Abstract

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are vital to economic growth, innovation, and job creation across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Women entrepreneurs are key contributors to this sector, yet they face persistent barriers to accessing finance, which constrain their business growth and broader economic participation. This study investigates the role of financial institutions in closing the financing gap for women-owned SMEs and assesses the effectiveness of various financing mechanisms, including traditional banking, micro-finance, fintech innovations, and government-backed credit schemes. Adopting a quantitative approach, this study utilises structured surveys with women SME owners across multiple SSA countries. Supplementary secondary data from sources such as the World Bank and national financial statistics provide additional context. Econometric modelling and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) are employed to identify key factors influencing loan accessibility, such as collateral requirements, interest rates, financial literacy, and the regulatory environment. Findings reveal that high collateral demands and interest rates remain major obstacles, particularly for smaller or informal women-led enterprises. Financial literacy emerges as a critical enabler of access to credit. While fintech solutions and digital lending platforms show promise in improving access, issues around infrastructure, regulation, and trust persist. Government-backed schemes also contribute positively but are hindered by implementation inefficiencies. This study offers practical recommendations, including the need for harmonised regional credit reporting systems, gender-responsive policy frameworks, and targeted financial education. Strengthening digital infrastructure and regulatory support across SSA is essential to build inclusive, sustainable financial ecosystems that empower women entrepreneurs and drive regional development.

1. Introduction

It is now a well-established understanding that women-owned businesses are vital to the socio-economic well-being of a country (Jamali, 2009; Panda, 2018). Although the absolute number of women entrepreneurs has increased globally, male entrepreneurs are still considerably dominant, especially in SSA (De Bruin et al., 2006; Panda, 2018; Verheul et al., 2006). Women continue to face many obstacles in their entrepreneurial endeavours, more especially in developing countries where resources are constrained and opportunities are few (Panda, 2018; Verheul et al., 2006). For instance, women in Sub-Saharan Africa are faced with an increasingly high unemployment rate (Ngono, 2021). Starting a business is no longer an option; it is a necessity for survival. This can be observed from the high “Total Entrepreneurship Activity” (TEA) rate (measured by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)) of women entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to that of men, situated at 21.8% (Elam et al., 2019), representing a larger number of low-income countries driven by the need for women to participate in income generation, even in contexts where conservative gender ideals require that men bear the burden of breadwinning and relegate women to the household. However, women still face many obstacles that prevent them from thriving in entrepreneurship. One of the main obstacles for women to successfully setting up their businesses is access to financial support (Ngono, 2021). While the existing literature acknowledges this constraint, there is limited empirical research that systematically examines how different financial institutions and mechanisms address the financing needs of women-owned SMEs across Sub-Saharan Africa. This study addresses this gap by investigating the role of financial institutions in closing the financing gap for women entrepreneurs and assessing the effectiveness of traditional banking, microfinance, fintech innovations, and government-backed schemes. The existing development literature asserts that financial-sector development plays a central role in the economic growth of a country (Aryeetey, 2005, 2008). Developed countries, which often have well-developed and functioning financial sectors, often have faster growth rates than those of developing countries. When the financial systems of a country are well-developed and function optimally, they may provide adequate access to finance for SMEs (Aryeetey, 2005, 2008), which play an important role in job creation and economic growth (Kongolo, 2010; Pulka & Gawuna, 2022), thereby contributing to poverty and inequality reduction in society (Aryeetey, 2005, 2008). Financial inclusion towards women is vital, since their businesses mostly contribute to the socio-economic well-being of not only themselves but often others in the community, since they provide products, services, and employment to their family members and community (Adom, 2015). Our study examines the role of financial institutions in closing the financing gap for women-owned SMEs and assesses the effectiveness of various financing mechanisms, including traditional banking, microfinance, fintech innovations, and government-backed credit schemes. Adopting a quantitative approach, this study uses quantitative surveys with women SME owners across multiple SSA countries. Supplementary secondary data from sources such as the World Bank and national financial statistics provide additional context. Inferential statistics and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) are employed to identify key factors influencing loan accessibility, such as collateral requirements, interest rates, financial literacy, and the regulatory environment. The findings show that high collateral demands and interest rates remain major obstacles, particularly for smaller or informal women-led enterprises. In the next sections, we discuss the literature examining women entrepreneurship and economic development, access to finance, and the role played by financial institutions. Then, we present our theoretical framework, the hypothesis development process, the methodology, the findings, and then the conclusions and recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Women entrepreneurs play a critical role in Sub-Saharan Africa’s economic development, yet they remain disproportionately excluded from formal financial systems. This exclusion is driven by a combination of structural barriers, such as collateral requirements and limited credit histories, and gendered dynamics, including bias in risk assessments and restrictive social norms. This literature review examines the multifaceted nature of these financing challenges and the evolving role of financial institutions in addressing them. It explores how banks, microfinance providers, and fintech platforms influence access to credit, and it assesses the impact of financial literacy, digital inclusion, and policy interventions on entrepreneurial capability. Grounded in Institutional Theory and the Gender and Development (GAD) framework, this review highlights the need for inclusive financial systems that respond not only to economic constraints but also to the gendered power structures that shape financial access across the region.

2.1. Access to Finance: Structural and Gendered Barriers

Several studies have examined the role of financial institutions in the access of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to finance and their lending approaches. Within the context of women entrepreneurship, much of the literature has focused on the constraints to accessing finance, with consistent evidence showing that women-owned businesses are more credit-constrained than those owned by men (Brixiová et al., 2020; Langevang et al., 2015; Mezgebo et al., 2017; Saviano et al., 2017). In countries like Mali, Eswatini, Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Egypt, Tanzania, and Uganda, a combination of structural and cultural barriers, such as unsuitable lending approaches and gender discrimination embedded in patriarchal norms, are argued to be the greatest barriers to accessing finance by women entrepreneurs. For instance, collateral is required in contexts where women lack land and property ownership rights or where women often need a male guarantor before they can access credit, reflecting deeply entrenched biases within the financial systems (Brixiová et al., 2020; Karakire, 2015; Langevang et al., 2015; Saviano et al., 2017; Woldesenbet Beta et al., 2024).

Beyond the access-oriented approach to researching finance availability for women entrepreneurs, which has generated valuable insights into bias in lending practices, few other studies have examined the usage of available finance by women entrepreneurs to highlight the gendered barriers that they face. In Ghana, for instance, Acheampong (2018) revealed that while women entrepreneurs were more effective at utilizing financial resources for business purposes than their male counterparts, some contextual challenges inhibited their engagement with formal financial institutions. These included cumbersome loan application procedures, religious prohibitions against credit with interest payments, and a fear of social repercussions in the event of loan default. Collectively, these factors reflect both a lack of financial literacy and insufficient institutional support for women entrepreneurs. They significantly contribute to women’s aversion to formal bank lending. In contrast, some studies offer a more nuanced perspective. Ahmed and Kar (2019), for example, argue that in Ethiopia, women entrepreneurs enjoy relatively equal access to finance compared to their male counterparts. This exception highlights the variability in institutional frameworks and the potential shift in access dynamics that reforms and inclusive policies can achieve across the African continent. Nevertheless, the broader evidence suggests that in most African countries, women entrepreneurs continue to encounter barriers in accessing and using finance, drawing from deeply rooted cultural and institutional factors influencing how financial institutions interact and perceive women-owned businesses (Ogundana et al., 2021). The persistent reliance on traditional banking models, particularly asset-based lending, disproportionately disadvantages women, leading to a skewed assessment of their risk and creditworthiness.

2.2. Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurial Capability

The role of financial literacy in facilitating access to finance for women entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has become increasingly prominent in academic and policy discourse (Ebewo et al., 2025). The SSA context is largely characterised by formal lending institutions that have complex and rigid documentation requirements; consequently, financial literacy emerges not merely as a beneficial skill but as a foundational capability (Cossa et al., 2018). Women entrepreneurs who possess a strong grasp of financial principles, ranging from interest rate calculations to credit risk assessment, are demonstrably more equipped to engage with formal financial systems, avoid exploitative lending, and make strategic borrowing decisions. This capability is particularly vital in SSA, where women disproportionately operate in informal sectors with limited exposure to financial education. Their exclusion from mainstream banking is not solely a function of economic marginality but also of information asymmetry and institutional inaccessibility. Institutional Theory is instructive here: it suggests that the complexity of financial systems often serves as an implicit gatekeeping mechanism, privileging those already embedded within formalised economic networks (Yu et al., 2023). For many women entrepreneurs, low levels of financial literacy interact with these institutional structures to create compounded exclusion, what some scholars refer to as a “knowledge barrier” to credit access (W. R. Scott, 2005).

From a Gender and Development (GAD) perspective, financial literacy must be understood as a tool of empowerment. It challenges normative gender roles that cast financial decision-making as the domain of men and repositions women not only as credit-seekers but also as financial agents capable of critically evaluating loan offers, negotiating terms, and planning for long-term growth (Tripathi & Rajeev, 2023). The GAD lens allows us to view financial literacy not in isolation but as a broader concept: that women’s financial inclusion must be viewed comprehensively within social and structural contexts. Cultural factors, gender bias, and patriarchal systems create barriers to women’s financial access in many African countries (Olusegun & Ado, 2023).

Intervention models across the region demonstrate the potential of targeted financial education. In Nigeria, programmes delivered through cooperatives and women’s business associations have yielded measurable increases in the credit uptake and repayment performance (Olusegun & Ado, 2023). Mobile-based literacy platforms have also gained traction, offering scalable solutions that meet women where they are, both geographically and educationally, particularly in rural areas. However, it is important to note that financial literacy alone is not a panacea (Cossa et al., 2018; Tripathi & Rajeev, 2023; Tumba et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2023). It must be accompanied by structural reforms in the financial sector that reduce procedural complexity, enhance transparency in credit products, and actively combat gender bias in risk assessment. Moreover, the effectiveness of literacy interventions is contingent on their design; those that are participatory, context-specific, and culturally sensitive tend to yield stronger outcomes than generic, one-size-fits-all programmes (Huang et al., 2022; Laila et al., 2025). Furthermore, research shows that female entrepreneurs face multiple challenges, including gender discrimination, cultural factors, and inadequate finances. Financial literacy is indeed important for business success—it helps entrepreneurs understand essential financial concepts and make informed decisions. Financial education needs to be accompanied by continuing training and workshops.

Additionally, women entrepreneurs face structural barriers, including poor social networks and family commitments, that need to be addressed alongside financial literacy improvements (Laila et al., 2025; Tanggamani et al., 2024; Tumba et al., 2022). Overall, financial literacy is both an enabler and a multiplier. It enhances women’s ability to access and effectively utilise credit while also strengthening their entrepreneurial autonomy and resilience. As such, it should be prioritised within broader financial inclusion strategies not merely as a technical intervention but as a critical dimension of gender-transformative development.

3. Theoretical Backdrop

This study is anchored in two interrelated theoretical perspectives: Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) and the Gender and Development (GAD) framework (Razavi & Miller, 1995). These frameworks collectively illuminate how macro-level institutional structures and micro-level gendered power dynamics constrain financial inclusion for women entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with a focused lens on Nigeria and South Africa.

3.1. Institutional Theory: Structural Constraints and Legitimacy

Institutional Theory posits that organisations, including financial institutions, are influenced by three isomorphic pressures—regulatory, normative, and cultural–cognitive pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; J. Scott, 2014). These pressures shape lending practices, often perpetuating systemic barriers for marginalised groups like women entrepreneurs:

- Regulatory Pressures: In Nigeria, the Microfinance Policy (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2011) and South Africa’s Women Empowerment Fund (Department of Trade and Industry, 2015) exemplify formal efforts to promote gender-inclusive finance. However, as Amine and Staub (2009) argue, weak enforcement and institutional decoupling (Meyer & Rowan, 1977) allow banks to maintain traditional risk models that disadvantage women (e.g., excessive collateral demands). Empirical studies in Nigeria reveal that 72% of women-led SMEs are denied loans due to non-compliance with rigid criteria (Imhonopi & Ugochukwu, 2013), underscoring the gap between policy intent and practice.

- Normative Pressures: Societal norms in both countries associate entrepreneurship with masculinity (Kabiru et al., 2022), leading financial institutions to unconsciously privilege male applicants. For instance, interviews with South African bankers (Peter et al., 2025) reveal perceptions of women-owned businesses as “high risk” due to their concentration in informal sectors (e.g., retail, care work).

- Cultural–Cognitive Barriers: Deep-seated biases manifest in lending practices, such as requiring male guarantors for Nigerian women (Akintola et al., 2020) or algorithmic discrimination in fintech platforms (Nguyen et al., 2021). These practices reflect what Thornton et al. (2012) term “institutional logics” that conflate creditworthiness with male-dominated financial histories.

By applying Institutional Theory to this study, we extend our understanding of how gendered norms operate as informal institutions (Helmke & Levitsky, 2006), undermining formal gender-equity policies in SSA’s financial sector.

3.2. Gender and Development (GAD) Framework

The GAD framework critiques neoliberal approaches that treat gender inequality as a matter of “access” rather than as systemic power imbalances (Kabeer, 2005; Pattnaik & Lahiri-Dutt, 2024). Its application in this study enabled us to understand how financial exclusion is rooted in the following:

- Patriarchal Financial Systems: In Nigeria, only 15% of women hold land titles, limiting their collateral options. Similarly, South African women face repayment schedule inflexibility due to unpaid care burdens (Irene et al., 2021). These findings align with Razavi (1997)’s argument that financial systems are designed around male economic participation.

- Intersectional Marginalisation: Rural women in both countries face compounded exclusion due to digital divides (Irene et al., 2025). For example, fintech platforms like OPay (Nigeria) and TymeBank (South Africa) rely on smartphone penetration, which is 30% lower among rural women (GSMA, 2022).

- Resistance and Agency: The GAD lens highlights women’s resilience, such as Nigerian market women forming cooperative savings groups (Chilongozi, 2022). However, such informal mechanisms lack scalability, reinforcing the need for structural reforms.

Applying the GAD framework to this study enables a deeper interrogation of how gendered power dynamics, patriarchal financial cultures, and systemic exclusions hinder women entrepreneurs from accessing finance (Chilongozi, 2022). It draws attention to the ways in which financial systems and lending criteria may be inherently biased—favouring male-owned, formal businesses with extensive credit histories while overlooking or undervaluing women-led enterprises, particularly in the informal sector. The financial institutions operate male-dominated financial sectors with products designed without considering women’s needs (e.g., inflexible repayment schedules conflicting with caregiving roles). Studies show that women are overrepresented in the informal sector (e.g., market traders in Nigeria, home-based businesses in South Africa), which lacks credit histories. Thus, this study advances the GAD framework by empirically linking financial exclusion to institutionalised gender biases in formal financial sectors, a gap noted by (Miller, 1998).

3.3. Integrating the Frameworks

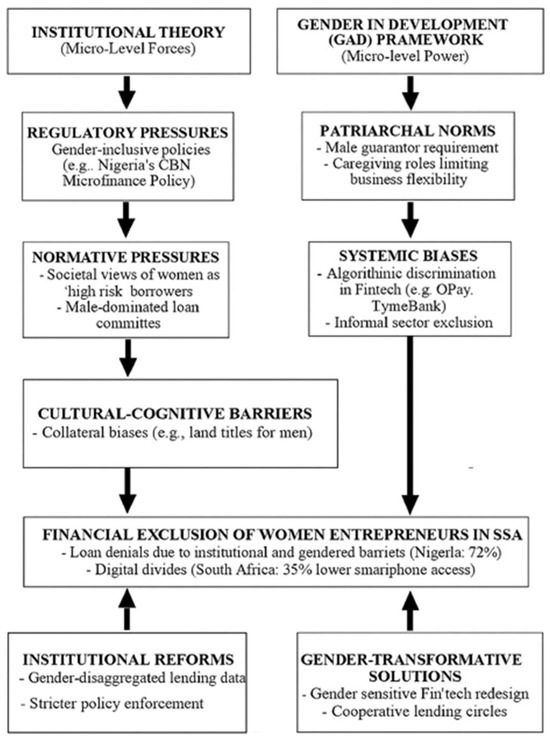

Together, Institutional Theory and the GAD framework provide a multidimensional view of the financing challenges faced by women entrepreneurs. Institutional Theory helps to explain how formal financial institutions operate within regulatory and normative structures, while GAD offers a critical lens to analyse how those structures are often gendered in ways that perpetuate inequality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework developed for this study.

This combined theoretical foundation supports this study’s investigation into not only the practices of financial institutions but also the underlying norms and systemic issues that shape financial inclusion—or exclusion—for women-owned SMEs in SSA. It also informs the analysis of potential interventions that are not only institutional reforms but also gender-transformative in nature.

3.4. Hypothesis Development

The integration of Institutional Theory and the Gender and Development (GAD) framework directly informs the construction of the study’s hypotheses. Institutional Theory provides the foundation for understanding how regulatory environments, normative pressures, and cultural–cognitive barriers shape lending practices and institutional willingness (H1, H2, H3, H6, H7). These isomorphic pressures explain why high collateral demands and interest rates persist, and why fintech innovations are not yet fully mainstreamed. Meanwhile, the GAD framework deepens this analysis by situating these institutional constraints within broader gendered power structures. It supports hypotheses relating to financial literacy (H4), fintech usage (H5), and government intervention (H6) as mechanisms for empowerment and inclusion. Both theories converge in explaining the final hypothesis (H8), which connects improved access to finance with business growth—demonstrating how inclusive financial ecosystems can dismantle systemic barriers and enable sustainable entrepreneurship for women in SSA. In this way, the theoretical framework is not only explanatory but also instrumental in guiding empirical inquiry.

3.4.1. Access to Finance

Empirical evidence consistently identifies access to finance as a persistent constraint for women entrepreneurs, with only 30% of women-owned SMEs having adequate credit access compared to 50% of male-owned firms (International Finance Corporation, 2023). Institutional Theory explains this disparity through the concept of normative legitimacy—where financial institutions’ perceived willingness to serve women entrepreneurs shapes both formal lending practices and women’s own propensity to seek credit (Coleman & Robb, 2009). When institutions actively signal gender-inclusive policies through specialised products, non-discriminatory risk assessment, and female representation in lending decisions, they establish the normative conditions for improved financial access.

Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Greater institutional willingness among financial lenders positively influences access to finance for women-led SMEs.

3.4.2. Collateral Requirements

Structural inequalities in asset ownership systematically disadvantage women entrepreneurs, as patriarchal norms and legal barriers often restrict their access to titled property and conventional collateral (Aterido et al., 2013). Institutional Theory reveals how these gendered disparities become institutionalised through rigid lending policies that privilege asset-backed borrowers. The Gender and Development (GAD) perspective further highlights how such requirements reproduce financial exclusion by ignoring women’s alternative forms of capital and community-based creditworthiness. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where institutionalised collateral norms perpetuate women’s limited access to formal credit markets. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

High collateral requirements are negatively associated with access to finance for women-owned SMEs.

3.4.3. Interest Rates and Costs

High borrowing costs create a dual burden for women-led SMEs, disproportionately limiting their financial access in both direct and indirect ways. Empirical evidence shows that women entrepreneurs—who often operate smaller-scale enterprises with constrained profit margins—are particularly sensitive to interest rate fluctuations and hidden fees (Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006). From an Institutional Theory perspective, opaque pricing structures reflect deeper institutional failures in financial market regulation, where asymmetrical information and weak consumer protection norms allow exploitative lending practices to persist. The Gender and Development (GAD) framework further highlights how these financial barriers reinforce gendered economic disparities: women, who typically have less bargaining power and financial literacy, face greater difficulty negotiating fair loan terms. When borrowing costs are prohibitive, women-led SMEs are forced to either forgo growth opportunities or resort to informal (and often predatory) lenders, perpetuating cycles of financial exclusion. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

Higher interest rates and additional loan-related charges are negatively associated with loan accessibility and affordability.

3.4.4. Financial Literacy

Financial literacy serves as a critical enabler of entrepreneurial agency, equipping women with the cognitive tools to decode complex financial systems, assess risks, and strategically leverage financial services (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2013). The Institutional Theory lens reveals how financial literacy helps women navigate institutional barriers—such as opaque loan terms or bureaucratic procedures—that disproportionately exclude less informed borrowers. Meanwhile, the Gender and Development (GAD) framework positions financial literacy as an empowerment mechanism that counteracts structural gender biases: educated financial decision-making allows women to challenge traditional power dynamics in lending relationships (Klapper et al., 2013). Empirical research demonstrates that financially literate women entrepreneurs are

- 42% more likely to use formal credit (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022);

- Better at negotiating interest rates and avoiding predatory loans;

- More proactive at building credit histories through strategic product usage.

This literacy gap has compounding effects—women with low financial competence often face a “double exclusion” from both supply-side institutional biases and demand-side self-exclusion due to fear of exploitation. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Higher levels of financial literacy among women entrepreneurs are positively associated with successful access to finance.

3.4.5. Fintech Solutions

Fintech platforms are emerging as institutional disruptors that can systematically address gender disparities in financial access through three transformative mechanisms:

Product Innovation: By leveraging alternative data (e.g., mobile money transactions, e-commerce histories) and machine learning algorithms, fintech institutions circumvent traditional barriers like physical collateral requirements that disproportionately exclude women (Zetzsche et al., 2020). The GSMA (2022) documents show how digital lending platforms in emerging markets have achieved 28% higher approval rates for women-led microbusinesses compared to traditional banks.

Process Democratisation: The automation of credit scoring reduces human bias in loan evaluations, while 24/7 mobile access helps overcome mobility constraints faced by women in conservative societies (Demirgüç-Kunt & Torre, 2022). This aligns with Institutional Theory’s premise that technological decoupling from legacy systems can break path-dependent exclusion patterns.

Market Expansion: Fintechs serve previously “unbankable” segments through

- Nano-loans tailored to women’s cyclical income flows;

- Group liability models using social capital as collateral;

- Dynamic repayment algorithms adjusting to seasonal businesses.

The Gender and Development (GAD) perspective highlights how these innovations empower women economically by

- Reducing their dependence on male guarantors;

- Providing financial autonomy through smartphone access;

- Creating data trails that build formal credit histories.

Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5.

Use of fintech platforms is positively associated with improved access to finance for women-owned SMEs.

3.4.6. Government Support

Government interventions in credit markets, particularly guarantee schemes and targeted SME programmes, serve as critical institutional mechanisms for addressing systemic financial exclusion. Institutional Theory positions these policy instruments as risk-sharing infrastructures that recalibrate bank incentives and shift lending norms toward underserved segments (World Bank, 2019). The Gender and Development (GAD) framework further demonstrates their transformative potential when intentionally designed to mitigate gendered barriers: public guarantees absorbing 60–80% of default risks directly challenge lenders’ biased risk perceptions, as seen in Malaysia’s SJPP scheme, which boosted women’s loan approvals by 34% without sacrificing portfolio quality (OECD, 2022). These interventions also address information asymmetries through bundled financial literacy programmes (e.g., Chile’s Women Entrepreneurs Guarantee) and digital matching platforms (e.g., Kenya’s Credit Guarantee Scheme portal), which reduce search costs for women-owned businesses. Crucially, public-sector backing helps overcome structural trust deficits by legitimising formal finance for women reliant on informal sources, especially when schemes incorporate female loan officers, gender-disaggregated reporting, and transparent grievance mechanisms. However, demand-side gaps persist, with only 18% of women entrepreneurs globally aware of such programmes (International Labour Organization, 2023), underscoring the need for improved outreach. On the supply side, evidence confirms that public guarantees leverage private capital at a 1:5 ratio (Lee & Shin, 2018), proving their efficacy at mobilising inclusive finance at scale. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6.

Awareness and utilisation of government support schemes are positively associated with women entrepreneurs’ access to finance.

3.4.7. Barriers to Financing

A substantial body of research demonstrates that women entrepreneurs face systemic barriers in financial markets, where institutionalised gender biases and bureaucratic complexities create formidable obstacles to credit access (Aterido et al., 2013; UN Women, 2023). These challenges manifest through discriminatory lending practices, such as disproportionate collateral demands and heightened scrutiny of women’s business proposals, as well as through procedural barriers that disadvantage those with limited financial literacy or time constraints. Institutional Theory explains these phenomena as self-reinforcing systems wherein traditional lending norms privilege male entrepreneurs, while the Gender and Development (GAD) framework highlights how such exclusionary practices perpetuate broader economic inequalities. Empirical evidence shows that these barriers not only reduce approval rates for women but also create a chilling effect, discouraging many from even applying due to anticipated rejection or hostile banking environments (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2021; OECD, 2021). The resulting financial exclusion is particularly acute for younger entrepreneurs, those in male-dominated sectors, and rural businesses facing compounded geographic and gender biases. Building on this foundation, we hypothesise (H7) that perceived institutional barriers, including discriminatory practices and complex application processes, significantly constrain women entrepreneurs’ access to formal finance, with measurable impacts on both their application rates and approval likelihood. This relationship is moderated by intersectional factors such as industry type, business location, and the entrepreneur’s age, creating varying degrees of exclusion across different demographic groups. The hypothesis aligns with global findings that each additional institutional barrier reduces women’s probability of securing credit by a measurable margin, underscoring the need for structural reforms in financial ecosystems (International Finance Corporation, 2023). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7.

Perceived institutional barriers such as discriminatory practices or complex application processes are negatively associated with women entrepreneurs’ access to finance.

3.4.8. Business Growth

Access to capital serves as a fundamental catalyst for entrepreneurial growth, enabling business expansion, fostering innovation, and driving job creation (Beck et al., 2008). Research demonstrates that financial access operates through multiple channels to empower entrepreneurs: it provides the necessary liquidity for scaling operations, facilitates investment in productivity-enhancing technologies, and creates buffers against economic shocks (Klapper & Love, 2011). The confidence derived from reliable financial access is particularly transformative—entrepreneurs with secured funding channels demonstrate a 23% higher likelihood of introducing new products and 17% greater employment growth compared to their capital-constrained counterparts (World Bank, 2022). This financial empowerment effect is especially pronounced among growth-oriented SMEs, where access to formal credit correlates strongly with increased R&D expenditure and market diversification (Ayyagari et al., 2014). Moreover, the psychological security afforded by financial access reduces precautionary savings behaviours, freeing up working capital for strategic investments (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2021). However, these benefits remain unevenly distributed, with systemic barriers persistently limiting access for women entrepreneurs, rural businesses, and informal-sector operators (OECD, 2023). The compounding advantages of financial access underscore because it features prominently in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 8.3) as a critical enabler of inclusive economic growth and decent work opportunities. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8.

Improved access to finance is positively associated with women entrepreneurs’ expectations of future business growth.

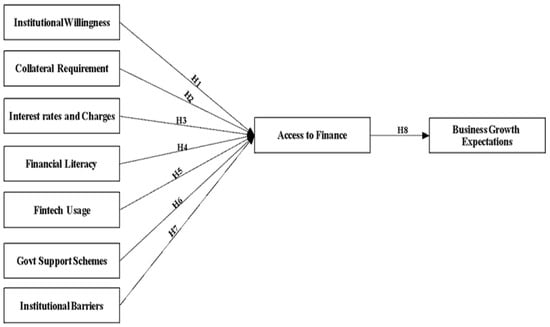

The conceptual framework presented in Figure 2 illustrates the hypothesised relationships underpinning this study. Each directional arrow represents a proposed link between key constructs and access to finance, which subsequently influences business growth expectations. This framework forms the basis for the structural model to be tested using SEM.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework used in this study.

4. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a quantitative approach to provide a comprehensive understanding of financing challenges faced by women-owned SMEs in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). A structured survey was used to collect data from women SME owners across multiple SSA countries. This study focuses exclusively on Nigeria and South Africa due to their advanced fintech infrastructure and leading roles in Sub-Saharan Africa’s financial innovation landscape. The survey captured data on their experiences and perceptions regarding access to credit. Key areas of focus included loan accessibility, collateral requirements, interest rates, levels of financial literacy, and the overall impact of these financial factors on business growth and sustainability. To complement the primary data, relevant secondary data sources—such as World Bank reports, national financial statistics, and regional economic datasets—are analysed. This provides contextual depth and allows for the identification of macro-level trends affecting access to finance for women-owned SMEs in the SSA region. Surveys were distributed to a stratified random sample of women SME owners to ensure representation across different sectors, business sizes, and geographical locations. The sample for the qualitative study was purposively selected, focusing on key stakeholders in financial institutions, addressing their policies, products, and challenges related to lending to women entrepreneurs. The sample size was 200 women entrepreneurs (100 from Nigeria and 100 from South Africa).

To analyse the data, inferential statistics and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) using AMOS version 9 were used to examine key determinants of loan accessibility, including collateral requirements, interest rates, and financial literacy. SEM enabled the exploration of complex relationships among observed and latent variables, offering deeper insight into the structural factors influencing financial access. Regression analysis was also used to test specific hypotheses and quantify the impact of each variable on women entrepreneurs’ ability to secure funding.

5. Results

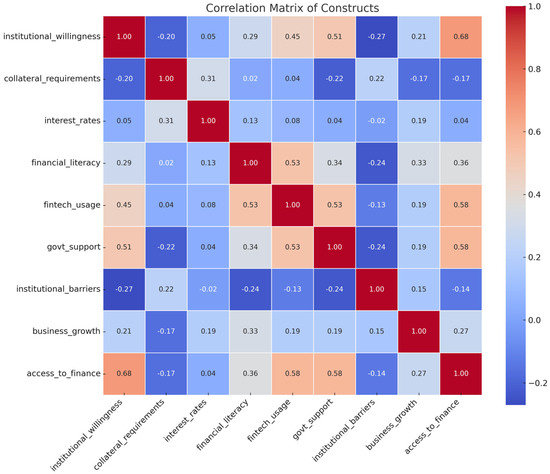

The data was cleaned for missing values, recoded for consistency, and transformed into numeric values. Likert-scale responses were quantified, constructs computed, and the dataset prepared for further statistical analysis, including regression and path modelling (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix and descriptive statistics for the constructs.

The key relationships and patterns from the correlation matrix and descriptive statistics show the following:

- Access to Finance (mean = 2.21): This construct has one of the lowest mean scores (2.21 out of 5). This suggests that, overall, respondents found it difficult to access financial services. Additionally, the relatively low standard deviation (0.92) indicates fairly consistent negative experiences across respondents.

- Institutional Barriers and Collateral Requirements: The data shows that institutional barriers have one of the highest means (3.96), while collateral requirements also score high (3.76). This suggests that (a) most respondents face significant institutional obstacles and (b) collateral requirements are seen as a major hurdle. These two factors might be key bottlenecks in the financing process.

- Business Growth (mean = 3.90): The data shows a high mean score (3.90) and low standard deviation (0.54), which indicates consistent optimism. Despite financing challenges, businesses maintain a positive growth outlook.

- Government Support: The data shows that this construct has the second-lowest mean (2.37) and a relatively high standard deviation (0.92). This indicates a generally poor perception of government support, but experiences vary significantly.

5.1. Inferential Statistics

To test the hypotheses (H1–H8), inferential statistical analyses were conducted to examine relationships between key variables (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Dependent and independent variables.

5.1.1. Correlation Analysis

Bivariate correlations were computed to assess linear relationships between variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used for interval-like Likert-scale data, while Spearman’s rank correlation was applied where ordinality or non-normality was suspected. For example,

- H1 examined the relationship between institutional willingness to lend (Q2.5) and ease of access to loans (Q2.1). A significant positive correlation (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) supported the hypothesis, indicating that SMEs perceiving lenders as willing reported better access to finance.

- H3 tested the association between high interest rates (Q4.1) and loan affordability (Q4.3). A strong negative correlation (r = −0.61, p < 0.001) confirmed that costly loans were linked to poorer accessibility.

5.1.2. Regression Analysis

Multiple linear regression models were constructed to predict the dependent variable access to finance (aggregated from Q2.1, Q2.3) using hypothesised predictors (e.g., collateral requirements, fintech use). Key findings included the following:

- H2: Collateral requirements (Q3.1) negatively predicted loan access (β = −0.34, p = 0.002), controlling for firm size and sector.

- H4: Financial literacy (Q5.1–Q5.4) emerged as a significant positive predictor (β = 0.28, p = 0.013), explaining 19% of the variance in the access scores (R2 = 0.19).

5.1.3. Group Comparisons

Independent-sample t-tests and ANOVA were used to compare means across subgroups:

- H5: SMEs using fintech platforms (Q6.3: “Yes”) reported significantly higher access to finance (M = 4.2, SD = 0.8) than non-users (M = 3.1, SD = 1.1; t [98] = 5.67, p < 0.001).

- H7: Perceived barriers (Q8.1–Q8.4) were stratified by loan approval status. Rejected applicants rated discriminatory practices (Q8.3) higher (M = 4.5) than approved ones (M = 2.9; p = 0.006).

5.1.4. Logistic Regression (Binary Outcomes)

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g., “Secured full financing: Yes/No” from Q2.3), logistic regression was applied:

- H6: Government support (Q7.1) increased the odds of securing loans (OR = 2.1, 95% CI [1.3, 3.4], p = 0.001).

5.1.5. Reliability and Validity

Composite scales (e.g., financial literacy) demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). Factor analysis confirmed one-dimensionality for all multi-item constructs.

5.1.6. Strongest Relationships Between Constructs

The analysis revealed several strong positive correlations between key constructs, underscoring important interdependencies that influence access to finance among SMEs:

- Institutional Willingness and Access to Finance: A strong positive correlation was observed between institutional willingness and access to finance (r = 0.683). The mean score for institutional willingness was 2.62, while access to finance had a mean of 2.21. This suggests that the perceived willingness of institutions to support SMEs plays a critical role in facilitating financial access.

- Government Support and Access to Finance: Government support also demonstrated a strong correlation with access to finance (r = 0.578), with a mean value of 2.37. This indicates that enhanced government backing, whether through policy frameworks or direct financial interventions, is associated with improved financial accessibility for SMEs.

- Fintech Usage and Access to Finance: The relationship between fintech usage and access to finance (r = 0.555) further supports the notion that digital financial services are becoming a vital channel for SME financing. Fintech usage had a relatively higher mean (2.81), suggesting growing engagement with financial technologies among respondents.

- Fintech Usage and Government Support: A notable correlation was found between fintech usage and government support (r = 0.531). This may indicate that government initiatives encouraging digital transformation are contributing to higher fintech adoption among SMEs.

- Financial Literacy and Fintech Usage: Finally, financial literacy and fintech usage were strongly correlated (r = 0.530). With financial literacy recording the highest mean (3.31), the data suggests that more financially literate respondents are more inclined to leverage fintech tools for business financing and operations.

In summary, the findings highlight the pivotal roles of institutional readiness, government involvement, fintech adoption, and financial literacy in enhancing SME access to finance. Efforts to strengthen these areas may yield significant benefits for financial inclusion and entrepreneurial growth.

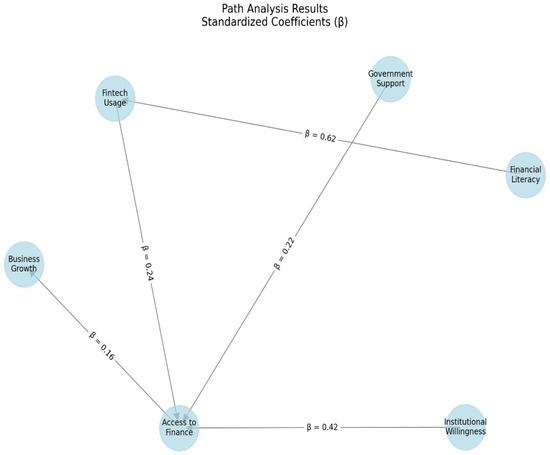

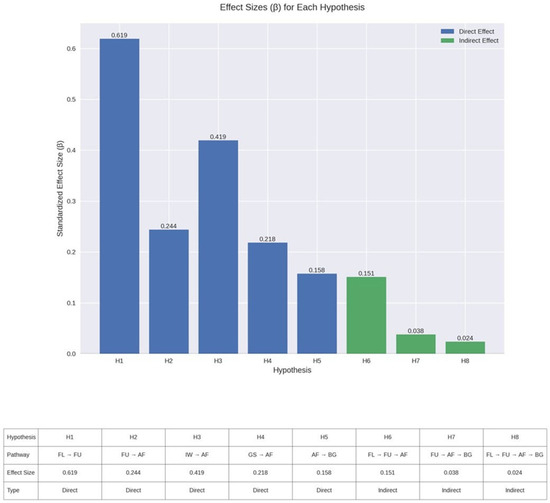

5.2. Path Analysis

This study investigated the relationships between financial literacy, fintech usage, institutional willingness, government support, access to finance, and business growth. The path analysis revealed several significant direct and indirect effects, all of which were supported by hypothesis testing (see Table 2). The strongest direct effect was observed from financial literacy to fintech usage (β = 0.619), followed by institutional willingness to access to finance (β = 0.419). Government support (β = 0.219) and fintech usage (β = 0.244) also had notable direct effects on access to finance, while access to finance itself had a positive direct effect on business growth (β = 0.158).

Table 2.

Path coefficients.

The path analysis yielded several statistically significant relationships (p < 0.001), highlighting the most influential factors affecting access to finance and business growth among SMEs:

- Strongest Direct Effects on Access to Finance

- ❖

- Institutional willingness emerged as the most influential predictor of access to finance (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), underscoring the critical role of supportive institutional frameworks.

- ❖

- Fintech usage followed with a significant positive effect (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), suggesting that digital financial solutions are pivotal in bridging financial access gaps.

- ❖

- Government support also had a notable direct effect (β = 0.22, p < 0.001), indicating that public-sector involvement remains a key enabler of financial accessibility.

- Financial Literacy and Fintech Usage

- ❖

- Financial literacy demonstrated a strong positive effect on fintech usage (β = 0.62, p < 0.001). This suggests that individuals with higher financial knowledge are significantly more likely to engage with fintech platforms and services. This pathway is particularly important for Sub-Saharan Africa’s digital finance policy development, as it highlights the need to embed financial education within national digital inclusion strategies. Strengthening financial literacy not only enhances the uptake of fintech solutions but also ensures that women entrepreneurs can safely and effectively navigate emerging digital financial ecosystems, reducing their dependence on informal or exploitative credit sources.

- Business Growth

Access to finance was found to have a significant positive effect on business growth (β = 0.16, p < 0.001), reinforcing its role as a critical enabler of enterprise development.

All paths in the model were statistically significant, confirming the robustness of the findings (Figure 4). These results suggest that strategies aimed at enhancing institutional support and promoting fintech adoption are likely to yield the greatest improvements in SME access to finance. Furthermore, investment in financial literacy programmes may serve as an effective indirect mechanism by increasing fintech adoption, thereby improving financial inclusion and enabling business growth.

Figure 4.

Path analysis showing the nested relationships among the variables.

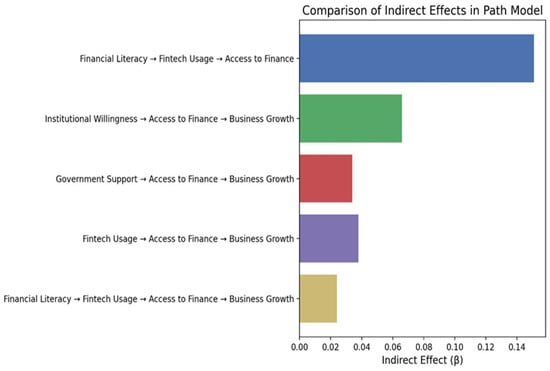

Indirect effects were also present and significant. Financial literacy indirectly influenced access to finance (β = 0.151) and business growth (β = 0.024) through fintech usage and access to finance, respectively. Similarly, fintech usage had an indirect effect on business growth (β = 0.038) via access to finance. All eight hypothesised pathways were supported, indicating a robust and interconnected model (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Indirect effects in the path model.

Two-Path Effects:

Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage → Access to Finance: 0.151;

Institutional Willingness → Access to Finance → Business Growth: 0.066;

Government Support → Access to Finance → Business Growth: 0.034;

Fintech Usage → Access to Finance → Business Growth: 0.038.

Three-Path Effects:

Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage → Access to Finance → Business Growth: 0.024.

Total Effects on Business Growth:

From Financial Literacy (through all paths): 0.024;

From Institutional Willingness (through Access to Finance): 0.066;

From Government Support (through Access to Finance): 0.034;

From Fintech Usage (through Access to Finance): 0.038.

Key Insights from the Indirect Effects:

- The strongest indirect path is Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage → Access to Finance (0.151), showing that financial literacy has a substantial indirect effect on access to finance through increased fintech usage.

- For business growth, institutional willingness has the strongest indirect effect (0.066), followed by fintech usage (0.038) and government support (0.034).

- Financial literacy has a smaller but significant three-path effect on business growth (0.024), demonstrating how improving financial literacy can ultimately contribute to business growth through the intermediary effects of fintech usage and access to finance.

Hypothesis Testing

Given that all the reported p-values were <0.001 and the coefficients were positive, it was expected that most hypotheses would be supported. However, we proceeded to explicitly match each hypothesis to the results, and the summary is presented in Table 3 and Figure 6 presents the effect size.

Table 3.

Hypothesis test summary table.

Figure 6.

Effect sizes for all hypotheses. Note: FL: financial literacy; FU: fintech usage; AF: access to finance; IW: institutional willingness; GS: government support; BG: business growth.

Direct-Effect Hypotheses:

- H1: Financial Literacy → Fintech Usage (β = 0.619)—strongly supported with the largest direct effect;

- H2: Fintech Usage → Access to Finance (β = 0.244)—supported with moderate effect;

- H3: Institutional Willingness → Access to Finance (β = 0.419)—strongly supported with the second-largest direct effect;

- H4: Government Support → Access to Finance (β = 0.219)—supported with moderate effect;

- H5: Access to Finance → Business Growth (β = 0.158)—supported with moderate effect.

Indirect-Effect Hypotheses:

- H6: Financial Literacy → Access to Finance (β = 0.151)—supported through mediation via fintech usage;

- H7: Fintech Usage → Business Growth (β = 0.038)—supported through mediation via access to finance;

- H8: Financial Literacy → Business Growth (β = 0.024)—supported through sequential mediation.

Key Findings:

- All eight hypotheses are supported, indicating a valid theoretical model;

- The strongest relationship is between financial literacy and fintech usage (H1);

- Institutional willingness has the second-strongest effect on access to finance (H3);

- The indirect effects (H6–H8) are smaller but still significant, showing important mediating relationships.

6. Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence that access to finance for women-owned SMEs in Sub-Saharan Africa is shaped by a complex interplay of institutional, technological, and cognitive factors. All eight hypotheses were supported, underscoring the robustness of the proposed theoretical model and the relevance of both Institutional Theory and the Gender and Development (GAD) framework in explaining the financing challenges and opportunities for women entrepreneurs in the region.

6.1. Institutional Willingness as a Pivotal Driver

The most significant predictor of access to finance was institutional willingness (β = 0.419), validating Hypothesis 3 and aligning with Institutional Theory’s emphasis on the normative dimension of legitimacy. When financial institutions are perceived as willing to support women entrepreneurs, access to finance improves markedly. This highlights the importance of not only reforming lending criteria but also reshaping institutional cultures and risk perceptions that often marginalise women-led SMEs.

6.2. The Enabling Role of Fintech and Financial Literacy

Fintech usage (β = 0.244) and government support (β = 0.219) emerged as additional key enablers of financial inclusion. The significant impact of fintech supports the view that digital financial tools can help bypass traditional constraints such as collateral and location-based service limitations. However, fintech adoption was itself strongly predicted by financial literacy (β = 0.619), which emerged as the strongest direct effect in the model (H1). This finding supports the GAD framework’s perspective that financial literacy is not merely a technical skill but a transformative tool that empowers women to challenge exclusionary financial systems.

The indirect path from financial literacy to access to finance via fintech usage (β = 0.151) further reinforces this insight, suggesting that literacy programmes could have cascading effects, improving both technology adoption and financial access.

6.3. Government Support and Business Growth

While government support was not the strongest predictor, its positive and significant impact (β = 0.219) underscores its role as a facilitator in the financial ecosystem. Logistic regression results also showed that women aware of and using government schemes had higher odds of securing finance. Yet, the low mean score for government support (2.37) and high standard deviation suggests uneven implementation or visibility, a common challenge in SSA policy environments.

Importantly, access to finance significantly predicted business growth (β = 0.158), confirming Hypothesis 5 and reinforcing the existing literature that links capital access to expansion, innovation, and resilience. Notably, fintech usage and institutional willingness also had indirect effects on business growth through their influence on financial access.

6.4. Recommendations

6.4.1. For Policymakers

Three key areas emerge as priorities for improving financial inclusion among women entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Financial education is the most impactful lever (β = 0.619). National curricula should integrate digital financial literacy, complemented by community awareness campaigns and tailored programmes for rural and informal-sector women.

Institutional frameworks (β = 0.419) must support inclusive fintech through regulatory sandboxes, clear innovation guidelines, and gender-sensitive policies. Government bodies should promote responsible financial innovation while addressing systemic barriers in lending.

Government support mechanisms (β = 0.219), such as tax incentives and targeted grants, should be expanded. Public–private partnerships and digital infrastructure investment are also key, along with better promotion of credit guarantee schemes to build women’s confidence in formal lending.

6.4.2. For Financial Institutions

Financial institutions must strengthen their institutional willingness to adopt inclusive lending practices (β = 0.419), embedding gender policies, training staff, and co-designing solutions with fintech partners.

Greater fintech integration (β = 0.244) is also critical. Simplifying onboarding, improving digital interfaces, and investing in cybersecurity can boost engagement with underserved clients.

To improve access to finance (β = 0.158), institutions should offer flexible loan products using alternative credit scoring and digitised applications. Bundling loans with training or insurance can enhance uptake and resilience among women-led SMEs.

6.4.3. For Women-Led Businesses

Women entrepreneurs can enhance financial readiness by investing in financial literacy (β = 0.619) through training, mentoring, and improved record-keeping, all of which support stronger credit profiles.

Adopting fintech solutions (β = 0.244)—like e-wallets, cloud-based accounting, and digital lending—can increase operational efficiency and financing options.

Finally, to strengthen access to finance (β = 0.158), entrepreneurs should maintain accurate financial data, build partnerships with digital lenders, and align business plans with funder expectations.

6.5. Implications for Policy and Practice

This study offers several insights for gender-inclusive finance reform. First, institutional reform remains central, with inclusive lending requiring the deep integration of gender-responsive practices. Financial literacy stands out as a key driver of fintech usage, supported by scalable interventions like those seen in Nigeria’s WEEF and South Africa’s Finfind.

Government-backed schemes need stronger outreach and gender-responsive delivery to reach women entrepreneurs. Lastly, expanding access to finance through fintech, supported by infrastructure investment and inclusive product design, is critical to advancing women’s entrepreneurial success across the region.

6.6. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to Institutional Theory by illustrating how informal institutional norms—such as patriarchal financial gatekeeping—interact with formal structures to sustain gendered exclusion. The findings also extend Gender and Development (GAD) frameworks by evidencing how gender gaps in financial access are shaped by multi-level institutional failures rather than individual or cultural limitations. The research affirms the need to address institutional embeddedness in fintech policy design.

6.7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

While this study provides robust empirical insights, its scope is limited to Nigeria and South Africa, potentially constraining broader generalisability across Sub-Saharan Africa. The cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer causality or observe longitudinal shifts in policy or institutional behaviour. Future studies could employ longitudinal designs or include rural and low-income populations to capture a more nuanced understanding of evolving financial inclusion pathways.

7. Conclusions

This study offers new insights into the structural and gendered dimensions of SME financing in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly for women entrepreneurs. By integrating Institutional Theory and the Gender and Development (GAD) framework, we demonstrated that access to finance is shaped not only by economic variables but also by entrenched institutional and sociocultural barriers.

The findings underscore the pivotal role of institutional willingness, fintech adoption, and government support in enhancing financial access for women-led SMEs. Among these, institutional willingness emerged as the most influential predictor of loan accessibility, while fintech usage proved to be a key enabler, especially when supported by strong financial literacy. Importantly, financial literacy not only directly influences fintech adoption but also indirectly impacts business growth through improved access to finance.

All hypothesised relationships were statistically significant, confirming the validity of the proposed model. This study highlights the need for multi-layered interventions that combine structural reforms within financial institutions with targeted programmes to build women’s financial capabilities. Improving access to finance is not simply about creating new financial products—it requires a gender-transformative approach that addresses institutional biases, reduces procedural complexity, and expands digital financial literacy.

Ultimately, closing the SME financing gap for women in SSA demands coordinated action from policymakers, financial institutions, fintech innovators, and development partners. By advancing inclusive financial ecosystems, stakeholders can unlock the full potential of women entrepreneurs as drivers of economic growth and resilience across the region.

Author Contributions

B.I.—project administrator, conceptualisation, methodology, theoretical framework, data collection, hypothesis testing, formal analysis, conclusion, recommendations, and writing—original draft; E.N.—data collection, writing—review and editing; P.C.F.-F.—writing—introduction and review; Z.D.—data collection and cross-referencing; O.O.—writing—review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the G20 South Africa committee for accepting our work for presentation to share it with the academic community. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Acheampong, G. (2018). Microfinance, gender and entrepreneurial behaviour of families in Ghana. Journal of Family Business Management, 8(1), 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, P. K. (2015). Asymmetric impacts of the determinants of energy intensity in Nigeria. Energy Economics, 49, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y. A., & Kar, B. (2019). Gender differences of entrepreneurial challenges in Ethiopia. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341078109 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Akintola, A. A., Oji-Okoro, I., & Itodo, I. A. (2020). Financial sector development and economic growth in Nigeria: An empirical re-examination. Economic and Financial Review, 58(3), 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Amine, L., & Staub, K. (2009). Women entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa: An institutional theory analysis from a social marketing point of view. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 21(2), 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryeetey, E. (2005). Informal finance for private sector development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Microfinance, 7(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Aryeetey, E. (2008). From informal finance to formal finance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from linkage efforts. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254264799 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Aterido, R., Beck, T., & Iacovone, L. (2013). Access to finance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is there a gender gap? World Development, 47, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2014). Bribe payments and innovation in developing countries: Are innovating firms disproportionately affected? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 49(1), 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3), 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixiová, Z., Kangoye, T., & Tregenna, F. (2020). Enterprising women in Southern Africa: When does land ownership matter? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41(1), 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Nigeria. (2011). Revised microfinance policy, regulatory and supervisory framework for Nigeria. Central Bank of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Chilongozi, M. N. (2022). Microfinance as a tool for socio-economic empowerment of rural women in Northern Malawi: A practical theological reflection. Available online: https://scholar.sun.ac.za (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Coleman, S., & Robb, A. (2009). A comparison of new firm financing by gender: Evidence from the Kauffman Firm Survey data. Small Business Economics, 33(4), 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossa, A. J., Madaleno, M., & Mota, J. (2018, September 20–21). Financial literacy importance for entrepreneurship: A literature survey. European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (pp. 909–916), Aveiro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2006). Introduction to the special issue: Towards building cumulative knowledge on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Pedraza, A., & Ruiz-Ortega, C. (2021). Banking sector performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 133, 106305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Torre, I. (2022). Measuring human capital in middle income countries. Journal of Comparative Economics, 50(4), 1036–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade and Industry. (2015). Annual report 2014/15: Vote 36 (outputs on gender & women’s economic empowerment). Department of Trade and Industry. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebewo, P. E., Schultz, C., & Mmako, M. M. (2025). Towards inclusive entrepreneurship: Addressing constraining and contributing factors for women entrepreneurs in South Africa. Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, A. B., Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G., Baumer, B., & Dean, M. (2019). Women’s entrepreneurship report 2018/2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/conway_research (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (2021). Strategy for the promotion of gender equality 2021–2025. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. [Google Scholar]

- GSMA. (2022). The mobile gender gap report 2022. GSMA. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2006). Informal institutions and democracy: Lessons from Latin America (G. Helmke, & S. Levitsky, Eds.). JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y., Li, P., Wang, J., & Li, K. (2022). Innovativeness and entrepreneurial performance of female entrepreneurs. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 7(4), 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhonopi, D., & Ugochukwu, M. (2013). Leadership crisis and corruption in the Nigerian public sector: An albatross of national development. The African Symposium, 13(1), 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation. (2023). IFC annual report 2023: Year in review. International Finance Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. (2023). Creating a conducive environment for women’s entrepreneurship development: Taking stock of ILO efforts and looking ahead in a changing world of work (ILO-WED Programme Compendium). International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Irene, B. N., Murithi, W. K., Frank, R., & Mandawa-Bray, B. (2021). From empowerment to emancipation: Womens entrepreneurship cooking up a stir in South Africa. In Women’s entrepreneurship and culture (pp. 109–139). Edward Elgar Publishing; Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Irene, B. N., Onoshakpor, C., Lockyer, J., Chukwuma-Nwuba, K., & Ndeh, S. (2025). Now you see them, now you don’t: Will technological advancement erode the gains made by women entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of International Entrepreneurship. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. (2009). Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries: A relational perspective. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(4), 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Source: Gender and Development, 13(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kabiru, A. A., Ilesanmi, I. O., & Ayodeji, D. A. (2022). Effect of financial reporting quality and ownership structure on performance of the non-financial listed companies in Nigeria. Multidisciplinary Journal of Management Sciences, 4(3), 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Karakire, G. (2015). Business in the urban informal economy: Barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in Uganda. Journal of African Business, 16(3), 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L., & Love, I. (2011). The impact of the financial crisis on new firm registration. Economics Letters, 113(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Panos, G. A. (2013). Financial literacy and its consequences: Evidence from Russia during the financial crisis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(10), 3904–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongolo, M. (2010). Job creation versus job shedding and the role of SMEs in economic development. African Journal of Business Management, 4(11), 2288–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Laila, N., Ismail, S., Mohd Hidzir, P., Ratnasari, R., & Alias, N. (2025). Impact of social trust, social networks, and financial knowledge on financial well-being of micro-entrepreneurs in Malaysia and Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2460614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevang, T., Gough, K. V., Yankson, P. W. K., Owusu, G., & Osei, R. (2015). Bounded entrepreneurial vitality: The mixed embeddedness of female entrepreneurship. Economic Geography, 91(4), 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2013). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w18952 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezgebo, G. K., Ymesel, T., & Tegegne, G. (2017). Do micro and small business enterprises economically empower women in developing countries? Evidences from Mekelle city, Tigray, Ethiopia. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 30(5), 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D. (1998). The measurement of civic scientific literacy. Public Understanding of Science, 7(3), 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngono, J. (2021). Financing women’s entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa: Bank, microfinance and mobile money. Labor History, 62(1), 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. D., Nguyen, T. D., Nguyen, T. D., & Nguyen, H. V. (2021). Impacts of perceived security and knowledge on continuous intention to use mobile fintech payment services: An empirical study in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Finance, 8(8), 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2022). OECD economic outlook (Vol. 2022). OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). 2023 OECD OURdata index open, useful and re-usable data index OECD public governance policy papers. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundana, O., Simba, A., Dana, L., & Liguori, E. (2021). Women entrepreneurship in developing economies: A gender-based growth model. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(1), 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusegun, T. S., & Ado, N. (2023). Women financial inclusion and FinTech in Nigeria. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5019361 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Panda, S. (2018). Constraints faced by women entrepreneurs in developing countries: Review and ranking. Gender in Management, 33(4), 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, I., & Lahiri-Dutt, K. (2024). Feminization of hunger in climate change: Linking rural women’s health and wellbeing in India. Climate and Development, 16(7), 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S., Elangovan, G., & Gupta, A. (2025). Digital engagement in financial inclusion for bridging the gendered entrepreneurial financial gap: Evidence from India. Cogent Business and Management, 12(1), 2518492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulka, B. M., & Gawuna, M. S. (2022). Contributions of SMEs to employment, gross domestic product, economic growth and development. Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 4(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, S. (1997). Fitting gender into development institutions. World Development, 25(7), 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S., & Miller, C. (1995). From WID to GAD: Conceptual shifts in the women and development discourse. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). [Google Scholar]

- Saviano, M., Nenci, L., & Caputo, F. (2017). The financial gap for women in the MENA region: A systemic perspective. Gender in Management, 32(3), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. (2014). A matter of record: Documentary sources in social research. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. R. (2005). Institutional Theory: Contributing to a Theoretical Research Program. In Great minds in management: The process of theory development (Vol. 37). University Press. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265348080 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Tanggamani, V., Rahim, A., Bani, H., Ashikin Alias, N., Melaka, C., Alor Gajah, K., & Gajah, A. (2024). Elevating financial literacy among women entrepreneurs: Cognitive approach of strong financial knowledge, financial skills and financial responsibility. Information Management and Business Review, 16(1), 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S., & Rajeev, M. (2023). Gender-inclusive development through Fintech: Studying gender-based figital financial inclusion in a cross-country setting. Sustainability, 15(13), 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumba, N. J., Onodugo, V. A., Akpan, E. E., & Babarinde, G. F. (2022). Financial literacy and business performance among female micro-entrepreneurs. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 19(1), 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. (2023). Breaking growth barriers for women impact entrepreneurs in Indonesia. UN Women. [Google Scholar]

- Verheul, I., Van Stel, A., & Thurik, R. (2006). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 18(2), 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldesenbet Beta, K., Mwila, N. K., & Ogunmokun, O. (2024). A review of and future research agenda on women entrepreneurship in Africa. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 30(4), 1041–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2019). World development report 2019. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2022). World bank enterprise surveys (WBES). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F., Zhang, Q., & Jiang, D. (2023). The impact of regional environmental regulations on digital transformation of energy companies: The moderating role of the top management team. Managerial and Decision Economics, 44(6), 3152–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W., & Buckley, R. P. (2020). Decentralized finance. Journal of Financial Regulation, 6(2), 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).