Abstract

This study presents a process narrative of how cooperatives emerge during periods of economic disruption. Cooperative organizations are pluralistic and embedded in existing local economic contexts. Yet, the role that such organizations play can be pronounced when economic disruption occurs in the absence of well-established institutions to support cooperative ideology. This study uses the Structuration and Panarchy frameworks to examine the dynamics of Amul’s emergence, where individual producers organized against the existing structure of production in a period characterized by reorganization at the broader macro level. The study complements insights from economic and social perspectives while presenting a view of how individuals organize economically in the context of disruption. The narrative broadens the view of when collective action becomes possible and what explains sustained socio-economic value creation from such enterprises.

1. Introduction

The emergence of social development enterprises such as cooperatives continues to attract research attention (Boone & Özcan, 2014; Hote, 2021). Agency theories of emergence highlight the role of individual human intentionality, foresight, and self-reflexiveness in bringing about change and discontinuity in economic systems. These theories view individuals as autonomous and active contributors to the formation of organizations through their self-regulated and goal-directed actions (Shogren et al., 2017). These theories pay less attention to the role of structures that shape rules and resource distribution. Structuralist views, on the other hand, uphold the primacy of the broader institutional and industry structures in bringing about adaptive change (Lounsbury & Ventresca, 2003). These perspectives have been noted for their determinism and over-socialized views (Granovetter, 1985), and for underemphasizing strategic intent (Etzioni, 1967; Smith & May, 1980; Whittington, 2007; Jarzabkowski, 2005; Chatterjee et al., 2019).

Highlighting a dichotomy presented by existing views, strategy scholars call to examine process-oriented accounts of organizational action (Greve & Rao, 2012; Whittington, 2007; Tsoukas, 2009). Social development enterprises often emerge through the collective and sustained actions of large groups working together to solve shared challenges (Schneiberg et al., 2008). Two underlying conditions are prominent. First, the presence of a stimulus, such as a set of shared concerns, that triggers collective action (Stephan et al., 2015; Whittington, 2010; Weber et al., 2008). Second, the presence of well-established institutional or organizational structures can facilitate the resolution of existing concerns. (Bruton et al., 2010; Estrin et al., 2013; Stephan et al., 2015).

Yet, cooperatives emerge in environments where these very structures remain disorganized. In such contexts, shared values are not yet realized, and institutions or organizing structures are not yet developed. Even though cooperative organizations are pluralistic and involve stakeholders, the process by which stakeholders organize among themselves continues to need research attention. In addition, even though cooperatives are embedded in existing local economic and institutional contexts, this is an outcome rather than a trigger. While studies doubt that economic incentives adequately explain cooperative formation (see Boone & Özcan, 2014 for a discussion), economic disruption can be a trigger for collective action. This can be pronounced in the absence of well-established infrastructure to support cooperative ideology.

This study draws on the historical narrative of Amul Coop in India to explore the process by which shared values and organizing structures took hold in the context of economic disruption and institutional voids. The Structuration and Panarchy frameworks are used to examine the process of how individual producers organized against an existing structure of production, at a time when reorganization was in progress at the broader macro level. This study aims to complement views from economic and social perspectives by studying cooperative formation from a processual approach. It presents a complementary view of how collective action was possible and how this created a sustainable cooperative enterprise.

The study was conducted by combining historical accounts with field observation and secondary data collection. The field study involved observing the structure and function of the cooperative. Field observations were combined with archival data to construct a narrative of the emergence of the cooperative, with the goal of understanding how such organizations emerge in hostile environments in the absence of institutional support. The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents a brief literature review on cooperatives and highlights the research opportunity that is addressed in this study. Next, we outline our research methodology, where we discuss sample selection, research setting, and outline the approach of describing the case using a processual narrative to delineate its founding and sustained operations.

2. Background Research on Cooperatives

Cooperatives are a distinct organizational form that evolves around voluntary self-help, open membership, democratic member control, member participation, and concern for community. Such organizations combine goals like empowerment, member access to markets and services, securing livelihoods, and preventing exploitation, with means to facilitate collective participation in economic activity (ICA, 2009). The democratic organization and pursuit of hybrid socio-economic goals distinguish them from organizations that primarily seek economic profit (A. G. Johnson & Whyte, 1977). In cooperatives, market relations between a corporation and its consumers or producers are replaced by relations of ownership, control, and collective self-provision (Schneiberg et al., 2008). The dual nature of “association and enterprise” inherent in cooperatives (Michelsen, 1994; Spear, 2000) makes them more pluralistic (Denis et al., 2007). Cooperatives combine social and economic objectives, with a diffuse power distribution that allows a wide array of constituents and stakeholders to influence the nature of goals pursued and the means adopted, unlike what may be expected in traditional firms (Ring & Perry, 1985).

Both economic and social outcomes of cooperatives have been explored in the management literature. Cooperative formation has been linked to economic factors such as market failures or depressed prices (Cook, 1995). Associative factors, normative beliefs, and social movement forces have also been examined (Spear, 2000). These studies complement the economic motive with the view that decision makers are embedded within a local socio-economic context (Granovetter, 1985). In this manner, cooperatives are formed when other corporations present a threat (economic motive), when there is an anticorporation mindset (shared nonpecuniary concern), and when well-established organizational infrastructures are present to aid the emergence of the cooperative (Boone & Özcan, 2014).

While outcomes are important, it is imperative to examine the processual dynamics by which outcomes are produced in the first place. These include processes of founding and of achieving scale economies. Process-oriented explanations allow us to explore multiple rationales that go beyond conventional economic ones posited for the formation and growth of organizations (Van de Ven, 1992; Regnér, 2008; Pettigrew, 1992; Langley, 1999). The trigger for the formation of coops may come from movements. For example, Schneiberg et al. (2008) show how an anti-corporate movement in the US influenced the formation of a cooperative. Examining these processes allows an embedded or context-oriented understanding of phenomena such as formation and growth within broader contexts to complement findings from static, ahistorical, and functional explanations (Granovetter, 1985).

Strategic management researchers have specifically argued for greater attention to the economic, social, and cultural context in which cooperatives emerge (Whittington, 2007; Tsoukas, 2009). Though strategy process researchers have revealed the importance of organizational context, there is a need to specifically recognize the macro embeddedness [of strategy] as well (Whittington, 2007). Macro embeddedness refers to the connection between firm-level and macro-level events. Studying such linkages can help understand how strategies relate to events and occurrences at the macro level, emphasizing the interactional nature of strategy. Other researchers have called for expanding the notion of embeddedness to include cognitive, cultural, and political dimensions (DiMaggio & Zukin, 1990; Baum & Dutton, 1996). Such an expanded and nuanced conception of embeddedness, which recognizes the nested nature of economic actions within processes at multiple levels of analysis and which recognizes both the enabling/constraining and constitutive influences of these, is key to enunciating a more realistic view of “how and why” social enterprises emerge and evolve. Thus, an embedded approach to strategy formation is dynamic “draw[ing] attention to both nested and constitutive aspects of context” (Dacin et al., 1999).

More specifically, there is a need for more management research on cooperatives, focusing on the contextualized understanding of cooperatives’ strategy processes that underlie their emergence and evolution. Studies of coops in management literature have dealt with either macro issues that seek to study organizational formation using the notion of population dynamics (see Simons & Ingram, 1997; Ingram & Simons, 2000; Carroll et al., 1988; Staber, 1989; Whittington, 2015) or with micro issues that look at membership identity, commitment and participation (Foreman & Whetten, 2002; L. H. Brown, 1985; Woodworth, 1986). Connecting the micro and macro levels of analysis using an embeddedness approach can advance understanding (Regnér, 2008). This study intends to bridge this gap by providing a processual and embedded understanding of the emergence of coops in their context.

3. Historical Analysis: Emergence and Strategy Formation of Amul

3.1. Methodology

This study uses historical information to develop a narrative of the strategy process underlying the founding and development of a cooperative organization. This treats strategy as a state of becoming rather than one of being (Pettigrew, 1992), following the approach taken by studies of strategy process. The approach is to first gather historical information about individuals, communities, institutions, economic events, and movements. This is compiled in the form of a historical narrative on how past events shaped a focal outcome. The “narrative approach” (Fenton & Langley, 2011; A. D. Brown & Thompson, 2013) to understanding strategies underlying the emergence of organizations proceeds by taking stock of significant shifts through social events, policy changes, economic hardship, emergent behaviors, collective action, inclusion of prominent individuals, movements, and their eventual impact. Once this narrative is presented, the information is analyzed using theory to develop plausible and nuanced interpretations of how social enterprises are founded in the context of hostile environments. This approach allows us to understand the creation and development of cooperative organizations by understanding when collective action is possible to create value, where state-level policies may not be feasible or appropriate.

Historical analysis has re-emerged in importance in strategic management (Argyres et al., 2020). The importance lies in the need to examine time-extended longitudinal data, which historians utilize to create narratives and interpretations. Early scholars (Pettigrew, 1992) recognized the importance of historical analysis in the pursuit of strategy research, highlighting the importance of being able to conduct explorations as historians do. This can help understand how the content of major transformation is linked to the context and the processes that evolved over time. This leads scholars of strategy process to argue for longitudinal, process-based views of organizational founding and development (Van de Ven, 1992; Pettigrew, 1992; Mintzberg, 1979). This involves examining sequences of incidents, activities, and actions unfolding over time.

With this approach, strategy formation has been studied in private firms, government agencies, and public bodies (see Mintzberg & Waters, 1982; Mintzberg, 1978; Pettigrew, 1985). Management scholars continue to champion the need to break out of the “normal straight science jacket” (Bettis, 1991; Daft & Lewin, 1990; Powell & DiMaggio, 2023). This involves advancing micro-understandings of “what people really do” (G. Johnson et al., 2007; Jarzabkowski, 2005; Fenton & Langley, 2011). This study follows such a tradition, examining a longitudinal sequence of events and activities performed by actors as their starting point, and uses in-depth narratives of these event sequences, activities, and choices to develop explanations for the phenomenon based on an understanding of temporal evolution (G. Johnson et al., 2007).

3.1.1. Study Location & Sample Selection

This study is therefore a qualitative inquiry of a case using a purposive or theoretical sampling strategy. This contrasts with the approach in quantitative studies, where large samples are gathered using random selection to solve selection bias problems. In qualitative enquiries, cases are chosen for theoretical rather than statistical reasons (Patton, 2002; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Eisenhardt, 1989). Such deliberate choice of research sites (samples) is common in qualitative longitudinal studies and made to “choose cases which are likely to replicate or extend emergent theory” or to fill “theoretical categories and provide examples of polar types” (Eisenhardt, 1989) in which the process of interest can be observed. These two types of sampling are appropriate for different purposes. While the “purpose of random sampling is generalization from sample to a population” and control of selection bias, the objective of purposeful sampling is to “learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry” (Patton, 2002). Given that the purpose of this study is to gather in-depth knowledge of the strategy formation process in coops, purposeful sampling is appropriate.

The founding of AMUL in 1946, prior to Indian independence from British rule, presents an excellent context to advance strategic management research on cooperatives. This is an information-rich case with extensive research attention that can be used for an in-depth understanding of founding and strategy formation. The case of Amul presents the opportunity to learn from what is considered an “exemplar of good practice” (Patton, 2002) without making any claims of a grand theory. The purposeful sampling of a positive outlier is, therefore, a legitimate choice.

Amul was established in December 1946 as a District Milk Producers’ Union of two Village Milk Cooperative Societies in Anand town of Kheda district of Gujarat. When it started out, Amul was a fragile experiment, based on an emancipatory vision for Kheda’s farmers. After slow growth in the initial years, Amul picked up momentum once technocrats joined the organization. Amul grew from a Union of two cooperatives, with some 60 members and a daily procurement of about 250 kgs of liquid milk in 1946, to a Union with 138 Village Cooperative Societies (VCS), 33,000 members, and an annual procurement of 27,500,000 kg of milk, along with the capability of manufacturing and marketing branded AMUL butter, milk powder, and condensed milk by 1958. By 1968, AMUL had successfully organized 148,000 producer members in 600 VCS, which collectively procured 113 million liters of milk for AMUL (Source: Amul Dairy). By this time, AMUL was successfully running a balanced cattle feed plant for its members, operating a modern Bull Station for collecting liquid semen from high pedigreed buffalo bulls for the provision of Artificial Insemination (AI) services to all members, and offering popular veterinary service in two variants—cost free veterinary routes as well as priced veterinary emergency services. During this period, AMUL had successfully diversified its portfolio to include products such as baby foods and processed cheese (Source: Amul Dairy).

3.1.2. Study Design

The historical content was gathered and organized in a manner consistent with narratives of rare, interruptive, and salient events (Meyer, 1982). The narrative starts with a discussion on the prevailing socio-cultural aspects of the Patidars, the agrarian community that played an important role in AMUL’s founding. This serves as the background social context of the subsequent economic disruption experienced in the region. The environment of economic disruption immediately prior to AMUL’s founding is discussed next. This is considered the environmental context that led to self-organization by the Patidars. Studies of rare events (Hertwig et al., 2004; Meyer, 1982) describe how the occurrence of a disruptive event triggers an organized response. The self-organization response of cooperative formation is described next. Then, enabling and constraining factors are integrated and examined using the Structuration and Panarchy frameworks to advance a narrative of how AMUL emerged.

3.2. A History of Self-Organization and the Introduction of Economic Disruption

The narrative revolves around Patidars, who were the primary group affected by economic events in the years prior to the foundation of Amul. Patidars were generally characterized as collaborative and hard-working, with a strong view towards solidarity and collective progress (Trivedi, 1992). Accounts from the time suggest that the notion of joint family—where many nuclear families live together—was a dominant culture and a matter of pride (Pocock, 1972). Joint families not only promoted greater solidarity but also served a functional role. For instance, collective financial and family resources helped support marriages, which typically involved high ceremonial expenses (Heredia, 1997). Those who migrated away would yet maintain ties with their villages through joint land ownership and would extend financial help to extended families. The Patidar culture, therefore, placed high value on kinship relations and orientation. Even though they were parsimonious, the Patidars donated generously to societal goods like charities, trusts, and hospitals (Pocock, 1972; Heredia, 1997). Donations in the 1930s established the Institute of Agriculture, Charotar Education Society, and Charotar Rural Development Trust. The Rural Development Trust helped small enterprises and entrepreneurial initiatives. The share of profits from these operations eventually found their way to the construction of the Sardar Patel University. It was built by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and farmers of Kheda in the late 30s with a College of Engineering and Architecture, which was managed by those of academic merit and proven practical experience—some with Ph.D. degrees from the West (Hardiman, 1981; Heredia, 1997).

3.2.1. Prior Emergent Movements: The Satyagrahas of the 1920s and 1930s

Satyagraha refers to an organized refusal to cooperate. Such movements often started with emergent processes, involved leaders such as Mohandas Gandhi, who coordinated behaviors by visiting people across distant locations, and persisted with steadfast behaviors that were propelled by self-organization. The region had seen a series of Satyagraha movements against British rule, such as those in Champaran and Kheda (Hardiman, 1981). The events at Kheda unfolded in 1918 following a crop failure, which led to widespread economic hardship among the Patidar farmers (Bates, 1981). The British government insisted on an increased collection of land revenue, ignoring the famine code that allowed consideration for crop failures (Brennan, 1984). Following this, the farmers organized. The narrative is that local leaders invited Gandhi to lead the movement (records at Mani Bhavan, n.d.), who saw an opportunity to apply the principles of resistance he had previously written about (R. L. Johnson, 2006). The goal became to facilitate coordination among Patidars across the region to refuse to pay taxes until the British government considered their demand for tax relief. The coordination was achieved by visiting farmers across the region, educating them about their rights, and organizing their actions. As a result, the farmers organized and remained steadfast through a period of British repression that included confiscation of property and arrests. The satyagraha was withdrawn after the government agreed to suspend taxes for the year (Source: Indian Culture Portal).

A similar event occurred close to Anand in Bardoli in 1928 when the government of the Bombay Presidency raised taxes significantly amidst a famine. Gujarati activists collaborated with farmers and village chiefs to invite Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel to organize the resistance. Farmers self-organized with the help of a dedicated newspaper, the Bardoli Satyagraha Patrika (Shah, 1974), staying away from farms and avoiding officials (Global Nonviolent Action Database, 2011). Taxes were eventually reduced, and confiscated land returned to farmers. The Bardoli Satyagraha was successful and was followed by the Salt Satyagraha (Dandi: Salt March, 2009) in March 1930. All these events involved solidarity within the community. Some, such as the Dandi March, were organized top-down. Others were more self-organized and emergent, with leaders playing a facilitating role.

3.2.2. Economic Disruption in the Milk Sector in the 1940s

The dairy sector in India was not organized prior to Amul’s founding in 1946. India was not self-sufficient in milk production. The growing demand for milk, attributed to a growing population and increased urbanization in the early 1940s, was met with the import of milk powder from other countries. The dairy sector comprised largely of state-run dairy farms that catered to the British military during the World Wars, some departmental milk supply schemes in the metropolises, a few private processing plants, and milk traders and middlemen (Singh & Kelley, 1981; Heredia, 1997). One of these metropolises was Bombay (approximately 450 km from Anand in Kheda district), which used to obtain more than 50% of its milk supplies from the Charotar tract of Kheda district (Brissenden, 1952). The local milk supply in Kheda came from the Patidars. Families typically owned one or two milch buffalos that were looked after by women and children. The milk provided by these buffaloes was partly consumed by the families owning them, and the rest was sold. Some of the milk sold was converted to clarified butter and sold back to wealthier Patidars.

Polson1 Modern Dairy was set up in 1930 with an initial investment of Rs. 700,000 (Desai & Narayanan, 1967). This paved the way for modernization in the sector. Soon after, in 1934, technological changes in the manufacturing process of butter led to the introduction of vacuum pasteurizers (Desai & Narayanan, 1967). The dairy had the latest machinery comparable to dairies in Europe (Kamath, 1989). Between 1929 and 1939, Polson vastly increased the production of cream, butter, and casein (Somjee, 1982). The Second World War further boosted Polson’s fortune as its production of butter reached a high of 3 million pounds a year (Desai & Narayanan, 1967). Polson’s butter was now the most famous butter brand in India. At the time, Polson was the only large private dairy in Anand (Parthasarathy, 2001; Chawla, 2007) and exerted exploitative buyer power on individual farmers (Kolkar, 2022; Singh & Kelley, 1981; Alderman et al., 1987). Speaking about the nature of milk trade in Kheda district, before Polson (a private organized dairy) came along, a long-time Director of AMUL commented:

“Before Kaira Union (AMUL) supplied to the Bombay Milk Scheme, and before Polson came into the district, farmers would make Ghee to sell to private traders and they would consume the by-product butter milk in their homes. The producers had to sell their Ghee at whatever prices were offered by the traders. However, once Polson set up the dairy business in Anand, milk was collected from individual farmers by contractors.”

However, Polson’s contractors would pay arbitrary rates (Dixit, 2014) and would sell cream separately for a commission. Polson would then supply cream and butter to Bombay. The rates paid to farmers fluctuated with seasonal production. While there was a glut of milk in winter, in summers it was scarce (Desai & Narayanan, 1967). During times of excess supply, contractors would reduce prices without consideration of farmers’ welfare (Dixit, 2014). The view was that Polson dairy was primarily motivated by its ability to source the required quantity of milk and cream for supply to Bombay. Their motivation was primarily their own profits. Regardless of the (low) price that was paid to farmers in Anand, Polson would sell milk and butter at high rates in Bombay. The view was that the profits at Polson came at the cost of farmers (Interview with former Director Amul Board). Moreover, the “fact that Polson made profits by selling its cream and butter to the British army during the war did not go down well either with the peasants of the region, or with the political activists of Kheda district, who were at the heart of the nationalist movement that Polson appeared to undermine” (Interview Former AMUL Society Manager, 14/5/2009).

Events reached a turning point in 1945 when Polson attempted further expansion of its market power. Polson lobbied to obtain an executive order from the Bombay Milk Commissioner for exclusive rights to collect milk from Anand and its surrounding 14 villages from the Bombay Milk Scheme (Heredia, 1997; Chawla, 2007; Dixit, 2014). In addition, the firm also demanded that the government of Bombay deny Kheda farmers the right to sell milk or milk products to other private traders in Kheda. A former Director of AMUL noted how Polson operated and why they might have obtained the monopoly from the British:

“Polson had milk contractors working as agents. Polson did not have any personal contacts with the milk producers. So, a contractor would collect milk from say 100 milk producers and he (contractor) would keep some 5 “Agyavan” (overseers) happy and influence them by giving them good prices so that they in turn would influence the other farmers in their village to supply milk to the contractor. They (contractors) would however give lower prices to these other producers and exploit them. So, these malpractices made them and Polson unpopular…. At that time, Polson was the most important milk purchaser…if any one person could supply milk to Bombay city in bulk, only Polson could. There was no other alternative”.(Interview)

When the Kheda farmers asked for a fair share of the extra profits of Polson by demanding a moderate raise in the purchase price of milk, Polson rejected their demands. Instead, the firm exerted buyer power by further reducing its purchase price from the farmers. These events agitated the Patidar milk producers of Kheda. As Dr. Verghese Kurien (2005) succinctly describes it in his memoir, “Polson was happy, the Milk Commissioner of Bombay was satisfied and, above all, the milk contractors (engaged by Polson) were ecstatic. The dairy farmers, on the other hand, were dejected and miserable”.

Tribhuvandas Patel was a prominent freedom fighter, political activist, and social worker who was concerned about these developments. He approached Sardar Patel and was advised to mobilize individual producers. The goal was to first go on strike (non-cooperation) and then organize into a cooperative to give them direct control over production, procurement, and processing (Dixit, 2014). The idea of a farmer-owned and controlled cooperative was a fragile experiment, based on Sardar Patel’s emancipatory vision for Kheda’s farmers, which few in those times believed would ever succeed (Ghosh, 2010). Along with Morarji Desai, Tribhuvandas Patel called a meeting of the farmers on 4 January 1946, and asked them to go on strike and to stop supplying milk to Polson and its contractors. In his memoir, Kurien (2005) notes, “This was the famous fifteen-day milk strike of Kheda district, during which all the milk that was collected by the farmers was poured on the streets, but not a drop was given to Polson. Polson’s milk collection came to a grinding halt, and the BMS collapsed.” Consequently, Bombay went without milk for 15 days, and the Bombay milk commissioner—an Englishman—and his deputy, Mr. Dara Khurody2, had to revoke the unfair executive order (Kurien, 2005; Dixit, 2014).

3.3. Explaining the Phenomenon of Emergence

3.3.1. Theoretical Approach: Giddens’ Structuration Theory

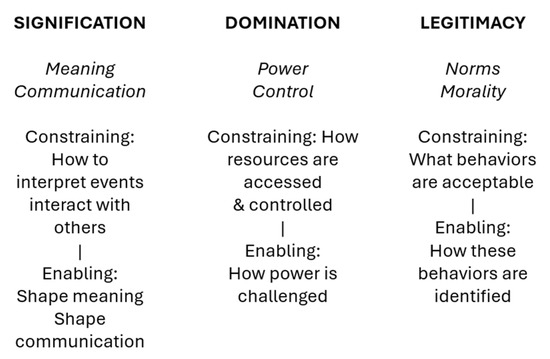

Giddens’ Structuration Theory (Giddens, 1984, 1979) addresses the mutually constitutive nature of structure and agency while emphasizing the underlying processes. At the heart of the theory is the idea of ‘duality of structure’, that social structure and individual agency are mutually constitutive of each other (Giddens, 1984; Whittington, 2015). This idea has important implications for the analysis of social systems like families, organizations, and communities. One implication is that social structure is neither objective nor deterministic. Instead of having ontological priority over human agency, structure is constituted in and through human agency (Chatterjee et al., 2019). This, according to Giddens, is the “capacity to make a difference” through the “ability to do otherwise.” This capacity, in turn, is derived from rules and resources, the two structural properties of social systems. ‘Structure is both the medium and outcome of the reproduction of practices’ (Giddens, 1979, p. 5) and “structuration [is] the process in which social structures and people’s agency interact in mutually constituting ways” (Chatterjee et al., 2019, p. 62). While individuals draw upon existing structures to act, their actions also shape and transform those structures. Both structure and agency presuppose each other, and neither has primacy. Figure 1 shows the constraining and enabling effects of structure.

Figure 1.

Forms of interaction in Structuration Theory.

Individuals, through their activities, choose to continue to participate in overlapping social systems by being whole or token members. For example, according to Whittington (2015), individuals can be members of overlapping social systems like schools, work, family, and church at the same time, choosing to allocate more or less time to these systems. Individuals also discern where to spend greater time and resources, and which rules to conform with or disregard (Giddens, 1984). Individuals are agents because they can draw on historical knowledge of what worked and what did not, and use that to justify their actions within a structural context (Chatterjee et al., 2019).

The second important implication of duality is that individuals can derive rules in one system and apply them in other systems. This happens when individuals participate pluralistically in multiple, intersecting, and interpenetrating systems (Whittington, 2015). Structuration Theory posits that human beings are not determined or conditioned by structures, given their ability to selectively and reflexively choose from a wide variety of structural rules and configurations (Giddens, 1984). Structures, therefore, offer resources for individuals to deviate from routines, creating the possibility of change even when the rules are set up for replication. The transformative capacity of human agency makes change possible (den Hond et al., 2012). Giddens’s Theory synthesizes structure and actor-based theories, positing that structures can constrain or enable human action.

Giddens’s theory elaborates three dimensions of social structures—signification, legitimization, and domination (Giddens, 1979). Signification refers to how meaning is created, communicated, and maintained. These include language and symbols of meaning. Actors make sense of their actions and communicate with others by drawing on shared meanings. These structures are not only used to produce meaning, but actors can also produce structures through their own practices. Domination refers to structures that lead to the exercise of power and the control of resources. It is not necessarily oppressive but is rather a capability that allows a coordinated response. Legitimation refers to structures that shape what behaviors are appropriate, but also to challenge these norms and identify acceptable behaviors (Mutch, 2014; Chatterjee et al., 2019).

3.3.2. Using Structuration Theory to Explain Emergence of AMUL

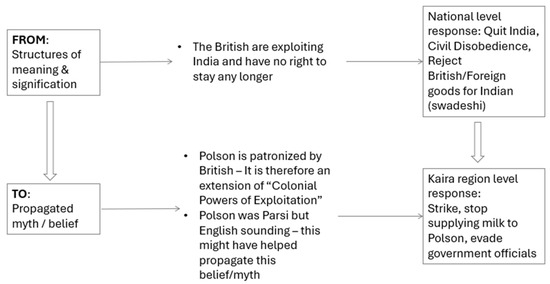

This section returns to the 14-village Milk Satyagraha. The movement was based on a refusal to cooperate with Polson and was instigated by Polson’s lack of concern for the well-being of individual producers. The flare-up could be better understood by considering the signification structure within the Patidar community. The Patidar farmers of Kheda district (at the local level) were drawing upon symbolic interpretative schemes at the national level. Their shared understanding of the benefits of a cooperative enterprise was a resource that was reinforced by the shared symbolism of British exploitation. The action of Patidar farmers to strike reproduced the structure of cooperation amongst Indians and non-cooperation against the British. This structure, in turn, provided the norms and resources for such action iteratively. Figure 2 and Figure 3 draw upon Giddens’ theory to depict pictorially the complex dynamics of the system that led to the Milk Satyagraha. It depicts how structures of meanings slowly propagate and evolve into symbolism from macro (national) levels to micro (local) levels, and also how structures of signification (meanings) evolve into structures of legitimation and normative structures.

Figure 2.

From meanings to myths/beliefs, from global to local levels.

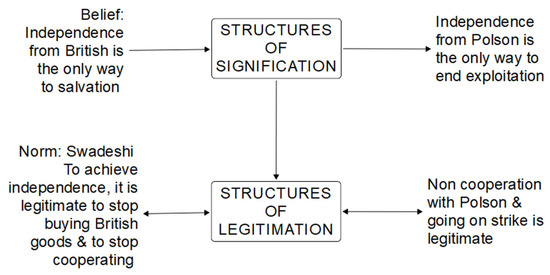

Figure 3.

Normative structures arising from structures of meaning and signification.

The rules of legitimacy of the Milk Satyagraha were drawn from the systems at the national level and facilitated by Tribhuvandas Patel, who was the link between the national and the community systems. The spirit of collective action among the farmers of Kheda and their resulting cooperative enterprise was drawn from non-cooperative movements that had been initiated against the British. Figure 2 demonstrates how the micro-level lived experiences of constituents connect to macro conditions (unjust colonial structures) that enable structures at the middle-level (organization of production). In the case of AMUL, Tribhuvandas Patel and Morarji Desai called for the dismantling of the control of Polson using the Milk Satyagraha. This framed the exploitation of Patidar producers as the result of unjust colonial rules that exploited India’s resources and perpetuated inequalities. The Milk Satyagraha was fueled by the shared interpretive schemes of the Patidars, that Polson was exploiting the Patidars by using its monopoly power secured through its lobbying of the colonial government.

Figure 2 elaborates how shared interpretive schemes of colonial exploitation were embedded in community-level grievances. Polson’s exploitation of milk producers was not seen as isolated, but as an extension of the colonial structure in the domain of milk production. When a former Director on Amul’s board was asked if the milk producers at the time felt that the British were exploiting them, the Director stated the following:

“Yes, but indirectly. Indirectly they were exploiting the farmers by way of their economic structure. The likes of Polson were controlled and patronized by the British and they used to exploit people to obtain raw materials at the lowest cost. Colonization was the basic structure. The Governor of Bombay was a Britisher”.

Figure 3 shows how structures of legitimation arise from structures of signification, It shows how belief about how things are might help generate norms about how things should be. As per Giddens’s forms of interaction (see Figure 1), this process of generation would involve individuals exercising collective agency by drawing on the modality of shared norms to sanction conduct that is seen as illegitimate. The belief that political independence was the only way (macro) legitimized the notion of indigenous enterprises and the rejection of British goods. At the micro level, collective action was enabled by drawing upon these norms of what constituted legitimate behavior on behalf of the Patidars faced with an existential crisis and their own struggle for economic independence. In effect, the Milk Satyagraha drew from the prior experience dealing with colonial injustices using the principle of non-cooperation and Satyagraha. The shared belief that independence from Polson was the only way to end exploitation was enacted by the collective in the form of non-cooperation with Polson to challenge the ongoing structure instead of reproducing it.

An agreement was finally reached between the Bombay Milk Commissioner and the farmers of Kheda that they would resume the supply of milk with their interests represented by a cooperative society. This society would collect milk from farmers and supply it to Polson until farmers acquired their own processing facilities (Dixit, 2014). This cooperative society was to become AMUL in the days to come. It was an acronym for Anand Milk Union Limited and derived from the Sanskrit word “Amulya”—meaning priceless. Of great significance is the fact that the cooperative dairy movement started as a farmers’ initiative and took root under hostile conditions against the Milk Commissioner and the Department of Dairying of the British Government of Bombay (Kurien, 2005).

Tribhuvandas Patel next facilitated the organization of individual producers into primary cooperative societies. This proved to be a slow process, as it worked against a shared belief that farmers did not stand a chance against Polson dairy. Individual producers were unsure if they could deal with such a sudden and major transformation. Tribhuvandas Patel traveled from village-to-village convincing individual producers about the spirit of unity and about the long-term advantages of cooperation and democratic principles to improve their economic condition (Heredia, 1997). Eventually, two village cooperative societies were registered in Kheda district (Kamath, 1989; Heredia, 1997; Dixit, 2014). This message was that anyone could be a member of a cooperative (Amul Dairy History, 2024)3 if they had milk to offer.

On the first day of operations, 250 L of milk was collected (Sunder, 1998; Dixit, 2014). Polson continued to enjoy a monopoly as the milk producers’ cooperative lacked a processing facility of its own. The cooperative movement, however, facilitated a growing awareness among individual farmers about exploitation by Polson, perceived as an organization patronized by the British. Polson’s continued inattention to the societal good and its pursuit of profit maximization presented a stable narrative that eventually helped the emergence of the cooperative (Singh & Kelley, 1981; Heredia, 1997).

In an interview, an AMUL veteran who worked as AMUL’s Societies Manager revealed—“Sardar enjoined the farmers of Kheda ‘Polson ne kaadhi muko’ (Get rid of Polson).” This perception of Polson being an extension of and being supported by the colonial structure was translated into a structure of legitimation Giddens (1984)—it was legitimate not to show cooperation with Polson. This gave enough fuel to the fire of nationalism and anti-British sentiment that already pervaded the farmers of Kheda, who had participated in Satyagrahas against colonial injustices in the past. They were now prepared to take on the British once more. It did not matter that Polson was not run by the British; it just had a British-sounding name.

3.3.3. Using the Panarchy Framework to Explain the Emergence of AMUL

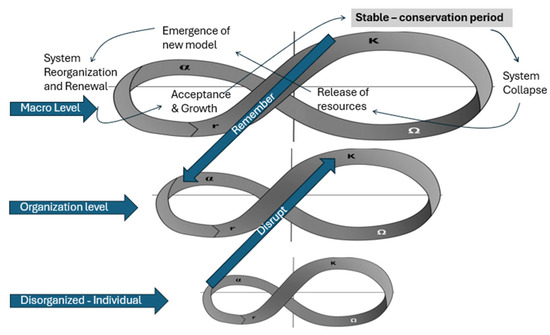

The Panarchy framework (Gunderson & Holling, 2002) depicts the growth, decline, and re-emergence of adaptive and evolutionary social, political, economic, and ecological systems. The term Panarchy represents structures that sustain experiments and allow adaptive evolution. The Panarchial representation has an advantage over other models of change, in that, while it accounts for both growth and conservation, it also accounts for the other more important but traditionally excluded phases of adaptive systems—release and reorganization (Ghosh & Westley, 2005). The framework provides a nested representation of systems at multiple levels of analysis. This allows for the possibility of dynamic reciprocal interactions across levels and between these systems in space and time, which is a distinctive feature of open, complex adaptive systems (Ghosh & Westley, 2005). The Panarchy model pictorially depicts that most social, political, economic, and ecological systems go through adaptive cycles of exploitation Γ, conservation K, release Ω, and re-organization α. It is represented as a figure ∞, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Panarchy model depicting AMUL’s remembrance of principles of cooperation and revolt. Source: (Adapted from Gunderson & Holling, 2002).

The adaptive cycles at the lower level (say, community or regional levels) represent small, but faster domains because they are the ones that innovate and experiment based on past experiences, principles, habits, or practices. The cycles at higher levels (say at provincial or state levels) represent large, but slower domains since they take a longer time to get actuated and conserve accumulated memories of past successful, surviving experiments. The representation of ‘cycles’ at multiple levels of analysis, each going through different phases of their “adaptive cycle” brings out the “nested” and “embedded” nature of socio-economic and political systems (Ghosh & Westley, 2005). It is also important to note that there could be potentially multiple connections between phases at one level and phases at another level, but two are most salient from the standpoint of our paper—connections mentioned as “Disrupt” and “Remember”. When a level in the Panarchy enters its omega phase (Ω) and experiences a collapse, that collapse can cascade to the next larger and slower level by triggering a crisis, particularly if that larger level is at the (K) phase, where resilience is low.

The dairy industry in India in the early 1940s could be conceptualized under the Panarchial view as an open complex adaptive system undergoing a series of evolutionary (learning driven) transformations (Gunderson & Holling, 2002). The system is held to be dynamic because it was being shaped by cross-scale forces over time. The organization of milk production and distribution by Polson represented the stable, conserved, K phase. At this stage, growing conditions of economic hostility at the individual disorganized farmer level triggered the Ω phase of collapse. This effect is shown across the levels by the Disrupt connection—a situation where the strike at the faster local level overwhelmed the existing organization (middle level) of production and distribution through the Bombay Milk Scheme (BMS) and Polson. The cooperation among Patidars and non-cooperation with Polson represented the moment of disruption. The movement called into question the existing rules of allocation. The Milk Satyagraha (strike) and the ensuing call for a cooperative body to represent the interests of the exploited farmers were shaped by the principles of non-cooperation, “remembered” from previous experiments conducted at the national level against the British regime. In this manner, emergent cooperation was facilitated by the macro environmental conditions that prevailed during the time.

3.4. Sustaining a Cooperative: Early Strategy Formation, Expansion, and Diversification

The environment for milk production and distribution turned favorable after India gained independence in 1947. Sardar Patel became India’s first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, and Dinkar Rao Desai, a colleague of Sardar, became the Civil Supplies Minister in Bombay in 1950. Amul now found itself in an environment that was less hostile to its growth (Singh & Kelley, 1981; Kurien, 2005). In addition, Amul’s cost of production was lower compared to Aarey Milk Colony in Bombay, started by BMS in 1949 (Kurien, 2005).

Recognizing Amul’s contribution as a source of low-cost milk to the city of Bombay, the Bombay government in 1950 gave an annual grant of Rs.300,000, which allowed Amul to extend to its members a range of services and buy a second pasteurizer (Singh & Kelley, 1981; Heredia, 1997). Artificial insemination (AI) centers were set up, and these were supplied with frozen semen. Better and more approachable roads were built to villages, wastelands were converted to common grazing grounds, mobile veterinary dispensaries were introduced, and free veterinary aid to all producers was introduced. Amul sought opportunities of symbolic value. In 1950, they invited the President of India to visit the dairy and send the first mobile veterinary dispensary on its inaugural tour. Amul was competing successfully with Polson in the collection of milk in Kheda and then again in the sale of milk to BMS (Singh & Kelley, 1981; Heredia, 1997).

To manage the increasing quantity of milk and to balance the erratic milk flows in lean and flush seasons, Amul needed to expand its facilities (Desai & Narayanan, 1967; Chawla, 2007). In 1951, the Bombay government made a proposal for financial assistance to Amul. In 1952, Amul was given exclusive rights to supply milk to BMS (Kurien, 2005), dethroning Polson. This was a direct result of the policy of the Civil Supplies Minister (Dinkar Rao Desai), who had earlier declared that his government would increase the supply of milk from rural producers in Anand. Assistance would be given to them, and cooperative effort would be encouraged in handling milk (Heredia, 1997). These factors combined to sustain Amul’s expansion.

Despite the benign environment, Kurien considered diversification of the cooperative as a key strategy to reduce dependence on BMS. Aarey Milk Colony, formed by Khurody (Milk Commissioner of BMS), was gradually being expanded to accommodate the increasing need for milk in Bombay. More and more cows from Bombay city were being relocated to the outskirts—Aarey colony (Heredia, 1997). Khurody unilaterally cut supplies of milk from Amul on the pretext that he was obliged to take milk from Aarey Colony first, as the farmers there were legally bound to sell their produce only to BMS, while those at AMUL were not. Yet, Khurody would make good the shortfall through cheap imports of skimmed milk powder (SMP), reconstitute it at Aarey, and sell it at a profit (Kurien, 2005). This further increased Aarey’s output while the sale of milk in Bombay remained more or less stable, thereby hurting Amul (Dr. Kurien Interview). He even inverted the requisition pattern of BMS, ordering more milk from Amul in the lean season and less in the flush season.

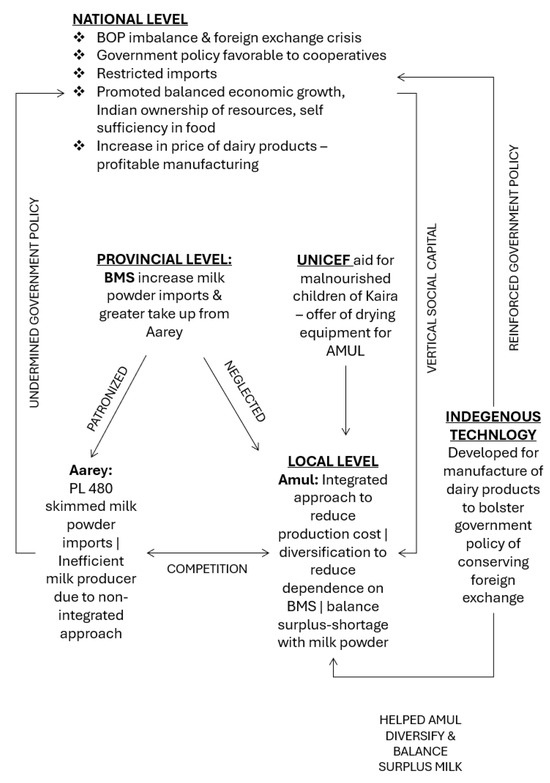

The cooperatives’ immediate survival depended on being able to balance the uneven production and distribution of milk by drying excess milk in the flush season. At this time, UNICEF approached Jivraj Mehta, the finance minister in the government of Bombay, with a proposal to distribute free milk powder to under-nourished children of Kheda through BMS and AMUL in return for Rs. 800,000 worth of milk drying machinery for the manufacture of SMP and butter (Dr. Kurien Interview). The proposal suggested a loss for AMUL. It was accepted by Kurien as a socially responsible act that also presented an opportunity to make AMUL known to the outside world. The Bombay government gave its approval, and Amul entered a direct partnership with UNICEF. A moment of triumph for Amul was when indigenous equipment was used to successfully demonstrate that it is possible to spray dry buffalo milk into milk powder—when this was considered impossible according to Western dairy experts at the time (Kurien, 2005; Heredia, 1997). With the help of its own reserves, some loans from the Govt. of Bombay, loans from the New Zealand Govt, and machinery from UNICEF, Amul’s new dairy was successfully inaugurated in 1956. Figure 5, below, shows the dynamics of Amul’s sustained production as a cooperative.

Figure 5.

Capturing the dynamics of micro and macro.

Another macro-level factor, coming as providence to assist Amul’s emergence, was the Indian government’s decision to attain self-sufficiency in agriculture and dairy goods. Having spent large sums in their 5-year plans during the late 40s and through the 50s and the pressure of importing large quantities of dairy products had worsened India’s foreign exchange and balance of payment (BOP) positions. The Indian government, partly to promote its policy of indigenous development of dairy products, and also to improve its Balance of Payments, decided to restrict imports of non-essential items, including dairy goods (Heredia, 1997). This conservative import policy was further tightened post 1956, with the result that the manufacture of dairy products was now more profitable than milk processing, both due to import restrictions and an increase in demand through increases in population (Singh & Kelley, 1981). The prices of dairy products on the restrictive imports list soared and as always with the help of Central Food and Technology Research Institute, and a few dairy experts from New Zealand and UK, Dalaya (Amul’s chief technocrat) and his team succeeded in developing innovative technologies for manufacture of butter, cheese, condensed milk, and baby food (Heredia, 1997).

Amul’s strategy was shaped by the foresight that cheese and baby food would be increasingly larger and profitable markets. This drove the first extension of the new dairy plant to manufacture cheese and baby food. When Amul requested foreign exchange through the government of Bombay, an attempt was made to divert funds to Aarey instead to help process the increasing quantities of milk. Kurien, however, argued convincingly that by undertaking the manufacturing of cheese and baby food, Amul would save the government Rs.13.5 million in foreign exchange. In contrast, Aarey would require additional foreign exchange each year for importing SMP (Kurien, 2005). Kurien’s argument showed Amul as favorable to the Government of India’s long-term policy of becoming self-sufficient and conserving foreign exchange (Heredia, 1997). Soon after, condensed milk was launched in 1958, a first in an Asian country. This was the first time in the world that buffalo milk had been used to make condensed milk (Krishna et al., 1997). Amul, therefore, filled gaps arising from restrictive imports, became a leader in import substitution, and also kept prices of butter and other products in check. AMUL was soon competing with multinationals like Nestle and Glaxo on a national level.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper explored a process of cooperative formation and sustenance in the context of economic disruption. The study used a combination of historical accounts, archival data, and primary source information to study the formation and initial sustenance of the Amul cooperative in India. Giddens’s Structuration Theory provided guidelines to understand how a collective-action oriented switch to indigenous production and distribution was legitimized. Further exploration of the narrative using the Panarchy framework presented a processual view. Here, we examined connections between changes at three levels: the macro level, the industry (organized production) level, and the disorganized individual level. We explored how the cycle of stability, collapse, experimentation, acceptance and inclusion, and growth that was occurring at the macro level also represented changes in the organization of production. The theory helped explore Amul’s emergence and its ability to disrupt the market structure of milk production and sustain operations.

The narrative of Amul demonstrates the embeddedness of economic action. We explored a mutually constitutive reciprocation between agency and structure without privileging either. Instead of advocating for the primacy of entrepreneurs as heroic atomistic agents unbridled by context, the study showed a collective emergence of economic activity. The narrative complements atomistic economic views that are based on context-free motivations. Instead of examining cooperative emergence as an efficient solution to problems like market failures or depressed prices, the study explored the local multi-level embeddedness of macro, industry, and individual producer systems. At a theoretical level, the analysis attempted to transcend the dualism between agency and structure by demonstrating how the two are mutually constitutive. At the empirical level, it examined how the emergence of the cooperative was neither the outcome of efforts of a few individuals at the micro level, nor the outcome of institutional forces driving isomorphic change at the macro level.

In addition, the narrative helps us understand how the organization of production may change in the context of economic disruption. The narrative shows the reorganization of production against an incumbent profit-making monopoly with rules of distribution that undermined the interests of individual producers. Examining such a narrative helps complement the economic argument that markets are engines for economic growth and market-based activities are important means to achieve economic empowerment. In locations in the world where institutions are yet to be developed, those at the bottom of the pyramid are less likely to be able to access and participate in economic activity by means of the structure. In such contexts, their collective actions may contribute towards creating those very structures that eventually help overcome individual-level constraints to access opportunities. The narrative of Amul shows how an existing industry organization changed through collective, emergent action.

The narrative also presents an opportunity to elaborate on a theory of change in industry structure. Economic systems are constituted by the activities of human agents, who are themselves enabled and constrained by the institutional and structural properties of these systems. These structures define both the rules (techniques, norms, or procedures) guiding action and the resources empowering action. Structural properties, however, are both the medium and the outcome of the practices that emerge, according to the notion of duality of structure. Intersections between macro systems, combined with actors’ participation in a plurality of organizations, present the opportunity for collective agency and structural change. With access to diverse systems, actors have some choice over the structural principles they enlist in their organizational activities. Processes of deliberate action can be better understood by incorporating agent-level characteristics of knowledge and reflexivity.

In contrast to the emergent process of founding, the role of leadership and institutional support is indicated in how Amul sustained operations. Amul’s leadership embedded its strategic product development initiatives in the larger economic context to foster growth. The leadership convinced policymakers that Amul’s effort was not only making the nation self-sufficient in dairy products but was also conserving the country’s valuable foreign exchange. The embedding of Amul’s ongoing product development strategy within the national imperatives allowed the cooperative to secure a favorable policy environment. In this manner, the study contributes to existing strategy process literature that has, for the most part, ignored strategic intent and limited the role of the leadership to “retroactive rationalization” of strategies post hoc (Burgelman, 1983). This study provides empirical evidence of how committed and engaged entrepreneurs can leverage scarce community resources and political power to ultimately benefit hundreds of thousands of aspirational individual producers.

Limitations and Scope for Further Research

One of the limitations of drawing lessons from historical narratives is that conclusions may emerge from a selective recollection of events or selective emphasizing of causes and effects (Fischer, 1970). The accuracy of any historical narrative depends on the validity of fine-grained information that is available from primary sources. The availability of such sources and the care taken to represent actual events can assist in valid conclusions. Actual events are often too detailed to present chronologically and understand, because of which narratives often search for connecting threads and build on them. In this process—of writing to make research more readable and acceptable—assumptions may be made about the links between events. These assumptions may be bolstered by circumstantial evidence or hearsay. We were assisted by the narrative of Amul being somewhat established with repeated publications, although these descriptions themselves fall upon a narrow variety of original descriptions. The use of multiple sources of data helped. For instance, the field visits and interviews helped establish the validity of events described in the narrative. As did our efforts to separate data points (an event) from interpretations (a statement about who perpetuated the event without specific evidence that rules out an alternative view). The narrative is written with the approach discussed in prior research (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). This support helped improve the documentation of the phenomenon, which continues to attract research interest.

Yet another limitation of this study is that Giddens’s Structuration Theory is not easy to apply empirically (Whittington, 2015; Chatterjee et al., 2019). We grappled with this in our analysis. Some of it concerned the analysis of institutional context across time and space. Some of it concerned the analysis of strategic conduct, specifically how actions are influenced by structural rules and resources. Giddens’s duality of structure enjoins us to pay equal attention to both agency as well as structure and presents an approach to accomplish this with methodological bracketing. As Whittington (2015) puts it, the methodological implication of “duality and structuration seems dauntingly holistic” (p. 149), and there is a “risk of being overwhelmed in the attempt to grasp the whole” (p. 150). To further advance understanding, future studies could use alternative theoretical approaches that are equally concerned about the relation between structure and agency. These could include the practice-theoretic approach of Pierre Bourdieu and the critical realist approach associated with Roy Bhaskar and Margaret Archer (cf. Whittington, 2015, p. 145).

Concerns for external validity arising from single case studies were traded off against the opportunity to gain rich insights (Yin, 2003; Lovas & Ghoshal, 2000; Eisenhardt, 1989). It is common in inductive, qualitative studies to study an exemplar-outlier. Studying successful exemplars is easier given that there exists scarce data on organizations that fail to emerge or fail post-emergence. For cooperative research, this is also a source of bias because the lessons for success are drawn on hindsight, post success. Cooperatives often fail (Kramper, 2012). In addition, cooperative movements often fail when attempts by individual producers to organize the system of production and create structures do not take shape. Scant data exists for failed cooperative emergent movements. This study draws on the idea of theoretically sampling positive exemplars (Patton, 2002) to obtain insights into the successful founding of a cooperative. Therefore, there is limited generalizability from it.

Within the domain of coops and social enterprises, researchers can make significant contributions by focusing on the boundary conditions of the emergence of successful and/or failed enterprises. Such work could pay specific attention to key events prior to founding. Future research could also pay specific attention to opportunity structures, which determine the external conditions that impact the likelihood of success for groups seeking change. Such studies can be replicated using multiple case analysis, using cross-case comparison for deeper insights into the boundary conditions for emergence. Additional research could look at how social enterprise exemplars (successful) strategize in the face of resource constraints. In this line of enquiry, social movement theory’s “resource mobilization” perspective may be especially useful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization A.G.; methodology A.G. and A.C.; validation A.G.; formal analysis A.G.; investigation, A.G.; resources, A.G.; data curation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, A.G. and A.C.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was made possible by a grant received from CDAS, McGill and a grant received from IDRC, Canada. This research was funded by a research stipend from Gaglardi School of Business and Economics of Thompson Rivers University and The APC was funded by [Fund# 300436].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee—REB-1 McGill University (121-1007) on [13 October 2008].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Secondary data collected for the study is available from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Edulji was affectionately known as Polly, and to bring into effect a British-sounding name, he decided to name his brand Polson (Sethu, 2021), Source: https://thebetterindia.com/250114/polson-butter-pestunji-edulji-dalal-khaira-dairy-bombay-milk-scheme-amul-butter-pre-independence-div200/ (accessed on 27 December 2024). |

| 2 | Khurody would eventually go on to become the Bombay Milk Commissioner after India’s independence. |

| 3 | https://www.amuldairy.com/t_k_patel.php (accessed on 27 December 2024). |

References

- Alderman, H., Mergos, G., & Slade, R. (1987). The history of AMUL, the dairy cooperative movement, and operation flood: A literature review. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7645795f-b1c8-4ae7-9b14-2a702565856c/content (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Amul Dairy History. (2024, December 27). Milk, The inspiration behind a revolution. Available online: https://www.amuldairy.com/history.php (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Argyres, N. S., De Massis, A., Foss, N. J., Frattini, F., Jones, G., & Silverman, B. S. (2020). History-informed strategy research: The promise of history and historical research methods in advancing strategy scholarship. Strategic Management Journal, 41, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C. (1981). The nature of social change in rural Gujarat: The Kheda district, 1818–1918. Modern Asian Studies, 15(4), 771–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J. A. C., & Dutton, J. E. (Eds.). (1996). The embeddedness of strategy. In Advances in strategic management (Vol. 13). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bettis, R. A. (1991). Strategic management and the straightjacket: An editorial essay. Organization Science, 2(3), 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C., & Özcan, S. (2014). Why do cooperatives emerge in a world dominated by corporations? The diffusion of cooperatives in the US bio-ethanol industry, 1978–2013. Academy of Management Journal, 57(4), 990–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L. (1984). The development of the India Famine Codes: Personalities, policies and politics. In B. Currey, & G. Hugo (Eds.), Famine as a geographical phenomenon [GeoJournal library, vol. 1 (Illustrated ed.)] (pp. 91–110). Springer. ISBN 90-277-1762-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brissenden, C. H. (1952). The bombay milk scheme. International Journal of Dairy Technology, 5(2), 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. D., & Thompson, E. R. (2013). A narrative approach to strategy-as-practice. Business History, 55(7), 1143–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. H. (1985). Democracy in organizations—Membership participation and organizational characteristics in United-States retail food co-operatives. Organization Studies, 6(4), 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H.-L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, R. A. (1983). A process model of internal corporate venturing in the diversified major firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(2), 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G. R., Goodstein, J., & Gyenes, A. (1988). Organizations and the state—Effects of the institutional environment on agricultural cooperatives in Hungary. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(2), 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, I., Kunwar, J., & den Hond, F. (2019). Anthony giddens and structuration theory. In Management, organizations and contemporary social theory (pp. 60–79). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, H. (2007). Amul India: A social development enterprise. Asian Case Research Journal, 11(2), 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M. L. (1995). The future of U.S. agricultural cooperatives: A neo-institutional approach. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 77(5), 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M. T., Ventresca, M. J., & Beal, B. D. (1999). The embeddedness of organizations: Dialogue & directions. Journal of Management, 25, 317–356. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R. L., & Lewin, A. Y. (1990). Can organization studies begin to break out of the normal science straitjacket? An editorial essay. Organization Science, 1(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandi: Salt March. (2009, October 11). Available online: http://southasia.ucla.edu/history-politics/gandhi/dandi-march/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- den Hond, F., Boersma, F. K., Heres, L., Kroes, E. H., & van Oirschot, E. (2012). Giddens à la Carte? Appraising empirical applications of Structuration Theory in management and organization studies. Journal of Political Power, 5(2), 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, J. L., Langley, A., & Rouleau, L. (2007). Strategizing in pluralistic contexts: Rethinking theoretical frames. Human Relations, 60(1), 179–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D. K., & Narayanan, A. V. S. (1967). Impact of modernization of dairy industry on the economy of Kaira district. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 22(3), 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Zukin, S. (1990). Structures of capital: The social organization of economic life. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, M. R. (2014). Amul–2014 (pp. 1–60). Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Stephan, U. (2013). Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions: Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(3), 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. (1967). Mixed-scanning: A “third” approach to decision-making. Public Administration Review, 27(5), 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, C., & Langley, A. (2011). Strategy as practice and the narrative turn. Organization Studies, 32(9), 1171–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D. (1970). Historians’ fallacies: Toward a logic of historical thought. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, P., & Whetten, D. A. (2002). Members’ identification with multiple-identity organizations. Organization Science, 13(6), 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. (2010). Embeddedness and the dynamics of strategy processes: The case of AMUL Cooperative, India. McGill University Library. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A., & Westley, F. (2005, August 5–10). AMUL—India’s cooperative success story. Paper presented at the Academy of Management, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies of qualitative research. Wiedenfeld and Nicholson. [Google Scholar]

- Global Nonviolent Action Database. (2011). Bardoli peasants campaign against the Government of bombay, 1928. Available online: https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/bardoli-peasants-campaign-against-government-bombay-1928 (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H., & Rao, H. (2012). Echoes of the past: Organizational foundings as sources of an institutional legacy of mutualism. American Journal of Sociology, 118(3), 635–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L. H., & Holling, C. S. (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardiman, D. (1981). Peasant nationalists of Gujarat: Kheda district, 1917–1934. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia, R. (1997). The amul India story. Tata McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig, R., Barron, G., Weber, E. U., & Erev, I. (2004). Decisions from experience and the effect of rare events in risky choice. Psychological Science, 15(8), 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hote, P. (2021). Tracing the intellectual evolution of social entrepreneurship research: Past advances, current trends, and future directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 182, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, P., & Simons, T. (2000). State formation, ideological competition, and the ecology of Israeli workers’ cooperatives, 1920–1992. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(1), 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Cooperative Alliance [ICA]. (2009). What is a co-operative? Available online: https://ica.coop/en/cooperatives/what-is-a-cooperative (accessed on 15 July 2009).

- Jarzabkowski, P. (2005). Strategy as practice: An activity-based approach. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A. G., & Whyte, W. F. (1977). The mondragon system of worker production cooperatives. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 31(1), 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G., Langley, A., Melin, L., & Whittington, R. (2007). Strategy as practice: Research directions and resources. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. L. (Ed.). (2006). Gandhi’s experiments with truth: Essential writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, M. V. (1989). Management kurien-style: The story of the white revolution. SIDALC. [Google Scholar]

- Kolkar, T. B. (2022). Dairy farming and rural development. Journal of Research & Development, 13(15), 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kramper, P. (2012). Why cooperatives fail: Case studies from Europe, Japan, and the United States, 1950–2010. The Cooperative Business Movement, 1950 to the Present, 14(4), 126. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A., Uphoff, N., & Esman, M. (1997). Reasons for hope. Kumarian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kurien, V. (2005). I too had a dream. Roli Books Private Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M., & Ventresca, M. (2003). The new structuralism in organizational theory. Organization, 10(3), 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovas, B., & Ghoshal, S. (2000). Strategy as guided evolution. Strategic Management Journal, 21(9), 875–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani Bhavan. (n.d.). Mahatma gandhi museum and reference library. Detailed Chronology of Mahatma Gandhi. Available online: https://www.gandhi-manibhavan.org/about-gandhi/detailed-chronology.html (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Meyer, A. D. (1982). Adapting to environmental jolts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, J. (1994). The rationales of cooperative organizations: Some suggestions from Scandinavia. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 65(1), 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. (1978). Patterns in strategy formation. Management Science, 24(9), 934–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. (1979). An emerging strategy of “direct” research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1982). Tracking strategy in an entrepreneurial firm. Academy of Management Journal, 25(3), 465–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, A. (2014). Anthony Giddens and structuration theory. In P. S. Adler, P. du Gay, G. Morgan, & M. Reed (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of sociology, social theory, and organization studies: Contemporary currents (pp. 587–604). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, S. (2001). National policies supporting smallholder dairy production and marketing: India case study. In Proceedings of a South-South workshop. National Dairy Development Board. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1985). The awakening giant: Continuity and change in imperial chemical industries. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1992). The character and significance of strategy process research. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S2), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, D. F. (1972). Kanbi and Patidar: A study of the Patidar community of Gujarat. Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (2023). The iron cage redux: Looking back and forward. Organization Theory, 4(4), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnér, P. (2008). Strategy as practice and dynamic capabilities: Steps towards a dynamic view of strategy. Human Relations, 61(4), 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, P. S., & Perry, J. L. (1985). Strategic management in public and private organizations: Implications of distinctive contexts and constraints. Academy of Management Review, 10(2), 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiberg, M., King, M., & Smith, T. (2008). Social movements and organizational form: Cooperative alternatives to corporations in the American insurance, dairy and grain industries. American Sociological Review, 73(4), 635–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, G. (1974). Traditional society and political mobilization: The experience of Bardoli satyagraha (1920–1928). Contributions to Indian Sociology, 8, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, K. A., Little, T. D., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2017). Human agentic theories and the development of self-determination. Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course, 2017, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, T., & Ingram, P. (1997). Organization and ideology: Kibbutzim and hired labor, 1951–1965. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 784–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. P., & Kelley, P. L. (1981). Amul: An experiment in rural economic development. MacMillan India Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G., & May, D. (1980). The artificial debate between rationalist and incrementalist models of decision making. Policy and Politics, 8(2), 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somjee, A. H. (1982). The techno-managerial and politico-managerial classes in a milk cooperative. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 17(1/2), 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, R. (2000). The co-operative advantage. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 71(4), 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staber, U. (1989). Organizational foundings in the cooperative sector of atlantic Canada—An ecological perspective. Organization Studies, 10(3), 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U., Uhlaner, L., & Stride, C. (2015). Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunder, S. R. (1998). Amul and India’s national dairy development board (HBS Case Study 9-599-060). HBS Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, J. (1992). The Social Structure of Patidar Caste in India. Kanishka Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukas, H. (2009). Practice, strategy making and intentionality: A Heideggerian onto-epistemology for strategy-as-practice. In D. Golsorkhi, L. Rouleau, D. Seidl, & E. Vaara (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of strategy as practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven, A. H. (1992). Suggestions for studying strategy process: A research note. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K., Heinze, K. L., & DeSoucey, M. (2008). Forage for thought: Mobilizing codes in the movement for grass-fed meat and dairy products. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(3), 529–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R. (2007). Strategy practice and strategy process: Family differences under the sociological eye. Organization Studies, 28(10), 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R. (2010). Giddens, structuration theory and strategy as practice. Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, 2010, 109–126. [Google Scholar]