Abstract

This study explores gender perceptions and equity challenges within the maritime cruise industry, focusing specifically on crew experiences aboard European Union-flagged vessels. The research aims to evaluate the extent to which gender diversity, equality, and inclusion are perceived, practiced, and institutionalized onboard. A structured Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey was administered to the crew members across various departments and ranks, investigating perceptions of discrimination, career advancement, workplace safety, and the implementation of gender-sensitive policies. Results indicate persistent gender disparities, particularly in areas such as promotion opportunities, emotional burden, and reporting of harassment. While overall attitudes toward diversity appeared positive, a significant proportion of female respondents reported experiencing bias, isolation, and unequal treatment despite possessing equivalent qualifications. Statistical analysis, including Chi-square tests and Exploratory Factor Analysis, identified three dominant perception dimensions: structural bias, emotional strain, and safety concerns. A notable gap emerged between institutional policies and actual behaviours or trust in enforcement mechanisms. The authors contribute to the field by designing a context-specific KAP instrument, applying robust statistical methodologies, and offering actionable recommendations to maritime organizations. These include enhancing reporting systems, improving mentorship opportunities, and institutionalizing training on unconscious bias. This study provides empirical evidence to support policy reforms and cultural shifts aimed at fostering gender-inclusive environments onboard maritime cruise vessels.

1. Introduction

The maritime industry plays a vital role in the global economy, facilitating over 80% of global trade (IMO, 2023). Yet, the sector remains deeply gendered, with women comprising only 2% of the global seafaring workforce and typically confined to hospitality roles on cruise ships (Belcher et al., 2003; IMO, 2023). Historical gender norms, occupational segregation, and systemic discrimination continue to constrain women’s participation and advancement at sea. While significant policy progress has been made by organizations such as the IMO and ILO, research increasingly highlights a gap between formal equity policies and actual onboard experiences. Addressing this gap requires not only descriptive accounts but also analytical insights grounded in organizational and gender theory. This study contributes to this objective by applying a structured Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) framework to assess gender dynamics on EU-flagged cruise ships, with particular attention to the persistence of structural bias, emotional burden, and safety perceptions in daily practice. Organizations such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) have implemented policies to improve gender equality in maritime professions, synthetized as follows: the IMO promotes women in maritime programmes by providing scholarships, mentorship, and networking opportunities for female seafarers, while the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) introduced gender-inclusive guidelines to protect women’s rights at sea. Efforts to promote gender equality in maritime professions have gained traction in recent years, driven by international bodies and regional frameworks. The IMO’s Women in Maritime Programme promotes inclusion through capacity building, policy development, and visibility initiatives (IMO, 2023). Concurrently, the European Union’s Union of Equality: Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 (European Commission, 2020) sets ambitious goals for eliminating workplace discrimination and promoting gender balance in leadership, including within male-dominated sectors like maritime transport. Beside these international organizations’ initiatives, regional gender inclusion initiatives have prevailed, for example, the EU implemented gender quotas in maritime leadership roles; the Philippines, one of the largest suppliers of maritime labour, has introduced government-funded scholarships for female cadets; and Norway and Sweden have progressive maternity policies allowing women to balance work and family life in the maritime sector.

Women’s underrepresentation is the result of deeply embedded structural and cultural barriers, including gender-based discrimination, limited access to training, inadequate promotion opportunities, and pervasive occupational segregation (Kitada, 2021; Pike et al., 2017). Nonetheless, female seafarers continue to encounter challenges ranging from unequal pay and stereotyping to sexual harassment and isolation, especially in hierarchical and male-centric environments such as ships (ILO, 2019; Ewedji et al., 2024). Studies have demonstrated that female maritime professionals are less likely to occupy operational or command positions and are often excluded from decision-making processes (Turner & Wessel, 2024; Susaeta et al., 2024). These systemic inequities not only undermine the principle of equal opportunity but also hinder the operational efficiency and social sustainability of maritime enterprises.

In this context, the Healthy Sailing project ”Prevention, mitigation, management of infectious diseases on cruise ships and passenger ferries” (HORIZON-CL5-2021-D6-01-12) initiated and implemented under the HORIZON-CL5-2021-D6-01-12 programme seeks to develop into a comprehensive approach the innovative, multi-layered, risk- and evidence-based, cost-effective tested measures for infectious diseases prevention, mitigation, and management (PMM) differentiated for large ferries, cruise ships, and expedition vessels (https://healthysailing.eu, accessed on 1 March 2025) while simultaneously integrating gender inclusivity as a key performance dimension. The project recognizes that promoting gender equity onboard is not merely a social imperative but also essential for enhancing team cohesion, safety culture, and crisis management capabilities during health emergencies.

In this line, the present paper aims to contribute to this multidimensional objective by analyzing gender-related perceptions and experiences among seafarers through the application of a structured Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey. By capturing the lived realities and policy awareness of crew members across diverse departments, this study aims to inform the development of a gender-sensitive quality management strategy within the Healthy Sailing consortium. The findings are intended to guide the implementation of inclusive training programmes, inform policy design, and contribute to broader gender equality objectives in line with international maritime and human rights standards.

2. Literature Review:Research Gap

This research along with the literature review explores the state of gender equality in the maritime industry, focusing on challenges faced by women, policies promoting inclusivity, and the changing dynamics of the workforce. The maritime industry has traditionally been male-dominated, with limited representation of women onboard ships. Gender-related challenges in this sector include discrimination, harassment, health and safety concerns, and difficulties in career progression. To reflect the current trends, the pursued literature review explores the key issues faced by women in maritime shipping and the measures proposed to enhance gender inclusivity. Therefore, in line with the diversity and inclusion imperatives, the authors approached in the first stage of conducting research the topic of gender in maritime shipping, with a special focus on the cruise industry, aiming to identify the research gaps and consequently to provide the right basis for development of a survey to be applied in cruise companies by the Healthy Sailing partners.

2.1. Gender Issues in Maritime Shipping

The literature review is centred on key topics regarding gender issues in maritime shipping, with special attention awarded to the cruise line industry. While numerous studies document discrete challenges faced by female seafarers—harassment, pay inequality, and occupational segregation—fewer works have synthesized these strands through the lens of organizational and gender theory. This study adopts feminist organizational perspectives, stereotype threat theory, and concepts of institutional decoupling to interpret how formal gender equity policies interact with entrenched shipboard hierarchies. We draw on these frameworks to analyze survey findings not merely as isolated perceptions but as indicators of systemic organizational dynamics.

Therefore, considering this approach, the authors have defined the major gender topics treated in the international literature as follows:

a. Gender discrimination and bias—Women seafarers often face discrimination in hiring, promotions, and workplace treatment due to gender bias and stereotypes. In this area, Deschenes (2024) explores the historical roots of gender bias in the maritime industry, emphasizing how sailors’ traditional beliefs have perpetuated discrimination against women onboard ships and highlighting the cultural resistance towards female seafarers and how such biases affect gender equality efforts. Papanicolopulu (2024) examines the role of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in promoting gender equality, arguing that while policy advancements have been made, practical implementation is slow.

Moreover, women seafarers often experience discrimination, mostly related to limited job opportunities, with women being more frequently assigned to specific roles rather than operational or leadership positions. Also, there are limited career advancement opportunities for women due to systemic biases and traditional gender norms. In a recent case study regarding the lack of female leadership in the maritime sector, a group of researchers studying gender representation in maritime leadership found that women remain vastly underrepresented in leadership positions, with only 5% of maritime executives being female, and few women usually achieve leadership positions, with those who do often being assigned to executive roles related to HR or administration rather than core operational roles (Dai et al., 2024).

b. Harassment and safety concerns—Sexual harassment and violence onboard ships remain serious concerns for women seafarers. Related to this concern, some authors have analyzed sexual abuse cases involving female crew members, discussing how a lack of strict enforcement of harassment policies leaves women vulnerable, highlighting the psychological impact of workplace harassment on women at sea (Jha & Singh, 2024). Some others investigated gender dynamics and workplace harassment, noting that women in the maritime sector often avoid reporting incidents due to fear of retaliation or career damage (Karunatilleke et al., 2024). Moreover, in a recent case study regarding harassment and gender bias in the ship industry that analyzed stress levels among female and male seafarers, it was found that women experience higher workplace stress due to gender discrimination, with many female seafarers struggling with a lack of sanitary facilities, separate accommodations, and maternity leave policies (Suresh & Krithika, 2024).

c. Health and well-being challenges—Women onboard ships face unique health concerns, including inadequate medical facilities and gender-specific healthcare issues. On this perspective, several authors have approached the health challenges faced by female sailors, particularly the limited availability of medical care tailored to women’s physiological needs, suggesting in their studies policy reforms to ensure better healthcare facilities onboard (Timchenko, 2025). Others emphasized the importance of improving health maintenance practices for female seafarers, highlighting issues such as stress, isolation, and access to reproductive healthcare (Botnaryuk, 2025).

d. Career advancement and work–life balance—Women seafarers face systemic barriers to career progression and work–life balance. As reflected in the studies referenced, recent studies examined how gender roles in maritime careers affect women’s professional growth, pointing out the lack of mentorship and support systems for female officers (Tang, 2023; Grimett, 2024). Along the same lines, other authors explored stress levels and mental health concerns among female seafarers, emphasizing the need for mental health support services to retain more women in the industry (Suresh & Krithika, 2024). Moreover, a recent study conducted by García-Echalar et al. (2024) analyzed gender equity in Chile’s maritime sector, finding that women occupy only 7% of port management roles. Female seafarers are underrepresented in operational positions, often relegated to administrative and hospitality roles, while employers are still perceiving women as physically unfit for shipboard jobs, reinforcing gender segregation (García-Echalar et al., 2024).

e. Workplace discrimination and harassment—Women seafarers reported high levels of discrimination and harassment onboard. A study conducted by Ewedji et al. (2024) on Ghana’s maritime sector found that sexual harassment is a prevalent issue, with 43% of female seafarers experiencing some form of verbal or physical abuse at sea. Also, they proved that women often feel socially isolated onboard (i.e., as ships typically having only one or two female crew members per vessel), onboard workplace bullying is present, and a lack of female mentors further discourages women from pursuing long-term careers in maritime professions.

Moreover, considering workplace discrimination, there were reflected relevant gender pay gaps in maritime professions. The differences in remuneration remain a significant concern in seafaring professions, with men typically earning higher wages than women for similar work. A result from the conducted research revealed that this situation is mostly due to unequal access of female seafarers to leadership assignments, gender biases in promotion criteria, and fewer opportunities for professional development of women seafarers (Kitada & Langåker, 2017). Women in the maritime sector face significant wage disparities, earning 10–30% less than their male counterparts in similar roles. Therefore, in a case study conducted regarding the gender wage gap in Norway’s Maritime Industry, the authors found that the wage gap in the maritime industry is higher than in other sectors, with female maritime workers earning 25% less than men on average. Additionally, women are less likely to receive salary increases or promotions, despite having similar qualifications and experience, and a certain lack of female representation in decision-making roles contributes to inequitable pay structures (Turner & Wessel, 2024).

2.2. Gender Equity in the Maritime Cruise Industry

The cruise industry is one of the most diverse sectors in maritime employment, with a significant representation of women compared to other maritime domains. However, despite this representation, similarly to all maritime employment, gender disparities persist in leadership, pay, and working conditions, as shown from the literature review examining the state of gender equality in the cruise industry supported by academic research and case studies. The authors have found few relevant studies in this area apart from those already depicted in the previous sub-section. The major gender inequities are outlined in the following.

a. Gender-based discrimination and labour division—The cruise industry has a clear gendered division of labour, where men often occupy technical and managerial roles, while women are relegated to hospitality and caregiving positions. A recent study examining historical and contemporary gender roles on cruise ships observed that women are frequently assigned lower-paying roles in guest services, while men dominate technical and navigation positions, and this segregation limits women’s career advancement opportunities in the industry (Tyrrell, 2024). Additionally, other authors have explored the experiences of workers in the cruise industry, highlighting the challenges of gender identity and expression for those in traditionally male-dominated roles, disclosing systemic inequalities and workplace conditions that hinder gender equality (Vorobjovas-Pinta, 2024).

b. Workplace harassment and safety concerns—Sexual harassment and gender-based violence remain significant concerns for women working onboard cruise ships due to the isolated and hierarchical nature of the industry. In the professional domain, few authors have studied how the historical culture of masculinity within the cruise industry has contributed to the persistence of gender-based harassment (Dudley & Cobb, 2024).

c. The gender diversity experience on cruise ships—Beyond traditional gender issues, employees from different sexual minority groups acting onboard cruise ships face additional challenges related to workplace inclusion, discrimination, and identity expression. Past scientific studies highlighted the unique experiences of LGBTQ+ workers in the cruise industry, emphasizing that while progress has been made, many still face discrimination, a lack of support systems, and difficulties in career advancement due to gender and sexual identity biases (Vorobjovas-Pinta, 2024). In this regard, it is also noted that LGBTQ+ representation varies significantly depending on cruise lines and regions, with some companies fostering inclusive policies while others lag in providing protections for non-binary and gender-diverse employees.

d. Gender representation in the cruise industry—Compared to other maritime sectors, the cruise industry employs a higher proportion of women, which makes the conducted analysis more relevant. Women make up around 20–25% of the global cruise workforce, while in other shipping industries, female representation is typically below 2% (Susaeta et al., 2024).

e. Occupational segregation and inequal treatment—Despite higher female employment rates, occupational segregation remains a key challenge in the cruise industry. Although, women are primarily employed in hospitality, customer service, and housekeeping roles, technical and navigation roles, such as deck officers, engineers, and captains, remain dominated by men; thus, women facing limited career progression in operational roles in the cruise industry (Yoon & Cha, 2017). As reflected in a recent case study regarding the women’s career progression in the cruise industry, only 5% of cruise ship captains and senior officers are women, and women often struggling to transition from hospitality to operational roles, even when they meet the qualifications (Susaeta et al., 2024).

f. Gender pay gap in the cruise industry—Despite diversity efforts, the cruise industry still exhibits gender-based pay discrepancies, similarly to other sea transportation services. As proven in previous studies, women working in onboard entertainment, hospitality, and services earn 15–25% less than their male colleagues in equivalent positions, and men dominate high-paying roles in ship operations, logistics, and engineering, contributing to the wage gap (Susaeta et al., 2024). The gender wage gap in the cruise industry is influenced by limited access to high-ranking positions (as women rarely hold roles in ship command), bonuses and performance incentives (as male employees in technical and operational roles receive higher performance-based bonuses), and by contract structures (as many female cruise workers are hired on short-term contracts, limiting access to salary increases and promotions). A recent study comparing European and American cruise lines found that European cruise companies have lower gender pay gaps due to stricter labour laws and gender equality policies, and female cruise officers earn 12–18% less than male officers, even with similar experience and rank (CLIA, 2023).

g. Gender discrimination and harassment onboard—The cruise industry has reported high rates of workplace discrimination and sexual harassment against female employees (Vasiliadis et al., 2024). Despite efforts to promote inclusivity, gender discrimination and harassment remain pervasive in the cruise industry. The hierarchical and enclosed nature of cruise ship environments, combined with cultural diversity and traditional gender norms, can create conditions conducive to bias, stereotyping, and abuse—particularly affecting women and gender-diverse employees (Belcher et al., 2003; Kitada, 2021). Research has shown that female crew members often face barriers to fair treatment, professional respect, and career advancement. Discrimination manifests in various forms, including unequal task assignment, limited promotion opportunities, and exclusion from decision-making processes. Harassment—ranging from verbal abuse to physical misconduct—is also widely reported, particularly among crew members working in lower-deck positions such as housekeeping, food services, and entertainment (Susaeta et al., 2024).

One of the key structural issues in addressing harassment onboard is the lack of effective and confidential reporting mechanisms. Fear of retaliation, contract termination, or social exclusion often deters victims from speaking out (Pike et al., 2017). Moreover, the temporary and multinational nature of cruise employment complicates accountability, as many cruise lines operate under “flags of convenience,” which limit enforcement of labour protections and weaken regulatory oversight. Studies have highlighted that while major cruise companies have adopted zero-tolerance harassment policies, implementation is often inconsistent. Training programmes may exist, but they are not always enforced systematically across departments or cruise fleets. Furthermore, cases of gender-based harassment are frequently dismissed or inadequately investigated, undermining crew trust in existing systems (Dudley & Cobb, 2024).

2.3. Policies and Initiatives for Gender Equality in the Cruise Industry

The cruise industry, as part of the wider maritime sector, has increasingly come under scrutiny for its gender disparities in employment, leadership representation, and workplace safety. In response, a range of international and regional institutions, including the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the International Labour Organization (ILO), and the European Union (EU), have launched initiatives and policies aimed at promoting gender equality. These frameworks are particularly important for shaping regulatory expectations and guiding corporate action among cruise operators.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has taken significant steps to address gender imbalances through its Women in Maritime Programme, established in 1988. This initiative supports the development of female maritime professionals by offering technical training, fellowships, and access to leadership networks (IMO, 2023). The IMO also promotes the integration of gender perspectives in maritime governance through capacity-building activities and regional associations such as WIMAC (Women in Maritime Associations). The organization emphasizes that increasing female participation is essential to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender Equality and improving the overall effectiveness of maritime operations (IMO, 2023).

The International Labour Organization (ILO) plays a central role in safeguarding workers’ rights at sea, including gender-related protections. The Maritime Labour Convention (MLC, 2006), sometimes referred to as the “seafarers’ bill of rights,” establishes legally binding standards on non-discrimination, safe working conditions, and fair treatment for all seafarers regardless of gender (ILO, 2006). In 2019, the adoption of ILO Convention No. 190 on Violence and Harassment marked a major advancement by explicitly recognizing the right of everyone to a workplace free from violence, including gender-based harassment, a pressing issue in enclosed environments like cruise ships (ILO, 2019; ILO, 2022).

These instruments obligate cruise companies and flag states to implement protective mechanisms and reporting channels that prevent gender-based abuse and promote psychological safety onboard.

At the regional level, the European Union’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 provides a comprehensive framework for reducing gender gaps across sectors, including transport and maritime employment. The strategy emphasizes equal pay, work–life balance, and increased representation of women in decision-making roles (European Commission, 2020). Additionally, Directive (EU) 2019/1158 on work–life balance for parents and carers, and Directive 2006/54/EC on equal treatment in employment and occupation, establish enforceable legal standards for addressing workplace discrimination, maternity protections, and equal promotion pathways (European Commission, 2019, 2020).

In reference to cruise line-level implementation, in response to these regulatory pressures, several cruise operators have introduced internal ”Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) strategies. For example, Royal Caribbean has committed to a 50% gender target for new hires in hospitality leadership, Norwegian Cruise Line has implemented gender-neutral pay structures, and Carnival Corporation runs mentorship programmes tailored to women in operational roles (CLIA, 2023). However, despite these initiatives, enforcement and transparency vary significantly between companies. Surveys continue to report underrepresentation of women in command roles, persistent pay gaps, and fear of reporting harassment due to retaliation or lack of confidential mechanisms (Susaeta et al., 2024; Dudley & Cobb, 2024). Moreover, in 2019, Captain Kate McCue became the first American female captain of a major cruise ship, and since then, the number of female captains has slightly increased, but they still represent less than 3% of all captains (Susaeta et al., 2024).

The convergence of IMO, ILO, EU, and company-level gender policies establishes a strong normative framework for achieving gender equality in the cruise industry. However, the translation of these policies into operational realities remains inconsistent. Strengthening monitoring systems, supporting independent audits, and institutionalizing gender training are essential next steps to ensure that equality is not only legislated but actively practiced at sea.

In conclusion, based on the reviewed literature, several measures can be implemented to improve gender inclusivity onboard cruise ships:

- Policy enforcement—Strengthening and enforcing anti-harassment policies through independent monitoring bodies;

- Career advancement opportunities—Creating pathways for women and LGBTQ+ employees to enter managerial and technical roles;

- Mental health support—Implementing dedicated support services for gender and diversity issues onboard.

- Diversity training—Regular gender sensitivity and inclusivity training programmes for all employees.

- Safe reporting mechanisms—Establishing confidential channels for reporting harassment or discrimination.

To address the research gap, the authors have identified a specific need for a targeted study on the cruise lines industry, for European Union flagged ships, to reflect the specificities of communitarian professionals in regard to gender policies and the diversity strategies implementation at all corporate levels.

Despite the growing body of scholarship addressing gender inequality in the maritime sector, a key research gap persists at the intersection of policy perception, lived experience, and organizational practice, particularly within the cruise industry, which has received comparatively limited attention in empirical gender studies. Much of the existing literature either adopts a normative policy lens focused on institutional frameworks (e.g., IMO, ILO, EU directives), or it investigates discrete issues such as sexual harassment, pay disparity, or occupational segregation in isolation. Few studies, however, examine how these structural and cultural challenges are perceived, internalized, and navigated by crew members themselves—especially in operational contexts where formal policies may be inconsistently enforced or socially diluted. Even fewer investigations focus on the European cruise sector, where gender equality mandates coexist with deeply entrenched maritime hierarchies and multinational labour dynamics.

In response, this study adopts a deliberately integrative review strategy, aiming not only to document the thematic landscape but to expose the complex interplay between institutional narratives and onboard realities. By synthesizing findings across categories, discrimination, career advancement, safety, and emotional well-being, the present study aims to develop a diagnostic view of gendered labour dynamics that foregrounds the inconsistencies and contradictions within the industry’s equity discourse. This analytical lens informed our selection of a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) methodology, which offers a unique capacity to reveal how gender norms are both cognitively understood and behaviourally enacted by crew members. In doing so, the study bridges the gap between macro-level policy commitments and micro-level social dynamics, allowing for a more nuanced assessment of the conditions under which gender inclusion is, or is not, achieved. This research thus advances both conceptual and empirical understanding of gender in maritime professions, with a focused contribution to the underexplored domain of EU-flagged cruise operations.

3. Methodology

The Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey is a widely utilized empirical research tool that systematically assesses what respondents know (knowledge), believe (attitudes), and do (practices) regarding a specific topic. In public health, education, and increasingly in social sciences and gender studies, KAP surveys offer insight into both behavioural and perceptual dimensions of human interaction (Launiala, 2009; World Health Organization [WHO], 2008). Originally developed in the 1950s within public health research, KAP surveys were used to understand behavioural barriers to disease prevention and treatment (Hausmann-Muela et al., 2003). Over time, the model has been adopted by other disciplines, including organizational psychology, development studies, and gender research, due to its ability to combine descriptive and inferential data (Launiala, 2009).

The main objective of KAP surveys is to identify gaps between what people know and what they actually practice, these gaps being crucial in designing interventions, policy adjustments, or training programmes. In the present case of gender research, the KAP model may be particularly relevant for assessing how institutional policies—such as anti-discrimination regulations or gender equity strategies—are perceived and internalized by individuals within an organization (Kitada, 2021; Pike et al., 2017). Moreover, in maritime contexts, where hierarchical structures, gender norms, and operational pressures intersect, the KAP model may offer a feasible structured and replicable methodology for analyzing workplace culture, inclusivity, and policy implementation.

The KAP model was selected for its capacity to bridge perceptual and behavioural dimensions of gender experience, a critical feature in contexts where formal DEI policies may not align with daily shipboard culture (Pike et al., 2017). Compared to models such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour, KAP offers greater flexibility in capturing cross-cultural onboard dynamics and the lived realities of a multinational maritime workforce.

For workplace-based gender research in the maritime domain, KAP surveys enable an analysis of both explicit and implicit biases. Consequently, the “knowledge” component assesses awareness of legal frameworks and institutional policies (e.g., equal opportunity laws, anti-harassment protocols) in the maritime sector; the “attitude” component reflects individual and collective beliefs regarding onboard gender roles, equality, and inclusion; and the “practice” component evaluates actual behaviours, such as reporting discrimination, supporting inclusive teamwork, or adhering to gender-sensitive conduct onboard maritime ships (ILO, 2019; ILO, 2022; IMO, 2023; Papanicolopulu, 2024). This structure is effective in identifying “attitude-practice gaps,” where individuals may express support for gender equality but fail to act accordingly in real-world settings. Such discrepancies are particularly relevant in maritime environments, where crew dynamics, physical constraints, and chain-of-command principles influence behaviour (Susaeta et al., 2024).

For the present research, the KAP methodology offers several advantages in scientific research, motived by the authors as follows:

- –

- Multidimensionality—This captures cognitive (knowledge), affective (attitudes), and behavioural (practices) dimensions in a single instrument with correlative meaning to the gender and diversity issues onboard maritime ships (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008);

- –

- Adaptability—KAP instruments can be tailored to specific cultural, professional, or institutional contexts in seafaring professions, making them highly flexible, including for the cruise lines domain (Launiala, 2009; Papanicolopulu, 2024);

- –

- Comparative potential—The results can be disaggregated by demographic variables, such as gender, rank, or onboard department, allowing for targeted analysis and policy refinement for maritime crew (Hausmann-Muela et al., 2003).

Within the present research, the KAP survey was developed and applied by the authors as part of the healthy sailing project (HORIZON-CL5-2021-D6-01-12, https://healthysailing.eu, accessed on 1 March 2025), to assess gender inclusivity and diversity awareness among cruise ship personnel and consortium members. The survey is mainly structured to capture:

- –

- The awareness of the EU’s Union of Equality Strategy (European Commission, 2020);

- –

- The perceptions of gender fairness, task assignment, and leadership equality onboard;

- –

- Self-reported behaviours regarding discrimination, harassment reporting, and workplace collaboration;

- –

- The onboard policies compliance with international requirements such as the Maritime Labour Convention (ILO, 2006) and ILO Convention No. 190 (ILO, 2019).

While KAP surveys are methodologically robust, they are not without limitations. Responses may be influenced by social desirability bias, especially on sensitive issues like gender bias or harassment (Bryman, 2016). Moreover, the self-reported nature of “practice” items may not always reflect actual behaviour. To mitigate these risks, the KAP surveys were administered anonymously, with careful attention to question phrasing and cultural context; these ethical protocols were embedded in the survey rollout to ensure confidentiality, voluntary participation, and informed consent.

The KAP survey was administered to over 500 crew members onboard cruise ships/professionals on EU cruise lines, within the broader scope of the Healthy Sailing project’s work package on infectious disease management and quality assurance. Data collection for the present study took place between May and December 2024, and the objective was not only to evaluate individual and collective knowledge regarding gender equality frameworks but also to uncover underlying attitudes and real-world practices influencing the gender climate onboard. This approach aligns with international recommendations from the International Labour Organization (ILO, 2019) and the European Commission (2020), which advocate for data-driven gender audits in occupational sectors marked by persistent inequalities, such as maritime transport (Kitada, 2021; Susaeta et al., 2024).

Regarding the research objectives, by developing the present research, the authors aimed:

- –

- To assess the gender and diversity policy awareness among the crew members, focused mainly on the cruise industry and maritime transport;

- –

- To identify the existence and implementation of gender policies onboard ships;

- –

- To disclose awareness of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment (SASH) policies and procedures onboard the ships;

- –

- to define the compliance with “Union of Equality: EU gender equality strategy”/2020–2T25 COM (2020)/152/5.3.20;

- –

- To reveal the crew members’ perceptions regarding onboard female professionals;

- –

- To assess the role of female leaders onboard the ships;

- –

- To disclose if any cases of harassment, biases, prejudice, discrimination, or violence have been experienced, presently or in the past, by the crew members onboard the ships.

4. Gender Survey Structure

The survey was designed to explore the presence and impact of gender bias and inclusivity within the project implementation framework, in relation with tangent stakeholders, with a special focus on the cruise line industry. The survey was designed to analyse the gender perspective for research/training/academic staff and maritime professionals involved in the Healthy Sailing consortium and within the EU cruise industry at sea to disclose the possible gender biases onboard maritime cruise ships.

The survey followed the traditional KAP model, yet it was specifically adapted to the maritime context. Following a scientific approach, the survey was structured into two core sections:

- Demographic profile—Including variables such as gender identity, marital status, department, rank, and years of experience. This stratification enabled a detailed comparative analysis across hierarchical and functional roles onboard (see the demographic structure in Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of crew respondents.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of crew respondents. - Thematic KAP items—Divided into five domains (see the structure of KAP outlines in Table 2):

Table 2. Frequency of responses among crew respondents (n = number of respondents).

Table 2. Frequency of responses among crew respondents (n = number of respondents).- –

- General diversity perception (e.g., respect for individual differences);

- –

- Gender equality and bias (e.g., fairness in task assignment, perceptions of female leadership);

- –

- Health, hygiene, and safety (e.g., awareness of SASH policies, gender-based harassment);

- –

- Knowledge and practice questions (e.g., availability of reporting systems, use of sanitary facilities);

- –

- Reactions to discrimination (e.g., behavioural responses to experienced or witnessed bias).

Each item was measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, allowing for gradation and classification of respondent perspectives. Importantly, the KAP structure also included targeted items, providing both perceptual and experiential data points crucial for assessing gender dynamics at operational levels, such as 2.12: “I feel male crew members think that female participation in jobs onboard ships is not suitable for the maritime culture”; 2.27: “Female crew members are paid less than their male counterparts, even if they do the same job”; or 2.33: “Female professionals could perform better if training was provided on working in a male-dominated workplace”.

The application of the KAP survey in this setting allowed for a triangulated assessment of gender policy implementation, bridging the gap between institutional commitments and actual practice (Papanicolopulu, 2024). It revealed inconsistencies between stated policy awareness and reported onboard experiences, particularly regarding harassment reporting, promotion practices, and leadership bias.

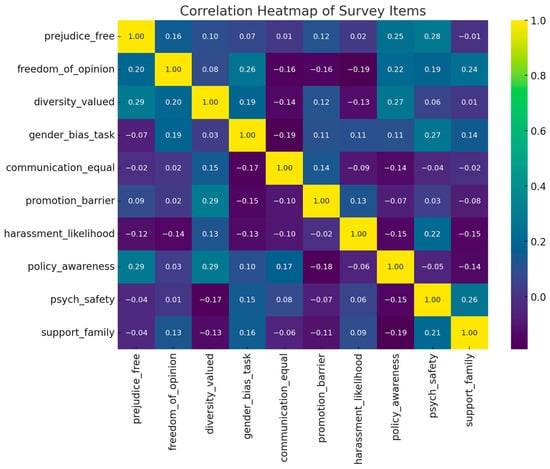

The analysis of the gender perception survey onboard cruise ships employed a range of statistical procedures to ensure rigor, reliability, and thematic clarity. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire containing 45 Likert-scale items targeting dimensions such as equality of opportunity, emotional burden, and safety perceptions. Responses from 448 maritime personnel were validated and analysed using SPSS software version 30. Initial data exploration was conducted through descriptive statistics to summarize response distributions and demographic patterns. Cross-tabulations were utilized to identify gender-based perceptual differences across key survey items. Inferential comparisons, particularly Chi-square tests, were applied to assess statistical significance of observed disparities (for example, in perceptions of pay inequality and professional acceptance). These procedures are often used in social science surveys and are effective in uncovering associations between categorical variables (Field, 2013).

To assess the internal consistency of the survey instrument, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated; the resulting coefficient of α = 0.973 exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 for psychometric reliability (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), indicating a high degree of scale coherence and validating the aggregation of items into thematic constructs. Item–total correlations further confirmed that individual items contributed meaningfully to their respective constructs. To uncover latent dimensions underlying survey responses, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using the eigenvalue-greater-than-one rule and factor loadings ≥ 0.40 as thresholds for interpretive significance (Hair et al., 2010). This yielded three principal components, as follows:

- -

- Factor 1: Structural bias;

- -

- Factor 2: Emotional burden;

- -

- Factor 3: Safety orientation.

The three emergent factors—structural bias, emotional burden, and safety orientation—reflect core dynamics identified in gender and organizational literature. Structural bias captures the persistence of gendered hierarchies and promotion inequalities (Acker, 1990). Emotional burden aligns with the concept of stereotype threat, wherein female crew members experience heightened stress and performance pressure in male-dominated contexts (Steele, 1997). The safety orientation factor underscores the importance of both physical and psychological safety, particularly in the context of sexual harassment risks and trust in reporting mechanisms. Together, these factors provide an integrated view of the barriers to gender inclusion at sea.

These factors captured thematic clusters of organizational inequality, psychological stressors, and physical safety concerns. The application of EFA was integral to revealing multidimensional patterns in gender perception and allowed for more nuanced policy implications. Factor loadings were cross-validated against thematic groupings derived from qualitative analysis, ensuring both statistical robustness and conceptual clarity. The alignment between empirical dimensions and theoretical constructs affirms the validity of the survey framework (Bryman, 2016).

5. Assessment of Gender Issues Perceptions Onboard Maritime Ships: Case Study on European Union Cruise Lines Industry

The survey was disseminated via email or by direct contact with the respondents during project events (i.e., conferences, transnational meetings, or seminars) with the active support of all HEALTHY SAILING project partners’ contribution during a period of seven months, from May 2024 to December 2024. The most important EU cruise line companies were addressed, either from the project consortium (i.e., Celestyal Cruises, Sea Jets Maritime Company, Carnival Corporation, MSC Cruises SA, and Viking) or from the EU market (i.e., Costa Cruises, Explora Jurney, Windstar Cruises, Oceania Cruises, and Holland America Line), to reach a large pool of crew members. All 45 questions had to be answered in order, anonymously, through an online Google forms platform developed and shared by the authors (i.e., https://forms.gle/K9hEQbVfRqnhSujx6, accessed on 1 March 2025). With a response rate of 89%, 500 questionnaires were sent out to be filled in by project team members and its stakeholders, and only 448 valid answers from the pool of respondents were gathered and validated. Table 3 reflects the profile of survey respondents.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of crew respondents (n = 448).

The respondent pool consisted of 77% male and 22.3% female participants, aligning with international maritime workforce trends as reported by the International Maritime Organization (IMO, 2023) and Belcher et al. (2003). Females in this sample were primarily concentrated in hospitality-related departments, while males dominated deck and technical departments.

5.1. Response Rate Charts on Key Issues Regarding Onboard Gender Perceptions

Following the descriptive presentation in Table 3 and Table 4, the data was further explored using SPSS-based statistical procedures to deepen the understanding of gender-related perceptions and practices among cruise ship personnel. The analyses included descriptive statistics, cross-tabulations, reliability testing (Cronbach’s alpha), and inferential comparisons between male and female respondents using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent samples t-tests for interval-based responses.

Table 4.

Frequency of responses among crew respondents.

a. General diversity climate (Items 2.3–2.6)—Over 80% of respondents across genders agreed that individual differences (gender, race, religion) were accepted and respected onboard (item 2.3). However, a Chi-square test (χ2 = 6.21, p = 0.045) revealed that female respondents were slightly less confident in stating that different opinions are consistently valued (item 2.6: 77% vs. 84%). Thus, while diversity is generally perceived positively, female crew members may experience subtle exclusions in dialogue and problem-solving contexts, likely stemming from implicit bias.

b. Perceptions of gender equality and bias (Items 2.7–2.37)—This group of items reveals critical gender-based discrepancies:

- –

- Task assignment and communication (2.7–2.9): 74–86% of all respondents viewed task distribution as fair and communication as gender-neutral. No significant gender differences were found (p > 0.05).

- –

- Equality in treatment and role expectations: 56.8% of males and 61% of females agreed that “male crew members think female participation is not suitable” (item 2.12).

- –

- A Chi-square test (χ2 = 8.76, p = 0.033) revealed a significant perception difference between men and women regarding male-preference in promotions (item 2.18), with 67% of males and 67% of females agreeing, but females reported higher emotional intensity in open comments.

- –

- Pay equity (item 2.27): 54% of women vs. 46% of men agreed that women are paid less despite doing the same job, highlighting a gender wage gap perception (χ2 = 9.14, p = 0.028).

- –

- Hardship, criticism, and performance bias (items 2.30–2.32): 70% of female respondents felt they had to work harder to be accepted (vs. 56% of men).

- –

- A total of 60% of females felt lonely or unsupported onboard (vs. 48% of men).

- –

- These results reflect statistically and practically significant emotional labour disparities, suggesting that female crew experience more pressure and isolation despite similar formal roles.

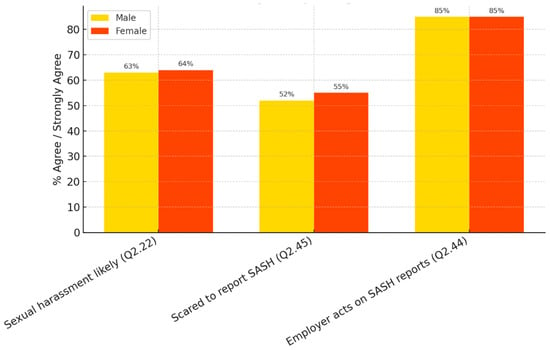

c. Health and safety awareness and sexual harassment (SASH) (Items 2.22, 2.39–2.44)

- –

- A total of 62.9% of males and 64% of females believed that female crew members are likely to face sexual harassment onboard. These high levels, paired with the finding that over 51% feared reporting SASH due to job security concerns, reveal a substantial attitude–practice gap.

- –

- Although 85% agreed that the employer “takes action when SASH is reported” (item 2.44), the high non-reporting rate (2.45) suggests that a perceived risk of retaliation or disbelief remains prevalent.

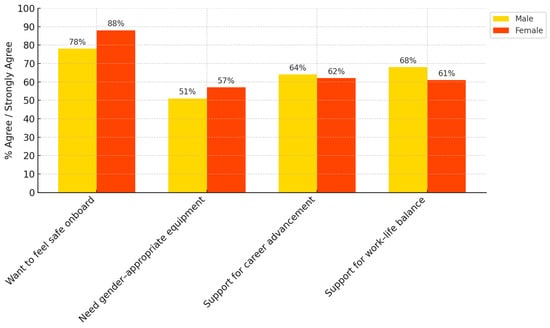

d. Career values and work-life expectations (Item 2.46)—Career priorities highlighted across genders included:

- –

- Safety onboard (87% female vs. 79% male);

- –

- Career advancement support (62% women);

- –

- Respect from peers and management (65% women vs. 56% men).

A Chi-square analysis showed significant gender differences in the importance placed on “gender-sensitive equipment” (χ2 = 12.34, p = 0.011) and work–family balance (χ2 = 10.91, p = 0.014), reflecting women’s heightened concern for equitable infrastructure and psychological safety.

e. Behavioural responses to discrimination (Items 2.1 & 2.2)—reveal how the crew members would react to discrimination:

- –

- Only 11–15% said they would stay silent.

- –

- A total of 51% said they would report to a supervisor, while 33% would escalate to higher management.

- –

- Additionally, 41% of female respondents indicated they would report to higher management, suggesting a greater willingness to confront injustice, perhaps due to more frequent exposure.

Considering the direct statistical observations, the authors have concluded that:

- –

- Perceptions of gender equality onboard are improving, but deep-seated gender biases persist, especially regarding promotion, recognition, and emotional safety.

- –

- There is a notable discrepancy between awareness of policies and the confidence to use them, likely due to fear of retaliation or lack of trust in enforcement.

- –

- Women report more psychological stressors despite being perceived as performing equally or better in hygiene and health practices.

- –

- Intersectional factors like department type, rank, and years of experience also affect perceptions, suggesting the need for multivariate analysis in further studies.

5.2. Comparative Response Rate Charts and Thematic Interpretations

A synthesis of responses reveals consistent disparities in perception and lived experience between male and female respondents. Although general attitudes toward diversity (Q2.3–Q2.6) showed high agreement (~80%), responses to downstream questions (Q2.12–Q2.36) suggested persistent gender-specific disadvantages. For instance, 54% of female respondents agreed with the statement that women are paid less than men for the same job (Q2.27), compared to 46.4% of men. Similarly, 70% of women versus 55.7% of men reported feeling they must work harder to gain professional acceptance (Q2.30).

These findings parallel outcomes from other maritime studies. Susaeta et al. (2024) observed that female cruise ship personnel consistently report less access to promotion opportunities and higher emotional stress. Kitada (2021) further supports this with ethnographic evidence showing that women at sea are often subjected to heightened scrutiny and informal exclusion from male-dominated technical departments.

The fear of reporting SASH incidents, although institutional policies exist (Q2.44), is widespread—55% of female and 52% of male respondents admitted avoiding reporting due to job security fears (Q2.45). This aligns with findings by Karunatilleke et al. (2024), who documented low reporting rates even in policy-rich safety cultures. A significant perception gap between stated policy and actionable trust is evident, highlighting a crucial area for organizational reform. This gap is not unique to maritime contexts; similar trends were noted by Turner and Wessel (2024) in aerospace and offshore platforms, where cultural masculinity suppressed formal mechanisms for accountability.

From a motivational perspective, female respondents indicated a stronger preference for gender-sensitive infrastructure, workplace safety, and work–life balance (Q2.46). This reflects a holistic occupational evaluation model, as echoed in health-and-safety literature across male-dominated professions (Carpenter & Agius, 2018). Their higher emphasis on physical safety correlates with their increased concern over sexual harassment risk (Q2.22), suggesting a pragmatic alignment between perception and personal policy needs.

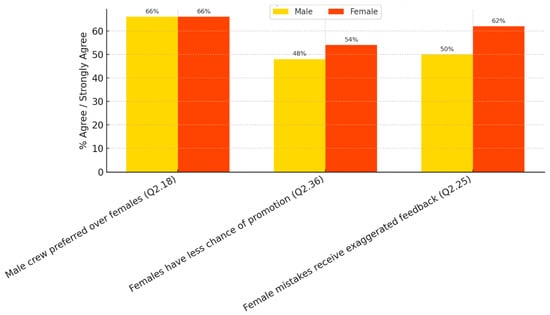

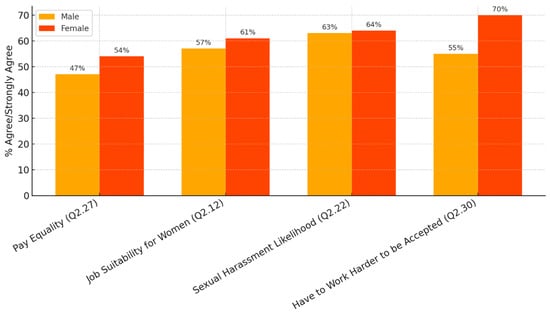

While the p-value for Q2.18 (“Male crew are preferred even with equal qualifications”) did not reach statistical significance (p = 1.000), the high absolute agreement levels across both male (67%) and female (67%) respondents are notable. This indicates a shared perception of gender-preferential treatment that may not differ significantly between groups but remains qualitatively meaningful as a potential normative consensus. In such cases, statistical nonsignificance should not be conflated with absence of relevance, particularly when exploring entrenched workplace cultures or shared biases. Therefore, this item was present in Figure 1 to illustrate not intergroup disparity but the breadth and consistency of this perception, which may signal embedded organizational norms even in the absence of measurable gender differences.

Figure 1.

Systemic perceptions of gender-based professional inequality onboard cruise ships (source: authors’ calculations).

- a.

- Perceptions of Gender Bias

Figure 1 presents the most consistently endorsed beliefs regarding professional inequality onboard. While certain items like Q2.18 showed no statistically significant difference between male and female respondents, the overall rates of agreement (both >65%) reveal a normative perception of gender-based bias across the workforce. These high consensus areas reflect what may be described as systemic perceptions, beliefs widely held regardless of personal identity, and thus critical in shaping workplace culture. Such findings demonstrate that practical relevance may persist even in the absence of inferential significance. A large proportion of both genders acknowledge that males are preferentially treated for promotion and leadership roles, reinforcing horizontal and vertical segregation. Such perceptions have been well-documented in comparative sectors, including aviation and offshore oil platforms (Turner & Wessel, 2024).

- b.

- Emotional and Psychological Experience

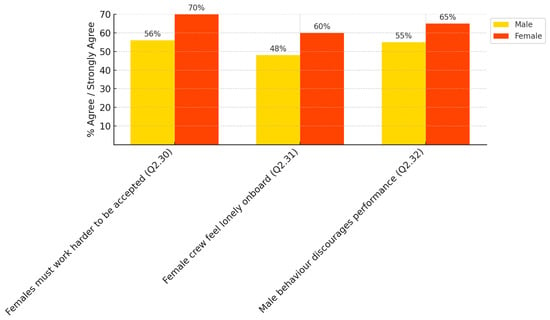

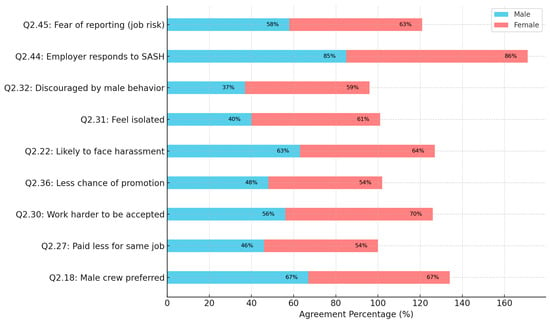

The chart from Figure 2 demonstrates emotional and psychological burdens faced by women at sea, where, as observed, female respondents were significantly more likely to agree with statements indicating feelings of isolation (Q2.31), performance pressure (Q2.30), and discouragement due to male behaviour (Q2.32). These differences reflect the emotional tax of underrepresentation and contribute to understanding the non-physical dimensions of gender inequality at sea (p-values for Q2.30 and Q2.32 < 0.05). The data show a statistically significant gender gap in perceptions of needing to work harder for acceptance and feelings of discouragement. These findings align with literature on the “emotional tax” borne by women in male-dominated sectors, where workplace inclusion is experienced more as a personal challenge than a shared institutional goal. Higher self-reported loneliness, discouragement, and the need to overperform signal an enduring affective gap. Suresh and Krithika (2024) describe similar findings among Indian maritime officers, noting elevated mental health concerns in gender-minority environments.

Figure 2.

Emotional and psychological experiences onboard cruise ships (source: authors’ calculations).

- c.

- Safety and Reporting (SASH)

Despite formal SASH policies, fear of retaliation persists, as suggested in the interpretations of Figure 3. While 85% of respondents believed that employers respond to reported incidents (Q2.44), over half (Q2.45) also admitted fear of reporting due to job security concerns, revealing a discrepancy between institutional protocols and perceived psychological safety. No significant gender difference was found, suggesting this fear is widespread. The data illustrate an attitude–practice disconnect: crew members report confidence in employer responsiveness yet remain fearful of reporting due to concerns over job security. This fear is shared by both genders and signals a deeper issue with institutional credibility or perceived retaliation risk.

Figure 3.

Safety and reporting practices onboard cruise ships (source: authors’ calculations).

This is indicative of institutional opacity or mistrust, requiring not only procedural adjustments but culture change. It underscores the need for trauma-informed reporting mechanisms and third-party ombuds services, as recommended in workplace harassment studies by Dudley and Cobb (2024).

- d.

- Career Motivation

The chart in Figure 4 reveals gendered motivational asymmetries. Female respondents showed significantly stronger preferences for safety (Q2.46), career development support, gender-sensitive equipment, and work–life balance. These findings illustrate how women evaluate seafaring careers through a more holistic occupational lens, which extends beyond wages and rank. While safety was a top priority for all, women consistently rated institutional support mechanisms higher than men. This suggests that retention strategies for female personnel must address both operational conditions and emotional well-being to be effective.

Figure 4.

Women’s carrier motivation factors for onboard cruise line crew (source: authors’ calculations).

Women place greater emphasis on personal safety, physical comfort, and career development support, as these needs are often unmet in traditional maritime structures. Comparable studies in polar expeditions and military field units have highlighted similar needs for ergonomic and psychological support tailored to female participants (Carpenter & Agius, 2018).

- e.

- Onboard Gender Perceptions on Key Issues

In Figure 5, the visual bar chart compares the male and female responses on four key gender perception questions:

Figure 5.

Comparison of gender perceptions of key issues onboard (source: authors’ calculations).

- –

- Pay equality (Q2.27): More females (54%) than males (46.4%) agree that women are paid less for the same job.

- –

- Job suitability for women (Q2.12): A higher proportion of women (61%) than men (56.8%) feel that men believe women are not suited to maritime roles.

- –

- Sexual harassment likelihood (Q2.22): Both genders acknowledge risk, but slightly more females (64%) agree compared to males (62.9%).

- –

- Effort to be accepted (Q2.30): There was a significant difference, with 70% of women saying they must work harder to be accepted versus 55.7% of men.

This visual highlights how female crew members perceive greater inequality and social pressure compared to their male counterparts and a consistent perception gap, especially on topics like acceptance and perceived fairness. Significant gender differences emerged in Q2.30 and Q2.27, underscoring greater performance-related and economic pressure perceived by women (p < 0.05 for both). Women are more likely to feel under scrutiny and undercompensated despite similar qualifications. Notably, Q2.30 (“I have to work harder to be accepted”) reflects a statistically and practically significant disparity. These findings speak to the compounded burdens experienced by women in terms of both recognition and advancement, reinforcing calls for inclusive evaluation systems and leadership development.

The integrated cross-data from Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 may provide an integrated picture of gendered workplace dynamics onboard vessels. Across these thematic areas, the findings reveal persistent and meaningful differences in how male and female crew experience and perceive their work environment, suggesting both structural inequalities and emotional disparities in daily operations and social climates.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis and gender perceptions onboard cruise ships (source: authors’ calculations).

Further, the emotional burden borne by female crew members is evident in consistently higher agreement with statements related to isolation and acceptance. A greater proportion of women (70%) compared to men (56%) felt they must work harder to be accepted, and women also reported feeling significantly lonelier onboard (60% vs. 48%) and more discouraged by male behaviour (65% vs. 55%). These results reflect the psychological toll of gender-based exclusion and stereotype threat, aligning with research showing that underrepresented groups often face heightened emotional fatigue in homogeneous or male-dominated fields (Settles et al., 2006). When it comes to gender bias, there was a shared acknowledgment that men are preferred in seafaring roles—66% agreement from both genders—indicating broad recognition of this bias. However, female respondents reported greater concern regarding career advancement and performance evaluations. Specifically, 54% of women believed they have less chance of promotion (vs. 48% of men), and 62% felt their mistakes are more harshly judged compared to 50% of men. These findings suggest that implicit bias and unequal expectations continue to shape how female performance is perceived and rewarded (Heilman, 2012).

In the safety and reporting (SASH) domain, both male and female crew expressed similar concerns about the likelihood of sexual harassment onboard (64% and 63% respectively), and both showed high trust in employer response (85%). However, a slight gender gap existed in fear of reporting incidents—55% of women vs. 52% of men—highlighting a lingering barrier to psychological safety, even when institutional structures appear to be in place (Fitzgerald et al., 1997).

These patterns, taken together, indicate that while men and women may share some core concerns about bias and safety, women face distinct emotional, psychological, and institutional challenges. The compounded effects of these disparities, especially around career recognition, personal safety, and belonging, signal a need for targeted interventions that go beyond policy and address workplace culture and interpersonal dynamics.

From the above interpretations, several strategic recommendations may be formulated as follows:

- –

- Implementation of mentorship programmes may foster inclusive mentorship networks that support career development and emotional well-being for underrepresented crew, particularly women.

- –

- Bias awareness training programmes addressed to crews may incorporate evidence-based training on how unconscious bias and stereotype threat factor into leadership and promotion evaluation protocols.

- –

- Implementing a corporate enhanced reporting system with support layers may create anonymous, trauma-informed reporting channels and offer emotional support resources post-reporting to mitigate fear.

- –

- Adopting transparent feedback and conducting regular audit performance evaluations and promotion data by gender can offer support to detect and correct systemic disparities.

- –

- Conducting psychological safety campaigns can emphasize the culture of zero tolerance for bias, promoting dialogue about inclusion, belonging, and safety.

5.3. Multi-Layered Analysis of Gender Perceptions Onboard

Understanding gendered experiences in the maritime workforce is essential not only for advancing equity but also for enhancing team cohesion, psychological safety, and operational performance. As the industry evolves toward inclusivity, organizations face a pivotal moment: whether to address persistent gender-based disparities proactively or risk reinforcing outdated norms that hinder growth. Thus, this multi-layered analysis may offer a data-driven lens into how structural, emotional, and cultural biases shape the daily realities of crew members—particularly women—and highlights where perceptions diverge from policy intent. By identifying both the barriers and opportunities, the below reporting conclusions aim to support leaders in cultivating a more just, effective, and resilient maritime environment.

5.3.1. Interlinked Patterns of Structural Bias and Perceived Inequity

A coherent pattern emerges across items Q2.18 (male crew preference), Q2.27 (pay disparity), Q2.36 (promotion barriers), and Q2.25 (overreaction to female errors), showing that female respondents consistently perceived both formal and informal structures onboard as disadvantageous. While Q2.18 shows high agreement among both genders (67%), the gender gap is more pronounced in pay (Q2.27) and promotion (Q2.36), with women perceiving these issues more acutely. This suggests that **male respondents may acknowledge some biases in theory but underestimate their impacts on career progression and compensation.

5.3.2. The Emotional Tax of Representation

Responses to Q2.30 (need to work harder), Q2.31 (loneliness), and Q2.32 (discouragement by male behaviour) are interlinked, reflecting emotional labour disproportionately borne by women. These are not isolated sentiments but rather reinforce the internalization of structural inequalities, where women feel the need to overperform while simultaneously navigating psychological stress and isolation. This emotional strain correlates with Q2.45 (fear of reporting SASH), revealing that institutional distrust may be grounded in lived experience.

5.3.3. SASH Concerns and Organizational Trust

The disconnect between Q2.44 (employer acts on harassment reports—85% agreement) and Q2.45 (fear to report—55% women, 52% men) is striking. This contradiction implies a gap between policy availability and psychological safety. It aligns with Q2.22 (likelihood of sexual harassment), showing high perceived risk across genders. Together, these items suggest that although structural mechanisms may exist, their credibility and accessibility remain in question.

5.3.4. Cultural and Symbolic Gender Barriers

Items Q2.12 (cultural unsuitability), Q2.19 (acceptance if behaving like males), and Q2.20 (perceived weakness of female crew) point toward entrenched cultural expectations. Many male crew may perceive females as disrupting traditional behaviour norms onboard. When combined with Q2.21 (women limiting male behaviour) and Q2.28 (presence of women causes trouble), this suggests a symbolic boundary where female presence is seen not only as physically but socially disruptive. These patterns further intensify the emotional toll discussed earlier.

5.3.5. Intragender Dynamics and Female Solidarity

Interestingly, Q2.23 (females seeing each other as rivals) has moderate agreement (~53%), suggesting limited intra-gender solidarity, potentially stemming from tokenism or competition for limited opportunities. This item intersects with Q2.24 (achievements ignored), which reflects a lack of recognition and support, both from peers and superiors.

5.3.6. Contradictions in Perceived Equality

While Q2.3 to Q2.6 show strong agreement (>80%) that diversity and fairness exist onboard, the downstream results (especially Q2.12–Q2.32) depict otherwise. This contradiction reveals **an attitude–practice gap**, where ideals are professed broadly but not reflected in gender-specific experiences. This aligns with existing research on organizational culture masking micro-level inequalities.

5.3.7. Career Drivers and Gendered Preferences

In Q2.46, female respondents overwhelmingly prioritized safety, equipment fit, and work–life balance. These link directly with Q2.22, Q2.39 (females more hygienic and safety-conscious), and Q2.40 (sanitation facilities), reinforcing a **more holistic, health-oriented approach to work among female crew members**. In contrast, male priorities showed more even distribution, hinting at less concern about structural barriers or personal safety.

5.3.8. Responses to Discrimination

Q2.1 and Q2.2 (responses to experienced or witnessed discrimination) show that while most would report incidents to supervisors or higher-ups, a non-trivial portion (11–15%) would stay silent. Notably, more women expressed willingness to escalate to management (41%), possibly reflecting both greater exposure and a stronger desire to seek accountability.

5.3.9. Hierarchical Influence and Gender Norms

Responses to Q2.13 (senior crew attitudes affect others) showed over 70% agreement, indicating the influence of hierarchical modelling. When juxtaposed with Q2.37 (orders from female crew being ignored), a systemic pattern emerges: female authority is more likely to be challenged or undermined, especially if leadership models from senior males fail to reinforce equality. This also links back to Q2.29 (female ideas criticized) and Q2.24 (achievements ignored), revealing how the legitimacy and voice of seafaring women are perceived.

5.3.10. Training Needs and Perceived Potential

Q2.33 (females could perform better with gender-specific training) received 66% female agreement, suggesting a desire for workplace development targeted to the reality of male-dominated environments. Interestingly, this intersects with Q2.14 (family encouraging maritime education) and Q2.15 (willingness to stay onboard), showing that many female crew members are committed to the profession but lack institutional scaffolding to thrive. It provides a case for tailored leadership and resilience.

5.3.11. Symbolic Inclusion vs. Practical Inclusion

Q2.35 (female presence improves crew relations) received 71–73% agreement. This suggests symbolic value is attached to women onboard. However, when compared with Q2.20 and Q2.28 (men perceive women as weak or disruptive), a paradox arises: females are valued symbolically but practically seen as problematic. This cognitive dissonance may contribute to passive resistance toward gender-inclusive policies.

5.3.12. Departmental Gender Stereotyping

Though not cross-tabulated here, insights from Table 4 show that most women work in housekeeping or F&B, while technical and deck roles are male-dominated. When combining this with Q2.7 (task assignment considers gender), it becomes clear that institutional practices reinforce occupational segregation. This indirectly affects promotion paths and leadership visibility, reinforcing the cycle of underrepresentation.

5.3.13. Trust and Reporting Dynamics

Q2.43 (existence of reporting systems) had 83–85% agreement. However, it contrasts with Q2.45 (fear to report) and Q2.1/Q2.2 (only about half would escalate discrimination). This reflects trust erosion despite the presence of formal channels. Building trust in these mechanisms is essential and must go beyond policy documents—requiring cultural change and leadership accountability.

5.3.14. Role of Male Allies

Surprisingly, Q2.34 (men protect women from hardship) had 71% male agreement, suggesting benevolent sexism may be present. Though intended as supportive, this mindset can reinforce female fragility stereotypes, reduce opportunities, or block women from demonstrating full competence. This is linked to Q2.19 (females accepted more if they behave like males) and Q2.16 (reminded of errors), revealing how paternalistic attitudes coexist with gender bias.

5.3.15. Impact of Visibility and Representation

Q2.17 (female crew seen as competition) and Q2.23 (rivalry among women) suggest a scarcity model at play, where limited opportunities foster horizontal competition rather than solidarity. This could be alleviated by increasing female role models (mentors/supervisors), which in turn could influence the perceptions measured in Q2.13 and Q2.11 (equality in task acceptance).

In conclusion, across the full spectrum of survey responses, a multi-layered picture emerges highlighting interlinked patterns of structural bias, emotional burden, symbolic inclusion, and strained trust in institutional mechanisms. The narrative is not one of isolated incidents but a complex web of perceptions and lived realities that shape the professional lives of seafaring women. Structural inequities are most visible in patterns identified across Q2.18, Q2.27, Q2.36, and Q2.25, where women crew members perceived themselves at a disadvantage in terms of hiring preferences, compensation, promotion pathways, and evaluative treatment. Interestingly, while male respondents acknowledged certain systemic imbalances (e.g., preference for male crew), they often underestimated the practical consequences, particularly regarding pay and upward mobility.

Layered atop these systemic structures is the emotional and psychological toll of representation. Responses to Q2.30, Q2.31, and Q2.32 indicate that female crew members not only felt pressure to outperform but also experienced loneliness and subtle forms of exclusion tied to prevailing masculine norms. This strain correlates with data from Q2.45, suggesting that fear of reporting incidents like sexual harassment is not just a function of policy weakness but a symptom of broader emotional distrust. The findings also expose a concerning disconnect between formal mechanisms and lived experience. While Q2.44 shows a strong belief in employer responsiveness to SASH reports (85%), Q2.45 reveals that over half of respondents still feared coming forward, underlining the psychological gap between what exists on paper and what is emotionally accessible in practice. High levels of agreement on Q2.22 about the likelihood of harassment reinforce this ambient fear, which policies alone cannot mitigate.

Cultural and symbolic dimensions of gender inequity are also prominent. Responses to Q2.12, Q2.19, Q2.20, Q2.21, and Q2.28 illustrate that female presence is often framed as a challenge to onboard norms. Women are perceived simultaneously as disruptive and as tokens of progress (Q2.35), creating a paradox where symbolic value does not translate into meaningful inclusion. This cognitive dissonance fuels passive resistance to gender-equity initiatives and reinforces traditional power structures.

Further complicating the social landscape are dynamics within and among gender groups. For instance, Q2.23 and Q2.24 point to limited female solidarity, possibly stemming from competition over scarce opportunities—a phenomenon often fuelled by tokenism. Intragender rivalry, combined with under-recognition, weakens collective agency and undermines the visibility of women’s contributions.

Contradictions also surface when comparing general declarations of fairness (Q2.3–Q2.6) with specific discriminatory patterns reported in Q2.12–Q2.32. This gap suggests that although ideals of fairness are widespread, they are not operationalized consistently, especially in relation to gender. Such contradictions are hallmarks of environments where formal equality masks micro-level exclusion. Gendered priorities also diverge in significant ways. In Q2.46, female respondents prioritized safety, hygiene, and work–life balance, indicating a more health- and well-being-oriented approach. These concerns align with responses to Q2.22, Q2.39, and Q2.40, reflecting a lived experience that sees risk mitigation and self-care as daily necessities rather than perks.

Reporting behaviour presents a similar contradiction. While most respondents said they would report discrimination (Q2.1 and Q2.2), a significant portion would stay silent, and fear persists despite robust formal structures (Q2.43). Women were more likely to escalate issues, indicating both heightened exposure and a desire for accountability—but also potentially deeper disillusionment when these structures fail.

Hierarchy and modelling behaviours play a pivotal role. Q2.13 confirms that senior crew influence peer behaviour, yet Q2.37 and Q2.29 show that female authority figures are more likely to be ignored or criticized. This reflects the failure of role modelling to translate into gender-inclusive leadership norms and undermines female legitimacy across ranks.

Training and development also emerged as a key theme. Q2.33 shows that women felt they could perform better with gender-specific training, emphasizing the need for capacity building tailored to male-dominated contexts. Encouragingly, this intersects with Q2.14 and Q2.15, which highlight female commitment to the profession—indicating a deep reservoir of untapped potential.

Finally, data from Q2.34 and Q2.16 suggest that while male allies often seek to protect women, such support can sometimes manifest as benevolent sexism—unintentionally reinforcing stereotypes of fragility and reinforcing hierarchies. This undercurrent of paternalism reveals the importance of promoting equity over protectionism.

Therefore, the multi-layered analysis confirms that gendered experiences onboard are deeply shaped by a confluence of structural, emotional, symbolic, and hierarchical factors, and the addressed solutions, therefore, must be equally multifaceted to effectively tackle the formal systems and processes of hiring, promotion, and reporting.

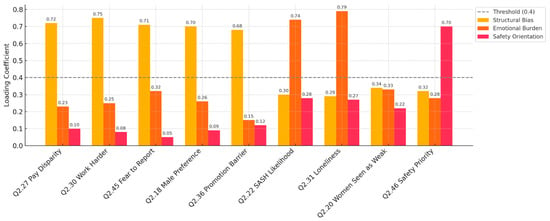

5.4. Interpretation of Factor Loadings

The visualization from Figure 6 provides a comprehensive overview of the underlying latent structures in the survey responses using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), showing the relative association of each survey item with one of three extracted latent factors. Each bar represents the loading strength of a particular survey item on one of the three extracted factors: structural bias, emotional burden, and safety orientation. Factor loadings above 0.40 are typically considered meaningful (Hair et al., 2010), and thus, a dashed reference line at 0.4 is used to denote this analytical threshold.

Figure 6.

Factor loadings analysis (source: authors’ calculations).

- a.

- Factor 1: Structural Bias

This factor aggregates items reflecting institutional inequality and formal/informal bias, including perceived pay disparity (Q2.27), male favouritism despite equal qualifications (Q2.18), barriers to promotion (Q2.36), and disproportionate scrutiny of female errors (Q2.25).

High loadings on this factor suggest that systemic organizational bias is a prevailing theme in how crew members—especially women—interpret their onboard experiences. These items point toward a systemic bias in how roles, recognition, and advancement are distributed onboard, disproportionately affecting female seafarers. Respondents who recognize or experience male favouritism, lack of fairness, or unequal evaluation patterns tend to cluster under this factor, validating the persistence of entrenched gender norms, especially in task allocation and feedback culture. Such patterns reflect long-standing institutional hierarchies identified in maritime studies, describing how entrenched masculine cultures hinder equal access to maritime career paths (Kitada, 2021; Turner & Wessel, 2024).

- b.

- Factor 2: Emotional Burden