Abstract

This paper examines the intersection between entrepreneurship government policy and managerial theory. The context chosen for this study is India. India has experienced a significant global geopolitical shift that is coinciding with India’s domestic policy reforms and notable domestic initiatives. Since 2014, India’s entrepreneurial ecosystem has seen a significant increase in the number of startups and unicorns. This paper presents arguments that the confluence of global realignments, such as the diversification of supply chains away from China and increasing interest in the Indo-Pacific region, along with domestic initiatives like “Make in India”, “Startup India”, and digitalization drives, along with massive investments in infrastructure improvements, have made India a desirable destination for entrepreneurial activity. By examining these factors through the lens of three theories—resource-based view, global value chain, and innovation ecosystem theory—this paper identifies key opportunities and challenges for entrepreneurs across various sectors. It is hoped that this research will contribute to a deeper understanding of India’s evolving entrepreneurial landscape. In addition, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and investors can benefit from this article to understand the opportunities and challenges India poses in order to contribute to India’s continued economic growth and its emergence as a global entrepreneurial powerhouse. Finally, this paper helps to bridge the gap between economic policy and management theory.

1. Introduction

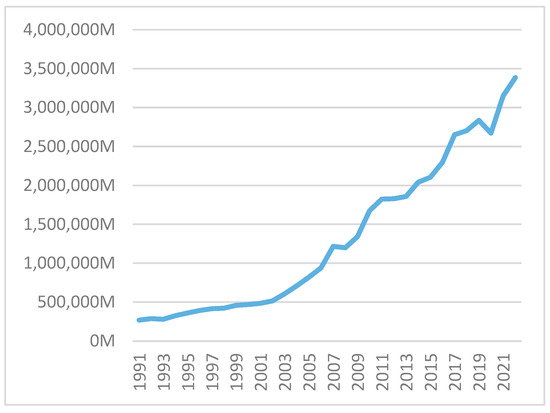

This paper highlights a successful, focused use of government policy to create an entrepreneurship ecosystem. Since the economic liberalization that started in 1991, Indian GDP has jumped from the 17th ranked to the 5th ranked economy in the world, with GDP increasing from USD 270 B in 1991 to about USD 3.5 trillion in 2023 (Figure 1). This growth exceeds the growth explained by population increases in India. Despite this large growth in GDP, India lags behind other major economies in terms of per capita GDP, which was just USD 2480.80 in 2024, or about USD 8103 when adjusted for purchasing power parity. Yet, India is expected to become a major growth engine for the world in the 21st century. The factors that favor India’s growth are its (1) vast and youthful population, (2) burgeoning middle class, and (3) rapidly developing infrastructure, including digital infrastructure. China, with a focus on the industrial sector, underwent a similar but more explosive growth with the same favorable factors (Bosworth & Collins, 2008). Hence, India has attracted significant attention from investors and entrepreneurs from all over the world. Another set of factors that are fueling this surge in interest are (a) dramatic geopolitical shifts on the international stage and (b) India’s domestic policy reforms during the last ten years or so.

Figure 1.

India’s GDP (current US dollars). Data from Worldbank.org.

The world has been experiencing a recalibration of geopolitical dynamics over the last 60 years. After the Second World War, the economy of Japan, with their intense focus on quality improvement, catapulted to the second largest economy in the world. Then came the rise of China, which is currently the world’s second largest economy in terms of GDP and is positioned to rise to number one in about 10 years from now (Morrison, 2019). However, the global pandemic and rising trade tensions have brought to the fore the risks of vulnerability caused by concentrated supply chains. As a result, multinational corporations are attempting to diversify and move away from their reliance on a single source to eliminate these vulnerabilities (McKinsey Global Institute, 2023). India, given its democratic institutions and large, young workforce, could benefit from this shift. Moreover, given the strategic importance of the Indo-pacific region, as well as India’s role in the geopolitics of the region, India is attracting engagement and investments from key global partners (Pant, 2022).

The current government understands that if India is to play a larger role in the world, it must ameliorate the condition of a large, impoverished population in the country. Toward this end, the Indian government announced a series of policy reforms, as well as new initiatives to foster economic growth. Among these initiatives are “Make in India”, “Digital India”, and “Startup India”. These have created an environment to promote entrepreneurial activities (Kumar, 2018). These and other initiatives and policy reforms are simplifying bureaucratic regulations, creating support structures for startup and small/medium enterprises (SMEs), and promoting innovation. Additionally, as stated by Srinivas (2021), the government is expanding efforts to digitize India. This has taken the form of (a) India’s highly successful unified payment interface (UPI), which has made India a world leader in instant payments with no cost to the payer or payee, (b) the expansion of internet connectivity, and (c) digital government. These efforts have made it possible for entrepreneurs to explore new markets and opportunities (Srinivas, 2021).

Given these geopolitical developments and the domestic efforts of the present government, India is now uniquely placed to serve as fertile ground for opportunities for local and international entrepreneurs. This paper attempts to explore these opportunities in light of innovation ecosystems, global value chains, and a resource-based view: three major theoretical frameworks of strategic management. The authors assert that the present government’s emphasis on the ease of doing business and the promotion of innovation has led to a more supportive institutional environment for local and international entrepreneurs in India. The authors explore how the confluence of three occurrences—geopolitical shifts, domestic policy reforms, and the enhanced availability of firm-level resources—is shaping the entrepreneurial landscape in India. The timeline for the paper is from the 2010s to 2024. This extended timeframe allows for policies to be enacted and have their impact—positive or negative—recognized. The analysis in this paper helps explain the factors promoting entrepreneurial success in India, which in turn can be valuable not just to entrepreneurs, but also to policymakers as well as investors.

2. The Confluence of Global Political Trends

Currently, the world is experiencing transformative geopolitical dynamics. There is a rebalancing or shifting of power taking place between emerging and established economic alliances and nations, which is creating challenges as well as opportunities for nations worldwide. This article examines how the political changes in countries such as USA, Russia, and China are giving rise to entrepreneurial opportunities in India. This article illustrates how entrepreneurs, by being strategic, can take advantage of these evolving power shifts.

2.1. Current Global Trends

2.1.1. The US–China Dynamic and Supply Chain Diversification

The US president Donald Trump started his 2017–2021 “term by launching a trade war with China” to fulfill his campaign promise (Allen-Ebrahaminian, 2021). During President Trump’s second term that started in January 2025, trade tensions with China continues. Additionally, trade disputes expanded to include Canada and Mexico, and there are indications of possible future trade actions involving other nations. Incidentally, it must be pointed out that President Biden (2021 to 2025) not only continued but expanded the tariff on China from the first term of President Trump. To make the matter worse, during the first term of President Trump, the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic was traced to Wuhan, China. Nevertheless, the pandemic exposed the global supply chain’s vulnerability, given the overreliance on one single source—China. Given that the United States and China were already engaged in an escalating tug of war with respect to strategic competition, multinational corporations (MNCs) and governments unified to diversify and reduce single-source dependency (McKinsey Global Institute, 2023). Given its large and young population, strong democratic institutions, and growing manufacturing capabilities, India is well suited to be one of the main beneficiaries of the supply chain diversification strategy. Many MNCs embraced the “China Plus One” strategy and started developing second manufacturing sites in countries like India to mitigate risks and build resilience (Fernandes & Sharma, 2021). This trend creates opportunity for entrepreneurs in India.

2.1.2. The Russia–Ukraine Conflict and Energy Security

The prolonged conflict between Russia and Ukraine has sent shockwaves through the global energy market. It is obvious that energy security and diversification are needed for every country, including India. India’s long-standing reliance on energy imports requires continued strategic efforts to meet its energy needs. It must be noted that India continued to buy “cheap” oil from Russia while the US and the west boycotted it during the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Nevertheless, the Russia–Ukraine war has created an opening for entrepreneurs in the renewable energy sector. As Bhattacharya (2022) indicates, India has declared very ambitious renewable energy adoption targets. Current geopolitics further incentivizes investments in solar, wind, and other renewal/clear energy sources. Thus, there are opportunities for entrepreneurs to exploit this trend by developing new technologies and innovative solutions for the production, storage, and distribution of renewable/clean energy.

2.1.3. China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Regional Connectivity

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), alternatively known as the New Silk Road initiative, was launched in 2013 to initially “link East Asia and Europe through physical infrastructure”, but it has now expanded to include Africa, Oceania, and Latin America (McBride et al., 2023). McBride et al. (2023) point out that the USA and some Asian countries see this as a Trojan horse for military expansion and strategic influence. Perhaps this has created an impetus for India to further strengthen its own regional partnerships. In this respect, Indian entrepreneurs can utilize their understanding of cultural and market nuances of neighboring countries and develop economic ventures ranging from infrastructure development to cross-border trade and technology transfer (Pant, 2022).

These factors combine to increase competition globally for resources and markets. India’s policies, with respect to its regional partnerships, are not new, but their interaction with global power dynamics would create economic ecosystems, which, in turn, would create opportunities for global as well as Indian entrepreneurs.

3. India’s Economic Domestic Policies and Potential

3.1. India’s Domestic Policy Landscape

Beyond the external geopolitical shifts that were addressed in the above paragraphs, the domestic policy changes under the current government have played a crucial role in fostering entrepreneurial culture as well as opportunities. India’s entrepreneurial landscape is undergoing a significant evolution, fueled by a spate of ambitious, yet commonsense, domestic policy reforms under the current political leadership. More specifically, initiatives such as “Make in India”, “Startup India”, and “Digital India” have created a more supportive environment for business and innovation (Kumar, 2018). These new policies and initiatives have focused on rationalizing regulations, boosting investment, and supporting startups and small businesses to flourish. The evolving geopolitical landscape presents a complex array of challenges and opportunities for India. If India can navigate these shifts strategically and exploit its domestic strengths, it can position itself as a major destination hub for entrepreneurial activity. Through wise policy decisions, India is positioning itself to adapt and capitalize on these global changes. Entrepreneurs, in turn, can capitalize on these emerging opportunities by developing innovative solutions that cater to the changing needs of the global economy. This article examines how these policy changes and initiatives are creating a vigorous ecosystem for entrepreneurial activity, fostering innovation, and, more importantly, attracting investment across various sectors. The following paragraphs discuss some of these key policies and initiatives further.

3.1.1. Make in India: Boosting Manufacturing and Exports

Launched in 2014, the “Make in India” campaign under the present government is deemed as the largest initiative ever to attract foreign direct investment to start manufacturing in India (Mehta & Rajan, 2017). The campaign aims to transform India into a global manufacturing destination. Kumar (2018) contends that this policy has created numerous opportunities for entrepreneurs in sectors such as electronics, automobiles, textiles, and pharmaceuticals due to the initiative’s focus on key enablers such as the promotion of domestic manufacturing, encouragement of foreign direct investment (FDI), and acceleration of technology transfer. It must be stated that India has not banned the import of manufactured goods, such as iPhones; rather, it is actively incentivizing manufacturing within India to boost its industrial base. In addition, the focus on the ease of doing business, infrastructure development, and skill enhancement has strengthened the manufacturing ecosystem, enabling entrepreneurs to compete globally.

3.1.2. Startup India: Fostering Innovation and Entrepreneurship

According to a press release by the Government of India (2016), the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting launched several new initiatives in 2016. The “Startup India” initiative was launched on 16 January 2016, with the goal of promoting a thriving startup ecosystem in India across all demographics in India. A similar initiative called “Standup India” was launched on 5 April 2016. The key distinction between the two initiatives was that the second one was geared toward women, disadvantaged classes, and tribal sections of society. These initiatives provided financial assistance, mentorship, and regulatory support, with the hope of encouraging a new generation of entrepreneurs to pursue innovative ideas and build growing businesses. Further, the Government of India has supported the establishment of incubators, accelerators, and funding mechanisms, which, in turn, has further facilitated the growth of startups across diverse sectors of economy, including technology, healthcare, and education (Dutta, 2019).

3.1.3. Digital India: Expanding Digital Infrastructure and Access

According to MyGov India (n.d.), the “Digital India” program was launched on 1 July 2015. The aim of the program was to use technology to enable “access to better service for education, healthcare, and agriculture”. In almost a decade since its launch, it has “laid the foundations for a strong, robust and secure Digital India”. The initiative’s aim is to close the digital divide and transform India into a digitally empowered society. Even though internet use and mobile penetration in India is low by the developed world’s standard, India is expanding internet connectivity, promoting digital literacy, and encouraging the adoption of digital technologies. Especially praiseworthy is India’s unified payment interface (UPI), which has resulted in a cash-to-digital payment transformation (Denny, 2024). The Digital India initiative has unlocked new markets and opportunities for entrepreneurs in the digital economy. According to Srinivas (2021), the growth of the e-commerce, fintech, and digital health sectors symbolizes the transformative impact of “Digital India” on the entrepreneurial landscape.

3.1.4. Infrastructure Development: Connecting Markets and Enhancing Efficiency

According to KPMG (2024), in the last ten years, India has experienced tremendous expansion in its infrastructure, including roads, railways, metro rail networks, ports, and airports. This expansion has significantly improved connectivity and logistics across the country, which has not only facilitated the movement of goods and services but also created new opportunities for entrepreneurs in sectors such as transportation, logistics, and construction. Many of these infrastructure projects rely on public–private partnerships (PPPs) for funding. India is also committed to developing dedicated freight corridors and industrial corridors, which would potentially further enhance the efficiency of supply chains, enabling businesses to operate more effectively (Goyal, 2020).

3.1.5. Policy Reforms: Simplifying Regulations and Promoting Investment

Beyond the highly visible and promoted initiatives described above, the government has implemented numerous policy reforms to simplify regulations with the goal of reducing bureaucratic hurdles for promoting investments. Some of the reforms are also aimed at reducing the parallel (or black) economy that exists for large-scale tax evasion. These reforms have included measures such as the Goods and Services Tax (GST), insolvency and bankruptcy codes, and the liberalization of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) norms. According to The World Bank (2023), these initiatives have created a more predictable and transparent business environment, encouraging both domestic and foreign investors to participate in India’s growth story.

The convergence of these initiatives and domestic policy reforms has created a playing field that is very favorable for entrepreneurs that are looking to capitalize on the opportunities present in India. A new generation of empowered entrepreneurs are eager to pursue their dreams and contribute to India’s economic growth, given that the government is promoting innovation and investment, as well as improving the ease of doing business. As India continues to navigate the complexities of the global landscape, its domestic policy reforms will transform its entrepreneurial future.

3.2. Indian Entrepreneurial Potential

India, without a doubt, is experiencing an entrepreneurial awakening. This section of the article attempts to (a) explore the historical context of Indian entrepreneurship, (b) analyze the current emerging trends, and (c) examine the immense potential of this mushrooming ecosystem. It is fascinating to examine the intersection of cultural, economic, and policy factors, with the hope to understand the unique characteristics and future trajectory of Indian entrepreneurship.

3.2.1. Historical Context: From Tradition to Innovation

According to The Financial Express (2023), entrepreneurship in India has deep historical roots, with a rich tradition of merchant communities and family businesses, dating as far back as 3300 BCE to the Indus Valley Civilization. Later, about 3000 years ago, “Indian traders engaged in re-exporting silk from China to Central Asia and trading horses from West Asia to China”. Traders and artisans created a burgeoning economy through the years, making India, along with China, the largest economy up until the start of the 18th century (Aiyar, 2023). However, the colonial period saw a decline in indigenous industries and the emergence of a risk-averse culture (Goswami, 2010). After gaining independence in 1947, India adopted a socialist model with a focus on state-led development. While this approach achieved some success in building core industries, it also stifled private enterprises and innovation, with rampant governmental corruption abound. Up until the economic liberalization of 1991, India was known as the License Raj, referring to India’s strict governmental regulation over the economy—businesses required permits and licenses. The economic liberalization of 1991 started creating new opportunities for entrepreneurs (Panagariya, 2008).

3.2.2. Emerging Trends: A Dynamic Ecosystem

In recent years, India’s entrepreneurial landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation. Several factors have contributed to this shift, as listed below:

- Demographic Dividend: India has a young and growing population, with both skilled and unskilled labor. India is in a prime position to enjoy this demographic dividend if India can increase the participation of women in the labor force (Marois et al., 2022). This demographic dividend provides a significant advantage for entrepreneurs, offering a vast consumer market and a talented workforce (Bloom et al., 2010).

- Technological Advancements: India is seeing a rapid deployment of technology, particularly in the IT and telecommunications sectors. This has fueled innovation and created new opportunities for entrepreneurs. As Srinivas (2021) points out, the rise of the internet and mobile technology has led to the emergence of a vibrant digital economy in India.

- Policy Reforms: The government’s proactive policies, such as “Make in India”, “Startup India”, and “Digital India”, have awakened the innate entrepreneurial urges of young Indians. These initiatives have focused on simplifying regulations, promoting investment, and fostering innovation, thus creating a fertile ground for entrepreneurial activity (Kumar, 2018).

- Growing Investment: India is attracting significant investment from both domestic and foreign sources. Surging venture capital and private equity investments provide crucial funding for startups and growth-stage companies (KPMG, 2023).

- Global Recognition: There are several Indian entrepreneurs who are gaining recognition on the global stage, as they have successfully expanded their businesses globally. As stated by Bala Subrahmanya (2022), even though only a very small percentage of startups have achieved the distinction of unicorn status, Indian startups have demonstrated the potential for innovation and scalability in the Indian ecosystem (CB Insights, 2023).

3.3. Unleashing Potential: Challenges and Opportunities

Despite the significant progress made in recent years, Indian entrepreneurship still faces several challenges:

- Infrastructure Bottlenecks: India has made significant improvements to its national infrastructure, as stated earlier in this paper. However, there is still a long way to go. Inadequate infrastructure, particularly in transportation and logistics within towns or city centers, can hinder business operations and increase costs.

- Bureaucratic Hurdles: Even though the present government has been making strides toward regulatory reforms, India is still a country with complex regulations and bureaucratic processes. Greasing the palm is still a way of life in government offices. These processes can create roadblocks for entrepreneurs, particularly for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

- Skill Gaps: While India has a large workforce, skill gaps persist in many sectors, including healthcare, construction, IT, semiconductor manufacturing, and banking, financial services, and insurance (BFSI). This can impact entrepreneurs.

- Access to Finance: Despite many successful governmental initiatives to increase access to finance for entrepreneurs, access to finance remains a challenge for many entrepreneurs, particularly those in the early stages of their ventures. The challenge is even more serious for women entrepreneurs than men.

- Excessively Competitive, Price-Sensitive Environment: India is a country with a price-conscious, cut-throat competitive marketplace. As a result, the failure rate of startups is relatively high.

3.4. The Way Forward: A Collaborative Approach

It would be impossible to harness the power of Indian entrepreneurship in isolation; this requires an approach in which the government and the private sector work in conjunction with academia to achieve the following:

- Strengthening Infrastructure: Investing in the creation of more transportation, logistics, and energy systems to achieve greater business efficiency and competitiveness.

- Simplifying Regulations: Simplifying regulations and reducing bureaucratic hurdles to avoid overburdening entrepreneurs, which will enhance the ease of doing business.

- Enhancing Skills: The promotion of education and skills development will prepare the workforce with a proper aptitude relevant to the needs of the ever-changing economy.

- Access to Finance: Venture capital, angel investors, and government schemes can provide access to finance for entrepreneurs.

- Fostering Innovation: Innovation can be fostered by promoting research and development culture, incubation centers, and mentorship programs that will drive the creation of new ideas and technologies.

These steps will liberate the entrepreneurial spirit in India and enable it to compete at the very top level of innovation and economic growth in the world. The following provides an overview of three theories that explain SME growth in India and their relationship to economic policies. These are the resource-based view of a firm, the global value chain, and innovation ecosystem theory, each of which have implications both for the country of India and its economic policy and the entrepreneurs themselves. The following section of this article describes the authors’ propositions based on these three theoretical frameworks and their links to government policies.

4. SME Growth in India: Propositions and Explanations

The focus of this section is to provide a synthesis of management theory and government policy in a way that demonstrates their interaction and impact. Each review of a theory and its linkage to Indian economic policies, followed by the propositions, provides opportunities for future empirical research.

4.1. Resource-Based View

The resource-based view (RBV) is a theoretical framework that emphasizes a firm’s or country’s internal resources and capabilities as key drivers of sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). The RBV argues that unique resources—tangible assets, intangible assets, and organizational capabilities—that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable create a basis for growth and competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984).

The RBV of a firm has implications for both firms and governments. Governments can promote local economic growth through policies that include direct support for multinational enterprises, as well as the provision of tax and trade incentives. Governments can increase foreign direct investment either through partnerships or firms entering the market (Guillen, 2000; Deng et al., 2020). These policies become the grounds for unique resources and competitive advantage.

The RBV holds that firm-specific resources that are hard to copy are the main determinants of an MNC’s sustainable bargaining position over time (Moon & Lado, 2000). Positive-sum benefits can also be created through the development of co-specialized assets by both the MNC and the host government. For instance, an MNC can contribute a particular type of technology to a host country, and the host government can develop complementary industries (e.g., components) built around the technology (Liu & Li, 2022).

Through government policies, business partnerships can create strong industry linkages that promote innovation activities and business performance. By signing free trade agreements and through the formation of tax-free investment zones, governments can provide a foundation for businesses to improve their innovation capacity to meet product quality standards and pursue quality management systems (Cooke, 2001). Truong et al. (2024) show that these agreements also play an important role in creating the conditions for exporting goods to other countries. Manufacturers must innovate to be able to export goods and improve business performance through expansion to international markets. Free trade agreements also create value supply chains from inputs to outputs. The government also assists by funding and encouraging new training disciplines to meet labor demand. In summary, the government has a crucial role in promoting innovative pursuits, facilitating rapid international business integration, and improving the global competitiveness of firms (Truong et al., 2024).

4.1.1. RBV and the Indian Entrepreneurial Context

A valuable paradigm for understanding the factors driving entrepreneurial success in India is the resource-based view (RBV). The RBV proposes that firms achieve a competitive advantage by leveraging valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources (Barney, 1991). In the Indian context, this paradigm helps explain how entrepreneurs have historically leveraged unique resources and how these resources are evolving in the current global and domestic political environment.

Historically, Indian entrepreneurs have relied on several key resources to achieve success:

- Traditional Knowledge and Skills: India has a history of craftsmanship, artisanal skills, and traditional knowledge passed down through generations. Additionally, India boasts a higher-education system that graduates a technically proficient workforce. The creation of unique products and services, particularly in sectors like textiles, handicrafts, and agriculture, has been leveraged by entrepreneurs (Goswami, 2010).

- Family Associations and Social Capital: Strong family associations and community ties provide Indian entrepreneurs with access to capital, mentorship, and market knowledge. These social resources have been crucial for navigating complex business environments and overcoming resource constraints (Khanna & Palepu, 1997).

- Frugality and Jugaad: Indian entrepreneurs have demonstrated innovative capacity within resource constraints. This “jugaad” mindset, characterized by frugality, adaptability, and improvisation, has enabled the creation of cost-effective solutions and the ability to compete effectively in resource-constrained environments (Radjou et al., 2012).

4.1.2. RVB and Research Propositions:

Indian entrepreneurs can capitalize on the opportunities presented by the current global and domestic political environment by addressing challenges and effectively utilizing their evolving resources. Indian entrepreneurs can contribute to India’s economic growth and global competitiveness by strategically managing resources and adapting to the changing environment.

- Proposition 1: Digital Resource Leverage and Global Competitiveness.

- Proposition 1: Indian entrepreneurs that effectively leverage digital resources, such as cloud computing, data analytics, and artificial intelligence, will exhibit greater success in achieving international market access.

- Rationale: The RBV holds that technologies such as cloud computing, data analytics, and artificial intelligence provide competitive advantages through scalable infrastructure and data insights. These digital resources also allow entrepreneurs to reach global markets more easily and efficiently.

- Theoretical grounding digital resources can enhance agility, adaptability, and innovation, enabling entrepreneurs to respond to dynamic political shifts and access new markets globally (Chatterjee & Kar, 2020; Kohli & Bhagwati, 2012). These positive outcomes are in fact noted in India (Sony & Aithal, 2020).

- Proposition 2: Human Capital Development.

- Proposition 2: Indian entrepreneurs who prioritize human capital development through investments in employee training, skills enhancement, and knowledge acquisition will be better positioned to capture and maintain market share within the evolving global landscape.

- Rationale: A well-trained workforce can generate creative solutions and drive innovation, as well as develop new skills which allow them to meet global challenges. These innovative solutions can create improved outcomes and cost savings for organizations. Investing in employee development increases employee loyalty and commitment to organizations, which translates to higher retention, which in turn reduces employee recruitment costs.

- Theoretical Grounding: A skilled and adaptable workforce is essential in navigating policy changes, meeting evolving consumer demands, and achieving sustained success in dynamic markets (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2010; Kapoor & Vaidya, 2013; Kaur & Kumar, 2024).

- Proposition 3: Strategic Partnerships and Navigating Geopolitical Uncertainty.

- Proposition 3: Indian entrepreneurs who take advantage of policies and form strategic partnerships with foreign firms will have an advantage in reducing risks and capitalizing on opportunities arising from geopolitical shifts.

- Rationale: Partnerships spread risk across different markets and economies. Foreign partners offer expertise in local regulations, cultural nuances, and potential political challenges, which combine to minimize risk. Partnerships open new markets, allowing businesses to reach customers they could not access independently. Foreign partners also provide access to unique resources, such as raw materials, specialized technology, or a skilled workforce.

- Theoretical Grounding: This proposition highlights the value of collaboration and knowledge sharing in navigating complex international relations, accessing new markets, and leveraging complementary resources that combine to generate competitive advantages (Gammeltoft & Panibratov, 2024; Gulati, 1998; Lu & Beamish, 2001).

- Proposition 4: Innovation Capability and Institutional Adaptation.

- Proposition 4: Indian entrepreneurs with strong innovation capabilities will be quicker at adapting to evolving environments, leading to success in both domestic and international markets.

- Rationale: The ability to identify and implement new ideas enables entrepreneurs to adjust their products, services, or business models to match evolving customer desires. Innovation is critical in global markets, as different regions have unique needs and rapidly changing trends; this requires entrepreneurs to be agile and adaptable.

- Theoretical Grounding: The RBV suggests that continuous innovation enables entrepreneurs to respond to changing regulations, leverage new technologies, and develop unique offerings that meet the evolving needs of diverse markets (Christensen & Overdorf, 2000; Hu & Kee, 2022; Teece et al., 1997).

In recognition of the interrelationship between the RBV and innovation ecosystem theory (Gueler & Schneider, 2021; Cuthbertson & Furseth, 2022), the next theory discussed is innovation ecosystem theory.

4.2. Innovation Ecosystem Theory

Innovation ecosystem (IE) theory provides clarity to the complexities of entrepreneurial success, particularly in dynamic contexts like India. IE recognizes that innovation does not occur in isolation, but within the interactions of interconnected actors and institutions. These include entrepreneurs, investors, research institutions, government agencies, and support organizations, forming a dynamic network that facilitates knowledge flows, resource sharing, and collaborative partnerships (Adner, 2017; Oh et al., 2016).

The ability to foster a conducive environment for entrepreneurial activity is the strength of an innovation ecosystem. This involves the presence of supportive government policies, a culture of collaboration, mechanisms for knowledge transfer, and the availability of resources such as funding and infrastructure (Stam, 2015). A robust innovation ecosystem can accelerate the development and commercialization of new ideas, enabling entrepreneurs to thrive and contribute to economic growth (Ma et al., 2019).

Government policies’ role in the development of innovative ecosystems shows that national governments have a role in developing the ecosystem vision, forming the ecosystem community, and organizing and nurturing ecosystem resources (Ng et al., 2023). Further, focused government investment in research and development results in increasing the number of patents, as well as trademark and industrial design applications, positively driving national innovation systems (Haq, 2023).

India’s entrepreneurial landscape is particularly well suited for analysis through the lens of innovation ecosystem theory. The country’s diverse network of actors, ranging from established research institutions and multinational corporations to grassroots startups and social enterprises, creates a rich tapestry of potential collaborations and knowledge spillovers (Nath et al., 2021). Furthermore, government initiatives like Startup India and Digital India have actively fostered the development of a supportive ecosystem, providing incentives, infrastructure, and platforms for entrepreneurial growth (Dutta & Banerjee, 2018). These incentives and infrastructure are foundational to innovative ecosystems (Ma et al., 2019).

However, India’s innovation ecosystem also faces challenges, including regulatory hurdles, infrastructure gaps, and regional disparities. Understanding these complexities through innovation ecosystem theory can help policymakers and entrepreneurs identify bottlenecks and develop strategies to strengthen the ecosystem, fostering greater innovation and entrepreneurial success (Tiwari & Herstatt, 2012). These challenges are actively being addressed (Nath et al., 2021).

Innovation Ecosystem Theory and Research Propositions

- Proposition 1: Ecosystem Navigation and Entrepreneurial Success.

- Proposition 1: In order to demonstrate greater success in terms of venture growth, profitability, and market share during periods of political upheaval, Indian entrepreneurs will need to effectively navigate and leverage the complexities of their local and global innovation ecosystems, including government agencies, research institutions, investors, and support organizations.

- Rationale: Leveraging ecosystem resources can provide a critical advantage in navigating uncertainty and achieving sustained growth. The interconnectedness of various actors and institutions in fostering innovation and entrepreneurial success is an emphasis of innovation ecosystem theory. In times of political uncertainty, managing this complex ecosystem becomes crucial.

- Theoretical Grounding: The “network relationships” and “institutional infrastructure” dimensions of innovation ecosystem theory highlight the importance of strong ties with diverse actors and supportive institutional frameworks (Oh et al., 2016; Spigel, 2017). This also is consistent with research on institutional entrepreneurship, emphasizing the role of actors in shaping institutional change and creating opportunities (DiMaggio, 1988).

- Proposition 2: Strategic Bridging and Resilience.

- Proposition 2: In order to exhibit greater resilience and adaptability in the face of global and domestic political changes, Indian entrepreneurs who proactively build “bridges” between their local innovation ecosystem and global networks can foster knowledge transfer, market expansion, and access to resources.

- Rationale: The importance of knowledge flows and resource exchange within an ecosystem is a critical element of innovation ecosystem theory. Entrepreneurs who can strategically connect their local ecosystem to global networks will be better positioned to access new markets, technologies, and talent during times of political upheaval. A buffer against domestic instability can enable entrepreneurs to leverage global opportunities for growth and diversification.

- Theoretical Grounding: The “knowledge and technology transfer” dimension of innovation ecosystem theory emphasizes the role of boundary spanners and knowledge brokers in facilitating innovation (Audretsch & Feldman, 2004; Agrawal, 2001). This is also consistent with research on international entrepreneurship that highlights the importance of global networks for accessing resources and foreign markets (Zahra & George, 2002).

- Proposition 3: Adaptive Innovation and Market Responsiveness.

- Proposition 3: To achieve greater market acceptance and competitive advantage, Indian entrepreneurs that engage in “adaptive innovation” by developing products and services that respond to the evolving needs and challenges arising from global and domestic political changes will be more successful.

- Rationale: The dynamic interplay between innovation and the environment is inherent in innovation ecosystem theory. Political upheavals can create new needs and challenges, which may require entrepreneurs to adapt their offerings and business models. Indian entrepreneurs who can identify and respond to these evolving needs, whether through developing new products, adapting existing ones, or creating new service models, will be better positioned to capture market share and achieve success (Nath et al., 2021).

- Theoretical Grounding: This proposition draws on the “entrepreneurial culture and capabilities” dimension of innovation ecosystem theory, emphasizing the importance of entrepreneurial alertness, learning, and adaptation (Roundy et al., 2018; Isenberg, 2010). It also aligns with research on dynamic capabilities, which emphasizes the ability of firms to sense, seize, and reconfigure resources to maintain a competitive advantage in dynamic environments (Teece et al., 1997).

- Proposition 4: Leveraging Digital Platforms for Ecosystem Expansion.

- Proposition 4: Indian entrepreneurs who effectively utilize digital platforms and technologies to expand their innovation ecosystem, connect with stakeholders, and access global markets will demonstrate greater resilience and growth during periods of political uncertainty.

- Rationale: The role of technology in facilitating knowledge flow and resource exchange is key in innovation ecosystem theory. It recognizes the role digital platforms can play in enabling entrepreneurs to overcome physical limitations, access information, and connect with stakeholders across geographical boundaries. Indian entrepreneurs can build more resilient and globally integrated ecosystems by leveraging digital tools for communication, collaboration, and market expansion.

- Theoretical Grounding: The role of digital technologies in facilitating knowledge diffusion and strengthening network ties builds on the “knowledge and technology transfer” and the “network relationships” dimensions of innovation ecosystem theory (Adner & Kapoor, 2010; Iansiti & Levien, 2004). Research on digital entrepreneurship, which emphasizes the transformative potential of digital technologies for creating new business models and accessing global markets, is consistent with this proposition (Nambisan et al., 2017).

4.3. Global Value Chain Theory

Global value chain (GVC) theory analyzes how firms engage in interconnected production processes across borders to deliver a final product or service (Benito et al., 2019). GVC theory emphasizes gaining value through the disaggregation of production, where different firms specialize in increasing the value creation process for the whole value chain. GVC theory highlights governance structures within GVCs, which determine power dynamics, knowledge transfer, and upgraded opportunities for participating firms (Gereffi et al., 2005; Ponte & Sturgeon, 2014). By understanding their position and relationships within a GVC, firms can strategize for competitiveness and development in the global economy.

Countries also play a role in increasing the value within a global value chain. Through the development of a skilled workforce and with the infrastructure to efficiently cover geographic distances, along with policies to help ameliorate cultural differences, a country can make itself an attractive location for GVC activities (Gereffi et al., 2021). Further, the countries themselves receive value in GVC participation through jobs being created, social improvements, environmental/infrastructure improvement, and flows of technology (Veeramani & Dhir, 2022; De Marchi & Alford, 2022). Fernandez-Stark and Gereffi (2019) notes that these gains themselves translate into increased national competitiveness and increased standards of living.

Global Value Chain Theory and Research Propositions

- Proposition 1: Strategic Positioning for Value Capture.

- Proposition 1: Even amidst favorable or unfavorable global political upheaval and domestic policy changes, Indian entrepreneurs will be able to capture greater value and enhance their competitiveness by strategically positioning themselves within global value chains (GVCs) by specializing in higher-value activities and developing unique capabilities.

- Rationale: GVC theory emphasizes that firms can upgrade their position within a value chain by moving from low-value activities, such as assembly or basic manufacturing, to higher-value activities like design, R&D, or marketing. One such example is that cocoa-bean-growing countries hardly receive any value from their agricultural products. Most value is derived upstream when the beans are used for making chocolate. Similarly, Indian entrepreneurs who proactively invest in skills development, technology adoption, and innovation can strategically position themselves to capture a larger share of the value generated within a GVC. This strategic positioning can provide a buffer against external shocks and enhance entrepreneurs’ bargaining power within the chain.

- Theoretical Grounding: Within GVC theory, strategic positioning for value capture draws on the concepts of “upgrading” and “governance” (Gereffi, 1999; Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002). The importance of developing unique and valuable resources to achieve a competitive advantage also aligns with the resource-based view of the firm (Barney, 1991).

- Proposition 2: Leveraging GVCs for Risk Mitigation.

- Proposition 2: Indian entrepreneurs who diversify their participation in multiple GVCs, spanning different industries and geographies, will be more resilient to disruptions caused by global political upheavals and domestic policy changes.

- Rationale: GVC theory recognizes that when firms participate in global value chains, they can benefit from opportunities but are vulnerable to risks, such as political instability, trade wars, and policy changes. These can disrupt value chains and create uncertainty for participating firms. Indian entrepreneurs who diversify their GVC engagement across different sectors and regions can mitigate these risks by reducing their dependence on any single market or value chain. For example, China has been reducing its overreliance on the US market by developing other markets. This type of diversification can enhance Indian entrepreneurs’ resilience and adaptability in the face of external shocks.

- Theoretical Grounding: The concept of “chain diversification” is like stock diversification in an investment portfolio. Markowitz (1952) suggested that a diversified portfolio reduces risk while maximizing returns. Similarly, participation in multiple GVCs will reduce risk exposure and build resilience (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2001).

- Proposition 3: Building Collaborative Networks within GVCs.

- Proposition 3: Indian entrepreneurs who seek to develop collaborative connections with lead firms and other main actors within GVCs will gain access to knowledge, technology, and market opportunities. This, in turn, will help them remain modern and even grow even during periods of political turmoil.

- Rationale: GVC theory emphasizes that all firms in a value chain develop a symbiotic relationship and share knowledge to make the value chain perform effectively. By being a part of a GVC, Indian entrepreneurs will have the opportunity to develop a strong relationship with lead firms and other key actors. Thus, Indian entrepreneurs would gain access to valuable resources, technologies, and market information, which will be critical for them to achieve competitiveness on the global stage.

- Theoretical Grounding: GVC theory supports the concepts of mutual learning and upgrading. Hence, a participant in a GVC will benefit from knowledge spillover from its partnerships within a value chain (Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002; Giuliani et al., 2005). Social network theory also suggests that relationships and network structure facilitate access to resources and information (Granovetter, 1973). A recent study by Rigo (2021) also confirms that GVCs are a vehicle for technology transfer to developing nations.

- Proposition 4: Leveraging Domestic Policy Changes for GVC Integration.

- Proposition 4: Given the pace of recent domestic policy changes, such as trade liberalization, investment incentive, and infrastructure growth in India, Indian entrepreneurs who proactively leverage these to enhance their integration into GVCs will benefit from global opportunities.

- Rationale: GVC theory recognizes the role of government policies in enhancing the competitiveness of firms within global value chains. Indian entrepreneurs who can effectively leverage these policy changes to enhance their capabilities and competitiveness will be better equipped to integrate into GVCs and capture a greater share of the value generated within these chains.

- Theoretical Grounding: This proposition builds on the “institutional environment” dimension of GVC theory, which highlights the importance of supportive government policies and regulations for facilitating GVC integration (Gereffi et al., 2005). It also matches up with institutional theory, which suggests that institutions play an important role in shaping economic behavior and firm performance (North, 1990).

5. Discussion

This paper has explored the dynamic landscape of India’s entrepreneurial awakening, examining the intricate interplay of geopolitical shifts, domestic policy reforms, and theoretical frameworks. For each of the three theories, an overview was provided along with propositions related to the governmental policies and the opportunities created for entrepreneurs based on the theory foundations. The rationale and the literature support for each proposition were detailed. The analysis has revealed a complex and evolving ecosystem, with government policies supporting entrepreneurial agility.

The findings underscore the significant impact of geopolitical realignments on India’s entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurial activity across various sectors is enhanced by the diversification of supply chains away from China and the increasing strategic importance of the Indo-Pacific region (McKinsey Global Institute, 2023; Pant, 2022). A more conducive environment for innovation and business growth has been enhanced by domestic policy reforms, including “Make in India”, “Digital India”, and “Startup India” (Kumar, 2018).

Through the application of three theories—RBV, GVC, and innovation ecosystem theory—this paper has highlighted the critical role of formal and informal institutions in shaping entrepreneurial behavior and outcomes. The overall ease of doing business is impacted by the evolving regulatory landscape, government policies, and cultural norms that influence resource access and legitimacy. The importance of leveraging India’s unique resources, such as its vast talent pool, diverse consumer market, and burgeoning digital infrastructure to create and capture value is an integral component of the resource-based view (Barney, 1991).

The practical results are clear. Since the present political party came to office in 2014, India’s entrepreneurial ecosystem has seen a huge increase in the number of startups and unicorns—privately held startup companies valued at over USD 1 billion. NASSCOM (2022) reported that there are 27,000 startups, which makes India the third-largest startup ecosystem in the world. This growth can be attributed to three key factors: supportive government policies, increased funding opportunities, and rapid technological advancements.

Among the government initiatives, the one that stands out most is the Startup India initiative of 2016. This program provided tax exemptions and relief in terms of compliance requirements, and established the Fund of Funds for Startups (FFS) of INR 100 billion (about USD 1.17) to support early-stage ventures (DPIIT, 2022).

Under the government’s Digital India Initiative (DII) of 2015, India has experienced expanding internet access and increased digital literacy, which in turn have supported a conducive environment for technology-based businesses (MeitY, 2015). Another development that coincided with DII was the introduction of inexpensive mobile data by Reliance Jio in 2016. The increase in competition in the mobile data space boosted internet penetration to over 50% by 2021 (TRAI, 2021). As a result, startups could turn their attention to the previously underserved markets of rural and semi-urban areas. Companies such as Byju’s (online education, established in 2011), Zomato, and Paytm jumped on these advancements to disrupt traditional industries (Kenney & Zysman, 2016).

India has also seen a great rise in venture capital and private equity funding. Total annual startup funding grew from USD 2.2 billion in 2014, as mentioned earlier, to over USD 36 billion in 2021. This is a clear indication that investors have become confident in India’s entrepreneurial ecosystem (Bain & Company, 2022). Not just domestic, but also global investors (e.g., SoftBank and Sequoia Capital) have started pouring in funds, providing startups with ample resources to innovate and scale up their operations.

In the last 10 years, there is evidence that startups are showing up in diverse focus areas. The e-commerce and fintech areas are still the darling of startups, but sectors like healthcare, education technology (edtech), and aggrotech are also attracting entrepreneurs’ attention. For instance, startups like DeHaat, which is a play on the Hindi word “dehat”—a remote village—are focused on deploying technology to address grassroot problems related to inefficiencies in the agricultural supply chain (NASSCOM, 2022). Additionally, startups in India are also utilizing artificial intelligence, blockchain, and robotics to create cutting-edge solutions (DPIIT, 2022).

There is ample evidence that the reforms under the present government have been effective to promote an entrepreneurial environment in India. This is evidenced in the World Bank rating of India: In the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) 2015–16, India moved up from its earlier ranking of 71 out of a total of 144 countries to a ranking of 55. As of 2023, India was ranked as 39th in the world.

6. Conclusions

The powerful and unravelling entrepreneurial ecosystem in India is shaped by geopolitical shifts, domestic policy reforms, and the strategic actions of entrepreneurs. By understanding these complex dynamics and by incorporating the insights offered by the resource-based view, global value chain theory, and innovation ecosystem theory, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and investors can contribute to India’s continued economic growth and its emergence as a global entrepreneurial powerhouse (Gereffi et al., 2005; North, 1990; Barney, 1991; Adner, 2017). The journey ahead is filled with opportunities and challenges, but with strategic foresight and collaborative efforts, India’s entrepreneurial awakening can pave the way for a brighter and more prosperous future that would bring back the glory from India’s golden past.

7. Theoretical Contributions and Future Research Directions

This paper contributes to the existing literature by integrating innovation ecosystem theory, global value chain theory, and the resource-based view to provide a comprehensive understanding of India’s entrepreneurial landscape. By examining the interplay of these theoretical perspectives, this study offers insights into how entrepreneurs can navigate the institutional environment and leverage resources to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. The propositions presented in this paper offer a roadmap for future research and can guide empirical investigations into the specific factors driving entrepreneurial success in India, as well as the interplay of government policy and entrepreneurial success.

This article could lead to several future research studies. Importantly, this paper provides a nexus between governmental policy, entrepreneurial behavior, and management theory. Empirical investigations can test the propositions presented in the paper and explore the nuances of how geopolitical shifts and domestic policies impact entrepreneurial outcomes across different sectors and regions within India. Further, the role of informal institutions, such as social networks and cultural norms, in shaping entrepreneurial behavior and success may be explored more fully in further research. Comparative studies can also be conducted to examine how India’s entrepreneurial ecosystem differs from those in other emerging economies. Such studies can provide valuable insight into the unique factors driving India’s entrepreneurial revival and guide policy developments to further enhance the country’s entrepreneurial potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and K.S.; methodology, R.S. and K.S.; validation, R.S., K.S., J.N., and F.S.; formal analysis, R.S. and K.S.; investigation, R.S. and F.S.; resources, J.N. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and K.S.; writing—review and editing, F.S. and J.N.; visualization, R.S.; project administration, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| GPP | Gross Domestic Product |

| MNC | Multinational Corporation |

| DII | Digital India Initiative |

| GVC | Global Value Chain |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

References

- Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. (2010). Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Management Journal, 31(3), 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. (2001). Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Development, 29(10), 1649–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2010). Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Aiyar, S. S. A. (2023, June 21). Indian nationalism and the historical fantasy of a golden hindu period. Cato Institute. Available online: https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/indian-nationalism-historical-fantasy-golden-hindu-period (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Allen-Ebrahaminian, B. (2021). Special report: Trump’s US-China transformation. Available online: https://www.axios.com/2021/01/19/trump-china-policy-special-report (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (2004). Knowledge spillovers and the geography of innovation. In J. V. Henderson, & J. F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 4, pp. 2713–2739). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bain & Company. (2022). India venture capital report 2022. Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/india-venture-capital-report-2022/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Bala Subrahmanya, M. H. (2022). Competitiveness of high-tech start-ups and entrepreneurial ecosystems: An overview. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 17(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, G. R., Petersen, B., & Welch, L. S. (2019). The global value chain and internalization theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 50, 1414–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A. (2022). India’s energy security in a changing geopolitical landscape. Energy Policy, 167, 113116. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2010). The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, B., & Collins, S. M. (2008). Accounting for growth: Comparing China and India. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(1), 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- CB Insights. (2023). The global unicorn club. Available online: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/unicorn-startups-valuations-headcount-investors/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Chatterjee, D., & Kar, A. K. (2020). Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem in India: A tale of opportunity and challenges. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(4), 598–623. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. M., & Overdorf, M. (2000). Meeting the challenge of disruptive change. Harvard Business Review, 78(2), 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P. (2001). Industrial innovation and learning systems: Sector strategies for value chain linkage. In UNIDO world industrial development report. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson, R. W., & Furseth, P. I. (2022). Digital services and competitive advantage: Strengthening the links between RBV, KBV, and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 152, 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, V., & Alford, M. (2022). State policies and upgrading in global value chains: A systematic literature review. Journal of International Business Policy, 5(1), 88–111. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z., Yan, J., & Sun, P. (2020). Political status and tax haven investment of emerging market firms: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(3), 469–488. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, A. (2024, December 20). India’s Unified payments interface has revolutionized its digital payments market. Cornell SC Johnson College of Business. Available online: https://business.cornell.edu/hub/2024/12/20/indias-unified-payments-interface-has-revolutionized-its-digital-payments-market/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- DiMaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. G. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organizations: Culture and environment (pp. 3–21). Ballinger Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- DPIIT. (2022). States’ startup ranking 2022: National report. Available online: https://www.startupindia.gov.in/srf/images/SRF_2022_Result_page/National_Report_14_01_2024.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Dutta, S. (2019). Startup India: Fostering innovation and entrepreneurship. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 44(3), 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S., & Banerjee, S. (2018). Startup India: Towards building an innovation ecosystem. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 43(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, N., & Sharma, D. (2021). The China plus one strategy in the post-COVID-19 world: Opportunities and challenges for India. Journal of Asian Economics, 76, 101379. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Stark, K., & Gereffi, G. (2019). Global value chain analysis: A primer. In Handbook on global value chains (pp. 54–76). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gammeltoft, P., & Panibratov, A. (2024). Emerging market multinationals and the politics of internationalization. International Business Review, 33(3), 102278. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G. (1999). International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics, 48(1), 37–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G., Lim, H. C., & Lee, J. (2021). Trade policies, firm strategies, and adaptive reconfigurations of global value chains. Journal of International Business Policy, 4(4), 506. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development, 33(4), 549–573. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, O. (2010). The economic history of colonial India. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. (2016, October 12). Launch of new initiatives by the ministry of information and broadcasting. Press Information Bureau. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=147661 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Goyal, P. (2020). Infrastructure development in India: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of Infrastructure Development, 12(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Gueler, M. S., & Sc hneider, S. (2021). The resource-based view in business ecosystems: A perspective on the determinants of a valuable resource and capability. Journal of Business Research, 133, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Guillen, M. F. (2000). Business groups in emerging economies: A resource-based view. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 362–380. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, N. U. (2023). Impact of FDI and its absorption capacity on the national innovation ecosystems: Evidence from the largest FDI recipient countries of the world. Foreign Trade Review, 58(2), 259–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M. K., & Kee, D. M. H. (2022). Fostering sustainability: Reinventing SME strategy in the new normal. Foresight, 24(3/4), 301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). The keystone advantage: What the new dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D. J. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplinsky, R., & Morris, M. (2001). A handbook for value chain research. International Development Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, R., & Vaidya, S. (2013). Entrepreneurship in India: A review and future directions. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 38(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, K., & Kumar, S. (2024). Resource-based view and SME internationalization: A systematic literature review of resource optimization for global growth. Management Review Quarterly, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2016). The rise of the platform economy. Issues in Science and Technology, 32(3), 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (1997). Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75(4), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, R., & Bhagwati, J. (2012). India’s rise as an economic superpower: Choices and challenges. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. (2023). Venture pulse Q1 2023 global analysis of venture funding. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2024/01/venture-pulse-q4-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- KPMG. (2024, July). Transforming India’s infrastructure: A futuristic roadmap through budget 2024–25. KPMG India. Available online: https://kpmg.com/in/en/blogs/2024/07/transforming-indias-infrastructure-a-futuristic-roadmap-through-budget-2024-25.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Kumar, N. (2018). Modi’s India. Journal of Democracy, 29(2), 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T., & Li, X. (2022). How Do MNCs Conduct local technological innovation in a host country? An examination from subsidiaries’ perspective. Journal of International Management, 28(3), 100951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2001). The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 565–586. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L., Liu, Z., Huang, X., & Li, T. (2019). The impact of local government policy on innovation ecosystem in knowledge resource scarce region: Case study of Changzhou, China. Science, Technology and Society, 24(1), 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Marois, G., Zhelenkova, E., & Ali, B. (2022). Labour force projections in India until 2060 and implications for the demographic dividend. Social Indicators Research, 164(1), 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, J., Berman, N., & Chatzky, A. (2023, February 2). China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative. Council on Foreign Relations. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2023). Risk, resilience, and rebalancing in global value chains. McKinsey & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, Y., & Rajan, A. J. (2017). Manufacturing sectors in India: Outlook and challenges. Procedia Engineering, 174, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- MeitY. (2015). Digital India. Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India.

- Moon, C. W., & Lado, A. A. (2000). MNC-host government bargaining power relationship: A critique and extension within the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 26(1), 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, W. M. (2019). China’s economic rise: History, trends, challenges, and implications for the United States. Current Politics and Economics of Northern and Western Asia, 28(2/3), 189–242. [Google Scholar]

- MyGov India. (n.d.). Digital India. MyGov India. Available online: https://www.mygov.in/campaigns/digitalindia/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2017). The digital transformation of innovation ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 11(4), 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- NASSCOM. (2022). Tech start-up report 2022. Available online: https://community.nasscom.in/communities/nasscom-insights/nasscom-tech-start-report-2022-rising-above-uncertainty-2022-saga (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Nath, S., Sengupta, S., & Chattopadhyay, S. K. (2021). India’s innovation ecosystem for productivity-led growth: Opportunities and challenges. Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, 42(2), 67–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, H. Y., Luo, Y., & Park, H. (2023). The role of intermediaries in nurturing innovation ecosystems: A case study of Singapore’s manufacturing sector. Science and Public Policy, 50(3), 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, D. S., Phillips, F., Park, S., & Lee, E. (2016). Innovation ecosystems: A critical examination. Technovation, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Panagariya, A. (2008). India: The emerging giant. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, H. V. (2022). India’s evolving grand strategy: A shift from non-alignment to strategic autonomy. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte, S., & Sturgeon, T. (2014). Explaining governance in global value chains: A modular approach—Bridging the macro-micro divide. Review of International Political Economy, 21(1), 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjou, N., Prabhu, J., & Ahuja, S. (2012). Jugaad innovation: Think frugal, be flexible, generate breakthrough growth. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Rigo, D. (2021). Global value chains and technology transfer: New evidence from developing countries. Review of World Economics, 157(2), 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P. T., Brockman, B. K., & Bradshaw, M. (2018). The resource orchestration perspective: A dynamic capabilities approach to entrepreneurial strategy. Journal of Management Studies, 55(1), 130–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sony, M., & Aithal, P. S. (2020). A resource-based view and institutional theory-based analysis of industry 4.0 implementation in the Indian engineering industry. International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Sciences (IJMTS), 5(2), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, K. (2021). Digital India: Technology, governance and the state. Economic and Political Weekly, 56(10), 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 25(4), 945–967. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar]

- The Financial Express. (2023, August 15). Tracing the roots of business sector through India’s rich history. The Financial Express. Available online: https://www.financialexpress.com/life/lifestyle-celebrating-76-years-of-independence-tracing-the-roots-of-entrepreneurial-journey-through-indias-rich-history-from-the-indus-valley-civilization-to-present-day-3194951/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Tiwari, R., & Herstatt, C. (2012). India’s emerging innovation system. International Journal of Technology Management, 57(1–2), 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- TRAI. (2021). Yearly Performance Indicators: Indiana Telecom Sector. Available online: https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/2024-09/YIR_15092021_0.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Truong, B. T. T., Nguyen, P. V., & Vrontis, D. (2024). Enhancing firm performance through innovation: The roles of intellectual capital, government support, knowledge sharing and knowledge management success. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 25(1), 188–209. [Google Scholar]

- Veeramani, C., & Dhir, G. (2022). Do developing countries gain by participating in global value chains? Evidence from India. Review of World Economics, 158(4), 1011–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). Doing business 2023. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). International entrepreneurship: The current status of the field and future research agenda. In M. A. Hitt, R. D. Ireland, S. M. Camp, & D. L. Sexton (Eds.), Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset (pp. 255–288). Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).