1. Introduction

Access to sufficient funding is one of the major obstacles that entrepreneurs in South Africa encounter, especially in the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector. SMEs are broadly acknowledged as essential players in economic growth and employment generation. Nevertheless, despite financial reforms after apartheid, access to funding continues to be inequitable. Entrepreneurs belonging to historically marginalized communities, particularly women and young people, still encounter systemic obstacles to obtaining credit.

Fatoki and Asah (

2011) state that SMEs frequently face challenges in obtaining credit because of strict collateral demands, inadequate financial documentation, and the lack of dependable credit information systems. These problems lead to financial exclusion, which limits the growth and sustainability of small enterprises.

Mutezo (

2015) and

Nethengwe and Mnisi (

2024) contend that while SMEs play a crucial role in job creation and innovation, numerous businesses still lack access to formal financial services because of entrenched institutional and market failures.

These difficulties are particularly evident in informal businesses, which usually do not have the necessary registration and paperwork demanded by conventional lenders. Lacking official credit records or business licenses, informal enterprises frequently depend on expensive or unregulated financing options. Gender inequalities further intensify exclusion. According to

Masocha (

2020) and

Nethengwe and Mnisi (

2024), female entrepreneurs encounter prejudiced lending practices, limited asset ownership, and cultural values that hinder their access to financial and non-financial resources. These overlapping obstacles emphasize the necessity for inclusive funding strategies designed for the realities of South Africa’s varied entrepreneurial environment.

While SMEs are seen as drivers of inclusive growth, their impact on national output is still limited by funding shortfalls. Conventional financial organizations typically view SMEs as high-risk, primarily due to inconsistent income flows, minimal collateral, and restricted credit history (

Herrington et al., 2010). These views strengthen hesitance to lend and impede SME growth. Tackling these limitations may enhance business results while furthering wider development objectives, such as creating jobs and reducing poverty (

Rasel & Win, 2020).

In reaction, various different funding methods have surfaced. This study emphasizes three areas: microloans, venture capital, and gender-sensitive grants. Microloans, usually provided by microfinance institutions (MFIs) and development finance organizations (DFIs), support entrepreneurs who are shut out from traditional banking (

Chikadzi, 2022). While microfinance enhances immediate access to funds, research regarding its long-term developmental impacts is inconclusive (

Banerjee et al., 2015). Venture capital focuses on rapidly expanding startups, particularly in areas such as fintech, green tech, and digital platforms. Nonetheless, South Africa’s venture capital ecosystem is still underdeveloped and primarily focused in major urban areas (

Metrick & Yasuda, 2011).

Grants centered on gender seek to alleviate the financial barriers encountered by women entrepreneurs. These funds offer essential financial support to women encountering systemic challenges in conventional credit markets (

Nethengwe & Mnisi, 2024). Rooted in principles of gender finance (

Kabeer, 1999), these initiatives foster independence, entrepreneurship, and inclusive economic involvement. Nonetheless, their influence is still inconsistent among provinces and demographic groups, prompting worries about effectiveness and fairness.

Despite increasing acknowledgment of these alternatives, ongoing differences still exist in their implementation and accessibility. Women, young people, and rural business owners continue to encounter considerable challenges in securing funding. Although microloans, venture capital, and gender-focused grants offer possible solutions, they still fail to tackle deep-seated market failures and systemic exclusions. This study seeks to explore the operation of these funding mechanisms in South Africa’s entrepreneurial landscape, analyze their inclusivity, and assess their role in fostering sustainable business growth.

Today’s entrepreneurs depend on various financial resources: microloans, venture capital, and specific grant funding. However, access to these resources is still unequal. Women, young people, and business owners in underserved areas encounter multiple challenges stemming from collateral shortages, credit restrictions, and systemic biases.

Access is further restricted by intricate application procedures, a lack of financial expertise, and inadequate support systems. These barriers limit the sector’s broader developmental effect, particularly with regard to job creation and local economic empowerment, in addition to impeding SME growth.

Tackling these funding disparities requires comprehensive reform. This involves streamlining access methods, incorporating financial literacy initiatives, advocating inclusive investment approaches, and weaving equity factors into public and private funding frameworks. These actions can assist in closing the funding gap, encourage fair involvement, and enhance the lasting viability of the SME sector.

This study examines the availability, use, and growth impacts of three funding methods—microloans, venture capital, and gender-sensitive grants—on SMEs in South Africa. It examines how these tools confront institutional and structural obstacles, particularly for marginalized groups like women and young business owners. The aim is to generate evidence-backed suggestions that could enhance inclusive financing policies and further South Africa’s goal of a vibrant and fair entrepreneurial economy.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks: Access to Finance Theory, Gender Finance, and Innovation Ecosystems

The Theory of Access to Finance declares that fair access to financial services like credit, savings, and insurance is essential for alleviating poverty and fostering inclusive entrepreneurship (

Ozili, 2020). This theory highlights the notion that access to a variety of financial products allows individuals, especially from marginalized or underserved communities, to invest in business ventures, mitigate risks, and stabilize consumption, therefore enhancing their economic resilience. In this context, microloans and gender-specific grants are thoroughly analyzed to assess their impact on reducing financial exclusion for underbanked entrepreneurs in South Africa. These tools aim to close gaps in the formal financial sector by offering affordable and accessible financial resources, allowing small-scale entrepreneurs to surmount obstacles that have traditionally restricted their economic involvement.

Alongside this, Gender Finance Theory, based on Gender and Development research as described by

Kabeer (

1999), claims that financial systems frequently perpetuate and reinforce gender disparities. It emphasizes the structural and social elements that limit women’s access to formal financing, including biased lending practices, absence of collateral, and societal norms that diminish the value of women’s economic contributions. This theory guides the critical analysis of the difficulties women entrepreneurs encounter in obtaining venture capital (

Shava, 2018) and acquiring gender-responsive grants, both crucial for expanding businesses and attaining economic empowerment. Acknowledging these systemic obstacles results in supporting specific financial tools and policy measures aimed at creating equal opportunities for women-led businesses.

Additionally, this study uses the concept of intersectionality to strengthen the explanatory power of gender finance theory by emphasizing the ways in which gender interacts with race, region, and sectoral context to create complex experiences of exclusion.

Within the South African landscape, Black women entrepreneurs in rural regions or undercapitalized industries frequently face multiple challenges such as biased credit evaluations, distance from financial institutions, and devaluation of their business fields. This intersectional perspective allows this study to identify the complex financial access obstacles that extend beyond just gender, providing a deeper insight into entrepreneurial challenges.

The Innovation Ecosystems Theory broadens perspective by highlighting that high-growth entrepreneurship relies not just on the availability of capital but also on supportive networks, institutional connections, and the exchange of knowledge (

Autio & Thomas, 2014). This perspective is important in environments with limited resources, where venture capital is crucial for promoting innovation and business development by linking entrepreneurs with mentors, industry specialists, and strategic allies. Together, these theoretical frameworks offer a robust basis for examining the relationships between financial access, gender equality, and entrepreneurial creativity within South Africa’s changing economic environment.

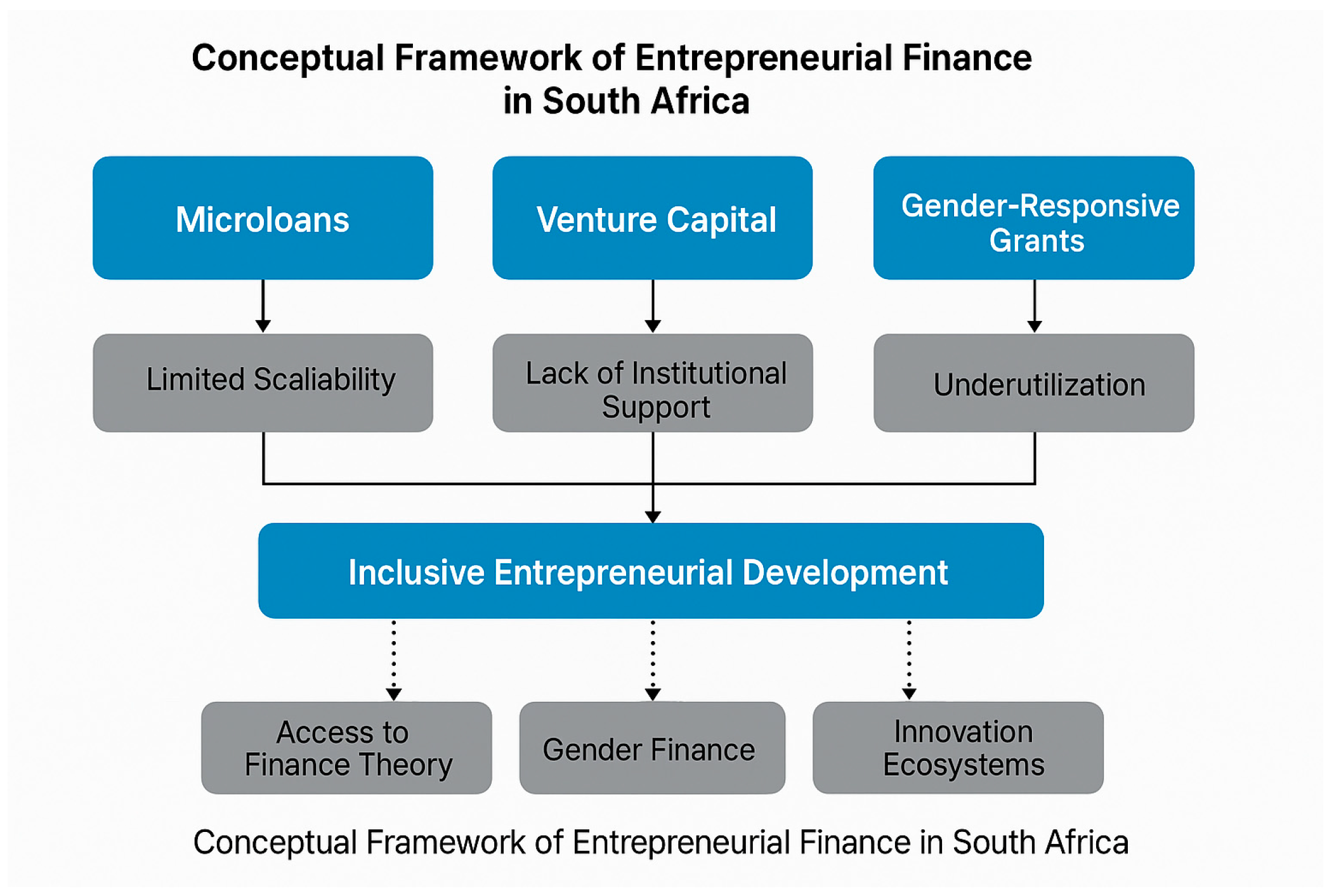

2.2. Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurial Finance in South Africa

Figure 1 below illustrates the conceptual framework that supports this study, linking financial instruments to systemic barriers and development outcomes through the perspectives of Access to Finance, Gender Finance, and Innovation Ecosystems Theories.

2.3. Review of Microloans in Emerging Markets

Evidence from developing countries indicates that microloans can significantly contribute to the short-term viability of small enterprises, especially by offering instant access to working capital that aids in covering operational expenses and handling cash flow variations. Nevertheless, the degree to which microloans foster sustained business expansion and enhanced productivity is still unclear and debated in scholarly discussions. For instance, thorough randomized controlled trials, like those carried out by

Banerjee et al. (

2015), show that although microloans frequently boost short-term household expenditure and business investments, they do not reliably lead to ongoing growth, increased profits, or enhanced productivity in the long run. These results emphasize the insufficiencies of credit solely in addressing the complex issues encountered by small-scale entrepreneurs, many of whom function in unstable and resource-limited settings.

In South Africa, programs such as the Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE) have integrated microfinance with educational elements addressing gender matters and HIV prevention, resulting in significant empowerment advantages for female participants. Although these integrated methods have enhanced participants’ confidence, decision-making abilities, and social standing, research such as

Hargreaves et al. (

2010) indicates that these positive social results have not reliably led to quantifiable income rises or sustained economic progress. In addition to these quantitative findings, a qualitative study conducted in rural areas (

Simatele & Maciko, 2022) highlights that entrepreneurs frequently gain from increased financial literacy, a deeper grasp of budgeting, and enhanced money management abilities acquired through microfinance initiatives. Nonetheless, these business owners persist in encountering systemic obstacles like restricted market access, insufficient infrastructure, and deep-rooted socio-economic disparities, which hinder the capacity of microloans to promote lasting business success. Together, this collection of evidence advocates for more comprehensive interventions that merge financial assistance with capacity enhancement, market connections, and policy changes to successfully foster sustainable entrepreneurship in developing economies.

2.4. Venture Capital: Influence and Limitations in South Africa

Venture capital plays an important role in fueling innovation and growth within companies by providing not only essential funding but also strategic guidance and valuable industry connections that can accelerate business development (

Mbhele, 2012). This form of financing is especially important for startups and high-growth small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that require significant capital injections to scale operations, invest in research and development, and enter new markets. However, despite its potential benefits, access to venture capital remains uneven across different segments of the South African business setting, with women-led SMEs facing particularly acute challenges. Quantitative research by

Shava (

2018) reveals a pronounced gender gap in venture capital allocation, which is partly attributed to differences in risk appetite and control preferences observed among women entrepreneurs. Women often exhibit a more cautious approach to risk and may prefer to retain greater control over their businesses, factors that can discourage venture capitalists who typically seek high-risk, high-reward investment opportunities with active involvement in management decisions.

Furthermore, venture capital in South Africa is mainly focused in urban areas and often neglects rural businesses and Black-owned enterprises, worsening the inequalities within the entrepreneurial landscape.

Herrington et al. (

2010) emphasize that geographic inequalities restrict the scope of venture capital firms, which typically favor investing in businesses situated in well-established economic centers where infrastructure, market accessibility, and business networks are more advanced. This city-centered emphasis results in numerous inventive rural entrepreneurs or individuals from historically marginalized communities encountering substantial obstacles in acquiring venture capital, even though they possess feasible business models and potential for growth. These geographic and demographic disparities highlight the need for more inclusive investment approaches and policy measures that can broaden the availability of venture capital, allowing a more diverse range of entrepreneurs to gain from the funding, guidance, and networking resources that venture capital offers. Tackling these issues is essential for promoting a reasonable and more vibrant entrepreneurial landscape in South Africa.

2.5. Gender-Responsive Grant-Making: Trends and Barriers

Studies that have undergone peer review emphasize both the potential and the constraints of gender-responsive grants in South Africa. Although these grants might alleviate early financial limitations, systemic and organizational hurdles continue. Women business owners must manage administrative inefficiencies, biased norms, and ingrained self-doubt (

Simatele & Kabange, 2022). Furthermore, although there are numerous state-sponsored and NGO-led efforts, their effectiveness is compromised by gaps in implementation and insufficient integration with wider business systems (

Dzomonda & Fatoki, 2017).

2.6. Gaps in the Existing Literature

A review of peer-reviewed research on business financing in South Africa reveals several critical gaps that warrant further investigation. First, while microloans have been widely studied, most analyses focus on short-term outcomes, with limited longitudinal evidence on their sustained impact on business growth, poverty alleviation, and economic resilience. Second, although gender disparities in access to venture capital are acknowledged, there is a lack of intersectional analysis that considers how race, geography, and industry sectors jointly shape financing outcomes. Third, research on gender-responsive grants often treats these instruments in isolation, failing to examine how they interact with broader financial institutions, ecosystem support services, and innovation infrastructure. Finally, few studies apply Innovation Ecosystems Theory to explore how financial tools integrate with non-financial support such as mentorship, training, and market access to drive entrepreneurial success. These gaps highlight the need for a more holistic and context-sensitive approach to studying SME financing in South Africa.

An analysis of scholarly research on business funding in South Africa uncovers significant gaps that require additional exploration. Although microloans have been extensively researched, the majority of studies emphasize short-term results, providing minimal long-term evidence regarding their enduring effects on business expansion, poverty reduction, and economic stability. Secondly, while it is recognized that there are gender differences in access to venture capital, there is an absence of intersectional analysis that examines how race, location, and industry sectors collectively influence funding results. Third, studies on gender-responsive grants typically consider these tools separately, neglecting to explore their interactions with larger financial entities, ecosystem support services, and innovation frameworks. Finally, limited research utilizes Innovation Ecosystems Theory to examine how financial instruments combine with non-financial assistance like mentorship, training, and market access to foster entrepreneurial achievement. These gaps emphasize the need for a more comprehensive and context-aware method for examining SME financing in South Africa.

3. Methodology

This study utilizes a qualitative desk study approach, suitable for its conceptual and policy-focused goals. The approach utilizes secondary data sources to analyze the entrepreneurial finance environment in South Africa, focusing on the design, accessibility, and institutional dynamics of microloans, venture capital, and gender-focused grants. This method provides interpretive understanding of institutional structures and policy tools without needing primary data gathering or econometric evaluation.

Data sources encompass publicly accessible policy reports, strategic documents, and analytical publications from major institutions like the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA), Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), and the Southern African Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (SAVCA). Peer-reviewed scholarly articles were included to guarantee conceptual and analytical precision. These sources were intentionally chosen for their relevance to the central themes of financial accessibility, equity, and systemic barriers.

A thematic content analysis was used to systematically recognize repeated patterns concerning financial inclusion, gender inequality, and institutional obstacles. This qualitative synthesis enabled the creation of a conceptually cohesive framework, connecting financial mechanisms to inclusive entrepreneurship development results.

A limitation of this method is that it depends solely on secondary documentary sources and does not integrate direct empirical insights from entrepreneurs or funding professionals. Although this design was appropriate for a conceptual policy analysis, it inevitably limits the understanding of the real-life experiences of entrepreneurs navigating through South Africa’s funding landscape. Therefore, the results indicate institutional and recorded viewpoints instead of actual conditions on the ground. Future studies might expand on this study through qualitative interviews, ethnographic methods, or case studies to confirm and enhance comprehension of the practical implementation and experiences of financial inclusion mechanisms.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Microloans: Access, Usage, Repayment, and Impact

Microloans act as an essential funding option for small business owners in South Africa, particularly for individuals in the informal sector lacking access to conventional financial services. Given the significance of microenterprises in sustaining household incomes and fostering local economic activities, microloans provide essential financial assistance for starting and maintaining business operations (

Chikadzi, 2022;

Fatoki, 2014). These financial offerings typically range from R500 to R250000, based on the lender and the borrower’s background, and are primarily administered by microfinance institutions (MFIs), the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA), and targeted initiatives like the Kuyasa Fund. Microloans are primarily utilized for acquiring inventory, obtaining equipment, and obtaining working capital to expand informal business activities. Microloans often feature flexible collateral requirements, rendering them particularly accessible for previously marginalized entrepreneurs, including women-led enterprises in rural and semi-urban areas (

Xaba, 2022). However, repayment results differ across borrower groups, with studies pointing out concerns such as high interest rates, payment failures, and borrowers’ limited capacity to expand operations sustainably (

Banerjee et al., 2015).

Empirical evidence indicates that although microloans significantly help with short-term income stabilization and promote the formalization of informal businesses, their long-term developmental effects are frequently restricted when given alone. Research conducted by

Rasel and Win (

2020) emphasizes that merely having access to credit does not ensure ongoing business growth or enhanced livelihoods, particularly for low-income entrepreneurs who might not possess the essential skills to successfully manage and expand their ventures. Often, microloan beneficiaries encounter difficulties like insufficient financial planning, a limited grasp of interest systems, and poor record maintenance, which may obstruct the effective use of funds and elevate the likelihood of defaulting on loans. To improve the success of microloan programs, there is increasing awareness of the need for supplementary measures, especially financial literacy education and improved market access. These initiatives provide entrepreneurs with the skills and resources to handle finances wisely, take informed business actions, and move through competitive landscapes. Moreover, incorporating mentorship structures into microfinance initiatives has demonstrated advantages in enhancing business outcomes. Mentors offer advice on strategic planning, operations, and innovation, aiding in better repayment rates and the long-term sustainability of businesses. The relationship between financial assistance and capacity-building programs fosters a more supportive environment for micro-entrepreneurs, particularly in neglected communities, and guarantees that microfinance fulfills its developmental goals beyond simply providing credit access.

4.2. Venture Capital: Funding Trends, Sectors, and Growth Trajectories

Venture capital (VC) acts as a crucial equity-financing approach aimed at promoting the growth of innovative, high-potential start-ups. Unlike microloans, venture capital consists of equity stakes rather than debt obligations, enabling investors to benefit from equity appreciation and intended exit strategies through acquisitions or IPOs (

Mason & Brown, 2014). In South Africa, venture capital plays a crucial role in fostering technological advancement, particularly in sectors such as fintech, agritech, and health-tech (

Metrick & Yasuda, 2011). The venture capital landscape in South Africa has experienced growth, with funding surpassing R1.5 billion in 2022, mainly concentrated in metropolitan areas like Cape Town and Johannesburg (

Metrick & Yasuda, 2011). Prominent VC firms such as Knife Capital, 4Di Capital, and Naspers Foundry have been instrumental in financing creative companies with flexible market solutions. These firms employ a staged investment strategy, typically comprising seed, Series A, and Series B rounds, aligned with milestones of the company.

Although there have been recent advancements in entrepreneurial finance, access to venture capital (VC) in South Africa continues to be highly unequal, with ongoing demographic differences and geographic concentration restricting the wider dissemination of its advantages.

Snyman and Kennon (

2014) indicate that venture capital is mainly focused in urban centers like Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban, which excludes numerous high-potential entrepreneurs based in semi-urban or rural locations. Furthermore, entrepreneurs from historically marginalized groups such as women, youth, and Black-owned enterprises frequently encounter systemic prejudices and lack the social capital or networks commonly esteemed in VC selection procedures. This exclusion is further strengthened by the strict entry hurdles characteristic of venture capital funding models, such as thorough due diligence demands, a preference for firms with established scalability, and the anticipation of considerable control rights by investors. Consequently, numerous early-stage and unconventional entrepreneurs are considered too risky or unfeasible, resulting in them lacking access to essential growth funding.

Nonetheless, the strategic importance of venture capital goes far beyond its monetary aspect. VC investment is crucial in bolstering South Africa’s innovation and start-up landscape by providing more than simply financial backing. Venture capitalists frequently offer mentorship and practical strategic advice that assists entrepreneurs in refining their business models, enhancing operational efficiency, and establishing strong governance frameworks. Additionally, VC firms act as conduits to important networks, allowing start-ups to establish strategic alliances, secure further funding, and access global markets. The blend of capital, expertise, and connectivity is crucial for creating globally competitive companies, especially in sectors driven by knowledge and technology. Therefore, although access to venture capital is currently restricted for many, broadening its availability through inclusive policies, focused incentives, and ecosystem development efforts could unleash considerable innovation potential and significantly help South Africa’s overall economic transformation.

4.3. Gender-Responsive Grants: Uptake and Gender Disparities

Gender-responsive grant programs addressing gender concerns are designed specifically to confront the rooted systemic obstacles faced by women entrepreneurs in South Africa, such as restricted asset ownership, limited access to formal financial services, and exclusion from entrepreneurial networks (

Sekantsi, 2019). These non-repayable funds serve as direct actions to tackle gender-based financial exclusion and promote women’s participation in the entrepreneurial sector. South Africa has launched various focused initiatives to improve financial access for female entrepreneurs, especially those in historically disadvantaged industries. A significant initiative is the Isivande Women’s Fund (IWF), overseen by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), providing up to R5 million in funding to enterprises owned by Black women, especially in the manufacturing and services industries (

Mandipaka, 2014). An additional significant program is the Women Entrepreneurs Fund (WEF), managed by the Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition (DTIC), which mainly assists women-owned enterprises involved in green economy industries and manufacturing (

Halkias et al., 2011).

In addition to domestic programs, international development initiatives often led by organizations such as United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], United States Agency for International Development [USAID], and the African Development Bank (AfDB) provide a blend of financial grants, technical assistance, and market integration support aimed at scaling up women’s participation in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. These programs collectively aim to address funding gaps, promote inclusivity, and strengthen the capacity of women entrepreneurs to contribute meaningfully to South Africa’s economic development. Although gender-responsive grants have a beneficial effect, they continue to be limited by inadequate institutional financial backing and dependence on sporadic donor assistance (

Gerasimenko & Zhou, 2023). Empirical evidence indicates that although these grants have effectively enabled women to enter entrepreneurial fields, their complete potential is restricted due to the lack of cohesive capacity-building initiatives and systemic financial backing from local institutions (

Lock & Lawton Smith, 2016). However, when well-organized, these grants greatly promote gender equality by enhancing women’s economic empowerment and aiding in community-level development results.

4.4. Digital Platforms as Catalysts for Inclusive Entrepreneurial Finance

Digital financial platforms are increasingly transforming entrepreneurial funding in South Africa, acting as innovative tools that circumvent conventional financial obstacles (

Kenney & Zysman, 2018). Mobile-based micro-lending apps (like Jumo), mobile wallets (such as M-Pesa), peer-to-peer loan networks, and AI-based credit scoring systems lower transaction expenses, speed up loan processing, and reduce dependence on traditional credit histories. These advancements are especially significant in rural and semi-urban regions, where business owners frequently do not have access to conventional banking services.

Mobile money platforms support both payments and the creation of transaction records, allowing micro-entrepreneurs to develop alternative credit histories. AI and big data analytics enable lenders to evaluate creditworthiness using behavioral and transactional information, granting access to previously marginalized groups like informal traders and women entrepreneurs. Additionally, digital crowdfunding platforms provide capital without equity, allowing entrepreneurs to completely avoid institutional gatekeepers (

Kenney & Zysman, 2018).

Nonetheless, adoption comes with its limitations. Digital literacy disparities, inconsistent internet availability, and inconsistent regulations obstruct the broad adoption of these platforms, particularly in less developed areas. Combining digital finance solutions with focused capacity-building initiatives such as digital skills training and financial literacy education would increase their effectiveness. Utilizing digital platforms presents significant transformative possibilities, not just in enhancing funding accessibility but also in allowing real-time data-driven business choices and promoting market integration for small-scale businesses.

4.5. Comparative Analysis

Every financing approach—microloans, venture capital, and grants tailored for gender—serves a unique but complementary function in fostering entrepreneurial growth, especially in developing regions such as South Africa. Microloans are essential, offering fast and easily accessible funding to informal and emerging entrepreneurs who frequently have no collateral or established credit backgrounds. These loans play a vital role in tackling urgent cash flow challenges, allowing entrepreneurs to acquire inventory, cover operational expenses, or invest in essential tools and infrastructure. Microloans can be crucial for women-owned and underserved businesses in moving from informal to semi-formal operations. Nonetheless, microloans by themselves might not adequately address more profound structural issues, like gender-related financial exclusion or restricted access to networks and markets. In this context, gender-responsive grants play an essential role by providing non-repayable funding that specifically addresses the distinct difficulties encountered by women entrepreneurs, including childcare responsibilities, insufficient collateral, and biased lending practices. These grants offer essential funding while promoting greater inclusivity by alleviating the financial strain on recipients and allowing them to pursue measured business risks.

Venture capital, on the other hand, enters the entrepreneurial finance spectrum at a later phase, focusing on companies that have already shown proof of concept, revenue growth, or potential for innovation. VC funding provides substantial capital as well as strategic assistance, such as mentoring, connections to markets, and governance supervision—essential elements that enhance business growth and innovation. The arrangement of these funding methods constructs a developmental hierarchy for entrepreneurs: microloans assist in the initial establishment of businesses and cash flow stability; gender-sensitive grants enhance operational structures and foster inclusivity; and venture capital enables significant growth paths and market growth. The combined funding ecosystem, highlighted by

Fatoki (

2014) and

Xaba (

2022), facilitates a more comprehensive approach to developing entrepreneurship. It promotes industry diversity by supporting companies at different development stages, boosts innovation by fostering scalable enterprises, and helps overall economic stability by allowing inclusive engagement in the formal economy. This collaboration among funding resources not only fills the financial voids at various phases of business development but also helps the overarching goal of sustainable and inclusive economic progress.

4.6. Interpretation of Key Findings

Analysis highlights the following several key insights:

Accessibility Compared to Scale: Microloans play a crucial role in ensuring widespread access to financial resources, especially for early-stage business owners and individuals working in the informal sector who frequently have no collateral or established credit histories. Their design generally emphasizes inclusivity and accessibility, enabling a diverse range of small business owners to obtain the modest funding necessary for daily operations or initial business ventures. Nonetheless, microloans usually do not have the scalability needed to facilitate quick business growth or significant innovation, since the loan sums are typically small and often inadequate for more considerable capital expenditures. On the other hand, venture capital investment aims to attain scale by providing significant financial resources to start-ups and rapidly growing companies with validated business models and considerable market opportunities. Although venture capital can elevate companies to greater levels of expansion and market presence, it remains very particular, frequently confined to a small group of start-ups that satisfy rigorous standards regarding scalability, innovation, and profit potential. This comparison highlights a significant disparity in funding for entrepreneurs: the broad availability of microloans contrasted with the focused, high-stakes nature of venture capital.

Gender Inequalities: Grants aimed at gender issues play a crucial role in tackling the widespread financial exclusion that women entrepreneurs experience, as they often face systemic obstacles like biased lending practices, insufficient collateral, and socio-cultural limitations that hinder their access to traditional funding channels. These grants offer essential equity-free funding that aids women-led businesses in overcoming early financial challenges without the pressure of repayment, thereby promoting entrepreneurship and empowerment. To achieve lasting and transformative results in gender-focused funding initiatives, it is crucial to implement gender-sensitive funding practices integrated within financial institutions and policy frameworks. This encompasses ongoing financial obligations, capacity-building initiatives designed for women entrepreneurs, and the establishment of monitoring and evaluation systems that guarantee accountability and the efficient use of resources. In the absence of ongoing assistance and structural changes, gender-focused grants may become isolated efforts with restricted lasting effects. An analysis of scholarly articles on business funding in South Africa uncovers significant gaps that need additional exploration. Although gender-related disparities are gaining recognition, the intersecting dynamics, especially regarding race, location, and industry, are still insufficiently examined. Many studies analyze gender independently, neglecting to account for how factors such as the entrepreneur’s race, their business’s geographic setting (e.g., rural versus urban), and the industry they engage in (e.g., informal services versus technology) also influence financial access. The absence of disaggregation hides crucial differences in access results and delays the ability of financial policy to address varied entrepreneurial requirements.

Systemic Integration: The most significant developmental effects in entrepreneurial finance arise when various funding mechanisms—microloans, grants, and equity investments—are not considered or utilized independently but are purposefully coordinated within cohesive institutional structures. This systemic integration entails merging financial products with supporting technical assistance services, such as business development help, mentorship, financial education training, and market access support. This comprehensive strategy acknowledges that entrepreneurs need more than mere funding; they require an encouraging environment that fosters their abilities, connections, and potential for growth. By incorporating diverse funding methods into a cohesive framework, organizations can establish smooth routes that assist entrepreneurs at various phases of business development, starting from initial start-up with microloans, progressing through operational enhancement with grants, and reaching expansion driven by venture capital. This integrated approach optimizes resource use, minimizes overlaps, and strengthens the sustainability of business initiatives, finally fostering wider economic development and inclusive progress.

Table 1 below shows the summary of financing instruments for entrepreneurs.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Summary of Key Insights

This study explored the different and supportive functions of microloans, venture capital, and gender-focused grants in tackling the financial difficulties encountered by entrepreneurs in South Africa. The results highlight that microloans continue to be an essential funding source for small and informal businesses, offering crucial operational capital that assists entrepreneurs in handling daily costs and launching their enterprises. These loans play a crucial role in serving underserved communities that frequently do not have access to conventional banking services. In contrast, venture capital serves as a crucial catalyst for the expansion and development of innovative-driven companies, particularly those within technology-heavy industries. Venture capital provides not just the significant funding required for growth but also strategic assistance and industry links that can drive companies into new markets. In the meantime, gender-responsive funding is essential for addressing the systemic obstacles encountered by women entrepreneurs, providing equity-free financial support aimed at creating equal opportunities. Nonetheless, despite their intended goals, these grants often face challenges like disjointed institutional backing, inadequate collaboration among stakeholders, and restricted domestic funding sources, all of which collectively diminish their potential effectiveness.

The main finding from this study indicates that, although each funding approach meets different entrepreneurial requirements, they frequently function independently instead of as part of a unified, cohesive entrepreneurial finance environment. This division hinders the complete utilization of their collective strengths, diminishing the overall impact of financial efforts designed to promote inclusive and sustainable business development. Without intentional efforts to synchronize microloans, venture capital, and gender-sensitive grants within a cohesive framework—one that includes diverse funding sources as well as complementary capacity-building and support services—the developmental impact of entrepreneurial finance is still limited. This study advocates for a comprehensive strategy that connects these funding sources, encouraging cooperation among public entities, private funders, and development organizations to establish a smoother and more supportive setting for entrepreneurs at every phase of their growth journeys.

5.2. Comparison with Prior Studies

The results of this study align with earlier studies, especially those conducted by

Fatoki (

2014) and

Snyman and Kennon (

2014), which highlight the divided character of entrepreneurial funding in South Africa. Additionally, the ongoing gender inequalities observed correspond with findings from

Nethengwe and Mnisi (

2024) and

Gerasimenko and Zhou (

2023), confirming ongoing obstacles to fair access to entrepreneurial funding based on gender. This study enhances current literature by highlighting the strategic significance of organizing financing tools, starting with microloans or grants and gradually moving to venture capital to enhance entrepreneurial success paths.

5.3. Challenges and Opportunities in the Financing Ecosystem

South Africa’s entrepreneurial finance environment encounters multiple systemic obstacles that impede fair access to funding. A key problem is the limited access to venture capital for new and emerging entrepreneurs, primarily because of investors’ reluctance to take risks and the implementation of strict selection criteria that benefit established companies with successful histories. This establishes considerable obstacles for innovative yet not tested startups, especially those headed by young businesspeople and women. Furthermore, the national financial framework does not adequately incorporate gender-sensitive funding mechanisms, leading to dependence on externally initiated programs instead of locally developed, institutionalized assistance. This gap restricts the sustainability and scalability of financing that is responsive to gender. Additionally, insufficient coordination among different financial instruments, from grants to equity financing, has resulted in policy fragmentation and duplicate initiatives, undermining the overall coherence and effectiveness of SME assistance. These systemic deficiencies emphasize the need for a more unified and inclusive financial structure that can effectively cater to the varied requirements of South Africa’s entrepreneurial community. The expansion of South Africa’s digital finance sector offers considerable chances to boost financial inclusion by improving access and simplifying application processes for microloans and grants. This digital transformation is enhanced by regional trade efforts, particularly the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which creates new market opportunities for entrepreneurs and bolsters business growth routes through localized funding options. At the same time, global development frameworks are increasingly advocating for blended finance models combining grants with concessional loans as a way to offer sustainable and scalable funding solutions for marginalized entrepreneurs, particularly focusing on supporting women-owned businesses.

5.4. Strategic and Policy Recommendations

5.4.1. Institutional Integration of Entrepreneurial Finance

Enhancing the effectiveness of entrepreneurial finance in South Africa demands the incorporation of microloans, equity financing, and grant-based tools within unified institutional frameworks. Crucial entities like the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA) and the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) should create cohesive operational structures that simplify application processes, normalize eligibility requirements, and enhance accountability systems. This integration ought to be directed by centralized regulatory supervision to minimize bureaucratic fragmentation and improve institutional transparency.

To improve access for historically marginalized groups, particularly Black women and young people in rural and informal settings, specific financing approaches need to be aligned with the National Integrated Small Enterprise Development (NISED) Masterplan. NISED highlights the distribution of support services and the creation of community-focused enterprise centers. Therefore, organizations such as SEFA and the National Youth Development Agency (NYDA) need to broaden their presence in historically neglected provinces, guaranteeing fairer access to funding.

5.4.2. Expanding Blended Finance Models

To tackle ongoing disparities in access to venture capital, especially for entrepreneurs in rural and semi-urban regions, public policy must focus on blended finance strategies that mitigate investment risks. Co-investment funds that blend public resources with private venture financing can mitigate risk and stimulate investments in unconventional areas and industries. This ought to be organized through development-focused special purpose vehicles (SPVs) that reduce investor risk while enhancing impact-driven results.

Moreover, performance-linked grants that transform into equity when verifying business milestones can assist in closing the divide between grant financing and conventional equity funding. This adaptable model facilitates scalable businesses while reducing dilution in the initial phases. These mechanisms need to be integrated into the NISED Masterplan and aligned with the Decadal Plan (2020–2030) from the Department of Science and Innovation to foster growth driven by innovation (

Ntsobi, 2024).

5.4.3. Operationalizing Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs)

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) should be utilized to link venture capital companies with entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups. These collaborations may involve shared investments in regional innovation hubs, especially in neglected provinces, where local administrations offer infrastructure and tax benefits, while private investors contribute capital, guidance, and network access.

Models like the Gauteng Digital Innovation Precinct offer scalable frameworks for nationwide replication, focusing particularly on enterprises led by women, youth, and Black entrepreneurs. Moreover, municipalities can integrate public procurement approaches that ensure market demand for SMEs arising from PPP-financed accelerators and incubators. These efforts will create inclusive ecosystems that integrate finance, capability, and demand throughout the SME lifecycle.

5.4.4. Enhancing Skills Training and Financial Literacy

Combining structured financial education and business development services within microfinance and grant initiatives is crucial for enhancing the efficiency of capital allocation. Key areas should encompass budgeting, credit oversight, strategic development, and digital competencies. Capacity-building efforts must be collaboratively created with NGOs, technical agencies, and business support groups.

When combined with mentorship and support after financing, these programs act as safeguards against loan defaults and business failures. Enhanced financial understanding and operational ability boost the absorptive capacity of entrepreneurs, making funding instruments more efficient and sustainable.

5.4.5. Leveraging Digital Financial Platforms

Digital financial technologies provide a scalable solution to enhance financial access for entrepreneurs who are underserved. Mobile lending applications (e.g., Jumo and Lulalend), blockchain-based grant distribution platforms, and AI-driven credit evaluation systems lower expenses, eliminate conventional collateral needs, and develop alternative credit records.

To enhance digital inclusion, authorities like the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) and the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) ought to widen regulatory sandboxes that evaluate and promote fintech innovations designed for informal entrepreneurs. Public–private partnerships can facilitate the use of these tools, especially in areas with inadequate physical banking infrastructure. Platforms supported by blockchain can enhance transparency, optimize loan monitoring, and enable data-informed credit assessment for informal merchants.

5.4.6. Promoting Digital Platform Ecosystems

A robust digital ecosystem is crucial for inclusive financing. Policymakers need to implement interoperability standards, regulations for consumer protection, and frameworks for digital identity to ensure secure and smooth platform use. Encouraging collaboration between the public and private sectors is essential to develop the necessary infrastructure and support digital literacy training—especially for women and young entrepreneurs.

These strategies must be in line with South Africa’s Digital Economy Master Plan and the digital transformation goals of NDP 2030, promoting a unified method for technological progress and inclusive finance. Monitoring and evaluation frameworks should incorporate indicators for digital financial inclusion and metrics for regional funding equity to effectively measure progress (

National Planning Commission, 2012).

5.4.7. Toward an Integrated Policy Framework

To enable scalable, inclusive entrepreneurial finance in South Africa, it is crucial to establish a cohesive policy framework that incorporates institutional integration, blended finance strategies, digital innovation, and cooperation between the public and private sectors. This type of ecosystem can methodically break down structural exclusion, support marginalized entrepreneurs, and encourage sustainable economic change.

5.5. Future Research Directions

Due to the exclusive dependence on secondary data in this study, upcoming studies should integrate primary qualitative approaches to gather authentic insights from entrepreneurs and financial participants. Performing semi-structured interviews, focus groups, or case studies with small business owners, financial institutions, and policymakers would provide context to the systemic and institutional insights outlined here. This would allow for a deeper comprehension of how financial tools function on the ground, particularly in rural, informal, and marginalized areas. Additionally, longitudinal studies could evaluate the developmental effects of integrated financing models over time, especially concerning their roles in poverty reduction, job creation, and the economic empowerment of women entrepreneurs in South Africa. Incorporating primary and secondary data through mixed-methods strategies would enhance upcoming analyses and foster more evidence-informed policy suggestions.