Strategic Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as a Catalyst for Sustainable Governance: Integrating Equity, Climate Resilience, and Renewable Energy in the IMSD Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Integrating Sustainability, Equity, and Leadership in Organizational Strategy

- Institutional Theory ensures alignment with evolving legitimacy norms, regulatory demands, and stakeholder expectations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Fagerland & Drejer, 2018).

- Resource-Based View and Dynamic Capabilities provide a lens for leveraging diversity and inclusive leadership as strategic assets in turbulent environments (Barney, 1991; Teece, 2007).

- Intersectionality Theory embeds an understanding of structural inequalities and compound vulnerabilities, ensuring inclusive adaptation and social justice (Crenshaw, 1989; A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022).

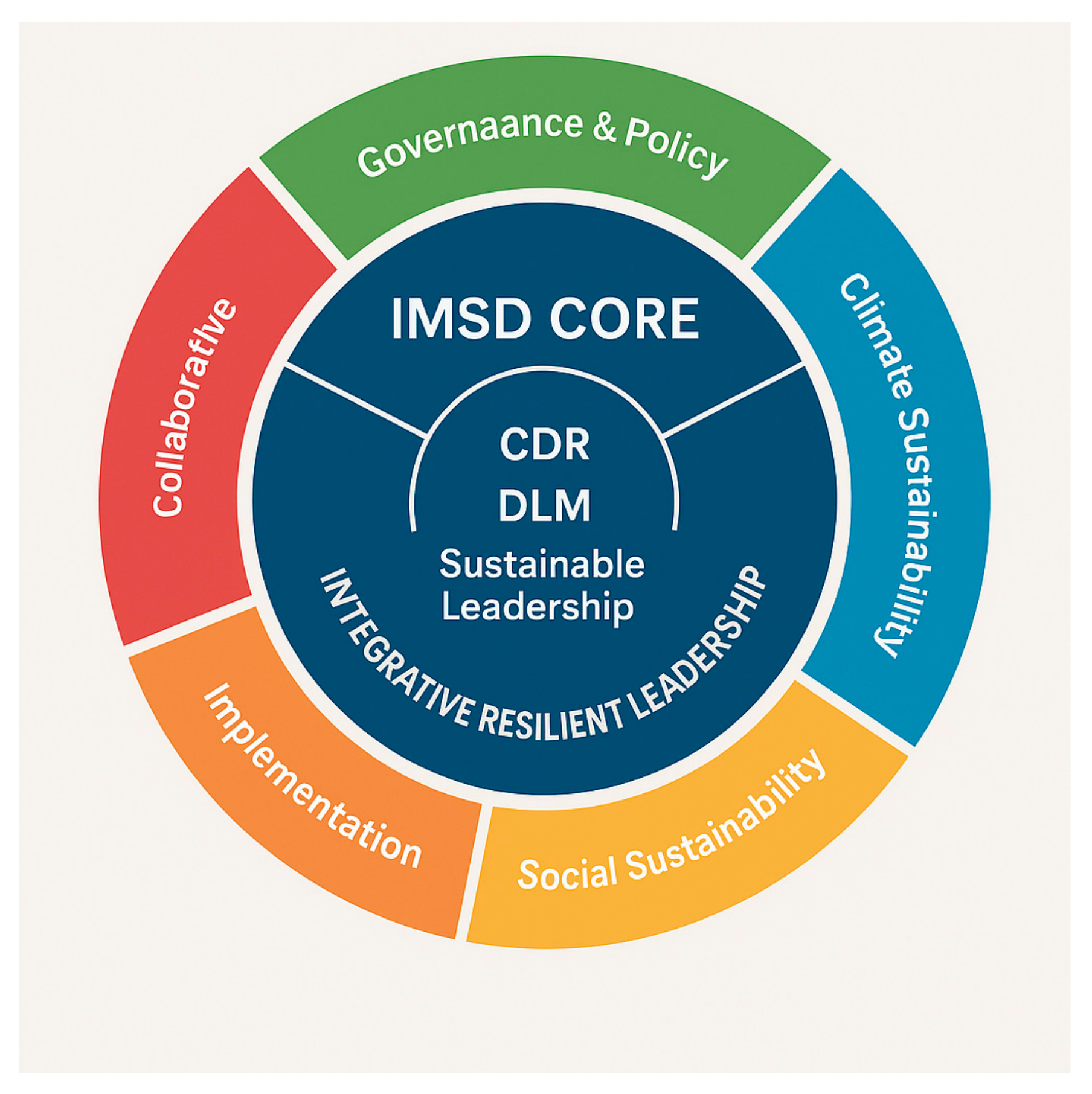

2. Overview of the IMSD Framework

2.1. Purpose and Intended Users

- Corporate executives and board members aiming to align ESG strategies with inclusive governance and emerging regulatory expectations (Ali et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023);

- Policymakers and public sector leaders working to institutionalize equity in climate adaptation and sustainability policy (Krishnan & Robele, 2024);

- Civil society organizations and multilateral institutions advocating for justice-based and intersectional sustainability transitions (UN Women, 2023a; Swanson, 2023);

- Academic institutions and think tanks advancing research, innovation, and evaluation in sustainability governance (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025).

2.2. Practical Use and Application

- Conducting equity audits and assessing institutional readiness for inclusive sustainability transitions (Sajjad et al., 2024);

- Designing leadership development programs grounded in dynamic capabilities and intersectional governance (Fagerland & Fjuk, 2025a; Boeske, 2023);

- Aligning ESG reporting and corporate disclosures with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality), and SDG 13 (Climate Action) (UNFCCC, 2021; Leonidou et al., 2024);

- Integrating intersectionality into governance indicators, investment strategies, and performance management systems (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Mikulewicz et al., 2023).

2.3. Structural Overview: The Five Pillars of IMSD

2.4. Summar

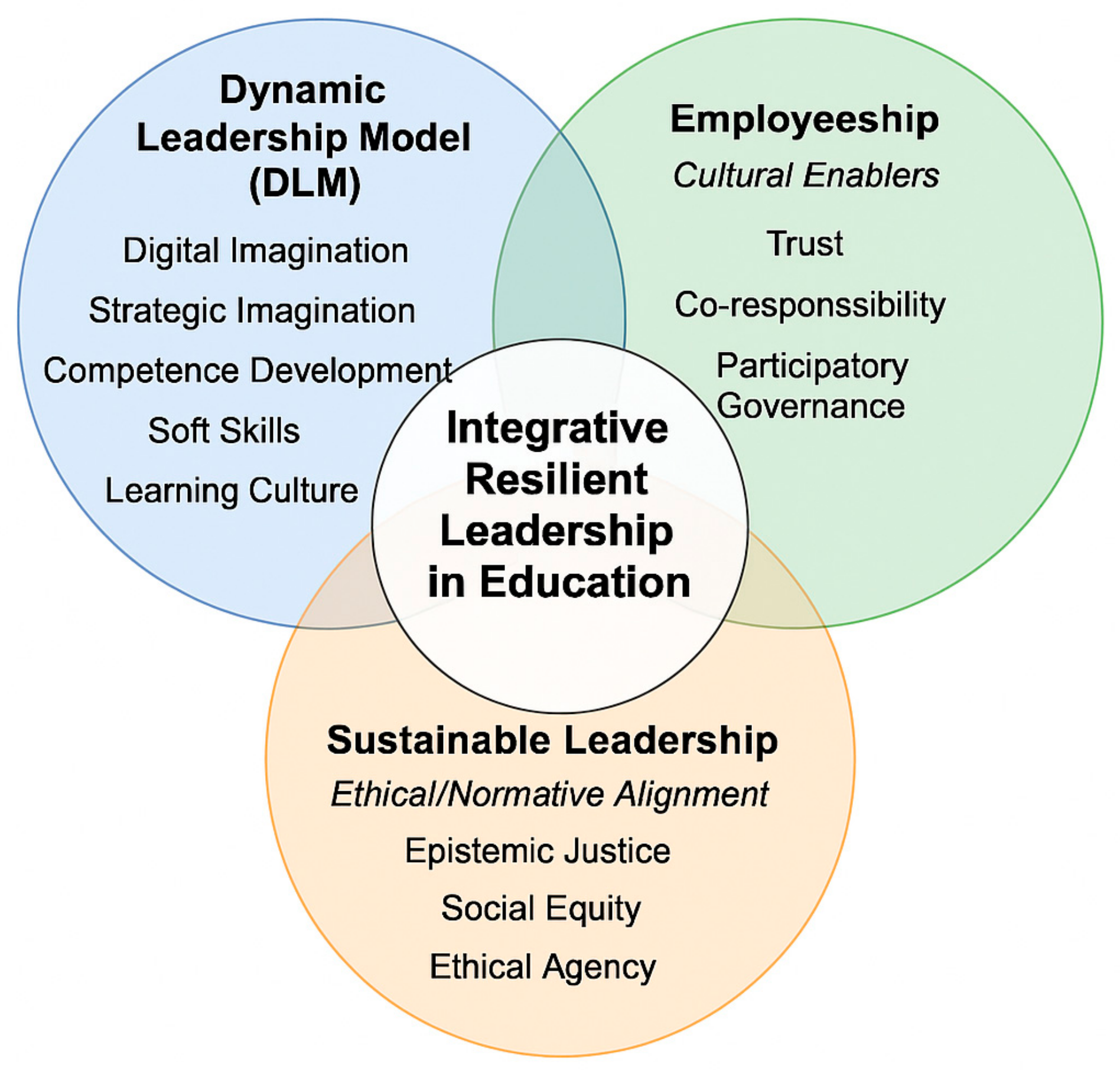

3. Theoretical Foundations of the IMSD

- Digital imagination;

- Strategic imagination;

- Soft skills;

- Competence development;

- Learning culture.

3.1. In the Context of IMSD

- Leadership operationalizes Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) by embedding it into institutional routines and strategic agendas (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025);

- It activates adaptive governance through mobilizing foresight, equity literacy, and inclusive decision-making (Anane-Simon & Atiku, 2023);

- It facilitates cross-pillar integration, ensuring climate action, equity, and innovation mutually reinforce each other rather than remaining siloed (McKinsey & Company, 2020a, 2020b).

3.2. Clarifying Key Concepts: Resilience, Adaptation, and Justice

- Climate resilience is defined as the capacity of socio-ecological systems to absorb shocks and maintain essential functions under climate-related stressors (IPCC, 2014a; Mikulewicz et al., 2023). Within IMSD, resilience is anticipatory, transformative, and equity-informed, emphasizing both technical innovation and institutional mechanisms.

- Resilience strategies must address social and ecological dimensions, incorporating nature-human interactions and traditional ecological knowledge Attributes such as population abundance, learning capacity, responsive governance, ecosystem connectivity, and place attachment are key to resilience pathways. Two primary pathways involve strengthening rural community and ecosystem resilience or enhancing economic assets and governance in urban settings Embedding adaptation strategies into development planning is critical for bolstering overall system resilience (Hosan et al., 2024).

- Climate adaptation encompasses anticipatory and reactive strategies for risk and uncertainty management. IMSD embeds adaptation into strategic foresight, leadership development, and systems design, with particular attention to uneven exposure and differentiated adaptive capacities among marginalized communities (UNFCCC, 2021; Gutterman, 2022; Reyes-García et al., 2024).

- Climate justice emphasizes procedural and distributive equity in climate action (Bullard, 2005; Sultana, 2021), ensuring adaptation and resilience strategies are inclusive and effective (Recent scholarship underscores the need to focus on procedural justice alongside recognitional and distributional justice in climate adaptation (Brousseau et al., 2024). Participatory urban governance approaches should prioritize vulnerable populations (Swanson, 2023). Higher education institutions can promote climate justice by embedding it into teaching, research, and community engagement agendas (Kinol et al., 2023). Analysis of US city adaptation plans reveals equity influences policy through recognition-driven pathways.

3.3. Institutional Theory: Legitimacy, Isomorphism, and Governance Alignment

3.4. Resource-Based View (RBV): Diversity as a Strategic Intangible Asset

- Defining CDR as a mechanism for capturing intangible value through inclusive leadership.

- Demonstrating strong correlations between gender-diverse leadership and ESG performance outcomes (McKinsey & Company, 2020a);

- Enabling strategic agility in rapidly transitioning sectors like renewable energy (Ekechukwu & Simpa, 2024).

- This aligns with growing scholarship recognizing intangible assets as central to innovation capacity and long-term value creation (Mailani et al., 2024).

3.5. Intersectionality Theory: Operationalizing Inclusive Climate Governance

- Promoting governance processes that amplify marginalized voices through participatory and equity-focused models

- Identifying how intersecting social positions affect access to resilience strategies (Roy et al., 2022);

- Embedding equity and justice within ESG metrics and corporate disclosure practices (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022).

3.6. IMSD as a Multidimensional Governance Model

4. A New Paradigm for Leadership in Sustainable Development

4.1. Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as an Institutional Pillar of IMSD

4.2. Institutional Theory and CDR Integration

4.3. CDR as a Strategic Imperative in Corporate Governance

- Innovation: through cognitive diversity and inclusive leadership, CDR catalyzes novel problem-solving and low-carbon innovation (Ekechukwu & Simpa, 2024);

- Resilience: diverse leadership enhances agility and adaptive governance in volatile and uncertain contexts (Leonidou et al., 2024);

- Legitimacy: representation in leadership strengthens social license to operate and investor confidence.

4.4. The Role of CDR in Sustainable Business Strategy

- Renewable Energy: Diverse teams enhance decision-making and innovation in renewable energy transitions, driving sustainability and equity (Olutimehin et al., 2024; Sharma & Patel, 2023); Strategies such as workforce diversity and inclusive engagement support comprehensive green energy solutions (Ghorbani et al., 2024).

- Supply Chains: CDR fosters transparency, anti-discrimination, and ethical procurement (Leonidou et al., 2024);

- Compliance and Reporting: CDR supports proactive adaptation to evolving regulatory landscapes, including EU taxonomy and corporate sustainability disclosure standards (McKinsey & Company, 2020b; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023).

4.5. Intersectionality and Institutional Adaptation in CDR Governance

- Equity-sensitive policy design;

- Institutional responsiveness in climate-vulnerable regions;

- Inclusive governance for marginalized stakeholders in transition processes

4.6. CDR as a Cornerstone of Future Institutional Governance

- Align diversity initiatives with innovation ecosystems and risk management practices;

- Strengthen organizational legitimacy through inclusive leadership and ethical reporting;

- Build institutional capacities for long-term resilience and stakeholder alignment (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025).

4.7. Strategic Governance Contributions of CDR

“CDR shifts the focus from representation to regeneration—embedding justice into the very DNA of governance”.

4.8. Methodological Foundations and Practical Application of IMSD

5. Operationalizing IMSD: Architecture, Modularity, and Governance Design

5.1. IMSD as a Modular Architecture for Systems Change

5.2. From Principle to Practice: Translating Governance into Action

- Intersectional equity mechanisms in recruitment, leadership, and decision-making (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Swanson, 2023);

- Digital foresight and innovation capacity embedded within institutional processes (Demneh et al., 2023; Grove et al., 2023);

- ESG-aligned metrics integrated into adaptive policy cycles and reporting frameworks (Galleli et al., 2023a; Dasinapa, 2024).

5.3. IMSD as a Blueprint for Governance Innovation

- Cross-sectoral applicability (Leonidou et al., 2024);

- Flexibility under regulatory and climate uncertainty (Zhang, 2023; Mitra & Shaw, 2023);

- Compatibility with multilateral climate and equity frameworks (IPCC, 2014a; UNFCCC, 2021).

5.4. IMSD as a Driver of Systemic Governance Transformation

5.5. The Future of CDR in Institutional Governance

- Fostering trust through representation and equity-oriented strategies that contribute to long-term organizational resilience (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025).

- Navigating evolving ESG and DEIB reporting frameworks with integrity, ensuring that equity and sustainability principles are embedded in corporate strategy (McKinsey & Company, 2020b).

- Developing inclusive leadership capabilities to address ongoing sustainability challenges, ensuring that diversity remains a central driver of governance and organizational performance.

5.6. Strategic Integration of CDR Across Governance Levels

5.7. Summary and Strategic Contributions

6. Operationalizing the IMSD Framework in Practice

6.1. Climate Sustainability Pillar

6.2. Social Sustainability Pillar

- Leadership diversity and participatory decision-making (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025; The Korea Times, 2023a; UN Women, 2023a).

- Community engagement and co-production of sustainability policies (Swanson, 2023; A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022).

- Equity assessments mapping systemic disparities in impact and access (Sultana, 2022; Mikulewicz et al., 2023).

6.3. Governance and Policy Integration

6.4. Collaborative Partnerships

- Distributed responsibility across public and private sectors (Greenwood et al., 2002).

- Joint investments in inclusive sustainability innovations (Leonidou et al., 2024).

- Shared governance models tackling climate and equity challenges (Ekechukwu & Simpa, 2024).

6.5. Implementation and Monitoring

- Use intersectionality-informed KPIs and disaggregated data to capture nuanced equity outcomes (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Swanson, 2023).

- Engage communities in feedback loops to inform iterative policy development (Brousseau et al., 2024).

- Employ digital foresight tools to anticipate equity and climate vulnerabilities, fostering proactive governance (Demneh et al., 2023; Grove et al., 2023).

6.6. Strategic Implications and Institutional Impact

7. Aligning IMSD with the SDGs, ESG Frameworks, and Future Research

- SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, by advancing decentralized, just energy systems that prioritize equitable access and resilience (Mysore, 2024; Muthusamy Thirumalai et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2023). This is critical given the role of energy as a social determinant of health and economic participation (Roy et al., 2022).

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequality, through institutionalization of inclusive governance practices and embedding CDR to drive equitable distribution of resources, leadership pipelines, and opportunity (Sbîrcea, 2023; Fagerland & Behdani, 2025). This structural inclusion addresses intersectional vulnerabilities by tailoring policies to marginalized groups’ compound risks (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Mikulewicz et al., 2023).

- SDG 13: Climate Action, by reframing climate adaptation as an equity-centered governance challenge, embedding justice and participatory frameworks that uplift historically excluded voices (Sultana, 2022; Brousseau et al., 2024). IMSD’s emphasis on transparent, intersectional KPIs strengthens monitoring of social and environmental outcomes (Leonidou et al., 2024).

7.1. IMSD and SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

7.2. IMSD and SDG 10: Reduced Inequality

7.3. IMSD and SDG 13: Climate Action

7.4. IMSD and ESG Integration

7.5. IMSD as a Scalable, Research-Informed Framework

7.6. Future Research and Empirical Validation

- Longitudinal evaluations that measure CDR’s impact on organizational resilience, innovation trajectories, and ESG performance metrics over extended time horizons (Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Sajjad et al., 2024).

- Cross-sectoral and geographic implementation studies to investigate IMSD’s transferability across industries such as education, finance, and energy, as well as diverse regional contexts including the Global South (Leonidou et al., 2024; Kinol et al., 2023).

- Development of intersectionality-informed KPIs tailored to rigorously quantify equity outcomes within climate and sustainability governance structures (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Swanson, 2023).

- Technological integration research exploring how AI, digital foresight tools, and advanced data analytics can enhance IMSD’s dynamic and adaptive governance capabilities (Demneh et al., 2023).

- Policy diffusion analysis to evaluate how IMSD principles influence the evolution of national and international climate governance frameworks and ESG regulatory regimes (Greenwood et al., 2002).

8. Conclusions

8.1. Final Synthesis

8.2. Limitations and Future Research

“Sustainability without equity is a half-built bridge. IMSD completes the span”. Fagerland and Bleveans (2024). Corporate Diversity Responsibility and Its Role in Transforming Governance (Statement at SHEconomy Summit, September 2024, Google headquarters, Silicon Valley).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDR | Corporate Diversity Responsibility |

| DLM | Dynamic Leadership Model |

| DEIB | Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging |

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| IMSD | Integrated Model for Sustainable Development |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| TCFD | Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures |

Appendix A. Supplementary Conceptual Foundations and Integrative Tables

Appendix A.1. CDR: A Strategic Governance Innovation

- Presented and positioned across over 90 countries through institutional networks and global dissemination efforts, including in the IPSOS global study Understanding Society: A Woman’s World (Ipsos, 2019).

- Embedded in leadership education (University of South-Eastern Norway, 2024–2025).

- Integrated into AI foresight and defense preparedness projects (CORDA Survey; Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025). Strategically positioned in over 90 countries through high-level keynotes and institutional forums, including UN Women (Seoul, Republic of Korea), Nordic Ministerial Summits, and SHEconomy leadership forums and summits (2018–present) with global tech leaders; prominently featured in leading international media—solidifying CDR’s status as a pioneering, globally recognized governance innovation.

- Supported by cross-sector partners including Google, Microsoft, Meta, Accenture, Storebrand, and the Norwegian Armed Forces.

| Dimension | Evidence Base |

|---|---|

| Academic Foundation | Fagerland and Drejer (2018); Fagerland and Behdani (2025); Fagerland (2019) |

| Cross-sector Endorsement | Endorsed and implemented across leading industries and sectors, including global technology companies, financial and insurance institutions, defense and security agencies, public sector bodies, higher education institutions, think tanks, and advocacy organizations. CDR has been recognized as a strategic governance tool by both private corporations and public institutions. |

| Policy and Defense Integration | GORDA Survey, Total Defense Strategy Applications (2024–2025) |

| Education Integration | Leadership curriculum at USN: BARLED and ESB100E (2024–2025) |

| ESG Relevance | Framework alignment with SDGs 5, 10, and 16; embedded in IMSD’s governance pillar |

| Global Positioning and Recognition | CDR has been strategically positioned across more than 90 countries through high-level international forums and cross-sector dialogue ranging from global sustainability summits and ministerial roundtables to executive leadership platforms. The concept has received wide recognition across continents and industries, featured in globally influential media, and acknowledged by leading institutions including the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), UN Women, and the Nordic Council of Ministers as a pioneering contribution to inclusive and resilient governance. |

Appendix A.2. IMSD and Model Framing References

| Theory/Framework | Key Scholar(s) | Contribution to IMSD | Cross-Sectoral Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional Theory | DiMaggio and Powell (1983); Greenwood et al. (2002) | Legitimacy-building; institutional adaptation; embedding CDR | ESG compliance, public governance, policy innovation |

| Resource-Based View (RBV) | Barney (1991); Teece (2007) | Frames CDR and leadership diversity as VRIN resources enabling sustained competitive advantage | Corporate strategy, innovation ecosystems, sustainability leadership |

| Intersectionality Theory | Crenshaw (1989); A. T. Amorim-Maia et al. (2022) | Anchors social sustainability through equity-sensitive design and governance | Justice-centered adaptation, climate governance, inclusive regulation |

| Dynamic Capabilities Theory | Teece et al. (1997) | Enables adaptive governance, digital foresight, and resilient leadership across institutional transitions | AI ethics, public sector transformation, digital infrastructure planning |

| Regenerative Leadership | Hutchins and Storm (2019) | Integrates ecosystemic ethics, stewardship, and long-term value thinking into governance | Sustainability education, executive development, system transformation |

| Institutional Entrepreneurship | Greenwood et al. (2002) | Positions leaders as agents of change who actively shape new governance norms | Organizational innovation, sustainable finance, future-oriented governance reforms |

| Digitalization and Governance | Henriette et al. (2015); Reis et al. (2018) | Operationalizes digital imagination and transformation in sustainability governance | AI foresight, ESG disclosure technologies, e-governance |

| Public Value and Legitimacy | Moore (1995); | Enhances model’s alignment with democratic governance and long-term stakeholder legitimacy | Civil society engagement, inclusive public sector innovation |

| Climate Justice and Adaptation | Sultana (2021); Reyes-García et al. (2024) | Frames climate resilience as an equity and rights-based imperative integrated into all IMSD pillars | Indigenous knowledge integration, SDG localization, participatory planning frameworks |

Appendix B. Methodology Supplement

Appendix B.1. CORDA Survey: Empirical Foundations from a Cross-Sector Pilot Study

- Design and Validation:

- The instrument was developed through a multi-stage process grounded in civil-military integration, organizational learning theory, and CDR.

- Construct validity was confirmed through academic peer review and practitioner feedback.

- Internal consistency metrics ranged from Cronbach’s α = 0.89–0.93.

- Pilot Study Highlights (n = 34):

- Participants were employees of a major Nordic savings and insurance institution.

- The sample reflected diversity across gender, age, and organizational levels.

- R = 0.773, R2 = 0.471, F(3, 30) = 6.5, p < 0.05.

| Characteristic | Distribution (%) | ||||

| Gender | Female: 58.8; Male: 35.3; Other/NA: 5.9 | ||||

| Age Group | 25–34: 17.6; 35–44: 26.5; 45–54: 35.3; 55+: 20.6 | ||||

| Organizational Level | Entry: 14.7; Senior: 38.2; Manager: 29.4; Executive: 11.8; NA: 5.9 | ||||

| Survey Results: | |||||

| Dimension | Mean Score | Standard Deviation | Interpretation | ||

| Total Defence Integration | 3.44 | 0.87 | Moderate organizational integration | ||

| Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) | 4.14 | 0.68 | High level of strategic inclusivity | ||

| Organizational Learning | 3.65 | 0.80 | Strong emphasis on continuous improvement | ||

| Perceived Utility | 3.20 | 0.99 | Moderate perceived practical application | ||

| Regression Analysis Results: | |||||

| Predictor Variable | B | SE | Beta | t-value | p-value |

| CDR | 0.735 | 0.289 | 0.577 | 2.547 | 0.019 |

| Learning | 0.011 | 0.239 | 0.010 | 0.047 | 0.963 |

| Utility | 0.196 | 0.184 | 0.208 | 1.062 | 0.300 |

Appendix B.2. Longitudinal Research on DLM (2020–2025)

- Research Design:

- Mixed methods data from 72 C-level executives across private and public sectors in Norway.

- Integrated into leadership education programs at the University of South-Eastern Norway (BARLED and ESB100E).

- Empirical input from executive interviews, observation in leadership forums, course-based reflections, and strategic foresight workshops.

- Validated Capabilities:

- Digital imagination and strategic foresight.

- Participatory leadership and employeeship.

- Learning culture and inclusive decision-making.

| Source | Method | Sample Size/Context |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Interviews | Semi-structured | 72 C-level executives (private and public sectors, Norway) |

| ESB100E Educational Pilot | Exams and reflections | 15 undergraduate students (USN School of Business) |

| BARLED Course Implementation | Strategy assignments | 40 adult learners in professional leadership development |

| Cross-sector Workshops | Observation and notes | 14 strategic foresight and AI ethics workshops |

| 1 | The number of community-based co-creation programs reflects the extent to which an organization is engaged with local communities in the creation and implementation of sustainability initiatives. These programs foster collaboration between the organization and external stakeholders, driving inclusive innovation and promoting social equity. This KPI is crucial for measuring the organization’s impact on social sustainability and the success of its community partnerships. |

References

- Ali, W., Mahmood, Z., Wilson, J., & Ismail, H. (2024). The impact of sustainability governance attributes on comprehensive CSR reporting: A developing country setting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(3), 1802–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim-Maia, A. T., Anguelovski, I., Chu, E., & Connolly, J. (2022). Intersectional climate justice: A conceptual pathway for bridging adaptation planning, transformative action, and social equity. Urban Climate, 41, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim-Maia, F., Sultana, F., & Mikulewicz, M. (2022). Addressing the challenges of marginalized communities: Intersectionality and climate justice. Environmental Justice, 15(1), 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anane-Simon, R., & Atiku, S. O. (2023). Inclusive leadership for sustainable development in times of change. Routledge Open Research, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P. D., & Silvast, A. (2023). Experts, stakeholders, technocracy, and technoeconomic input into energy scenarios. Futures, 146, 103271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeske, J. (2023). Leadership towards sustainability: A review of sustainable, sustainability, and environmental leadership. Sustainability, 15(16), 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P., & Meyer, J. W. (2017). Institutional theories and the new institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E. Meyer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational institutionalism (2nd ed., pp. 269–298). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau, J. J., Stern, M. J., Pownall, M., & Hansen, L. J. (2024). Understanding how justice is considered in climate adaptation approaches: A qualitative review of climate adaptation plans. Local Environment, 29(12), 1644–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, R. D. (2005). Environmental justice in the 21st century. In R. D. Bullard (Ed.), The quest for environmental justice: Human rights and the politics of pollution (pp. 19–42). Sierra Club Books. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cuhadar, S., & Rudnák, I. (2022). Literature review: Sustainable leadership. Studia Mundi—Economica, 9(3), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasinapa, M. B. (2024). The integration of sustainability and ESG accounting into corporate reporting practices. Advances in Applied Accounting Research, 2(1), 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demneh, M. T., Zackery, A., & Nouraei, A. (2023). Using corporate foresight to enhance strategic management practices. European Journal of Futures Research, 11(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V. D., & Dumitru, M. (2023). Does corporate governance improve integrated reporting quality? A meta-analytical investigation. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(6), 1846–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitrem, A., Meidell, A., & Modell, S. (2024). The use of institutional theory in social and environmental accounting research: A critical review. Accounting and Business Research, 54(7), 775–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekechukwu, D. E., & Simpa, P. (2024). The intersection of renewable energy and environmental health: Advancements in sustainable solutions. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6(6), 1103–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerland, B. S. (2019). Corporate diversity responsibility: Building better businesses. In Understanding society: A woman’s world (pp. 16–17). Ipsos MORI. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2019-08/ipsos-understanding-society-a-womans-world.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fagerland, B. S., & Behdani, B. (2025, June 16–18). Corporate diversity responsibility (CDR): Driving organizational equity and sustainable growth. Abstract submitted for presentation at the PEDAGOGY 2025 Conference, Ghent, Belgium. Available online: https://amps-research.com/conference/pedagogy-2025/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fagerland, B. S., & Bergh, H. (2025). Integrating sustainable leadership into police education: A transformative framework for leadership development in higher education. Athens Journal of Education, 12, 1–29. Available online: https://www.athensjournals.gr/aje/forthcoming (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fagerland, B. S., Bergh, H., & Fjuk, A. (2025). Resilient Leadership for Educational Innovation: Integrating Dynamic Capabilities for Transformative Teaching. Available online: https://amps-research.com/conference/prague-research-teaching/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fagerland, B. S., & Bleveans, L. (2024, September 25). Corporate diversity responsibility and its role in transforming governance. Statement at SHEconomy Summit, Google headquarters, Silicon Valley, Mountain View, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerland, B. S., & Drejer, A. (2018). Introducing the corporate diversity responsibility (CDR) concept. European Journal of Management, 18(2), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerland, B. S., & Fjuk, A. (2024). Compendium for sustainable leadership (course code: BARLED) and strategic sustainability (course code: ESB100E). University of South-Eastern Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerland, B. S., & Fjuk, A. (2025a, June 30–July 2). The Dynamic Leadership Model (DLM): A future-ready framework for AI-driven educational leadership and institutional resilience [Paper presentation]. EDULEARN25 Conference, Palma, Spain. Available online: https://iated.org/edulearn/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fagerland, B. S., & Fjuk, A. (2025b, June 30–July 2). The Dynamic Leadership Model (DLM) and employeeship: A catalyst for inclusive and resilient educational leadership in the AI era [Paper presentation]. EDULEARN25 Conference, Palma, Spain. Available online: https://iated.org/edulearn/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fagerland, B. S., & Rambøl, I. B. (2015). SHEconomy—It’s your business! (1st ed.) Fagbokforlaget. ISBN 9788245015768. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerland, B. S., & Sørensen, J. L. (2025). Corporate Diversity Responsibility as Resilience Strategy: A Governance Model for Total Defence Implementation. Unpublished manuscript submitted to Administrative Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Friske, M., Zhang, L., & Andersson, T. (2023). Institutional factors influencing sustainability reporting: Evidence from state-owned enterprises. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 14(5), 758–774. [Google Scholar]

- Galleli, A., Manno, R., & Zanchettin, G. (2023). The role of equity-integrated reporting in fostering sustainability and trust. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 14(1), 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, A., Siddiki, S., Mesdaghi, B., Bosch, M., & Abebe, Y. A. (2024). Understanding institutional compliance in flood risk management: A network analysis approach highlighting the significance of institutional linkages and context. International Journal of the Commons, 18(1), 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, H., Clouse, M., & Xu, T. (2023). Strategic foresight for companies. Corporate Board: Role, Duties and Composition, 19(2), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterman, A. S. (2022). Corporate Sustainability. (SSRN Working Paper Series). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriette, E., Feki, M., & Boughzala, I. (2015, October 3–5). The shape of digital transformation: A systematic literature review [Paper presentation]. MCIS 2015 Proceedings, Samos, Greece. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2015/10 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Hosan, S., Sen, K. K., Rahman, M. M., Chapman, A. J., Karmaker, S. C., Alam, M. J., & Saha, B. B. (2024). Energy innovation funding and social equity: Mediating role of just energy transition. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 197, 114405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, G., & Storm, L. (2019). Regenerative Leadership: The DNA of Life-Affirming 21st Century Organizations. Wordzworth Publishing. ISBN 9781783241194. [Google Scholar]

- Idries, A., Krogstie, J., & Rajasekharan, J. (2022). Dynamic capabilities in electrical energy digitalization: A case from the Norwegian ecosystem. Energies, 15(22), 8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2014a). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2014b). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. (2019). Understanding society: A woman’s world. Ipsos MORI. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2019-08/ipsos-understanding-society-a-womans-world.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Javed, M. S., Fossheim, K., Velasco-Herrejón, P., Koop, N. E., Guzik, M. N., Samuelson, C. D., Seibt, B., & Zeyringer, M. (2025). Beyond costs: Mapping Norwegian youth preferences for a more inclusive energy transition. arXiv, arXiv:2502.19974. [Google Scholar]

- Kinol, A., Miller, E., Axtell, H., Hirschfeld, I., Leggett, S., Si, Y., & Stephens, J. C. (2023). Climate justice in higher education: A proposed paradigm shift towards a transformative role for colleges and universities. Climatic Change, 176, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A., & Robele, S. (2024). Anticipatory development foresight: An approach for international and multilateral organizations. Development Policy Review, 42(3), e12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, E. (2023). Likestilling er en del av Forsvarets samfunnsoppdrag [Equality is part of the Armed Forces’ societal mission]. Forsvarets Forum. Available online: https://www.forsvaretsforum.no/8-mars-eirik-kristoffersen-kvinner/likestilling-er-en-del-av-forsvarets-samfunnsoppdrag/367991 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Leonidou, L. C., Theodosiou, M., Nilssen, F., Eteokleous, P., & Voskou, A. (2024). Evaluating MNEs’ role in implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: The importance of innovative partnerships. International Business Review, 33(3), 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. (2022). Sustainable leadership: A literature review and prospects for future research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1045570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailani, D., Hulu, M. Z. T., Simamora, M. R., & Kesuma, S. A. (2024). Resource-Based View Theory to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage of the firm: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Studies, 4(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. (2020a). Delivering on purpose: 2020 social responsibility report. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/about%20us/social%20responsibility/2020%20social%20responsibility%20report/mckinsey-social-responsibility-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- McKinsey & Company. (2020b). Diversity wins: How inclusion matters. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Mikulewicz, M., Caretta, M. A., Sultana, F., & Crawford, N. J. W. (2023). Intersectionality & climate justice: A call for synergy in climate change scholarship. Environmental Politics, 32(7), 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloud, T. (2024). Corporate governance and CSR disclosure: Evidence from French listed companies. Global Finance Journal, 59(C), 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A., & Shaw, R. (2023). Systemic risk from a disaster management perspective: A review of current research. Environmental Science & Policy, 140, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthusamy Thirumalai, A., Hariharan, R., Yuvaraj, T., & Prabaharan, N. (2024). Optimizing distribution system resilience in extreme weather using prosumer-centric microgrids with integrated distributed energy resources and battery electric vehicles. Sustainability, 16(6), 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysore, S. (2024). Microgrids and Distributed Energy Resources (DERs). The Review of Contemporary Scientific and Academic Studies, 4(3), 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olutimehin, D. O., Ofodile, O. C., Ejibe, I., Odunaiya, O. G., & Soyombo, O. T. (2024). Innovations in business diversity and inclusion: Case studies from the renewable energy sector. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 6(3), 890–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, O. M., Dragomir, V. D., & Hao, N. (2023). Company-level factors of non-financial reporting quality under a mandatory regime: A systematic review of empirical evidence in the European Union. Sustainability, 15(23), 16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J., Amorim, M., Melão, N., & Matos, P. (2018). Digital transformation: A literature review and guidelines for future research. In Á. Rocha, H. Adeli, L. P. Reis, & S. Costanzo (Eds.), Trends and advances in information systems and technologies. Advances in intelligent systems and computing (Vol. 745, pp. 411–421). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V., García-del-Amo, D., Porcuna-Ferrer, A., Schlingmann, A., Abazeri, M., Attoh, E. M. N. A. N., Vieira da Cunha Ávila, J., Ayanlade, A., Babai, D., Carmona, R., Caviedes, J., Chah, J., Chakauya, R., Cuní-Sanchez, A., Ferníndez-Llamazares, A., Galappaththi, E. K., Gerkey, D., Graham, S., Huanca, T., … LICCI Consortium. (2024). Local studies provide a global perspective of the impacts of climate change on Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Sustainable Earth Reviews, 7(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lankao, P., Rosner, N., Brandtner, C., Rea, C., Mejia Montero, A., Pilo, F., Dokshin, F., Castan-Broto, V., Burch, S., & Schnur, S. (2023). A framework to centre justice in energy transition innovations. Nature Energy, 8, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S., Tandukar, S., & Bhattarai, U. (2022). Gender, climate change adaptation, and cultural sustainability: Insights from Bangladesh. Frontiers in Climate, 4, 841488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Raziq, M. M. (2024). Sustainability leadership: An integrative review and conceptual synthesis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(4), 2849–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbîrcea, I.-A. (2023). Theoretical research into leadership for sustainability. Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, 19(1), 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., & Patel, M. (2023). A review on environmental impacts of renewable energy for sustainable development. Renewable Energy and Environmental Sustainability, 8(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F. (2021). Political ecology II: Conjunctures, crises, and critical publics. Progress in Human Geography, 45(6), 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F. (2022). Critical climate justice. The Geographical Journal, 188(1), 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K. (2023). Centering equity and justice in participatory climate action planning: Guidance for urban governance actors. Planning Theory & Practice, 24(2), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Korea Times. ((2023a,, November 2)). Women’s participation in leadership key to bolstering economy: UN. The Korea Times. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/biz/2025/02/602_362446.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- The Korea Times. ((2023b,, December 5)). Female leadership not just diversity issue, but survival necessity. The Korea Times. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/economy/20231205/female-leadership-not-just-diversity-issue-but-survival-necessity (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2021). UN Climate Change Annual Report 2021. UNFCCC Secretariat. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/UNFCCC_Annual_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- UN Women. (2023a). 1st Seoul Gender Equality Dialogue discusses how to break gender barriers in key industries. UN Women Asia and the Pacific. Available online: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/stories/news/2023/12/how-to-break-gender-barriers-in-key-industries (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- UN Women. (2023b). Breaking gender barrier for a better future of key industries: Event overview. UN Women Asia and the Pacific. Available online: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/news-and-events/events/2023/10/breaking-gender-barrier-for-a-better-future-of-key-industries (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- UN Women. (2023c). UN Women Centre of Excellence marks its first anniversary during the 1st Annual Seoul Gender Equality Dialogue. UN Women Asia and the Pacific. Available online: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/stories/press-release/2023/11/un-women-centre-of-excellence-marks-its-first-anniversary (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- UN Women. (2023d). Women leaders who broke the glass ceiling in under-represented sectors. UN Women Asia and the Pacific. Available online: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/stories/news/2023/12/you-can-become-whatever-you-want-to-be (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Vaccaro, V., Fagerland, B. S., & Cohn, D. Y. (2019). A SHEconomy Management 3.0 Benefit Model & Framework of Gender Diversity Leadership for Greater Innovation, Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Financial Performance. European Journal of Management, 19(1), 39–51. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331426063_A_SHEconomy_Management_30_Benefit_Model_Framework_of_Gender_Diversity_Leadership_for_Greater_Innovation_Corporate_Social_Responsibility_and_Firm_Financial_Performance (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Versey, H. S. (2021). Missing Pieces in the Discussion on Climate Change and Risk: Intersectionality and Compounded Vulnerability. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(1), 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windfeldt, L., & Barnard, H. (2024). Innovations in business diversity and inclusion: Case studies from the renewable energy sector. ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379393527_INNOVATIONS_IN_BUSINESS_DIVERSITY_AND_INCLUSION_CASE_STUDIES_FROM_THE_RENEWABLE_ENERGY_SECTOR (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Wright, C. E. F., Cortese, C. L., Al Mamun, A., & Ali, S. (2023). The Whiteboard: Decoupling of ethnic and gender diversity reporting and practice in corporate Australia. Australian Journal of Management, 49(1), 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., Kühner, C., Katz, I. M., & Rudolph, C. W. (2024). Leadership and environmental sustainability: An integrative conceptual model of multilevel antecedents and consequences of leader green behavior. Group & Organization Management, 49(2), 365–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampone, G., García-Sánchez, I. M., & Sannino, G. (2023). Imitation is the sincerest form of institutionalization: Understanding the effects of imitation and competitive pressures on the reporting of sustainable development goals in an international context. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(7), 4119–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyringer, M., Velasco-Herrejon, P., Koop, N. E., Javed, M. S., & Seibt, B. (2024). Who cares about Norway’s energy transition? Energy Policy, 186, 113141. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. (2023). Coercive isomorphism in urban climate adaptation: Analyzing the role of regulatory frameworks. Urban Climate, 46, 101638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Yu, Y., & Wang, Y. (2023). The impact of carbon pricing on firm competitiveness: Evidence from China’s pilot carbon markets. Energy Policy, 179, 113580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Conceptual Focus | Key Contributions to Sustainability Governance | Selected References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Sustainability | Renewable energy, climate justice, and resilience planning | Promotes equitable energy access, decentralized systems, and anticipatory adaptation strategies | IPCC (2014a, 2014b); Zhang (2023); Romero-Lankao et al. (2023); Hosan et al. (2024) |

| Social Sustainability | Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR), systemic equity, and intersectionality | Institutionalizes equity in leadership, strategy, and governance; reinforces inclusive legitimacy | Fagerland (2019); Fagerland and Drejer (2018); A. T. Amorim-Maia et al. (2022); Crenshaw (1989); Vaccaro et al. (2019) |

| Governance and Policy Integration | ESG integration, policy coherence, and legitimacy-based governance | Aligns corporate and public governance with SDGs, CSRD, and evolving ESG standards | DiMaggio and Powell (1983); Eitrem et al. (2024); Dragomir and Dumitru (2023); Leonidou et al. (2024) |

| Collaborative Partnerships | Cross-sector alliances, inclusive innovation, and knowledge networks | Facilitates multi-actor cooperation and platform thinking for scalable impact | Brousseau et al. (2024); Friske et al. (2023); Kinol et al. (2023); Swanson (2023) |

| Implementation and Monitoring | Metrics, KPIs, continuous learning, and adaptive decision-making | Enables iterative governance cycles, accountability mechanisms, and organizational learning | Teece (2007); Galleli et al. (2023); Krishnan and Robele (2024); Eitrem et al. (2024) |

| IMSD Pillar | Theoretical Foundation | Operational Focus | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Sustainability | Resource-Based View (RBV) (Barney, 1991; Mailani et al., 2024) | Renewable energy innovation and climate adaptation | Smart grid investment, decentralized energy infrastructure, equitable access policies (IPCC, 2014a, 2014b; Hosan et al., 2024; Sharma & Patel, 2023; Zhou et al., 2023) |

| Social Sustainability and CDR | Intersectionality Theory (Crenshaw, 1989; A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022) | Systemic equity and inclusive governance | Integrating marginalized voices in climate adaptation and decision-making (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Vaccaro et al., 2019; Mikulewicz et al., 2023; Swanson, 2023) |

| Governance and Policy Integration | Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Bromley & Meyer, 2017) | ESG alignment, policy compliance, legitimacy | Regulatory compliance, stakeholder legitimacy, inclusive ESG reporting (Eitrem et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Leonidou et al., 2024; Zampone et al., 2023) |

| Collaborative Partnerships | Institutional and Network Theory (Greenwood et al., 2002) | Cross-sector alignment and co-production | Public–private partnerships and knowledge-sharing networks (Brousseau et al., 2024; Friske et al., 2023; Kinol et al., 2023; Leonidou et al., 2024) |

| Implementation and Monitoring | Dynamic Capabilities Theory and Dynamic Leadership Model (DLM) (Teece, 2007; Fagerland & Fjuk, 2025a, 2025b) | Learning, adaptive governance, resilience building | Application of DLM’s five capabilities: digital imagination, strategic foresight, soft skills, competence development, and learning culture (Galleli et al., 2023; Krishnan & Robele, 2024; Idries et al., 2022; Cuhadar & Rudnák, 2022) |

| IMSD Pillar | Theoretical Foundation | Operational Focus | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Sustainability | Resource-Based View (RBV) (Barney, 1991; Mailani et al., 2024) | Renewable energy innovation and climate adaptation | Smart grid investment, decentralized energy infrastructure, equitable access policies (IPCC, 2014a, 2014b; Hosan et al., 2024; Sharma & Patel, 2023; Zhou et al., 2023) |

| Social Sustainability and CDR | Intersectionality Theory (Crenshaw, 1989; A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022) | Systemic equity and inclusive governance | Integrating marginalized voices in climate adaptation and decision-making (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Vaccaro et al., 2019; Mikulewicz et al., 2023; Swanson, 2023) |

| Governance and Policy Integration | Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Bromley & Meyer, 2017) | ESG alignment, policy compliance, legitimacy | Regulatory compliance, stakeholder legitimacy, inclusive ESG reporting (Eitrem et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Leonidou et al., 2024; Zampone et al., 2023) |

| Collaborative Partnerships | Institutional and Network Theory (Greenwood et al., 2002) | Cross-sector alignment and co-production | Public–private partnerships and knowledge-sharing networks (Brousseau et al., 2024; Friske et al., 2023; Kinol et al., 2023; Leonidou et al., 2024) |

| Implementation and Monitoring | Dynamic Capabilities Theory and Dynamic Leadership Model (DLM) (Teece, 2007; Fagerland & Fjuk, 2025a, 2025b) | Learning, adaptive governance, resilience building | Application of DLM’s five capabilities: digital imagination, strategic foresight, soft skills, competence development, and learning culture (Galleli et al., 2023; Krishnan & Robele, 2024; Idries et al., 2022; Cuhadar & Rudnák, 2022) |

| Theory | Core Focus | Application in IMSD |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Theory | Legitimacy, governance adaptation | Embeds Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as a normative standard within organizations, aligning Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices with evolving stakeholder expectations and regulatory frameworks, following principles of institutional isomorphism and legitimacy pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Eitrem et al., 2024; Friske et al., 2023). |

| Resource-Based View | Strategic resources and competitive edge | Posits diversity as a valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resource that enhances organizational innovation, agility, and ESG performance, thereby supporting sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Mailani et al., 2024). |

| Intersectionality Theory | Equity and inclusive design | Centers justice and inclusion in governance by integrating intersectional perspectives to ensure participatory adaptation processes and accountable inclusion of marginalized groups in sustainability initiatives (Crenshaw, 1989; A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Mikulewicz et al., 2023). |

| Strategic Impact Dimension | Description | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Legitimacy | Positionalizes DEIB som en strukturell styringsimperativ som øker tillit og legitimitet på tvers av interessentgrupper, med vekt på rettferdighet i klima- og tilpasningsplaner (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Brousseau et al., 2024; UN Women, 2023a). | A. T. Amorim-Maia et al. (2022); Brousseau et al. (2024); UN Women (2023a) |

| ESG Integration | Integrerer DEIB i ESG-arkitektur og sikrer samsvar med CSRD, GRI og TCFD-standarder for systematisk bærekraftsledelse (Ali et al., 2024; Galleli et al., 2023b; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023). | Ali et al. (2024); Galleli et al. (2023b); Dragomir and Dumitru (2023) |

| Strategic Foresight | Fremmer anticipatorisk kapasitet gjennom interseksjonell analyse for langsiktig planlegging og risikohåndtering (Demneh et al., 2023; Krishnan & Robele, 2024; Grove et al., 2023). | Demneh et al. (2023); Krishnan and Robele (2024); Grove et al. (2023) |

| Inclusive Innovation Ecosystems | Aktiverer inkluderende FoU, produktinnovasjon og styringsdesign gjennom mangfoldsledet kunnskapsintegrasjon (Hutchins & Storm, 2019; Vaccaro et al., 2019; Fagerland & Behdani, 2025). | Hutchins and Storm (2019); Vaccaro et al. (2019); Fagerland and Behdani (2025) |

| Global Strategic Alignment | Justerer organisasjonsstrategi med FNs bærekraftsmål 5, 7, 10 og 13 via DEIB-forankrede styringsmodeller som fremmer sosial rettferdighet og klimahandling globalt (Leonidou et al., 2024; Sharma & Patel, 2023; Zampone et al., 2023). | Leonidou et al. (2024); Sharma and Patel (2023); Zampone et al. (2023) |

| Sector/Setting | IMSD Entry Point | Stakeholders Involved | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Sector (Municipal) | Governance and Policy Integration | City councils, planning agencies | Equitable climate adaptation policies og ESG compliance, styrket gjennom institusjonell rettferdighet og inkludering (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Brousseau et al., 2024; UN Women, 2023a). |

| Energy and Infrastructure | Climate Sustainability | Grid operators, regulators, NGOs | Smart grid implementering og inkluderende energitilgang, støttet av systematisk bærekraft og rettferdighetsrammer (Ali et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Sharma & Patel, 2023). |

| SMEs and Startups | Social Sustainability and CDR | Founders, HR leads, incubators | Inkluderende ansettelse, DEIB-målinger og sosial legitimitet som drivere for bærekraftig vekst og innovasjon (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Vaccaro et al., 2019; Sajjad et al., 2024). |

| Higher Education | Collaborative Partnerships | University boards, student orgs | Co-governance modeller og inkluderende innovasjonshuber som fremmer tverrfaglig samarbeid og bærekraftig lederskap (Fagerland & Fjuk, 2024; Kinol et al., 2023; Sbîrcea, 2023). |

| Multinational Corporations | Implementation and Monitoring | Sustainability Officers, strategy leads | KPI-rammeverk for robusthet og mangfold, integrert i global ESG-praksis og SDG-tilpasning (Leonidou et al., 2024; Galleli et al., 2023; Zampone et al., 2023). |

| Governance Level | CDR Integration Lever | Strategic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Leadership | Inclusive leadership pipelines and equity oversight | Enhances institutional legitimacy and long-term foresight through inclusive leadership for sustainable development (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Anane-Simon & Atiku, 2023; Bromley & Meyer, 2017). |

| Middle Management | ESG-aligned DEIB strategies and inclusive monitoring frameworks | Promotes operational sustainability and ethical decision-making by integrating ESG frameworks and diversity targets (Ali et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Galleli et al., 2023). |

| Frontline Staff | Equitable hiring, inclusive training, and participatory culture | Increases employee engagement and innovation in problem-solving through inclusive practices and active participation (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Vaccaro et al., 2019; Sajjad et al., 2024). |

| Cross-Sectoral | Multi-actor collaboration in policy and supply chain innovation | Improves adaptive capacity, stakeholder trust, and co-produced governance through cross-sector collaboration (Brousseau et al., 2024; Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Romero-Lankao et al., 2023). |

| Category | Specific KPIs | Rationale and Source |

|---|---|---|

| Workforce Equity | - % of leadership roles held by underrepresented groups - Gender/race pay equity index | Tracks progress in DEIB representation and internal fairness (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; UN Women, 2023d) |

| Inclusive Culture | - Employee inclusion & belonging survey score - DEIB grievance resolution rate | Measures internal culture and psychological safety (McKinsey & Company, 2020a; Swanson, 2023) |

| Transparency & Reporting | - Intersectional ESG KPI disclosure - CSRD/GRI compliance for DEIB metrics | Supports accountability and compliance (Ali et al., 2024) |

| Community Engagement | - #1 of community-based co-creation programs - Local inclusion partnership outcomes | Links corporate DEIB to social impact (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Olutimehin et al., 2024) |

| Organizational Learning | - DEIB training hours per employee - % of leaders completing inclusive leadership development | Ensures capability-building and organizational adaptability (Boeske, 2023; Hutchins & Storm, 2019) |

| Strategic Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|

| Develop Inclusive Leadership Frameworks | Enhance agility, creativity, and adaptive decision-making (Anane-Simon & Atiku, 2023; Liao, 2022). |

| Embed CDR in Governance Structures | Institutionalizes intersectional inclusivity for long-term resilience (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025; Fagerland & Drejer, 2018). |

| Strengthening ESG Reporting and Equity Metrics | Build trust and ensures alignment with global compliance norms (Ali et al., 2024; Galleli et al., 2023a). |

| Invest in Smart Renewable Energy and Energy Equity | Accelerates transition and addresses structural disparities in energy access (Roy et al., 2022; Sharma & Patel, 2023; Olutimehin et al., 2024). |

| Foster Cross-Sector Sustainability Alliances | Expands capacity for systemic impact through multistakeholder engagement (Leonidou et al., 2024). |

| IMSD Contribution | ESG Dimension | SDG Alignment | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equitable access to renewable energy | Environmental | SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | Expands decentralized systems and promotes energy justice, supporting just energy transitions and inclusive access (Ekechukwu & Simpa, 2024; Hosan et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025). |

| Institutionalizing Corporate Diversity | Social | SDG 10: Reduced Inequality | Embeds equity in governance frameworks, fostering inclusive leadership and reducing social inequalities (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Vaccaro et al., 2019). |

| Intersectional climate adaptation | Environmental and Social | SDG 13: Climate Action | Enhances resilience through tailored, intersectional climate adaptation strategies addressing social equity (A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022; Mikulewicz et al., 2023; Roy et al., 2022). |

| Inclusive and transparent governance | Governance | Cross-cutting | Builds stakeholder trust and aligns with ESG reporting standards, promoting transparency and accountability (Ali et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Galleli et al., 2023). |

| Adaptive monitoring and digital foresight | Governance | SDG 13 and SDG 10 | Enables responsive, data-driven sustainability planning through strategic foresight and digital tools (Demneh et al., 2023; Grove et al., 2023; Fagerland & Fjuk, 2025a). |

| Dimension | IMSD Summary |

|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundations | Synthesizes Institutional Theory, Resource-Based View (RBV), Intersectionality Theory, and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (Barney, 1991; Bromley & Meyer, 2017; Crenshaw, 1989; Teece et al., 1997). |

| Strategic Focus | Integrates equity, diversity, climate resilience, and inclusive governance into a unified strategy (Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Sajjad et al., 2024; Swanson, 2023). |

| Operational Pillars | Five pillars: Climate Sustainability, Social Sustainability (CDR), Governance Integration, Partnerships, Monitoring (Fagerland, 2019; Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Ghorbani et al., 2024). |

| Key Contributions | Aligns with SDGs 7, 10, 13 and ESG frameworks (CSRD, GRI, TCFD); embeds CDR as a strategic asset (Dasinapa, 2024; Leonidou et al., 2024; Vaccaro et al., 2019). |

| Organizational Implications | Supports inclusive strategy, enhanced ESG compliance, and stakeholder trust through adaptive governance (Ali et al., 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Eitrem et al., 2024). |

| Managerial Implications | Equips leaders with intersectional foresight, digital agility, and inclusive leadership capabilities (Anane-Simon & Atiku, 2023; Fagerland & Fjuk, 2025a; Grove et al., 2023). |

| Research Directions | Calls for longitudinal studies, sector-specific case analysis, digital foresight applications, and KPI development (Demneh et al., 2023; Fagerland & Fjuk, 2025b; Mailani et al., 2024). |

| CDR Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Normative Commitment | Positions DEIB as a moral, strategic, and institutional imperative across governance contexts (Anane-Simon & Atiku, 2023; Sajjad et al., 2024; Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Bromley & Meyer, 2017) |

| Structural Integration | Embeds CDR within ESG frameworks, policy architecture, leadership pipelines, and governance systems (Dasinapa, 2024; Dragomir & Dumitru, 2023; Fagerland, 2019; Miloud, 2024; Radu et al., 2023) |

| Performance Indicators | Utilizes intersectional KPIs spanning innovation, inclusion, risk reduction, and transparency (Ali et al., 2024; Galleli et al., 2023; Wright et al., 2023; Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Vaccaro et al., 2019) |

| Strategic Partnerships | Anchored in cross-sectoral collaboration with industry, defense, academia, and diplomacy (Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Olutimehin et al., 2024; Leonidou et al., 2024; Grove et al., 2023) |

| Educational Anchoring | Integrated into academic curricula and executive education across multiple institutional platforms (Fagerland & Fjuk, 2024; Fagerland et al., 2025; Sbîrcea, 2023; Liao, 2022) |

| Political Endorsement | Presented to UN Women, Nordic governments, and international governance forums (UN Women, 2023a, 2023b; Kristoffersen, 2023; The Korea Times, 2023a, 2023b; Fagerland & Bleveans, 2024) |

| Research Foundation | Originated by Fagerland and Rambøl (2015); expanded via SHEconomy® and validated through empirical studies (Fagerland & Rambøl, 2015; Fagerland & Drejer, 2018; Fagerland, 2019; Fagerland & Sørensen, 2025; Mikulewicz et al., 2023) |

| Criteria | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Equity Integration | IMSD: Structurally embedded (CDR-based) ESG-Only Models: Often implicit or compliance-led CSR Models: Generally aspirational | Fagerland and Drejer (2018); Ali et al. (2024); Dragomir and Dumitru (2023); Sajjad et al. (2024); Wright et al. (2023) |

| Leadership Philosophy | IMSD: Distributed & regenerative ESG-Only Models: Executive-centered CSR Models: Often hierarchical | Boeske (2023); Hutchins and Storm (2019); Anane-Simon and Atiku (2023); Sbîrcea (2023); Fagerland and Fjuk (2025a, 2025b) |

| Adaptability (Dynamic Capabilities) | IMSD: Core design logic ESG-Only Models: Limited CSR Models: Variable | Teece (2007); Teece et al. (1997); Fagerland et al. (2025); Idries et al. (2022); Mitra and Shaw (2023) |

| SDG Alignment | IMSD: SDGs 7, 10, 13 explicitly operationalized ESG-Only Models: Referenced but not internalized CSR Models: Weak or symbolic | Zampone et al. (2023); Leonidou et al. (2024); McKinsey and Company (2020a, 2020b); Fagerland and Sørensen (2025) |

| Reporting & Foresight Capacity | IMSD: AI-ready, intersectional KPIs ESG-Only Models: Compliance-driven CSR Models: Retrospective & qualitative | Dasinapa (2024); Demneh et al. (2023); Grove et al. (2023); Radu et al. (2023) |

| IMSD Pillar | KPI Category | Specific KPIs | Description and Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Sustainability | Environmental Impact | - Carbon footprint reduction - Renewable energy share (%) - Climate risk mitigation actions | Reflects dynamic capabilities in climate resilience and emissions reduction (IPCC, 2014a; Sharma & Patel, 2023). |

| Social Sustainability (CDR) | Equity & Inclusion | - Workforce diversity metrics (intersectional) - Inclusive leadership representation - Community engagement indices | Tracks systemic equity and social justice (Fagerland & Behdani, 2025; A. T. Amorim-Maia et al., 2022). |

| Governance Integration | Transparency & Accountability | - ESG integrated reporting completeness - Intersectional KPI disclosure - Compliance with CSRD and GRI standards | Evaluates integration of equity in transparent governance (Ali et al., 2024) |

| Collaborative Partnerships | Network and Innovation | - Number of cross-sector partnerships - Joint sustainability initiatives - Innovation outputs | Measures stakeholder collaboration for scalable innovation (Leonidou et al., 2024; Wright et al., 2023). |

| Implementation & Monitoring | Adaptive Capacity & Foresight | - Frequency of monitoring cycles - Use of AI-enabled data analytics - Policy adjustment cycles | Demonstrates institutional agility and foresight capacity (Teece, 2007; Demneh et al., 2023). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fagerland, B.S.; Bleveans, L. Strategic Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as a Catalyst for Sustainable Governance: Integrating Equity, Climate Resilience, and Renewable Energy in the IMSD Framework. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060213

Fagerland BS, Bleveans L. Strategic Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as a Catalyst for Sustainable Governance: Integrating Equity, Climate Resilience, and Renewable Energy in the IMSD Framework. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060213

Chicago/Turabian StyleFagerland, Benja Stig, and Lincoln Bleveans. 2025. "Strategic Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as a Catalyst for Sustainable Governance: Integrating Equity, Climate Resilience, and Renewable Energy in the IMSD Framework" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060213

APA StyleFagerland, B. S., & Bleveans, L. (2025). Strategic Corporate Diversity Responsibility (CDR) as a Catalyst for Sustainable Governance: Integrating Equity, Climate Resilience, and Renewable Energy in the IMSD Framework. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060213