Abstract

Emotional labor, particularly in frontline service roles, has traditionally been examined through the lens of performance strategies, such as surface or deep acting. However, emerging research suggests that employees’ subjective interpretations of emotionally demanding situations—especially attributions of responsibility and perceived fairness—play a critical role in shaping their well-being. This study adopts a qualitative phenomenological approach to explore how frontline employees engage in meaning-making regarding the emotional labor demands during customer interaction. Drawing on six group semi-structured interviews, we conducted a thematic analysis to investigate ho<w workers attribute responsibility for emotion regulation demands and how these attributions relate to perceptions of distributive justice and emotional exhaustion. Results indicate that employees differentiate between emotional labor demands based on who they perceive as responsible for the triggering event—whether the client or themselves. Attributions of responsibility for these demands, especially when placed on clients, were associated with a stronger sense of distributive injustice and heightened emotional exhaustion. The evidence extend current emotional labor models by highlighting the centrality of meaning-making processes in employee experience and suggest that responsibility attribution and fairness appraisals are critical mechanisms through which emotional labor impacts occupational well-being. Implications for theory and workplace practices in service contexts are discussed.

1. Introduction

Service interactions refer to direct encounters between employees and customers during service delivery. In addition to cognitive (e.g., attention, decision-making) and behavioral (e.g., task execution, following procedures) components, these encounters also involve emotional aspects (Bitner, 1990; Grandey & Sayre, 2019). In this context, displaying kindness or suppressing negative emotions is a common organizational demand for frontline employees in most service-oriented organizations (Diefendorff & Gosserand, 2003; Fineman, 2001; G. Kim & Lee, 2014). These emotional demands are defined as explicit or implicit expectations regarding the employees’ expression (e.g., friendliness, patience) or suppression (e.g., frustration, annoyance) of emotions during service encounters (Bhave & Glomb, 2009; Diefendorff & Gosserand, 2003).

Building on these emotional demands, Hochschild (1983) introduced the concept of emotional labor, defined as “the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display” (p. 7) as part of the job role requirements. Emotional labor refers to the process through which employees regulate and manage their emotions to meet organizational emotional demands. These demands extend organizational control into the employees’ emotional domain.

The performance of emotional labor is intended to promote favorable customer experiences and enhance organizational outcomes (e.g., customer satisfaction, sales). It is a defining characteristic of service work (Barger & Grandey, 2006; Pugh, 2001). Despite emerging research questioning the efficacy of emotional labor in reliably producing such positive outcomes, its integration into service work practices continues to expand (Grandey & Sayre, 2019; L. Lee & Madera, 2019).

However, emotional labor has also been consistently linked to detrimental consequences for employee well-being (Hülsheger et al., 2010). A substantial body of research indicates that engaging in emotional labor is associated with a range of adverse psychological and physiological outcomes (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2013). Reported consequences include emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, self-estrangement, depressive symptoms, psychosomatic complaints, and feelings of alienation (Hülsheger et al., 2010).

The negative impact of emotional labor on employee well-being has been explained mainly through two well-established theoretical frameworks. The first is the self-control strength model, which proposes that the continuous effort to regulate emotional expression consumes limited psychological resources (Muraven et al., 2006). This depletion of resources can lead to emotional exhaustion over time. The second is the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., 2001). This model views emotional labor as a job demand that can cause strain—a short-term mental fatigue in response to job demands—if not balanced by adequate personal or organizational resources. When strain is prolonged or frequent, it may result in emotional exhaustion, similar to the first model. Emotional exhaustion is a lasting depletion of emotional and physical energy caused by prolonged exposure to stressors. It can impair emotional, cognitive, and physical functioning (Demerouti et al., 2002). In both models, the depletion of resources needed to regulate emotions in line with organizational emotional demands helps explain the negative effect of emotional labor on employee well-being.

According to both models, the amount of resources consumed by the emotional regulation strategies employees use to align their emotions with organizational emotional demands is a key factor in explaining the consequences of emotional labor. Whenever frontline employees experience emotional dissonance—that is, when their genuine feelings do not match the emotions required by the job—they must exert effort to display positive emotions, as prescribed by organizational norms such as “service with a smile” (Bakker et al., 2010; S. Kim & Wang, 2018). Consistent with this, research shows that surface acting—expressing an emotion different from one’s true feelings—consumes more psychological resources when sustained over time than deep acting—modifying one’s internal feelings to match emotional display rules—and therefore leads to greater emotional exhaustion. The greater impact on emotional exhaustion is therefore explained by how emotional labor is performed, regardless of the specific situation in which the strategy is applied (Grandey & Melloy, 2017; Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2012).

Although these models provide a parsimonious explanation of the relationship between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion, recent work highlights important limitations in focusing solely on how emotional labor is performed (Bindl et al., 2022; Grandey et al., 2015; Lavelle et al., 2023). These studies argue that considering only the amount of resources consumed by emotional regulation strategies overlooks numerous situational factors related to the conditions under which emotional labor is carried out. In this line, we propose that neglecting critical situational factors—such as the meaning that clients’ emotional demands hold for employees—can significantly influence the outcomes of emotional labor. Indeed, it seems reasonable to expect that the impact of surface acting in response to a customer requesting a product return may vary depending on whether the employee perceives the claim as unfair—such as when the product has been negligently used by the customer—or instead believes that the responsibility lies with them for having sold the wrong item.

From this perspective, employees’ interpretation of the responsibility behind the emotional demands arising from customer interactions and its impact on the perception of the service encounter as fair offers a more nuanced explanation of the consequences of emotional labor (Yagil, 2020; Yagil & Ben-Zur, 2009). Employees are more likely to perceive the emotional regulation demand as unfair when the customer is responsible for damaging the item. This perception is less common when the employee believes that the responsibility lies with them for having sold the wrong item (Weiner, 1995).

When situational factors are considered, it becomes clear that not all customer interactions are experienced equally, even when the same emotional regulation strategy is used. Consequently, the outcomes of, for instance, surface acting are not solely determined by the amount of effort required to display positive emotions while experiencing negative ones, but also by employees’ interpretations of why they are expected to engage in surface acting. In other words, employing the same emotional labor strategy may have different implications for well-being, depending on the perceived meaning behind the emotional display rules in a given situation.

Previous research on emotional labor has shown that employees’ attributions regarding the reasons for regulating their emotions mediate the impact of emotional labor on outcomes such as emotional exhaustion and feelings of inauthenticity (Crego et al., 2013; García-Romero & Martinez-Iñigo, 2021; Haybatollahi, 2009; Leggett & Silvester, 2003; Silvester et al., 2007; Yagil, 2020; Yagil & Ben-Zur, 2009).

Despite preliminary quantitative evidence, research has yet to explore how employees categorize customer interactions from a phenomenological perspective. Additionally, little is known about how these categorizations relate to employees’ experience of well-being at work. In this study, we ask: How do frontline employees’ attributions of client responsibility shape their justice evaluations of clients’ emotional demands, and with what consequences for employee well-being? To address this question, we conducted six semi-structured group interviews with 24 purposively sampled frontline customer service employees from diverse sectors and analyzed the data using a constructivist hybrid thematic approach that combined inductive and deductive coding. Results show that when employees attribute responsibility for emotionally demanding situations to clients, these demands are perceived as more distributively unjust, which amplifies emotional exhaustion; when responsibility is attributed to themselves or to their organization, perceived justice increases, attenuating emotional exhaustion. Theoretically, these findings extend the emotional labor theory by identifying the attribution–justice pathway as a mechanism that links situational meaning to employee well-being. Practically, the discoveries of this study suggest that employees’ subjective interpretations of clients’ emotional demands—in particular, their attributions of responsibility and perceptions of fairness—play a central role in shaping their emotional well-being. This implies the need for organizational policies and training that acknowledge that not all customer interactions are experienced equally, providing support and resources for navigating encounters perceived as unfair, and fostering climates that promote perceived justice to reduce emotional exhaustion and turnover. The remainder of this paper outlines the theoretical framework, details the methodology and analytic approach, presents the key findings, and concludes with implications for theory, practice, and future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Responsibility Attribution of Emotional Demands and Emotional Exhaustion

As Bindl et al. (2022) note, the reasons employees engage in emotion regulation at work—and how these reasons relate to their well-being—remain insufficiently understood. This gap is particularly significant from a qualitative standpoint as it leads to theoretical models of occupational stress (Lazarus, 1991; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Bakker and Demerouti (2007) emphasize the central role of individual appraisal processes in shaping how workplace demands are experienced. Yet, little is known about how employees themselves construct the meaning of such demands, or how these appraisals relate to their sense of fairness, responsibility, and emotional impact.

Building on these insights, the concept of meaning-making becomes crucial for understanding how employees interpret and respond to emotional demands at work. Meaning-making involves the mental construction or restoration of significance in response to stressful events, as described by Baumeister (1991), who defined meaning as a “mental representation of possible relationships among things, events, and relationships”, thus connecting disparate elements in a coherent framework. This process is especially important in challenging situations, where initial appraisals—often automatic and implicit—are continuously revised as individuals try to make sense of what the event means, including its controllability, threat level, causes, and implications for the future (Aldwin, 2007; Lazarus, 1991). Applying this to emotional labor, employees’ meaning-making about clients’ emotional demands involves attributing responsibility and fairness, which in turn influences how these demands are experienced, regulated, and linked to well-being outcomes.

From a transactional perspective on stress, workplace events—such as interactions with challenging clients—do not inherently lead to strain; rather, their impact on well-being emerges through employees’ subjective appraisals (Perrewé & Zellars, 1999). These appraisals are ongoing interpretive processes in which individuals try to understand what the event means to them, whether they have the resources to cope with it, and if they see the situation as controllable or threatening. Within this interpretive process, the attribution of responsibility for emotional demands emerges as particularly relevant, as it can profoundly shape how strain is not only experienced but also narrated by employees within specific organizational and relational contexts (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Mackey & Perrewé, 2014). These attributions influence how workers locate accountability, construct meaning regarding emotionally demanding situations, and ultimately affect their subjective experiences of injustice and well-being at work.

Within the framework of emotional labor, participants often described a dissonance between the emotional expressions required by organizational display rules (e.g., “service with a smile”) and their authentic emotional experiences. This tension was interpreted as a meaningful demand, closely tied to their perceived performance expectations. Initial interpretations of this mismatch—what Lazarus (1991) termed primary appraisal—appeared to occur rapidly and often outside conscious awareness. Subsequently, participants engaged in a secondary appraisal process, in which they constructed meaning about the situation by considering its source and reflecting on their ability to respond effectively. These appraisals shaped their emotional experiences and informed them how they navigated the strain associated with emotional dissonance (Mackey & Perrewé, 2014; Perrewé & Zellars, 1999).

Although quantitative evidence on the role of attribution in emotional labor remains limited, existing studies suggest that employees’ attributions regarding the reasons for regulating their emotions mediate the impact of emotional labor on outcomes such as emotional exhaustion, feelings of inauthenticity, and responses to customer behavior (Crego et al., 2013; García-Romero & Martinez-Iñigo, 2021; Haybatollahi, 2009; Leggett & Silvester, 2003; Silvester et al., 2007; Yagil, 2020; Yagil & Ben-Zur, 2009). Building on this foundation, we anticipate that attribution of responsibility will emerge as a central theme in how frontline employees categorize customer interactions, shaping their interpretation and responses to emotionally demanding situations during client encounters.

2.2. Responsibility Attribution of Emotional Demands and Social Exchange Conditions

Beyond the direct impact of responsibility attribution on employees’ well-being, our model underscores the crucial influence of the interpersonal context in which emotional labor takes place. As Grandey et al. (2015) propose, fully understanding the consequences of emotional labor at work requires attention to the interpersonal and organizational settings where emotional demands arise and are managed. Organizational justice is recognized as a key determinant influencing the outcomes experienced by individuals engaged in social exchange (Rupp et al., 2014; Schaufeli et al., 1996).

A substantial body of research highlights that employees’ perceptions of fairness are deeply shaped by how responsibility is attributed in social interactions. According to the fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano, 2001), the attribution of responsibility for an event is a sine qua non condition for assessing justice in the social-exchange process (Cohen, 1982). In this attribution process, individuals consider both the who and the why of the claimant’s situation, including whether the event could have been avoided (Weiner, 1982, 1995). When employees perceive that they are not responsible for an emotionally demanding task—such as when the customer is to blame for the problem—they are more likely to judge the task as unfair. On the other hand, when employees perceive that they are responsible for an emotionally demanding task, they tend to see the emotional demand as just.

According to our model, the evaluation of exchange conditions as unfair, derived from attributing responsibility to the customer, would negatively affect emotional exhaustion. Although it is beyond the scope of this study, this effect may be explained through the perception of emotional demands as illegitimate (Ding & Kuvaas, 2023; Semmer et al., 2015). That is, illegitimate emotional demands refer to those perceived by employees as unreasonable, unnecessary, or unfair expectations that exceed the accepted emotional role boundaries, thereby violating the normative standards of fairness in the workplace (Semmer et al., 2010). Illegitimate emotional labor is primarily a subjective and evaluative experience rooted in employees’ perceptions of responsibility attribution and distributive justice. When emotional demands are perceived as illegitimate, employees experience heightened feelings of injustice, which in turn amplify emotional strain and exhaustion.

Our research emphasizes the distributive dimension of justice, as numerous studies have shown that this aspect serves as a stronger predictor of a variety of workplace outcomes (Ghosh et al., 2014; Kalay, 2016), including emotional exhaustion (Cole et al., 2010; Hur et al., 2014; Kashif et al., 2017). When employees attribute responsibility for emotionally demanding tasks to others—especially clients—they tend to perceive an imbalance between the mental, emotional, and physical resources they invest and the recognition or rewards they receive, reflecting an effort–reward imbalance (Omansky et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2021). This imbalance is experienced as a form of distributive injustice, which intensifies emotional exhaustion (Rupp et al., 2007). Conversely, when employees perceive themselves as responsible for the demanding situation, the emotional effort invested is framed as necessary to restore service quality or repair trust (Horvath & Andrews, 2007; Rupp & Spencer, 2006; Spencer, 2005). In these cases, self-regulation effort is still present but aligns with expectations and perceived fairness, thereby mitigating feelings of distributive injustice which, in turn, reduce emotional exhaustion experience.

2.3. Social Exchange Conditions and Well-Being

A defining feature of emotional labor—unlike emotion regulation in other contexts—is that it “is sold for a wage and therefore has exchange value” (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7). Consequently, employees’ perceptions of these exchange conditions are indispensable for fully understanding their lived work experiences. Employees’ perceptions are the subjective interpretations that workers form regarding their job roles, the fairness of management practices, and expectations within the organization. These perceptions, involving evaluations about justice, support, and leadership (Colquitt, 2001; Lavelle et al., 2023; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). Given that emotional labor is fundamentally an interpersonal phenomenon, assessing social exchange conditions is crucial to capturing its complexity.

Within this framework, the principle of distributive justice states that individuals assess the fairness of social exchanges by comparing the ratio of their contributions (inputs) to the outcomes (outputs) relative to those of others (Adams, 1965; Colquitt, 2001; Homans, 1961). A key element of this evaluation, especially in emotionally demanding service roles, is the employees’ assessment of the resources invested (Milyavskaya et al., 2021; Milyavskaya & Inzlicht, 2017). This investment constitutes a core input that employees weigh when judging the distributive justice of a situation.

However, the significance of this investment is context-dependent: when employees perceive that the effort is justified because they accept responsibility for the demand, the effort is regarded as contributing positively to partner outcomes and restoring equity. This perception of distributive justice in effort mitigates negative effects on employee well-being. Conversely, when the emotional demand is attributed to others, the effort involved is seen as increasing employees’ investment unfairly, disrupting the social exchange balance against them. This heightened sense of distributive injustice amplifies the detrimental impact on well-being. Thus, whether effort is perceived as distributively fair or unfair clarifies how the attribution of responsibility for emotional labor influences employee outcomes.

Previous research on emotional labor has shown that perceiving clients’ behavior as interpersonally unfair is associated with poorer employee well-being (Cropanzano et al., 2003; Lavelle et al., 2023; Rupp et al., 2007, 2014; Rupp & Spencer, 2006). Among the various organizational justice dimensions, distributive justice has emerged as a particularly strong predictor of workplace well-being. However, there has been limited investigation into the other dimensions of organizational justice and their impact on workplace well-being. Martínez-Íñigo and Totterdell (2016) identified a mediating role for perceptions of distributive justice in the relationship between surface acting and emotional exhaustion among health professionals. García-Romero and Martinez-Iñigo (2021) also validated a mediational model of responsibility attributions and distributional justice of the effects of surface acting on emotional exhaustion.

If the comparison is proportional, individuals perceive the relationship to be equitable; however, if it is unfavorable, they perceive the situation as inequitable, leading to a sense of distributive injustice that threatens their well-being. Previous studies have shown that a sense of distributive injustice can contribute to emotional exhaustion, whereas fair interactions can reduce feelings of emotional exhaustion (Bernerth et al., 2011; Frenkel et al., 2012; Grandey et al., 2013; Gul et al., 2015; Matta et al., 2014; Tepper, 2001). This suggests that promoting justice in social exchanges can improve occupational well-being.

Thus, perceptions of responsibility attribution are core factors shaping employees’ appraisals of distributive justice and their well-being outcomes. Given the central role of responsibility attribution in the emotional labor experience—particularly in employees’ assessments of social exchange dynamics—this study investigates how these themes emerge in frontline employees’ narratives about client interactions. Specifically, we examine whether employees emphasize the attribution of responsibility for client behavior as a key factor when describing their interactions, and how assigning responsibility to themselves versus to clients relates to perceptions of distributive unfairness. Finally, we analyze how this attribution process connects to employee well-being outcomes.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach

Our study explores whether the attribution of responsibility for clients’ emotional demands and its relationship with the perception of the interaction as distributively unjust emerge as salient themes and patterns in frontline employees’ narratives about their everyday work experiences. Furthermore, we examine whether these elements are integrated into a broader pattern alongside employees’ expressions related to their occupational well-being. This is not a purely inductive exploration, as might be typical in approaches such as grounded theory, but rather a guided investigation informed by a pre-existing theoretical model for which some quantitative evidence is already available. The ultimate goal of this analysis is to assess the face validity of the findings derived from previous quantitative research. Given the hybrid nature of our approach—using a qualitative strategy to validate quantitative findings—a thematic analysis was selected as the most appropriate analytical strategy.

A thematic analysis strategy offers the theoretical and methodological flexibility needed to explore whether the themes and patterns emerging across our data aligned with a predefined model (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis has been characterized not as a specific method, but rather as an analytical technique that can be applied across a range of methodological frameworks (Boyatzis, 2010). Aligned with our research aim to move beyond surface-level descriptions, the thematic analysis was conducted from a constructivist epistemological perspective. This approach assumes that meanings and experiences are actively constructed by individuals in specific social contexts (Esin et al., 2014). This enabled us to engage in a latent thematic analysis, looking beyond the semantic content of participants’ accounts to identify and interpret the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualizations shaping their narratives (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Thus, our analysis focused not only on identifying explicit codes and patterns in participants’ accounts, but also on teasing out the deeper meaning-making processes underlying their narratives about emotional demands, responsibility attribution, and perceptions of fairness.

Finally, the choice of thematic analysis is particularly appropriate for our study, as it represents a contextualist method—capable of capturing how individuals construct meaning from their experiences, while also attending to the influence of broader social contexts on those meanings. At the same time, it maintains a focus on the material and structural constraints of “reality”—in this case, the organizational regulation of employees’ emotional expressions. In this way, thematic analysis functions as a method that both reflects participants lived realities and facilitates a critical examination of the surface meanings embedded within them (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

3.2. Participants and Settings

Group interviews were selected over individual interviews primarily to optimize resources such as time and logistical effort, while also leveraging their methodological strengths in exploring complex social phenomena (Edmiston, 1944; Frey & Fontana, 1991). The group format facilitated participant interaction, encouraging collective reflection and allowing the observation of how ideas, meanings, and experiences related to responsibility and justice are constructed, negotiated, and occasionally contested within a social context (Fontana & Frey, 2000; Gill & Baillie, 2018). This dynamic interaction provided unique insights into shared norms as well as individual divergences, thereby enriching the understanding of emotional labor as a socially situated process.

The use of six distinct groups supported thematic saturation, as no new relevant themes emerged after the final interview. Thematic saturation was considered achieved by the sixth group, as no new codes, themes, or subthemes emerged during the interviews. The appearance of novel themes was monitored continuously, and when the last groups yielded only redundant information that reinforced previously identified patterns, saturation was confirmed (Guest et al., 2006).

An external company was responsible for recruiting participants and scheduling meetings for the six group interviews (N = 24). A total of 24 frontline employees, including 13 men and 11 women, participated in this study. The groups were composed of participants from different work units to promote variability in their reasoning and reflections on the topic being discussed (S.-Y. Lee et al., 2020). Some participants’ demographic details and the composition of the groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Occupations of participants in each group interview and percentage of males.

In line with our approach to the study, our sampling process was both deliberate and iterative (Van Dijk & Kirk, 2007). Purposive sampling was used to ensure that only the customer service employees who routinely handled complaints and grievances were included. Before enrolment in this study, the participants were required to provide written consent. The research protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of the university to which the authors are affiliated.

The interviews were conducted between June and July 2022. Each session lasted approximately 90 min and was led by one of the authors, with a second author presenting as an observer. All interviews were audio-recorded and, subsequently, transcribed for analysis using Atlas.ti version 24. A semi-structured interview guide was employed to facilitate the discussion (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Key Interview questions.

To steer the conversation toward the central focus of this study while allowing participants’ own meaning-making to emerge, each interview began with a broad, open-ended question about what participants believed to be their organization’s main expectation regarding customer service. This approach was intended to elicit initial narratives without imposing predefined categories.

Customer satisfaction and the relevance of emotional labor were expected to emerge as salient themes. Once these topics surfaced and became established in the participants’ discourse, the interviewer introduced a second thematic block, inviting reflection on whether all customer interactions were experienced similarly, or whether meaningful differences could be identified across situations.

To encourage the emergence of classification criteria beyond those proposed in the analytical framework (i.e., responsibility attribution), the interviewer waited until the theme of interactional differences reached saturation. At that point, a third block was introduced, focusing on participants’ subjective experiences of emotional labor in situations where responsibility for the emotional demands was attributed either to themselves (e.g., a dissatisfied customer due to an employee’s error) or to the customer (e.g., an angry customer upset by a problem they themselves had caused).

The fourth and final block of the interview was introduced once participants began to describe emotional labor demands in terms of fairness—whether they perceived these demands as just or unjust. This emergent theme, anticipated in the design, served as a transition to the final section, in which participants were encouraged to reflect on how the previously discussed dynamics were related to their overall sense of well-being.

3.3. Analysis

Consistent with the adopted methodological approach, an iterative process was employed for both the coding of interview transcripts and the subsequent organization of data into themes and subthemes (Frazer et al., 2023). Coding followed a hybrid approach combining deductive and inductive elements: an initial coding frame was developed based on existing theory and prior findings, but codes were also allowed to emerge inductively from the data in line with Braun and Clarke (2006) guidelines for thematic analysis. These emergent themes enriched the analytical framework by illuminating critical contextual factors beyond the predefined categories, demonstrating the hybrid inductive-deductive nature of the coding process. This approach, alongside rigorous double coding and consensus discussions, reinforced the reliability and depth of the thematic analysis.

As a first step, each interview transcript was independently read and preliminarily coded by two researchers. To ensure reliability, discrepancies between coders were systematically identified and resolved through joint discussions aimed at reaching consensus. In instances where consensus could not be achieved, a third researcher was consulted to adjudicate and finalize coding decisions. Following this pre-analytical phase, the interviews were re-read and re-coded. During this second round, the researchers revisited the data to refine the identification of relevant excerpts and to further clarify the relationships among the emerging themes. The intercoder agreement, calculated using the Holsti index as implemented in Atlas.ti 24, was 97.1%.

Finally, Sangrey diagrams were developed to represent the range and nature of the participants’ experiences, facilitating the identification of patterns both within and across themes.

4. Results

To illuminate how frontline employees interpret and respond to emotionally demanding customer interactions, we present selected excerpts from group interviews. The following sections contextualize these voices within the broader themes identified in our analysis, organized according to the thematic blocks that structured the interviews. Where relevant, patterns observed across the different blocks are also highlighted.

4.1. Emotional Labor as a Core Job Demand

To ground our analysis, we first present participants’ perspectives on the centrality of emotional labor in frontline service roles. Across all groups, employees consistently described customer satisfaction as a core organizational expectation, closely tied to the requirement to regulate their emotional expressions. The following quotes illustrate how participants internalize these demands, highlighting the tension between authentic feelings and the professional demeanor required by their organizations. For example, when interviewers ask participants what their companies expect from them in their relationships with customers, they answer:

“In theory, our job is to provide good service and make sure the customer leaves satisfied.”

“The satisfaction of the customer or end consumer when asking for help or submitting an incident or a request for information.”

When the interviewer focused on the actions that allowed them to achieve the goal of satisfying the customer, the adjustment of behavior to a “service with a smile” norm emerged as a prominent element across the different groups:

“You always have to put on a smile for customers—even if, inside, you’re completely frustrated with them.”

“You have to keep smiling, even when a customer is insulting you, and stay composed. We’re all human, and sometimes it’s tough, but you have to put yourself in their shoes. After all, we’re customers too, as well as employees—you need to show empathy.”

4.2. Categorization of Employees—Clients Interactions Based on Responsibility

This section examines how frontline employees attribute responsibility during customer interactions, and how these attributions affect their well-being. Specifically, emotional exhaustion tends to be higher when responsibility is attributed to clients compared to when employees see themselves as responsible.

4.2.1. Categorization of Employees’ Interaction with Clients in Terms of Responsibility

During the group interviews, once emotional regulation was established as a key theme, participants were invited to reflect on whether the experience of performing emotional labor was always the same, or if distinct types of customer interactions could be identified. As anticipated, the attribution of responsibility for emotional demands consistently emerged as a central dimension that differentiated participants’ experiences across different groups. Employees described how the assignment of responsibility influenced their emotional responses and coping in service interactions. For example, one participant expressed the difficulty of being caught between recognizing a customer’s justifiable claim and organizational constraints:

“Often, the customer is completely right, but you can’t just give them what they want, and that puts you in a tough spot—you’re left wondering what you’re supposed to do.”

This statement shows that employees face a conflict: customers’ demands are seen as fair, but organizational policies restrict employees from fulfilling them, causing tension and uncertainty. Another participant highlighted the strain that emerges when company rules prevent meeting a customer’s fair request:

“The worst situations are when the customer is right, but company rules prevent you from helping. Then you have to try to explain things or shift the blame, even if it’s not fair.”

Here, employees are compelled to manage the emotional labor of maintaining professionalism while navigating perceived injustices, often having to deflect responsibility to protect themselves or the organization. Finally, participants reported instances where customers demand things they are not entitled to:

“Sometimes customers demand things they’re not entitled to, even though the rules are clear. But they just don’t want to accept it, so it’s really hard to get through to them.”

Together, these accounts highlight the central role of responsibility attribution in shaping employees’ experiences of emotional labor. How responsibility is assigned—whether to clients or oneself determines employees’ perceptions of fairness and the emotional burden they endure in service interactions. This aligns with attribution and fairness theories, which suggest that assigning responsibility affects both emotional and cognitive appraisals, as well as the perception of distributive (in)justice. In ambiguous or conflicting situations, particularly when responsibility is attributed to customers or organizational policies, employees are more likely to perceive demands as unfair, which heightens emotional exhaustion through increased cognitive dissonance. Hence, employees’ well-being is intimately linked not merely to the emotional demands themselves, but to the broader social and organizational contexts that define their fairness.

4.2.2. Responsibility Attribution and Well-Being

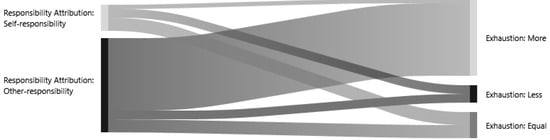

Regarding how emotional labor related to their well-being experiences, participants clearly associated that regulating their own emotions when addressing problems caused by the customer had a greater impact on their well-being compared to situations in which the employees themselves were responsible (see Figure 1). For example, when interviewers ask participants what types of interactions they find most emotionally draining, frontline employees report:

Figure 1.

Sankey diagram of co-occurrence analysis between responsibility attribution and emotional exhaustion.

“Me when it’s their fault [is more exhausted]. Because I get annoyed by the cheeky people. I mean, they have come to me with a microwave that has exploded because they put aluminum foil and they have tried to tell me that the microwave was defective. The microwave was two years old, had no ticket, no warranty and still the guy was two hours …”

“… you are insulting me, and you are insulting my intelligence because you are making me pretend to believe that you have now realized that … For me, the wear and tear of having that smile that you have the customer with all that education when what you want to say: Look, you are shameless.”

These accounts reveal how employees experience heightened emotional exhaustion when attributing responsibility to customers who create problematic situations and deny their fault. This supports our theoretical framework, which suggests that responsibility attribution influences the perception of emotional demands as distributively fair and the resulting emotional exhaustion.

4.2.3. Customer Power and Service Interactions

Beyond responsibility attribution, employees identified additional important criteria that shape how they categorize their interactions with customers. The most salient of these was the relative power customers hold within their relationship with the company. On one hand, customers are perceived as holding positions of strength—such as those generating significant revenue or possessing a large social media following—while on the other hand, some customers are viewed as vulnerable due to factors like advanced age, limited technological skills, or the necessity of critical medical services.

This dimension of customer power influences the degree of behavioral adjustment employees make, particularly in conforming to the organizational norm of “service with a smile”. When asked about the strategies they use to satisfy customers, participants consistently described tailoring their efforts according to customer status and needs. For instance:

“Young customers can usually sort things out on their own, but with older people, it’s much harder. I often end up helping them personally, even if it’s not really part of my job—I’ll look up information for them, call them back, whatever it takes.”

Another participant explained how customer categorization influences the type of service provided:

“In my case, the first thing we do is to see what type of user it is. A user who has the service for five days, who uses it sporadically, is not the same as an intense user, let’s say, who has thousands of trips or thousands of euros billed, yes? So, depending a little bit on the category, it is a little bit the solution we give.”

The impact of social influence is also reflected in comments about customers with a large social media presence or influential reputations:

“Sure, you review and there are people who have a lot of followers, they push you and they 120,000 followers or more …”

“If a person comes who may be very well known, who can give an opinion and that will affect the club, then in that case we must find a solution, no matter what.”

These examples illustrate how organizational and social hierarchies intersect with emotional labor demands, as employees adjust their emotional regulation and efforts depending on customers’ power and vulnerability. This dynamic shapes employees’ perceptions of responsibility and fairness in service interactions and modulates the emotional and cognitive effort required to manage them.

Overall, these findings underscore the necessity of considering contextual and relational factors—beyond responsibility attribution alone—to fully understand the variability in how emotional labor impacts employee well-being.

4.3. Responsibility Attribution and Distributive Justice

A recurring theme throughout the interviews was the strong link between responsibility attribution and perceptions of justice. Consistent with our theoretical framework, participants reported experiencing a greater sense of involvement in unfair interactions when they perceived that customers were responsible for the problem. For example, one employee described the frustration of dealing with customers who attempt to shift their responsibility onto the company, illustrating how such attributions challenge employees’ sense of fairness:

“I was working for [Spanish famous Department store] … if you went there with a half-eaten pork leg and you said it was salty, they gave you new ham. I defend what I consider to be fair, and then you have a moment to make the gentleman understand that if the ham was salty, the first slice you eat you know if it is salty or not.”

Similarly, another participant expressed the emotional burden that arises when customers disregard their own accountability:

“What they transmit to me is: Why do you turn your problem around and turn it into my problem? You know, when the one who has committed the infraction is you and the regulation … they know they have to buy a ticket, so what they cannot do is come here and pretend that your problem becomes mine and that I can solve it for them.”

These narratives highlight how employees perceive distributive injustice when customers are seen as unfairly offloading responsibility onto them, intensifying employees’ strain. This aligns well with the fairness theory, which posits that perceived inequity in exchanges—especially when caused by the other party’s actions—undermines well-being.

Conversely, when employees attributed responsibility to themselves, emotional labor was experienced more as a compensatory effort intended to restore fairness and repair the harm caused by mistakes. This shift in attribution reframes emotional labor as an active form of service recovery, influencing employees’ emotional engagement and perceived obligation. Below are some testimonials that reflect this idea:

“The problem is when he calls you and says: Hey, I went to take the test and they denied it because I talked to you and you said yes, that there was no problem, but when I got there they said no. Then you try to try to solve it. So, there you are trying to make an effort to try to solve it. I mean, oops, I’ve done it wrong, don’t worry, I’m going to check if the responsible is here to have it done right now because they call you from the hospital and you try to solve it and then you put more effort into it.”

“Because when the wrong has been committed consciously or unconsciously, you have to make up for it, you have to solve it, you have to provide customer service in both cases and it has to be a correct service because that is why you are attending the customer. But, obviously, when there has been a real problem and a mistake has been made, that is, you do not attend to it in the same way, it is not, that is, I think that voluntarily or involuntarily you get more involved, you want to solve it, than when … You say, mother of God, I have to show my face here and I have to explain whatever it is, but we know where we are starting from.”

These reflections underscore that perceived responsibility prompts differing emotional and behavioral responses, with employees more willing to invest effort when they or their organization are accountable. Finally, the narratives provide concrete examples of how distributive justice is practiced in daily service work, such as apologizing and offering compensation when errors affect customers:

“If a user has arrived late to work due to an incident that we may have caused in the service, obviously, of course, you have to … that is, well, first of all, apologize, but send the proof, you do not need to come, give me an e-mail, I will bring it to you, I will send it to you at the moment, to … assure me that you have received it, that is, until you have the proof, almost, you do not hang up the phone.”

Taken together, these accounts confirm the critical role of responsibility attribution as a precursor to fairness evaluations in customer interactions. When employees attribute responsibility for emotional demands, this attribution can trigger perceptions of distributive injustice regarding those demands. In turn, such perceptions contribute to increased emotional exhaustion, illustrating how responsibility attribution precedes and shapes fairness evaluations within customer interactions and emotional labor experiences.

4.3.1. Responsibility Attribution and Supervisory Support

Other aspects from the participants’ stories highlight the important role of perceived fairness and, especially, supervisory support in the relationship between responsibility attribution and employee well-being. Several employees shared feeling frustrated and discouraged when their supervisors overruled them by giving in to customers’ demands that the employees had already refused—and which the employees believed were unjustified. This lack of support from supervisors not only made employees feel treated unfairly but also increased their emotional exhaustion. These accounts reflect that, as noted in the literature, supervisory support can act as a key resource that helps employees recover from the strain of emotional labor and buffer the negative effects of distributive injustice (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Duke et al., 2009; Liao & Yan, 2014; Schaufeli et al., 1996). Consistent and fair managerial backing is, thus, essential for reducing the harmful consequences of emotionally demanding customer interactions and for sustaining frontline employees’ well-being. As one participant remembered from working at a well-known Spanish department store:

“Many years ago I was working for [Spanish famous Department store], if you went there with a half-eaten ham … and you said it was salty, they gave you a new ham. I say, I defend what I consider fair, and then you have a moment of, and try to understand the gentleman, look, if the ham was salty, the first slice you eat, you know that it is salty. But well, the customer at the [Spanish famous Department store] call the department head, the department head appeared: Give him a new ham or give him the credit note.”

Another participant described a similar experience:

“I think that he has prepared a lot of arguments, because when you go with a defective product, he says: try it yourself and I have nothing more to say, but of course, you have set up a whole paper and then it is a pick and shovel and until they do not have what they have gone to look for they do not let you go, because I was with that customer for 20 min, until he saw that with me he was not going to give and he said: we have already called the head of department and I already knew what was going to happen: at that moment the head arrived and said: give him the credit note and let him take a new one and that’s it.”

These narratives reveal how supervisory decisions that contradict employees’ judgments can exacerbate feelings of unfairness and emotional exhaustion, reinforcing the importance of supportive and consistent managerial practices in mitigating the negative impact of emotional labor. Such experiences were reported as demoralizing and emotionally draining, reinforcing the importance of organizational support and fair supervisory practices in mitigating the negative effects of emotional labor.

4.3.2. Responsibility Attribution and Invested Effort

In the same vein, employees’ invested effort further underscores the key role of perceived justice in shaping their experiences of emotional labor. As illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the co-occurrence analysis between responsibility attribution and invested effort, frontline employees’ willingness to dedicate energy and resources to attending customers was notably greater when they perceived themselves as responsible for the issue.

Figure 2.

Sankey diagram of co-occurrence analysis between responsibility attribution and invested effort.

Participants recounted instances where personal responsibility triggered heightened effort and engagement:

“There was an athletics championship […] and a mother with her children had booked and everything, but due to some mistake the reservation had been cancelled, and the hotel was full, that is, there was a championship, they were coming from all over Spain. And of course, the mother does not know what to do, she has no more, that is, she is lost, there is no more time. So, what we did as … as the issue involves children and children who, on top of that, have been preparing for a long time to play and so on and do that, that activity … What we did was to call around, trying to find all the hotels in Madrid and in the end, we found a solution, that is to say, we placed it … So, sometimes the situation is very sensitive, and you empathize and try to find …”

Others described the cognitive and emotional work required to repair a negative customer experience caused by a perceived mistake:

“If someone calls you with a problem that you think is your fault, whether it’s the company’s fault or because you have generated it, you put your brain on mode and try to find a solution or a way for the customer to at least not take away that bad experience from the call. To see the way, to put the interest in that, at the end, asking for forgiveness, doing whatever it takes so that, at the end, the call is, let’s say, satisfactory. And I think that is more tiring and you put more effort than with a person to whom I have told ten times that this article does not suit him, because he has not paid for it.”

These accounts illustrate the emotional demands that arise when employees perceive themselves or their organization as responsible for the problem. In such cases, workers invest significant emotional and cognitive effort to find solutions or to mitigate the negative experience for the customer. This extra effort reflects their commitment to restoring a sense of fairness and ensuring quality service. At the same time, it shows how the attribution of responsibility influences the meaning and intensity of employees’ emotional labor, shaping their willingness to engage in these demanding interactions.

5. Discussion

This study advances the understanding of emotional labor in frontline customer service roles by highlighting the nuanced relationship between emotional regulation demands and employees’ well-being. Consistent with prior research, emotional labor remains a core job requirement, where maintaining a positive demeanor, often described as delivering “service with a smile”, is expected regardless of the challenges posed by customer interactions. However, our findings provide novel insights into how employees’ appraisal of responsibility for service problems shapes the emotional and psychological costs associated with this labor.

Specifically, our findings confirm that responsibility attribution is a critical mechanism shaping employees’ perceptions of the fairness of emotional labor demands and consequent well-being outcomes. Emotional regulation in response to customer-caused problems tends to be more taxing, reflecting heightened frustration and perceived injustice. In contrast, when employees attribute responsibility to themselves or their organization, emotional labor is often framed as a reparative effort, involving increased perception of the effort invested to restore customer satisfaction and repair the relationship. This distinction aligns with cognitive appraisal theories, underscoring the importance of situational interpretation in shaping emotional experiences at work.

Furthermore, the results emphasize the role of customer power dynamics and vulnerability in modulating emotional labor. Employees adjust their emotional and practical responses based on the perceived status of the customer, with high-profile or high-value customers receiving prioritized, and often more resource-intensive, attention. Similarly, vulnerable customers elicit increased emotional investment, reflecting employees’ efforts to provide tailored solutions beyond formal company policies. This highlights how emotional labor is embedded in broader social and organizational contexts, shaped by both relational hierarchies and empathy-driven motivations.

This study also highlights the pivotal role of perceived justice in shaping employees’ experiences of emotional labor. When employees feel that their professional judgment is undermined by supervisors who concede to customers in ways perceived as unjust, this exacerbates their emotional exhaustion and diminishes their occupational well-being. Such perceptions of distributive injustice not only affect emotional labor outcomes but also reflect broader organizational dynamics that influence employee motivation and job satisfaction.

Building upon traditional and decontextualized models of emotional labor that primarily emphasize strategy deployment—such as surface versus deep acting—and the associated consumption of regulatory resources, our qualitative findings highlight the indispensable interpretative dimension. Specifically, they reveal how employees actively construct the fairness of emotional demands through attributions deeply embedded within the unique contextual and relational dynamics of their work. While well-established frameworks—including the self-control strength model (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000) and the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., 2001)—explain the detrimental effects of emotional labor largely in terms of depletion of psychological resources and imbalanced job demands, our study complements these by revealing that the subjective meaning employees assign to emotional demands critically shapes these processes. Specifically, attributions of responsibility, together with customer power asymmetries and organizational responses that frame fairness perceptions, influence how taxing emotional labor is experienced. This points to a necessary extension of traditional models, incorporating the temporal, social, and hierarchical embeddedness of attribution and meaning-making processes as key moderators of resource depletion and self-regulation outcomes.

5.1. Implications

The discoveries of this study suggest that employees’ subjective interpretations of clients’ emotional demands—in particular, their attributions of responsibility and perceptions of fairness—play a central role in shaping their emotional well-being. These insights have several broader implications for service organizations and researchers.

For practitioners, our results emphasize the need for organizational policies and training programs that acknowledge not all customer interactions are experienced equally by frontline employees. Organizations should provide support and resources enabling employees to navigate emotionally taxing encounters, especially those perceived as unfair. Interventions could include more flexible customer service guidelines, psychological safety measures, and conflict management training focused on fairness and attribution processes. Additionally, managers should recognize and address employees’ perceptions regarding who is responsible for emotional demands, as these perceptions influence feelings of distributive justice in the workplace. By doing so, organizations can promote a healthier climate that helps reduce emotional exhaustion and turnover.

5.2. Limitations

While this study offers novel insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. The qualitative analysis was limited to six groups, each composed of employees from related service sectors within a single region. This potentially restricts the generalizability of the results to other sectors or broader geographical contexts. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported perceptions may be susceptible to bias or selective memory. The cross-sectional nature of the data also prevents drawing firm conclusions about causality or long-term outcomes.

5.3. Future Research Directions

Future research should aim to replicate and extend these findings with larger and more diverse samples—including different service sectors, organizational settings, and cultural contexts—to test the generalizability of the identified patterns. Longitudinal studies could further examine how perceptions of responsibility and fairness develop and change over time, and how they impact emotional well-being in the long run. Quantitative methods could also be employed to systematically test the relationships suggested by our qualitative findings, such as those between responsibility attribution, perceptions of distributive justice, emotional regulation strategies, and well-being outcomes. Finally, future research could explore the distinction between objective and subjective effort as a promising avenue to deepen understanding of the mechanisms linking emotional labor to well-being. For example, examining how these dimensions may differentially contribute to employee outcomes over time could clarify how effort helps explain the relationship between distributive justice and exhaustion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-R. and D.M.-I.; methodology, A.G.-R., D.M.-I. and R.D.B.; validation, A.G.-R., D.M.-I. and R.D.B.; formal analysis, A.G.-R.; investigation, A.G.-R., D.M.-I. and R.D.B.; resources, A.G.-R., D.M.-I. and R.D.B.; data curation, A.G.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.-R. and D.M.-I.; writing—review and editing, A.G.-R., D.M.-I. and R.D.B.; visualization, A.G.-R.; supervision, D.M.-I.; project administration, D.M.-I.; funding acquisition, D.M.-I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through project PID2020-113539GB-I00 within the National Plan for Scientific Research, Development and Technological Innovation 2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee) of Rey Juan Carlos University (protocol code 2404201807018, 22 May 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable requests from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwin, C. (2007). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative approach. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In P. Y. Chen, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide: Vol. III (pp. 37–64). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B., van Veldhoven, M., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2010). Beyond the demand-control model: Thriving on high job demands and resources. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, P. B., & Grandey, A. A. (2006). Service with a smile and encounter satisfaction: Emotional contagion and appraisal mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. (1991). Meanings of life. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bernerth, J. B., Walker, H. J., Walter, F., & Hirschfeld, R. R. (2011). A study of workplace justice differences during times of change: It’s not all about me. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(3), 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, D. P., & Glomb, T. M. (2009). Emotional labour demands, wages and gender: A within-person, between-jobs study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(3), 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindl, U. K., Parker, S. K., Sonnentag, S., & Stride, C. B. (2022). Managing your feelings at work, for a reason: The role of individual motives in affect regulation for performance-related outcomes at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(7), 1251–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. E. (2010). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of «people work». Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R. L. (1982). Perceiving justice: An attributional perspective. In Equity and justice in social behavior (pp. 119–160). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M. S., Bernerth, J. B., Walter, F., & Holt, D. T. (2010). Organizational justice and individuals’ withdrawal: Unlocking the influence of emotional exhaustion. Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crego, A., Martínez-Iñigo, D., & Tschan, F. (2013). Moderating effects of attributions on the relationship between emotional dissonance and surface acting: A transactional approach to health care professionals’ emotion work. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(3), 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., Nachreiner, F., & Ebbinghaus, M. (2002). From mental strain to burnout. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(4), 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J. M., & Gosserand, R. H. (2003). Understanding the emotional labor process: A control theory perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(8), 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., & Kuvaas, B. (2023). Illegitimate tasks: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Work & Stress, 37(3), 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, A. B., Goodman, J. M., Treadway, D. C., & Breland, J. W. (2009). Perceived organizational support as a moderator of emotional labor/outcomes relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(5), 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmiston, V. (1944). The group interview. The Journal of Educational Research, 37(8), 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esin, C., Fathi, M., & Squire, C. (2014). Narrative analysis: The constructionist approach. In U. Flick (Ed.), Narrative analysis: The constructionist approach (Vol. 0, pp. 203–216). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman, S. (2001). Emotions and organizational control. In R. L. Payne, & C. Cooper (Eds.), Emotions at work: Theory, research and applications for management (pp. 219–240). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Folger, R., & Cropanzano, R. (2001). Fairness theory: Justice as accountability. In J. Greenberg, & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (Vol. 1, pp. 1–55). Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A., & Frey, J. H. (2000). The interview: From structured questions to negotiated text. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 645–672). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, I., Orr, C., & Thielking, M. (2023). Applying the framework method to qualitative psychological research: Methodological overview and worked example. Qualitative Psychology, 10(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S. J., Li, M., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2012). Management, organizational justice and emotional exhaustion among Chinese migrant workers: Evidence from two manufacturing firms. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50(1), 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, J. H., & Fontana, A. (1991). The group interview in social research. The Social Science Journal, 28(2), 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Romero, A., & Martinez-Iñigo, D. (2021). Validation of an attributional and distributive justice mediational model on the effects of surface acting on emotional exhaustion: An experimental study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P., Rai, A., & Sinha, A. (2014). Organizational justice and employee engagement: Exploring the linkage in public sector banks in India. Personnel Review, 43(4), 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P., & Baillie, J. (2018). Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: An update for the digital age. British Dental Journal, 225(7), 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A., Chi, N. W., & Diamond, J. A. (2013). Show me the money! Do financial rewards for performance enhance or undermine the satisfaction from emotional labor? Personnel Psychology, 66(3), 569–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A., & Melloy, R. C. (2017). The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A., Rupp, D., & Brice, W. N. (2015). Emotional labor threatens decent work: A proposal to eradicate emotional display rules. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 770–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A., & Sayre, G. M. (2019). Emotional labor: Regulating emotions for a wage. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, H., Rehman, Z., Usman, M., & Hussain, S. (2015). The effect of organizational justice on employee turnover intention with the mediating role of emotional exhaustion in the banking sector of Afghanistan. International Journal of Management Sciences, 5(4), 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Haybatollahi, S. M. (2009). Work stress in the nursing profession: An evaluation of organizational causal attribution [Ph.D. thesis, University of Helsinki]; p. 271. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/items/3ab00e07-85de-49d5-a879-ee7097b3a014 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms (p. 404). Harcourt; Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, M., & Andrews, S. B. (2007). The role of fairness perceptions and accountability attributions in predicting reactions to organizational events. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 141(2), 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W. M., Moon, T. W., & Han, S. J. (2014). The role of chronological age and work experience on emotional labor: The mediating effect of emotional intelligence. Career Development International, 19(7), 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U. R., Lang, J. W. B., & Maier, G. W. (2010). Emotional labor, strain, and performance: Testing reciprocal relationships in a longitudinal panel study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalay, F. (2016). The impact of organizational justice on employee performance: A survey in Turkey and Turkish context. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 6(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Rubenstein, A. L., Long, D. M., Odio, M. A., Buckman, B. R., Zhang, Y., & Halvorsen-Ganepola, M. D. K. (2013). A meta-analytic structural model of dispositonal affectivity and emotional labor. Personnel Psychology, 66(1), 47–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M., Zarkada, A., & Thurasamy, R. (2017). Customer aggression and organizational turnover among service employees: The moderating role of distributive justice and organizational pride. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1672–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G., & Lee, S. (2014). Women sales personnel’s emotion management: Do employee affectivity, job autonomy, and customer incivility affect emotional labor? Asian Women, 30(4), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Wang, J. (2018). The role of job demands–resources (JDR) between service workers’ emotional labor and burnout: New directions for labor policy at local government. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J. J., Rupp, D. E., Herda, D. N., & Lee, J. (2023). Customer injustice and service employees’ customer-oriented citizenship behavior: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44(3), 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press on Demand. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L., & Madera, J. M. (2019). A systematic literature review of emotional labor research from the hospitality and tourism literature. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(7), 2808–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y., Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Emotion regulation in service encounters: Are customer displays real? Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 30(2), 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, J., & Silvester, J. (2003). Care staff attributions for violent incidents involving male and female patients: A field study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(4), 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H., & Yan, A. (2014). The effects, moderators and mechanism of emotional labor. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(9), 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J. D., & Perrewé, P. L. (2014). The AAA (appraisals, attributions, adaptation) model of job stress: The critical role of self-regulation. Organizational Psychology Review, 4(3), 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Íñigo, D., & Totterdell, P. (2016). The mediating role of distributive justice perceptions in the relationship between emotion regulation and emotional exhaustion in healthcare workers. Work & Stress, 30(1), 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, F. K., Erol-Korkmaz, H. T., Johnson, R. E., & Biçaksiz, P. (2014). Significant work events and counterproductive work behavior: The role of fairness, emotions, and emotion regulation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 920–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., DeChurch, L. A., & Wax, A. (2012). Moving emotional labor beyond surface and deep acting. Organizational Psychology Review, 2(1), 6–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyavskaya, M., Galla, B. M., Inzlicht, M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2021). More effort, less fatigue: The role of interest in increasing effort and reducing mental fatigue. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 755858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milyavskaya, M., & Inzlicht, M. (2017). What’s so great about self-control? Examining the importance of effortful self-control and temptation in predicting real-life depletion and goal attainment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(6), 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraven, M., Shmueli, D., & Burkley, E. (2006). Conserving self-control strength. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(3), 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omansky, R., Eatough, E. M., & Fila, M. J. (2016). Illegitimate tasks as an impediment to job satisfaction and intrinsic motivation: Moderated mediation effects of gender and effort-reward imbalance. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrewé, P. L., & Zellars, K. L. (1999). An examination of attributions and emotions in the transactional approach to the organizational stress process. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(5), 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, S. D. (2001). Service with a smile: Emotional contagion in the service encounter. The Academy of Management Journal, 44(5), 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D. E., McCance, A. S., & Grandey, A. (2007). A cognitive-emotional theory of customer injustice and emotional labor. In D. DeCremer (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of justice and affect (pp. 199–226). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Jones, K. S., & Liao, H. (2014). The utility of a multifoci approach to the study of organizational justice: A meta-analytic investigation into the consideration of normative rules, moral accountability, bandwidth-fidelity, and social exchange. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 123(2), 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D. E., & Spencer, S. (2006). When customers lash out: The effects of customer interactional injustice on emotional labor and the mediating role of discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Van Dierendonck, D., & Van Gorp, K. (1996). Burnout and reciprocity: Towards a dual-level social exchange model. Work & Stress, 10(3), 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N. K., Jacobshagen, N., Meier, L. L., Elfering, A., Beehr, T. A., Kälin, W., & Tschan, F. (2015). Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work & Stress, 29(1), 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N. K., Tschan, F., Meier, L. L., Facchin, S., & Jacobshagen, N. (2010). Illegitimate tasks and counterproductive work behavior. Applied Psychology, 59(1), 70–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J., Patterson, F., Koczwara, A., & Ferguson, E. (2007). «Trust me…»: Psychological and behavioral predictors of perceived physician empathy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, S. (2005). The influence of social comparisons of interactional justice on emotional labor: An extension of fairness, affective events, and emotional regulation theories [Ph.D. thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available online: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/82098 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Tepper, B. J. (2001). Health consequences of organizational injustice: Tests of main and interactive effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]