1. Introduction

Studying the behavior of leaders has been a frequent topic of interest throughout history and the main focus of institutions in various business groups (

Jung et al., 2021). Taking into account the definitions of leaders by

Podgorniak-Krzykacz (

2021) as a “caretaker”, “consensus facilitator”, “boss of the town” and “visionary”, it is then essential to analyze how these typologies influence decision making, organizational performance and impact on collaborators. This skill is used to build trust between the leader and team members (

Baykal et al., 2018). As history tells it, leadership has existed since ancient times; that is, since the time of the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Babylonians, among other great civilizations (

Díaz, 2023). All of these civilizations had a leader, took over large crowds, presided over the government of a nation, controlled wars and promoted collective ideas, being highly educated in the practice of this skill (

Díaz, 2023;

Sözen & Şar, 2015). And as a response to economic, social, cultural, political, and technological changes, the study of leadership should be viewed with special importance, since its impact is related to the behavior of people and their influence on the achievement of the objectives of an organization (

Meirinhos et al., 2023).

A leader is seen as the heart of an organization and cannot be underestimated (

Al-Mahayreh et al., 2016). Leadership is recognized by spreading ideas, thoughts, or actions. According to

Covey (

1994) a leader is one who solves problems in creative ways to achieve sustainable success. Researchers have demonstrated and proposed various forms of leadership (

Amini et al., 2019), and with its evolution, renowned authors such as James Burns, Bernard Bass, and Steven Covey, among others, have contributed to the study of leadership styles, (

Palafox et al., 2020); each style has methods or patterns of behavior that the leader ought to adopt in order to manage his or her organization effectively (

Van Jaarsveld et al., 2019). It is important to note that different leadership styles seem to work for most leaders in various situations, leading to the claim that there is no best leadership style and that the most successful leaders tend to adopt most of the different styles (

Espejo-Pereda et al., 2025;

Laura-Arias et al., 2024;

Mooroŝi & Bantwini, 2016;

Van Jaarsveld et al., 2019).

Entities seeking to achieve high levels of effectiveness must proactively adjust to environmental transformations (

Ramos et al., 2020). The ability to predict threats, confront adverse situations and adapt to changing circumstances is fundamental to their survival and success. In the present context, marked by continuous innovation, non-profit institutions also need to develop digital skills that will enable them to progress in their digital maturity. To address these challenges, it is essential to employ strategies such as education, effective communication, and active participation of employees in the transformation process, and this is where establishing a learning culture could generate significant changes (

Martínez et al., 2020). Constant technological changes have made organizations aware of the competitive markets in which they operate, and which motivate them to seek a competitive advantage in learning and knowledge (

Gil et al., 2023;

Torgaloz et al., 2023). Organizations can maintain a competitive advantage and be innovative as long as they choose to seek more knowledge and know how to manage it effectively (

Ramos et al., 2020;

Udin, 2023). A learning-oriented culture aims to create an organizational environment that focuses on the collaboration between individuals and on stimulating creative processes. The organizational structure should support the sharing of knowledge (

Gonzalez & Massaroli, 2017;

Porcu et al., 2020;

Yang, 2003). The organizational structure is responsible for determining the clear formalization of knowledge, the degree of autonomy of employees, connecting people, promoting multidisciplinary and communication channels between individuals, and utilizing the flow of knowledge (

Gedifew & Muluneh, 2022;

Maggi-da-silva et al., 2022).

For this reason, the learning culture plays an important role in the process of adaptation to a changing environment (

Gedifew & Muluneh, 2022;

Gil et al., 2023;

Troskie-de Bruin et al., 2014). In the 21st century, companies operate in increasingly uncertain contexts (

Atanassova & Bednar, 2022;

Kelling et al., 2021;

Silva & Ferreira, 2017), and they should learn faster and better, as this guarantees sustainability (

Torgaloz et al., 2023). Additionally, maintaining a learning culture could optimize management skills, resulting in a good business performance (

Cegarra-Navarro et al., 2021). A learning culture encourages experimentation and critical thinking (

Barabasch & Keller, 2020). When employees feel it is safe to try new ideas and learn from their mistakes, organizations become innovative and can quickly adapt to industry changes (

Jung et al., 2021;

Porcu et al., 2020). Hence, organizations that value and foster a culture of lifelong learning will achieve better results (

Raemy et al., 2023), since their employees, who are constantly acquiring new knowledge and skills, can better perform their functions and contribute to the overall success of the institution (

Cavazotte et al., 2015).

Nonprofit organizations (NPOs) are a type of organization whose main purpose is not to generate economic profit, but to fulfill a social, cultural, educational, humanitarian, or community mission (

Bernstein & Fredette, 2024;

Hodges & Howieson, 2017;

Tosto & Tcherni-Buzzeo, 2025). This sector is undergoing a profound transformation due to environmental, social, political and economic changes in Europe and Latin America (

Hodges & Howieson, 2017). An emphasis on leadership styles has influenced conversations about management and the general perception of leadership within NPOs (

Shier & Handy, 2020). In this sense, it has been observed that the leadership style exercised in certain NPOs, such as religious organizations, is critical to their long-term survival, and this is one of the most widely researched topics, due to its impact on behavior (

Ortiz-Gómez et al., 2020). This suggests that the success or failure of a NPO development project largely rests with its leaders. There is a growing recognition of importance in the context of NPOs (

Aboramadan & Kundi, 2020). Therefore, those in leadership positions at all hierarchical levels should take the necessary precautions to increase the commitment of their members (

Erdurmazlı, 2019). While leadership in NPOs presents similarities with that of the business sector, it also faces challenges with volunteer management, donations, limited resources, generally lower remuneration, and competition with other sectors seeking talent (

Nave & Correia, 2020;

Potluka et al., 2021). It has been shown that leadership in this sector varies according to the culture in which it operates. In addition, the scarcity of scientific research and the complexity of the environment make it necessary to analyze the nature of leadership and to identify the characteristics that favor the success of the sector in relation to the cultural context in which these entities operate (

Brunetto et al., 2024;

Debnath & Bhowmik, 2022).

Taking into account this background, a diligent review of literature has shown the evident emergence of a growing interest in studying these topics among the leaders of human and academic talent management. Bibliometric indicators reveal that the ten countries that most frequently disclose their scientific results are the United States, China, the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Indonesia, Australia, India, Pakistan, Canada, and Spain. These countries have applied their studies to various areas, sectors and populations, such as business management and accounting, social sciences, psychology, economics, and engineering.

However, in relation to the scientific dissemination of these three topics, no existing studies have been found that allow a more comprehensive scope of leadership behavior, even though evidence supports the idea that studying aspects of leadership and learning culture could not only increase the effectiveness of employee performance but also transform an organization into an agent of continuous learning (

Udin, 2023). In fact, there is little research assessing the dynamic capacity of an organization, which could establish both objective and subjective conditions to support the process of innovative development (

Santos et al., 2022). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyze whether leadership styles influence learning culture and dynamic capacity. The text below comprises the following sections:

Section 2 contains the literature review and hypothesis development.

Section 3 provides materials and methods.

Section 4 describes the results.

Section 5 contains the discussion and

Section 6 focuses on the conclusions.

5. Discussion

The objective of the present study was to analyze whether or not leadership styles influence learning culture and dynamic capacity. This study was developed in the context of nonprofit organizations at the Latin American level, a sector that is undergoing a major transformation as a result of the environmental, social, political and economic changes taking place in Europe and Latin America (

Hodges & Howieson, 2017). In the early 1950s, leadership studies emphasized behavioral patterns and leadership styles (

Schmid, 2006), focusing on the importance of leaders understanding the various models they can follow, as well as developing skills to identify their own strengths and weaknesses (

Schmid, 2006), creating positive emotions, and preventing negative emotions in group members (

Rowold & Rohmann, 2009). This is especially relevant in the field of nonprofit community and human service organizations, which face continuous change and transition (

Lutz Allen et al., 2013), particularly due to the declining legitimacy of the welfare state (

Schmid, 2006). Therefore, the leadership style exercised in certain organizations, such as religious ones, has been recognized as critical, and therefore is one of the most widely researched topics, due to its impact on behavior (

Ortiz-Gómez et al., 2020). This sector is commonly characterized by volunteer management, donations, limited resources, typically lower remuneration, and competition with other sectors in the search for new talent (

Nave & Correia, 2020;

Potluka et al., 2021). Recent studies show that leadership within this sector differs, depending on the culture in which it operates (

Brunetto et al., 2024;

Potluka et al., 2021).

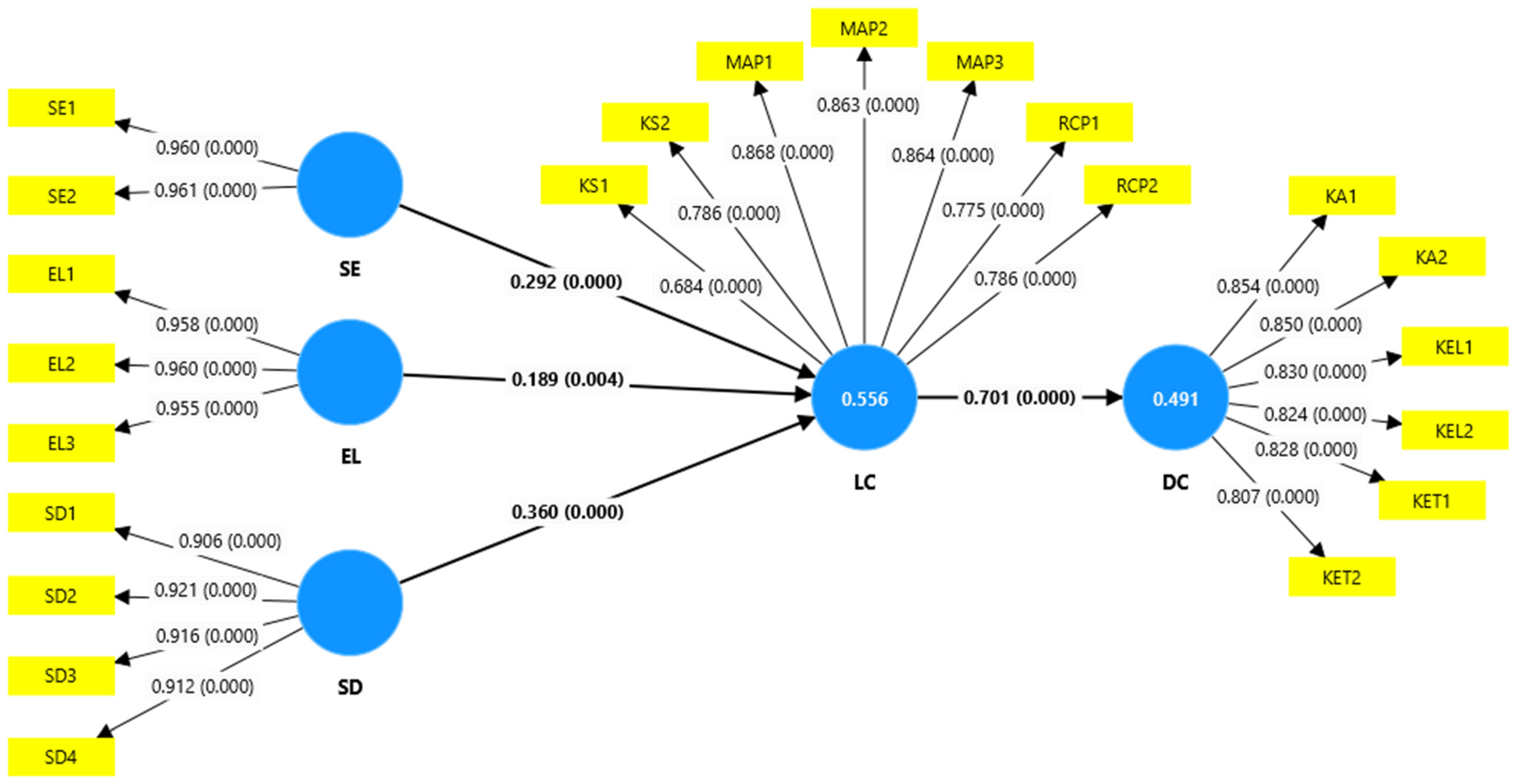

From a descriptive perspective of the results and statistical analysis, this research analyzes the evaluation of the measurement model, which indicated high levels of reliability of the constructs evaluated, which is essential to guarantee the validity of the conclusions. Cronbach’s Alpha values obtained scores greater than 0.70, indicating solid internal consistency. Likewise, the composite reliability (CR) also exceeded the minimum valid scores, showing that the indicators of each construct adequately reflect the theoretical concept that it intended to measure. In that sense, the fact that Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability have had values higher than the minimum threshold establish the reliability of the construct to continue the process of testing the structural model. Two criteria were used to determine discriminant validity: the Fornell–Larker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT). In both cases the values obtained showed a robust model.

To verify the hypotheses, the PLS-SEM technique was used. The path coefficient values,

p-value, and t-statistics were used to accept and reject the hypotheses. In the case of H1, it was accepted that servant leadership (SE) had a positive impact on the learning culture (LC).

Dalain’s (

2023) study agrees with the results of this research by showing that servant leadership in association with other variables, such as goal congruence and human talent practices, regulates innovation where learning culture plays an important role (

Gonzalez, 2024). Likewise, by accepting H2, agreement is suggested with what was reported in the study by

Babaee et al. (

2021), who found a close association between empowering leadership and learning culture. In addition, this study accepted H3, which highlights the importance of shared leadership in promoting a learning-oriented organizational culture, which is essential to encourage continuous innovation and adaptation in an organizational environment.

The acceptance of H4 reinforces the idea that a strong learning culture is valued for the development of dynamic capabilities, which is a strategic path for organizations that wish to adapt quickly to changes in the environment through continuous improvement of their critical processes. These results are similar to the scientific dissemination of some recent studies (

Gonzalez, 2022;

Gonzalez & Massaroli, 2017). On the other hand, the acceptance of H5 suggests that servant leadership can foster dynamic capabilities in nonprofit organizations, mainly when it fosters the formation of a learning culture. This suggests a similarity with some scientific reports from Vietnam and other case studies (

Irani et al., 2009;

Hanh & Choi, 2019). H6, which was accepted, indicates a significant relationship, although more modest compared to the other leadership models. Finally, accepting H7 highlights the importance of shared leadership, not only in directly promoting a culture of learning, but also in its ability to translate this culture into dynamic capabilities (

Gonzalez, 2022).

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study presents various theoretical and practical implications for the practice of NGO management in Latin American contexts. At a theoretical level, it expands knowledge about the behavior of NGO leaders in Latin America and how it influences the learning culture and dynamic capabilities of these organizations, providing literary support for the confirmed hypotheses. The aforementioned theoretical considerations highlight and reaffirm that leadership is an essential component for the development of dynamic capabilities, demonstrating that it is a dimension whose orientation is related to strengthening the competencies of organizational members for their transformation processes and for the fulfillment of organizational objectives and goals. In this sense, considering leadership as a key component that impacts the learning culture and dynamic capabilities of an NGO is a proposal that adds value to research on this topic.

One of the least discussed, yet most relevant, aspects in the field of leadership is that numerous researchers have analyzed it, often without considering its specific context. Social identity theory suggests that the way leadership is exercised is based on self-perception in relation to one’s social group and collective identity. Thus, the economic, political, and sociocultural environment of Latin America may have affected the manifestation of these attributes among leaders. In this sense, a shift from hierarchical models to horizontal, participatory, and community-based leadership may be more appropriate and effective for NGO settings. Currently, NGOs face challenges such as limited donor funding, volunteer recruitment, and, to a certain extent, the socioeconomic situation in some countries in the region. At the same time, they must assume the responsibility of supporting vulnerable populations living in poverty. Considering this, it is believed that shared, empowered, and servant leadership could counteract these challenges by building trust, ethical alliances, and mobilizing local resources. These types of leadership can also purposefully attract new volunteers, forming genuine human bonds, and may also be capable of promoting emotional resilience, adaptability, and social justice, fostering solutions rooted in dignity and active participation.

On the other hand, leadership is a process that helps and encourages other organizational components to be intensely astute, innovative, collaborative, and transformative, providing organizations with skills to achieve greater managerial effectiveness. In this sense, the results of this study contribute to the strategic field by showing the benefits of promoting servant, empowering, and shared leadership in the pursuit of social added value. From the perspective of organizational practice, these data are important because, in the current context of Latin American NGOs, where the decline in international cooperation funds and high competition for access to resources for the execution of social projects predominate, this forces them to make internal adaptations. The adoption of differentiating, tangible and intangible practices to continue offering their humanitarian aid, being sustainable in the long term, and developing impact capacity are the constant challenges these institutions face. In this sense, this research is of interest to human resources professionals in order to promote the roles of servant, empowering, and shared leadership within their work teams. Investing in the training of effective leaders would develop and strengthen a learning culture and increase the dynamic capabilities of NGOs to achieve organizational sustainability and continue to fulfill their institutional mission.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

One of the possible limitations of this study is that we used a convenience sample. Despite this, the sample used included different work teams based in different Latin American countries that, in turn, belonged to different organizational and economic realities. Future studies should be aimed at unraveling causal pathways through longitudinal techniques. The use of multilevel methodology is recommended to explore longitudinal studies where the level of the organization and lower-level variables are related, such as human resources, where it would be interesting to explore the differences in perceptions between supervisors and employees regarding servant, empowering and shared leadership.

6. Conclusions

Leadership has been a key element in work environments, contributing to the construction of more competitive and efficient institutions. Its impact transcends different sectors, including non-profit organizations, where it is essential to improve management and achieve institutional objectives. Furthermore, organizations that want to be effective must adapt to certain changes that will take them to where they want to be, and this is where a true learning culture must be built. A learning-oriented culture aims to create an organizational environment that focuses on collaboration between individuals and stimulates creative processes. Additionally, the organizational structure should support knowledge sharing. In this context, this research aimed to analyze whether leadership styles influence learning culture and dynamic capacity.

To address the main objective of the research, an explanatory study was carried out considering 300 workers from nine Latin American countries who declared that they carried out work activities in a non-profit institution, aged between 19 and 68 years (M = 34.10 and SD = 8.88), all whom were recruited through non-probabilistic convenience sampling. The theoretical model was evaluated using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM). A measurement model with adequate fit was obtained (α = between 0.909 and 0.955; CR = between 0.912 and 0.956; AVE = 0.650 and 0.923). Based on the results, a positive impact of servant leadership on the learning culture (β = 0.292), of empowering leadership on the learning culture (β = 0.189), of shared leadership on the learning culture (β = 0.360), and the culture of learning on dynamic capacity (β = 0.701) was demonstrated.

The findings of this study highlight the critical role that leadership plays in fostering a culture of learning within nonprofit institutions, ultimately enhancing their dynamic capabilities. Given the specific challenges faced by nonprofit institutions, such as volunteer management, donations, limited resources, generally lower compensation, competition with other sectors seeking talent, and the need for sustained social impact, leadership styles that prioritize collaboration, empowerment, and service-oriented values allow a pathway to success for institutions in the sector.

Servant leadership fosters a people-centered approach that nurtures trust and commitment, while empowered leadership enhances autonomy and decision-making, both of which are essential for adapting to changing environments. Additionally, shared leadership promotes collective responsibility and reinforces the cooperative nature of non-profit work. Furthermore, a robust learning culture in these contexts not only enhances internal knowledge sharing, but also strengthens their ability to innovate and effectively respond to new societal needs.

Through the development of leadership strategies that connect with a learning-focused mindset, these institutions can optimize their resilience, increase their impact and ensure long-term sustainability in an increasingly complex and dynamic global environment. Finally, this research offers valuable insight for leaders in this sector seeking to achieve higher levels of learning culture and increase dynamic capability among their workers. Therefore, this study suggests important managerial implications for nonprofit managers, human talent staff, and academic professionals.