, the national collaboration structure reinforces the presence of a clear epistemic hierarchy. A core group of Anglo-American scholars—supported by robust institutional networks—continues to shape the foundational debates and theoretical vocabulary of the field. Their work bridges critical labor sociology with management and innovation studies, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of platform economy scholarship. Meanwhile, China’s rapidly expanding empirical output contributes decisively to diversifying cases, contexts, and methodological approaches, even if conceptual agenda-setting remains concentrated in Anglophone institutions.

This international configuration generates a productive tension within the epistemic field. Knowledge circulates across two major scholarly domains: the socio-political study of labor (anchored in journals such as Work, Employment and Society) and the strategic and organizational study of platform business models (prominently represented in Sustainability and related journals). The coexistence of these domains obliges dialogue across traditions that rarely meet in other areas of organizational research, and this interdisciplinary exchange is one of the field’s distinctive strengths.

In sum, China’s role as the leading producer of documents, the United States’ and England’s position as conceptual centers, and England’s function as the global network facilitator together illustrate the complex and hierarchical nature of scientific collaboration in this domain. These patterns set the stage for the next section, which examines how authors connect within this system by introducing the metaphor of an “archipelago” to describe the structure of co-authorship groups.

4.5. An Archipelago of Influence: The Collaborative Structure of Platform Economy Research

The co-authorship map (

Figure 5) shows that platform-economy research is not organized as a single integrated community. Instead, the field is composed of several distinct research clusters that function as relatively autonomous “islands,” with limited connections between them. This pattern indicates that collaboration tends to occur within small, cohesive groups rather than across the field as a whole.

The modularity measure (Q = 0.64) confirms this fragmentation: most clusters are internally dense but have few bridging links to other groups. The main Graham-centered cluster—connected with the Woodcock and Lehdonvirta groups—displays strong internal cohesion, whereas the overall network density (0.12) remains low. This means that information circulates rapidly within each cluster but diffuses slowly across them, quantitatively supporting the “archipelago” metaphor.

To understand the internal organization of the dominant cluster, we isolated the sub-network centered on Mark Graham (

Figure 7). This component exhibits a hub-and-spoke structure: Graham’s node shows the highest betweenness centrality, acting as the principal connector between three internally cohesive cliques represented by the red, yellow, and pink subgroups. The red cluster (Graham, Van Doorn, Ferrari) forms a tightly knit network typical of long-standing collaborations or multi-institutional research projects such as Fairwork. The yellow cluster (Heeks, Woodcock) reflects a focus on development studies and gig-economy research, while the pink cluster (Lehdonvirta, Wood, Rani) extends the digital-labor conversation into adjacent areas of political economy and regulation.

Graham’s centrality is crucial: without this bridging position, the modularity patterns suggest that the cluster would likely fragment into separate units. This indicates that the “Mainland” is not a single, homogeneous group but a set of interconnected research teams maintained through key intellectual brokers.

Figure 8 illustrates the co-authorship network by authors, highlighting the fragmented and clustered structure of collaborative relationships within platform economy research. A temporal overlay analysis (

Figure 9) reveals how these clusters have evolved. Older foundational contributions (circa 2020), represented by darker colors, include scholars such as Helmond, Adam, and Schor, whose work shaped early debates on platformization and the sharing economy. The more recent consolidating core (2021–2022), shown in teal, corresponds to the Graham–Woodcock axis, which standardized the digital-labor literature during the field’s expansion. Newer contributions (2023), highlighted in bright yellow, appear at the periphery. These include authors like Ferrari and Kongsvik, whose work signals emerging specializations such as algorithmic auditing or sector-specific studies of platform governance.

This temporal layering shows that the “archipelago” is not a static geographic pattern but a dynamic effect of specialization: new islands emerge as the field matures and subdivides into more focused research lines.

At the center of this map lies the most influential landmass: the Graham-led cluster. As shown in

Table 4, Graham is the most cited author (1480 citations) and plays a central role in the intellectual consolidation of digital-labor research. His highly cited article “Good Gig, Bad Gig” exemplifies this influence. His node also has the highest Total Link Strength (9), visually represented by multiple strong co-authorship connections. This group—which includes Vili Lehdonvirta, Alex J. Wood, Jamie Woodcock, and Richard Heeks—forms a coherent school of thought, often associated with institutions such as the Oxford Internet Institute and the University of Manchester.

Outside this central mainland, other influential but more isolated islands appear. Timm Teubner (blue cluster) is the most prolific author (13 documents) but collaborates narrowly, reflecting a parallel research line centered on market design and platform economics. Juliet B. Schor, despite being the second most cited author (1286 citations), appears in a small cluster with only one primary collaborator (Mehmet Cansoy). Her influence comes from a set of highly cited contributions rather than a large co-authorship network.

Similarly, pioneers such as Martin Kenney and John Zysman form a distinct, self-contained collaborative unit with limited connection to the rest of the field. Even highly influential figures such as Annabelle Gawer—author of one of the most cited articles in platform studies—remain structurally isolated within the co-authorship map, showing no collaborative ties under the “platform economy” keyword despite their conceptual importance.

Overall, the co-authorship network of platform-economy research is characterized by concentrated, high-impact research cells rather than a unified scholarly community. A central, cohesive group led by Mark Graham shapes much of the digital-labor debate, while other prominent scholars operate within smaller, independent clusters. This “archipelago” structure suggests that the field’s intellectual richness stems from multiple parallel schools of thought, even as bridges between them remain limited.

4.6. The Conceptual Architecture of the Platform Economy

Having described the social, institutional, and geopolitical structures that shape the production of knowledge in this field, we now turn to the substance of that knowledge itself. This section examines the conceptual architecture of platform economy research, asking a central question: What themes, ideas, and intellectual frontiers organize the scholarly conversation?

To map this terrain, we conduct a co-occurrence analysis of authors’ keywords. This method visualizes how researchers describe their own work and reveals clusters of concepts that function as thematic communities. The proximity of terms in the network indicates how ideas are related, while the overlay visualization—colored by average publication year—allows us to identify shifts in intellectual focus over time. Together, these tools offer a data-driven cartography of the field’s evolving debates and conceptual priorities.

The VOSviewer map (

Figure 10) provides a panoramic overview of this landscape. Rather than a unified discourse, the field appears as a set of interrelated but distinct research conversations. These conversations articulate the tensions and synergies between technology, labor, business models, and governance that define contemporary discussions of platform capitalism.

At the center of the network lies a conceptual triad composed of the terms “platform economy,” “gig economy,” and “sharing economy.” Their prominence—evidenced by 386, 214, and 254 occurrences, respectively, in

Table 5—confirms their role as the dominant pillars of the field. “Platform economy,” the search term that defines the corpus, naturally serves as the network’s center of gravity. Its extensive connections to nearly all other clusters demonstrate its integrative function.

The other two nodes, however, represent distinct conceptual lenses rather than interchangeable labels. “Sharing economy,” located within the orange cluster, connects strongly to notions such as Airbnb, collaborative consumption, and trust, reflecting early narratives focused on peer-to-peer exchange and resource utilization. In contrast, “gig economy,” located within the teal cluster, anchors the labor-oriented critique of platforms. It is closely linked to concepts such as platform work, precarious work, and algorithmic management, underscoring the shift in attention from consumption models to labor governance and worker experiences. While interconnected, these three terms mark different intellectual debates that collectively shape the broader understanding of platform capitalism.

Beyond this central triad, the network reveals several thematic clusters—what might be understood as “research neighborhoods” within the field. The red cluster, labeled here as the engine of innovation and business, concentrates on the technological and managerial aspects of platforms. Keywords such as “innovation,” “entrepreneurship,” “business models,” and “digital technology” characterize this area. It also includes Uber—one of the most widely studied cases—which, with a high link strength (88), functions as a paradigmatic example for analyzing regulatory tensions, market design, and platform governance.

Another major cluster is the teal one, which we call the human dimension of platform labor. This is one of the densest and most socially significant areas of research, focusing on working conditions, labor relations, and the consequences of algorithmic management. Terms such as “gig work,” “digital labor platforms,” “migrant workers,” and “precarious work” highlight concerns tied to inequality and instability in the labor market. Closely related is what we label the sociology of labor and resistance, a subcomponent emphasizing worker agency through concepts like resistance, organization, and worker voice. Together, these clusters represent the critical examination of how platform-mediated labor reshapes managerial control and worker autonomy—issues that arguably extend beyond post-Fordist frameworks.

Crucial to understanding the dynamics of this conceptual system are the bridging concepts that connect clusters. The keyword “regulation,” located within the orange governance cluster, serves as a central bridge linking discussions about business models, technological infrastructures, and labor conditions. Similarly, empirical cases such as Uber and Airbnb function as boundary objects that help researchers integrate abstract theoretical discussions with real-world socioeconomic phenomena.

Figure 11, which overlays the temporal dimension of keyword appearance, reveals a notable shift in the field’s intellectual focus between 2021 and 2023. Earlier work (blue and purple nodes) is rooted in themes associated with the “sharing economy,” trust, and collaborative consumption—reflecting the early optimism and consumer-oriented framing of platforms. However, the most recent contributions (yellow nodes) show a decisive shift toward labor-centered concerns. Keywords such as “platform work,” “gig workers,” “precarious work,” “working conditions,” and “food delivery” dominate the emerging research frontier. This indicates a significant analytical transition: from understanding platforms as business or consumption innovations to examining them as employers and labor regimes with profound socioeconomic consequences.

The overlay thus reveals a field undergoing rapid conceptual evolution. The intellectual center has moved away from celebratory narratives of peer-to-peer exchange and toward a more critical examination of platform capitalism, algorithmic management, and the changing nature of work. The bright yellow nodes on the left side of the map represent the themes currently shaping the next wave of scholarship, marking the areas where the field is actively redefining its theoretical and empirical boundaries.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpreting the Intellectual and Disciplinary Architecture of the Platform Economy

The intellectual structure revealed by our analysis reflects not simply a network of authors and journals but a deeper reconfiguration of the conceptual foundations through which contemporary capitalism is understood. Rather than reiterating descriptive patterns such as the position of clusters or the direction of citation flows, the key insight is that the field organizes itself around unresolved tensions between post-Fordist paradigms and the emerging logics of digital capitalism. Post-Fordist scholarship emphasized flexible specialization, distributed production, and the decentralization of authority across networks. Yet the platform economy introduces a qualitatively different regime of coordination based on the centrality of data infrastructures, algorithmic classification systems, and the capacity to govern market interactions from a distance. The intellectual landscape mirrors this shift: early contributions ground the field in debates on flexibility and network governance, whereas contemporary work interrogates how platforms simultaneously expand flexibility and recentralize control through technical architectures that elude traditional organizational categories.

A second interpretive dimension of the field’s architecture concerns its pronounced interdisciplinarity. The juxtaposition of labor sociology and innovation/management studies is not merely an empirical feature of the bibliometric network but a substantive expression of the platform economy’s dual character. From the perspective of labor sociology, platforms intensify longstanding neoliberal dynamics by displacing risk onto workers, restructuring employment relations, and embedding managerial authority within opaque algorithmic systems. Scholars in this tradition foreground issues of precarity, surveillance, asymmetries of power, and the erosion of collective protections. In contrast, research in management and innovation frames platforms as engines of scalability, ecosystem orchestration, and business model transformation. These studies emphasize efficiency, strategic differentiation, and the novel organizational possibilities made available by digital infrastructures. The coexistence of these traditions highlights a central analytical challenge: the platform economy cannot be adequately explained using a single disciplinary lens because it is simultaneously a labor regime, a technological system, and a strategic organizational form.

Interpreting the intellectual architecture, therefore, requires acknowledging the ambivalent relationship between platforms and post-Fordist transformations. On one hand, many features of the platform economy—outsourcing, individualized responsibility, project-based work, and the valorization of entrepreneurial subjectivities—represent the continuation of post-Fordist tendencies. On the other hand, the mechanisms through which these tendencies are operationalized differ fundamentally from those envisioned in post-Fordist theory. Algorithmic management, for example, replaces the human supervisor with computational systems that allocate tasks, monitor performance, and enforce behavioral norms in real time. Data infrastructures reconfigure the boundary between firm and market by integrating coordination processes that would otherwise rely on negotiation or relational networks. The platform owner becomes an infrastructural actor whose power is derived not from direct employment or hierarchical authority but from controlling access to visibility, matching, and transaction flows. These dynamics constitute a partial rupture with post-Fordism, suggesting that flexibility in the platform era is inseparable from new forms of infrastructural domination.

The intellectual architecture also reveals a gradual transition from normative optimism toward more critical and institutionalized analyses of platforms. The early “sharing economy” narrative, prominent in foundational literature, imagined platforms as vehicles of collaboration, mutuality, and efficient resource allocation. Over time, however, empirical evidence and theoretical reflection have shifted scholarly attention toward issues of inequality, regulatory gaps, and the institutional consequences of digital intermediation. Recent literature conceptualizes platforms as political-economic infrastructures that shape markets, labor processes, and state capacities. The move from celebratory frameworks to critical institutionalism indicates that the field is undergoing a maturation process, progressively integrating insights from political economy, economic sociology, critical management studies, and science and technology studies. This broadening of theoretical inputs deepens the field’s interpretive complexity and signals its alignment with wider debates about the nature of contemporary capitalism.

Finally, the coexistence of genealogical pioneers, mid-spectrum synthesizers, and an increasingly specialized research frontier suggests that the field is converging toward a new analytical synthesis. The intellectual architecture does not merely map who cites whom; it reveals the emergence of a conceptual vocabulary capable of addressing the interplay between digital infrastructures, labor governance, and organizational strategy. Terms such as “platform capitalism,” “infrastructural power,” and “algorithmic governance” indicate that the field is moving beyond the analytical frameworks inherited from industrial sociology and classical management theory. The challenge ahead is not only empirical but also theoretical: to articulate models that bridge macro-level transformations in accumulation regimes with micro-level dynamics of labor control, worker agency, and platform governance. The structure identified in our analysis provides the foundation for this synthesis by delineating the conceptual convergences, disciplinary bridges, and interpretive tensions that define the contemporary study of the platform economy.

5.2. Synthesis and Future Directions of Platform Economy Research

The findings of this study, when interpreted beyond their descriptive content, indicate that research on the platform economy has reached a stage of conceptual consolidation while simultaneously confronting unresolved theoretical challenges. Rather than reiterating the specific clusters or co-occurrence patterns documented earlier, the key contribution of this synthesis lies in interpreting how those structures illuminate broader transformations in the organization of work, governance, and value creation. The citation genealogy—from foundational analyses of digital transformation to contemporary scholarship on algorithmic management—demonstrates the field’s cumulative development but also underscores the need to reassess inherited conceptual categories. The evolution of the field suggests a progressive displacement of post-Fordist markers such as networked flexibility, contractual decentralization, and horizontal collaboration in favor of frameworks that foreground infrastructural power, automated control, and the asymmetric distribution of risk. This shift marks an important theoretical turning point: platform capitalism appears less as the continuation of post-Fordism than as an emergent accumulation regime with its own institutional logic.

A central theme emerging from this synthesis is the growing recognition that algorithmic management constitutes a qualitatively distinct mode of labor governance. While earlier workplace transformations were mediated through organizational hierarchies, managerial discretion, or negotiated coordination, platforms increasingly embed governance mechanisms directly into their technological architectures. Algorithms allocate visibility, structure temporal rhythms of work, determine access to income, and discipline workers through ratings, reputational scores, and automated deactivation. These dynamics challenge classical assumptions about labor control developed in both Fordist and post-Fordist frameworks. Fordism’s bureaucratic stability and post-Fordism’s negotiated flexibility give way to what can be described as programmable labor conditions, where the parameters of work are continuously recalibrated by opaque systems. Future research must therefore refine the conceptual boundaries between flexibility and control, autonomy and dependency, and value creation and value extraction in environments governed by algorithmic infrastructures.

Another implication of the field’s evolution concerns the temporal trajectory of its core concepts. The conceptual shift from the “sharing economy” to the “gig economy” and finally to “platform capitalism” reflects not merely a terminological change but a deeper reorientation of scholarly attention. Early studies emphasized peer-to-peer exchange, collaborative consumption, and narratives of democratized access to resources. As platforms scaled and consolidated, research increasingly turned toward the socio-economic consequences of gig work, emphasizing precarity, fragmentation of worker protections, and the erosion of collective bargaining. The most recent scholarship treats platforms not simply as marketplaces but as institutional actors that shape urban systems, financial infrastructures, regulatory frameworks, and global labor markets. This progression underscores that the platform economy should be theorized not as an isolated phenomenon but as a structural transformation in the architecture of capitalism. Future work must therefore move toward integrated theories that account for platforms’ role in reshaping sovereignty, competition, labor segmentation, and the material organization of everyday life.

The global asymmetries observed in the scholarly field carry significant conceptual and political implications. The concentration of theoretical agenda-setting in Anglophone institutions, alongside the extensive empirical research emerging from China and other parts of Asia, mirrors broader inequalities in global knowledge production. These asymmetries risk reinforcing a center–periphery dynamic in which the Global South functions primarily as an empirical site rather than a generator of conceptual innovation. Yet many of the most consequential transformations associated with platform work—informalization, hybrid employment regimes, dependence on migrant labor, and state-led digitalization—are most visible outside the Anglophone world. Consequently, future research should prioritize diversifying theoretical inputs, integrating regionally grounded epistemologies, and recognizing alternative regulatory and organizational forms that challenge or complicate dominant models. Expanding the theoretical canon in this way is crucial for developing a globally attuned sociology of platform capitalism that avoids reproducing epistemic hierarchies.

Beyond theoretical matters, the structure of the field highlights important methodological opportunities. Static network visualizations illuminate intellectual lineages, but they do not fully capture the dynamic processes through which ideas diffuse, transform, or decline over time. Future bibliometric studies could integrate temporal network analysis, main-path analysis, or genealogical tracing to identify the precise conceptual routes through which post-Fordist frameworks have been translated into contemporary theories of algorithmic governance. Additionally, mixed-method approaches that combine large-scale bibliometrics with qualitative investigations—such as ethnographies of platform work, comparative regulatory analyses, or studies of technical infrastructures—would enable a richer account of how macro-level institutional transformations intersect with micro-level worker experiences. Such integration is essential for understanding not only how platforms operate but also how they are lived, resisted, and negotiated in diverse socio-economic contexts.

5.3. Industry 5.0 as an Interpretive Lens (Not a Bibliometric Result)

Industry 5.0 does not emerge in this study as a coherent bibliometric cluster or as a central keyword within the platform-economy research landscape. Its presence in the dataset is limited, and it does not meet the empirical thresholds required to constitute a thematic community. For this reason, Industry 5.0 should not be interpreted as one of the descriptive findings of the analysis. Instead, Industry 5.0 is used here as a normative and forward-looking framework that helps reflect on the broader implications of the patterns uncovered by the bibliometric evidence. Whereas Industry 4.0 imaginaries emphasize automation, efficiency, and data-driven optimization, Industry 5.0 reintroduces human agency, creativity, well-being, and resilience as guiding principles for thinking about organizational futures. This contrast provides an interpretive lens through which to situate the empirical findings on algorithmic management, infrastructural power, and the asymmetric distribution of risks in platform-mediated labor.

Framing Industry 5.0 in this way allows us to distinguish clearly between what the data show—the consolidation of platform capitalism as an institutional regime characterized by algorithmic control—and what future trajectories might entail under alternative political, regulatory, or organizational arrangements. The human-centric promises associated with Industry 5.0 highlight potential avenues for institutional reform, yet their transformative capacity remains conditional on substantive changes in governance, labor protections, and data regulation. Without such reforms, these paradigms risk functioning as adaptive narratives that legitimize continuity rather than structural change.

By positioning Industry 5.0 explicitly as an interpretive perspective rather than an empirical result, this study underscores the importance of maintaining analytical clarity while also engaging with debates on possible organizational futures beyond the current logic of platform capitalism.

5.4. Practical and Organizational Policy Implications

The bibliometric analysis developed in this study not only clarifies the conceptual and intellectual architecture of platform economy research but also illuminates a series of practical implications for organizations, regulators, and scholars who engage with platform-mediated forms of work and governance. These implications derive from the structural features identified across the networks—particularly the centrality of algorithmic management, the consolidation of labor-focused research frontiers, and the interdisciplinary bridge connecting sociological critiques with managerial and technological studies.

At the organizational level, the findings suggest that platforms introduce a distinctive mode of coordination in which managerial authority is embedded within computational infrastructures rather than hierarchical supervision. For firms adopting platform-like business models or algorithmic work allocation systems, this implies that governance is increasingly enacted through data architectures that shape workers’ visibility, access to tasks, and performance evaluation. Organizational leaders must therefore recognize that algorithmic systems are not neutral tools but institutional actors that structure opportunities and constraints. Ensuring algorithmic transparency, developing internal audit mechanisms, and incorporating worker feedback into system design represent critical steps toward mitigating opacity and potential biases in digital management practices.

From a policy perspective, the global asymmetries that characterize both knowledge production and platform labor markets highlight the urgency of developing regulatory frameworks capable of addressing the structural vulnerabilities embedded in platform-mediated work. The prominence of concepts such as precarious work, algorithmic control, and labor resistance in recent scholarship indicates mounting concerns regarding the erosion of traditional protections associated with employment. Policymakers should therefore consider regulatory approaches that expand the scope of labor protections to encompass algorithmically governed environments, including rights to explanation for automated decisions, limits on unilateral deactivation, and baseline standards for working conditions in gig-based sectors. Such interventions are necessary to counteract the redistributive effects of platforms that often externalize risk onto workers while centralizing control in digital infrastructures.

For academic and practitioner communities outside bibliometrics, the structural mapping provided in this study offers a clearer understanding of how ideas circulate and gain influence in debates on the future of work. The identification of a consolidated intellectual core—organized around digital labor, organizational transformation, and the socio-economic implications of platforms—signals where conceptual authority is being produced and where emerging insights are likely to originate. This knowledge is valuable for scholars seeking to position their work within relevant conversations, for practitioners aiming to deploy evidence-based approaches to platform governance, and for interdisciplinary teams seeking to bridge technological, managerial, and social analyses. The field’s evolution underscores that platform governance cannot be addressed solely through technical or managerial lenses but requires integrated perspectives that combine organizational strategy with labor rights, data regulation, and societal well-being.

Taken together, these practical and policy implications reinforce a central conclusion of the study: platforms constitute an institutional transformation that reshapes managerial authority, labor relations, and regulatory responsibilities. Understanding the epistemic structure behind these debates equips organizations, policymakers, and scholars with a more informed basis from which to design interventions that promote fairness, transparency, and sustainability in platform-mediated environments.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that research on the platform economy constitutes a coherent and mature field whose intellectual genealogy can be traced through successive waves of scholarship. From the foundational analyses of Fordism and post-Fordism to the contemporary expansion of platform capitalism, scholars have established a clear citation cascade that structures the field into pioneers, synthesizers, and current research fronts. This trajectory confirms that the platform economy is not an isolated phenomenon but an extension and reconfiguration of historical debates on labor, production, and governance. The bibliometric evidence highlights both the consolidation of this intellectual architecture and its capacity to adapt to rapidly evolving socio-economic realities.

The analysis further reveals that interdisciplinarity is not merely a complementary feature but the defining characteristic of the field. The journal citation networks show a pronounced bridge structure connecting sociological traditions of labor studies with business-oriented analyses of innovation, strategy, and sustainability. The intellectual vitality of platform economy research derives precisely from this dual anchoring, which obliges dialogue between critical approaches to precarity and managerial perspectives on organizational transformation. This finding underscores the importance of fostering cross-disciplinary engagement to fully grasp the multidimensional character of digital platforms as technological infrastructures, labor regimes, and organizational ecosystems.

A key insight emerging from the results is the temporal shift in conceptual emphasis. Whereas early studies highlighted the sharing economy’s potential for trust, collaboration, and efficiency, recent scholarship has shifted decisively toward themes of labor precariousness, algorithmic control, and resistance. This critical turn demonstrates the field’s responsiveness to empirical realities—especially the lived experiences of gig workers and the broader erosion of Fordist protections under neoliberal capitalism. The conceptual triad of platform economy, gig economy, and sharing economy therefore operates not as interchangeable labels but as distinct and interrelated analytical categories that capture different dimensions of digital capitalism’s contradictions.

This critical turn also confirms that the platform economy represents not an isolated development but a distinct evolutionary phase. The bibliometric evidence—particularly the displacement of “collaborative consumption” by “algorithmic management” as a dominant theme—supports the argument that the field has moved beyond post-Fordism. Whereas post-Fordism emphasized flexibility in labor markets, the current research front highlights the programmability of labor. Scholars are no longer debating whether work has become more flexible but rather how that flexibility is increasingly structured and constrained through digital infrastructures. In this sense, the platform is not merely a market matchmaker; it is a new institutional form that fuses the decentralization associated with post-Fordism with a hyper-centralized mechanism of value extraction. This shift necessitates the “re-examination of established categories” outlined in the introduction.

The study also highlights the uneven geography of knowledge production. China emerges as the largest producer of empirical research, whereas the USA and England dominate theoretical agenda-setting, with England functioning as the central hub in global collaboration networks. This asymmetry reflects broader dynamics of academic capitalism and raises concerns regarding epistemic justice and the marginalization of perspectives from the Global South. Addressing these imbalances requires incorporating diverse epistemologies and recognizing contributions from regions most affected by platform-mediated labor yet least represented in theoretical debates.

Taken together, these findings show that platform capitalism has evolved into a distinctive organizational regime whose future trajectories will depend on how societies regulate data infrastructures, algorithmic governance, and the distribution of risks and protections across labor markets. Building on this, the structural mapping presented here points toward two critical avenues for future bibliometric inquiry. First, from a methodological standpoint, research should move beyond static network snapshots toward temporal citation-flow analyses—such as Main Path Analysis—to trace the precise genealogical routes through which post-Fordist concepts have been translated into, or displaced by, theories of algorithmic management. Second, regarding the sociology of scientific knowledge, future work should examine how gender, race, and disciplinary background intersect with thematic dominance. Determining whether marginalized voices are systematically confined to specific thematic “islands” would provide essential insight into the epistemic politics of digital capitalism research.

Overall, this paper contributes by mapping the intellectual, conceptual, and collaborative architecture of platform economy research while situating it within the longer historical arc of organizational transformations beyond post-Fordism. By offering empirical evidence and theoretical synthesis, it establishes a foundation for future inquiry that is both rigorous and reflexive. The central challenge moving forward is to ensure that scholarship does not merely describe the platform economy but actively informs debates on how to govern it in ways that foster fairness, sustainability, and inclusivity. The future of organizational research lies in maintaining critical engagement with the contradictions of digital capitalism while articulating pathways toward more democratic and equitable forms of work and organization.