The Impact of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Resilience—An Exploratory Case Study Based on Tesla

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How is organizational resilience formed when enterprises perform SCSR?

- What are the structural dimensions and content system of organizational resilience based on Tesla’s practices?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Organizational Resilience

2.2. SCSR

2.3. SCSR and Organizational Resilience

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Case Selection

- Organizational resilience: Tesla demonstrates notable strength in organizational resilience, as evidenced by the company’s high industry representativeness, deep global influence, and rich experience in crisis response. For instance, in the face of supply chain disruptions, production capacity decline, and even factory shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory acted expeditiously to ensure normal logistics operations and efficiently promoted the resumption of the industrial chain. This contributed to the swift recovery of the automobile industry and injected substantial “kinetic energy” into the regional economy, demonstrating the company’s resiliency and adaptability. Tesla’s flexible organizational structure and highly adaptable corporate culture allows it to respond rapidly to changes in the market and technological advancements within the industry, continuously innovate, and retain its competitive advantage, thus providing a compelling context for the study of organizational resilience.

- SCSR practices: Tesla adheres to more conventional SCSR practices. Since its inception, Tesla has been committed to the development and sales of environmentally friendly electric vehicles, energy storage systems, and solar energy products. The company aims to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy and is dedicated to promoting technology, management, and product upgrades in the new energy automobile industry. In alignment with its founding mission of “making the world a better place”, Tesla has been at the forefront of efforts to advance energy transformation, environmental stewardship, and social responsibility. It has actively engaged in numerous environmental protection initiatives and charitable endeavors, underscoring its commitment to sustainability and CSR. Tesla’s corporate culture is defined by a set of values that emphasize hard work, passion, and enjoyment in one’s work. The creation of a positive work environment is not merely a slogan; it is a responsibility that extends to every employee and to the wider society.

3.3. Data Collection

- Official Website: Approximately 22,000 words are collected from the information on vehicles and energy released by Tesla on its homepage. Additionally, approximately 204,000 words are obtained from the Chinese and English texts of Tesla’s official information website.

- Company Reports: Approximately 163,000 words are obtained from the 2018 to 2023 Impact Reports and other corporate governance documents, including the Corporate Governance Guidelines, Code of Business Ethics, and other relevant materials, which are translated into English.

- Press Materials: A total of 38,000 words are collected from several sources, such as Baidu Encyclopedia, Sohu, NetEase, and People’s Daily Online.

- Literature: Approximately 23,000 words are obtained after sorting 11 relevant documents from CNKI.

- Other Materials: A further 13,000 words are obtained from several other sources, including Hexun.com, Pescadores.com, Oriental Fortune.com, and Sina Finance.

4. Results

4.1. Open Coding

4.2. Axial Coding

4.3. Selective Coding

4.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

4.5. Theoretical Finding

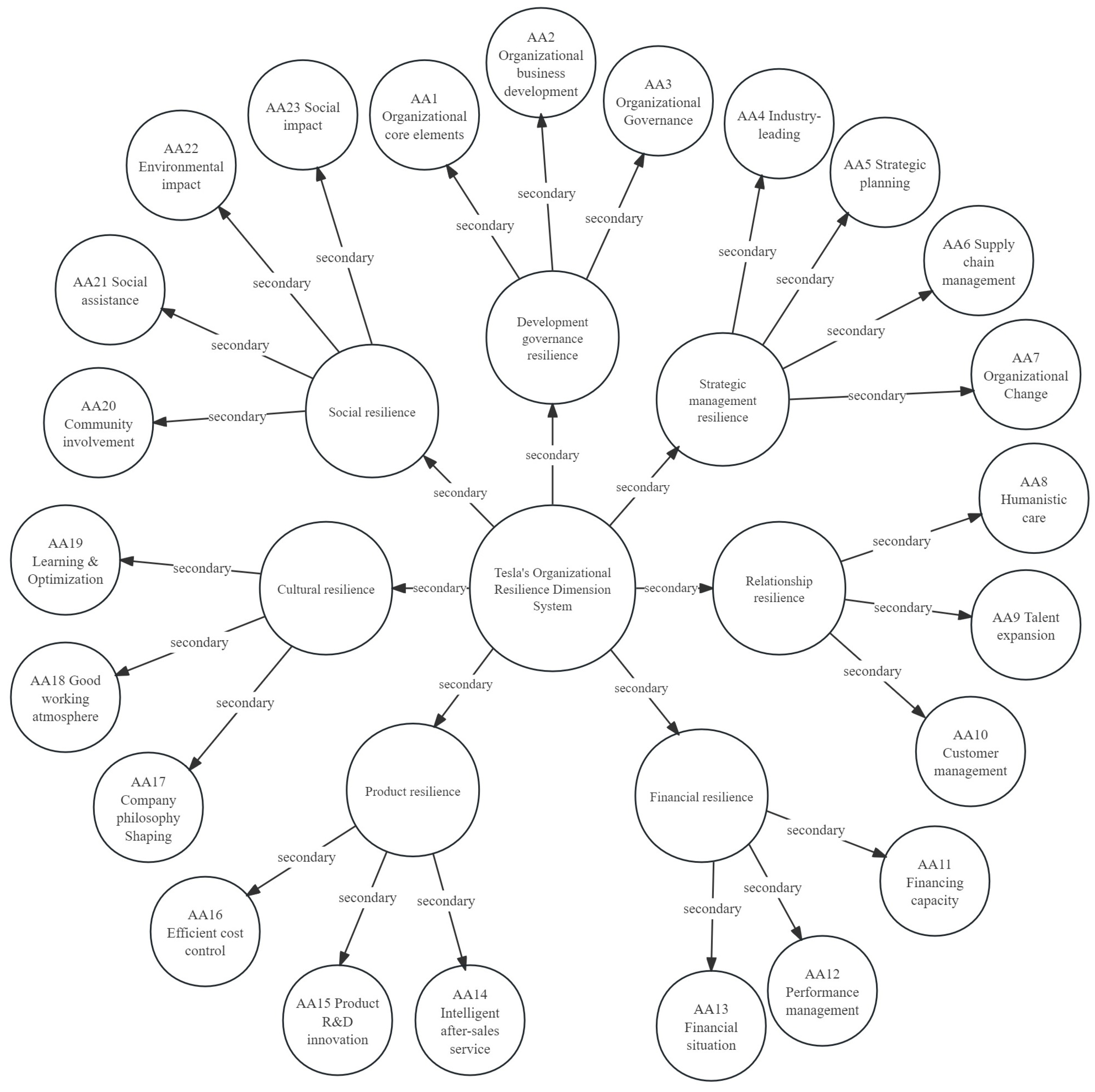

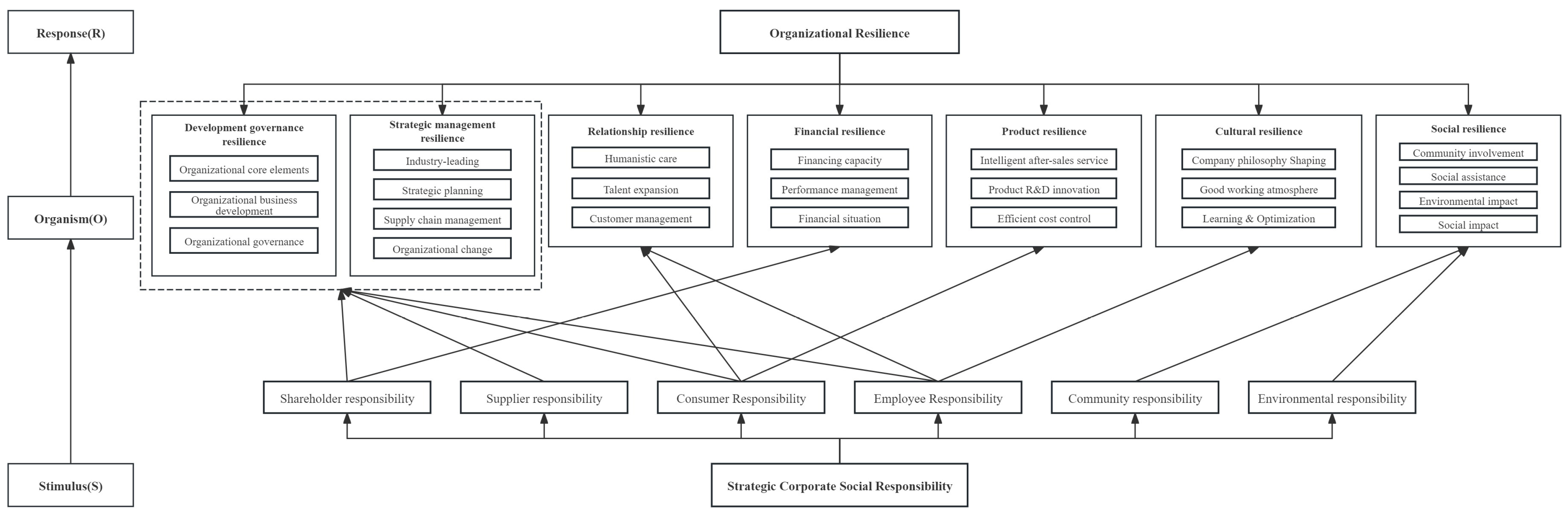

4.5.1. Model Framework Construction

4.5.2. Model Logic Structure

- Influencing factors: shareholder, supplier, consumer, employee, community, and environmental responsibilities;

- Influencing receptors: development governance, strategic management, relationship, financial, product, cultural, and social resilience;

- Influencing outcomes: organizational resilience.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Organizational Resilience Dimensions

- Development governance resilience

- Strategic management resilience

- Relationship resilience

- Financial resilience

- Product resilience

- Cultural resilience

- Social resilience

5.2. The Impact of SCSR on Organizational Resilience

6. Conclusions

- Dimensions of Organizational Resilience

- 2.

- Systematic construction of a theoretical model of the impact of strategic corporate social responsibility on organizational resilience

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akgün, A. E., & Keskin, H. (2014). Organizational resilience capacity and firm product innovativeness and performance. International Journal of Production Research, 52(23), 6918–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeanu, Ş. D., Vintilă, G., & Gherghina, C. Ş. (2017). Approaches on correlation between board of directors and risk management in resilient economies. Sustainability, 9(2), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, M., & Watts, G. S. (2003). Selling to socially responsible consumers: Competition and the private provision of public goods. Journal of Economics Management Strategy, 12(3), 419–445. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P., & DesJardine, M. R. (2014). Business sustainability: It is about time. Strategic Organization, 12(1), 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, P. D. (2001). Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. Journal of Economics Management Strategy, 10(1), 7–45. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, M. A., & Kahn, W. A. (2019). Group resilience: The place and meaning of relational pauses. Organization Studies, 40(9), 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S. S. (2010). Exploring the concept of strategic corporate social responsibility for an integrated perspective. European Business Review, 22(1), 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y., & Qiu, H. (2000). The social capital of enterprises and its effects. Chinese Social Sciences, 2(2), 87–99, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Bruyaka, O., Zeitzmann, K. H., & Chalamon, I. (2013). Strategic corporate social responsibility and orphan drug development: Insights from the US and the EU biopharmaceutical industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(1), 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L., & Logsdon, J. M. (1996). How corporate social responsibility pays off. Long Range Planning, 29(4), 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., Friedman, Y., & Tishler, A. (2013). Cultivating a resilient top management team: The importance of relational connections and strategic decision comprehensiveness. Safety Science, 51(1), 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A., & Areal, N. (2016). Great places to work®: Resilience in times of crisis. Human Resource Management, 55(3), 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. (1999). The idea and method of grounded theory. Educational Research and Experiment, (4), 58–63, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, D., Duan, S., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The power of harmony: The impact of labor relations atmosphere on organizational resilience. Foreign Economics & Management, 45(1), 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L., Eden, L., & Beamish, P. W. (2017). Caught in the crossfire: Dimensions of vulnerability and foreign multinationals’ exit from war-afflicted countries. Strategic Management Journal, 38(7), 1478–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M., Bansal, P., & Yang, Y. (2019). Bouncing back: Building resilience through social and environmental practices in the context of the 2008 global financial crisis. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S., Raetze, S., & Scheuch, I. (2020). The role of diversity in organizational resilience: A theoretical framework. Business Research, 13(2), 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, T. (2019). Developing a culture of organizational resilience. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 16(10), 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J. H., Cameron, K., Lim, S., & Rivas, V. (2006). Relationships, layoffs, and organizational resilience: Airline industry responses to September 11. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42(3), 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing Research, 17(4), 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, I., & Amah, E. (2013). Knowledge management and organizational resilience in Nigerian manufacturing organizations. Developing Country Studies, 3(9), 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J., & Fang, Y. (2022). Strategic corporate social responsibility and organizational resilience: The chain mediation of network embeddedness and innovation capability. Science and Technology Management Research, 42(16), 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J., Wei, H., & Chen, Y. (2019). The mechanism of strategic corporate social responsibility promoting the formation and evolution of open innovation networks: A longitudinal case study of an internet financial company. Dongyue Tribune, 40(11), 120–131, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X., Yang, M., Liu, Y., Zhao, W., Shi, J., & Zhang, K. (2023). Design for product resilience: Concept, characteristics and generalisation. Journal of Engineering Design, 34(5–6), 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. L., & Dowell, G. (2011). Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, J. F., III, & Orr, J. E. (1997). Assessing behaviors that create resilient organizations. Employment Relations Today, 24(4), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M., & Papastathopoulos, A. (2022). Organizational readiness for digital financial innovation and financial resilience. International Journal of Production Economics, 243, 108326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B. W., & Allen, D. B. (2007). Strategic corporate social responsibility and value creation among large firms: Lessons from the Spanish experience. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D. (2007). The case for strategic corporate social responsibility in developing countries. Business and Society Review, 112(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J., & Li, J. (2022). An empirical study on the relationship between strategic corporate social responsibility and financial performance from an investment perspective. Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology (Social Science Edition), 24(3), 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. (2021). Building organizational resilience through strategic internal communication and organization–employee relationships. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 49(5), 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, G. P. (2001). The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 595–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., & Chen, G. (2022). Understanding financial resilience from a resource-based view: Evidence from US state governments. Public Management Review, 24(12), 1980–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., & Wang, W. (2023). Scene-driven, business model and the evolution of innovation ecosystems: Based on the value logic of Tesla. Science and Technology Progress and Policy, 40(17), 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P., & Zhu, J. (2021). Organizational resilience: A literature review. Foreign Economics & Management, 43(3), 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Xia, C., & Shi, J. (2023). Strategic research on high-quality development of manufacturing enterprises driven by digital technology: A multi-case study of SANY, Tesla, and Kute Smart. Technological Economy, 42(5), 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, K. M. (2017). Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Sheng, M. (2017). Strategic social responsibility and sustainable competitive advantage of enterprises. Economic and Management Review, 33(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Chen, R., & Zhou, F. (2023). Conceptual structure and formation mechanism of organizational resilience: A grounded theory study. Management Case Study and Review, 16(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., & Yin, J. (2020). Stakeholder relationships and organizational resilience. Management and Organization Review, 16(5), 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., & Xiang, P. (2021). Crisis process management: How to enhance organizational resilience? Foreign Economics & Management, 43(3), 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, S. D. (2011). Creating and capturing value: Strategic corporate social responsibility, resource-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais-Storz, M., Platou, S. R., & Norheim, B. K. (2018). Innovation and metamorphosis towards strategic resilience. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(7), 1181–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, A. R., Pfarrer, M. D., & Little, L. M. (2014). A theory of collective empathy in corporate philanthropy decisions. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N., & Bansal, P. (2016). The long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X., & Liu, Y. (2015). Strategic corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: Process mechanisms and contingency conditions. Management Review, 27(7), 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56–68, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G., Chowdhury, M., Spector, S., & Orchiston, C. (2018). Organizational resilience and financial performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 73(11), 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y., & Huang, Z. (2014). The relationship between strategic corporate social responsibility, open innovation, and firm performance: A case study of Jiangsu manufacturing industry. Economic System Reform, (6), 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, H., & Greve, H. R. (2018). Disasters and community resilience: Spanish flu and the formation of retail cooperatives in Norway. Academy of Management Journal, 61(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Richtnér, A., & Löfsten, H. (2014). Managing in turbulence: How the capacity for resilience influences creativity. R&D Management, 44(2), 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Sahebjamnia, N., Torabi, S. A., & Mansouri, S. A. (2018). Building organizational resilience in the face of multiple disruptions. International Journal of Production Economics, 197, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y., Xu, H., & Zhou, L. (2021). Digital intelligence empowerment: How does organizational resilience form in a crisis situation? An exploratory case study of Lin Qingxuan. Management World, 37(3), 84–104+7. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X., & Meng, X. (2015). The relationship between strategic social responsibility behavior and the source of sustainable competitive advantage: A study based on the resource-based theory. Economic Management, (6), 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C., Shi, Y., & Li, Y. (2023). Failure learning and firm performance: The role of organizational resilience and environmental dynamism. Management Review, 35(4), 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Tesla, Inc. (2021). Tesla 2021 impact report. Available online: https://www.tesla.cn/ns_videos/2021-tesla-impact-report_cn.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Tesla, Inc. (2022). Tesla 2022 impact report. Available online: https://www.tesla.com/ns_videos/2022-tesla-impact-report_cn.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Van Der Vegt, G. S., Essens, P., Wahlström, M., & George, G. (2015). Managing risk and resilience. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Hu, S., & Qian, X. (2011). Exploration of the frontier of strategic corporate social responsibility research and future prospects. Foreign Economics & Management, 33(11), 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. (2016). Concept, measurement, and influencing factors of organizational resilience. Journal of Capital University of Economics and Business, 18(4), 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T. A., Gruber, D. A., Sutcliffe, K. M., Shepherd, D. A., & Zhao, E. Y. (2017). Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 733–769. [Google Scholar]

- Wulijitu, H., & Wang, Y. (2021). Architectural innovation: Exploring the mechanism of Tesla’s competitive advantage. Studies in Science of Science, 39(11), 2101–2112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G., Zhang, C., & Liu, W. (2020). Turning crisis into opportunity: A review and outlook of organizational resilience research. Economic Management, 42(10), 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q., & Hua, Z. (2020). A review of resource orchestration theory and its research progress. Economic Management, 42(9), 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., & Teng, X. (2021). The connotation, dimensions, and measurement of organizational resilience. Science and Technology Progress and Policy, 38(10), 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R., & Li, L. (2023). Pressure, state and response: Configurational analysis of organizational resilience in tourism businesses following the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 370. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H., Li, D., & Zhang, W. (2019). Strategic corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: Mutual exclusivity or a win-win situation? Economic and Management Research, 40(6), 131–144. [Google Scholar]

| Researcher | Visual Angle | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Burke and Logsdon (1996) | CSR and strategic interests | CSR (policies, programs, or processes) that contribute to the core business activities and mission of the organization, and provide substantial business-related benefits to the organization |

| Baron (2001) | Motivation for behavior | A socially responsible profit maximization strategy for the company |

| Lantos (2001) | Nature of responsibility, motivation for behavior | Strategic philanthropy aimed at achieving strategic business objectives |

| Porter and Kramer (2002) | Corporate strategy, social value | Strategic corporate engagement in philanthropy to enhance competition, achieve financial goals, and create social value |

| Bagnoli and Watts (2003) | Private interests, public interests | Businesses increase the amount of private goods they offer when they also provide public goods to society, as seen in Bertrand and Gounod competitions |

| Porter and Kramer (2006) | Enterprise-society interrelationships, strategic objectives | SCSR creates shared value by addressing social issues, reshaping the relationship business and society, and promoting economic and social development |

| Jamali (2007) | Nature of responsibility, motivation for responsibility | SCSR is an effective combination of philanthropic contributions, business objectives, and strategies that align social and economic benefits |

| Husted and Allen (2007) | Traditional CSR, traditional corporate strategy, and SCSR | With the goal of value creation, SCSR reorganizes corporate resources and capabilities through product and service innovation to create greater value |

| Bhattacharyya (2010) | Strategic features | SCSR is a CSR with strategic characteristics such as centripetal, long-term orientation, and resource commitment |

| McWilliams and Siegel (2011) | Strategic objectives | “Responsible” activities can achieve sustainable competitive advantage without considering behavioral motivations |

| Bruyaka et al. (2013) | Motivation for behavior | CSR activities can bring economic and non-economic benefits to the company and its stakeholders, and they are closely integrated with the company’s core business activities |

| Features | Connotation |

|---|---|

| Centrality | SCSR is a core component of a company’s development strategy and is closely related to its core business objectives and mission |

| Specificity | SCSR establishes clear goals and strategies, provides services to society in a non-economic way, and addresses social problems by creating shared value |

| Proactivity | SCSR is a long-term approach for sustainable development, requiring enterprises to maintain vision and foresight, proactively monitor social and environmental changes, and develop CSR strategies in line with future trends |

| Voluntarism | SCSR represents a social responsibility voluntarily undertaken by enterprises. |

| Visibility | Enterprises need to demonstrate their CSR commitment and actions transparently, presenting their activities and achievements to their stakeholders |

| Label | Conceptualization | Categorization |

|---|---|---|

| a1 Produce excellent products | A1 Business positioning | AA1 Organizational core elements |

| a2 Synergistic Benefits | A2 Product positioning | |

| a3 Inspire global progress through products | A3 Mission and vision | |

| a4 Transform into a vertically integrated energy company | A4 Business transformation | AA2 Organizes business development |

| a5 Combine solar energy a6 Enter energy distribution and transmission market | A5 Business development | |

| a7 Sustainability Council | A6 Management involvement | AA3 Corporate governance |

| a8 Oversee significant risks | A7 Board supervision | |

| a9 Address human rights issues | A8 Respect for human rights | |

| a10 Open up proprietary technology | A9 Open up intangible resources | AA4 Industry-leading |

| a11 Open up superchargers | A10 Open up physical infrastructure | |

| a12 Continuous iterative product upgrades | A11 Operational strategy | AA5 Strategic planning |

| a13 Offer diverse installment options a14 Lower the barrier to purchase | A12 Marketing strategy | |

| a15 Lower pricing | A13 Price strategy | |

| a16 Business expansion | A14 Market entry strategy | |

| a17 Partnerships | A15 Strategic cooperation | |

| a18 Integration of internal and external resources | A16 Resource integration | |

| a19 Supplier diversification | A17 Supply chain management | AA6 Sustainable Supply Chain Management |

| a20 Sourcing from mining and refining companies | A18 Responsible sourcing | |

| a21 Recycle batteries a22 Establish internal ecosystems | A19 Recycling | |

| a23 Replace traditional labor with advanced robotics | A20 Production mode change | AA7 Organizational change |

| a24 Transition to software services | A21 Business model change | |

| a25 Flatten organizational structure a26 Reduce organizational hierarchy | A22 Organizational change | |

| a27 Reward employees for identifying issues | A23 Employee motivation | AA8 Humanistic care |

| a28 Respect employees a29 Encourage feedback | A24 Employee care | |

| a30 Low workplace injury rates | A25 Employee safety | |

| a31 Benefits programs | A26 Generous employee benefits | |

| a32 Fair compensation structure | A27 Reasonable compensation philosophy | |

| a33 Attract talent | A28 Broaden employment opportunities | AA9 Talent expansion |

| a34 Increase independent directors | A29 Complementary management team | |

| a35 Internet self-media marketing a36 Direct marketing model a37 Customized model | A30 Customer experience | AA10 Customer management |

| a38 Personalization needs | A31 Respond to customer needs | |

| a39 Team of privacy and security experts a40 Privacy Principles | A32 Manage data privacy | |

| a41 Establish joint ventures | A33 Equity financing | AA11 Financing capacity |

| a42 Project Financing | A34 Project financing | |

| a43 Convertible note issuance | A35 Bond financing | |

| a44 Convertible bond hedges a45 Warrant transactions | A36 Risk management | AA12 Performance management |

| a46 Net income distribution | A37 Revenue management | |

| a47 Increase in security | A38 Target management | |

| a48 Loans prepayment | A39 Solvency | AA13 Financial situation |

| a49 Maintain liquidity | A40 Liquidity situation | |

| a50 Product recalls | A41 I Accident management | AA14 Intelligent after-sales service |

| a51 Intelligent customer service system | A42 Smart aftermarket | |

| a52 Vehicle safety standards a53 Collaboration with safety groups | A43 Product safety | AA15 Product RandD innovation |

| a54 Locate and develop key technologies a55 Self-research ecosystem establishment | A44 Core technology RandD | |

| a56 New design for new product | A45 Continuous product improvement | |

| a57 Multi-module innovation a58 Innovation ecosystem | A46 Independent innovation upgrade | |

| a59 Expand software and content services | A47 Software ecosystem services | |

| a60 Long-term cost savings | A48 Cost management | AA16 Efficient cost control |

| a61 Complete vehicle production a62 Expansion of business scope a63 Establishment of super plants a64 Development of autonomous driving a65 Corporate governance structure | A49 Implementation of long-term development decisions | AA17 Company philosophy Shaping |

| a66 People-centered approach a67 Data-driven | A50 Principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion | |

| a68 Business ethics | A51 Code of business ethics | |

| a69 Foster transparent communication a70 Encourage feedback mechanisms a71 Open communication channels | A52 Communication with employees | AA18 Good working atmosphere |

| a72 Security goals | A53 Safety culture | |

| a73 Apprenticeship programs a74 Multi-role training orientation | A54 Holistic talent training | AA19 Learning and Optimization |

| a75 Constant reflection and proactive improvement through real-world situations | A55 Proactive learning | |

| a76 Pattern observation and data analysis | A56 Learn from observation | |

| a77 Adopt best practices from top companies | A57 Learn from excellent companies | |

| a78 Vaccination | A58 Participate in safe communities | AA20 Community involvement |

| a79 Employee resource groups | A59 Enhance community interaction | |

| a80 Provide aid for earthquake victims | A60 Charitable giving | AA21 Social assistance |

| a81 Invest in K-12 education | A61 Invest in education | |

| a82 Disaster relief systems | A62 Disaster assistance | |

| a83 Use of renewable energy | A63 Sustainable energy | AA22 Environmental impact |

| a84 Enhance energy efficiency | A64 Reduce carbon footprint | |

| a85 Reduce water consumption a86 Collect and reuse a87 Promote water reuse a88 Use of reclaimed water | A65 Water resources management | |

| a89 Create more and diversify jobs | A66 Job creation | AA23 Social impact |

| a90 Economic impact of battery production plants | A67 External economic impacts |

| Main Category | Category | Connotation |

|---|---|---|

| Development governance resilience | Organizational core elements | Provides direction and motivation for organizational development, playing a crucial role in defining the organization’s goals and growth path |

| Organizational business development | The foundation for sustainable organizational growth, closely tied to profitability, resource allocation, and market position | |

| Organizational governance | Institutional structures and management practices that guide organizational behavior, protect shareholder interests, enhance enterprise value, and support sustainable growth | |

| Strategic management resilience | Industry-leading | Maintaining a leadership position within the industry, setting development trends, and expanding market opportunities |

| Strategic planning | A blueprint that shapes long-term competitiveness and directs future growth | |

| Supply chain management | Coordination and oversight of suppliers and production processes, crucial for ensuring smooth production and operational continuity | |

| Organizational change | A means for adapting environmental changes and strengthening organizational competitiveness | |

| Relationship resilience | Humanistic care | Emphasizes human-centered values, helping to build a positive corporate image and boost employee loyalty and engagement |

| Talent expansion | Continual recruitment and talent development to align with market shifts and business needs | |

| Customer management | Customer-focused approach to market growth, delivering prompt and thoughtful quality service to attract new customers, retain current ones, and build loyalty | |

| Financial resilience | Financing capacity | Ability to secure capital from various sources, including banks, equity, and debt markets |

| Performance management | Enhancing organizational and employee performance by setting and evaluating performance targets and KPI (Key Performance Indicators) | |

| Financial situation | Overview of the sources and distribution of the organization’s operating funds | |

| Product resilience | Intelligent after-sales service | AI-driven after-sales model that enhances customer service experience and operational efficiency |

| Product RandD innovation | Ongoing product improvement and development by incorporating new technologies, ideas, or methodologies to meet market demands | |

| Efficient cost control | Optimizing resource use and implementing effective cost planning, control, and management strategies | |

| Cultural resilience | Company philosophy Shaping | The group spirit and organizational values developed through operation and growth |

| Good working atmosphere | A positive work environment that is recognized and valued by organizational members | |

| Learning and Optimization | Continuous adaptation and redesign efforts that enable the organization to thrive in a dynamic environment | |

| Social resilience | Community involvement | Encouraging voluntary participation in community affairs and embracing shared community responsibilities |

| Social assistance | Facilitating voluntary social support activities | |

| Environmental impact | Effects of an organization’s environmental responsibility | |

| Social impact | Consequences of the organization’s social responsibility initiatives |

| Organizational Resilience | Stakeholders | SCSR |

|---|---|---|

| Development governance resilience Strategic management resilience | Shareholders, suppliers, consumers, employees | Centrality, specificity, proactivity |

| Relationship resilience | Consumers and employees | Proactivity, voluntarism |

| Financial resilience | Shareholders | Proactivity, visibility |

| Product resilience | Consumers | Specificity, visibility |

| Cultural resilience | Employees | Voluntarism, visibility |

| Social resilience | Community and environment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Zhou, Y. The Impact of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Resilience—An Exploratory Case Study Based on Tesla. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060212

Liu X, Zhou Y. The Impact of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Resilience—An Exploratory Case Study Based on Tesla. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):212. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060212

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoping, and Yishu Zhou. 2025. "The Impact of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Resilience—An Exploratory Case Study Based on Tesla" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060212

APA StyleLiu, X., & Zhou, Y. (2025). The Impact of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Resilience—An Exploratory Case Study Based on Tesla. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060212