Abstract

The oil and gas industry remains vital to the global economy, yet its operations contribute significantly to environmental degradation, one of the most urgent challenges of the 21st century. This study explores the lived experiences of those directly impacted by the negative externalities of oil and gas activities, with a focus on gas flaring, oil spills, and habitat loss. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental conservation in lower-income countries remain underexplored in the existing literature. This study addresses that gap by specifically examining Nigeria’s oil and gas industry context. It examines the extent to which CSR initiatives address or intensify these environmental issues, raising the central question: to what extent do CSR efforts contribute meaningfully to environmental conservation, and how are they perceived by affected communities? Using an exploratory qualitative approach, this study draws on in-depth, face-to-face interviews with key stakeholders, including oil company staff and host community members. Data were analysed thematically through inductive coding, leading to the construction of one overarching theme: “CSR as a strategic response.” This theme emerged from three central codes—afforestation, shore protection, and environmental conservation and remediation. Findings suggest that CSR must evolve from transactional interventionist gestures to long-term ecological stewardship.

1. Introduction

The oil and gas industry is a cornerstone of the global economy, supplying essential energy that fuels transportation, powers industries, and supports daily life (Galieriková & Materna, 2020). Yet, it faces mounting challenges in addressing environmental challenges emerging from its business externalities (Akinwumiju et al., 2020; Koolwal & Khandelwal, 2019). Therefore, environmental degradation has emerged as one of the most pressing global challenges of the 21st century (Ahmad et al., 2022), with lower-income economies bearing a disproportionate burden of its impacts (Dsilva et al., 2025). Among these, Nigeria stands out as a critical case study, especially in the context of the oil and gas industry, which forms the backbone of the country’s economy (Animashaun & Emediegwu, 2025). While petroleum resources generate over 80% of national export revenue (Omoregie, 2019), they have also contributed significantly to ecological degradation, public health concerns, and the disruptions in local livelihoods, particularly in oil-producing regions such as the Niger Delta (Adione, 2023; Okpebenyo et al., 2023).

In light of growing concerns about environmental impact and social accountability, environmental conservation and corporate social responsibility (CSR) have become increasingly integral to the oil and gas industry’s strategic priorities. This raises the question: to what extent do CSR initiatives contribute meaningfully to environmental conservation, and how are they perceived by the communities most affected? Addressing this question contributes to the literature by critically examining how CSR initiatives in the oil and gas industry align with environmental conservation goals. It deepens the understanding of CSR’s practical impact, particularly in resource-rich but institutionally weak regions and high-risk sectors like oil and gas.

Against this backdrop, environmental stewardship within the sector entails the sustainable management of natural resources and efforts to mitigate the ecological footprint of operations (Ramzan et al., 2024). This includes curbing air and water pollution, lowering greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), protecting natural ecosystems, mitigating climate change, and embedding sustainability across the entire value chain (Onukwulu et al., 2023). The extant literature is limited by geographical context, particularly with respect to the oil and gas industry in lower-income countries like Nigeria. Therefore, this study focuses on CSR and environmental conservation to highlight the situation within the Nigerian oil and gas industry.

In Nigeria, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has increasingly become a strategic approach through which companies, particularly in the oil and gas industry, respond to socio-economic challenges they face in their area of operations (Ebisi et al., 2024). Over time, CSR has evolved from voluntary philanthropic activities to a more structured and strategic approach that includes environmental stewardship as a central pillar (Zervoudi et al., 2025). Globally, CSR frameworks now emphasise environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles, aligning corporate objectives with broader sustainable development goals (SDGs) (Zervoudi et al., 2025; Leena et al., 2023; López-Cabarcos et al., 2025). In Nigeria, however, the implementation of CSR practices often lacks coherence, transparency, and genuine community engagement (Uhumuavbi, 2023). Although regulatory instruments such as the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) Act, Environmental Guidelines and Standards for the Petroleum Industry in Nigeria (EGASPIN), and the Petroleum Industry Act 2021 (PIA) attempt to embed environmental accountability into the operations of oil firms, enforcement remains inconsistent (Duttagupta et al., 2021), while the duplication and overlap of regulator functions remain evident (Adione, 2023). This disconnect contributes to a growing trust deficit between oil and gas companies and host communities (L. Lin, 2021; Gajadhur & Nicolaides, 2022).

Several studies have shown that these oil and gas companies prioritise CSR investments in infrastructure, the award of scholarships, and economic empowerment among other initiatives over ecological restoration and environmental protection (Akporiaye & Webster, 2022; Hassan et al., 2023; Meribe et al., 2021), areas that are arguably more urgent in regions suffering from the cumulative impact of decades-long oil exploration and production (Akporiaye, 2023). This transactional approach undermines the company’s duty of care to the environment and fails to address the root causes of environmental degradation. It rather fuels perceptions that CSR is primarily a tool for public relations, conflict management, or for business continuity (Idemudia, 2017a; Akporiaye & Webster, 2022; Jeremiah et al., 2023), rather than a sincere attempt to promote environmental sustainability. Therefore, this study seeks to explore the interconnection between environmental conservation and corporate social responsibility (CSR) through the lens of local perceptions and corporate practice in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry.

The extant literature has revealed a growing interest in the perceptions of local communities concerning CSR and environmental practices. Scholars such as Mohammed et al. (2022) and Ho et al. (2024) argue that understanding community perceptions is critical to evaluating the effectiveness of CSR programmes. However, the need for corporate social responsibility (CSR) to embrace environmental conservation initiatives has not been adequately explored from the prism of the most impacted stakeholders. This study aims to fill that gap in the literature by providing insights from people who bear the brunt of the negative externalities of the oil and gas companies. It pays particular attention to the socio-ecological consequences of gas flaring, oil spills, and habitat loss, and the extent to which CSR initiatives mitigate or exacerbate these challenges.

The focus on Nigeria is both timely and pertinent. As the largest oil-producing nation in Africa and one of its most populous countries, Nigeria represents a compelling case of a fossil fuel-dependent economy intertwined with persistent environmental injustice (Timidi & Angiamaowei, 2024; Olunusi & Adeboye, 2025). The dynamics of the oil and gas industry reveal the inherent contradictions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in lower-income economy contexts, where global standards confront local socio-political complexities, and corporate environmental commitments frequently fail to achieve their intended impact. By shedding light on the lived experiences of communities in oil-rich regions, this study examines the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a strategic response to environmental degradation in the oil and gas industry, with a focus on stakeholder perceptions and company practices. It contributes a conceptual framework that maps the relationship between actors, their actions, and ecological outcomes. By highlighting the gap between community expectations and corporate interventions, this study offers practical insights to guide CSR policy toward environmental stewardship and sustainable development.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing literature on CSR and environmental conservation, with a particular focus on the oil and gas industry. This is followed by the theoretical framework, which situates the analysis within broader discourses on stakeholder theory and environmental justice theory. Section 3 outlines the research design, data collection methods, and analytical approach. Section 4 presents key findings, while the Discussion Section interprets them in relation to existing knowledge. Finally, Section 6 offers reflections on implications and potential pathways for more effective and environmentally responsible CSR in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. Section 6 also includes theoretical contributions, study limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

The discourse on corporate social responsibility (CSR) has evolved significantly over the past few decades, shifting from voluntary philanthropic acts to more structured and strategic approaches that integrate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles (Herciu, 2021; Ashurov et al., 2024). In the context of the oil and gas industry, one of the most environmentally intensive sectors (Koolwal & Khandelwal, 2019; Galieriková & Materna, 2020), CSR has become a critical area of inquiry, particularly with regard to environmental sustainability (Duttagupta et al., 2021) and community engagement (Emeka-Okoli et al., 2024).

Globally, scholars have examined the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in promoting sustainable environmental practices in the oil and gas industries (Duttagupta et al., 2021; Daraojimba et al., 2023). For instance, Nwoke (2021) argues that CSR initiatives in the oil industry often prioritise reputational concerns over substantive community and ecological benefits. Similarly, Idemudia (2014) critiques the limited impact of CSR in sub-Saharan Africa, highlighting the disjuncture between corporate commitments and community realities. These works point to a recurring theme: while oil and gas companies adopt the language of sustainability, their actions frequently fall short of meaningful environmental stewardship. This sentiment is echoed in studies by Pupovac and Moerman (2022) and Tamuno (2022), which suggest that CSR often masks ongoing corporate environmental irresponsibility.

In Nigeria, the literature reflects a complex and contested corporate social responsibility (CSR) landscape, particularly in oil producing regions such as the Niger Delta. Scholars like Meribe et al. (2021) and Ezeudu (2024) have documented the deep-rooted mistrust between oil companies and host communities. Environmental degradation, manifested through oil spills, gas flaring, and deforestation, remains pervasive despite decades of CSR investments. Akporiaye (2023) goes further to argue that CSR in Nigeria often serves as a palliative way of appeasing host communities without addressing the structural causes of environmental harm such as gas flaring and oil spills.

The burning of fossil fuels, especially gas flaring, is one of the major environmental issues caused by human action that Nigeria’s oil and gas industry faces (Abdulrahman et al., 2015; Olujobi et al., 2022). Gas flaring in the Nigerian oil and gas industry is mainly responsible for the release of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere, contributing to global warming, the weakening of the ozone layer, and climate change (Olujobi et al., 2022). In addition to gas flaring, oil spillage has emerged as another major environmental hazard, presenting enormous adverse impacts in the Niger Delta region due to oil and gas operations (Albert et al., 2019; Soremi, 2020). Between 2015 and March 2021, the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA) recorded 4919 oil spills. Of these, 308 were linked to operational maintenance, 3628 were attributed to sabotage, and 70 remain unclassified, contributing to a total of 235,206 barrels of oil spilled (Morocco-Clarke, 2023). The causes of these spills are multifaceted, including ageing infrastructure, equipment failures, operational accidents, as well as sabotage and theft (Mba et al., 2019; Ezeh et al., 2024).

Beyond the immediate impacts of gas flaring and oil spills, oil and gas exploration activities frequently lead to deforestation, disrupting ecosystems and biodiversity, with severe consequences for climate regulation and the livelihoods of local communities (Andrews et al., 2021; Ejiba et al., 2016). A United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report on an environmental assessment carried out in Ogoniland, Nigeria, concluded that mangrove vegetation cleared during seismic operations takes 25 to 30 years to regenerate completely (UNEP, 2011). Furthermore, deforestation and forest degradation are largely exacerbated by the high incidence of oil spills, oil theft, and artisanal refining activities occurring across the Niger Delta region (Morocco-Clarke, 2023; Ekwugha et al., 2020).

These widespread patterns of environmental disruption highlight the deeper structural issues within the operational frameworks of oil and gas companies. Major oil spills and other mishaps reveal that the business architecture of these companies is fundamentally misaligned with environmental sustainability (Du & Vieira, 2012). As a result, the long-term viability of this model has been increasingly called into question by stakeholders concerned about both environmental and social impacts (Du & Vieira, 2012; Amuyou et al., 2016; Enuoh et al., 2020). Against this backdrop, there is a critical need for oil and gas companies to reconfigure their business processes, prioritising responsible CSR practices that genuinely seek to mitigate the adverse effects of their operations and promote broader social and environmental responsibility (Ejumudo et al., 2012; Emeseh et al., 2010).

2.2. Environmental Conservation

According to a World Bank report of 2021, Nigeria was the seventh highest gas flaring country in the world for the period under review and has consistently ranked among the top seven for nine years, flaring over 64 billion cubic metres of gas for the nine-year period. Nigeria, along with six other nations (Russia, Iraq, Iran, the United States, Algeria, Venezuela), accounted for 65% of global gas flaring (The World Bank, 2021). Nigeria is considered the highest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in Africa through the gas flaring activities from oil and gas companies (Etemire, 2021). These companies, through their processes and products, have substantially contributed to the emission of GHGs, particularly methane and carbon dioxide, into the environment (Grasso, 2019), therefore making a case for them to embrace sustainable practices.

Consequently, the pursuit of sustainable development has garnered increased global attention, highlighting the imperative for industries, particularly those with significant ecological footprints, to integrate environmental conservation into their operational frameworks (Asubiojo et al., 2023). As such, environmental conservation has emerged as a critical issue in the global fight against climate change and ecological instability (Ndasauka, 2024). Conservation involves the collective responsibility of individuals, organisations, and governments to safeguard natural resources and promote ecological sustainability (Kaine & Womenazu, 2022).

Environmental conservation has become a central theme in scholarly discourse on sustainable development, especially in lower-income countries with high environmental vulnerability (Ndasauka, 2024; Sam et al., 2023). In the Nigerian context, particularly within the Niger Delta region, extensive environmental degradation resulting from oil and gas activities has heightened the urgency for sustainable environmental practices (Omokaro, 2024; Sam et al., 2024b; Akeju & Oguntimein, 2023). The release of petroleum hydrocarbons through oil spills, gas flaring, and pipeline leakages has significantly compromised air, water, and soil quality, threatening biodiversity and public health (UNEP, 2011; Ugwu et al., 2021). These environmental hazards, often caused by human error, theft, accidents, and poor operational practices (Onogwu & Lawal, 2024; Henry & Mohammed, 2023; Numbere et al., 2023), disrupt ecosystems and create conditions that are incompatible with healthy living.

Consequently, scholars have emphasised the need for a holistic approach to environmental sustainability that addresses both immediate and structural causes of ecological harm. Azuazu et al. (2023) and Ola et al. (2024) argue that removing pollutants from critical components of the natural environment is essential for restoring ecosystem function and protecting community health. In addition, sustainable resource management is critical for intergenerational equity, particularly in regions where natural resources are heavily exploited without effective replenishment strategies (Oyedokun & Erinoso, 2022).

Biodiversity conservation also features prominently in the literature. Andrei et al. (2014) highlight the importance of incorporating ecological considerations into corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes and environmental policy frameworks. Idemudia (2017b) supports this view, suggesting that community-based approaches to biodiversity protection and environmental restoration can foster local ownership and enhance sustainability outcomes and that issues concerning the preservation of biodiversity in affected communities are too significant to be addressed solely within a framework predominantly shaped by corporate interests. Moreover, environmental conservation is intricately linked to global efforts to combat climate change. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022), Africa remains disproportionately vulnerable to climate-induced risks, due in part to weak institutional capacity and limited infrastructure (Ndasauka, 2024). In this context, proactive conservation strategies are not merely remedial but constitute a forward-looking approach to resilience building and ecological balance.

Overall, the literature reflects a complex and often critical view of CSR’s role in environmental conservation, particularly within Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. It underscores the need for integrated efforts to reverse environmental degradation, protect biodiversity, and build resilience against the negative externalities of oil and gas operations.

2.3. CSR, Environmental Degradation, and the Risk of Greenwashing

The literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR) within the oil and gas industry consistently emphasises its potential to mitigate social and environmental externalities, particularly in resource-rich but institutionally fragile regions (Dzedzemoon & Ferro, 2024; Sam et al., 2024b). In areas such as Nigeria’s Niger Delta, host communities disproportionately suffer the consequences of industrial activities including gas flaring, oil spills, and habitat degradation (Ukhurebor et al., 2023; Suku et al., 2023). As such, community perceptions and lived experiences have become critical indicators for assessing the authenticity and effectiveness of CSR initiatives (Park, 2024; Turker et al., 2023).

These concerns are further complicated by the increasing prevalence of greenwashing, where corporations overstate or misrepresent their environmental efforts to secure reputational advantages without delivering tangible outcomes (Zervoudi et al., 2025). In the oil and gas industry, greenwashing may manifest as the publicising of token environmental projects while core harmful practices, such as gas flaring and poor spill management, persist (Erbuğa & Atağan, 2024). This disjunction raises urgent questions about transparency and accountability in CSR implementation (Okorie, 2024). Greenwashing not only erodes public trust but also intensifies tensions with local communities, who may view CSR efforts as superficial or self-serving (W. L. Lin et al., 2025; Haidar, 2025).

The failure to authentically engage with host communities can have significant consequences. These range from reputational damage and community resistance to operational disruptions and, in extreme cases, legal sanctions or state intervention (Bamidele & Erameh, 2023). Discontent often signals a deeper misalignment between corporate CSR narratives and the lived environmental realities of affected populations (Willness, 2019). When CSR fails to meet local expectations or inadequately addresses ecological harm, it can intensify rather than resolve conflict (Hoelscher & Rustad, 2019; Sam et al., 2024a). Empirical evidence shows that superficial or misaligned CSR interventions can provoke resentment, protest, and, in some cases, acts of sabotage (Jeremiah et al., 2023; Meribe et al., 2021). Sam et al. (2024a) observes that, in contexts such as the Niger Delta, unresolved grievances stemming from ineffective CSR often lead to organised resistance.

Despite this growing body of research, there remains a paucity of studies that explicitly examine how host communities perceive the environmental dimensions of CSR, or how these perceptions shape broader debates on corporate accountability. By foregrounding community voices, this study aims to contribute a grounded perspective on the sustainability and ethical obligations of CSR in resource-rich regions.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

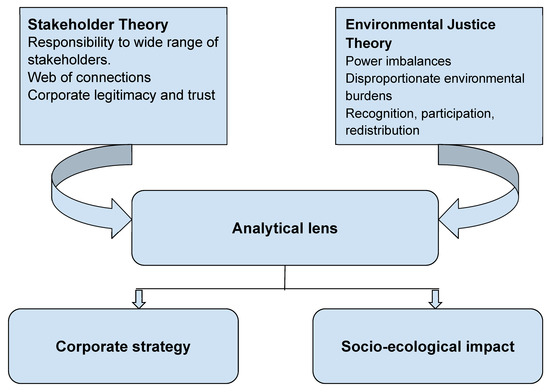

This study draws on two complementary theoretical lenses to frame its analysis: stakeholder theory and environmental justice theory (Figure 1). Combined, these frameworks offer insights into the dynamics of corporate accountability, community perceptions, and environmental equity within Nigeria’s oil and gas industry, enabling a critical analysis of both the intent and impact of CSR practices.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework: stakeholder and environmental justice perspectives.

2.4.1. Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory, as proposed by Freeman (1994), posits that firms bear responsibilities extending beyond the sole pursuit of shareholder value. It emphasises that businesses operate within a complex web of relationships involving diverse stakeholders such as employees, customers, suppliers, local communities, creditors, and society at large. Effective corporate governance, therefore, requires balancing and addressing the interests of these various constituencies, which in turn fosters stronger relationships, enhances corporate reputation, and contributes to long-term organisational performance.

Originating as a theory of organisational management and business ethics, stakeholder theory highlights the moral and ethical dimensions of business operations (Dmytriyev et al., 2021). It aligns closely with principles of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and social contract theory (Amri & Chaibi, 2025), advocating for a values-based approach to managing organisations. This perspective stresses that organisations should not focus exclusively on maximising returns for investors or company owners but should also consider the broader social and environmental impacts of their decisions (Okafor et al., 2022).

From this standpoint, corporate engagement in socially and environmentally responsible initiatives, even those that may not yield immediate financial returns can be strategically beneficial. Such actions are often perceived as valuable by stakeholders and may enhance public trust, legitimacy, and long-term support for the firm (Schroeder et al., 2021; Meribe et al., 2021). As Akinleye and Olaoye (2021) argue, participation in environmental conservation activities that align with stakeholder expectations can significantly strengthen corporate–community relations and contribute to sustainable business practices.

2.4.2. Environmental Justice Theory

Environmental justice provides a critical theoretical framework for understanding how marginalised communities mobilise in response to environmental harms that often arise from unequal power relations and systemic exploitation within the state (Randell & Klein, 2021). It highlights the disproportionate exposure of vulnerable populations, particularly those in resource-rich but politically and economically marginalised regions, to environmental risks and degradation (Figueroa, 2022; Clark & Miles, 2021). Through the lens of environmental justice, such struggles are not only ecological but also deeply rooted in historical patterns of exploitation, inequality, and systemic neglect (Morocco-Clarke, 2023; Miles et al., 2025).

The principles of environmental justice hold particular significance in the context of the Niger Delta. Communities in oil-producing areas suffer the direct consequences of pollution and resource depletion, yet they have limited voice in decision-making processes (Andrews et al., 2021; Nkem et al., 2024). Environmental justice theory challenges the cosmetic nature of many CSR initiatives and calls for a more equitable distribution of environmental benefits and the protection of vulnerable communities from exposure to environmental hazards. It also highlights the importance of recognition, participation, and redistribution, the core dimensions of justice that are often lacking in corporate–community relations in Nigeria (Dedeck, 2022).

We draw on environmental justice theory to better understand stakeholders’ perceptions, specifically those of host community members and the staff of oil and gas companies, regarding their experiences with environmental degradation, and how these struggles shape and influence the dynamics of their relationships.

Together, stakeholder theory and environmental justice theory provide a robust analytical framework for this study. While stakeholder theory explains the strategic dimensions of CSR, environmental justice theory highlights the normative and ethical imperatives for equitable environmental governance. This dual framework allows for a critical exploration of both the intent and the impact of CSR practices in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry.

3. Materials and Methods

This study explores the lived experiences of stakeholders in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry using a phenomenological approach. Phenomenology, a qualitative research method, aims to understand individuals’ experiences (van Manen, 2016; Wilson, 2015). It allows researchers to connect empathetically with participants, which is crucial in understanding complex interactions like corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental conservation (Alase, 2017). Phenomenology was chosen to gain an in-depth understanding of how stakeholders perceive CSR and environmental conservation.

3.1. Selection of Study Participants

Purposive sampling was used to select participants, enabling the researcher to choose individuals likely to provide relevant information. This method is particularly useful for gaining insights from those with specific knowledge or experience related to the research objectives (Sharma, 2017). Participants included oil and gas company staff from departments like Health, Safety, and Environment (HSE), CSR/ESG, and Production Operations. Community participants were key figures such as youth presidents, Community Development Committee chairs, and members of the Petroleum Industry Act 2021 Host Community Development Trust Fund.

To be eligible for inclusion in this study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (1) they must be either residents of a host community or staff members of the oil and gas industry in the Niger Delta; (2) they must have lived in the study setting for a minimum of five years; and (3) for corporate staff, they must be current employees who have worked with the selected companies for at least five years. Participants who met these criteria were purposively selected, as their long-term engagement with the region and direct involvement in corporate operations provided valuable insights for addressing this study’s research objectives.

3.2. Selection of Study Setting

Purposive sampling also guided the selection of this study’s operational locations within the Niger Delta. Akwa Ibom and Rivers States were chosen for their relatively lower security risks compared to other Niger Delta states, which face persistent insecurity (Siloko, 2024; Ajiya, 2022). This study focused on operational sites near urban centres to reduce safety concerns. The aim was not to generalise but to ensure transferability, as covering all Niger Delta states would not necessarily enhance the credibility of the findings.

3.3. Selection of Oil and Gas Companies

This study focused on oil and gas exploration and production companies operating in Akwa Ibom and Rivers States. Companies in these states include ExxonMobil, Shell Petroleum Development Company, Savannah Energy, Total E&P, Addax Petroleum, Universal Energy, Mono-Pulo, Oriental Energy, Network Exploration, Frontier Oil, and Nigerian Agip Exploration (Akpan, 2014; Chijioke et al., 2018). A convenience sampling technique was employed to select five participating companies. While this method limits generalisability due to potential sample bias (Emerson, 2021), it was appropriate given the volatile security situation in the region.

3.4. Data Collection

In-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted with two key stakeholder groups: opinion leaders and residents of host communities as well as staff members of oil and gas companies. A total of 42 interviews were held, with 23 participants from host communities and 19 from the oil and gas companies. Community participants were selected from five local government areas in Rivers and Akwa Ibom states. Participants received an information sheet and signed consent forms before the interviews, which were recorded with their consent, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality.

3.5. Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim using AI technology (Riverside.fm), with corrections and refinements made by the researcher. A second reviewer verified the transcripts for accuracy. Reflexive thematic analysis was employed as the analytical framework, with NVivo (version: 13) software used to assist in coding and categorising data. This approach enabled the researchers to explore patterns and develop conceptual frameworks. NVivo facilitated the extraction of significant information and supported the rigour of the analysis. This study adhered to Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework for thematic analysis and used the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG) for methodological consistency (Braun & Clarke, 2024).

4. Results

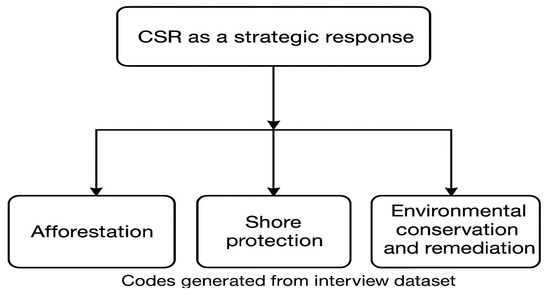

This study set out to explore the extent to which corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry contribute meaningfully to environmental conservation and how these efforts are perceived by stakeholders. Drawing on empirical evidence from qualitative interviews, the findings illuminate a significant shift in stakeholder expectations and conceptualisations of corporate social responsibility (CSR) within Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. The theme “CSR as a Strategic Response,” which emerged through the codes of afforestation, shore protection, and environmental conservation and remediation, reveals how both host community members and corporate actors understand CSR not merely as philanthropy, provision of public goods and services, image management, conflict resolution, and business continuity but as a tool for environmental stewardship and long-term sustainability. While some of the generated codes reflect findings from earlier studies (Azuazu et al., 2023; Ola et al., 2024; Sam et al., 2023), this appears to be the first study to examine them as a strategic response to corporate social responsibility from the standpoint of those most directly impacted. The findings offer practical suggestions for CSR efforts that prioritise environmental conservation.

One central theme, “CSR as a strategic response”, was constructed using three codes generated from the interview dataset: afforestation, shore protection, and environmental conservation and remediation (Figure 2). The researcher examined the participants’ knowledge and perspective between the interconnection between environmental conservation and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Figure 2.

Theme and codes generated from the interview dataset.

The codes generated from the analysis are discussed below, with selected participant quotes used to illustrate key points. Each participant was assigned a unique alphanumeric identifier, with codes prefixed as SMP for staff members and HCP for host community participants. These identifiers combined participant initials and numerical sequencing (e.g., SMP-001, HCP-001) to ensure clear differentiation during analysis. They also allowed the researcher to accurately link interview recordings and field notes to the corresponding participants.

4.1. CSR as a Strategic Response

Participants opined that CSR initiatives should be seen as strategic responses to the environmental issues experienced as a result of the operations of oil and gas companies. Data from these interviews suggested that oil and gas companies in Nigeria are focusing their CSR practices on infrastructural development and economic empowerment of host communities, often neglecting the need to address environmental challenges.

Participants suggested afforestation, shore protection, and environmental conservation and remediation initiatives as CSR projects aimed at environmental restoration and sustainable practices that these companies could undertake in addition to the common philanthropic CSR practices.

4.2. Afforestation

Afforestation emerged as a recurrent code among both host community participants and staff member participants, who identified it as a critical component of environmental management and corporate social responsibility (CSR) within the oil and gas industry. Participants emphasised the need for oil companies to actively engage in tree planting initiatives as a tangible demonstration of their environmental commitments.

Several host community participants expressed concern over the absence of afforestation efforts by oil and gas companies, highlighting both the ecological and symbolic importance of such activities. One participant observed:

If they can plant trees, oil companies are supposed to take that as part of their corporate social responsibilities. Planting trees on the road, by the roadside will also help to conserve the environment, but they have not done that.(HCP-21)

Similarly, another participant argued for immediate action:

There is nothing stopping companies from engaging in afforestation. Let them plant trees around this place. Let them plant it.(HCP-16)

Staff member participants echoed these sentiments, framing afforestation as a practical strategy for mitigating environmental degradation, particularly in areas impacted by gas flaring. As one SMP explained,

If you knock off gas flaring and plant more mangrove trees within the area and grow back the area that has been burnt out by the flare over the years, then that will help the environment to recoup itself.(SMP-13)

Another participant underscored the compatibility of afforestation with ongoing oil and gas operations, suggesting that

Some people are moving to green energy, but you can’t run away from the traditional oil and gas operations. The vision is to while carrying out your operations, protect the environment. Whatever it is, while carrying out your operations, protect the environment, you can plant trees, and other projects that will cushion the effect of the operations on the environment.(SMP-12)

Additionally, afforestation was recognised for its role in carbon sequestration. This indicates a broader awareness among participants of the potential for afforestation to contribute not only to local ecological restoration but also to global climate mitigation efforts. One staff member participant noted the following:

When you have more trees, the trees will also take the carbon, carbon dioxide, that will also reduce the influx of CO2 in the atmosphere.(SMP-5)

4.3. Shore Protection

Participants identified shore protection as one key area to mitigate the environmental damage caused by exploration activities by oil and gas companies. Host community participants highlighted the devastating impact of erosion and ocean surges on coastal communities and emphasised the need for companies to take responsibility through land reclamation efforts:

Due to this (oil and gas) exploration, you have a lot of communities washed away by erosion, by the ocean surging, and there are no efforts to try and reclaim these communities back to the people that inhabited those areas. So we try to see if they can embark on land reclamation for these communities that have been washed away.(HCP-11)

Another participant reinforced this view, identifying shore protection as not only an environmental necessity but also a means of restoring dignity and stability to affected communities.

One of the things (projects) is shore protection of these coastal communities. So if that is done, most of the land that has been taken away or washed away will be reclaimed back to the community. So you have enough land to also stay and also reside in.(HCP-17)

From the perspective of corporate actors, the strategic rationale for shore protection is acknowledged, albeit cautiously. A staff member participant noted the following:

That’s a difficult one, but there are some things that could be done in areas where we have encroachment. The areas that are eroded, we do shore protection. There could be shore protection. Then we also get involved in revegetating some of the areas that have been exposed, we revegetate them.(SMP-11)

4.4. Environmental Conservation and Remediation

Participants highlighted the negative impacts of oil and gas operations on the environment and suggested ways that the impacted areas can be remediated and how these companies can make a conscious effort to conserve the environment as part of their corporate social responsibilities. Community members, in particular, emphasised the importance of conservation initiatives that align with local ecological assets and economic livelihoods. One participant cited the example of a forest area known for its population of white-nosed monkeys, noting its significance as part of a World Bank-sponsored conservation effort. He suggested that oil companies could integrate such ecological zones into their CSR portfolios, expanding them as part of environmental stewardship:

In our community here we used to have what we call a forest for white-nosed monkeys. It’s a World Bank sponsored program. The company can take that, and work on that, to expand it, it stretches up to 200 km2, it’s a long stretch of bush. So you can do that, put in either more monkeys or, you know, pick a place and that’s my thinking of conservation. Then again, you have the negative impact of your operations on the ecosystem. Look for a way to remediate. Either you inject fingerlings, that’s what they do outside (developed economies). Inject fingerlings into the river, the water bodies and that will help people economically because once they grow, people will now go for fishing and they will sell.(HCP-6)

Another host community participant turned to the principle of environmental reciprocity, likening oil drilling to mining, where extraction is expected to be followed by restorative action.

While you are drilling, those places you are removing are supposed to be replaced by something. When you are not operating again, it’s supposed to be replaced. Just like in mining. When you are removing something, you must replace something to protect that area, to avoid earthquakes. Those things are not being done. So the main important thing is to also look at, to avoid earthquakes that occur in other countries, not to occur in this country.(HCP-4)

From the corporate standpoint, staff members also acknowledged the challenges and expectations surrounding environmental remediation, particularly in areas affected by oil spills. While one participant noted that their own operational zone had not experienced spills, they recognised the wider operational burden placed on companies to conduct thorough clean-ups:

In areas that have been impacted by oil spill, though not in my own area of operation, my company, in fact, we have not really recorded oil spillage. But in areas that have had oil spillage in the environment, it’s been a challenge for owners of the company to do proper cleanup. Clean up of the waterways, the farmlands, and the rest of it. So, at least the people can go to the farm again. A lot of communities have been impacted by oil spillage and they can’t go to the farmland again.(SMP-9)

While another blamed the spills on the activities of vandals and oil theft:

….most youths these days go into bunkering, and this bunkering activity is becoming a major concern because most of the environmental impacts come from these unprofessional tap points. And that leads to leakages, leads to impacts, leads to spills, leads to gas emissions and has a devastating effect on the environment.(SMP-2)

5. Discussions

This study set out to explore the extent to which corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry contribute meaningfully to environmental conservation and how these efforts are perceived by host communities. Drawing on empirical evidence from qualitative interviews, the findings illuminate a significant shift in stakeholder expectations and conceptualisations of corporate social responsibility (CSR) within Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. The theme “CSR as a Strategic Response,” which emerged through the codes of afforestation, shore protection, and environmental conservation and remediation, reveals how both host community members and corporate actors understand CSR not merely as philanthropy, the provision of public goods and services, image management, conflict resolution, and business continuity but as a tool for environmental stewardship and long-term sustainability. While some of the generated codes reflect findings from earlier studies (such as Azuazu et al., 2023; Ola et al., 2024; Sam et al., 2023), this appears to be the first study to examine them as a strategic response to corporate social responsibility from the standpoint of those most directly impacted. The findings offer practical suggestions for CSR efforts that prioritise environmental conservation.

The data reveals a strong consensus among participants that CSR in the oil and gas industry should be repositioned from a largely philanthropic gesture to a strategic and integrated response to environmental degradation. This finding aligns with Porter and Kramer’s (2006) shared value framework, which suggests that businesses can generate economic value by identifying and addressing social and environmental problems that intersect with their operations. Participants, especially from host communities, expressed dissatisfaction with the current CSR practices that prioritise infrastructure and economic empowerment projects while neglecting the environmental externalities of oil exploration. This indicates a misalignment between community expectations and corporate priorities and resonates with criticisms in the literature that CSR in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry often reflects a business continuity strategy rather than a genuine commitment to sustainable development (Tamuno, 2022; Tanam, 2023; Enuoh & Enuoh, 2023).

For CSR to be effective and sustainable, it must address the most pressing concerns of affected stakeholders (Awa et al., 2024), in this case, the environmental impacts of oil and gas operations. The data suggests that host community members view the environment not only as a natural resource base but also as a source of livelihood, identity, and cultural heritage (Siloko, 2024; Amadi, 2022). Environmental degradation, therefore, is experienced as both ecological loss and socio-economic displacement. Consequently, the expectation is that oil companies must go beyond surface-level interventions and adopt robust environmental strategies that encompass conservation and remediation.

Afforestation emerged as a dominant code in the data, with participants from both staff and host community categories articulating it as a practical, visible, and ecologically meaningful form of CSR in the oil and gas industry capable of reversing the environmental effects of oil exploration and production.

The emphasis placed by participants on afforestation aligns with the broader literature highlighting the role of reforestation and ecosystem rehabilitation in mitigating the environmental consequences of extractive industries (Numbere, 2021; Sam et al., 2023). In particular, afforestation was seen as a viable response to longstanding issues such as gas flaring and land degradation. Staff participants linked afforestation efforts directly to the restoration of lands affected by flaring, mirroring calls in academic discourse for oil companies to invest in CSR programmes that go beyond prioritising high-visibility projects like road construction or scholarship programmes over less visible, long-term environmental interventions. According to Meribe et al. (2021), many CSR initiatives in the Niger Delta region have historically focused on ad hoc infrastructural donations rather than long-term environmental restoration.

Host community participants perceived the absence of afforestation initiatives as a failure of oil companies to meet their CSR obligations. This perception reinforces earlier studies suggesting that visible and long-term interventions like tree planting may carry greater legitimacy in the eyes of local stakeholders compared to more abstract CSR reporting mechanisms (Odera et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2024). The insistence by host community participants that “there is nothing stopping companies from engaging in afforestation” reflects a broader frustration with the perceived disconnect between corporate rhetoric and environmental realities on the ground (Supran & Oreskes, 2021).

From a sustainability perspective, the recognition by participants of the carbon sequestration potential of trees further situates afforestation within the discourse on climate change mitigation. As one staff member articulated, trees can “take the carbon… that will also reduce the influx of CO2 in the atmosphere”. This aligns with scholarly evidence on the role of afforestation in absorbing greenhouse gases and enhancing climate resilience in oil-producing regions (Sam et al., 2023; Numbere, 2021; Akani et al., 2022).

Moreover, the discussion of afforestation by both community members and staff suggests a shared environmental consciousness that could serve as a foundation for co-designed sustainability initiatives. Scholars have argued that such alignment across stakeholder groups is critical for fostering inclusive and durable environmental governance models in resource-rich regions (Debski, 2023; Barkley et al., 2024; Gooding et al., 2025).

The findings suggest that oil and gas companies operating in the region may enhance their legitimacy and improve environmental performance and community relations by integrating afforestation more substantively into their CSR strategies. As Alam and Islam (2021) and Muralidhar et al. (2024) posits, CSR programmes with such layered benefits can simultaneously improve corporate reputation and contribute to community development, making them more sustainable and effective. Collectively, the responses suggest a shared perception across participant groups that afforestation is both an environmentally responsible and socially expected action for oil companies operating in the region.

Another significant code was the need for shore protection and land reclamation in coastal communities affected by oil exploration. Host community participants highlighted the existential threats posed by erosion and ocean surges, conditions they linked to oil operations. Their narratives indicate a critical demand for CSR to be reoriented toward environmental security and infrastructural resilience. These findings reinforce existing scholarship that identifies coastal erosion as a pressing environmental and human rights issue in the Niger Delta (Siloko, 2024; Elisha & Felix, 2021).

Shoreline erosion in the Niger Delta has long been linked to industrial activities and rising sea levels (Folorunsho et al., 2023; Arausi et al., 2024). Therefore, the desire for land reclamation also speaks to deeper issues of identity, belonging, and justice. For many participants, CSR is not only about physical development but about the restoration of spaces integral to their cultural and economic lives. As one participant noted, shore protection would allow displaced families to “reside in” and “stay” in their ancestral homes. This observation underscores the interconnection between environmental conservation and social stability (Hariram et al., 2023; Siloko, 2024; Ye et al., 2022), suggesting that CSR initiatives should adopt a more holistic and community-informed approach to environmental remediation.

From the corporate perspective, there was a cautious acknowledgment of the feasibility of such projects. This hesitance reflects institutional reluctance to accept responsibility for such large-scale ecological interventions. However, adopting shore protection as a CSR strategy can enhance resilience, reduce future liability, and demonstrate commitment to community well-being, especially in light of increasing scrutiny of corporate environmental footprints. As Bian et al. (2025) assert, environmental CSR that directly addresses community vulnerabilities is more likely to generate trust and long-term corporate–community cooperation.

The third code, environmental conservation and remediation, illustrates the multifaceted expectations that communities have of CSR. The findings from this study reveal that environmental conservation and remediation are widely regarded by both community members and corporate staff as critical components of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. Participants consistently articulated expectations that oil companies should not only mitigate the environmental harm caused by their operations but also engage proactively in restorative and conservation-oriented activities. This perspective aligns with the polluter pays principle widely endorsed in environmental governance frameworks (OECD, 2008).

Examples such as restocking rivers with fingerlings or rehabilitating forest reserves illustrate an emerging vision of CSR as not only compensatory but regenerative. These proposals go beyond surface-level compliance and reflect an aspiration for CSR to contribute meaningfully to the ecological and economic recovery of impacted regions. The emphasis on conservation efforts that align with local resources such as forests (Sattayapanich et al., 2022) or aquatic life (Bunkar et al., 2022) also highlights the importance of contextualised CSR where corporate initiatives are tailored to the specific environmental and cultural realities of the communities in which they operate. This resonates with the work of Egbon et al. (2024), who concluded that CSR initiatives are inadequate when they fail to address the environmental impacts of extractive activities on host communities.

The notion of “injecting fingerlings” into water bodies, for instance, presents a low-cost, high-impact solution that simultaneously restores biodiversity and supports local fishing livelihoods. Such practices are not only environmentally responsible but economically strategic, offering oil firms an opportunity to enhance their social licence to operate. A particularly striking narrative compared oil drilling to mining, emphasising that extracted areas should be restored post-operation. This reflects the “no net loss” principle widely endorsed in environmental governance, which suggests that economic development should not result in a net reduction in ecological integrity (Sam et al., 2023; Michael et al., 2023). Furthermore, the comparison to higher-income economies where injecting fingerlings and rehabilitating land is standard underscores a transnational awareness of what responsible corporate behaviour should look like. This aligns with the findings of Ebisi et al. (2024), which observed that, while an increasing number of companies are prioritising the environmental and social aspects of CSR, this shift has not yet been seen in the Nigerian oil and gas industry.

The white-nose monkey (Cercopithecus sclateri), referenced in this study by participants, is the only monkey species endemic to Nigeria and is classified as an endangered primate (Jacob & Eniang, 2023; Ezeani et al., 2023). The call for corporations to support efforts in conserving existing forest reserves and revive the disappearing population of wildlife echoes well within the literature (Sifile et al., 2021; Baroth & Mathur, 2019; Çakıroğlu & Oner, 2021). These views highlight that people see CSR not only as a way for companies to make up for environmental damage but also as a chance to support long-term sustainability and build community goodwill.

Interestingly, staff members corroborated these concerns, albeit with more institutional constraints. The mention of challenges related to oil spill cleanup indicates an awareness of reputational and operational risks but also suggests a gap in capacity or willpower to undertake large-scale remediation. This tension between awareness and action reflects broader structural issues in CSR implementation, including regulatory weakness, corruption, and lack of enforcement, which scholars like Uhumuavbi (2023) and Noah et al. (2021) have extensively critiqued.

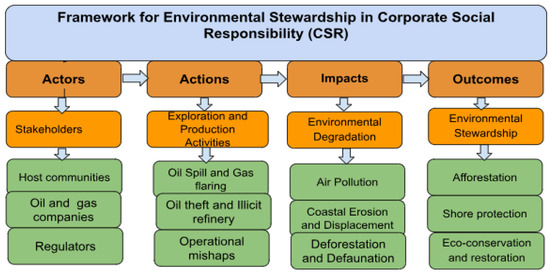

To further illustrate the findings of this study, a visual framework synthesising findings from both the literature and fieldwork was developed. The framework illustrates the interconnected roles and responsibilities of key actors within the oil and gas industry, highlighting the pathways through which industrial activities lead to environmental impacts and the responses that can foster sustainability. Structured around four main components; actors (industry stakeholders), actions (exploration and production activities), impacts (environmental degradation), and outcomes (environmental stewardship), the framework (see Figure 3) offers a practical lens for understanding the environmental implications of sector operations and the subsequent responses aimed at promoting ecological sustainability.

Figure 3.

Framework for environmental stewardship in corporate social responsibility (CSR).

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practice and Policy Implications

The overall theme that CSR should function as a strategic response to environmental degradation is supported by the evidence. Participants were not demanding compensation; they were calling for a reconceptualisation of CSR as an ecological contract between corporations and communities. This has strategic implications for oil companies operating in Nigeria.

This shift requires companies to embed environmental risk mitigation into the core of their CSR planning, rather than treating it as an add-on or reaction to crises. It also necessitates greater dialogue with communities, who, as this study has shown, possess deep and practical knowledge of their environment and clear visions for sustainable futures.

Equally, host communities can play a more active role in shaping meaningful CSR outcomes by strengthening their engagement mechanisms with oil and gas companies, ensuring that local environmental concerns are clearly articulated and addressed. Investing in environmental literacy and advocacy empowers communities to understand the ecological impact of industrial activities and to push for more accountable, conservation-focused interventions.

From a policy standpoint, these findings call for stronger environmental regulations and monitoring frameworks that mandate remediation and conservation as part of CSR obligations. This call becomes more imminent now that the Petroleum Industry Act 2021 (PIA) is operational. Section 240 of the Act mandates that every settlor contribute 3% of their actual annual operating expenditure from the preceding financial year in upstream petroleum operations to the development of the host communities. Under the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), a “settlor” is defined as any party holding an interest in a Petroleum Prospecting Licence (PPL) or Petroleum Mining Lease (PML) whose operational area is situated within or connected to a host community. The importance of this is that oil and gas companies in Nigeria will have to rethink their CSR obligations by focusing on environmental CSR initiatives, while the host community trust in charge of the 3% mandated by law will focus on initiatives that will improve their quality of life and well-being.

To operationalise these findings, oil companies should institutionalise environmental CSR units with clearly defined mandates, allocate significant budgetary resources toward ecological restoration, and engage communities in the co-design of interventions. Policies should be guided by robust environmental impact assessments and informed by local ecological knowledge.

6.2. Theoretical Application

This study extends the scope of stakeholder theory by incorporating the ethical perspectives offered by environmental justice theory. It demonstrates that stakeholders, particularly those in marginalised host communities, are not only economic actors but also rights holders whose concerns include fairness, recognition, and environmental protection. By doing so, this study challenges the business-centred framing of CSR and calls for more ethically grounded, justice-oriented corporate practices in ecologically vulnerable regions that meaningfully address the longstanding social and environmental injustices associated with their operations.

6.3. Recommendation

This study highlights a significant underutilisation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a tool for environmental conservation in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. Findings reveal a conspicuous absence of CSR initiatives explicitly aimed at restoring or giving back to the physical environment. Community participants, in particular, advocated for a reconceptualisation of CSR, not merely as a social contract but as an ecological one between corporations and host communities.

To move beyond superficial interventions, CSR strategies should be reframed from transactional, short-term gestures to long-term commitments rooted in ecological stewardship. Initiatives such as afforestation, shoreline protection, and ecological restoration are not only essential for environmental sustainability but also serve to strengthen community resilience and enhance corporate legitimacy. Ultimately, CSR policies and practices in the oil and gas industry should be realigned to prioritise environmental conservation as a central objective, ensuring that corporate accountability reflects the scale and urgency of ecological degradation in the Niger Delta.

6.4. Limitations and Future Studies

While the findings from this study offer valuable insights into the intersection of CSR and environmental conservation within Nigeria’s oil and gas industry, their generalisability may be limited by the unique socio-political and environmental dynamics of the Niger Delta. Additionally, this study’s qualitative approach, while well-suited for capturing nuanced stakeholder perspectives, may not fully capture the breadth or statistical strength of CSR and environmental impact relationships. Future research could employ quantitative or mixed-method approaches to measure the effectiveness of specific CSR interventions across larger samples. Cross-national comparative studies would also be beneficial in examining how CSR practices in similar resource-rich regions respond to environmental challenges and stakeholder expectations within differing institutional and regulatory contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.E. and Y.G.; methodology, E.A.E., Y.G. and Z.A.S.; software, EEA; validation, E.A.E.; resources, E.A.E.; data curation, E.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.E.; writing—review and editing, E.A.E., Y.G. and Z.A.S.; visualization, E.A.E.; supervision, Y.G. and Z.A.S.; project administration, E.A.E.; funding acquisition, E.A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research protocol was approved in accordance with Teesside University International Business School regulations. Ethical oversight was provided by Teesside University Research Ethics sub-Committee (SRESC), which adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (protocol code 2023-Nov-16762-Ebisi and date 23 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Inquiries on data availability can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdulrahman, A. O., Huisingh, D., & Hafkamp, W. (2015). Sustainability improvements in Egypt’s oil & gas industry by implementation of flare gas recovery. Journal of Cleaner Production, 98, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Adione, N. M. A. (2023). An environmental conservation approach to handling oil and gas in Nigeria: An assessment of legal framework. Igwebuike Journal: An African Journal of Arts & Humanities, 9(3), 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F., Saeed, Q., Shah, S. M. U., Gondal, M. A., & Mumtaz, S. (2022). Environmental sustainability: Challenges and approaches. In Natural resources conservation and advances for sustainability (pp. 243–270). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Ajiya, M. (2022). The rise of non-state actors in Nigeria’s Niger-delta region, their unending clamour for secession and a threat to national security. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4319403 (accessed on 31 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Akani, G. C., Amuzie, C. C., Alawa, G. N., Nioking, A., & Belema, R. (2022). Factors militating against biodiversity conservation in the Niger Delta, Nigeria: The way out. In Biodiversity in Africa: Potentials, threats and conservation (pp. 573–600). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Akeju, F. B., & Oguntimein, G. B. (2023). Environmental impact of oil exploration in Nigeria: A case study of Nembe Local Government. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science, 8(9), 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinleye, M. J., & Olaoye, C. O. (2021). Community development cost and financial performance of oil and gas firms in Nigeria. KIU Interdisciplinary Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(3), 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwumiju, A. S., Adelodun, A. A., & Ogundeji, S. E. (2020). Geospatial assessment of oil spill pollution in the Niger Delta of Nigeria: An evidence-based evaluation of causes and potential remedies. Environmental Pollution, 267, 115545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, P. (2014). Oil exploration and security challenges in the Niger-Delta Region: A case of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 4(2), 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Akporiaye, A. (2023). Evaluating the effectiveness of oil companies’ corporate social responsibility (CSR). The Extractive Industries and Society, 13, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akporiaye, A., & Webster, D. G. (2022). Social license and CSR in extractive industries: A failed approach to governance. Global Studies Quarterly, 2(3), ksac041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. S., & Islam, K. Z. (2021). Examining the role of environmental corporate social responsibility in building green corporate image and green competitive advantage. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 6(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alase, A. (2017). The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 5(2), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, O., Amaratunga, D., & Haigh, R. (2019, July 14–18). An investigation into root causes of sabotage and vandalism of pipes: A major environmental hazard in Niger Delta, Nigeria. ASCENT Festival 2019: International Conference on Capacity Building for Research and Innovation in Disaster Resilience (pp. 22–37), Colombo, Sri Lanka. [Google Scholar]

- Amadi, L. (2022). Natural resource (in)justice, conflict and transition challenges in Africa: Lessons from the Niger Delta. Conflict Trends, 2022(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amri, O., & Chaibi, H. (2025). The moderating role of tax avoidance on CSR and stock price volatility for oil and gas firms. EuroMed Journal of Business, 20(1), 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuyou, U., Nlerum, F. E., Akpan, T. T., & Uduak, C. A. (2016). International oil companies’ corporate social responsibility failure as a factor of conflicts in the Niger-Delta area of Nigeria. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, 4(11), 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, J., Panait, M., & Ene, C. (2014, November 6–7). Environmental protection between social responsibility, green investments and cultural values. 3rd International Conference Competitiveness of Agro-Food and Environmental Economy (pp. 2–8), Bucharest, Romania. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, N., Bennett, N. J., Le Billon, P., Green, S. J., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Amongin, S., Gray, N. J., & Sumaila, U. R. (2021). Oil, fisheries and coastal communities: A review of impacts on the environment, livelihoods, space and governance. Energy Research & Social Science, 75, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animashaun, J., & Emediegwu, L. E. (2025). Is there a subnational resource curse? Evidence from households in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Resources Policy, 101, 105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arausi, R. E., Clark, E. V., & Ikenga, F. A. (2024). Oil production and climate change in the Niger Delta region: Synergic implication and adaptation. Journal of Public Administration, Finance & Law, 33, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ashurov, S., Musse, O. S. H., & Abdelhak, T. (2024). Evaluating corporate social responsibility in achieving sustainable development and social welfare. BRICS Journal of Economics, 5(2), 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asubiojo, A. O., Dagunduro, M. E., & Falana, G. A. (2023). Environmental conservation cost and corporate performance of quarry companies in Nigeria: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 7(8), 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, H. O., Etim, W., & Ogbonda, E. (2024). Stakeholders, stakeholder theory and corporate social responsibility (CSR). International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 9(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuazu, I. N., Sam, K., Campo, P., & Coulon, F. (2023). Challenges and opportunities for low-carbon remediation in the Niger Delta: Towards sustainable environmental management. Science of the Total Environment, 900, 165739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamidele, S., & Erameh, N. I. (2023). Environmental degradation and sustainable peace dialogue in the Niger delta region of Nigeria. Resources Policy, 80, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, L., Chivers, C. A., Short, C., & Bloxham, H. (2024). Principles for delivering transformative co-design methodologies with multiple stakeholders for achieving nature recovery in England. Area, 56(4), e12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroth, A., & Mathur, V. B. (2019). Wildlife conservation through corporate social responsibility initiatives in India. Current Science, 117(3), 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L., Xiao, Y., & Robert, J. (2025). Evolving corporate social responsibility practices and their impact on social conflict. The Extractive Industries and Society, 21, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2024). Supporting best practice in reflexive thematic analysis reporting in Palliative Medicine: A review of published research and introduction to the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG). Palliative Medicine, 38(6), 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkar, K., Prakash, S., Ramasubramanian, V., Krishnan, M., & Kumar, N. R. (2022). Economic efficiency analysis of fish farming in Bharatpur District, Rajasthan: A corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative. Indian Journal of Fisheries, 69(4), 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chijioke, B., Ebong, I. B., & Ufomba, H. (2018). The Impact of oil exploration and environmental degradation in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: A study of oil producing communities in Akwa Ibom state. Global Journal of Human Social Science, 18(3), 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. S., & Miles, M. L. (2021). Assessing the integration of environmental justice and sustainability in practice: A review of the literature. Sustainability, 13(20), 11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakıroğlu, H., & Oner, Y. (2021). Adding a contribution to natural and environmental approach by corporate social responsibility for the Turkish defense industry: A corporate framework for wildlife conservation in biodiversity hotspots of Turkey. Journal of Wildlife and Biodiversity, 5(3), 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Daraojimba, C., Banso, A. A., Ofonagoro, K. A., Olurin, J. O., Ayodeji, S. A., Ehiaguina, V. E., & Ndiwe, T. C. (2023). Major corporations and environmental advocacy: Efforts in reducing environmental impact in oil exploration. Engineering Heritage Journal (GWK), 7(1), 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Debski, J. A. (2023). An effective multi-stakeholder strategy for environmental sustainability in oil and gas-producing areas [Ph.D. thesis, Robert Gordon University]. [Google Scholar]

- Dedeck, D. (2022). “Holding course” towards environmental injustice: An explorative analysis of the environmental injustices in the decision-making process of the 9th dredging of the Elbe River in Hamburg, Germany [Master’s thesis, Lund University]. [Google Scholar]

- Dmytriyev, S. D., Freeman, R. E., & Hörisch, J. (2021). The relationship between stakeholder theory and corporate social responsibility: Differences, similarities, and implications for social issues in management. Journal of Management Studies, 58(6), 1441–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsilva, J., Usmani, F. Z. A., & Shaikh, M. I. (2025). Exploring human social responsibility for promoting climate change: An analysis of developed and developing countries. In Climate change and social responsibility (pp. 165–183). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S., & Vieira, E. T. (2012). Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights from oil companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttagupta, A., Islam, M., Hosseinabad, E. R., & Zaman, M. A. U. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A perspective from the oil and gas industry. Journal of Nature, Science & Technology, 2, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dzedzemoon, D. P., & Ferro, R. D. M. (2024). Oil exploitation in the Niger delta: A case study of environmental costs and responsibilities. European Journal of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, 2(3), 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebisi, E. A., Guo, Y., & Soomro, Z. A. (2024). Determinants and factors influencing corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices in the Nigeria oil and gas industry: A systematic review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 22(3), 1470–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbon, O., Nwoke, U., & Agbaitoro, G. (2024). Corporate social responsibility practices in the Nigerian oil industry: New legal direction and the implications for reporting. In Corporate social responsibility disclosure in developing and emerging economies: Institutional, governance and regulatory issues (pp. 3–20). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ejiba, I. U., Onya, S. C., & Adams, O. (2016). Impact of oil pollution on livelihoods: Evidence from the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Journal of Scientific Research & Reports, 12(5), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ejumudo, K., Edo, Z. O., Avweromre, L., & Sagay, J. (2012). Environmental issues and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Nigeria Niger Delta region: The need for a pragmatic approach. Journal of Social Science and Public Policy, 4(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ekwugha, U. E., Moses, O., Akinleye, O. A., & Monday, B. G. (2020). Deforestation and environmental degradation in the Niger Delta—A case study of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. International Research Journal of Advanced Engineering and Science, 5(4), 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Elisha, O. D., & Felix, M. J. (2021). Destruction of coastal ecosystems and the vicious cycle of poverty in Niger Delta Region. Journal of Global Agriculture and Ecology, 11(2), 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Emeka-Okoli, S., Nwankwo, T. C., Otonnah, C. A., & Nwankwo, E. E. (2024). Corporate governance and CSR for sustainability in oil and gas: Trends, challenges, and best practices: A review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(3), 078–090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R. W. (2021). Convenience sampling revisited: Embracing its limitations through thoughtful study design. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 115(1), 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Emeseh, E., Ako, R., Okonmah, P., & Obokoh, L. O. (2010). Corporations, CSR and self regulation: What lessons from the global financial crisis? German Law Journal, 11(2), 230–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enuoh, R. O., & Enuoh, O. O. O. (2023). Corporate social responsibility and social license to operate: Exploring activities of oil multinationals in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Journal of Resources Development and Management, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Enuoh, R. O., Pepple, G. J., & Iheanacho MaryJoan Ugboaku, E. E. O. (2020). Communities’ perception and expectations of CSR: Implication for corporate-community relations. Communities, 12(18), 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Erbuğa, G. S., & Atağan, G. (2024). The ugly truth behind shell PLC: Reaping record profit by greenwashing. International Journal of Contemporary Economics and Administrative Sciences, 14(2), 854–875. [Google Scholar]

- Etemire, U. (2021). The future of climate change litigation in Nigeria: COPW v NNPC in the spotlight. Carbon and Climate Law Review, 15(2), 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeani, E. U., Udofia, G. E., & Orji, C. (2023). Towards sustainable conservation of biodiversity and endangered species in Nigeria. Environmental Review, 9(1). [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh, C. C., Onyema, V. O., Obi, C. J., & Moneke, A. N. (2024). A systematic review of the impacts of oil spillage on residents of oil-producing communities in Nigeria. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31(24), 34761–34786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeudu, M. J. (2024). Oil transnational corporations and the legacy of corporate-community conflicts: The case of SEEPCO in Nigeria. Law and Development Review, 17(1), 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, R. M. (2022). Environmental justice. In The Routledge companion to environmental ethics (pp. 767–782). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Folorunsho, R., Salami, M., Ayinde, A., & Gyuk, N. (2023). The salient issues of coastal hazards and disasters in Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Protection, 14(5), 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1994). The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(4), 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajadhur, R., & Nicolaides, A. (2022). A reflection on corporate social responsibility in Africa contrasted with the UAE and some Asian Nations. Athens Journal of Law, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galieriková, A., & Materna, M. (2020). World seaborne trade with oil: One of main causes for oil spills? Transportation Research Procedia, 44, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, L., Knox, D., Boxall, E., Phillips, R., Simpson, T., Nordmoen, C., Upton, R., & Shepley, A. (2025). Ecological citizenship and the co-design of inclusive and resilient pathways for sustainable transitions. Sustainability, 17(8), 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M. (2019). Oily politics: A critical assessment of the oil and gas industry’s contribution to climate change. Energy Research & Social Science, 50, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Haidar, M. I. (2025). Does societal trust reduce greenwashing? international evidence. Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(3), 3400–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariram, N. P., Mekha, K. B., Suganthan, V., & Sudhakar, K. (2023). Sustainalism: An integrated socio-economic-environmental model to address sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability, 15(13), 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q. M., Khudir, I. M., & San Olawuyi, D. S. (2023). Regulating corporate social responsibility in energy and extractive industries: The case of international oil companies in a developing country. Resources Policy, 83, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A., & Mohammed, S. U. (2023). Oil pipelines vandalism and oil theft: Security threat to Nigerian economy and environment. Journal of Environmental Law & Policy, 3, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Herciu, M. F. (2021). The evolution of corporate social responsibility and the impact on the organizations. Ovidius University Annals, Series Economic Sciences, 21(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]