Abstract

In healthcare, there is growing awareness of the potential harm that disciplinary processes can have on employees, service delivery, and organizational culture. However, little attention has been given to the impact on those responsible for conducting these investigations. This study examines investigator harm through a cross-sectional survey, simultaneously collecting qualitative and quantitative data from 71 participants across 10 NHS Wales organizations. The findings indicate that investigators experience harm when conducting employee investigations. While those with more experience perceive themselves as better prepared to follow the formal steps of the disciplinary policy and process, their ability to prevent harm to themselves or others remains unchanged. Additionally, more experienced investigators are not more aware of their organization’s well-being priorities or strategies for mitigating harm. These findings highlight the need for greater support for investigators, including coaching and post-investigation debriefing. Training should raise awareness of the impact of employee investigations on all stakeholders and the importance of applying disciplinary policy and processes empathically. Finally, policies and processes should acknowledge the harm they may cause and explicitly provide strategies for harm reduction, such as treating formal investigations as a measure of ‘last resort’.

1. Introduction

An employee investigation is a structured process that an employer uses to assess an employee’s conduct or performance (ACAS, 2024). This may involve allegations of misconduct, inadequate performance, or breaches of organizational policy. As a critical component of an organization’s disciplinary policy and process, the purpose of an employee investigation is to gather evidence impartially from all relevant parties and determine whether the claims against the employee are substantiated. This approach enables the employer to make an informed decision regarding the appropriate course of action to take (ACAS, 2020).

Particularly within healthcare, there has been growing recognition of the potential harm that investigations, such as complaint procedures or fitness-to-practice investigations, can inflict on individuals subjected to them (Bourne et al., 2015, 2017; Bourne, 2017; Maben et al., 2021). In the context of disciplinary investigations, research has highlighted not only the distress, anxiety, and concern commonly associated with employee investigations, but also the potential for reputational damage (Gandhi et al., 2018), more significant psychological harm (Maben et al., 2021; Hussain, 2022; Neal et al., 2023; Morrison et al., 2024), and financial hardship (A Better NHS, 2024). Recent findings suggest that health and social care employers provide inadequate support to employees undergoing regulatory proceedings, leaving them even more vulnerable to stress and uncertainty. The level of support often depends on the personal experience of senior staff, rather than structured organizational policies (Wallace & Greenfield, 2022). This lack of institutional support exacerbates the potentially harmful effects of investigations, reinforcing concerns about their negative consequences for individuals, including a disproportionate impact on employees from ethnic minority groups (Archibong et al., 2019). Furthermore, it is increasingly acknowledged that a poorly administered application of disciplinary policies and processes, or the overuse of investigations, can harm organizations by impairing psychological safety, diminishing trust in leadership, and creating negative organizational cultures (Cooper et al., 2024a), thereby impairing patient safety (A. Jones et al., 2023).

While much of the existing research focuses on the impact of investigations on the employees being investigated, less attention has been given to investigators. This paper addresses this gap in the literature by examining the potential harm experienced by those conducting disciplinary investigations in healthcare and discussing how this harm may contribute to reinforcing harmful practices. By investigating the perceptions and experiences of investigators, this study provides a novel perspective on the relationship between investigator well-being and their level of professional experience.

A cross-sectional survey of NHS Wales staff explored the effects of disciplinary investigations, specifically examining whether repeated exposure helps investigators develop a better understanding of harm avoidance or just reinforces existing practices. The research addresses the following hypotheses: (1) The application of disciplinary policies and procedures affects not only the individuals being investigated but also those conducting the investigation; (2) more experienced investigators feel better prepared to follow the formal steps of the investigation process; and (3) more experienced investigators feel better equipped to avoid personal harm or harm to those being investigated. These hypotheses aim to shed light on the impact of disciplinary investigations on investigators and their ability to manage the process effectively while mitigating harm.

2. Background

Individuals undergoing an employee investigation may experience significant distress, particularly when investigative processes are poorly conducted or lack meaningful support. Research indicates that such investigations can be highly stressful and, in some cases, even traumatic (Maben et al., 2021; Neal et al., 2023; Morrison et al., 2024). The concept of the ‘second victim’, first introduced by Wu (2000) in the context of patient safety, appears highly relevant in relation to the potential impact on those leading disciplinary processes.

Wu (2000) described how healthcare professionals can suffer emotional distress after being involved in a medical error or an adverse patient event. These individuals—often doctors, nurses, or other clinical staff—experience guilt, shame, anxiety, and even PTSD-like symptoms, making them ‘second victims’ alongside the patient (the ‘first victim’) who suffers direct harm. Scott et al. (2009) introduced the first comprehensive definition of second victims, outlining that these caregivers often experience a profound sense of failure, questioning their clinical skills, medical knowledge, and even their decision to pursue a career in healthcare. This definition was later refined to “any health care worker, directly or indirectly involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, unintentional healthcare error, or patient injury and who becomes victimized in the sense that they are also negatively impacted” (Vanhaecht et al., 2022). After an adverse event, the prevalence of secondary victims is estimated to vary from 10 per cent to 43 per cent (Seys et al., 2013).

With the discussion of second victims around for nearly a quarter of a century, there is now ample evidence that the unmitigated recovery of a second victim can contribute to absenteeism, turnover intentions, burnout, and loss of joy and meaning in work (New & Lambeth, 2024). Hence, strategies have been developed to support health professionals in responding to and addressing the consequences related to being a second victim (Quadrado et al., 2021; Cobos-Vargas et al., 2022). The preferred method of support among healthcare workers is a respected peer to provide emotional support (Finney & Jacob, 2023; New & Lambeth, 2024).

Healthcare organizations can support a second victim’s recovery by fostering a culture of safety and offering resources tailored to individual needs (New & Lambeth, 2024). In this context, it is essential to recognize that adverse events are an inherent part of healthcare, often resulting from workload pressures and the system’s complexity (Behrens et al., 2022). Acknowledging this reality requires accepting human fallibility and the inevitability of error (Rafter et al., 2015) while maintaining a genuine commitment to understanding what happened (Chen et al., 2023).

In healthcare, the ‘second victim’ approach has been extensively explored and considered across various professions, including medicine (Willis et al., 2019; Strametz et al., 2021; Potura et al., 2023), nursing (J. H. Jones & Treiber, 2012; Mok et al., 2020; Finney et al., 2021), and pharmacy (Werthman et al., 2021; Mahat et al., 2022; Bredenkamp et al., 2024). Beyond healthcare, the impact of being involved in investigative processes has also been explored in aviation, where investigators are described as “hidden victims” due to the significant stressors linked to aviation accidents (Cotter, 2004). While research in this area remains limited, there is growing recognition of the second victim phenomenon in other sectors, such as veterinary services and social care, where employees involved in adverse or traumatic events experience similar psychological effects (Conti et al., 2024).

Investigating officers and HR professionals often encounter sensitive and distressing material. They are also responsible for managing the complex emotional and organizational consequences that arise, which may include maintaining workplace morale, ensuring compliance with legal and regulatory standards, managing operational disruptions, and providing psychological support to employees affected by the investigation. One might argue that, although the approach to employee investigations differs from that of patient safety—focusing more on psychological harm than clinical harm—the concept of the ‘second victim’ helps foster an understanding that harm occurs at all levels when an adverse event happens, and this harm must be acknowledged and addressed. Furthermore, Vanhaecht et al.’s definition of a second victim, as outlined above, is highly relevant and applicable to individuals conducting investigations.

In the UK, while the application of disciplinary policy within organizations such as NHS Wales is considered an internal process, it can escalate into legal proceedings governed by employment law and tribunal frameworks (Rodgers, 2007). Tribunals often scrutinize the organization’s adherence to its own policies, the ACAS Code of Practice, and the employer’s duty of care. For many organizations, the potential threat of an employment tribunal has become a key driver of strict procedural compliance. However, this legal focus can overshadow the well-being and needs of the employee, and it is often passed on to managers who are responsible for delivering the process—creating stress and shaping behaviors that may ironically contribute to the very risks the process aims to avoid. As Knight and Latreille (2000) note, disciplinary and dismissal cases often lead to tribunal complaints when internal procedures are perceived as inconsistent or unfair.

This issue is particularly pronounced in the health sector. NHS employment arrangements are complicated by varied contractual frameworks: while most staff are employed under Agenda for Change, others—such as doctors and dentists—are subject to different professional bodies and governance procedures. In the case of nurses and other healthcare professionals, additional parallel processes governed by professional bodies often operate alongside internal disciplinary procedures. The legal position of managers serving as investigators in such complex systems, combined with psychological stressors, can heighten perceived risk. As highlighted by Peráček and Kaššaj (2023), non-compliance with prescribed procedures may also carry contractual implications, further reinforcing procedural defensiveness. In public administration more broadly, compliance and equality dominate HR processes, with education and training primarily emphasizing legal frameworks and traditional values (Siegel & Proeller, 2021). As a result, managerial capabilities, such as strategic planning, leadership, and psychological support, may receive less attention. Poorly designed investigative processes—exacerbated by legal ambiguities and stress—risk embedding harmful practices within organizational systems.

Investigator experience may help prevent harm. Repeated practice typically enhances performance (Syed, 2011). Additionally, research on decision-making suggests that experience influences how professionals assess risk, with more experienced individuals often identifying threats and consequences more readily than those with less exposure (Klein, 2017). Building on these insights, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The application of disciplinary policy and process affects not only the individuals being investigated but also those conducting the investigation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

More experienced investigators feel better prepared to follow the formal steps of the disciplinary investigation process.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

More experienced investigators feel better prepared to avoid personal harm or harm to those being taken through a disciplinary investigation.

3. Methods

3.1. Evaluation Design

This study employs a self-completed cross-sectional survey that collects quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously. The survey captures respondents’ views on the potential for negative impact, including harm to all individuals involved in an employee investigation (all 17 questions are listed in Appendix A).

For Hypothesis 1, we used a convergent mixed-methods design. Both qualitative data from three open-ended survey questions (Q15–Q17; Appendix A) and quantitative data from two closed-ended survey questions (Q4 and Q6; Appendix A) were collected simultaneously but analyzed separately. The results were then integrated to provide a comprehensive understanding of how disciplinary processes impact both the individuals under investigation and those conducting the investigation. The combination of closed and open-ended questions allows for the analysis and comparison of responses across the sample while also capturing detailed insights into respondents’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences (Vitale et al., 2008).

For Hypotheses 2 and 3, we employed a purely quantitative approach. These hypotheses were addressed using all 14 closed-ended survey questions (Q1–Q14; Appendix A).

This design provides a structured and comprehensive view of the research topic by using a convergent mixed-methods design for Hypothesis 1 and a quantitative approach for Hypotheses 2 and 3.

3.2. Study Setting

NHS Wales serves 3.1 million residents and employs more than 94,000 people (Welsh Government, 2023) across seven integrated health boards, three trusts, and three special health authorities (NHS Wales, 2024). Within NHS Wales, a national disciplinary policy and procedure (NHS Confederation, 2017) is in place to cover most of the workforce and address disciplinary issues that may arise. Within NHS Wales organizations, the line manager is responsible for commissioning and leading investigations, with advice and support provided by organizational HR teams.

In 2023, Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW), the strategic workforce body for NHS Wales, partnered with the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board (ABUHB)—this collaborative effort aimed to provide training for HR staff and individuals involved in leading employee investigations. The training event, Employee investigations: Looking after your people and the process (HEIW, 2025), was piloted within ABUHB to raise awareness of employee harm and significantly enhance staff’s ability to commission and conduct employee investigations. It was designed to promote a shift from a punitive approach to a more informal and supportive approach involving organizational learning, to address workplace issues more effectively (Cooper et al., 2024b).

3.3. Sample

Two Employee investigations: Looking after your people and the process training events were held on 21 and 23 March 2023 in north and south Wales, respectively, with participants from 10 of the 13 NHS Wales organizations (NHS Wales, 2024). These sessions aimed to raise awareness of avoidable employee harm and provide guidance on conducting employee investigations while supporting both the individuals involved and the overall process. Attendees were invited to complete the survey before the formal training day, sharing their experiences with commissioning, conducting, and supporting employee investigations. Of the 77 attendees, 71 voluntarily participated in the survey. Table 1 outlines their characteristics, including workgroup affiliation and level of experience.

Table 1.

Summary of attendee characteristics at events in March 2023.

3.4. Measures

The measures used for this research were developed to gain an understanding of employee harm during disciplinary investigations. The self-conducted survey included 17 questions (for the complete list, see Appendix A):

- The multiple-choice question Q1 asked for the participant’s experience with employee investigations, measured by the number of cases overseen/undertaken. We encoded the responses in the following way: “None at all” → Group 0 (Not experienced), “1–5” → Group 1 (Moderately experienced), “6–20” → Group 2 (Experienced), and “More than 20” → Group 3 (Highly experienced).

- Questions Q2 to Q14 were categorical questions measured on a 5-point Likert scale. The participants were asked for knowledge and experience with the investigation process, harm, and systematic support. We encoded the responses as follows: “Strongly Disagree” → “1”, “Disagree” → “2”, “Neutral” → “3”, “Agree” → “4”, and “Strongly Agree” → “5”.

- Questions Q15, Q16, and Q17 allowed respondents to insert free text to express emotions, practical experiences, and lessons learned. Furthermore, the respondents were asked to share ideas for process modifications.

Experts from ABUHB, along with researchers, line managers, and HR staff, evaluated the content validity of the 17 survey questions. Pre-tests with 204 participants at four NHS training events ensured their face validity. Insights from these assessments shaped the final survey, which is provided in Appendix A.

3.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data: We present Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for pairs of responses to the 14 closed-ended survey questions (Q1–Q14; Appendix A), collecting ordinal data. Additionally, we estimate simple linear regression models, assuming that the dependent variables are interval-scaled. All numerical analyses were performed using STATA, version 17.

Qualitative data: The responses to three open-ended survey questions (Q15–Q17; Appendix A), totaling 139 answers, were examined using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This qualitative approach allows for a detailed analysis of respondents’ reflections on their individual experiences with the investigation process. The survey respondents’ answers to the open-ended questions were collected in an Excel spreadsheet. After familiarizing themselves with the data, the researchers generated inductive initial codes, revised and refined the codes, and developed themes.

4. Results

4.1. Impact on the Investigator: Investigators Report Experiencing Harm When They Conduct Employee Investigations

Of the 71 survey respondents, only one disagreed with the statement that “the [disciplinary] process could sometimes harm colleagues under investigation” (Q4, Appendix A), indicating a strong consensus on its potential for harm. Additionally, 73% strongly agreed or agreed that “those conducting the investigation can also experience harm during the process” (Q6, Appendix A), while only 6% disagreed. Qualitative analysis of the three open-ended questions (Q15–Q17, Appendix A) reveals insights into the feelings and work stressors experienced by investigators. The themes identified through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors contributing to a negative impact on investigators (data generated by questions Q15–Q17; see Appendix A).

We found that investigators experience isolation, stress, and anxiety and are negatively affected by witnessing the suffering of others, including staff under investigation and colleagues (Table 2). This is supported by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient ρ, which shows a moderate relationship between investigator harm (Q6) and harm to those under investigation (Q4) (see Table 3; ρ = 0.43, p = 0.0002). Further themes emerging from the qualitative analysis reveal that investigators feel helpless and unable to conduct employee investigations as intended, partly due to an unclear process. Finally, investigators report being negatively affected by the often-challenging content of an employee investigation.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients ρ, rounded to two digits (bold numbers indicate significance at the 1% level; italic font indicates significance at the 5% level. The questions are listed in Appendix A).

The finding that the disciplinary process can negatively impact all individuals involved in an investigation is concerning, particularly because the well-being of some has been overlooked. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the underlying dynamics of investigations is necessary to develop measures that protect both colleagues under investigation and investigators. Table 3 presents Spearman’s correlation coefficients (−1 ≤ ρ ≤ 1) and their significance for pairs of questions, highlighting the existence of linear relationships between their rank orders. These relationships are further explained in this section.

4.2. Perceived Support and Impact Knowledge: More Experienced Investigators Feel Better Prepared for Their Roles and Perceive to Better Understand the Implications of Employee Investigations for Individuals

Table 3 shows that survey respondents who conduct more investigations (Q1) feel more supported and better equipped for their role (Q9) (ρ = 0.45; p = 0.0001). In addition to calculating Spearman’s rank coefficient, we performed linear regressions (results in Table 4) to examine the role of experience in disciplinary investigations. Column 1 of Table 4 indicates that inexperienced respondents have an average score of approximately 2.8 (where 2.0 corresponds to “disagree” and 3.0 to “neutral”). In contrast, experienced (6–19 investigations) and highly experienced (20+ investigations) respondents feel more supported and better equipped for their role, scoring nearly one unit higher (with 4.0 corresponding to “agree”). These differences are statistically significant at the 5% level (p < 0.005).

Table 4.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results.

Table 3 also shows a moderate relationship (ρ = 0.43; p = 0.0002) between the number of investigations conducted (Q1) and a respondent’s understanding of how investigations affect those involved (Q11). This suggests that experience enhances awareness of the impact of employee investigations, a finding supported by the regression results in column 4 of Table 4. These indicate that highly experienced respondents have an “understanding score” approximately 0.9 units higher than inexperienced individuals (placing their average scores between “4.0 = agree” and “5.0 = strongly agree”). However, the effects for moderately experienced and experienced respondents are not statistically significant.

4.3. Perceived Knowledge of the Investigation Process: Knowledge of the Formal Steps of an Employee Investigation Is Acquired Through Repetition; Nevertheless, the Investigation Process Needs to Be Clearer

Table 3 shows a moderate linear relationship (ρ = 0.40; p = 0.0006) between an investigator’s experience (Q1) and their perception that “the structures and processes of employee investigations are clear to follow” (Q2). Linear regression further confirms the impact of experience. Column 5 of Table 4 indicates that inexperienced respondents, with an average score of approximately 2.4, are pessimistic—or, at best, ambiguous—about the clarity of disciplinary processes. In contrast, experienced (+0.7 units) and highly experienced (+0.9 units) respondents perceive these processes more clearly, i.e., experienced investigators are more likely to perceive higher process clarity in investigations. However, even highly experienced investigators score no higher than 3.3 on average. With 3.0 corresponding to “neutral”, this implies that the clarity of the disciplinary process remains an area for improvement.

Given the perceived ambiguity in clarity, the question arises of how investigators navigate the investigation process in practice. Table 3 shows a strong linear relationship (ρ = 0.66; p < 0.0001) between experience (Q1) and good knowledge of the procedures involved during an investigation (Q10). This suggests that investigators primarily learn the formal steps of a disciplinary process through practice. Specifically, more experienced respondents score approximately 1.5 to 1.7 units higher than inexperienced individuals (as shown in column 6 of Table 4). These differences are statistically significant at the 0.1% level (p < 0.001).

4.4. Harm and Investigator Experience: Investigators Who Are Experienced and Well Versed in the Disciplinary Process Are Not Better Equipped to Protect Themselves and Others from Harm

Thus far, we have found that having more experience improves respondents’ understanding that employee investigations can negatively impact individuals (Section 4.2) as well as their knowledge of the process (Section 4.3). Still, out of the 71 respondents, only one disagrees with the statement that the process may sometimes harm colleagues under investigation (Q4). Column 7 of Table 4 shows that the average score of inexperienced survey respondents is approximately 4.2, a result that does not change significantly with additional experience. This finding aligns with a correlation coefficient as small as ρ = 0.07 (p = 0.5841; see Table 3). This means that the potential harm to those being investigated is not more often acknowledged as an issue with increased experience.

It is further interesting to note that the relationship between an investigator’s experience (Q1) and their potential for being harmed during an employee investigation (Q6) is also non-existent (see Column 8 of Table 4). This is evident from the data, where the correlation coefficient is 0.01, and the p-value is 0.9066 (see Table 3). Although 73% of the survey respondents agree that the disciplinary process can sometimes be harmful to the investigators, these responses are not related to the investigator’s experience. In other words, more experience does not imply that an investigator reports being harmed less often during the process.

In this context, we aim to highlight an important insight already addressed implicitly in Section 4.3: Having more process knowledge is not a magical bullet to harm avoidance. Table 3 indicates that there is no correlation between respondents’ perceived understanding of the formal steps of a disciplinary process (Q10) and the occurrence of investigator harm (Q6) (ρ = −0.06; p = 0.6349). Therefore, we conclude that being more educated about the investigation process does not imply less harm to the investigator. Similarly, having a good understanding of how investigations can impact the individuals involved in an investigation (Q11), awareness of how the organization can avoid harm to those being investigated as well as those conducting investigations (Q12), and perceiving that the ongoing well-being of the employee is a priority during the investigation process (Q13) are also not correlated with the occurrence of investigator harm (Q6) (see Table 3).

4.5. The Perceived Role of the Organization in Harm Avoidance: More Experienced Investigators Are Not More Aware of the Organization’s Well-Being Priorities Regarding the Disciplinary Process or How to Address the Potentially Harmful Aspects of Investigations

According to Table 3, there is a weakly significant relationship (ρ = 0.27; p = 0.0243) between investigator experience (Q1) and investigator awareness of how organizations can avoid harm (Q12), leading to a sobering conclusion. Although experience may enhance individuals’ understanding of the impact of investigations (as discussed in Section 4.2), awareness of how organizations can prevent harm shows minimal improvement with additional practice. This is supported by the regression analysis in column 9 of Table 4, where the average score for inexperienced survey respondents is approximately 3.2, with no significant differences found across experience levels. In simple terms, the code of conduct for investigators does not sufficiently address potential harm or harm reduction. This is further supported by the absence of a correlation between Q1, Q13, and Q14 (see Table 3 and Table 4), suggesting that more experienced investigators neither strengthen the perception that the organization prioritizes employee well-being (Q13) nor gain additional insights into the reintegration of investigated employees (Q14). Notably, the average score for prioritizing well-being is relatively high (3.7) (see column 10 of Table 4).

Table 3 also shows no significant correlation (ρ = 0.14, p = 0.2500) between investigator experience (Q1) and investigator belief that colleagues are well supported during investigations (Q3). Table 4 shows in column 12 that the average base score is approximately 2.5 (leaning toward “2.0 = disagree”), indicating that those who conduct more investigations do not perceive their colleagues under investigation as better supported. A similar, though weakly significant, result (ρ = 0.24; p = 0.0401; Table 3) is found for the relationship between investigator experience (Q1) and investigators being perceived as well-supported (Q5). Table 4, column 13, shows an average base score of roughly 2.8, between “disagree” and “neutral”. These findings indicate that harm reduction, ongoing well-being, and the reintegration of investigated employees are not embedded as core components of the disciplinary process.

5. Discussion

Our main findings can be summarized as follows. First, investigators report experiencing harm when they conduct employee investigations (H1). Second, more experienced investigators perceive themselves as being better prepared for their roles and having a better understanding of the formal steps of the disciplinary policy and process (H2). Third, investigators’ ability to avoid procedure-related harm to themselves or others remains unaffected by more experience (H3). Thus, we confirmed hypotheses H1 and H2, as presented in the background section, whereas H3 yielded a result opposite to what was expected.

Additionally, we find that more experienced investigators are not more aware of an their organization’s well-being priorities regarding disciplinary procedures or how to address potentially harmful aspects of employee investigations.

5.1. The Impact of Disciplinary Investigations on Investigators

In this paper, we have learned that investigators can be negatively affected (or even harmed) when conducting employee investigations. This happens for at least two possible reasons.

First, investigators often witness the distress experienced by employees and colleagues when disciplinary policies and processes are applied (“[…] I can see the impact it has on colleagues going through an investigation”). Investigators may also observe how problems with the process (like poor communication, failure to provide support, and delays to decisions being made) can aggravate the distress of the individual under investigation or possibly contribute to their psychological distress. Moreover, HR professionals and investigating officers—despite being trained to handle challenging investigations—may suffer from ongoing exposure to sensitive and disturbing material and repeated placement into emotionally straining situations. Under these circumstances, even experienced investigators may develop a sense of moral injury. This concept, initially used to describe the psychological toll that war takes on individuals who were forced to engage in, witness, or fail to prevent actions that conflict with their moral beliefs, ethics, and values (Jinkerson, 2016), may also apply to those involved in investigations that conflict with their moral compass.

The moral injury concept has been increasingly applied to healthcare workers under demanding and challenging circumstances, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chandrabhatla et al., 2022; Riedel et al., 2022). Its impact has been reported as giving rise to “feelings of guilt, shame, anger, sadness, anxiety and disgust; beliefs about being bad, damaged or unworthy; self-handicapping behaviors; loss of faith in people and avoidance of intimacy; and loss of religious faith, or loss of faith in humanity or a just world” (Open Arms, 2024).

Moral injury differs from PTSD in that it specifically involves conflicts related to moral and ethical dilemmas rather than just fear-based trauma. While applying the concept of moral injury to employee investigations marks a significant departure from its original purpose, it offers a perspective on how investigators might cope with the constant pressure they face. This pressure may be further intensified by investigators’ sense of obligation to carry out the investigative process thoroughly and to its fullest extent, ensuring that they (contribute to patient safety and) minimize legal vulnerability.

Second, when an organization’s response to mistakes and errors is to punish rather than learn, improve, and restore—and the disciplinary policy and process becomes the hard edge of this, it has the potential to give rise to the experience of personal distress in investigators (“I have been indirectly affected in my efforts to support individuals who have been negatively impacted and harmed by the ineffective and often unnecessary investigation process”). In addition, for investigating officers, the internal conflict over the work they have to do (delivering a disciplinary process) and the significant impact that it can have on those being taken through the process (often without a structured approach that provides an adequate duty of care) can lead to a moral tension that needs to be reconciled. The concept of cognitive dissonance is relevant here and states, “The existence of dissonance, being psychologically uncomfortable, will motivate the person to try to reduce the dissonance and achieve consonance. When dissonance is present, in addition to trying to reduce it, the person will actively avoid situations and information that would likely increase the dissonance” (Festinger, 1957, p. 3). As human beings are unable to indefinitely hold the moral tension and cognitive dissonance they are experiencing, we suggest that organizations provide the support needed for those undertaking investigations.

The consideration of moral injury and cognitive dissonance takes us back to the concept of the second victim, which is referred to in the background section of this paper. The considerations shared in this discussion highlight the need for a more comprehensive approach to harm reduction—one that acknowledges and addresses the impact of disciplinary processes not only on those being investigated but also on those conducting the investigations.

5.2. The Indirect Impact of the Application of the Process

Recognizing the impact on those leading investigations also raises an important concern: how their cumulative experiences and coping mechanisms may influence their ability to conduct future investigations effectively. Beyond individual cases, this can have broader implications, potentially shaping organizational culture in ways that extend beyond the application of disciplinary policies.

This suggests that to manage moral injury and cognitive dissonance, investigators may adopt coping mechanisms that shape both their approach to investigations and their perception of those under scrutiny. The most straightforward way to reduce distress is to avoid situations that cause it. However, for many healthcare managers and HR professionals, applying the disciplinary policy and process is a fundamental job requirement, making avoidance unrealistic.

When distancing themselves is not an option, investigators may rationalize harm as a necessary ingredient of an effective investigative procedure. Rationalization is a psychological defense mechanism in which individuals justify or explain their thoughts, behaviors, or emotions in a way that makes them seem more reasonable or acceptable, often to avoid confronting uncomfortable truths or cognitive dissonance. Instead of acknowledging distressing realities, people reframe situations to align with their beliefs, values, or expectations. For example, in the context of investigations, an investigator might rationalize a harsh disciplinary decision by telling themselves that strict enforcement of policies is necessary for organizational integrity, even if it causes harm to the individual being investigated. This helps them reconcile their actions with their sense of morality or professional duty, thereby reducing emotional discomfort. This, in turn, risks fostering a depersonalized or externalizing perspective, where the individuals under investigation are seen as undeserving of compassion. Although underexplored in healthcare, similar emotional regulation strategies have been documented in legal and law enforcement professions, including asylum lawyers (Graffin, 2019), barristers (Harris, 2002), and policing (Daus & Brown, 2012), highlighting the broader relevance of these coping behaviors.

Another factor that may influence investigator behavior is compassion fatigue. This concept, commonly discussed in professional care contexts, refers to a practitioner’s inability to empathize with or attend to the needs of others due to their own emotional exhaustion. Based on a concept analysis of compassion fatigue in nursing, it was found that “compassion fatigue occurred across disciplines. Nurses were particularly vulnerable due to repeated exposure to others’ suffering, high-stress environments, and continuous self-giving. The consequences of compassion fatigue negatively impacted the nurse, patient, organization, and healthcare system” (Peters, 2018, p. 466). Similarly, it is reasonable to suggest that investigators, particularly those working in emotionally charged environments, may experience a form of compassion fatigue. This could adversely affect their ability to perform future work with empathy and impartiality.

This is concerning for both the investigation process and those involved: investigators’ repeated exposure to the emotional aspects of the process may, over time, reduce their capacity for empathy and compassion, potentially undermining the quality of future investigations. Investigations that yield the best outcomes strike a balance between respecting the process and maintaining active empathy for the individual at the center of it (Neal et al., 2023). For those leading investigations, the ability to tolerate and effectively manage the psychosocial demands of their work (while recognizing the emotional aspects that affect them the most) can help minimize or mitigate negative impacts and harm. Accessing resources such as restorative supervision, debriefing opportunities, and peer support—similar to those available in fields like healthcare, psychology, and counseling—can provide essential support in maintaining investigators’ emotional well-being.

5.3. Reviewing Disciplinary Policies and Processes: Acknowledging Negative Impacts and Mitigation Strategies

While more experienced investigators—those who have conducted multiple investigations—feel better prepared to follow the formal steps of the disciplinary process (i.e., they have experienced learning by doing), they do not necessarily learn how to avoid or mitigate the potential negative impact of disciplinary investigations. This suggests that measures to reduce these negative effects must not only be explicitly defined, but also embedded into the policy itself, ensuring that they cannot be overlooked. Rather than relying on investigators to anticipate when and how to act without violating disciplinary guidelines, the policy must provide clear, structured guidance on mitigating harm at every stage of the investigation process. This does not imply that investigators must adhere rigidly to procedures without flexibility. Rather, it should emphasize the discretionary space available for decision-making and empower investigators to adopt a compassionate and context-sensitive approach when handling a case that requires intervention.

In this context, Lean thinking may have a role to play in organizational learning (Basten & Haamann, 2018) and process improvement (Womack & Jones, 2003; Harada, 2015). A fundamental principle of Lean is to put the customer first and streamline processes with customer needs in mind (Womack & Jones, 2003). Applied to employee investigations, this requires a shift in perspective: organizations must recognize the person under investigation as the ‘customer’ or, at the very least, a primary stakeholder. The person under investigation may have failed a patient (this is what the investigation seeks to find out), but harming this person during an investigation does not undo the harm to the patient. Therefore, disciplinary processes should be seen primarily as opportunities for learning, rather than as mechanisms for punishment or blame (Chaffer et al., 2019). To achieve this, organizations must explicitly state that investigations are intended to foster learning—promoting inquisitive rather than punitive cultures. Such an approach could be far more constructive and may also help mitigate harm to investigators by giving them greater control over a process that is currently insufficiently defined.

6. Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations apply. The study presented in this paper uses data from only one organization (NHS Wales and its constituent parts), and the sample size is small, which limits the generalizability of the results to other regions and sectors. Additionally, due to the voluntary nature of survey participation, we acknowledge the potential for selection bias—though clear emerging themes have surfaced that warrant further consideration and exploration. A further limitation is the reliance on self-reported data rather than objective measures. However, we aimed to understand how investigators perceive harm, not to assess objective signs of harm, such as burnout or increased sickness leave. Moreover, the survey questions underwent testing with four participant cohorts in advance to ensure face validity.

Despite these limitations, this study offers a novel focus on a crucial aspect of HR policy in healthcare that warrants deeper exploration. A key strength of the study is its exploration of the under-researched topic of investigator well-being in the context of disciplinary investigations. Additionally, the study’s design, which incorporated expert evaluations and pre-testing with multiple cohorts, enhances the robustness and reliability of the findings, providing a strong foundation for future research in this area.

7. Implications for Practice

This paper explores the impact of employee investigations on those responsible for conducting them within NHS Wales. It also acknowledges that the potential psychological toll on investigators may affect future investigations and how compassionately these cases are handled. This underexplored area of healthcare warrants further research and highlights several key actions for organizations to consider when implementing this HR practice (Cooper et al., 2025). Our analysis indicates that greater support is necessary for those tasked with conducting investigations. This includes ensuring sufficient capacity and resources to complete investigations in a timely manner, as well as providing access to professional networks for advice and support. Additionally, organizations should establish opportunities for regular review and reflection to mitigate the potentially harmful effects of the investigation process on investigators and, by extension, on others involved.

8. Conclusions and Ideas for Further Research

According to our results, training provided for those who lead investigations should focus on the process’s impact on all those involved (and the need for a compassionate approach), as well as on the importance of following policy and ensuring that the process is enacted correctly. Furthermore, disciplinary policies and processes should highlight the potential harm they can cause and include advice and resources to mitigate these impacts. Future policy should also be translated into a clear and inquisitive, rather than punitive, process (drawing on wider management theory) that ensures consistent delivery. It should also consider the individual nature of the cases and the organizational culture in which they are delivered. Finally, we find that using the disciplinary process and its related employee investigations as a ‘last resort’ and using more informal approaches to address workplace issues will have a positive impact on all employees involved in these processes, including the investigators.

Moving beyond healthcare, there is an opportunity to consider whether the issues being raised with the application of disciplinary policy and process affect other sectors and organizations, and to explore similar as well as sector-specific factors. This would add further insight into how investigators are impacted and perhaps provide solutions and approaches that have been adopted and from which healthcare could learn. There is also an opportunity for further research on the way in which perceptions of the legal requirements of a disciplinary process can shape and influence the behavior of those who lead them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.B., A.J.C. and W.H.; data curation, D.A.B., W.H. and S.E.J.; formal analysis, W.H., D.A.B. and S.E.J.; funding acquisition, A.J.C. and A.N.; project administration, A.J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.C., D.A.B., S.E.J., W.H., A.N. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, D.A.B., A.J.C., S.E.J. and W.H.; A.J.C. and D.A.B. contributed equally to this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The open access license for this article was funded by the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board (NHS Wales).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board’s Research & Development Department as a service evaluation (Approval code: SE/1456/22; Date: 26 October 2022 and 19 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The quantitative data presented in this study are available upon request to the corresponding authors in a fully anonymized form.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rhiannon Windsor and Eva Krczal for sharing their knowledge and providing valuable feedback on a later draft of this paper. ABUHB also wishes to acknowledge Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW) for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire/Survey

- Q1

- What is your experience, if any, of overseeing/undertaking employee investigations? Please indicate the number of cases overseen/undertaken. (None/1–5/6–20/More than 20).

Response options for Q2–Q14: Strongly Agree/Agree/Neutral/Disagree/Strongly Disagree.

- Q2

- The structures and processes of employee investigations are clear for all to follow.

- Q3

- Colleagues under investigation are currently well supported during and after the investigation.

- Q4

- Colleagues who are under investigation can sometimes be harmed by the process.

- Q5

- Colleagues who undertake/conduct the investigation are currently well supported.

- Q6

- Those undertaking the investigation can sometimes be harmed in the process.

- Q7

- I believe all of those involved in investigations have a good understanding of the process.

- Q8

- I have confidence in the employee investigation process.

- Q9

- I am fully supported and equipped in this area of my role.

- Q10

- I have good knowledge of the processes involved during an investigation.

- Q11

- I have a good understanding of how investigations can impact the individuals involved.

- Q12

- I am aware of how organizations can avoid harm to those being investigated and those leading investigations.

- Q13

- The ongoing well-being of the employee is a priority during the investigation process.

- Q14

- The organization supports the employee to re-integrate into the workplace following an investigation.

Q15–Q17 are open questions.

- Q15

- Have you sometimes been affected by an investigation process? If so, in what way?

- Q16

- What are some of the main issues you face when overseeing investigations?

- Q17

- What can be done to improve the investigation process for everyone involved?

Appendix B. Summary of Results

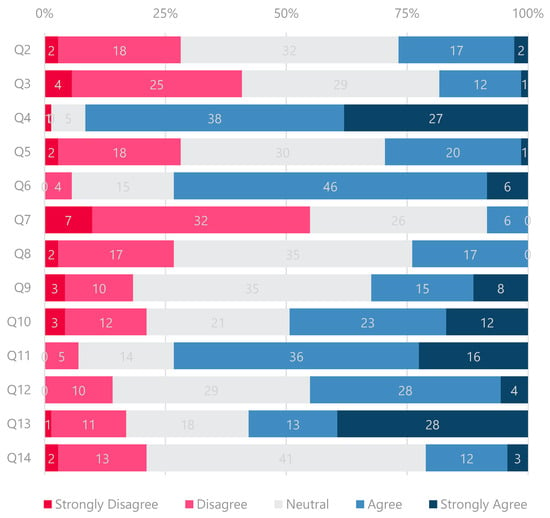

All variables of interest are measured on a five-point Likert scale with the outcome options strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. Summary statistics and response frequencies are depicted in Figure A1.

Figure A1.

Results of questions Q2 to Q14.

- Supplements

When asked whether the structures and processes of employee investigations are clear for all to follow (cf. Q2 in Appendix A), two respondents strongly agreed, 17 agreed, 32 remained neutral, 18 disagreed, and two strongly disagreed. When asked whether all those involved in investigations knew the process well (cf. Q7, cf. Appendix A), only six respondents agreed, 26 remained neutral, 32 disagreed, and seven strongly disagreed. In other words, only one in four respondents (27%) thought the process was clear to follow, and no more than 8% of the respondents believed that everyone involved in a disciplinary process knew it well (n = 71).

A correlation between Q2 and other statements implies that for some questions, we can look at the subgroups created by the response to Q2 to drill further into the clarity issue. To do this, we combined the two “agree” groups and the two “disagree” groups in an aggregated Clear and Unclear group.

In line with a weak to moderate correlation between Q2 and Q10 (ρ = 0.43; p = 0.0002), we found that only 16 of the 19 respondents from the Clear group further confirmed to know the processes involved in an investigation well (Q10, cf. Appendix A). (For the remainder, it is, however, questionable that respondents can provide a sound judgment of a process’s clarity without fully knowing it.) Furthermore, only 3 of the 19 who agreed that the investigation process is clear for all to follow also confirmed that all those involved in investigations understand the process well (Q7, cf. Appendix A). This result is puzzling, as Table 3 indicates that Q2 and Q7 are moderately correlated (ρ = 0.50; p = 0.0000), which could be interpreted such that a more straightforward and more precisely communicated process with unambiguous guidelines corresponds to a process that is better known by everyone. As we do not know whether this result was created by some of the process overseers (pointing the finger at IOs), we analyzed questions Q15 to Q17 to help further understand the clarity issue.

As outlined in Table A1, eight of 14 respondents from the Clear group explicitly stated in question Q17 (cf. Appendix A) that a clear process and simple guidelines (including formal paperwork) are required to improve the investigation process. Another three responses to Q17 (n = 14) and five to Q16 (n = 13) mentioned that investigation process training is needed, particularly for IOs. Therefore, a biased Clear group may have generated the odd result above.

Table A1.

Sub-themes of “The disciplinary process needs to be clearer” (responses of those who confirmed in Q2 that the investigation process is clear for all to follow). Note that IO is jargon for “Investigating Officer”.

Table A1.

Sub-themes of “The disciplinary process needs to be clearer” (responses of those who confirmed in Q2 that the investigation process is clear for all to follow). Note that IO is jargon for “Investigating Officer”.

| Sub-Themes | Anchor Quotes |

|---|---|

| Clearer process required | “Training and clarity of the process” could improve the investigation process. “Clear process, […], support, and training for all” could improve the investigation process. “Uncertainties” are a central issue overseeing investigations. |

| Simple guidelines required | “Clarification, simplified guidelines, and flow charts” could improve the investigation process for everyone involved. “[…] Clearer materials to support managers from jumping to conclusions” could improve the investigation process. “[…] More structured formal paperwork” could improve the investigation process. |

| Investigation process training required | “Lack of training in the investigation process” is a central issue overseeing investigations. “More in-depth training for IOs, more dedicated trained IOs […]” could improve the investigation process. “More training in the investigation process [on] how to investigate incidents with compassion and integrity” could improve the investigation process. |

| IOs who understand the process required | “Finding experienced IOs” is one of the main issues overseeing investigations. “IOs [are] not fully understanding the process.” |

The Neutral group’s response behavior differs from the Clear group due to an explicit non-perception of a clear investigation process. Moreover, 56% of the respondents from the Neutral group (n = 32) did not report good knowledge of the processes involved in an investigation (Q10, cf. Appendix A). Also, no more than 6% of the “Neutrals” (n = 32) confirmed that all those involved in investigations understood the process well (Q7, cf. Appendix A). These results are supported by the responses to the open questions (Q15–Q17, cf. Appendix A), provided in Table A2. Especially when asked what can be done to improve the investigation process for everyone involved (Q17; cf. Appendix A), 64% of the “Neutrals” suggested that a clear process, simple guidelines (including formal paperwork), and training for all involved in the process are required to improve the investigation process further (n = 25).

Table A2.

Sub-themes of “The disciplinary process needs to be clearer” (free-text entries of those who responded “Neutral” to Q2). Note that IO is an abbreviation for “Investigating Officer”.

Table A2.

Sub-themes of “The disciplinary process needs to be clearer” (free-text entries of those who responded “Neutral” to Q2). Note that IO is an abbreviation for “Investigating Officer”.

| Sub-Themes | Anchor Quotes |

|---|---|

| Clearer process required | “[I] felt unclear of the process.” |

| “Clear guidance for all involved in the process” could improve the investigation process. “Lack of confidence, [being] unsure of the process, and confusion around evidence gathering” are central issues overseeing investigations. “Clearer processes and easy ways of accessing support” could improve the investigation process. “Not [being] sure what information can be shared” is a central issue overseeing investigations. | |

| “Knowing how much information can be shared/disclosed” is an issue overseeing investigations. | |

| Simple guidelines required | “[…] Clear guidelines” could improve the investigation process for everyone involved. |

| “Toolkits for all parties, […] and support for all parties” could improve the investigation process. | |

| Investigation process training required | “Ensuring all involved in the process have received training in completing investigations –[from] chairing [to] hearing or [being a] panel member” could improve the investigation process. |

| “Better training and resources for investigators/HR/line management […]” could improve the investigation process. | |

| “Lack of understanding of IOs regarding roles and responsibilities” is one of the main issues overseeing investigations. |

Another vital implication results from a few correlations. Table 3 confirms the strong (linear) relationship between Q2 and Q3 (ρ = 0.59; p = 0.0000). That is, the perception of a more precise process for all involved corresponds to a higher perception that colleagues under investigation are currently well supported during and after the investigation (cf. Q3 in Appendix A). The moderate relationship between Q2 and Q5 (ρ = 0.42; p = 0.0003) implies that—to some extent—the perception that colleagues who undertake/conduct the investigation are currently well supported increases with process clarity. In other words, the more unclear the process is perceived, the less likely respondents believe that the people involved in an investigation are well supported. This conclusion also explains why an unclear process (Q2) corresponds to a low confidence level in the employee investigation process, as embodied in Q8 (ρ = 0.56; p = 0.0000).

References

- A Better NHS. (2024). Stories of NHS staff. Available online: https://www.abetternhs.com/case-histories-of-victimised-nhs-staff/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS). (2020). Discipline and grievances at work. The acas guide. Available online: https://www.acas.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-08/discipline-and-grievances-at-work-the-acas-guide.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS). (2024). Disciplinary and grievance procedures. Available online: https://www.acas.org.uk/disciplinary-and-grievance-procedures (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Archibong, U., Kline, R., Eshareturi, C., & McIntosh, B. (2019). Disproportionality in NHS disciplinary policy. British Journal of Healthcare Management, 25(4), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basten, D., & Haamann, T. (2018). Approaches for organizational learning: A literature review. SAGE Open, 8(3), 2158244018794224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, D. A., Rauner, M. S., & Sommersguter-Reichmann, M. (2022). Why resilience in health care systems is more than coping with disasters: Implications for health care policy. Schmalenbach Journal of Business Research, 74(4), 465–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, T. (2017). We need to change the culture around complaints procedures. BMJ, 359, j5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, T., De Cock, B., Wynants, L., Peters, M., Van Audenhove, C., Timmerman, D., Van Calster, B., & Jalmbrant, M. (2017). Doctors’ perception of support and the processes involved in complaints investigations and how these relate to welfare and defensive practice: A cross-sectional survey of the UK physicians. BMJ Open, 7(11), e017856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, T., Wynants, L., Peters, M., Van Audenhove, C., Timmerman, D., Van Calster, B., & Jalmbrant, M. (2015). The impact of complaints procedures on the welfare, health and clinical practise of 7926 doctors in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 5(1), e006687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredenkamp, K., Raschka, M. J., & Holmes, A. (2024). A review of medication errors and the second victim in pediatric pharmacy. Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 29(2), 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffer, D., Kline, R., & Woodward, S. (2019). Being fair. Supporting a just and learning culture for staff and patients following incidents in the NHS. NHS Resolution. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrabhatla, T., Asgedom, H., Gaudiano, Z. P., de Avila, L., Roach, K. L., Venkatesan, C., Weinstein, A. A., & Younossi, Z. M. (2022). Second victim experiences and moral injury as predictors of hospitalist burnout before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 17(10), e0275494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Skidmore, S., Ferrigno, B. N., & Sade, R. M. (2023). The second victim of unanticipated adverse events. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 166(3), 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos-Vargas, A., Pérez-Pérez, P., Núñez-Núñez, M., Casado-Fernández, E., & Bueno-Cavanillas, A. (2022). Second victim support at the core of severe adverse event investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A., Sánchez-García, A., Ceriotti, D., De Vito, M., Farsoni, M., Tamburini, B., Russotto, S., Strametz, R., Vanhaecht, K., Seys, D., Mira, J. J., & Panella, M. (2024). Second victims in industries beyond healthcare: A scoping review. Healthcare, 12(18), 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A., Neal, A., Windsor, R., Lewis, R., Bansal, D., & Yarker, J. (2025). An integrated framework for disciplinary processes and the application of employee investigations. British Journal of Healthcare Management. Online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A., Rogers, J., Phillips, C., Neal, A., Wu, N., & McIntosh, B. (2024a). The organizational harm, economic cost and workforce waste of unnecessary disciplinary investigations. British Journal of Healthcare Management, 30(4), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A., Teoh, K., Madine, R., Neal, A., Jones, A., Hussain, F., & Behrens, D. A. (2024b). The last resort: Reducing the overuse of employee relations investigations to prevent avoidable employee harm. Frontiers of Psychology, 15, 1350351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, M. (2004). The air accident investigator-often the hidden victim? Available online: https://esource.dbs.ie/items/1d3f0b6f-5de0-4827-a029-c4cc504872a8 (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Daus, C. S., & Brown, S. (2012). The emotion work of police. In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. E. J. Härtel, & W. J. Zerbe (Eds.), Experiencing and managing emotions in the workplace (pp. 305–328). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row and Peterson. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, R. E., & Jacob, A. K. (2023). Peer support and second victim programs for anesthesia professionals involved in stressful or traumatic clinical events. Advances in Anesthesia, 41(1), 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney, R. E., Torbenson, V. E., Riggan, K. A., Weaver, A. L., Long, M. E., Allyse, M. A., & Rivera-Chiauzzi, E. Y. (2021). Second victim experiences of nurses in obstetrics and gynaecology: A second victim experience and support tool survey. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(4), 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, T. K., Kaplan, G. S., Leape, L., Berwick, D. M., Edgman-Levitan, S., Edmondson, A., Meyer, G. S., Michaels, D., Morath, J. M., Vincent, C., & Wachter, R. (2018). Transforming concepts in patient safety: A progress report. BMJ Quality & Safety, 27(12), 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffin, N. (2019). The emotional impacts of working as an asylum lawyer. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 38(1), 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T. (2015). Management lessons from Taiichi Ohno: What every leader can learn from the man who invented the Toyota production system. McGraw Hill Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L. C. (2002). The emotional labour of barristers: An exploration of emotional labour by status professionals. Journal of Management Studies, 39(4), 553–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW). (2025). Employee investigations: Looking after your people and the process. Available online: https://nhswalesleadershipportal.heiw.wales/employee-investigations-training (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Hussain, F. A. (2022). Kafka lives: Consideration of psychological wellbeing on staff under investigation procedures in the NHS. South Asian Research Journal of Nursing and Healthcare, 4(3), 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinkerson, J. D. (2016). Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology, 22(2), 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A., Neal, A., Bailey, S., & Cooper, A. (2023). When work harms: How better understanding of avoidable employee harm can improve employee safety, patient safety and healthcare quality. BMJ Leader, 8(1), 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. H., & Treiber, L. A. (2012). When nurses become the “second” victim. Nursing Forum, 47(4), 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, G. (2017). Sources of power: How people make decisions. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, K. G., & Latreille, P. (2000). Discipline, dismissals and complaints to employment tribunals. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 38(4), 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maben, J., Hoinville, L., Querstret, D., Taylor, C., Zasada, M., & Abrams, R. (2021). Living life in limbo: Experiences of healthcare professionals during the HCPC fitness to practice investigation process in the UK. BMC Health Services Research, 21, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahat, S., Rafferty, A. M., Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K., & Härkänen, M. (2022). Negative emotions experienced by healthcare staff following medication administration errors: A descriptive study using text-mining and content analysis of incident data. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, W. Q., Chin, G. F., Yap, S. F., & Wang, W. (2020). A cross-sectional survey on nurses’ second victim experience and quality of support resources in Singapore. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(2), 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R., Yeter, E., Syed-Sabir, H., Butcher, I., Duncan, H., Webb, S., & Shaw, R. (2024). “It’s been years and it still hurts”: Paediatric Critical Care staff experiences of being involved in serious investigations at work: A qualitative study. Intensive Care Medicine–Paediatric and Neonatal, 2(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A., Cooper, A., Waites, B., Bell, N., Race, A., & Collinson, M. (2023). The impact of poorly applied human resources policies on individuals and organizations. British Journal of Healthcare Management, 29(5), 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, L., & Lambeth, T. (2024). Second-victim phenomenon. Nursing Clinics of North America, 59(1), 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Confederation. (2017). Disciplinary policy and procedure. Available online: https://www.nhsconfed.org/publications/disciplinary-policy-and-procedure (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- NHS Wales. (2024). About us. Available online: https://www.nhs.wales/about-us/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Open Arms. (2024). How do I recognise moral injury in myself and others? Available online: https://www.openarms.gov.au (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Peráček, T., & Kaššaj, P. (2023). Non-compliance with a prescribed disciplinary procedure: Do ordinary contractual principles apply? Industrial Law Journal, 52(2), 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E. (2018). Compassion fatigue in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 53(4), 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potura, E., Klemm, V., Roesner, H., Sitter, B., Huscsava, H., Trifunovic-Koenig, M., Voitl, P., & Strametz, R. (2023). Second victims among Austrian pediatricians (SeViD-A1 Study). Healthcare, 11(18), 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadrado, E. R. S., Tronchin, D. M. R., & Maia, F. D. O. M. (2021). Strategies to support health professionals in the condition of second victim: Scoping review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 55, e03669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafter, N., Hickey, A., Condell, S., Conroy, R., O’Connor, P., Vaughan, D., & Williams, D. (2015). Adverse events in healthcare: Learning from mistakes. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 108(4), 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, P. L., Kreh, A., Kulcar, V., Lieber, A., & Juen, B. (2022). A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, L. (2007). Employment law and professional discipline. In T. Daintith (Ed.), The regulatory enterprise (pp. 159–179). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., Cox, K. R., McCoig, M., Brandt, J., & Hall, L. W. (2009). The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. BMJ Quality & Safety, 18(5), 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Seys, D., Wu, A. W., Van Gerven, E., Vleugels, A., Euwema, M., Panella, M., Scott, S. D., Conway, J., Sermeus, W., & Vanhaecht, K. (2013). Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: A systematic review. Evaluation & Health Professions, 36(2), 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J., & Proeller, I. (2021). Human resource management in German public administration. In S. Kuhlmann, I. Proeller, D. Schimanke, & J. Ziekow (Eds.), Public administration in Germany (pp. 375–392). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Strametz, R., Koch, P., Vogelgesang, A., Burbridge, A., Rösner, H., Abloescher, M., Huf, W., Ettl, B., & Raspe, M. (2021). Prevalence of second victims, risk factors and support strategies among young German physicians in internal medicine (SeViD-I survey). Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 16(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M. (2011). Bounce: Mozart, Federer, Picasso, Beckham, and the science of success (Reprint ed.). Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaecht, K., Seys, D., Russotto, S., Strametz, R., Mira, J., Sigurgeirsdóttir, S., Wu, A. W., Põlluste, K., Popovici, D. G., Sfetcu, R., Kurt, S., Panella, M., & European Researchers’ Network Working on Second Victims (ERNST). (2022). An evidence and consensus-based definition of second victim: A strategic topic in healthcare quality, patient safety, person-centeredness and human resource management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, D. C., Armenakis, A. A., & Feild, H. S. (2008). Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods for organizational diagnosis. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(1), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L. M., & Greenfield, M. (2022). Employer support for health and social care registered professionals, their patients and service users involved in regulatory fitness to practise regulatory proceedings. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1), 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh Government. (2023). Staff directly employed by the NHS. Available online: https://www.gov.wales/staff-directly-employed-nhs-30-june-2023-html (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Werthman, J. A., Brown, A., Cole, I., Sells, J. R., Dharmasukrit, C., Rovinski-Wagner, C., & Tasseff, T. L. (2021). Second victim phenomenon and nursing support: An integrative review. Journal of Radiology Nursing, 40(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, D., Yarker, J., & Lewis, R. (2019). Lessons for leadership and culture when doctors become second victims: A systematic literature review. BMJ Leader, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J. P., & Jones, D. T. (2003). Lean thinking—Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. Simon & Schuster UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A. W. (2000). Medical error: The second victim: The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ, 320(7237), 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).